Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to investigate the feasibility, efficacy, and safety of focused ultrasound (FUS) for the treatment of vulvar low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (VLSIL) with persistent symptoms.

Methods

This retrospective analysis included 24 VLSIL patients who underwent FUS treatment. At each follow-up visit, the clinical response was assessed including changes in symptoms and signs. In addition, the histological response was assessed based on the vulvar biopsy results of the 3rd follow-up. Clinical and histological response were assessed to elucidate the efficacy.

Results

A total of 22 patients completed follow-up and post-treatment pathological biopsies. After treatment, the clinical scores of itching decreased from 2.55 ± 0.51 to 0.77 ± 0.81 (p < 0.05). Furthermore, the clinical response rate and histological response rate were 86.4% and 81.8%, respectively. Only two cured patients indicated recurrence in the 3rd and 4th year during the follow-up period and achieved cure after re-treatment. In terms of adverse effects, only one patient developed ulcers after treatment, which healed after symptomatic anti-inflammatory treatment without scarring, and no other treatment complications were found in any patients. None of the patients developed a malignant transformation during the follow-up period.

Conclusion

This study revealed that FUS is feasible, effective, and safe for treating VLSIL patients with persistent symptoms, providing a new solution for the noninvasive treatment of symptomatic VLSIL.

1. Introduction

Vulvar squamous intraepithelial lesions (VSIL) is an intraepithelial disease that occurs in the female external genitalia and is associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection [Citation1,Citation2]. Previously, VSIL was referred to as vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) and was considered a precancerous lesion of the vulva, graded as VIN1–3 based on its pathologic features. In 2015, ISSVD (International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease) classification scheme [Citation3], reclassified VIN into three categories: (1) vulvar low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (VLSIL), (2) vulvar high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (VHSIL) associated with HPV infection, and (3) differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN) not associated with HPV infection. The ISSVD’s definition of VLSIL, unlike VHSIL, comprises both flat warts and transient HPV infections, which are not precancerous lesions and don’t require treatment when asymptomatic. Furthermore, VLSIL exhibits a high rate of spontaneous regression [Citation1,Citation3].

Recently, a German study [Citation4] indicated that 5–10% of chronic itching cases in women are caused by diseases related to genitalia, especially the vulva. For instance, VIN causes itching symptoms in the vulva. Moreover, a study [Citation5] reported that 20.8% and 8.3% of VLSIL patients experience depression and anxiety, respectively. Overall, these data indicate that symptomatic VLSIL significantly impacts a patient’s quality of life and mental status.

For symptomatic VLSIL patients, the expert consensus recommends imiquimod cream or laser treatments. However, prolonged use of imiquimod and repetitive laser treatments results in complications such as ulcers and scar formation [Citation6,Citation7]. In addition, prolonged and repeated treatments can also decrease patient compliance. A Chinese expert consensus, while exploring alternative treatment strategies included photodynamic therapy with 5-aminolevulinic acid as an indication for VLSIL [Citation8]. Whereas, a few studies have reported focused ultrasound (FUS) as a treatment option for VLSIL.

The FUS uses ultrasound’s favorable tissue penetration to focus energy on lesions at specific depths. Ultrasound energy produces heat, mechanical, and cavitation effects. These effects cause lesion tissue degeneration, necrosis, and replacement by normal healthy tissue in the surrounding area, while maintaining the integrity of the normal anatomical structure[Citation9]. Furthermore, because of its efficacy and safety, FUS has been widely used as a noninvasive treatment strategy for vulvar lichen simplex chronicus (VLSC) and vulvar lichen sclerosus (VLS) [Citation10]. A study revealed that FUS is effective, noninvasive, and safe in treating VIN in a mouse model [Citation9]. However, systematic clinical research on the feasibility, efficacy, and safety of FUS for the treatment of VLSIL is still lacking. This study aimed to investigate FUS’s safety, feasibility, and efficacy in symptomatic VLSIL patients, whose symptoms did not naturally subside for more than 6 to 12 months.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients

This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chongqing Haifu Hospital (approval number: HF2023-018), and the requirement of informed consent was waived. This study included female patients with VLSIL who received FUS treatment at HaiFu Hospital in Chongqing, China, from January 2012 to May 2023. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients who diagnosed with VLSIL according to biopsy pathology; (2) who had symptoms such as vulvar itching persisting for more than 6–12 months; (3) who had not received any other treatment for 3 months prior to FUS treatment. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients who had serious heart, liver, or kidney disease or uncontrolled diabetes; (2) who had acute genital inflammation, menstruation, gestation, or lactation; (3) who were diagnosed with VHSIL and dVIN; (4) who were unwilling for follow-up. The clinical data comprising age, course, menstruation, HPV infection, clinical symptoms, vulvar skin signs, pathological results of vulvar biopsy, treatment parameters, and adverse reactions were collected by reviewing electronic medical records and telephone follow-up.

2.2. Treatment

All patients were treated via the Seapostar Ultrasound Therapeutic Device (Model-CZF, Chongqing Haifu Medical Technology Co., Ltd., China) using the following parameters: power = 3.5 − 4.0 W, frequency = 10.4 MHz, and pulses = 1000 Hz. The treatment was performed by a professionally trained and skillful doctor. The treatment procedure was as follows: before the operation, the bladder was emptied, the patient was asked to lay in a lithotomy position, their skin was prepared, and anesthesia was intravenously administered using propofol and fentanyl. Then, a special coupling gel for ultrasound therapy was applied to the lesion area, the transducer was placed close to the skin, and repeated linear scans were performed at a speed of 5–10 mm/s, with the scanning range exceeding 5 mm outside the lesion area. The treatment was continued until the skin area became mildly congested and swollen, and the temperature reached 39–40 °C. The total treatment time was maintained at 15–40 min per patient. After treatment completion, the area was disinfected with iodine povidone, and a continuous patch of comfrey oil was applied, followed by a continuous cold compress of the vulva with a perineal cold pad for 6 h. On the first day of the post-operation, patients were given a sitz bath of 1:5000 potassium permanganate and were prescribed a hot and humid compress of 50% magnesium sulfate for 15 min twice a day. Topical burn cream was applied until the swelling had completely subsided.

2.3. Postoperative follow-up and evaluation of efficacy

Patients were followed up at 1, 3, and 6 months after the treatment, with a vulvar pathology biopsy performed at the third follow-up visit. At each follow-up visit [Citation11,Citation12], patients were assessed for symptoms (itching) and signs (lesion size). The degree of itching was ranked on a scale of 0 = no, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe itching. Clinical response was defined as a reduction in lesion size and itching. Furthermore, the clinical response was classified as complete clinical response (complete disappearance of lesions and itching), partial clinical response (≥ 30% reduction in lesion size and relief of itching), and no response (< 30% reduction in lesion size and no change in the degree of itching) [Citation13–15]. Moreover, the histological response defined as return to normal or absence of atypical cells that did not support the diagnosis of VLSIL. And it was classified as response and no response. Efficacy was assessed at 6 months after the treatment based on biopsy results and alterations in clinical signs and symptoms. In addition, the primary and secondary outcome measures were histological and clinical responses, respectively [Citation15].

2.4. Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS version 28.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The count data were expressed as percentages (%), and the normally distributed data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The normally distributed data was assessed via the Student’s t-test. p < 0.05 represented statistically significant differences.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics of patients

A total of 24 patients met the inclusion criteria and were selected for this study (). The patients’ ages ranged from 27 to 68 years (average = 48.2 ± 11.3 years). Furthermore, the disease duration ranged from 1 to 10 years (average = 3.8 ± 2.7 years), with a median of 3 years. A total of 18 patients had HPV infection in the cervix, with a positive rate of 75%. The HPV typing results indicated that the 3 most abundant genotypes were HPV11 (22.2%), HPV6 (16.7%), and HPV16 (16.7%).

Table 1. Characteristics of the enrolled patients with VLSIL.

3.2. Efficacy evaluation

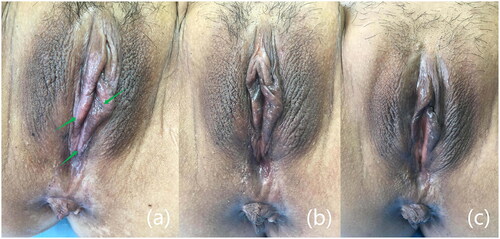

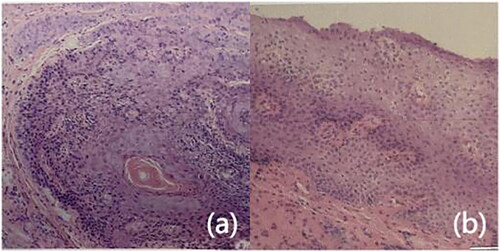

The 24 patients were followed up at 3rd month post-treatment, 21 patients (87.5%) showed a clinical response, while 3 (12.5%) showed no clinical response. Furthermore, during the 3rd follow-up, two patients were excluded as they did not undergo vulvar biopsy. The 22 patients completed post-treatment biopsy and were evaluated for efficacy. Of these, 12 patients (54.5%) indicated complete clinical response, 7 (31.8%) showed partial clinical response, and only 3 (13.6%) had no clinical response (). Compared to baseline, the clinical scores of itching decreased from 2.55 ± 0.51 to 0.77 ± 0.81 (p < 0.05). showed the changes in the clinical manifestations of the vulva after treatment. The histological response analysis revealed that 18 patients (81.8%) responded (), while 4 (18.2%) had no histological response.

Figure 1. Changes in clinical signs before and after treatment. (a) Before treatment (the green arrow indicated the lesion’s location), (b) after 1 month of treatment, and (c) after 6 months of treatment, the lesions disappeared and the skin color basically returned to normal.

Figure 2. Pathological biopsies before and after treatment. (a) Before treatment, epithelial thickening, with atypical cells, indicating low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification ×100), (b) after treatment, reduced epithelial thickening compared to pretreatment, without atypical cells (hematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification ×100).

Table 2. Evaluation of the efficacy of focused ultrasound therapy.

The 18 patients completed more than 1 year of follow-up. Of these, 2 biopsy-positive patients underwent re-treatment after 1 year, with subsequent pathology being normal. Whereas, the other two biopsy-positive patients refused to undergo re-treatment due to personal reasons. Moreover, two cured patients showed recurrence in the 3rd and 4th year after treatment and were subsequently cured. However, none of the patients developed malignancy at the follow-up cutoff.

3.3. Safety evaluation

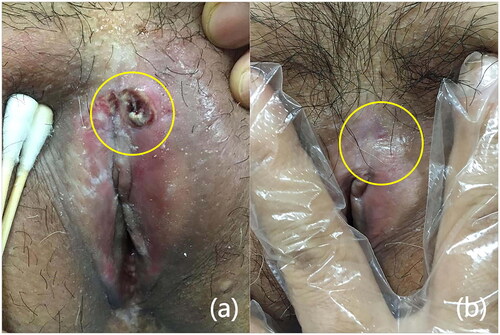

The mean treatment time was 1387.34 ± 331.42S, and the mean treatment dose was 5223.57 ± 1521.17 J. All patients had mild vulvar swelling and congestion at the time of treatment, which completely subsided 5—7 days after the treatment. Only one patient developed an ulcer after treatment (), which healed after symptomatic anti-inflammatory treatment. Moreover, no scarring, blisters, or coagulative necrosis were observed after any treatment ().

Figure 3. Side effects after FUS treatment and recovery from symptomatic treatment. (a) Ulcers appeared on the vulva after treatment, and the skin around the ulcers had become visibly red (yellow circle), (b) ulcers disappeared without scarring after one month of treatment (yellow circle).

Table 3. Adverse reactions after focused ultrasound treatment.

4. Discussion

VLSIL is a non-precancerous vulvar skin disease with multiple clinical signs and symptoms, where itching is the most common symptom in 35.92% of cases [Citation14]. To avoid overtreatment, this study included patients with itchy symptoms. As a noninvasive and reusable physiotherapy modality, FUS is effective in relieving vulvar itching and improving vulvar skin morphology [Citation16]. In terms of symptomatic relief, itching caused by vulvar disorders is associated with the activation of free nerve endings of unmyelinated C-fibers by specific mediators [Citation4]. Here, it was observed that the average itching score significantly decreased from 2.55 ± 0.51 to 0.77 ± 0.81 after treatment (p < 0.05). This improvement may be because FUS utilizes tissue penetration to promote the repair and regeneration of the dermis’s capillaries and small blood vessels as well as improve the nerve endings’ nutrition [Citation17].

In terms of clinical signs [Citation12,Citation18,Citation19], white or grey lesions may be related to keratin infiltration and loss or absence of melanin in the basal layer, which causes depigmentation. Red lesions may be related to inflammatory vasodilatation, immune response, or neovascularization. Furthermore, black lesions have been associated with ‘melanin incontinence’, where the expression of melanin increases, the excess melanin is excreted into the papillary layer of the dermis, where it is absorbed by melanophages. Due to the characteristics of HPV infection, lesions are often multicentric and multifocal, with most being < 1 cm and some being > 2 cm in size [Citation14,Citation20]. In this study, the VLSIL patients indicated both white lesions and multiple pigmentations. In terms of skin morphology of lesions, one study showed that the involved epithelial thicknesses in VIN1 was greater than the normal epithelium [Citation21], which may be related to epithelial cell hyperplasia. The involved epithelium was thicker in hairy sites than that in non-hairy sites, reaching 1.6 mm. In this study, the clinical response rate was 87.5% at 3rd month and 86.4% at 6th month. Jia et al. [Citation2] studied FUS for VIN2–3 and dVIN, and showed that 88.9% of patients experienced histologic and symptomatic regression at the 6th month after treatment. The FUS treatment depth can reach 4.0 mm [Citation22], which is significantly more than the VIN lesion’s thickness, and therefore FUS can be employed for the treatment of VIN lesions in the external genital region.

FUS can focus energy on lesion tissues and cells in the dermis or submucosa, warm the tissue and induce corresponding biological effects, damage lesion tissues and cells, promote healthy tissue’s repair and remodeling, align epidermal cells, and increase intracytoplasmic desmosomes to a certain extent, thereby improving the morphology and structure of lesion tissues [Citation9,Citation23]. The histological features of VLSIL are mainly hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, anisonucleosis, and koilocytosis [Citation24]. Of the 22 patients who completed biopsies after treatment, 18 (81.8%) showed histological clearance. In a retrospective study of photodynamic and surgical treatment of VSIL, photodynamic therapy for VLSIL has indicated a histologic regression rate of 75% [Citation25].

Furthermore, FUS therapy is an effective treatment modality for HPV regression [Citation26]. This study indicated 75% HPV positivity and 66.6% low-risk types rate, which is inconsistent with other literature and may be related to the small sample size [Citation20,Citation27–29]. This study, we could not discern whether HPV regression was affected by the treatment alone; therefore, the regression of HPV was not included here. In addition, the risk of progression to cancer is low, and the lesions usually regress after therapeutic intervention [Citation24,Citation30]. All patients did not develop malignancy while undergoing follow-up, consistent with the low malignancy rate of VLSIL. Moreover, the Japanese Society of Gynaecological Oncology (JSGO) suggests different treatment modalities for LSIL, HSIL, and dVIN due to their differences in the pathogenesis and malignant transformation rates. For VLSIL, invasive treatment should be avoided and regular follow-up should be performed [Citation31]. Therefore, unlike the therapeutic aim of VHSIL to interrupt disease progression and prevent malignant transformation, the VLSIL treatment is focused on relieving persistent symptoms and improving signs [Citation1]. Here, the clinical response rate was 86.4% and the histological response rate was 81.8%. Furthermore, FUS, as a noninvasive physiotherapy, is effective in improving the signs and symptoms of persistent symptomatic VLSIL, while ensuring the structural integrity of the vulva. However, further studies with large sample size and comparing FUS with photodynamic, imiquimod cream, or laser treatments are needed.

Regarding the safety of FUS, it was postulated that the damage to local tissues may gradually worsen with prolonged treatment time and increased doses. The mean treatment time was 1387.34 ± 331.42s, and the mean treatment dose was 5223.57 ± 1521.17 J. The mean FUS treatment dose was similar to that used FUS for treating VLS [Citation22]. In addition to transient mild vulvar swelling and congestion, ulceration was also observed after treatment in only one patient, which may be related to the patient’s poor skin elasticity, high treatment dose, and long treatment duration. Therefore, when administering FUS treatment, medical staff should maintain the speed of the treatment probe and strictly control the treatment time and dose to avoid excessive deposition of ultrasound energy on the epidermis, which may induce blisters or ulcers. Moreover, no patient indicated long-term complications after any treatments, demonstrating the safety of using FUS to treat VLSIL.

There are still certain limitations of this study. First, the small sample size of this study was due to the population of patients with persistent VLSIL symptoms, single-center data collection, and low prevalence disease. More reliable conclusions require a multicenter randomized prospective trial with increased sample size, which compares the efficacy of focused ultrasound therapy with other local treatments. Secondly, this study did not assess HPV elimination post-treatment. Due to the high natural regression rate of HPV infection in VLSIL patients and the limitations of retrospective studies, the potential impact of natural regression on the results could not be excluded.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, FUS, a widely employed technique for treating vulvar diseases such as VLS and VLSC, can also be used to treat VLSIL, effectively and safely. In particular, it offers a novel solution for the noninvasive treatment of symptomatic VLSIL.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author, CZ.L. The data are not publicly available because they contain information that can compromise the privacy of the research participants.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Li J, Suo L, Wu R, et al. Expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of vulvar squamous intraepithelial lesions. Chin J Clin Obst Gynecol. 2020;21(04):1–7. doi:10.13390/j.issn.1672-1861.2020.04.034.

- Jia Y, Wu J, Xu M, et al. Clinical responses to focused ultrasound applied to women with vulval intraepithelial neoplasia. J Ultrasound Med. 2014;33(11):1903–1908.

- Bornstein J, Bogliatto F, Haefner HK, et al. The 2015 international society for the study of vulvovaginal disease (ISSVD) terminology of vulvar squamous intraepithelial lesions. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(2):264–268.

- Woelber L, Prieske K, Mendling W, et al. Vulvar pruritus-causes, diagnosis and therapeutic approach. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;116(8):126–133.

- Bell SG, Kobernik EK, Haefner HK, et al. Association between vulvar squamous intraepithelial lesions and psychiatric illness. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2021;25(1):53–56.

- Fehr MK, Hornung R, Degen A, et al. Photodynamic therapy of vulvar and vaginal condyloma and intraepithelial neoplasia using topically applied 5-aminolevulinic acid. Lasers Surg Med. 2002;30(4):273–279.

- Tristram A, Hurt CN, Madden T, et al. Activity, safety, and feasibility of cidofovir and imiquimod for treatment of vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (RT³VIN): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):1361–1368. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(14)70456-5.PubMed PMID: 25304851; eng.

- Qiu L, Li J, Chen F, et al. Chinese expert consensus on the clinical applications of aminolevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy in female lower genital tract diseases (2022). Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2022;39:102993.

- Jia Y, Wu J, Chen L, et al. Focused ultrasound therapy for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia in a mice model. Am J Med Sci. 2013;346(4):303–307.

- Wu C, Zou M, Xiong Y, et al. Short- and long-term efficacy of focused ultrasound therapy for non-neoplastic epithelial disorders of the vulva. BJOG. 2017;124(Suppl. 3):87–92.

- Hasegawa M, Ishikawa O, Asano Y, et al. Diagnostic criteria, severity classification and guidelines of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Dermatol. 2018;45(8):891–897.

- Kesić V, Vieira-Baptista P, Stockdale CK. Early diagnostics of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(20):1822.

- van Seters M, van Beurden M, ten Kate FJ, et al. Treatment of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia with topical imiquimod. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1465–1473.

- Li J, Xi M, Chang S, et al. Analysis of clinical characteristics of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions of the vulva. J Pract Obst Gynecol. 2020;36(09):680–684.

- Yap J, Slade D, Goddard H, et al. Sinecatechins ointment as a potential novel treatment for usual type vulval intraepithelial neoplasia: a single-centre double-blind randomised control study. BJOG. 2021;128(6):1047–1055.

- Feng T, Wang L, Zhu D, et al. Factors influencing the clinical efficacy of high-intensity focused ultrasound in the treatment of non-neoplastic epithelial disorders of the vulva: a retrospective observational study. Int J Hyperthermia. 2021;38(1):1457–1461.

- Li C, Bian D, Chen W, et al. Focused ultrasound therapy of vulvar dystrophies: a feasibility study. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(5 Part 1):915–921.

- Kesic V. Colposcopy of the vulva, perineum and anal canal. CME J Gynecol Oncol. 2005;10(2):85.

- Heller DS. Pigmented vulvar lesions–a pathology review of lesions that are not melanoma. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17(3):320–325.

- Hoang LN, Park KJ, Soslow RA, et al. Squamous precursor lesions of the vulva: current classification and diagnostic challenges. Pathology. 2016;48(4):291–302.

- Xiao J, Chen Z, Xiao Y, et al. Vulvar squamous intraepithelial neoplasia epithelial thickness in hairy and non-hairy sites: a single center experience from China. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1254820.

- Jia R, Wu C, Tang X, et al. Comparison of the efficacy of focused ultrasound at different focal depths in treating vulvar lichen sclerosus. Int J Hyperthermia. 2023;40(1):2172220. doi:10.1080/02656736.2023.2172220.

- ter Haar G, Coussios C. High intensity focused ultrasound: physical principles and devices. Int J Hyperthermia. 2007;23(2):89–104. doi:10.1080/02656730601186138.

- Williams A, Syed S, Velangi S, et al. New directions in vulvar cancer pathology. Curr Oncol Rep. 2019;21(10):88.

- Zhang Y, Su Y, Tang Y, et al. Comparative study of topical 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy (5-ALA-PDT) and surgery for the treatment of high-grade vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2022;39:102958.

- Zeng H, Liu M, Xiao L, et al. Effectiveness and immune responses of focused ultrasound ablation for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Int J Hyperthermia. 2022;39(1):539–546.

- Srodon M, Stoler MH, Baber GB, et al. The distribution of low and high-risk HPV types in vulvar and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN and VaIN). Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30(12):1513–1518.

- De Vuyst H, Clifford GM, Nascimento MC, et al. Prevalence and type distribution of human papillomavirus in carcinoma and intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva, vagina and anus: a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(7):1626–1636.

- Zhang L, Xiao YP, Tao X, et al. Detection rate and clinical characteristics of vulvar squamous intraepithelial lesion. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2023;58(8):603–610.

- Logani S, Lu D, Quint WG, et al. Low-grade vulvar and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia: correlation of histologic features with human papillomavirus DNA detection and MIB-1 immunostaining. Mod Pathol. 2003;16(8):735–741.

- Saito T, Tabata T, Ikushima H, et al. Japan Society of Gynecologic Oncology guidelines 2015 for the treatment of vulvar cancer and vaginal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2018;23(2):201–234.