Abstract

Objective

To compare the efficacy and safety of high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) and gonadotropin-releasing analogues (GnRH-a) as pretreatments for the hysteroscopic transcervical resection of myoma (TCRM) for type 2 submucosal fibroids greater than 4 centimeters in diameter.

Materials and methods

Seventy-nine patients were assigned into two groups according patient preference: 42 in HIFU and 37 in GnRHa. TCRM was performed after 3 months of pretreatment with HIFU or GnRHa.

Results

Following pretreatment with HIFU or GnRHa, uterine-fibroid symptom (UFS) scores and hemoglobin levels (HGB) showed improvement. The fibroid maximum diameter, size of fibroids, and volume of the uterus were decreased. Following HIFU pretreatment, one case reported complete vaginal fibroid expulsion, and four reported partial fibroid expulsion. No similar cases were found in the GnRHa group. Eighteen patients were lost to follow-up prior to TCRM. Among the 31 patients in HIFU, the fibroids were downgraded to type 0 in 10 cases and type 1 in 5 cases. Of the 30 patients in GnRHa, the treated fibroids were downgraded to type 1 in 9 cases. The mean operation time and intraoperative blood loss of the HIFU group were significantly lower than those in the GnRHa group. No significant differences were observed in the incidence of intraoperative complications and the one-time resection rate of fibroids between the two groups (p>.05).

Conclusions

HIFU seems to be superior to GnRHa as a pretreatment method prior to TCRM for type 2 submucosal fibroids greater than 4 centimeters in diameter

Introduction

The prevalence of uterine myomas or fibroids is generally reported as 20–25% among reproductive age women, although histological or ultrasonographical examinations showed an incidence as high as 70–80% in some populations [Citation1]. When the uterine fibroids grow into the uterine cavity, the fibroids often lead to increased menstrual volume, prolonged menstrual periods, and repeated miscarriages [Citation2]. Submucosal fibroids are typically classified into three subtypes according to the proportion of the myometrium involved. Type 0 is a pedunculated fibroid without intramural extension, type 1 extends less than 50% into the myometrium and type 2 extends at least 50% into the myometrium [Citation3]. Compared with type 0 and type 1, type 2 uterine submucosal fibroids are associated with a significantly higher miscarriage rate because the fibroids significantly affect embryo implantation particularly when the size larger than 4 cm in diameter [Citation4]. Currently, the gold standard for the treatment of submucosal fibroids is hysteroscopic transcervical resection of myoma (TCRM) [Citation3]. However, a series of complications may occur when TCRM was used to treat type 2 uterine fibroids larger than 4 cm in diameter. Therefore, some researchers used gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues (GnRH-a) to reduce the size of the fibroids prior to hysteroscopic myomectomy to minimize the risk of complications [Citation5,Citation6]. But the side effects of GnRH-a, included hot flushes, night sweats, and irritability have limited the utility of GnRHa before surgery [Citation7,Citation8]. Some researchers have suggested that uterine artery embolization (UAE) can be used as a pretreatment for larger type 2 submucosal fibroid; this procedure can be used to block the blood vessels supplying the fibroids and thus help to shrink the myomas [Citation9]. However, it is possible that pelvic pain might occur postoperatively to varying degrees and may even cause amenorrhea [Citation10]; thus, UAE may not be suitable for such cases.

High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) is a novel noninvasive treatment for uterine fibroids. The previous studies have shown that HIFU is safe and effective in the treatment of uterine fibroids [Citation11,Citation12]. This technique is based on the characteristics of ultrasound beams, which can be focused at a distance from the surface of transducer. The accumulated energy at the focus increases the temperature at the targeted tumor to 60–100 °C, thus resulting in the denaturation of proteins and the induction of necrosis [Citation13]. Qu. et al. performed a feasibility study of HIFU treatment for type 2 submucosal fibroids with the size larger than 4 cm in diameter prior to hysteroscopic myomectomy [Citation14]. The results showed that HIFU treatment prior to hysteroscopic myomectomy could reduce the volume of fibroids and decrease the risk of complications of hysteroscopic myomectomy; however, the number of cases was small.

As yet, there is no alternative universal method for the pretreatment of type 2 submucosal fibroids prior to hysteroscopic myomectomy. In the present study, we compared the treatment results of patients with type 2 submucosal fibroids with size larger than 4 cm in diameter between the patients treated with HIFU and the patients treated with GnRHa prior to hysteroscopic resection.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by our institutional review board (IRB). All procedures involving human participants were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee (Reference number: 2019ER(R)032).

Patients

We recruited patients with type2 submucosal fibroids (with a diameter greater than 4 cm) who were diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) between January 2019 and December 2019 in the Affiliated Hospital of Northern Sichuan Medical College.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with solitary symptomatic submucosal fibroid requiring treatment;(2) the size of the submucosal fibroids was greater than 4 cm in diameter;(3) patients were able to communicate with the nurse or physician during the procedure.

Exclusion criteria: (1)patients with contraindications to MRI, HIFU or TCRM;(2)patients with suspected to confirmed uterine malignancy;(3)patients with pelvic inflammatory diseases;(4)patients allergic to GnRHa

Patients underwent HIFU or GnRH-a according to their preference. Baseline characteristics before pretreatment included age, BMI, and the largest diameter of the fibroid, the score of uterine fibroid symptom (UFS), HGB, and the volume of the uterus were recorded. Type of the submucousal fibroids following pretreatment between the two groups was also recorded.

HIFU treatment

The protocol of HIFU treatment was described in a previously study [Citation15]. Briefly, HIFU treatment was performed under conscious sedation. The JC HIFU tumor therapeutic system (Chongqing Haifu Medical Technology, Co., Ltd., Chongqing, China) was used for HIFU treatment. Therapeutic ultrasound energy was generated by a transducer with a frequency of 1.0 MHz. A Mylab 70 ultrasound imaging device (Esaote, Genova, Italy) was used to provide real-time imaging to monitor the treatment. The patients were placed in a prone position on the HIFU table, with the anterior abdominal wall in contact with degassed water. A degassed water balloon was placed between the abdominal wall and the transducer to help compress or push the bowel away from the acoustic pathway. Focal point was selected, and power set between 300–400 watts. During the procedure, the power was adjusted based on patient feedback and gray scale changes. This process was repeated until there was an absence of blood supply under contrast-enhanced ultrasound. The patients' vital signs such as heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, oxygen saturation were monitored during the procedure. The following formula: V = (1/6) × π ×D1 × D2 × D3 was used to calculated the volume of the fibroids, the non-perfused volume, and the volume of the uterus [Citation16].

GnRH-a treatment

Patients received a subcutaneous injection of GnRH-a (3.75 mg leuprolide acetate microspheres) on the first day of menstruation. This administration was repeated in every 28 days for 3 months. All patients were followed up and the symptom improvement and adverse effects were recorded.

TCRM treatment

The procedure of hysteroscopic myomectomy was performed under intravenous anesthesia. An inner 3 mm 15˚ rigid hysteroscope and an 8.5 mm outer sheath (Olympus, Japan) were used. Isotonic sodium chloride solution was used as a distention media and a distention pressure of 80–100mmHg was maintained. Misoprostol (0.2 mg) was used to dilute the cervix the day before surgery. The procedure involved a bipolar electrosurgery system and an isotonic sodium chloride solution was used as a distending media. Oxytocin of 20 unit was used to promote uterine contraction between surgeries. If there was significant bleeding, we would use a Foley urinary catheter to tamponade the uterine cavity and prevent bleeding. Hysteroscopy was repeated 1 month after TCRM to evaluate the repair of uterine cavity.

Statistical analysis

The version 22.0 SPSS software was used for all statistical analyses. Measurement data were expressed as means ± standard deviation or as medians (with interquartile range). Count data were expressed as frequencies. Quantitative data that were normally distributed were compared using the student’s t-test while data that were not normally distributed were compared with the rank sum test. Count data were analyzed with the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact probability method. p < .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics before pretreatment

The mean age of the patients in HIFU group was 39.95 ± 6.79 years, the average BMI was 20.90 ± 1.88 kg/m2, and the mean maximum fibroid diameter was 54.90 ± 13.42 mm. The average age of the patients in the GnRHa group was 40.61 ± 6.35 years, with a mean BMI of 20.96 ± 1.91 kg/m2, and a mean maximum fibroid diameter of 56.58 ± 13.35 mm ().

Table 1. Baseline characteristics before pretreatment.

Comparison of treatment results between HIFU and GnRHa

Following HIFU treatment, a significant improvement in the symptoms was observed in these patients. Compared with the basic situation before HIFU, the UFS score was significantly lower and the HGB was significantly higher (p < .001). We also observed the patients had a significant reduction in the largest fibroid diameter, fibroid volume, and uterine volume after HIFU treatment (p < .05) ().

Table 2. Pretreatment comparisons.

In the GnRH-a group, we also observed the symptom improvement and the size reduction of the fibroids and the uterus (). We further compared the results between the two groups before and after pretreatment and found that the maximum fibroid diameter in the HIFU group had reduced by a mean of 14.26 ± 9.24 mm, while it was 7.49 ± 5.21 mm in the GnRHa group. The reduction of the maximum diameter of the fibroids was significantly larger in HIFU group than that seen in the GnRH-a group (p < .05). The mean elevation of HGB in the GnRH-a group was 21.76 ± 11.63 g/L and it was significantly higher than that observed in the HIFU group (10.57 ± 16.13) g/L. When compared between the two groups of patients, there were no significant differences with regards to UFS score and the reduction in either fibroid or uterine volume (p > .05) (). One patient in the HIFU group reported the complete expulsion of a fibroid 1 month after HIFU, with a maximum diameter of 3 cm. Four patients had a partial dropout 1–2 months after HIFU. A marked reduction in fibroid size and a significant improvement in symptoms were observed in 6 patients; consequently, these patients didn’t have hysteroscopic myomectomy. Finally, 31 cases in the HIFU group underwent hysteroscopic myomectomy. In the GnRH-a group, seven patients were treated by other methods due to unsatisfactory results or severe side effects. Of these, four patients underwent laparoscopic myomectomy, and three underwent total hysterectomy. Therefore, 30 patients underwent hysteroscopic myomectomy in the GnRH-a group.

Table 3. Variable differences for pre-HIFU and pre-TCRM.

Fibroid type changes

As shown in , the type 2 fibroids were converted into type 0 in 5 cases and type 1 in 10 cases after HIFU. Nine patients in the GnRH-a group had the type 2 fibroids converted into type 1; none of the patients had the type 2 fibroids converted into type 0. However, there was no significant difference in the rate of fibroid type changes between the two groups was observed.

Table 4. Types of submucous myomas following pretreatment.

TCRM comparison between patients with pretreatment of HIFU and GnRHa

In patients who entered the stage of hysteroscopic myoma resection, the 31 cases in the HIFU group had a mean age of 40.23 ± 6.22 years, a mean BMI of 21.05 ± 1.90 kg/m2, a mean UFS score of 12.35 ± 4.40 points, a mean HGB of 110.26 ± 17.60 g/L, and a mean maximum fibroid diameter of 43.29 ± 10.95 mm. The 30 patients in the GnRH-a group had a mean age of 40.03 ± 6.34 years, a mean BMI of 21.20 ± 1.84 kg/m2, a mean UFS score of 12.53 ± 4.78, a mean HGB of 105.13 ± 10.94 g/L, and a mean maximum fibroid diameter of 45.57 ± 12.32 mm ().

Table 5. General characteristics before TCRM.

The mean operation time in the HIFU group was 27.26 ± 9.98 min, the mean bleeding volume was 14.84 ± 7.13 ml, and the mean volume of the hysteroscopic fluid distention media was 664.52 ± 270.24 ml; these were all significantly lower than those in the GnRH-a group (p < .05). All the fibroids in the HIFU group were excised in one session of hysteroscopical surgery; the successful resection rate was 100%. In the GnRH-a group, three patients failed to remove the fibroids in one session of hysteroscopical myomectomy because a significant amount of bleeding during the procedure. The surgery was repeated 2–3 months later. The successful resection rate was 83.33%. In the HIFU group, one case suffered from suspected aquatic poisoning during surgery; the complication rate was 3.57% (1/31). In the GnRH-a group, there was one case of acute water poisoning during surgery and 2 cases with excessive bleeding (approximately 100 ml); the complication rate was 11.11% (2/30). There was no significant difference between the two groups with regards to the incidence of complications ().

Table 6. A comparison of parameters during the TCRM procedure.

Discussion

Hysteroscopic myomectomy is the standard procedure for the treatment of submucosal fibroids. However, previous studies indicated that the high complication rate may occur if the size of type 2 uterine fibroids larger than 4 cm in diameter. The reports have suggested that type 2 uterine fibroids need to minimized to less than 4 cm in diameter bofore TCRM to reduce operation difficulties, intraoperative bleeding, and the incidence of complications [Citation4,Citation5]. In this study, we either performed HIFU or gave GnRH-a for type 2 submucosal fibroids with a diameter greater than 4 cm for pretreatment, then performed hysteroscopy after three months.

Liao et al. previously reported two cases treated with HIFU before hysteroscopc surgery for submucosal fibroids. The results showed a shorter operating time, and less blood loss during hysteroscopic myomectomy [Citation17]. Our results showed that HIFU treatment could significant relieve symptoms associated with submucosal fibroids. The UFS scores improved, HGB increased, the maximum fibroid diameter and the volume of the fibroids reduced. Uterine fibroids are a kind of hormone-dependent tumors and GnRH-a can inhibit the growth of fibroids by inhibiting the secretion of hormones [Citation18]. The previous study have shown that GnRHa was more sensitive to the uterine fibroids with large size, with rich blood supply [Citation18]. In this study, we also noted a significant improvement in symptom relief, the scores of UFS, anemia, and a reduction in the maximum fibroid diameter in the GnRH-a group, along with a reduction in the volume of the fibroids and uterus. We further compared the treatment efficacy and found that the mean reduction in the maximum fibroid diameter in the HIFU group was significantly larger than that in the GnRH-a group. This phenomenon can be explained by that HIFU could ablate the fibroids precisely, thus leading to notable shrinkage of fibroids [Citation11,Citation19]. However, the main effect of GnRH-a on fibroids is the inhibition of hormone secretion, we should consider the fact that some fibroids may be not sensitive to estrogen. Thus, the average maximum reduction in fibroid diameter in the GnRH-a group was smaller than that in the HIFU group. The increase of HGB in the GnRH-a group was significantly higher than that in the HIFU group. It can be explained by that the GnRH-a inhibited the levels of FSH and LH, thus leading to a reduction in estrogen. On average, patients experience 2–3 months of ‘false menopause’ after giving such medication [Citation20], therefore reducing blood loss in vitro, and increasing self-stored blood volume. In contrast, HIFU did not affect the endocrine status of our patients; instead, symptoms were relieved by ablating fibroids. This led to a reduction in menstrual volume, rather than creating a menopausal state. Consequently, there was an increase in HGB in the HIFU group, although this increase was not as high as that observed in the GnRH-a group.

In our study, we observed that HIFU promoted the conversion of type 2 submucosal fibroids into type 0, type 1, and even self-expulsion. This phenomenon may be explained by that the uterus rejected the necrotic components by uterinecontraction, thus promoting fibroids to move into the uterine cavity. In a previous study, Wang et al. treated 76 patients with uterine submucosal fibroids with an average diameter of 5.7 ± 2.3 cm; 44 of these patients experienced the excretion of necrotic tissue after 2–4 menstrual cycles. During follow-up, 2 cases experienced a completely discharge of fibroids at 1 and 3 months after HIFU [Citation19]. In another study, Qu et al. reported two cases were converted into type 0, and three cases were converted into type 1 after HIFU [Citation14]. In the GnRH-a group, the type 2 submucosal fibroids were converted into type 1 in 9 patients after pretreatment. We found that the endometrial muscle layer was thinner, the uterine volume was reduced, and the uterine muscle was compressed after pretreatment with GnRH-a. It was also evident that tumors protruded into the uterine cavity, thus converting to type 0 or 1. Our results showed that both HIFU and GnRH-a can produce similar effects. We found that the number of reduction cases in the HIFU group was higher than that in the GnRH-a group, although there was no significant difference in the reduction rate when compared between the two groups, possibly because of the small sample size and short follow-up time.

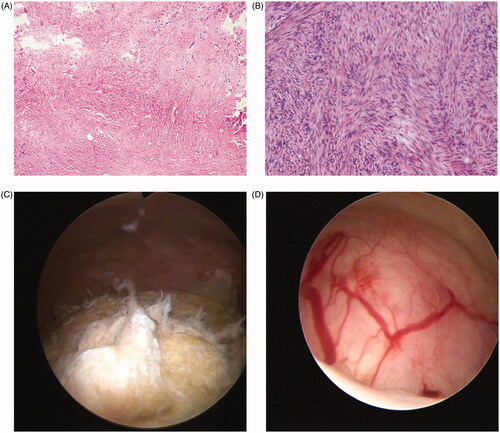

The previous study showed that the size of uterine fibroids decreased by 20–77% after administration of GnRHa for 3–6 months [Citation21]. Many studies have reported that the size of a myoma can be reduced by 35 − 65% over 3 cycles [Citation22–25]. So we performed hysteroscopic myoma resection 3 months after HIFU or GnRHa. In the present study, the mean time taken to perform TCRM, the mean bleeding volume, and the mean volume of hysteroscopic fluid distention media for the HIFU group were significantly lower than those of the GnRH-a group (p < .05). These can be explained by that the shrinkage of the fibroids after HIFU treatment was significantly higher and more type 2 submucosal fibroids were changed to type 0 and type 1, which made TCRM easier. Also, following HIFU treatment, fibroids were ablated and the blood supply was reduced; thus, the boundary between the fibroids and the myometrium was more distinct. This made the surgery easier and shortened the operating time. However, This was not the case in the GnRH-a group, thus showing that HIFU treatment can ablate fibroids and cause necrosis in an efficient manner (). Following GnRH-a treatment, patients exhibited low levels of estrogen. As a consequence, it was difficult for the cervix to dilate, and the endometrium became thinner. During hysteroscopy, we found that the surface of the fibroids was grayish/yellow after HIFU pretreatment, with no obvious blood supply. After GnRH-a treatment, the surface of the fibroids was pink and an obvious distribution of blood vessels was evident (). This would increase the difficulty associated with the electromyectomy of fibroids in the GnRHa group. However, there was no significant difference in the incidence of intraoperative complications, or the one-time resection rate of fibroids was observed between the two groups. This may be related to the small sample size and short follow-up time. In order to reduce the occurrence of intraoperative complications, and particularly, to reduce the absorption of hysteroscopic fluid distention media and thus decrease the risk of pulmonary edema, congestive heart failure, and electrolyte imbalances, it is important that hysteroscopy surgery should be completed within 60 min [Citation7,Citation26]. Therefore, pretreatment with HIFU can improve the safety and efficacy of hysteroscopic myomectomy.

Figure 1. (A) Postoperative histology for the HIFU group following TCRM suggesting uterine leiomyoma with coagulative necrosis. (B) Postoperative histology for the GnRH-a group following TCRM suggesting uterine leiomyoma. (C) Hysteroscopic analysis of the HIFU group; the surface of the fibroids was grayish/yellow with no obvious blood supply. (D) Hysteroscopic analysis of the GnRH-a group; the surface of the fibroids was pink and there was an obvious distribution of blood vessels.

Conclusion

Our results showed that both HIFU and GnRH-a can be effectively used as a pretreatment for type 2 submucosal fibroids when the fibroids are greater than 4 cm in diameter. HIFU caused a greater reduction in the size of the fibroids, but GnRH-a treatment had a better effect on anemia. Based on the results of this study, we concluded that HIFU can cause coagulative necrosis of the fibroids, thus reduce bleeding, decrease the time required for TCRM surgery, and improve the safety profile of such surgery. It seems that HIFU is superior to GnRHa as a pretreatment of type 2 submucosal fibroids greater than 4 centimeters in diameter.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Day Baird D, Dunson DB, Hill MC, et al. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(1):100–107.

- Chabbert-Buffet N, Esber N, Bouchard P. Fibroid growth and medical options for treatment. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(3):630–639.

- Munro MG, Critchley HO, Broder MS, FIGO Working Group on Menstrual Disorders, et al. FIGO classification system (PALM-COEIN) for causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in nongravid women of reproductive age. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;113(1):3–13.

- Laganà AS, Alonso Pacheco L, Tinelli A, et al. Management of asymptomatic submucous myomas in women of reproductive age: a consensus statement from the Global Congress on Hysteroscopy Scientific Committee. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26(3):381–383.

- Lasmar RB, Barrozo PRM, Dias R, et al. Submucous myomas: a new presurgical classification to evaluate the viability of hysteroscopic surgical treatment – preliminary report. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(4):308–311.

- Zhang Y, Sun L, Guo Y, et al. The impact of preoperative gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist treatment on women with uterine fibroids: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2014;69(2):100–108.

- Lee GY, Han JI, Heo HJ. Severe hypocalcemia caused by absorption of sorbitol-mannitol solution during hysteroscopy. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24(3):532–534.

- Lethaby A, Puscasiu L, Vollenhoven B. Preoperative medical therapy before surgery for uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11:D547.

- Ukybassova T, Terzic M, Dotlic J, et al. Evaluation of uterine artery embolization on myoma shrinkage: results from a large cohort analysis. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2019;8(4):165–171.

- Vercellini P, Carmignani L, Rubino T, et al. Surgery for deep endometriosis: a pathogenesis-oriented approach. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2009;68(2):88–103.

- Lee J, Hong G, Lee K, et al. Safety and efficacy of ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound treatment for uterine fibroids and adenomyosis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2019;45(12):3214–3221.

- Wang Y, Liu X, Wang W, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of US-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation for symptomatic submucosal fibroids: a retrospective comparison with uterus–sparing surgery. Acad Radiol. 2020;S1076-6332(20)30286–5.

- Wu G, Li R, He M, et al. A comparison of the pregnancy outcomes between ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation and laparoscopic myomectomy for uterine fibroids: a comparative study. Int J Hyperthermia. 2020;37(1):617–623.

- Qu D, Chen Y, Yang M, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound for treatment of Type 2 submucous myomas more than 4 centimeters in diameter prior to hysteroscopic myomectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(5):1076–1080.

- Chen J, Chen W, Zhang L, et al. Safety of ultrasound-guided ultrasound ablation for uterine fibroids and adenomyosis: a review of 9988 cases. Ultrason Sonochem. 2015;27:671–676.

- Chen Y, Jiang J, Zeng Y, et al. Effects of a microbubble ultrasound contrast agent on high-intensity focused ultrasound for uterine fibroids: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Hyperthermia. 2018;34(8):1311–1315.

- Liao W, Ying T, Shen H, et al. Combined treatment for big submucosal myoma with High Intensity Focused Ultrasound and hysteroscopic resection. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;58(6):888–890.

- Grigoriadis C, Papconstantinou E, Mellou A, et al. Clinicopathological changes of uterine leiomyomas after GnRH agonist therapy. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39(2):191–194.

- Wang W, Wang Y, Wang T, et al. Safety and efficacy of US-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound for treatment of submucosal fibroids. Eur Radiol. 2012;22(11):2553–2558.

- Corrêa TD, Caetano IM, Saraiva PHT, et al. Use of GnRH analogues in the reduction of submucous fibroid for surgical hysteroscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia/RBGO Gynecol Obstet. 2020,42(10):649–658.

- Wang PH, Lee WL, Chao HT, et al. Relationship between hormone receptor concentration and tumor shrinkage in uterine myoma after treatment with a GnRHa. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei). 1999;62(5):294–299.

- Chia CC, Huang SC, Chen SS, et al. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the change in uterine fibroids induced by treatment with a GnRH analog. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;45(2):124–128.

- Di Lieto A, De Falco M, Pollio F, et al. Clinical response, vascular change, and angiogenesis in gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue-treated women with uterine myomas. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2005; 12(2):123–128.

- Di Lieto A, De Falco M, Mansueto G, et al. Preoperative administration of GnRH -a plus tibolone to premenopausal women with uterine fibroids:evaluation of the clinical response, the immunohistochemical expression of PDGF.bFGF and VEGF and the vascular pattern. Steroids. 2005;70(2):95–102.

- Palomba S, Orio F, Jr, Russo T, et al. Long-term effectiveness and safety of GnRH agonist plus raloxifene administration in women with uterine leiomyomas. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(6):1308–1314.

- Fitzgerald JJ, Davitt JM, Frank SR, et al. Critically high carboxyhemoglobin level following extensive hysteroscopic myomectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(2):548–550.