Abstract

Introduction

Microwave endometrial ablation (MEA) is beginning to be used widely in Japan as a minimally invasive alternative to conventional total hysterectomy for functional hypermenorrhea, uterine fibroids, hypermenorrhea due to organic diseases such as uterine adenomyosis, and acute heavy uterine bleeding.

Method

MEA was introduced in our hospital in January 2016. It is performed after a screening via cytodiagnosis and histodiagnosis to ensure that there are no malignant diseases in the uterus. Histopathological examination by endometrial curettage during MEA revealed three cases of endometrial abnormalities. In all cases, radical surgery was performed, the postoperative course was good, and no recurrence was observed. Here, we report three cases in which abnormal endometrial tissue findings were observed in histopathologic examinations via total endometrial curettage during MEA.

Conclusion

When performing MEA, it is important to perform detailed examinations and careful monitoring of post-operative progress bearing in mind potential malignant uterine diseases.

Introduction

Microwave endometrial ablation (MEA) is a treatment method for organic hypermenorrhea due to fibroids or adenomyosis, for hypermenorrhea caused by medication or systemic disease, or for functional hypermenorrhea that is resistant to conservative therapy. It is a minimally invasive treatment method, which can be selected instead of conventional hysterectomy. At our hospital, MEA was introduced as a treatment option for hypermenorrhea in January 2016 and it has been performed on 73 cases as of December 2019. At our hospital, all cases for whom MEA is scheduled undergo cervical and endometrial cytodiagnosis before admission. If abnormalities are found in the cytological results, a histopathological examination is performed to exclude malignant uterine lesions. A biopsy of the cervix is performed using colposcopy, and the biopsy is examined histologically and a diagnosis is made. Histopathological examination of the endometrium is performed based on full-scale endometrial resection. MEA is performed on the entire endometrium whilst checking endometrial coagulation via transabdominal ultrasound guidance under general anesthesia. The devices used are the Microtaze AFM-712 (Alfresa Pharma Co., Ltd. Osaka) and Sounding Applicator CSA-40CBL-1006200C (Alfresa Pharma Co., Ltd. Osaka). Cauterization with the Microtaze is performed at an output of 70 W for 50 s per coagulation current cycle. Here, we report three cases in which abnormalities were found on endometrial tissue tests performed using total endometrial curettage when performing MEA.

Case reports

Case 1

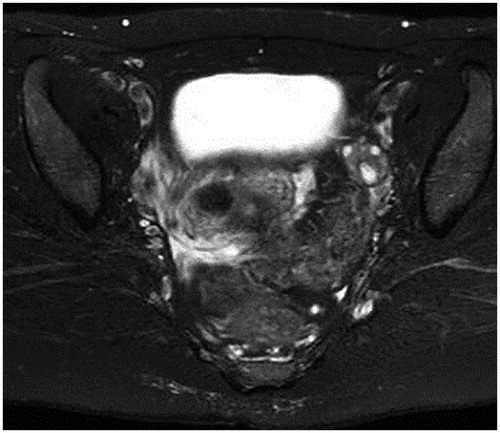

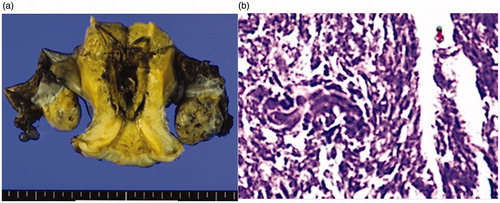

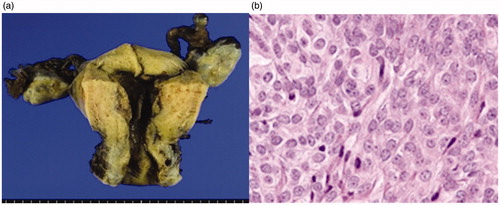

42 years old, 1 pregnancy, 1 birth. She was referred to our department for detailed examination and treatment having experienced hypermenorrhea accompanied by uterine myoma and anemia for 2 years. There were no special findings in the preoperative cervical and endometrial cytology results. A pelvic T2-weighted MR scan showed a low-intensity region with a clear boundary and a diameter of 20 mm protruding into the uterine cavity (), MEA was performed following a diagnosis of organic hypermenorrhea. The results from histopathological tests during MEA revealed low grade endometrial stromal sarcoma, and 6 weeks after the MEA, abdominal total hysterectomy and bilateral adnexectomy were performed (pT1a, Nx, M0). Histopathological diagnosis post-surgery showed an image of coagulation necrosis due to thermal denaturation of the endometrium and myometrium, but there remained some endometrial sarcoma (). The patient required no additional therapy and remains alive without recurrence for 4 years post-surgery.

Figure 1. Pelvic MRI: On T2-weighted MRI, a low-intensity region with a clear boundary and a diameter of 20 mm protruding into the uterine cavity is seen. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Figure 2. (a) Macroscopic findings of a specimen. Coagulation necrosis due to thermal denaturation of the endometrium and the myometrium is seen. (b) Histopathological image of the endometrium after MEA (HE staining X40). Coagulation necrosis due to thermal denaturation of the endometrium and the myometrium is seen, but with some remnant endometrial sarcoma. MEA, microwave endometrial ablation; HE, hematoxylin-eosin.

Case 2

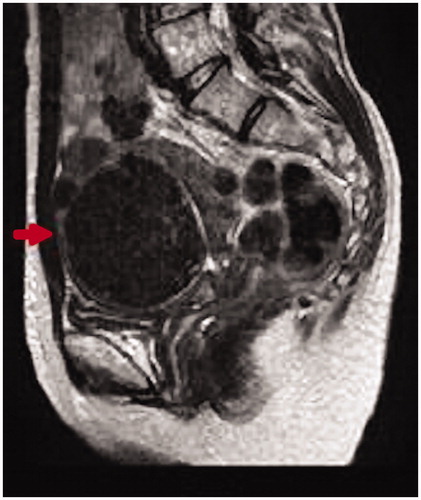

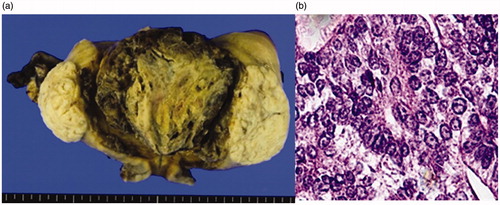

53 years old. No pregnancies, no births. The patient had been monitored for 5 years due to hypermenorrhea and uterine fibroids. A pelvic T2-weighted MR scan showed a well-defined low intensity region with a maximum diameter of 80 mm in the posterior uterine wall (). There were no significant findings in the cervical and endometrial cytology results at regular examinations. She consulted an emergency outpatient department following a large amount of vaginal bleeding. When this persisted, an emergency MEA was performed. The bleeding stopped immediately and the course following surgery was favorable. The histopathological test results from MEA showed endometrial adenocarcinoma (grade 2) and radical surgery for uterine cancer was performed 4 weeks after MEA (pT1b, pN1, M0). A histodiagnosis post-surgery was coagulation necrosis due to thermal denaturation of the endometrium and myometrium, but there remained some endometrioid adenocarcinoma ().

Figure 3. Pelvic MRI: On T2-weighted MRI, a low-intensity area with a maximum diameter of 80 mm and clear boundary is present on the anterior uterine wall. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Figure 4. (a) Macroscopic findings of a specimen. Coagulation necrosis due to thermal denaturation of the endometrium and the myometrium is seen. (b) Histopathological image of the endometrium after MEA (HE staining X40). Coagulation necrosis due to thermal denaturation of the endometrium and the myometrium is seen, but with some remnant endometrial adenocarcinoma. MEA: microwave endometrial ablation; HE: hematoxylin-eosin.

Post-operative chemotherapy was carried out as an additional therapy. Three years and 6 months have passed since the operation, and no recurrence has been observed during this period.

Case 3

42 years old, 2 pregnancies, 2 births. The patient came for a consultation at our department due to hypermenorrhea and repeated irregular vaginal bleeding for 4 months. There were no special findings in the preoperative cervical and endometrial cytology results. MEA was performed following a diagnosis of functional hypermenorrhea. Test results from histopathological testing during MEA indicated an atypical endometrial hyperplasia complex, and 3 months after MEA, a laparoscopic total hysterectomy was carried out. Post-operative histopathological diagnosis showed coagulation necrosis due to thermal denaturation of the endometrium and myometrium, and only non-atypical endometrial hyperplasia was detected (). The patient remains alive without recurrence 3 years post-surgery. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of International University of Health and Welfare (Approval number 20-B-399). The patients provided written informed consent for the publication of their data.

Figure 5. (a) Macroscopic findings of a specimen. Coagulation necrosis due to thermal denaturation of the endometrium and the myometrium is seen. (b) Histopathological image of the endometrium after MEA (HE staining X40). Coagulation necrosis due to thermal denaturation of the endometrium and the myometrium is seen, but only with signs of non-atypical endometrial hyperplasia. MEA: microwave endometrial ablation; HE: hematoxylin-eosin.

Discussion

The prevalence of hypermenorrhea among women of reproductive age is said to be 19–24% [Citation1, Citation2].. The prevalence tends to increase with age, accompanied by an increase in the need for managing hypermenorrhea in ways that align with a patient’s lifestyle. Recently, perhaps due to women playing a larger role in society, there has been an increase in women requesting minimally invasive treatment that requires fewer days of hospitalization.

MEA, as a minimally invasive treatment method for hypermenorrhea, was approved for insurance coverage in April 2012 and has gradually become more widely used in Japan. Our hospital introduced the treatment method in January 2016, and we have previously reported its efficacy as a treatment method which achieves definitive results in hypermenorrhea accompanied by anemia [Citation3].

MEA uses a protein coagulation device that utilizes dielectric heating of tissue that is generated by the irradiation of microwaves on tissue, which breaks down the endometrium, including the basal layer, to reduce the amount of menstrual bleeding or to induce amenorrhea. It has been noted that after MEA, collection of tissues from the endometrium may become difficult due to endometrial adhesions or septum formation which can delay the diagnosis of malignant endometrial tumors [Citation4, Citation5]. Hence at our facility, we carry out a cytodiagnosis of the endometrium or histodiagnosis of the endometrium as needed prior to MEA in order to rule out malignant diseases of the endometrium. In addition, a histological examination via total endometrial curettage is carried out during MEA. Abnormal findings were observed in three cases (4.1%) from endometrial tissue examinations carried out during MEA, even though endometrial cytodiagnosis prior to MEA had been negative. Fortunately, early treatment was possible for all cases and no signs of recurrence have been seen as yet.

Various cases have been seen in which endometrial cancer has disappeared because of MEA [Citation6, Citation7] and there is hope it could be a treatment for endometrial cancer. However, there is yet to be sufficient investigation into whether the treatment method works preventatively against the onset of endometrial cancer [Citation8]. In the cases at our hospital, a histopathological examination post-MEA showed remnants of malignant endometrial tissues. At present, we believe careful consideration should be given regarding the application of this treatment in cases at high risk of endometrial cancer, such as patients with endometrial hyperplasia or those taking tamoxifen. Depending on the disease, providing standard surgery as an additional therapy is considered appropriate for cases with abnormal test results from endometrial tissue testing found by chance during MEA. Moreover, as reported elsewhere [Citation6], MEA’s emergency hemostatic effect in cases of severe hemorrhage due to endometrial cancer, such as in case 2, shows much promise.

Ruling out endometrial malignant lesions using cytodiagnosis or histodiagnosis of the endometrium pre-surgery is a matter of course when performing MEA. However, the sensitivity of endometrial cytodiagnosis is reported to be 88%, with a specificity of 98.5%, and it has also been reported that performing just one endometrial cytodiagnosis produces a false negative in 11.2% of cases [Citation9]. Therefore, it is considered important to carry out endometrial histological examinations via a total endometrial curettage when performing MEA. Moreover, even in cases where no abnormalities are observed in endometrial examinations before or during MEA, long-term monitoring of subjective symptoms, such as irregular bleeding or abdominal pain, as well as ultrasonography should be performed to enable early discovery and treatment for malignant endometrial diseases.

Conclusion

We believe that when conducting MEA, even if malignant endometrial diseases are ruled out prior to surgery, it is important to carry out detailed examination bearing in mind potential malignant endometrial diseases and to continue to address the situation carefully, including during the post-surgery period.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Fernandez H. Update on the management of menometrorrhagia: new surgical approaches. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2011;27(sup1):1131–1136.

- Amso NN, Stabinsky SA, McFaul P, et al. Uterine thermal balloon therapy for the treatment of menorrhagia. BJOG: Int J O&G. 1998;105(5):517–523.

- Kakinuma T, Ushimaru S, Kagimoto M, et al. Microwave endometrial ablation at a frequency of 2.45 GHz is effective for the treatment of hypermenorrhea: a clinical investigation at our hospital. J Microwave Surg. 2019;37(3):1–5.

- AlHilli MM, Hopkins MR, Famuyide AO. Endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation: systematic review of medical literature. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(3):393–400.

- Ahonkallio SJ, Liakka AK, Martikainen HK, et al. Feasibility of endometrial assessment after thermal ablation. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;147(1):69–71.

- Nakamura K, Nakayama K, Ishikawa M, et al. Efficacy of microwave ablation for the treatment of endometrial carcinoma: a report of 3 cases. Oncol Lett. 2016;11(5):3025–3027.

- Sharp N, Ellard M, Hirschowitz L, et al. Successful microwave ablation of endometrial carcinoma. BJOG. 2002;109(12):1410–1412.

- Singh M, Hosni MM, Jones SE. Is endometrial ablation protective against endometrial cancer? A retrospective observational study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293(5):1033–1037.

- Fujiwara H, Takahashi Y, Takano M, et al. Evaluation of endometrial cytology: cytohistological correlations in 1,441 cancer patients. Oncology. 2015;88(2):86–94.,