ABSTRACT

The arrival of the third plague pandemic in the Indian Subcontinent in the late nineteenth century is well known to have prompted the state to rethink colonial governance. In this article, I examine how a locality in Bangalore, Fraser Town, was turned into a ‘model town’ at the All-India Sanitary Conferences hosted between 1911-1914, in the aftermath of the plague. I juxtapose archival manuals that recount the planning of Fraser Town with the discussions on town planning in the AISC proceedings to show how a universal ‘plague urbanism’ emerged as the most effective prophylactic against disease across Imperial India. The colonial government’s intent to project Fraser Town as an exemplar of sanitary planning at the AISC, I argue, had a twofold agenda. In Bangalore, they could claim credit for creating a model town although it was the Princely Mysore State’s capital. Across Imperial India, Fraser Town supported the Conferences’ agenda of deconstructing the difference between British, Princely, and variously ruled territories, reconstituting them in a performatively united ‘All-India’ against disease. Putting the making of Fraser Town alongside the imperial AISC, in dialogue with a global pandemic and conferencing; I show how planning processes were integral to territorial aspirations of empire.

Introduction

On the 11th of August 1898, an indisposed coolie or servant of an employee of the Madras and Southern Maratha (MSM) Railway came into contact with his master. Along with a fever, the symptoms found by the inspecting doctor are likely to have constituted swollen lymph nodes or buboes on his body as they were identified by him as indicators of bubonic plague.Footnote1 Fearing its spread, he was driven to a segregation camp by his master, where he died three days later and unknowingly became the first recorded case of the Third Plague Pandemic in Bangalore’s Civil and Military Station (C & M Station). The plague had originated in Southwest China in the mid-nineteenth century arriving in Bombay via maritime routes in 1896.Footnote2 It is from Bombay that the coolie working at the MSM railways goods sheds was suspected to have carried it to Bangalore.

Bangalore’s C & M Station (where the plague first arrived) was reliant on the other half of the city, the Princely controlled ‘native’ Pettah or Bangalore City. So much so that it was well known even then that ‘one [half] would not be spared of the plague if the other were attacked by the plague’ ().Footnote3 As expected, two children living near the railway sheds in Bangalore City were also found to have died of a fever. A visit to disinfect the house they inhabited confirmed that other members of the family had shown symptoms of the plague as well as the presence of the main suspected cause: dead rats. A report on the outbreak of the plague a year after its arrival in Bangalore confirmed these causes, identifying the railway coolies and rats as agents of the plague.Footnote4

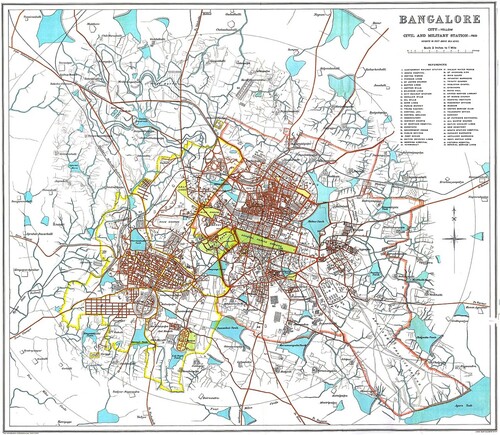

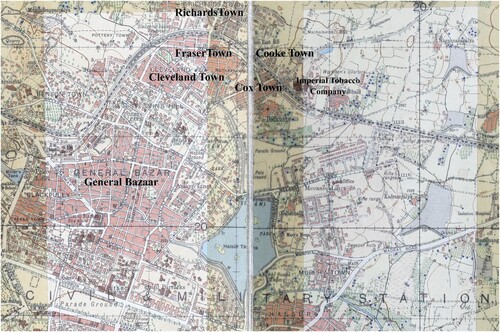

Figure 1. Bangalore in the late nineteenth century. The parkland, Cubbon Park separates the Pettah or Bangalore city on the left from the Cantonment that became the C & M Station. Source: John Bartholomew, available in the Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Localized plague precautions – close surveillance, isolation, disinfection of suspect carriers – immediately commenced in the British controlled C & M Station.Footnote5 The same however did not extend to those living in the Princely State-controlled Bangalore City, subject to asymmetrical resource allocation.Footnote6 Overall over 205,422 victims died from the plague across the Mysore state and the deaths in Bangalore contributed substantially to this figure.Footnote7 Even before the plague’s arrival, the colonial government had relocated its administration from Mysore city (the capital of the Princely State of Mysore) to Bangalore in 1809 and both operated as capital cities.Footnote8 First a military encampment, it developed into a cantonment and became the Civil and Military Station (1868). The Station part of ‘British India’ was actively separated from the Princely controlled Bangalore City by a vast tract of parkland ‘Cubbon Park’ (green in ).Footnote9 Both portions were administered by two separate boards but despite a shared municipal commissioner, the C & M station was consistently pitted against Bangalore city as better developed.Footnote10

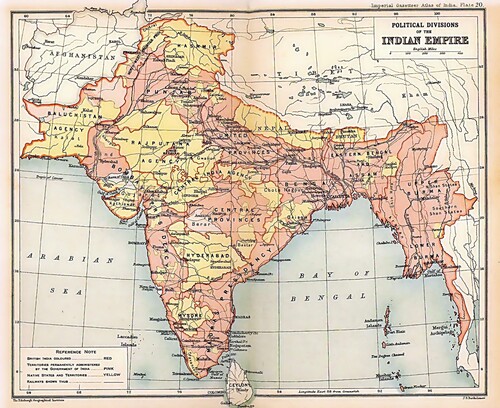

Unlike territories under a more uniformly imposed direct rule (at least in writing), Princely States such as Mysore were monarchies subordinated to the colonial power or subject to ‘indirect’ rule. As territories with delineated frontiers situated within the Empire of India, they were more or less internally sovereign. Their princes negotiated and tailored their relationship to Britain through myriad bespoke treaties, engagements and concessions.Footnote11 Integral to Imperial India, but constructed as ‘peripheral’ to imperial governance, these five hundred and sixty-two such Princely States occupied nearly two-fifths of the area of the Empire of India (denoted with yellow in ), governing nearly 35% of its population.Footnote12 Of these, the State of Mysore was one of the largest in area and population, and its leaders carefully cultivated the title of a ‘model’ state.Footnote13 Bangalore as one of the Mysore State’s capitals (the other Mysore city) was in a unique situation, as a city where directly ruled British India’s territories (the C&M Station) met with those of Princely India (Bangalore city).

Figure 2. Yellow indicates the native Indian states or princely states in contrast to pink which represents territories of British India, territories that were permanently administered by the GOI as of 1909. Source: Available in the Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

As in Bangalore, the Third Plague Pandemic disregarded territorial borders, travelling across variously governed territories, spreading from Bombay to the North-Western Provinces, and moving South to firmly establish itself across the sub-continent. In response, the colonial government invoked a ‘state of exception’ expanding its extra-legal powers while maintaining that these were one-off and temporary measures to tackle the emergency.Footnote14 It enacted the Epidemic Diseases Act of 1897, the largest intervention in the everyday lives of Indians. The Act permitted the suspension of existing law to allow the state any state intervention deemed necessary in any given area or time to prevent the spread of disease when determined by biomedical discourse.Footnote15

The commitment to implementing far-reaching measures was surprising, given the Government of India’s (GOI) previous reluctance to provoke public opposition and its unwillingness to spend more than was necessary on public health.Footnote16 With superficial knowledge of the mechanism of disease transmission that assumed person-to-person contagion, the body of the colonial subject became an increasingly politicized terrain.

Scholars of South Asia and elsewhere have extensively described the plague as a moment in colonial history where discourses of health, sanitation, and physical violence were intimately bound with the colonial government feeling its own authority under scrutiny.Footnote17 The responses to the plague, therefore, became the site to reconstitute its legitimacy. In this way, the ‘exception’ or the state of exception was fundamental to its functioning.Footnote18 Presented as temporary interventions, they extended beyond the plague or remained permanently, to the extent that the 1897 Act was invoked at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote19 Scholars have therefore referenced the third plague pandemic and the extraordinary interventions it occasioned while discussing the contemporary pandemic and the enduring long-standing structural inequalities that exacerbated its spread.Footnote20

Like other urban histories, I am interested in how the focus of governmental attention shifted from the body to the ‘insanitary and congested’ dwellings and neighbourhoods to replace them with ‘sanitary’ housing.Footnote21 The colonies had already been locations par excellence where the rule of law could be suspended and altered or made anew in the service of ‘civilization’. Drawing on spurious ‘scientific’ arguments that identified some segments of the population as sanitary threats (specifically those from marginalized caste and class groups) institutions were restructured or made anew to regulate urban spaces and remedy them and their new neighbourhoods through town planning.Footnote22 While spatial and temporal location varied, the desire was planning as a prophylactic against disease in its largest sense. I term these responses ‘plague urbanism’ – a much-feted unanimous solution presented to tackle a common set of problems presented by the plague.

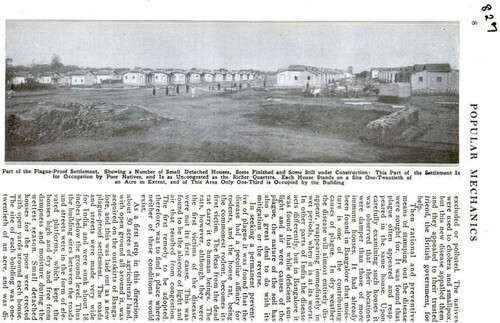

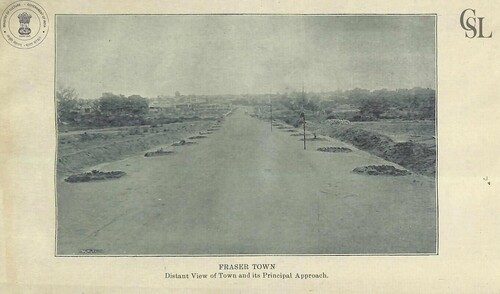

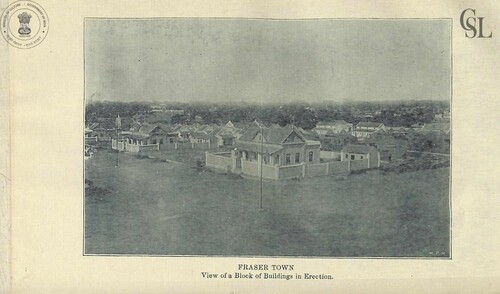

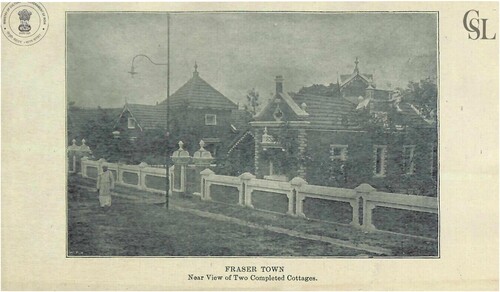

This paper focuses on one such perceived ‘success’ story of plague urbanism, Fraser Town, a housing scheme in Bangalore constructed between 1908 and 1910. With a material focus, I demonstrate how five rules were developed to make Fraser Town ‘plague proof’ and how the bungalow – surrounded by setbacks – was deployed as a sanitary house for replication (). Designed and carried out by Municipal Engineer, J.H. Stephens, the whole object of the development was ‘to elevate common people and accustom them to a newer and more “healthy manner of living” without adding materially to the cost of the house’.Footnote23 Spurious knowledge of what was unhealthy as opposed to healthy living and pseudoscientific understanding of the transmission of plague were channelled to design Fraser Town under the guise of rational British Planning.

Figure 3. View of the replicated bungalow with setbacks in Fraser town. Source: Popular Mechanics Magazine.

What is perhaps most interesting about Fraser Town, however, was that it was used as an exemplar ‘model town’ of plague urbanism. It was also constructed as such at a series of All India Sanitary Conferences (AISC) held between 1911 and 1914. These conferences were amongst a profusion of scientific meetings across the first half of the twentieth century designed to solve logistical, technical, or epidemiological problems. But they were unique in that they were the first of their kind ‘All-India’ platform across British and princely territories. It is here that the Government of India (GOI) brought together states that were often constructed as ‘peripheral’ to British India to discuss a shared set of problems of infectious diseases and remedial measures to combat them.Footnote24 Until the Conferences, the focus of such measures had been limited to writing about them within state boundaries even if they were against the same common enemy of disease. It was at the inaugural AISC in 1911 that the President, Harcourt Butler would draw attention to Fraser Town in a broader relationship to disease and sanitation across India through his introductory speech:

I would like to bring specially to your notice the good results obtained in Fraser Town, Bangalore, which still continues plague-proof. And I would ask – Is it an impracticable dream to construct a model town or quarter of a town in each province, with good water supply, efficient drain, rat-roof and mosquito proof houses and an adequate sanitary staff as a measure of demonstration and education?Footnote25

Interested in exploring why Fraser Town – this small development in Bangalore – received much attention at an All-India level, this paper takes a global history approach to offer a geography of interconnectedness to break nationalist and globalization historiographies through the AISC.Footnote27 I juxtapose the scrupulous attention paid to the planning of Fraser Town using an archival manual written by its planner, J.H. Stephens with the deliberations on town planning across the multi-volume proceedings of the three AISCs published by the GOI. Planning was central to spatial and territorial concerns of the empire but extensive scholarship on planning in colonial India has been focused on the so-called ‘centres’ of Presidency Capital cities such as Bombay, Delhi and Calcutta.Footnote28 Both Stephens’ book that offers a first-hand account of planning Fraser Town in Bangalore and the multi-volume proceeding of the AISC are unique in offering accounts of planning in princely cities which have previously been treated as ‘peripheral’ by planning scholarship. Bringing these two unique historical sources with very different and overlapping pedagogical goals enables me to approach Fraser town with translocality beyond the local, neither in the global scale nor global moments to reveal a shift in both planning discourses and governmentality across Imperial India.Footnote29

While the influence of Fraser Town on colonial town planning has limits for understanding universal plague urbanism, exploring why and how Fraser Town was planned as a technocratic model for replication in Bangalore and Imperial India allows me to make two arguments. In Bangalore, I show how the GOI was able to blur City and Station limits by discursively appropriating Fraser town at the AISC. This allowed the GOI to participate in the discourse of having created a ‘model town’ in a state under Princely rule (Mysore). Across Imperial India to the Conferences, the GOI was able to extend the same distortion of boundaries in Bangalore to blur the difference between British, Princely, and other territories and reconstitute them in a markedly united ‘All-India’ against the disease. These two arguments underwrite the limited planning scholarship that shows that this discipline’s formation was another cultural technique of colonialism for the better management of colonial subjects.Footnote30

This paper is structured into three sections. The first section draws attention to the experience of the plague in Bangalore and the responses to it. This contributes to our understanding of the experience of the Pandemic in the Mysore state, whose death rate was only exceeded by Punjab, the Bombay Presidency, and the United Provinces connecting.Footnote31 Connecting it to scholarship urbanism in Imperial India, it then focuses on the Fraser town, its planning, the five rules deployed to make it plague proof and the resulting responses to its deployment. In the second section, I approach the AISC as a space for knowledge production to focus on the discussions on town planning. Through a close examination of the proceedings, I show how British planning was promoted by administrators as solutions for both sanitation and new governmentality. The last section provides a broader discussion beyond Mysore, centring one of the few historical moments where delegations from the Princely States were brought together with those from British India at a technical conference. Highlighting the representation of various delegations from across Imperial India, I show the conference as a political site and discuss what it means that Mysore was present at them.Footnote32 Together this paper contends that British planning cannot be understood as forms of progressive technical practice but instead must be evaluated as colonial modes of territorial expansion.

Making Bangalore a sanitary city through plague proofing

The removal of ‘congested’ settlements by dispossession and replacement with new housing schemes in Bangalore began before the onset of the plague in the city. Divided between Princely and British jurisdictions, both Bangalore City and the C & M Station had separate independent Municipal Boards. Many smaller bodies such as the Plague Establishment or Department in 1897 instituted in response to the plague outbreak or the Bangalore City Improvement Committee in 1889 engaged in clearances and demolitions to relieve what they termed ‘congestion’ and were eventually absorbed by Bangalore Municipality.Footnote33 With little known about the cause and spread of the plague, these congested localities with recorded cases easily came to be seen as ‘symptoms’ and often causes of disease.

Prashant Kidambi has shown in colonial Bombay, how the plague was framed as a ‘disease of locality’ meaning that the infection was stubbornly believed to stem from in situ and cultural pollution in dwellings and neighbourhoods.Footnote34 Pathologisation of the plague in slums is not dissimilar to that of blight in various industrial cities in America where the ‘locality’ rather than the condition was the focus of Governmental attention.Footnote35 This framing of disease through locality has impelled scholars to focus on the colonial state’s offensive against the urban environment where slum removal was dubbed congestion removal. The Bombay Improvement Trust formed in 1898, was followed in quick succession by the Mysore City Improvement Trust (MCTIB) in 1903 and the Bangalore City Improvement Trust Board (CITB) in 1904.Footnote36 The land from clearances of congestion provided a valuable resource for ‘improvement’ through urban planning and real estate development.Footnote37 New renewal schemes for housing such as Chamarajepete in 1894 were already being realized before Bangalore City Improvement Committee and Municipality were set up.Footnote38 The existence of such urban renewal projects before the plague betrays that demolition and dispossession were treated as both legitimate and necessary for making urban property valuable before they were cast as ‘sanitary’ projects.

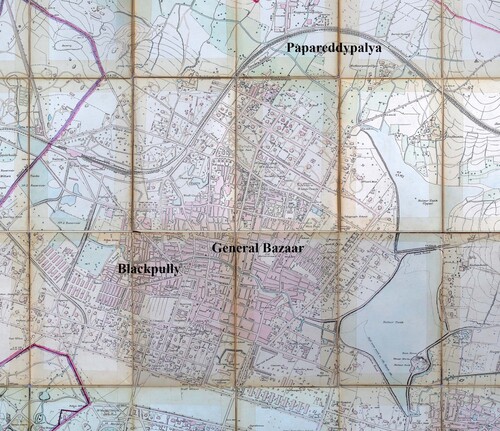

The most thickly populated in the C & M Station, Blackpully, was where municipal officials were greatly concerned about the spread of the plague.Footnote39 It had been infamously recorded in colonial accounts for the incidences of Malaria and Cholera.Footnote40 Housing close to a seventh of the population of the Station with 1952 houses and over 12,000 inhabitants, many of its residents provided cheap labour and services to the stationed British officers and officials.Footnote41 As Aditya Ramesh illustrates, it was no surprise that the locality was selected for demolition and improvement.Footnote42 Perhaps the most ironic part of this process was the expelling of people from pockets of inequality that the C & M Station itself had produced.Footnote43 Main thoroughfares were avoided, and new roads were opened through ‘the heart of the filthiest and most unsanitary slums’ to dramatically reduce the population density.Footnote44

Such sweeping clearances were condemned not just by residents and those displaced, but also by other British planners like Patrick Geddes. He heavily criticized the demolition activities of the sanitarians calling them ‘the most disastrous and pernicious blunders in the chequered history of sanitation’.Footnote45 Nevertheless, these sanitary measures were justified through the Health Department’s statistical tables that recorded an improvement in the death rate in Blackpully and the C & M Station with other objective ‘scientific’ data.Footnote46 But the intent of alleviating conditions in cities by erecting housing was not to tackle living standards, but rather, to limit the contagion from spreading to European and caste elites in Bangalore just as elsewhere.Footnote47 As a report describing circumstances around the plague in Bangalore in the C & M explicitly stated:

The English soldier cannot be always tied down to the Barracks. He will have to walk about sometimes and often this takes him into the native portions of the town. Also, the Indian servants to the English people live in these parts and carry contagion with them into the English homes of Bangalore. It was seen that no scheme for the permanent improvement of the health of Bangalore could be successful without giving the Indian sections of the town some consideration.Footnote48

Planning for plague prevention in Fraser Town

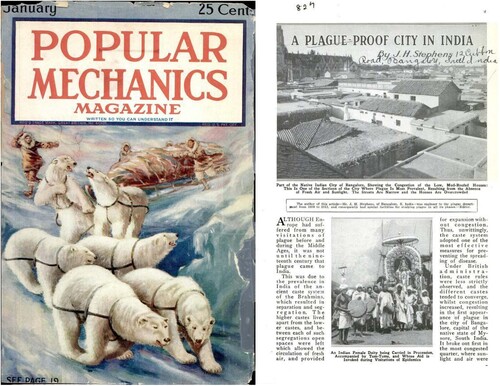

A range of historians have shown how native subjects were construed as ‘irreducibly different’ from their European counterparts.Footnote51 With the preconceived idea that ‘native’ living habits helped disease thrive, J.H. Stephens aimed to lay a plague-proof locality that would alter the ‘general conditions of Indian living’.Footnote52 An RIBA licentiate, Stephens was the Municipal Engineer to the Bangalore Corporation and Special Plague Department between 1898 and 1912. Before his employment in the C & M Station, he had practised under the Public Works Department of the Government of Madras. A significant part of his time was spent working in the districts experiencing floods and famines. Perhaps these experiences contributed to him being chosen to plan this model town. Moreover, planning provided a terrain for colonialism to be promoted as technical assistance rather than imposition, even with practitioners who had little personal knowledge of cities and local situations.Footnote53 Stephens did not lose sight of the opportunity to design Fraser Town as a career-making step. His active promotion of assistance went far beyond official publications as in magazines such as Popular Mechanics (see for the cover of Popular Mechanics and article of Fraser Town in it).

Figure 4. Cover of popular mechanics magazine and a full page on Fraser town. Source: Popular Mechanics Magazine.

Claiming to provide accommodation for the displaced people in Blackpully and to encourage migration from congested areas, a tract of arable land (measuring 50.35 acres) situated to the north of the Station was acquired in Papareddipalya, Dodagunta village, to plan Fraser Town ().Footnote54 The land was bounded by the curving railway line on north-western, northern, and north-eastern perimeters, Promenade Road, and Cleveland Town an older suburb in the south, and on the east by Wheeler Road. Initially referred to as the Blackpully Extension Scheme or Northern Extension, it was eventually named after Stuart M. Fraser, of the Indian Civil Service, tutor, and guardian to the Maharaja of Mysore, who had supported the extension.Footnote55

Figure 5. Shows the land acquired in Papareddipalya in relation to the C & M Station’s General Bazaar. Source: Cantonment and City of Bangalore and Environs Season 1884-85. Map Courtesy: The Mythic Society Bangalore Photo: Authors Own.

Fraser Town’s 470 plots, each measuring 66’ × 33’ made the individuals who lived in them suddenly ‘visible’ by assigning or localizing each house with a widely accepted address and conferring legitimacy based on the type of tenurial arrangements. Legitimacy from the municipality was granted by the provision of facilities such as sewage lines, water, electricity, and roadways but also through design and the materials used to construct it.Footnote56 Simultaneously, the Anglo-European ideal of middle-class domesticity elevated the status of the properly ordered home to be a powerful device of reform, one that could mould and reshape ‘native’ habits and customs once imposed on the local population.Footnote57

If the intent had been to ‘elevate the common people and to accustom them to a newer and more healthy manner of living without adding materially to the cost of the house’Footnote58 it quickly transformed into an ideal settlement for Europeans, members of the domiciled European community and for well-to-do Indians.Footnote59 The bourgeois ideal of domestic comfort to bring both, moral and sanitary reform was seldom fully realized in the ordinary colonial subject. Such attempts to provide infrastructure, modernize institutions of governance and reorder material resources were technologies of regularization to make governable objects.Footnote60 The making of a township with model homes as a tool for replication would invariably mean the value of collectable taxes that were determined by the type of occupancy, holding, facilities, dwelling and materials used.

Experiments in plague-proofing

When Stephens was entrusted to plan Fraser Town, the disease carried by the coolie and rats had been demystified and the microbial cause of the plague was identified, Yersinia pestis-the rat flea.Footnote61 Unconvinced by these new developments and instead relying on his observations of working with the plague-stricken, their homes and surroundings, Stephen would highlight the soil as a breeding ground with periods of dormancy and attenuation:

the little rodent and the flea are victims and channels of communication of the plague to man, but they are not the primal cause of the plague and the plague life. This [the contagion] is formed in the soil, and travels in it and in the air immediately above it.Footnote62

As the disease was treated as miasmatic contagious, that which arises from the soil and surroundings, the first rule was to tackle the material qualities of the soil. To avoid stagnation in ‘low, undrained, over-crowded, native quarters, the land around the plot was to be excavated below the ground level. All principal roads in Fraser Town were also to be lower than the plots themselves. Foot-wide drains were placed on each side of the road at a lower depth (). This was all to ensure that the building plots became elevated platforms and allowed rainwater to flow down to the lower roads and drains.Footnote64 To further keep the ground and area around the house dry, the second rule insisted that all basement walls be made of stone and raised to a height of 1ft. A local granite in Bangalore was used and joints were pointed with good cement. The third rule prescribed that all the flooring be of stone slabs, tiles, or any other hard material to prevent rats and other vermin from burrowing.Footnote65

Figure 6. Principal roads were sunk below ground level and drains placed. Source: Stephens, J. H. (1914). Plague-Proof Town Planning in Bangalore, South India. Madras: Methodist Publishing House. Source: The British Library.

Convinced by examples of severe outbreaks of the plague which had spread along with contiguous houses but not to those across the street, it was ascertained by officers of the Plague Establishment that the plague microbe or miasma followed the line of least resistance when houses abutted each other. The fourth rule aimed at providing ‘general sanitary improvement’ by ordering that only a quarter of the area of the plot be built on, leaving three quarters as the open area surrounding the house. With an assumption that land in Bangalore was cheap, Stephens declared that having open ground surrounding the house would not increase the cost of a house. Sub-diving land into two types of plots, one-acre plots further sub-divided into 20 building sites with ‘small houses’ of 2178 sq. feet for the ‘poorer classes of people’ and one-acre plots further sub-divided into 10 parts each measuring 4356 sq. feet for those ‘a little better off’ ones ( and ).Footnote66 In reasoning for a house with setbacks, the spatial logic of a bungalow, as a detached house within a compound was introduced. Four hundred bungalows were built in Fraser Town.Footnote67

Figure 7. Smaller houses showing where the plot to the built ratio (4:1). Source: Stephens, J. H. (1914). Plague-Proof Town Planning in Bangalore, South India. Madras: Methodist Publishing House. Source: The British Library.

Figure 8. Larger houses dubbed ‘cottages’. Source: Stephens, J. H. (1914). Plague-Proof Town Planning in Bangalore, South India. Madras: Methodist Publishing. Source: The British Library.

Stephens’ fifth and last plague-proof rule recommended that all roofs be covered with Mangalore tiles. Made popular by the Basel Mission’s Tile Factory in Mangalore, these were interlocking clay tiles supported by a roof made of rafters and horizontal purlins.Footnote68 Despite a potters’ village near Fraser Town that produced country tiles cheaply, the more expensive Mangalore tile was insisted on by him and every house in Fraser Town is roofed with it. When describing the reasons for intervention in Blackpully, he and other sanitarians argued that the plague was a disease in situ because of dark and ill-ventilated houses. To ventilate the new build houses even when windows were shut, he pushed for a roofing system of Mangalore tiles supported by other structural members. Amidst complaints of the tiling causing jaw ache because of the cold, Stephens maintained they were doing their ‘proper work’ in the way of ventilation.Footnote69 Privileging material specifications such as manufactured tiles as ‘pakkā’ or solid would make these building materials taxable. In doing so, other materials that involved traditional construction processes like thatch would get deemed as makeshift constructions or ‘kacchā’.Footnote70 Materials and design were no different from the larger attempts of the state to make legible categories to impose taxation and control.Footnote71 Together these five rules produced the bungalow as a sanitary ‘model dwelling’ with setbacks, and regulated building materials as quintessentially a ‘plague proof’ house suited for replication in planned suburbs.

Stephens effectively treated Fraser Town as a career-making ‘laboratory’ to change the way native inhabitants used space. Taking the example of European-occupied detached houses in the city he disputed the suitability of traditional dwellings such as the traditional Mysore regional house-type, totti mane. Inhabited by multi-generational families and arranged around a central courtyard, totti manes were suited to both climate and privacy needs.Footnote72 He wrote critically of the living conditions that he described as ‘huddled together’ thinking that the logic behind such an arrangement was for their safety and that of their property.Footnote73 That these closely structured arrangements were functional not only in terms of securing protection but also expressed the basic economic and social relations of its inhabitants, did not seem to feature in his understanding of them. He continued the colonial civilizing logic of utilitarianism parallel to prevalent ideas of Anglo – European domesticity to show how Fraser Town taught ‘poorer’ classes of people that they could live safely and securely apart from each other.Footnote74

Living in the model town: challenges & contradictions

Inhabitants of the new, plague-proof city though, did not always conform to his plans. Ever the propagandist of the powerful impact of alterations made in Fraser Town, Stephens proudly noted that in addition to being a plague-proof town it was also a ‘health resort’ where those with various diseases had returned to ‘health and vigour’.Footnote75 He portrayed the inhabitants as readily accepting plague-proof rules that were foisted upon them by dogmatic colonial officials and municipal engineers, architects, and planners like him.

Despite Stephen’s proclamations, his own book reveals that the inhabitants negotiated and subverted the rules he had proposed. For example, the third rule regarding floor finishes of the houses be made of a hard material was not always adhered to. Despite the municipality concluding that the plague microbe would still be carried via cow dung, orthodox Hindus preferred to sanitize the floor by smearing it. Begrudgingly, Stephens wrote that many continued to use the traditional method and only 75% of the houses in Fraser town used stone, tile, and cement. The inhabitants of Fraser Town also wished to erect bazaars in some plots instead of using the locality exclusively for housing. This desire was frowned upon by the C & M station Executive Board which wished to confine all commercial activity in one location. While insisting on material finishes of flooring and skirting in each of these establishments, the Board yielded to residents’ requests allowing bazaars on every street. Such accounts of defiance and negotiation through use, meaning, and materials of the built form destabilize the singular authority that Stephens intended in its design and its reception.

Further, despite Stephens’ portrayal of the quick uptake of land and housing, not everyone was keen on building or living on what had until recently been primarily agricultural land (Raggi fields). Located on the outskirts of the city, Fraser Town was 1 ½ mile from the General Market and commercial enterprises. It was on the way to the Hindu cemetery around which Hindus refused to move as ‘to live there would be to go halfway on the road to the cemetery, that is on the road to death’.Footnote76 A garbage dump was located not far from the site, and odours from it were said to have wafted right over Fraser Town, making it further undesirable.

The fundamental reason Fraser Town did see ‘success’ in the eyes of both local government and the GOI was because of the C & M Station’s Municipal Board and The British Resident, Colonel Robertson's heavy hand in ensuring it. In other extensions in Bangalore City, state-led housing had meant the allotment of plots, providing drainage, sewerage, and basic amenities but not the construction of houses themselves.Footnote77 In Fraser Town, however, financial assistance was granted by the GOI (on request of the Municipal Board) to begin demolition and clearances in Blackpully and incentivise investors such as Mr B.P Rao Bahadur Annaswami Mudaliar, and Khan Bahadur Hajee Ismail Sait to build speculative housing.Footnote78

Investors were encouraged to build housing and adhere to the plague-proof rules in Fraser Town by benefitting from other contracts and associations with the colonial government and just by rents. Sait and Mudaliar set up an elementary school, a public dispensary, and public markets and contributed to the construction of a mosque, to attract residents. In addition, the Station’s Municipal Board funded a tramway scheme and incentivised manufacturers (Peninsular Tobacco Company of Monghyr) to enhance land values in the areas surrounding Fraser Town. Be it new amenities, unusual tenurial agreements or new industries, a new workforce did migrate to the area eventually. In subsequent years, many more residential extensions such as Richards Town (1910) and Cooke Town (1910) (beyond the railway line seen highlighted in ) were encouraged by the Station’s Municipal Board. Together they would bridge the distance between Fraser Town and the General Bazaar.

Figure 9. Fraser town near later planned developments of Richards Town and Cooke Town in relation to the General Bazaar. Bangalore Guide Map 1935-36. Map Courtesy: The Mythic Society Bangalore. Photo: Authors Own.

While Fraser Town would continue to provide the model for private enterprise to replicate, buildings adhering to the five plague-proof rules did not extend elsewhere in the city let alone in surrounding localities. Stephens would attribute the inability to do so to a racially loaded ‘spirit of procrastination’ to construct a narrative that it was inhabitants’ fault that his model had not been followed elsewhere despite the colonial government constantly emphasizing that there was not enough money for planning.Footnote79 Fraser Town was anomalous because it relied on private benefactors. So important was their involvement that it was suggested by the British Resident that a stone obelisk be erected with their names inscribed on it. The figurative ‘making’ of Fraser Town as a prescriptive model in Bangalore where the five rules could be put to practice relied on the fact that it was much smaller than other suburbs in the city, the heavy involvement of private investors, and that the local Municipal Government was made of colonial administrators keen on manufacturing its ‘model’ prescriptiveness to expand governance via technocratic means.

The emergence of plague urbanism and the All-India Sanitary Conferences

The nineteenth century saw a global multiplication of scientific congresses and the development of international standards.Footnote80 The conferences like surveys, censuses and the differential classification of people were valuable spaces for knowledge creation and the manufacturing of cultural imaginaries. Standardization and regularization were expressions of the growing awareness of an interconnected world but also of European self-confidence to intervene in multiple arenas.Footnote81 International congresses and exhibitions on urbanism spread a new set of ideas about understanding and intervening in cities. Town planning was no exception, and the first Town-Planning Conference was held in London in October 1910. With over thirteen hundred delegates, it brought British, European, and American ideas of planning and the town planner to the forefront. Planning expertise and ideas did not develop in isolation but in parallel with colonial discourse. The insularity of British planning histories shows however that imperial endeavours were portrayed as an exercise of expertise rather than considering how colonial territories shaped town planning.Footnote82 Model dwellings based on approved, sanitary designs as in Fraser Town demonstrated how the colonies, were the location par excellence for ‘scientific’ experimentation.Footnote83 What the Conferences often elided was that practitioners like Stephens were able to operate in a system where the law could be suspended, altered, or made anew, in the service of ‘civilization’ and developing town planning as a prescriptive improvement.Footnote84

The new fictionalized enemy of plague legitimated a state of exception, with the deployment of large-scale plague urbanism and the control of urban space through technocratic means. Extensive scholarship on Presidency capital cities such as Bombay, Madras, Delhi and Calcutta show how this was achieved through Improvement Trusts that borrowed European spatial ideas for state-led expansion of cities in South Asia and beyond.Footnote85 These scholars of Presidency Capitals have rarely if ever, put them in dialogue with each other and wider planning practices beyond directly ruled British India. New planning and improvement schemes were realized in Princely cities too. Like Stephens who first began his career in the Madras Presidency and thereafter migrated to Bangalore, Patrick Geddes, who met with growing hostility from the British administrators of the Indian Civil Service served as a planning consultant for rulers of the Princely States – including the Mysore State.

Outside of biographic work on figures like Geddes and other similar planners, the importance of Princely States and their impact on planning practice is rarely discussed.Footnote86 The exception to these are discussions on Mysore as a ‘museumised landscape’ highlighted by Janaki Nair and discussions on Hyderabad’s urban and rural development projects by Eric Beverley.Footnote87 These are not focused on individual actors in planning processes or on the practice or exercise of planning and what it means. What makes the Conferences exceptional is that it is the one lone occasion where discourses of planning in the Princely States and their capital cities such as Mysore and Baroda intersected with those of Presidency capitals’ cities and towns. Fraser Town is a case in point to show the complexity and web of planning practices across Imperial India.

The AISCs hosted by the GOI between 1911 and 1914 intended to ‘open up large questions of research work and hygiene’ and acquire ‘further knowledge of the specific agents of infective disease’ as part of the prolonged fight against the plague.Footnote88 While the conferences abounded in lengthy debates over divergent scientific theories about disease and its spread, town planning in its widest sense emerged as an answer and prophylactic to every question about order and its sanitary management.

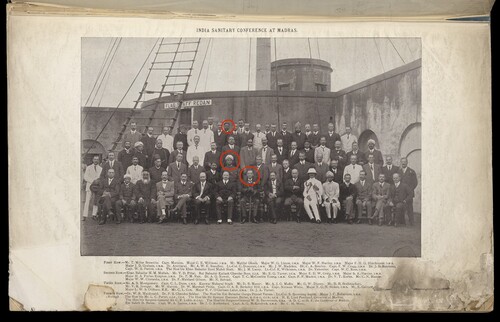

The growing scope of discussions on town planning in the conferences alongside the expanding conference procedures themselves exemplify the importance of town planning and the AISC as a means to showcase such efforts. The first AISC (1911) where Fraser Town was introduced as a model town, had thirty delegates. It addressed a range of topics including congested areas, town planning, water supply, conservancy, and drainage. It was here that the Conference passed recommendations that were similar to those carried out in Blackpully: opening up congested areas, improving drainage and introducing open spaces.Footnote89 The Second Conference (1912) with seventy-one delegates () in attendance was more comprehensive, as evidenced by its proceedings across three volumes ‘general’, ‘hygiene’ and ‘research’. The agenda included the areas discussed in the first AISC but expanded to include remedial interventions in the form of building bye-laws ‘to ensure that all future town expansions are planned on scientific lines’.Footnote90 There was a resounding consensus that ‘scientific’ plague urbanism through technocratic means could be achieved by demolishing existing houses and replacing them with ‘model houses’ like those in Fraser Town.

Figure 10. Second All-India Sanitary Conference Mr V. Rangaswamy Iyengar, Superintending Engineer of the Southern Circle, Mysore State standing 8th in the third row from the top wearing a Mysore Petta Dr S Amritraj, C & M Station, Bangalore (not in image) and the eighth person in the first row from the left, President of the conference, Sir Harcourt Butler. Source: The Proceedings of the Second All-India Sanitary Conference. Volume I – General. Government Press. 1913. Source: Wellcome Trust.

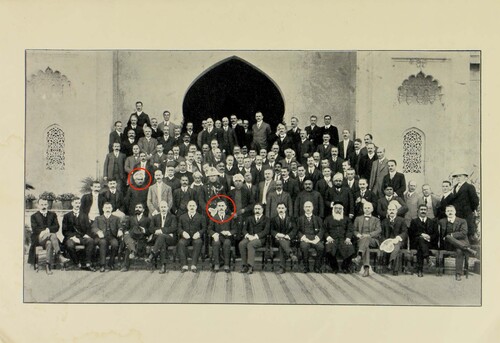

By the twentieth century, the municipality emerged as a novel unit of political engagement on the global political scene.Footnote91 Just as British officials were refining colonial urbanism as an ensemble of techniques for social control, municipalities in the subcontinent were becoming authorized arenas for formal political participation of colonial subjects. The third and last conference (1914) was a reflection of the development of the municipality. Over 103 delegates () and five volumes of proceedings highlight the Conferences as career-making arenas for administrators and members of municipalities.

Figure 11. Third All-India Sanitary Conference Mr K. Krishna Iyengar, B.A., L.C.E Deputy Chief Engineer, Mysore Durbar (absent) and Eighth person in the first row from the left, President of the conference, Sir Harcourt Butler. Source: Wellcome Trust.

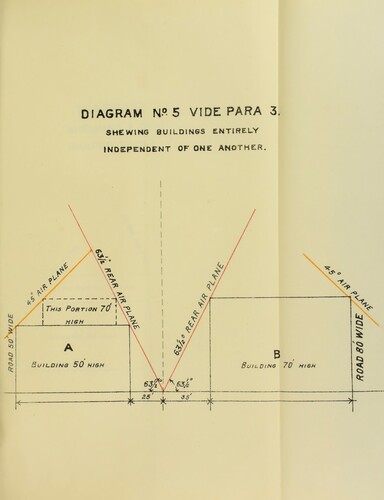

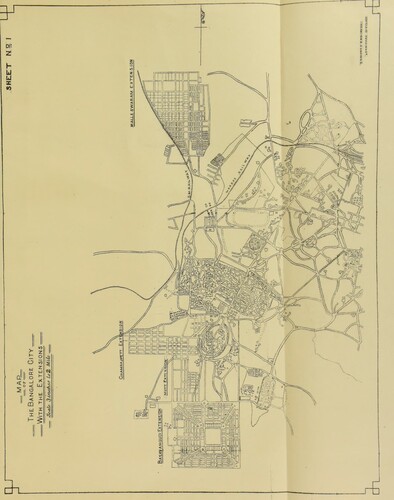

There were four papers presented at the session on Town Planning and Improvement in the last volume of the proceedings. Each showcased the varying logics of planning ideas from various ‘laboratories’: presidencies, cities, municipalities, towns, villages or localities. Out of the four papers, one was on Bombay and the other on Bangalore. The former, by. P Orr, a civil servant and Chairman of the Bombay Improvement Trust (BIT) was a ‘how to’, both, to prevent the growth of ‘insanitary slums’ but also to implement the 63 ½ ° rule. This rule where all houses were to be constructed at that angle to the horizon to allow light and ventilation was illustrated with an extensive series of axonometric drawings ().Footnote92 The latter paper presented by M.K Iyengar of the Mysore State presented regularization and standardization of new extensions in Bangalore City through, roads and streets, conservancy lanes and even the details of house connections for sewage to enter sewers. In contrast to the paper on Bombay, Iyengar was showcasing what had already been achieved in the new extensions of Basavanagudi, Malleshwaram and Chamarajpet ().Footnote93

Figure 12. J.P Orr’s 631?2 rule illustrated diagrammatically. Source: Proceedings of the Third All-India Sanitary Conference held at Lucknow, January 19th to 27th 1914 Vol IV. Source: Wellcome Trust.

Figure 13. Sheet No 1 showing the extensions in Bangalore City. Proceedings of the Third All-India Sanitary conference held at Lucknow, January 19th to 27th 1914 Vol IV. Wellcome Collection.

Other papers were focused on potential interventions that could be undertaken by encouraging local municipal bodies. The Municipal Commissioner of Shimla, Lala Jai Lal made the case for all large urban municipal bodies to be given more power by special acts of legislature.Footnote94 Ramachandra Rao, the Chairman of the Ellore Municipal Council in Madras Presidency argued for the adoption of localized versions of the English Housing of the Working Classes Act of 1890 and 1909. In doing so, he pushed Lal’s case further by also suggesting that the British Town Planning Act of 1909 be enacted in India to enable local authorities to carry out improvement schemes.Footnote95 This new legislation had been introduced in Britain on the back of the success of Letchworth and Hampstead and was concerned with developing land on the outskirts of cities by expropriating private property.Footnote96 In bringing both aspects of planning: by-laws that made housing governable and enabled municipal bodies to regulate adherence to by-laws.

Building on these papers on the 9th day of the third AISC the decision was made as to which resolutions were to be adopted as it was the last such conference. In discussions of plague urbanism, all municipalities which had not already introduced satisfactory building and drainage by-laws were encouraged to do so. The acquisition of land for the needs of town planning schemes was to be viewed as legitimate municipal expenditure. The last resolution asserted that sanitation was impeded by the lack of sanitary engineers to meet the demands for the design and execution of sanitary works, recommending this be remedied.Footnote97 The resolutions illuminate how urban practices exemplified devolution of power from the centralized GOI that the plague initiated to local government through self-rule: municipal officers, state-employed engineers, sanitation, public health officials, and even surveyors.Footnote98

In his closing remarks, President Harcourt Butler would promise to send a ‘General Sanitary Policy’ developed from the Conferences that all delegations could take from and implement across the territories they represented. The deliberations reveal, however, that the delegates never agreed on the adoption of such a policy. Neither did such a General Sanitary Policy materialize for them to implement since the colonial government did not intend on supporting such a large-scale exercise. Despite articulating the desire for a universal plague urbanism at the AISC with the example of Fraser Town to be implemented everywhere, the colonial government would relieve itself of the responsibility to do so. This was not just because the colonial government was chronically short of money for urban development, but because transferring accountability to municipalities would mean they could profit from the housing market that emerged directly from sanitary planning and absolve themselves of responsibility for local government inaction. The task of seeing these projects through relied on the neutral expertise of the municipality (like the planner).Footnote99 The AISC became another knowledge project like surveys, and censuses, part of the colonial government's knowledge production to manufacture cultural imaginaries combined with race science.

United India against disease?

Conferencing had been a political practice long before the foray into specialized professional congresses like the 1910 Town Planning Conference or geographically limited ones like the AISC 1911–1914.Footnote100 It is from conferencing that ideas of internationalism at varied scales emerged. The year of the Great Exhibition in London 1851 considered the starting point of internationalism was also the year that the first of ten International Sanitary Conferences (ISC) on Cholera in Paris.Footnote101 These marked the first attempt to tackle the propagation of disease through international cooperation beyond the divides of the West and non-West focused on scientists and diplomats.Footnote102 It was at the 1897 Sanitary Conference held in Venice where international pressure on British authorities mounted, threatening them with an embargo which had suddenly pushed Britain, previously reluctant to act, to suddenly decide to combat it.

Conferences were seen as essential performative political practices even if their outcomes were never actually enacted and were only desired. Large internationalist conferences such as the Paris Peace Conference, and the inter-war conferences (1919–1939), provided the model for sanitary conferences like the AISC in India and the International Plague Conference at Mukden in China the same year. But the nineteenth-century Cholera conferences focused came even before them. The cholera conferences were representative of how most regimes throughout the world were attempting to control closely defined territories by employing uniform administrative, legal, and educational structures just as they were attempting to work towards what they imagined to be international cooperation.Footnote103 I, therefore, use Valeska Huber’s turn of phrase of unification of the globe against disease in the context of the AISC, arguing that they provided a space in time for the GOI to transcend the limits of location be it of British, Princely India, and other territories, despite their differences.

While the AISC was premised on overcoming the limits of location beyond British territories, it was also geographically contingent on where the participants came from and how they came together to enact them.Footnote104 Contrary to the idea of a unified ‘India’ that proliferated at the conferences, the proceedings reveal it was heavily biased towards discussions on British India. Even the three locations where the conferences were held validate this inclination. Hosted at ‘convenient’ centres as described by Butler, the first two in Presidency Capital cities, Bombay (1911), and Madras (1912), and the third, and last, in Lucknow (1914), the capital of the United Provinces.

If the conferences were staged as metaphorical platforms for a shared set of problems (disease) and how to remedy them within British India, Princely India and territories permanently administered by GOI, the delegations did not adequately reflect this. The first AISC had delegations from GOI, Ceylon, Madras, Bombay, Bengal, United Provinces, Punjab, Burma, Eastern Bengal and Assam, and Central Provinces but not the State of Mysore. Despite Butler raising the example of Fraser Town in his inaugural speech, he said little about the Princely State-controlled Bangalore City. It was only at the Second AISC in 1912 that delegates who presented and attended the conference from two Princely States: Mysore and Hyderabad. Even here, a neat separation was maintained between British and Princely territories in Bangalore by having delegations from the C & M station (Dr S Amritraj, Health Officer) and Superintending Engineer of the Southern Circle, Mr V. Rangaswamy Iyengar from the Mysore State (highlighted from the conference delegation’s ). From this clear separation, it would have been difficult to tell that they shared a border at the heart of Bangalore in the same city, so close that the spread of the plague in one resulted in infections in the other. The deliberate omission of many other prominent Princely States or the North-western Provinces, Oudh, and Central Provinces where it is well known that the plague spread while including Mysore and Hyderabad in limited ways renders visible the duplicitous attempts of the conferences to make an ‘All India’ image.Footnote105

The third AISC expanded in scope and geographic reach of the delegations beyond the first two. For the first time, Bihar, Orissa, Assam, Delhi, Portuguese India, a section of ‘visitors’ and the princely North-western Provinces were included in addition to delegations from Hyderabad and Mysore (the latter is highlighted in ). The discussions grew to include papers and reports on developments in Italy alongside those related to territories within the Indian subcontinent. The expanding number of the conferences were, therefore, attempts by GOI to control British subjects in a directly ruled British India but transcend their boundaries to congregate those subjects of Princely ‘peripheries’.

The colonial government constantly differentiated between a directly ruled, British India as progressive and liberal concerned with reformist civilizing ideals to a traditional Princely India with authoritarian tendencies.Footnote106 The Imperial Legislative Council formed in 1861 and the Chamber of Princes in 1921 (a consultative-cum-advisory body) were bodies created by the colonial government in an attempt to integrate the Princely States and their rulers with the GOI. British imaginations saw these bodies as crucial to draw Indian rulers to each other and them. They also saw such action as necessary to counter increasing anti-colonial sentiment and prevent these theoretically autonomous states from striving for independence. Yet, they separated bodies like The Imperial Legislative Council and Chamber of Princes from those concerning the GOI.

Scholarship too has relegated Princely States to the margins of historical inquiry. Preoccupied with the merger of the Princely States within the Indian Union, there are a few historical moments where Princely States and their rulers have been brought together in exchange with British India as a whole.Footnote107 The year of the inaugural AISC also marked the Coronation Durbar of George V in Delhi in 1911 when governors, high ranking Officials of the GOI were brought together with princes and landed gentry were summoned to pay respects to the King.Footnote108 Dominated by titles, regalia and ceremony to reiterate and reinforce rank amongst the 560 princes attending the durbar was used to aesthetise imperial politics.Footnote109 In contrast, the AISC sought to make visible scientific progress with delegations leading in medical and sanitary research.

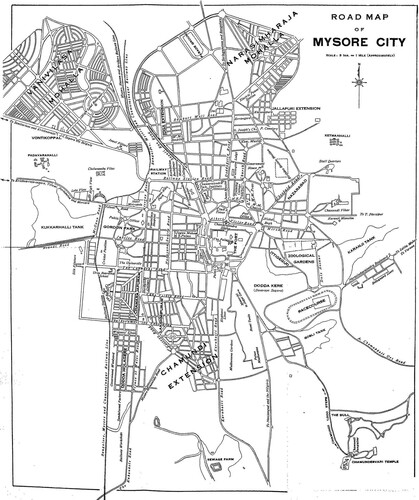

The Princely State of Mysore contested colonial authority by setting itself up as a centre of ‘modernisation’ as a countermeasure to British paramountcy to prove that modern Indians could rule themselves better than any colonial state. This was achieved through advances in industry, engineering, and technology and when concerns for public health and hygiene arose from the plague, through municipal institutions. The introduction of institutions as in other colonial cities, such as the Mysore City Improvement Board in 1903, was intended as Aya Ikegame argues, for the Mysore state to present itself as a ‘model state’ and even reclaim modernity for itself.Footnote110 Many planned extensions in Mysore City developed alongside those in Bangalore. Extensions such as Chamarajapuram, Lakhsmipuram and Chamundi Extension () were introduced to the southwest of the city.Footnote111 This was parallel to the ‘improvements’ made to the older portions of the city for which planners like Geddes were invited to intervene in. While the GOI rewarded the Mysore state as ‘progressive’ and ‘modern’ awarding it the title ‘the best administered native state in India’ the urban expansion of Mysore along sanitary lines received little mention at the Conferences.Footnote112 The obfuscation of urban sanitary developments, both, funded and put forward by the Mysore State’s Princely government while projecting it as a ‘progressive’ state in other arenas makes the fragility of colonial power explicit even in a space such as the AISC.

Figure 14. Map of Chamarajapuram, Lakhsmipuram and Chamundi Extensions in Mysore. Source: Constance E. Parsons, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

For all the emphasis that Butler had given Fraser Town in Bangalore, it was neither the first nor the only planned extension in the city. We know from M.K. Iyengar’s paper that suburbs such as Chamarajendrapet, Basavanagudi, and Malleshwaram, were all ‘hygienic’ extensions located around Bangalore City (referring back to ).Footnote113 These extensions were laid out earlier, were larger and even planned with more technocratic controls in place. Developments in Princely States, despite being integral to the imperial system, were constructed to be viewed as altered discourses, different from the western models, except when suited. It is this tension created by the Mysore State’s mimicry that reveals why other extensions in the city weren’t set up to be the model town that Fraser Town was: they were all located in Bangalore city and recognized as separate developments. It was not that the planning of Fraser Town was to be upheld as ‘the only plague-proof town in all India’ but to extol the virtues of the British controlled C & M Station areas in the Princely State of Mysore and thereby Imperial rule.Footnote114

Conclusion

In a speech at the inauguration of Fraser Town, the British Resident of the C & M Station credited the success of ‘the only plague-proof town in all India’ to the GOI.Footnote115 Within a few months, the same would be said about Fraser Town at the inaugural All-India Sanitary Conferences. Fraser Town was a layout unlike others in Bangalore and perhaps even elsewhere. Only here had the colonial government financed its development and encouraged investors in such a pronounced way – paying close attention to its layout and material specifications. But Stephens’ ambitions ‘to make the place up to date sanitarily according to the newest methods now in operation in different parts of the world’ were much bigger than Bangalore.Footnote116 In attempting to push his career further, he envisioned Fraser Town as comparable to ‘garden cities in England and Europe and College settlements in America’ and if adopted elsewhere could improve the ‘life and health of the whole nation’.Footnote117 This vision to construct moral and sanitary order through model towns was given recognition at the AISC. Appealing to sanitarians and administrators alike, Fraser Town embodied a particular type of racialised sanitary urbanism that lent itself for replication even at an ‘All-India’ scale.

Moving away from city-wide frameworks, this paper examined Fraser Town to explore what we might uncover if we viewed its development as part of a larger global history through the Third Plague Pandemic. In doing so, I brought to light a moment and space-the AISC is where such a desire for urban renewal was brought together across shared boundaries across the Indian subcontinent, between British and Princely India but also other territories.

The three conferences show how ‘sanitation’ became part of a new governmentality in need of intervention created by the state of exception created by the plague. The GOI had already treated town planning as a wide application of sanitary reform through technocratic means by deploying ‘plague urbanism’ – the only effective method for confronting disease. But from the papers presented, the discussions, and the resolutions passed, the conferences reveal the devolution of governance where the GOI transferred the deployment of plague urbanism to the role of local authorities knowing full well that they could never finance except in (Presidency Towns and some large municipalities) nor have the jurisdictional capacity (to make Princely and other territories) comply with any prescriptive sanitary reform. But the purposes of the conferences were never to do so. The conferences should therefore be interpreted as a wide failure in achieving any Imperial India-wide sanitary success but a triumph for the promotion of rational British planning by administrators. Such a campaign would aid in prescribing Fraser town as a technocratic model where houses with setbacks and uniformity of materials were idealized goals for regularizing and standardizing, concomitant to prevailing urban renewal schemes from Improvement Trusts that were already functioning to provide revenue and real estate for the state.

If the AISC was premised on overcoming the limits of location through disease, transcending boundaries of British and Princely India in search of ways to tackle the disease, it was also geographically contingent on the spaces in which people came together to conference and enact internationalist ideas. Putting forward a dubiously performative All – India served to obscure the emergent modernism of the Princely States of which planning was a part, suddenly levelled out as part of a united India at the conferences. Discussing Fraser Town and the attention paid to it in the broader context of the AISC, therefore, brought together by which ‘British ‘centres’ and Princely ‘peripheries’ become differentiated. In Bangalore, the Fraser town model was an increasingly paradoxical process exercised (if at all) only in the British controlled parts of the city and contributed to an increasingly uneven, political economy of scientific practice and planning. Just like other cities, it did not adopt the regulatory housing for large sections of the population since the forces of planning and modernity were selectively appropriated to accentuate differentiation. Reshaping the city in response to the plague was a class-driven process that would eventually exacerbate problems of congestion, and substandard housing remained in modern town planning.Footnote118 Even more, enduring would be the materializing of the discussions at the conferences, where planning and its success depended solely on local governments and their function and if they were to be exalted centrally by the Indian government, even extra-legally in response to disease.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are owed to my practice as a conservationist with INTACH Bengaluru which familiarised me with Fraser Town through a listing exercise and a subsequent exhibition in Bangalore in 2016. Ideas in this paper were first presented at the EAHN conference 2021 and its arguments were sharpened through feedback and conversations with my Architecture and Empire Writing Group- William Davis, Émélie Desrochers-Turgeon, Sylvie Dominique, Robin Hartanto Honggare, Maura Lucking, Lukas Pauer and Ian Tan. Thanks to Dr Gareth Fearn who has been subject to many versions of this paper and my colleague Sally Watson her comments. Lastly, I am indebted to my supervisors Dr Martin Beattie and Professor Zeynep Kezer who helped through every stage of its conception.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sonali Dhanpal

Sonali Dhanpal is an architect, built-heritage conservationist, and architectural historian whose primary focus is housing, property, and colonial urbanism. She is the current Royal Historical Society Marshall Fellow at the Institute of Historical Research, School of Advanced Studies, University of London and is completing her PhD, Contested Bangalore: Caste, Colonial, and Princely Politics as the inaugural Forshaw Scholar based in the Architecture Research Collective at the School of Architecture and Planning, Newcastle University.

Notes

1 Caldwell, Outbreak of Plague, 3. The incident involved Mr Williams, Loco Superintendent of the Southern Maratha Railway, and the inspecting doctor Lieutenant-Colonel Benson, Senior Surgeon to the Mysore Durbar

2 For its spread in India see Arnold, Colonizing the Body and for its continued spread see see Lynteris, Pestis Minor

3 Caldwell, Outbreak of Plague, 1.

4 Ibid., 3.

5 Dhanpal, The “Unintended” City, 116–8.

6 Ranganathan, Rule by Difference, 1391.

7 Sekher, “Plague Administration in Princely Mysore.”

8 Hassan, Bangalore through the Ages.

9 The Civil and Military Station, was an independent area under the control of the Government of India see Nair, Battles for Bangalore

10 Bangalore District Gazetteer, 45–6. See Ranganathan, 1391 for how the Station was pitted as better developed.

11 Markovits, A History of Modern India, 388. They were princes because the only King was the holder of the British Crown

12 Markovits, A History of Modern India, 387; Ikegame, Princely India Re-Imagined, 2.

13 Manor, Princely Mysore before the Storm.

14 While the ‘state of exception’ borrows itself from Agamben derived from Carl Schmitt, his use of this concept to treat the COVID-19 pandemic as a hoax mean I will be only citing Mbembe, Necropoltics.

15 Arnold, Colonizing the Body.

16 See Chandavarkar, Plague Panic and Epidemic Politics in India.

17 See Arnold, Imperial Medicine and Indigenous Societies; Catanach, The Gendered Terrain of Disaster”?; Catanach, “Poona Politicians and the Plague, c 1896–1918.”

18 Gandy, “Zones of Indistinction,” 499.

19 The Act of 1897 legitimised ‘biopower’ to impose regulations on bodies but in the colonies it was always combined with the disciplinary and the necro-political

20 Chabbria, “Manufacturing Epidemics.”

21 Gandy, The Fabric of Space; Kidambi, An Infection of Locality.

22 See Dhanpal, “The “Unintended” City” for targeting some groups in Bangalore and for the role of planning as a tool of colonial and neo-colonial subordination see Beebeejaun, “Provincializing Planning”; King, Exporting Planning in Shaping an Urban World; Njoh, Urban Planning as a Tool of Power and Social Control in Colonial Africa.

23 Stephens, Plague Proof Planning in Bangalore, 74.

24 Legg, Imperial Internationalism, 36.

25 Proceedings of the All-India Sanitary Conferences 1912, 3.

26 Huber, “The Unification of the Globe by Disease?” uses Le Roy Ladurie’s turn of phrase from The Unification of the Globe by Disease.

27 For difference between global history and globalization history see Ogborn, Modern Historical Geographies, Global Lives.

28 Dossal, “Limits of Colonial Urban Planning”; Datta, “How Modern Planning Came to Calcutta”; Kishore, “Urban Failures” and more recent Satam, “Influenza Pandemic and the Development of Public Health Infrastructure in Bombay City.”

29 Ulrike and Von Oppen, Translocality,1.

30 Beebeejaun, Provincializing Planning.

31 Tumbe, Age of Pandemics, 98.

32 Legg et al., Placing Internationalism; Huber, The Unification of the Globe by Disease?

33 General and Revenue Secretariat, “Transfer of the Plague Establishment to the Municipality”. See Hazareesingh, Colonial Modernism and the Flawed Paradigms of Urban Renewal for discussions on congestion.

34 Kidambi, An Infection of Locality.

35 Herscher, “Black and Blight”.

36 Beverley, “Colonial Urbanism and South Asian Cities” provides an overview of Improvements trusts and colonial urbanism

37 Home, Of Planting and Planning, 205. While ‘trust’ while implied that they were for public good with public consultation, they became profit-making sources of revenue for the city corporation and municipalities.

38 Municipal File, Lands acquired for laying out Chamarajapete Adjustment of expenditure for acquiring fresh lands in connection with the extension of Bangalore city, 1891.

39 Caldwell, Outbreak of Plague, 24.

40 Ramesh, “Flows and Fixes,” 16, 20.

41 See Dhanpal, “The “Unintended” City” for examples of occupations of inhabitants catering to the C & M Station.

42 Ramesh, “Flows and Fixes.”

43 Ibid.

44 Caldwell, Outbreak of Plague, 24.

45 Tywhitt, Patrick Geddes in India, 45.

46 Cadwell, Outbreak of the Plague

47 Legg, Stimulation, Segregation and Scandal.

48 Stephens, Plague Proof Planning in Bangalore, 97.

49 Nair, “Beyond Nationalism,” 334.

50 Herscher, “Black and Blight”.

51 Legg, Spaces of Colonialism,150.

52 Stephens, Plague Proof Planning in Bangalore, 18.

53 Beebeejaun, “Provincializing Planning,” 10.

54 There was emphasis in reports to rename it Fraser Town and not refer to it as Papareddipalya

55 Iyer, Discovering Bengaluru, 198–9.

56 Chabbria, Making the Modern Slum provides a useful discussion on how a 'shelter' is constructed differently to that of a 'house'.

57 Glover, A Feeling of Absence from Old England.

58 Stephens, Plague Proof Planning in Bangalore, 73.

59 Nair, Promise of a Metropolis.

60 Chhabria, Making the Modern Slum, 88,114.

61 Hawgood, Waldemar Mordecai Haffkine.

62 Stephens, Plague Proof Planning in Bangalore, 34.

63 Lynteris, A ‘Suitable Soil’.

64 Stephens, Plague Proof Planning in Bangalore, 66.

65 Ibid., 82.

66 Stephens, Plague Proof Planning in Bangalore, 78.

67 For discussion on bungalows see King, The Bungalow or more recent Desai and Desai, The Bungalow in Twentieth Century India.

68 Stenzl, The Basel Mission Industries in India.

69 Stephens, Plague Proof Planning in Bangalore, 82.

70 Cowell, The Kacchā-Pakkā Divide, 1.

71 Scott, Seeing like a State.

72 Ikegame, Princely India Re-Imagined, 130.

73 Stephens, Plague Proof Planning in Bangalore,113.

74 Ibid., 92.

75 Ibid., 90.

76 Stephens, Plague Proof Planning in Bangalore.

77 Municipal File, Lands acquired for laying out Chamarajapete

78 Ibid.

79 Beebeejaun, “Provincializing Planning,” 12.

80 The International Units of Weights and Measures (1875) or the fixed of the prime meridian at Greenwich for the basis of the world standard time zone system (1884).

81 Huber, The Unification of the Globe by Disease? 458.

82 Beebeejaun, “Provincializing Planning.”

83 Ibid.

84 Cadwell, Report on the Outbreak of Plague in the Civil and Military Station.

85 Home, Of Planting and Planning.

86 For early hagiographic work on Geddes across India see Tyrwhitt, Patrick Geddes in India and more recent critical biographical work Miller Patrick Geddes.

87 Nair, Mysore Modern; Beverly highlights some of the Hyderabad’s rural and urban development projects, envisioned alternative modernity in princely states to that of British colonial modernity.

88 Proceedings of the First All-India Sanitary Conferences 1911.

89 Ibid.

90 The Proceedings of the Second All-India Sanitary Conferences. See paper on Relief of congestion in the C & M Station, Bangalore and Results113, 114.

91 Beverley in Colonial Urbanism and South Asian Cities overviews how municipalities are well known to have been entry point into state politics for native populations in India.

92 The Proceedings of the Third All-India Sanitary Conferences 1914, Vol IV, How to Check the Growth of Insanitary Conditions in Bombay City, 145–182. For Orr’s in Bombay see Chabbria, Making of the Modern Slum, 172.

93 The Proceedings of the Third All-India Sanitary Conferences 1914, Vol IV, Extension of Bangalore City, 206–12.

94 ‘Sanitary Improvement of Urban Areas’ 200205.

95 The Proceedings of the Third All-India Sanitary Conferences 1914, Vol IV, Town Improvement Schemes and Building Bye Laws in the Madras Presidency, 184–198.

96 Spodek, “City Planning in India under British Rule,” 10.

97 The Proceedings of the Third All-India Sanitary Conferences 1914, Vol I, Discussion and Resolutions, 323–5.

98 The Proceedings of the Second All India-Sanitary Conferences 1912, Vol I 323–5 and similar discussion in Chabbria on discussion of devolution of power in Bombay 142,142.

99 Beebeejaun, “Provincializing Planning.”

100 See Legg, Placing Internationalism for examples.

101 Huber, “The Unification of the Globe by Disease?” These were hosted between 1851 and 1894.

102 Huber, “The Unification of the Globe by Disease?” 454.

103 Ibid., 471–2.

104 See Legg, Placing Internationalism. For where this framing is borrowed from.

105 General and Revenue Secretariat, ‘Appointment of Commission to Enquire Certain Questions Connected with Plague 1898’

106 Mallampalli, Christians and Public Life in Colonial South India, 21.

107 See early nationalist historiography Menon, The Story of the Integration of the Indian States or more recent Bangash “A Princely Affair.”

108 Bhagavan, Demystifying the ‘Ideal Progressive’.

109 Metcalf, An Imperial Vision.

110 Nair, Mysore Modern. Shows the State of Mysore envisioned an alternative modernity to that of British colonial modernity

111 Issar, The Royal City, 11.

112 Manor, “Princely Mysore Before the Storm”; Bhagavan, “Demystifying the ‘Ideal Progressive’” show how these concepts were to be viewed as altered discourses, constructed differently from the western models.

113 The Proceedings of the All India-Sanitary Conferences 1912, 3. Vol IV 206–212.

114 Stephens, Plague Proof Planning in Bangalore.

115 Ibid., 107.

116 Ibid., 90.

117 Ibid.,79.

118 Chandavarkar, The Origins of Industrial Capitalism in India.

Bibliography

- The Proceedings of the First All-India Sanitary Conference held at Bombay, November 13th to 14th 1911, Superintendent Government Press, 1911.

- The Proceedings of the Second All-India Sanitary Conference held at Bombay, November 13th to 14th 1911, Superintendent Government Press, 1912.

- The Proceedings of the Second All-India Sanitary Conference held at Madras, November 11th to 16th 1912, Central Branch Press, 1912.

- The Proceedings of the third All-India Sanitary Conference held at Lucknow, January 19th to 27th 1914, Thacker, Spink, 1914.

- The Proceedings of the third All-India Sanitary Conference held at Lucknow, January 19th to 27th 1914, Thacker, Spink, 1914. Volume 1V Papers.

- Arnold, David. Colonizing the Body: State Medicine and Epidemic Disease in Nineteenth Century India. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

- Arnold, David. Imperial Medicine and Indigenous Societies, Studies in Imperialism. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1991.

- Bangalore District Gazetteer (Bangalore, 1875), 45–6.

- Bangash, Yaqoob Khan. A Princely Affair: The Accession and Integration of the Princely States of Pakistan, 1947-1955. Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Beebeejaun, Yasminah. “Provincializing Planning: Reflections on Spatial Ordering and Imperial Power.” Planning Theory 21, no. 3 (2022): 248–268.

- Beverley, Eric Lewis. “Colonial Urbanism and South Asian Cities.” Social History 36, no. 4 (November 2011): 482–497.

- Beverley, Eric Lewis. Hyderabad, British India, and the World: Muslim Networks and Minor Sovereignty, c. 1850–1950. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Bhagavan, Manu. “Demystifying the ‘Ideal Progressive’: Resistance Through Mimicked Modernity in Princely Baroda, 1900-1913.” Modern Asian Studies 35, no. 2 (2001): 385–409.

- Bhattacharyya, Debjani. “The Indian City and its ‘Restive Publics’.” Modern Asian Studies 55, no. 2 (2021): 665–695.

- Bigon, Liora. “Bubonic Plague, Colonial Ideologies, and Urban Planning Policies: Dakar, Lagos, and Kumasi.” Planning Perspectives 31, no. 2 (2016, April 2): 205–226.

- Cadwell, P. R. Report on the Outbreak of Plague in the Civil and Military Station, Bangalore 1898-99. Bangalore: Paragon Press, 1899.

- Catanach, I. J. ““The Gendered Terrain of Disaster”?: India and the Plague, c. 1896–1918.” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 30, no. 2 (2007, August): 241–267.

- Catanach, I. J. “Poona Politicians and the Plague.” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 7, no. 2 (1984 December): 1–18.

- Chandavarkar, Rajnarayan. The Origins of Industrial Capitalism in India: Business Strategies and the Working Classes in Bombay, 1900-1940. Vol. 51. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Chhabria, Sheetal. Making the Modern Slum Book: The Power of Capital in Colonial Bombay. Washington: University of Washington Press, 2020.

- Copland, Ian. The Princes of India in the Endgame of Empire, 1917-1947. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Cowell, Christopher. “The Kacchā-Pakkā Divide: Material, Space and Architecture in the Military Cantonments of British India (1765-1889).” ABE Journal. Architecture Beyond Europe 9-10 (2016): 1–28.

- Datta, Partho. “How Modern Planning Came to Calcutta.” Planning Perspectives 28, no. 1 (2013, January 1): 139–147.

- Dhanpal, Sonali. “The “Unintended” City: A Case for Re-Reading the Spatialization of a Princely City Through the 1898 Plague Epidemic.” In ConCave Ph.D. Symposium 2020; Divergence in Architectural Research, 113–124. Georgia: Georgia Institute of Technology, 2021.

- Desai, Madhavi, and Miki Desai. The Bungalow in Twentieth-Century India: The Cultural Expression of Changing Ways of Life and Aspirations in the Domestic Architecture of Colonial and Post-Colonial Society. London and New York: Routledge, 2016.

- Dossal, Mariam. “Limits of Colonial Urban Planning: A Study of Mid-Nineteenth Century Bombay’.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 13, no. 1 (1989): 19–31.

- Ernst, Waltraud, and Biswamoy Pati, eds. India's Princely States: People, Princes and Colonialism. London and New York: Routledge, 2007.

- Freitag, Ulrike, and Achim Von Oppen. Translocality: The Study of Globalising Processes from a Southern Perspective. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2010.

- Gandy, Matthew. “Zones of Indistinction: Bio-Political Contestations in the Urban Arena.” Cultural Geographies 13, no. 4 (2006): 497–516.

- Gandy, Matthew. The Fabric of Space: Water, Modernity, and the Urban Imagination. Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 2014.

- General and Revenue Secretariat, “Transfer of the Plague Establishment to the Municipality”, 99 1898, File 24 of 1898-9, Karnataka State Archives.

- General and Revenue Secretariat, “Appointment of Commission to Enquire Certain Questions Connected with Plague 1898”, File 58 1898, Karnataka State Archives.

- Glover, William J. ““A Feeling of Absence from Old England:” The Colonial Bungalow.” Home Cultures 1, no. 1 (2004, March 21): 61–82.

- Glover, William. J. Making Lahore Modern: Constructing and Imagining a Colonial City. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

- Hassan, Bangalore through the Ages.

- Hawgood, Barbara J. “Waldemar Mordecai Haffkine, CIE (1860–1930): Prophylactic Vaccination Against Cholera and Bubonic Plague in British India.” Journal of Medical Biography 15, no. 1 (2007, February): 9–19.

- Hazareesingh, Sandip. Colonial Modernism and the Flawed Paradigms of Urban Renewal for discussions on congestion.

- Herscher, Andrew. “Black and Blight.” In Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present, edited by Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis, and Mabel O. Wilson. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020.

- Home, Robert. Of Planting and Planning: The Making of British Colonial Cities. London: Routledge, 2013.

- Huber, Valeska. “The Unification of the Globe by Disease? The International Sanitary Conferences on Cholera, 1851-1894.” Historical Journal 49, no. 2 (2006): 453–476.

- Ikegame, Aya. Princely India Re-Imagined. London and New York: Routledge, 2013.

- Issar, Tribhuvan Prakash. Mysore, the Royal City. Bangalore: Marketing Consultants & Agencies, 1991.

- Iyer, Meera. Discovering Bengaluru- History, Neighbourhoods, Walks. Bengaluru: INTACH Bengaluru Chapter, 2019.

- Kidambi, Prashant. “An Infection of Locality': Plague, Pythogenesis and the Poor in Bombay, c. 1896 – 1905.” Urban History 31, no. 2 (2004): 249–67.

- King, Anthony D. The Bungalow: The Production of a Global Culture. London: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1984.