Port cities are hip

The multifaceted structure of port cities, their global function, their distinctive appearance, and their storied history attracts the interest of a broad range of people. At least that is what the recent proliferation of workshops, sessions, and conferences on the theme of port cities suggests. These events mostly fall into two categories: those organized by professionals of ports and technology who seek to improve the functionality of the port and academics from social science and humanities fields who explore a broad range of port city-related developments.

Two commonalities stand out among the conferences from the last three years: first, both sets of conferences explore interrelation of port and city; second, a new and strong interest in history on the side of the port developers matches an increase of history-oriented events among academics. Those organized by professionals of ports and technology seek to improve the functionality of the port and academics from social science and humanities fields who explore a broad range of port city-related developments.

Nonetheless, the two groups pursue their interests independently, for the most part. Planners, and particularly those who double up as planning historians, have an opportunity to take the lead in this field. This article identifies six domains in which planning history could do more: the multiple and overlapping scales of port and city, the actors and their networks, the different temporalities of the port, local cultures, path dependence, and finally the study of port cities’ surprizing resilience.

In conclusion, the article argues that research on the history and culture of port cities can both strengthen the future development of ports and help sharpen the theoretical and methodological focus of planning history. This may push them to integrate the two research perspectives and potentially collaborate with social scientists and humanists, including historians, who have taken a broader and more critical perspective towards port and city development. A systematic approach to port cities would provide scholars with a strong framework to compare and contrast case studies in planning history. Following a brief overview of recent professional and academic conferences and of historical approaches, this article investigates and reflects on the role that planning history can take in the study of port cities.

Conferences on port cities

Port Authorities, maritime logistics, technology companies, and engineering departments at major universities have long studied port efficiency, safety, and energy. Recent interest in smart ports and the port city more broadly suggests a growing awareness of the ecologies in which ports function. Ports are important economic drivers for cities and regions, well beyond their often secluded and fenced-off locations. Their impact on land and sea, on people in cities and rural areas is extensive, particularly if shipping and maritime headquarters are also located in the city. Their development requires insight from a broad range of public and private actors with stakes in the economic health of the port, its logistics and transportation needs, and its environmental impact on urban and maritime areas. The economic benefits of the port often spread beyond the port, whereas the negative impacts are local. Transportation, logistics, and safety issues cannot be solved in the port area alone. Environmental issues – the pollution of air, soil, and water – that arise under climate change are equally relevant for the urban neighbour and the larger region, so they require collaboration.

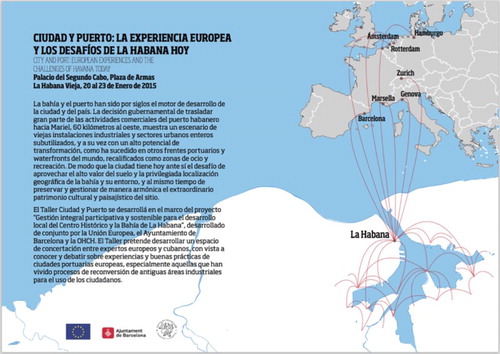

Several port cities, such as Split, Barranquilla, and Havana, have hosted conferences organized by local universities and administrations, bringing together planners, practitioners, and scholars to discuss experiences and challenges for the future. The University of Split organized the international roundtable Urban Economics Historic Port Cities in 2013 in the context of UN Habitat discussions.Footnote1 The Congreso Internacional Portuario, Maritimo y Fluvial, organized by the Universita Autonoma of Baranquilla in 2014, aimed to promote the city's role as a strategic centre in the Caribbean.Footnote2 In 2015, an event in Havana brought several practitioners and academics to the Cuban capital to discuss experiences with the redevelopment of former port areas notably in Hamburg, Marseille, Amsterdam, and Rotterdam, to establish a baseline for participatory and sustainable development of the centre and Bay of the Cuban capitalFootnote3 ( and ).

Figure 1. Conference Participants in Baranquilla. Source: http://www.uac.edu.co/noticias-economicas/item/1878-barranquilla-hacia-una-ciudad-puerto.html.

Figure 2. City and port: poster for the conference held in Havana in 2015. Source: http://www.planmaestro.ohc.cu/recursos/papel/eventos/ciudadypuerto.pdf.

Major organizations are aware of both the need for an integrated approach towards port and city and a historical awareness, as demonstrated in a publication on the ‘Competitiveness of Port Cities’ launched at a conference of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 2013 and published in 2014.Footnote4 (The OECD runs its own Port Cities Programme, created in 2010, developing policies for national, regional, and local governments.) The publication acknowledges that the positive effects of the port spill over to locations beyond the city, while most of the negative effects are concentrated in the port city, and it asks how negative port impacts can be mitigated.Footnote5 Port authorities are thus in search of an integrated approach to improve the relation between port and city. They also acknowledge the historical relationship between port and city: ‘Ports and cities are historically strongly linked, but the link between port and city growth has become weaker’.Footnote6 This statement signals awareness, if not a need, for further engagement with historical information.

The reference to the integration of port and city is striking, but not unique. Professional institutions, port authorities, and governments have opted to collaborate more closely to foster regional visions and large-scale planning – that is, planning that takes into account more than the functionality of the port. They also shape research and collaborations through their conferences and publications. The Association Internationale Ville et Ports (AIVP), an organization that brings together public and private actors involved in port cities, has held annual conferences for 25 years on the theme of port and cities. At its meeting 2014 in Durban, diverse actors presented their plans to improve port business and life focusing on the Smart Port City, defined by Paolo Bosso, a journalist and editor at Informazione Marittime, as creating port cities where a flourishing (port) economy coexists with liveable urban areas ().Footnote7 The AIVP conference in Dublin in May 2015 proposed a new theme and studied the ‘Working Waterfront: A Port-city Mix in Progress’.Footnote8 AIVP research and these conferences resulted in a guidebook on how to ‘Plan the city with the port: guide of good practices’, documenting the professional interest in connecting port and city.Footnote9

These associations also pay attention to historical patterns in multiple ways. Heritage issues and the redevelopment of abandoned historic waterfronts may be the main focus, but research on the history of those areas and port cities more generally is also included. The Asociación para la Colaboración entre Puertos y Ciudades [Association for the Collaboration between Ports and Cities] (RETE) established in 2001, for example, includes historical articles in an online magazine called Portus that documents the interests of the ports and cities.Footnote10

The dual interest in port cities and historical themes, often connected to heritage issues, also resonated in several other events. The European Maritime Days, established in 2008 by the European Commission, focused on increased sustainability during its event in Piraeus in 2015.Footnote11 The Marinescape Forum, held in conjunction with the Maritime Days, similarly sought to integrate ‘social, economic, and environmental interactions [ … ] into effective policies promoting the sustainable development’ of the Mediterranean.Footnote12 Conference presentations considered the future as well as issues of heritage preservation, a necessary approach for the study of the Mediterranean and its coast that has long been built around trade. The historical dimension of water as the factor that binds together people, nature, and diverse artefacts of engineering and construction is the focus of the International Water History Association a group that holds annual meetings to promote a stronger relationship between scholars of water history and practitioners in the field, that convened in Delft in 2015, but the theme of port cities was surprisingly largely absent.Footnote13

As professional conferences engage with territories beyond the port, and times beyond the present and future, academics from different disciplines employ theoretical and methodological approaches beyond their traditional realms. Economic geographers and planners are closely connected to the world of port professionals, as their participation in professional conferences and publications shows. César Ducruet is perhaps the most striking example of a scholar close to practice. He participated in the OECD research and heads the World Seastems research project.Footnote14 In his research on maritime flows between 1890 and 2004, based on the Lloyd's Voyage Record (information on ocean-going ships collected for the Lloyd's marine insurance company), he uses the tools of an economic geographer to study historical flows. A conference organized in the context of the Seastems research brought together a diverse array of scholars. The resulting publication (forthcoming with Routledge) was trimmed to a more disciplinary perspective: it includes historical data but focuses on network analysis of transport systems.Footnote15

The network approach of economic geographers provides an intriguing framework for the detailed and place-specific investigations of historians. Several conferences integrated the visualizations and mappings of economic geographers with historical and archival research, social questions, and cultural investigations, such as the sessions on Port Cityscapes organized by scholars from various disciplines, including planners, at the meeting of the Association of American Geographers in 2013 (documented in a conference report).Footnote16

Planners engage with port related developments on multiple levels in their professional work as they coordinate between port, waterfront, and city. The relation between port and city is a distinctive dynamic within a complex network of goods and people, a set of specific localities with unique spatial forms. This arrangement requires a broad range of planning activities. A port shares infrastructure, housing, and leisure facilities with other public and private stakeholders in its city; port planning is closely integrated with other urban developments, big and small, past, present, and future. Many planners participate in the professional conferences mentioned above, but their own yearly conferences (like the Association of European Schools of Planning meetings in Utrecht 2014 and Prague 2015, and the American Planning Association conference in Seattle in 2015) only had a few papers that touched upon the theme of port cities.Footnote17

Scholars from the social sciences and humanities are engaging in innovative ways with port cities as a topic for research, stressing the multiple social, political, and cultural aspects of port cities in addition to their economic role. Their interest in issues of migration, ethnicity, and identity (or image construction) is often related to ethical questions; it complements the scope of the port professionals. Some meetings have addressed port city issues through the lens of sociology or art history: one session explored issues of Social and Spatial Fragmentation at the conference of the Research Committee 21 (RC21) on Sociology of Urban and Regional Development (part of the International Sociological Association), while an entire conference was organized in art history on images and imaginaries of port cities of Atlantic and Mediterranean Europe from the eighteenth to the twenty-first century.Footnote18 But these are exceptions and remain largely disconnected from the professional discussions that focus on the economic welfare of the port. In a context that is divided between fields with evident practical implications and those that aim at critical investigation of port related challenges, an integration of common approaches, theories, and methodologies appears difficult.

Perhaps most striking in the multitude of conferences is the boom of events explicitly focused on the history of port cities. Entire smaller events have been dedicated to port cities, such as the conference Seaports in Transition, discussed in Planning Perspectives 2015.Footnote19 Five out of 51 sessions at the meeting of the European Association of Urban Historians (EAUH) in Lisbon in 2014 explored themes of port cities.Footnote20 Even more strikingly, the World History Association (WHA) discussed port cities in world history in a dedicated symposium in 2014.Footnote21 Some 60 scholars convened to discuss social and cultural aspects that are largely absent or only discussed in passing in the professional conferences. The geographical range was broad with an astounding number of papers on Asian ports and Spanish colonial networks; very few scholars, however, touched upon urban planning themes. Specific topics included the impact of Napoleonic invasion and blockade on port cities, crime and lawlessness, religious exchanges in Asian port cities, issues of piracy, commerce and migration, colonialism and colonial empires, multi-ethnic communities, migration, ports as information centres, or ports and culture (including sports) ().

Figure 4. Poster of the 2014 conference of the EAUH where numerous panels addressed issues of port cities.

But the study of port cities has great potential for comprehensive and comparative investigation, especially through the lens of planning history, and merits a collective effort. The next section of the text proposes some crosscutting research themes, established and emergent, for planning history, and can bring existing research on individual port cities into a broader context.Footnote22

Planning history and future research on port cities

The interrelationship between ports and cities has a long and changing history of planned and unplanned intersections and ports cannot function independently of their urban neighbours and larger regions, as the professional conferences have shown. Even though port and city today are disconnected spatially, working ports have an increasing influence on growing metropolitan areas and their regions, while local authorities have incorporated former port areas on the waterfront in the urban fabric. The port no longer serves as a major employer for large parts of the population, but still citizens must deal with the port, seaways, environmental destruction, and the construction of transportation infrastructure and new logistics centres, just as they have learned to engage with ports through time. Planning has an important role to play in connecting port and city, and historical analysis can help balance the different interests and goals.

Planning is a major factor in all of these developments, but little research is done systematically; those who focus on the history of ports rarely think of planning themes. At the same time, those who focus on planning history rarely use the lens of port cities and their networks. Yet the long-standing history and explicit culture of port cities makes them an appealing research focus for planning history, as it provides a unique opportunity for comparative research of interconnected cities. The fortunes of these port cities are interdependent, for they all depend on the same complex network of goods and people, even as they are located in many geographical, political, and economic settings. This concurrent competition and collaboration makes port cities ideal for comparative research projects. (Other systems of transport and commodity flows – lake and river ports, airports, and international rail termini – also have this dynamic of similarity and difference, but they do not have the same historical and cultural force as port cities.)

Taking the port city itself as a topic for comparative research, scholars working in the field of planning history might well identify a range of themes to advance research methodologies and establish new avenues and approaches. The following part of the article proposes that scholars continue to focus on the multiple and overlapping scales of port and city, their actors, and wide-ranging networks, themes that have already received quite some attention. It also argues that economically successful ports and port cities, often with long histories, promote a port culture encompassing not only port elites but also regular citizens and even visitors. Planning for the port thus also means attention to historical artefacts and heritage spaces that are a key element in identity and image construction and thus to port cultures. Integration of historical buildings and industrial structures demonstrates the importance of temporalities in parallel speeds of different types of people: those involved in running the port, and those working there, or those living next to it; and the long-term dimensions of the speed in transforming the built environment associated with the port, or with the city. The intersection of diverse groups of people over time has shaped port cultures and decision-making processes, creating so-called path dependencies. Together these elements have helped build port cities’ surprizing resilience. Research into these different themes will help us to better understand port city resiliency and to develop best practice examples; such work may also enrich ongoing attempts to sharpen the theoretical and methodological focus of planning history as well as discussions on the actual functioning of the port in relation to its surroundings.

Spatial scales

What scales matter to planning history of port cities? Ports and the cities that host them are subject to many overlapping spatial demands. International (for example European), national, regional, metropolitan, and local plans shape the development of ports and cities alike. Shipping often cuts through these scales and follows a corporate logic bound by economic rather than spatial planning; economic geographers are tracing these patterns. Port cities can serve as a lens for comparing and contrasting planning histories in multiple locations that participate in the same network.Footnote23 So far, in the amount of work that does exist on port city planning, authors have focused on select cities or aspects, examining the most striking examples and largest scales, notably the planned revitalization of former inner-city waterfronts after the departures of ports to the outskirts of cities.Footnote24 But other scales of planning have been explored less: many stories of how new container ports on urban outskirts and logistics centres in the hinterland have reshaped individual cities and rural areas remain yet to be told. The logistics revolution and the expanding transportation needs affect the metropolitan areas, and citizens started to critique the impact of the port and its use of the common transportation network on the environment and on liveability. There clearly is a need for a planning history that explores the competing needs of port and city, and how planning has addressed them in different places around the world.

Stakeholders

What people matter to planning history in port cities? Through case studies, we can see that port cities distinctively attract a range of actors with varying degrees of (planning) power and funding, who promote specific interests or claim select spaces and affect planning processes in faraway locations.Footnote25 The respective impact of private and public stakeholders – multinationals, city, regional and national governments, and civic associations – is a recurrent theme in both new and old planning histories of port cities and merits systematic analysis. Thus, it would be worthwhile to explore these dynamics from a comparative perspective. How have multinational companies, including container-shipping giants (Maersk, CMA CGM, Hapag), port operators (DP World, APM Terminals, Eurogate), and oil companies (Shell, Texaco, Exxon) shaped port and city planning in different places? Even though these corporations don't have formal planning powers, their size, financial and international power allow them to influence plans and planning mechanisms at multiple levels. Some conference discussions touched upon the theme of diverse actors, their networks, and constellations, in regard to port city development, but the theme has not yet been explored systematically in planning history.

Temporalities

Temporalities may be an interesting way to think about the particularities of the port and its impact on planning. Port, waterfront, city, region, and nation are different overlapping spatial entities with a range of actors and planning histories; they also exist in evolving time regimes that relate in multiple ways to the occupation of space and the functioning of the port.Footnote26 Time matters to planning and planning history in multiple ways. For one, it has a short-term dimension, of parallel speeds of humans (for example day-night or seasonal) and of machines and their interaction. It also has long-term dimensions: consider the relationship between fast-paced changes in networks of actors in shipping, compared to the slow pace of change in physical and even social and political structures. A better understanding of these evolving interactions and the role of planning within them can promote understanding of the relationship between port and city over time and facilitate the integration of buildings and the heritage of the past. Urban planning can play a major role in linking and balancing the different speeds of port and city transformation, and planning history can explore that relationship. In a publication from 2013, Dietrich Henckel with Susanne Thomaier argued that each city has its own rhythm.Footnote27 Some port cities change the built environment faster than others and grow, and others react slower and lose a working port or fail to revive a waterfront. A rapid implementation of planning for the port can create inequalities for local citizens. Greater acknowledgement of temporalities in historical analysis and in planning may improve the local climate and port culture, and, therewith, the actual functioning of the port in relation to its surroundings. Surprisingly, little has been said about this theme in professional conferences, whether of those interested in designing the future or those discussing the past and present from an analytical point of view.

Port cultures

The speed of transformation captured through the temporalities approach is also part of the port cities culture, a shared collective local mind-set, long-standing and on-going, that supports port development, specific to each city, but in its essence similar to that of the whole group of port cities. This atmosphere of support for port development among urban elites, workers, and citizens has traditionally evolved as part of the intimate interconnection of port and city; this culture is inscribed in planning practices, governance, and cultural productions. It is connected to historic maritime structures and traditions, and it facilitates local acceptance and promotion of large-scale changes in and around the port, even those that might conflict with the values and lifestyle of some populations. At times, it actually celebrates results of destruction and rebuilding, interpreting them as a particular capacity to overcome adversity and to engage in transformation. With UNESCO selection of Hamburg's unique warehouse and office district as a world heritage site in 2015, locals ultimately accepted, even supported and praised, urban redevelopment including the displacement of citizens. Heritage is the expression of local cultures and it is a consistent theme both in the professional and the academic conferences. A topic yet to be explored is how increasing migration and (super)-diverse populations will interact with existing traditions. Decisions on what to preserve and what to keep and who to bring into the neighbourhood are part of planning decisions.

Path dependencies

Path dependency is a method to better understand by whom and how culture is constructed, how and why temporalities matter. Scholars working in the field of planning history might well describe which port cultures are written into planning practice through the concept of path dependency. Planning historian Andre Sorensen laid the foundation for this more theoretical approach towards planning history, proposing a historical institutionalist research agenda.Footnote28 Using the port/city interaction as a research theme may further focus this approach, as port cities are a specific type of city characterized by rapid change and a high capacity for adaptation. Path dependency would also provide a framework for comparative research of ports and cities in multiple regions of the world, helping to bridge research in different political, economic, social, and cultural settings. Such historical analysis can help us understand earlier typologies and development patterns; it allows for contextualized comparison, and avoids uninformed copying and pasting of designs of the past into current cities. It provides planning historians an opportunity to identify critical junctures in previous decades and to understand the underlying political, social, and cultural context of contemporary redevelopment.

Resilience

The result of networks of actors and cultures and decisions made at multiple junctures is resilience. The common need to adapt to shipping needs makes port cities models for other cities and objects for the study of their (planning) history. This repeated adaptation may also be a reason for their surprisingly strong resilience, defined here as a capacity to quickly recover from diverse shocks. The study of resilience in port cities brings together two vibrant strands of historical analysis that are relevant to planning history: the study of ports and that of disasters. Many contemporary problems have historical precedents, and historical analysis can provide planners with a broader understanding of them. That is, studying earlier cases – of rising sea water levels and of urban responses to it, of adaptations to migration and demographic transformation, of port cities’ responses to major economic shifts, and of new societal challenges including terrorism – may help contextualize current risks and potential responses for planners. In short, we need multiple histories with diverse interpretations – histories, not just of planner-heroes, but of complex systems of scales, actors, temporalities, cultures, path dependencies, and resilience, for example through the lens of port cities.

Conclusion: what is next?

The number of conferences dedicated to the history of port cities, and the diversity of their approaches, demonstrates the richness of the field of study and the opportunities for further multidisciplinary and historical engagement. Academic conferences tend to address a broad field of questions, something that professional conferences are aiming for. Research on the history of port cities can both strengthen the future development of ports and contribute to ongoing attempts to sharpen the theoretical and methodological focus of planning history.

Several conferences in 2015 and 2016 offer further opportunities to discuss port cities. The SACRPH meeting in Los Angeles in 2015, the EAUH Helsinki 2016, and the IPHS in Delft 2016 comprise sections on the historical development of active ports in the face of changing global networks, technologies, and political systems. These events include a surge of novel insights and new approaches, methodologies, theories, case studies, and scholars from around the globe. Looking at the big picture, we can imagine port cities research that includes visualizations of networks of shipping and trade, reference maps for scholars who study specific localities, their spaces, actors, path dependencies, cultures, and resilience.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on the contributor

Carola Hein is Professor and Head, Chair History of Architecture and Urban Planning. She has published widely on topics in contemporary and historical architectural and urban planning – notably in Europe and Japan. Among other major grants, she received a Guggenheim Fellowship to pursue research on The Global Architecture of Oil and an Alexander von Humboldt fellowship to investigate large-scale urban transformation in Hamburg in international context between 1842 and 2008. Her current research interests include transmission of architectural and urban ideas along international networks, focusing specifically on port cities and the global architecture of oil. She serves as IPHS editor for the journal Planning Perspectives and Asia book review editor for the Journal of Urban History. Her books include: The Capital of Europe (2004), Port Cities: Dynamic Landscapes and Global Networks (2011), Brussels: Perspectives on a European Capital (2007), European Brussels. Whose capital? Whose city? (2006), Rebuilding Urban Japan after 1945 (2003), and Cities, Autonomy and Decentralisation in Japan. (2006).

ORCID

Carola Hein http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0551-5778

Notes

1. International Roundtable Urban Economics, Historic and Port Cities, 12–15 October 2013, https://www.efst.hr/mosst/ (accessed 9 August 2015).

2. Barranquilla hacia una ciudad puerto. 29–31 October 2014, http://www.uac.edu.co/noticias-economicas/noticias-administracion-maritima-y-fluvial/item/1878-barranquilla-hacia-una-ciudad-puerto.htmll (accessed 9 August 2015).

3. Ciudad Y Puerto: La Experiencia European y los Desafíos de la Habana hoy [City and Port: European Experiences and the Challenges of Havana Today], 20–23 January 2015, http://www.planmaestro.ohc.cu/recursos/papel/eventos/ciudadypuerto.pdf (accessed 9 August 2015).

4. The Competitiveness of Global Port Cities, 8 December 2014 http://www.oecd.org/gov/regional-policy/Competitiveness-of-Global-Port-Cities-Synthesis-Report.pdf (accessed 9 August 2015).

5. Koningkrijk der Nederlanden, OECD Port-Cities Conference http://oeso.nlvertegenwoordiging.org/nieuws/2013/sept-2013/oecd-port-cities-conference.html (accessed 9 August 2015).

6. Koningkrijk der Nederlanden, OECD Port-Cities Conference http://oeso.nlvertegenwoordiging.org/nieuws/2013/sept-2013/oecd-port-cities-conference.html (accessed 9 August 2015).

7. Paolo Bosso, The Port City of Tomorrow Will Be Smart, http://citiesandports2014.aivp.org/interventions/orales/la-citta-portuale-di-domani-sara?lang=en (accessed May 3, 2015).

8. AIVP, Working Waterfront, http://www.aivp.org/dublin/en/ (last accessed 9 August 2015).

9. AIVP, Plan the City with the Port.

10. RETE, Publicaciones, http://retedigital.com/publicaciones/portus/ (accessed 4 August 2015).

11. European Maritime Day, Ports and Coasts, gateways to maritime growth, 28–29 May 2015, http://www.cmcc.it/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/EMD2015-conference-programme_en.pdf, European Commission, European Maritime Day, http://ec.europa.eu/maritimeaffairs/maritimeday/en/home (accessed 9 August 2015).

12. Marinescape Forum Piraeus, http://med-ina.org/Portals/0/Uploads/NewsFiles/Marinscape_agenda_FINAL.pdf (accessed 9 August 2015).

13. International Water History Association, http://www.iwha.net/ (accessed 9 August 2015).

14. Ducruet, “The World Seastems Research Project (2013–2018).”

15. Ducruet, Maritime Networks.

16. Hein et al., “Conference Report.”

17. AESOP Annual Congress Utrecht/Delft: http://www.congrexprojects.com/aesop/programme; Prague: http://www.aesop2015.eu/; APA Seattle: https://conference.planning.org/search/?scope=program&keyword= (accessed 9 August 2015).

18. Big Ships on the Horizon and Social and Spatial Fragmentation at Home – Port Cities as Emblematic Places of Urban Transformation. RC 21 Conference in Berlin, 29–31 August 2013; Colloque international Soi, l'autre et l'ailleurs Images et imaginaires des villes portuaires de l'Europe atlantique et méditerranéenne (XVIIIe - XXIe siècles) Bordeaux, 11–12 May 2015.

19. Strupp, “Seaports in Transition.”

20. EAUH, Lisbon 2014: Sessions M28 At the Edge of the Atlantic World: Port Cities and Transcultural Change, 19th–21st centuries; M 38 Disaster and Rebuilding in Modern Port Cities; Port Cities: M44: Port Cities: Comparative Perspectives on Urban Stability and Public Safety (18th–21st centuries); S10. Gateways of Disease. Public Health in European and Asian Port Cities at the Birth of the Modern world, http://www.eauh2014.fcsh.unl.pt/index.php?conference=conference&schedConf=eauh2014&page=schedConf&op=trackPolicies (accessed 8 August 2015).

21. Symposium on: “Port Cities in World History” (World History Association, Barcelona, March 26–28. 2014); Port City Scapes (AAG, Los Angeles, 9–11 April 2013) (accessed 9 August 2015).

22. Ryckewaert, “The Ten Year Plan”; Garcia, “The Role”; also Oliveira and Pinho, “Urban Form.”

23. Hein, Port Cities: Dynamic Landscape and Global Networks.

24. Studies on waterfronts include: Bone, Bone, and Betts, The New York Waterfront; Breen and Rigby, The New Waterfront; Brown, America's Waterfront Revival; Desfor et al., Transforming Urban Waterfronts; Hoyle, “Urban Waterfront Revitalization”; Hoyle, Pinder, and Husain, Revitalising the Waterfront; Marshall, Waterfronts in Post-Industrial Cities; Meyer, City and Port; Schubert, “Ever-Changing Waterfronts”: Ware, Blue Frontiers; Sepe, “Urban History”; and Aprioku, “Local Planning.”

25. For example: Ward, “The International Diffusion”; Braudel, The Wheels of Commerce; and Konvitz, Cities and the Sea.

26. See also: Hein, “Temporalities of the Port.”

27. Henckel and Thomaier, “Efficiency, Temporal Justice.”

28. Sorensen, “Taking Path Dependence Seriously.”

References

- AIVP. Plan the City With the Port: Guide of Good Practices. AIVP, 2015.

- Aprioku, Innocent Miebaka. “Local Planning and Public Participation: The Case of Waterfront Redevelopment in Port Harcourt, Nigeria.” Planning Perspectives 13, no. 1 (1998): 69–88. doi: 10.1080/026654398364572

- Bone, Kevin, Eugenia Bone, and Mary Beth Betts. The New York Waterfront: Evolution and Building Culture of the Port and Harbor. New York: Monacelli, 1997.

- Braudel, Fernand. The Wheels of Commerce: Civilization and Capitalism, 15th–18th Century. Vol. 2. New York: Harper and Row, 1983.

- Breen, Ann, and Dick Rigby. The New Waterfront: A Worldwide Urban Success Story. London: Thames and Hudson, 1996.

- Brown, Peter H. America's Waterfront Revival. Port Authorities and Urban Redevelopment. Philadelphia, PA: University of Philadelphia Press, 2009.

- Desfor, Gene, Jennefer Laidley, Dirk Schubert, and Quentin Stevens, eds. Transforming Urban Waterfronts: Fixity and Flow. London: Routledge, 2010.

- Ducruet, Cesar, ed. Maritime Networks: Spatial Structures and Time Dynamics. Routledge, 2016.

- Ducruet, César. “The World Seastems Research Project (2013–2018).” Portus 26, November, 2015.

- Garcia, Pedro Ressano. “The Role of the Port Authority and the Municipality in Port Transformation: Barcelona, San Francisco and Lisbon.” Planning Perspectives 23, no. 1 (2008): 49–79. doi: 10.1080/02665430701738032

- Hein, Carola. Port Cities: Dynamic Landscape and Global Networks. New York: Routledge, 2011.

- Hein, Carola. “Temporalities of the Port, the Waterfront and the Port City.” Portus 29, June, 2015.

- Hein, Carola, Peter V. Hall, Wouter Jacobs, and Anne Langer-Wiese. “Conference Report: Port Cityscapes: Dynamic Perspectives on the Port–City–Waterfront Interface, Special Paper Sessions1 at the Annual Meeting of the Association of American Geographers, Los Angeles, 12 April 2013.” Town Planning Review 84, no. 6 (2013): 905–810.

- Henckel, Dietrich, and Susanne Thomaier. “Efficiency, Temporal Justice and the Rhythm of Cities.” In Space–Time Design of the Public City, edited by D. Henckel, S. Thomaier, B. Könecke, R. Zedda, and S. Stabilini, 99–118. Dordrecht: Springer, 2013.

- Hoyle, B. S., David Pinder, and M. S. Husain. Revitalising the Waterfront: International Dimensions of Dockland Redevelopment. London: Belhaven Press, 1988.

- Hoyle, Brian S. “Urban Waterfront Revitalization in Developing Countries: The Example of Zanzibar's Stone Town.” The Geographical Journal 2 (June 2002): 141–162.

- Konvitz, J. W. Cities and the Sea: Port City Planning in Early Modern Europe. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press, 1978.

- Marshall, Richard, ed. Waterfronts in Post-Industrial Cities. London: Spon, 2001.

- Meyer, Han. City and Port: Urban Planning as a Cultural Venture in London, Barcelona, New York, and Rotterdam: Changing Relations between Public Urban Space and Large-Scale Infrastructure. Utrecht: International Books, 1999.

- Oliveira, Vítor, and Paulo Pinho. “Urban form and planning in Lisbon and Oporto.” Planning Perspectives 23, no. 1 (2008): 81–105. doi: 10.1080/02665430701738081

- Ryckewaert, Michael. “The Ten–Year Plan for the Port of Antwerp (1956–1965): A Linear City Along the River.” Planning Perspectives 25, no. 3 (2010): 303–322. doi: 10.1080/02665433.2010.481179

- Schubert, Dirk. “‘Ever-Changing Waterfronts’: Urban Development and Transformation Processes in Ports and Waterfront Zones in Singapore, Hong Kong and Shanghai.” In Port Cities in Asia and Europe, edited by A. Graf and B. H. Huat. London: Routledge, 2009.

- Sepe, Marichela. “Urban History and Cultural Resources in Urban Regeneration: A Case of Creative Waterfront Renewal.” Planning Perspectives 28, no. 4 (2013): 595–613. doi: 10.1080/02665433.2013.774539

- Sorensen, Andre. “Taking Path Dependence Seriously: An Historical Institutionalist Research Agenda in Planning History.” Planning Perspectives 30, no. 1 (January 2015): 17–38. doi: 10.1080/02665433.2013.874299

- Strupp, Christoph. “Seaports in Transition. Global Change and the Role of Seaports Since the 1950s.” Planning Perspectives, May, 2015.

- Ward, Stephen V. “The International Diffusion of Planning: A Review and a Canadian Case Study.” International Planning Studies 4, no. 1 (1999): 53–77. doi: 10.1080/13563479908721726

- Ware. Blue Frontiers. Comparing Urban Waterfront Redevelopment. Ljubjyana: Grundvigt, 2013.