ABSTRACT

This contribution opens a new perspective on the politics of urban redevelopment in Dutch and German cities during the 1960s and early 1970s. More specifically, it examines the post-war expansion of Bredero, a Dutch private developer that forged public–private partnerships with the city councils of Utrecht and Hannover to get local urban redevelopment agendas of the ground. Within the period covered by this article, the political consensus was that the post-war economy, which was dominated by rising car ownership, business and consumerism, had to find its place and thrive in central urban areas. Developers such as Bredero were thought to dispose over the expertise and financial means to swiftly execute redevelopment schemes. Up until now, planning historians have largely neglected the role played by private developers in post-war urban redevelopment efforts. This contribution investigates how and why local administrators and private developers decided to work together in the first place, and how the expertise of Bredero in particular was translated into the development of Utrecht’s Hoog Catharijne and Hannover’s Raschplatz schemes. Through the innovate use of hitherto under-examined primary sources, this contribution sheds a new light on the allegedly recent phenomena of the internationalization and outsourcing of urban planning efforts.

Introduction

Every enterprise has to sell its business activities in such a way that the community becomes willing to pay their asking price with pleasure. This is only possible after the needs for certain services and goods have been established. Therefore, the primary duty of a businessman is to detect those needs.Footnote1

Developed and constructed between 1962 and 1973, the Hoog Catharijne scheme was a typical product of post-war urban planning. At the time it was conceived, most planners in the Western world agreed that the post-industrial economy, which was dominated by business, finance, and consumerism, had to find its place and thrive in central urban areas.Footnote2 In order to accommodate a growing number of cars, increasing amounts of office space, and more retail and shopping venues, municipalities all over Western Europe considered redevelopment schemes similar to Hoog Catharijne.Footnote3 By doing so they thought they could simultaneously get rid of a dilapidated housing stock and reinforce the economic strength of their urban cores. This agenda was put forward and implemented by a pro-growth coalition of politicians, civil servants, planners, and last but not least, private developers. This urban redevelopment order was a convergence of forces typical of Western European urban governance at the time, in which government agencies and private enterprise worked closely together to get their plans of the ground.Footnote4

Although the rise of the post-war urban redevelopment order has been well documented by planning historians, the involvement of private developers has been addressed only marginally, in particular when it comes to the period in which Bredero was operating. In general, literature focuses on either local politics or design, usually by adopting a case-study approach based on official government records.Footnote5 Research on private involvement in the urban redevelopment operations of the 1960s and 1970s has hitherto been left to a small number of real estate experts and social geographers, who tend to demonise developers to the point of caricature, leaving little room for considerations on the worldviews of companies and the professional backgrounds of the individuals working for them.Footnote6

The most notable exception in the Dutch context is the work of historian Hans Buiter, who has published a comprehensive monograph on Hoog Catharijne and contributed to a business history of Bredero, both written in Dutch. Buiter provides revealing insights into both the decision-making process leading up to the construction of Hoog Catharijne and the company’s modus operandi between the appointment of Jan de Vies in 1947 and Bredero’s bankruptcy in 1987.Footnote7 Although Buiter occasionally takes into account the company’s foreign enterprises, his approach is predominantly local, with little reflection on broader developments in society. Consequently, Bredero’s accomplishments and international operations are only marginally tied into the urban redevelopment order and its post-war agenda for the inner cities. It should be emphasized here that Bredero was operating on a much larger and more professional scale than most post-war developers, who have often been stereotyped – usually with good reason – as speculative profit extractors. Still, Bredero was not one of a kind, as might be exemplified by the work of property development firms such as the Canadian Olympia and York firm, Britain’s Arndale Properties or Germany’s Neue Heimat building association.Footnote8

The little attention private developers have received in historiography is remarkable, as these entrepreneurs were able to transform material resources into new structures of social life, hereby providing post-war urban society with the buildings it needed to prosper. In the international context, important contributions have been made by political theorist Susan Fainstein, who has examined the work of private developers in New York and London between 1980 and 2000, and by Peter Shapely, a British historian of post-war urban planning.Footnote9 Whereas Fainstein focuses on market dynamics through quantitative data and interviews with key players in local property, Shapely is more interested in the political side of public–private partnerships and thus concentrates on government archives instead of company records. From a more theoretical perspective, Harvey Molotch’s work on local growth machines provides a useful starting point for examining public–private partnerships such as the ones forged by Bredero.Footnote10 However, the growth machine thesis is firmly based on the American experience of urban redevelopment, and is therefore only applicable as a lens through which to examine European developments.Footnote11 Consequentially, planning historians are left with a rather fragmented body of literature in which the intrinsic links between the post-war urban redevelopment agenda and private enterprise are only covered piecemeal.

In this contribution, I will argue that private developers should be more firmly embedded in the historical narrative of post-war urban redevelopment for three interrelated reasons. Firstly, during the 1960s and 1970s, the expertise and financial strength of private developers proved decisive for the execution of redevelopment schemes in numerous Western European cities and towns. A substantial part of our modern built environment has come into existence at the initiative of developers, or was at least constructed with their aid, so it should only be natural to study our environs bearing this in mind. Secondly, government bodies and the private sector were heavily reliant on each other to get building projects of the ground. By examining their ties, historians can shed a new light on the allegedly recent phenomena of the internationalization and outsourcing of urban planning efforts. This market-oriented perspective gains even more relevance when taken into account the almost unlimited power social-democratic parties exercised in national and local governments at the time, exemplifying how in the immediate post-war years left-wing politicians had come to accept the market for efficiency reasons. Thirdly, as many private developers operated globally, they might have played an equally important role for the dissemination of ideas on urban planning and real estate development as more orthodox channels of knowledge transfers such as international conferences and academic journals.

To substantiate these arguments, I will investigate Bredero’s company profile, practices, and public–private partnerships from 1962 to 1975. This period covers both the zenith of urban modernism and the firm’s commercial heydays, which coincided with the development and construction of its two largest redevelopment schemes: Hoog Catharijne (1962–1973) in the Dutch city of Utrecht and the Cityerweiterungsprojekt Raschplatz in the German city of Hannover (1969–1975). The reasons for focusing on Bredero are twofold. Firstly, during the 1960s Bredero became the first and most important developer of commercial real estate in the Netherlands, earning respect for its scientific expertise and international experience.Footnote12 By establishing development and real estate branches, Bredero brought together planning expertise and great financial resources.Footnote13 This enabled the company to initiate and finance highly complicated, long-term redevelopment schemes, of which both Hoog Catharijne and Raschplatz were textbook examples. Secondly, due to Bredero’s bankruptcy in 1987 and the subsequent transfer of company records to a local archive, partial access has been granted to a wealth of information. With the exception of Buiter, historians have not yet made use of this unique opportunity to investigate decision-making at the highest levels of Dutch real estate.

Through an innovative use of Bredero’s company records, this contribution aims to open up new perspectives on the urban redevelopment agenda of the 1960s and early 1970s. The records hold invaluable information about the company’s planning methods, expansion strategies, and corporate worldviews, which are collected in brochures, prospectuses, and unpublished interviews with leading figures. These under-examined sources allow for a reconstruction of Bredero’s road to riches. Council archives in both Utrecht and Hannover have been consulted to investigate how the company setup its public–private partnerships. Minutes from political meetings, correspondence between elected officials and civil servants, and plans drawn up by local planning departments demonstrate how municipalities were eager to forge far-reaching alliances with Bredero. To triangulate these primary sources, contemporary newspapers and booklets have been examined, complemented by the small body of literature on the role of private enterprise in Dutch urban redevelopment. The involvement of a wide range of actors requires an actor-centred approach, which allows me to emphasize the importance of the professional backgrounds and international experience of Bredero representatives in building and supporting cross-border alliances.Footnote14 The actor-centred, international approach is in line with recent and more dated forays into the transnational dissemination of planning ideas and calls for more attention to the role of private entrepreneurship in the redevelopment of city centres.Footnote15 Andrew Harris and Susan Moore have argued for a long-term perspective on the circulation of urban knowledge and policies, which are disseminated through conferences, publications and study tours.Footnote16 Rosemary Wakeman recently called for planning historians ‘to train their scholarly lenses on the partnerships between the state and municipal entities as planners and transnational enterprises as builders, and how these alliances were carried out on a global scale’.Footnote17 This contribution assents to both calls for broadening our research scope, complementing these by demonstrating how transnational enterprises such as Bredero were equipped to both plan and build, while in the process transferring knowledge from one country to another.

This contribution is divided into four sections. In order to answer the questions as to how and why the public and private sector wanted to cooperate on the issue of urban redevelopment in the first place, the first section investigates the Dutch post-war context in which agendas were set and developers could thrive. Here, facts and figures on urban redevelopment's challenges and solutions are linked with the rise of the private developer as a powerful figure in post-war planning history.Footnote18 The second section focusses on Bredero’s expansion during the 1960s by respectively taking into account the company’s expertise, financial means, and technocratic worldview. In the third section, I will discuss how these assets were translated into the development and construction of Hoog Catharijne, and in which ways the professional backgrounds of key figures solidified Bredero’s partnership with the city of Utrecht. Whereas Hoog Catharijne will serve as an illustration of Bredero’s planning skills, the Cityerweiterungsprojekt in Hannover is introduced to demonstrate how these skills were exported abroad.

The rise of the private developer

As the Netherlands was growing more affluent during the 1960s, the demand for services and consumer goods grew exponentially. The advent of post-industrial society proved highly influential for the future of inner cities, where more space was required for respectively cars, offices, and shopping venues. These three demanders of urban space stood at the core of the first post-war redevelopment efforts. To understand how Hoog Catharijne came about as a result of the affluent society and how it exemplified broader trends in real estate, we need to briefly address the scheme’s underlying economic forces and governmental responses before moving our focus to the local context.

The 1960s was a decade of prolific economic growth and rapid urban change for Dutch cities and towns. Between 1960 and 1970, the number of cars and commutes by car in the Netherlands increased fivefold.Footnote19 Over the same decade, the number of newly developed square metres in shopping space more than doubled in comparison to the 1950s, with retail traders scaling up and introducing new selling and distribution methods.Footnote20 From 1960 to 1970, the number of jobs in the service industry grew by 220,000, owing in particular to the provision of new financial products by the banking and insurance sectors.Footnote21 Whereas office workers were thought to need 17.5 m² of space in 1950, during the 1960s this number grew to 25 m² per person.Footnote22 Despite growing suburbanization tendencies, most businesses wanted to retain their central location, or as a group of economists concluded on the functioning of inner cities in 1961: ‘Besides the architectural and aesthetic elements, being part of life and the ability to witness and experience dynamic change is what makes our city centres stand out from modern shopping centres’.Footnote23

These mounting economic pressures on the inner cities forced the Dutch Ministry of Housing, Physical Planning and the Environment (hereafter: the Ministry of Physical Planning) to take a more proactive stance on local planning matters, mainly by the establishment of new agencies, legal frameworks, and setting out rights and duties. In 1958 the Ministry of Physical Planning pledged more financial support for urban redevelopment efforts.Footnote24 Four years later, it provided local municipalities with more freedom in determining the future of built-up areas with the Physical Planning Act, which introduced binding land-use plans.Footnote25 The land-use plans were drawn up by local planning departments, over which an alderman presided who was held accountable by a local city council.Footnote26 In practice, the urge to accommodate the affluent society within the inner city led these departments to designate centrally located working-class districts as redevelopment areas – a decision that was encouraged by the poor construction quality of tenement houses and favourable land prices.Footnote27 By doing so, local planners thought they would save historic districts from destruction while simultaneously replacing the seemingly worthless legacy of the Industrial Revolution with the shimmering symbols of a new economy.

At the same time as national and local governments were determining the urban redevelopment agendas of larger Dutch cities, a reconfiguration in the supply and demand of real estate took place. Private developers and institutional investors played a key role in this reshuffling. Dutch private entrepreneurs had been engaged in the real estate business since the last quarter of the nineteenth century, mainly by buying, developing, and selling building plots for third parties. Up until the Second World War, these projects usually concerned small-scale housing developments outside of built-up areas.Footnote28 Commercial developments such as office blocks and shopping venues were usually commissioned and paid for by their end users.Footnote29

During the 1950s and 1960s, the relationship between the builders and users of buildings gradually changed for two interrelated reasons. Firstly, service providers and retailers increasingly preferred renting over self-building their premises. Rented floor space was more efficient, flexible, and cheaper, especially as wages and construction costs were on the rise.Footnote30 Developers tapped into this demand by launching real estate projects, selling or retaining buildings as assets to produce cash flow. Operating on their own initiative and risk, developers traced market demand and arranged designs as well as financial resources.Footnote31 The career of many post-war developers mirrors the transition from a predominantly industrial to post-industrial economy. For example, by the early 1960s the Amsterdam port company Blauwhoedenveem had begun to convert vacant warehouses to office space, whereas a local developer by the name of Maup Caransa switched from buying and selling military dump goods and harbour cranes to investing in real estate.Footnote32

Secondly, institutional investors grew more interested in acquiring property portfolios, which could absorb economic downfall and curb inflation.Footnote33 The Dutch central government encouraged this development by allowing its own pension fund to invest in real estate from 1956 onwards, as well as by lifting the price control of building plots in 1962.Footnote34 Consequentially, around this time surplus capital was increasingly moving into the circuit of commercial real estate development.Footnote35 The implicit and explicit relations between state and private enterprise demonstrate how property investments become more appealing at times when governments guarantee long-term, large-scale enhancements in the built environment, of which the post-war urban redevelopment agenda is a prime example.Footnote36 This illustrates why planning historians should pay more attention to the interplay between political and commercial powers, or as David Harvey states:

It is unfortunate that much of the literature concentrates so much on [urban government, TV] when the real power to reorganise urban life so often lies […] within a broader coalition of forces within which urban government and administration have only a facilitative and coordinating role to play.Footnote37

Already by the early 1960s the Ministry of Physical Planning showed itself surprised to see so many private developers reinforcing its urban redevelopment agenda. In 1964, ministry officials spoke of the ‘spectacular construction activities’ of firms with ‘unprecedented financial means’, which were taking larger Dutch cities by storm.Footnote38 Over the 1960s, Amsterdam’s social-democratic aldermen were eager to kick-start their redevelopment programme by granting planning permissions to several local entrepreneurs, who proposed spacious office blocks on the inner city’s fringes paid for by the Philips Pension Fund.Footnote39 In The Hague, an American-styled local businessman presented a vast redevelopment scheme for the inner city, encompassing a 140-metre tall office tower, a six-storey parking garage, a 400-bed hotel, as well as several catering, entertainment and shopping facilities. The Hague’s city officials were delighted to outsource their urban redevelopment programme, and swiftly joined forces with the developer to evict local tenants. These plans demonstrate how developers were capable of reinforcing or even setting local redevelopment agendas through inside contacts with local planning officials, who preferred cooperation with home-grown entrepreneurs over partnerships with unknown outsiders due to the formers’ knowledge of local sensitivities and planning procedures.

Brains, money, and pushing power

In addition to being the most ambitious redevelopment scheme ever carried out in the Netherlands, Hoog Catharijne was first and foremost a prestige project meant to boost the company profile and turnover rates of its initiator, Bredero. Before explaining the scheme’s characteristics and political reception, it is important to examine the company’s self-image and reputation, especially since its unique selling point was an internationally experienced and scientifically trained staff. As this section will demonstrate, the company’s avant-garde position and planning bravado was decisive for winning the confidence of local politicians in Utrecht, or as one journal commented on the Hoog Catharijne scheme in 1964: ‘Every realistic city council would be delighted when an initiator would come to the fore with brains, money and pushing power, especially one who is convinced that he can do the job within a time span of ten years’.Footnote40

Bredero’s brains, money, and pushing power were consciously and intrinsically linked to each other, its road to power paved by the visions of its leading figures. Jan de Vries, who served as the company’s CEO from 1947 until 1977, was trained as a mathematician and physicist, earning respect for his work on the first successful nuclear fission in Interbellum Berlin. After his appointment in 1947, Bredero quickly gained global experience in real estate development, prefabrication and utilities construction, with employees working as far as Australia, Indonesia, and Iran. These international operations maximized profits and minimized cyclical sensitivity, as different countries experienced economic upturns and downturns at different moments in time.Footnote41 To further strengthen Bredero’s position at the home front, De Vries fulfilled countless commissionerships and executive roles within advisory boards of Dutch multinationals.Footnote42 In 1961 he appointed Adam Feddes as head of Empeo, Bredero’s development branch. Feddes was trained as an engineer but experienced as a management consultant and civil servant working for Amsterdam’s housing department – invaluable experience for a private developer.Footnote43

Bredero aimed less for immediate profits than for the long-range development of productive forces, of which its recruitment policies and international operations spoke volumes. With its own development branch, headed by Feddes, the company could achieve independence from its patrons and greater business continuity. Empeo distinguished itself from other Dutch developers through the radical ideas and expert knowledge of its employees, gained from young academic disciplines such as organizational studies and social geography. Feddes recruited a team of renowned urban planners, geographers, and economists, who calculated and spatialized future consumer needs and purchasing power in numerous Dutch localities.Footnote44 A strong sense of the Netherlands’ international position and advanced linguistic skills allowed his personnel – and Dutch planners in general – to have good contacts with neighbouring countries such as Britain and Germany. Some of them even received educational training abroad and took part in study trips to the United States, organized by the national Social and Economic Council (SER), aiming to achieve a better understanding of the latest international fashions in urban planning.Footnote45 A contributing factor to Bredero’s appeal was the inexperience of local planning departments, which were usually understaffed or even non-existent. In 1970, only 27 out of a total of 900 Dutch municipalities had an independent department for public works at their disposal.Footnote46 During the 1960s and 1970s, none of the aldermen working in the large conurbations was trained as a planner. Indeed, Bredero’s expertise was only matched by the planning departments of Amsterdam and Rotterdam.

Redevelopment schemes such as Hoog Catharijne and other long-term building projects did not materialize by brains alone. In 1963 Bredero set up its own real estate branch, which was engaged in the buying and selling of profitable immovable properties. According to the shareholders’ prospectus the property market could provide Bredero with the financial resources needed to sponsor Empeo’s research, labelling this interlocking of entrepreneurship and real estate development as ‘the production of space’.Footnote47 Bredero boastfully compared its strategies to the workings of an assembly line. For Jan de Vries, this cookie cutter perspective on the built environment was something to be proud of: ‘Fundamental research is just as important for the responsible production of space as it is for the production of industrial goods’.Footnote48 Such statements charmed shareholders looking for new investment opportunities, as exemplified by the national banks and pension funds participating in the financing and leasing-out of Hoog Catharijne.Footnote49 Partially due to the scheme’s critical acclaim, Bredero was able to quadruple its annual turnover rates between 1960 and 1970.Footnote50

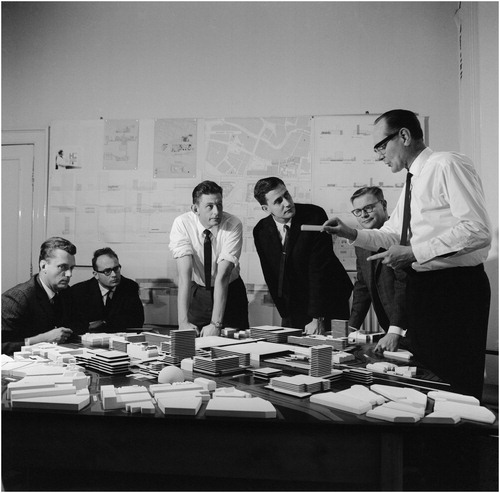

After acquiring the brains and the money, the firm was still in need of pushing power to make things fall into place. Technocracy was key to Bredero’s company profile. For experts such as Feddes and De Vries, technocracy was not just the application of technical modes to the solution of defined problems in the built environment, but a pervading ethos which subsumed customs and political decision-making to the rationalistic mode.Footnote51 The ‘irrational’ decision processes of democratic politics, i.e. bargaining and compromise, were to be replaced with ‘rational’ analytical methodologies of scientific decision-making. Bredero employees defined their tasks in the field of urban redevelopment in apolitical terms, committing themselves to technological progress and material productivity instead of questions about aesthetics and social justice.Footnote52 Through their web of connections and financial donations to both political parties and charity organizations, these entrepreneurs were able to further grease the wheels of development ().Footnote53

Hoog Catharijne: a glimpse of tomorrow

When Bredero launched its Hoog Catharijne scheme in 1962, the centrally located city of Utrecht counted some 250,000 inhabitants. Just as any other Dutch conurbation in the western part of the country, by the late 1950s Utrecht had begun to experience rapid economic growth and increasing suburbanization tendencies. In combination with a steep rise in car ownership, this led to increasing congestion and fears of a dwindling viability of the inner city’s businesses and shopping venues.Footnote54 Because traffic was at the core of Utrecht’s planning issues and Bredero capitalized on these in particular, this section will discuss both Hoog Catharijne and its preceding urban redevelopment efforts.

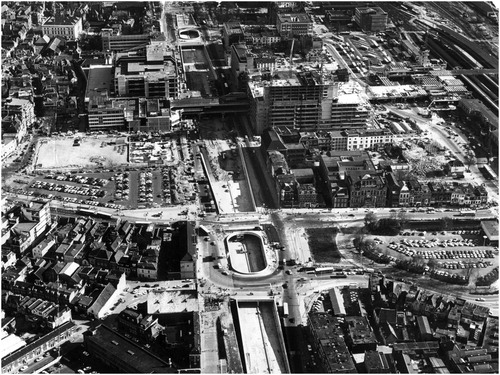

Around the mid-1950s, the dawning of the motor age began to alarm Utrecht’s officials. Between 1950 and 1959 the number of cars in the city more than tripled, with expectations of another quadrupling between 1960 and 1970.Footnote55 Due to the inexperience of his own staff members, Wim Derks, the city’s alderman for spatial planning, invited the German engineer Max Feuchtinger to investigate Utrecht’s traffic needs. In 1958, Feuchtinger proposed to intersect the inner city with four arterial thoroughfares, and to fill in the city’s outer canal to provide space for a ring road with multiple interchanges.Footnote56 After criticism from city councillors and preservationists who demanded an overall vision for the inner city’s future, the Dutch traffic engineer Johan Kuiper was appointed to accomplish Feuchtinger’s plan. In 1962 Kuiper presented a scheme in which most of the inner city and outer canal were left intact, instead proposing a new business district on the inner city’s fringes.Footnote57 The planning department preferred Feuchtinger’s vision: Utrecht’s office clerks were to be given ample opportunity to have lunch and buy groceries in the inner city, for which Kuiper’s business district was thought to be too far away.Footnote58

The discussions over how to accommodate car traffic within the inner city were crucial for Bredero’s later involvement, as it paved the way for the city’s acceptance of experts working outside its own planning department. Alderman Derks showed himself to be easily charmed by this outside expertise, as might be exemplified by his response to Feuchtinger’s critics: ‘This diagnosis has been made by an expert, wholly objective, as if a doctor has diagnosed a vital organ with a serious infection’.Footnote59 Moreover, the car-centred discussions led local stakeholders to believe the inner city was in need of an overall vision, of which traffic was just one aspect. Despite their differences, both proponents and opponents of the traffic schemes were united in their calls for saving the inner city’s economic viability. Eventually, the schemes by Feuchtinger and Kuiper even triggered a path-dependent planning process, characterized by a chain of political decisions in which giving way to the car was seen as an inevitable outcome.

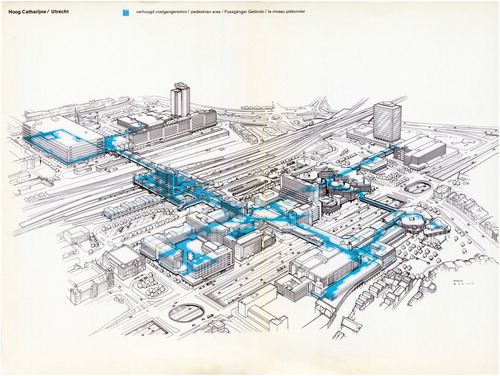

The first semi-public discussion of Hoog Catharijne was triggered by parking problems. On 20 March 1962 Bredero called a private meeting with the city’s mayor, alderman Derks and representatives of the national railways, which were struggling with the capacity of its parking lots near Utrecht’s central station. During this meeting the Utrecht-based construction company presented the very first contours of Hoog Catharijne, a master plan dealing with its hometown’s growing pains all at once, so Jan de Vries argued. The scheme encompassed the redevelopment of the central railway station and an adjacent nineteenth-century district, the construction of multiple parking garages and an elevated indoor pedestrian area that would connect new businesses and shopping venues to the old inner city. A partial filling in of the outer canal and the notion of a central business district, both elements of Kuiper’s vision, were incorporated to prevent twice the same work being done. In sum, 200.000 square meters of new developments were to replace 246 housing units and 161 small businesses, which were located in four densely built city blocks. With these features, Hoog Catharijne was suited to accommodate both the emerging services-based economy and the rapid growth in car ownership. Provided Bredero would be commissioned to execute the plan, CEO Jan de Vries promised to let Empeo elaborate on his ideas, a provision that was accepted as reasonable by the other attendees.Footnote60

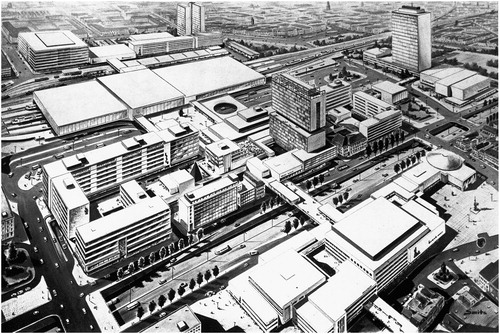

With its combination of innovative organization and design, Bredero had presented its potential partners an offer they simply could not refuse. After the plan was officially published in October 1962 virtually all parties involved, including citizens, praised the plans for Hoog Catharijne. The widespread enthusiasm might be exemplified by a local art journal, which exclaimed: ‘It’s a good thing private enterprise is doing something at least, and that something surpasses even the municipal executive’s wildest dreams. Protesting against this plan means further waiting, which in Utrecht means waiting for Godot’.Footnote61 The final version of the scheme encompassed 130,000 square metres of shopping and office floor space as well as 60,000 square metres of traffic amenities, exhibition spaces, and hotel facilities. A flashy brochure also announced the construction of 280 luxurious apartments catering for modern city dwellers, whose interior lighting could give Hoog Catharijne a ‘vibrant night-time appearance’.Footnote62 In the preface to the same brochure, the city’s mayor praised the merits of public–private partnerships, demonstrating how politicians are always depending on the private sector to finance economic growth.Footnote63 During the years Hoog Catharijne was under construction, city officials would repeatedly express their satisfaction over the harmonious way in which the scheme had come into existence ( and ).

Figure 2. Signing of the contract (1964). Sitting on left-hand side: Utrecht’s mayor Coen de Ranitz. Right-hand side: Bredero’s CEO Jan de Vries.

The design and programming of Hoog Catharijne had come about as a combination of Dutch entrepreneurship and ideas circulating in the international field of urban planning. The most influential source was Victor Gruen, an Austrian-American architect working in the United States. During the 1950s, Gruen had proposed pioneering ideas on pedestrianizing inner cities and designing shopping centres. Gruen’s paradises of consumption were meant as an intimate and pedestrian-friendly answer to the emptiness of their suburban surroundings.Footnote64 Empeo employees subsequently combined the ideals underpinning the work of Gruen with their international experience, which was gained over the 1950s during workshops hosted by Australian and American organizations.Footnote65 Additional sources of inspiration concerned redevelopment schemes such as London’s Euston Station, Paris Montparnasse, Birmingham’s Bull Ring Centre, and Stockholm’s Hötorgscity, which were all geared towards providing commuters and consumers quick and easy access to centrally located offices and shops.Footnote66 To observe the work on these and other projects at first hand, at the discretion of Empeo Utrecht city councillors undertook several study trips to these and other cities.Footnote67 By doing so, the private developer offered its political ally a glimpse of the future of their hometown, simultaneously solidifying their public–private partnership.

As has been highlighted, the main reason for Hoog Catharijne’s positive reception lay in a lack of expertise on the side of Utrecht’s planning department. Three additional reasons for the local ardour should be mentioned here. Firstly, Bredero proposed to not only integrate the construction process from start to finish, but also to finance the scheme. This was done by teaming up with an investment banker and drawing up a ground lease contract.Footnote68 The latter ordered the city of Utrecht to provide infrastructure and to buyout landowners, after which Bredero would return the costs by leasing the publicly acquired plots over a 100-year time span.Footnote69 It was an agreement beneficial for both parties, since the city could profit from increasing land values whilst maintaining a right of say over the planning area, while Bredero was relieved from an immediate financial burden.Footnote70

Secondly, both alderman Derks’ and his successor Theo Harteveld’s personal and party backgrounds solidified the agreement with Bredero. Whereas Derks’ party had inherited strong ties with the construction industry from the immediate post-war years,Footnote71 Harteveld was trained as a physicist and had acted as CEO of a publically owned gas company before his political appointment. Harteveld’s social-democratic party was equally on the hands of the construction industry for the sake of economic expansion and job growth.Footnote72 Without exception, aldermen responsible for urban planning in the four major Dutch cities were all members of the Labour Party during the 1960s and 1970s, making urban redevelopment a social-democratic project par excellence.Footnote73 The party’s first post-war manifestos had already called for a scientific approach to planning matters and a mixed economy, in which there was room for both a strong public sector and capitalist modes of production.Footnote74 This demonstrates how the Dutch polder model of consensus decision-making in economic affairs, which is usually associated with the rise of neoliberalism during the 1980s and 1990s, has long historical roots in the field of planning.Footnote75

In the third place, local officials were clearly short on civic pride, and wanted to propel Utrecht’s image from the provincial capital it had always been into a bustling metropolis. Prior to Hoog Catharijne, even the mayor described his city as having a ‘dull, small-town mentality’, calling for a competitive battle with other major cities for economic growth and prestige.Footnote76 Similar sounds of discount could be heard outside of city hall as well. A 1958 city guide said Utrecht lacked ‘vibrancy’ and ‘elegance’, while in 1962 a local architecture critic described his hometown as a ‘small but charming medieval reserve, surrounded by a boring and provincial village’.Footnote77 As the smallest of the country’s four major cities, Utrecht was clearly struggling with its self-image. Still, given its central location and its function as a national transport hub, the city had great potential ().

Considering these local circumstances, it should come as no surprise Hoog Catharijne was supported by an overwhelming political majority. According to De Vries, all requirements for future economic growth within the inner city were met – Utrecht had been waiting for a feasible redevelopment proposal such as his.Footnote78 In 1963, out of 45 city councillors only 2 voted against the public–private partnership, thus making Bredero a power broker in local politics.Footnote79 One councillor described the feeling of momentum as ‘a clap of thunder in a clear sky’, with Empeo hitting the right nerve.Footnote80 After green light was given, the developer set out to collect more facts and figures on Utrecht’s growth potential. An enquiry with almost 3000 respondents demonstrated how the regional consumer market for durable goods was expected to grow with a stunning 90%.Footnote81 Hoog Catharijne was poised to accommodate 60% of Utrecht’s expected growth in office and retail space over a 10-year period, by which the suburbanization of shops and offices was rechannelled into the inner city.

The information coming from Empeo’s enquiries and surveys was directly translated into design. As vice-chairman of the local board of commerce, De Vries personally pushed for a pedestrian-friendly inner city, from which he expected increasing flows of consumers headed to his indoor shopping centre, where skilfully designed pedestrian routes led people along seemingly endless rows of display windows.Footnote82 During lunch hour and after work, clerks and secretaries employed in the offices above the shops would supplement a lively crowd of commuters and day trippers.Footnote83 The scheme’s modular architecture resembled an expandable megastructure, ready to accommodate future growth.Footnote84 Through meticulous and unrelenting planning methods, devised by a former Royal Dutch Shell employee who used to work on the exploitation of oil fields, Hoog Catharijne was to be completed in timely fashion.Footnote85 Between 1965 and 1973 the area in between Utrecht’s central station and its old inner city was turned into an enormous construction site ().

‘Wer plant, soll nicht bauen’

As the construction of Hoog Catharijne got underway, Bredero started expanding its activities at home and abroad even further. The exuberance for the shopping and office complex seemed omnipresent, with Utrecht receiving officials from cities all over Western Europe.Footnote86 During the late 1960s and early 1970s, Bredero proposed similar schemes for German and British cities, whilst the company’s real estate branch ventured into adventures on American soil. The company’s utilities branch even specialized in the construction of nuclear reactors, magnifying Bredero’s reputation as a scientific producer of space. Flashy brochures and promotional videos praised the company’s virtues in English, German, and French, presenting Hoog Catharijne as a flagship development and the ultimate social city: ‘A place to shop, to live, to dine, to work, to drink, to stroll, to play, to sit, to read, to watch the world go by. Because Hoog Catharijne has been built for the people’.Footnote87 Such marketing slogans seemed to have effect, as several German cities asked Empeo to investigate the redevelopment of their central districts.Footnote88

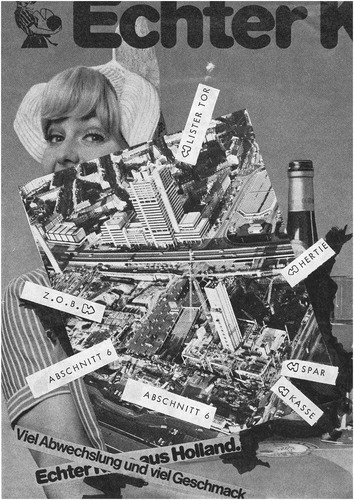

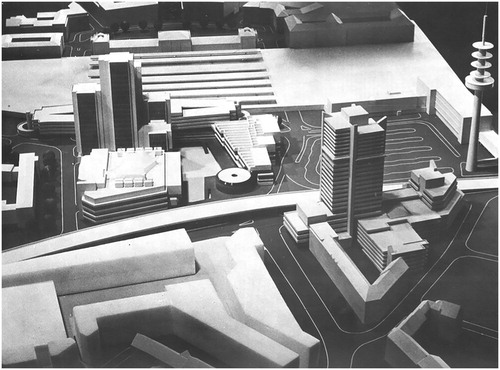

After a delegation headed by famous urban planner Rudolf Hillebrecht had concluded Bredero was doing excellent work in Utrecht, in 1969 the German city of Hannover was the first to embark on a joint venture with Bredero.Footnote89 Different than its Dutch counterpart, the mid-sized city in Lower Saxony was heavily bombed during the Second World War. This provided Hillebrecht and his planning department with a clean slate on which a truly car-centred city could be created, demonstrating how the car was at the core of urban redevelopment efforts in both Germany and the Netherlands.Footnote90 In accordance with this redevelopment agenda, Bredero’s Cityerweiterungsprojekt Raschplatz encompassed the construction of shops, offices, and parking garages, its showpiece being a 300-foot, mixed-use skyscraper. The company marketed the project by using the imagery of ‘Frau Antje’, a Dutch character usually used in the advertising of cheese and other dairy products ().

Once again, political pushing power and in-house expertise proved pivotal for Bredero. Its partnership with Hannover’s municipal executive was favoured by the city’s twinning with Utrecht in 1971, which fostered formal and informal contacts between local politicians, civil servants, and business communities.Footnote91 In his capacity as vice-chairman of Utrecht’s chamber of commerce, De Vries probably lobbied for twinning both cities himself. Hillebrecht was certainly impressed by such moves. He labelled the company’s leading figures as ‘well-organized, economical, correct and fair’ negotiating partners. Transatlantic study trips had given the German planner the impression that American and Canadian developers were not as specialized in comprehensive redevelopment and not as technologically advanced as Bredero. Equally important, Hillebrecht expected cultural differences and the language barrier to be problematic for a close collaboration.Footnote92 Furthermore, Hannover’s chief planner thought German developers who were already operating in his hometown would become either too powerful or overwhelmed by yet another opportunity.

Some local stakeholders in Hannover, however, were lambasting the Dutch-German alliance for exactly the same reasons. Despite setting up a branch office in Hannover to improve their business ties and community relations, the arrival of the Dutchmen was met by some with doubt and resistance. Local architects and contractors raised concerns over the city’s loyalty to their entrepreneurship and craftsmanship. In 1970, the ‘Architektenkammer Hannover’ stated that German architects should have been given a fair chance in submitting proposals for the redevelopment site.Footnote93 Much to Bredero’s discontent, the Architektenkammer reinforced its arguments by mentioning the first protests against Hoog Catharijne, about which they had learned through a German journal on architecture and urban planning.Footnote94 Sharing similar sentiments, the ‘Verband der Bauindustrie für Niedersachsen’ found it unacceptable that Bredero was in charge of planning, designing as well as executing the scheme: ‘Our building industry is capable enough; the cost-increasing involvement of a foreign partner is wholly unnecessary’.Footnote95

Even more important than this unwelcoming atmosphere were the changing tides in the field of urban redevelopment. Since Bredero had launched its first plans for Hoog Catharijne in the early 1960s, a younger generation of planners and action groups had come to the fore with radically different ideas on the future of inner cities. With a political focus on participation, equal say and social activism, private developers and construction companies were increasingly seen as undemocratic bodies with illegitimated power over people’s living environment.Footnote96 In Hannover, the suspicion of backroom politics was reinforced by Bredero’s frequent invitations to study trips – Hillebrecht was even asked to join a journey to Japan.Footnote97 While these invitations could still be defended as a rational conduct of business, more informal contacts between De Vries and Hannover’s councillors led to allegations of bribing.Footnote98 It turned out two councillors had joined Bredero’s CEO on a private sailing trip to a Dutch new town, aboard gladly accepting refreshments in the company of their wives.Footnote99 No punitive measures were taken, but such get-togethers were clearly at odds with municipal codes of practice.

In 1973, the same year as Hoog Catharijne opened to the public, the first stone of the Raschplatz project in Hannover was laid. At that time both the Dutch and the German redevelopment schemes were already much disparaged due to a combination of structural economic and demographic changes, calls for participatory planning and new insights into how cities worked. As the developments that necessitated urban redevelopment slowed down or took different directions, the proponents of the physical remaking of cities left the stage. In Hannover, the retirement of Hillebrecht, Bredero’s most fervent supporter, led to the cancellation of several planning arrangements. From the mid-1970s onwards, office developments were to be realized on the city’s fringes, which decreased demand in central locations. The bankruptcy of a department store that would serve as a crowd puller and the enforced rerouting of pedestrian flows meant less passers-by. Such detrimental local circumstances were only aggravated as the 1973–1975 recession unfolded, leaving Bredero with huge yearly losses on the Raschplatz project.Footnote100 In an ironic way, the company’s expansion abroad had accelerated both its rise and its fall as one of the most powerful developers in Western Europe ().

Conclusion

While it is the most local of political cultures that shaped the post-war urban environment, with outcomes at least partially contingent upon the ideas and decisions of policy makers, this contribution has demonstrated that planning historians could pay more attention to the modus operandi of private developers. Bredero was able to determine and execute urban redevelopment schemes that still dominate both the appearance and functioning of central areas in at least two mid-sized Western European cities. The Hoog Catharijne scheme proved to be extremely successful, in particular from an economic viewpoint, boosting visitor numbers while relieving Utrecht’s centre from traffic congestion and pressures on the local office and retail market. Ever since its opening in 1973, plans have been made and executed to amend some of the scheme’s design flaws, simultaneously adding extra office and shopping space while paying lip service to the latest trends in architecture and planning. As detailed in the last paragraph, the Raschplatz scheme was less of a success story due to bad timing and severe planning mistakes, which have led to multiple refurbishments.

Besides examining the involvement of private developers in the urban redevelopment operations of the 1960s and 1970s, this article set out to investigate how and why Utrecht’s and Hannover’s officials decided to work together with Bredero in the first place. The company’s ‘brains, money and pushing power’ were operationalized through an active promotion by its leadership. Strong personalities such as De Vries and Feddes persuaded local policy makers into redevelopment with facts and figures gained from social-scientific research, ushering in a new technocratic discourse on urban planning and real estate. Both case studies epitomise a strong consensus amongst Dutch and German officials about the merits of cooperating with private enterprise in the field of urban planning, notwithstanding their political affiliations. Harteveld’s and Hillebrecht’s professional backgrounds and sense of civic pride were decisive in forging their partnerships with Bredero. In the latter case, it was Hillebrecht’s admiration for the all-in-one redevelopment package, a shared language and similar approach to entrepreneurship as well as the mere four-hour drive between Utrecht and Hannover that cemented the cross-border partnership.

Finally, the aim of this contribution was to demonstrate how developers have been responsible for the international diffusion of ideas on urban planning and real estate development. The Bredero case study exemplifies that knowledge transfers were the result of two-way traffic between a much broader range of actors than assumed so far. Rather than through selective borrowing or imposition by the state, the export of ideas and practices from Utrecht to Hannover was driven by the economic expansion of one single company.Footnote101 For Bredero, working in an international context was a venture by which new orders and the latest knowledge on urban issues could be gathered. Experience from abroad was first put to work in the Netherlands, after which it found its way to other countries through political and professional networks, international study trips and transnational town twinning. This broadens our perspective on the agencies and mechanisms by which the diffusion of planning occurs, its fundamental causation, and the role of individual agency in particular.

Of course, the one problem historians face when researching private enterprise is the accessibility of archival material. With few exceptions, companies are usually not willing or able to share their archives. This is why Bredero has proven to be a rare but important case study, which however could only be investigated by complementing its company records with a wide variety of other primary sources. Further research into the work of developers and construction firms could probe into their responses to the critics of urban redevelopment and private involvement in urban planning, who gained a political foothold from the early 1970s onwards. The ensuing debate might provide new insights into how public officials became caught between the interests of private enterprise and the citizens they represented.

Acknowledgments

This contribution was largely written during research leaves at Fordham University in New York City and the Institut für Raumbezogene Sozialforschung in Erkner. I would like to thank Rosemary Wakeman, Christoph Bernhardt and Monika Motylinska for hosting me, Freek Schmidt for relieving me of my educational duties, and the Fritz Thyssen Stiftung for giving me the opportunity to work abroad. An earlier version of this paper was given at the European Association for Urban History conference in Helsinki, August 2016. The convenors of my session, Stefan Couperus and Philipp Wagner, as well as the participants provided me with helpful comments. Last but not least, I would like to thank my dear colleague Ingrid de Zwarte for proof reading.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Tim Verlaan is an assistant professor in urban history at the University of Amsterdam. Before obtaining his Ph.D. at the same university, he studied European Urbanisation at the University of Leicester and the Technische Universität in Berlin. This article is based on findings from his Ph.D. dissertation.

Notes

1 De Vries, “Het Dienen van de Gemeenschap,” 34.

2 Verlaan, “Dreading the Future,” 544.

3 See for an overview of urban redevelopment efforts in both the United States and Western Europe: Ward, Planning the Twentieth-Century City, 157–306.

4 Pierre, “Comparative Urban Governance,” 446–62.

5 See for a transatlantic approach: Klemek, The Transatlantic Collapse. See for the British context: Conekin et al., Moments of Modernity; Bullock, Building the Post-War World; Gold, The Practice of Modernism. See for the German context: Düwel and Gutschow, Städtebau in Deutschland. See for the French context: Wakeman, Modernizing the Provincial City. See for the Belgian context: Ryckewaert, Building the Economic Backbone. See for the Dutch context: Wagenaar, Town Planning in the Netherlands; De Liagre Böhl, Steden in de Steigers.

6 Saunders, Urban Politics; Bolle and Snepvangers, Spiegel van Onroerend Goed; Ter Hart, Commercieel Vastgoed; Van Gool et al., Onroerend Goed, Kersloot, Vijfenzestig Jaar Bouwen; Oude Veldhuis et al., Neprom 1974-2000; Ploeger, Regulating Urban Office Provision; Marriott, The Property Boom; Van der Boor, Stedebouw in Samenwerking.

7 Buiter, Hoog Catharijne; Ibidem, “Naar een Internationaal Bouwconcern”.

8 Pugh, “Olympia and York, Canary Wharf and What May be Learned”; Shapely, “Governance”; Kramper, Neue Heimat.

9 Fainstein, The City Builders; Shapely, “Governance”; Ibidem, “The Entrepreneurial City”.

10 Molotch, “The City as a Growth Machine,” 310; Logan and Molotch, Urban Fortunes.

11 Harding, “Elite Theory and Growth Machines,” 42–4; Jonas and Wilson, “The City as a Growth Machine,” 4.

12 Author Unknown, “Eigenlijk is Bredero Uitvinder,” 47.

13 Utrechts Archief (hereafter: UA), Archief Verenigde Bedrijven Bredero (hereafter: Archief Bredero), inv.no. 270, N.V. Maatschappij voor Projectontwikkeling Empeo, ‘Stukken Betreffende de Voorstudie naar de Oprichting van een Ontwikkelingsmaatschappij’ (21 November 1961); Ibidem, ‘Statuten Ontwikkelingsmaatschappij’ (13 October 1961); Bredero Vast Goed N.V., Overzicht van Projekten, 3; Dendermonde, Een Steen is een Steen is een Stad, 28.

14 Molotch, “The City as a Growth Machine,” 310.

15 Logemann, Trams or Tailfins; Klemek, The Transatlantic Collapse; Ward, “Re-Examining the International Diffusion,” 39–60.

16 Harris and Moore, “Planning Histories,” 1499.

17 Wakeman, “Rethinking Postwar Planning,” 160.

18 Berman, All that is Solid, 63.

19 Provoost, Asfalt, 65.

20 Kersloot, Vijfenzestig Jaar Bouwen, 69.

21 De Vries, “Economische Ontwikkelingen,” 13.

22 Kersloot, Vijfenzestig Jaar Bouwen, 46.

23 Stichting voor Economisch Onderzoek der Universiteit van Amsterdam, Het stedelijke Centrum, 29.

24 Werkcommissie Westen des Lands, De Ontwikkeling, 70.

25 Nederlands Instituut voor Ruimtelijke Ordening en Volkshuisvesting, Handleiding Voorbereiding, 195–8.

26 Korsten and Tops, “Het College,” 183–96.

27 De Liagre Böhl, Steden, 24.

28 De Klerk, De Modernisering, 166–95; Meurs, De Moderne Historische Stad, 313.

29 Van Gool, Onroerend Goed, 3.

30 Rijksplanologische Dienst (hereafter: RPD), Jaarverslag 1969, 85.

31 Kersloot, Vijfenzestig Jaar Bouwen, 72.

32 Rompelman, “1968/1969-2009,” 69.

33 Brouwer, “Belegging in Onroerend Goed,” 116–20; Daniels, Office Location, 59.

34 Ministerie van Volkshuisvesting en Bouwnijverheid, Rapport, 42; Vleugels, 85 Jaar ABP, 76.

35 Ploeger, Regulating Urban Office Provision, 9.

36 Harvey, The Urbanization, 7.

37 Harvey, “From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism,” 6.

38 RNP, Jaarverslag 1963, 68.

39 De Liagre Böhl, Amsterdam op de Helling.

40 Petri, “Hoog Catharijne,” 142.

41 Buiter, “Naar een Internationaal Bouwconcern,” 68.

42 Hans Leijte, “Scheuren.”

43 S.N., “Eigenlijk is Bredero Uitvinder,” 47.

44 Blekendaal, “Dertig Jaar,” 22.

45 Ward, Planning, 277. See for conclusions drawn from such study trips: Commissie Opvoering Productiviteit, Moderne Winkelcentra, 21; Luyckx, Het Winkelcentrum, 15.

46 Schuiling, De Inrichting, 53.

47 UA, Archief Bredero, inv.no. 106, Verenigde Bedrijven Bredero N.V., “Prospektus Bredero Vast Goed N.V.” (15 November 1963).

48 De Vries, “Misverstanden,” 3.

49 Beijer, Familie, 17; Vleugels, 85 Jaar, 76.

50 Buiter, “Naar een Internationaal Bouwconcern,” 86.

51 Giddens, The Class Structure, 258.

52 Fischer, Technocracy, 22.

53 Bornewasser, Katholieke Volkspartij, 367; S.N., “Bredero Biedt Huizenplan.”

54 Verlaan, “De in Beton Gegoten Onwrikbaarheid,” 186.

55 Buiter, “De Stad,” 14.

56 Feuchtinger, Verkeersplan, 12.

57 Kuiper, Eerste Rapport, 11; UA, Gemeentebestuur van Utrecht 1813–1969, inv.no. 16481, “Notulen van de Vergadering van de Fabricagecommissie” (23 May 1962) 102.

58 Blijstra, 2000 Jaar Utrecht, 299.

59 Buiter, “De Stad,” 20.

60 Buiter, Hoog Catharijne, 31.

61 Wiekart, “Het Plan-Dingemans,” 75.

62 N.V. Maatschappij voor Projektontwikkeling EMPEO, Plan Hoog Catharijne, 29.

63 Fainstein, The City Builders, 2.

64 Hardwick, Mall Maker, 1–7; Gruen, The Heart, 9–16.

65 Buiter, “Naar een Internationaal Bouwconcern,” 79.

66 Gold, The Practice, 121–3; Hall, Stockholm, 130–4.

67 UA, Gemeenteblad 1963, “Handelingen van 10 oktober 1963,” 664; Ibidem, Archief Dienst Openbare Werken, inv.no. 427, ‘Brief Hoofddirecteur van Openbare Werken aan College’ (23 January 1964), ‘Brief Hoofddirecteur van Openbare Werken aan College’ (29 May 1964), ‘Brief Hoofddirecteur van Openbare Werken aan College’ (1 June 1964).

68 Beijer, Familie, 17, 22; Schuyt and Taverne, 1950, 187.

69 UA, Gedrukte Verzameling 1963, no. 250, ‘Plan Hoog Catharijne’ (19 September 1963) 9.

70 Nelisse, Stedelijke Erfpacht, 193.

71 Bornewasser, Katholieke Volkspartij, 367.

72 Becker and Hurenkamp, “Op Zoek,” 73.

73 Nieuwenhuijsen, “Het Onderschatte Project,” 59–105.

74 De Galan, “Om de Kwaliteit van het Bestaan,” 64; Federatie Amsterdam van de Partij van de Arbeid, Mens en Stad, 75.

75 Shapely, ‘Governance,’ 1288–89.

76 Vos de Wael, De Ranitz, 43.

77 Romijn, Hier is Utrecht, 9; Wiekart, “Opinies,” 65.

78 N.V. Maatschappij voor Projektontwikkeling EMPEO, Plan Hoog Catharijne, 2.

79 Buiter, Hoog Catharijne, 47.

80 UA, Gemeenteblad 1963, “Handelingen van 10 oktober 1963,” 670,

81 N.V. Maatschappij voor Projectontwikkeling EMPEO, Winkelfunktie, 26.

82 Baudet, Utrecht in bedrijf, 55; De Widt, Aspecten, 114.

83 N.V. Maatschappij voor Projektontwikkeling EMPEO, Voetgangersonderzoek, 21.

84 Banham, Megastructures, 10; Spruit and Feddes, “Enkele Aspecten,” 49.

85 Buiter, “Naar een Internationaal Bouwconcern,” 81.

86 UA, Archief Bredero, inv.no. 216, ‘Gesprek Max Dendermonde met A.G. Smallenbroek, ambtenaar gemeente Utrecht’ (14 October 1985) 6.

87 N.V. Maatschappij voor Projektontwikkeling EMPEO, About Hoog Catharijne.

88 UA, Archief Bredero, inv.no. 33, ‘Notulen van de Algemene Vergadering van Aandeelhouders’ (3 May 1973).

89 Buiter, “Naar een Internationaal Bouwconcern,” 84.

90 S.N., “Das Wunder,” 61–3.

91 UA, Gedrukte Verzameling 1971, inv.no. 177, ‘Jumelage met de Stad Hannover’ (3 May 1971).

92 Stadtarchiv Hannover (hereafter: SH), Büro Stadtbaurat Hillebrecht, inv.no. 296, ‘Anlage 2 zu Drucksäche Nr. 1119/70’ (20 August 1969) 1–3; Ibidem, ‘Durchschrift’ (15 December 1970) 1.

93 SH, Büro Stadtbaurat Hillebrecht, inv.no. 296, ‘Beft.: Schatten des Bedenkens über Raschplatz-Projekt’ (2 November 1970); ‘Betr.: Architektenkammer Niedersachsen, Hannover’ (8 December 1970) 1.

94 Jonker, “Nicht nur Geschäfte,” 1596–7.

95 SH, Büro Stadtbaurat Hillebrecht, inv.no. 296, ‘Betr.: Raschplatz-Projekt der Stadt Hannover’ (23 November 1970) 2.

96 Verlaan, “Stadsvernieuwing,” 163–83.

97 SH, Büro Stadtbaurat Hillebrecht, inv.no. 296, ‘Entwurf’ (29 March 1971) 1.

98 S.N., “Stadtverwaltung”.

99 SH, Büro Stadtbaurat Hillebrecht, inv.no. 296, ‘Bredero’ (2 November 1970) 3.

100 Buiter, “Naar een Internationaal Bouwconcern,” 91.

101 Cf. Ward, “Re-Examining the International Diffusion of Planning,” 42–3.

Bibliography

- Banham, Reyner. Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past. London: Thames and Hudson, 1976.

- Baudet, Floribert H. Utrecht in Bedrijf: De Economische Ontwikkeling van Stad en Regio en de Kamer van Koophandel 1852-2002. Utrecht: Matrijs, 2002.

- Becker, Frans and Menno Hurenkamp. “Op Zoek naar een Nieuw Wethouderssocialisme.” Socialisme en Democratie 67, no. 1/2 (2010): 69–77.

- Beijer, J., J. Boerrigter, M. Gubbels, L. Jacobs, P. Keur, J. Meijer and G. Nibbering, eds. Familie, Gebouwen, Historie: 120 Jaar FGH Bank. Utrecht: FGH Bank, 2012.

- Berman, Marshall. All That is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity. New York: Verso, 2010.

- Blekendaal, Martijn. “Dertig Jaar na de Opening van Hoog Catharijne.” Historisch Nieuwsblad 12, no. 7 (2003): 20–23.

- Blijstra, Rien. 2000. jaar Utrecht: Stedebouwkundige Ontwikkeling van Castrum tot Centrum. Utrecht: A.W. Bruna & Zoon, 1969.

- Bolle, G., and C. A. Snepvangers, eds. Spiegel van Onroerend goed: Verhandeling over een Aantal Onderwerpen het Onroerend Goed Betreffende. Deventer: Kluwer, 1977.

- van der Boor, Willem S. Stedebouw in Samenwerking: Een Onderzoek naar de Grondslagen voor Publiek-Private Samenwerking in de Stedebouw. Alphen aan den Rijn: Samson H.D. Tjeenk Willink, 1991.

- Bornewasser, Johan A. Katholieke Volkspartij 1945-1980. Band II: Heroriëntatie en Integratie 1963-1980. Nijmegen: Valkholf Pers, 2000.

- Bredero, Vast Goed N. V. Overzicht van Projekten. Utrecht: Verenigde Bedrijven Bredero, 1963.

- Brouwer, H. J. W. “Belegging in Onroerend Goed in de Twintigste Eeuw.” In Spiegel van Onroerend goed: Verhandeling over een Aantal Onderwerpen het Onroerend Goed Betreffende, edited by G. Bolle and C. A. Snepvangers, 105–126. Deventer: Kluwer, 1977.

- Buiter, Hans. “‘De Stad met de Mooiste Maquettes’: Plannen voor Utrechts Centrum en Binnenstad 1954-1991.” Jaarboek Oud-Utrecht 23 (1992): 6–44.

- Buiter, Hans. Hoog Catharijne: De Wording van het Winkelhart van Nederland. Utrecht: Matrijs, 1993.

- Buiter, Hans. “Naar een International Bouwconcern, 1947–1986.” In Bredero’s Bouwbedrijf: Familiebedrijf, Mondiaal Bouwconcern, Ontvlechting, edited by Willem M. J. Bekkers, A. P. W. Esmeijer, D. W. Aertsen, and K. Oskam, 59–108. Amsterdam: Dutch University Press, 2005.

- Bullock, Nicholas. Building the Post-War World: Modern Architecture and Reconstruction in Britain. London: Routledge, 2002.

- Commissie Opvoering Productiviteit van de Sociaal-Economische Raad. Moderne Winkelcentra. The Hague: Staatsdrukkerij, 1962.

- Conekin, Becky, Frank Mort, and Chris Waters, eds. Moments of Modernity: Reconstructing Britain 1945-1964. London: Rivers Oram Press, 1999.

- Daniels, Peter W. Office Location: An Urban and Regional Study. London: Bell, 1975.

- Dendermonde, Max. Een Steen is een Steen is een Stad: De Geschiedenis van Bredero. Nijmegen: Koninklijke Drukkerij Thieme, 1975.

- Düwel, Jörn and Niels Gutschow. Städtebau in Deutschland im. 20 Jahrhundert: Ideen – Projekte – Akteure. Stuttgart: Teubner, 2001.

- Fainstein, Susan S. The City Builders: Property Development in New York and London 1980-2000. Oxford: Blackwell, 1994.

- Feuchtinger, Max E. Verkeersplan Utrecht. Ulm: S.N., 1958.

- Fischer, Frank. Technocracy and the Politics of Expertise. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1990.

- de Galan, Cees. “Om de Kwaliteit van het Bestaan.” In Wetenschappelijk Socialisme: Over de ‘Plannen’ van SDAP en PvdA, edited by Bram Peper, and Joop van den Berg, 61–68. Amsterdam: Bert Bakker, 1982.

- Giddens, Anthony. The Class Structure of Advanced Societies. New York: Barnes and Noble, 1973.

- Gold, John R. The Practice of Modernism: Modern Architects and Urban Transformations 1954-1972. London: Routledge, 2007.

- Gool, Peter van, Robert M. Weisz, and Paulus G.M. van Wetten, eds. Onroerend Goed als Belegging. Culemborg: Stenfert Kroese, 1993.

- Gruen, Victor. The Heart of Our Cities: The Urban Crisis, Diagnosis and Cure. London: Thames and Hudson, 1965.

- Hall, Thomas. Stockholm: The Making of a Metropolis. London: Routledge, 2009.

- Harding, Alan. “Elite Theory and Growth Machines.” In Theories of Urban Politics, edited by D. Judge, G. Stoker and H. Wolman, 35–53. London: SAGE Publications, 1995.

- Hardwick, M. Jeffrey. Mall Maker: Victor Gruen, Architect of an American Dream. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004.

- Harris, Andrew and Susan Moore. “Planning Histories and Practices of Circulating Urban Knowledge.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37, no. 5 (2013): 1499–1509.

- ter Hart, Hendrik Willem. Commercieel Vastgoed in Nederland: Een Terreinverkenning. Vlaardingen: Nederlands Studie Centrum, 1987.

- Harvey, David. “From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism: The Transformation of Urban Governance in Late Capitalism.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 71, no. 1 (1989): 3–17.

- Harvey, David. The Urbanization of Capital. Oxford: Blackwell, 1985.

- Jonas, Andrew E. G. and David Wilson. “The City as a Growth Machine: Critical Reflections Two Decades Later.” In The Urban Growth Machine, edited by Ibidem, 3–18. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Jonker, Gert. “Nicht nur Geschäfte – auch ein Musikzentrum für Utrecht.” Bauwelt 61, no. 42 (1970): 1596–1597.

- Kersloot, Jan M. Vijfenzestig Jaar Bouwen aan Wonen, Winkelen en Werken: Projectontwikkeling en Bouw van Woningen, Kantoren en Winkels 1930-1995. Delft: Delft University Press, 1995.

- Klemek, Christopher. The Transatlantic Collapse of Urban Renewal: Postwar Urbanism from New York to Berlin. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2011.

- de Klerk, Len. De Modernisering van de Stad: De Opkomst van de Planmatige Stadsonwikkeling in Nederland. Rotterdam: NAi Uitgevers, 2008.

- Korsten, Arnold, and Peter Tops. “Het College van Burgemeester en Wethouders.” In Lokaal Bestuur in Nederland: Inleiding in de Gemeentekunde, edited by ibidem, 183–196. Alphen aan den Rijn: Samson, 1998.

- Kramper, Peter. Neue Heimat: Unternehmenspolitik und Unternehmensentwicklung im gewerkschaftlichen Wohnungs- und Städtebau 1950-1982. Stuttgart: Steiner Franz Verlag, 2008.

- Kuiper, Johan A. Eerste Rapport over de Grondslagen voor een Structuurplan voor de Bebouwde Omgeving en een Tracé voor een Ringweg. Rotterdam: S.N., 1962.

- Leijte, Hans. “Scheuren in het Voetstuk van Jan Beton.” Het Parool, 10 November 1984.

- de Liagre Böhl, Herman. Amsterdam op de Helling: De Strijd om Stadsvernieuwing. Amsterdam: Boom, 2010.

- de Liagre Böhl, Herman. Steden in de Steigers: Stadsvernieuwing in Nederland 1970-1990. Amsterdam: Bert Bakker, 2012.

- Logan, John, and Harvey Molotch. Urban Fortunes: The Political Economy of Place. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

- Logemann, Jan L. Trams or Tailfins: Public and Private Prosperity in Postwar West Germany and the United States. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2012.

- Luyckx, Albert W. Het Winkelcentrum. Amsterdam: Stichting IVIO, 1962.

- Marriott, Oliver. The Property Boom. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1967.

- Meurs, Paul. De Moderne Historische Stad: Ontwerpen Voor Vernieuwing en Behoud 1813-1940. Rotterdam: NAi Uitgevers, 2000.

- Ministerie van Volkshuisvesting en Bouwnijverheid. Rapport van de Commissie Grondkosten. The Hague: Staatsdrukkerij, 1962.

- Molotch, Harvey. “The City as a Growth Machine: Toward a Political Economy of Place.” American Journal of Sociology 82, no. 2 (1976): 309–332.

- N.V. Maatschappij voor Projectontwikkeling EMPEO. About Hoog Catharijne. Utrecht: EMPEO, 1973.

- N.V. Maatschappij voor Projektontwikkeling EMPEO. Plan Hoog Catharijne: Bijdrage tot Utrechts Centrumfunctie. Utrecht: EMPEO, 1962.

- N.V. Maatschappij voor Projektontwikkeling EMPEO. Voetgangersonderzoek Hoog Catharijne. Utrecht: EMPEO, 1967.

- N.V. Maatschappij voor Projectontwikkeling EMPEO. Winkelfunktie Utrechtse binnenstad. Utrecht: EMPEO, 1965.

- Nederlands Instituut voor Ruimtelijke Ordening en Volkshuisvesting. Handleiding Voorbereiding Structuur- en Bestemmingsplannen. Alphen aan den Rijn: Samson, 1965.

- Nelisse, Paul C. J. Stedelijke Erfpacht. Doetinchem: Reed Business, 2008.

- Nieuwenhuijsen, Pieter. “Het Onderschatte Project van de PvdA: Veertig Jaar Gemeentepolitiek.” In Het Negende Jaarboek voor het Democratisch Socialisme, edited by Redactie Jaarboek, 59–105. Amsterdam: Wiardi Beckman Stichting, 1988.

- Oude Veldhuis, Christine M., Dirk A. Rompelman, and Jan Fokkema, eds. Neprom 1974-2000: Werken aan Ruimtelijke Ontwikkeling. Voorburg: Neprom, 2000.

- Partij van de Arbeid Federatie Amsterdam. Mens en Stad: Amsterdam Vandaag en Morgen. Amsterdam: De Arbeiderspers, 1953.

- Petri, Jan. “Hoog Catharijne.” Stedebouw en Volkshuisvesting 45, no. 5 (1964): 135–157.

- Pierre, Jon. “Comparative Urban Governance: Uncovering Complex Causalities.” Urban Affairs Review 40, no. 4 (2005): 446–462. doi: 10.1177/1078087404273442

- Ploeger, Ralph A. Regulating Urban Office Provision: A Study of the Ebb and Flow of Regimes of Urbanisation in Amsterdam and Frankfurt am Main 1945-2000. Amsterdam: Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2004.

- Provoost, Michelle. Asfalt: Automobiliteit in de Rotterdamse Stedebouw. Rotterdam: Uitgeverij 010, 1996.

- Pugh, Cedric. “Olympia and York, Canary Wharf and What May be Learned.” Property Management 14, no. 2 (1996): 5–18.

- Rijksdienst voor het Nationale Plan (hereafter: RNP). Jaarverslag 1963. The Hague: Staatsdrukkerij, 1964.

- Rijksplanologische Dienst (hereafter: RPD). Jaarverslag 1969. The Hague: Staatsdrukkerij, 1970.

- Romijn. Hier is Utrecht. Utrecht: Bruna, 1958.

- Rompelman, Dirk. “1968/1969-2009; Een Terugblik.” Vastgoedmarkt 36, no. 4 (2009): 69.

- Ryckewaert, Michael. Building the Economic Backbone of the Belgian Welfare State: Infrastructure, Planning and Architecture 1945-1973. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2011.

- Saunders, Peter. Urban Politics: A Sociological Perspective. London: Hutchinson, 1979.

- Schuiling, Dick. De Inrichting van het Gemeentelijk Stedebouwkundig Apparaat, Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit, 1972.

- Schuyt, Kees and Ed Taverne. 1950: Welvaart in Zwart-Wit. The Hague: SDU, 2000.

- Shapely, Peter. “The Entrepreneurial City: The Role of Local Government and City-Centre Redevelopment in Post-War Industrial English Cities.” Twentieth Century British History 22, no. 4 (2011): 498–520.

- Shapely, Peter. “Governance in the Post-War City: Historical Reflections on Public-Private Partnerships in the UK.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37, no. 4 (2013): 1288–1304.

- S.N. 1973. “Bredero Biedt Huizenplan voor Utrechtse Binnenstad aan.” Utrechts Nieuwsblad, September 22.

- S.N. “Eigenlijk is Bredero Uitvinder van het Woord Projectontwikkeling.” Cobouw Magazine 6, no. 18 (1978): 42–49.

- S.N. 1970. “Stadtverwaltung bestochen? “Das ist ja Wahnsinn!”.” Hannoversche Rundschau, November 5.

- Spruit, Goof and Adam Feddes. “Enkele Aspecten van de Vormgeving van het Plan “Hoog-Catharijne.” Weg en Werken 11, no. 2 (1965): 48–51.

- Stichting voor Economisch Onderzoek der Universiteit van Amsterdam. Het Stedelijke Centrum en Zijn Functies. Leiden: Stenfert Kroese, 1961.

- Verlaan, Tim. “De in Beton Gegoten Onwrikbaarheid van Hoog Catharijne: Burgers, Bestuurders en een Projectontwikkelaar in Utrecht 1962-1973.” Stadsgeschiedenis 7, no. 2 (2012): 183–205.

- Verlaan, Tim. “Dreading the Future: Ambivalence and Doubt in the Dutch Urban Renewal Order.” Contemporary European History 24, no. 4 (2015): 537–553.

- Verlaan, Tim. “Stadsvernieuwing, Ideologie en Buitenparlementaire Actie: Mobilisering van Onbehagen in de Strijd tegen Hoog Catharijne 1970-1973.” In Onbehagen in de Polder: Nederland in Conflict sinds 1795, edited by P. van Dam, B. Mellink and J. Turpijn, 163–183. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2014.

- Vleugels, Marcel. 85 Jaar ABP. Heerlen: ABP, 2007.

- Vos de Wael, N. X. M. M. De Ranitz als Burgemeester 1948-1970: Portret van een Periode. Utrecht: Westers, 1986.

- de Vries, Jan. “Economische Ontwikkelingen in de Periode 1949-1973.” In Vertrouwde Patronen, Nieuwe Dromen: Nederland naar een Modern-Industriële Samenleving 1948-1973, edited by Hélène Vossen, Marjan Schwegman and Peter Wester, 9–14. IJsselstein: Vereniging van Docenten Geschiedenis en Staatsinrichting in Nederland, 1992.

- de Vries, Jan. “Het Dienen van de Gemeenschap in het Doen van Zaken.” Weg en Werken 11, no. 2 (1965): 34–35.

- De Vries, Jan. “Misverstanden over de projectontwikkelaar.” Plan 5, no. 5 (1974): 3–9.

- Wagenaar, Cor. Town Planning in the Netherlands since 1800: Responses to Enlightenment Ideas and Geopolitical Realities. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2011.

- Wakeman, Rosemary. Modernizing the Provincial City: Toulouse 1945-1975. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Wakeman, Rosemary. “Rethinking Postwar Planning History.” Planning Perspectives 29, no. 2 (2014): 153–163.

- Ward, Stephen V. Planning the Twentieth-Century City: The Advanced Capitalist World. Chichester: Wiley, 2002.

- Ward, Stephen V. “Re-Examining the International Diffusion of Planning.” In Urban Planning in a Changing World: The Twentieth Century Experience, edited by Robert Freestone, 39–60. London: E & FN Spon, 2000.

- Werkcommissie Westen des Lands. De Ontwikkeling van het Westen des Lands. The Hague: Staatsdrukkerij, 1958.

- de Widt, D. J. Aspecten van de Stedebouwkundige Dynamiek van Utrecht: Verslag van een Onderzoek met Betrekking tot het Centrum van de Stad Utrecht. Delft: Instituut voor Stedebouwkundig Onderzoek, 1966.

- Wiekart, Karel. “Het Plan-Dingemans en Hoog-Catharijne: Een Synthese Lijkt Mogelijk.” Kunst in Utrecht 1, no. 5 (1962): 73–75.

- Wiekart, Karel. “Opinies over Hoog Catharijne.” Kunst in Utrecht 2, no. 4 (1962): 63–65.