Abstract

Background

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) can reduce the length of hospital stay, incidence of surgery-related complications, and postoperative pain. We aimed to demonstrate the implementation of an ERAS pathway in the treatment of uterine fibroids with focused ultrasound ablation surgery (FUAS).

Materials and Methods

A retrospective data analysis was performed on clinical outcomes encompassing the following three phases: before ERAS (pre-ERAS), during adjustment of ERAS (interim-ERAS), and after the introduction of an ERAS program (post-ERAS). The purpose of describing the interim-ERAS was to provide references for the formulation of the program during the course of FUAS by describing the adjustment processes. Data from patients admitted to the hospital from September 2019 to December 2019 and April 2020 to November 2020 and who met the criteria for FUAS in the treatment of their uterine fibroids were examined. Length of stay, cost of surgery, postoperative pain score, utilization of postoperative analgesics, and incidence of postoperative adverse events were compared across the abovementioned three phases.

Results

Compared with the pre-phase, the cost of treatment and length of stay were reduced after the implementation of ERAS. The use of analgesics before leaving the operating room, as well as the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting, were also reduced.

Conclusion

The implementation of an ERAS protocol might benefit patients with uterine fibroids treated with FUAS in terms of requiring a shorter hospitalization period, lower costs, and reduced opioid use.

Introduction

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs are evidence-based care pathways designed to decrease the surgical stress response and maximize the potential for recovery [Citation1]. This procedure entails several pathways, including the use of multimodal analgesia to reduce opioid exposure, avoidance of prolonged fasting, encouragement of early mobility, and education of patients regarding the goals and expectations of surgery [Citation2–5]. ERAS may reportedly increase patient satisfaction, shorten hospital stays, reduce postoperative complications and treatment costs, and ultimately contribute to increased hospital productivity. ERAS programs have been implemented and evaluated in a variety of surgical populations, including colorectal, thoracic, complex urologic, joint replacement, and gynecologic surgical populations [Citation6–12].

Unlike other disciplines, inpatient gynecologic surgery has a wide range of complexities, as interventions vary from simple hysterectomy to advanced cytoreductive cancer surgery. Reviews of ERAS in both benign and gynecologic oncology surgery have shown that although protocol elements in the studies revealed benefits, there were marked dissimilarities among the protocols, which made it difficult to compare the results and draw conclusions [Citation13,Citation14]. Therefore, in 2016, the ERAS Society guidelines for gynecologic surgery were published [Citation15,Citation16], and guidelines for the optimal perioperative care of gynecologic oncology patients were updated in 2019 [Citation17,Citation18].

Although there is a special ERAS program in obstetrics and gynecology, the surgical method is usually laparoscopy. Focused ultrasound ablation surgery (FUAS), a noninvasive local thermal ablation technology, is a new modality for the treatment of solid tumors [Citation19–21]. The safety and efficacy of FUAS in the treatment of uterine fibroids have been widely acknowledged [Citation22]. The treatment of uterine fibroids with FUAS is a form of noninvasive micro-operation, which is different from laparoscopy. Laparoscopic surgery usually requires long hospital stay, with an average duration of 4.2 days [Citation23]. On the other hand, the average hospital stay for FUAS is only 3.6 days [Citation24].

Therefore, although the post-surgery complications were reported to be low for FUAS [Citation25], the current ERAS protocol for laparoscopy is not able to cover the characteristics related to the mechanisms of FUAS, which requires special perioperative strategies for recovery. For instance, when concentrating ultrasound waves at the desired location, with an external source of energy to induce thermal ablation of the tumor mass below the intact skin [Citation26], it is necessary to provide a satisfactory analgesic effect and balance keeping the patients conscious to avoid injuring the nerves. In addition, in the current postoperative management protocol, patients need to change from the traditional prone position to a more comfortable position and receive further postoperative health education. At the same time, due to the need for magnetic resonance imaging to localize the tumor before surgery, the cost of treatment with FUAS is higher than that with uterine artery embolization [Citation27,Citation28]. All these characteristics of FUAS call for a procedure-specific ERAS protocol for the broad implementation of this technique (See Supplementary tables).

The Chongqing HAIFU hospital is a gynecological hospital integrating treatment, rehabilitation, scientific research, and teaching with respect to benign uterine diseases. Since April 2020, a quality improvement project has been underway to establish a FUAS-specific ERAS protocol for the treatment of uterine fibroids with FUAS. In the present analysis, we aim to describe the process of ERAS establishment and to demonstrate the benefits of ERAS with respect to treatment cost, length of hospital stay (LOS), pain management, and postoperative adverse events.

Materials and methods

Procedure of establishing and implementing an ERAS protocol

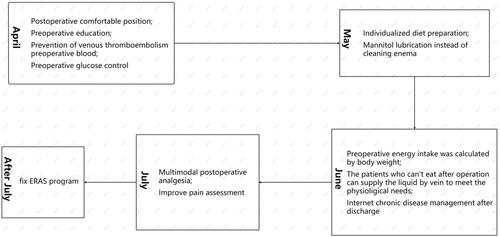

In April 2020, a multidisciplinary committee was formed, consisting of gynecologists specializing in the treatment of uterine fibroids with FUAS, anesthesiologists, nursing leaders, and medical research consultants, at Chongqing HAIFU hospital. Based on protocols developed by other gynecologic oncology surgical ERAS programs, we also reviewed the literature for ERAS protocols for Cesareans and developed a comprehensive, multidisciplinary ERAS protocol for the treatment of uterine leiomyoma with FUAS. The multidisciplinary committee adjusted the ERAS scheme according to patients’ feedback, through the expert opinion method. provides an overview of the key steps in our ERAS protocol, combining prior established practices with new ERAS measures, and lists the ERAS protocol before the measures for comparison.

Figure 1. Key steps for the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol for focused ultrasound ablation surgery (FUAS) for the treatment of uterine fibroids.

From April to July 2020, the feasibility of a draft protocol was tested on a small group of patients and modified in the interests of better acceptance and compliance. The protocol was finalized at the end of July 2020 and applied to all patients in the hospital from August 2020. The resulting consensus protocol focused on two main aspects of preoperative education and pain management.

Evaluation

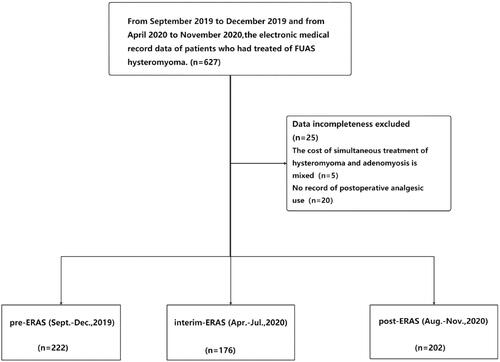

The current study is a retrospective analysis of the outcomes of patients with uterine fibroids related to FUAS. We retrospectively collected the data of patients in three phases: pre-ERAS (September–December 2019), interim-ERAS (April–July 2020), and post-ERAS (August–November 2020). The purpose of describing the interim-ERAS was to provide references for formulating ERAS schemes in the process of other FUAS treatments by describing the adjustment process in the construction of an ERAS scheme. shows the criteria for selection of patients for each phase of this study. The study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The analysis project was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of Chongqing HAIFU hospital (2021-006), while informed consent was waived since the data was collected from the records of clinical practice, rather than a research project.

Data

By reviewing the electronic medical records, we extracted basic information on the patient's age and body mass index (BMI), as well as the changes in the patient’s treatment costs and length of stay. We extracted data from intraoperative medication administration records, preoperative checklists, and nursing shift assessments recorded in the medical records including (1) the most severe intraoperative pain score, the pain score 15 min after drug withdrawal, and the continuous postoperative pain score on a 0–10 numerical rating scale to assess how well the pain was managed; (2) types and dosages of anesthetic drugs when patients left the operating room; (3) the side effects of postoperative analgesia on patients; (4) the number of times mechanical enema was performed; and (5) the incidence of postoperative nausea, vomiting, dizziness and discomfort in both lower limbs.

Statistical analysis

The main outcome measures were the total LOS, postoperative LOS, and treatment costs. We described normally distributed data as means and standard deviations and median and interquartile ranges (or range) for non-normally distributed data. Between-group differences of continuous variables were examined with the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data, while the Student t-test was utilized for normally distributed data. Categorical measures were analyzed with the χ2 test as indicated. Statistical significance was established at p < .05. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26.0; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

Results

Overall, 224 patients treated with FUAS before ERAS (September–December 2019), 179 patients undergoing ERAS implementation (April–July 2020), and 224 patients who underwent ERAS implementation (August–November 2020) were included in the current analysis. The distribution of age, BMI, diagnosis, maximum diameter of myoma, location of myoma, and preoperative anemia were similar among the three groups ().

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients.

After the implementation of ERAS, the median total LOS was 2.00 (IQR = 1.00) days, and the median postoperative stay was 1.00 (range = 0–3) day. This was lower than the duration of hospital admission before the implementation of ERAS (total LOS of pre-ERAS 3.00 (1.00) days, p = .000) and the postoperative LOS of pre-ERAS (1.00 (0–4) day, p = .003). After ERAS implementation, the median treatment cost was 22612.51¥ (IQR = 3189.23), which was lower than that of pre-ERAS (median = 23694.35¥, IQR = 3358.32, p = .000) and interim-ERAS (median = 23229.78¥, IQR = 2836.42, p = .019) ().

Table 2. Main outcome measures.

Postoperative analgesia in the interim-ERAS and pre-ERAS groups was managed with regular medications such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (diclofenac sodium, indomethacin, paracetamol, celecoxib, and ibuprofen) and tramadol. One dose of phloroglucinol 40 mg was administered to 6 patients in the interim-ERAS group. After commencing the ERAS program, postoperative nausea and vomiting occurred less frequently: 26.8% (48/179) patients in the interim-ERAS group compared to 16.6% (37/223) patients in the post-ERAS group (p = .013) ().

Table 3. Clinical outcomes before, during, and after ERAS.

After the implementation of ERAS, 10.8% (22/204) patients were prescribed analgesics before leaving the operating room. This was lower than that for patients in the interim-ERAS group (19.7%, 35/176, p = .015).

Through a comparison between the three periods of postoperative use of analgesics, it was found that analgesic use was lower in the pre-ERAS group (13.5%, 30/222) than in the interim-ERAS group (22.3%, 40/176) (p = .008), while analgesic use in the pre-ERAS group was lower than in the post-ERAS group (26.9%, 60/223) (p = .000). Furthermore, statistical analyses exhibited that the utilization rate of tramadol in the interim-ERAS group was 4.47% (8/179), which was lower than that in the pre-ERAS group (10.27%, 23/224) (p = .030). Moreover, the use of NSAIDs in the pre-ERAS group was 4.91% (11/224), which was lower than that in the post-ERAS group (21.08%, 47/223) (p = .000).

Discussion

This is the first report on the implementation of an ERAS program for patients with uterine fibroids treated with FUAS. Our analysis indicated that the implementation of ERAS could reduce the LOS and cost of treatment. After the implementation of ERAS, the duration of postoperative nausea, vomiting, and pain became less than that during interim-ERAS.

The ERAS protocol has now been applied in various surgical fields [Citation29,Citation30]. Studies have suggested that it has significantly improved postoperative LOS; overall morbidity, readmission, reoperation, and mortality rates; and cost [Citation31–33]. Wijk et al. in a prospective, international, multicenter analysis, demonstrated that high compliance to ERAS protocols not only reduces LOS after elective gynecological procedures but also improves the clinical outcomes of patients [Citation34]. The primary goals of the present study were to identify changes in the duration of hospitalization and treatment costs, which were found to be fewer after FUAS in the post-ERAS group than in the pre-ERAS group. In this study, the LOS associated with FUAS after the implementation of the ERAS program was lower than that of laparoscopy (4.2 ± 0.4 days) [Citation23] and uterine artery embolization (4.1 ± 1.2 days) [Citation35]. We anticipate that shorter hospitalization will facilitate recovery from these procedures and lead to an earlier return to usual life [Citation36].

The financial benefits to health providers associated with a shorter hospital stay are indisputable. In post-ERAS, the cost of FUAS was less than that in pre-ERAS. The average saving of costs was 1081.84¥ per patient undergoing FUAS within the ERAS protocol, supporting the concept that these protocols are also cost-effective. Since the LOS is the main determinant of hospitalization expenses, it is necessary to implement strategies that shorten the traditional LOS while maintaining quality [Citation37].

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is one of the most frequent side effects after anesthesia [Citation38], occurring in 30% of unselected patients and up to 70% of ‘high-risk’ patients during the 24 h after emergence [Citation39]. The incidence of PONV after FUAS treatment in the present study was 16.6% (37/233) when the ERAS program was implemented. This was higher than the 10.0% (4/40) [Citation33] in patients who had undergone a single hole laparoscopic hysterectomy. It is speculated that stimulation of the vagus nerve during FUAS treatment may increase its excitability or that the heat effect may cause intraoperative pain. Relevant data explaining the specific reasons need to be explored in future research.

Hydromorphone, an opioid, was administered as an analgesic before leaving the operating room. The use of hydromorphone in the post-ERAS group was less than that in the pre-ERAS group, suggesting that ERAS reduced the use of opioids. The number of NSAIDs used in the post-ERAS group was more than that in the pre-ERAS group, with the exception of tramadol. Although tramadol has rarely been administered as a primary drug of choice, a review of physician health program records illustrated that tramadol was the third most frequently mentioned opioid and that it exceeded the abuse liability of fentanyl, oxycodone, and hydromorphone [Citation40]. As with other opioids, the expansion of the worldwide availability of tramadol has resulted in an increase in abuse and diversion [Citation41]. Furthermore, the analgesic activity of tramadol has been reported to be higher than that of diclofenac in other pain conditions such as moderate to severe traumatic musculoskeletal pain [Citation42]. Therefore, the use of multimodal analgesia in ERAS and the reduction in the use of non-opioid central analgesics indicate that postoperative pain levels may be reduced with the implementation of ERAS.

An important fact that needs to be highlighted is that ERAS does not require additional technology and equipment. However, the introduction of the program necessitates cooperation and coordination between all the teams involved, as well as the willingness of patients [Citation43]. The efficiency and benefits of using the ERAS program depend primarily on the commitment and expertise of the staff. The process should be guided by the philosophy of patient-oriented nursing as this program increases the workload for nurses: it necessitates the provision of additional information to patients in the preoperative period and the assistance of patients with pain relief as soon as possible after surgery.

In interim-ERAS, the feedback outcomes of the ERAS program were evaluated and improved every two weeks. With the support of the expert team, it was found that the use of postoperative analgesics (including phloroglucinol, NSAIDs, tramadol, and hydromorphone) also had an impact on the duration of postoperative pain and the incidence of adverse reactions. This is consistent with the proposal of multimodal analgesia after gynecological surgery, as mentioned in the Chinese expert consensus on rapid rehabilitation after gynecological surgery (2019).

Limitations

Real-world data, clinical practice, and some variables were not collected regularly during the practice. This includes records of lower limb discomfort and intraoperative and postoperative pain score records, among others. Further well-designed studies to evaluate the ERAS in uterine fibroids patients treated with FUAS should be considered. Furthermore, the program was only implemented in one hospital and needs to be externally validated in other hospitals.

Conclusions

The implementation of the ERAS program improves patient comfort during treatment and reduces the postoperative pain level, the number of postoperative complications, the hospital stay duration, and treatment costs, all of which contribute to increased overall hospital productivity. This program consists of the introduction of a package of measures that have to be combined to provide the best therapeutic effect. Therefore, it is of great importance to implement an ERAS protocol for patients with uterine fibroids treated with FUAS.

Acknowledgments

We thank the surgeons, anesthetists, statistician, and nurses who helped implement the protocol.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78(5):606–617.

- Mcleod RS, Aarts MA, Chung F, et al. Development of an enhanced recovery after surgery guideline and implementation strategy based on the knowledge-to-action cycle. Ann Surg. 2015;262(6):1016–1025.

- Greco M, Capretti G, Beretta L, et al. Enhanced recovery program in colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Surg. 2014;38(6):1531–1541.

- Fearon KC, Ljungqvist O, Von Meyenfeldt M, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a consensus review of clinical care for patients undergoing colonic resection. Clin Nutr. 2005;24(3):466–477.

- Lassen K, Soop M, Nygren J, et al. Consensus review of optimal perioperative care in colorectal surgery: enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) group recommendations. Arch Surg. 2009;144(10):961–969.

- Liu VX, Rosas E, Hwang J, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery program implementation in 2 surgical populations in an integrated health care delivery system. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(7):e171032.

- Kehlet H. Fast-track colorectal surgery. Lancet. 2008;371(9615):791–793.

- Wind J, Polle SW, Fung Kon Jin PH, et al. Systematic review of enhanced recovery programmes in colonic surgery. Br J Surg. 2006;93(7):800–809.

- Meyer LA, Lasala J, Iniesta MD, et al. Effect of an enhanced recovery after surgery program on opioid use and patient-reported outcomes. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018;132(2):281–290.

- Mayor MA, Khandhar SJ, Chandy J, et al. Implementing a thoracic enhanced recovery with ambulation after surgery program: key aspects and challenges. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(Suppl 32):S3809–S3814.

- Carpenter MW. Gestational diabetes, pregnancy hypertension, and late vascular disease. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(Supplement_2):S246–S250.

- Zhu S, Qian W, Jiang C, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery for hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Postgrad Med J. 2017;93(1106):736–742.

- Nelson G, Kalogera E, Dowdy SC. Enhanced recovery pathways in gynecologic oncology. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;135(3):586–594.

- De Groot JJ, Ament SM, Maessen JM, et al. Enhanced recovery pathways in abdominal gynecologic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95(4):382–395.

- Nelson G, Altman AD, Nick A, et al. Guidelines for pre- and intra-operative care in gynecologic/oncology surgery: enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS(R)) society recommendations–part I. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;140(2):313–322.

- Nelson G, Altman AD, Nick A, et al. Guidelines for postoperative care in gynecologic/oncology surgery: enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS(R)) society recommendations–part II. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;140(2):323–332.

- Miralpeix E, Nick AM, Meyer LA, et al. A call for new standard of care in perioperative gynecologic oncology practice: impact of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;141(2):371–378.

- Nelson G, Bakkum-Gamez J, Kalogera E, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in gynecologic/oncology: enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) society recommendations-2019 update. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019;29(4):651–668.

- Al-Bataineh O, Jenne J, Huber P. Clinical and future applications of high intensity focused ultrasound in cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38(5):346–353.

- Wang W, Wang Y, Wang T, et al. Safety and efficacy of US-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound for treatment of submucosal fibroids. Eur Radiol. 2012;22(11):2553–2558.

- Xiong Y, Yue Y, Shui L, et al. Ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound (USgHIFU) ablation for the treatment of patients with adenomyosis and prior abdominal surgical scars: a retrospective study. Int J Hyperthermia. 2015;31(7):777–783.

- Liu H, Zhang J, Han ZY, et al. Effectiveness of ultrasound-guided percutaneous microwave ablation for symptomatic uterine fibroids: a multicentre study in China. Int J Hyperthermia. 2016;32(8):876–880.

- Xiong T-N-Z. Application of enhanced recovery after surgery concept in patients undergoing single hole laparoscopic myomectomy. Military Medical Journal of Southeast China. 2019;21:6.

- Li-Hong Jisth ALYE. IDEAL framework for surgical innovation technology assessment method. Chin Hosp Manag. 2019;39(11):32–35.

- Dueholm M. Minimally invasive treatment of adenomyosis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;51:119–137.

- Long LCJ, Xiong Y, et al. Efficacy of high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation for adenomyosis therapy and sexual life quality. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:11701–11707.

- Xianhong Z. Clinical effect of laparoscropic myomectomy or high-intensity focused ultrasound for uterine fibroid. Pract J Cancer. 2017;32:1186–1188.

- Qianling D, Zheng A, Wang W, et al. The prospective clinical controlled study of high intensity focused ultrasound and uterine artery embolization in the treatment of cesarean scar pregnancy. West China Med J. 2017;32:5.

- Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Evidence-based surgical care and the evolution of fast-track surgery. Ann Surg. 2008;248(2):189–198.

- Vlug MS, Wind J, Hollmann MW, et al. Laparoscopy in combination with fast track multimodal management is the best perioperative strategy in patients undergoing colonic surgery: a randomized clinical trial (LAFA-study). Ann Surg. 2011;254(6):868–875.

- Xiong J, Szatmary P, Huang W, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery program in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy: a PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Med. 2016;95(18):e3497.

- Williamsson C, Karlsson N, Sturesson C, et al. Impact of a fast-track surgery programme for pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 2015;102(9):1133–1141.

- Takagi K, Yoshida R, Yagi T, et al. Effect of an enhanced recovery after surgery protocol in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(1):174–181.

- Schneider S, Armbrust R, Spies C, et al. Prehabilitation programs and ERAS protocols in gynecological oncology: a comprehensive review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301(2):315–326.

- Guo Mei-Ling WX-J, He LI, et al. Analysis on cost effectiveness of uterine artery embolizationand laparoscopic myomectomy for hysteromyoma. Chin J Gen Pract. 2009;7:9.

- Tanaka R, Lee SW, Kawai M, et al. Protocol for enhanced recovery after surgery improves short-term outcomes for patients with gastric cancer: a randomized clinical trial. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20(5):861–871.

- Andreu-Ballester J-QA, Ballester F, Colomer-Rubio E, et al. Social and health characteristics of elderly patients with chronic and/or terminal diseases (PALET profile) attended in a short stay medical unit. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol. 2006;41:327–333.

- Eberhart LHJ, Högel J, Seeling W, et al. Evaluation of three risk scores to predict postoperative nausea and vomiting. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2000;44(4):480–488.

- Gan TJ. Postoperative nausea and vomiting-can it be eliminated? JAMA. 2002;287(10):1233–1236.

- Skipper GE, Fletcher C, Rocha-Judd R, et al. Tramadol abuse and dependence among physicians. JAMA. 2004;292(15):1818–1819.

- Miotto K, Cho AK, Khalil MA, et al. Trends in tramadol: pharmacology, metabolism, and misuse. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(1):44–51.

- Pagliara L, Tornago S, Metastasio J, et al. Tramadol compared with diclofenac in traumatic musculoskeletal pain. Curr Ther Res. 1997;58(8):473–480.

- Nikodemski T, Biskup A, Taszarek A, et al. Implementation of an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol in a gynaecology department – the follow-up at 1 year. Contemp Oncol. 2017;21(3):240–243.