Abstract

Objective

To investigate the clinical efficacy and safety of high intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) combined with ultrasound-guided suction curettage in patients with type I/II/III cesarean scar pregnancy (CSP).

Methods

A total of 153 patients with CSP were enrolled and classified according to the type of CSP. All of them were treated by HIFU combined with ultrasound-guided suction curettage. When active uterine bleeding was observed after curettage, a Foley balloon was used for hemostasis by compression. Baseline characteristics, technical parameters of HIFU, intraoperative blood loss in suction curettage, the time for serum β-HCG to return to normal levels, reproductive outcomes, and adverse effects were recorded and analyzed.

Results

152 patients completed one session of HIFU combined with suction curettage except one patient transferred to surgery. Total energy used for ablation and the time for serum β-HCG return to normal level in type II and III were significantly higher than type I (p < .05). The treatment time and sonication time of HIFU in type III were significantly longer than type I (p < .05). Vaginal bleeding after curettage and the rate of using Foley catheter balloon in type III was larger than type I and II.

Conclusions

HIFU combined with ultrasound-guided suction curettage is a safe and effective treatment option for patients with type I/II/III CSP and desire for fertility. Patients with type III CSP were more dependent on Foley catheter balloon compression therapy than the other two types after HIFU combined with curettage.

Introduction

Cesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) refers to the implantation of gestation sac in the previous cesarean section scar, which is a special and rare type of ectopic pregnancy [Citation1]. In recent years, the incidence of CSP has increased worldwide as a result of the high rate of cesarean section [Citation2]. CSP may be accompanied by severe complications, including massive hemorrhage, shock, uterine rupture, and life-saving hysterectomy [Citation3]. Thus, termination of pregnancy in the first trimester remains the standard management for CSP. In 2016, the Chinese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology published the latest Expert Opinion of Diagnosis and Treatment of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy (2016 Chinese Expert Opinion) which has incorporated the improved understanding of the clinical diagnosis and treatment of CSP. In the ‘2016 Chinese Expert Opinion’, according to the growth direction of gestational sac (GS) and the thickness of myometrium between GS and bladder, CSPs were divided into three types: (1) The type I is partially implanted in uterine scar, the thickness of myometrium between GS and bladder is more than 3 mm. (2) The type II is partially implanted in uterine scar, and the thickness of myometrium between GS and bladder is less than 3 mm. (3) In the type III, the GS was completely implanted in the myometrium of the uterine scar and protruded toward the bladder or forms an amorphous mass with rich vascularity at the cesarean scar and the thickness of myometrium between the gestational sac and the bladder became thinner ≤3 mm or even unobservable [Citation4]. To date, various treatments have become available, including medication, uterine artery embolization (UAE), curettage, surgery, and their combination [Citation5]. Hemostasis and fertility preservation are the main objectives in the management of CSP. However, there is still no worldwide consensus regarding the optimal treatment of CSP [Citation5]. Accurate early diagnosis and classification of CSP coupled with appropriate treatment can increase the success rate and reduce complications.

As a novel noninvasive treatment, HIFU ablation has been extensively used in the treatment of various solid tumors [Citation6,Citation7] and benign diseases, especially gynecological diseases, including uterine fibroids, adenomyosis, and placenta implantation [Citation8,Citation9]. In 2014, Huang et al. first reported their preliminary study on the application of HIFU combined with curettage to treat four patients with CSP [Citation10]. HIFU ablation combined with ultrasound-guided dilation and curettage in treating CSP is feasible and effective [Citation11], and has gained increasing recognition for the management of CSP. This is a minimally invasive procedure which can retain the organ and function integrity with no need of high-level surgical experience as in UAE and laparoscopic or hysteroscopic procedures.

Excessive intraoperative hemorrhage is associated with the specific type of CSP [Citation12]. Types II and III present a greater treatment challenge than type I [Citation4,Citation13]. According to previous reports, patients with exogenous CSP (uterine scar thickness <3 mm) and who underwent hysteroscopic surgery or curettage often suffered from uncontrollable bleeding, uterine perforation, and bladder injury during surgery, and the rate of secondary treatment after surgery was high [Citation14]. Laparoscopic cesarean scar resection is more suitable for type III patients and uterine repair can be performed simultaneously [Citation12,Citation15,Citation16]. To date, there is no universal agreement on the best treatment method for different types of CSP and there was a paucity of research on the association between the different types of CSP and the feasibility of HIFU combined with ultrasound-guided suction curettage in the management of CSP. At present, there is only one report on HIFU combined with suction curettage in the treatment of different types of scar pregnancy, however, no statistical analysis of different types of CSP has been performed yet [Citation17]. We thus undertook this study to investigate the clinical efficacy and safety of HIFU combined with ultrasound-guided suction curettage in patients with type I/II/III CSP, aimed to confirm whether the combined therapy is suitable for the different types of CSP.

Materials and methods

Patients

This retrospective study enrolled a total of 153 CSP patients who made the decision to terminate the pregnancy; and to choose HIFU followed by ultrasound-guided suction curettage as the procedure in Shenzhen Maternity & Child Healthcare Hospital, during April 2017 and October 2021. All patients in the study signed the written informed consent for the HIFU followed by suction curettage treatment. This retrospective study was approved by Institutional Review Board. The protocol number is SFYLS[2018]231. The requirement for informed consent was waived because the study was retrospective. The identities of the patients were maintained as confidential.

We conducted the management for CSP according to the guidance of 2016 Chinese Expert Opinion. Patients met the following inclusion criteria were included in the study: (1) a history of cesarean section delivery; (2) history of amenorrhea; (3) increased serum β-HCG level; (4) met the diagnostic criteria for CSP and were confirmed the type of CSP by three-dimensional B-mode ultrasound before surgery [Citation4]; (5) the days of amenorrhea ≤ 10 weeks for type I and II or the days of amenorrhea ≤ 8 weeks in type III or the days of amenorrhea ≤ 12 weeks for missed abortion. Patients with pelvic inflammatory disease, marked vaginal bleeding, abnormal or unstable vital signs, and a history of treatment for CSP before hospitalization were excluded from the study. The age, number of previous cesarean pregnancies, number of abortions, days of amenorrhea, interval since last cesarean delivery, the average diameter of GS, fetal heartbeat, and pretreatment serum β-HCG were analyzed by reviewing the medical records shown in . In our study, 43 patients (28.1%) meeting the criteria were classified as type I, and 89 (58.2%) were classified as type II. 21 patients (13.7%) were classified as type III. Comparison of the outcome was measured with the different types of CSP in patients.

Table 1. Comparison of baseline characteristics of CSP patients in three types.

HIFU treatment

Ultrasound-guided HIFU procedure was performed by 2 experienced gynecologists using the JC-200D Focused Ultrasound Tumor Therapeutic System (Chongqing Haifu Medical Tech, Chongqing, China), equipped with a 3.75-MHz diagnostic ultrasound probe (My-Lab70, Esaote, Italy) for real-time sonographic monitoring during the HIFU treatment. Each patient underwent bowel preparation for two days before the procedure, and the skin from the umbilicus to the upper margin of the pubic symphysis was prepared including shaving the hair, degreasing with 75% ethanol and degassing with degassed water. A catheter was inserted into the bladder to control its volume. The patient was positioned prone on the treatment table of the System with the abdominal wall in contact with degassed water over the transducer. The treatment was conducted under conscious sedation with fentanyl (1ųg/kg), followed by midazolam hydrochloride (20ųg/kg) every 5 min after fentanyl injection. The conscious sedation medicines were given every 20–40 min to keep a score of 4 or less on the Visual Analogue Scale/Score (VAS) for pain. The sagittal ultrasound scanning mode was chosen for both pretreatment planning and sonication. The focus was adjusted around the embedding area of the GS in the previous cesarean section scar and the bowel was pushed away from the acoustic pathway by a water balloon under ultrasonic monitoring. The treatment plan was made automatically, and the GS was divided into slices with a thickness of 3 mm; 350–400 W of acoustic power was used, and HIFU treatment was terminated when the color Doppler ultrasound showed a gray-scale change or the blood flow around the embedding area of the GS in the previous cesarean section scar disappeared or reduced).

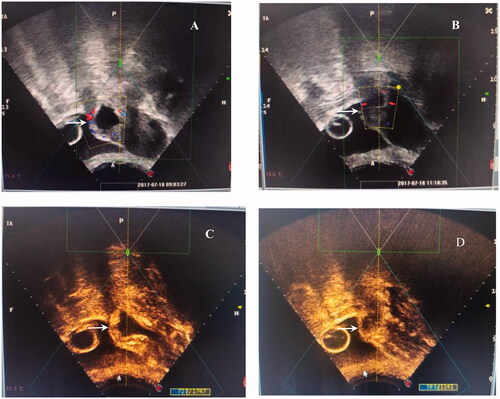

Figure 1. The signal of blood flow and contrast-enhanced ultrasound obtained from a patient with type III CSP treated with HIFU. A/C: abundant blood supply around the embedding area of the GS in the previous cesarean section scar (white arrow) before HIFU ablation; B/D: reduced blood supply around the embedding area of the GS in the previous cesarean section scar (white arrow) after HIFU ablation.

Ultrasound-guided suction curettage

Ultrasound-guided suction curettage under general anesthesia was performed on each patient one day after HIFU ablation by two experienced gynecologists. Patients were placed in the lithotomy position. Transabdominal ultrasound was used to determine uterine morphology and GS location, and also to guide the procedure. The depth of the uterus was measured before suction curettage. During the procedure, a 7.0 mm suction cannula with a vacuum pressure of 40 Pa was placed in the uterine isthmus. The cannula was carefully moved around the GS embedding area to detach the pregnancy tissues. Then, a curette was used to gently scrape the residue. Then, 20 units of oxytocin was injected into the cervix at the 12 o’clock position. If active uterine bleeding occurred after curettage, a Foley catheter balloon injected with normal saline would be used for hemostasis by compression. Under real-time transabdominal ultrasound guidance, the balloon was inflated slowly until it was visible in the uterine cavity and was then pulled out gently to the embedding area of CSP in the cesarean scar of uterus. When it was in place, the Foley catheter balloon was further inflated to place pressure on the embedding area of CSP in the cesarean scar of uterus to achieve the desired size and effect (). The amount of fluid required to inflate the balloon was observed under real-time ultrasound guidance and was between 20 and 30 ml, exerting pressure upon the bleeding vessel in the cesarean scar of uterus to stop the bleeding until full hemostasis was achieved. The end of Foley catheter was connected with a drainage bag and kept in place for about 24 h, which helped to calculate the amount of bleeding (). Patients were observed for 6 h after the Foley balloon was removed and discharged when they were hemodynamically stable with minimal bleeding or no bleeding at all. If uncontrolled vaginal bleeding occurred during or after the operation, UAE would be performed. If the UAE was not effective, further surgery was performed. Total intraoperative blood loss in suction curettage is equal to the sum of: a. blood volume in the negative pressure suction bottle; b. blood volume in the drainage bag; c. blood volume in the surgical towel under the buttock (blood weighs 1.05 g per cubic centimeter).

Follow-up observation

Patients were regularly followed up for at least half a year. Complications during and after HIFU treatment were closely observed and recorded, including lower abdominal pain, sciatic/buttock pain, hematuresis, skin injury and nerve injury. The serum β-HCG was monitored weekly until it returned to a normal level at gynecology and obstetrics clinic follow-ups. The time of menstrual recovery in addition to uterine ultrasonography were followed up and recorded. Patients were advised to go to the hospital in cases of severe abdominal pain, massive bleeding and no decreases in the level of β-HCG. Patients who had fertility needs could plan to conceive after three normal menstrual cycles and the reproductive-related outcomes were noted. Successful outcome was defined as successful removal of pregnancy tissue and a back-to-normal serum β-HCG level after curettage, and no needs for additional UAE or surgery treatment.

Statistical analysis

All of the data were analyzed using SPSS 23.0 software (IBM, USA). Continuous data were presented as mean ± SD for normal distribution and medians (P25-P75) for skewed distribution. Continuous data were compared by the analysis of variance, or the Kruskal-Wallis test as appropriate. The categorical data were presented as n (%) and compared using the chi-square Test or Fisher's exact test for inter-group analysis. Pairwise comparisons were corrected by Bonferroni's criteria. Spearson rank analysis was used for correlation analysis. All tests were two-tailed, and p < .05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Clinical characteristics of CSP patients

This study enrolled 153 patients with CSP. The baseline clinical characteristics of different types of CSP were shown in . Thickness of GS embedding myometrium was significantly lower in type III than that in type II (p < .05) and thickness of GS embedding myometrium in type II was significantly lower than that in type I (p < .05). Average diameter of the GS in type III was significantly larger than that in type I (p < .05). There was no significant difference in age, previous cesarean pregnancies, number of dilation and curettages, previous cesarean section times, interval since last cesarean delivery, days of amenorrhea, fetal cardiac activity, and pretreatment serum β-HCG levels among the three types (p > .05). Among this cohort of patients, 142 (92.8%) were diagnosed with a first CSP, 10 (6.5%) were diagnosed with a second CSP and 1 (0.7%) were diagnosed with a third CSP.

HIFU ablation results and safety evaluation

All patients received only one session of HIFU treatment. As shown in , compared with type I, total energy used for ablation in type II and III was significantly higher (p < .05). There was no significant difference between type II and type III (p > .05). Treatment time and sonication time in type III were significantly longer than type I (p < .05). No significant differences were observed among the three types in median treatment power and treatment intensity (p > .05).

Table 2. Comparison of HIFU treatment results for CSP patients in three types.

The common adverse events during HIFU were sciatic/buttock pain and treatment area pain. No significant differences were observed among the three groups in the score of pains (p > .05). The treatment procedure was well-tolerated by all the patients. The lower abdominal pain and sciatic/buttock pain disappeared one to two days after HIFU treatment without the requirement of any intervention. Three patients in this study had hematuresis during HIFU treatment because of the occurrence of air bubbles in the bladder. The symptoms of hematuria disappeared completely one to three days after HIFU treatment with interventions by indwelling the urinary catheter and intermittent infusion of iced normal saline into the bladder. And all these patients had no leg pain or burn injury during the treatment.

Evaluation of suction curettage and follow-up

All the patients received only one session of ultrasound-guided suction curettage with anesthesia one day after HIFU treatment. If active uterine bleeding occurred after curettage, Foley catheter balloon injected with normal saline would be used immediately for hemostasis by compression. showed that the median blood loss in ultrasound guided suction curettage procedure was 10 ml in type I, 10 ml in type II and 30 ml in type III. The blood loss in type III was significantly higher than that in type I and type II (p < .05). There was no significant difference in the blood loss between type I and type II (p > .05). The rate of using Foley catheter balloon was 47.6% in type III, which was significantly higher than that in type I (4.7%) (p < .05) and type II (15.7%) (p < .05). There was no significant difference in the use of Foley catheter balloon between type I and type II (p > .05). The bleeding was stopped effectively by the compression of Foley catheter balloon. One patient in type II had active bleeding again 1 h after balloon catheter compression. Under the guidance of ultrasound, the position of the balloon was readjusted, the volume of fluid was increased in the balloon, and active bleeding was controlled again quickly. The other patient in type II suffered from severe late-onset bleeding (about 200 ml) 36 h after the catheter was removed. A balloon catheter was inserted to her uterine cavity immediately for hemostasis by compression again. Finally, the active bleeding was controlled. 152 out of 153 patients completed one session of HIFU combined with suction curettage without serious adverse effects. Only one patient in type II had massive vaginal bleeding (500 ml) during curettage, the procedure was terminated and then a Foley catheter balloon was used for compression and vaginal bleeding was controlled. Due to the failure of the first-line treatment, this patient received a transabdominal lesionectomy after UAE was performed.

Table 3. Comparison of Ultrasound-guided suction curettage results and follow-up in three groups.

All the patients completed follow-up. We found that the average time for serum β-HCG to return to normal levels in type II and III was significantly longer than that in type I (p < .05). And there was no statistical difference observed in the duration of hospitalization and hospital expenses among the three types (p > .05). 3 patients (2 in type I and 1 in type II), because of the unsatisfactory decrease in serum β-HCG level, were readmitted to receive a 5-day regimen of intramuscular methotrexate (MTX; 20 mg/day) injections. No complications were found during chemotherapy. Serum β-HCG levels had decreased and return to normal levels finally. During follow-up, UAE, emergency surgical intervention, hysterectomy and massive blood transfusion were not required. The overall success rate was 99.3% in our study.

Subsequent pregnancy

All patients were followed up for more than six months. Twenty-three patients intended to conceive after the treatment. Eighteen out of 23 patients (78.3%) successfully conceived. Three patients carried unintended pregnancy. Seventeen patients had an intrauterine pregnancy and three patients had a recurrent CSP and one patient had a recurrent CSP followed by an intrauterine term pregnancy. Among these pregnancies, 18 (81.8%, 4 in type I and 11 in type II and 3 in type III) were intrauterine pregnancies and 4 (18.2%, 1 in type I and 3 in type II) were recurrent CSPs. No significant difference was observed among the three types in the recurrence rate of CSP (p > .05). All the cases of recurrent CSP were treated successfully with HIFU combined with ultrasound-guided suction curettage as a result of early diagnosis, and there was no excessive hemorrhage or other severe complications. Among the 18 patients with intrauterine pregnancy, 7 patients (1 in type I, 5 in type II and 1 in type III) underwent cesarean delivery at terms (≥37 weeks), 3 patients (2 in type I and 1 in type II) had a missed abortion, 3 patients (1 in type I and 2 in type II) chose induced abortion because of unintended pregnancy and the other 5 patients (3 in type II and 2 in type III) had an ongoing pregnancy. None of the women in our study had pregnancies complicated by placenta previa or placenta accreta or uterine rupture.

Correlation analysis

To further explore whether the type of CSP has an impact on HIFU treatment and ultrasound-guided suction curettage, we pooled patient data of three types together and carried out a correlation analysis to find relationships between the type of CSP and parameters of HIFU treatment and ultrasound-guided suction curettage. As shown in , we found that the type of CSP had a correlation with sonication time, treatment time, total energy used for ablation, blood loss during ultrasound-guided suction curettage, the use of Foley catheter balloon and time for serum β-HCG returned to normal level. The R values were 0.237, 0.198, 0.292, 0.331, 0.302 and 0.271, respectively (p < .05).

Table 4. Correlation between the type of CSP and parameters of HIFU treatment and ultrasound-guided-suction curettage (n = 153).

Discussion

The blood loss and effective removal of pregnancy tissue were evaluated as the main assessment criteria for the therapeutic efficacy of CSP. UAE followed by suction curettage has been reviewed as a key strategy with a high success rate for CSP in the past time [Citation18]. However, considering postoperative complications, such as postembolization syndrome, ovarian dysfunction and endometrial atrophy leading to intrauterine adhesions [Citation19–21], obstetricians and gynecologists are constantly searching for new treatment options for CSP. In recent years, HIFU combined with suction curettage has been used in the management of CSP, and the safety and effectiveness have been confirmed by many studies [Citation10,Citation22,Citation23].

During HIFU ablation, the ultrasound beams generated from the transducer can penetrate through abdominal skin, subcutaneous tissue and the bladder, then focused at the targeted tissue, and the temperature around the target increases to over 60 °C. HIFU ablation can cause coagulative necrosis of the embedded villus and damage small blood vessels with a diameter < 2 mm [Citation24] around the scar where the GS implanted, which is conductive to decrease the risk of hemorrhage in the later procedure of suction curettage. The effect of HIFU also helped to loosen the adhesion of the GS to the myometrium at the uterine scar, which was good for suction curettage [Citation11,Citation25,Citation26]. Hong et al. performed HIFU combined with suction curettage. While the effectiveness of HIFU combined with curettage was comparable to that of UAE combined with suction curettage, HIFU procedure resulted in fewer adverse effects than UAE [Citation27]. Compared with UAE, HIFU treatment is a noninvasive treatment and comfortable treatment, allowing patients to walk immediately after the treatment without lower limb immobilization. For these reasons, the patient acceptance of using HIFU before suction curettage is very high.

The CSP type is a risk factor for CSP patients with intraoperative hemorrhage [Citation11]. Types II and III present a greater treatment challenge than type I [Citation4,Citation13]. To reduce the risk of intraoperative bleeding in patients with type II and III CSP, UAE or temporary occlusion of the uterine artery is often used as a pretreatment, followed by curettage or removal of the pregnancy tissues. In regards to perform ultrasound-guided suction curettage following HIFU, the risk of heavy hemorrhaging decreased. The type III of CSP is still a risk factor for hemorrhage during HIFU combined with ultrasound-guided suction curettage. Yuan et al. performed HIFU combined with ultrasound-guided suction curettage, which is a safe and effective treatment strategy in the management of CSP type I and II, and the success rate was 100%. Nevertheless, four (25%) patients in type III CSP experienced late-onset severe bleeding several days after successful suction curettage and needed UAE or surgery to stop the bleeding [Citation17]. Our data showed the value of blood loss and the use of Foley catheter balloon for compression after HIFU followed by ultrasound-guided suction curettage treatment in type III were higher than type I and type II, which means type III CSP had more chance to experience active vaginal bleeding after HIFU combined with curettage and presented greater treatment challenge than the other two types. The reason is that except for the thinnest muscular layer at the scar in type III, the GS is completely implanted into the muscle layer of the uterine scar and protrudes toward the bladder, and the damage to the muscle layer is most serious which leads to the poorest contractions at the embedding area in the cesarean scar of uterus after suction curettage.

The use of an indwelling intrauterine Foley balloon catheter postoperatively has positive results to control bleeding complications in the management of CSP [Citation28,Citation29]. In our study, type III CSP had more chance to receive HIFU combined with Foley catheter balloon compression therapy followed by curettage than the other two types. The median intraoperative blood loss in type III was reduced to 30 ml because of the timely use of Foley catheter balloon compression therapy and accurate balloon placement under the ultrasound guidance. One hundred and fifty-two out of 153 patients completed one session of HIFU combined with suction curettage without serious adverse effects except one patient (0.65%) in type II experienced severe vaginal bleeding during curettage and needed UAE followed by surgery to expel the pregnancy tissue. One patient in type II experienced active bleeding again 1 h after balloon catheter compression and the bleeding was stopped effectively by readjusting the position of the balloon and increasing the volume of fluid in the balloon. Thus, the position of the balloon and the volume of fluid in the balloon are important factors for successful hemostasis in balloon compression. The other type II patient suffered from severe late-onset bleeding (36 h post-HIFU) when the catheter was removed. We speculated that the desquamation of thrombosis in microvessels at the site of a cesarean scar was the possible reason of late-onset bleeding and the bleeding was stopped effectively by reuse of Foley balloon for compression. As a supplement treatment followed by HIFU combined with curettage, Foley catheter balloon compression therapy is a safe and effective treatment option for patients with type I/II/III CSP. Patients with type III CSP were more dependent on Foley catheter balloon compression therapy than the other two types after HIFU combined with curettage.

We also evaluated the safety of HIFU combined with ultrasound-guided suction curettage treatment and the prognosis of patients in different types of CSP. No significant differences were observed between the three groups in the score of pains. The treatment procedure was well-tolerated by all the patients. During the follow-up period, we found that serum β-HCG levels of all the patients returned to normal levels, except three patients (two in type I and one in type II), because of an unsatisfactory decrease in serum β-HCG level, were readmitted to receive MTX treatment and then serum β-HCG declined to normal levels and none of the patients were required to transfer to surgery. Therefore, it was very important to regularly monitor whether serum β-HCG return to normal level in CSP. Incomplete removal of gestational tissue is a common complication of CSP. Since the GS usually implants in the myometrium and it is difficult to exercise the villi completely by curettage. In this study, the low incidence of unsatisfactory decrease in serum β-HCG level was mainly due to coagulated necrosis of the GS which implanted in the myometrium, and looseness of the adhesion of the GS to the myometrium at the uterine scar after HIFU treatment [Citation11,Citation24,Citation25]. Possible reasons for the unsatisfactory decrease in serum β-HCG are: the three patients had a history of curettage more than three times and had strong desire to preserve fertility; in order to avoid extensive damage to the endometrium, the time of suction curettage at the embedding area in the cesarean scar of uterus was relatively short. Therefore, the embedding area in the cesarean scar of uterus should be sucked as full as possible to avoid pregnancy residues in the scar under the premise of ensuring the safety of operation.

Of note, suction curettage cannot be used to treat CSP like how ordinary curettage is used, because ultrasonography of CSP displays a thinned or absent myometrium between the gestational sac and bladder. Thus, careful monitoring of curettage is a necessary step to avoid damaging the uterus and expel the gestational tissue completely. We performed ultrasound-guided suction curettage after HIFU treatment. Dynamic ultrasound can be used to ensure the complete removal of all gestational tissue and demonstrate the position of the balloon for hemostasis by compression. On the other hand, a static ultrasound can be used to measure residual scar thickness to prevent uterine perforation. In recent years, several studies were conducted for the treatment of CSP with HIFU combined with hysteroscopy-guided suction curettage and showed good safety and effectiveness [Citation22,Citation25]. Hysteroscopy can not only effectively treat CSP through a natural entrance, but also offer direct visualization to check whether there is residual trophoblastic tissue and remove these residual tissue through hysteroscopic management. And hemostasis can be achieved with electrocoagulation. Zhu et al. reported 53 patients of CSP were treated with HIFU followed by suction curettage under hysteroscopic guidance and 4 patients underwent a second session of suction curettage under hysteroscopic guidance [Citation23]. A total of 439 patients with cesarean scar pregnancy received hysteroscopic treatment and 28 patients were readmitted for further treatment because of an unsatisfactory decrease in serum β-hCG level [Citation30]. Thus, prospective comparative studies between hysteroscopy-guided suction curettage and ultrasound-guided suction curettage after HIFU for the treatment of CSP are needed.

We pay attention not only to the occurrence of severe complications, but also to the preservation of the patient’s fertility, i.e., the pregnancy outcome. In this study, the follow-up period was more than six months and 21 patients conceived. The HIFU treatment was noninvasive, in which the structural integrity of the uterus was preserved. Patients were able to schedule pregnancy three months after the menstrual recovery, which was particularly suitable for older patients who are trying to conceive [Citation11]. In this study, four (18.2%) had recurrent CSPs. No significant difference was observed among the three types in the recurrence rate of CSP. None of the patients in intrauterine pregnancy had pregnancies complicated by placenta previa or placenta accreta or uterine rupture. Chen et al. followed 135 cases of CSP patients who had a reproductive plan and reported recurrent CSP in 28 (20.74%) cases [Citation31], which was similar to our study. Therefore, once the patients conceive again, ultrasound examinations should be performed early as soon as possible to determine the implantation location of the GS for timely diagnosis and management of the recurrent CSP. All cases of recurrent CSP were treated successfully with HIFU combined with ultrasound-guided suction curettage as a result of early diagnosis in this study. This shows that repeated HIFU therapy is safe and effective in recurrent CSP who had received HIFU combined therapy.

There was a paucity of research on the correlation between the new classification of CSP and the effect and safety of HIFU combined with curettage for CSP. The strength of our study is that it was a relatively large retrospective cohort study and we performed the statistical analysis to investigate the clinical efficacy and safety of HIFU combined with ultrasound-guided suction curettage in patients with type I/II/III CSP. We have had extensive experience in diagnosing and treating patients with CSP by HIFU combined with ultrasound-guided suction curettage. However, there are some limitations to our study. First, it was a retrospective single-center study. Secondly, the inclusion criteria for days of amenorrhea differed among the three types of CSP. We only pay attention to type III CSP with live fetuses up to 8 weeks’ gestation and type I/II CSP with live fetuses up to 10 weeks’ gestation, and missed abortion up to 12 weeks’ gestation. Whether CSP with live fetus in late first-trimesters is suitable for HIFU combined with curettage still requires further study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, HIFU combined with ultrasound-guided suction curettage is a safe and effective treatment option for patients with type I/II/III CSP and who desire for fertility. Foley catheter balloon compression therapy is an effective supplement treatment followed by HIFU combined with curettage to increase the success rate of CSP treatment. Patients with type III CSP were more dependent on Foley catheter balloon compression therapy than the other two types after HIFU combined with curettage.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Reference

- Gonzalez N, Tulandi T. Cesarean scar pregnancy: a systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24(5):731–738.

- Shah JS, Nasab S, Papanna R, et al. Management and reproductive counseling in cervical, caesarean scar and interstitial ectopic pregnancies over 11 years: identifying the need for a modern management algorithm. Hum Reprod Open. 2019;2019(4):hoz028.

- Papillon-Smith J, Sobel ML, Niles KM, et al. Surgical management algorithm for caesarean scar pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;39(8):619–626.

- Family Planning Subgroup, Chinese Society of Obstetrics and Gynocology, Chinese Medical Association. Expert opinion of diagnosis and treatment of cesarean scar pregnancy (2016). Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2016;51:568–572.

- Birch Petersen K, Hoffmann E, Rifbjerg Larsen C, et al. Cesarean scar pregnancy: a systematic review of treatment studies. Fertil Steril. 2016;105(4):958–967.

- Orsi F, Arnone P, Chen W, et al. High intensity focused ultrasound ablation: a new therapeutic option for solid tumors. J Cancer Res Ther. 2010;6(4):414–420.

- Rodrigues DB, Stauffer PR, Vrba D, et al. Focused ultrasound for treatment of bone tumours. Int J Hyperthermia. 2015;31(3):260–271.

- Lee JS, Hong GY, Lee KH, et al. Safety and efficacy of ultrasound-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound treatment for uterine fibroids and adenomyosis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2019;45(12):3214–3221.

- Lee JS, Hong GY, Park BJ, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound combined with hysteroscopic resection to treat retained placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2016;59(5):421–425.

- Huang L, Du Y, Zhao C. High-intensity focused ultrasound combined with dilatation and curettage for cesarean scar pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;43(1):98–101.

- Zhang C, Zhang Y, He J, et al. Outcomes of subsequent pregnancies in patients following treatment of cesarean scar pregnancy with high intensity focused ultrasound followed by ultrasound-guided dilation and curettage. Int J Hyperth. 2019;36(1):926–931.

- Lin Y, Xiong C, Dong C, et al. Approaches in the treatment of cesarean scar pregnancy and risk factors for intraoperative hemorrhage: a retrospective study. Front Med. 2021;24(8):682368.

- Huang L, Zhao L, Shi H. Clinical efficacy of combined hysteroscopic and laparoscopic surgery and reversible ligation of the uterine artery for excision and repair of uterine scar in patients with type II and III cesarean scar pregnancy. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e924076.

- He Y, Wu X, Zhu Q, et al. Combined laparoscopy and hysteroscopy vs. uterine curettage in the uterine artery embolization-based management of cesarean scar pregnancy: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14:116.

- Fu LP. Therapeutic approach for the cesarean scar pregnancy. Medicine. 2018;97(18):e0476.

- Zhang X, Pang Y, Ma Y, et al. A comparison between laparoscopy and hysteroscopy approach in treatment of cesarean scar pregnancy. Medicine. 2020;99(43):e22845.

- Yuan Y, Pu D, Zhan P, et al. Focused ultrasound ablation surgery combined with ultrasound-guided suction curettage in the treatment and management of cesarean scar pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;258:168–173.

- Le A, Shan L, Xiao T, et al. Transvaginal surgical treatment of cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013;287(4):791–796.

- Hois EL, Hibbeln JF, Alonzo MJ, et al. Ectopic pregnancy in a cesarean section scar treated with intramuscular methotrexate and bilateral uterine artery embolization. J Clin Ultrasound. 2008;36(2):123–127.

- Kim CW, Shim HS, Jang H, et al. The effects of uterine artery embolization on ovarian reserve. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;206:172–176.

- Karlsen K, Hrobjartsson A, Korsholm M, et al. Fertility after uterine artery embolization of fibroids: a systematic review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018;297(1):13–25.

- Xiao J, Zhang S, Wang F, et al. Cesarean scar pregnancy: noninvasive and effective treatment with high-intensity focused ultrasound. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(4):e3511–e3517.

- Zhu X, Deng X, Wan Y, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound combined with suction curettage for the treatment of cesarean scar pregnancy. Medicine. 2015;94(18):e854.

- Wu F, Chen WZ, Bai J, et al. Tumor vessel destruction resulting from high-intensity focused ultrasound in patients with solid malignancies. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2002;28(4):535–542.

- Copelan A, Hartman J, Chehab M, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound: current status for image-guided therapy. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2015;32(4):398–415.

- Liu CN, Tang L, Sun Y, et al. Clinical outcome of high-intensity focused ultrasound as the preoperative management of cesarean scar pregnancy. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;59(3):387–391.

- Hong Y, Guo Q, Pu Y, et al. Outcome of high-intensity focused ultrasound and uterine artery embolization in the treatment and management of cesarean scar pregnancy a retrospective study. Medicine. 2017;96(30):e7687.

- Aslan M, Yavuzkir Ş. Suction curettage and Foley balloon as a first-line treatment option for caesarean scar pregnancy and reproductive outcomes. Int J Womens Health. 2021;2313:239–245.

- Lu YM, Guo YR, Zhou MY, et al. Indwelling intrauterine Foley balloon catheter for intraoperative and postoperative bleeding in cesarean scar pregnancy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(1):94–99.

- Tang Q, Qin Y, Zhou Q, et al. Hysteroscopic treatment and reproductive outcomes in cesarean scar pregnancy: experience at a single institution. Fertil Steril. 2021;116(6):1559–1566.

- Chen L, Xiao S, Zhu X, et al. Analysis of the reproductive outcome of patients with cesarean scar pregnancy treated by high-intensity focused ultrasound and uterine artery embolization: a retrospective cohort study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26(5):883–890.