Abstract

Objective

To investigate the MRI features and clinical outcomes of unexpected uterine sarcomas in patients after high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) ablation for presumed uterine fibroids.

Materials and methods

15,759 consecutive patients who came for HIFU treatment, from November 2008 to September 2019, for presumed uterine fibroids were retrospectively reviewed. All the patients had completed a pre-HIFU MRI. All MRI images were independently analyzed and interpreted by two radiologists in every center.

Results

According to the T2WI MRI features of hyperintensity, accompanied by irregular margins, necrosis or cystic degeneration, multi-lobulated lesion with internal septation, 46 patients were suspected to be uterine sarcomas before HIFU. Eleven patients were histologically diagnosed as uterine sarcomas after laparotomy. Among the 15713 patients who received HIFU treatment for presumed uterine fibroids, 8 patients were found to have occult recurrence during the follow-up period, and 6 were confirmed histologically as uterine sarcomas after laparotomy. The incidence rate of uterine sarcomas was 0.108% (17/15759). Among them, 12 cases were low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (LG-ESS) and 5 cases were uterine leiomyosarcoma (LMS). No histological dissemination of the sarcoma was detected in patients with unexpected uterine sarcomas.

Conclusion

Although some MRI features of uterine sarcomas and uterine fibroids overlapped, MRI is valuable in distinguishing between uterine fibroids and uterine sarcomas. HIFU does not seem to cause histological dissemination of the sarcoma, but follow-up visits should be strictly adhered to in order to detect unexpected uterine sarcomas at an early stage and to treat them in a timely manner.

Introduction

Uterine sarcomas are a type of heterogeneous tumor derived from mesenchymal cells of the uterus, accounting for about 8% of malignant uterine tumors [Citation1]. Uterine sarcomas can originate from uterine smooth muscle, endometrial stroma, or both, including uterine leiomyosarcoma (LMS), endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS), and malignant mixed Mullerian tumor of the uterus [Citation2]. Uterine sarcomas grow aggressively, and distant metastasis can occur at an early stage. Due to the lack of specific clinical manifestations of uterine sarcomas, the clinical misdiagnosis rate is relatively high. Previous studies showed that the preoperative diagnosis rate was only 35%. It was not uncommon to see some misdiagnosed cases and accordingly inappropriate surgeries that led to severe consequences for patients [Citation3]. Therefore, improving the accuracy of preoperative diagnosis is vital to avoid iatrogenic adverse consequences.

In recent years, high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) ablation has been more widely used in the management of uterine fibroids [Citation4,Citation5]. Since HIFU is a noninvasive treatment and no histological diagnosis occurs after treatment, excluding uterine sarcomas before HIFU has become a major concern. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers the best resolution of soft tissue, thus it has been routinely used in differentiating between uterine fibroids and uterine sarcomas before HIFU treatment. However, due to the diversity of MRI features of uterine sarcomas and the insufficient experience of radiologists at some centers, misdiagnosis of uterine sarcomas may occur. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the consequences of unexpected uterine sarcomas in patients who underwent HIFU ablation for presumed uterine fibroids.

Materials and methods

This retrospective study was approved by the ethics committees at our institutes and the requirement for an informed consent to do the research was waived.

Patients

15,759 consecutive patients, who presented with uterine fibroids between November 2008 and September 2019, were retrospectively reviewed. The patients presented at Suining Central Hospital of Sichuan, Yongchuan Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital of Chongqing, Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Nanchong Central Hospital of Sichuan, Three Gorges Central Hospital of Chongqing, Zigong Fourth Hospital of Sichuan, Liangshan First Hospital of Sichuan, Mianyang Central Hospital of Sichuan, Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University and Deyang People's Hospital of Sichuan. The medical histories of the patients were collected. Following a physical examination, routine laboratory tests, ECG, ultrasound examination and chest X-ray, but prior to HIFU treatment, MRI was performed on patients.

Inclusion criteria for HIFU were as follows: (1) patients with symptomatic fibroids requiring treatment; (2) patients able to communicate with the nurse or physician during HIFU procedure; (3) the size of the dominant fibroid was smaller than 15 cm in diameter.

Exclusion criteria: (1) menstruating, pregnant or lactating women; (2) patients with contraindications to MRI (allergic to contrast, metal foreign bodies in treatment area e.g. IUCD, Filchi clips); (3) patients with suspected or confirmed uterine malignancy.

MRI examination

The equipment used for MRI examination at various centers was Philips Achieva 1.5 T MRI, Philips Avanto1.5T MRI or GE Signa Excite 1.5 T MRI. The standard T1 weighted image (T1WI), T2 weighted image (T2WI) and contrast-enhanced sequences were selected. The parameters were: axial and sagittal T2WI (TR/3000-6000ms, TE/75-108ms), transverse T1WI (TR/400-800 ms, TE/9.4-11ms), and Tl-VIBE-FS (TR/4.9-5.8 ms, TE/2.3-2.7 ms). Gadolinium (GD-DAPA) was selected as the contrast agent for contrast-enhanced MRI scanning.

MRI image analysis

All MRI images were independently analyzed and interpreted by two radiologists with more than 10 years of radiographic experience in obstetrics and gynecology at each of the centers. Two radiologists independently evaluated the image features, including (1) T2WI signal intensity of the lesion; (2) T1WI signal intensity of the lesion; (3) Lesion margin; (4) Cystic degeneration within the lesion; (5) Multi-lobulated lesion with internal septation; (6) Lesion volume; (7) Contrast-enhancement of the lesion. If there was any disagreement with the diagnosis, these two radiologists needed to discuss it with their supervisor and reach a consensus. For example, if a lesion is characterized by T2 hyperintensity, accompanied by irregular margins, with necrosis or cystic change in the center of the lesion, multi-lobulated lesion with internal septation, then the lesion is suspected to be a uterine sarcoma. Therefore, if uterine sarcomas were suspected, patients were excluded from HIFU treatment, and gynecological surgery was recommended instead. If uterine sarcomas were not suspected, HIFU treatment was recommended.

HIFU ablation

The HIFU procedure was performed under intravenous conscious sedation (fentanyl and midazolam). A Model-JC or Model-JC200 Focused Ultrasound Tumor Therapeutic System (Chongqing Haifu Medical Technology Co., Ltd.) was used for HIFU treatment. This system contains an ultrasound imaging device (MyLab 70, Esaote, Genova, Italy) situated at the center of the transducer, to provide real-time monitoring for the treatment. The patients were placed in a prone position, with the abdominal wall in contact with degassed water. The sonication began on the inferior side of the fibroid, moved toward the superior side, and then from the posterior area to the anterior area of the fibroid. The focus was kept at least 1.5 cm away from the endometrium and boundary of the fibroid. During the procedure, the sonication power was regulated according to the feedback from the patient and the changing grayscale on ultrasound imaging. The treatment was terminated when the entire fibroid was hyperechoic, or the enhanced ultrasound showed no blood flow in the fibroid.

Follow-up

All patients were discharged from the hospital 1 day after HIFU treatment, and vital signs were monitored throughout the hospital stay. The patients were asked to return to the hospital at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months after HIFU for follow-up imaging evaluation. If occult recurrence was detected, the patient was referred to gynecological surgery.

Histological examination

The diagnosis of uterine sarcomas was based on the 2014 World Health Organization (WHO) classification standards [Citation6]. The histological examination was performed by pathologists with more than 10 years of experience in gynecological pathology. This study focused on factors such as tumor size, degree of differentiation, marked nuclear atypia, mitotic activity, round cell morphology, and necrosis.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 20.0 software (IBM Company, Chicago IL) was used for statistical analysis. Normally distributed data were reported as mean ± standard deviation and analyzed by independent sample t-tests; skewed distribution data were reported as medians and interquartile ranges. The Mann-Whitney non-parametric test was used for statistical analysis. The Chi-square test was performed on count data; a p < 0.05 was defined as statistically different.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The median age of the 15759 patients in this study was 43 (interquartile range: 40–47) years, the median BMI was 22.8 (interquartile range: 21.0–24.8) kg/m2, the median uterine volume was 188.1 (interquartile range: 132.9–273.3) cm3, and the median lesion volume was 30.2 (interquartile range: 9.7–68.0) cm3. According to the MRI features of the lesions, which are characterized by T2 hyperintensity, accompanied by irregular margins, unclear margins, necrosis or cystic degeneration in the center of the lesions, multi-lobulated lesions with internal septation ( and ), 46 of 15,759 patients were suspected to have uterine sarcomas. Among the 46 patients with suspected uterine sarcomas, 11 patients were histologically diagnosed as uterine sarcomas, 1 was histologically diagnosed as a smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential, and 34 cases were histologically diagnosed as uterine fibroids after laparotomy. Among the 15,713 patients who were first diagnosed as uterine fibroids by MRI images and received HIFU treatment, 8 patients were found to have occult recurrence by ultrasound during the 5–26 month follow-up period after HIFU treatment. These patients were further examined by MRI, and after a multidisciplinary team consultation, they were suspected of having uterine sarcomas and underwent gynecological surgery. Six of them were confirmed histologically as uterine sarcomas. Therefore, a total number of 17 were diagnosed as uterine sarcomas after surgery, with an incidence rate of 0.108% (17/15,759). Among them, 12 cases were histologically diagnosed as low-grade ESS (LG-ESS) and 5 cases were LMS. The baseline characteristics of the 12 patients with LG-ESS and 5 patients with LMS are summarized in . The average age of the 12 patients with LG-EES was 40.8 ± 6.7 years, and the average age of the 5 patients with LMS was 42.0 ± 4.4 years. All patients were premenopausal. Based on FIGO tumor staging, 10 patients with LG- ESS were in stage I, 1 was in stage II, 1 was in stage IV; 5 patients with LMS were all in stage I.

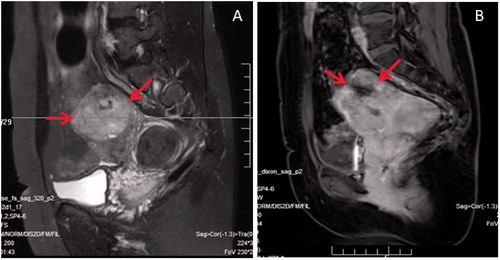

Figure 1. MR images obtained from a 44-year-old patient. She had no symptoms, but came for HIFU treatment. (A) T2WI showed two lesions, one hyperintense mass with an ill-defined margin located at the fundus of the uterus (arrows) which was suspected to be a uterine sarcoma; another one located adjacent to the cervix of the uterus with hypointense, well defined margin which was a uterine fibroid. (B) Contrast-enhanced MRI showed irregular enhancement of the lesion located at the fundus of the uterus (arrows). After reviewing the pre-HIFU MRI, the patient was referred to surgery. She was histologically diagnosed as LMS.

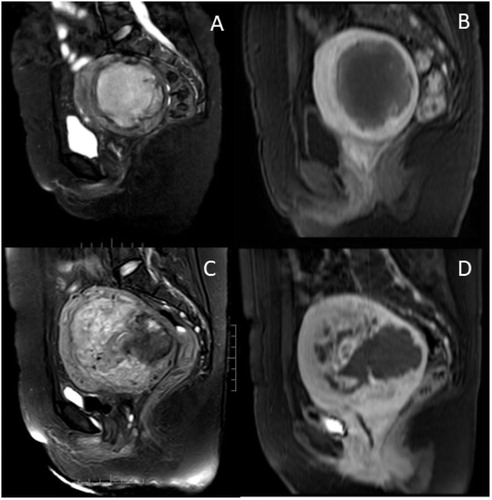

Figure 2. A 37-year-old patient came for HIFU treatment. (A). Pre-HIFU (T2WI) MRI showed a hyperintense mass with an irregular margin. (B) Pre-HIFU contrast-enhanced MRI showed central non-enhancement of the lesion; she was misdiagnosed as degeneration of uterine fibroids and had HIFU treatment. (C) T2WI obtained 10 months after HIFU showed an ill-defined mass of heterogeneous signal intensity. (D) Contrast enhanced MRI obtained 10 months after HIFU showed irregular enhancement of the lesion. The recurrent mass was suspected to be uterine sarcoma. The diagnosis was histologically confirmed after surgery.

Table 1. Comparison of baseline characteristics between patients with endometrial stromal sarcoma and uterine leiomyosarcoma.

Comparison of MRI features of uterine sarcomas and uterine fibroids in patients who were suspected to have uterine sarcomas before HIFU

We carefully reviewed the MRI images of the 46 patients who were suspected to have uterine sarcomas before HIFU and further compared the MRI features of the histologically confirmed 34 uterine fibroids and 11 uterine sarcomas. Although overlap exists in the imaging appearances of uterine fibroids and uterine sarcomas, the results of this study showed that 90.9% of uterine sarcoma lesions presented as ill-defined margins, which was significantly higher than that of uterine fibroids (p = 0.023); 72.7% of uterine sarcomas presented as hyperintense on T2WI, which was also significantly higher than that of uterine fibroids (p = 0.020); In addition, the ratio of no central enhancement in uterine sarcomas was significantly higher than that of uterine fibroids (p = 0.037) ().

Table 2. Comparison of MRI features of uterine sarcomas and uterine fibroids in patients who were suspected to have uterine sarcomas before HIFU.

Comparison of MRI imaging features between LG-ESS and LMS

We carefully reviewed the MRI images of the 17 patients with uterine sarcomas. Based on T2WI, 83.3% of the LG-ESS lesions presented as hyperintense, 8.3% of the LG-ESS lesions presented as either hypointense or isointense; 60% of the LMS lesions presented as hyperintense, 40% presented as heterogeneous. Both LG-ESS and LMS presented with irregular margins and unclear margins. On T1WI, 33.3% of the LG-ESS lesions presented with high signal intensity, while 40% of the LMS lesions presented with high signal intensity. The contrast-enhanced MRI showed no enhancement in 2 (18.2%) or irregular central non-enhancement in 4 (36.4%) of the LG-ESS lesions, and just 1 (20.0%) in the LMS lesions. On T2WI, 83.3% of the LG-ESS showed ill-defined margins, while all the LMS showed ill-defined margins (p = 0.075). We didn’t find any significant difference in tumor volume, the proportion of irregular margins, ill-defined margins, high signal intensity on T1WI and T2WI, and pocket-like degeneration between the LG-ESS and LMS lesions. However, 75% of LG-ESS lesions were lobulated with internal septation, which was not seen in the cases with uterine leiomyosarcoma ().

Table 3. Comparison of MRI features between endometrial stromal sarcoma and uterine leiomyosarcoma.

Comparison of MRI features of uterine sarcomas in patients diagnosed before and after HIFU

To clarify the cause of misdiagnosis before HIFU treatment, we further compared the MRI features of 11 patients with uterine sarcomas who were diagnosed before HIFU treatment and 6 cases of uterine sarcomas who were diagnosed after HIFU treatment. No significant difference was observed in histological type, shape of the lesions, margin of the lesions, ratio of high signal intensity on T2WI, ratio of lobulated lesions with internal septation, pocket-like degeneration, and enhancement manifestation of the lesions ().

Table 4. Comparison of MRI features of uterine sarcomas in patients diagnosed before and after HIFU.

Comparison of follow-up results of patients with uterine sarcomas diagnosed before and after HIFU treatment

All the patients with uterine sarcomas underwent laparotomies. After surgery, they received chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Among the 11 patients with uterine sarcomas whose histological diagnosis was confirmed by surgery before HIFU, 8 cases were LG-ESS and 3 cases were LMS. By the end of September 2020, after an average follow-up of 29.3 ± 13.5 (range: 13–54) months, 1 patient was lost to follow-up, 10 patients were still alive. Among the 6 patients with unexpected uterine sarcomas after HIFU for presumed uterine fibroids, 4 patients were LG-ESS and 2 were LMS. The mean non-perfused volume (NPV) ratio of 86.8 ± 11.7% (range: 64.8–97.2%) was achieved in the 6 uterine sarcoma lesions. During the follow-up period, one patient complained of abnormal vaginal bleeding after HIFU treatment, while the other 5 patients did not report any symptoms. These patients underwent laparotomy for complete oncological staging, and no histological dissemination of the sarcoma was registered. By the end of September 2020, after a median of 20.5 (range: 13–74) months follow-up, 1 patient was lost to follow-up, 1 patient with LMS died 39 months after HIFU, 4 patients were still alive.

Discussion

Uterine sarcomas are a rare type of malignant uterine tumor. Among patients undergoing surgery for uterine fibroids, the incidence of uterine sarcomas has been reported as 1:8300 to 1:352 in different studies [Citation7–13]. Our study showed that the incidence of uterine sarcomas was 0.108%, or 1/927, in patients receiving HIFU treatment for presumed uterine fibroids, which is consistent with previous studies [Citation7–13]. Studies have shown that LMS is the most common type of uterine sarcoma, accounting for 63% of uterine sarcomas, and ESS accounts for 21% of uterine sarcomas [Citation14,Citation15]. However, among the 17 cases of uterine sarcomas confirmed in this study, 70.6% (12/17) were LG-ESS, 29.4% (5/17) were LMS. It is generally believed that ESS is more common in young patients, while LMS is more common in perimenopausal women. In this study, the median age of the 15,759 patients with presumed uterine fibroids was 43 (interquartile range: 40–47) years. The average age of ESS patients was 40.8 ± 6.7 (range: 27–50) years and the average age of the 5 patients with LMS was 42.0 ± 4.4 (range: 35–46) years. The results showed that patients with ESS were younger than patients with LMS. Although no significant difference was observed in age between patients with ESS and LMS, it may be explained by the small sample size. Therefore, further studies are required to ascertain whether the ESS patients were more common in this study because the patient sample was younger.

The MRI imaging features of typical uterine fibroids include well-defined masses of hypointensity, isointensity, or hyperintensity as compared to the myometrium on T2WI (). Uterine fibroids may have a high signal intensity rim on T2WI. Uterine fibroids may also have heterogeneous appearances, with minimal or irregular enhancement due to different types of degeneration. In contrast, uterine sarcomas often appear as solitary lesions, with ill-defined margins, and irregular shapes. Uterine sarcomas often show hyperintensity on T2WI, are associated with hemorrhage and necrosis on T1WI, and may have the presence of an unenhanced pocket-like area on contrast-enhanced MRI ( and ) [Citation16]. Based on the above mentioned characteristics, 46 patients with suspected uterine sarcomas were screened from the 15,759 patients before HIFU treatment. Of those patients, 11 patients were diagnosed as uterine sarcomas, and 1 was a smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential after surgery. Although an overlap exists in MRI features of uterine sarcomas and uterine fibroids, we further compared the MRI features of the histologically confirmed 34 uterine fibroids and 11 uterine sarcomas. The results from this study revealed that, more than uterine fibroids, uterine sarcomas are characterized by a hyperintense mass with ill-defined margins and no central enhancement in the lesions (). Among the 15,713 patients who received HIFU treatment, 8 patients experienced a recurrence of the lesion with an abnormal growth rate during the follow-up period. After multidisciplinary consultation, based on the history and MRI features of a hyperintense mass with an irregular margin, an ill-defined margin, and irregular enhancement, they were suspected to be uterine sarcomas. Of these patients, 6 patients were histologically diagnosed with uterine sarcomas after surgery. All the patients with suspected uterine sarcomas underwent laparotomy; 12 patients were histologically diagnosed as LG-ESS, 5 were LMS, 1 was a smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential, and 36 were uterine leiomyomas. We further compared the MRI images of LG-ESS and LMS; both LG-ESS and LMS showed ill-defined margins and hyperintensity on T2WI. At the same time, there was no difference in terms of enhancement, but up to 75% of LG-ESS showed multi-lobulated lesions with internal septation, while LMS lesions did not show this feature. In this study, 6 patients with unexpected uterine sarcomas were treated with HIFU for presumed uterine fibroids. We retrospectively reviewed the pre-HIFU MRI images and compared with the 11 patients with uterine sarcomas whose diagnosis was made before HIFU treatment. The results showed that the two groups of patients had no significant differences in histological type composition, lesion shape, lesion margins, T2 signal intensity, T1WI signal intensity, and appearance of enhancement (). This indicated that the misdiagnosis was mainly related to the experience of the physician. Fortunately, the results from this study showed that patients with unexpected uterine sarcomas who were treated with HIFU for presumed uterine fibroids, then underwent laparotomy for complete oncological staging, and no histological dissemination of the sarcoma was found. Also, the follow-up results showed that there is no statistical difference in overall survival of patients with uterine sarcomas treated with laparotomy and unexpected uterine sarcomas treated with laparotomy after HIFU. However, it is necessary to further train physicians to increase the accuracy of diagnosis of uterine sarcomas. In this study, we noted that the NPV ratio achieved in the 6 uterine sarcoma lesions was large. It seemed that the response of uterine sarcomas to HIFU was good. Therefore, follow-up procedures should be implemented in a standardized manner, and follow-up visits for 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, and 24 months after HIFU treatment should be strictly followed in order to detect unexpected uterine sarcomas at an early stage and to treat them on time.

This study is limited because the MRI examination was performed by different radiologists from different centers and thus some bias may occur. This study is also limited because the sample size is small and the follow-up time is relatively short in some cases. Therefore, a large-scale multicenter study, with standard protocols and follow-up for a longer time period, should be performed to confirm the findings.

Conclusion

In summary, MRI can be used to distinguish uterine fibroids and uterine sarcomas and serves as an important method for screening patients with uterine fibroids before HIFU treatment. Although uterine sarcomas often show hyperintensity on T2WI, are associated with hemorrhage and necrosis on T1WI, and may have the presence of an unenhanced pocket-like area on contrast-enhanced MRI, some MRI features of uterine sarcomas and uterine fibroids overlap. Thus, the accuracy of excluding uterine sarcoma by individual features may be insufficient and thus follow-up visits for 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, and 24 months after HIFU treatment should be strictly followed in order to detect unexpected uterine sarcomas at an early stage and to treat them in a timely manner.

Disclosure statement

Lian Zhang is a senior consultant to Chongqing Haifu. No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Wu T, Yen T, Lai C. Clinical presentation and diagnosis of uterine sarcoma, including imaging. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;25(6):681–689.

- Shah S, Jagannathan J, Krajewski K, et al. Uterine sarcomas: then and now. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(1):213–223.

- Ricci S, Stone R, Fader A. Uterine leiomyosarcoma: Epidemiology, contemporary treatment strategies and the impact of uterine morcellation. Gynecologic Oncology. 2017;145(1):208–216.

- Liu X, Tang J, Luo Y, et al. Comparison of high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation and secondary myomectomy for recurrent symptomatic uterine fibroids following myomectomy: a retrospective study. BJOG. 2020;127(11):1422–1428.

- Chen J, Li Y, Wang Z, Committee of the Clinical Trial of HIFU versus Surgical Treatment for Fibroids, et al. Evaluation of high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation for uterine fibroids: an IDEAL prospective exploration study. BJOG. 2018;125(3):354–364.

- Kurman RJ, Carcangiu ML, Herrington CS, et al. WHO classification of tumours of female reproductive organs. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2014. p. 141–145.

- Pritts E, Vanness D, Berek J, et al. The prevalence of occult leiomyosarcoma at surgery for presumed uterine fibroids: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Surg. 2015;12(3):165–177.

- Harlow BL, Weiss NS, Lofton S. The epidemiology of sarcomas of the uterus. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1986;76(3):399–402.

- Chen I, Lisonkova S, Joseph K, et al. Laparoscopic versus abdominal myomectomy: practice patterns and health care use in British Columbia. JOGC. 2014;36(9):817–821.

- Takamizawa S, Minakami H, Usui R, et al. Risk of complications and uterine malignancies in women undergoing hysterectomy for presumed benign leiomyomas. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1999;48(3):193–196.

- Leibsohn S, d'Ablaing G, Mishell DR, et al. Leiomyosarcoma in a series of hysterectomies performed for presumed uterine leiomyomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162(4):968–976.

- Bogani G, Cliby W, Aletti G. Impact of morcellation on survival outcomes of patients with unexpected uterine leiomyosarcoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(1):167–172.

- Bosch TVD, An C, Morina M, et al. Screening for uterine tumours. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;26(2):257–266.

- Tropé CG, Abeler VM, Kristensen GB. Diagnosis and treatment of sarcoma of the uterus. A review. Acta Oncologica. 2012;51(6):694–705.

- Kildal W, Pradhan M, Abeler VM, et al. Beta-catenin expression in uterine sarcomas and its relation to clinicopathological parameters. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(13):2412–2417.

- DeMulder D, Ascher S. Uterine leiomyosarcoma: can MRI differentiate leiomyosarcoma from benign leiomyoma before treatment? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2018;211(6):1405–1415.