ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the place of utility cycling (cycling as a means of transport rather than as a sport or leisure activity) under urban modernism in the UK. In many western contexts the dominant feature of urban modernism was its emphasis on accommodating private vehicles to the neglect of other forms of mobility. The result was the production of a ‘car-system’ with significant change to urban and rural environments. This paper assesses resistance to what we term ‘automobile modernism’ during the high watermark of its planning and implementation (1950–1970), using the UK Cyclists’ Touring Club (now known as Cycling UK) archive. We make three contributions. First, and primarily, we highlight how cycling advocacy contested automobile modernism’s claim that cycling was ‘outmoded’. In so doing we note significant continuity in policy debates and political advocacy regarding cycling’s place in the road environment around issues such as segregation from motor vehicles. Contemporary attempts to promote cycling, as well as a wider urban sustainability agenda, are heavily influenced by this history. Second, we highlight a commonality between cycling and other resistance to automobile modernism in terms of rural and urban landscape impacts. Third, we highlight how the CTC ‘professionalized’ its advocacy to resist automobile modernism.

Introduction; urban modernism, ‘predict and provide’ and the emergence of the car-system

Transport is often considered as a derived demand, something that arises from the need, and/or sometimes the desire, for people to get from one place to another. The degree to which the levels and types of demand can be controlled through intervention in the built environment, as well as other factors, has only come to be known relatively recently.Footnote1 That is, travel demand is socially constructed and part of that construction stems from the affordances built into physical environments by planning practices themselves. For much of the second half of the twentieth century, transport planning, and by extension much city planning practice, proceeded through an approach termed ‘predict and provide’ where travel demand was simply extrapolated and attempts to provide for it made.Footnote2 Predict and provide necessitated a radical reshaping of cities to facilitate much greater movement by private carFootnote3 and became part of an overarching discourse of what GunnFootnote4 terms urban modernism.

In the twenty-first century ‘predict and provide’ has been widely discredited and partially displaced by what BanisterFootnote5 terms a paradigm of sustainable mobility. The limitations of ‘predict and provide’ and its devastating impact on urban areas became known and resisted. There have also been some shifts in citizen travel demand driven by very real trends in how travel time can be used,Footnote6 but also in recognition of the emotive and affectual nature of travel itself.Footnote7

Gunn suggests that British urban modernism begins broadly with the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act and ends with the explosion at Ronan Point in 1968 with a shadow decade of influence either side.Footnote8 The belief in urban road-building exclusively for private vehicles as the major ‘solution’ to urban mobility problems broadly mirrors this timeframe and supports Gunn’s thesis.Footnote9 UK transport thinking becomes oriented to ‘predict and provide’ in terms of cars and roadbuilding in the 1930s. By the 1960s the need to also maintain public transport for the ‘carless’ is consolidated into the 1968 Transport Act, although ‘predict and provide’ in transport planning tends to re-emerge despite the theoretical evidence against it.

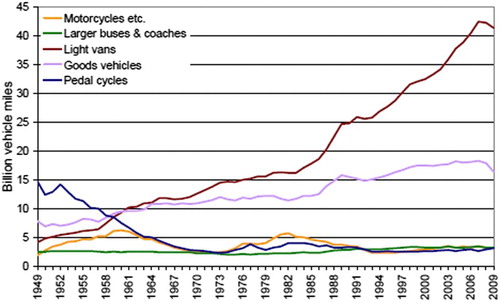

Indeed our focus here on cycling has coincidental dates. Cycle usage peaked in the UK in 1949 at 37% of miles travelled and declined sharply until the global oil crisis of 1973 (see ) when it bottomed out at 1.6% of miles travelled (3.7bn passenger km), before small increases in the mid-1970s from whence it fluctuated between for the rest of the twentieth century and beyond.Footnote10 During this time car ownership increased from two million in 1949, to four million in 1957 and six million in 1961,Footnote11 moving from being a technology for a privileged few to a much wider ownership. The UK position is mirrored in other western nations from roughly the late 1940s to the mid-1970s in relation to both car ownership and use and bicycle usage.Footnote12

Figure 1. Road traffic by vehicle type (excl. cars) Great Britain 1949–2009. Source: Department for Transport, Transport Statistics.

We suggest that transport issues provide the defining foundations of urban modernism with ideas such as pedestrianization of retail centres, urban motorway building and ring road development and high rise housing all having strong associations with wider ideas concerning urban movement. Transport planning at this time becomes almost exclusively about catering for the actual and projected increases in car use, ‘predict and provide’, which we argue represent a key set of practices underpinning a discourse within transport planning and beyond of ‘automobile modernism’. Automobile modernism extends beyond the urban. It encompasses intra and inter-urban movement, not least as counter-urbanization is a key feature of this period which is in turn facilitated by road-building and increases in private vehicle ownership, which created further demands for road-building within and between urban areas.

The place of bicycles within ‘automobile modernism’

The implementation of modernist planning ideals created environments conscripted to a ‘regime of automobility’.Footnote13 Thus, the 1950s and 1960s were a time when John Urry’sFootnote14 ‘car-system’ became embedded in society, with wide-ranging impacts on urban and rural landscapes. This period of automobile modernism neglected actual and potential movement by bicycle, which became perceived to disrupt the ‘normal’ road environment.Footnote15

Indeed, bicycles have largely been erased from research on this period also.Footnote16 But as we show later there was resistance from bicycle interest groups to automobile modernism and urban modernism more generally. As such this paper provides a fresh perspective on the modernist planning period when such environments were planned, and variably implemented. It thus provides a window on the politics of urban transport policy-making of the time, of how Urry’s ‘car-system’ became locked into the built environment. European case-studies have acknowledged a politics of resistance,Footnote17 but this is still a topic to be explored within British planning history.

Research methodology

This study uses the Cyclists Touring Club’s (CTC) archive to examine how the increasingly marginalized mobility practice of cycling was posited in relation to automobile modernism. The presence of such an archive is extremely valuable and such a resource is not available in many nations forcing a recourse to other, perhaps less useful, sources to explore the period.Footnote18 We frame our analysis within a policy discourse methodology in which a discourse is a coherent ensemble of ideas, concepts, and potentially artefacts, through which meaning is generated.Footnote19 Discourses are themselves underpinned by storylines and practices and it is these we look for in the archive.Footnote20 Storylines and discourses can comprise of tropes, imagery, computer models and a range of potential things. In section four we present a number of images and quotes that address our empirical questions namely: the CTC position on protecting cyclists’ rights and the allocation of physical space for cyclists within the road environment; the connection between that positioning and wider resistances to automobile modernism in terms of the car-system’s impact on rural and urban landscapes; and finally how cycling communities resisted urban modernism.

We acknowledge that archives are a ‘raw batch of occurrences’,Footnote21 which, only capture ‘traces’ of the discussion.Footnote22 We have sought to be robust within our analysis by iteratively interrogating the archive to develop new keywords to continually check on our own investigation of themes. For instance, any reference to specific government organizations or ministers, protests, propaganda, and roads provided a starting point for searching for relevant material. As the analysis continued, the list of keywords expanded in size, developing a wider and more reflective data set.

The Cyclists’ Touring Club was a ‘vigilant political voice seeking to defend and extend cyclists’ rights’ for much of the twentieth century.Footnote23 Oakley’s history of the CTC’s first 100 years highlights the organization’s challenge to the marginalization of the bicycle in road design but there is little detail of how they promoted cycling and how they lobbied government.Footnote24 In our case we focus principally on a single key source in the archive, the monthly and later, bi-monthly Gazette of the CTC which has been published largely without interruption from the organization’s inception in 1878. It thus provides a continuous source of information in the same format and therefore enables a systematic review of the development of storylines and discourses across the study period. The 1950–1970 timeframe was selected in response to the literature review as representational of when modernism in planning practice was coming into being and enacted, and follows the high-water mark in UK cycle usage of 1949 and the peaking of CTC membership in 1950.Footnote25

Contesting automobile modernism

Today, in many cities, the car often provides benefits that other transport modes do not, such as freedom, comfort, and speed. These benefits were also those of the bicycle preceding the dominance of motorized transport.Footnote26 The benefits of the car are however configured by the ‘car-system’ which emerged and was facilitated by the planning practices of urban modernism that became ‘materialised in a stable form’.Footnote27 In the first half of the twentieth century, bicycle and car usage grew together, as they co-evolved from invention at a similar point in history. Thus one was not displaced by the other in some sort of natural order, rather they are co-terminus in history.Footnote28 Indeed the basic road system that provided an essential component of the car-system was a result of lobbying by cycle groups.Footnote29 By contrast, the contemporary car-system was rapidly brought into being in the UK in the middle decades of the twentieth century. Herein, rather than a co-evolution of cars and bicycles, cycles were rendered ‘outmoded’: as children’s’ toys in the US and UK;Footnote30 and in Europe through a Darwinian process of competition, ‘the motor cycle and the scooter are rapidly ousting the pedal cycle. They in turn will later be replaced by the car’.Footnote31

The emergence of the car-system was not inevitable but a constituent product of a paradigm of modernity that promised growth and development through speeding up, transforming and re-shaping society.Footnote32 An ideology of ‘heroic’ planning and engineering emerged where technical expertise formulated a vision of a linear path which was almost universally agreed upon.Footnote33 All this in a climate of ‘1950s syndrome’ where cheap oil fuelled a period of mass consumption centred on a worship of new technology.Footnote34 Automobile modernism appealed to the minority of households who owned a car in the 1950s and 1960s and to those who aspired to ownership. Alternatively many now see that [auto] modernity forced citizens into an ‘iron-cage’ through the creation of ‘dead public spaces’ which only the automobile could traverse.Footnote35 Such landscapes became orientated exclusively for cars, where streets which provided multiple community needs (shopping, strolling, parades, traffic access, demonstrations) were replaced and redesigned as part of a roads hierarchy that were specific in prioritizing car-centred movement.Footnote36

The ‘car-system’, is thus held to have six components which, in combination, give cars a ‘specific character of domination’.Footnote37 One of these is the subordination of ‘competitors’ such as the bicycle through the constraints it imposes.Footnote38 Automobility is then a powerful socio-technical system that ‘impacts not only on local public spaces and opportunities for coming together, but also on … aspirations to modernity’.Footnote39 Urry’s idea of the car-system’s embeddedness is seen as over-totalizing by some who call for a more nuanced assessment of the period of its rollout.Footnote40 This paper goes some way to adding such nuance, focusing on its contested implementation.

Transport policy during modernism

Automobile modernism was underpinned by a consensus about the value of modernism.Footnote41 In the transport field new modelling practices could analyse and predict changes in traffic flows which were all part of a period of intense fervour for new technology.Footnote42 The increased distances between home, work, and leisure were to be handled by motorized transport and outside of the largest cities, almost exclusively by the automobile.Footnote43 Bicycles do not feature at all in many city plans of the time despite cycling still being significant.Footnote44 The highly influential Buchanan Report devotes a small amount of space to the bicycle in the ‘small town’ case study but not elsewhere in the report with space instead given over to discussion of the ‘future technologies’ of jetpacks, ‘air-cushion crafts’ and travellators. Indeed the exhortation to ‘imagine a fairly small, independent, self-powered and highly manoeuvrable means of getting about at ground level’Footnote45 is all too suggestive to modern ears of bicycles and indeed such advantages were recognized in the Gazette some years previously (see ). But the rapid demise of cycling in the 1950s was presumably, possibly unconsciously, extrapolated in the minds of Buchanan’s team and rendered ‘outmoded’, ultimately contributing to a vicious circle which assumed the non-existence of cyclists.Footnote46 Given the significance of cycling in cities at the time, outmoded was rather a prediction than a fact and contributed to analysis that suggested transport planning was conducted by middle-class, white, car-owning men to benefit middle-class, white, car-owning men.Footnote47

Thus automobile modernism left no space for the bicycle and cycling became viewed as deviant, irrational and problematic, with the car installed as the rational ‘normal subject’.Footnote48 It was therefore materialized and built into the city through urban infrastructure and planning policies which in turn shaped the future use of particular mobilities.Footnote49 The urban environment was imagined with the motorized, mechanical forms of the car on the road and the non-motorized, non-mechanical form of pedestrians on the pavement, but the non-motorized, mechanical form of the bicycle effectively failed to comply with the two zones of accepted mobility. The next section explores these issues using the UK case.

Cycling’s resistance to automobile modernism: the case of the UK CTC

Despite the power of the ‘cycling as outmoded’ storyline, cycling as a practice did not disappear under auto-modernist planning. It is therefore pertinent to explore how the idea and practice of urban cycling was kept alive and promoted as the car-system became enmeshed in everyday environments and in people’s lives.

There is a paucity of writing about cycling from an urban planning perspective during the 1950–1970 period itself, and about this time subsequently,Footnote50 but European research shows how nearly all cycle advocacy groups lost their relevance as political actors and many shifted their focus away from challenging the car-system.Footnote51 Longhurst’s account of the US even highlights the dissolution of the main lobby group, the League of American Wheelmen, in 1955.Footnote52 This section brings a detailed empirical account of the British experience to these accounts using archival research to highlight both a representation of cyclists’ agendas in the form of editorial comment and writing from CTC staff, but also from cyclists themselves in the form of letters and submitted articles to the CTC’s monthly (1950–1963) and bi-monthly (1964–1970) ‘Gazette’.

Founded in 1878 as the ‘Bicycle Touring Club’, its main priorities were to identify suitable places for cyclists to stay and to publish these in a member’s guide for the benefit of bicycle-touring as a recreational activity.Footnote53 The CTC’s contemporary mission is for ‘all ages, backgrounds and abilities to be able to cycle safely, easily and enjoyably’.Footnote54 In the two mission statements one can imply a shift from a focus on the rural environment as a place in which to cycle for leisure to one encompassing utility cycling. Whether in rural or urban settings, the threat of mass-motorization was recognized from the 1920s onwards and meant the CTC increasingly became a political lobbying organization to defend cyclists’ rights.Footnote55 The remainder of this section is structured around our three empirical contributions.

Contesting the ‘car-system’ and the issue of segregation

The key axis of debate in the CTC archive, and one which has dominated debates among cycling advocates, is whether to segregate cyclists from other vehicles. Mass motorization led to conflicts between cars and cycles which resulted in calls to remove cycles from both urban and rural roads. Historically the CTC’s policy was to resist such moves and in an article by CTC staff they reasserted that they ‘always opposed cycle paths’;Footnote56 however in 1955 the Editorial Opinions section, which usually introduced the Gazette on the front pages, contained a statement to support them on the following condition.

The serious cyclist will assert that if it connoted, as so many defenders of the cycle-path principle declare, a special facility for one of the most vulnerable vehicles on the highway, it would be welcomed. If the cycle paths were in fact special cycle lanes of good construction and design, taking the cyclist from the unpleasantness and possible danger of a common carriageway and enabling him [sic] to ride continuously in happier circumstance, they would be universally popular.Footnote57

Drivers of motor vehicles are finding that the inevitable ‘throwing back’ of cycles into the main traffic stream at such points of traffic-light-installations is a serious impediment to their own free use of the highway. It is little consolation to know that, between intersections, cycle traffic is relegated to separate tracks.Footnote58

A cycle lane on the other hand suggests a wider, dedicated continuous infrastructure without having to re-integrate with other traffic. In the 1950s Stevenage New Town’s ‘cycleways’ were designed as a reaction to cycle paths of previous decades which were considered too narrow and lacked the network effect.Footnote60 Stevenage’s engineer, Eric Claxton, was given space in the Gazette to advocate their use and elsewhere an article ‘Cycleways Investigation’ noted how cycleways bridged the perceived problems of the cycle path by ‘generally following the line of the usual carriageway but incorporating their own underpasses at all road junctions’.Footnote61

shows how these cycleways were segregated from pedestrians with separate spaces provided for both practices. As a result, they are somewhat different to other cycling infrastructure such as shared-use paths where both pedestrians and cyclists share the same piece of tarmac, often segregated by a painted white strip demarcating which side they should be on. Instead, cycleways provided fully segregated space for cycling as shown in . Legitimacy was reinforced through the use of ‘cyclists only’ signs. The CTC confirmed their support for cycleways, encouraging their construction in all new townsFootnote62 but they still advocated the right to use all roads apart from motorways. This long-held position was, for example, outlined in an Editorial Opinion piece in objection to the City and County of Oxford’s plans to compel cyclists to use an adjacent cycle path on the Oxford Eastern Bypass.Footnote63

Figure 3. Stevenage cycleway underpass at road junction. Source: http://www.roadswerenotbuiltforcars.com/stevenage/, last accessed 4 April 2017.

Therefore the CTC constructed two opposing ideas of the bicycle when using the terms cycle paths and cycleways/cycle lanes which, contribute to two different identities of the cyclist in the urban environment. In supporting the latter, the CTC is encouraging others to recognize that cycleways create specific space for the cyclist, confirming a legitimate presence. In so doing the CTC embodies the critique of ‘vehicular cycling’ as over-representing a very particular view of cycling, the ‘serious cyclist’, one who is experienced and confident mixing with traffic.Footnote64 Only in the 2000s did cycle groups effectively challenge this dominant view, making the case for segregation for less confident adults, children, etc.

Thus although the CTC were open to segregation in the form of cycleways in urban areas, they still advocated the right to use the road.Footnote65 One way they sought to make space for cycling was to support the construction of motorways for fast traffic which would leave regular roads freer of cars. The passionate and long-standing nature of such advocacy was most strongly revealed in an article, ‘MOTORWAYS AT LAST?’ [capitalization in original]:

The CTC has for very many years, strongly advocated the segregation of fast traffic on to specially built motorways.Footnote66

Connections to wider resistances to automobile modernism

Our second contribution highlights how, as the enactment of the ‘car-system’ intensified during the early 1960s, the CTC moved to criticize the construction of both rural and urban motorways and in doing made connections to other discourses of the time. and provide graphic representations of how motorways and trunk roads, which the CTC previously advocated in order to maintain the enjoyment of cycling on ordinary roads, now posed a threat.

Figure 5. ‘Trail of the modern improvement devil’. Source: Cyclists’ Touring Club, The CTC Gazette, 1961, 23.

Figure 6. Perceived future of the automobile-age. Source: Cyclists’ Touring Club, The CTC Gazette, 1963, 81.

, a pictorial commentary reproduced from 1936 by Frank Patterson, a cycling artist, famous in his day, steps out of his usual illustrations of cycle touring to convey the thoughts of many as to how the aesthetics of rural England, enjoyed by the cycle tourer who read the Gazette, were under continued threat from the car.Footnote68 It suggests the car is destructive as it requires the demolition of historic and delightful things such as old trees, monuments, humpback bridges and thatched cottages to create wider roads with clearer sightlines and space for elements of the car-system such as petrol pumps. The implementation of design standards that result in straightening roads and building curbs are thought to take away the delight of cycle touring experienced by the Gazette reader in previous decades.

Similarly, provides a perceived glimpse into the future of the car-system depicted with tentacles reaching towards the small pockets of beauty which are left. A letter from a CTC member, which accompanied , sums up the values inherent in both and :

Though every one of them, out for his [sic] Sunday cruise or on his annual mile-eating tour, is a professed country-lover, the fact remains that the collective effect of the driving about Britain of six million motors, by as many country-lovers, is an ever-increasing number of car parks, petrol pumps, and enamelled road signs in ever remoter places.Footnote69

There is no singular CTC discourse at this time however. With growing use of all roads and the ‘new’ motorway system,Footnote71 some rural roads were still promoted in CTC editorials as being more sympathetic to the cyclist:

The tendency for traffic to concentrate itself on motorway or near-motorway routes is progressively having the effect of leaving the secondary roads quiet for cyclists – yes, and many motorists too – who do not wish to rush from A to B at ‘full belt’.Footnote72

In contrast cycling is advocated in Editorial comment as a moral leisure pursuit:

The cyclist has freedom to wander; his [sic] timetable and schedule are his own; he has no running costs; he is virtually independent of strikes, breakdowns, and parking restrictions. He can press on or linger according to his inclination, and stop at will for the view that takes his eye.Footnote77

Resisting automobile modernism; the cycling lobby

The paper’s third contribution is to explore how the CTC ‘professionalized’ in resisting automobile modernism. In doing so we show how cycling groups sought to achieve their ends through the relationships they created and maintained within the political sphere.

Throughout the Gazette there are constant updates of local incidents and policy disputes which may affect the cyclist. These perform an important function of connecting and encouraging local members to support the CTC’s causes. The Gazette thus becomes a mobilization tool, keeping everyone ‘in the know’ but also acting as an advert for help from other members experiencing the same problem. It thus seeks to facilitate political change at local and national levels through mobilizing its members, in, for example, this letter objecting to a motorway proposal from CTC member B. J. Jeffreys:

Individual members can play their part in this struggle by writing to their M.P. asking for his support in rejecting any proposal which would intrude into this unspoilt region. The time to do it is NOW.Footnote78

Why should such restricted vision [from cars] be tolerated? Isn’t it reasonable to expect that all motor vehicles should have mirrors on the left hand side and an adequate view towards the rear?Footnote79

Such resistance was formed as a resistance to a safety discourse which put the onus on the victim, in this case the cyclist. Motoring organizations did seek to educate drivers in good conduct but such literature often revealed particular attitudes. Thus the CTC reproduced the Automobile Association’s ‘Safety through Courtesy’ booklet (see ) to show that while the message of ‘DO look behind before opening a door’ was important and placed responsibility on the driver, the image also implied that fault lay with the angry, speeding cyclist and not the polite and courteous driver. By drawing awareness to opposing propaganda material, the CTC built an argument of stigmatization which they used to convey to the membership. This is particularly interesting in the context of renewed academic attention to explaining the particularities of the UK’s issues with cycling compared to its northern European neighbours and the stigmatization of the cyclist in professional and popular discourse.Footnote80

Figure 7. Automobile Association’s Safety Through Courtesy booklet. Source: Cyclists’ Touring Club, The CTC Gazette, 1952, 645.

‘Educating’ the press

The opinion that the bicycle was fundamentally unsafe on the roads became institutionalized in press comment and contributed to a storyline of bicycles as ‘outmoded’. The CTC approached this representation diplomatically and attempted to ‘educate’ the press, providing statistical data to debunk claims and expose the negative externalities of increasing car use.

The CTC pointed out many times that the press and others constructed storylines in which the bicycle was portrayed as unsuitable for the road and a safety hazard. In one paradigmatic article, ‘This is what we are up against and here are the answers’ [!] the CTC juxtaposes two differing points of view in relation to road deaths in order to build their argument.Footnote81 A journalist stated that:

Even if cyclists, motorists and everybody else concerned were one hundred per cent careful, cyclists would still be killed by motorists (though admittedly in smaller numbers), simply because of the fundamental unsuitability of the bicycle as a means of safe transport under traffic conditions as they are today.Footnote82

It has often been necessary, both at HQ and local level, to explain to a surprised press reporter that we are not ‘just a club’ but a national organisation that can provide service and protection for all cyclists.Footnote84

The emergence of a more professional lobbying

The establishment of the CTC ‘Defence Fund’, financed by members donations, helped fund research and the distribution of leaflets to its members and others. Leaflets including ‘You can’t blame the cyclist’ acted to contest media discourse, referring to other viable reasons for poor safety issues as ‘bad surfaces at road edges where cyclists are expected to ride’.Footnote86 The Defence Fund also ‘professionalized’ rank and file lobbying by members in providing boiler plate text to be used by them, a mechanism common to lobby groups today. The CTC, through the Defence Fund, therefore instigated a practice to educate members while prompting them to use more ‘objective’ language and evidence.

The CTC’s ‘objective’ approach is further evidenced in regular use of phrases of ‘calling’ or ‘drawing’ to attention statistical evidence through the regular ‘Newsreel’ column.Footnote87 However it could also be militant, with staff writers using words such as, ‘ammunition’ ‘fighting’ for interests, ‘combating’, ‘attacking’ dangerous road surfaces, and being on ‘constant watch’.Footnote88 This language was defensive in referring to the CTC ‘fighting against the grain’ and consistently being ‘under fire’,Footnote89 particularly with regard to the Minister of Transport who is often negatively portrayed.Footnote90 Attempts to delegitimize official reports were regularly contrasted with the CTC’s own position centred on ‘justice’ and being the ‘cyclists’ champion’ as argued by the then editor in the article ‘What is there to fight about? And with?’Footnote91 They did however acknowledge that the CTC ‘must also be, when necessary, its sternest critic’ in relation to condemning ‘inconsiderate behaviour on the roads by members of the class it exists to protect’, a common feature of continuing debate among cycle campaigners.Footnote92

During the late 1950s, however, the CTC acknowledged in their Annual Report a turn in fortunes with support from the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) for their calls for car drivers to take more responsibility.Footnote93 illustrates this with capital letters and exclamation marks creating a forceful tone. Another poster carried the slogan ‘Mind that cyclist: give him room!’ signifying the right of the cyclist to share the road.Footnote94 It is worth noting the everyday white collar attire of the cyclist in who appears very much the victim, in contrast to the blue collar attire in where his speeding appears to contribute to his downfall.

There is ambiguity here. Ernest Marples, seen very much as a pro-roads Minister for Transport in the early 1960s, not least as he owned a large road construction company, Marples Ridgeway, was also a CTC member. Certainly by the end of the 1960s the simplicities proffered by automobile modernism had been replaced by something more complex. An article in the Gazette noted the formulation of a parliamentary group titled ‘Friends of Cyclists’, creating a presence for cyclists within the political sphere. The 1968 Transport Act introduced a range of measures that sought to arrest urban public transport decline and make roads safer such as drink driving legislation, seat belts and speed limits. More widely, reactions against the destruction of the built environment necessitated by providing for automobile modernism started a process of challenge and reconsideration of future intra-urban transport planning,Footnote95 which, alongside the oil crisis of 1973 led to a renewed, if partial, renewal of interest in cycling in the 1970s in the UK and beyond. Thus Automobile Modernism largely ended as a coherent discourse in the early 1970s in parallel with Gunn’s urban modernism paradigm. But as we have seen much of the argumentation and practices concerning the enactment of transport planning generally and of cycling’s place in the road environment continued and persist remarkably unchanged.

Conclusions

This paper makes three contributions and these are used to structure the conclusion. First, and primarily, we highlight how cycling advocacy contested automobile modernism’s claim that cycling was ‘outmoded’. In doing so advocates had to address the many components of the ‘car-system’ that threatened cycling. The story is somewhat one of continuity, with the roots of urban motorway building and of segregating cycling from faster roads rooted in the 1930s and made manifest in plans of the 1950s and 1960s. But the key finding here is of an absence in relation to cycling: the CTC has to lobby to have cycling considered at all by policy-makers, despite its significance as a practice at least until the early 1960s. It was thus rendered outmoded by planners, the media and others well before it became marginalized. The outmoded storyline is one interpreted mostly from a silence, from a complete disregard as bicycles became rendered as children’s toys, not a modern means of adult transportation. While this decline is only partly related to plans and policies it gives further credence to the dominance of the ‘predict and provide’ paradigm: cycling was predicted out as car use was predicted in, only in relation to cycling this wasn’t made explicit. The self-fulfilling nature of this has only latterly become known. The huge increase in car ownership created a climate in which the degree to which the car was accommodated in cities became institutionalized as discourse, that is embedded into the practices and routines of planners to the exclusion of everything else until activists highlighted the impacts on streets and communities and of the need to preserve public transit as an alternative.

Within this broad frame the main point of resistance concerned segregation of cycling from main roads. The CTC continued its long-held opposition to segregation, mostly due to very real fears about the quality of alternative provision and possibly the threat of losing legal access to cycle on many roads, although more research is needed to support this claim. The segregation debate has continued to divide cycle campaigners in the UK, and its origins and development helps understand the strength of feelings associated with it. Indeed the approach to road space design in which cycleways and slow ways create spaces for cycling while allowing for automobile modernism to be rolled out elsewhere is not so far from the contemporary position whereby segregation is advocated on fast, busy roads and mixing with slower speeds on quieter roads. The CTC initially backed motorway and trunk road construction, with occasional opposition to specific schemes, to free up other roads for safer, more pleasant cycling. But traffic on major routes starts and ends on minor roads eventually and this wider auto-mobilization further marginalized cycling as the period progressed. As a result, much of the main thrust of automobile modernism was not contested. Whether this represented a realistic position given the public discourse of the time, or was indicative of the limited resources of the CTC, which became devoted to a defensive contestation of the ‘outmoded’ storyline, especially in the 1950s, requires more research. Faced with a huge drop-off in regular cycling as car ownership moved from elites to the middle classes, the CTC must itself have questioned the future role of utility cycling.Footnote96 Further exploration of the archives of other organizations such as the Pedestrians Association, or other cycling groups, or indeed interviews with protagonists of the time may reveal the answers to these questions. But more widely, the stigmatization of the bicycle as an outmoded practice became institutionalized, accepted as ‘normal’, despite the CTC’s efforts.

In this, the findings do contrast somewhat with other nations. In Sweden, cyclists were legislated off the roads to pathways in urban areas. But in the Netherlands transport planners in the 1960s became much more interested in other ideas of the time such as Buchanan’s idea of environmental areas and by the late 1970s had created much better conditions for cyclists and pedestrians.

An explanation for the CTC position lies in our second contribution which is to highlight the connection of CTC resistance to wider discourses surrounding urban modernism in England. The CTC argument was ‘modern’ in that it did not deny the beauty of the arterial road, but rather the urbanization that accompanied it, encroaching on rural landscapes. In this it had much in common with other resistances to urban sprawl.Footnote97 The CTC was more affronted by elements of the car-system such as the petrol station and the proliferation of signage as the motorway. In this the CTC can be seen as part of a ‘planner preservationist’ discourse, conceived as being ‘modern’ in their desire to create order and to plan, around a particular moral code.Footnote98

Our third contribution is to note how automobile modernism was resisted with the most notable feature being the ‘professionalization’ of CTC lobbying. The CTC mobilized quantitative evidence where possible and adopted an ‘objective voice’ in order to juxtapose its argument against others, to contest the automobile modernism discourse created by both the press and government. An educative stance with the press in the 1960s contrasts with a far more aggressive approach when interacting with government officials previously.Footnote99 The CTC’s rhetorical softening suggests that it found itself with an increasingly difficult argument to make given the huge falls in cycling: that the organization was trying to hold back the tide. It was poorly resourced to contest the automobile modernism discourse and its associated promoting coalition of a motoring lobby and professionals in engineering, architecture and town planning. Throughout the period the CTC, especially in relation to the press, fought a rear-guard action focused on refuting claims and accusations, limiting their opportunity to focus on the more positive virtues of cycling. The involvement of CTC members was also significant. The Gazette was used to rouse support and the Defence Fund signified the CTC’s awareness of the need to have a consistent and objective voice if arguments for cycling were to be taken seriously.

In conclusion, we have shown how much contemporary debate in transport planning and theory has historical resonance and how much history matters in shaping the limits of contemporary planning intervention. The discourse of automobile modernism became, in Hajer’s terms, structured then rapidly institutionalized as part of a wider urban modernism movement in UK planning in the 1950s, underpinned by the practices of ‘predict and provide’ in transport planning. The institutionalization of the discourse and its subsequent influence on built form makes unpicking it in the name of promoting cycling, sustainable mobility or a wider sustainable cities agenda incredibly difficult. Thus our findings help us understand how the urban legacy of automobile modernism significantly shapes the ability to affect urban change.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kay Lakin and Sue Cherry for their kind assistance at the Cyclists’ Touring Club archive. We gratefully acknowledge the CTC, now Cycling UK, for their permission to reproduce archival material. We would like to thank Steve Graham for help in steering the original research project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For example, Goodwin et al., Transport, the New Realism.

2 Owens, “From ‘Predict and Provide’.”

3 Starkie, The Motorway Edge.

4 Gunn, “British Urban Modernism.”

5 Banister, Unsustainable Transport.

6 Jain and Lyons, “Travel Time.”

7 For example, Shaw and Hesse, “Transport and ‘New’ Mobilities.”

8 Gunn, “British Urban Modernism.”

9 Vigar, The Politics of Mobility; Docherty and Shaw, Traffic Jam.

10 Golbuff and Aldred, Cycling Policy in the UK.

11 Tetlow and Goss, Homes, Towns and Traffic, 63.

12 Oldenziel and de la Bruhèze, “Contested Spaces”; Stoffers, “Cycling, Sustainability, Societal Change”; Longhurst, Bike Battles.

13 Green, Steinbach, and Datta, “The Travelling Citizen.”

14 Urry, Sociologies Beyond Societies.

15 Oldenziel and de la Bruhèze, “Contested Spaces”; Aldred and Jungnickel, “Constructing Mobile Places.”

16 For example, Longhurst, Bike Battles.

17 For example, Emanuel, “Constructing the Cyclist”; Ebert, “When Cycling Gets Political”; Ebert, “Cycling Towards the Nation”; Koglin and Rye, “The Marginalisation of Bicycling.”

18 Longhurst, Bike Battles, uses television shows due to a complete absence of alternatives in the 1950s.

19 Hajer, The Politics of Environmental Discourse.

20 Ibid.

21 Goffman, Frame Analysis, 10.

22 Hill, Archival Strategies and Techniques.

23 Horton, “Social Movements and the Bicycle,” 8.

24 Oakley, Winged Wheel.

25 Longhurst, Bike Battles, 157.

26 McGurn, On Your Bicycle; Horton, Cox, and Rosen, “Introduction: Cycling and Society.”

27 Slater, “Markets and Materiality,” 101.

28 Stoffers, “Cycling, Sustainability, Societal Change.”

29 Reid, Roads Were Not Built for Cars.

30 Longhurst, Bike Battles; Golbuff and Aldred, Cycling Policy in the UK.

31 Leibbrand, Transportation and Town Planning, 14.

32 Rydin, “Re-examining the Role of Knowledge”; Hall, Cities of Tomorrow.

33 Hall, Urban and Regional Planning; Natrasony and Alexander, “The Rise of Modernism.”

34 Pfister, “The 1950s Syndrome.”

35 Urry, “The ‘System’ of Automobility”; Freund and Martin, Ecology of the Automobile.

36 Relph, The Modern Urban Landscape, 158.

37 Urry, “The ‘System’ of Automobility”; Sheller and Urry, “Mobile Cities, Urban Mobilities.”

38 Sheller and Urry, “City and the Car,” 739.

39 Sheller and Urry, “Mobile Cities, Urban Mobilities,” 209.

40 Gunn, “People and the Car.”

41 Gold, The Practice of Modernism.

42 Hall, Urban and Regional Planning.

43 Oldenziel and de la Bruhèze, “Contested Spaces”; Emanuel, “Constructing the Cyclist.”

44 20% of all trips in Manchester in the mid-1950s were made by bicycle for example. Golbuff and Aldred, Cycling Policy in the UK.

45 Buchanan, Traffic in Towns, 25.

46 Bohm et al, “Introduction: Impossibilities of Automobility.”

47 Greed, Women and Planning; Schrag, The Great Society Subway.

48 Samuelsson, “Automobility, Car-Normativity and Sustainable Movement(s)”; Emanuel, “Constructing the Cyclist”; Bohm et al., “Introduction: Impossibilities of Automobility.”

49 Emanuel, “Constructing the Cyclist.”

50 Longhurst, Bike Battles.

51 Oldenziel and de la Bruhèze, “Contested Spaces.”

52 Longhurst, Bike Battles, Chapter 5.

53 As of September 1, 2016, Cycling UK listed on its website http://www.cyclinguk.org/history.

54 As of September 1, 2016, Cycling UK listed on its website http://www.cyclinguk.org/about.

55 Cox, “Cyclists Views on Conflicts”; Horton, “Social Movements and the Bicycle.”

56 CTC, The CTC Gazette, 1950, 31.

57 CTC, The CTC Gazette, 1955, 249.

58 CTC, The CTC Gazette, 1956, 155.

59 Forester, Effective Cycling.

60 Reid, Roads Were Not Built for Cars.

61 CTC, The CTC Gazette, 1961, 195.

62 CTC, The CTC Gazette, 1963, 214.

63 CTC, Cycletouring. The CTC Gazette, 1966, 165–6.

64 Pooley et al, Promoting Walking and Cycling.

65 Cox, “Cyclists Views on Conflicts.”

66 CTC, The CTC Gazette, 1955, 83.

67 CTC, Cycletouring. The CTC Gazette, 1964, 131–2.

68 CTC, The CTC Gazette, 1961, 23.

69 CTC, The CTC Gazette, 1963, 80.

70 Nairn, “Outrage: Disfigurement of Town and Countryside.”

71 The first motorway standard road in the UK was the 8 mile ‘Preston Bypass’ in Lancashire, now part of the M6, which opened in 1958; the London –Birmingham stretch of the M1 was Britain's first full-length motorway (61 miles) and opened in 1959.

72 CTC, Cycletouring. The CTC Gazette, 1965, 33.

73 Ibid.

74 Matless, Landscape of Englishness, 63.

75 For example, Matless, Landscape of Englishness.

76 Hoskins, Making of English Landscape; Tewdwr-Jones, “Planning Films of John Betjeman”; Williams, The Country and the City.

77 CTC, The CTC Gazette, 1960, 35.

78 CTC, The CTC Gazette, 1962, 142.

79 CTC, The CTC Gazette, 1954, 312.

80 Aldred, “Incompetent or Too Competent?”

81 CTC, The CTC Gazette, 1956, 352–3.

82 Ibid., 352.

83 CTC, The CTC Gazette, 1956, 294.

84 CTC, Cycletouring, 1968, 153.

85 Emanuel, “Constructing the Cyclist.”

86 CTC, The CTC Gazette, 1956, 308–9.

87 For example, CTC, The CTC Gazette, 1959, 92 and also 140.

88 CTC, The CTC Gazette, 1961, 80; 1960, 79; 1956, 363.

89 CTC, The CTC Gazette, 1956, 383.

90 For example, CTC, The CTC Gazette, 1955, 19; 1950, 147.

91 CTC, The CTC Gazette, 1955, 106–7.

92 Ibid.

93 CTC, The CTC Gazette, 1960, 49.

94 CTC, The CTC Gazette, 1959, 207.

95 For example, Plowden, Towns Against Traffic.

96 Car ownership at this time was still only for a minority of households, much less in urban areas, and regular access to cars, particularly for women, was considerably lower still. The political left’s position in the form of the Labour Party in the early 1960s with regard to such inequity was to hasten universal car ownership.

97 Matless, Landscape of Englishness.

98 Ibid., see also Gunn, “The Buchanan Report” on how planners from Geddes through Abercrombie to Buchanan fused environmentalism and modernism in a particularly English way.

99 Reid, Roads Were Not Built for Cars.

Bibliography

- Aldred, Rachel. “Incompetent or Too Competent? Negotiating Everyday Cycling Identities in a Motor Dominated Society.” Mobilities 8, no. 2 (2013): 252–271. doi: 10.1080/17450101.2012.696342

- Aldred, Rachel, and Katrina Jungnickel. “Constructing Mobile Places Between ‘Leisure’ and ‘Transport’: A Case Study of Two Group Cycle Rides.” Sociology 46, no. 3 (2012): 523–539. doi: 10.1177/0038038511428752

- Banister, David. Unsustainable Transport. London: Routledge, 2008.

- Bohm, Steffen, Campbell Jones, Chris Land, and Matthew Paterson. “Introduction: Impossibilities of Automobility.” In Against Automobility, edited by Steffen Bohm, Campbell Jones, Chris Land, and Matthew Paterson, 3–16. Oxford: Blackwell, 2006.

- Buchanan, Colin. Traffic in Towns. A Study of the Long Term Problems of Traffic in Urban Areas. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1963.

- Cox, Peter. “A Denial of Our Boasted Civilisation: Cyclists’ Views on Conflicts over Road Use in Britain, 1926–1935.” Transfers 2, no. 3 (2012): 4–30. doi:10.3167/trans.2012.020302.

- Cycling UK. “About.” Accessed September 1, 2016. http://www.cyclinguk.org/about.

- Cycling UK. “History.” Accessed September 1, 2016. http://www.cyclinguk.org/history.

- Cyclists’ Touring Club. The CTC Gazette. Journal of the Cyclists’ Touring Club. London: Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1950.

- Cyclists’ Touring Club. The CTC Gazette. Journal of the Cyclists’ Touring Club. London: Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1952.

- Cyclists’ Touring Club. The CTC Gazette. Journal of the Cyclists’ Touring Club. London: Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1954.

- Cyclists’ Touring Club. The CTC Gazette. Journal of the Cyclists’ Touring Club. London: Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1955.

- Cyclists’ Touring Club. The CTC Gazette. Journal of the Cyclists’ Touring Club. London: Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1956.

- Cyclists’ Touring Club. The CTC Gazette. Journal of the Cyclists' Touring Club. London: Cyclists' Touring Club, 1957.

- Cyclists’ Touring Club. The CTC Gazette. Journal of the Cyclists’ Touring Club. London: Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1959.

- Cyclists’ Touring Club. The CTC Gazette. Journal of the Cyclists’ Touring Club. London: Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1960.

- Cyclists’ Touring Club. The CTC Gazette. London: Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1961.

- Cyclists’ Touring Club. The CTC Gazette. London: Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1962.

- Cyclists’ Touring Club. The CTC Gazette. London: Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1963.

- Cyclists’ Touring Club. Cycletouring. The CTC Gazette. Godalming: Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1964.

- Cyclists’ Touring Club. Cycletouring. The CTC Gazette. London: Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1965.

- Cyclists’ Touring Club. Cycletouring. The CTC Gazette. London: Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1966.

- Cyclists’ Touring Club. Cycletouring. Incorporating the CTC Gazette. Godalming: Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1968.

- Department for Transport, DfT. Transport Statistics. London: HMSO, 2010.

- Docherty, Iain, and Jon Shaw, ed. Traffic Jam: 10 Years of ‘Sustainable’ Transport in the UK. Bristol: Policy Press, 2008.

- Ebert, Ann-Katrin. “Cycling Towards the Nation: The Use of the Bicycle in Germany and the Netherlands, 1880–1940.” European Review of History: Revue Europeenne D'histoire 11, no. 3 (2004): 347–364. doi:10.1080/1350748042000313751.

- Ebert, Ann-Katrin. “When Cycling Gets Political: Building Cycling Paths in Germany and the Netherlands, 1910–40.” The Journal of Transport History 33, no. 1 (2012): 115–137. doi:10.7227/TJTH.33.1.8.

- Emanuel, Martin. “Constructing the Cyclist: Ideology and Representations in Urban Traffic Planning in Stockholm, 1930–70.” The Journal of Transport History 33, no. 1 (2012): 67–91. doi: 10.7227/TJTH.33.1.6

- Forester, John. Effective Cycling. 6th ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993.

- Freund, Peter, and George Martin. The Ecology of the Automobile. New York: Black Rose Books, 1993.

- Goffman, Erving. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1974.

- Golbuff, Laura and Rachel Aldred. “Cycling Policy in the UK. A Historical and Thematic Overview.” University of East London Sustainable Mobilities Research Group. Accessed September 1, 2016. http://rachelaldred.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/cycling-review1.pdf.

- Gold, John R. The Practice of Modernism: Modern Architects and Urban Transformation, 1954–1972. Abingdon: Routledge, 2007.

- Goodwin, Phil, Sharon Hallett, Francesca Kenny, and Gordon Stokes. Transport, the New Realism. Oxford: Transport Studies Unit, 1991.

- Greed, Clara. Women and Planning. London: Routledge, 1994.

- Green, Judith, Rebecca Steinbach, and Jessica Datta. “The Travelling Citizen: Emergent Discourses of Moral Mobility in a Study of Cycling in London.” Sociology 46, no. 2 (2012): 272–289. doi:10.1177/0038038511419193.

- Gunn, Simon. “The Buchanan Report, Environment and the Problem of Traffic in 1960s Britain.” Twentieth Century British History 22, no. 4 (2011): 521–542. doi:10.1093/tcbh/hwq063.

- Gunn, Simon. “People and the Car: The Expansion of Automobility in Urban Britain, c.1955-70.” Social History 38, no. 2 (2013): 220–237. doi: 10.1080/03071022.2013.790139

- Gunn, Simon. “The Rise and Fall of British Urban Modernism: Planning Bradford, Circa 1945–1970.” The Journal of British Studies 49, no. 4 (2010): 849–869. doi:10.1086/654912.

- Hajer, Maarten. The Politics of Environmental Discourse. Oxford: OUP, 1995.

- Hall, Peter. Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design in the Twentieth Century. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996.

- Hall, Peter. Urban and Regional Planning. 3rd ed. London: Routledge, 1992.

- Hill, Michael. Archival Strategies and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1993.

- Horton, Dave. “Social Movements and the Bicycle.” Accessed September 01, 2016. http://thinkingaboutcycling.files.wordpress.com/2009/11/social-movements-and-the-bicycle.pdf.

- Horton, Dave, Peter Cox, and Paul Rosen. “Introduction: Cycling and Society.” In Cycling and Society, edited by Dave Horton, Paul Rosen, and Peter Cox, 1–23. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007.

- Hoskins, William George. The Making of the English Landscape. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1955.

- Jain, Juliet, and Glenn Lyons. “The Gift of Travel Time.” Journal of Transport Geography 16, no. 2 (2008): 81–89. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2007.05.001.

- Koglin, Till, and Tom Rye. “The Marginalisation of Bicycling in Modernist Urban Transport Planning.” Journal of Transport and Health 1, (2014): 214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jth.2014.09.006

- Leibbrand, Kurt. Transportation and Town Planning. London: Leonard Hill, 1970.

- Longhurst, James. Bike Battles. A History of Sharing the American Road. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2015.

- Matless, David. Landscape and Englishness. London: Reaktion, 1998.

- McGurn, Jim. On Your Bicycle: The Illustrated Story of Cycling. 2nd ed. York: Open Road, 1999.

- Nairn, Ian. “Outrage: On the Disfigurement of Town and Countryside.” Architectural Review Special Issue 117, no. 702 (1955).

- Natrasony, Shawn M, and Don Alexander. “The Rise of Modernism and the Decline of Place: The Case of Surrey City Centre, Canada.” Planning Perspectives 20, no. 4 (2005): 413–433. doi: 10.1080/02665430500239489

- Oakley, William. Winged Wheel. The History of the First Hundred Years of the Cyclists’ Touring Club. Godalming, Surrey: Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1977.

- Oldenziel, Ruth, and Adri Albert de la Bruhèze. “Contested Spaces: Bicycle Lanes in Urban Europe, 1900–1995.” Transfers: Interdisciplinary Journal of Mobility Studies 1, no. 2 (2011): 29–49. doi:10.3167/trans.2011.010203.

- Owens, Susan. “From ‘Predict and Provide’ to ‘Predict and Prevent'? Pricing and Planning in Transport Policy.” Transport Policy 2, no. 1 (1995): 43–50. doi:10.1016/0967-070X(95)93245-T.

- Pfister, Christian. “The ‘1950s Syndrome’ and the Transition From a Slow-Going to a Rapid Loss of Global Sustainability.” In Turning Points in Environmental History, edited by Franck Uekötter, 90–117. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010.

- Plowden, Stephen. Towns against Traffic. Oxford: Pergamon, 1972.

- Pooley, Colin G, Tim Jones, Miles Tight, Dave Horton, Griet Scheldeman, Caroline Mullen, Ann Jopson, and Emanuele Strano. Promoting Walking and Cycling New Perspectives on Sustainable Travel. Bristol: Policy Press, 2013.

- Reid, Carlton. Roads Were Not Built for Cars: How Cyclists Were the First for Good Roads and Became the Pioneers of Motoring. Washington: Island Press, 2014.

- Relph, Edward C. The Modern Urban Landscape. London: Croom Helm, 1987.

- Rydin, Yvonne. “Re-examining the Role of Knowledge Within Planning Theory.” Planning Theory 6, no. 1 (2007): 52–68. doi: 10.1177/1473095207075161

- Samuelsson, Anna. “Automobility, car-normativity and sustainable movement(s).” Paper presented at On the Move. The Advanced Cultural Studies Institute of Sweden, Norrköping, June 11–13, 2013.

- Schrag, Zachary. The Great Society Subway: A History of the Washington Metro. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

- Shaw, Jon and Markus Hesse. “Transport, Geography and the ‘New’ Mobilities.” Transaction 35, no. 3 (2010): 305–312. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2010.00382.x.

- Sheller, Mimi, and John Urry. “The City and the Car.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 24, no. 4 (2000): 737–757. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.00276

- Sheller, Mimi, and John Urry. “Introduction: Mobile Cities, Urban Mobilities.” In Mobile Technologies of the City, edited by Mimi Sheller, and John Urry, 1–17. London: Routledge, 2006.

- Slater, Don. “Markets, Materiality and the ‘New Economy’.” In Market Relations and the Competitive Process New Dynamics of Innovation & Competition, edited by Stan Metcalfe, and Alan Warde, 95–113. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002.

- Starkie, David. The Motorway Age: Road and Traffic Policies in Post-War Britain. Oxford: Pergamon, 1982.

- Stoffers, Manuel. “Cycling, Sustainability, and the Problem of Societal Change.” Transfers. Interdisciplinary Journal of Mobility Studies 4, (2014): 163–165.

- Tewdwr-Jones, Mark. “Oh, the Planners Did Their Best: The Planning Films of John Betjeman.” Planning Perspectives 20, no. 4 (2005): 389–411. doi:10.1080/02665430500239448.

- Urry, John. Sociology Beyond Societies: Mobilities for the Twenty-First Century. London: Routledge, 2000.

- Urry, John. “The ‘System’ of Automobility.” Theory, Culture & Society 21, nos 4–5 (2004): 25–39. doi:10.1177/0263276404046059.

- Vigar, Geoff. The Politics of Mobility: Transport, the Environment and Public Policy. London: Spon, 2002.

- Williams, Raymond. The Country and the City. London: Chatto and Windus, 1973.