Abstract

Background

Whole-body hyperthermia (WBH) has shown promise as a non-pharmacologic treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD) in prior trials that used a medical (infrared) hyperthermia device. Further evaluation of WBH as a treatment for MDD has, however, been stymied by regulatory challenges.

Objective

We examined whether a commercially available infrared sauna device without FDA-imposed limitations could produce the degree of core body temperature (101.3 °F) associated with reduced depressive symptoms in prior WBH studies. We also assessed the frequency of adverse events and the amount of time needed to achieve this core body temperature. We explored changes (pre-post WBH) in self-reported mood and affect.

Methods

Twenty-five healthy adults completed a single WBH session lasting up to 110 min in a commercially available sauna dome (Curve Sauna Dome). We assessed core body temperature rectally during WBH, and mood and affect at timepoints before and after WBH.

Results

All participants achieved the target core body temperature (101.3 °F). On average, it took participants 82.12 min (SD = 11.3) to achieve this temperature (range: 61–110 min), and WBH ended after a participant maintained 101.3 °F for two consecutive minutes. In exploratory analyses of changes in mood and affect, we found that participants evidenced reductions (t[24] = 2.03, M diff = 1.00, p=.054, 95% CI [−2.02,0.02]) in self-reported depression symptoms from 1 week pre- to 1 week post-WBH, and reductions (t[24]= −2.93, M diff= −1.72, p=.007, 95% CI [−2.93, −0.51]) in self-reported negative affect pre-post-WBH session.

Conclusion

This novel WBH protocol holds promise in further assessing the utility of WBH in MDD treatment.

Trial registration

This trial was registered at clinicaltrivals.gov (NCT04249700).

Introduction

A growing body of literature suggests that whole-body heating (WBH) practices may be useful in the treatment of clinical depression. One open trial tested a single session of WBH, wherein 16 adult participants with clinical depression achieved a core body temperature of 101.3 °F. Within a week of the WBH session, participants experienced a rapid and robust reduction in depressive symptoms [Citation1]. Building on this, a more recent randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled trial in a sample of 29 adults with major depressive disorder (MDD) used the same protocol as in [Citation2]. Participants who received WBH, relative to those who received sham WBH, experienced rapid and robust reductions in depressive symptoms [Citation2]. Notably, participants reported sustained reductions in depressive symptoms up to 6 weeks following their single WBH session. Taken together, these trials suggest that WBH holds promise as a novel non-pharmacologic treatment for depression.

Despite promising initial trials [Citation1,Citation2] and emerging theoretical frameworks [Citation3,Citation4] for the use of WBH as a non-pharmacologic treatment for depression, researchers have yet to develop easily accessible and disseminable WBH protocols that can be tested in clinical trials in the United States. This is largely due to the complexity and cost of administering WBH protocols that use medical hyperthermia devices foreign to the U.S. Specifically, the medical (infrared) hyperthermia devices used in the prior trials require an Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) before they can be used in clinical trials. This results from an FDA determination that these infrared medical hyperthermia devices pose serious enough health risk that their use is currently confined to FDA-approved studies conducted in carefully monitored and costly medical environments. Furthermore, to move out of the realm of research studies and into clinical practice, protocols using these types of medical hyperthermia devices would likely require costly Phase 3 studies for approval. Though WBH using medical hyperthermia devices has shown promise and may eventually receive FDA approval for clinical use, there remains a significant need to identify other potential means of inducing clinically relevant hyperthermia that will be easier to both study and make available for clinical use.

To build upon promising initial findings showing the use of WBH to be associated with rapid and robust reductions in depression symptoms, we sought to develop a cost-effective, highly accessible WBH protocol using a commercially available hyperthermia device that has been determined not to pose a significant risk and that therefore does not require FDA clearance for use. Our primary study outcomes were [Citation1] whether a commercially available sauna device could induce a core body temperature equal to that used in prior studies of WBH for MDD (i.e., 101.3 °F); and [Citation2] the frequency of adverse events causing cessation of WBH sessions. Our secondary study outcome was the amount of time needed to achieve a core body temperature of 101.3 °F in a commercially available sauna device. We also explored changes (pre-post WBH) in self-reported mood and affect. The University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Institutional Review Board (IRB) designated this commercially available device to post non-significant risk (NSR) under 21 CFR 12.

Methods

Participants

We enrolled participants in the San Francisco Bay Area between September 2019 and March of 2020. We recruited participants via social media, posted flyers, and university email marketing. Eligible participants were men and women aged 18 to 45 years who were medically healthy, premenopausal (females), without current psychiatric treatment or mental health disorders, not using medications or drugs with known effects on thermoregulatory processes, and meeting other inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in Appendix A. Of note, exclusion criteria were largely based upon feasibility and safety. Specifically, we included participants with body mass index (BMI) values < =30 and waist sizes of < =40 inches for men and < =35 inches for women to ensure that participants would fit comfortably in the sauna dome. We excluded women who were pregnant or at risk of becoming pregnant as the effects of WBH on pregnancy are unknown. Due to prior work suggesting lack of improvements in mental health following WBH among individuals using antidepressant medications, we excluded individuals using these medications. We also excluded participants using a broad range of medications and substances (e.g., nicotine) due to unknown possible interactions with WBH.

Procedures

The University of California San Francisco (UCSF) institutional review board (IRB) approved all study procedures and all participants provided written consent. All participants completed online screening to confirm eligibility and, if eligible, completed a telephone screening to further confirm eligibility and to complete scheduling procedures. Participants completed a baseline visit (Visit 1, Day 1) wherein they completed self-report measures on a dedicated study iPad using the Qualtrics platform (qualtrics.com), anthropometric assessments, and (if female) a urine pregnancy test. At the baseline visit, we reviewed key study compliance factors with all participants; specifically, we asked that, for the 15-day study period, they refrain from (a) using alcohol, nicotine, or psychoactive drugs, (b) using a sauna outside of the study, and (c) exercising the day of their WBH session. Additionally, we asked that participants refrain from using psychoactive drugs in the two weeks prior to their first study visit and during the entire course of their study participation. Each participant completed a single WBH session: Seven days after the baseline assessment (Visit 1), participants completed their WBH visit (Visit 2, Day 8), before and after which they completed self-report measures. Seven days later, participants completed their final visit (Visit 3, Day 15) wherein they again completed self-report measures.

Study intervention

WBH took place using the Clearlight Sauna Dome and ancillary equipment (Mindray iPM-9800) to assess core temperature via continuous rectal measurement. Sauna Dome ambient temperatures reached approximately 135 °F and participants were given up to 110 min to reach a core (rectal) body temperature of 101.3 °F. Two research assistants (RAs) remained with the participant throughout the WBH session; one sat on a stool near the participant’s head and applied cool cloths and ice to the participant’s head and neck and provided the participant with water to drink as often as the participant requested it. A second RA monitored the participant’s core body temperature on the Mindray iPM-9800, which was attached to an indwelling rectal probe that participants inserted before the start of the WBH session. The Mindray iPM-9800 yields a reading every 60 s. After reaching a core body temperature of 101.3 °F for two consecutive minutes, the participant began a 30-min cool-down period in the Dome (Dome heater turned off), during which time their body temperature typically continued rising in the first several minutes, before falling (see Results).

Measures

Participants completed self-report measures assessing mood and affect on a dedicated study iPad using a Qualtrics platform (qualtrics.com). At each study visit, we assessed the following: depressive symptoms using the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depression Symptomatology (QIDS) [Citation5]. We selected this scale based on its widespread use in non-depressed populations (as that is the sample for the current study), as well for evidence that it captures meaningful change in depressive symptoms in normal populations undergoing novel treatments for depression [Citation6–8]. We assessed anxiety symptoms using the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder-seven (GAD-7) [Citation9], overall well-being using the 5-item World Health Organization-five (WHO-5) [Citation10], and positive and negative affect using the 20-item Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) [Citation11]. At the first and final visits, participants completed the standard PANAS, which asks about affect over the past week. At the second visit (wherein participants completed their single WBH session), participants completed an altered version of this measure, twice (before and after the WBH session). Specifically, we altered the timeframe of the lead question to state ‘indicate the extent you have felt this way right now’ rather than ‘the past week.’

Compliance

Participants completed compliance questions on the study iPad using a Qualtrics platform (qualtrics.com) at their second and final study visits. Specifically, we asked them if, during the course of their participation, they used alcohol, nicotine, or psychoactive drugs, or used a sauna outside of the study. We asked if they had engaged in exercise the day of their WBH session. We also asked participants if they used any over-the-counter medications, such as pain relievers or allergy medications. We indexed adverse events as any untoward event that resulted in abortion of study procedures.

Statistical analysis

To assess the frequency with which a commercially available sauna device was able to induce a core body temperature of 101.3 °F in a single WBH session lasting up to 110 min, we computed a percentage (number of participants who achieved 101.3 °F divided by the total number of participants who began WBH sessions). We assessed the frequency of adverse events causing cessation of WBH sessions by keeping a count of any such events. We assessed the amount of time needed to achieve a core body temperature of 101.3 °F in the sauna device as the average number of minutes and report this with its standard deviation. We report means and standard deviations for each self-report measure and computed differences across various timepoints (i.e., Visit 1 versus Visit 3, and pre- versus post-WBH during Visit 2) using paired samples t-tests.

Results

Participants

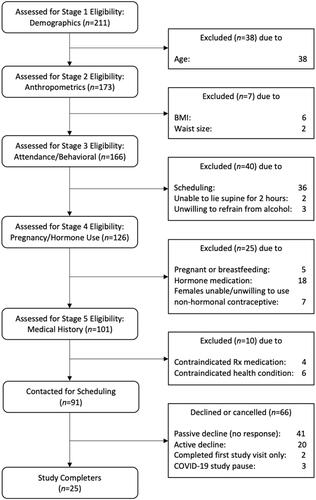

Participant flow appears in , and participant characteristics appear in . Participants were 60% (n = 15) White, 68% male, and an average age of 31.4 years old.

Figure 1. Participant flow through study. We paused the study in March of 2020 due to COVID-19, and the three eligible and willing participants therefore did not have the opportunity to participate.

Table 1. Participant Characteristics.

Induction of core body temperature of 101.3 °F

All 25 participants in the study achieved a core body temperature of 101.3 °F within 110 min of commencing heating in the Sauna Dome. The time to reach 101.3 °F varied across participants but required a mean (SD) length of 82.11 (11.3) minutes (range, 61–110 min). During the cool-down period, core body temperature typically rose to an average (SD) of 101.5 (0.17)°F and began to decrease, on average (SD) 6.51 (4.29) minutes after terminating active heating.

Adverse events

Across the 25 WBH sessions no serious adverse events occurred. All participants completed sauna sessions without needing to discontinue the procedure.

Subjective experience

Fifteen of the 25 participants expressed moments of discomfort in the form of telling research assistants that they were feeling very hot. Twenty-one of the 25 participants made specific requests during the WBH session in the form of requesting (a) something to drink, (b) sweat to be dried (e.g., on the back of the neck), (c) a cool cloth to be put at a different location on their face or neck, (d) an itch to be scratched (participants were unable to use their hands during the WBH session as their arms were within the sauna dome), or other similar requests.

Compliance

Because we implemented the assessment of study compliance midway through the trial, 19 participants (of 25) completed these questions. No participants reported using alcohol, nicotine, or psychoactive drugs during their study participation window, and no participants reported using psychoactive drugs in the two weeks prior to their first study visit. One participant reported engaging in mild exercise (that did not cause sweating) the night before and morning of the sauna visit. One participant reported using a sauna outside study procedures twice during the course of the trial and one participant reported using over-the-counter cold medication during the trial.

Mood and affect

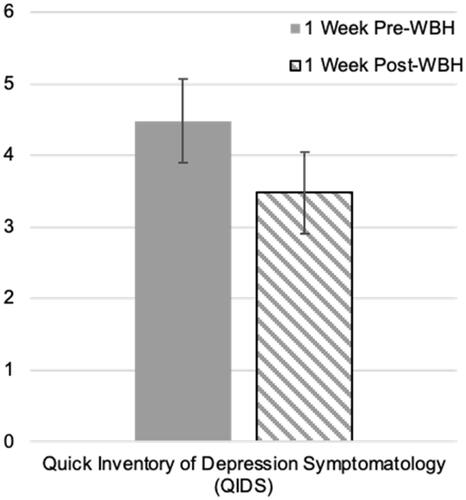

Changes from visit 1 to visit 3

As shown in , although participant scores on the QIDS were initially in the normal range (<5 points), depressive symptoms as indexed by the QIDS showed a statistical trend-level decrease from one week prior, to one week following, the WBH session (t[24] = 2.03, M diff = 1.00, p=.054, 95% CI [−2.02, 0.02]). Similarly, negative affect, as indexed by the PANAS, decreased during this time period, (t[24]= −2.45, M diff= −2.44, p=.022, 95% CI [−4.50, −0.38]). We did not find meaningful changes in measures assessing quality of life (WHO), anxiety symptoms (GAD-7), or positive affect (PANAS) ().

Figure 2. Change in depression symptoms as indexed by the Quick Inventory of Depression Symptomatology (QIDS) from 1 week before to 1 week after whole-body heating (WBH).

Table 2. Changes in self-report measures of mood and affect.

Changes from pre- to post-WBH (visit 2)

As shown in , participants reported significantly less negative affect after, relative to before, their WBH session, (t[24]= −2.93, M diff= −1.72, p=.007, 95% CI [−2.93, −0.51]). We did not find meaningful changes in positive affect during this time period.

Discussion

This report details a novel whole-body hyperthermia (WBH) protocol that uses a commercially available sauna device. We found that a single-session WBH protocol using this commercially available infrared sauna device achieved a core body temperature of 101.3 °F in a similar time frame to a medical hyperthermia device used in trials targeting clinical depression [Citation1,Citation2]. Further, participants did not experience any serious adverse events using this protocol. These findings represent the key step of developing a WBH protocol for use in future clinical trials: This protocol uses a widely available sauna device and is viable in outpatient healthcare settings.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a serious public health problem that afflicts more than 300 million people worldwide and it is the leading cause of life-years lost to disability. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), depressive disorders will eclipse coronary artery disease as the leading causes of debilitating illnesses by 2030 [Citation12]. Available pharmacological modalities suffer from important limitations, including limited efficacy, delayed onset of action, and significant side effects that can impair quality of life and result in treatment non-adherence and/or discontinuation [Citation13–15]. Only 30% of patients achieve symptomatic remission following initial pharmacologic treatment [Citation16]. Taken together, this suggests that treatment options for depression do not meet growing clinical needs. Developing novel treatment paradigms, including body-based treatments such as WBH, may represent one avenue through which to address critical gaps in currently available treatment options.

Epidemiological data and some experimental data suggest that WBH practices are associated with reduced risk for both physical and mental health problems. For example, regular sauna bathing has been associated with reduced risk for cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality [Citation17,Citation18], stroke [Citation19], dementia and Alzheimer’s disease [Citation20,Citation21], acute and chronic respiratory conditions [Citation22], and psychotic disorders [Citation23]. Interventional studies include findings that dry infrared heat WBH interventions [Citation1,Citation2] and hyperthermic bath interventions [Citation24] can reduce depression symptoms among individuals with major depressive disorder; reduce somatic complaints in mild depression [Citation25]; reduce pain in fibromyalgia [Citation26]; improve myocardial perfusion abnormalities in patients with chronic total occlusion of coronary arteries [Citation27]; decrease ventricular arrhythmias in individuals with chronic heart failure [Citation28]; and produce transient improvements in lung function in individuals with obstructive pulmonary disease [Citation29]. Taken together, these data suggest that WBH practices may hold promise as non-pharmacologic approaches to maintaining and/or improving both physical and mental health.

Notably, other WBH research that has assessed changes in depressive symptoms as secondary measures (as their focus was not on depression) have observed changes in depression symptoms. For example, researchers assessed depression symptoms one and five weeks after beginning to administer a multicomponent intervention focused on reducing toxins in the body. This multicomponent intervention included three weekly 45-min WBH sessions, and the researchers found that participants in the intervention condition (relative to those in the control condition) had lower depression scores at both assessment points [Citation30]. Another study included WBH for half of study participants receiving a multi-modal pain management treatment (including movement therapy, physical therapy, and other therapies) for severe fibromyalgia [Citation31]. Researchers found that on average, participants in both treatment arms (multi-modal treatment with versus without WBH) had similarly elevated depression scores. Analyses revealed that participants who received WBH sessions as part of their treatment (relative to those who did not) experienced a substantial reduction in depression symptoms. Thus, future work examining the impacts of WBH on various health outcomes could increase our understanding of changes in mental health parameters by including mental health assessment measures.

There are key factors that would improve the quality of both epidemiological and interventional WBH studies. Future observational studies of WBH practices would meaningfully build toward causal designs by more thoroughly characterizing WBH practices beyond simply amount of time per session and number of sessions per week. Such characterization might include the type of WBH (e.g., infrared, dry, or water-based heating), social milieu of WBH (e.g., individual versus group), motivations for WBH (e.g., maintaining mental health or improving mood when feeling down), and other aspects of WBH practices that may vary by culture or type of WBH. This would, in turn, benefit future interventional studies of WBH practices that could employ such data when developing standardized WBH protocols and measurement batteries.

A key next step in testing longer-term effects of WBH on depression symptoms is clarifying the amount of time needed in each WBH session; initial data suggest that slower heating to the target temperature is associated with larger reductions in depression symptoms [Citation4]. A second key step is ascertaining the WBH dose required to achieve antidepressant effects that go beyond six weeks. In this context, ‘dose’ may most aptly refer to frequency of WBH sessions per week or month. A third key next step is following patients for longer durations of time to establish optimal WBH session dosing for enhancing longer-term outcomes. Further steps include ascertaining the requisite core body temperature needed to achieve antidepressant effects. For example, WBH maintenance sessions that may be possible in home-use or other non-medical settings may sustain benefits achieved at an initial WBH dose (achieving 101.3 °F) conducted at an outpatient treatment setting. The WBH protocol we describe here uses a widely available sauna device that is approved for widespread use, is viable in outpatient healthcare settings, and is well positioned for research that advances these key steps.

Disclosure statement

Dr. Raison serves as a consultant for Usona Institute, Otsuka, Novartis, and Alfasigma. None of his consultant work for these entities is related to whole-body hyperthermia. All remaining authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Hanusch K-U, Janssen CH, Billheimer D, et al. Whole-body hyperthermia for the treatment of major depression: Associations with thermoregulatory cooling. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(7):802–804.

- Janssen CW, Lowry CA, Mehl MR, et al. Whole-body hyperthermia for the treatment of major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(8):789–795.

- Lowry C, Flux M, Raison C. Whole-body heating: an emerging therapeutic approach to treatment of major depressive disorder. Focus. 2018;16(3):259–265.

- Hanusch K-U, Janssen CW. The impact of whole-body hyperthermia interventions on mood and depression – are we ready for recommendations for clinical application? Int J Hyperthermia. 2019;36(1):573–581.

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-Item quick inventory of depressive symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(5):573–583.

- Cenik B, Cenik C, Snyder MP, et al. Plasma sterols and depressive symptom severity in a population-based cohort. Plos One. 2017;12(9):e0184382.

- Winthorst WH, Bos EH, Roest AM, et al. Seasonality of mood and affect in a large general population sample. Plos One. 2020;15(9):e0239033.

- Mans K, Kettner H, Erritzoe D, et al. Sustained, multifaceted improvements in mental well-being following psychedelic experiences in a prospective opportunity sample. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:1038.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097.

- Topp CW, Østergaard SD, Søndergaard S, et al. The WHO-5 Well-Being index: a systematic review of the literature. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(3):167–176.

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063–1070.

- World Health Organization. Health statistics and information systems: Depression. 2018. Mar 22 [cited 2019 Jul 9]; Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression.

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR* D report. AJP. 2006;163(11):1905–1917.

- Li X, Frye MA, Shelton RC. Review of pharmacological treatment in mood disorders and future directions for drug development. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):77–101.

- Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network Meta-analysis. Focus. 2018;16(4):420–429.

- Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, STAR*D Study Team, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: Implications for clinical practice. AJP. 2006;163(1):28–40.

- Laukkanen JA, Laukkanen T, Kunutsor SK. Cardiovascular and other health benefits of sauna bathing: a review of the evidence. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(8):1111–1121.

- Laukkanen T, Khan H, Zaccardi F, et al. Association between sauna bathing and fatal cardiovascular and all-cause mortality events. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):542–548.

- Kunutsor SK, Khan H, Zaccardi F, et al. Sauna bathing reduces the risk of stroke in Finnish men and women: a prospective cohort study. Neurology. 2018;90(22):e1937–e1944.

- Knekt P, Järvinen R, Rissanen H, et al. Does sauna bathing protect against dementia? Prev Med Rep. 2020;20:101221.

- Laukkanen T, Kunutsor S, Kauhanen J, et al. Sauna bathing is inversely associated with dementia and Alzheimer's disease in middle-aged Finnish men. Age Ageing. 2017;46(2):245–249.

- Kunutsor SK, Laukkanen T, Laukkanen JA. Sauna bathing reduces the risk of respiratory diseases: a long-term prospective cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32(12):1107–1111.

- Laukkanen T, Laukkanen JA, Kunutsor SK. Sauna bathing and risk of psychotic disorders: a prospective cohort study. Med Princ Pract. 2018;27(6):562–569.

- Naumann J, Grebe J, Kaifel S, et al. Effects of hyperthermic baths on depression, sleep and heart rate variability in patients with depressive disorder: a randomized clinical pilot trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(1):1–9.

- Masuda A, Nakazato M, Kihara T, et al. Repeated thermal therapy diminishes appetite loss and subjective complaints in mildly depressed patients. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(4):643–647.

- Matsushita K, Masuda A, Tei C. Efficacy of waon therapy for fibromyalgia. Intern Med. 2008;47(16):1473–1476.

- Sobajima M, Nozawa T, Ihori H, et al. Repeated sauna therapy improves myocardial perfusion in patients with chronically occluded coronary artery-related ischemia. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167(1):237–243.

- Kihara T, Biro S, Ikeda Y, et al. Effects of repeated sauna treatment on ventricular arrhythmias in patients with chronic heart failure. Circ J. 2004;68(12):1146–1151.

- Cox NJM, Oostendorp GM, Folgering HTM, et al. Van. Sauna to transiently improve pulmonary function in patients with obstructive lung disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1989;70(13):911–913.

- Hüppe M, Müller J, Schulze J, et al. Treatment of patients burdened with lipophilic toxicants: a randomized controlled trial. Act Nerv Super Rediviva. 2009;51(3–4):133–141.

- Romeyke T, Stummer H. Multi-Modal pain therapy of fibromyalgia syndrome with integration of systemic Whole-Body hyperthermia – effects on pain intensity and mental state: a Non-Randomised controlled study. J Musculoskelet Pain. 2014;22(4):341–355.

Appendix A

Inclusion Criteria

Male or pre-menopausal female volunteers aged 18–45

Able to understand the nature of the study and able to provide written informed consent prior to conduct of any study procedures

Able to communicate in English with study personnel

Able to lay supine for 2 hours in a sauna

BMI < =30

Waist size of < =40 inches for men or < =35 inches for women

Have a smartphone

If female, and sexually active with men, must agree to use non-hormonal birth control (e.g., barrier methods, partner with vasectomy, tubes tied, copper IUD)

Must have negative pregnancy test at Visit 2

Exclusion Criteria

Any history of or current mental health condition

Any current medical condition requiring medical treatment

Any history or current substance misuse/abuse

Regular use of any nicotine products, including cigarettes, vapes, chewing tobacco, or other forms of nicotine

Unable to refrain from psychoactive dietary or herbal products, including marijuana, in the 2 weeks prior to study participation

Breastfeeding or pregnant women, women intending to become pregnant within 6 months of the screening visit

Sexually active women of child bearing potential who are not using a medically accepted physical means of contraception (defined as non-hormone-based implant, condom, diaphragm, status-post tubal ligation, or partner with vasectomy)

Current use of hormone-based birth control, such as IUD or oral contraceptive

Needing to use of any medication that might impact thermoregulatory capacity within 5 days of the sauna session, including: stimulants, diuretics, barbiturates, beta-blockers, antipsychotic agents, anticholinergic agents or chronic use of antihistamines, aspirin (other than low-dose ASA for prophylactic purposes), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), systemic corticosteroids, cytokine antagonists

Current use of antidepressant medications (all classes) or use within the past 30 days

The following medications in these timeframes:

Antibiotics (past 60 days)

Pain medication (opioids) due to procedure, e.g., dental procedure (past 30 days)

Emergency contraception pill (past 60 days)

Benzodiazepines, e.g., procedure (past 30 days)

Use of any other medication that in the judgment of the PI would increase risk of study participation or introduce excessive variance into physiological or behavioral responses to WBH*

Known hypersensitivity to infrared heat exposure

Unwilling to refrain from sauna use outside of study procedures between first and final study visits

*Note: The medical monitor reviewed all medications reported by potential subjects. If the medication is determined to not have meaningful impacts on bodily thermoregulatory processes and to not interact with whole body heating, the subject was eligible to participate.