Abstract

Despite the increasing number of non-traditional students entering higher education (HE) in England, HE choices remain stratified by social class. Mature working class students are a target group of the widening participation policy, yet little attention has been given to their HE choices and decision-making. Through narrative inquiry, this study uses a creative method alongside focus groups and semi-structured interviews, and contributes a class perspective to the HE decision-making for 13 women on an Access to HE course. It links sociological theory to adult education, through a Bourdieusian framework. It evidences structural constraints and perceptions of belonging that impeded choices. A sense of place and feelings of fit (habitus) were significant for destination decisions. However, Access to HE course teachers were positively influential in helping students challenge embedded habitual ways of thinking and practice and in raising self-efficacy. The findings offer explanations as to why participation rates may be increasing but not widening enough. It illuminates how social class differences (intersected by age and gender) are crucial to understanding HE decision-making and places a much-needed focus on mature students to the widening participation and social mobility agenda.

Introduction

This study contributes a class perspective to the decision-making of mature students entering higher education (HE). Policy discourse presents HE as a mechanism for promoting upward social mobility, and achieving social justice (Basit and Tomlinson, Citation2012). Historically, the British HE system has been stratified along social class lines. However, policy discourse has shifted over the past 60 years from a focus on expanding the number of students entering HE to widening participation from under-represented groups (Boliver & Wakeling, Citation2016). Widening participation has been defined as activities and interventions to create a HE system that addresses the underrepresentation of particular groups (Jones & Thomas, Citation2005), including those from less advantaged backgrounds, ethnic minority groups, and mature students (DBIS, Citation2011). Despite the widening participation agenda, the HE system remains class-stratified. Students’ HE decision-making has shed light on this inequality in participation.

With respect to students aged 18 to 21, HE choices are qualitatively different for those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds compared to those from higher socioeconomic backgrounds. Those from higher socioeconomic backgrounds disproportionately enter higher-status institutions, such as Oxford or Cambridge. Those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to enter post-1992 institutions (Boliver, Citation2013; HESA, Citation2022). The work of Pierre Bourdieu has been employed to understand how class can influence choice-making. Research has found that working class students avoid institutions where they feel they do not belong (Crozier et al., Citation2019; Reay, Citation2018; Scanlon et al., Citation2019). Those who see such establishments as ‘not for the likes of me’ are more likely to exclude themselves (McGrath & Rogers, Citation2021; Reay et al., Citation2009). Less is known about mature working class students’ decision-making.

Mature students are commonly referred to as those over the age of 21 at the start of an undergraduate degree course (UCAS, Citation2021). The number of mature undergraduate entrants to UK Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) has declined over the past decade, particularly those studying part-time, whose numbers have fallen by more than half since 2010 (OFS, Citation2020). In 2020, mature students comprised 24% of home entrants to full-time undergraduate courses. The numbers decreased by 40% between 2010/11 and 2017/18, from more than 400,000 to fewer than 24,000. More recently, the numbers peaked at approximately 254,000 (2019/20).

An increasingly popular route to university for mature students is via Access to HE Diploma courses (Hubble & Bolton, Citation2020). Since recommendations in the Russell Report (Citation1973), the Access to HE Diploma is delivered in further education (FE) colleges in England and Wales for those mainly mature entrants with neither traditional A-Level nor vocational qualifications. Access to HE courses have made a significant contribution to the widening participation agenda because they have led to increasing numbers of mature students continuing to HE. In 2020 24,465 mature students achieved an Access to HE Diploma and entered HE (QAA, Citation2021). These students are significant, yet more recently they have become invisible in the widening participation agenda, and have not been prioritised by many universities (Fraser & Harman, Citation2019; OFS, Citation2020). This study places a much-needed focus on this group of students and seeks to understand their HE choices and decision-making.

Widening participation in higher education

This paper sits within various literatures examining the broader social and political context of widening participation and social mobility. The narrative of widening participation became prominent in the HE sector following the Dearing Report (Dearing, Citation1997), and conspicuous in the policy rhetoric of the New Labour government (1997–2010), keen to widen participation to groups traditionally underrepresented in HE. Participation rates have increased. The 2020/21 HE entry percentage by age 25 was calculated to be 47% (DfE, Citation2023); however, increasing access has not been accompanied by equal social access. It is still more challenging for those from lower-income backgrounds to enter HE (Browne, Citation2010; Sullivan, Heath & Rothon, Citation2011), further exacerbating the reproduction of inequality (Atherton, Citation2017; Farhan & Heselwood, Citation2019).

The government’s widening participation and social mobility agenda is not without criticism. The narrative of widening participation, which creates the impression that anyone can enter HE, helps perpetuate the deceit of a meritocratic system. It conceals existing inequalities, suggesting those who fail to achieve only have themselves to blame (Young, Citation1958). It focuses on aspiration and also places weight upon students to make ‘good choices’ for themselves regarding which university to progress to (Baker, Citation2019; Rainford, Citation2023). Economic barriers and students’ social context are significant to their journeys, so success cannot wholly be attributed to individual hard work. This is particularly relevant to mature students. They are more likely than younger students to come from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds (Busher & James, Citation2020). Many mature working class students taking an Access to HE course have to juggle paid work and caring responsibilities alongside their studies. This can impact course success and progression options (Mannay & Morgan, Citation2013). Context is therefore significant to their HE choices.

Understanding HE participation and entry decision-making of mature students is a timely issue. Education is part of the post-Covid strategy towards ‘levelling up’ the country, and increasing social mobility was identified as a core objective (SMC, Citation2022). One of the seven key pillars for recovery included post-qualification access to universities and increasing the number of ‘non-traditional’ students they take. Mature working class students fall under this category however, they have recently become invisible in the widening participation agenda (Fraser & Harman, Citation2019).

Significance of class upon HE decision-making

Official policy in the UK has assumed that students make choices in a rational, context-free manner. Focus has been placed on providing more information to help students make decisions (DBIS, Citation2011) based on performance indicators such as the Teaching Excellence Framework (DBIS, Citation2016). HE Policy narratives assume that such information will enable all students to make the same choices, but ignore contextual issues despite evidence showing that HE choices are structurally constrained (Baker, Citation2019).

While widening participation and social mobility agendas focus on cultivating positive outcomes for underrepresented groups, their underlying assumptions have led sociologists to take a more critical perspective. Structural factors limit the choice-making of younger working class students (Baker, Citation2019; Woodward, Citation2020), making upward mobility via education problematic. Fear of debt is prominent, especially because of increasing tuition fees (Callender & Jackson, Citation2008). Despite concerns about the impact of reduced public subsidies for students from low-income households (Dearing, Citation1997), the New Labour government abolished maintenance grants and introduced a means-tested fee policy backed by income-contingent loans. Mature students were particularly affected by these changes; for example, two major dips in mature applicants since 2008 coincided with the increase of tuition fees in 2012 and the withdrawal of NHS bursaries in 2017 (Stephenson, Citation2018). Significantly, subjects allied to medicine and healthcare have been the most popular route for Access students. The financial and practical advantages of staying at home rather than moving away to university are more likely to sway the decisions of those from working class backgrounds (Patiniotis & Holdsworth, Citation2005).

HE choices are class-bound. Even with the increasing number of working class students applying for university, the HE system remains stratified. Students from higher socio-economic backgrounds disproportionately enter higher-status institutions such as Oxford or Cambridge (Baker, Citation2019; DfE, Citation2023; HESA, Citation2022). Despite higher tariff providers accepting more students from disadvantaged backgrounds, the equality gap remains stark. Students from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to study less prestigious degrees than their peers. They are particularly poorly represented in Russell Group Universities, which are a self-selected association of public research universities in the UK (Boliver, Citation2013; Patfield et al., Citation2023). This is evident when looking at specific courses; for example, in 2020, students from advantaged backgrounds were 25 times more likely to be placed on medicine courses than their disadvantaged peers (Bolton, Citation2024). Those from disadvantaged backgrounds who could apply to elite universities disproportionately have not, further reducing their chances of upward social mobility (McGrath & Rogers, Citation2021). This matters because going to an elite university impacts future life chances; graduates from elite universities enjoy an advantage in the graduate labour market (Stenhouse & Ingram, Citation2024).

Although this paper focuses on class, the intersection of gender and ethnicity also has a significant impact on HE choice and success (Croxford & Raffe, Citation2014; Egerton & Halsey, Citation1993; Reay et al., Citation2005; Scandone, Citation2022). Therefore, increased access has not been accompanied by equal social access. This is concerning because HE choice-making plays a crucial role in the reproduction of divisions and hierarchies.

A cultural approach to understanding the significance of class

The work of Pierre Bourdieu may be drawn upon to understand how social class plays an important role in HE participation. A Bourdieusian approach to class analysis conceptualises class in relation to where individuals are positioned in shared social spaces (field) according to their varying levels of resources (capitals). It connects cultural identity to inequality, articulating social order in everyday life, such as through education, values, and judgements (Bourdieu, Citation1986). His theory of generative structuralism emphasises the interplay between individuals and larger social structures that shape and constrain actions and choices. Bourdieu’s concept of habitus refers to a set of attitudes and beliefs embodied in how people think, feel, speak, and gesture. The habitus conditions and shapes how individuals perceive the world around them, their sense of place, and life choices (Bourdieu, Citation1984, p. 466). Their position is determined by resources and cultural differences - capitals. In Bourdieusian terms, students from different class backgrounds have ‘different amounts and quality of ‘capital’ with which to play’ (Crozier et al., Citation2008, p. 168).

Through a Boudieusian lens, sociologists have come to understand how young working class students may exclude themselves from institutions where they feel they do not belong. For example, studies by Espinoza et al. (Citation2023) and Reay (Citation2021) reported disjunction between students’ working class habitus and elite universities, due to their exclusive and excluding cultures. Reay identified students displaying ambiguity and aversion to university which was a culture shock.

Middle class students have advantageous access to guidance, advice and opportunities (cultural capital) when applying to HE. Lack of access to privileged social networks (social capital), middle class parents’ understanding of the hierarchical nature of HE, differing input from private and state schools, and students’ perceptions of which university is right for them are significant and beneficial factors when making decisions (Bradley et al., Citation2013). Seemingly, HE choices are not only made but are also made up of circumstances, dispositions and embodied perceptions of self (Ball et al., Citation2002). Therefore working class students’ HE choices are shaped by the structural constraints imposed by their social contexts.

Research focusing on the HE decision-making experiences of mature working class students is underdeveloped in the academic literature. This lacuna is significant because their choices regarding which type of institution and programme to apply to will depend on a whole range of factors relating to their economic and personal circumstances. Previous studies exploring their progression into HE via an Access to HE course have theorised this process in terms of identity changes and the meaning of becoming a mature student (Davies & Williams, Citation2001; Brine & Waller, Citation2004), decisions relating to returning to education (Busher & James, Citation2020), and experiences during their course (James et al., Citation2013). Their decision-making needs further investigation to provide a mature student context to the widening participation agenda.

Methodology

This paper reports on an aspect of a doctoral research project. The study used a narrative inquiry methodology to foreground the lived experiences of mature working class women progressing to HE via an Access to HE Course at a further education college in South West England (Purple College). The study sought to answer the question ‘What is the meaning of an Access to HE course for mature working class women?’. The data presented in this paper relates to the sub-question ‘What conditions do participants say influence their decision-making processes connected to HE progression?’. The research took a relativist ontology and constructivist approach.

Participants’ personal histories and socio-cultural experiences were important to the constructions of meaning they gave to their return to education. Narrative inquiry is a methodology which uses life experiences, stories and interviews as the unit of analysis (Bochner and Herrmann, Citation2020), so was an effective methodology for this project. This approach enabled the researcher to use the theoretical framework to look for ways to understand participants’ real-life experiences through their stories, and explore latent meanings to these constructions.

A sample of 29 women took part. Whilst it was not the intention to ignore the stories of male students, women comprised the majority of this Access cohort, reflecting the national picture (QAA, Citation2021). At Purple College, of the 2020/21 cohort, 128 of the 144 students who achieved their Diploma were female. Women also make up the majority of ‘non-traditional students’ in HE (Hubble & Bolton, Citation2020). Access to participants was gained through the researcher’s role as a sociology teacher on the Access course. Due to the ease of access to students as participants, a non-probability sampling technique was used. The sampling approach was purposive; the study sought to gather the stories of mature working class women who had reached the end of their Access course and were progressing into HE. A convenience sampling strategy was taken by selecting participants based on accessibility to them. Recruitment adverts were posted on the college’s Virtual Learning Environment (VLE). 13 of the 29 women who took part discussed their HE decision-making at length during their interviews, and this data is included in this paper (see for the participant list)

Table 1. Participant list.

Participants self-defined their social class. To corroborate Lehmann’s (Citation1969) use of first-generation student status was drawn upon to substantiate their class identities. This takes parental education as an indicator of social class, given the importance of the transmission of social advantages through families. Their home postcodes were also referenced against the Adult HE 2011 measure. This assigns a quintile to a geographical area based on the proportion of adults from that area that held a higher qualification at the point of the 2011 census. Quintile one shows the lowest rate of participation. Quintile five shows the highest. All participants in the study lived in quintile 2 and 3 areas. Correspondingly, Purple College sat in a district with the third-highest level of income inequality within its county (MoH, Citation2019). These measures considered the levels of cultural capital they had access to (Abrahams & Ingram, Citation2013; Bourdieu, Citation1997). These factors indicated participants belonged to a lower socio-economic group. In the UK today, people still understand traditional class labels of working, middle and upper class (Savage, Citation2015). Therefore, in this paper, these everyday descriptions are used.

Methods

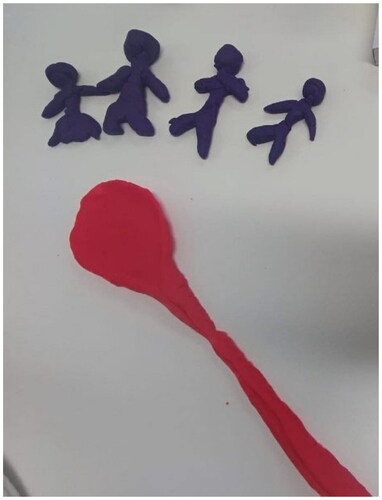

Three online focus groups comprising a total of 14 participants, and 15 one-to-one semi-structured depth interviews were conducted via Microsoft Teams, lasting between 45 minutes and one hour. Research moved online during the Covid-19 pandemic. There were concerns about online interviewing because there is a lack of presence and proximity compared to face-to-face methods. Asking participants to open up through a screen seemed clinical and had the potential to limit the depth and detail, which was important to the aims of the study. To mitigate against these concerns, Play-Doh modelling was incorporated as a creative interview method. Utilising modelling alongside interviews can be a particularly non-intimidating creative method (Abrahams & Ingram, Citation2013). All participants were given the option to use Play-Doh and the reasons behind the researcher’s decision to use Play-Doh modelling was explained. Those who were creatively confident or could access Play-Doh did so (Rainford, Citation2020).

Participants were invited to create models to depict any poignant aspects of their educational journeys. They were given time to reflect and turned their camera off whilst they did so. They then explained what their models depicted and asked to elaborate where appropriate. This thinking time led to in-depth and thought-through responses and a rich, participant-led creation of data. When analysing the data, the creations and narratives depicted semantic understanding and were also interpreted to construct latent meanings. The participatory nature of Play-Doh modelling placed participants at the centre as ‘experts’ of their own life stories (Leitch, Citation2008) and gave them control over the creation of their data. Modelling helped mitigate against the formal and seemingly distance nature of online interviewing.

Data was generated in line with British Education Research Association guidelines for ethical research (Citation2018) and ethical approval from my University was granted. Informed consent was gained from participants, and data was anonymised (pseudonyms used).

Data analysis

Interviews were video recorded, transcribed and analysed through a reflective thematic analysis guided by Braun & Clarke’s (Citation2022) six-recursive-step framework. Coding was largely theory-driven (deductive). The use of Bourdieu’s concepts of habitus, capital and field as a theoretical lens helped to understand participants’ constructions of their return to education. Through coding, themes were generated. This paper reports on the theme ‘The Influence of Capital Over Aspirations and Expectations’ which explores the financial, cultural and social aspects of decision making.

At the time of interviewing, the women had accepted or declined university offers, pending confirmation of their final grades. Moving away to university was not an option due to being settled in their homes, jobs, and family commitments. There were three ‘local’ options for these women. First, an elite Russell Group University situated 22 miles from ‘Purple College’. Secondly, a Post-92 (former polytechnic) university, 29 miles away. The third option was the foundation degree provision at Purple College. Sense is made of the data relating to HE decision-making through an interweaving of the analysis and discussion, organised into four sub-themes; ‘The influence of capital over aspirations and expectations’, ‘Choices and sense of belonging’, ‘I may have to learn to talk posh’ and ‘Impact of significant others’.

The influence of capital over aspirations and expectations

To understand the impact of financial and social conditions on aspirations and expectations, the meaning participants gave to their experience on their course in regard to HE decision were deducted through Bourdieu’s concept of capitals. For these participants, gender and the social roles the women felt they must perform for their families came to the forefront of their narrations, particularly in regards to the financial impact of study upon raising their families. Economic and social capital was of paramount consideration.

Being settled in their homes meant their HE options and graduate career choices depended on the job market in their local area, and childcare arrangements. These constraints were articulated by Deena, a 37-year-old single mother. She was remaining at Purple College’s provision to study health and social care. She described her Play-Doh model () as representing herself as an ‘old bird’:

Access has given me the wings to fly, and hopefully leading to a better job … I’m an old bird so my wings are clipped … I have my nest to look after. I can’t fly far … I’m staying here, which is close to my nest … and to my parents … and my job (Deena).

The imagery of the bird represented the prevalence of her home and close family (nest) aligned with her academic growth (wings). Her choice of degree was restricted to the foundation degree offered at Purple College, yet having a HE option at the college opened up the opportunity for further study which she otherwise would not have been able to persue:

… the money spent on petrol and parking…not being close to home if the kids need me…leaving really early in the morning… have to ask my mum to have the kids more, it just wouldn’t work. So, I only applied to [Purple College’s HE in FE provision] (Deena).

I only applied to [Post-92 university] … it’s the nearest and I hope to find someone to car share with to save petrol costs (Felicity).

Gender roles delineated the possible from the impossible as proximity to childcare, especially free childcare, also mitigated choices. As a single parent, 26-year-old Zara’s options were mediated by the practicalities of nursery drop-off:

I chose [post-92 university] because of its car park. I need to drop [son] off, drive up, park, go to lectures, get back to the car and get to the nursery for pick up. Public transport is not an option (Zara).

It was the only uni I applied for. Others would be too far away from my parents’ house, and they are going to look after my girls when I go (Natalie).

I need to drive there and work that out around school (Felicity).

Connie, a 47-year-old mother to a 16-year-old son, felt making friends with other mothers was important:

I know nursing attracts mostly women…expect to find other mature students and mums there. Making friends with people like me, you know, older and being a mum, is important to me … to have something in common with other students (Connie).

If I wanted to go to the bigger universities…and really be a proper student… I should have done that at 18 … I have to put being a mum and wife first (Amita).

These extracts illustrated the added influence of gender roles and age over decision-making. Decision-making comprised weighing up risks and strategies to mitigate financial and emotional costs and family responsibilities, which shaped their experiences. Although they exercised agency in that they had chosen to return to education, they assessed risks and made semi-rational HE choices, yet these choices were structurally constrained. These constraints arguably contribute to the reproduction of social order and class structures.

Choices and sense of belonging

The women’s practice of decision-making was shaped by their understanding of who they were and their place in the field of education. Sian (aged 48) lived locally with her husband and three teenage children. She decided to continue her studies at Purple College’s HE in FE provision. Her decision-making was partly a process of self-exclusion based on her awareness of not being a traditional student:

I decided it would be safer to stay here [at Purple College’s HE in FE provision]because I know the college, and there will be more people like me on the foundation degree so I am more likely to keep up (Sian).

I also applied for Bachelor’s Degrees [at the post 92 university] …had to decide whether to take a big step and go somewhere higher up and different … risk being out of place and it all being above my head in different ways (Sian).

No, I didn’t even apply to [Russell Group University]. It’s not for me, it’s too academic and posh there [laughs] (Patsy).

I don’t feel like a proper student, I feel like I will be pretending when I go to university (Connie, aged 47, single mother).

I liked the look of [Post-92 university] more than [Russel Group University] because it seemed to suit me more; the students looked more down to earth and the people on the virtual tour seemed more casual. The other university was way out of my league (Evie, age 27, living with her parents).

I only applied to [Post-92 University] because there’s more of a mixed bag of students like me … those of us who left it a bit late to go and not grade A students, [pause] and poor [laughs] (Patsy).

Making choices based on their familiarity is linked with the concepts of habitus and field. How these women understood their positionings with other students and universities was informed by their existing habitus, it was how they made sense of their options. Sian originally wanted to train as a social worker but a past criminal conviction due to fraudulent benefit claiming prevented her. Sian described her Play-Doh model () as depicting hand-cuffs with a ‘big red no’ over them:

…my criminal conviction which keeps my university options hand-cuffed… my crime was due to being a victim of poverty… sadly [Russell Group] university isn’t a place for the likes of me (Sian).

It also informed Sian’s sense of not belonging:

The fact I wouldn’t be offered a place to do social work…because of my conviction … No point in applying there…they wouldn’t want a criminal from the local estate walking around now would they? [laughs] (Sian).

I’m looking forward to [Post-92 university], I know that the nursing degree there attracts more students like us (Connie, age 47).

I may have to learn to talk posh

Whilst some of the women’s perceptions of fit deterred their applications to certain universities, others formulated strategies to adapt to a middle class university culture. Edie, a 45-year-old student, had applied to the Russell Group University to study psychology:

I won’t be a typical student up there … like the ones who hang out in the library and can easily write big essays in like two hours… who talk like the queen [laughs] (Edie).

I look forward to meeting new people and developing myself in all ways … I will just have to pretend to talk and dress posh and make friends that way [laughs] (Edie).

During one of the focus groups, two friends, Elsie and Betty, provided further insight into the women’s perceptions of class. Elsie (aged 47) chose to study psychology at the Post-92 university. Her friend, Betty (aged 44) was staying at Purple College’s HE provision. Both students constructed Elsie’s place at the Post-92 university in relation to their class positions. Betty described herself as ‘staying put’ and referred to Elsie’s impending move as ‘going up in the world’. They discussed moving back and forth between class identities:

Elsie - I’ve always seen myself as working class. Even if I graduate and earn megabucks, I will also be me. I’m not posh or snobby [laughs].

Betty- But you will have to talk posh when you graduate when you become a professional psychologist, or therapist or whatever you become [laughs].

Elsie- Yeah [laughs] and dress smart and pretend to be all posh and professional when I finally make it and get my career job [laughs].

Betty - You will be upper class Dr Elsie psychologist boss by day and normal Elsie by night [laughs].

Elsie - I will indeed [winks at Betty] … nah, I will always be working class. I’m proud to be that … university won’t change me in that way, I’m too old to change who I am.

Betty – As long as you don’t forget me once you’ve gone up on the world [laughs].

Impact of significant others

Access teachers were significant to university decisions. This was important because most of the women were first among friends and family to go to university:

My friends just don’t get it … it has made me question what I’m doing … if it wasn’t for [biology teacher] who was also my tutor telling me I can do this and building my confidence, I wouldn’t have persevered (Connie).

Inside I had a drive to be a mental health nurse, so I applied, but a number of times during the year … I just questioned whether I would make it at university. It was such a big thing for me … I don’t really know anyone who has been to university … my tutor wouldn’t let me give up, though (Charley, aged 47).

Wilma (aged 31), commenced the Access course following a period of homelessness. She had achieved a high number of distinctions in her assignments and hoped to study law:

My perspective of [Russell Group University] was that it wasn’t for me …too posh and normal people like me don’t make it … you know, average state school people, not academic … I wouldn’t get in (Wilma).

I wasn’t sure … I spoke to [tutor] who gave me this talk about imposter syndrome … she said the only thing stopping me was my self-doubt and wonky assumptions about university (Wilma).

She made me look at it through entry requirements rather than my background when considering the types of people who go there. She said I would be like other students in terms of grades and ability and would make friends on this basis (Wilma).

I was so shocked to get an offer… me at [Russell Group] university. It’s so posh there, like Hogwarts … and I know I won’t get top marks like the others will, but I will give it my hardest try (Wilma).

…just being offered a place is just fantastic, unexpected. My mum wanted to print out the email offer and frame it on the wall [laughs]. It’s not something that happens every day (Wilma).

My model shows me with the email in a frame. That email could be the moment my life changed forever. I’ve put bug eyes on my model to depict how my eyes have been opened, and my mind changed about me being able to go to [Russel Group] university, that I will sit amongst other students and I can see and read the same subjects as them (Wilma).

Moving into an elite HE sphere, whose intake is disproportionately dominated by students from higher socio-economic backgrounds, meant that Wilma saw herself as entering a different environment (field) with different rules of the game. Wilma’s teacher encouraged her to challenge habitual assumptions and not discount the Russell Group University. She challenged the trend of non-traditional students being less likely to enter elite universities.

Wilma’s story highlights the significant role Access to HE teachers can play in the widening participation agenda. They prepare mature students academically and can also shape their aspirations and beliefs. Importantly, Connie, Charley and Wilma’s teachers encouraged them to see they too were capable of progressing to university and were equally entitled.

Using Bourdieu’s concepts as a lens through which to analyse and understand the women’s sense of fit and beliefs about university types which led to their HE decision-making practice, enables a more nuanced understanding of education as a social space, and how individuals are positioned within it. The concept of habitus and capital enables an analysis which goes beyond a structure versus agency approach. If habitus is shaped and reproduced through past and present actions and decisions it, therefore, orientated these women’s HE decisions rather than wholly determining them.

Conclusion

This paper has brought to light the nuances of HE decision-making for a group of mature students. It has highlighted the classed nature of their choices. This contributes to discussions relating to widening participation because it explicates their classed assumptions which made decision-making more complicated and restricted. These are related to their sense of fit. Seeking a place where others ‘like them’ was significant to their decisions. The narratives presented in this paper suggest these students were aware of their class positions, and some emphasised their pride and desire to remain working class.

These decision-making experiences reveal important causes for concern, particularly regarding perceptions of class position being synonymous with academic ability. Non-traditional status lowered academic aspirations and expectations of themselves. Perceptions of HE being a middle class field led to some excluding themselves from certain universities. They lacked embodiment or a ‘feel for the game’. The women’s stories of their HE decision making reflects the relational nature of field-capital and habitus and the role that this relation plays for social reproduction. Their choices were shaped by class-based power relations, existing hierarchies, and symbolic dimensions of the UK system of HE, that interplay with individual social backgrounds and drive different choices. It was the women’s class-based practicalities and perceptions of their sense of fit that significantly influenced their ‘choice’ of HEI. However, Access to HE course teachers challenge embedded habitual ways of thinking and practice and raise self-efficacy.

This paper contributes to the research on social reproduction in HE informed by the theoretical work of Bourdieu (Citation1984, Citation1986, Citation1997). It evidences the continued interplay between agency, circumstance and social structure as central to understanding decision-making. The women’s class positions motivated their return to education. Their actions opened up the potential for upward social mobility. Despite this, their stories document the complicated ways their class-conditioned perceptions, dispositions, capital, and responsibilities (intersected with age and gender) structured their choices. Their sense of place, and feelings of fit - their habitus – were influential to their HE destination outcomes. This further evidences how habitus is a system of dispositions that reinforces itself; these students discounted some options due to their perceived lack of fit, although some strategised how they would adapt to fit in. Pre-existing structures shaped, and were reinforced by the women’s dispositions towards HE. Understanding these dynamics can provide insights into how educational inequalities are reproduced and sustained, and why participation in HE has not widened enough.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abrahams, J., and Ingram, N., 2013. The chameleon habitus: exploring local students’ negotiations of multiple fields. Sociological research online, 18 (4), 213–226.

- Atherton, G., 2017. No access to higher education: understanding global inequalities (G. Atherton, Ed.). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ball, S., et al., 2002. Classification’ and “Judgement”: social class and “cognitive structures” of choice of higher education. British journal of sociology of education, 23 (1), 51–72.

- Baker, Z., 2019. Priced out: the renegotiation of aspirations and individualized HE ‘choices’ in England. International studies in sociology of education, 28 (3-4), 299–325.

- Basit, T., and Tomlinson, S., 2012. Social inclusion and higher education. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Bochner, A., and Herrmann, P., 2020. Practicing narrative inquiry II: making meanings move. In: Patricia Leavy, ed. The Oxford handbook of qualitative research. 2nd ed. Oxford Handbooks.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Boliver, V., 2013. How fair is access to more prestigious UK universities? The British journal of sociology, 64 (2), 344–364.

- Boliver, V., and Wakeling, P., 2016. Social mobility and higher education. Encyclopedia of International Higher Education Systems and Institutions, 1–6.

- Bolton, P. (2024). Higher education student numbers (House of Commons Library research briefing 7857). https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7857/CBP-7857.pdf.

- Browne, J. (2010). Securing a sustainable future for higher education. An independent review of higher education funding and student finance (the Browne Report). www.independent.gov.uk/browne-report

- Bourdieu, P., 2010 Distinction: a social critique of the judgment of taste. Oxon: Routledge, Kegan and Paul

- Bourdieu, P., 1986. The forms of capital. In: J. G. Richardson, ed. Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 241–258.

- Bourdieu, P., 1997. The forms of capital. In: A. S. Halsey, A., Lauder, H. Brown, P. and Wells, ed. Education, culture, economy, society. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P., and Wacquant L. J. D. 1992. An invitation to reflexive sociology. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Bradley, H., Abrahams, J., Bathmaker, A., Beedell, P., Hoare, T., Ingram, N., Mellor, J., & Waller, R. (2013). Paired peers project. https://www.bristol.ac.uk/spais/research/paired-peers/

- Braun, V., and Clarke, V., 2022. Thematic analysis a practical guide. California: Sage.

- Brine, J., and Waller, R., 2004. Working-class women on an access course: risk, opportunity and (re)constructing identities. Gender and education, 16 (1), 97–113.

- British Education Research Association (BERA). (2018). Ethical guidelines for educational research. 4th ed. https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018-online

- Busher, H., and James, N., 2019. Struggling to become successful learners: mature students’ early experiences of access to higher education courses. Studies in the education of adults, 51 (1), 74–88.

- Busher, H., and James, N., 2020. Mature students’ socio-economic backgrounds and their choices of access to higher education courses. Journal of further and higher education, 44 (5), 640–652.

- Callender, C., and Jackson, J., 2008. Does the fear of debt constrain choice of university and subject of study? Studies in higher education, 33 (4), 405–429.

- Crozier, G., et al., 2008. Different strokes for different folks: diverse students in diverse institutions - experiences of higher education. Research papers in education, 23 (2), 167–177.

- Croxford, L., and Raffe, D., 2014. Social class, ethnicity and access to higher education in the four countries of the UK: 1996–2010. International journal of lifelong education, 33 (1), 77–95.

- Crozier, G., Reay, D., and Clayton, J., 2019. Working the Borderlands: working-class students constructing hybrid identities and asserting their place in higher education. British journal of sociology of education, 40 (7), 922–937.

- Davies, P., and Williams, J., 2001. For me or not for me? Fragility and risk in mature students’ decision-making. Higher education quarterly, 55 (2), 185–203.

- Dearing, R., 1997. Higher education in the learning society: report of the National Committee of Inquiry into Higher Education. London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office.

- Department for Business Innovation and Skills (DBIS), 2011. Higher education: students are the heart of the system. London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office.

- Department for Business Innovation and Skills (DBIS), 2016. Success as a knowledge economy: teaching excellence, social mobility and student choice. London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office.

- Department for Education (DfE), 2023. Participation measures in higher education, academic year 2020/21. https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/participation-measures-in-higher-education/2020-21.

- Egerton, M., and Halsey, A.H., 1993. Trends by social class and gender in access to higher education in Britain. Oxford review of education, 19 (2), 183–196.

- Espinoza, O., et al., 2023. The relationship between class-based habitus and choice of university and field of study. British journal of sociology of education, 44 (4), 649–668.

- Farhan, I., & Heselwood, L., 2019. Access for all? The participation of disadvantaged students at elite universities. https://reform.uk/publications/access-all-participation-disadvantaged-students-elite-universities/.

- Fraser, L., and Harman, K., 2019. Keeping going in Austere times: The declining spaces for adult widening participation in higher education in England. In: E. Boeren, and N. James, eds. Being an adult learner in Austere Times: Exploring the contexts of higher, further and community education. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 71–95.

- Friedman, S., 2016. Habitus clivé and the emotional imprint of social mobility. The sociological review, 64 (1), 129–147.

- Higher Education Statistics Authority (HESA), 2022. Widening participation: UK Performance Indicators 2020/21. https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/performance-indicators/widening-participation.

- Hubble, S. and Bolton, P. (2020). Mature higher education students in England.(Briefing Paper No. 8809). House of Commons Library, 24th February 2021. https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/id/eprint/37449/1/CBP-8809.pdf.

- James, N., et al., 2013. Opening doors to higher education: access students’ learning transitions (Final Project Report-Phase 2). Leicester: University of Leicester.

- Jones, R., and Thomas, L., 2005. The 2003 UK Government Higher Education White Paper: A critical assessment of its implications for the access and widening participation agenda. Journal of education policy, 20 (5), 615–630.

- Lehmann, W., 1969. I just didn’t feel like i fit in’: the role of habitus in university dropout decisions. Canadian journal of higher education, 37 (2), 89–110.

- Leitch, R., 2008. Researching children’s narratives creatively through drawings. In: T. P, ed. Doing visual research with children and young people. New York: Routledge, 37–59.

- Mannay, D., and Morgan, M., 2013. Anatomies of inequality: Considering the emotional cost of aiming higher for marginalised, mature mothers re-entering education. Journal of adult and continuing education, 19 (1), 57–75.

- McGrath, S., and Rogers, L., 2021. Do less-advantaged students avoid prestigious universities? An applicant-centred approach to understanding UCAS decision-making. British educational research journal, 47 (4), 1056–1078.

- Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MoH), 2019. The English Indices of Deprivation 2019 (IoD2019). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/835115/IoD2019_Statistical_Release.pdf.

- Office for Students (OFS), 2020. Mature students. https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/promoting-equal-opportunities/effective-practice/mature-students/#:∼:text=There%20has%20been%20a%20decline%20in%20the%20number,191%2C340%20in%202018-19%20%28a%2022%20per%20cent%20drop%29.

- Patfield, S., Gore, J., and Fray, L., 2023. Stratification and the illusion of equitable choice in accessing higher education. International studies in sociology of education, 32 (3), 780–798.

- Patiniotis, J., and Holdsworth, C., 2005. ‘Seize that chance!’ Leaving home and transitions to higher education. Journal of youth studies, 8 (1), 81–95.

- Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA). (2021). Access to HE. Key Statistics 2019/20. https://www.accesstohe.ac.uk/regulating-access/statistics

- Rainford, J., 2020. Confidence and the effectiveness of creative methods in qualitative interviews with adults. International journal of social research methodology, 23 (1), 109–122.

- Rainford, J., 2023. Are we still “raising aspirations”? The complex relationship between aspiration and widening participation practices in English higher education institutions. Educational review, 75 (3), 411–428.

- Reay, D., 2018. Working class educational transitions to university: The limits of success. European journal of education, 53 (4), 528–540.

- Reay, D., Crozier, G., and Clayton, J., 2009. “Strangers in paradise”?: Working-class students in elite universities. Sociology, 43 (6), 1103–1121.

- Reay, D., David, M. E., and Ball, S., 2005. Degrees of choice: social class, race and gender in higher education. Staffordshire: Trentham Books.

- Reay, D., 2021. The working classes and higher education: Meritocratic fallacies of upward mobility in the United Kingdom. European journal of education, 56 (1), 53–64.

- Russell, S. L., 1973. Adult education a plan for development. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

- Savage, M., 2015. Social class in the 21st century. London: Pelican.

- Scandone, B., 2022. ‘I don’t want to completely lose myself’: social mobility as movement across classed, ethnicised, and gendered spaces. Sociological research online, 27 (1), 172–188.

- Scanlon, M., et al., 2019. ‘How are we going to do it?’ An exploration of the barriers to access to higher education amongst young people from disadvantaged communities. Irish educational studies, 38 (3), 343–357.

- Stenhouse, R.L., and Ingram, N., 2024. Private school entry to Oxbridge: how cultural capital counts in the making of elites. British journal of sociology of education, 1–17.

- Stephenson, J., 2018. Scrapping of bursary partly behind drop in mature students. Nursing Times. https://www.nursingtimes.net/news/education/scrapping-of-bursary-partly-behind-drop-in-mature-students-06-07-2018/.

- Social Mobility Commission (SMC), 2022. SMC response to the levelling up the United Kingdom White Paper. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/smc-response-to-the-levelling-up-the-united-kingdom-white-paper.

- Sullivan, A., Heath, A., and Rothon, C., 2011. Equalisation or inflation; social class and gender differences in England and Wales. Oxford review of education, 37 (2), 215–240.

- Tett, L., 2004. Mature working-class students in an “elite” university: discourses of risk, choice and exclusion. Studies in the education of adults, 36 (2), 252–264.

- UCAS, 2021. Who are mature students? https://www.ucas.com/undergraduate/student-life/mature-undergraduate-students#who-are-mature-students.

- Woodward, P., 2020. Higher education and social inclusion: continuing inequalities in access to higher education in England. In Handbook on promoting social justice in education (pp. 1229–1251).

- Young, M., 1958. The Rise of the Meritocracy 1870–2033: an essay on education and society. London: Thames and Hudson.