Abstract

Objective: To explore the role of whole gland cryoablation plus ADT in prostate cancer (PCa) with bone metastases compared with ADT treatment alone in metastatic PCa.

Methods: A total of 30 patients with biopsy-proven PCa with bone metastases underwent cryoablation and ADT treatment. The control group consisted of 30 men who were initially treated with ADT only and who were followed until progression, development of castration resistant PCa or death. Patients were pair matched for age, PSA level, clinical stage, preoperative biopsy Gleason score and bone metastases. Time to clinical progression, time to CRPC, cancer-specific survival and overall survival were analysed using descriptive statistical analysis.

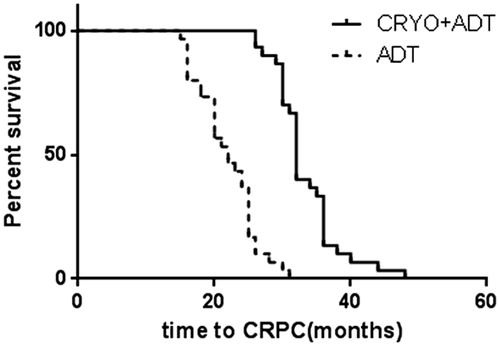

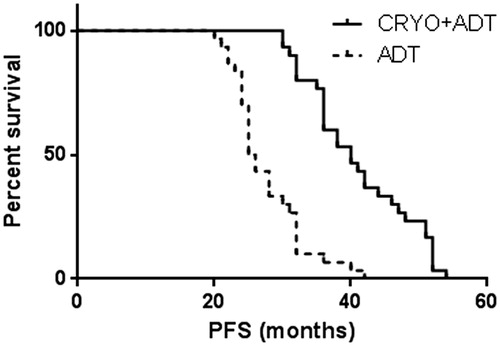

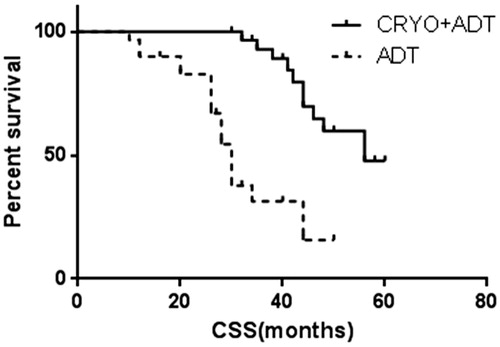

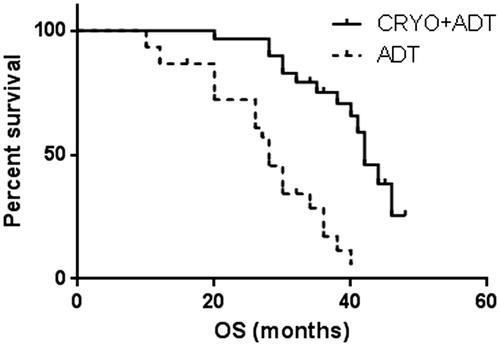

Results: Age at diagnosis, baseline PSA, biopsy Gleason score and ECOG status were comparable between the two groups. Prostate cryoablation was well tolerated and no serious complications occurred. At the last follow-up, patients in the cryoablation and ADT treatment group had a lower median PSA nadir (0.4 ng/ml vs. 0.8 ng/ml, p < 0.01) and longer time to CRPC (33 ± 0.9 mo vs. 22 ± 0.8 mo, p < 0.01). Further analyses detected the statistically significant benefits of cryoablation treatment not only in PFS (41 ± 1.4 mo vs. 22 ± 0.8 mo, p < 0.01), but also in CSS (52 ± 1.9 mo vs. 32 ± 2.4 mo, p ± 0.01) and OS (41 ± 1.5 mo vs. 28 ± 1.7 mo, p < 0.01). Moreover, there were fewer palliative procedures for local progression in the cryoablation group than the controls.

Conclusions: Cryoablation plus ADT might be a treatment option in the multimodality management of metastatic prostate cancer. Further investigations are warranted.

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most common cancer in men worldwide. In China, although the incidence and mortality rates of PCa remain low (age-standardised incidence and mortality rates of, 5.3 per 100 000 and 2.5 per 100 000, respectively, in 2012), PCa is the most common and the most lethal male urogenital system cancer, as it is worldwide. Historically, approximately 25% of men present with either metastatic or lymph node–positive disease [Citation1].

ADT remains the initial management for patients with metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis. However, new clinical data are challenging this concept, since several studies have suggested an oncologic benefit to local treatment even in a metastatic setting [Citation2–4]. In 2014, data from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results database (SEER) were published showing an apparent survival benefit for radical prostatectomy (RP) or brachytherapy versus no local treatment in patients with metastatic prostate cancer (mPCa) [Citation2]. At the same time, the data from the Munich Cancer Registry also showed a significant survival benefit for patients with mPCa undergoing RP compared with no RP (the 5-year OS rate: 55% vs. 21%) [Citation3]. A study by Gill confirmed that local therapy with RP or intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) was associated with survival benefit [Citation4]. Despite the lack of data on comorbidity status and the extent of metastatic lesions and postoperative management, local treatment seemed to provide a survival benefit to mPCa patients.

Cryoablation is also a definitive local treatment for prostate cancer. In 2008, the American Urologic Association released its best practices statement on cryoablation for the treatment of localised prostate cancer [Citation5]. Because of its minimally invasive nature, cryoablation gained popularity as a salvage or primary treatment, even in locally advanced diseases [Citation6]. In randomised trials involving T2–T3 stage patients, whole-gland cryoablation showed survival results comparable with radiation therapy in 4 [Citation7] or even 8 years [Citation8], and a lower follow-up biopsy positive rate (7.7% vs. 28.9%) at 36 months [Citation9]. However, no special study has analysed the oncologic results of cryoablation for mPCa.

In this report, we retrospectively investigated the oncological outcomes after cryoablation in addition to ADT and compared these results with those receiving ADT alone in patients with asymptomatic bone metastasis, including overall survival (OS), cancer-specific survival (CSS), time to CRPC and progression-free survival (PFS).

Materials and methods

From January 2011 to December 2013, 30 patients with biopsy-proven PCa and bone metastatic disease underwent cryoablation and ADT treatment. All patients underwent a routine transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) guided 12- to 18-core biopsy of the prostate and routine pre-treatment imaging staging procedures which included a pelvic MRI scan, chest CT scan and skeletal scintigraphy. Patients were recommended to receive cryoablation when there were no gross retroperitoneal lymph node metastases and no visceral metastases. The patients’ demographics are summarised in . This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of our university, and the informed written consent was obtained from the patients or their family members.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

The cryoablation procedure was performed using an argon/helium gas-based system (Endocare, HeathTonics Inc., Irvine, CA). Under TRUS guidance, the probes were placed through the skin of the perineum, ≈10 mm apart, within 5 mm of the capsule. Thermocouple sensors were inserted at five periprostatic locations: right/left neurovascular bundles (NVB), prostate apex, rhabdosphincter and Denonvilliers’ fascia between the prostate and rectum. The freezing process was monitored in real time by transrectal ultrasound to avoid creating lesions on adjacent tissues. A double freeze–thaw cycle and a urethral warming device were used. The procedure was performed within one month after initial ADT with LHRH analogue treatment in the combination treatment group.

This patient group was matched with another group including 30 patients from a pre-existing database of 252 patients who received ADT with LHRH analogue only. A match-paired analysis was performed with respect to age, prostate volume, initial PSA, clinical stage, Gleason score and bone metastases were pair matched for age, PSA level, clinical stage, biopsy Gleason score and bone metastases. All patients had not received prior radiotherapy or chemotherapy.

Follow-up examinations included measurement of the serum concentrations of PSA and testosterone. No routine imaging studies were performed in patients with PSA serum levels <4 ng/ml, with skeletal scintigraphy at least once a year. The patients were followed until progression, development of castration-resistant PCa or death. The parameters were compared between both groups: time to PSA relapse, time to clinical progression, time to castration resistance, CSS and OS.

Definition of progression

Biochemical progression was defined by two consecutive increases above the first postoperative PSA, 1 week apart, resulting in two 50% increases over the nadir. No routine imaging studies were performed unless the PSA serum levels increased to above 4 ng/ml or if they were associated with clinical symptoms. Clinical progression was defined by the onset of new symptoms due to local progression, lymphonodular or systemic metastases. PFS was defined as the time from initiation of ADT to the first evidence of biochemical or clinical progression. Time to CRPC was measured as the time from the initiation of ADT until the documentation of confirmed biochemical progression in the presence of castrate serum testosterone levels defined by ≤50 ng/dl. After patients developed CRPC, they were observed or received one of the several treatment regimens such as estramustine, mitoxantrone and/or docetaxel. CSS was defined as the time interval from diagnosis to death due to prostate cancer. OS was defined as the time interval from the initial diagnosis of PCa to death due to any non-cancer related cause.

SPSS15.0 (Chicago, IL) was employed in pair-matched and all other statistical analyses. The Kaplan–Meier method was used in survival analysis and the Log rank test was used for statistical significance testing. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Age at diagnosis, baseline PSA, biopsy Gleason score and bone metastases were comparable between the two groups ().

Prostate cryoablation was well tolerated without the need for blood transfusions, and no postoperative deaths occurred. Of the 30 patients, two (4.0%) patients developed mild incontinence requiring 1–2 pads/day, and no patient had urinary retention. No urethral strictures, recto-urethral fistulae or chronic pelvic pain were reported. Two patients were shown to have tumour recurrence by biopsy at 22 and 30 months after cryoablation (six patients underwent re-biopsy after biochemical recurrence).

After CRPC, subsequent therapies in the cryoablation treatment group included twelve (40%) patients with estramustine, nine (30%) patients who underwent chemotherapy with docetaxel, and nine (30%) patients with supportive treatment respectively. No surgical or percutaneous intervention treatment was needed due to local progression. In the ADT alone treatment group, sixteen (53.3%) patients were treated with estramustine, seven (23.3%) patients underwent chemotherapy with docetaxel, and seven (23.3%) patients received supportive treatment. Eight (26.7%) patients underwent palliative TURP for urethral obstruction with and without bladder clot retention, and two (6.7%) patients required a percutaneous nephrostomy for the management of a symptomatic unilateral hydronephrosis.

Data on progression and survival are listed in , and Kaplan–Meier curves are shown in . At the last follow-up, patients in the cryoablation and ADT treatment group had a lower median PSA nadir (0.4 ng/ml vs. 0.8 ng/ml, p < 0.01) and longer time to CRPC (33 ± 0.9 mo vs. 22 ± 0.8 mo, p < 0.01). Multivariate analyses detected statistically significant benefits of cryoablation treatment not only in PFS (41 ± 1.4 mo vs. 22 ± 0.8 mo, p < 0.01), but also in CSS (52 ± 1.9 mo vs. 32 ± 2.4 mo, p < 0.01) and OS (41 ± 1.5 mo vs. 28 ± 1.7 mo, p < 0.01).

Figure 1. Pair-matched analysis of time to CRPC in patients who underwent cryoablation + ADT therapy (33 ± 0.9 mo; 95%CI 32–35) versus ADT alone (22 ± 0.8 mo; 95%CI 20–24), Log-rank test showed p < 0.01.

Figure 2. Pair-matched analysis of PFS in patients who underwent cryoablation + ADT therapy (41 ± 1.4 mo; 95%CI 38–44) versus ADT alone (28 ± 1.0; 95%CI 26–30), Log-rank test showed p < 0.01.

Figure 3. Pair-matched analysis of CSS in patients who underwent cryoablation + ADT therapy (52 ± 1.9 mo; 95%CI 48–56) versus ADT alone (32 ± 2.4 mo; 95%CI 27–37), Log-rank test showed p < 0.01.

Figure 4. Pair-matched analysis of OS in patients who underwent cryoablation + ADT therapy (41 ± 1.5 mo; 95%CI 38–44) versus ADT alone (28 ± 1.7 mo; 95%CI 24–31), Log-rank test showed p < 0.01.

Table 2. Oncological outcome.

Discussion

Although retrospective in design, this study demonstrated the potential benefit of cryoablation in clinical PFS, time to CRPC and even CSS and OS. Our results might provide some evidence about the application of cryoablation in selected prostate cancer patients with bone metastases. Until now, there has been no consensus-based role of definitive therapy of the primary tumour or whether loco-regional tumour control provided a survival advantage. Without evidence from randomised controlled clinical trials, our approach could serve as an individual treatment option.

Recently, increasing evidence has suggested that RP plus ADT could improve survival results for patients with lymph node metastasis compared with those in whom RP was aborted [Citation10–12]. However, it should be noted that not all patients appeared to benefit from RP. Data from the RP series indicated that disease-free survival decreased with an increasing number of positive lymph nodes, and the overall metastatic burden may determine the post-operative disease course [Citation11]. Considering the metastatic burden, few studies have been concerned with the local treatment for PCa with bone metastases. Recently, Culp et al. [Citation2] analysed the outcomes of patients with mPCa, including those were treated by either brachytherapy, RP or no local treatment, from the SEER database. The 5-year OS and CSS were significantly higher in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy (67.4% and 75.8%, respectively) or brachytherapy (52.6% and 61.3%, respectively) compared to patients without local treatment (22.5% and 48.7%, respectively; p < 0.001). In the report, many M1b patients were included: 61.2% in the RP group (150/245), 58.1% in the brachytherapy group and 70.0% in the control group (5469/7811). To determine if the extent of metastatic disease affected survival among groups, subset analyses were performed based on AJCC M stage. For M1b subset patients, the 5-year OS and CSS were significantly higher in patients undergoing RP (70% and 77.6%, respectively) or brachytherapy (55% and 61.9%, respectively) compared to control patients (22.9% and 48.4%; p < 0.001). Another report from the SEER database [Citation4] showed that three-year OS rate was 73% for RP, 72% for IMRT, 37% for CRT (conformal radiation therapy) and 34% for NLT (no local treatment). The three-year CSS rate was 79% for RP, 82% for IMRT, 49% for CRT and 46% for NLT. After accounting for these and conventional risk factors, RP and IMRT were associated with a 52% and 62% reduction in the risk of the PCa specific mortality, respectively. In this study, the percentage of M1b stage patients were 55% in the RP group, 74% in the IMRT group, 67% in the CRT group and 67% in the NLT group. Unfortunately, in this study, cryoablation was excluded [Citation4]. In the SEER database, the use of cryotherapy increased fourfold from 2001 to 2005 especially for elderly patients, with the advantage of being minimally invasive and less costly [Citation13], and cryoablation showed good results in primary [Citation14] or salvage treatment [Citation15,Citation16]. In our study, the results underlined the important conclusion that cryoablation could be an alternative local treatment for a primary tumour and might exert a significant survival benefit in prostate cancer patients with bone metastases.

However, it should be noted that not all patients appeared to benefit from local treatment. Data from RP series indicated that disease-free survival decreased with an increasing number of positive lymph nodes, and the overall metastatic burden may determine the post-operative disease course [Citation17]. In another investigation based on SEER data, the authors found that local treatment conferred a survival benefit at 3 years after diagnosis only in patients with a CSM (cancer-specific mortality) risk of 40% [Citation18]. Of course, the retrospective approach might introduce a selection bias in which only younger and healthier patients with low metastatic burden were selected for local treatment, and the SEER database did not provide information regarding disease extent and number of metastatic sites. In a recent retrospective cohort study, 23 men with oligometastatic PCa (M1b, three or less hot spots) without bulky pelvic lymph nodes were offered cytoreductive radical prostatectomy (CRP), and the results showed that CRP plus ADT-improved clinical PFS and CSS but not OS [Citation19]. Different from those studies, the patients enrolled in our study had more individual bone metastases and were match paired by site of metastasis, which has been proven to be a prognostic factor in mPCa patients [Citation20]. The results were still encouraging in that cryoablation for the primary tumour did prolong the OS and CSS compared with ADT alone. It is worth mentioning that the patients with bone pain were excluded in our study, since additional radiotherapy treatment might be applied. No bone pain symptoms may contribute to the better results in this study, while bone pain was proven to be one predictor of progression in one retrospective survival analysis [Citation21].

More investigations should focus on prognosis factors, including informative genomic profiling of primary specimens [Citation22], the oncological response to systemic treatment (such as ADT or chemotherapy) [Citation23], the synthetic modality (neoadjunctive ADT or adjunctive ADT) [Citation24], and even the immune response after treatment (such as the cryoimmunologic response) [Citation25]. These studies could identify prognostic markers and ultimately guide-targeted treatment. More clinical evidence is needed to evaluate these conditions and to provide information about selection bias in the decision to proceed. Fortunately, one multicentre, randomised phase-II trial of the best systemic therapy or best systemic therapy plus definitive local therapy (radiation or surgery) of primary tumour in mPCa (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01751438) is under way in North America [Citation26]. The trial is open to patients with all volumes of mPCa. Data from this trial should provide further insight into which patients may benefit from local therapy in addition to systemic treatment.

Additionally, cryoablation for the primary tumour reduced the complication rates of the lower and upper urinary tract as reported in recent publications [Citation18,Citation27], which showed that RP or EBRT reduced the bladder outlet obstruction. This would be another reason for advanced stage patients to accept a minimally invasive local treatment.

The limitations of our study included the small number of patients, the heterogeneity of the groups, retrospective analysis, and some selective bias.

Conclusions

Cryoablation is an optional treatment for local prostate cancer. In this study, cryoablation plus ADT was showed to be a treatment option in the multimodality management of metastatic prostate cancer. Further investigations are warranted.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. (2015). Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 136:E359–86.

- Culp SH, Schellhammer PF, Williams MB. (2014). Might men diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer benefit from definitive treatment of the primary tumor? A SEER-based Study. Eur Urol 65:1058–66.

- Gratzke C, Engel J, Stief CG. (2014). Role of radical prostatectomy in metastatic prostate cancer: data from the Munich Cancer Registry. Eur Urol 66:602–3.

- Satkunasivam R, Kim AE, Desai M, et al. (2015). Radical prostatectomy or external beam radiation therapy vs no local therapy for survival benefit in metastatic prostate cancer: a SEER-Medicare analysis. J Urol 194:378–85.

- Babaian RJ, Donnelly B, Bahn D, et al. (2008). Best practice statement on cryosurgery for the treatment of localized prostate cancer. J Urol 180:1993–2004.

- Guo Z, Si T, Yang X, Xu Y. (2015). Oncological outcomes of cryosurgery as primary treatment in T3 prostate cancer: experience of a single centre. BJU Int 116:79–84.

- Chin JL, Ng CK, Touma NJ, et al. (2008). Randomized trial comparing cryoablation and external beam radiotherapy for T2C-T3B prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 11:40–5.

- Chin JL, Al-Zahrani AA, Autran-Gomez AM, et al. (2012). Extended followup oncologic outcome of randomized trial between cryoablation and external beam therapy for locally advanced prostate cancer (T2c-T3b). J Urol 188:1170–5.

- Donnelly BJ, Saliken JC, Brasher PM, et al. (2010). A randomized trial of external beam radiotherapy versus cryoablation in patients with localized prostate cancer. Cancer 116:323–30.

- Frohmüller HG, Theiss M, Manseck A, Wirth MP. (1995). Survival and quality of life of patients with stage D1 (T1-3 pN1-2M0) prostate cancer. Radical prostatectomy plus androgen deprivation versus androgen deprivation alone. Eur Urol 27:202–6.

- Engel J, Bastian PJ, Baur H, et al. (2010). Survival benefit of radical prostatectomy in lymph node-positive patients with prostate cancer. Eur Urol 57:754–61.

- Gakis G, Boorjian SA, Briganti A, et al. (2014). The role of radical prostatectomy and lymph node dissection in lymph node-positive prostate cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Urol 66:191–9.

- Roberts CB, Jang TL, Shao YH, et al. (2011). Treatment profile and complications associated with cryotherapy for localized prostate cancer: a population-based study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 14:313–9.

- Marien A, Gill I, Ukimura O, et al. (2014). Target ablation-image-guided therapy in prostate cancer. Urol Oncol 32:912–23.

- Peters M, Moman MR, van der Poel HG, et al. (2013). Patterns of outcome and toxicity after salvage prostatectomy, salvage cryoablation and salvage brachytherapy for prostate cancer recurrences after radiation therapy: a multi-center experience and literature review. World J Urol 31:403–9.

- Kongnyuy M, Berg CJ, Kosinski KE, et al. (2017). Salvage focal cryosurgery may delay use of androgen deprivation therapy in cryotherapy and radiation recurrent prostate cancer patients. Int J Hyperthermia 29:1–4.

- Schiavina R, Borghesi M, Brunocilla E, et al. (2013). Differing risk of cancer death among patients with lymph node metastasis after radical prostatectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection: identifcation of risk categories according to number of positive nodes and Gleason score. BJU Int 111:1237–44.

- Fossati N, Trinh QD, Sammon J, et al. (2015). Identifying optimal candidates for local treatment of the primary tumor among patients diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer: A SEER-based Study. Eur Urol 67:3–6.

- Heidenreich A, Pfister D, Porres D. (2015). Cytoreductive radical prostatectomy in patients with prostate cancer and low volume skeletal metastases: results of a feasibility and case-control study. J Urol 193:832–8.

- James ND, Sydes MR, Mason MD, et al. (2012). Celecoxib plus hormone therapy versus hormone therapy alone for hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: first results from the STAMPEDE multiarm, multistage, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 13:549–58.

- Koo KC, Park SU, Kim KH, et al. (2015). Predictors of survival in prostate cancer patients with bone metastasis and extremely high prostate-specific antigen levels. Prostate Int 3:10–5.

- Sverrisson EF, Nguyen H, Kim T, Pow-Sang JM. (2014). Primary cryoablation for clinically localized prostate cancer–do perioperative tumor characteristics correlate with post-treatment biopsy results? Urology 83:376–8.

- Tzelepi V, Efstathiou E, Wen S, et al. (2011). Persistent, biologically meaningful prostate cancer after 1 year of androgen ablation and docetaxel treatment. J Clin Oncol 29:2574–81.

- Grossgold E, Given R, Ruckle H, Jones JS. (2014). Does neoadjuvant androgen deprivation therapy before primary whole gland cryoablation of the prostate affect the outcome? Urology 83:379–83.

- Si TG, Wang JP, Guo Z. (2013). Analysis of circulating regulatory T cells (CD4 + CD25 + CD127-) after cryosurgery in prostate cancer. Asian J Androl 15:461–5.

- MD Anderson Cancer Center Best systemic therapy or best systemic therapy (BST) plus definitive treatment (radiation or surgery) [identifier NCT01751438]. ClinicalTrials.gov. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01751438.

- Won AC, Gurney H, Marx G, et al. (2013). Primary treatment of the prostate improves local palliation in men who ultimately develop castrate-resistant prostate cancer. BJU Int 112:E250–5.