Abstract

Objective

To explore the feasibility of high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) ablation for treating metastatic pelvic tumors and recurrent ovary cancer.

Materials and methods

Eight patients with metastatic pelvic tumors or recurrent ovary cancer were enrolled in this study. Among them, 5 patients had ovarian cancer, 1 had cervical cancer, 1 had endometrial cancer, and 1 had rectal cancer. Six of them received abdominal surgical operation for their primary cancer, no one received radiotherapy. HIFU treatment was performed under conscious sedation. Vital signs were monitored during the procedure, and adverse effects were recorded. Postoperative follow-up was performed to observe pain relief and the improvement of the patient’s quality of life.

Results

The median age of the patients was 54 (range: 33–76) years, with a total of 12 lesions. The average volume of the lesions was 238.0 cm3. Six patients completed 12 months follow-up. Postoperative pain relief rate was 60% (3/5), and the quality of life improved in the short term. The main adverse effect of HIFU was pain in the treated area, with the pain score lower than 4, and all of which was self-relieved within 1 day after HIFU treatment. No serious complications such as skin burn, intestinal perforation, and nerve injury occurred.

Conclusion

HIFU is feasible for the treatment of metastatic pelvic tumors or recurrent ovary cancer without serious complications. Therefore, HIFU seems a promising treatment for recurrent ovary cancer, metastatic pelvic tumors from cervical cancer, endometrial cancer, and rectal cancer.

Introduction

Common pelvic malignant tumors include ovarian cancer, cervical cancer, endometrial cancer and rectal cancer. Among these malignant tumors, some are easy to recur after surgical operation. Several studies showed that the postoperative recurrence rate of early ovarian cancer is 25%, while the recurrence rate for advanced ovarian cancer can be as high as 80% [Citation1–3]. The recurrence rate of cervical cancer after surgery and radiotherapy is over 30%, and the 1-year survival rate after recurrence is only 10–15% [Citation4]. The postoperative recurrence rate of rectal cancer exceeds 40%, and the recurrence rate of patients with stage T3-4N1-2M0 can reach 45–65% [Citation5]. The treatment methods for metastatic pelvic tumors include surgical treatment, regional or systemic chemotherapy, radiotherapy, etc., but all have their limitations. Surgical treatment for metastatic pelvic tumors is very traumatic, with low radical resection rate. And regional or systemic chemotherapy has significant side effects, and can easily lead to drug resistance. In addition, radiotherapy also has huge side effects, and poor patient tolerance, which limits its application [Citation6–10]. Therefore, innovative treatment modalities may improve the treatment results.

Recently, high intensity focused ultrasound ablation (HIFU) has become a new modality for the treatment of various solid benign and malignant tumors [Citation11,Citation12]. The principle of HIFU treatment is to focus the ultrasound beams generated by a transducer outside the body on the tumor targets in the body, the mechanical effect of ultrasound is converted into thermal and cavitation effects, so that the temperature of the tumor tissue at the focal point rises to above 60° instantly and coagulative necrosis occurs without damaging the surrounding structures. After HIFU treatment, the lesion is absorbed by the surrounding tissues and gradually shrinks to relieve the symptoms. This also helps prolong patients’ survival time, as well as improve their quality of life. Many studies have shown its safety and effectiveness [Citation11–14]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no relevant report for HIFU treatment of metastatic pelvic tumors. Therefore, this study intends to investigate the feasibility of HIFU in the treatment of metastatic pelvic tumors.

Materials and method

This study was approved by the ethics committee of our hospital. Before HIFU treatment, the details of the treatment were discussed with every patient, and then an informed consent form was signed.

Patients

From January 2019 to October 2020, 8 patients with recurrent ovary cancer or metastatic pelvic tumors who received ultrasound-guided HIFU treatment in Suining Municipal Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine were enrolled in this study. Among them, 5 patients had ovarian cancer, 1 patient had cervical cancer, 1 patient had endometrial cancer, and 1 patient had rectal cancer. All patients had standard surgery for primary tumors. Both the patient with endometrial cancer and the patient with cervical cancer had hysterectomy, but refused to have radiotherapy. All of them were not suitable for re-surgical resection, or the patients refused to do so. Before HIFU treatment, oncologists and gynecologists evaluated these patients according to the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria: (1) all cases were diagnosed by imaging and confirmed by needle biopsy, meeting the diagnostic criteria for advanced pelvic and abdominal cavity metastases; (2)the tumor cannot be surgically removed or the patient is unwilling to undergo operation; (3) the patient and family members have a strong desire for treatment, they understand the treatment process and possible risks of HIFU, and agree to receive HIFU treatment; (4)) the patient is in line with the range of lesions that can be treated by HIFU technology and has a safe acoustic pathway.

Exclusion criteria: (1) patients with uncontrollable hypertension, hyperglycemia, history of cerebrovascular diseases, history of myocardial infarction, severe arrhythmia, heart failure, renal failure and liver function failure; (2) patients with significant abdominal wall scar in the acoustic pathway; (3) patients received radiotherapy with dosage more than 45 Gy; (4) patients with acute pelvic inflammatory disease; (6) the tumor couldn’t be visualized by the monitoring system.

Preoperative preparation

All patients underwent specific bowel preparation and skin preparation before HIFU treatment. Intestinal preparation included eating semi-liquid food or liquid food 2–3 days, fasting for 12 h before HIFU, and cleaning the enema on the morning of treatment. In skin preparation, shaved the hair between the anterior belly button and the upper edge of the pubic symphysis, and then degreased and degassed the skin with degassed water. Before HIFU treatment, a urinary catheter was inserted into the bladder, and the bladder volume was adjusted by infusing saline during the treatment to obtain a safe acoustic pathway.

HIFU ablation

HIFU ablation was performed using Model-JC focused ultrasound tumor therapeutic system and Model-JC200 focused ultrasound tumor therapeutic system made by Chongqing Haifu Medical Technology Co., Ltd. in China. The treatment system includes a focused ultrasound transducer, and a B model ultrasound diagnostic probe is installed in the center of the transducer to monitor the ablation process in real time.

The patient was positioned prone on the HIFU treatment table with the abdominal wall in contact with degassed water. Treatment was performed under intravenous sedation and analgesia. The purpose of analgesia and sedation was to reduce pain or discomfort during treatment, while ensuring doctors could communicate with patients accurately during treatment, so as to reduce the risk of surgery. During treatment, vital signs such as breathing, oxygen saturation, heart rate, and blood pressure were monitored.

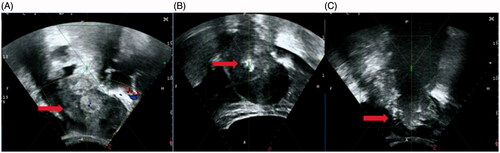

HIFU treatment was performed by the doctors with more than 10-year experience in HIFU. Before treatment, monitoring ultrasound showed the target area and adjacent tissues, and a treatment plan was made. Treatment started from the deep part of the lesion on the inferior side, and the focal point was at least 1 cm away from the border of the lesion. During the procedure, the sonication power and treatment rhythm were adjusted in real time according to the patient's response and gray scale changes of the lesion. When the range of gray-scale change covered the planned treatment area, color ultrasound showed no obvious blood supply, and contrast-enhanced ultrasound showed an obvious non-perfusion area in the treated tumor, then the treatment was terminated (). Recorded adverse events, treatment time, treatment power, sonication time, treatment intensity, treatment efficiency, and calculated non-perfused volume (NPV) ratio and energy efficiency factor (EEF).

Figure 1. The real-time ultrasound image obtained from a 46-year-old patient with metastatic pelvic tumor from endometrial cancer. (A). A pre-HIFU ultrasound image showed a recurrent lesion of 112 cm × 72cm × 71cm, with mixed echoic (arrow); (B). During HIFU treatment, a significant gray scale changed area was observed in the pelvic lesion (arrow); (C) ultrasound image obtained at 1301 s of sonication showed the gray scale changed area covered the pelvic lesion (arrow).

Follow-up

(1) All patients returned to their ward after HIFU treatment. The first three days following the treatment, a follow-up on the patient was conducted to evaluate any complications daily. The patients were instructed to report any discomfort in the first month, and return for follow-up at one, three, six and twelve months post-treatment for imaging and symptoms evaluation. The severity of adverse effects was evaluated according to the SIR classification system for complications by outcome: (1) Class A: no therapy, no consequence; (2) Class B: nominal therapy, no consequence; (3) Class C: require therapy, minor hospitalization (48 h); (5) Class E: permanent adverse sequelae; (6) Class F: death [Citation15].

(2) Pain: Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) pain scales method was adopted. Pain and discomfort were self-reported on a 10-point scale, with 0 representing no pain and symptoms and 10 representing unbearable pain.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the patients

The mean age of the patients was 54 (range: 33-76). The mean BMI was 21 (range: 17-25). The number of lesions treated was 12, the maximum volume of lesions was 1218.5 cm3, and the average volume was 238.0 cm3.

Clinical symptoms included lower abdominal pain in 5 patients, accounting for 62.5%; Asymptomatic 3 cases, accounting for 37.5%. The comprehensive adjuvant therapy was adopted after HIFU (). For personal reasons, 1 patient chose combined immunotherapy, chemotherapy and traditional Chinese medicine. Three patients were treated with combined chemotherapy and traditional Chinese medicine, while four patients were treated with combined traditional Chinese medicine only.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients with metastatic pelvic tumors.

Peri-procedure evaluation

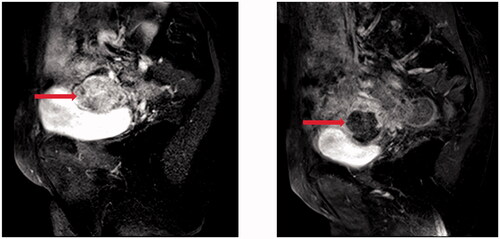

All patients completed HIFU ablation treatment in one session, and significant gray changes were observed in every lesion during HIFU treatment (). As shown in , the average treatment power was 357 (range: 166–400) watts, the average treatment time was 152 (range: 24–354) min, the average sonication time was 1354 (range: 86–3018)s, and the average treatment intensity was 477 (range: 215–813) s/h, the average therapeutic dose was 531418 (range: 14276–1204182) J, and the average NPV ratio was 66% (range: 24–91%) (). Post-HIFU MRI or CT examination showed that non-perfused area was observed in all the 12 treated lesions, 11 lesions were satisfactorily ablated, but 1 lesion was not satisfactorily ablated because it was close the intestine, the NPV ratio was only 24%.

Figure 2. Pre- and post-HIFU MRI images obtained from a 71-year-old patient with pelvic recurrence and metastasis from ovarian cancer. (A). Pre-HIFU MRI image showed a lesion adjacent to the bladder. The size of the lesion was 33 cm × 42cm × 45cm with significantly enhancement (red arrow). (B). One month after HIFU, contrast-enhanced MR showed a non-enhanced area of 30 cm × 33cm × 36cm (arrow).

Table 2. HIFU treatment results for metastatic pelvic tumors.

Adverse effects

During HIFU treatment, 5 patients experienced mild pain in the treated area (pain score: 1–2 points); 3 patients experienced moderate pain in the treated area (pain score: 3–4 points). Two patients reported transient skin burning sensation during the procedure of HIFU.

The main adverse effect after the HIFU treatment was pain in the treatment area. The pain score ranges from 1-3 points, which was tolerable and relieved spontaneously without specific treatment. Following the SIR classification, these adverse events were classified as Class A. No serious complications such as skin injury, intestinal injury, and nerve injury occurred ().

Table 3. Adverse effects evaluation of HIFU for metastatic pelvic tumors.

Pain score

The VAS scoring method was applied to all patients to assess the degree of pain. As shown in , 5 patients had pelvic pain before HIFU. After HIFU treatment, 3 patients reported pain relieved, 1 reported the pain score increased (case 7), and 1 refused to follow-up (case 4). During the period of 3–12 months after HIFU, the pain score increased, but it was still relieved in 2 patients. Of the 3 patients did not experience pelvic pain before HIFU, 2 reported pain score ranged from 1 to 2 at 1- and 3-month after HIFU, and 1 still did not have pain during the follow-up period.

Table 4. Comparison of pain scores during follow-up period.

Discussion

The cytoreductive surgery and systemic chemotherapy are the standard treatment for recurrent ovary cancer or metastatic pelvic tumors, but the overall outcome is poor. Therefore, the treatment for recurrent ovary cancer or metastatic pelvic tumors has always been a huge clinical challenge. Due to the influence of reoperation, limited radiotherapy, and drug resistance after multiple chemotherapies, the quality of life of the patients is severely reduced. The disease deteriorated again in 2.5 months on average. The 6-month mortality rate reaches 45.2%. Therefore, patients’ survival is not improved significantly [Citation16–20]. Several previous studies showed that the survival rate after tumor recurrence was related to whether or not to receive salvage surgery. Pelvic dissection is the surgical treatment for pelvic metastatic tumors first proposed by Brunschwing in 1948. If the recurrent tumor is confined to the pelvic cavity, then the tumor can be removed by pelvic tumor excision to improve tumor-free survival and overall survival [Citation21–24]. Pelvic dissection is divided into radical and palliative pelvic dissection according to the condition of surgical removal. Since metastatic pelvic tumors have no obvious clinical symptoms, most patients have already lost the opportunity of radical treatment when tumors are found. Therefore, palliative pelvic clearance is generally used as a surgery to improve the quality of life of patients. For example, palliative surgical treatment is adopted when patients experience urinary tract obstruction or intestinal obstruction. However, palliative surgery is traumatic, with many complications and a high risk of death. So it is necessary to carefully assess and select patients who may truly benefit from this treatment method [Citation25–27]. Clinically, effective interventions are needed to improve the quality of life of patients with metastatic tumors who have lost the opportunity of surgery.

As a noninvasive treatment, HIFU uses the thermal effect, cavitation effect and mechanical effect of ultrasound to achieve the coagulative necrosis of the tumor, so as to reach the therapeutic goal. A previous animal study has indicated that HIFU appears to be an effective treatment for ovarian cancer in the athymic nude mouse model [Citation28]. Therefore, HIFU may be a promising technique in treating recurrent ovarian cancer or pelvic metastatic tumors.

In this study, all patients completed HIFU ablation treatment in one session. Post-HIFU MRI or CT examination showed that an average NPV ratio of 66% (range: 24–91%) was achieved in 12 lesions from 8 patients using an average treatment power of 357 (range: 166–400) watts. The average treatment time was 152 (range: 24–354) min, the average sonication time was 1354 (range: 86–3018) s, and the average therapeutic ultrasound dose was 531418 (range: 14276–1204182) J. Among the 5 patients who had pelvic pain before HIFU, 3 patients reported relieved pain, 1 reported an increased pain score (case 7), and 1 refused to follow-up (case 4). The patient with recurrent ovarian cancer who refused to follow-up had an immediate NPV ratio of 24%. This low NPV ratio was because of the lack of a sufficient safe distance between the tumor and the intestine. HIFU ablation was applied to this patient since the patient and her family members strongly requested it. The purpose of the treatment was to ablate the lesion as much as possible to improve the quality of her life.

For palliative treatment of malignant tumors, safety is always a main concern. Pelvic tumors are often adjacent to bowels and sacrococcygeal nerves. Before HIFU treatment, MRI must be performed to determine the relationship between the tumor and the surrounding organs. At the same time, strict bowel preparation and skin preparation are required before HIFU treatment to reduce the risk of bowel injury and skin burn. During HIFU treatment, we must pay close attention to the distance between the focal point and the sacrum and the edge of the lesion, and protect the nerves and intestines to ensure the safety of the acoustic pathway. Currently, HIFU is widely used for the treatment of uterine fibroids and adenomyosis, and many studies have demonstrated its safety and effectiveness in the treatment of pelvic benign tumors [Citation29,Citation30]. The previous studies showed that the major complications that occurred after HIFU for uterine benign diseases include skin burns, leg pain, urinary retention, vaginal bleeding, hyperpyrexia, renal failure, acute cystitis, and bowel injury [Citation30]. In this study, HIFU was used for the treatment of metastatic tumors in the pelvic cavity for the first time. During the procedure, patients mainly complained mild pain in the treatment area and transient skin burning sensation. The patients didn’t report other adverse effects. Post-HIFU follow-up showed mild pain in the treated region, and the pain subsided within 1 day without special treatment. Among these 8 patients, no one had radiotherapy, but 6 patients had prior abdominal surgical scars because of prior open abdominal surgery for removing the primary tumor. Xiong et al. reported that patients with prior surgical scars have a higher risk of skin burns with increased severity in comparison with patients without prior surgical abdominal scars because the scar tissue had less blood supply, and had skin sensory loss [Citation31]. In this study, we didn’t find any patient had skin burns. Also, no other short-term and long-term major complications occurred. Therefore, our results indicated that recurrent ovary cancer or pelvic metastatic tumors can be safely ablated to achieve palliative treatment.

This study is limited because the sample size was small, the follow-up time was short, and the long-term survival rate of patients was not yet available; secondly, the primary tumors of the 8 patients were different, and the prognosis and treatment options were also different. Therefore, we plan to further expand the sample size in the future, provide patients with personalized treatment for pelvic metastases caused by different primary tumors, extend postoperative follow-up time, and further evaluate the safety and effectiveness of HIFU in the treatment of pelvic metastases from different sources.

Conclusions

As a noninvasive treatment modality, HIFU can be safely used to treat patients with recurrent ovary cancer or pelvic metastatic tumors and can relieve patients’ pain caused by tumors. Based on our preliminary results, we concluded that HIFU seems feasible in the treatment of recurrent ovary cancer or pelvic metastatic tumors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Salani R, Backes F, Fung M, et al. Posttreatment surveillance and diagnosis of recurrence in women with gynecologic malignancies: Society of Gynecologic Oncologists recommendations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(6):466–478.

- Armstrong D, Bundy B, Wenzel L, et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354(1):34–43.

- Trimbos J, Parmar M, Vergote I, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Collaborators-Adjuvant ChemoTherapy un Ovarian Neoplasm, et al. International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm trial 1 and Adjuvant Chemotherapy In Ovarian Neoplasm trial: two parallel randomized phase III trials of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with early-stage ovarian carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(2):105–112.

- Elit L, Fyles A, Devries M, Gynecology Cancer Disease Site Group, et al. Follow-up for women after treatment for cervical cancer: a systematic review. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;114(3):528–535.

- Temple W, Saettler E. Locally recurrent rectal cancer: role of composite resection of extensive pelvic tumors with strategies for minimizing risk of recurrence. J Surg Oncol. 2000;73(1):47–58.

- Liu J, Barry W, Birrer M, et al. Combination cediranib and olaparib versus olaparib alone for women with recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer: a randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(11):1207–1214.

- Chiantera V, Rossi M, De Iaco P, et al. Morbidity after pelvic exenteration for gynecological malignancies: a retrospective multicentric study of 230 patients. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24(1):156–164.

- Garcia-Ortega D, Villa-Zepeda O, Martinez-Said H, et al. Oncology outcomes in Retroperitoneal sarcomas: prognostic factors in a Retrospective Cohort study. Int J Surg. 2016;32:45–49.

- Konofaos P, Spartalis E, Moris D, et al. Challenges in the surgical treatment of retroperitoneal sarcomas. Indian J Surg. 2016;78(1):1–5.

- Jain V, Sekhon R, Giri S, et al. Robotic-assisted video endoscopic inguinal lymphadenectomy in carcinoma vulva: our experiences and intermediate results. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27(1):159–165.

- Kennedy JE. High-intensity focused ultrasound in the treatment of solid tumours. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(4):321–327.

- Zhang L, Wang ZB. High-intensity focused ultrasound tumor ablation: review of ten years of clinical experience. Front Med China. 2010; 4(3):294–302.

- Lam N, Rivens I, Giles S, et al. Prediction of pelvic tumour coverage by magnetic resonance-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound (MRgHIFU) from referral imaging. International journal of hyperthermia: the official journal of European Society for Hyperthermic Oncology. Int J Hyperthermia. 2020; 37(1):1033–1045.

- Wu Y, Chiang P. Cohort study of high-intensity focused ultrasound in the treatment of localised prostate cancer treatment: Medium-term results from a single centre. PloS One. 2020;15(7):e0236026

- Goldberg SN, Grassi CJ, Cardella JF, et al. Image-guided tumor ablation: standardization of terminology and reporting criteria. J Vasc Intervent Radiol. 2009;20(7):S377–SS90.

- Hong J, Tsai C, Lai C, et al. Recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of cervix after definitive radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60(1):249–257.

- Gadducci A, Guerrieri M, Cosio S. Adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix: Pathologic features, treatment options, clinical outcome and prognostic variables. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019;135:103–114.

- Choi M, Moon Y, Jung S, et al. Real-world experience with pembrolizumab treatment in patients with heavily treated recurrent gynecologic malignancies. Yonsei Med J. 2020;61(10):844–850.

- Liu Y, Wang G, Liu Y, et al. [Surgical concept and techniques of recurrent cervical cancer patients accompanied with high risk of intestinal obstruction after radical radiotherapy]]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2020;42(1):61–64.

- van Driel W, Koole S, Sikorska K, et al. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(3):230–240.

- Berek J, Howe C, Lagasse L, et al. Pelvic exenteration for recurrent gynecologic malignancy: survival and morbidity analysis of the 45-year experience at UCLA. Gynecologic Oncology. 2005;99(1):153–159.

- Jurado M, Alcázar J, Martinez-Monge R. Resectability rates of previously irradiated recurrent cervical cancer (PIRCC) treated with pelvic exenteration: is still the clinical involvement of the pelvis wall a real contraindication? a twenty-year experience. Gynecologic Oncology. 2010;116(1):38–43.

- Deng H, Wang J, Wang Z, et al. [Outcomes of perisurgery and short-time follow-up of pelvic exenteration for 17 cases with locally recurrent cervical cancer]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2020;55(4):259–265.

- Schmidt A, Imesch P, Fink D, et al. Indications and long-term clinical outcomes in 282 patients with pelvic exenteration for advanced or recurrent cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125(3):604–609.

- Schmidt A, Imesch P, Fink D, et al. Pelvic exenterations for advanced and recurrent endometrial cancer: clinical outcomes of 40 patients. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26(4):716–721.

- Berretta R, Marchesi F, Volpi L, et al. Posterior pelvic exenteration and retrograde total hysterectomy in patients with locally advanced ovarian cancer: clinical and functional outcome. Taiwanese J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;55(3):346–350.

- Berretta R, Capozzi V, Sozzi G, et al. Prognostic role of mesenteric lymph nodes involvement in patients undergoing posterior pelvic exenteration during radical or supra-radical surgery for advanced ovarian cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018;297(4):997–1004.

- Wu R, Hu B, Jiang LX, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound in ovarian cancer xenografts. Adv Ther. 2008;25(8):810–819.

- Liu X, Tang J, Luo Y, et al. Comparison of high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation and secondary myomectomy for recurrent symptomatic uterine fibroids following myomectomy: a retrospective study. BJOG. 2020;127(11):1422–1428.

- Liu Y, Zhang W, He M, et al. Adverse effect analysis of high-intensity focused ultrasound in the treatment of benign uterine diseases. Int J Hyperthermia. 2018;35(1):56–61.

- Xiong Y, Yue Y, Shui L, et al. Ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound (USgHIFU) ablation for the treatment of patients with adenomyosis and prior abdominal surgical scars: a retrospective study. Int J Hyperthermia. 2015;31(7):777–783.