Abstract

Objective: The study objective was to retrospectively evaluate the efficacy and safety of radiofrequency endometrial ablation in treating heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) in women with chronic renal failure (CRF).

Method: Fifty-eight patients with CRF undergoing radiofrequency endometrial ablation in our hospital between January 2013 and July 2017 and for whom complete follow-up data were available were included. Outcome measures included amenorrhea, treatment failure and operative complications.

Results: The mean patient age was 41.4 ± 7.7 years, the mean preoperative hemoglobin level was 69.6 ± 19.3 g/dL, the mean preoperative serum creatinine level was 879.1 ± 415.4 µmol/L, and the mean urea level was 18.2 ± 7.1 mmol/L. The mean treatment time for radiofrequency endometrial ablation was 61.7 ± 18.8 s. The median volume of estimated blood loss during the procedure was 10 mL (a range of 2–50 mL). On average, the study subjects were monitored for 24.4 months (a range of 6–60 months). The average amenorrhea rate was 89.7%. Only 2 (3.4%) patients required additional gynecologic surgery after endometrial ablation. Intra- and postoperative complications were not observed.

Conclusion: Radiofrequency endometrial ablation was demonstrated to be safe and effective for the treatment of HMB in women with CRF.

Introduction

The definition of heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB), also known as menorrhagia, is excessive menstrual blood loss that interferes with the physical, emotional, social, and material quality of life of women [Citation1]. Heavy menstrual bleeding is one of the most common complaints with which patients present at a gynecologist and is estimated to affect ∼30% of women of reproductive age [Citation2]. It has been reported that women with HMB have a high prevalence of iron deficiency anemia and reduced quality of life.

Chronic renal failure (CRF) is characterized by a gradual and permanent reduction in both the homeostatic and emunctory function of the kidneys. The incidence of CRF is ∼200 cases per one million people in Western countries [Citation3]. CRF in women is frequently accompanied by disturbances to endocrine function, leading to menstrual disorders that occur in 64.2% of women with CRF [Citation4]. Uncontrolled HMB is a significant problem in subjects with chronic anemia due to renal disease as it leads to aggravation or worsening of the anemia.

Traditionally, the initial management of patients with HMB has comprised medical treatment, such as the administration of hormonal therapy. Hysterectomy is relegated to women for whom other therapeutic options have failed, been contraindicated, or refused [Citation1]. However, the optimal management of HMB in women with CRF has not been established. It is challenging to treat HMB in women with CRF because hormonal treatments are not suitable for certain women or they may refuse to take them, while the potential for major complications (either intra- or postoperatively) is a significant concern with hysterectomy.

Endometrial ablation is a minimally invasive alternative for the treatment of HMB and is associated with high levels of patient satisfaction [Citation5]. Radiofrequency endometrial ablation has been shown to be one of the most effective second-generation techniques in the treatment of HMB and is associated with a high amenorrhea rate and low risk of complications [Citation6]. However, limited data exist on radiofrequency endometrial ablation for the treatment of HMB in women with CRF, and the efficacy and safety of its use has not been well established in this population. Coagulation system function is already profoundly altered in patients with CRF and encompasses insufficient platelet function, changes to the coagulation cascade, and/or activation of the fibrinolytic system. These changes may influence the efficacy of radiofrequency endometrial ablation in this population. Moreover, patients with CRF are prone to episodic infections, volume overload, and an osmolarity/electrolyte imbalance that may impact on the safety of radiofrequency endometrial ablation in these subjects. Thus, the current study objective was to investigate the efficacy and safety of radiofrequency endometrial ablation in treating HMB in women with CRF.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

The current retrospective cohort study was performed in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, China, between January 2013 and July 2017. The procedure was approved by the hospital’s ethics committee and institutional review board. Patients were identified by conducting a search of available electronic medical records. Only women who provided consent for their medical records to be used for research purposes were included in the analysis. Inclusion criteria were patients:

With HMB (based on a pictorial blood loss assessment chart score of ≥185) [Citation7].

With a CRF diagnosis.

Not seeking to preserve their fertility.

With a normal uterine cavity or an abnormality that could be corrected using a hysteroscopic procedure.

The only exclusion criterion was findings on biopsy consistent with complex atypical hyperplasia. Prior to surgery, the patients underwent a comprehensive gynecologic evaluation that included a pelvic examination, a transvaginal ultrasound, and a Papanicolaou test. None of them received hormonal pretreatment for endometrium ablation. Data on age, gravidity, parity, clinical manifestations, previous treatments, the findings of the physical examination, estimated intra-operative blood loss, uterine length and length of hospitalization were collected from a review of the electronic medical records and telephone interviews.

Suction curettage prior to endometrial ablation

Although uterine pretreatment is not required for the NovaSure® procedure, it is our experience that suction curettage prior to endometrial ablation potentially improves the rate of amenorrhea. As the latter is considered to be of great consequence in patients with CRF, suction curettage procedure was performed under general anesthesia with the patient placed in a dorsal lithotomy position. A 30-degree angle view afforded by a diagnostic hysteroscope was used to visualize the uterine cavity. Thereafter, a 7- or 8-mm suction cannula was inserted into the uterine cavity, with the vacuum pressure set at 0.02–0.04 MPa. An experienced gynecologist (not the same one for every procedure) moved the cannula back and forth, rolling it gently to detach the endometrial tissue and remove the distension medium from the cavity.

Radiofrequency endometrial ablation

A NovaSure® device (Hologic, Marlborough, MA) was used to perform the radiofrequency endometrial ablation procedure. The NovaSure® endometrial ablation system comprises a radiofrequency generator, a disposable ablation device, a suction line desiccant and a carbon dioxide canister [Citation6]. It also contains an intrauterine measuring system that was used in the current to determine the width of the uterine cavity. The uterine cavity width and length data were used by the RF controller to calculate the appropriate amount of power output needed to ensure complete ablation of the endometrium. The radiofrequency endometrial ablation procedure was performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, the details of which have previously been described [Citation8].

Follow-up observations

The rate of amenorrhea, defined as the onset of amenorrhea for a minimum of six months immediately after ablation and continuing until the last follow-up, was the primary study outcome. The rate of endometrial ablation failure and intra- and postoperative complications were recorded. Endometrial ablation failure was defined as the need for additional gynecologic surgery after endometrial ablation after a specific follow-up period. Potential complications included uterine perforation, bowel injury, urinary tract injury, carbon dioxide embolism, bleeding, infection, device failure, endometrial cancer, pregnancy and mortality during or after the procedure.

Statistical analysis

Statistical Program for the Social Sciences® version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used to calculate the descriptive statistics/statistical analysis. The normally distributed continuous data were presented as mean ± standard deviation, the not normally distributed continuous data as the median and range, and both of these as the number of subjects (n) or percentage (%).

Results

Fifty-eight women with CRF underwent radiofrequency endometrial ablation to treat HMB. Their demographic and clinical characteristics are described in . The mean age of the patients was 41.4 ± 7.7 years, with a median parity of 1 (range of 0–5). Eight of the subjects had undergone a previous cesarean section in our study. Prior to presenting at our hospital, 28 of the patients had previously been treated with tranexamic acid, 30 had received blood transfusions, 29 had undergone curettage to treat HMB, oral progesterone had been administered cyclically to three women and one woman had used the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system.

Table 1. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study cohort.

Uterine polyps, adenomyosis, intermural fibroids, a uterine septum and intrauterine adhesion were identified in 6 (10.3%), 2 (3.3%), 3 (5.2%), 2 (3.4%) and 3 (5.2%), respectively. The mean preoperative serum creatinine, mean urea and mean uric acid levels were 879.1 ± 415.4 µmol/L, 18.2 ± 7.1 mmol/L and 429.6 ± 109.4 µmol/L, respectively. Renal hypertension, secondary hyperparathyroidism, hypertensive cardiovascular disease and systemic lupus erythematosus was found in 58, 7, 6 and 3 patients, respectively. The mean preoperative hemoglobin level was 69.6 ± 19.3 g/dL (95% confidence interval [CI]: 9.62–10.78). A preoperative hemoglobin level of <60 g/dL was reported for 21 subjects.

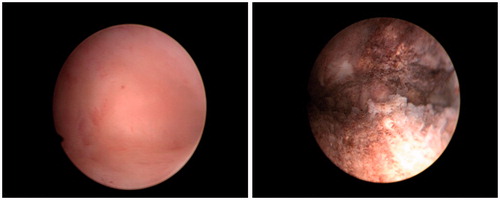

All of the patients successfully underwent radiofrequency endometrial ablation. Completion of the procedure was not impeded by any adverse event. The mean uterine cavity depth and width were 5.2 ± 0.7 cm and 4.2 ± 0.7 cm respectively, and the mean treatment duration for radiofrequency endometrial ablation was 61.7 ± 18.8 s. The median volume of estimated blood loss during the procedure was 10 ml (a range of 2–50 ml). A well-treated cavity was evident on hysteroscopy in all 58 patients after ablation (). The results pertaining to the treatment of HMB in patients with CRF are presented in .

Figure 1. A hysteroscopic view of the endometrial cavity prior to (left) and after (right) NovaSure® endometrial ablation.

Table 2. The results pertaining to the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding in patients with chronic renal failure.

On average, patients were followed-up for 24.4 months after the procedure (a range of 6–60 months). The average rate of amenorrhea was 89.7%. One patient reported spotting for 3–7 days monthly and a further two reported that the same occurred for 2–7 days monthly following ablation during months 17–19. Another patient experienced abdominal pain during the sixth month postoperatively. An anechoic area measuring 50 × 23 mm and representative of uterine effusion were identified on transvaginal ultrasound, leading to a diagnosis of cervical and intrauterine adhesion. The patient opted for hysteroscopic resection of the intrauterine adhesions and endometrial ablation rather than hysterectomy and was amenorrheic after 18 months of follow-up. Another patient reported spotting for 10–20 days monthly (for months 9–22 postoperatively), after which she experienced heavy bleeding for 15 days. She opted for a hysterectomy. The overall endometrial ablation failure rate in the current study was 3.4% (n = 2/58). Intra- and postoperative complications were not reported. There were no diagnoses of endometrial cancer in the follow-up period.

Discussion

Menstrual disorders have been shown to affect 64.2% of women with chronic renal disease [Citation4]. The prevalence of HMB is 22.9%∼38.9%. Menstrual disorders relate to endocrine disorders that are potentially caused by a defect in the hypothalamic regulation of gonadotropin secretion. Heavy menstrual bleeding, a common menstrual symptom in this patient population, is an immediate concern as it exacerbates the chronic anemia associated with renal disease and may necessitate blood transfusion if uncontrolled. Heavy menstrual bleeding has a significant and detrimental impact on the health and quality of life of women. In the current study, the mean preoperative hemoglobin level was 69.6 ± 19.3 g/dL (95% CI: 9.62–10.78) and 21 patients had a hemoglobin level of <60 g/dL.

Treatment options are limited in women with CRF. Erythropoietin is prohibitively expensive and unaffordable for many patients [Citation9]. Information is not available on the pharmacokinetics of any of the progestins for use in chronic renal disease [Citation10]. Medical treatment with cyclical progestogens is generally unhelpful and is compounded by the reduced tolerance of patients with chronic renal disease to hormonal therapy. Prostaglandin synthetase inhibitors are contraindicated in these patients because they constrict the renal artery and have a direct adverse effect on glomerular function [Citation11,Citation12]. Therapeutic curettage provides some relief in certain patients, as opposed to desired high levels of respite in the majority. Thus, women with CRF are more likely to need a hysterectomy at a younger age than the general population. However, hysterectomy is a major surgical intervention and is associated with significant operative risks and complications (e.g., infection, organ injury and postoperative thromboembolism) [Citation13,Citation14]. The introduction of endometrial destructive techniques that remove or destroy endometrial tissue has decreased the number of hysterectomies performed in the UK for benign indications by 64%.

Radiofrequency endometrial ablation has been approved as a potential alternative to hysterectomy for ≥10 years. A significant body of data has been accumulated in this regard during this time, providing a favorable safety profile for the use of this procedure in women requiring treatment for HMB. Amenorrhea rates have been found to range from 30 to 75% in radiofrequency ablation trials [Citation15,Citation16]. Amenorrhea rates at 12 months after radiofrequency endometrial ablation were shown to range from 43 to 56% in randomized controlled trials in which RF endometrial ablation was compared with other global endometrial ablation modalities, while amenorrhea rates for other global endometrial ablation modalities were 8–24% [Citation17–19]. However, data on endometrial ablation in patients with CRF are limited. For this reason, we considered it important to assess the safety and effectiveness of NovoSure® therapy in women with CRF and HMB. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first study to have explored these issues in relation to radiofrequency ablation in patients with CRF and to have determined that it is both efficacious and safe.

The rate of amenorrhea after endometrial ablation was 89.7% in the current study. The incidence of amenorrhea was reported to be 46.2% at the six-month follow-up in the first controlled observational pilot study conducted on radiofrequency endometrial ablation [Citation20]. Elsewhere, it was reported to be 64% at the same time point [Citation21]. Similar rates of amenorrhea have been reported in several other studies. The rate of amenorrhea in our study was higher than that reported in other research. Based on our experience, these results may be attributable to our additional step of always performing suction curettage prior to endometrial ablation. Given the health challenges of and prognosis for the patient population in the current study, the goal was to achieve as high an amenorrhea rate as possible. Performing suction curettage as surgical pretreatment of the endometrium prior to endometrial ablation helps to detach the endometrial tissue from the uterine cavity and removes the distension medium. Most of the patients experienced amenorrhea immediately after ablation for a minimum of six months and this continued until the last follow-up.

The rate of reintervention after radiofrequency endometrial ablation in this study was 3.4%, which is similar to that described in other studies. At the 60-month follow-up, Gallinat reported that only 3 (2.8%) hysterectomy procedures needed to be performed in their cohort of 107 patients [Citation16]. Busund et al. stated that only two (4.4%) of the 45 study participants underwent a hysterectomy (both due to continuous bleeding) at 12 months in their study. Elsewhere, 12 of the 146 women (8.2%) in the study by Baskett required a second surgical treatment over 1–4 years of follow-up, while 10 women underwent a hysterectomy and two had second ablations [Citation21]. The reintervention rate in that study was the highest for prospectively recruited women [Citation22].

The safety of this minimally invasive technique in the treatment of patients with HMB is always a concern. Several complications in relation to endometrial ablation have been reported in the literature, including bleeding, infection, uterine perforation, device failure, injury to the adjacent organs, cardiac arrest, carbon dioxide embolism, sepsis and death [Citation23]. It is recognized that inappropriate application of this procedure and physician error contribute to device-related complications. In the present study, the median volume of estimated blood loss during the procedure was 10 ml (a range of 2–50 ml). Intra- and postoperative complications were not reported. This was mainly owing to the unlikelihood of encountering the aforementioned complications in such a small sample size. In addition, postoperative endometrial cancers were not diagnosed in this cohort during the follow-up period.

Conclusion

The success rate of radiofrequency endometrial ablation when treating HMB in patients with CRF was found to be high in the current study. Specifically, an amenorrhea rate of 89.7% was attained over 24.4 months of follow-up on average. Based on these findings, radiofrequency endometrial ablation appears to be a safe and effective technique for the treatment of HMB in patients with CRF.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Fox KE. Management of heavy menstrual bleeding in general practice. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28:1517–1525.

- Liu Z, Doan QV, Blumenthal P, et al. A systematic review evaluating health-related quality of life, work impairment, and health-care costs and utilization in abnormal uterine bleeding. Value Health. 2007;10:183–194.

- Dioguardi M, Caloro GA, Troiano G, et al. Oral manifestations in chronic uremia patients. Ren Fail. 2016;38:1–6.

- Lin CT, Liu XN, Xu HL, et al. Menstrual disturbances in premenopausal women with end-stage renal disease: a cross-sectional study. Med Princ Pract. 2016;25:260–265.

- Munro MG. Endometrial ablation. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;46:120–139.

- Gimpelson RJ. Ten-year literature review of global endometrial ablation with the NovaSure(R) device. Int J Women's Health. 2014;6:269–280.

- Janssen CA, Scholten PC, Heintz AP. A simple visual assessment technique to discriminate between menorrhagia and normal menstrual blood loss. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:977–982.

- Cooper J, Gimpelson R, Laberge P, et al. A randomized, multicenter trial of safety and efficacy of the NovaSure system in the treatment of menorrhagia. J Am Ass Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9:418–428.

- Trkulja V. Treating anemia associated with chronic renal failure with erythropoiesis stimulators: recombinant human erythropoietin might be the best among the available choices. Med Hypotheses. 2012;78:157–161.

- Anderson GD, Odegard PS. Pharmacokinetics of estrogen and progesterone in chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2004;11:357–360.

- Kovic SV, Vujovic KS, Srebro D, et al. Prevention of renal complications induced by non- steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Curr Med Chem. 2016;23:1953–1964.

- Harirforoosh S, Jamali F. Renal adverse effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2009;8:669–681.

- Wong JMK, Bortoletto P, Tolentino J, et al. Urinary tract injury in gynecologic laparoscopy for benign indication: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;131:1–108.

- Kahr HS, Thorlacius-Ussing O, Christiansen OB, et al. Venous thromboembolic complications to hysterectomy for benign disease: a nationwide cohort study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:715–723.

- Asgari Z, Moini A, Samiee H, et al. Endometrial ablation with the NovaSure system in Iran. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;114:73–75.

- Gallinat A. An impedance-controlled system for endometrial ablation: five-year follow-up of 107 patients. J Reprod Med. 2007;52:467–472.

- Bongers MY, Bourdrez P, Mol BW, et al. Randomised controlled trial of bipolar radio-frequency endometrial ablation and balloon endometrial ablation. BJOG. 2004;111:1095–1102.

- Kleijn JH, Engels R, Bourdrez P, et al. Five-year follow up of a randomised controlled trial comparing NovaSure and ThermaChoice endometrial ablation. BJOG. 2007;115:193–198.

- Clark TJ, Samuels N, Malick S, et al. Bipolar radiofrequency compared with thermal balloon endometrial ablation in the office: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1228.

- Gallinat A, Nugent W. NovaSure impedance-controlled system for endometrial ablation. J Am Ass Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9:283–289.

- Kalkat RK, Cartmill RS. NovaSure endometrial ablation under local anaesthesia in an outpatient setting: an observational study. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;31:152–155.

- Baskett TF, Clough H, Scott TA. NovaSure bipolar radiofrequency endometrial ablation: report of 200 cases. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;27:473–476.

- Moulder JK, Yunker A. Endometrial ablation: considerations and complications. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;28:261–266.