ABSTRACT

In 1945/1946, the Colonial Administration in Uganda commissioned Ernst May – planner of Das Neue Frankfurt (1926–1930) – to design the Kampala Extension Scheme and the smaller Wandegeya Development Scheme. The past decade has seen increasing scholarly interest in the neglected ‘African’ episode of Mays planning oeuvre, but this literature has not explicitly examined how May’s planning articulated with the fraught political realities of late-colonial rule. Utilizing previously undocumented archive material and a theoretical frame informed by governmentality studies, this paper examines these articulations, particularly those relating to tensions and contradictions in Colonial government arising from the would-be turning-point from indirect rule to a bio-political rationality of development and welfare. It is shown that while May’s submitted plans spoke directly to the tropes of urban improvement, African detribalization and labour stabilization, which informed the ‘turning point’ in colonial policy, May’s elaborate socio-spatial interventions and the style in which these enunciated racial difference proved unpalatable to a colonial administration stifled by the rationality of the economic domain of government, by constraints on how difference could be enunciated and by African urban politics.

Introduction. ‘Meet Ernst May, the man who built Kampala City’Footnote1

Ernst May (1886–1970) was an influential member of the architectural association Der Ring and adherent of the modernist Neue Bauen which emerged during the Weimar Republic. He is most renowned for the satellite settlements (Siedlungen) constructed in Frankfurt-am-Main in 1926–1930; lauded by Lewis Mumford as ‘probably the best’ example of ‘modern methods of planning and building communities’.Footnote2 Commissioned to alleviate the post-First World War housing shortage, these settlements were pioneering for their rationalized and industrialized construction methods, infrastructural standards, modernist aesthetic and scale and, it has been argued, represented not only the new physical landscape of Das Neue Frankfurt but also socio-technical milieu for fostering the new civic subject.Footnote3 The rise of National Socialism in Germany coupled with an invitation to apply his garden city inflected Neue Bauen style to the new industrial centres of Das Neue Russland saw May move to Moscow in 1930. However, the changing political climate and direction of Soviet building policy soon caused him to fall from favour and, unable to return home, he moved to East Africa in December 1933.Footnote4 After establishing a coffee estate near Arusha May relocated to Nairobi where, eager to remount his ‘town-planning horse and ride into battle’, he resumed his career as architect-planner.Footnote5 His chance for action arrived in 1945/1946 when the Colonial Administration in Uganda awarded him two town-planning commissions; the Kampala Extension Scheme and the Wandegeya Development Scheme, both of which were to include African housing areas.

While May’s planning oeuvre in Germany has attracted considerable study the same cannot be said for his East African work. Initial work to readdress this lacuna focused on cataloguing May’s plans and buildings.Footnote6 However, echoing research on other peripatetic architect-planners working in late-colonial and early post-colonial contexts, subsequent scholarship has integrated a more critical post-colonial research agenda which, originating in the late 1980s with a number of now classic studies on colonial North Africa, has sought to explicate ‘the ways in which power, knowledge and forms circulated’ between the West and colonial territories.Footnote7 Studies of the diffusion of Western urban design (garden city, modernist, etc.) – often in hybrid or ‘tropical’ forms – now span a considerable spectrum of historical periods, colonial contexts and routes of ‘nomadic expert(ise)s’.Footnote8

This field has since developed to even more critically examine the whereabouts of agency in the authorship of planning/architecture in transcultural contexts. This includes how the cultural displacement and positionality of ‘global experts’ such as May articulated with what Avermaete terms ‘the obstinate features of specific locales and particular [multi-scaled] dynamics’, such as colonial bureaucratic cultures, the circulation of norms/forms among developmental agents, and interventions by ‘third-party interests’.Footnote9 The need to examine such articulations is well stated in the literature, not least for the case of travelling modernism. Çelik, for example, argues that modernism in colonial Algiers has tended to be analysed as ‘a parable of European modernism’, while Göckede avers that May’s Kampala plans have been uncritically located within an ‘idealistic paradigm of architectural modernism as an emancipatory success story’ leaving socio-political context ‘without comment’.Footnote10

This paper, which has a more general ambition to further elaborate May’s African planning oeuvre, particularly his erstwhile undocumented Wandegeya Development Scheme, more specifically seeks to engage Göckede’s call for the ‘re-contextualization of May’s East African projects’.Footnote11 While research has begun to consider how May’s ‘theoretical program’ altered in the colonial context – e.g. due to climatic considerations and his view that Africans lacked ‘previous training in citizenship’ – evaluations of his Kampala plans remain compromised by silence on how these plans articulated with the ‘political realities of colonial rule’.Footnote12 This omission is understandable given the challenges of researching the Uganda National Archives, but recent cataloguing work has improved accessibility and erstwhile undocumented correspondence is utilized here to explore three specific issues in respective sections of this paper.Footnote13 Firstly, consideration of the politically contested planning terrain, particularly at Wandegeya, leading up to and during May’s commissions. Secondly, how May’s plans articulated not only with this terrain but also with the complex implications of the contemporaneous ‘turning point’ in British colonial policy from Indirect Rule towards Development and Welfare.Footnote14 Thirdly, examination of why May’s plans were so critically received and ultimately largely rejected by the colonial administration. Indeed, May was not to be ‘the man who built Kampala City’.

Methodological and conceptual framework

Drawing methodological inspiration from Deleuze, it is posited that illuminating the points upon which May’s plans were seen to ‘clash with power, argue with it and exchange brief and strident words’ can disclose wider tensions arising from the colonial stratagem of brokering new limits for the sayable and the doable vis-à-vis re-planning cities for African ‘inclusion’ at the turning point in British colonial policy.Footnote15 To frame this turning point and May’s recruitment as expert, Foucault’s notion of a governmental problematization of ‘some hitherto unproblematic relations’ is of heuristic utility.Footnote16 Specifically, a problematization where, from the 1930s, multi-scalar impulses increasingly rendered the activity of government under indirect rule and the regime of practices assembled to do such governing problematic. ‘Regimes of practices’ denote context-specific ‘programs of conduct’ of government operationalized through assemblages of mechanisms and calculations of power – discourses, institutions, buildings, laws, philosophical propositions – to conduct the conduct of individuals/populations towards specific governmental ends, e.g. to educate, relieve poverty, make productive.Footnote17 Following Dean, three precepts of any regime of practices transpire as pertinent for analysing tensions between May and the colonial administration as well as those within and between the Colonial and Buganda Governments; (1) the forms of governmental ‘visibility’ and the technical means deemed necessary for the operation of specific regimes of practices; (2) the forms of knowledge defining the regimes of practices; (3) the subjectivities sought by different practices of government.Footnote18 To clarify, Foucault interrogated such precepts in response to questions such as ‘What were working-class housing estates, as they existed in the nineteenth century?’ to excavate historically situated rationalities of government.Footnote19

The regime of practices assembled for indirect rule was structured around the bifurcated state comprising colonial and ‘native’ administrations; a form of government that Mamdani terms decentralized despotism.Footnote20 Colonial knowledge of African ‘life’ posited alterity and the incapacity for autonomous self-directed conduct which legitimized withholding ‘liberal freedoms’ to act in specific societal domains (e.g. the market).Footnote21 Africans were instead to be ‘protected’ within ‘tribal’ regulating mechanisms. Where relations beyond the tribe were needed – e.g. as labour – juridical, economic, and infrastructural mechanisms (e.g. Masters and Servants Ordinances, bachelor housing, etc.) were introduced to curb so-called detribalization.Footnote22 Even Africans living in urban areas in Uganda were administered by the county and sub-county Native Authority and Courts located outside of towns.Footnote23 However, impulses leading up to the Second World War (cf. the 1940 Colonial Development and Welfare Act) and at war’s end caused this regime of practices and the forms of African life and associated racial-spatial fix to become politically and economically untenable.Footnote24 This problematization stimulated intense debate on how the existing regime of practices and socio-spatial assemblage of ‘men and things’ could be re-assembled to facilitate new strategic aims; retaining and restructuring colonial economies, quelling anti-colonial sentiment in the West, resistance in the South, and achieving ‘development and welfare’.Footnote25

But, if the authoritarian ‘rod’ of despotism was to be lowered, ‘how then’, to paraphrase John Locke in his treatise on education, ‘shall [the African] be governed’, what alternative ‘instruments of government’ should/could be devised to ‘govern his action, and direct his conduct’?Footnote26 Was it to be through the extension of liberal freedoms and ‘the promotion of market regimes in the government of domains previously regulated in other ways’?Footnote27 Tropes through which solutions to this problematization were deliberated by colonial administrations, planning experts and scholars alike, particularly for urban contexts, were detribalization, labour stabilization (contra migrant labour) and ‘government through community’.Footnote28 Erstwhile an ‘evil’ to be blocked, detribalization now transpired as a governmentally useful bio-political process that rendered life technical by positing it mutable through technological conditioning. Scott and Simone usefully define such a process as ‘disabling old forms of life’, ‘breaking down specific symbolic meanings of space’ and, crucially in terms of urban planning and government through community, ‘constructing in their place new conditions so as to enable new [productive] forms of life to come into being’.Footnote29 This emergent rationality of government was bio-political because, in contrast to the relative invisibility of the African quotidian under indirect rule, it posited including the details of African life into the calculations of power.Footnote30 It was developmental and welfarist by reconceiving African incapacities not as given, but a consequence of debilitating external factors, thus positing African life and milieu as objects of knowledge and targets for improvement. The amelioration of debilitating factors became central to how development was framed. Worthington’s inaugural Development Plan for Uganda (1946) and Orde-Browne’s Labour Conditions in East Africa (1946), both equated development with optimizing the productive potential of human and natural resources and emphasised that achieving development required breaking the ‘vicious circle of poverty’ (a lack of education – poor feeding – poor health – poor housing – inefficient work – low productivity). However, Worthington added the crucial rider that ‘In Uganda, as elsewhere, there is difference of opinion as to which is the weakest link.’Footnote31 Adding further uncertainty for experts such as May recruited to propose solutions for specific domains, was vacillation over the desired subjectivities of ‘new’ African life, Orde-Browne stating that ‘No British African government has yet announced any decision on the respective merits of a stabilized or a migrant labour force.’Footnote32 This left unresolved the possible or practicable forms of ‘visibility’ and corollary technical infrastructure for ‘new [African housing] conditions’, not least in terms of continued scepticism to introducing ‘family’ wages, sub-economic rents and concerns that government provided housing would dissuade private enterprise from entering the field.Footnote33 Would, for example, African urban housing solutions centred on ‘government through community’ then being elaborated by Gardner-Medwin in the West Indies, Fry and Drew in West Africa and Thornton-White in Nairobi be politically and/or economically viable?Footnote34 Vacillation over these issues would be mirrored in the disparate development strategies of Governor Hall (1945–1952), under whose governorship May’s plans would be conceived and appraised, and Governor Cohen (1952–1957), respectively. Hall prioritised rapid state-lead industrialization as ‘the only answer’ to improved African social well-being and productivity, while Cohen would subsequently invert Hall’s dictum of ‘restrict[ing] the expansion of social services’ to Africans and downplay industrialization.Footnote35

These considerations set the context for the three sections of this paper. Before elaborating upon May’s plans for the Wandegeya Development Scheme (section two) and upon how these plans were thence appraised by the colonial authorities (section three), the first section focuses on the colonial project, from the mid-1930s, of incorporating tracts of Baganda owned land at Wandegeya within Kampala Township. Understood as a strategy to break down specific symbolic meanings of space and optimize relations between people and urban land to facilitate urban development, the Wandegeya case introduces the contested terrain upon which May was commissioned to plan and highlights the tensions between and within the two arms of the bifurcated state vis-à-vis brokering a new regime of practices at the ‘turning point’.

‘Breaking down specific symbolic meanings of space’: the contested ground of Wandegeya

Permanent settlement was first established in Kampala in 1884/1885 when Kabaka Mwanga II – king of Buganda – established his capital (Kibuga) on Mengo Hill.Footnote36 Feted for their political and military sophistication and influence, the Baganda attracted missions and the Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC) to occupy neighbouring hills including today’s CBD at Nakesero, and were soon inveigled into the formative colonial assemblage as agents of ‘Bugandan sub-imperialism’.Footnote37 The Buganda Agreement of 1900, included Article 15 which granted tracts of allodial land (mailo land) to the Kabaka, country chiefs (bakungu), and some thousand landowners, thereby laying the foundations for a dual administrative structure and Kampala’s development as a dual city comprising crown land and African owned mailo land.Footnote38 Kampala’s growth in size and population (reaching 24,100 in 1948) increasingly rendered central tracts of mailo land, especially Wandegeya, a dilemma with the advent of colonial aspirations for modern orderly urban planning.Footnote39

As is evident in the 1919 Kampala planning scheme – a textbook example of sanitary segregation based on recommendations by W.J. Simpson of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine – no provision of African housing areas existed within townships before 1930.Footnote40 Furthermore, Township Rule 101 prohibited, albeit not without significant leakage, unauthorized construction of ‘huts’ within townships.Footnote41 The subsequent 1930 Kampala scheme by the colonial surveyor and planner A.E. Mirams, drafted after the interdict on de jure segregation of Europeans and Asians in East Africa, utilised zoning and green belts – later lauded by Ernst May for their ‘far-sightedness’ – to achieve de facto racial segregation.Footnote42 Mirams did, however, contemplate the need for African housing, including proposals for a ‘garden township’ for African railway employees and plans to make the existing labour camp ‘more like a respectable village’, albeit adding ‘It may be desirable to wire it all in, but the prison aspect is not desirable.’Footnote43 As the oxymoronic notion of barb-wired respectability suggests, Mirams’ plan evidenced a disjuncture between the sayable and the doable concerning racial segregation and re-planning urban areas for African inclusion. This disjuncture, captured by Mirams’ ambivalence regarding ‘how to house … this somewhat unusual class of person’ sharing interests ‘quite their own’, would characterise the debate concerning how to incorporate mailo land and Africans into Kampala Township leading up to and during May’s commissions.Footnote44 Mirams did, however, hint at a solution to the paradox of doing racially segregated planning while simultaneously saying there is ‘no question of segregation or anything of the sort’. The solution, evident in other contemporaneous British colonial contexts, involved substituting culture and/or class for race and by planning for discrete ‘communities of interest’.Footnote45

In the year Mirams’ plan was published, the Colonial Administration initiated the project of incorporating the ‘Wandegeya salient’ within Kampala Township, principally to facilitate the enforcement of building and public health regulations.Footnote46 Situated just one kilometre north-west of Kampala’s CBD and adjoining Makerere University () but within the sub-county of the Kibuga, Wandegeya was both ripe for incorporation but also a place that resisted. Like ‘the cauldron of conflicting ideas and political allegiances’ that characterized the Weimar Republic during May’s planning work in Frankfurt, Wandegeya constituted, throughout the 1930s–1940s, a zone of conflicting political allegiances and urban imaginaries within and between the Colonial and Buganda administrations, and among ‘Asian’ trading interests and Wandegeya residents.Footnote47

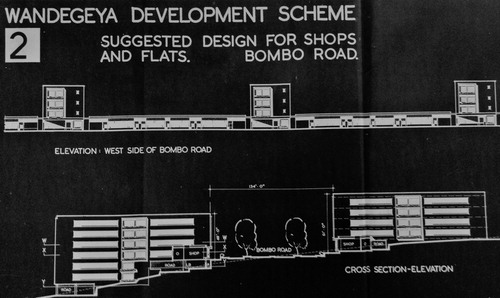

Figure 1. W = Wandegeya. Kololo, Naguru and Nakawa, the focus of May’s Kampala Extension Plan (1947) at top centre and top right. Kampala Township boundary in red. Land acquired from mailo and added to Township between 1938 and 1948 marked in blue (UNA.71/C464) (colour online only).

To some, the existing ‘disposition and arrangement of men and things’ at Wandegeya constituted a problematization, particularly in terms of existing relations between various segments of the population and land being deemed antithetical to urban ‘improvement’ through orderly planning and a freer play of market forces.Footnote48 Wandegeya’s ‘tangle’ of ‘plots of all shapes and sizes’ – clashed with the colonial project of wishing to make Kampala ‘look like a town’.Footnote49 But until Wandegeya was incorporated within Kampala Township it remained largely inaccessible to government interventions including levying rates and controlling building standards and land utilization. This situation supposedly permitted ‘private [mailo] landowners to continue to create, for profit, insanitary urban conditions on their land’.Footnote50 Furthermore, the existing colonial policy of ‘protective’ African segregation; i.e. (cl)aiming to protect Africans from market forces and displacement, prohibited non-Africans from trading or buying or leasing land at Wandegeya. This caused ‘Asian’ traders – 66 having had applications to lease land in the area denied in 1944 – to complain that the policy gave Africans unfair trading advantage.Footnote51 Now, however, continued segregation was seen by some colonial officialdom as a barrier to ‘upgrading’ Wandegeya and of the need to out-source development at Wandegeya by allowing the entrance of non-Africans.

However, changing this policy to facilitate increased private capital investment at Wandegeya – a process Brennan terms ‘gentrification’ for the contemporaneous case of Dar es Salaam – was highly contentious.Footnote52 The Buganda Regents and Lukiiko (Buganda Parliament) consistently opposed revoking the ban against non-African land and trading rights in the Kibuga throughout the 1930s and 1940s, despite the potential economic benefits to be gained from leasing land to non-Africans.Footnote53 Some colonial officials also supported continued segregation, not least successive incumbents of the office of Buganda Resident; an office introduced by Governor Mitchell to replace that of Provincial Commissioner in his wider reform of Colonial – Buganda relations. Buganda Resident A.H. Cox (1939–1944), for example, wished to ‘save the Muganda’s land for the Muganda’ and ‘to do nothing to encourage Indian immigration and amenities in this country’.Footnote54 Indeed, the planning impasse at Wandegeya foregrounded the ambiguity with which ‘the Asian’ was perceived and discursively constructed, leading to diverging views on their optimal (spatial) arrangement in a wider constellation of ‘men and things’ to facilitate development. To some, ‘the Asian’ constituted an agent of urban disorder; the Assistant Chief Secretary, for example, stating in 1948 that ‘if non-natives are allowed in, they will squeeze out the African traders and Wandegeya will become another “Bombay bazaar”’.Footnote55 To others, however, particularly at the Land Office, the Asian was indispensable if ‘worthwhile-buildings’ were to be erected.Footnote56 As is discussed in section two, ambiguity on this issue would result in confusion regarding the intended target population in Ernst May’s Wandegeya commission.

But if the issue of segregation contra ‘gentrification’ was contentious, the strategy of compensated displacement of the African population at Wandegeya was even more so. This strategy had effectively been effected at Jinja in neighbouring Busoga in the 1940s to facilitate construction of the Walukuba African housing estates, but there mailo had not been an issue.Footnote57 As Morris, has argued, while the legal status of the Buganda Agreement, which had conferred mailo land rights, was in fact highly questionable, Governor Mitchell concluded that it was regarded by ‘the Kabaka, his Ministers and chiefs and by all educated Baganda as having almost scriptural authority and inviolability’.Footnote58 Furthermore, while the Buganda administration had previously ceded mailo land to the administration, it now opposed ‘further nibbling of land from the Kibuga area’ (see ‘land acquired from mailo’ in ).Footnote59 Accordingly, compensated appropriation of Wandegeya was ruled out.

While early interventions to incorporate Wandegeya had, according to the Director of Surveys, been ‘ad hoc’, a transition is evident from 1936 to a more bio-political rationality of government.Footnote60 A timeout was invoked to stock-take and collect knowledge in various governmental domains in order to be able to assemble a revised regime of practices. In April 1936, the Administration called for a reconsideration of ‘the major question of the policy to be adopted by Government in connection with the housing of Africans in and around Townships’, and the Wandegeya question was put on hold to permit ‘fuller consideration of the problem of incorporating mailo land within the township’.Footnote61 Importantly, the motivation for the ensuing year-long hiatus on urban interventions including evictions was an ‘urgent need for a Town Planning Ordinance in order to secure the necessary power to enforce such proposals as are adopted, both in Kampala and elsewhere’.Footnote62 No planning ordinance was passed until 1948, but attention had become trained on the problem of how to better formulate and implement top-down developmental urban policy. Particularly evident was a will, evident in the profusion of commissions and inspections of African urban spaces throughout Empire in the 1930s, to better visualize the African quotidian and formulate African housing solutions to optimize African life.Footnote63 In Uganda, the Steil Report (1938) was commissioned to examine the ‘Housing and Sanitary Conditions in and around Kampala’ and, based on the ‘deplorable nature of affairs’, emphasized ‘the necessity for rehousing African labouring classes in model villages’, not least at Wandegeya, and, further, that Government should plan and finance African trading areas in townships including on privately held land.Footnote64 Governor Mitchell’s irritated response underlined, once again, a disjuncture between the sayable and doable. On the one hand, he dismissed the idea of setting aside land for African residence and trading on the grounds that functional zoning could not be based on racial grounds but only ‘on two conditions – type of building and use to which it is to be put’.Footnote65 On the other hand, he reiterated his directive from 1936 calling for the establishment of an ‘African village east of the town’.Footnote66

The Wandegeya planning impasse was partly resolved in 1938 when ‘delicate negotiations’ between the Provincial Commissioner and Native Government resulted in the latter agreeing ‘to the principle of town planning and the inclusion of this area [Wandegeya] together with Makerere and Mulago within the township boundaries, but consider that the land should remain in the ownership of the present individuals’.Footnote67 However, the latter proviso together with a clause precluding property rates being levied at Wandegeya, rendered this a hollow victory for the Colonial Administration as it blocked comprehensive re-planning.Footnote68 New solutions were tabled including; A) leaving things as they were but enforcing Township building rules and sanitary regulations, B) enacting a Town Planning Ordinance, planning the place and compensating where necessary, and C) Steil’s proposal to form a company to take over Wandegeya and giving African owners proportionate shares.Footnote69 Governor Mitchell dismissed C) outright and deemed B) only a future option, and instead proposed combining option A) with a strategy to draw trade and development away from Wandegeya’s most ‘tangled’ central area and developing instead land acquired at neighbouring Mulago together with larger contiguous mailo plots at Wandegeya in the possession of owners willing to have their land planned.Footnote70 That this was considered a viable option intimates Mitchell’s seeming disregard for the deepening political rifts both within the Buganda polity and against Colonial rule. Within the Buganda polity itself, the land issue was the most important cause of discord, particularly concerning conflicting rationalities involving what Thompson frames as ‘loyalty to historic Buganda’ contra ‘loyalty to efficiency and progress as defined and prompted by British administrators’.Footnote71 This was most evident in the animosity of the Bataka (Baganda clan heads) towards members of the Baganda elite for their alleged ‘collusion with colonial functionaries’, not least for threatening to abrogate traditional land rights.Footnote72 Concerning Wandegeya, Buganda Prime Minister (Katikkiro) Nsibirwa and Buganda Treasurer (Omuwanika) Kulubya were the principal targets of traditionalists’ rancour. Nsibirwa had earned the ‘hatred’ of the Bataka movement by supporting the Protectorate Government’s efforts to purchase land for the development of Makerere College, while Kulubya – the largest landowner at Wandegeya – had been the sole Lukiiko member to support the Colonial administration’s proposed amendment of Article 15 of the Buganda Agreement to permit compulsory purchase of mailo land.Footnote73 In this context, Governor Mitchell’s proposal for resolving the Wandegeya impasse transpires, in retrospect, as ill-considered at best and incendiary at worst.Footnote74 Indeed, the primary reason for the Baganda to have agreed at all to the incorporation of Wandegeya within the Township had been ‘in order that succeeding generations may enjoy the profits and incomes derived from the increased land values’.Footnote75

The outbreak of the Second World War curtailed progress in preparing a regulative framework within which the planning of Wandegeya could proceed; the Director of Surveys stating in 1945 ‘There the matter has rested until now.’Footnote76 A draft Town and Country Planning Bill, formulated in 1939, was held in abeyance during the war as was the crucial issue of whether the policy of ‘protective’ segregation should remain in place at Wandegeya.Footnote77 In January 1945, contemporaneously with Ernst May’s recruitment, this contested planning terrain became more volatile when violent strikes and so-called disturbances broke out in Buganda.Footnote78 The causes imbricated a constellation of factors including African discontent over inflation, wage levels, and marketing regulation, as well as perceived corruption within the Lukiiko.Footnote79 Importantly, the ‘disturbances’ further stalled enactment of the Town and Country Planning Bill; the Attorney General arguing on advice given by the Buganda Resident that ‘any attempt to apply the Bill to native-owned land in Buganda would arouse the most strenuous opposition and stir up discontent’.Footnote80 Governor Hall, who assumed office only days before the disturbances, postponed enactment of this legislation but concurrently orchestrated a purge of Lukiiko members implicated in the disturbances.Footnote81 Commentators have interpreted this as a strategy to out-source the prizing open of Wandegeya by manufacturing the Lukiiko’s consent to pass the Buganda Government ‘Law to Empower the Kabaka to Acquire Land for Purposes Beneficial to the Nation.’Footnote82 However, the ruse backfired when Nsibirwa – reinstated as Katikkiro during Hall’s purge – was shot and killed at Namirembe Cathedral on 5th September, evidently because of his role in orchestrating the passing of the aforementioned Buganda Government legislation. Following Nsibirwa’s murder, Hall, acting on the advice of the Resident, informed the Director of Surveys that ‘the present time would be most inopportune for an approach to the Buganda Government with the object of acquiring land at Wandegeya, nor is it considered desirable to introduce Town Planning Legislation’.Footnote83 While both issues were placed in abeyance for a further six months, Governor Hall notably added that he saw ‘no objection to Mr. May re-planning Wandegeya as a commercial and residential area for Africans’ (emphasis is added for, as is discussed in section two, May did not follow this brief).Footnote84 Given the volatile context, Hall’s seeming disregard for the potential repercussions of the appearance of a European town planner in Wandegeya transpires as surprising. Indeed, at nearby Mulago, anthropologists Southall and Gutkind concluded that ‘any surveyor … arouses the greatest suspicion and gives justification to the residents that the day is not far off when everybody will be asked to leave’.Footnote85 Why then, with what the colonial administration termed ‘the political virus’ coursing through the veins of Buganda and the issues of segregation, mailo land and the planning bill still unresolved, was Ernst May commissioned to re-plan what was arguably the most troubled ground in Kampala? Furthermore, how did May’s plans articulate with what this section of this paper has shown to have been the fraught political realities of late-colonial rule in this context?

The Wandegeya development scheme

In the context of an Empire-wide problematization of needing to re-conduct the socio-spatial conduct of African [urban] life at the ‘turning-point’, and an emergent bio-political form of government which rendered society technical and prioritized ‘planning with a capital P’, not least town planning, May’s recruitment was not extraordinary.Footnote86 Colonial Office concerns over ‘African’ urban housing had, by the early 1940s, become critical and the need to find solutions to the task of articulating what Rabinow terms the ‘normalization of the [African urban] population with a regularization of [urban] spaces’ stimulated the recruitment of ‘experts’.Footnote87 It seems no coincidence that in 1944, the year the Land Officer received authorization to make an agreement with Ernst May to conduct ‘town planning work in Kampala’, that Gardener-Medwin was appointed town-planning advisor to the West Indies, Fry and Drew were appointed planning advisors in the Gold Coast, Thornton-White commenced work on the Nairobi Master Plan, and the Colonial Housing Research Group was formed to advise the Colonial Office on housing in the colonies.Footnote88 This portended the gradual assemblage of a regime of practices including techno-scientific institutions and networks of knowledge that, by the early 1950s, saw the institutionalization and circulation of specific architectural and urban planning norms and forms.Footnote89 Leitmotifs included: ‘family’ rather than ‘bachelor’ housing; ‘neighbourhood units’ as mise-en-scène for stage-managing what the Nairobi Master Plan (1948) termed the ‘translation of the values of tribal life into modern terms’; and a belief that ‘architectural design in the tropics’ should, to cite May, develop ‘its own special features’.Footnote90

In Uganda, May’s recruitment reflected the aforementioned concerns over ‘African’ urban housing. In 1943, Assistant Chief Secretary Nurock deemed imperative the ‘planned modern development of residential locations on the environs of Kampala … for the different races’, adding ‘I think we are bound to accept racial segregation in this connection.’Footnote91 Nurock’s observation that there already existed ‘the beginnings of an African suburb, if you like to call it that, at Naguru’, intimated a central focus of May’s Kampala Extension Scheme; his contract instructing him to draw up a ‘complete Development Scheme for all that area of land known as the Kololo-Naguru area’.Footnote92 This planning scheme, which included the large Naguru and Nakawa African housing schemes, receives comment in section three concerning the critical appraisal of May’s Kampala planning oeuvre.

The focus in this section concerns May’s commission, awarded in October 1945, to re-plan Wandegeya as a ‘commercial and residential area for Africans’.Footnote93 The aim is to examine how May’s Wandegeya plans articulated with the contested planning terrain elaborated upon in section one, and to provide a basis for examining the Colonial Administration’s critical appraisal of May’s Kampala plans in section three. Wandegeya, it should be emphasized, was no planning footnote or anomaly in the Colonial project of brokering new limits for the sayable and the doable in re-planning cities for African ‘inclusion’. Indeed, in 1948 the Chief Secretary urged that ‘It would be preferable not to treat Wandegeya as a separate [planning] issue, but as part of a definite and unambiguous policy which it is hoped Government will shortly define in respect of the larger general problem.’Footnote94

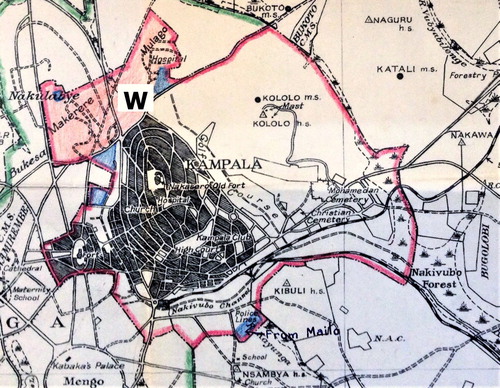

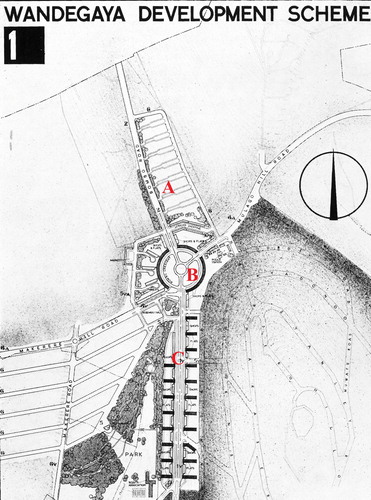

The Wandegeya Development Scheme comprised three components; a boulevard (Bombo Road) flanked by 19 multi-storey housing blocks and 17 one- and two-storey shop buildings; a large traffic circle surrounded by apartments and shops; an area for African housing and ‘African shopping’ to be located north of Bombo Crescent ().Footnote95 May’s report, which comprised two plan drawings and a three-page typed report with sections on ‘traffic’, ‘housing’, and ‘green areas’, begins by stressing Wandegeya’s ‘special importance’; reference not to the politically complex planning context but rather to the site’s functional importance as a junction at the confluence of traffic flowing into and out of Kampala.Footnote96 Accordingly, he planned a large roundabout at this junction to be encircled by ‘Bombo Crescent’ with a perimeter service road to facilitate access to shops that were to be located on the ground floors of six-storey apartment blocks. Social infrastructure including a local market, social centre, and police station were to be located in close proximity to the Crescent.

Figure 2. Wandegeya Development Scheme 1. A: Area for African housing. B: Bombo Crescent. C: Mixed ‘Asian’ and ‘Advanced Africans’. (Buekschmitt, Bauten und Planungen, 92).

The section of Bombo Road running south from the crescent was to incorporate residential and commercial uses aligned along an enlarged four-lane Bombo Road (). Displaying May’s trademark attention to topography and quality of living environment, the 4–6 storey apartment blocks were aligned to minimize traffic noise, improve aspect and facilitate ventilation, the latter by connecting the apartment blocks with only one-storey retail buildings.

May was careful to point out that the residential areas surrounding Bombo Crescent and flanking Bombo Road were to be ‘preferably Flats for Asians and advanced Africans’. As is particularly evident in the larger Kampala extension plan, May’s logic of cultural difference presupposed a strictly racially segregated spatial order.Footnote97 It is, therefore, notable that he planned to mix ‘advanced Africans’ and ‘Asians’, especially considering he had only recently designed a model house ‘to meet the psychology of advanced natives’ which was essentially a pre-fabricated ‘modern’ interpretation of the African hut.Footnote98 Furthermore, such racial mixing somewhat contradicts Gutschow’s recent claim that May’s ‘modern Zeilenbau’ (row-house) housing was ‘reserved only for the highest levels of colonial society, the Europeans’.Footnote99

The internal and external designs for the apartment blocks incorporated elements of the Zeilenbau housing employed by May in Frankfurt and Russia.Footnote100 These included a signature preference for low-rise building and the replication of the lay-out and living space of ‘the minimal dwelling’ (Die Wohnung für das Existenzminimum), the latter designed to be cost-efficient, compact, functional and technologically advanced for the given context (e.g. elevators, ‘Frankfurt’ kitchens, and bathrooms).Footnote101 Certain modifications were made to suit local climatic conditions including outdoor galleries and row alignments designed to shade rather than maximize sunlight.Footnote102

Miller Lane argues that, for May, minimal dwelling reflected not only post-war austerity, ‘but was also an act of faith … a rejection of things … and the erection into an aesthetic dogma of a way of life simple enough for the poor and therefore appropriate for all’.Footnote103 Henderson further emphasizes how the design of the minimal dwelling can be read as a schema for May’s ‘socially conservative and patriarchal’ ideas on society; planned not only for, but as one technology to bring into being ‘a modern [nuclear] family type’.Footnote104 The migration of the ‘minimum dwelling’ to the Wandegeya context tends to support such claims and to emphasize what Gutschow understands as May’s unwillingness ‘to see and appreciate local people and culture’ and the universalism of his belief in ‘planning as a tool to educate people and to create a communal culture, or Gemeinschaftskultur, among urban dwellers’.Footnote105 In the colonial context, May conceived Gemeinschaftskultur not in the singular but as a multiplicity of (racial) cultures, albeit framed within an evolutionary telos that envisaged some ultimate point of convergence, as intimated by his reference to ‘advanced Africans’ and that Africans eventually ‘may graduate to full citizenship’.Footnote106

May’s use of spatial planning as a tool for fostering communal cultures among a population deemed ‘without previous training in citizenship’ would be further demonstrated in the third component of the Wandegeya plan; an area for African housing and ‘African shopping’ situated north of Bombo Crescent (‘A’ in ). This area exhibited trademark features of May’s European planning but also those being developed by his contemporaries Thornton-White, Medwin, and Fry, which were beginning to circulate in publications.Footnote107 Firstly, use of a nested hierarchy of neighbourhood units equipped with educative social infrastructure for building ‘communities’ among a population that ‘have seldom done much thinking of their own, let alone been prepared to think and act co-operatively’.Footnote108 Secondly, generous provision of green spaces including ‘ample open areas for recreational purposes’, which May deemed necessary to counterbalance the anticipated ‘increased density of population’ with the expected expansion of Makerere College.Footnote109 Thirdly, preventing ‘sprawl’, which at Wandegeya saw May do ‘away with the customary one-storey building’, opting instead for two-storey semi-detached houses encircling greens.

May’s Wandegeya scheme demonstrates his continued fidelity to both the International Style and garden city planning principals.Footnote110 While the former informed the southern Bombo Road component, the latter characterized the African housing area evocative of the small housing developments (kleinsiedlungen) planned by May in Silesia between 1919 and 1925.Footnote111 True to the planning and architectural aesthetics of both styles, May concluded his plan with the hope that ‘the Body responsible for the architectural development for this part of Kampala’ would ensure ‘architectural harmony’, a requirement that he deemed even ‘graver’ in areas ‘settled by a variety of racial groups’. To meet this challenge May recommended that a ‘model in a scale not under 1:500’ should be made of the Wandegeya area ‘so that the advanced, as well as the more primitive type of builders may visualize the character of the development’.

In summary, May’s Wandegeya plan evidences little attentiveness to the troubled planning ground. This is evident in his plan drawings for the Bombo Crescent and the African housing development which are drawn over the traced outlines of existing mailo plots. The resulting palimpsest offers a stark representation of conflicting representations of urban space; modern urban development striated by western planning tenets and universalizing aesthetic erasing an actually existing, and staunchly protected, vernacular place. Indeed, seemingly ignoring Bagandan opposition to losing individual mailo rights, May was explicit on the need for such erasure:

Town planning schemes of a scope as suggested by the author cannot be realized as long as the land is in private ownership. It is imperative to form a Holding Company of one type or the other for the organized development of this area.

The plan thus transpires as an authoritarian socio-spatial intervention, albeit one which was anchored in a rationale of African ‘improvement’. Furthermore, aspects of May’s Wandegeya plans, as with the Kampala scheme, supports Gutschow’s claim that he was ‘notoriously stubborn in sticking to his own proud ideals’.Footnote112 Indeed, unlike Thornton-White in Nairobi, May did not employ a sociologist and, notably in terms of the intensifying exchange of planning ideas at the time, neither was May seemingly corresponding with Thornton-White, the latter writing to a colleague in 1947 ‘I have not been able to discover Ernst May’s address. He is not on the phone … ’Footnote113 How then was the Wandegeya plan appraised by the Administration?

Appraising the Wandegeya development scheme

Following its submission in January 1948 May’s Wandegeya plan was appraised by the Town Planning sub-Committee and the minutes were then discussed by the Kampala Township Authority. The latter unanimously agreed with the formers proposal that ‘the area to the west of Bombo Road [land already acquired from mailo] should be reserved as an open space’ and no apartment blocks permitted.Footnote114 Concerning Bombo Crescent and the area for African housing the sub-Committee accepted ‘with regret’ the Buganda Resident’s statement supporting the Baganda Ministers refusal to permit non-Africans or changes to existing land holdings. The Sub-Committee duly recommended that instead of May’s ‘elaborate’ scheme a ‘modest scheme’ should be prepared by the Government Town Planner or by the Township Authority.Footnote115 In July 1948, the Land Officer concurred on the basis that ‘it is obvious that no African is in a position to erect buildings to the standard envisaged by Mr. May’.Footnote116

Once again the issue of opening Wandegeya to non-Africans arose, the Chief Secretary stating: ‘it is a great pity that the question of non-native occupation was not decided one way or the other before Mr. May was commissioned’.Footnote117 Correspondence intimates that May was in fact recruited by the Ad Hoc Planning Committee on erroneous grounds. More specifically, the committee had commissioned May because:

it was said that the land-owners were desirous of having the area planned and of leasing their plots to Non-Africans for trading purposes. It was on this assumption that Mr. May produced the rather elaborate plan which is now under consideration.

The Land Officer added, however, ‘It is now obvious … that the Regents take a different view to that expressed by the Katikiro [then Nsibirwa] and the Lukiiko in 1937.’Footnote118 Indeed, when the Kampala Township Authority urged for ‘a definite decision’ be made on this issue the Resident and the Baganda Regents reasserted that ‘no non-native occupation should be allowed’, albeit with the important qualification that it was the case that ‘the Wandegeya area requires re-planning’.Footnote119 The Land Officer accordingly recommended that the newly enacted Town and Country Planning Ordinance (1948) or the Buganda Town Planning Law (1947) should be used to enable a revised plan to be drawn up for Wandegeya, albeit with the rider that ‘any really effective and orderly scheme’ would be impossible without compulsory land purchase.Footnote120

In December 1948, the Executive Council advised the Buganda Government that Wandegeya should be reserved for African development and invited them to plan the area, in consultation with the Government Town Planning Officer and the Kampala Township Authority, as a centre of African commerce, albeit with the rider that this should not exclude the possibility of ‘a limited number of high-class plots suitable for leasing to non-natives’.Footnote121 However, Henry Kendall, recently arrived from Palestine to become the first Government Town Planning Officer in Uganda, deemed the existing Buganda Planning Law (1947) ‘totally inadequate if anything is to be achieved from the planning point of view’ and in March 1949 it was agreed that a draft of a new planning law under the Native Government should be prepared.Footnote122 However, in April 1949 a new wave of violent disturbances erupted in Kampala once again bringing planning to a halt.

Understanding the reception of May’s Kampala plans

The latest inventory of May’s lifework simply lists his Wandegeya plan as ‘not realized’.Footnote123 The foregoing analysis begins to contextualize this outcome by surfacing the tensions between planning and the political realities of colonial rule. In 1930, A.E. Mirams introduced his own Kampala scheme with the prescient words: ‘To commence the work of preparing a development scheme without first having reached a clear conception as to the goal to be achieved, would be to commit a blunder of the first magnitude.’Footnote124 By widening the analysis from the Wandegeya scheme to include May’s Kampala Extension Plan, not only do Mirams words gain veracity, but a number of other factors also come into view, including continuities in May’s longer planning trajectory, that elucidate the limited implementation of his plans.

The lack of a ‘clear conception as to the goal to be achieved’ rings truest for the Colonial Administration. Officials enlisted in January 1948 to appraise May’s Kampala extension plan agreed that May’s instructions had been imprecise; Development Commissioner D.G. Harris stating how the ‘absence of any clear definition of Government policy’ meant that ‘Mr. May has been bound to make assumptions.’Footnote125 Even Governor Hall candidly concluded that ‘Mr. May’s principle difficulty has been that he has been working for a client that doesn’t know what it wants and needs to have his mind made up for him, and, having had his mind made up, changes it every six months.’Footnote126 Officialdom further admitted that ‘viewed academically and purely as a piece of town planning’ May’s plans were of ‘very considerable interest and merit’ and represented ‘an excellent piece of professional town planning work’.Footnote127 Nonetheless, admittance of both an unclear brief and the high standard of May’s plans did not prevent Government Departments from lambasting essentially all aspects of his plans.

The critique mixed urban ‘comparativism’, which posited British planning knowledge and technologies as the reference point for evaluation, with claims that May’s misreading of the problem had resulted in spurious solutions, particularly regarding proposed depth of ‘visibility’ and technical infrastructure envisaged for creating ‘new conditions’ for urban Africans, the subjectivities to be achieved, and gross indiscretion in enunciating the forms of knowledge defining his plans.Footnote128 More specifically, (1) extravagance in the provision of social and material infrastructure, (2) racial segregation, and (3) the terms in which the plan was enunciated.

Concerning the first, the Director of Medical Services ridiculed May’s ‘extravagant’ provision of six neighbourhood health centres at Naguru when an equivalent housing area in the UK would have only one.Footnote129 The Director of Public Works envisaged the proposed road system as ‘very expensive’, and mockingly referred to the likelihood of realizing the sewage disposal system in terms of ‘pigs flying’. The Development Commissioner argued that the plans were ‘far more elaborate and far more costly than Kampala will ever be able to afford’ particularly concerning the ‘lavish’ provision of social services and recreational facilities’, the latter including a park to be flanked by ‘sweet shops, shooting galleries, and merry-go-rounds’.Footnote130

Concerning segregation, it can be argued that because May was the first to plan for and visually represent zoned African housing (Naguru, Nakawa, and Wandegeya) it was impossible to hide the disjuncture between the sayable and doable that the Colonial Administration had hitherto been able to cloak in rhetoric, i.e. reconciling official denouncements of racial segregation with continued de facto segregation in essentially all policy areas. This contradiction is exemplified in the Central Town Planning Board’s question; ‘Does the reservation of Naguru for Africans, with all the African institutions concentrated there, constitute an infringement of Government’s policy of no segregation?’Footnote131 Similarly, D.G. Harris remonstrated that May’s Kampala extension plan ‘enunciates in terms a policy which Government has never accepted and may possibly be reluctant to accept’ while also stating ‘segregation is inevitable’.Footnote132 May was of course not alone in facing the conundrum of reconciling the doable with the unsayable but seemed less inclined to obfuscate than others. In Mombasa, for example, where Thornton-White and the sociologist Silberman were planning in a similarly tense political context, Silberman wrote how ‘nature has offered a beautiful means of segregation: four races and four municipal areas … Needless to say we won’t call it segregation as this word would cause a revolution’.Footnote133

Harris’s phrase ‘enunciates in terms’ relates to the third mention aspect of critique; i.e. that the discursive framing of the ‘African’ subject used by May to justify a particular spatial arrangement – i.e. educative segregation – was anchored in a form of knowledge no longer enunciable in government policy. Research has previously highlighted the paternalism and social evolutionism in May’s Kampala extension plan, but not the manner in which his unguarded ‘references to the backwardness of the African’ not only piqued colonial officialdom but, more importantly, raised fears that it risked inciting further disturbances.Footnote134 Notably, while it was evidently uncontroversial for Governor Hall to write in his foreword to Worthington’s Development Plan for Uganda (1946) that ‘the Africans of Uganda are indolent, ignorant, irresponsible’, it was deemed unthinkable for Hall to accept May’s invitation to write a foreword to the 1948 Kololo-Naguru plan, if not so much because of May’s ‘music-hall Teutonicness of thought and method of expression’, then certainly for his ‘repeated emphasis on the primitive nature of the African population which are entirely unpalatable to Government’.Footnote135 Exasperation over May’s language particularly related to concerns that eventual publication of the plans in the vernacular press would be taken as ‘a statement of Govt. policy whatever explanation is given them’.Footnote136 The Chief Secretary duly concluded that ‘there is no possibility of the May report being accepted by Government in anything like its present form’ and ‘should not be shown to the Editors of the Vernacular Newspapers’. Government, he added, should distance itself from this ‘sleeping dog’ by also refusing to print it as a Government publication.Footnote137 Trepidation was compounded by the fact that May had – in retrospect wittingly – secured the ‘somewhat unusual right of publication whether the Government accepts it or not’.Footnote138 Indeed, May’s self-published Kampala Extension Scheme would soon be circulating in influential networks as requests for copies arrived from Harvard University, The Danish Town Planning Institute, Bristol University and elsewhere.Footnote139

The above discussion evinces how May’s plans clearly ‘clash[ed] with power’. While the plans were not inconsequential; a modified form of May’s Nakawa housing scheme for bachelor labour was initiated to meet the ‘initial vital housing supply’, and the Naguru plan was used as a ‘general guide to the lay-out to be adopted’, by mid-1948, May’s Kampala planning episode effectively ended. Planning commissions at Jinja and the Kibuga, awarded to May in early 1948, were taken over by Government Town Planner Kendall who, it has been suggested, ‘ … hated all things German and modern, and systematically tried to erase all record of May’s planning work’.Footnote140 As Gutschow correctly points out, Kendall’s otherwise exhaustive historiography of Town Planning in Uganda (1955) makes no mention whatsoever of May’s planning work.

The archive has as yet yielded little regarding the extent to which May ‘argue[d] with [power] and exchange[d] … strident words’. Despite claims that May’s work bore the ‘mark of a lack of consultation with relevant Government authorities’, May himself professed that his work had progressed in ‘harmonious co-operation’ with the officers of the Protectorate Government.Footnote141 The only documented instance of May exchanging strident words with officialdom concerned a relief model of Naguru made by May’s partner C.M. Pearce for the astronomical sum of £2122, despite May’s contract stipulating a maximum cost of £150.Footnote142 This precipitated an increasingly vitriolic exchange between colonial officialdom and May and Pearce – both being termed ‘casual and presumptuous’ and Pearce being accused of attempting ‘to pull a fast one on Government’.Footnote143 A number of factors, including the elaborateness of the plans themselves, May’s foresight in securing publication rights, and the spectacularly expensive model (subsequently exhibited at the 1950 Exhibition of East African Architecture) arguably intimate that May, unlike his client, had an unwavering conception of a goal to be achieved; using the commissions to re-establish his international reputation. It is conceivable that elaborateness was necessary largely irrespective of its political or economic feasibility in the given context to ensure that his plans did not, to continue Deleuze’s dictum, ‘fade back into the night’.Footnote144 Indeed, the Chief Secretary’s statement that ‘Mr. May’s plan is the ideal plan; the task of preparing a plan which will come within the purview of practical politics is still before us’ resonates with critique of May’s Frankfurt planning, Henderson stating ‘critics charged that May’s office was more interested in impressing its professional peers than providing social housing framed in realistic terms’.Footnote145 Perhaps the aforementioned model can be said to stand as emblematic of May’s Kampala planning oeuvre; ‘outstandingly good’ but nonetheless a ‘white elephant’.Footnote146

Conclusion

It was conjectured that the years preceding and during May’s commissions represented, at least in rhetoric and policy formulation, a ‘turning-point’ to bio-political colonial government which professed to target and conduct the quotidian conduct of African urban life in line with the developmental aim of regulating and optimizing productive forces. Murray Li has argued that in governmental projects of social development, the recruitment of experts to propose solutions involves the ‘extraordinary ambition’ to ‘get the social relations right’.Footnote147 As this paper illuminates, tensions arose between May and the Colonial Administration and also within and between the Colonial and Native Administration’s over different understandings of the ‘right’ socio-spatial relations and appropriate ‘disposition of [a complex of] men and things’. As Lemke argues, Foucault’s formulation intended that ‘men’ could be tactically governed and disposed as ‘things’ in order to achieve strategic governmental ends.Footnote148 For the Wandegeya case it is shown how a crucial tension concerned the spatial disposition of ‘Asians’ as ‘things’ qua their utility as facilitators of ordered urban development. As May’s Wandegeya scheme was premised on an ultimately unattainable spatial disposition of ‘Asians’, principally due to Baganda opposition, the scheme was shelved.

This study further illuminates how a crucial tension between planning and the political realities of colonial rule concerned pertained to different understandings of the forms of visibility and the technical means deemed necessary for the operation of a new regimes of practices. May’s proposals for both the Wandegeya and Kampala extension schemes were equipped with a depth of governmental visibility and technology designed to promote new African urban lifestyles and the new African subject. For the colonial administration however, particularly in the context of Governor Hall’s belief in industrial development as a means to achieve African welfare (rather than vice versa), May’s proposals – even if seemingly congruent with wider colonial policy goals of stabilization and detribalization – were deemed over elaborate, costly and potentially incendiary in terms of his enunciation of forms of knowledge of the African that the administration could not, at least publically, condone for the given political context.

If we extend what Herbert terms the ‘taut rubber band’ that potentially articulates any case study with wider horizons of knowledge production, this specific case serves, over and above filling a gap in May’s African planning oeuvre, to facilitate and invite comparative analyses of how architecture and planning (and architect-planners) articulated with conflicting rationalities between different domains of Colonial and African government (bio-political, economic, etc.) at specific historical junctures.Footnote149 For, as Legg has importantly argued, the tendency to fetishize bio-politics has detracted attention from considering how other domains of government may have been regulated according to competing rationalities. His contemporaneous case of the re-planning of Delhi shows, for example, that despite a clear momentum towards, and demands for bio-political regulation of the population of Delhi through urban improvement, the rationality of the economic domain of government – which demanded financial stringency – caused the colonial state to ‘dig in its heels’ against constituting a coherent assemblage of mechanisms and calculations of bio-political power (e.g. health, education, housing, etc.), at least until ‘the political context became threatening’.Footnote150 This resonates with the case of Kampala, but with important place specific differences, not least that political instability did not signal any immediate bio-political response. Furthermore, while May’s Kampala plans spoke more to the bio-political than the economic domain, to posit that the colonial administrations’ opposition to them was based only on cutting costs seems questionable. Rather than positing a choice between a bio-political or an economic rationality, or conceiving the inception of ‘new life’ through comprehensive bio-political investment as a fundamental necessity to longer term economic prosperity (as in the West), in this case we should understand the intended strategic finality at the level of anatomo-politics centred, not on producing new life, but on disciplining and optimizing the capabilities of existing life within a largely maintained – albeit smoke-screened – racial tableaux.Footnote151 To this end, the ‘obedient’ Henry Kendall rather than the self-determining and perhaps ‘glory’ seeking Ernst May was more aligned with the strategic aims of anatomo-political colonial power investments, particularly as succinctly enunciated by D.G. Harris in 1949; ‘What we are trying to do, I think, and succeeding in doing, is to put new life into an existing living organism and not to produce a litter of new ones.’Footnote152

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Andrew Byerley is Senior Lecturer in Human Geography and Researcher based at the Department of Human Geography, Stockholm University. His main field of research is colonial and post-colonial urban planning, particularly concerning questions relating to power, space and labour housing in Uganda and Namibia. He is currently conducting a large research project (funded by Riksbankens Jubileumsfond) on ageing in African cities.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The Notice Newspaper, Kampala. July 2013.

2 Mertins, “Introduction to Behrendt,” 4; Lane, Architecture and Politics, 127; Lane, “Architects in Power,” 295; Mumford, The Culture of Cities, 453.

3 Lejeune, “From Hellerau to the Bauhaus,” 60; Lane, “Architects in Power,” 284; Kutting, Neues Bauen.

4 Flierl, “Ernst May in the Soviet Union,” 177; Barykina, “Transnational Mobilities.”

5 Gutchow, “Das Neue Afrika,” 379. May to Mumford.

6 Herrel, Ernst May; Ogura, “Ernst May and Modern Architecture.”

7 Gutschow, “Das Neue Afrika”; Göckede, “The Architect as a Colonial Technocrat”; Cohen, “Architectural History and the Colonial Question,” 350; Rabinow, French Modern; Wright, The Politics of Design.

8 See, for example, Myers, “Intellectuals of Empire”; Demissie, Colonial Architecture; Avermaete, Karakayali, and von Osten, Colonial Modern; Njoh, French Urbanism in Foreign Lands; d’Auria, “In the Laboratory and in the Field”; Stanek, “Architects from Socialist Countries.”

9 Avermaete et al., “Crossing Boundaries,” 3; Lagae, “Kultermann and After,” 6; Lagae and De Raedt, “Global Experts,” 5, 38–41; Avermaete, Karakayali, and von Osten, Colonial Modern; Lu, Third World Modernism, 11; Chang, “Building a Colonial Technoscientific Network.”

10 Göckede, “The Architect as a Colonial Technocrat,” 55; Çelik, “Le Corbusier, Orientalism,” 60.

11 Göckede, “The Architect as a Colonial Technocrat,” 55.

12 Gutschow, “Das Neue Afrika,” 387; May, Report on the Kampala Extension Scheme, 2; Home, “Town Planning,” 31.

13 McConnell, “Historical Research,” 467–78.

14 Pearce, The Turning Point.

15 Deleuze, Foucault, 44, 95.

16 Foucault, Fearless Speech, 73.

17 Foucault, “Questions of Method,” 225; Dean, Governmentality, 31, 40.

18 Dean, Governmentality, 41–4. The Buganda Government being the African authority of the Kingdom of Buganda.

19 Foucault, Society Must be Defended, 251.

20 Mamdani, Citizen and Subject, 17, 78.

21 Li, “Fixing Non-market Subjects,” 36; Hindess, “The Liberal Government of Unfreedom.”

22 Mamdani, Citizen and Subject; Powesland, Economic Policy and Labour; Byerley, Becoming Jinja.

23 Cmd 9475, EARC, para. 115 and 116.

24 Harris and Parnell, “The Turning Point.”

25 Cooper, Decolonisation and African Society; Pearce, The Turning Point; Kelemen, “Planning for Africa.”

26 Locke, On Education, 33, 36.

27 Hindess, “The Liberal Government of Unfreedom,” 94.

28 Wilson, Economics of Detribalization; Li, “Rendering Society Technical.”

29 Scott, Refashioning Futures, 25; Simone, For the City Yet to Come, 142.

30 Foucault, History of Sexuality, 138–44.

31 Worthington, A Development Plan for Uganda, iv, 45; Orde-Browne, Labour Conditions.

32 Orde-Brown, Labour Conditions, para 56.

33 PRO. CO822/130/2e Governor Hall to Sec. of State for Colonies.

34 Home, Of Planting and Planning, 181–3; le Roux, “The Networks of Tropical Architecture”; Thornton-White, Nairobi Master Plan, 7.

35 Hall, “Some Aspects of Economic Development in Uganda,” 127; Hall, “Some Notes on the Economic Development of Uganda,” xii; Cohen, “Uganda’s Progress and Problems.”

36 Omolo-Okalebo, The Evolution of Town Planning Ideas, 35–6.

37 Mutibwa, Uganda since Independence, 3.

38 Jørgensen Uganda, a Modern History, 49. ‘Mailo’ derives from land plots measured in square miles. Mailo land grants awarded to the Kabaka are owned by virtue of office rather than in person. Other mailo land is privately owned.

39 Omolo-Okalebo et al., “Planning of Kampala City,” 154.

40 Buganda Government Archives. AR/BUG/3/1/2 Buganda Town Planning.

41 Byerley, “Displacements,” 6–7.

42 Mirams, Kampala; May, Report on the Kampala Extension Scheme, 2.

43 Mirams, Kampala, 92. Original emphasis.

44 Mirams, Kampala, 72, 89–90.

45 d’Auria, “In the Laboratory and in the Field,” 330.

46 UNA.19/C00462. “Wandegeya,” Acting Director of Surveys, 2 August 1945.

47 Lane, “Architects in Power,” 295.

48 Foucault, “Governmentality,” 207–8; Huxley, “Spatial Rationalities.”

49 UNA.4/Q.014/16. Governor Mitchell, 1.4.1939 and 12.1.38.

50 UNA.4/Q.014/16 Kampala Township. January 1939.

51 UNA.4/Q.014/16 Kampala Township. January 1939; Southall and Gutkind, Townsmen in the Making, 7.

52 UNA.71/C464, Chief Secretary August 1948; Brennan, “Between Segregation and Gentrification,” 118.

53 Southall and Gutkind, Townsmen in the Making.

54 UNA.4/Q.014/21 Buganda Resident to A.C.S., November, 1943. Muganda is singular of Baganda.

55 UNA.71/C464, A.C.S. August 1948.

56 UNA.71/C464. Executive Council, Minute No. 206, 1948.

57 Byerley, “Displacements.”

58 Morris, “Sir Philip Mitchell and Protected Rule,” 311.

59 UNA.19/C00462, “Wandegeya,” 3; UNA.4/Q.014/16. Director Surveys. 29.3.1939.

60 UNA.19/C00462, “Wandegeya,” 2–3.

61 JMCA. Box 592. “Locations.” Chief Secretary. February 1937; UNA.19/C00462, “Wandegeya,” 1–2.

62 UNA.19/C00462, “Wandegeya,” 1–2.

63 Pearce, The Turning Point; Hailey, An African Survey.

64 UNA.19/C00462, “Wandegeya,” 1; UNA.4/Q.014/16. Investigation by Mr. Steil, 2–3.

65 UNA.4/Q.014/16. D.C.S to C.S. 29.3.1939.

66 UNA.4/Q.014/16. Governor, 1.4.1939.

67 UNA.19/C00462, “Wandegeya,” 4.

68 UNA.19/C00462. Director of Surveys to Chief Secretary (“Secret, Confidential”), September 1945.

69 UNA.4/Q.014/16. D.C.S to C.S. 29.3.1939.

70 UNA.4/Q.014/16. Governor, 1.4.1939.

71 Thompson, Governing Uganda, 225.

72 Gonsalves, The Politics of Trade Unions, 6; Mamdani, Citizen and Subject, 102–3.

73 Richards, “Traditional Values,” 320; Thompson, Governing Uganda, 234–5; Low, The Mind of the Buganda, 146–7. 71/C464 Town Planning Wandegeya, point 23.

74 Thompson, Governing Uganda, 22.

75 UNA.19/C00462, “Wandegeya,” 4–6.

76 UNA.19/C00462, “Wandegeya,” 7.

77 UNA.19/C00462 (Town Planning Ordinance). D.C.S. to C.S. July 1945.

78 PRO, London. CO536/213. Report of the Commission of inquiry into the Disturbances of January, 1945, 11.

79 Apter, The Political Kingdom; Scott, The Development of Trade Unionism, 9–12.

80 UNA.19/C00462. Executive Council memo. no. 16, 1945.

81 UNA.19/C00462. C.S. to Buganda Resident, July 1945.

82 Thompson, Governing Uganda, 291; Apter, The Political Kingdom, 230.

83 UNA.19/C00462. Chief Secretary to Director of Surveys, October 1945.

84 Ibid.

85 Southall and Gutkind, Townsmen in the Making, 118.

86 Harris and Parnell, “The Turning Point.” Bourdillon, “Colonial Development and Welfare,” 377–8.

87 d’Auria, “In the Laboratory and in the Field,” 333; Harris and Hay, “New Plans for Housing”; Rabinow, French Modern, 82, 170.

88 UNA.1/Q.009/03 Assistant Secretary to Chief Secretary, December 1947; le Roux, “The Networks of Tropical Architecture,” 333; White, Nairobi: Master Plan; Chang, “Building a Colonial Technoscientific Network,” 213.

89 le Roux, “The Networks of Tropical Architecture.”

90 White, Nairobi: Master Plan, 8; May, Report on the Kampala Extension Scheme, 25.

91 UNA.4/Q.014/21. Nurock to Buganda Resident, October, 1943.

92 UNA.1/Q.009/03 May’s Contract, 11 June 1945; Kololo was to house “Europeans and Asians”; Naguru, “African Communities”; Nakawa, “Itinerant African Labour.” May, Report on the Kampala Extension Scheme, 4.

93 UNA.19/C00462. C.S. to Director of Surveys, October 1945.

94 UNA.71/C464, C.S., August, 1948.

95 Buekschmitt, Ernst May, 92.

96 UNA.71/C464, “Wandegeya Development’ by E. May.

97 Tiven, “The Delight of the Yearner,” 83.

98 Tiven, “The Delight of the Yearner.” May to Mumford, June 16th 1945. Footnote 5.

99 Gutschow, “Das Neue Afrika,” 398.

100 Lane, “Architects in Power”; Flierl, “Ernst May in the Soviet Union.”

101 Lane, “Architects in Power,” 292; Fehl, “From the Berlin Building-block,” 197, 205.

102 Bauer, Modern Housing. On the focus on sun alignment in early twentieth century planning.

103 Lane, “Architects in Power,” 293.

104 Henderson, Building Culture, 100.

105 Gutschow, “Das Neue Afrika,” 382.

106 May, Report on the Kampala Extension Scheme, 2.

107 Jackson, “The Planning of Late Colonial Village Housing,” 482–3. May, Fry, and others published articles in the same edition of the Architects Year Book, 1947.

108 May, Report on the Kampala Extension Scheme, 5.

109 May, Report on the Kampala Extension Scheme, 9.

110 On the “Lingering Effects of his Garden City Training” under Unwin, see Lane “Architects in Power,” 290.

111 Buekschmitt, Ernst May, 27. See, for example, the Wirtschaftsheimstättensiedlung for Ohlau; Henderson, “Ernst May and the Campaign.”

112 Gutschow, “Das Neue Afrika,” 394.

113 University of Cape Town, Special Collections. Thornton White Papers (BC 353). D68/493. September 1947. Thornton White to Pryce.

114 UNA.71/C464. Meeting of the Township Authority Board, 13th May 1948.

115 UNA.71/C464.

116 UNA.71/C464. Ag. Land Officer to C.S. July, 1948.

117 UNA.71/C464. August, 1948. (Underlining in original).

118 UNA.71/C464. Land Officer to C.S. July, 1948.

119 UNA.71/C464. Executive Council. No.74 of 1948.

120 Ibid.

121 UNA.71/C464. Minutes of meeting of the Executive Council, December, 1948.

122 Gitler, “Marrying Modern Progress”; UNA.71/C468. Kendall to Buganda Resident, January 1950.

123 Quiring et al., Ernst May, 288–9.

124 Mirams, Kampala, 1.

125 UNA.1/Q.009/03. Memo, Development Commissioner (undated). See also UNA.1/Q.009/03. Memorandum on Mr. May’s Town Planning Scheme, 2. E. McCully Hunter, Chartered Surveyor.

126 UNA.1/Q.009/03. Governor Hall. Handwritten memo, February 1948.

127 UNA.1/Q.009/03. Development Commissioner (undated); Assistant Secretary to C.S., December 1947.

128 On “Comparativism”; see McFarlane, Learning the City, Chapter 5.

129 UNA.1/Q.009/03. Director of Medical Services (June, 1948).

130 UNA.1/Q.009/03. Development Commissioner to Chief Secretary, September 1948; This includes a full paper copy of the “DRAFT” of the May Report. September 1947.

131 UNA.1/Q.009/03. Development Commissioner. “Note on the Detailed Plan for Kampala.” Para. 4. Feb. 1948.

132 UNA.1/Q.009/03. Memo by Development Commissioner (undated).

133 University of Cape Town, Special Collections. Thornton White Papers (BC 353). Silberman Letters. B25/D68/493. Silberman to Thornton White, 3. June, 1947.

134 UNA.1/Q.009/03. Memo by Development Commissioner (undated).

135 PRO, London. CO536/218. Some Notes on the Economic Development of Uganda 1946. Governor Hall, p. x; UNA.1/Q.009/03. Assistant Secretary to C.S., December 1947.

136 UNA.1/Q.009/03. Handwritten memo, C.S. to Assistant Secretary. July 1948.

137 UNA.1/Q.009/03. C.S. to Director of Public Relations and Social Welfare. July 1948.

138 UNA.1/Q.009/03. C.S. to Governor Hall, January 1948.

139 UNA.1/Q.009/03.

140 UNA.1/Q.009/03. May to Governor Hall, February 1948; C.S. to Director of Surveys, March 1948; Gutschow, “Das Neue Afrika,” 388; Kendall, Town Planning in Uganda.

141 May, Report on the Kampala Extension Scheme, 1; UNA.1/Q.009/03. D.C. Harris to C.S., September 1948.

142 Makerere University Library. AR/UG. PR/13/2. Standing Committee on Finance. 15 July, 1949. Pearce was an architect and industrial designer based in Nairobi.

143 UNA.1/Q.009/03. C.S. to Governor Hall, July 1949.

144 Gutchow, “Das Neue Afrika,” 379. Deleuze, Foucault, 44, 95.

145 UNA.1/Q.009/03. D.C. to C.S., September 1948; Henderson, “Römerstadt,” 340.

146 UNA.1/Q.009/03. Director of Surveys to C.S., June 1949.

147 Murray Li, “Rendering Society Technical,” 99.

148 Lemke, “New Materialisms,” 9–10.

149 Herbert, “A Taut Rubber Band,” 69–81.

150 Legg, Spaces of Colonialism, 11, 150–1, 163, 209.

151 Foucault, The History of Sexuality, 139.

152 PRO, London. CO 536/219 No.W.123/14/5. Development Commissioner to J.L. Leyden, Colonial Office, London, February 1949.

Bibliography

- Apter, David. The Political Kingdom in Uganda. A Study in Bureaucratic Nationalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1961.

- Avermaete, Tom, Viviana d’Auria, Klaske Havik, and Lidewij Lenders. “Editorial: Crossing Boundaries.” In Oase (Delft), Journal for Architecture #95.

- Avermaete, Tom, Serhat Karakayali, and Marion von Osten, eds. Colonial Modern: Aesthetics of the Past, Rebellions of the Future. London: Black Dog, 2010.

- Barykina, Natallia. “Trans-national Mobilities: Western European Architects and Planners in the Soviet Industrial Cities, 1928–1933.” Planning Perspectives 32, no. 3 (2017): 333–352. doi: 10.1080/02665433.2017.1310629

- Bauer, Catherine. Modern Housing. Houghton Mifflin, 1934.

- Bourdillon, Bernard H. “Colonial Development and Welfare.” International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-) 20, no. 3 (July, 1944): 369–380.

- Buekschmitt, Justus. Bauten und Planungen. Band 1. Ernst May. Stuttgart: Verlagsanstalt Alexander Koch GmbH, 1963.

- Brennan, James. “Between Segregation and Gentrification.” In Dar es Salaam. Histories from an Emerging African Metropolis, edited by James Brennan, Andrew Burton, and Yus Lawi, 118–135. Dar es Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota Publishers, 2007.

- Byerley, Andrew. Becoming Jinja: The Production of Space and Making of Place in an African Industrial Town. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International, 2005.

- Byerley, Andrew. “Displacements in the Name of (Re)development: The Contested Rise and Contested Demise of Colonial ‘African’ Housing Estates in Kampala and Jinja.” Planning Perspectives 28, no. 4 (2013): 547–570. doi: 10.1080/02665433.2013.774537

- Çelik, Zeynep. “Le Corbusier, Orientalism, Colonialism.” Assemblage no. 17 (April, 1992): 58–77. doi: 10.2307/3171225

- Chang, Jiat-Hwee. “Building a Colonial Techno-Scientific Network: Tropical Architecture, Building Science and the Politics of Decolonization.” In Third World Modernism: Architecture, Development and Identity, edited by Duanfang Lu, 211–235. London: Routledge, 2011.

- Cmd. 9475. East African Royal Commission (Dow Report). London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1955.

- Cohen, Jean-Louis. “Architectural History and the Colonial Question: Casablanca, Algiers and Beyond.” Architectural History 49 (2006): 349–372. doi: 10.1017/S0066622X00002811

- Cohen, Andrew. “Uganda’s Progress and Problems.” African Affairs 56, no. 223 (1957): 111–122. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a094464

- Cooper, Frederick. Decolonisation and African Society. The Labor Question in French and British Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- d’Auria, Viviana. “In the Laboratory and in the Field: Hybrid Housing Design for the African City in Late-colonial and Decolonising Ghana (1945–57).” The Journal of Architecture 19, no. 3 (2014): 329–356. doi: 10.1080/13602365.2014.931329

- Dean, Mitchell. Governmentality: Power and Rule in Modern Society. Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2010.

- Deleuze, Gilles. Foucault. Stockholm/Stehag: Symposion Bokförlag, 1990.

- Demissie, Fassil, ed. Colonial Architecture and Urbanism in Africa. Intertwined and Contested Histories. Farnham: Ashgate, 2012.

- Fehl, Gerhard. “From the Berlin Building-block to the Frankfurt Terrace and Back: A Belated Effort to Trace Ernst May’s Urban Design Historiography.” Planning Perspectives 2, no. 2 (1987): 194–210. doi: 10.1080/02665438708725639

- Flierl, Thomas. “Ernst May in the Soviet Union 1930–1933.” In Ernst May 1886–1970, edited by Claudia Quiring, Wolfgang Voigt, Peter Cachola Schmal, and Eckhard Herrel, 157–195. Prestel: Munchen, 2011.

- Foucault, Michel. Fearless Speech. Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e), 2001.

- Foucault, Michel. “Governmentality.” In Michel Foucault, Essential Works of Foucault 1954–1984, Power, Vol. 3, edited by James D. Faubion. London: Penguin Books, 1994.

- Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality Volume 1: An Introduction. New York: Vintage Books, 1990.