Abstract

Objective: To compare early and late hysteroscopic resection after high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) for retained placenta accreta.

Methods: This retrospective study included 63 women with retained placenta accreta who were treated with HIFU combined with hysteroscopic resection. They were divided into an early group (n = 40) and a late group (n = 23), depending on the time between the HIFU and the hysteroscopic resection. The number of sessions of hysteroscopy needed, adverse events, menstrual recovery, and reproductive outcomes were compared.

Results: The mean largest diameter of the retained placenta accreta was 67.6 ± 14.0 mm and 71.6 ± 23.6 mm in each group (p = .47), respectively. In the early group, the first hysteroscopic procedure was done at a mean interval of 2.7 ± 1.4 days after HIFU ablation, while in the late group, the interval was 34.7 ± 15.0 days (p < .001). The rate of complete resection of placenta residue after one hysteroscopic procedure in the late group was 73.9% (17/23). This was significantly higher than in the early group, where the rate was 45% (p = .03). During the follow-up, there was no difference in menstrual recovery and pregnancy outcomes between the groups.

Conclusion: This study was the first to compare the effects and safety of early and late hysteroscopic resection after HIFU for retained placenta accreta. Late hysteroscopic resection seems to increase the rate of complete resection of retained placenta accreta after one hysteroscopic procedure.

Introduction

Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) is a life-threatening condition defined as the abnormal attachment of a part of or the entire chorionic plate to the myometrium. PAS is classified into three categories depending on the depth of the villous invasion into the myometrium: placenta accreta, placenta increta, and placenta percreta. The epidemiology of PAS has changed from a rare, serious, pathological condition to an increasingly common major obstetric complication because of the rapid increase in cesarean delivery (CD) rates [Citation1].

Currently, there is no consensus regarding optimal management of PAS. Leaving the placenta in situ and performing a planned hysterectomy at delivery has been the principal management strategy to prevent excessive bleeding [Citation2]. However, planned hysterectomy may be unacceptable to women desiring uterine and fertility preservation, so conservative management for uterine preservation has been used increasingly [Citation3]. Several additional procedures have been proposed to diminish blood loss, hasten placental reabsorption, or both. These include methotrexate administration, uterine devascularization with uterine artery balloon placement, embolization or ligation, and high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) [Citation4]. However, conservative management increases the risk of persistent bleeding, sepsis, and delayed hysterectomy. Operative hysteroscopy of retained placenta accreta can be used to remove the retained placenta accreta from the uterine cavity for conservative treatment.

Investigators have used hysteroscopic resection to remove placental remnants for expectantly managed patients. However, a previous study has shown that one half of the women required more than one procedure, and one-third required more than two procedures [Citation5]. Ye et al. used high-intensity, focused ultrasonography (HIFU) in conjunction with hysteroscopic resection of retained placenta accreta. All patients received hysteroscopic operations with a median of 2 days after HIFU treatment. Thirty-six percent of patients underwent a second session of hysteroscopic operations [Citation6]. Bai treated 12 patients with HIFU, the residual placental involution, at an average period of 36.9 days [Citation7]. It is not yet clear when the non-implanted part of retained placenta accreta should be removed from the uterine cavity after HIFU treatment. After the HIFU ablation, parts of the residual placenta might have been discharged or reabsorbed. It is reasonable to expect that late hysteroscopic resection after HIFU is more likely to facilitate complete removal of the residual placenta in one session of hysteroscopic operation when the diameter of the residual tissue is large.

Thus, the current study’s objective was to compare early and late hysteroscopic resection after HIFU for retained placenta accreta in terms of the number of sessions of hysteroscopy needed, estimated blood loss, adverse events, recovery of postoperative menstrual cycle, and reproductive outcomes.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

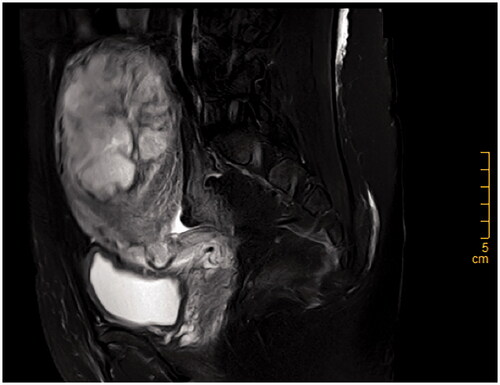

We performed a retrospective analysis of patients with retained placenta accreta who were treated with hysteroscopic resection after HIFU in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University between January 2015 and December 2019. The medical records of these patients were reviewed retrospectively. The diagnosis of retained placenta accreta was based on the medical history of the patients, pelvic examination, ultrasonographic findings and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (). Patients were included if they met the following three inclusion criteria: (1) the largest diameter of the retained placenta accreta was ≥ 4 cm without penetration of the uterine serosa, (2) there were stable vital signs without active vaginal bleeding or infection, and (3) follow-up information available. The retrospective study was approved by the hospital’s ethics committee and institutional review board. Clinical and demographic data were obtained from medical records.

HIFU ablation

All patients underwent pretreatment with HIFU to avoid hemorrhaging during the hysteroscopic operation that followed. The HIFU procedure was performed as described in our previous publication [Citation6]. In brief, the patient was positioned prone on the HIFU system (JC-200 focused ultrasound tumor therapeutic system, Chongqing Haifu Medical Technology Co., Ltd., Chongqing, China) and she received conscious sedation by fentanyl and midazolam hydrochloride (fentanyl at 1 μg/kg, midazolam hydrochloride at 0.03 mg/kg, repeating administration of each at 30-min intervals if needed). The HIFU treatment system produced ultrasound waves to penetrate the abdominal wall and focus on the placenta tissue. When the temperature increased, the targeted tissue experienced coagulative necrosis. During the procedure, an ultrasound imaging probe was used to monitor the tissue’s response to HIFU. The treatment was terminated when a gray-scale change occurred in the target tissue or when the signs of blood flow from placental tissue disappeared on the real-time ultrasound.

Hysteroscopic resection

Hysteroscopic resection was performed after HIFU ablation. Patients were categorized according to the intervals between hysteroscopic resection and HIFU treatment. When the interval was less than 7 days, the patients were categorized into the early group. When the interval was more than two weeks, the women were included in the late group. No patients received hysteroscopic procedures between 7 and 14 days after HIFU ablation in our hospital. The aim of the hysteroscopic resection was to remove the non-implanted part of the retained placenta in the uterine cavity, leaving the deeply implanted part of the placenta in situ. In the early group, the patients were discharged from the hospital 2 or 3 days after the hysteroscopic operation. In the late group, the patients were discharged 2–3 days after HIFU treatment, and they returned to the hospital two to eight weeks later to receive the hysteroscopic operation. In both groups, a second section of the hysteroscopic procedure was performed 4–8 weeks after the first hysteroscopic procedure if needed. The procedure of hysteroscopic resection was performed as described in our previous publication [Citation6].

Follow-up

Operative complications, such as uterine perforation, cervical injury, bleeding, and air embolism, were recorded. One to three days after surgery, abdominal ultrasonography was performed to confirm complete resection. Patients were contacted by telephone to assess improvement of symptoms and recovery of menstrual cycle. If a patient had hypomenorrhea and desired future fertility, they were advised to undergo hysteroscopy. The follow-up observation period ended with the last inpatient or outpatient contact after surgery.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using the statistical software SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and a p value < .05 was considered significant. Qualitative data were described by frequencies and percentages. The normally distributed continuous data were presented as mean ± standard deviation, and the not-normally distributed continuous data were presented as the median and inter-quartile range. Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test and Student’s t test were used as appropriate.

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients

We identified 63 eligible patients treated in our hospital. Forty patients underwent hysteroscopic resection less than a week after HIFU treatment (the early group), and 23 received hysteroscopic resection more than 2 weeks after HIFU ablation (the late group). Demographic data are shown in . The median age at diagnosis was 31.5 ± 5.5 years in the early group and 29.7 ± 3.5 years in the late group (p = .11). Among the 63 patients, 53 (84.1%) had previous curettage, 13 (20.6%) had previous cesarean sections, and 7 (11.1%) had previous intrauterine adhesions. In addition, one patient in the early group had undergone a hysteroscopic resection of submucous fibroid, and another woman had received a laparoscopic myomectomy. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in age, gravidity, parity, previous cesarean section rate, previous curettage rate, or previous intrauterine adhesions rate. Of patients with retained placenta accreta, the delivery mode of the preceding pregnancy was not different between the groups (p = .79).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the patients with retained placenta accreta.

Thirty-seven women in the early group and 22 women in the late group complained of vaginal bleeding, while only 3 patients in the early group and 1 patient in the late group had retained placenta accreta with marked vascularity as the main complaint. The mean largest diameter of the retained placenta accreta was 67.6 ± 14.0 mm in the early group and 71.6 ± 23.6 mm in the late group (p = .47). In the early group, the HCG of nine patients was negative, and the HCG of the remaining 31 patients was positive. In the late group, 4 patients had negative HCG and 19 had positive HCG (p = .63). The mean interval between the end of the pregnancy and HIFU treatment was 36.8 ± 22.8 days in the early group and 30.5 ± 19.3 days in the late group (p = .27). There was no difference in interval days of pregnancy-treatment, the largest diameter of the retained placenta accreta, and the positive rate of HCG between the two groups.

The results of HIFU ablation

All 63 patients successfully completed HIFU treatment (), and the blood perfusion of the retained placenta accreta was reduced for all of them. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in the median sonication time (p = .84). During HIFU treatment, the main complaints were lower abdominal pain, sacrococcygeal pain, and/or a ‘hot’ skin sensation. No serious complications occurred during these procedures.

Table 2. Comparison of HIFU treatment results between early and late groups.

The results of hysteroscopic resection

In the early group, the first hysteroscopic procedure was done at a mean interval of 2.7 ± 1.4 days after HIFU ablation, while in the late group, the interval was 34.7 ± 15.0 days (p < .001) (). The largest diameter of the retained placenta accreta before the hysteroscopic procedure in the late group was significantly smaller than in the early group (p < .001). The mean uterine cavity depth in the late group (10.1 ± 1.7 cm) was significantly less than that in the early group (11.0 ± 1.5 cm) (p = .03). In the early group, 18 patients (45%) achieved complete resection of retained placenta accreta after the first procedure, and 22 patients (55%) did so after the second procedure, without any serious adverse events. Compared with the early group, the rate of complete removal of the retained placenta accreta after one hysteroscopic procedure was significantly higher in the late group (73.9%) (p = .03). The estimated blood loss in most patients in the early group (30/40) was less than 100 ml. The estimated blood loss of the remaining 10 patients was more than 100 ml, and two patients lost 400 and 500 ml. In the late group, the estimated blood loss of most patients (21/23) was less than 100 ml, and only two patients lost 100 ml. There was no difference between the groups regarding the estimated blood loss (p = .11). Intraoperative complications (including uterine perforation, cervical injury, and air embolism) were not reported in either group.

Table 3. Comparison of hysteroscopic operation results between early and late groups.

Complications

No woman underwent hysterectomy in either group. In the late group, a patient complained of abdominal pain, a fever with a temperature of 38.0 °C, increased WBC count (27.8 × 109/L), and increased neutrophil count (90.1%) on the 18th day after HIFU treatment. The vaginal secretion culture of the patient suggested Escherichia coli infection. The patient was treated with intravenous moxifloxacin (0.4 g, qd). After 1 day, her temperature became normal. After 2 days, WBC count and neutrophil count became normal, and the patient recovered after the third day of treatment. Another woman in the late group suffered major bleeding on the 29th day after HIFU treatment. Her hemoglobin level declined from 92 g/dL before the HIFU treatment to 82 g/dL. After intravenous administration of 20 units of oxytocin, the bleeding decreased. The patient received the hysteroscopic procedure on the 30th days after HIFU treatment. In the early group, there were no complications such as infection or major bleeding during the follow-up.

Follow-up result

During the follow-up, 72.5% of the patients in the early group had normal menstrual bleeding, while 82.6% of the patients in the late group recovered normal menstrual cycles (). In the early group, 11 patients complained of hypomenorrhea, and 7 of them received hysteroscopy and were diagnosed with intrauterine adhesions (IUA). Three of these seven patients were diagnosed with severe adhesions and the other four had moderate adhesion according to the AFS score [Citation8]. In the late group, four patients complained of hypomenorrhea, and two of them received hysteroscopy. One of them was diagnosed with severe adhesion and the other with mild adhesion. In the early group, 11 patients desired future pregnancy and 5 patients became pregnant, resulting in 3 live births, 1 miscarriage, and 1 abortion. In the late group, 8 patients desired future pregnancy and 6 patients became pregnant, resulting in 3 live births, 1 miscarriage, 1 abortion, and 1 ectopic pregnancy. There was no difference in menstrual recovery and pregnancy outcome between the two groups (p = .36 and p = .82, respectively).

Table 4. Comparison of follow-up results between early and late groups.

Discussion

Retained placenta accreta is a challenging obstetric problem because it represents a major cause of secondary postpartum hemorrhage, and it is associated with substantial maternal morbidity. Although conservative treatment should always be the rule in young or reproductive-age women, management of retained placenta accreta is still controversial, and no treatment recommendations have been established to date [Citation2,Citation9,Citation10]. Conservative treatments are associated with increased risks of coagulopathy, severe hemorrhage, infection, sepsis, blood transfusion, and even hysterectomy [Citation11]. A systematic review indicated that the rate of secondary hysterectomy in patients receiving expectant management was 19%, while 18% of patients underwent uterine artery embolization. Uterus-preserving surgery was performed in 31% of cases [Citation12]. Until now, expectant management, medical evacuation, or other additional procedures have been options without clearly defined applications [Citation13]. Some investigators have proposed the surgical removal of retained placenta accreta in the uterine cavity to reduce the risk of postpartum hemorrhage and infection, but the timing of surgical removal has not been clearly defined.

HIFU is a noninvasive treatment that using thermal ablation. Many studies have shown that HIFU is safe and effective in the management of benign uterine diseases [Citation14–16]. Since small blood vessels could be destroyed by HIFU, HIFU may decrease the risk of hemorrhage. Recently, this noninvasive technique has also been used in the treatment of placenta accreta [Citation7]. In 2017, we reported 25 patients with placenta accreta who underwent HIFU followed by hysteroscopic resection in our hospital. The median volume of intraoperative blood loss was 20 ml, which indicating that HIFU could reduce the chances of hemorrhage related to placenta accrete [Citation6]. In the present study, all patients successfully completed HIFU treatment. After HIFU ablation, an ultrasound showed that blood perfusion was reduced in all the retained placenta accreta. During treatment, no severe adverse effects occurred. Bai treated 12 patients with HIFU [Citation7], and the residual placental volumes decreased after HIFU treatment. Eleven patients who received the procedure discharged placenta-like tissues during their stays in the hospital. Only one patient received an operation using ovum forceps to grasp and pull the placental tissue. Follow-up results showed that the patients receiving HIFU treatment had an average period of residual placental involution of 36.9 days. After HIFU ablation, parts of the residual placenta might have been discharged or reabsorbed.

In this study, the mean largest diameter of the retained placenta accreta was more than 70 mm before HIFU ablation in the late group. After a mean period of 34.7 days after HIFU treatment, the largest diameter of the retained placenta accreta was still large. Although it was significantly reduced, it was still not fully absorbed or discharged. We thought it is necessary to remove the retained placenta accreta in the uterine cavity after HIFU, because it might take a long time for discharge and absorption, and this would increase the risk of infection and bleeding.

When surgical removal is required, hysteroscopic resection seems to be better than blind dilatation and curettage [Citation17]. Legendre et al. reported the results of hysteroscopic removal of tissue after conservative management of retained placenta accreta [Citation5]. Eleven patients achieved complete removal, but one patient underwent a secondary hysterectomy because of persistent bleeding and anemia after the first incomplete hysteroscopic resection. Only five patients underwent a complete removal of the uterus after one procedure, and four patients needed three procedures. In our previous study, patients received hysteroscopic operations with a median of 2 days after HIFU treatment. However, nine patients (36%) underwent a second session of hysteroscopic operations [Citation6]. To the best of our knowledge, no study has been performed to compare early with late hysteroscopic resection after HIFU treatment in the management of retained placenta accreta. In this study, the mean largest diameters of the retained placenta accreta in both groups were more than 50 mm. In the early group, 55% of the patients did not achieve complete resection of retained placenta accreta after the first procedure. In the late group, the rate of complete removal of the retained placenta accreta after one hysteroscopic procedure (73.9%) was significantly higher than for the early group. This may be because parts of the residual placenta were discharged or reabsorbed after HIFU ablation. The estimated blood loss in both groups was not different. No woman in either group needed a second hysterectomy.

During the follow-up, there was no difference in menstrual recovery and pregnancy outcome between the two groups. However, there were a small number of patients desired future pregnancy in both groups, and long-term follow-up is needed to determine whether there was a difference in reproductive outcomes between those two groups.

In addition, we should pay attention to the risk of infection and delayed hemorrhage during the long interval between HIFU and a hysteroscopic procedure. In this study, one patient in the late group suffered intrauterine infection and another suffered major bleeding during that interval. IUA is another important issue for patients desiring to preserve their fertility. We should pay attention to the problem of IUA after conservative management of placenta accreta. In our study, none of the patients had amenorrhea. In total, 23.8% of patients reported hypomenorrhea. However, for all the subjects, the rate of severe IUA diagnosed according to the AFS score was 6.3%, which is lower than in other research [Citation5,Citation10]. In this study, however, not all patients underwent standard second-look hysteroscopy. A prospective randomized trial including standard second-look hysteroscopy would provide more precise information about the rate of IUA after HIFU and hysteroscopic resection.

Conclusion

Based on our results, it seems that HIFU treatment followed by hysteroscopic resection is safe and effective in treating patients with retained placenta accreta. The rate of complete resection of retained placenta accreta after one hysteroscopic procedure was significantly higher after a longer interval between HIFU and the hysteroscopic procedure.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee and institutional review board of the Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (No.20003). The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author contributions

J.J.: data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, drafting the article and final approval of the version to be published. S.H.: participation in the procedure of hysteroscopic resection and data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, final approval of the version to be published. M.X.: responsible for the initial concept, data acquisition, and final review of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Wu S, Kocherginsky M, Hibbard JU. Abnormal placentation: twenty-year analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):1458–1461.

- Jauniaux E, Hussein AM, Fox KA, et al. New evidence-based diagnostic and management strategies for placenta accreta spectrum disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;61:75–88.

- Sentilhes L, Kayem G, Silver RM. Conservative management of placenta accreta spectrum. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;61(4):783–794.

- Society of Gynecologic Oncology; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine; Cahill AG, et al. Placenta accreta spectrum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(6):B2–B16.

- Legendre G, Zoulovits FJ, Kinn J, et al. Conservative management of placenta accreta: hysteroscopic resection of retained tissues. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(5):910–913.

- Ye M, Yin Z, Xue M, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound combined with hysteroscopic resection for the treatment of placenta accreta. BJOG. 2017;124 Suppl 3:71–77.

- Bai Y, Luo X, Li Q, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound treatment of placenta accreta after vaginal delivery: a preliminary study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47(4):492–498.

- The American Fertility Society classifications of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, mullerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril. 1988;49(6):944–955.

- Eller AG, Porter TF, Soisson P, et al. Optimal management strategies for placenta accreta. BJOG. 2009;116(5):648–654.

- Sentilhes L, Kayem G, Ambroselli C, et al. Fertility and pregnancy outcomes following conservative treatment for placenta accreta. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(11):2803–2810.

- Silver RM, Branch DW. Placenta accreta spectrum. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(16):1529–1536.

- Steins Bisschop CN, Schaap TP, Vogelvang TE, et al. Invasive placentation and uterus preserving treatment modalities: a systematic review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284(2):491–502.

- Takeda A, Koike W. Conservative endovascular management of retained placenta accreta with marked vascularity after abortion or delivery. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;296(6):1189–1198.

- Zhang L, Zhang W, Orsi F, et al. Ultrasound-guided high intensity focused ultrasound for the treatment of gynaecological diseases: a review of safety and efficacy. Int J Hyperthermia. 2015;31(3):280–284.

- Haiyan S, Lin W, Shuhua H, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) combined with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs (GnRHa) and levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) for adenomyosis: a case series with long-term follow up. Int J Hyperthermia. 2019;36(1):1179–1185.

- Huang L, Du Y, Zhao C. High-intensity focused ultrasound combined with dilatation and curettage for Cesarean scar pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;43(1):98–101.

- Golan A, Dishi M, Shalev A, et al. Operative hysteroscopy to remove retained products of conception: novel treatment of an old problem. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(1):100–103.