Abstract

Background: With standard treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC), prognosis is very poor. The aim of this study is to show early and late results in patients who underwent cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

Patients and methods: This was a retrospective single centre study. All patients with advanced and recurrent ovarian cancer treated with cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) or modified early postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy (EPIC) were included in the study.

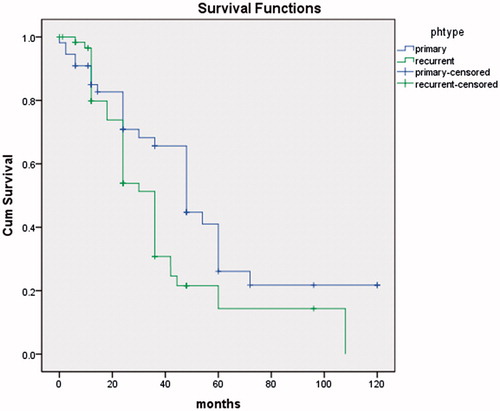

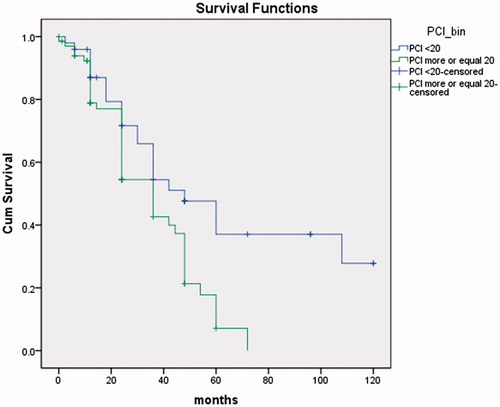

Results: In the period 1995–2014, 116 patients were treated, 55 with primary EOC and 61 with recurrent EOC. The mean age was 59 years (26–74). Statistically, median survival time was significantly longer in the group with primary advanced cancer of the ovary (41.3 months) compared to relapsed ovarian cancer (27.3 months). Survival for the primary EOC was 65 and 24% at 3 and 5 years, respectively. Survival for recurrent EOC was 33 and 16% at 3 and 5 years, respectively. Mortality was 1/116 (0.8%). Morbidity was 11/116 (9.5%). Peritoneal cancer index (PCI) was ≤20 in 59 (51%) patients and statistically, their average survival was significantly longer than in the group of 57 (49%) patients with PCI >20 (p = 0.014).

Conclusions: In advanced or recurrent EOC, a curative therapeutic approach was pursued that combined optimal cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy. PCI and timing of the intervention (primary or recurrent) were the strongest independent prognostic factors.

Introduction

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is the seventh most common cancer diagnosed in women with 240 000 new cases and 150 000 deaths worldwide in 2012. EOC is the fifth most common cancer among women and is the leading cause of death from gynecological cancers in the United States [Citation1].

The average age of patients at diagnosis was 63 years and at the time of diagnosis, 65–70% of patients had advanced disease (stage III or IV) [Citation2].

For patients under 25 years at the time of the first pregnancy and delivery, the use of oral contraceptives and/or breastfeeding has a reduced risk of ovarian cancer. Nulliparous women and those older than 35 years at pregnancy are at increased risk of developing EOC. Patients who have BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations have a 15% risk of ovarian cancer [Citation3]. Recent data suggests that hormone therapy and the presence of pelvic inflammatory disease may increase the risk of ovarian cancer [Citation2].

Standard treatment plans for patients with EOC is debulking surgery and the use of platinum-based chemotherapy. Although 70–80% of patients respond to first-line carboplatin and paclitaxel, the 5-year survival rate is less than 25% [Citation4].

Spiliotis et al. randomised 120 patients with stage III or IV OC that had recurred after debulking and systemic chemotherapy to CRS with HIPEC vs. CRS without HIPEC. Both groups of patients received systemic chemotherapy. These researchers observed a significant increase in mean survival in the HIPEC group (26.7 vs. 13.4 months, p < 0.006) with 3-year survival at 75 vs. 18% (p < 0.01) [Citation5]. Currently ongoing clinical trials (CHORINE, CHIPOR and OVHIPEC) may add more evidence of the importance of these procedures in the treatment of advanced ovarian cancer.

Numerous studies have shown that optimal cytoreductive surgery with minimal residual disease is significantly associated with increased survival time [Citation6,Citation7]. According to the literature data, the proportion of patients who underwent optimal cytoreduction varies from 15–85% [Citation8]. Griffiths et al. in 1975, showed that in patients with advanced ovarian cancer a significant prognostic factor was optimal cytoreduction and minimal residual disease. Hoskins and Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) showed that the sub-optimal cytoreduction, regardless of the diameter of the residual disease, does not contribute to improved survival [Citation9]. These researchers compared two groups of patients with advanced ovarian cancer. Patients with residual disease of less than 2 cm showed no significantly better survival compared to the group with residual disease greater than 2 cm. Chi et al. [Citation6] analysed a group of 282 patients who underwent surgery for advanced ovarian cancer in the period 1987–1994. Significant prognostic factors affecting the survival were the presence or absence of ascites, the size of residual disease and age of patients. It is not demonstrated that there is an impact on survival until the residual disease is reduced to less than 1 cm. Cytoreduction to less than 1 cm was achieved in 25% of patients with overall survival of 34 months for the whole 282 patient group [Citation10]. The most common cause of a large percentage of sub-optimal resection is that patients with dissemination and infiltration of the omentum (tissue below the stomach and above the column that is not resected), diaphragm, gallbladder, falciform ligament, liver and spleen were declared inoperable [Citation11]. It is necessary to achieve maximum cytoreduction – less than 1 cm of residual disease in the largest diameter [Citation11]. Extensive cytoreduction of the upper abdomen is recommended for patients who are able to tolerate the procedure [Citation12].

The primary aim of this study was to analyse morbidity and mortality with the use of intraperitoneal cisplatin and doxorubicin after maximal cytoreductive surgery in patients with peritoneal dissemination of EOC. The secondary objective was to determine overall survival and 3- and 5-year disease-free survival.

Materials and methods

This retrospective, non-randomised study was conducted at the Department of Colorectal and Pelvic Oncological Surgery, First Surgical Clinic of the Clinical Center of Serbia during the period 1995–2014 after being authorised by the Ethics Committee. Patients had advanced primary (FIGO IIIC-IV) or recurrent ovarian cancer.

The inclusion criteria were carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer confirmed by a pathologist, the absence of extra-abdominal metastasis and satisfactory renal and cardiorespiratory status. Primary cytoreductive surgery (surgery with the aim of complete resection of all macroscopic tumours in patients with first diagnosis of advanced ovarian cancer before any other treatment) and HIPEC or modified EPIC was performed in all patients with primary ovarian cancer without neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Surgery for platinum sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer (patients with recurrence more than six months after complete response) and surgery for platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer (patients with persistent disease after frontline treatment or recurrence within six months) and HIPEC or modified EPIC was performed in all patients with recurrent ovarian cancer.

The exclusion criteria were the presence of extra-abdominal metastasis, poor general condition, renal insufficiency and heart failure or the existence of a lesion in the CNS.

Diagnostic studies

All patients were subjected to abdominal physical examination, rectoscopy, complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, Ca-125, X-ray of the chest, MSCT (multi-slice computed tomography) or MRI of the abdomen and pelvis. The age of patients, PCI, stage of disease, type of surgical procedures performed, postoperative residual disease (CC score), histology and 3- and 5-year survival were also recorded.

The extent of the disease after laparotomy was determined by PCI. The abdomen and pelvis were divided into 13 regions and the size of the lesion was scored as 0–3. The maximum score was 39 [Citation13].

The completeness of cytoreduction was scored by Sugarbaker’s method: CC0, without residual disease; CC1, residual nodules smaller than 2.5 mm; CC2, 2.5 mm to 2.5 cm; CC3, residual nodules greater than 2.5 cm [Citation14].

Cytoreductive surgery

Surgical treatment was performed according to Sugarbaker’s method. After careful abdominal exploration, a median laparotomy (from pubis to xyphoid) was performed. Surgical resections were performed according to the rules of oncological surgery with a goal to resect all visible tumours in the peritoneal cavity. Electro-resections with monopolar diathermy were used for the resection of peritoneal deposits. The LigaSure impact (Covidien, Plymouth, MN) was used for omentectomy and dissection in the pelvis. Bowel anastomoses were made before the implementation of modified EPIC method by closed procedures or closed HIPEC.

Modified EPIC method with moderate hyperthermia

After surgical procedures, modified EPIC was performed by closed technique. Immediately before wound closure, doxorubicin, (0.1 mg/kg/day, max. 10 mg/day) dissolved in two litres of warm Ringer’s lactate (40 °C) was administered directly into the abdominal cavity. Four abdominal drains were closed during the intraperitoneal intraoperative chemotherapy and released after 2 h. During the next five days, cisplatin (15 mg/m2; max. 30 mg/day) dissolved in two litres of warm Ringer’s lactate (50 °C) was administered through four abdominal drains. Ringer’s lactate was heated up to 50 °C, allowing it to cool down to 40 °C prior to entering the abdominal cavity. The temperature of the solution was constantly monitored using a contact thermometer placed on the abdominal drains. The drains were placed sub-phrenically and in the pelvic cavity, bilaterally.

HIPEC by the closed method

Intraperitoneal chemotherapy with cisplatin (15 mg/m2; max. 30 mg) and doxorubicin (0.1 mg/kg, max. 10 mg) at 42 °C was delivered after all resections and anastomoses were completed using the Belmont® Hyperthermia Pump(Belmont instrument corporation, Billerica, MA). The pump for HIPEC included four closed suction drains placed intra-abdominally, specifically one beneath each hemidiaphragm and two in the pelvis.

Morbidity was reported according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria: grade I postoperative complication - no intervention was required for resolution, grade II - medical treatments were required for resolution, grade III- required an invasive intervention, such as a radiological intervention for resolution and grade IV- postoperative complications required urgent definitive intervention, such as returning to the operating room or ICU for resolution and grade V - death related to an adverse event [Citation15].

At discharge, patients were referred to an oncologist for further treatment with systemic chemotherapy (3–6 cycles) and postoperative follow-up.

Selection criteria

Modified EPIC was applied prior to obtaining the HIPEC pump (until 2008); thus, surgery time was the only criterion for the selection of the procedure type.

Statistics and data processing

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) with the Kaplan-Meier method and survival curves (univariate analyses) were compared using a log-rank test. Hypothesis comparisons were performed using the Chi-square test for contingency tables, the Mann-Whitney U test and T-Test for two independent means. A two-tailed test resulting in p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

In the period from 1995–2014, 116 patients were treated; 55 had primary and 61 had recurrent cancer. Fifty-six patients with ovarian cancer underwent CRS + modified EPIC and 60 patients underwent CRS + HIPEC. In the recurrent ovarian cancer group, eight were platinum-resistant and 53 were platinum-sensitive patients. Details of patient characteristics, histological subtype, PCI, CC-score and surgical variables are given in .

Table 1. Patients characteristics according to origin (primary or recurrent).

The mean age was 59 years (26–74). The median duration of surgery was 4 h and 42 min (3 h 30 min – 6 h 20 min). Median blood loss was 526 millilitres (280–1450 ml). Statistically, median survival time was significantly longer in the group with a primary advanced cancer of the ovary (41.3 months) compared to relapsed ovarian cancer (27.3 months).

Survival for the primary EOC was 65 and 24% at 3- and 5-years, respectively. Survival for recurrent EOC was 33 and 16% at 3-and 5-years, respectively. Mortality was 1/116 (0.8%). Morbidity was 11/116 (9.5%).

After laparotomy, all patients received cytoreductive surgery involving one or more of the following procedures, as shown in .

Table 2. Surgical procedures performed in all patients with ovarian cancer.

PCI score

Median peritoneal cancer index (PCI) was 19.9 (5–32), SD 6.3.

CC score

In our series of patients, we achieved a CC0 in 102 patients (88%), CC1 in 10 (9%) and CC2 in 4 (3%). In 112 patients (97%), optimal cytoreduction was achieved. Statistically, median survival time was significantly longer in the CC0 and CC1 group compared to CC2 and CC3 group (p = 0.002).

Morbidity/mortality

Eleven patients (9.5%) developed postoperative complications – Grade II: two patients had thrombocytopenia and anaemia which required cessation of chemotherapy and administration of blood, frozen plasma and albumin. One patient had a transient metabolic acidosis, one had a wound infection and three patients had nausea and vomiting and three cases of postoperative prolonged bowel obstruction was reported which was resolved by conservative treatment; Grade IV: one anastomotic leak requiring reoperation and Grade V: one patient (0.8%) died due to cerebrovascular insult.

Survival

There was no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05) between modified EPIC and HIPEC groups.

The median survival time was significantly longer in the group with a primary advanced cancer of the ovary (40.3 months) than in recurrent ovarian cancer (27.6 months) (p = 0.014) (). Survival for the primary EOC was 65 and 24% at 3- and 5-years, respectively. Three-year survival for recurrent EOC was 33% and 16% at 5-years. PCI was less than or equal to 20 for 59 patients (51%) and statistically their average survival was significantly longer than in the group of 57 (49%) of patients with PCI more than 20 (p < 0.01) ().

Discussion

Survival statistics

This retrospective, single centre study that included 116 patients is a series of selected patients with peritoneal metastases from ovarian cancer treated with CRS and HIPEC. This combined treatment yields a median survival of 40, three months for advanced EOC and 27, six months for recurrent EOC.

Chua et al. reported (review) median overall survival ranged from 22 to 64 months, overall 3-year survival rate ranged from 35 to 63% and 5-year survival rate ranged from 12 to 66% [Citation16].

If we compare our results with the Bakrin et al. French multicenter retrospective cohort study of 566 patients [Citation17], we can see that for advanced EOC, median overall survival was 35.4 months (our result 40.3). The survival rates at 3- and 5-years were 47 (65%) and 17% (24%), respectively. Better overall survival may be explained by smaller percent of patients in which CC2–3 resection had been performed.

For recurrent EOC, the median overall survival was 45.7 months (27.6). The overall survival rates at 3- and 5-years were 59 (33%) and 37% (16), respectively. Average PCI in our study population was 20.3, while in Bakrin et al. group it was eight, with similar percent of patients with CC2–3 resection.

The third GOG study, GOG 172, published by Armstrong et al. [Citation18] showed the median duration of progression-free survival in the intravenous-therapy (intravenous paclitaxel plus cisplatin) and intraperitoneal-therapy (intravenous paclitaxel plus intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel) groups was 18.3 and 23.8 months, respectively. The median duration of overall survival in the intravenous therapy and intraperitoneal therapy groups was 49.7 and 65.6 months, respectively. Above the fact that additional intraperitoneal therapy improves survival rates, we can acknowledge that in patients in which suboptimal cytoreduction had been performed survival rates were significantly lower (39.1 vs. 78.2 months). This fact only strengthens the need for complete cytoreduction.

Completeness of cytoreduction

In the past, CRS with residual malignant deposits greater than 1 cm and less than 2 cm was considered optimal and in subsequent years, there was a change of attitude, with researchers determining that it is necessary to undergo a complete surgical resection of all visible tumour deposits. The Gynecologic Cancer Interstudy Group (GCIG) has changed the official nomenclature and requirements for peritonectomy and multi-visceral resection, depending on the degree of peritoneal metastasis. The DESKTOP 1 study conducted by the AGO has identified the following parameters for the possibility of complete resection in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer: good general health, absence of residual disease after surgery EOC, early initial FIGO stage and absence of ascites according to radiological examinations. If all of these factors were positive, completeness of resection was achieved in 79% of patients. If all factors were positive, then completeness is achieved in 43% of patients [Citation19]. Major study limitation is absence of clear parameters for avoiding the radical surgery. Also, complete cytoreduction was performed in only 24% of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. This can be explained by insufficient training of gynaecologists in performing cytoreduction of upper abdomen. In our study, 97% of patients had optimal cytoreduction, whaich corresponds to the results of Bakrin et al. [Citation17] (92,1%, 474 pt.) and Coccolini et al. [Citation20], (100%, 54 pt.).

Morbidity and mortality rates vary from centre to centre. Average morbidity (within 30 days) ranges from 19.2 to 34%. The complication rate was not significantly different in the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer in relation to primary debulking surgery mortality rate is 0.7–2.8% in the primary and in recurrent EOC 1.2–5.5% [Citation21]. Our morbidity rate was 9% and five patients had minor complications of Grade I and II. We did not have grade III complications, while we had two grade IV complications. Mortality was 0.8%, which is consistent with the results of published studies. Chua et al. [Citation16] reviewed 895 patients from 19 different studies. The mortality rate ranged from 0 to 10%. Grade I morbidity ranged from 6–70%, grade II morbidity 3–50%, grade III morbidity 0–40% and grade IV morbidity ranged from 0–15%. Common postoperative complications were ileus, anastomotic leakage, bleeding, wound infection, toxicity, pleural effusion, infections, fistula, transient hepatitis and thrombocytopenia. Mortality and morbidity rates depended on the patient’s age, general condition of the patient, the number and type of resection procedures and duration of HIPEC. A very important factor is the surgical learning curve and experience of the entire team. If we examine the with surgical procedures in ovarian cancer we can conclude that a gynaecologist oncologist alone or with the help of experienced gastrointestinal surgeons must be trained to perform cytoreduction of the upper parts of the abdomen in the addition to the standard pelvic surgery. This statement agrees with the results and the conclusions drawn by Chi et al. [Citation11].

Tan et al. [Citation22] showed that there were no significant OS and DFS differences between the EPIC and no EPIC groups, which may result in increased morbidity and longer hospitalisation. In our patients, there were no significant OS differences between modified EPIC and HIPEC groups. McConnell et al. [Citation23] showed comparable results: the use of EPIC, in combination with CRS and HIPEC, is associated with an increased rate of complications without significant OS and DFS differences.

New investigative techniques such as fluid and CO2 recirculation using the closed abdomen technique (PRS-1.0 Combat) show that closed abdomen intraperitoneal chemo-hyperthermia by a fluid and CO2 recirculation system (PRS-1.0 Combat®) can be a safe and feasible model for the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis of ovarian cancer origin [Citation24].

Conclusions

Patients with EOC and peritoneal dissemination have poor survival. Patients with primary cancer and PCI less than 20 can expect better survival; therefore, it is critical to perform optimal treatment, which includes CC0/CC1 CRS and it is necessary to achieve maximum cytoreduction.

A multidisciplinary approach to patients with advanced EOC allows optimisation of the treatment strategy based on patients characteristics (age, performance/nutritional status, co-morbidities, functional status) and tumour diffusion (evaluated pre- and intra-operatively).

Gynecologists alone or with the help of experienced gastrointestinal surgeons should be able to do the following: cytoreduction in the upper abdomen, peritonectomy, total omentectomy and resection of the bowel when necessary.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Jelovac D, Armstrong DK. (2011). Recent progress in the diagnosis and treatment of ovarian cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 61:183–203.

- Fleming GF, Seidman J, Lengyel E, Epithelial ovarian cancer. In: Barakat RR, Markman M, Randall ME, eds. Principles and Practice of Gynecologic Oncology, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013:757–847.

- Lancaster JM, Powell CB, Kauff ND, et al. (2007). Society of Gynecologic Oncologists Education Committee statement on risk assessment for inherited gynecologic cancer predispositions. Gynecol Oncol 107:159–62.

- Ozols RF. (2005). Treatment goals in ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 15:3–11.

- Spiliotis J, Halkia E, Lianos E, et al. (2015). Cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC in recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: a prospective randomized phase III study. Ann Surg Oncol 22:1570–5.

- Chi DS, Liao JB, Leon LF, et al. (2001). Identification of prognostic factors in advanced ovarian epithelial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 82:532–7.

- Chi DS, Eisenhauer EL, Lang J, et al. (2006). What is the optimal goal of primary cytoreductive surgery for bulky stage IIIC epithelial ovarian carcinoma? Gynecol Oncol 103:559–64.

- Bristow RE, Tomacruz RS, Armstrong DK, et al. (2002). Survival effect of maximal cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian carcinoma during the platinum era: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 20:1248–59.

- Hoskins WJ. (1994). Epithelial ovarian carcinoma: principles of primary surgery. Gynecol Oncol 55:S91–6.

- Redman JR, Petroni GR, Saigo PE, et al. (1986). Prognostic factors in advanced ovarian carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 4:515–23.

- Chi DS, Eisenhauer EL, Zivanovic O, et al. (2009). Improved progression-free and overall survival in advanced ovarian cancer as a result of a change in surgical paradigm. Gynecol Oncol 114:26–31.

- Whitney CW, Spirtos N. (2009). Gynecologic Oncology Group Surgical Procedures Manual. Philadelphia: Gynecologic Oncology Group.

- Sugarbaker PH. (1996) Peritoneal carcinomatosis. Principles of management. Boston: Kluver Academic.

- Sugarbaker PH, Chang D. (1999). Results of treatment of 385 patients with peritoneal surface spread of appendiceal malignancy. Ann Surg Oncol 6:727–31.

- National Cancer Institute. Common terminology criteria for adverse events v.4.0 (CTCAE). Available from: http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm. [last accessed 20 Jun 2012].

- Chua TC, Robertson G, Liauw W, et al. (2009). Intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy after cytoreductive surgery in ovarian cancer peritoneal carcinomatosis: systematic review of current results. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 135:1637–45.

- Bakrin N, Bereder JM, Decullier E, et al. (2013). Peritoneal carcinomatosis treated with cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for advanced ovarian carcinoma: a French multicentre retrospective cohort study of 566 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol 39:1435–43.

- Armstrong D, Bundy B, Wenzel L, et al. (2006). Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 354:34–43.

- Harter P, Hahmann M, Lueck HJ, et al. (2009). Surgery for recurrent ovarian cancer: role of peritoneal carcinomatosis: exploratory analysis of the DESKTOP I Trial about risk factors, surgical implications, and prognostic value of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Ann Surg Oncol 16:1324–30.

- Coccolini F, Campanati L, Catena F, et al. (2015). Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy with cisplatin and paclitaxel in advanced ovarian cancer: a multicenter prospective observational study. J Gynecol Oncol 1:54–61.

- Halkia E, Spiliotis J, Sugarbaker P. (2012). Diagnosis and management of peritoneal metastases from ovarian cancer. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2012:541842.

- Tan GH, Ong WS, Chia CS, et al. (2016). Does early post-operative intraperitoneal chemotherapy (EPIC) for patients treated with cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) make a difference? Int J Hyperthermia 32:281–8.

- McConnell YJ, Mack LA, Francis WP, et al. (2013). HIPEC + EPIC versus HIPEC-alone: differences in major complications following cytoreduction surgery for peritoneal malignancy. J Surg Oncol 107:591–6.

- Sánchez-García S, Villarejo-Campos P, Padilla-Valverde D, et al. (2016). Intraperitoneal chemotherapy hyperthermia (HIPEC) for peritoneal carcinomatosis of ovarian cancer origin by fluid and CO2 recirculation using the closed abdomen technique (PRS-1.0 Combat): a clinical pilot study. Int J Hyperthermia 32:488–95.