Abstract

Objective: This research was conducted to assess the long-term outcomes of a combination treatment of High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) ablation, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs (GnRHa) and Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) for women with adenomyosis (AD).

Methods: One hundred and forty-two patients with AD were enrolled and treated with HIFU conservative treatment in combination with adjuvant therapy of GnRHa and LNG-IUS. All the cases were followed up to 5 years after treatment. The volumes of uteri, AD lesions, and menstrual blood, and dysmenorrhea scores were measured. Also, the incidences of recurrence and complications were recorded.

Results: Both the uterine and lesion volumes significantly decreased after treatment. The uterine volume gradually reduced after treatment, reaching the lowest level of 122.07 ± 44.12 cm3 at 12 months after treatment, with an average reduction rate of 45%, and then increased slightly, maintaining a reduction rate of about 35% compared with the baseline level. Similar decreases in AD lesion volumes, dysmenorrhea scores, and menstrual flow were also demonstrated. Hemoglobin levels increased. Moreover, the long-term recurrence rates were low, with 5.68% and 7.91% in dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia, respectively. No serious complications or adverse events were reported.

Conclusions: HIFU ablation, in combination with GnRHa and LNG-LUS, might be a safe and effective alternative in the treatment for women with adenomyosis.

Keywords:

Introduction

Adenomyosis (AD) is a common benign gynecologic condition in childbearing age women, in whom invasion or diffusion of the endometrium into the myometrium is often detected [Citation1,Citation2]. The incidence of AD varies from 10% to 30% [Citation3,Citation4]; and the proportion of young women is increasing in recent years [Citation5–7]. The main signs and symptoms of diseased women include menorrhagia, dysmenorrheal, and abnormal uterine bleeding, which would influence the quality of life seriously [Citation8,Citation9]. Moreover, AD is reported to significantly increase the risk of endometrial and thyroid cancer [Citation10].

Traditionally, the usual treatment of choice in women with symptomatic AD is considered to be hysterectomy [Citation11]. However, it is unsuitable for women who wish to remain their fertility [Citation12]. Currently, medical treatment for symptomatic AD manifests an increased efficacy [Citation13]. However, no drug is currently labeled for AD, and the best management is still controversial [Citation13,Citation14].

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs (GnRHa) is synthetic peptide compounds with a similar structure of natural gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). Application of GnRHa will suppress ovarian function by immediately antagonist acting on pituitary GnRH receptors, blocking the secretion of gonadotropins, and inducing profound hypoestrogenism and a state of transient amenorrhea in the following few weeks [Citation13,Citation15]. Amenorrhea might alleviate dysmenorrhea symptom and reduce menstrual blood volume appropriately. Moreover, GnRHa has direct anti-proliferative activity within the myometrium through the interaction with the GnRH receptors [Citation16,Citation17]. Therefore, GnRHa might be involved in the regression of AD with consequent symptom relief [Citation18]. However, GnRHa only alleviates short-term clinical signs, and the symptoms will recur after cessation of this treatment [Citation19,Citation20].

LNG-IUS was initially designed for contraception. It can release 20 mcg/d of levonorgestrel into the uterine cavity for a 5-year period. Besides the contraceptive efficacy of LNG-IUS, it has been proved to be one of the effective and safe options for AD by numerous studies [Citation21–25]. In AD women treated with LNG-IUS for 3 years, there was an overall satisfaction of 72%, with a continued significant decrease in dysmenorrhea and uterine volume compared to baseline [Citation26]. However, the rate of insufficient treatment by LNG-IUS was also reported varying from 4% to 37% [Citation25,Citation27]. Moreover, it seemed that LNG-IUS is not optimal in women with large AD [Citation28]. The combination of GnRHa and ING-IUS has been proved to be safe and effective for large AD [Citation20].

High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) ablation is an emerging noninvasive technology, which is applied to treat patients with various malignant tumors and benign lesions [Citation29–35]. Recently, HIFU is considered as one of the ideal uterine-sparing options for patients with AD [Citation36–38]. A few studies have examined the efficacy and safety of HIFU treatment for patients with symptomatic AD [Citation39–42]. Sustained effect with symptom relief after 12 months was obtained in 88% of 669 cases in a pooled analysis [Citation27]. In addition, the clinical benefits of HIFU included a 25–65% reduction in symptom severity score, increased quality of life score from 39% to 85%, decreased dysmenorrhea up to 86% and mean of 22–54% reduction of uterine volume [Citation27]. Two studies have reported the AD recurrence rate of 5.4–10.3% at one year after HIFU monotherapy [Citation41,Citation43].

The combination of HIFU and GnRHa for the treatment of AD is also reported to decrease volumes of uterus, adenomyotic lesion, and menstrual blood volumes [Citation44]. However, the follow-up is relatively short. Therefore, the long-term efficacy and safety of HIFU ablation and GnRHa for women with AD remained to be assessed.

Materials and methods

Patients

From June 2010 to June 2013, patients with AD were enrolled in our study. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the diagnosis of AD was confirmed by two-dimensional transvaginal ultrasonography (US); (2) women older than 18 years but not menopausal; (3) patients who refused hysterectomy or adenomyectomy, or wanted to retain their uterus of fertility; (4) women with symptom of dysmenorrhea; (5) cases with the thickness between treatment focus and skin of ≥11 cm.

Exclusion criteria included (1) women undergoing pregnancy or lactation; (2) suspicion of malignancy; (3) patients with acute pelvic inflammatory disease.

Procedures

HIFU ablation was performed using the HIFUNIT-9000 system (Shanghai A&S Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China). The patients were placed in the supine position. First, location, size, and morphological characteristic of adenomyosis were identified by external b-mode sonography. Next, the detecting head of this system would complete the re-localization of the therapy area. Finally, the ablation energy focus was controlled to move along with a three-dimensional axis orderly until to cover the target lesions. The main HIFU parameters of treatment in this study were the following: ultrasonic frequency, 1 MHz ± 50KHz; output power, >3000 W/cm2; therapy depth, 2–15 cm; practice-focused sphere,3 × 3 × 8 mm; unit transmit time (t1) 150 × 300 ms; intermission time (t2), 200–400ms; and HIFU times at each lesion, 8–10 times; time spend of single session of HIFU, 40 min; the average power per sonication, 80–100 W. All of the parameters could be varied depending on the depth of the tumor. As adjuvant therapy, within 1 week after the last time of HIFU ablation, GnRHa (triptorelin) was given at a dose of 3.75 mg by intramuscular injection every four weeks for a total of 6 doses. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) was also performed within 1–3 days after the last dose of GnRHa. For the majority of patients, LNG-IUS would be removed after 5 years.

Observation and measurement

Uterine volumes were calculated as an ellipsoid using the following formula: volumes = 0.523 × a × b × c. The variables a, b, and c represent the long diameter, transverse diameter, and anteroposterior diameter of uterine determined by ultrasonography. Moreover, the uterine volume reduction rates from the level before surgery were evaluated. Similarly, the AD lesions volumes and the reduction rates were also calculated. Dysmenorrhea score was evaluated using the visual analog scale (VAS), which was ranged from 0 to 10. 0 points represented no pain; <3 points represented mild pain which could be accepted; 4–6 points represented pain that could affect the patients’ sleep; 7–10 points represented intolerable pain. The menstrual flow was analyzed by Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart (PBAC) method [Citation45]. The measurements were observed before HIFU treatment, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and every year thereafter till five years after HIFU ablation. Pregnancy outcomes were also recorded during the follow-up. Cases who removed ING-IUS were excluded from the following analysis. The response of dysmenorrhea was defined as follows: (1) Complete response (CR): VAS scores reduced by more than 80% compared with baseline levels. (2) Major response (MR): VAS scores improved with a decrease between 50% and 80% from pre-HIFU levels. (3) Partial response (PR): VAS scores decreased by 20% to 50% compared with pre-HIFU levels. (4) No response (NR): VAS scores have a minor decrease (<20%) or even rise from baseline. Dysmenorrhea recurrence was defined as VAS at 12 months, and after that follow-up time points rise back to more than 80% of the level of pre-HIFU ablation after 12 months, among the responding patients at six months after HIFU ablation. The response and recurrence of menorrhagia were defined similarly with the indicator of PBAC. After treatment, all patients were closely observed for complications of HIFU ablation, GnRHa, and LNG-IUS. Mild anemia was defined as a hemoglobin concentration between 90 and 110 g/L; and moderate anemia was defined as a hemoglobin concentration between 60 and 90 g/L.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using the statistical product and service solutions software 15.0 version (SPSS; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Normally, distributed data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Non-normally distributed data were expressed with a median (range). The independent Student’s t-tests or Wilcoxon tests were used to compare data between each time point after treatment and baseline, as appropriate. p Value <0.05 was considered to be a significant difference.

Results

Baseline characteristics

One hundred and fifty-seven women with AD were recruited following the inclusion criteria. After excluding 15 drop-outs, a total of 142 patients finally completed the follow-up and were included in the analysis. The median age of the patients was 39 years (range: 27–46). Most of them (75.35%) were parous women, with a high miscarriage rate of 76.06%. The mean uterine volume per-HIFU ablation was 220.32 ± 78.21 cm3, with uterine anteposition, retroposition and mesoposition in 97, 12, and 33 women, respectively. The numbers of patients with AD lesions located in the anterior wall, posterior wall, fundus, and lateral wall were 51, 77, 11, and 3, respectively. Mean lesion volume was 120.32 ± 18.27 cm3. Thirty-three patients reported mild anemia, and 18 cases reported moderate anemia, with the mean hemoglobin of 94.80 ± 3.62 g/L ().

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of AD patients.

Pregnancy outcome

A total of 29 patients removed LNG-IUS during the follow-up period for personal reasons, mainly for pregnancy desire. Most of them (19/29) stopped LNG-IUS within 12 months after HIFU treatment. A total of 17 (12%) pregnancies were obtained in these women who removed LNG-IUS, of which 15 occurred within 12 months after HIFU treatment. There were nine elective terminations of pregnancy for personal reasons and eight live births. All eight fetuses were normal.

Uterine volumes, AD lesion volumes, and hemoglobin levels

summarizes the uterine volumes, AD lesion volumes, and hemoglobin levels at different follow-up points. Both the uterine and lesion volumes significantly decreased after treatment when compared with pretreatment levels ( and ). The uterine volume gradually reduced after HIFU, reaching the lowest level of 122.07 ± 44.12 cm3 at 12 months after treatment, with an average reduction rate of 45%, then increased slightly, maintaining a reduction rate of about 35% compared with the baseline level. Similar results of AD lesions volumes were detected (). Hemoglobin levels of all the patients climbed from 94.80 ± 3.62 g/L to 143.23 ± 9.03 g/L after 12 months, afterward, declined to 110.67 ± 6.92 g/L after five years. The best average increase rate was 51.62% at 12 months. Among the 51 AD women with anemia, few patients received symptomatic treatment, such as iron and vitamin C supplement (3 cases in mild group and 2 cases in moderate group, respectively), and the vast majority (30 cases in mild group and 15 cases in moderate group, respectively) achieved a relief or disappearance of anemia symptoms after HIFU-based treatment. The relief rate was calculated to be 88.24%.

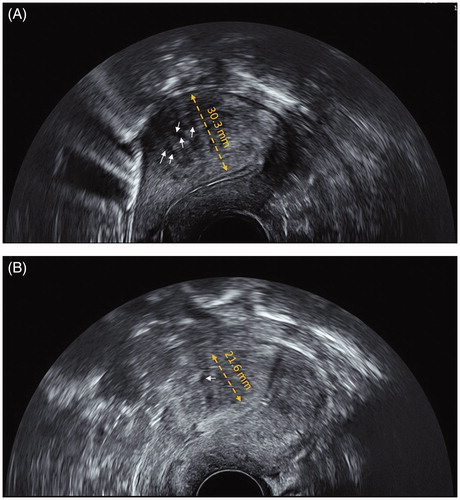

Figure 1. Two-dimensional transvaginal ultrasonography imaging of uterus by GE Voluson E8 color flow ultrasound machine. (A) Before HIFU treatment, the muscular layer of the anterior wall of the uterus was significantly thickened (30.3 mm, yellow bipolar arrow); with multiple hyperechoic striations and tiny myometrial cysts (white arrows) in the interior. Endometrium was asymmetric. (B) Three months after HIFU treatment, the muscular layer of the anterior wall of the uterus was significantly thinned (21.6 mm, yellow bipolar arrow); with few hyperechoic striations and tiny myometrial cysts (white arrow) in the interior. Endometrium was symmetric.

Table 2. Uterine and AD lesions volumes of patients before HIFU and after treatment.

Dysmenorrhea score and menstrual flow analysis

The dysmenorrhea score significantly decreased at each follow-up time compared with baseline. The lowest score was 2.07 ± 1.02, which achieved at 6 months after ablation, followed by a slight increase to 3.03 ± 1.22 at 60 months, with a reduction rate of about 50%. Similarly, the menstrual blood volume had reached a minimum value of 40.17 ± 15.22 ml at 12 months after treatment, with a slight rise subsequently ().

Table 3. Dysmenorrhea score and menstrual flow analysis.

Response rate and recurrence rate

As shown in , the dysmenorrhea response rate of AD women was calculated to be 99.30% at 6 months after treatment and remained above 90% for the following four years. The dysmenorrhea recurrence rate was 1.42% at 24 months after treatment, and then gradually increased to 5.68% at 60 months after treatment. Similarly, the menorrhagia response rate was highest at 12 months after treatment with a rate of 98.47% and the menorrhagia recurrence rate gradually climb to 7.91% at 5 years after ablation.

Table 4. Response rate and recurrence rate after treatment.

Complications and adverse events

During HIFU ablation, slight hematuria occurred in three cases, and all cases were improved after symptomatic treatment. No serious complications occurred. The most common adverse events post-procedure were mild lower abdominal pain (46/142) and minor vaginal blood discharge (33/142). Two cases reported sciatica pain or buttock pain, and the other two reported abdominal distention, which were relieved within one week without symptomatic treatment. After LNG-IUS placement, 47 cases (33.10%) reported abnormal menstruation or irregular vaginal bleeding, three cases (2.11%) reported a headache, and one woman (0.70%) reported breast tenderness.

Discussion

AD is a common gynecological disorder, which seriously affects the quality of life of patients; and the incidence has increased in recent years [Citation44]. It is characterized by endometrial glands and interstitial invasion of the myometrium, therefore, leading to focal or diffuse enlargement of the uterus [Citation46]. However, the boundary of AD is often unclear, and this may cause severe pelvic adhesions. Therefore, for women with AD who wants to retain their fertility, conservative treatment is usually not able to completely remove the lesion, which would cause a high relapse rate [Citation27].

The previous study indicated that combined HIFU and metformin treatment have a superior effect in patients with enlarged adenomyosis compared with single HIFU treatment, even though HIFU monotherapy could significantly reduce menstrual flow and pain [Citation47]. Another report by Guo Y et al. [Citation44] revealed that combination therapy of GnRHa and HIFU could also improve the short-term clinical efficacy of HIFU ablation. These results suggested that HIFU ablation was active for AD and synergized with other agents to improve efficacy.

In the present study, for patients with AD who received HIFU in combination with GnRHa and LNG-IUS, the uterus and the lesion volumes decreased significantly after treatment. In six months after HIFU, the average uterine size was reduced by 45%, and the adenomyotic lesion volume was reduced by 85%. Dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia were also obviously relieved after HIFU treatment. These results were consistent with previous studies in which HIFU ablation was solely applied [Citation38,Citation48]. In a comparative study, the one-year uterine volume reduction rates of HIFU alone, HIFU combined with LNG-IUS, and HIFU combined with GnRHa were 30%, 38%, and 40%, respectively, and adenomyotic lesion shrinkage rates were 44%, 54%, and 54%, respectively [Citation49]. All those results were numerically inferior to our triple therapy, which suggested that HIFU-based triple regimen may provide a superior clinical effect compared to HIFU treatment on its own or combined with GnRHa or LNG-IUS.

As a limitation of all the existing researches, the long-term efficacy was undetected. Most of these studies had a follow-up duration within 1 year [Citation37,Citation49,Citation50]. A study with 2-year follow-up results revealed the dymenorrhea and menorrhagia response rates of 82% and 79%, respectively, by HIFU monothreapy [Citation48], which seemed to be lower than our outcome of 97% and 97% at two years after HIFU treatment. In another study with a median follow-up of 40 months, the relief of dysmenorrhea was observed in 83% cases [Citation51], which was also inferior to our result of 93.5% at 48 months after ablation. Based on the above comparisons, we could speculate that HIFU combined therapy might provide better long-term efficacy than HIFU ablation alone.

As far as we know, no research indicated recurrence status of HIFU-based combination treatment. In fact, only two previous studies evaluated relapses rate of AD, in which HIFU was applied alone [Citation41,Citation43]. The recurrence rate was calculated to be 5.4% to 10.25%. Our result, in contrast, revealed the one-year recurrence rates of dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia were 0% and 0.7%, respectively. This historical comparison between combined therapy and HIFU monotherapy suggested that GnRHa and LNG-IUS have particular effect to prevent recurrence. Our results also demonstrated that HIFU combined with GnRHa and LNG-IUS is safe, as no severe complications or adverse effects were observed.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, our research, which was not a randomized controlled trial, could not be considered as the highest level of evidence for HIFU ablation for patients with AD. Second, the sample size was not large enough, and some patients dropped out during the follow-up. We did not explore the reasons for their dropouts; this might induce a certain degree of bias. Besides, the relationship between AD thickness and outcome was not evaluated by us, which may be a key takeaway [Citation52]. Nevertheless, our study is the first report about the efficacy and safety of combination treatment of HIFU, GnRHa, and LNG-IUS with a long-term follow-up. It might be somewhat valuable in clinical practices.

Based on our results, HIFU conservative treatment combined with GnRHa and LNG-IUS adjuvant therapy could significantly alleviate long-term dysmenorrhea symptoms and reduce uterus and lesion volume in AD patients. Moreover, this treatment could also effectively control the long-term recurrence rate and might be one of the optimal strategies for AD. However, more large-sample and well-designed studies are needed for further evaluation.

Author contributions

Sun Haiyan: study design, statistical analysis, and write this manuscript. Wang Lin: data acquisition, statistical analysis. Huang Shuhua: data acquisition, Wang Wei: data acquisition

Disclosure statement

There is no conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barrier BF, Allison J, Hubbard GB, et al. Spontaneous adenomyosis in the chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes): a first report and review of the primate literature: case report. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(6):1714–1717.

- Dueholm M. Transvaginal ultrasound for diagnosis of adenomyosis: a review. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;20(4):569–582.

- Kim MD, Won JW, Lee DY, et al. Uterine artery embolization for adenomyosis without fibroids. Clin Radiol. 2004;59(6):520–526.

- Lone FW, Balogun M, Khan KS. Adenomyosis: not such an elusive diagnosis any longer. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;26(3):225–228.

- Pinzauti S, Lazzeri L, Tosti C, et al. Transvaginal sonographic features of diffuse adenomyosis in 18–30-year-old nulligravid women without endometriosis: association with symptoms. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46(6):730–736.

- Naftalin J, Hoo W, Pateman K, et al. How common is adenomyosis? A prospective study of prevalence using transvaginal ultrasound in a gynaecology clinic. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(12):3432–3439.

- Chapron C, Tosti C, Marcellin L, et al. Relationship between the magnetic resonance imaging appearance of adenomyosis and endometriosis phenotypes. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(7):1393–1401.

- Garcia L, Isaacson K. Adenomyosis: review of the literature. J Minim Invas Gynecol. 2011;18(4):428–437.

- Kwon YS, Roh HJ, Ahn JW, et al. Conservative adenomyomectomy with transient occlusion of uterine arteries for diffuse uterine adenomyosis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(6):938–945.

- Yeh CC, Su FH, Tzeng CR, et al. Women with adenomyosis are at higher risks of endometrial and thyroid cancers: a population-based historical cohort study. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0194011.

- Di Spiezio Sardo A, Calagna G, Santangelo F, et al. The role of hysteroscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of adenomyosis. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:1.

- Parazzini F, Mais V, Cipriani S, et al. Determinants of adenomyosis in women who underwent hysterectomy for benign gynecological conditions: results from a prospective multicentric study in Italy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;143(2):103–106.

- Vannuccini S, Luisi S, Tosti C, et al. Role of medical therapy in the management of uterine adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(3):398–405.

- Wood C. Surgical and medical treatment of adenomyosis. Hum Reprod Update. 1998;4(4):323–336.

- Morelli M, Rocca ML, Venturella R, et al. Improvement in chronic pelvic pain after gonadotropin releasing hormone analogue (GnRH-a) administration in premenopausal women suffering from adenomyosis or endometriosis: a retrospective study. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29(4):305–308.

- Khan KN, Kitajima M, Hiraki K, et al. Cell proliferation effect of GnRH agonist on pathological lesions of women with endometriosis, adenomyosis and uterine myoma. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(11):2878–2890.

- Ishihara H, Kitawaki J, Kado N, et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist and danazol normalize aromatase cytochrome P450 expression in eutopic endometrium from women with endometriosis, adenomyosis, or leiomyomas. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(Suppl 1):735–742.

- Grow DR, Filer RB. Treatment of adenomyosis with long-term GnRH analogues: a case report. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78(3 Pt 2):538–539.

- Akira S, Mine K, Kuwabara Y, et al. Efficacy of long-term, low-dose gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist therapy (draw-back therapy) for adenomyosis. Med Sci Monit: Int Med J Exp Clin Res. 2009;15(1):CR1–CR4.

- Zhang P, Song K, Li L, et al. Efficacy of combined levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog for the treatment of adenomyosis. Med Princ Pract. 2013;22(5):480–483.

- Shaaban OM, Ali MK, Sabra AM, et al. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system versus a low-dose combined oral contraceptive for treatment of adenomyotic uteri: a randomized clinical trial. Contraception. 2015;92(4):301–307.

- Bragheto AM, Caserta N, Bahamondes L, et al. Effectiveness of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in the treatment of adenomyosis diagnosed and monitored by magnetic resonance imaging. Contraception. 2007;76(3):195–199.

- Cho S, Nam A, Kim H, et al. Clinical effects of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device in patients with adenomyosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(4):373 e1–7.

- Ozdegirmenci O, Kayikcioglu F, Akgul MA, et al. Comparison of levonorgestrel intrauterine system versus hysterectomy on efficacy and quality of life in patients with adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(2):497–502.

- Zheng J, Xia E, Li TC, et al. Comparison of combined transcervical resection of the endometrium and levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine system treatment versus levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine system treatment alone in women with adenomyosis: a prospective clinical trial. J Reprod Med. 2013;58(7–8):285–290.

- Sheng J, Zhang WY, Zhang JP, et al. The LNG-IUS study on adenomyosis: a 3-year follow-up study on the efficacy and side effects of the use of levonorgestrel intrauterine system for the treatment of dysmenorrhea associated with adenomyosis. Contraception. 2009;79(3):189–193.

- Dueholm M. Minimally invasive treatment of adenomyosis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;51:119–137.

- Park DS, Kim ML, Song T, et al. Clinical experiences of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in patients with large symptomatic adenomyosis. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;54(4):412–415.

- Sequeiros RB, Joronen K, Komar G, et al. High intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) in tumor therapy. Duodecim; laaketieteellinen aikakauskirja. 2017;133(2):143–149.

- Albisinni S, Melot C, Aoun F, et al. Focal treatment for unilateral prostate cancer using high-intensity focal ultrasound: a comprehensive study of pooled data. J Endourol. 2018;32(9):797.

- Zhao H, Yang G, Wang D, et al. Concurrent gemcitabine and high-intensity focused ultrasound therapy in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2010;21(4):447–452.

- Ji Y, Hu K, Zhang Y, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) treatment for uterine fibroids: a meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;296(6):1181–1188.

- Lang BHH, Woo YC, Chiu KW. Sequential high intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) ablation in the treatment of benign multinodular goitre: an observational retrospective study. Eur Radiol. 2018;28(8):3237–3244.

- Xiao J, Sun T, Zhang S, et al. HIFU, a noninvasive and effective treatment for chyluria: 15 years of experience. Surg Endosc. 2018;32(7):3064–3069.

- Marinova M, Rauch M, Schild HH, et al. Novel non-invasive treatment with High-intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU). Ultraschall Med. 2016;37(1):46–55.

- Cheung VY. Current status of high-intensity focused ultrasound for the management of uterine adenomyosis. Ultrasonography. 2017;36(2):95–102.

- Feng Y, Hu L, Chen W, et al. Safety of ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation for diffuse adenomyosis: a retrospective cohort study. Ultrason Sonochem. 2017;36:139–145.

- Zhang X, Li K, Xie B, et al. Effective ablation therapy of adenomyosis with ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;124(3):207–211.

- Yoon SW, Kim KA, Cha SH, et al. Successful use of magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound surgery to relieve symptoms in a patient with symptomatic focal adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(5): 2018 e13–5.

- Fukunishi H, Funaki K, Sawada K, et al. Early results of magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound surgery of adenomyosis: analysis of 20 cases. J Minim Invas Gynecol. 2008;15(5):571–579.

- Zhou M, Chen JY, Tang LD, et al. Ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation for adenomyosis: the clinical experience of a single center. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(3):900–905.

- Fan TY, Zhang L, Chen W, et al. Feasibility of MRI-guided high intensity focused ultrasound treatment for adenomyosis. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(11):3624–3630.

- Lee JS, Hong GY, Park BJ, et al. Ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound treatment for uterine fibroid & adenomyosis: a single center experience from the Republic of Korea. Ultrason Sonochem. 2015;27:682–687.

- Guo Y, Duan H, Cheng J, et al. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonist combined with high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation for adenomyosis: a clinical study. BJOG. 2017;124 (Suppl 3):7–11.

- Higham JM, O'Brien PM, Shaw RW. Assessment of menstrual blood loss using a pictorial chart. BJOG. 1990;97(8):734–739.

- Ye MZ, Deng XL, Zhu XG, et al. [Clinical study of high intensity focused ultrasound ablation combined with GnRH-a and LNG-IUS for the treatment of adenomyosis]. Zhonghua fu chan ke za zhi. 2016;51(9):643–649.

- Hou Y, Qin Z, Fan K, et al. Combination therapeutic effects of high intensity focused ultrasound and Metformin for the treatment of adenomyosis. Exp Ther Med. 2018;15(2):2104–2108.

- Shui L, Mao S, Wu Q, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) for adenomyosis: two-year follow-up results. Ultrason Sonochem. 2015;27:677–681.

- Guo Q, Xu F, Ding Z, et al. High intensity focused ultrasound treatment of adenomyosis: a comparative study. Int J Hyperthermia. 2018;35(1):505–509.

- Yang X, Zhang X, Lin B, et al. Combined therapeutic effects of HIFU, GnRH-a and LNG-IUS for the treatment of severe adenomyosis. Int J Hyperthermia. 2019;36(1):486–492.

- Liu X, Wang W, Wang Y, et al. Clinical predictors of long-term success in ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation treatment for adenomyosis: a retrospective study. Medicine. 2016;95(3):e2443.

- Krentel H, Cezar C, Becker S, et al. From clinical symptoms to MR imaging: diagnostic steps in adenomyosis. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:1.