ABSTRACT

Interwar public housing estates for native citizens in Sub-Sahara African cities, represent hybrids of global and local urban concepts, housing typologies and dwelling habits.

The authors explain such hybrids via exploratory research note as a result of transmutation processes, marked by various (non)human actors. To categorize and compare them, Actor Network Theory (ANT) is applied and tested within an architecture historical framework. Nairobi/Kenya functions as pars pro toto with its Kariakor and Kaloleni estates as exemplary cases. Their different network-outcomes underpin the supposition that actor-oriented research can help to unravel a most essential, though neglected part of international town planning history.

Introduction

As in other Sub-Sahara cities, public housing for ‘native’ citizens became a serious planning and design issue in Nairobi between 1918 and 1948. While remaining an issue beyond the 1940s and up to the 1980s, the interwar years represent the first ‘heydays’ of Nairobian public housing: guidelines were set, persistent housing concepts and ideas formulated, socio-spatial structures defined and first estates realized.Footnote1 Most importantly, during this first offset, actors involved in the conceptualization and production of ‘native’ housing manifested themselves as long-lasting. They remained part of the fluctuating set of networks that determined the material results and future modifications of the estates at stake.

This article deals with these ‘heydays’ in Nairobi, which was then the capital of British East Africa and governed under direct rule. The research presented is an introduction to the PhD-research Hybrid Artefacts: actors identified which comprises the whole twentieth century. Nairobi is presented as an exemplary case: as a city working with similar urban models, typologies and social-ethnic, not to say ‘racial’, rules as other Sub-Sahara cities and one which likewise mutated such models and typologies to fit the local context and the various actors at play. As such, this study proposes Actor-Network-Theory as method and starting point to identify, interpret and compare the actors and actor-networks at stake.

Researching Africa’s twentieth century public housing estates is challenging. Not only do these estates root in internationally dispersed concepts and locally-bound building and dwelling practices but the continuous reintroduction of pre-existing actors, such as social structures, dwelling habits and housebuilding practices, also reshaped the estates in particular and infinite ways.Footnote2 So far, urban historical interest in social housing practices has mostly focussed on housing policies, urban models, infrastructures, iconic buildings, and on the regimes and individual ‘western’ (expat) architects, planners or government officials involved.Footnote3 Researching public housing as autonomous research object is still an obscure practice, particularly in colonial studies.Footnote4 One reason is a delayed interest in this type of ‘minor’ architecture; another is the often difficult accessible – and widespread source material; for this article three archives required consulting – Bodleian Libraries (Oxford), British Library (London), Kenya National Archives (Nairobi) – as well as various university libraries, the African Study Centre (Leiden) and fieldwork in situ. Consequently, the image of the origin and construction of Sub-Sahara Africa’s twentieth century housing estates has remained somewhat incomplete and vague. Moreover, it is not easy for urban and planning theory to cover Africa’s dynamic urban realities and, on a smaller urban scale, cities’ housing estates and quartiers.Footnote5

Being part of a larger PhD investigation, the here presented exploratory research note intends to identify the origins of and mutations at play in Nairobi’s public housing estates via their actors to unravel estates’ transmutation processes. The term transmutation is coined to cover the noted transfer and mutation of (global, local) models, typologies and dwelling forms as part of larger actor-networks. For instance, although the models of Nairobi’s estates rooted in global urban dwelling models and concepts, their material results depended on the degree to which they met ‘local’ resistance and/or merged with ‘local’ practices, resulting not only in modifications but also hybrids.Footnote6 The notion ‘local’ is not connected to nationality, but defined here as those actors that have taken permanent residence in the African country and/or city in question.Footnote7 A broader definition of ‘local’ seems appropriate and necessary, certainly when taking the multicultural composition of African society into account; defining local as non-immigrant African means overseeing actors and actor-groups that actively contributed to the shaping of ‘native’ housing estates. According to Harris (From trusteeship to development, 2008), hybridity of foreign and local practices was endorsed in the British territories via the evolution of urban (housing) policy, particularly after 1929. However, this needs nuancing in Nairobi’s case. Estate models, as planned and implemented by British colonial state between 1918 and 1948, underwent noticeable modifications after realization, a practice that hints to other actors outside the institutional milieu.Footnote8 Also, dwelling models and concepts adopted in Nairobi were generally based on British notions of what ‘native’ dwelling habits were. Partly owing to British direct rule, ‘native’ citizens or ‘native’ housing typologies played no direct role.Footnote9 Nairobi was further founded as a ‘new town’, meaning that there existed no urban settlement or local building practice before the British settled there. This was not the case in all British Territories; particularly not in those under indirect rule and in those who did have a local building tradition. Gold Coast’ Public Works, for instance, considered locally-bound dwelling practices in Accra’s public housing design. It planned for the traditional Ga-compound as a dwelling typology for site-and-service schemes such as Adabraka (1910s) and Korle Gono (1910s), and used the same dwelling type in newly planned estates like South La (1929–1930s).Footnote10 Another actor determining the estates’ typologies and dwelling forms was local resistance via landownership. In Accra, Ga stools owned most of the town lands, which were leased and sometimes sold to the British state for urban development. Most urban lands in Nairobi consisted of either private or state land, a consequence of Nairobi’s new town’s origins.

Consequently, our research assumes that built artefacts are both part and result of a complex and dynamic network of actors. The latter contains in this case human actors – ethnic groups, policy makers, dwellers, architects, functionaries – and non-human actors like maps, building materials, land rights, urban design proposals, dwelling concepts and dwelling typologies and rituals. Such an approach highlights the fact that material and social dimensions were equally important for the making and mutation of Nairobi’s, and other cities’ public housing estates over time. Priority is therefore given to the identification of key actors and their comparison over time and space, with Nairobi as exemplary case.

This study combines historical analysis with oral testimony and social analysis, as the actors’ heterogeneous character and the lack of disciplinary tools calls for an adapted, transdisciplinary method.

Actor-network-theory and urban history

The use of social analysis, particularly Actor-Network-Theory (ANT), is not unheard of in urban planning studies,Footnote11 but only few have attempted to fit it within an urban historical framework specifically when they were dealing with transfer of models and concepts.Footnote12 Among the latter, Nasr & Vollait’s Urbanism: Imported or Exported? (2003) and Beeckmans’ Making the African City (2014) remain the most innovative; they introduce probing issues like (local) resistance, hybridization and modifications of transferred models and typologies and set forth innovative theoretical and methodological frameworks. However, many local actors are left out, particularly non-human ones. While Nasr & Vollait’s book focusses on local, individual narratives and on how urban spaces, functions and settlement patterns are generated via the mediation of foreign and local experts, its lack of engagement with social theory hinders its drawing of far-reaching conclusions; and although Beeckmans gives proof of a more settled social theoretical engagement by introducing oral sourcing and including actors outside of the institutional milieu, she does not analyse those actors with help of an ANT-related method. The latter however, originating in the field of Sociology, has been put forward as a helpful method for urban research.Footnote13 In tune with this assumption and by focussing on the actors involved, this article tries to make clear that ANT effectively allows for a more reliable and broader historical reconstruction of, in this case, the origination and construction of Nairobi’s public housing estates and those of other African cities than prevailing explanatory models like (neo)Marxism and (post)colonialism.

For Bruno Latour, sociologist and one of the chief spokesmen of ANT, the construction of actor-networks is a process of both human and non-human actors, meaning that both material artefacts (buildings, models, urban plans, maps) and humans have agency – the actor-ability to act or not, and to provoke thoughts and ideas – and that both play roles in the estates’ origination and construction; these assumptions correspond to those of Urban History.Footnote14 At the same time, ANT seems able to help navigate and circumference the confines of regular urban historical dualisms such as local versus global, formal versus informal or colonialism versus post-colonialism; it is the actor-connections that explain the estates, the social-material constructs, at stake.Footnote15 Projected on the topic of this article, ANT allows for an empirical-based and less ideologically-loaded unravelling of the actors involved in estate origination and construction processes.

It is of importance to underline ANT’s assumption that all actors are enrolled in networks via connections, they form networks via these connections and, in turn, are shaped by the network made. The significance of actors thus lies in the way they interact;Footnote16 limited actor-power does not translate into a negligible role in the estates’ actor-networks.Footnote17 Moreover, the formation of networks is situated in space and a continuous sphere of time, e.g. actors can be (inter)nationally/regional dispersed urban policies, plans or models, but also pre-existing ethnic groups, dwelling habits, dwelling typologies, social practices and concepts.Footnote18 In the case of this research, such analogous, layered networks manifest themselves in the production, experience and modification of housing estates. The estates themselves function as our central object of research and starting point from which the estates’ heterogenous actors can be traced and networks reconstructed.Footnote19

As actors may have an individual or a collective character, they must be approached as such. Research findings of the PhD-pre-studies (2014–2016) have so far proven that actor-collectives (or actor-groups) are important nodes in the networks traced; they influence the making of housing estates as much as individual actors.Footnote20 Also, and similar to individual actors, actor-groups produce agency via their respective networks, thus influencing estates’ material outcomes and characteristics.Footnote21 The notion of actor-groups, a refinement and adaptation of urban geographer Garth Myers’ Verandahs of power concept, links space production and individual actors to organized human power and influence, such as local Public Works departments or ethnic groups like the Ga-stools in Accra or Duala chiefs in Douala.

To facilitate comparison between actors and actor-groups of different estates/cities, timeframes are required. The latter function as benchmarks for the ANT-based network-analysis, which would otherwise become an endless mapping exercise. In this article, such benchmarks correspond to two planning phases in Nairobi’s public housing practices between 1918 and 1946: the landhie concept (1918–1929) and the garden city model (1929–1948). The latter refers to 1910s and 1920s European ‘garden city’ concepts and practices such as Letchworth Garden City (1904–1909) and Hampstead Garden Suburb (1909–1912), which were transferred and diffused to colonial territories and situations;Footnote22 Landhies refers to residential plots where railway employees lived. The word ‘landhies’ most likely derives from the word ‘lands’ and is an Anglo-Indian term for railway workers’ accommodation. It also refers to high density workers’ housing organized in lines and/or rows.Footnote23 The case chosen to illustrate the landhie typology is Kariakor estate (1928–1930s); the one to explain the application of the garden city concept is Kaloleni (1943–1948). Both estates mark the end of a planning episode in Nairobi.

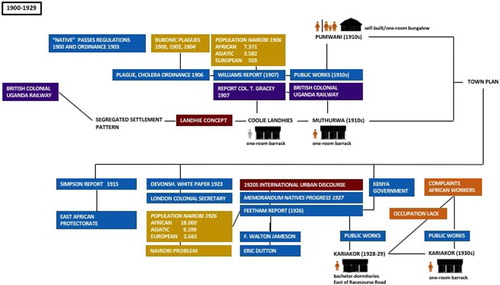

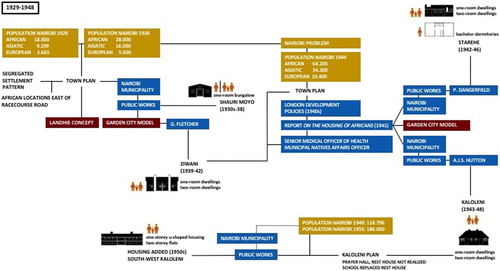

Finally, to allow for the above-mentioned analysis of a complex, ideologically-loaded aspect of urban history and to facilitate comparison, this article comes with a visualization in so-called actor-diagrams of the actors at play in Kariakor’s and Kaloleni’s actor-networks; the actors and actor-groups found are a combined result of in-depth research in different international archives, in situ analysis and oral sourcing.

A first section will deal with the case of Kariakor, while the second focusses on Kaloleni estate. A final, comparative analysis of the mentioned estates includes the ANT-diagrams and will be followed by an epilogue.

Kariakor: the ‘landhie’ concept as a persistent actor, 1918–1929

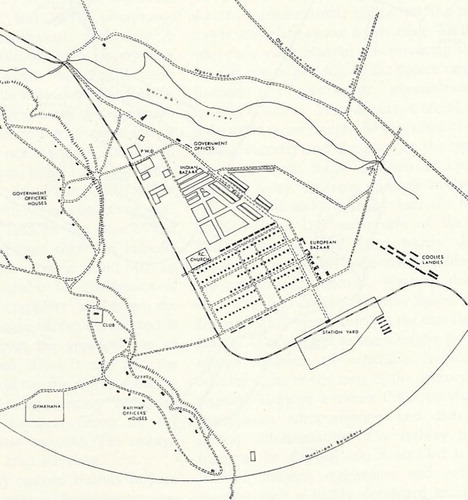

The landhie concept set the tone for the housing of non-Europeans in Nairobi between 1918 and 1929; remaining ‘a noteworthy feature of [Nairobi’s] ‘native’ housing’ practices, till at least the end of the 1920s. In Nairobi, the concept – derived from international urban design strategies and transferred to African soil – consisted of bachelor-barracks ordered according to a strict grid.Footnote24 Between the barracks, outdoor cooking and washing facilities were set in green fields, which could also be used for flower and vegetable gardens (). Kariakor estate (1928), Nairobi’s first municipal public housing scheme, is exemplary for this. Before describing this estate in detail, however, a more general analysis is needed to situate the estate within its material-cultural, sociocultural and political context, and to identify the actors at play therein.

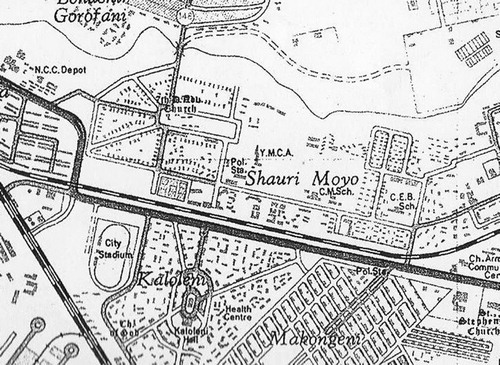

Figure 1. Landhie concept in Coolies Landhies, c. 1905, Nairobi (detail reconst. map 1967).Showing the estate’s morphology. Source: Detail from W.T.W. Morgan. Nairobi. City and Region. Nairobi: Oxford University Press.

The landhie typology roots in internationally dispersed design concepts and appeared in Africa from the nineteenth century to organise and subordinate (mostly mine-) labour and its labourers in colonial territories like Zimbabwe and South Africa; such estates were usually built for African bachelor-workers.Footnote25 Nairobi’s landhie housing though, was initially meant for Asiatic, mostly Indian, workers. This difference flows from Nairobi’s origins as a railway depot (f. 1899) for which British Colonial Uganda Railway Company primarily employed Europeans and Asiatic labourers.Footnote26 At the time, no Africans permanently lived in or had housing near Nairobi; the Native Passes Regulations – Ordinance of 1900 and 1903 – would formalize that Africans needed passes for leaving their towns and/or villages, which severely limited their movement as well as their (permanent) settlement throughout the East African protectorate (later Kenya colony).Footnote27 Consequently, no ‘native’ villages with pre-set lay-outs and dwelling typologies existed in Nairobi around 1900. It is therefore not surprising that the African dispersed mine-housing concept emerged as a primary housing type for non-Europeans around 1900. Europeans resided in typical colonial bungalows, built on a rectangular grid with a minimum of two rooms and a veranda, and which were sometimes built on pillars due to Nairobi’s swampy land; in other colonies bungalows were also predominantly accommodated white (European) colonists.Footnote28 The construction of railway workers’ housing set a precedent to separate its population by class: high-class railway officers were located west of Nairobi River and station on dryer, less swampy ground, while an estate for lower class – initially Indian – workers was realized east of the station, on the lower ground near the Nairobi River. The latter was known and mapped as Coolies Landhies.Footnote29

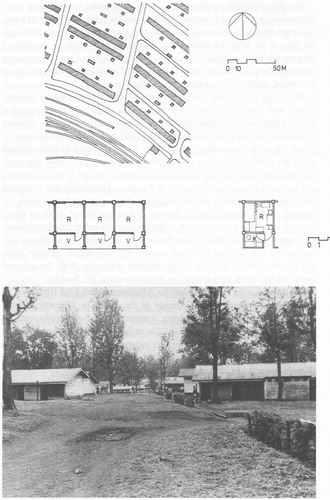

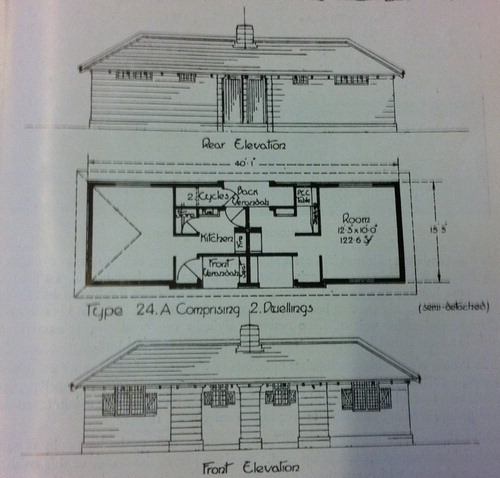

In the years that followed, Nairobi began to evolve from railway to business town, prompted among others by the East African Protectorate Headquarters’ move to Nairobi (1905), the city’s municipal status (1919) and by the protectorate’s status to colony in 1919. This climate changed the town’s demographics considerably by not only attracting white European elite and Asiatic/Indian business men but also large numbers of ‘native’ African workers. Around 1920, Nairobi’s population counted 12,000 Africans, more than half of the town’s total, which would grow to 18,000 in 1926; in the same year, Asiatic numbered 9199 and Europeans 2665.Footnote30 Due to these changes, the blend of Nairobi’s ‘mixed races’ (Europeans, Indians, Africans) within the town boundaries caused a serious planning issue; it would even be defined as the Nairobi problem by Thornton White and his planning team in 1948. Footnote31 Although welcomed and allowed to work in Nairobi town (when a bachelor worker), Africans were still not permitted to permanently dwell or settle there; a regular occurrence in East and Central Africa where until the 1940s, most colonial government denied Africans a permanent place in towns. The African presence was only tolerated when their labour was required.Footnote32 The European colonial elite was not keen on their structural presence as they envisioned Nairobi as a mostly European town; Indian housing and shopping areas had already been segregated from the European ones.Footnote33 Although, there was no housing available and no intention to provide this, Nairobi’s colonial elite did tolerate Africans setting up spontaneously-built peripheral settlements such as Kibera, Swaheli, Somali, Pumwani and Pagani on Nairobi’s outskirts; a practice that continues up to this day.Footnote34 All the same, they viewed such non-European ‘native’, as well as Indian settlements as unsanitary and as a serious public health menace for Nairobi’s other (e.g. European) areas. This fear was partly based on bubonic plague outbreaks in the lower-class railway housing and the Indian Bazaar in 1900, 1902 and 1904. In the opinion of Nairobi’s colonial elite, combining European, Indian and African housing settlements within town borders could only be achieved by rigorous ethnic-residential segregation; an approach that mirrored internationally emerging trendsFootnote35 and which was formalized in local and imperial governmental reports like the Williams Report (1907), the 1915 Simpson Report and in ordinances like Plague and Cholera Ordinance (1906).Footnote36 Ad-hoc sanitary measures had already been initiated in Nairobi, in the 1910s, by the government and the Railway Company. The latter alarmed by ‘rats, jiggers, and fleas’ in Coolies Landhies and with financial support from Kenyan Government replaced the quarters’ original clay- and- iron-covered buildings by stone ones (1910s), preserving the original landhie typology but baptizing it Muthurwa.Footnote37 Barracks were now divided into one-room accommodations, each with a small veranda and organised in rectangular blocks with back-to-back rooms in rows (). As before, cooking places and communal sanitary blocks were set in green spaces that served as collective allotment gardens. In 1941, Nairobi’s Senior Medical officer of health and Municipal Natives affairs officer would report that ‘the opportunity [..] to practise a little agriculture [was and would be an] unqualified good’ in Nairobi’s settlement design.Footnote38 Shortly after Coolies Landhies’ mutation, Nairobi municipality introduced the site-and-service scheme model in Pumwani, an extensive informal settlement at the city’s south-eastern border; similar schemes were simultaneously introduced in other African cities including Accra (Gold Coast).Footnote39 In Nairobi, the original non-planned Pumwani settlement was replaced by a regular grid on which dwellings could be built by Africans. Each prospective resident received a fixed amount of money for the purchase of construction materials such as local clay stones and corrugated roofing sheets. Nairobi’s Public Works department – installed in the early 1910s – realized elementary water supply and drainage systems. Till the 1910s, the East African Protectorate Public Works department was responsible for Nairobi town.

Figure 2. Landhie concept in Muthurwa estate, Nairobi. Showing the estate’s morphology and housing units’ floor plans. Source: A.K. Nevanlinna, Interpreting Nairobi. The cultural study of built forms. Helsinki: 1996. 226.

At the same time, Kariakor’s plan and lay-out also flowed from the Feetham report, a 1927 (official) city-wide strategy, which figures in the estate’s actor-diagram ().Footnote40 While named after the chairman of the same-named commission (1926), the main authors of the Feetham report were F. Walton Jameson, a British South African consultant planner and city engineer (Kimberley, South Africa), and Eric Dutton, an influential British Government official who worked in Northern Rhodesia, Zanzibar and Kenya in the years 1919–1952. The resulting, not fully applied report assimilated the by then widely endorsed visions of Dutton which defined the ‘native’ home as a most suitable tool to educate and transmit British social-cultural values to ‘native’ citizens.Footnote41 Dutton further stated that residential homes should be built in clearly identified urban zones, in order to maintain a separation between European prestige and – in Nairobi’s case –, the Indian and African ‘others’.Footnote42 Combined with the pre-set housing segregation, a triple ethnic-spatial division was proposed to deal with non-European, ‘native’ housing areas like Muthurwa and Pumwani: Europeans would continue to dwell in the city centre and on the higher, less swampy land, west of the station building, while Indian citizens would – more or less in line with existing practices – reside in the north of the city centre as well as north-west and north-east of Muthurwa; Africans were to be housed in Muthurwa and in new, to-be-built housing estates.Footnote43 The latter were projected east of Racecourse Road, which would act as the long searched hygienic barrier; this part of Nairobi is known today as Eastlands. This segregated town plan harkens back to the one introduced by the Railway Company, dictating that Coolies Landhies (and later Muthurwa) would be located east of the European quarters. As Nairobi’s administration was a task for Nairobi Municipality and Kenya Government, Public Works of both local and state government was responsible for the planning and design of new ‘native’ estates of which Kariakor was the first.

In line with the Feetham stipulations and with the earlier segregation practices, Public Works planned and realized Kariakor (1928–1929), north of Muthurwa and directly east of Racecourse Road. The latter functioned as a clear border between European and African housing areas and as the main access road to the estates.

Planned and meant for low-income bachelor workers, Kariakor’s typology re-applied the landhie concept, an actor that had earlier been introduced by the British Colonial Uganda Railway (). Nairobi Municipality and Kenya Government, like many other governmental institutions in East and Central Africa, assumed that bachelor-housing for African workers only required minimal facilities: a ‘bed-space’ rather than a ‘dwelling’ or ‘room’.Footnote44 Due to Kenya’s administration and direct rule system, those for whom the estate was planned, could not directly influence its making process. While similar exercises took place in Lusaka, Northern Rhodesia’s capital city, such practice differs from cities with an existing pre-colonial ‘native’ architecture and urban practice, where residents played a much more decisive role. In British Gold Coast and French Cameroun for example, the colonial state respected the existing political bodies of both Ga (Accra) and Duala (Douala), acknowledging their land-ownership. As such, the Ga and the Duala maintained and could exercise their traditional and powerful societal positions throughout the colonial period. In order to obtain or lease land for urban development, the state had to continuously interact and negotiate with such actor-groups about land and town planning concepts and typologies.Footnote45 Nairobi’s barrack-type dormitories as built in Kariakor were, however, arranged in a quasi-circular composition instead of the grid used for Muthurwa and Pumwani, as if a sense of urban community was intended; this, in turn, was certainly part of the international planning discourse at the time, starting in the 1920s and wherein the grouping of housing around green areas was supposed to create a sense of a ‘village’ community ().Footnote46

Shortly after realization though, due to complaints of African workers and combined with a lack of occupation, Kariakor’s dormitories were converted into bachelor-rooms – like those of Muthurwa – in the 1930s by Nairobi Municipality.Footnote47 The materials used for Kariakor’s houses presumably corresponded to those described in the Memorandum Native Progress 1927, namely a cement floor and iron-corrugated roofs; presumably as no original plans or drawings of Kariakor have been preserved whereas the estate’s original footprint was wiped out by redevelopment in the 1950s. A total of twenty houses in Nairobi’s native settlements already had cement floors and corrugated iron roofs at the time of Kariakor’s planning; in Pumwani, thatched and petrol tin roofs were slowly replaced by corrugated iron ones.Footnote48 As usual, sanitary blocks stood on green spaces in between the buildings.

Despite the improvements made in the 1930s, Kariakor was described by Nairobi’s Senior Medical officer of health and Municipal Natives affairs officer as ‘no more than lodgings for casual labour and not a collection of homes for labourers’ some year later.Footnote49 In 1946, Nairobi’s colonial engineer Ogilvie, a fervent criticizer of Nairobi’s housing practices, dismissed Kariakor as a pure landhie construction, insinuating that no typological renewal had been introduced since the Indian railway workers’ barracks constructed thirty years earlier.Footnote50

The garden city concept as new actor, 1928–1948

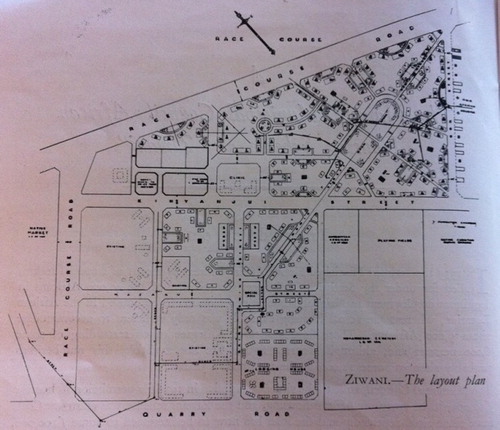

Evolving the ideas of designing an urban community for native citizens, Nairobi Municipality began to seriously experiment with the international dispersed garden city model from the late 1930s onwards. Shauri Moyo estate (1930s-38) was a first breakaway from the landhie typology, containing local facilities (shops, schools), but this effort was only firstly and fully realized in the Ziwani (1939–1942) and Starehe (1942–1946) estates and afterwards concluded in the ‘model’ settlement Kaloleni (1943–1948).

Though garden cities were predominately meant for European government employees and/or other white expatriates in Sub-Sahara Africa, some were intended for Africans; and, to mention a few, were found in Nairobi (1930s-1940s) and in the British Lusaka town plan (1930s). Common to these experiments is garden cities’ actor-role in the creation of polarized/segregated colonial housing environments. Nairobi was no exception.Footnote51 To face the ‘Nairobi problem’ (an actor since the 1920s ( and )), Nairobi Municipality and Kenya Government saw the garden city model with its cul-de-sacs, meandering roads, communal green, green spaces, communal facilities and family homes, as a more modern and better fitting solution than the landhie typology.Footnote52 Basic amenities (schools, church, shops) could guaranty the desired ethnic segregation, ensuring that Africans wouldn’t need to be in town as often. Also, such estates’ plans were supposedly more fitted and suited to the African ‘standard of living’ and assumed customs. As late as 1954, Elspeth Huxley, writer and government advisor, wrote in Kenya Today that ‘Kenya is a country of mixed races’ separated by ‘different customs, mentalities, standards of living’; something that architects and town planners should apply in their work for Nairobi and the whole of Kenya.Footnote53 Making the government’s view official, the African Housing Board’s 1941 report formalized the notion that a ‘village on garden city lines’ could stimulate ‘native’ residents to ‘observe elementary rules of hygiene without supervision’ and could, as such, result in a model settlement.Footnote54 Moreover, in the same report Nairobi’s Senior Medical officer of health and Municipal Natives affairs officer claimed that it was ‘certain that [..] the opportunity for the [native African] worker and his wife to practise a little agriculture is unqualified good’.Footnote55

Shauri Moyo estate (1930s)

Although the idea of a ‘village on garden city lines’ was formalized in 1941, Shauri Moyo (1930s) already broke with the landhie concept and therefore figures in Kaloleni’s actor-diagram (). Similar to Kariakor and following the formalized housing segregation policy of the 1927 Feetham report, the estate was realized east of Racecourse Road.Footnote56 Town and survey maps of the 1950s and 1960s – original drawings of Shauri Moyo have (most likely) been lost – show that a new design element was introduced here: a monumental oval-like space with streets radiating out of it and a Christian church as the only building standing on it ().Footnote57 One of these radiating roads functioned as the estate’s main access. This design motive most likely roots in Letchworth Garden City (1904–1909) and Hampstead Garden Suburb (1909–1912), as planned and designed by British town planner Raymond Unwin and architect Barry Parker. It is highly probable that British town planners and architects working at Nairobi’s Public Works knew these estates; either via education at and lectures delivered by the Town Planning Institute (London)Footnote58, or via the intensifying of design expertise exchange; the Town Planning Institute (f. 1914) served as the main body representing planning professionals in the United Kingdom and was headed by prominent Garden City movement architects such as Thomas Adams (1914), sir Raymond Unwin (1915) and sir Patrick Abercrombie (1925). In Nairobi, Shauri Moyo introduced placement of schools and shops around ‘quadrangles’ for the first time which consist of circular and rectangular roads that enclose small green spaces and are slightly set back from the main road; Raymond Unwin recommended such ‘quadrangles’ to ‘beautify the streets’ and create attractive outlooks.Footnote59 Other public amenities of Shauri Moyo were grouped in and around a large green field east of the oval, and in-between the housing areas and shops. Dwellings were arranged along the edges of communal greens or amidst greenery, referring to Letchworth and local practices like Kariakor. The pre-dominant housing type was a one-storey bungalow, containing two or three one-room accommodations meant for bachelors and suited for families when necessary.Footnote60 This and the fact that communal cooking and sanitary facilities were still provided outdoors, reveals the persisting assumption (an actor connected to Nairobi Municipality and Kenya Government) that ‘native’ workers only required minimum dwelling facilities (, , ). In 1941, Nairobi’s Senior Medical officer of health and Municipal Natives affairs officer stated that at the time of its realization, Shauri Moyo contained the best public houses ‘for natives so far erected in Nairobi’.Footnote61 However, according to the same officers, the estate ‘was not on the lines that the natives themselves would have preferred’ and proper implementation of the garden city model was to correct this. According to engineer Ogilvie (1946) and in line with the statement made by Nairobi’s Senior Medical officer of health and Municipal Natives affairs officer, what was needed were estates able to function as a ‘collection of homes’. In Ogilvie’s words, it would be ‘in the interest of both the Colony and the African worker himself that he should be accompanied by his family’.Footnote62

‘On the housing of Africans in Nairobi’ (30th April, 1941): an important Nairobian actor

The planning guidelines for such a ‘collection of homes’ flowed from the Kenya’s African Housing Committee’s (AHC), in the form of their 1941 report On the housing of Africans; a report that specifically dealt with the planning of ‘native’ housing. It not only incorporated the 1930s findings and recommendations of the mentioned Officer of Health and Municipal Natives Affairs Officer, but also formalized London’s post-1939 colonial development policy (). The latter stipulated that Africans and their families should have a place in Nairobi and other Kenyan towns.Footnote63 The report also appeared after the Mombasa 1939 riots which drew government attention to the fact that inadequate or over expensive housing could cause social discontent. Summarized, the report concluded that Nairobi Municipality needed to supplement the available housing stock in the African ‘locations’ as these could only accommodate 9000 AfricansFootnote64 whereas dwellings for 15,000 people were required. Moreover, the resulted overcrowding had led to sanitary conditions which threatened ‘the [social and physical] welfare’ of the ‘natives’. In the opinion of Nairobi’s Health and Native affairs officer, this unacceptable situation was caused by ‘all the existing housing [of] the lodging type [e.g. landhie type], with a low standard of accommodation’; this should not be repeated. In line with London’s colonial development policy, the report stated that ‘in the proposed housing, accommodation for the family should be[come] the prime object’,Footnote65 and encouraged Nairobi Municipality to consider estates for ‘a [new] Nairobi urban working class’; it believed that estates provided with their own amenities and institutions would ‘[certainly be] welcome[d]’ by the ‘native’ African.Footnote66 Consequently, the report recommended the establishment of a ‘semi-rural village on garden city lines’ out of which ‘a model community’ could result;Footnote67 settlements of this kind already existed successfully in the Union of South Africa.

Recommendations such as traffic safety were also put forward by the African Housing Committee as recipes for Nairobi’s indigenous housing problem; in Kaloleni for example, pedestrian roads lead from the communal oval to the dwelling units. This is a remarkable difference with Accra’s housing practices, where no such national housing committee was installed, and for which no discourse of the kind could be traced so far. Lusaka (Northern Rhodesia) on the other hand, a city similar in origins to Nairobi, did set up a similar housing commission and published a report on ‘native’ housing recommendations comparable to the report on Nairobi.Footnote68

Ziwani (1939–1942), Starehe (1942–1946) and Kaloleni estates (1943–1948): the garden city concept transmutated into a Nairobian ‘model’ settlement

Ziwani became the first native housing estate in Nairobi conceived as the desired ‘collection of homes’. Municipal engineer G. Fletcher was the author of its plan; Fletcher (British) specialized in (sub)tropical housing and had shortly before participated in the conference Housing in Tropical and Sub-tropical countries (Mexico, August 1938).Footnote69

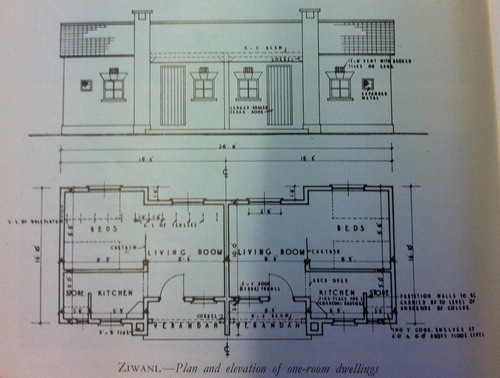

Although, Ziwani’s plan originated before the AHC report, the lay-out and typologies testify that Fletcher paid attention to the findings of the Senior Medical officer of health and Municipal Natives affairs officer of the 1930s which were summarized in the AHC report. For example, Ziwani included one-family dwellings, mirroring the growing conviction that African workers with families intended ‘to settle in the town for their working lives’.Footnote70 At the same time, Ziwani’s housing stock corresponded to various income-levels and family structures, though not mixed within one housing unit as had been the case in Shauri Moyo (1930s) ( and ). Moreover, Ziwani’s one-family houses had indoor kitchens (); of which the fire places were symbolically expressed via white plastered chimneys, a long-lasting actor that characterizes the estate’s visual appearance up to this day. A similar type of architectural expression would appear in Starehe and Kaloleni some years later.

Figure 4. Estate lay-out Ziwani, 1939, G. Fletcher. Source: G.W. Ogilvie, The Housing of Africans in the urban areas of Kenya. The Kenya Information Office: Nairobi. 1946. 28.

Figure 5. Plan and elevation of one-room dwelling, Ziwani, 1939, G. Fletcher. Source: G.W. Ogilvie, The Housing of Africans in the urban areas of Kenya. The Kenya Information Office: Nairobi. 1946. 30.

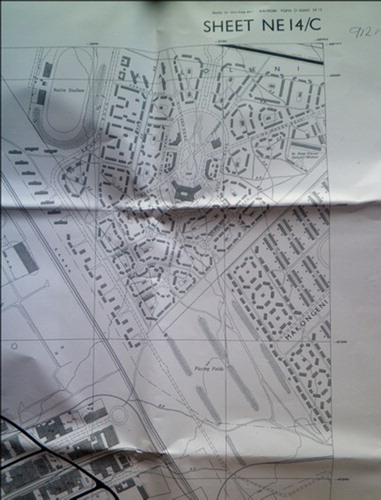

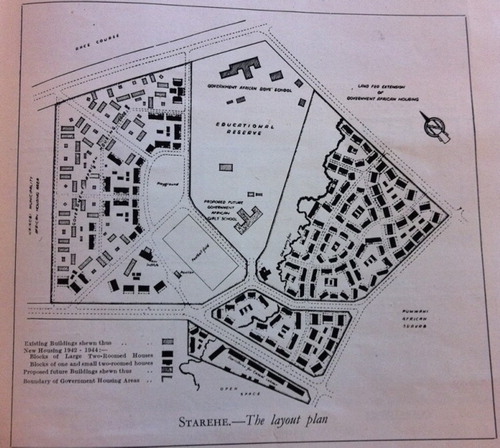

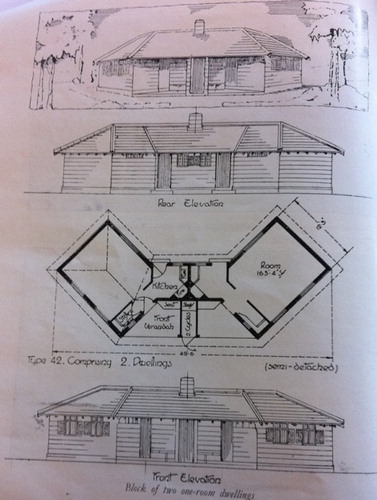

Starehe (1942–1946), the next estate based on the new policies, was designed by Kenya Government architect Peter Dangerfield. It provided one-family homes and bachelor workers’ dormitories; so far, the reason for applying the latter typology is unclear. Though it could be related to the fact that Starehe, unlike Ziwani, had to adapt to an already existing settlement (). Kaloleni (1943–1948), the then following new estate, was designed by imperial planner A.J.S. Hutton who was then employed in British Malesia, and consisted of one-family dwellings.Footnote71 As all three estates followed the same model and Kaloleni was the final product of this series of housing ‘on garden city lines’, the latter is discussed together and alongside Starehe and Ziwani which also figure in Kaloleni’s actor-diagram ().

Figure 6. Estate lay-out Starehe, 1942, P. Dangerfield. Source: G.W. Ogilvie, The Housing of Africans in the urban areas of Kenya. The Kenya Information Office: Nairobi. 1946.39.

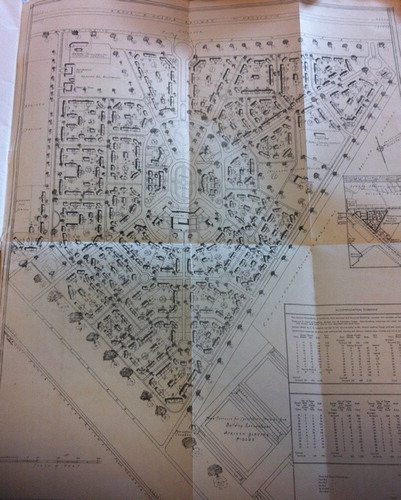

Meant to remedy Nairobi’s urgent housing shortage among government-employed Africans, Ziwani, Starehe and Kaloleni were to contain three- to six hundred dwellings and two- to three thousand citizens each.Footnote72 Similar to Kariakor and Shauri Moyo and in line with the much influential Feetham Report and existing town plan, all three estates were projected and realized east of the hygienic barrier (Racecourse Road), as extensions of existing ‘African locations’.Footnote73 Design elements such as ovals, greens, meandering streets and courtyards refer to the ‘garden city lines’ as proclaimed by the African Housing Committee in 1941 (, , ).Footnote74 Its adaption to an existing settlement may be identified as the actor responsible for Starehe’s large central green, instead of the central ovals realized in Ziwani and Kaloleni (, , ), and which functions as a space that separates the old and new parts of Starehe. In Ziwani, the central oval and another, smaller oval connect the parts of Ziwani that are located north and south of the estate’s main road (Kinyanjui street). In Kaloleni, the central oval facilitates the separation of through- and destination traffic without dividing the estate in two more or less separate parts. Two roundabouts off Jogoo Road guide through-traffic along two radiating roads and towards the central oval where the estate’s facilities are; secondary and tertiary roads lead to the housing areas ().

Figure 7. Estate lay-out Kaloleni, 1943, A.J.S. Hutton. Source: G.W. Ogilvie, The Housing of Africans in the urban areas of Kenya. The Kenya Information Office: Nairobi. 1946. front cover.

Despite their proximity to Nairobi’s urban centre, all three estates were conceived as self-containing African communities on public land; a practice continued in the masterplan of 1948, made by the planners Thorton White, Anderson and sociologist Silberman.Footnote75 The provided variety of medical, educational and recreational facilities supposedly encouraged self-respect and collective values among Africans. At the same time, they ensured the community’s and individual’s physical and social welfare. The planned social hall, for example, was meant for educational and recreational activities (writing, reading, cinema shows).Footnote76 In Kaloleni, shops were even exclusively leased to African traders.Footnote77 Unlike canonical models such as Letchworth, individual gardens were not provided; instead, the one-storey blocks of semi-detached and terraced houses were grouped along open communal green spaces which would help to discourage ‘disorderliness and [..] maintain the urban and architectural unity of the neighbourhood as a whole’.Footnote78 Another ‘native’ touch consisted of an ‘informal’ clustering of homes: a materialization of the government’s belief that such ‘was preferred by the African’ and in line with his normal collective ‘mode of life’.Footnote79 The strict application of outdoor, communal sanitary blocks likely resulted from the same above-mentioned perception of the ‘native’ lifestyle; a long-lasting actor in Nairobi’s housing practices and formalized in the Feetham and AHC report (, ).

To reduce rents, AHC suggested a limited number of dwelling types for Ziwani, Starehe and Kaloleni, of which the basic elements could be mass-produced (, ). Consequently, the prevailing type was a family house consisting of one or two rooms, a cooking facility and a veranda. Houses were attached in small rows of two, three or four. A curtain separated living and sleeping in the one-room variant. Kaloleni differed from Ziwani and Starehe in one such housing design; one which was specifically designed to facilitate a rounded ending of the communal green spaces. This design is found alongside Kaloleni’s roundabouts and central oval (, ). To accommodate middle-income families, Ziwani and Kaloleni also had houses with two bedrooms, indoor sanitary facilities and front and/or back porches (, , ). Hutton, Fletcher and Dangerfield had to respect AHC’s guidelines regarding the application of interior kitchens, porches, tiled roofs, recognizable chimneys and a quasi-picturesque style which they expressed via the use of red, brown brick and white plaster as characteristic materials.Footnote80

Figure 8. Plan and elevation of two two-room dwellings, Kaloleni, 1943, A.J.S. Hutton. Source: G.W. Ogilvie, The Housing of Africans in the urban areas of Kenya. The Kenya Information Office: Nairobi. 1946. 17.

Figure 9. Plan and elevation of two one-room dwellings, Kaloleni, 1943, A.J.S. Hutton. Source: G.W. Ogilvie, The Housing of Africans in the urban areas of Kenya. The Kenya Information Office: Nairobi. 1946. 24.

Kaloleni was eventually realized between 1946 and 1948 without the planned prayer hall and rest house. Its social hall fulfilled the role of prayer hall and a primary school was built on the former rest house location.Footnote81 Actors behind this mutation could not be identified so far.

Kaloleni’s mutations after 1948

In 1948, Kaloleni was still viewed as ‘model village’, but only a few years later the garden city model was discarded by the team of South African planners that worked on Nairobi’s first master plan (1948). Though they considered Nairobi’s adaptation of the garden city model successful in promoting a sense of community, it was decidedly unpractical in the use of available land and in the realization of economical residential density; they preferred the ‘neighbourhood unit’ concept as basis for a new estate model.Footnote82

In the 1950s, shortly after the publication of Nairobi’s master plan and prompted by the continuing ‘native’ housing shortage, Nairobi Municipality decided to construct ten two-storey apartment blocks and five u-shaped groupings of four dwelling blocks in Kaloleni’s south-east corner (, ).Footnote83 Their roofing consisting of the same clay tiles as the original buildingsFootnote84 and the u-shaped dwelling block mirroring Kaloleni’s original housing typology; which differed only in having three instead of two windows in the front façade. It seems that Nairobi Municipality wished to mutate the original estate design as little as possible, despite pressing demographic growth () – from 108,990 inhabitants in 1944, to 118,796 in 1948 and 509,286 in 1969Footnote85 – and despite the master plan’s rejection of the garden city model.

Having identified the various actors at play in Kariakor’s and Kaloleni’s transmutation processes in the form of text, a comparison and visualization of these can now be made.

Comparing Kariakor and Kaloleni via actor-diagrams

To compare actors, this research makes use of actor-diagrams. A graphical representation of actors in actor-diagram enables their systematic, non-ideologically loaded categorization and visualizes their position in the supposed transmutation processes (, ). Following the ANT-method, the diagrams include pre-existing actors (settlement patterns, global as well as local housing and dwelling typologies, state reports) and actors of the period itself (design proposals, dwellers, architects, planners and functionaries).

Figure 11. Actor-diagram Kariakor estate, Nairobi, 1900–1929. Urban models/concepts are displayed with red rectangles, blue represents government/state actors, private companies are displayed with purple rectangles, orange shows dweller or dweller-related actors and yellow are demographic actors; the orange human figure represents ‘native’ Africans and the grey human figure, Asiatic, mostly Indian, people. The dark icons display the front façade of the housing units adopted in the estate. Source: Made by the authors.

Figure 12. Actor-diagram Kaloleni estate, Nairobi, 1929–1948. Urban models/concepts are displayed with red rectangles, blue represents government/state actors and demographic actors are displayed with yellow rectangles; the orange human figure represents ‘native’ Africans. The dark icons per estate display either the front façade of the housing units adopted in the estate or their floor plan. Source: Made by the authors.

Though similar actor-types played roles in Kariakor and Kaloleni, their characters and connections differ. Influential actors like the Feetham Report (1927) and the AHC report (1941) both resulted from an alarming population growth and the state’s involvement with decent housing for ‘native’ citizens, but ventilated different policies, being shaped by singular actors and networks. Notable actor differences are the Simpson report, Walton Jameson, Dutton and the African workers residing in Nairobi and the London Development Policies, Dangerfield, Hutton, Ziwani and Starehe for Kariakor and Kaloleni respectively.

Epilogue

This article set out to investigate if an ANT-related method enables an in-depth and non-ideologically-loaded historical reconstruction and comparison of the first ‘heydays’ of Nairobian public housing. Based on the above findings, we can state that it contributes to an empirical-based identification of main actors, actor-groups and their connections, whilst avoiding the traps of prevailing explanatory models, including (neo)Marxism and (post)colonialism, and of persistent dualisms like ‘global’ versus ‘local’. Precise categorization and comparison of actors prove to clarify the estates’ originations and their built forms and help to unravel the supposed transmutation processes at stake.

Categorization and comparison of actors can be made in the form of texts and by using diagrams. Actor-diagrams offer graphical exemplifications of actor-analyses done; they allow easy access and a visual image of research findings, also for academics in other disciplinary fields. Although the latter might interpret the diagrams from a different perspective and more extensively than we have done, the diagram’s factual data remains the same, ensuring that the actors involved in- and in part responsible for this neglected part of international town planning history can be communicated and made available for further academic reflection.

The here presented exploratory research note entailed at least two specific scholarly intentions for the current PhD-project Hybrid Artefacts: actors identified (University of Groningen, 2017–2021). The first is to further expand the actor-analysis by comparing Nairobi’s public housing estates to those of other Sub-Sahara African cities. The second intention will investigate the possibility to further detail the presented actor-reconstruction by identifying individual actors figuring in actor-groups like Public Works; as ‘native’ draftsmen and planners are rarely mentioned in official state documents of the time, their identification, if possible, will be done via the oral sourcing scheduled as part of the fieldwork in 2019 and 2020.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

A. M. Martin is an associate professor in History of modern Architecture and Urbanism, and researches international transfer of urban/typological models and concepts, and the surrounding discourse.

P. M. Bezemer is doing a PhD-project on a series of public housing estates from a comparative, historical perspective in four Sub-Saharan cities: Nairobi, Accra, Douala, and Libreville.

Notes

1 Harris, “From Trusteeship to development”; Beeckmans, Making the African City; Byerley, “Displacements.”

2 Latour, Reassembling the social; Weber, Living together, 18–41; De Boeck, Suturing the City, 18–22.

3 Hay and Harris, “Shauri ya Sera Kali”; Bigon, “Urban Planning, Colonial Doctrines”; Bigon and Katz, eds, Garden Cities; Myers, “Intellectual of Empire.”

4 Muchada, “Between Modernization and Identity”; Byerly, “Displacements”; Pellow, “New Spaces in Accra”; Ese, Uncovering the Urban Unknown; Schler, The strangers of New Bell; Liscombe, “Modernism in Late Imperial British West Africa”; Jackson, “Tropical Architecture”; Avermaete, “Crossing Cultures of Urbanism.”

5 Pieterse. Opening and welcome introduction.

6 Harris and Myers, “Hybrid Housing.”

7 Beeckmans, Making the African City.

8 Harris and Myers, “Hybrid Housing.”

9 Ogilvie, The Housing of Africans.

10 Acting Commissioner of Lands, Report Adabraka Settlement Scheme; Windham. Municipality of Accra; Martin, Bezemer. Estate analysis of Korle Gono.

11 George, “Building Sustainable Cities”; Cvetinovic et al., “Decoding Urban Development Dynamics.”

12 Munck, “Re-assembling the Actor-network Theory.”

13 Lecomte, “Beyond Indefinite Extension”; Munck, “Re-assembling the Actor-network Theory.”

14 Latour, Reassembling the Social.

15 Cvetinovic et al., “Decoding Urban Development Dynamics,” 142.

16 Munck, “Re-assembling the Actor-network Theory”; Müller and Schur, “Assemblage Thinking and Actor Network Theory.”

17 Yeoh, Contesting Space in Colonial Singapore.

18 Latour, Reassembling the social; De Boeck, Suturing the City.

19 Müller and Schur, “Assemblage Thinking and Actor Network Theory,” 217.

20 PhD-project Hybrid artefacts: actors identified.

21 Myers, Verandahs of Power.

22 Bigon and Katz, Garden cities.

23 Ojwang, Reading Migration and Culture, 20.

24 Memorandum Native Progress 1927, 2–4.

25 Demessie, “In the Shadow,” 445, 449, 454; Home, Of Planting and Planning, 93–115.

26 Thorton White et al., Nairobi Masterplan, 19–20.

27 Home, “Colonial Township Laws,” 179.

28 Home, Of Planting and Planning, 86.

29 East African Protectorate Nairobi; Kingoriah, Policy impacts, 116, 118–19.

30 Thorton-White et al., Nairobi Masterplan, 43; Harlow, History of East Africa, 210; Hake, African Metropolis, 43.

31 Thorton-White et al., Nairobi Masterplan, 4–9, 17–19; Huxley, Kenya today.

32 Harris, “From Trusteeship to Development,” 312; Myers, Verandahs of Power.

33 Kingoriah, Policy Impacts, 116, 118–19.

34 Blixen, Out of Africa, 11; Vasey, Report on African housing, 11, 37; Colony and Protectorate of Kenya, Some Aspect of the Development, 10–12.

35 Beeckmans, Making the African City, 51–4; “Sanitation and Disease,” 8; “Nairobi Sanitation. Risk of Epidemic,” 5; Cross, “Sanitary Reforms Urgently Needed,” 6.

36 Williams, Report on the Sanitation of Nairobi; Murunga, Inherently Unhygienic Race, 121–2; “The Case of Plague,” 6; “The Plague Remedy,” 7.

37 Gracey, Report by Colonel T. Gracey, 13.

38 Senior Medical Officer of Health and Municipal Natives Affairs Officer, On the housing of Africans, 7.

39 Acting Commissioner of Lands, Report Adabraka Settlement Scheme.

40 Colony and Protectorate Kenya, Legislative Council Debates, 537; Hake, African Metropolis, 44.

41 Nevanlinna, Interpreting Nairobi, 140–1; Hake, African Metropolis, 44–5.

42 Myers, Verandahs of Power, 35, 38, 39–41; Coetzer, Building Apartheid, 10–12.

43 Hake, African Metropolis, 43.

44 Harris, “From Trusteeship to Development,” 312.

45 Nat Amarteifo; Proteste der Duala-Hauptlinge.

46 Unwin, Parker, The Art of Building a Home; Unwin, Town Planning in Practice.

47 Hake, African Metropolis, 45.

48 Memorandum Native Progress 1927, 2–4.

49 Senior Medical Officer of Health and Municipal Natives Affairs Officer, On the housing of Africans, 1.

50 Ogilvie, The housing of Africans, 27.

51 Bigon, “Garden Cities in Colonial Africa,” 477–8; Beeckmans, Making the African City, 53–4, 102.

52 Senior Medical Officer of Health and Municipal Natives Affairs Officer, On the Housing of Africans.

53 Huxley, Kenya Today.

54 Senior Medical Officer of Health, Municipal Natives Affairs Officer, On the housing of Africans, 7.

55 Ibid.

56 Nairobi & District, Sheet NE14. B; Survey of Kenya, City of Nairobi (1950); Survey of Kenya, City of Nairobi (1962); Nairobi and Environs.

57 Survey of Kenya, City of Nairobi (1950).

58 Hardy, From Garden Cities, 81.

59 Unwin, Town Planning in Practice.

60 Colony and Protectorate of Kenya, Some aspect of the development, 10–12.

61 Senior Medical Officer of Health and Municipal Natives Affairs Officer, On the Housing of Africans, 2; Survey of Kenya, City of Nairobi (1962).

62 Ogilvie, The Housing of Africans, 27; Senior Medical Officer of Health and Municipal Natives Affairs Officer, On the Housing of Africans, 1–2, 5.

63 Harris, “From Trusteeship to Development,” 313.

64 Senior Medical Officer of Health and Municipal Natives Affairs Officer, On the Housing of Africans, 2.

65 Ibid., 3–4.

66 Ibid., 7.

67 Ibid., 5–7.

68 Northern Rhodesia Government, Ten-year Development Plan.

69 Nunes Silva, Urban Planning in Sub-Saharan Africa, 43.

70 Senior Medical Officer of Health and Municipal Natives Affairs Officer, On the Housing of Africans, 2–3, 7.

71 “Housing for Nairobi Africans.”

72 Plans & lay-outs Ziwani, Starehe, Kaloleni. Ogilvie, The Housing of Africans, 18, 30, 4.

73 City of Nairobi; Thorton White, Silberman, Anderson, Nairobi Masterplan, 64–65.

74 Ogilvie, The Housing of Africans, 19.

75 Ibid., 28.

76 Senior Medical Officer of Health and Municipal Natives Affairs Officer, On the Housing of Africans, 7.

77 “250,000 to be spent on Kariakor.”

78 “Housing for Nairobi Africans.”

79 Ogilvie, The Housing of Africans, 44.

80 Senior Medical Officer of Health and Municipal Natives Affairs Officer, On the Housing of Africans, 6.

81 Bezemer, Estate analysis Kaloleni (Nairobi); Plan and lay-out Kaloleni. Ogilvie, The Housing of Africans, frontpage; Nairobi & District, sheet NE 14 C.

82 Thorton White, Silberman, Anderson, Nairobi Masterplan, 46–67.

83 Plan and lay-out Kaloleni. Ogilvie, The Housing of Africans, frontpage; Nairobi & District, sheet NE 14 C.

84 Bezemer, Estate analysis Kaloleni (Nairobi).

85 Thorton White et al., Nairobi Masterplan, 43; Nairobi Urban Study Group, Nairobi Metropolitan Growth Strategy.

Bibliography

- Acting Commissioner of Lands. Report Adabraka Settlement Scheme. Accra: 1927, CSO12.2.16. PRAAD (Accra).

- Anonymous. Denkschrift ubder das enteigningsverfahsen – stellungsnahme des bezirksamtes Duala. 1913. R175-IV 474. Bundesarchiv (Berlin).

- Anonymous. “Eastlands Estates to be Demolished.” The Star (April 28, 2012).

- Anonymous. “Facelift to create jobs in Eastlands.” The Star (February 2, 2014).

- Anonymous. “Housing for Nairobi Africans. Details of the Makongeni Scheme.” East African Standard, January 4, 1944. Mcmillan Memorial Library (Nairobi).

- Anonymous. “Huddled Homes Anger People in Lusaka.” African Mail, January 24, 1961: 1. (RHO)756.18 t.2. Bodleian Libraries (Oxford).

- Anonymous. “Kibera may Reject Plan to rebuild.” East African Standard, January 20, 1960. Mcmillan Memorial Library (Nairobi).

- Anonymous. “£250.000 to be Spend on Kariakor.” East African Standard, February 4, 1963. Mcmillan Memorial Library (Nairobi).

- Anonymous. Memorandum Native Progress 1927. Nairobi: Government Printer, 1928. (RHO) 753.12 r.68. Bodleian Libraries (Oxford).

- Anonymous. Nairobi & District, sheet NE 14 C. Map. 1954. Kenya National Archives (Nairobi).

- Anonymous. “Nairobi Sanitation. Risk of Epidemic.” The Leader of British Africa (March 12, 1910): 5. C1742. British Library (London).

- Anonymous. “Nairobi’s Shanty Town is Coming Down Now.” East African Standard, August 4, 1948.

- Anonymous. Proteste der Duala-Hauptlinge gegen die Enteigung in Duala. 1913. R175-IV 493. Bundesarchiv (Berlin).

- Anonymous. “Sanitation and Disease.” The leader of British Africa (July 2, 1910): 8. C1742. British Library (London).

- Anonymous. “The Case of Plague.” The Leader of British Africa (May 20, 1911): 6. C1742. British Library (London).

- Anonymous. “The Plague Remedy.” The Leader of British Africa (June 3, 1911): 7. C1742. British Library (London).

- Avermaete, Tom. “Crossing Cultures of Urbanism: The Transnational Planning Ventures of Michel Ecochard.” In Crossing Boundaries, Transcultural Practices in Architecture and Urbanism. OASE 95, Journal for Architecture (2015): 22–33.

- Beeckmans, Luce. Making the African City. Dakar, Dar-es-Salaam, Kinshasa, 1920–1980. University of Groningen, 2014.

- Bezemer, Pauline Maartje. Estate Analysis Kaloleni (Nairobi). March–May, September 2014 (unpublished).

- Bezemer, Pauline Maartje. Interview Kaloleni residents (Nairobi). March–May, September 2014 (unpublished).

- Bezemer, Pauline Maartje. Working Paper PhD Project Hybrid Artefacts: Actors Identified (August 2018). University of Groningen, 2018 (unpublished).

- Bigon, L., and Y. Katz, eds., Garden Cities and Colonial Planning: Transnationality and Urban Ideas in Africa and Palestine. Manchester University Press, 2014.

- Bigon, Liora. “Garden Cities in Colonial Africa: A Note on Historiography.” Planning Perspectives 28, no. 3 (2012): 477–485.

- Bigon, Liora. “Urban Planning, Colonial Doctrines and Street Naming in French Dakar and British Lagos, c.1850–1930.” Urban History 36, no. 3 (2009): 426–448.

- Blixen, Karen. Out of Africa and Shadows on the Grass. 1988 (1st ed. 1937).

- Boeck, de F., and S. Baloji. Suturing the City. Living Together in Congo’s Urban Worlds. Autograph ABP, 2016.

- Bourriaud, Nicolas. The Radicant. New York: Lukas & Sternberg, 2009.

- Byerley, Andrew. “Displacements in the Name of (Re)Development: The Contesting Rise and Contested Demise of Colonial ‘African’ Housing Estates in Kampala and Jinja.” Planning Perspectives 28, no. 4 (2013): 547–570.

- Coetzer, Nicholas. Building Apartheid. On Architecture and Order in Imperial Cape Town. Ashgate, 2013.

- Colony and Protectorate Kenya. Legislative Council Debates, vol. II. Nairobi: Governor Printer, 1929.

- Colony and Protectorate of Kenya. Some Aspects of the Development of Kenya Government Services for the Benefit of Africans From 1946 Onwards. Nairobi: Governor Printer, 1953. JQ2947.KEN 1953. Bodleian Libraries (Oxford).

- Coquery-Vidrovitch, Catherine. “From Residential Segregation in African Urban Centres: City Planning and the Modalities of Change in Africa South of the Sahara.” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 32, no. 1 (2014): 1–12.

- Cross, J. H., and U.C.S. “Sanitary Reforms Urgently Needed.” The leader of British Africa (March 26, 1910): 6. C1742. British Library (London).

- Cvetinovic, M., Z. Nedovic-Budic, and J. Bolay. “Decoding Urban Development Dynamics Through Actor-network Methodological Approach.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 82 (2017): 141–157.

- Demessie, F. “In the Shadow of the Gold Mines: Migrancy and Mine Housing in South Africa.” Housing Studies 13 (1998): 445–469

- Director of Surveys. East Africa Protectorate. East African Protectorate Nairobi and Surrounding Country. Map. 1912. MAPS 66910.(4.). British Library (London).

- Ese, Anders. “Uncovering the Urban Unknown Mapping methods in popular settlements in Nairobi” PhD thesis, AHO, Oslo, 2014.

- George, Susse. “Building Sustainable Cities: Tools for Developing new Building Practices?” Global Networks 5, no. 3 (2015): 325–342.

- Gracey, T. Director of Railways, Report by Colonel T. Gracey, Correspondence respecting the Uganda Railway. London, 1901.

- Guggisberg, Frederick W. The Gold Coast: a review of the events of 1920–1926 and the prospects of 1927–1928. Gold Coast, 1927. (RHO) 722.13 r. 96. Bodleian Libraries (Oxford).

- Guguyu, Otiato. “Eastlands Residents Oppose Demolitions” (May 29, 2014). https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/corporate/Eastlands-residents-oppose-demolitions-/539550-2331142-qi8avxz/index.html.

- Hake, Andrew. African Metropolis. Nairobi Self-help City. London, 1977.

- Hardy, Dennis. From Garden Cities to New Towns: Campaigning for Town and Country Planning, 1899–1946. London: E&FN Spon, 1988.

- Harlow, V., and E. M. Cilver, eds. History of East Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1965.

- Hay, A., and R. Harris. “Shauri ya Sera Kali: The Colonial Regime of Urban Housing in Kenya to 1939.” Urban History 34 (2007): 504–530.

- Harris, Robert, and Andrew Garth Myers. “Hybrid Housing: Improvement and Control in Late Colonial Zanzibar.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 66, no. 4 (December 2007): 476–493.

- Harris, Robert. “From Trusteeship to Development: how Class and Gender Complicated Kenya's Housing Policy, 1939–1963.” Journal of Historical Geography 34 (2008): 311–337.

- Healy, P., and R. Upton. Crossing Borders, International Exchange and Planning Practices. New York: Routledge, 2010.

- Home, Robert. Of Planting and Planning: The Making of British Colonial Cities. London: Spon, 1997.

- Home, Robert. “From Barrack Compounds to the Single-family House: Planning Worker Housing in Colonial Natal and Northern Rhodesia.” Planning Perspectives 15 (2000): 327–347.

- Home, Robert. “Colonial Township Laws and Urban Governance in Kenya.” Journal of African Lawi 56, no. 2 (2012): 175–193.

- Huxley, Elspeth. Kenya Today. London: Lutterworth Press, 1954. (RHO) 753.11 r. 21. Bodleian Libraries (Oxford).

- Ioné Acquah, L. “Accra Survey: A Social Survey of the Capital of Ghana, formerly called the Gold Coast: undertaken for the West African Institute of social and economic research, 1953–1956.” University of London Press, 1958.

- Jackson, Ian. “'Tropical Architecture and the West Indies: From Military Advances and Tropical Medicine, to Robert Gardner-Medwin and the Networks of Tropical Modernism’.” Journal of Architecture 18, no. 2 (2013): 167–195.

- Kingoriah, George Kinoti. Policy Impacts on Urban Land-use Patterns in Nairobi, Kenya: 1899–1979. Indiana State University, 1980.

- Lagae, Johan. “Kulterman and After. On the Historiography of the 1950s and the 1960s’ Architecture in Africa.” L’Afrique c’est chic. Architecture and Planning in Africa 1950–1970, OASE-journal 82 (2010): 5–24.

- Latour, Bruno. Reassembling the Social: an Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Liscombe, R. W. “Modernism in Late Imperial British West Africa: The Work of Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, 1946–56.” Journal of Society of Architectural Historians 65, no. 2 (2006): 188–215.

- Lecomte, J. “Beyond Indefinite Extension: About Bruno Latour and Urban Space’.” Social Anthropology/Anthropologie Sociale 21, no. 4 (2013): 462–478.

- Martin, A. M., and P. M. Bezemer. Interview, Mr. Nat Amarteifo, former mayor of Accra and architecture, interview. March 2016, Accra.

- Martin, A. M., and P. M. Bezemer. Estate Analysis of Korle Gono, South La, Christiansborg, Victoriaborg, Kokomlemle, Labone, Kaneshie (March 2016, Accra).

- Muchada, A. “Between Modernization and Identity: Colonial Social Housing as a Specific Theoretico-Practical Corpus of Colonial Architecture – the Case of Tetouan (Morocco, 1912–1956).” Planning Perspectives (2018): 1–20.

- Myers, Garth Andrew. “Intellectual of Empire: Eric Dutton and Hegemony in British Africa.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 88, no. 1 (March 1998): 1–27.

- Myers, Garth Andrew. Verandahs of Power: Colonialism and Space in Urban Africa. Syracuse University Press, 2003.

- Müller, M., and C. Schur. “Assemblage Thinking and Actor Network Theory: Conjunctions, Disjunctions, Cross-Fertilizations.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 41, no. 3 (July 2016): 217–229.

- Munck, de Bert. “Re-assembling the Actor-Network Theory and Urban History.” Urban History 44, no. 1 (2017): 111–122.

- Muiruri, Peter. “Residents Worried as Court Allows Demolition of Nairobi’s Oldest Estates.” (June 1, 2018). https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/article/2001282551/residents-worried-as-court-allows-demolition-of-nairobi-s-oldest-estates.

- Murunga, Godwin Rapando. “‘Inherently unhygienic races. Plagues and the origins of settlers’ dominance in Nairobi, 1899–1917.” African Urban Spaces in Historical Perspective. University of Rochester Press, 2005.

- Nasr, J., and M. Vollait, eds. Urbanism: Imported or Exported? Native aspirations and foreign plans. Chichester: Wiley, 2003.

- Nevanlinna, Anja Kervanto. Interpreting Nairobi. The cultural study of built forms. Helsinki, 1996.

- Njoh, Ambe. Planning Power: Town Planning and Social Control in Colonial Africa. UCL Press, 2006.

- Northern Rhodesia Government. Ten-year Development Plan for Northern Rhodesia. Lusaka: Government Printer, 1947. HC16.Z33.NOR 1947. Bodleian Libraries (Oxford).

- Nunes Silva, Carlos, ed. Urban Planning in Sub-Saharan Africa. Colonial and post-colonial culture. London: Routledge, 2015.

- Ogilvie, G. C. W. The Housing of Africans in the Urban Areas of Kenya. Nairobi: Kenya, Information Office, 1946. Kenya National Archives (Nairobi). (RHO) 753.12 r. 79. Bodleian Libraries (Oxford).

- Ojwang, Dan. Reading Migration and Culture: The World of East African Indian Literature. Palgrave Macmillian, 2013.

- Pellow, Deborah. “New Spaces in Accra: Transnational Houses.” City & Society 15, no. 1 (2008): 59–86.

- Perry, Clarence. “The Neighborhood Unit: A Scheme of Arrangement for the Family Life Community.” Regional Plan of New York 7 (1929).

- Pieterse, Edgar. “Opening and Welcome Introduction.” African Centre for Cities International Urban Conference, February 1–3 (Cape Town: 2018).

- Schler, Lynn. The Strangers of New Bell: Immigration, Public Space and Community in New Bell, Cameroon, 1914–1960. UNISA Press, 2008.

- Senior Medical Officer of Health and Municipal Natives Affairs Officer. On the housing of Africans in Nairobi, with Suggestions for Improvements (Nairobi: April 30 1941). (RHO) 753.12 r. 33 (26). Bodleian Libraries (Oxford).

- Survey of Kenya. City of Nairobi. Map. Nairobi: Government Printer 1950. 66910.(40). British Library (London).

- Survey of Kenya. City of Nairobi. Map. Nairobi: Government Printer 1962. 66917.(1.). British Library (London).

- Survey of Kenya. Nairobi and Environs. Map. Kenya Government, 1978. maps x.2601. British Library (London).

- Tait, M., and O. B. Jensen. “Travelling Ideas, Power and Place: The Cases of Urban Villages and Business Improvement Districts.” International Planning Studies 12, no. 2 (2007): 107–128.

- Thorton White, L. W., L. Silberman, and P. R. Anderson. Nairobi Masterplan for a Colonial Capital: A Report Prepared for the Municipal Council of Nairobi. London, 1948.

- Unwin, R., and B. Parker. The Art of Building a Home, a collection of lectures and illustrations by Barry Parker and Raymond Unwin. London: Longmans, 1901.

- Unwin, Raymond. Town planning in practice, the art of designing cities and suburbs. 2nd ed. Benjamin Blom Inc., 1971.

- Vasey, E. A. Report on African Housing in Townships and Trading Centers. Nairobi, 1950.

- Weber, Elisabeth, ed. Living Together: Jacques Derrida’s Communities of Violent and Peace, 18–41. Fordham University Press, 2012.

- Williams, G. R. Report on the Sanitation of Nairobi, and Report on the Townships of Naivasha, Nakuru and Kisumu. London: Waterlow, 1907.

- Windham, W. F. Officer in charge of Cadastral Branch. Municipality of Accra. Map. Cadastral Branch Gold Coast: 1929. E34: 20 (22). Bodleian Libraries (Oxford).

- Yeoh, Brenda S. A. Contesting Space in Colonial Singapore: Power Relations and the Urban Environment. NUS Press Pte Ltd, 2013.

- Zeleza, Tiyambe. “The Colonial Labour System in Kenya.” An Economic History of Kenya. East African Educational Publishers Ltd., 1992.