Abstract

The aim of the present study was to contribute knowledge about how adult L2 learners perceived their possibilities to use and develop the target language (Swedish) when formal language teaching was combined with placements. Situated in the context of Swedish for Immigrants (SFI), the study drew inspiration from action research and ethnographic methodology. A thematic analysis was conducted underpinned by the systemic-functional linguistic concepts of field, tenor and mode. The findings showed that the students highly valued interaction with L1 Swedish speakers outside of the classroom. Several of the students described rich opportunities to interact socially, which, however, also entailed anxiety about their status as L2 speakers. A few of the students reported accessing field-specific language and literacy practices that aligned with their current career goals. However, students with placements relating to kitchen, garage and warehouse work voiced feeling isolated and having little opportunity for social interaction. While students in the first of two course instances found it difficult to discuss and exemplify language they had learnt, a vocabulary assignment developed for the second course instance facilitated discussions about placement-related words and expressions. Implications for teaching are discussed, including using authentic examples of workplace discourse as preparation for placement visits.

The present study explores a method of language teaching for adult migrants in which formal language teaching was integrated with language learning opportunities at placements. The context of this study is the government-funded Swedish for Immigrants (SFI) program, which is designed for adults who need basic knowledge of Swedish to participate in different domains of language use (Skolverket Citation2022). It highlights a municipal SFI program which integrated formal language teaching with placements. While this teaching is a clear example of the current SFI paradigm as focused on efficient teaching for the work-life domain (e.g. Rosén and Babba-Gupta Citation2013, Lindberg and Sandwall Citation2017), it also mirrors the important aims in adult second-language education of individualising teaching and promoting communicative practices that bolster students’ agency outside the classroom (e.g. Baynham Citation2006, Yates and Major Citation2015, Lehtonen Citation2017, Reinders and Benson Citation2017). Currently, there is a lack of insight into how adults participating in basic language education experience efforts to bridge formal teaching and out-of-classroom language practices. This means that teachers and policymakers have little guidance from classroom research to develop language education programs that integrate workplace experiences. In such efforts, it is of utmost importance to consider how adult students experience the teaching and their opportunities to develop and use the target language in out-of-classroom contexts. The present study addresses this gap by exploring adult migrants’ perspectives on placements as a part of their basic language education. As shown in the next section, previous related research has predominantly focused on more advanced learners participating in professional programs.

More specifically, the aim of the present study is to contribute knowledge about how adult L2 learners perceive their possibilities to use and develop the target language (Swedish) when formal language teaching is combined with placements.

Previous research

In the Swedish context, Sandwall’s (Citation2013) dissertation was important in shedding light on SFI students’ language-learning opportunities on placements. Based on ethnographic data collected at the placements, she found that most of the students had very few opportunities to interact. The limiting factors she found included lack of tutoring, solitary work assignments and scarce opportunities for social interaction. Another important finding in Sandwall’s (Citation2013) work was that both teachers, students and coaches found it difficult to perceive and create meaningful connections between classroom activities and the placements. At the same time, they identified a disconnect between the slow ‘classroom Swedish’ and the challenging ‘ordinary Swedish’ the students would encounter on their placements.

In contrast, an Australian study involving a university workplace communication program (Riddiford and Joe Citation2010, Riddiford and Holmes Citation2015) showed the beneficial effects of combining sustained placements with explicit pragmatic instruction and course material based on authentic workplace communication. However, it is worth noting that, in contrast to the present study, the work of Riddiford et al. focused on skilled, well-educated migrants whose proficiency in the target language went beyond the basic level.

The perception of language use in the SFI program as far removed from language use outside the classroom is echoed in a more recent study conducted by Ahlgren and Rydell (Citation2020). Drawing on two different interview datasets (2004/2005 and 2015/2016), the authors showed that SFI students regarded classroom interaction with the teacher and other SFI students as insufficient for adequately developing their Swedish. At the same time, their opportunities to interact with Swedish L1 speakers outside the classroom were limited. The students viewed proficiency in Swedish as crucial to being accepted by L1 speakers. They expressed being under an evaluating gaze and were anxious about making mistakes (see also Rydell Citation2018).

Similar experiences have been reported in international research. For example, Major et al. (Citation2014) showed that participants in the Australian Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP) found it challenging to participate in informal workplace conversations. While most of the participants experienced a positive change over time, others reported feeling excluded and unable to follow conversations. In Duff et al.’s (Citation2002) study of Canadian migrants seeking careers in healthcare, participants expressed that their basic language education had not prepared them for using the language publicly. This led to speaker anxiety and a reluctance to engage in conversations. Through placements, the participants were able to develop social and professional linguistic capabilities, involving using language to cheer up, console and adapt to the needs of those they cared for.

Recent research into the ongoing teaching of SFI has not focused on teaching and student experiences related to placements. However, studies by Wedin and Norlund Shaswar (Citation2019, Citation2023) showed that students received few opportunities to engage in conversations resembling communicative practices outside the classroom. They noted that the students were silent most of the time, with few exceptions for the students to engage in extended exchanges, take on different speaking roles and use various speech acts to argue, ask questions and make jokes. Research on L2 learners’ opportunities to develop linguistic resources related to work-life has mostly focused on specific professional training programs that require a higher level of target language proficiency (e.g. Duff et al. Citation2002, Riddiford and Holmes Citation2015, Lehtonen Citation2017, Lum et al. Citation2018, Moanakwena Citation2021). The present study responds to the comparative lack of research on placement-integrated teaching and activities targeting different work-life domains in basic language education for adult migrants.

Theoretical underpinnings

In the present study, I follow the sociocultural tradition of viewing the use of language and literacies as socially situated (e.g. Baynham Citation2006). From this perspective, language learning cannot be reduced to a set of generic skills. Rather, it involves increasing the capacity to use language for purposeful participation in different social contexts. Although successful communication in different contexts, including classrooms and workplaces, often draws on multilingual repertoires and other semiotic systems (e.g. gestures), I primarily focused on experiences related to using the target language (Swedish) at the placements. In the thematic analyses, I drew inspiration from Systemic-Functional Linguistics (SFL, see Halliday and Mathiessen Citation2014). According to SFL, language use in specific situations is shaped by the variables of field, tenor and mode (Martin Citation2001, Halliday and Mathiessen Citation2014). Field refers to on-going activities and the specific domain of experience they relate to, while tenor concerns the relationship between participants with regards to status and degree of contact. Finally, mode describes the role of language in the situation and the medium used (spoken or written). While these and other SFL concepts are most frequently used for the purpose of detailed linguistic analysis, I employ them to thematise different contextual aspects of language use that the students referred to.

An important part of the field of discourse is the workplace-related vocabulary the students encounter, such as technical or specialised vocabulary related to the tasks performed (Duff et al. Citation2002, Lehtonen Citation2017, Moanakwena Citation2021). As shown in previous studies, students may also encounter colloquial language rarely included in the formal language teaching (Myles Citation2009, Major et al. Citation2014).

With respect to mode, the role of language can be presumed to differ depending on the nature of the work conducted. While some studies have shown that experiences at placements can substantially contribute to language learning (Duff et al. Citation2002, Riddiford and Holmes Citation2015), simple, repetitive and high-intensity work is likely to limit the learners’ opportunities to use and develop linguistic resources (Sandwall Citation2013, Strömmer Citation2016).

From the perspective of tenor, using language involves making contact with L1 speakers (Duff et al. Citation2002, Ahlgren and Rydell Citation2020) and engaging in small talk (Myles Citation2009, Major et al. Citation2014, Yates and Major Citation2015). Furthermore, an important relational aspect is that adult migrants often need to rely on L1 speakers’ willingness to accept them as legitimate language users (Rydell Citation2018), include them in the social discourse (Major et al. Citation2014) and accept the ‘communicative burden’ of contributing to a mutual understanding (Duff et al. Citation2002, Myles Citation2009).

Swedish for immigrants

The teaching in the present study followed an elective and placement-focused orientation course outside the regular SFI curriculum (see below).Footnote1 However, it targeted the same goals as the conventional SFI teaching focused on providing basic language proficiency in the Swedish language. The SFI program comprises four courses (A, B, C, D) and three tracks or study paths (1, 2, 3). Track 1 is intended for students with little or no formal schooling and comprises all the four courses. Track 2 targets students whose level of formal schooling does not correspond to the completion of Swedish upper secondary schooling (12 years in total). These students study courses B, C and D. Participants with more extensive formal schooling normally study track 3 which contains courses C and D.Footnote2 In the studied orientation course, the participants followed different tracks and studied courses C or D. Course C requires students to communicate in ordinary situations, while Course D demands communication in both informal and formal situations.Footnote3 While the early courses (A and B) target language use in the domain of everyday life and situations, both course C and course D expand this to cover four core domains: everyday life, civic life, education and work-life.

Method and material

In the following sections, I describe the design and methodological approach of the study, including information about the participants, data collection, ethical considerations and analytical procedure.

A ‘language practicum’ approach to SFI teaching

The present study highlights municipally-organised SFI teaching in a town located in southern Sweden. In this municipality, all SFI students choose one of three broadly defined branches: (1) education, healthcare and nursing, (2) foods, restaurant and service, or (3) industry, warehouse and logistics. This study focused on a recently developed elective orientation course that provided participants with placements in their chosen branch. The orientation course primarily targeted students taking course D and students with ‘good progression’ on course C. The primary aim of the course, as presented to both the students and to myself, was to provide the students with additional arenas for language development rather than immediate employment. Therefore, the course was often described in terms of ‘language practicum’ (språkpraktik), not to be confused with vocational placements. The course involved recruiters providing placements according to students’ goals and choice of branch. Most of the placement sites were public institutions (e.g. preschools, health centres) but there was also som private enterprises involved. During these placements, all students were assigned supervisors who were expected to support the students and communicate with the teacher.

The course lasted for 20 weeks. For 13 of these, the students were assigned a placement which they visited on Tuesdays and Wednesdays. On Mondays and Thursdays, the students had language lessons in which their placement assignments were presented, prepared and followed up.

Field access

Prior to the study, I was approached by the teacher and project leader who later participated in the study. They had knowledge about my previous research and inquired about my interest in engaging in on-going evaluation (in Swedish, följeforskning) of the municipality’s endeavour to integrate work placement with language learning goals in SFI teaching. They took inspiration from a pedagogical model suggested by Sandwall (Citation2013) building on increased transfer between classroom and placement contexts, for example by discussing the students' language learning experiences at the placements and bringing artefacts, such as texts, from the placement into the classroom. My role was formalised as part of a larger municipal project (undisclosed for reasons of confidentiality) aimed at promoting adult migrants’ opportunities to establish themselves in the labour market and in society at large.

A practice-based methodological approach

The present article presents the first results of the research process running parallel to my involvement in the ongoing evaluation described above. Working together with an SFI teacher and a project leader from the municipal labour department, I employed an interpretative, practice-based methodology inspired by ethnography (Fangen Citation2005) and collegial action research (Willis and Edwards Citation2014). Our shared goal was that the placement should promote opportunities for language development across different domains and be integrated with formal teaching.

My involvement in the study was shaped by both a research interest in second language teaching and previous experience as an adult educator in the SFI program. At the beginning of each course instance, it was important to clarify my researcher role to the students. In this case, it aligned with the role of a ‘focused witness’ with an overt agenda for the research (Tracy Citation2020, p. 133). Together with the teacher and the project leader, I, therefore, explained that I would conduct research specifically on teaching activities connected to their placements in the orientation course with a focus on their opportunities to use and develop their Swedish. I also stressed that it was important for the research that they shared both positive and negative experiences.

Furthermore, we informed the students that I had worked as an SFI teacher and would arrange communicative activities as part of the research. Since I attended most of the lessons in the orientation course, I experienced that the students quite quickly became accustomed to my presence and participation in the classroom. At the same time, the teacher and the project leader often referred to my role as a researcher. Since students were invited to a municipally organised conference about SFI teaching, they also experienced my sharing preliminary findings of the study.

The participant teacher was certified for teaching in Swedish as a second language, French and English. She had 15 years of professional teaching experience, predominantly in adult education. The project leader worked closely with the teacher and, at times, with me as the researcher.

In total, 20 students participated in the study. They all had chosen to enlist in the course. Many, but not all, belonged to the teacher’s regular group of SFI students. Since some of the students dropped out of the course for different reasons, the number of students participating in the activities highlighted in the present article was 14. They are presented in (CI = course instance).

Table 1. Students participating in the study.

The teacher aided me in collecting information about the study path and course they studied in the regular SFI teaching, as well as general information about their study background (as self-reported by the students). The Track 1 students had 0–6 years of prior schooling, while Track 2 students had reported 8–14 years. The Track 3 students possessed 1–5 years of university education which, however, often had no bearing on their choice of branch. The most common first languages in the municipal SFI program were Arabic, Persian-Dari, French and Somali. According to the teacher, the students’ ages ranged between 20 and 67. Most of them were assumed to have lived in Swedish for 1–5 years, but in some cases significantly longer. As the students following study path 1 had already reached course D, it can be assumed that they had resided in Sweden for a relatively long time.

Ethical considerations

The study followed the Swedish Research Council’s guidelines (Citation2017) for good conduct in research. Prior to the study, I sought the participants’ informed consent. The students were informed both orally and in writing about the purpose of the study (see also previous section), the voluntary nature of participation and the right to cease participation. The written information was reviewed together with the teacher and adapted to the expected language level of the students. The students had filled in multiple consent forms before as part of their involvement in the municipal project, but it was necessary to emphasise that the current consent concerned research. In some cases, we felt that it was necessary to provide additional explanations in other languages to secure informed consent. These were provided by the teachers or tutors proficient in the students’ first languages. One student declined participation. I adjusted my data collection by pausing recordings during presentations and focusing on peer-group constellations in which the non-consenting student did not participate.

Furthermore, the collection of data was guided by data minimisation expectations of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): to only collect the information deemed as necessary to answer the research questions (Regulation Citation2016/679). In particular, the study was designed to prevent the collection of information which, by implication, could be used to infer the participants’ ethnicity or other data considered sensitive according to GDPR and Swedish legislation (SFS Citation2003:460). It followed that I did not collect information about individual students’ home countries or first languages.

Data collection

From the ethnographic perspective, I spent most of the language lessons as a focused witness (Tracy Citation2020), documenting the teaching and the students’ presentations of assignments related to their work placement by means of audio recordings and field notes. During the lessons, I produced raw records of events and conversations which I later transformed into formal notes with some theoretically informed reflections (see Tracy Citation2020, p. 138–141). I also conducted a few individual interviews with the students to gain additional insight into how they perceived their work placement.

As part of the practice-based research, I designed communicative activities together with the teacher and moderated the resulting discussions. My role differed in some respects between the two course instances. In the first course instance, the practice tasks were predesigned by the teacher. In the second instance, I had a more proactive role in co-designing some assignments based on insights from the previous instance. The most substantial change was the introduction of an assignment focused on vocabulary to facilitate meaningful transfer between the placements and formal language teaching. It was based on the assumption that learning experiences inside and outside the classroom can mutually benefit each other (e.g. Sandwall Citation2013, Lai et al. Citation2015).

The data used in the present article primarily consists of transcribed audio recordings of communicative lesson activities in which the students talked about their opportunities to use the target language during their placement. In most of the activities, the students’ objective was to share experiences from their placements. This data was further supported by three transcribed semi-structured interviews with students.Footnote4 These interviews covered similar themes to the communicative activities but enabled more individually tailored questions and further probing. Since these interviews entailed the students’ interacting in Swedish to their best ability on topics similar to the ones in the group activities, these are also considered part of the teaching.

The total transcribed material constitutes 103 000 words. The examples presented in the findings were translated from Swedish to English by me. When possible, translations retain features of learner language to reflect the students' language use. The number of documented lessons during the placement period was 22. They were evenly distributed between the two course instances and typically lasted 90 minutes. However, the present analysis only draws on activities in which the students’ opportunities to use the target language occurred as a topic of classroom conversation. An overview of these activities is presented in (CI: course instance, N: lesson number in sequence).

Table 2. Overview of documented activities.

In the whole-class activities, the data drawn upon was typically generated during discussions following students’ individual presentations of their placement assignments. These were not designed to elicit the students’ views on their opportunities to use Swedish. However, on several occasions, the teacher asked questions pertaining to this, either in the form of follow-up questions to the students’ presentations or more general questions to the student cohort at the start or end of the lesson. Some students also included information about their language use in their presentations.

In the evaluation activity (2:11), I moderated a peer group discussion in one of two groups. The other was moderated by the project leader. This second discussion was not recorded but briefly reported orally. In hindsight, the design would have benefitted from ensuring documentation of both groups. To partly remedy this, I consulted written evaluations from the students delivered to the teacher in close conjunction with the oral evaluation. However, unlike studies focused on more advanced L2 learners (e.g. Myles Citation2009, Lehtonen Citation2017), I generally did not rely on samples of students’ writing.

Part of the reason for describing the data collection in terms of communicative activities is that the students expressed themselves in a language they study at a basic level. Although the interviews enabled interactional support, the conditions can be considered suboptimal for collecting in-depth and accurate answers. However, an interview-based design involving interpreters would have run counter to the practice-oriented focus on a teaching practice supposed to create opportunities for the students to develop and express themselves in the target language. Moreover, the use of Swedish enabled me to establish a rapport with the students as an important relation-building aspect of the fieldwork (Anderson-Levitt Citation2006). Aside from receiving interactional support from me and their peers, the students were encouraged to express meanings in other languages known to me, primarily English. This was taken up by one student who was rarely heard interacting in Swedish.

Building on my previous experience as an SFI teacher, I strove to adapt all questions and topics to the expected proficiency level of the students (SFI D or late stages of SFI C). For increased validity, I discussed the design and wording of questions with the teacher. In phrasing the questions, I also followed common interview procedures to stimulate expansive answers (Brenner Citation2006), such as posing open-ended questions (or yes/no questions with appropriate follow-ups) and probing questions (Tracy Citation2020). This often involved asking the students to provide examples.

Data analysis

The analysis drew inspiration from thematic content analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). The approach was appropriate since it allows interplay with different theoretical perspectives to develop and probe relevant themes, in this case, the SFL concepts field, tenor and mode (Martin Citation2001, Halliday and Mathiessen Citation2014). In familiarising myself with the data (Braun and Clarke Citation2006), I marked activities and interactions focused on the students’ experiences at their placements. I initially developed two broad themes reflecting positive and negative experiences.

In the further steps of the analysis, I identified sub-themes connected to previous research and different aspects of tenor, field and mode. This analysis involved abductive movements between the data and theoretical underpinnings (Timmermans and Tavory Citation2012) and enabled additional insight into the students’ experiences at the placement, for example, how language use was (or was not) part of different activities, the kind of relationships they negotiated when using language and their use of different modes (primarily speaking and writing).

The finalised themes are presented and placed in relation to the register variables they were primarily associated with in .

Table 3. Thematic analysis related to SFL register variables.

Findings

In this section, I present the main findings of how the adult L2 learners perceived their possibilities to use and develop the target language (Swedish) when formal language teaching is combined with placements.

Speaking and listening to Swedish at placements

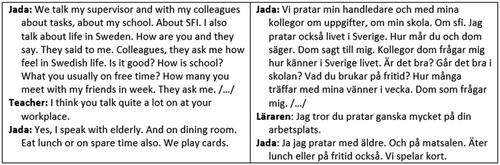

A salient topic of conversation in the classroom was the students’ opportunities to speak and listen to Swedish at their placement. This draws attention to the mode of discourse and more specifically the role of oral language in the activities they took part in. In the first course instance, the students had assignments related to presenting workplace tasks and working time. Some students having their placements at nursing homes and youth recreation centres described speaking Swedish a lot, as exemplified in .Footnote5

This student, Jada, had her placement at a nursing home and expressed being frequently engaged in conversation by her colleagues. The simple questions on everyday topics quoted by the student about school, friends and life in Sweden indicate social talk seemingly adapted to early language learning stages. The student also described talking with the elderly during different activities. In sum, the use of spoken Swedish seemed to be a natural part of the work-related activities she performed. This also appeared conducive to building and maintaining relationships with colleagues and clients at the nursing home.

In a peer discussion (lesson 1:6), Maryam emphasised social talk as an integral part of the activities at a youth centre. The student described preparing and selling snacks to the students, as well as engaging in playing pool and doing ‘some nails with the gals’. However, she also stressed the importance of talking with the adolescents and keeping them company. When I asked about the topic, she laughingly asserted that they typically talk about the opposite sex. She also noted that the older adolescents used ‘some special dialect’ that she was sometimes unable to understand. She gave the example of an informal greeting (‘tja’), as opposed to more familiar varieties (‘hej’, ‘tjena’). In relating her experiences, she used several informal word choices which might reflect the language encountered at the placement such as killarna (the guys), tjejerna (the gals) and mackor (an informal word for sandwiches).

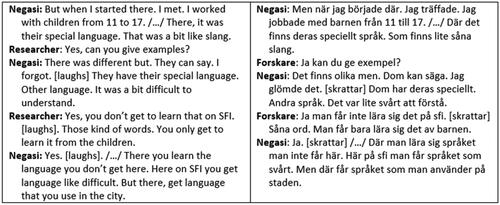

The difficulty of sometimes understanding informal language use was echoed by another student placed at the youth centre. He reflected that the younger children he typically worked with spoke ‘very good’ and comprehensible Swedish (‘like Swedes’). However, he found the language variant spoken by older children (aged 11–17) more challenging. This is shown in .

As evident, the student (Negasi) commented on the children using ‘slang’ and ‘special language’. He found this difficult to understand but was unable to provide examples. When I commented that such language is not taught at SFI, he affirmed that ‘Here on SFI you get language like difficult’ while the placement gives access to ‘the language that you use in the city’. Thus, the student expressed that the placement gave exposure to a different linguistic register that involved the use and understanding of colloquial expressions, as part of the field of discourse, and talking to children as part of the tenor.Footnote6 In reflecting on her initial experiences at her health centre placement, one student drew attention to another aspect of informal talk by admitting that she found it difficult to understand ‘the Swedish sense of humour’.

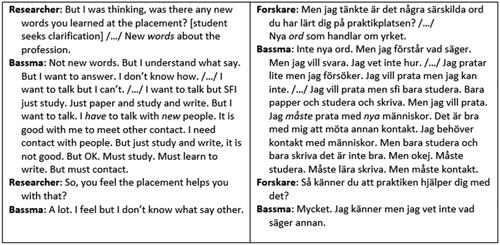

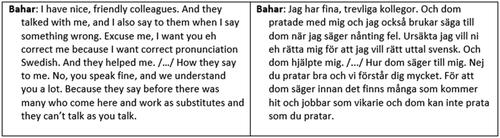

The placement experience of linguistic challenges related to oral communication was echoed by Bassma, a student placed at a preschool. Unlike some of the other students (see coming sections), she commented enthusiastically that ‘everyone speaks Swedish’ and that she ‘practices listening and talking a lot’. She also mentioned that she found pronunciation and vocabulary difficult. When asked a vocabulary-related question, she expanded on the perceived challenge and the value of practising Swedish outside the classroom ().

The student expressed a lack of ability, not opportunity, to engage in conversion: ‘I want to answer … I want to talk but I can’t’. She associated the on-site SFI teaching with ‘just paper and study and write’ and considered it insufficient (‘not good’). From the perspective of mode, she pointed out that the use of spoken Swedish had a limited role in classroom activities. Furthermore, she stressed the need to talk and establish contact with new people and confirmed the placement as beneficial for this. Thus, she seems to perceive the classroom and the placement as two quite distinct domains of language use, with the latter providing opportunities for making new contacts and taking different speaker roles. By emphasising the relational aspect of language use, she drew attention to a difference in tenor. A similar perspective on formal teaching was voiced by Zeina (lesson 2:11) who described working ‘a lot with grammar’ and that the teacher corrects their pronunciation when reading. This contrasted with her experiences of using spoken language at the placement, which is further described below.

Engaging in literacy practices

From the perspective of mode, the previous section reflects the overall tendency for the students to connect the placements with experiences and opportunities, or lack thereof, to practice speaking Swedish. There were few references to using writing, even when directly asked. However, one student, Jada, mentioned documentation as part of the workplace tasks at a nursing home (lesson 1:4). While she referred to documentation relating to the health of the clients, the writing she conducted herself was restricted to simpler tasks, such as keeping track of food and the temperature in the fridge: ‘Yes, I can do how many degrees in the fridge. I have written’. Thus, the use of writing seemed to be a small part of her placement experience. Bahar, having her placement at a pre-school, similarly expressed learning from her supervisor how to document absences (lesson 2:3). In a written evaluation, Ahmed mentioned that he, among many other tasks, learned about the administrative system during his placement at a hotel.

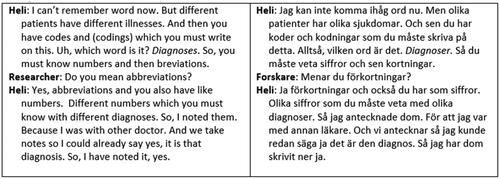

The only student who expressed engaging substantially in workplace-specific literacy practices was Heli, placed at a health centre. While initially assigned the reception desk, she felt unsatisfied and asked the manager’s permission to follow nurses and doctors into the laboratories (interview after lesson 2:4). After presenting workplace tasks (lesson 2:2), she described such extended activities as ‘great fun’ and that she learned how to take case-book notes using abbreviations and medical terminology. This involved field-specific use of written language. As shown in , she expanded on this in an interview.

The student described the need to use codes, numbers and abbreviations to document information about the patients’ diagnoses in order to communicate with doctors. She also recounted doing this herself when accompanying a doctor, which enabled her to confirm ‘yes, it is that diagnosis’. In other words, the use of writing seemed to be a prominent part of the activities available to the student. The student’s own agency and actions seemed to be important for her engagement. Successfully complaining about the initial tasks and thus gaining access to desired literacy practices indicates a complex and skilled negotiation of the tenor of the workplace. Her position as a well-educated track 3 student likely contributed to this success.

Other students contrasted the placement with classroom activities focused on writing, grammar and correct pronunciation. When asked about what they thought about the lessons connected to the placement in the oral evaluation (2:11), Zeina reflected that they practice reading and writing a lot in the lessons compared to the placement. Regarding the latter, she stated ‘it is just interview questions’, likely referring to one of the assignments in which they were supposed to bring interview questions to the placement. Silvana agreed that they had few opportunities to write at the placement but pointed out that they did get the opportunity to ‘write the texts and answer questions’ when they worked on the weekly assignments. The assignments generally included many placement-related questions to answer in their oral or written presentations.

Negotiating a language learner speaking role

Relating to the tenor of discourse, some of the students drew attention to how they negotiated their roles as both newcomers and language learners at the placement. In course instance 2, three of the four students participating in the oral evaluation I moderated commented on a supporting environment for speaking Swedish at the placements ().

Bahar evaluated her colleagues positively, as ‘nice, friendly colleagues’ and mentioned that she expressed her wish for them to correct her Swedish to help improve her pronunciation. She added that they did indeed help her, while also reassuring her that she speaks Swedish well in comparison to ‘many’ working there previously as substitutes. As such, Bahar appeared to feel validated as a competent language user.

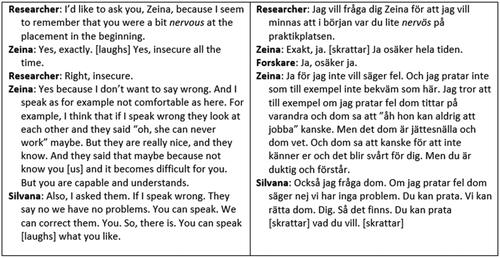

Similar experiences were voiced by Zeina and Silvana participating in the same evaluation. However, in an earlier lesson (2:3), Zeina had expressed feeling discomfort completing an assignment which required her to interview her placement supervisor about workplace experiences. It involved meeting the supervisor alone and posing questions while taking notes. It is possible that the assignment required her to negotiate the tenor of discourse in a way she found uncomfortable – putting her in the role of requesting information from a person in relative authority. Furthermore, she mentioned difficulties in using writing effectively while listening (‘I write wrong so I write again’). She also expressed being reassured by the supervisor who noted her discomfort (‘She said calm’). In the oral evaluation of the course, Zeina stated that ‘you get better every day … you can speak and write assignments and read questions and read understand also’. Prompted by my question, the student also elaborated on her initial nervousness. This is shown in .

The student confirmed that she ‘felt insecure all the time’ and elaborated that she ‘[does]n’t want to say wrong’. Furthermore, she gave the reason that she did not feel ‘as comfortable as here’, expressing the worry that ‘speaking wrong’ might cause them to ‘look at each other’ and say that ‘maybe she can never work’. Evidently, she viewed speaking Swedish at the placement as a high-stakes venture in terms of creating relationships and the prospect of future work. However, echoing the experiences of Bahar, she recounted being reassured by colleagues that she was ‘duktig’ (capable). She also stated that the placement colleagues expressed empathy. The meaning of ‘they know’ is not clear but might echo previous classrooms discussion in which the teacher assured the students that the people at the placements understand that they are language learners and have their placements to improve their Swedish. Zeina’s statement that ‘they said maybe because not know you [us] and it becomes difficult for you’ indicates an empathic stance while also signalling the asymmetrical relationship between the student and the placement colleagues, resembling that of a parent comforting a child. Silvana responded by voicing a similar experience of asking her colleagues if she ‘speaks wrong’ and being reassured that the colleagues do not have any problems understanding her: ‘you can speak what you want’.

In an earlier discussion after presentations of the supervisors (lesson 2:3), Silvana remarked that her supervisor slowed her pace when talking with her while speaking quicker and using more ‘dialect’ when speaking to other colleagues. In the same discussion, Heli commented that her supervisor talked slowly and only used words she already knew. She contrasted this with other colleagues speaking more rapidly which challenged her to concentrate more.

It seems evident that these students experienced a supportive and encouraging tenor for using the target language at their placements. The experiences voiced by Zeina clearly point to the necessity of adjusting to a different and potentially high-stakes sphere of language use, far from the relative comfort of the classroom. Her background in study path 1 seems a likely factor since it means that she has progressed through several SFI courses and thus likely spent a considerable time predominantly using Swedish in a classroom setting. Furthermore, she made a direct connection between her language proficiency and her prospects of being viewed as a competent worker. All three students needed to negotiate the tenor of discourse not merely as placement newcomers but also as legitimate users of Swedish outside the context of formal language education.

Learning placement-related vocabulary

From the perspective of field, the students rarely spontaneously referred to learning new vocabulary related to activities and domains of experience at the workplace. An exception was Heli who, as previously indicated, experienced learning terms related to medicine. In her individual interview, she stated that she both developed her language and saw a utility for her future career plans: ‘I thought that I developed a lot with the language since I have learned so many medical terms … it could be good for me before studying for assistant nurse’. When asked, she could not give any examples of such terms but reflected that many were the same as in other languages she knew.

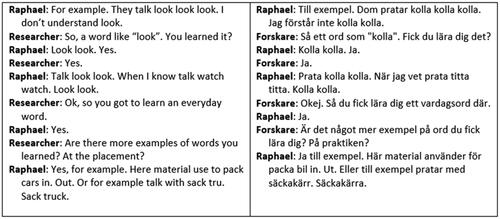

As exemplified in a previous section, students in the first course instance generally found it difficult, when asked direct questions, to give examples of words or expressions they had learnt. However, in an interview, one of the four male students who had chosen the branch warehouse, logistics and industry provided two examples ().

At his placement, the student (Raphael) dispatched provisions for communal services. The vocabulary commented on by the student reflects an expected feature of the relevant field. The repeated imperative kolla (meaning look but more colloquial than the standard titta) reflect the need of following instructions and säckakärra (sack truck) is a specialised noun referring to equipment the student likely used. Notably, the student used a colloquial binding morpheme (säckakärra) which suggests the word was learned through speech. In sum, the student referred to words pertaining to both roles (tenor) and activities (field) related to manual labour at the placement.

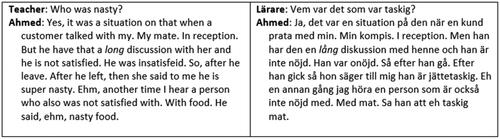

In the second course instance, the students were asked to collect words from their placement which were discussed in the lessons. In the oral evaluation, Silvana mentioned several of the words she had learned like an abbreviation for unsocial working hours (‘OB’), coordinator and an infrequent word explained by her supervisor, inkännande, meaning compassionate or responsive. She also laughingly added two words not chosen for the presentation, tålamod (patience) and the (at least for me) quite opaque, word lapplåda (e.g. pad box). When asked, the student confirmed it referred to a box with bibs (haklapp). The last three of these words reflect specific activities and roles in taking care of the children. One of the students, Ahmed, was placed in a hotel. He was the only one to choose an informal word, taskig (nasty). The teacher asked the student to explain the context ().

The student provided two contexts, both from experiences of dealing with customer complaints. In a discussion following the presentations of the supervisors (lesson 2:3), the same student also mentioned picking up a new word combination when his supervisor described administrative tasks: skapa rutin (create routine). As was the case for Raphael and Silvana, the words and expression both constitute the field of discourse and reflect work-specific roles, in this case of providing services, appeasing dissatisfied customers and conducting administrative tasks.

Experiences of isolation and lack of language-speaking opportunities

The previous themes reflect the fact that many of the students who participated in the study were women who had selected healthcare, school and nursing as their branch. While several of them voiced positive experiences, there were some exceptions. In an early lesson, Mona, placed at a pre-school department with toddlers, explained that it was difficult to talk during the workday: ‘When they sleep, everyone is silent. And then … it is chaos’ (lesson 2.2). With her placement at a service home for children with functional variations, Amila expressed that the children had little inclination to talk and preferred to be left alone (lesson 1:6). This reflects a distanced tenor and activities, involving helping the children with hygiene, clothing and food, in which the use of spoken Swedish had a limited role.

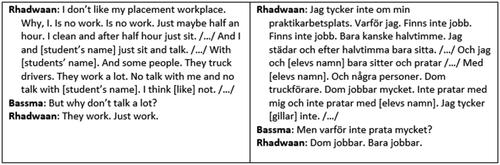

Contrary to the female participants, the male participants had mainly opted for the branch called warehouse, logistics and industry. Several of them expressed dissatisfaction with their limited opportunities to use the target language. A peer discussion between Rhadwaan, who was placed at a warehouse, and Bassma is shown in .

Rhadwaan explicitly stated his dislike for the placement and complained that there was not enough work for him to do. It followed that he spent most of the time talking with his coursemate (in Swedish). He elaborated that the other people at the warehouse were truck drivers who do not have time to talk Swedish with them. His statement ‘They work … just work’ indicates a work intensity contrasting with his own lack of work. This suggests that there was a clear division of labour at the placement tied to different roles and activities that entailed little in the way of interaction.

Another male participant in course instance 1, Masoud, was very critical of his placement in a kitchen. He did not perform any of the assignments but shared some experiences in whole-class discussions (lesson 1:5). Similar to Rhadwaan, he stated that the people working at the restaurant did not have the time to interact. He also expressed being isolated in the kitchen with doing the dishes. His meaning was not easy to interpret, but he seemed to sarcastically inquire if he was supposed to talk with the empty room and the kitchen utensils. He succinctly concluded, ‘No, not good for language’.

Raphael, who remembered learning a few words at his dispatch placement, phrased himself more guardedly compared to Rhadwaan and Masoud. However, he stated that he did not get many opportunities to speak Swedish since most of his colleagues were not very proficient in Swedish and used other languages to communicate with each other. While having the opposite experience of Bassma, he similarly assigned importance to the L1 or L2 status of the Swedish speakers.

A third male student, Jean, was placed in a truck garage and participated in the oral evaluation of course instance 2 (lesson 2:11). Similar to other students choosing the same branch, he described very limited opportunities to use the target language. In the oral evaluation, he was silent as the others expressed their positive placement experiences. When asked directly about his own experiences, he stated that he worked alone and ‘nobody are there to help me … the driver went out and I sit alone’ (said in English).

From the perspective of mode, these students all expressed that using Swedish had a limited role in their placement activities. Furthermore, several of the male students (Rhadwaan, Masoud and Jean) voiced spatial isolation from Swedish-speaking colleagues, which reflects a tenor unconducive to using language interpersonally.

Final observations

While the presentation of the findings has mostly focused on the use of Swedish in speaking and writing, it is important to note that there were other important facets to students’ experiences at the placements. For example, Zeina (2:11) related an episode in which she used a non-target language to explain the need for some parents to adjust to a new bus schedule. After presenting her placement in an early lesson (2:2), Bahar shared that a girl newly arrived from Ukraine had singled her out among the adults for play and comfort, in which the use of Swedish likely had a peripheral role. In his written evaluation, Ahmed, who had previous experience working at hotels, expressed learning a lot about the line of work in Sweden and appreciated that he was trusted to perform a range of tasks at the hotel. These kinds of experiences – or lack thereof – were important for the students’ meaningful participation in the placements.

Conclusions and discussion

In the present study, I have explored how adult L2 learners perceived their possibilities to use and develop the target language (Swedish) when formal language teaching was combined with placements. Thus, I have addressed the lack of research on how adult students in basic language education perceive their language learning opportunities when they participate in a current placement-focus municipal effort to expand their opportunities for language development.

The findings show that the experiences differed substantially among the students. The limited opportunities voiced by the male group of students on placements related to the branch industry, warehouse and logistics echo findings from Sandwall (Citation2013) and Strömmer (Citation2016) of simple and solitary work requiring little social talk and other interaction. The participant working in dispatch, Raphael, also raised the issue of colleagues not being proficient in Swedish. This contrasted with more positive experiences of engaging in interaction and receiving support voiced by several of the students within education, healthcare and nursing. Partly resembling findings in Duff et al.’s study (2002), they seemed to appreciate interacting with and receiving linguistic support from Swedish L1 speakers.

From the perspectives of field and mode, these varied experiences reflect the role of language (or lack thereof), in the activities offered at the different placements. In many ways, these findings are expected. Nevertheless, they reveal an important tension between different priorities in the course and the placement scheme provided for the students. On the one hand, there was the curricular objective of providing a language practicum benefitting all students. On the other hand, the course and placements adhered to the students’ choices of branch according to the overarching municipal strategy for SFI teaching. If supporting the students’ holistic language learning is the main objective, some branches will likely offer more promising contexts than others.

It appears evident that the students’ different experiences were shaped by a current SFI paradigm focused on the student’s engagement with the work-life domain (Rosén and Babba-Gupta Citation2013, Lindberg and Sandwall Citation2017). From this perspective, participants such as Heli and Ahmed expressed that the placements enabled them to develop professional knowledge aligned with their current career goals. Furthermore, it came to my knowledge that some of the students within industry, warehouse and logistics were offered and accepted employment at their previous placements. The teacher and the project leader considered this a favourable – if not explicitly targeted – outcome while also raising concerns about the students’ long-term language development when they leave the SFI program for workplaces that offer limited opportunities to communicate in Swedish. This indicates the complex balancing of priorities and goals in programs of this kind. Although employability is often associated with short-term goals for language teaching (e.g. Ahlgren and Rydell Citation2020) it is important and of long-term significance to the individual.

While all placements were not created equal, many of the students expressed that the placements opened a new and valuable domain of language use. In keeping with previous findings (Ahlgren and Rydell Citation2020), they found the formal SFI teaching inadequate for developing oral skills. There are clear parallels to studies of specific professional training programs involving more advanced language learners. Bassma’s pleasure at interacting in a workplace where ‘everyone speaks Swedish’ resembles the enthusiasm participants in Duff et al.’s (Citation2002) study expressed in encountering ‘real Canadians’. At the same time, the participants confirmed previously reported challenges such as understanding jokes and colloquial language (Yates and Major 2014, Myles Citation2009).

Moreover, the findings showed how the students’ role as language learners was a salient aspect of the tenor the students negotiated at their placements. Among the participants, the anxious experience of being under an evaluating gaze (see Ahlgren and Rydell Citation2020) was most clearly articulated by Zeina. However, she expressed receiving support and gradually becoming more comfortable. The design of the language practicum might have been beneficial in the sense that the students were assigned supervisors who could be expected to accept the communicative burden (see Major et al. Citation2014) and provide linguistic support.

Regarding the perceived difference between language use in the classroom and at the placements, it is interesting to note that students associated the classroom practice mostly with grammar and writing even though considerable classroom time had been spent on oral presentations and discussions. It is possible that the students were referring to SFI teaching in general or considered activities involving my research as something outside the regular teaching. However, it seems clear that oral use of L2 outside the classroom context was highly desired by the students and an important factor for their satisfaction, or lack thereof, with the placement visits. A possible direction for future research could be to take a more longitudinal perspective on students’ experiences of placement-integrated teaching by following them beyond the completion of the study program. Since the present study only followed the students while they participated in the course, there is a lack of data on how they perceive the effort from a long-term perspective, for example, when studying more advanced language courses or after having received employment.

Implications for the design of similar programs include being mindful of conflicting priorities between language learning and employment goals. To prevent the divergent experiences voiced by the students in the present study, it appears necessary to choose placement sites carefully according to their preparedness to support and stimulate the students’ active language use. However, in light of persisting workplace and deficit discourses surrounding the SFI program (see Rosén and Babba-Gupta Citation2013, Lindberg and Sandwall Citation2017), it is encouraging that several students voiced that the placement-integrated teaching extended language learning opportunities beyond both the classroom and the specific workplace context, as evidenced by their reported experiences of engaging in social talk with L1 speakers of Swedish. This underscores the importance of designing teaching activities, assignments and placement visits with different domains of language use in mind. Furthermore, it may be necessary to consider the possible nervousness and lack of confidence some students may feel in engaging with L1 speakers outside the classroom (see also Rydell Citation2018). This could be addressed in the classroom, by discussing concerns and reasonable expectations of support from more proficient speakers of Swedish in the mutual act of communication. This is particularly important in classrooms where adult learners have varying experiences of using the target language publicly and when engaging in workplace practices.

Based on the present findings and previous research, the language learning potential of placement visits can be expanded through the way they are prepared and followed up (see Riddiford and Joe Citation2010, Sandwall Citation2013). In the present study, the task related to workplace vocabulary introduced in the second course instance encouraged discussions about field-related words and expressions. Following Riddiford and Joe (Citation2010), it could be beneficial to analyse examples of authentic workplace discourse in the classroom focusing on features such as small talk (Yates and Major Citation2015), requests (Li Citation2000) refusals (Riddiford and Holmes Citation2015) and jokes (Myles Citation2009, Wedin and Norlund Shaswar Citation2023). These are all tricky areas relating to the tenor of discourse, as they involve the negotiation of roles and relationships. As exemplified by Raphael’s ‘kolla’, informal language directly related to simple work activities may be challenging to understand as well. Finally, it may be fruitful to discuss multilingual aspects of workplace communication, involving the potential value of the students’ entire linguistic repertoire. This repertoire involves using non-target languages to facilitate communication (see Duff et al. Citation2002, Moanakwena Citation2021) and also includes the ability to understand and adapt to other language learners’ way of using Swedish—a beneficial competence they are likely to acquire in the SFI classroom.

Disclosure statement

The study received limited funding (90 hours) from the participating municipality (undisclosed for reasons of confidentiality) to facilitate the researcher’s involvement in ongoing evaluation. The time dedicated to data processing, analyses, literature review, and writing for the purpose of this article was funded internally by Malmö University and the research program Literacy and Inclusive Teaching (LIT).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 Other orientation courses can target, for example, digital skills, knowledge about Swedish society, or tutoring in the first language.

2 It follows that the starting level of course B and C vary depending on the track.

3 In relation to the Common European Framework of Reference for languages (CEFR), the targeted language proficiencies roughly correspond to A2/advanced beginner (Course C) and B1/threshold independent user (Course D).

4 In the first course instance, two students were selected from two different branches. The ambition was to have these interviews with all the students, but this proved not to be possible due to schedule constraints. Therefore, the concept of individual interviews was abandoned in favour of group activities. In the second course instance, one interview was conducted to document experiences of a student who had to cease her placement and course participation to commence Swedish studies on the post-SFI level. These interviews are treated as part of the ethnographically collected material.

5 In all extracts, the English translation is shown to the left while original language wordings are represented in the right column. Omitted discourse is indicated by “/…/”, while italics show clear emphasis. Unclear audio is marked by parenthesis.

6 While the students reflection about learning “difficult” language in SFI was not probed further, my observations of the SFI teaching showed frequent focus on formal registers, such as using language for purposes of presentations and argumentations and learning vocabulary related to work-life and grammar.

References

- Ahlgren, K., and Rydell, M., 2020. Continuity and change: Migrants’ experiences of adult language education in Sweden. European journal for research on the education and learning of adults, 11 (3), 399–414.

- Anderson-Levitt, K. M., 2006. Ethnography. In: J. L. Green, G. Camili and P. B. Elmore, eds. Handbook of complementary methods in education research. Washington: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, 279–295.

- Baynham, M., 2006. Agency and contingency in the language learning of refugees and asylum seekers. Linguistics and education, 17 (1), 24–39.

- Braun, V., and Clarke, V., 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3 (2), 77–101.

- Brenner, M. E., 2006. Interviewing in educational research. In: J. L. Green, G. Camili and P. B. Elmore, eds. Handbook of complementary methods in education research. Washington: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, 357–370.

- Duff, P.A., Wong, P., and Early, M., 2002. Learning language for work and life: the linguistic socialization of immigrant Canadians seeking careers in healthcare. The modern language journal, 86 (3), 397–422.

- Fangen, K., 2005. Deltagande observation. Malmö: Liber ekonomi.

- Halliday, M. A. K., and Mathiessen, C., 2014. Halliday’s introduction to functional grammar (4th ed.). New York: Routledge.

- Lai, C., Zhu, W., and Gong, G., 2015. Understanding the quality of out-of-class English learning. TESOL quarterly, 49 (2), 278–308.

- Lehtonen, T., 2017. You will certainly learn English much faster at work than from a textbook: Law students learning English beyond the language classroom. System, 68, 50–59.

- Li, D., 2000. The pragmatics of making requests in the L2 workplace: a case study of language socialization. The Canadian modern language review, 57 (1), 58–87.

- Lindberg, I., and Sandwall, K., 2017. Conflicting agendas in Swedish adult second language education. In: C. Kerfoot and K. Hyltenstam (Eds.), Entangled discourses: South-North orders of visibility. New York: Routledge, 119–136.

- Lum, L., Alqazli, M., and Englander, K., 2018. Academic literacy requirements of health professions programs: challenges for ESL students. TESL Canada journal, 35 (1), 1–28.

- Major, G., et al., 2014. Working it out: Migrants’ perspectives of social inclusion in the workplace. Australian review of applied linguistics, 37 (3), 249–261.

- Martin, J. R., 2001. Language, register and genre. In: A. Burns and C. Coffin, Eds. Analysing English in a global context: a reader. New York: Routledge, 151–166.

- Moanakwena, P. G. 2021. Language and literacy practices of hairdressers in the Botswana multilingual context: Implications for occupational literacy development in vocational training [Doctoral dissertation]. The University of British Columbia.

- Myles, J., 2009. Oral competency of ESL technical students in workplace internships. TESL-EJ, 13 (1), 1–24.

- Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) [2016]. OJ L 119/1 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679.

- Reinders, H., and Benson, P., 2017. Research agenda: language learning beyond the classroom. Language teaching, 50 (4), 561–578.

- Riddiford, N., and Holmes, J., 2015. Assisting the development of sociopragmatic skills: negotiating refusals at work. System, 48, 129–140.

- Riddiford, N., and Joe, A., 2010. Tracking the development of sociopragmatic kkills. Tesol quarterly, 44 (1), 195–205.

- Rosén, J.K., and Babba-Gupta, S., 2013. Shifting identity positions in the development of language education for immigrants: an analysis of discourses associated with ‘Swedish for immigrants. Language, culture and curriculum, 26 (1), 68–88.

- Rydell, M., 2018. Being ‘a competent language user’ in a world of others: adult migrants’ perceptions and constructions of communicative competence. Linguistics and education, 45, 101–109.

- Sandwall, K. 2013. Att hantera praktiken: Om sfi-studerandes möjligheter till interaktion och lärande på praktikplatser [Doctoral dissertation]. Göteborgs universitet.

- SFS 2003:460. Lag om etikprövning av forskning som avser människor. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/lag-2003460-om-etikprovning-av-forskning-som_sfs-2003-460.

- Skolverket. 2022. Kursplan för kommunal vuxenutbildning i svenska för invandrare. https://www.skolverket.se/undervisning/vuxenutbildningen/komvux-svenska-for-invandrare-sfi/laroplan-for-vux-och-kursplan-for-svenska-for-invandrare-sfi/kursplan-for-svenska-for-invandrare-sfi.

- Strömmer, M., 2016. Affordances and constraints: second language learning in cleaning work. Multilingua, 35 (6), 697–721.

- Swedish Research Council. 2017. Good research practice. Stockholm: Vetenskapsrådet. https://www.vr.se/download/18.5639980c162791bbfe697882/1555334908942/Good-Research-Practice_VR_2017.pdf

- Timmermans, S., and Tavory, I., 2012. Theory construction in qualitative research: from grounded theory to abductive analysis. Sociological theory, 30 (3), 167–186.

- Tracy, S. J., 2020. Qualitative research methods: collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley and Sons.

- Wedin, Å., and Norlund Shaswar, A., 2019. Whole class interaction in the adult L2-classroom: the case of Swedish for immigrants. Apples – journal of applied language studies, 13 (2), 45–63.

- Wedin, Å., and Norlund Shaswar, A., 2023. Interaction and meaning making in basic adult education for immigrants the case of Swedish for immigrants in Sweden (SFI). Studies in the education of adults, 55 (1), 24–43.

- Willis, J. W., and Edwards, C., 2014. Action research: models, methods and examples. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

- Yates, L., and Major, G., 2015. Quick-chatting, “smart dogs” and how to “say without saying”: small talk and pragmatic learning in the community. System, 48, 141–152.