Abstract

Purpose: The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of preoperative pregabalin on postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of hepatic focal lesions (HFLs).

Methods: This randomised controlled study was carried out on 70 adult patients for whom RFA was indicated to treat hepatocellular carcinoma. They were randomised into two groups: Group I: 35 patients who were given a placebo before the procedure and Group II: 35 patients who were given 150 mg of oral pregabalin one hour before the procedure. The primary outcome was the analgesic effect in the form of postoperative pain severity and the need for opioid analgesics.

Results: In the immediate postoperative period there was no significant difference between the two groups on pain assessment by the visual analogue pain scale (VAS Pain; p = 0.84). However, the medians of Group II VAS Pain were significantly (p < 0.001) less than Group I 3,2,1,1,1,0 vs. 4,3,3,2,2,2, respectively when measured every four hours until 24 hours. The number of required doses of rescue analgesia and total required dose of morphine in the first 48 hours postoperatively of Group II were significantly (p < 0.001) less than Group I. Side effects such as nausea and vomiting and delayed discharge were significantly less frequent in Group II when compared with Group I:20vs. 45.7%, 17.1 vs. 45.7% and 11.4 vs. 37.1%, respectively (p = 0.02, 0.01 and 0.01, respectively).

Conclusion: Pre-emptive oral pregabalin is safe and effective for postoperative analgesia in patients scheduled for radiofrequency ablation of focal lesions in liver.

Introduction

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is an established method for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in patients who are not candidates for liver transplantation or those in whom surgical resection cannot be performed [Citation1,Citation2]. Multiple complications may follow radiofrequency ablation like haemorrhage, abscess formation, tracking and postoperative pain [Citation3].

It is common to have some pain following radiofrequency ablation of liver cancer that can last for a few days and is usually mild [Citation4]. Poorly managed acute pain that might occur following radiofrequency ablation of liver focal lesions can produce pathophysiologic processes in both the peripheral and the central nervous systems that have detrimental acute and chronic effects [Citation5]. Improving postoperative pain control accelerates the patient’s ability to resume daily activities [Citation6].

The most commonly used analgesics in the perioperative setting are opioids which are well known for their multiple untoward side effects. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Task Force 2012 guidelines recommended the increased use of non-opioid agents and limitation of opioids to the role of adjuncts when needed [Citation7]. This necessitates the consideration of other methods to control pain after surgery, such as pre-emptive analgesia [Citation8].

Pregabalin is a structural analogue of the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid, but is not functionally related to it [Citation9]. High oral bioavailability is the main advantage of pregabalin over gabapentin resulting in predictable dose-dependent responses and a short titration period that is better tolerated by patients [Citation10].

The management of acute pain after surgery has been attempted by the use of pregabalin. Although pregabalin may prevent central sensitisation and potentially reduce chronic pain, its use in the acute setting is gaining greater importance particularly when included in multimodal analgesia regimens [Citation11].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of preoperative pregabalin on postoperative analgesia in patients scheduled for radiofrequency ablation of hepatic focal lesions.

Patients and methods

This randomised controlled study was carried out on 70 adult patients with HCC presenting to the Tropical Medicine department, Tanta University Hospital for radiofrequency ablation of hepatic focal lesions (HFLs).

The duration of the study was six months starting immediately after obtaining the institutional ethical committee approval. Any unexpected risks appearing during the course of the study were to be cleared to the participants and ethical committee on time and proper measures need to be taken to overcome or minimise them as required by the ethical committee. An informed written consent was taken from each patient. All patients data were confidential, coded and used solely for the current study. The study was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03151213). The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a prior approval by the institution’s human research committee.

The patients included in this study were males and females aged between 40 and 60, having a Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) score of A or B and presenting with malignant focal lesions of the liver, indicated for RFA of the tumour at the Tanta University hospital.

Patients were excluded from the study if they refused to participate, were CTP class C patients, were suffering from pre-operative pain, severe hepatic encephalopathy, advanced renal impairment, peptic ulceration, coagulation defects or cerebral stroke. Patients dependent on opioids, or patients with known or suspected hypersensitivity to pregabalin, as well as patients with a history of previous intervention for HCC or extra-hepatic malignancies were also not included in the study.

Patients included in the study were randomly allocated (using a closed envelope method) into two groups of 35 patients each. Group I (Placebo group; n = 35): patients in this group received placebo tablets similar in form to pregablin tablets one hour before the procedure. Group II (Pregabalin group; n = 35): patients in this group received 150 mg of oral pregabalin one hour before the procedure. Preoperative evaluation of the patients was performed by thorough history taking, complete clinical examination, BMI calculation, laboratory investigation and assessment of the class of cirrhosis by the CTP score. Patients were fully informed and reassured, before entering the operating theatre for their RFA procedure. All patients in the study were subjected to through history taking stressing on the demographic data such as age and sex, calculation of the body mass index (BMI), complete clinical examination and assessment of CTP score

All resuscitation equipment and medication were prepared and checked. An intravenous 22 gauge peripheral cannula was inserted into each patient and monitoring was performed by three lead electrocardiogram, pulse oximetry and non-invasive blood pressure measurement. Supplemental oxygen (3–4 l/min) was given via a nasal cannula to all cases during the procedure and 10 ml/kg ringer solution was administered by intravenous infusion.

All patients were sedated with propofol 1 mg/kg and fentanyl 1 μg/kg followed by subcutaneous injection of 8 ml of a pre-mixed mixture of lidocaine 1% and plain bupivacaine 0.25% at the site marked for introduction of the radiofrequency needle.

After ensuring adequate sedation of the patient and local anaesthetic infiltration, RFA was performed by an experienced team of interventional radiologists.

RFA was performed using 20 cm long, 18 G, cooled-tip RF electrodes with 2–3 cm long exposed metallic tips (Radionics, Burlington, MA). The electrodes were attached to a 500 kHz RF generator (series cc-1; Radionics) capable of producing 200 W of electricity.

The RFA needle was introduced under ultrasound guidance into the HFL to be ablated. RFA was carried out until the tumour became completely hyper-echoic; as a result, the average session lasted about 13 min. After completion of ablation, the patients were transferred to the recovery room for assessment of pain and observation for development of complications.

The visual analogue pain scale (VAS Pain) was recorded immediately after the procedure (T0), then every 4 h for the following 24 h (T1, T2, T3,T4, T5 and T6). Pain was considered to be moderate when the VAS score was 4–6, while severe pain was considered when the VAS Pain score was seven or higher.

Patients who reported moderate to severe postoperative pain received rescue analgesia in the form of 5 mg of morphine intravenously, which was repeated if needed provided that the total daily dose did not exceed 30 mg. The number of required doses of rescue analgesia in the first 48 h postoperatively, as well as any side effects such as bradycardia, hypotension, hypoxia, nausea or vomiting were recorded. Bradycardia was defined as a decrease in heart rate below 50 B/min, hypotension as a decrease in mean arterial pressure by more than 20 mmHg and hypoxia as a decrease in peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (Spo2) to less than 90% [Citation12].

Bradycardia was managed by 0.3 mg intravenous atropine, while, hypotension was managed by ephedrine 10 mg and ringer lactate 5 ml/kg intravenously. Hypoxia was managed by adequate airway management and oxygenation. Delay in the hospital discharge was considered when discharge was later than 24 h post procedure and was reported as Y. Our primary outcome was the analgesic effect in the form of the severity of postoperative pain and the need for opioid analgesics. Our secondary outcome was the safety of the drug in the form of occurrence of side effects.

Statistical analysis

The statistical differences between the studied groups were tested using unpaired t-test for numerical variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. VAS Pain was analysed with Mann–Whitney U test. Statistical tests were performed using SPSS (SPSS, Chicago, IL,Version 23). p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

There was no significant difference between the studied groups concerning age, sex, CTP class, BMI, location of the tumour, size of the tumour or the number of focal lesions (p = 0.50, 0.63, 0.81, 0.98, 0.55, 0.62and 0.30, respectively; ).

Table 1. Patient characteristics of the studied groups.

Regarding VAS Pain score in the studied groups there was no significant difference between both groups immediately postoperative (p = 0.84). However, the VAS Pain in Group II at T1, T2, T3, T4, T5 and T6 was significantly less than that of Group I (p < 0.001). The medians at T1, T2, T3, T4, T5 and T6 were 3, 2, 1, 1, 1, 0 in Group II compared with 4, 3, 3, 2, 2, 2 in Group I, respectively ().

Table 2. VAS Pain score in the studied groups.

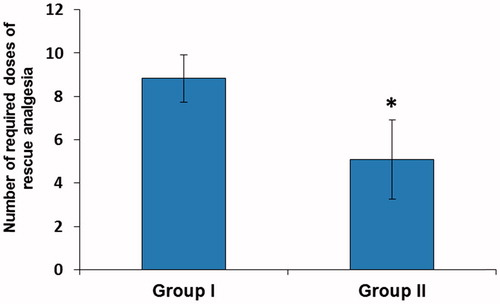

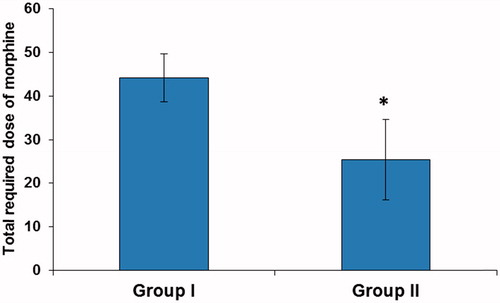

Moreover, the number of required doses of rescue analgesia and total required dose of morphine in the first 48 postoperative hours were significantly lower in Group II compared with Group I (p < 0.001). The mean number of required doses of rescue analgesia were 8.83 ± 1.10 and 5.09 ± 1.84 mg in group I and II, respectively and the mean total required dose of morphine in the first 48 h was 44.14 ± 5.49 and 25.43 ± 9.19 mg in Group I and II, respectively ( and ).

Figure 1. Number of required doses of rescue analgesia. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. *p < 0.001 vs. Group I.

Figure 2. Total required dose of morphine in the first 48 h postoperatively. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. *p < 0.001vs. Group I.

Regarding the frequency of the side effects in the studied groups; nausea and vomiting and delayed discharge were significantly less frequent in Group II compared with Group I:17.1vs. 45.7% and 11.4vs. 37.1%, respectively (p = 0.02, 0.01 and 0.01 respectively). However, there was no significant difference in the frequency of hypotension or hypoxia between Group I and II (p = 0.74 and 0.53, respectively; ).

Table 3. Side effects in the studied groups.

Discussion

The advantages of RFA include performance in an outpatient setting, low morbidity, few complications and repeatability for recurrence of lesions [Citation13]. However, one of the main problems of RFA is pain due to the procedure, even with proper conscious sedation. Pain may be experienced during the ablation procedures, for several days or occasionally up to 1 weeks post procedure [Citation14].

Second-generation antiepileptic medication pregabalin is an approved agent with documented efficacy for painful neuropathies that does not undergo extensive hepatic metabolism or protein binding and is eliminated unchanged via the kidneys [Citation15,Citation16]. To our knowledge, this is the first randomised controlled study to assess the effect of pregabalin on the severity of post-operative pain and the need for opioid analgesics as well as the safety of the drug in patients undergoing radiofrequency ablation of HFLs.

There was no statistically significant difference between the two studied groups regarding factors that may affect pain perception such as age, sex, weight and CPT score [Citation17,Citation18]. Despite there being no significant difference between the two studied groups regarding VAS Pain score immediately post-operative, a highly significant difference in VAS Pain score between the two groups was recorded during the following 24 h. Pregabalin showed high efficacy in decreasing pain in Group II compared to Group I and patients receiving pregabalin had decreased need for post-operative analgesics.

Our results were in accordance with results of studies on pregabalin and gabapentin use preoperatively for indications other than RFA, namely those reported by Reuben et al. [Citation19], who studied patients undergoing spinal fusion surgery and found that pregabalin use in a dose of 150 mg preoperatively and repeated after 12 h led to decreased postoperative opioid consumption in those patients. Also Kumar et al. [Citation20], who concluded that the use of a preoperative dose of 150 mg pregabalin in patients undergoing lumbar laminectomy led to a decrease in postoperative pain scores and reduced total dose of postoperative fentanyl and diclofenac needed in the first 6 h postoperatively.

Our results were also in agreement with those of Alimian et al. [Citation21], who stated that administration of 300 mg pregabalin reduced the post-operative pain in obese patients after gastric bypass surgery. Premkumar et al. [Citation22] studied the pre-emptive effect of oral gabapentin 300 mg on patients undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy and found that there was also a significant reduction in the post-operative pain and analgesic need during the first 24 h post operatively.

On the other hand, a meta-analysis in 2011 indicated that administration of pregabalin had led to significant reduction in the doses of opioids during the first 24 h period following the operation, yet made no difference in pain intensity during the first 24 h following surgery [Citation23].

A study by Bornemann-Cimenti et al. [Citation24], on patients undergoing transperitoneal nephrectomy also reported that a preoperative dose of 300 mg pregabalin resulted in reducing postoperative opioid consumption but pain scores remained unchanged. This may be due to the type of operation and incision which may be associated with hyperalgesia which has been suggested to be a primary factor in incisional pain by some authors [Citation25,Citation26].

Regarding side effects, there were no significant differences between the two studied groups regarding blood pressure or oxygen saturation. However, patients in the group receiving pregabalin had fewer side effects in the form of nausea and vomiting and patients were discharged earlier than those in the other group. Similar results were obtained by Alimian et al. [Citation21] who concluded that nausea and vomiting decreased post operatively with the use of pregabalin.

This study was limited by being a single centre study at a tertiary care setting, therefore, the results need to be confirmed by bigger studies on larger groups of patients. In conclusion, oral preoperative pregabalin is safe and effective for postoperative analgesia in patients scheduled for RFA of focal lesions in liver.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the HCC patients, authorities and the staff of the interventional radiology and Hepatoma group, Tanta University Hospital that collaborated in the study, making this research possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Bruix J, Sherman M. Practice Guidelines Committee, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. (2005). Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 42:1208–36.

- Sheta E, El-Kalla F, El-Gharib M, et al. (2016). Comparison of single-session transarterial chemoembolization combined with microwave ablation or radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized-controlled study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 28:1198–203.

- Tateishi R, Shiina S, Teratani T, et al. (2005). Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. An analysis of 1000 cases. Cancer 103:1201–9.

- Baère T, Risse O, Kuoch V, et al. (2003). Adverse events during radiofrequency treatment of 582 hepatic tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol 181:695–700.

- Joshi GP, Ogunnaike BO. (2005). Consequences of inadequate postoperative pain relief and chronic persistent postoperative pain. Anesthesiol Clin North Am 23:21–36.

- White PF, Kehlet H, Neal JM, et al. (2007). The role of the anesthesiologist in fast-track surgery: from multimodal analgesia to perioperative medical care. Anesth Analg 104:1380–96.

- American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management (2012). Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting: an updated report by the American Society of anesthesiologists task force on acute pain management. Anesthesiology 116:248–73.

- Amiri HR, Mirzaei M, Mohammadi MTB, Tavakoli F. (2016). Multi-modal preemptive analgesia with pregabalin, acetaminophen, naproxen, and dextromethorphan in radical neck dissection surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Anesth Pain Med 6:e33526.

- Ben-Menachem E. (2004). Pregabalin pharmacology and its relevance to clinical practice. Epilepsia 45:13–18.

- Sinatra RS, Jahr JS, Watkins–Pitchford JM. (2011). Overview and use of antidepressant analgesics in pain management. In: The essence of analgesia and analgesics. New York (NY): Cambridge University Press, 338–46.

- Agarwal A, Gautam S, Gupta D, et al. (2008). Evaluation of a single preoperative dose of pregabalin for attenuation of postoperative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Anaesth 101:700–4.

- Mancano MA. (2017). ISMP adverse drug reactions: pregabalin-induced stuttering nitroglycerine-induced bradycardia progressing to asystole minocycline-induced DRESS leading to liver transplantation and type 1 diabetes increased risk of vertebral fractures in women receiving thiazide or loop diuretics gambling disorder and impulse control disorder with aripiprazole. Hosp Pharm 52:253–7.

- Dupuy DE, Goldberg SN. (2001). Image-guided radiofrequency tumor ablation: challenges and opportunities – Part II. J Vasc Interv Radiol 12:1135–48.

- Livraghi T, Solbiati L, Meloni MF, et al. (2003). Treatment of focal liver tumors with percutaneous radio-frequency ablation: complications encountered in a multicenter study. Radiology 226:441–51.

- Dworkin RH, Corbin AE, Young JP, et al. (2003). Pregabalin for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology 60:1274–83.

- Bockbrader HN, Wesche D, Miller R, et al. (2010). A comparison of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pregabalin and gabapentin. Clin Pharmacokinet 49:661–9.

- Li SF, Greenwald PW, Gennis P, et al. (2001). Effect of age on acute pain perception of a standardized stimulus in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 38:644–7.

- Palmeira CC, Ashmawi HA, Posso Ide P. (2011). Sex and pain perception and analgesia. Rev Bras Anestesiol 61:814–28.

- Reuben SS, Buvanendran A, Kroin JS, Raghunathan K. (2006). The analgesic efficacy of celecoxib, pregabalin and their combination for spinal fusion surgery. Anesth Analg 103:1271–7.

- Kumar KP, Kulkarni DK, Gurajala I, Gopinath R. (2013). Pregabalin versus tramadol for postoperative pain management in patients undergoing lumbar laminectomy: a randomized, double blinded, placebo controlled study. J Pain Res 6:471–8.

- Alimian M, Imani F, Faiz SHR, et al. (2012). Effect of oral pregabalin premedication on post-operative pain in laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery. Anesth Pain 2:12–16.

- Premkumar RJP, Biju ML, Wilson MP, et al. (2016). Effect of pre-emptive analgesia with Gabapentin on post-operative pain relief after total abdominal hysterectomy. Int J Biomed Res 7:638–46.

- Zhang J, Ho KY, Wang Y. (2011). Efficacy of pregabalin in acute postoperative pain: a meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 106:454–62.

- Bornemann-Cimenti H, Lederer AJ, Wejbora M, et al. (2012). Preoperative pregabalin administration significantly reduces postoperative opioid consumption and mechanical hyperalgesia after transperitoneal nephrectomy. Br J Anaesth 108:845–9.

- Brennan TJ, Zahn PK, Pogatzki-Zahn EM. (2005). Mechanisms of incisional pain. Anesthesiol Clin North Am 23:1–20.

- Pogatzki-Zahn EM, Zahn PK, Brennan TJ. (2007). Postoperative pain-clinical implications of basic research. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 21:3–13.