Abstract

Objective

To investigate the effectiveness and safety of high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) ablation for patients with colorectal liver metastases (CRLMs) who were unsuitable for hepatectomy.

Methods

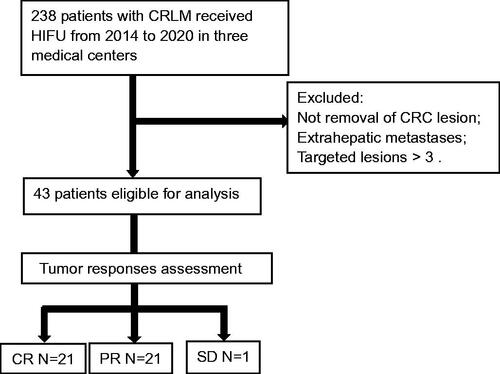

This is a multicenter retrospective study. 238 CRLM patients underwent ultrasound-guided HIFU (USgHIFU) ablation in three medical centers from October 2014 to December 2020. Patients who had complete colorectal cancer resection, but exhibited extra-hepatic metastasis were excluded from this study. HIFU ablation procedure was performed, and contrast-enhanced MR imaging and/or contrast-enhanced CT examinations were conducted and mRECIST was used for the assessment of tumor ablation effectiveness before and after treatment, and every 3 months thereafter. Adverse events and complications were recorded.

Results

43 CRML patients (27 male, 16 female, aged 29–82 years) were enrolled and underwent a USgHIFU ablation procedure. CR (complete response) was achieved in 21 patients, while PR (partial response) was observed in 21 patients and SD (stable disease) was achieved in one patient, respectively. The objective response rate was 97.7%. Median OS (overall survival) was estimated to be 31 months, and1-year and 18-month overall survival was 90.7% (39/43) and 72.1% (31/43), respectively. For CR and PR patients, the median OS was 35 months and 23 months, respectively (p = 0.00). The majority of adverse events were pain in 22 cases (51.2%) and local skin edema in 33 cases (76.7%). No severe adverse events or complications were reported and recorded.

Conclusions

USgHIFU ablation is a safe and effective treatment option for CRLM patients, especially for patients who are unsuitable for hepatectomy.

Introduction

Approximately one-third to one-half of patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) eventually develop liver metastases. While tumor resection is considered the first choice of treatment [Citation1,Citation2], the majority of colorectal liver metastases (CRLMs) are prohibitive for surgical resection due to the extensiveness of the lesions or/and the difficult locations of the metastatic lesions [Citation3]. Liver metastasis is the main cause of death in patients with colorectal cancer [Citation4]. The median survival time of untreated CRML patients is only 6.9 months, and the 5-year survival rate of non-resectable CRLM patients is less than 5% [Citation5,Citation6]. Local lesion ablative therapies, such as freezing, thermal, or chemical ablations, have become alternatives for CRLM treatment [Citation7]. Unfortunately, percutaneous penetration by electrodes or cryoprobes may result in bleeding and organ injuries. High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) ablation has been utilized as a noninvasive approach for the treatment of both primary and metastatic liver cancers since HIFU ablation-induced hyperthermia with the temperature rising to 60–100 °C at the targeted lesion leads to the induction of irreversible coagulative necrosis [Citation8–10]. HIFU had been applied for CRLM treatment in a single medical center cohort with promising results [Citation11]. However, CRLM patients in the reported study received systemic chemotherapy before or/and after HIFU treatment. Thus, it is hard to accurately assess the contribution of HIFU therapeutic efficacy to the overall survival outcomes. The objective response rate (ORR) is a valuable surrogate endpoint measure for survival in metastatic colorectal cancer [Citation12,Citation13]. In order to investigate the effectiveness and safety of ultrasound-guided HIFU (USgHIFU) ablation, we performed a retrospective study, in which CRLM patients without evidence of extrahepatic metastases who were unable to undergo hepatectomy received HIFU treatment. Tumor response, evaluated by mRECIST, was the primary endpoint of the analysis.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

This retrospective study was approved by the ethics committee at our respective institutes (Reference No. PJ-NBEY-KY-2019-071-01, SXH-IEC-2019-094, 20210003) and the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Patients

Two hundred and thirty-eight patients with CRLMs were treated with ultrasound-guided HIFU (USgHIFU) under conscious sedation or anesthesia in three medical institutions between October 2014 and December 2020. Written consent was obtained from all patients before USgHIFU treatment. The inclusion criteria were: confirmed CRLM, aged 18–85, no more than 3 liver metastases, unsuitable for surgical resection [Citation14], complete resection of the primary tumors and no evidence of extrahepatic metastasis. All of the patients with CRLM were comprehensively evaluated to be candidates for USgHIFU treatment by the multi-disciplinary teams of the respective hospitals. The exclusion criteria were: patients had received any other thermal ablation (radiofrequency, microwave), irreversible electroporation (IRL), and freezing ablation therapies before HIFU ablation. Data were retrospectively collected and analyzed.

Ultrasound-guided HIFU equipment and procedure

US-guided HIFU procedure was performed using a JC-200 HIFU system (Chongqing Haifu Medical Technology Co, Ltd., Chongqing, China), equipped with a diagnostic ultrasonic probe (Esaote MyLab70, Italy). It has a single 20 cm diameter focused piezoelectric ceramic ultrasound transducer with a focal length of 16.5 cm. The transducer was operated at the frequency of 1.0 MHz to generate the ultrasound energy. The focal region is 3 mm × 3 mm × 8 mm. The transducer can be moved smoothly in 6 directions (X-axis: left and right; Y-axis: cranial and caudal; Z-axis: up and down) by using computer control [Citation11]. The focused ultrasound target was deployed on a deep layer of the lesion. Based on the treatment plan, the target region of ablation needs to exceed the tumor’s margin by at least 5 mm. Sonication was repeated from the deep to shallow regions of the tumor to cover the entire tumor volume. The sonication power was 200–400 W and shot sonication time and cooling interval time were 1–3 s and 1–3 s, respectively. The initial acoustic power was 200 and 400 W under sedation/anesthesia and general anesthesia, respectively. For the patients under sedation/anesthesia, the released power will increase by 50 W each time up to 400 W according to their tolerance of the pain. The accumulative ablation energy was recorded. A tumor located at the liver dome might require a right-sided artificial pleural effusion to create the desirable acoustic path.

Evaluation of HIFU treatment effectiveness and safety

The therapeutic effectiveness of HIFU was evaluated with contrast-enhanced MRI or CT that were performed within 1 day and on day 30 after the procedure, and every 3 months thereafter. Tumor responses were assessed by the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST) [Citation15]: (1) Complete response (CR) is the disappearance of any intratumoral arterial enhancement in all target lesions; (2) Partial response (PR) is at least a 30% decrease in the sum of diameters of the viable (enhancement in the arterial phase) target lesion(s) taking as reference the baseline sum of the diameters of the target lesion(s); (3) Stable disease (SD) is any cases that do not qualify for either partial response or progressive disease; (4) Progressive disease (PD) is an increase of at least 20% in the sum of the diameters of the viable (enhancing) target lesion(s), taking as reference the smallest sum of the diameters of the viable (enhancing) target lesion(s) recorded before treatment. All data for the objective response rate (ORR, (CR + PR)/total × 100%) was analyzed retrospectively. Where applicable, any treatment-related abnormal MRI and/or CT findings, as well as the adverse effects, were examined in detail before and after the HIFU ablation. The overall survival (OS) was estimated as the secondary endpoint.

Data analysis and statistics

Data were described as the mean ± SD for normally distributed data or median with a range for non-normally distributed data. The student’s t-test or Chi-square test was employed for data analyses. Survival time was evaluated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the log-rank test was used to determine the statistical significance. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS software (SPSS 23; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

A total of 43 patients (27 male, 16 female), aged between 29 and 82 years were enrolled in this study. Hepatic metastases were present at the initial primary diagnosis (). Patients had received at least one time of chemotherapy after colorectal cancer resection, and the primary tumors were the colon cancers in 31 patients and the rectal cancers in 12 patients. 21 patients had one metastatic lesion; 8 and 14 patients had two and three metastatic lesions of hepatic metastases, respectively. The metastatic lesions were located in the right lobe in 13 patients, the left lobe in 11 patients and both lobes in 19 patients. The hepatic metastases with lesion size were <50 mm in 19 patients and ≥50 mm in 24 patients.

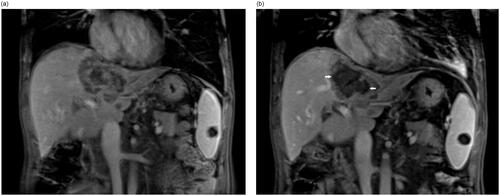

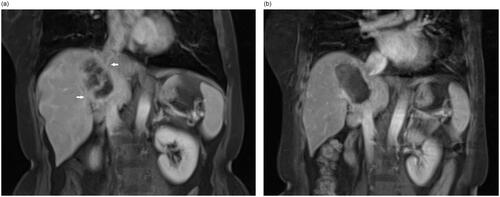

All 43 patients underwent technically successful USgHIFU for the treatment of hepatic metastases. After the procedure, CR was achieved in 21 patients (48.8%), PR in 21 patients (48.8%), and SD in 1 patient (2.3%) ( and ). The objective response rate (ORR) was 97.7%. Almost all patients (42/43) received adjuvant systematic treatment after HIFU except one older patient with leucocytopenia without other oncology treatments. The median follow-up for all patients was 48 months and no patient was lost to follow-up. Median OS was estimated to be 31 months, and1-year and 18-month overall survival rate was 90.7% (39/43) and 72.1% (31/43), respectively.

Figure 2. An example of partial response for HIFU ablation. The patient is a 54-year-old male with liver metastasis from rectal cancer. The contrast-enhanced MRI showed that pre-procedure hepatic lesions at segment VIII and segment I invaded the vena cava and hepatic vein (a) and the non-perfused area occupied more than 70% of the whole tumor (white arrow) after HIFU ablation (b).

Figure 3. An example of a complete response for HIFU ablation. The patient is a 54-year-old female with liver metastasis from colon cancer. The contrast-enhanced MRI showed that pre-procedure hepatic lesion located between 1st and 2nd porta (white arrow) (a) and complete non-perfused area (white arrow head) of the whole tumor after HIFU ablation (b).

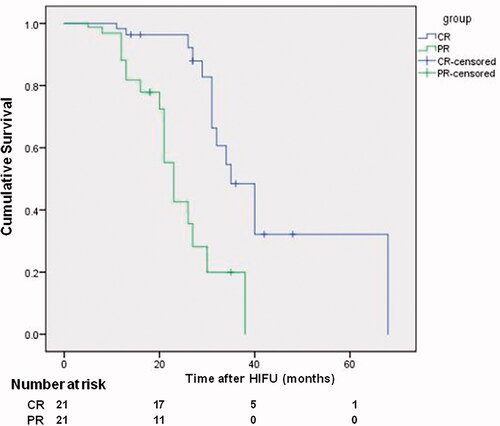

The average sonication time was 1788 ± 936 s and 1561 ± 585 s, average acoustic power was 319.2 ± 96.7 W and 279.2 ± 89.2 W, average acoustic energy was 602.7 ± 440.0 kJ and 404.3 ± 249.9 kJ, median survival time was 35 months and 23 months in the CR patients and PR patients, respectively (p = 0.00) (, ).

Figure 4. Kaplan–Meier survival curves for comparison between the CR and PR of patients with CRLM after USgHIFU treatment, and median survival was 35 months and 23 months in the CR patients and PR patients, respectively (p = 0.00).

Table 1. Characteristics of patients with CRLM treated by USgHIFUa.

Twenty-two patients (51.2%) complained of pain within 12 h after the HIFU procedure, and local subcutaneous edema was found in 33 cases (76.7%). These symptoms disappeared within 1–7 days and no medical interventions were required. Severe adverse events and complications were absent.

Discussion

Metastatic liver cancer, more prevalent than primary liver cancer, mainly arises from colorectal cancer. The 5-year survival rate of hepatectomy for CRLMs is only 30–50% because the survival length of this disease is shortened by the presence of liver metastases [Citation1]. For patients with unresectable colorectal cancer liver metastases, thermal ablation therapies have shown positive clinical outcomes, making radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or microwave ablation viable alternative therapies [Citation16]. However, CRLMs that are large in size, located at difficult locations, and adjacent to large vessels are prohibitive for the percutaneously penetrating needle thermos-ablation [Citation17]. Thus, there is an urgent need for new technologies to meet the clinical challenge of unresectable CRLMs.

HIFU utilizes ultrasound to penetrate tissues and focuses ultrasonic energy onto a targeted lesion inside the body to achieve tumor thermal ablation. As a non-invasive procedure, HIFU has been applied for the treatment of primary liver cancer for more than a decade, but there were very few studies on HIFU treatment of liver metastasis [Citation10,Citation11,Citation17]. Our previous study showed that HIFU treatment can achieve a good tumor response rate and improved long-term prognosis in CRLM patients without significant complications [Citation11]. The majority of patients with CRLM have unresectable lesions at the time of diagnosis and the median survival of these patients is less than one year [Citation18]. CRLM patients, who are prohibitive for surgical resection of liver metastases due to large size, location, or other comorbidities, typically live no longer than 18 months, and 5-year survival is unforeseeable [Citation2]. In this study, we show that HIFU treatment can significantly prolong the survival of unresectable CRLM patients. The median overall survival was estimated to be 31 months, and1-year and 18-month overall survival was 90.7% (39/43) and 72.1% (31/43), respectively.

HIFU-based combined regimens were employed in the prior study [Citation11]. CRLM patients often receive other therapies such as chemotherapy, radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or microwave ablation, and targeted immunotherapy apart from that of HIFU. Thus, the reported survival data cannot be easily ascribed to HIFU. The present study was performed to assess the efficacy of USgHIFU by using mRECIST tumor response evaluation as the primary endpoint and the overall survival (OS) as the second endpoint, although the latter is the gold standard.

Based on the treatment plan, HIFU sonication range was 5 mm larger than the margin of liver metastases. Moreover, thermal ablation often does not induce immediate shrinkage of the targeted tumor after procedures, in some circumstances, it may even increase the lesion size due to edema. The RECIST 1.1, based on lesion volume, is obviously unsuitable for the evaluation of HIFU effectiveness in CRLMs. Therefore, mRECIST was employed in this study. Both CR and PR were achieved in 42 patients while SD in one patient, and the objective response rate was 97.7% (42/43). The median survival time of CR patients was over 1.5 times longer than that of PR patients in this study (p < 0.001). This observation indicates that the tumor responses significantly impact the survival of CRLM patients. Thus, tumor response assessment by mRECIST can be used as the primary endpoint of HIFU efficacy assessment.

We show that tumor number, lesion size and sonication parameters were the key factors that influence HIFU treatment tumor response in CRLM. CR rate was significantly higher in patients with single live metastasis or size <50 mm, compared with patients with 2–3 lesions or tumor size ≥50 mm. We also show that CR patients had received more acoustic energy via higher acoustic power or/and longer sonication time than PR ones. However, extra attention should be paid because they might be at higher risk of abdominal wall edema or other procedure-related complications. Although the safety profile was good for this cohort of patients, additional sessions of HIFU procedure with at least two-week intervals are recommended for complete ablation of liver metastases, in order to reduce the incidence rate of local subcutaneous edema (76.7%).

It is reported that the median survival after curative-intent surgery of CRLM was 36 months [Citation19]. Thus, the median survival of 35 months in the patients with CR in the present study is comparable to the outcome of surgical resection. Theoretically, compared to hepatectomy, HIFU ablation-induced tumor necrosis may produce immunologic reactions, which may potentially benefit the survival of patients [Citation20]. Nevertheless, the survival time of HIFU ablation is under 5-year (42/43) with one exception (68-month) for this cohort. This is significantly lower than the reported survival time of resectable CRLM [Citation19]. Therefore, for the moment, USgHIFU ablation can be recommended for the treatment of unresectable CRLM.

According to NCCN guidelines, temperature ablation procedures (including RF, microwave and freezing, etc.) are the options for local treatment of CRLM unsuitable to surgical resection, among which RF ablation is recommended as the first choice [Citation21]. However, RF ablation is greatly limited in clinical practice for large metastatic lesions, or for the location of metastases nearby the heart because of electrical stimulation. Moreover, penetrating ablations such as RF have the higher risks of severe complications, such as bile duct injury or occlusion, vascular wall damage and thrombosis, liver abscess, gastrointestinal or gallbladder perforation. Ex-corporal delivery of HIFU and precise targeting have minimized the risk of injuries to the organ or to the surrounding tissues. There was no severe adverse event and complication in all 238 patients who underwent the HIFU procedure. Therefore, USgHIFU is a safer thermal ablation treatment worthy of consideration.

The limitations of this study are: (1) the survival time of HIFU, the secondary endpoint of the study, could not be evaluated independently. Since in addition to HIFU treatment, all patients received other treatments including chemotherapy or/and immunologic therapy. Perspective RCT studies are needed to confirm the efficacy of HIFU for the management of CRLM. (2) As a thermal ablation modality, the present cohort lacks the comparison between HIFU and RF or microwave ablation and merits future prospective studies.

In conclusion, this preliminary study demonstrated that for surgical unresectable CRLM patients who do not have extrahepatic metastases, HIFU is a new and alternative therapeutic option. HIFU treatment of CRLM is feasible, safe and effective.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Rees M, Tekkis PP, Welsh FK, et al. Evaluation of long-term survival after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multifactorial model of 929 patients. Ann Surg. 2008;247(1):125–135.

- Stewart CL, Warner S, Ito K, et al. Cytoreduction for colorectal metastases: liver, lung, peritoneum, lymph nodes, bone, brain. When does it palliate, prolong survival, and potentially cure? Curr Probl Surg. 2018;55(9):330–379.

- Primrose JN. Surgery for colorectal liver metastases. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(9):1313–1318.

- Foster JH. Treatment of metastatic disease of the liver: a skeptic’s view. Semin Liver Dis. 1984;4(2):170–179.

- Sharma S, Camci C, Jabbour N. Management of hepatic metastasis from colorectal cancers: an update. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15(6):570–580.

- Elias D, Youssef O, Sideris L, et al. Evolution of missing colorectal liver metastases following inductive chemotherapy and hepatectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2004;86(1):4–9.

- de Baere T, Tselikas L, Yevich S, et al. The role of image-guided therapy in the management of colorectal cancer metastatic desease. Eur J Cancer. 2017;75:231–242.

- Ji Y, Zhu J, Zhu L, et al. High-Intensity focused ultrasound ablation for unresectable primary and metastatic liver cancer: real-world research in a Chinese tertiary center with 275 cases. Front Oncol. 2020;10:519164.

- Wu F, Wang ZB, Chen WZ, et al. Extracorporeal high intensity focused ultrasound ablation in the treatment of patients with large hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11(12):1061–1069.

- Wu F, Wang ZB, Chen WZ, et al. Advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: treatment with high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation combined with transcatheter arterial embolization. Radiology. 2005;235(2):659–667.

- Yang T, Ng DM, Du N, et al. HIFU for the treatment of difficult colorectal liver metastases with unsuitable indications for resection and radiofrequency ablation: a phase I clinical trial. Surg Endosc. 2020;8:654.

- Johnson KR, Ringland C, Stokes BJ, et al. Response rate or time to progression as predictors of survival in trials of metastatic colorectal cancer or non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(9):741–746.

- Fleming TR. Objective response rate as a surrogate end point: a commentary. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):4845–4846.

- Akgül Ö, Çetinkaya E, Ersöz Ş, et al. Role of surgery in colorectal cancer liver metastases. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(20):6113–6122.

- Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30(1):52–60.

- Takahashi H, Berber E. Role of thermal ablation in the management of colorectal liver metastasis. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2020;9(1):49–58.

- Hompes D, Prevoo W, Ruers T. Radiofrequency ablation as a treatment tool for liver metastases of colorectal origin. Cancer Imaging. 2011;11:23–30.

- Nordlinger B, Sorbye H, Glimelius B, et al. Perioperative FOLFOX4 chemotherapy and surgery versus surgery alone for resectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer (EORTC 40983): long-term results of a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(12):1208–1215.

- de Jong MC, Pulitano C, Ribero D, et al. Rates and patterns of recurrence following curative intent surgery for colorectal liver metastasis: an international multi-institutional analysis of 1669 patients. Ann Surg. 2009 9;250(3):440–448.

- Zhang Y, Deng J, Feng J, et al. Enhancement of antitumor vaccine in ablated hepatocellular carcinoma by high-intensity focused ultrasound. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(28):3584–3591.

- Ajani JA, D’Amico TA, Almhanna K, et al. Gastric cancer, version 3.2016, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14(10):1286–1312.