ABSTRACT

This article is the second part of a discussion of what we term the ‘centre-idea’. This idea, we argue, was fundamental to British modernist architecture and planning praxis from the mid-1940s onwards. It represented an active spatial environment in which people could develop their selves and their interests at a time of expanding democracy, which required new forms of community association. We locate this idea’s roots in the pre-war British voluntary sector, specifically the activities of the Peckham Experiment and the Pioneer Health Centre which housed it, and evidence its long-term influence on post-war architecture and planning theorization. The article begins its discussion in wartime Britain and it traces how the ‘centre-idea’ was absorbed into the committees, plans and discussions which underpinned post-war reconstruction. It also documents how a CIAM dominated by Anglo-American theorists developed the idea into a particular understanding of, and approach to, modernist design and planning. These two strands are brought together in an analysis of their realization in a series of now state-sponsored projects, which include the Design Centre and the South Bank Arts Centre.

This article is the second part of a two-part discussion which argues that the reforming ideas of the 1920s and 1930s had a fundamental influence on post-1945 planning and architecture in Britain.Footnote1 Our argument is that what we term the ‘centre-idea’ – a concept of an active spatial environment that was a setting in which people could develop their selves and their interests at a time of expanding democracy, and which required new forms of community association– originated in the activities of the voluntary sector in Britain before 1939, not least the Peckham Experiment and the Pioneer Health Centre which housed it, and then spread, especially through professional networks, to inform a range of building types and institutions. Attesting to the urban and planning implications of the idea, one of the founders of the Pioneer Health Centre was invited to address the eighth meeting of the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) in 1951. By then, the centre-idea was increasingly being taken up in official discourse, a move that was clearly signalled by Maxwell Fry’s model community centre of 1939, which was exhibited at the New York World’s Fair.

The following account picks up the story during the Second World War, which contemporary reformers quickly understood as putting in place community settings of a kind that realized some of the associational relations envisaged by 1930s reformers. On the one hand, the article traces the committees, plans and discussions which underpinned post-war reconstruction; on the other, it documents how CIAM, now dominated by UK and US thinkers, developed the centre-idea into a particular understanding of, and approach to, modernist design and planning. These two strands are brought together in an analysis of their realization in a series of now state-sponsored projects.

Planning the future city: a common approach

It was after 1941 that concerted moves began to be made towards planning for reconstruction. These came in the wake of the Declaration of St James’s Palace (June 1941) and the Atlantic Charter (August 1941), which outlined the Allies’ aims for peacetime and looked to ‘a world in which, relieved of the menace of aggression, all may enjoy economic and social security’.Footnote2 Many came to the conclusion that, as Charles Madge wrote in January 1943, ‘a social war’ was underway, ‘carrying into battle the great drive of our time towards a reconstruction of the social contract.’Footnote3 Julian Huxley spoke of the beginning of a ‘planning revolution’ while the new social and spatial conditions created in wartime by the mass movement of troops and war work seemed to prove the pre-war anticipatory notion that a new citizen could be formed out of the dynamic interplay between people and space.Footnote4 It is not surprising (although it has been largely unremarked hitherto), therefore, that aspects of the centre-idea permeated discussion about the state of the nation from this time onwards, such as the creation of settings in which community life should be engendered, the deployment of terminology such as the ‘centre’ or ‘instruments’, and an emphasis on agglomeration of function, alongside a conception of the citizen as cultured and engaged. Central to this assimilation was the fact that many of the key figures involved with the genesis of the centre-idea in the 1930s were at the core of these debates. They created an expanding zone of mutuality, with the most significant being that around Innes Pearse and the increasingly influential planner, Jaqueline Tyrwhitt. The latter would prove the connective tissue that linked this innovative strand of British socio-spatial thinking to CIAM and thence to broader re-castings of the nature and purpose of architectural modernism.Footnote5

Tyrwhitt had been among the first students at E.A.A. Rowse’s School for Planning and Research in National Development (SPRND, an offshoot of the Architectural Association) and achieved its diploma in town planning in 1939. After a period of war service in the Women’s Land Army she took up the post of Director of the newly-founded research arm of the SPRND, the Association for Planning and Regional Reconstruction (APRR) in early 1941. This appointment placed her at the heart of the most progressive reform networks nationally and then internationally. Based initially in the Building Centre and later in the former offices of the architect Judith Ledeboer (who was now working for the Ministry of Health) in Russell Square, the Association conducted research into diverse aspects of the re-planning of Britain (including industry, health, population and housing). Here she developed a systematic approach to what she described as the ‘cross-disciplinary survey techniques that could be put into practice for the physical re-planning of Britain’; an approach she saw as ‘a requisite for the realisation of the ideal human environment.’Footnote6

Tyrwhitt linked the Association informally with the Housing Centre and the Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA), and, later, with the National Council of Social Service (NCSS) also. Such connections undoubtedly affected how her approach to planning evolved but perhaps the most important collaboration in this respect was that with Innes Pearse. Ellen Shoskes notes that Tyrwhitt enjoyed the fact that Pearse was ‘full of biological concepts of planning’ and documents how closely the pair worked on the APRR Broadsheet on Health and the Future (published 1943, not long after Pearse’s book The Peckham Experiment appeared) as well as one on Education.Footnote7 The regular discussion meetings held at the Association became an important forum through which Pearse, in turn, was able to discuss and disseminate her ideas.

The Pioneer Health Centre became an important exemplar for Tyrwhitt, not just for the notion of an organic society that it modelled but also for the connections it made between communities and particular types of space in an urban context. Thus Shoskes notes that another important circle with which Tyrwhitt began to connect with was that of modernist architects. She had made links with the RIBA which, with the exception of its librarian, the very well-networked Bobby Carter, she found rather stuffy. But it seems likely that Carter (as well as Ledeboer) led to her an association with CIAM’s British wing, the Modern Architectural Research (MARS) Group of reformist architects, planners, and their allies. She was interested in its 1942 Plan for London (published in the Architectural Review that June) and started to attend meetings of its Town Planning Committee. By 1945 she had joined the Group as a member.

MARS’s 1942 Plan for London offered an early rehearsal of many of the tropes that would come to characterize wartime planning praxis.Footnote8 This typically revolved around the idea that towns and cities might be planned (or replanned) with coherent ‘neighbourhood units’, i.e. areas containing 6-10,000 people which would serve, on the one hand, as a practical unit of organization (containing the number of households needed to support local schools and shops) and, on the other, as an intended source of identity at a level below the town or city as a whole.Footnote9 London was famously depicted by Patrick Abercrombie (Director of the TCPA) and JH Forshaw in the 1943 County of London Plan as a patchwork of idealized communities, shown in almost biological fashion like cells under a microscope; a parallel to the Peckham notion of the formation of a ‘live organismal society’.Footnote10

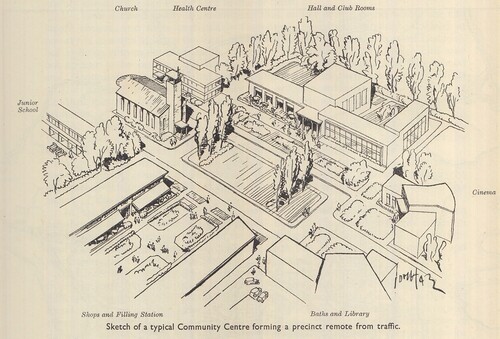

These neighbourhoods were conceived as the antithesis to what reformers perceived as the unplanned sprawl of 1930s suburbia. Yet although they suggest a centrifugal approach, in that they fragmented the city into separate units, each was to have what the Dudley Report on housing design described in 1944 as ‘some principal focal point, some definite “centre”’.Footnote11 That this was so owes much to the fact that the committee that produced the Report was either staffed by (or called as witnesses) many of those involved in generating the centre-idea before 1939, including the Housing Consultant Elizabeth Denby, as well as representatives of several voluntary housing associations, the Housing Centre, the NCSS, the TCPA, and the APRR; Ledeboer was its Secretary, and author of much of the final text.Footnote12 These ‘definite centres’ would form a neighbourhood focus, visually and conceptually. They would offer opportunities to develop productive and communal forms of recreation, appealing to bodily health as well as questions of education and citizenship. They were construed variously as one building, or as a cluster that formed a focal point. The Greater London Plan of 1944 imagined these centres with halls, a gymnasium, and spaces for crafts, reading, and games.Footnote13 Stanley Gale’s Modern Housing Estates of 1949 similarly proposed a ‘civic centre’ at the heart of the neighbourhood which would comprise a health centre, swimming baths, library, theatre and shops.Footnote14 An illustration of just such a grouping, labelled as a ‘community centre’, appeared in Abercrombie and Paton Watson’s 1943 plan for Plymouth ().

Figure 1. Neighbourhood centre, as proposed in the Plan for Plymouth, by Patrick Abercrombie and J. Paton Watson, 1943.

‘Civic’ did not automatically exclude non-commercial uses. One might nonetheless see ‘public buildings, some welfare and recreational buildings’ as tempering the commercial imperatives otherwise present in the ‘centre’. In tones that had strong echoes of the Housing Centre’s rhetoric, the NCSS continued to invoke concepts of governance and citizenship, hoping that centres might contain a room housing newspapers and even copies of Hansard, the parliamentary record. It would facilitate and embody:

the ordering of our relationships as citizens … In the very life of the centre, in the range of its activities and its method of self-government, there is encouragement to initiative and the exercise of freedom (basic qualities of democratic civilisation) … Footnote15

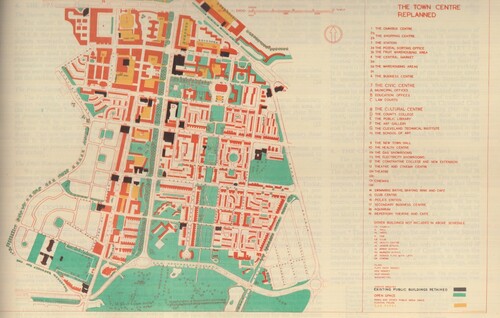

An exemplar of such thinking, as well as of the zone of mutuality that underpinned the dissemination of the centre-idea, can be found in the 1945 plan for Middlesbrough in Teesside ().Footnote17 This was prepared by a carefully assembled team, an agglomeration of experts that parallels the agglomeration of functions in the centre concept. Its leader was the architect-planner Max Lock. Alongside several sociologists, notably Ruth Glass, Lock brought together architects including Justin Blanco White and Jessica Albery, both of whom had pre-war links with the Housing Centre, as well as Ledeboer and Denby. The team also drew on social surveys overseen by Tyrwhitt’s APRR. The resulting document proposed a number of ‘centres’, each functionally specific but together contributing to ‘the town centre replanned’, a form of words which established its spatial centrality and also its conscious organization.Footnote18 Within a layout that mixed Beaux-Arts avenues with deliberate asymmetries, these centres included a ‘civic centre’ and a ‘cultural centre’, in addition to an ‘omnibus centre’ and ‘shopping centre’. The civic centre was understood in narrower terms than some of the examples we have encountered: it was to contain the municipal offices, education department, and law courts. Opposite, the ‘cultural centre’ included a college, technical institute, central library, and art gallery: it was a place of active learning as well as passive reception. Nearby were other related functions, including a health centre, gas and electricity showrooms, and a ‘theatre and cinema centre’ with several auditoria. The town centre as a whole was thus a rationally planned setting for modern life and modern citizenship, a notion echoed in Lock’s address to Middlesbrough council in 1945 in which he made play of the borough motto Erimus: ‘we shall be.’Footnote19

Figure 2. Proposed Middlesbrough town centre, as illustrated in the Middlesbrough Survey and Plan, by the team led by Max Lock, 1946.

The Middlesbrough Plan’s inclusion of a theatre and cinema centre alongside a cultural centre revealed a further consolidation of the centre-idea in wartime, namely its association with the idea of a culturally literate citizenry. In January 1943, W.E. Williams (then Director of the Army Bureau of Current Affairs and Editor in Chief of Penguin Books) wrote an article for an issue of the Picture Post devoted to a ‘Changing Britain’. Under the title ‘Are we building a new British culture?’, Williams noted the consequence of the agglomeration of people (military or civilian) into new and communal spatial contexts (the barracks or the factory): ‘In millions of men and women a new understanding and appreciation for the arts has grown up.’Footnote20 He looked ahead:

Let us so unify our popular culture that in every considerable town we have a centre where people may listen to good music, look at paintings, study any subject under the sun, join in a debate, enjoy a game of badminton - and get a mug of beer or cocoa before they go home.Footnote21

The kind of cultural centre invoked by Williams was a particular focus for the elaboration of the centre-idea in wartime, running in parallel with the urban scale discussed above. In 1943 an amateur theatre company, the People’s Players in Manchester, conceived a ‘cultural centre’ dedicated to ‘artistic work of all kinds’.Footnote22 It represented voluntary initiative, but this period is notable for the introduction of state subsidies for the arts. The wartime Council (originally Committee) for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts was in the first instance an initiative of the Pilgrim Trust but soon came within the government’s orbit. It was transformed in 1945 into the Arts Council for Great Britain, offering subsidies for the arts.Footnote23 Although limited budgets and post-war building restrictions both meant that the newly formed Arts Council’s initial priority was artistic practice, the idea of a ‘centre’ also figured large in its early thinking. That this was the case reflected the particular interests of Williams, who became its first Secretary-General, whilst also paralleling the state’s growing interest in community centres. In 1945, the Arts Council published a brochure illustrating a prototype ‘arts centre’, dedicated to music, theatre and the visual arts.Footnote24 These centres would be constructed in medium-sized towns, i.e. places too small to have separate theatres, concert halls and art galleries. In essence, they reflected ‘decentralization’, i.e. the spread of the arts from major towns and cities. Simultaneously, however, they were ‘centralized’ foci at the local level. Like those 1930s civic centres dedicated to the efficient prosecution of local government, they also were to be places of specialist expertise, efficiently providing for the arts through their dedicated spaces and equipment.

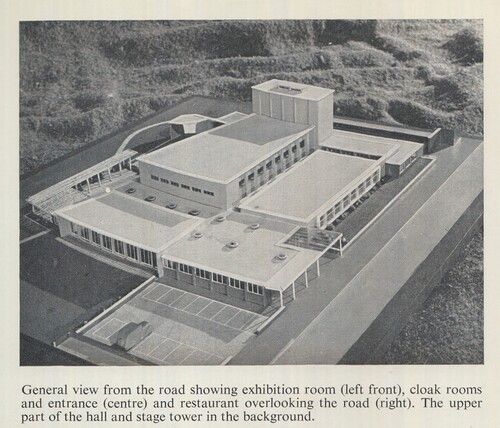

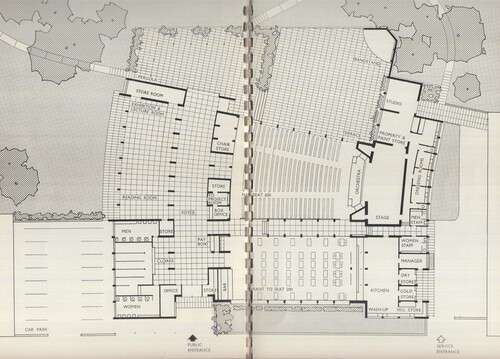

The term ‘arts centre’ - at least in the singular - can be traced back to the writer George Bernard Shaw, who in 1905 suggested that ‘all towns could have an “art centre”’.Footnote25 The Arts Council, meanwhile, in 1945 invoked as models a range of international examples as well as the British community centres of the 1930s, not only as illustrations of buildings similarly for social and cultural purposes, but for the way in which they were increasingly supported financially by central and local government.Footnote26 Its prototype echoed the disaggregated planning (and fan-shaped auditorium) of Impington Village College (see Part One) as well as the mixed programme and visual transparency of the Pioneer Health Centre. The brochure includes several possible designs, each a low-slung building with large windows, containing spaces for performance, display and refreshment ( and ). In its flat roofs, articulated volumes and expansive glazing, it was clearly ‘modern’ in form, yet its rubble-stone walls situated it within a contextual design tendency which had emerged in the late 1930s, in which ‘international’ ideas of modern architecture were transformed by what were understood to be regional or national inflections. The arts centre’s walls thus potentially represented a ‘national’ modern architecture, embodying at least in abstract form the notional common culture the building was intended to contain.

As in the Pioneer Health Centre, clarity and transparency were stressed. The main entrance was to be ‘prominent’, while once inside the foyer ‘the layout of the plan is apparent’; this space was to be ‘well lit through glass domes in the roof’.Footnote27 Views into and from the building were emphasized. Large windows would ‘frame the picture of the street’, rooting the building in its community but also allowing views of the interior from the street as a spur to action.Footnote28 Within the building, spaces were to open one onto the next: the exhibition room, for example, could function as an extension of the foyer, meaning that those attending performances might be tempted also to view the displays during the interval.Footnote29 The auditorium, which was intended to be used in conjunction with any or all of the exhibition room, restaurant and adjacent open-air terrace, was to have a stage combining a degree of flexibility with a permanent proscenium arch and specialist stage technologies.Footnote30 It was to be a space for amateur performance as well as professional work, involving the community. The atmosphere was to be determinedly non-institutional: ‘a touch of colour; taste and exuberance in furnishings and fittings; and a general air of well-being and comfort … we must rid ourselves of the idea that art is a palliative for social evils or a branch of welfare work.’Footnote31

To some extent, the arts centre prototype has come to be seen as a route not taken, with its interest in community participation rather than the professional excellence which dominated the Arts Council’s funding during the 1950s.Footnote32 However, in important respects it can be seen as being as germinal a prototype as Fry’s community centre design of 1939 (discussed in Part One) and part of a broader re-thinking of arts buildings in post-war Britain.Footnote33 This is not only because it embodied a relationship between the state, new forms of culture, and the spaces in which they were housed, but also because of its imagined architectural language. Its contextualism represented a distinct shift away from the internationalist abstraction of early modernism and suggests its authors were familiar with ongoing debates within English modernist circles about the nature of a new architecture on these shores. Again we can turn to Tyrwhitt as a figure who helpfully unpicked such themes. Her connection with MARS meant that she was connected to the group’s progressive agenda, which encompassed planning as well as the development of modern architecture. Alongside the concomitant influence of Pearse, the Housing Centre and so on, she now conceived town planning as something that moved beyond the four functions that the Athens Charter had identified. Instead, it encompassed ‘the region, the neighbourhood, work, food, health, education, transport, leisure, holidays.’Footnote34 This idea (and others) was to be rehearsed in an article on Town Planning published - undoubtedly through her MARS connections - in a new journal, the Architects’ Year Book (AYB), an important mouthpiece for the new consensus on how to shape a new Britain.

Re-thinking modernism

The very first issue of the AYB was edited by Jane Drew, who did much to keep the modernist home front live and active in wartime. It was published by Lund Humphries, a firm which published a significant number of publications associated with progressive modernist thinking in planning and architecture at this time. This link goes back at least as far as Focus, which published Fry’s article on community centres in 1939 and whose editors approached the publisher because it was based across the square from the Architectural Association in Bedford Square. Tyrwhitt’s AYB article invoked the centre-idea throughout. She wrote of the need for ‘closely knit neighbourhood life; and this must be rich, abounding life … ’, and identified this as breeding ‘social consciousness and civic responsibility.’Footnote35 In a section devoted to health, the Pioneer Health Centre was her only focus. She spoke approvingly of how it demonstrated that health was ‘the result of an active life in an environment rich in varied opportunities for mental and physical development and for free and friendly social intercourse.’ As in health, so in planning more generally. She envisioned, as we noted in Part One, how ‘the three-storey building of the Peckham Health Centre may become a free grouping of single-storey buildings interwoven with the general community activities of the neighbourhood.’Footnote36 Her overall conclusion echoed the Peckham doctors’ concern for an equilibrium between the individual and the community. She wrote of how, having assembled the ‘medley of parts’, the planning team’s purpose was to produce a final plan which offered ‘a perfectly integrated whole’. The parts could ‘be recognised, the place retains its individuality - it remains itself - but for the first time it realises the enjoyment of good health as it sees its inhabitants moving easily, freely, and joyously about their own business.’Footnote37

By the time the AYB was published, Tyrwhitt had become well-established within a progressive axis that spanned modernist architecture, modernist planning and government organizations for reconstruction. Her standing in the latter was cemented when she was sent by the Ministry of Information early in 1945 to lecture in North America on town planning. She spent much of the next decade moving to and fro between the US and the UK, a transnational circumstance which, thanks to meeting Sigfried Giedion on her first visit, enabled her to become a key figure in an Anglo-American transformation of CIAM.

A degree of re-thinking of modernism was well underway as Tyrwhitt wrote. The shift in direction is clear from Drew’s dedication of the first volume of the AYB to ‘the modern, humanitarian architect’ and her observation of the balance the articles contained between ‘technical and aesthetic information and … the sociology necessary’ ahead of the ‘joyous task of creation.’Footnote38 This characterization of the architect and planner, and architecture, and its emphasis on emotions, was significant. It represented the culmination of a process of re-thinking the nature and purpose of modernism that had begun in England in the early 1930s (and somewhat later in the USA), and presaged its consolidation and refinement at both CIAM’s post-war congresses and in built form.

The deep connections between progressive social projects and progressive architects shaped how modernism in England evolved. Although the desire for an architecture ‘of a character previously unknown’ initially shaped the formal (as well as the spatial) language of projects such as the Pioneer Health Centre and Kensal House, from the beginning of the decade there had already been a questioning of the sachlich forms favoured by European modernists, a desire for a more direct correlation between the affective spaces being designed and their formal expression, as well as an insistence that modernism could and should be mutable and an ongoing project. Auke van der Woud cites Fry’s 1931 observation: ‘I find much of this new architecture of the “avant garde” too much a statement of a new discovery and too little humanized.’Footnote39 He also references J.M. Richards, who wrote in 1935 in a similar vein: ‘Design, as with culture is becoming abstract rather than humanistic.’Footnote40

It was as part of these evolving debates that Impington (and the prototype community centre) were designed. Impington’s materials (stock brick) and motifs (bay windows) suggested eighteenth-century influence. Their Georgian overtones evoked an ‘English’ model and, significantly, suggested the imagined balanced community of Georgian England, as well as a period that contemporary modernists believed had seen the same sort of universal architectural language which they now sought. Such devices formed part of what emerged as a wider regional turn as both an older and the younger generation of modernists sought to develop a language that they understood variously as more ‘English’ (in the examples here), more responsive to the taste of ordinary people, and which resisted the notion that concrete was the only ‘modern’ material.Footnote41

It was J.M. Richards who did most to theorize this turn and to connect it with the international modernist community. His post at the Architectural Review, where he had become de facto Editor by 1937, was a key platform from and through which he and others could articulate and promulgate a ‘humanistic’ modernism (as we saw in Part One, in the Review’s coverage of the Pioneer Health Centre and its issue devoted to leisure). Jessica Kelly shows how Richards’s writing from 1935 ‘was characterised by his direct engagement with and empathy for the architectural needs and values of ordinary people.’Footnote42 Such an approach stemmed in part from the Communist politics which he espoused but arguably also from his connection with the Peckham doctors and their concern for everyday life in an urban environment. On the one hand, this manifested in a certain level of preoccupation with style, which derived from a concern for the legibility of any new formal language to those beyond modernism’s inner circle. On the other, and perhaps more fundamentally, it understood the affective nature of architecture and that the spaces of architecture should not be done to people but with people, only gaining their meaning and validity through this interchange.

Richards looked to a movement in the ‘common mind’ (or ‘zone of mutuality’) which could create a ‘live universal language’ which would resonate with both architect and layperson.Footnote43 Indeed, the Architectural Review under his editorship can be understood as the ‘active potent surface’ which drew out this immanent consensus. Richards’s recollection of his determination that ‘his’ Review should appeal ‘to a wide circle of readers’ suggests this. He wrote that its contents would serve:

as a bridge between the profession and those outside; to explain to the latter what architects were trying to do, and could do if given the opportunity, and to remind the former of their clients’ rather different criteria from their own, for example of the importance of the larger setting to which their buildings must contribute.Footnote44

Richards’s and others’ theorizing shows that from the mid-1930s challenges to the reductivist concerns articulated in the Athens Charter were being made, at least in England, and that a reconceptualization of modernism as affective and people-centred was emerging. In wartime, Richards took something of a backseat in these debates as he left the Review in early 1942 in order to take up a post at the Ministry of Information (first in London and then in Egypt; Nikolaus Pevsner was his successor). He did, however, offer a sort of full stop to his re-thinking of modernism as an indicator of the baton that he passed on to his MARS contemporaries who remained on the Home Front. In an article of May 1940 he wrote this provocation: ‘the revolutionary phrase of modern architecture is now over [and] can no longer claim exemption from criticism on aesthetic grounds.’Footnote45

‘The most dangerous and difficult of steps’Footnote46

As the 1940s began, it was not only in England that such ideas were being rehearsed. Eric Mumford has charted how cultural geo-politics saw many of those most sachlich of modernists move first to the UK and then to the US. Walter Gropius, Sigfried Giedion and Josep Luis Sert gathered at the Harvard School of Design, and formed a parallel centre of re-thinking. Their revisionism had two complementary aspects, which had very strong overlaps with the thinking of Richards et al. On the one hand they were concerned with moving modernism towards a richer and more expressive language, both spatially and formally. On the other, their attention turned to setting architecture in the wider setting of the city and the region. This reflected, as Mumford argues, how CIAM had increasingly absorbed ideas from the town-planning profession into the purview of modernist architects’ practice.Footnote47 Thus in the same way that the British progressive thinkers outlined above firmly located their concerns within an urban, rural and, increasingly, a regional context, so too did CIAM members posit themselves ‘as international experts who could, after thorough study of a city, or eventually, an entire region, propose physical solutions to problems of housing, recreation and circulation that would subordinate private interests to collective interests.’Footnote48

The British concern for cities as sites that were distinctively urban (and urbane) and as places that were ‘active, potent surfaces’ for humanity can be seen in the evolution of Sert’s thought from his arrival in the US. As Mumford shows, Sert was already recasting the architect’s job as creator of an urban biology and understanding the city as a living organism; a concept that resonated with ideas already emerging in the US in the work of Robert E. Parks. The latter advocated for the concept of a human ecology and argued that the city was ‘the natural habitat of man’ [sic] but had become a site whose collective institutions and activities were increasingly weakened by suburbanization and exurbanisation (concepts that would have been very familiar to the Peckham doctors).Footnote49

It was after the publication of his major book, Can our Cities Survive? (1942) that such ideas became an increasingly more integrated part of Sert’s, and Giedion’s, thinking. The first published outcome of this evolution was ‘Nine Points on Monumentality’, a position paper co-written in 1943 by Sert, Giedion and the painter Fernand Leger (who was also living in the US at this date) for the American Association of Abstract Artists. This was followed by Giedion’s 1944 essay, ‘The Need for a New Monumentality’. In both texts, the men focused in particular on the interplay between the expression of humanity’s collective identity, the need for the distinguishing marks that made such an identity possible, and how this might be resolved by modernist architects, given that core to the project of modernism had hitherto been the rejection of the monument.

In his 1944 paper, Giedion made his well-known conceptualization of the ‘three steps of contemporary architecture’ against the chaos of the nineteenth century. To redeem this situation modern architecture had to begin with ‘the single cell’ and thence ‘ … to the neighborhood, the city,’ He concluded, ‘the second phase of modern architecture was concentrated on urbanism.’ Now Giedion moved his attention to the next step, which was ‘the most dangerous and difficult’.Footnote50 In so doing, he articulated concepts of the purpose and nature of architectural space which mapped very closely with the centre-idea as articulated in the English 1930s. In effect, step three, ‘the reconquest of monumental expression’, was to mark the reconceptualization of architecture as the Peckham doctors’ ‘active potent surface’ and to echo their and Richards’s (among others) desire to reframe the city as a place of community association and active citizenship.

Giedion’s starting point was what he identified as the fundamental desire that people had for buildings ‘that represent their social, ceremonial and community life. They want these buildings to be more than a functional fulfilment. They seek the expression of their aspirations in monumentality, for joy and excitement.’Footnote51 Like Richards, Giedion posited a true monumentality linked to periods of ‘real cultural life’ when it was possible ‘to project creatively their own image of society.’ He continued, ‘They [the people] were able to build up their community centers (agora, forum, medieval square) to this purpose.’Footnote52 The familiar ills of the preceding century - Industrialization, suburbanization - had broken this correlation and had proved itself ‘incapable of creating anything to be compared to these institutions.’ Meanwhile, modern architects had been too preoccupied with reinventing the cell and the city to attend to these more sociological and affective concerns. Thus in the present day:

There are monuments, many monuments, but where are the community centers? Neither radio nor television can replace the personal contact which alone can develop community life.Footnote53

Like the Peckham doctors, Giedion was working from the belief that certain behaviours were immanent in humanity. He wrote:

The problem ahead of us focuses on the question: Can the emotional apparatus of the average man be reached? Is he susceptible only to football games and horse races? We do not believe it. There are forces inherent in man, which come to the surface when one evokes them … his inherent, though unconscious, feeling may slowly be awakened by the original expression of a new community life.Footnote56

A slight divergence between English theories and those being developed in Harvard was in Giedion’s relative emphasis on the formal, as well as the spatial, expression of the New Monumentality. Not surprisingly, given the co-authorship of the Nine Points manifesto, Giedion looked in his 1944 paper to a revival of collaboration among architects, sculptors and painters to express a community’s emotional life. Indeed, in a section subtitled ‘Painting points the way’ he argued that artists such as Picasso, Arp, Miro and Leger had already begun to develop ‘the rebirth of the lost sense of monumentality.’ He identified ‘the urge for larger canvases’ and the use of brighter colours as well as ‘an impulse towards simplification’; a process which he identified as ‘the hallmark of any kind of symbolic expression.’ In creating ‘symbols out of the anonymous forces of our period’, he believed painters ‘may forecast the next development in architecture’. He looked, therefore for, ‘painting, sculpture and architecture [to] come together on a basis of common perception, aided by all the technical means which our period has to offer … The means for a more dignified life must be prepared before the demand arises.’Footnote58

In the same year, Sert wrote ‘The Human Scale in City Planning’, which Eric Mumford describes as a companion essay to ‘The New Monumentality’ and one that made explicit links to an unfolding CIAM approach to urbanism.Footnote59 Not only did Sert stress the need to plan for human values and the deployment of the neighbourhood unit but he went further and advocated the creation of pedestrian civic centres: ‘the civic and cultural center constitutes the most important element … its brain and governing machine.’ This was where university buildings, concert halls and theatres, a stadium, central public library, admin buildings’ as well as places for public gatherings, the main monuments constituting landmarks in the region, and symbols on popular aspiration’ would be found.Footnote60

The thinking of US and UK modernists had necessarily developed on parallel, if complementary, tracks during the war years, but the advent of peace and the first signals of definite plans for reconstruction meant that it was now possible for the various branches of CIAM to come together again and build on such re-thinkings. The final section of this paper now turns to the consolidation of this new approach to modernism and its mapping onto the reconstructed British landscape..

CIAM 6 and 7

In 1947, Max Fry outlined eight conditions which had fundamentally changed the context of architectural production since 1939.Footnote61 Among these were ‘[the] strong movement to make up deficiencies through planned re-building of new towns and regions under Government aegis,’ ‘increased awareness of the value of design in industry … ’ and ‘state patronage of arts through agencies such as CEMA, CID, British Council etc. Growth of official architecture.’ His text formed part of the preparations for the first meeting of CIAM since the fifth Congress in Paris in 1937, a moment that marked the ascendancy of the Anglo-American alliance outlined above, and the embedding of the centre-idea as it reformulated the organization’s aims and purpose in a post-war context.

CIAM 6 was held from 7 to 14 September 1947 in Bridgwater, Somerset. A small market town in the English countryside was not the typical setting for Congress; MARS member Mark Hartland Thomas explained that it was an explicit choice ‘to go into rustication away from the distraction of a great city.Footnote62 An implicit reason may have been the fact that the converted Georgian building in which the delegates met exemplified the new context, outlined by Fry, in which modernist architects were now working. It housed the Bridgwater Arts Centre, one of the first projects to be funded by the new Arts Council of Great Britain. The epitome of the centre-idea, it was the perfect setting to allow the Congress to achieve its goals. As Cornelis van Esteren observed in his opening address, ‘A CIAM congress can only succeed and achieve results if it works as a “community” - it can never succeed if each man follows his own independent line.’Footnote63

The MARS Group had taken the lead in organizing the Congress. In part this was a matter of practicality: it was too costly for most members to get to New York, the location first proposed, and was closer, as Hartland Thomas wrote, ‘to the centre of gravity.’Footnote64 Equally it reflected the continuity of thinking that had taken place in England from 1939 onwards and the growing gravitas of the MARS Group; young architects Anthony Cox and Leo de Syllas recorded in Plan that ‘to the surprise of many Continental and American delegates it was discovered that Great Britain was no longer an outsider in the international field, but had quietly achieved a position in the first rank … ’.Footnote65 Richards (now back in the UK) and architect-planner Arthur Ling attended the CIRPAC meetings that laid down the foundations for the Congress during 1946. It was eventually agreed that no theme would be adopted and that the meeting would instead function primarily as a reunion and to lay the grounds for the resumption of collective work.Footnote66

Despite the emphasis on regrouping and practicalities,Footnote67 it was clear that in spirit the Congress would end up being a working through of the ideas which had been proposed in those CIRPAC meetings. Richards had argued for a theme of architecture and the common man [sic] whereas Giedion favoured architecture and its relation to sculpture and painting. Such topics were, in many respects, sides of the same coin. Hartland Thomas reported ‘that it was realized on all sides of CIAM’ that the aesthetics of architecture were now irrevocably in their purview given that rationalized building and ‘its truthful expression’ were now ‘well-established in official and other institutions.’Footnote68 Le Corbusier put it more poetically: ‘enfin l’imagination entre les CIAM.’Footnote69

The week of Congress was a ‘moving experience’ for all who attended.Footnote70 Alongside reports from each of the national groups, which revealed that ‘the development of ideas in the several groups had been proceeding on parallel lines in spite of the scanty contacts’,Footnote71 there were visits, including one to the Bristol Aeroplane factory which was now making prefab houses, plus a number of receptions in both Bridgwater and Bristol. Delegates were hosted by members of the Arts Centre. The week culminated in a series of longer speeches. These included Richards on ‘Contemporary Architecture and the Common Man’, Giedion on ‘Our Attitudes towards Problems of Aesthetics’, while Gropius in his talk on ‘Urbanism’ insisted on the linking of schools to community centres, which he described as ‘a cultural breeding ground which enables the individual to attain his [sic] full stature within the community.’Footnote72 Such a definition surely derived from his experience at Impington, which, as we have seen, was a key pre-war instance of the centre-idea. It is not, then, surprising that Congress concluded with the pronouncement of revised aims for CIAM, cited at the beginning of Part One of our discussion.

Two years later, in July 1949, Congress met again for its seventh meeting, this time in Bergamo, Italy. Mumford characterizes this as concluding somewhat unresolved, which reflected, as Jos Bosman recalled, a primary emphasis on Le Corbusier’s project to develop a new form of Grid (the preferred terminology for a shared visual template used by delegates) through which national surveys could be presented. He had proposed this at CIAM 6, but with a tellingly revised four functions: living, working, development of mind and body, communication. This might be understood as Le Corbusier’s attempt to retain his previous pre-eminence but it acted as a slightly uneasy bedfellow to the subject of the day four plenary, ‘Report on the Plastic Arts’, led by Richards and Giedion. This considered ‘how to clarify a synthesis of the arts’ derived from a collaboration between artists and architects might occur, and to consider whether the man [sic] in the street was able to appreciate such a synthesis.Footnote73 Moreover, as Bosman notes, it jarred with the location of the conference itself. Bergamo was a plaza-town, which ‘raised fundamentally different questions about the historical continuity of a town’s growth.’Footnote74 Given this, Richards argued that attempting to answer these kinds of questions ‘could profitably be made part of CIAM’s future work.’

The heart of the city

Thus it was that in November 1949 Wells Coates wrote formally to Giedion with the MARS Group’s proposal that civic design should be the theme of CIAM 8.Footnote75 It was Tyrwhitt, however, who led its organization, continuing the pivotal role in post-war CIAM she had assumed at Bridgwater, where she had acted as intermediary between MARS and Giedion in its planning. By the time preparation began for CIAM 8, this role was firmly cemented, not least because she was now partly based in North America (at Yale and the University of Toronto). Tyrwhitt worked closely with the MARS Group to define the theme of the Congress. This was ‘the Core’, a concept so thoroughly imbued and articulated in Peckham rhetoric that it is hardly surprising that George Scott Williamson should have been invited to, and lionized at, the Congress meeting.

The transcript of Sert’s opening remarks at CIAM 8 made this clear. He noted that the MARS Group had proposed the topic because of its interest but also its difficulty (since it had not been explored before). This was precisely why it ‘becomes a CIAM subject; CIAM has always pioneered this kind of [difficult] work.’Footnote76 Before proceeding to MARS’s definition of the Core, Sert situated the topic in the context of contemporary planning concerns. He noted that in recent years this had been about ‘suburbanization’ which had reduced the city only to a place to work. He continued, ‘if we want to do something with our cities we have again to talk in civic and urban terms’ and he added ‘there is one advantage of living in a city, and that is to get man together with man [sic], and to get people to exchange ideas and to be able to discuss them freely.’Footnote77 In the suburbs, however, people see only ‘what is shown and hears what one is told.’Footnote78

Through its study of the Core, Congress’s concern was ‘to see how, by means of establishing a series of cores, we can work out the reverse process of what has been called decentralization; a process we call recentralization, to build up units and communities around center that would bring them together.’Footnote79 The desire was to create modern versions of the core or nuclei that towns and cities used to have and this he linked to a concept of democracy: ‘I believe people should be able to get together to exchange ideas and to discuss, to shake hands and look at each other directly and talk on all the things that are extremely important for our way of living if we are to keep a civic life which we can believe in.’Footnote80 Such cores could exist at different scales but together - and this was a concept that Tyrwhitt herself would speak on at Congress - they would create ‘a constellation of communities … ’Footnote81 He continued, ‘I do not see how we can form new cities or redevelop the old cities if we do not start with the place where the people have to meet, where the people have to exchange ideas, where the people know what planning and other things mean to them.’Footnote82

Such ideas can be seen in MARS’s definition of the Core as a fifth element to the Corbusian four: ‘the element which makes a community a community, and not merely an aggregate of individuals, and that an essential feature in any true organism (such as the community) is a physical heart or nucleus, which we call the Core.’ The Group added ‘a community of people is a self-conscious organism, and that the members are not only dependent on one another, but each one knows he [sic] is so dependent. It is expressed differently at different levels … but at each level a special environment is called for - both as a setting for the expression of this sense of community and an actual expression of it.’Footnote83

The Congress programme, which Tyrwhitt developed with Coates, invited members to study the Core at five scales: the housing group, the neighbourhood, town or city sector, city or metropolis.’ CIAM 8 itself took place over five days and comprised morning sessions with papers and general discussions around the Core. There were visiting speakers, with Williamson’s paper, as H.T. Cadbury Brown noted, offering delegates the connection between the human and the architectural that they were seeking. A central theme in his paper was how evolution had allowed man [sic] to be free, and ‘no longer dominated by instinct.’ The spatial corollary of this was that ‘if you get the conditions right, [his] actions will be right; they will be selective’ - hence ‘the power of the architect to fix the conditions in which life and living has to take place,’ which, he added, was ‘tremendous - almost frightening.’ Such conditions should enable what he called ‘human autonomy’ to be maintained and sustained. Moreover, in an overlap with MARS’s outline of the Core, Williamson insisted that ‘all planning for the future must be based on the new functional unity, the human organism as a whole, i.e. “the Family-in-its-Home”.’ It was ‘the Core for human development’. This was signalled not just in his title - ‘The Individual and the Community’, but also in his assertion that the ‘value of home and family is that it elicits an altruism, because each of the parts acts in awareness of the whole.’Footnote84

Williamson’s talk was, as was noted in Part One, included in The Heart of the City, the conference publication which appeared the following year. Subtitled ‘towards the humanisation of urban life’, the book comprised transcripts of the many conversations and papers that had taken place and, at Part 3, included a summary of CIAM 8 by Giedion. ‘A Short Outline of the Core’ offered a precis of the new guiding principles that drove the reorientation of modernism that had begun with CIAM 6. This stressed the need to work at a human scale, and stated that ‘the most important role of the Core is to enable people to meet one another and to exchange ideas.’Footnote85 Care should be taken that ‘both the relations of individuals with one another, and the relations of individuals with the community’ were taken into account while, in a phraseology that could have come straight from the pages of Pearse and Williamson’s pre-war writings, the Core’s function was defined as ‘to provide opportunities - in an impartial way - for spontaneous manifestations of social life. It is the meeting place of the people and the enclosed stage for their manifestations.’(italics original, underlining by authors).Footnote86 Drawing on Giedion’s concern for the synthesis of the arts with architecture it was noted that ‘Urbanism is the framework within which architecture and other plastic arts must be integrated to perform once more a social function.’ The section concluded with an instruction and encomium of sorts:

This animation of a spontaneous nature, made possible by a means - the Core - which members of CIAM can understand and include in their own plans, seems a heritage that our group, after twenty years’ work, can now hand on the the next generation. Our task has been to resolve the first cycle of the work of CIAM by finding a means to transform the passive individual in society into an active participant of social life.’Footnote87

The Festival of Britain

The Festival of Britain, staged across the country during 1951, was intended as a ‘tonic to the nation’ or, in Giedion’s characterization, ‘a collective emotional event’, after years of wartime hardship and post-war austerity. It was at once a commemoration of the centenary of the 1851 Great Exhibition and a glimpse of the new Britain that was beginning to take shape. Festival events took in the length and breadth of the United Kingdom, but this diverse geography had a clear focus in London, where the principal Festival site was located on the South Bank of the River Thames. Here, an area of run-down industrial buildings made way for a new contemporary landscape of pavilions, set around the Royal Festival Hall, which, in the words of the architect Clough Williams-Ellis was both a ‘cultural centre’ and an ‘amenity centre’.Footnote88 The official guidebook made this ‘centring’ of activities clear, referring to the South Bank site as ‘the centrepiece’ of the Festival; furthermore, it was situated in ‘the heart of London.’Footnote89

Co-ordinated by Hugh Casson and Misha Black, the site was planned as a totality, which in its synthesis of art, architecture and sculpture realized Giedion’s 1944 peroration, and, in the diversity of content, offered multiple ‘instruments of health’ to visitors. The layout eschewed the axiality and centrality typical of previous great exhibitions and world’s fairs: there was no single ‘central’ building, rather the largest structures, the Festival Hall and Dome of Discovery, flanked the Hungerford railway bridge, with the two halves of the site being labelled as ‘upstream’ and ‘downstream’, the flow of the Thames taking the place of ‘east’ and ‘west’. The pavilions themselves were laid out as a ‘narrative’, intended to suggest a particular view of Britain’s place in the world: its history, character, and contributions to contemporary science, as well as its position within the newly emerging Commonwealth. The Dome of Discovery - a display of key inventions - made this theme clear, reading as a kind of globe pervaded throughout by apparent British ingenuity in what was both a centring of Britishness and a display of its wide reach. Echoing the dispassionate conception of pre-war and wartime centres, the Festival was very definitely ‘not a trade show’,Footnote90 and even when furnished room sets were shown in the Homes and Gardens Pavilion, the prices of the items on show were deliberately not stated.Footnote91

The centre-idea was directly addressed by the Festival in several ways. In the east end of London, the newly built Lansbury neighbourhood served as a ‘live architecture’ demonstration of the planning principles of the County of London Plan, containing, in addition to new homes and public buildings, several temporary pavilions. Of these, the ‘Town Planning Pavilion’ is the most notable. In a further example of the overlap of the centre-idea oriented personnel from pre- to post-war, which also included Judith Ledeboer, Max Fry and Jane Drew, this pavilion was created by Tyrwhitt. She was invited to work on the project in January 1950 and was responsible for the script, selection and organization of the display.Footnote92 She intended that it be a ‘tangible’ demonstration of ‘her argument that the purpose of planning is to promote the fuller development of the people.’ It thus included an exhibit entitled ‘the heart of the town’, which, echoing the wartime calls for planned centres as a counterbalance to decentralization, showed ‘how a town centre might be remodelled, in order to make it once again the focus of social life’.Footnote93 Tyrwhitt invited the artist Tom Mellor to produce a diorama of ‘Avoncaster’ (based on Norwich) showing a new ‘civic centre’ as a ‘heart or centre in which its people can take a pride’ (). As well as documenting the work in progress on 14 new towns, the guide to Lansbury described ‘the heart of the town’ as ‘the focus of social activities, an essential part of a healthy community.’Footnote94

Figure 6. Avoncaster, Tom Mellor, imagined town plan for the Town Planning Exhibit at Lansbury, Festival Of Britain, 1951 (Author’s collection).

Perhaps the apogee of the centre-idea at the Festival was a building whose conception pre-dated the event’s organization and which was one of the few to outlive the complex’s demolition when it closed in October 1951. This was the Royal Festival Hall, which, for the leader of the London County Council (LCC), Isaac Hayward, was the ‘vital focus’ of the Festival: the centre of the centre, as it were.Footnote95 The LCC had earmarked the South Bank for reconstruction during the war years. Plans for new cultural and office buildings figured in the 1943 County of London Plan, which was predicated on the idea of London as an ultimate centre in a reconfigured world view. Its introduction announced: ‘This is a plan for London. A plan for one of the greatest cities the world has ever known; for the capital of an Empire, [..] the meeting place of a commonwealth of nations.’Footnote96 The reconstructed South Bank site was to include a concert hall (described as a ‘culture centre’ in the plan) which was to replace the Queen’s Hall, bombed in 1941.Footnote97 There were initial stripped-classical designs by Charles Holden, and a Herbert Rowse-inspired proposal by a senior LCC designer, Edwin Williams. However, the LCC Architect, Robert Matthew, moved during 1948 to ensure that the new hall would be designed by a hand-picked team.Footnote98 Led by Leslie Martin and Peter Moro, the architects developed Matthew’s initial concept into a building which self-consciously rehearsed the principles of the New Monumentality.Footnote99 The conceptual and architectural parallels with the Pioneer Health Centre and the 1945 Arts Centre prototype are even stronger. The official guidebook referred to ‘quite literally a transparency, whereby even the passer-by can perceive the whole inner shape and purpose of the whole great edifice.’Footnote100 Extensive glazing gave views in, especially at night, and allowed those within to situate themselves within the modernizing cityscape beyond. Within the building, a similar sense of connection was promoted by glass screens, open stairwells and views between different levels. All of this was achieved through a framed structure, the columns of which served as punctuating marks that articulated the internal space. ‘Vista succeeds to vista’, proclaimed the guidebook: ‘as you move through the foyers and promenades, if you are aware of the excitement of its vistas and its continual unfolding of space, we shall not have failed’.Footnote101 As at Peckham, so on Lambeth’s riverside: ‘the sight of action’ was to be ‘an incentive to action’ in a building ‘designed to be furnished by people and their actions’ ().

Figure 7. Staircase at the Royal Festival Hall, LCC Architect’s Department, 1951 (Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Collections).

The multi-functionality of the building was also important. Alongside the main concert hall and restaurant, the original plans included an art gallery and exhibition hall, not unlike the prototype Arts Centre. The gallery was postponed early in the design process, as was a planned second ‘small hall’, owing to a lack of materials and time. Nonetheless, an image of the intended space appeared in the official guide to the building, showing vases, sculptures and paintings on display.Footnote102 One wonders if ‘industrial design’ was to be shown alongside works of ‘art’, contributing (in an echo of Henry Morris’s commitment to art and good design at Impington) to the wider education in taste supplied by the building. In addition, the foyers were conceived as multipurpose spaces, with room for socializing and dancing as well as eating and drinking. Here, again, are echoes of Peckham as well as the arts centre prototype, namely the idea that patrons might engage in a range of potentially ‘improving’ recreational activities. This ability simultaneously to accommodate a range of activities prompted the guidebook to proclaim that the Hall ‘surely is something which at last makes the rather vague title, a “cultural centre”, a fine reality.’Footnote103

A bold and optimistic vision of a modern Britain and its citizens the Festival of Britain may have been, but base politicking saw a newly incumbent Conservative government order the demolition of much of the South Bank site. Fortunately, the modernist thinking and the centre-idea that the Festival had rehearsed survived in a disaggregated form. This, as we shall see, offered renewed versions of pre-war prototypes.

The Design Centre and the South Bank Arts Centre

Among the eight conditions that Fry outlined in 1947 was ‘state patronage of arts through agencies such as CEMA, CID, British Council etc.’ CEMA, as we have noted, became the Arts Council, whose patronage we have seen at Bridgwater and whose influence was strongly felt at the Festival of Britain. Equally important was what Fry abbreviated to CID, but which was more commonly referred to as the CoID, namely the Council of Industrial Design. Founded in 1944 ‘to promote by all practicable means the improvement of design in the products of the British manufacturing industry, it understood design as central to the process of the reinvigoration of the British economy after the war. It addressed two audiences. The first comprised manufacturers, who were to be persuaded of the integral role the designer should play in the production process – that is, not mere styling, but there from the start researching materials, consumer demand, working with engineers and others to create new goods. This would give British goods a distinctive mark both at home and abroad and help the export drive. A second audience comprised buyers and the consuming public, who should be encouraged to identify and demand such goods: a virtuous circle from which all benefited.Footnote104

The CoID emerged from a consolidation of the sort of pre-war thinking about the redemptive and reformist possibilities of design in relation to a modern citizenship (and economy) that were rehearsed at Kensal House and in ventures such as the Building Centre. A more immediate impetus was the belief, echoing the words of W.E. Williams in the Picture Post cited above, that the war had effected a decisive shift in the people’s sensibilities. Writing in 1956, the industrial designer Milner Gray observed that ‘The impact of war on millions of young people has engendered a quite different, more casual, more experimental attitude to life.’Footnote105 These two influences fed into a set of Council practices which again centred around the creation of environments rich in opportunities: the presentation through forms of display and exhibition, examples of ‘good’ design.

For the first ten years of its existence, such a policy manifested itself primarily through publications (including its own magazine, Design, first published in 1949) and, most emphatically, its 1946 exhibition ‘Britain can Make It’, held at a Victoria and Albert Museum still empty, having had its exhibits removed for safekeeping during the war. A series of displays introduced visitors to the idea of industrial design and the industrial designer, as well as showing them the sort of goods that could arise from collaboration between designers and industry, often using some of the material innovations that had come about in wartime. It was visited by 1.5 million visitors over 14 weeks.Footnote106 The Council also contributed extensively to pavilions and displays at the Festival of Britain such as that for Homes and Gardens.

Such work represented the conviction that, as yet, British industry had neither the well-designed goods nor sufficient progressive manufacturers to offer more than a sign of things to come. By 1956, however, it was felt that the time had arrived to move the CoID’s expository work to a more permanent footing; there were sufficient articles of ‘good design’ on the market to warrant a permanent display. Thus on 26 April 1956, at 28 Haymarket, London, just off Piccadilly Circus, the Council opened what it called the Design Centre. This served both as its headquarters and a space for display of contemporary British design & changing themed special displays (the first was on textiles).

It is hard not to see the choice of nomenclature as deliberate. Functionally and conceptually this was a purpose-built hybrid of the centre-idea as rehearsed in the pre-war Building Centre and Housing Centre, while spatially, as at the Pioneer Health Centre, its interior was marked by its openness and transparency (). Arranged across a lower and upper ground floor, and a first floor, visitors were presented with design as information (or instruments of health). This was a disinterested, or in CIAM’s term ‘impartial’ space, signalled by the Centre’s slogan ‘Look before you shop’. Thus the objects were complemented with an information counter and later the Council’s Design Index: a system that documented products with a photograph, sample and relevant information ().

Figure 8. The Design Centre: interior (Design Council Archive, University of Brighton Design Archive, DCA1708).

Figure 9. The Design Index (Design Council Archive, University of Brighton Design Archive, DCA3156).

Like the Building Centre and the Housing Centre (which was a stone’s throw away), the Design Centre was situated on a busy thoroughfare not far from the centre of government (). Gordon Russell recalled that although it was housed within ‘a new and ugly building’, it was ‘on an almost perfect site, in the heart of the West End of London about 150 yards from Piccadilly Circus,’Footnote107 Paul Reilly noted additionally that the site was chosen for the footfall it could guarantee as well as the fact that it had a bus stop directly outside.Footnote108 The elevation to the street (designed by Ward and Austin, the interiors were by Robert and Roger Nicholson, both employed by the Ministry of Works) had large plate glass windows and entrance doors, in order to attract the public inside. The Council’s Chair, W.J. Worboys, invoked the spirit of the Pioneer Health Centre in his characterization of the new Centre not as ‘a museum … it is a living, active, moving thing’, while the managing director of William Perring & Co. Ltd commented at the opening that it would mean ‘the retailer will benefit from a design and quality conscious public.’Footnote109 Such a sentiment also echoed Sert’s observation in 1951 that city planning should ‘ … start with the place where the people have to meet, where the people have to exchange ideas, where the people know what planning and other things mean to them’.

Figure 10. The Design Centre: façade to Haymarket (Design Council Archive, University of Brighton Design Archive, DCA 1707).

Similarly ‘living’ and ‘active’ was the South Bank Arts Centre. As noted above, the 1943 County of London Plan had designated the South Bank as ‘the logical position for a great and modern expansion of the capital’, with the more specific function of being ‘a great cultural centre’, which would add to its ‘civic aspects as a capital.’Footnote110 This was a complement to the many references throughout the Plan to other forms of centre (community, social,) as intrinsic to reconstruction. The Royal Festival Hall was but the first phase of this development. Once the Festival of Britain was over, efforts resumed on completing what the Plan had described as a centre that included ‘ … amongst other features, a modern theatre, a large concert hall, and the headquarters of various organisations.’Footnote111

The LCC’s Comprehensive Development Area plans for the area, published early in the 1950s, were ambitious and envisaged a national theatre, air terminal, exhibition centre, office buildings, an exhibition gallery linked physically to the Festival Hall, promenades and open spaces around the Hall, as well as pedestrian links to Waterloo Station.Footnote112 These plans would ultimately be scaled down but, with discussion about the site continuing during 1954-55, the LCC’s wider Development Plan was approved by the Ministry of Town and Country Planning in March 1955.Footnote113 In December 1955, the LCC concluded that a new concert hall should be built adjacent to the Festival Hall; initial plans for an art gallery were also in hand.Footnote114 As a project, however, the scheme had a particularly prolonged genesis, due, in part, to the complexity of negotiations between the LCC and the Arts Council.Footnote115 Building did not begin until the early 1960s, and what was called the South Bank Arts Centre (SBAC) was only completed in 1968 (by which time the LCC had been superseded by the Greater London Council, GLC).Footnote116 Designed by the LCC/GLC Architect’s Department, the Centre comprised the Queen Elizabeth Hall and the Purcell Room, for the performance of a wide classical repertoire and for chamber music respectively, and the Hayward Gallery. The Hayward was built to house exhibitions organized by the Arts Council from its own collection as well as touring exhibitions, and was designed in close association with the Council as a result. It contains five galleries of different sizes clustered around a central service core with three outdoor sculpture galleries.

A constant aspect of the centre-idea was its relation to a periphery and the dissemination and repetition of an ur-centre. We showed previously how the Peckham doctors hoped their original centre would be replicated and the way that both the Building Centre and Housing Centre distributed information from a headquarters base. The Festival of Britain’s South Bank was, as noted, the ‘heart’ of a national Festival while the Design Centre pursued a practice of disseminating standards through its publications (and later the Design Council ‘approved label’) and by the opening of Centres elsewhere: a Scottish Design Centre was opened in 1957 at 46 West George Street, Glasgow, while some English regions had permanent design exhibitions run in conjunction with local Building Centres.

Underpinning the reconstruction of the South Bank site was, then, the idea that it was a means to re-position London as the ultimate centre of a reconfigured and reconfiguring nation which had a cultured, vibrant citizenry at its heart. The scheme would ‘turn the South Bank into a part of London that is alive both night and day - a centre of the arts drawing diverse audiences and offering a choice of entertainments and attendant amenities.’Footnote117 The Arts Council in 1959 described the proposals as ‘bringing into existence an Arts Centre that is worthy of the capital city of Great Britain and the British Commonwealth.Footnote118 The inclusion of national cultural buildings (one for film, one for theatre, as well as a gallery for the national arts organization, the Arts Council) reiterated this idea, while the inclusion of the air terminal (although unrealized) as well as other transport links signalled an understanding of the site as connected at a series of levels, from the local to the international.

Discussion of the SBAC has tended to focus on aspects other than its Centre-ness. Brandon Taylor observes that the name ‘South Bank’ was chosen for its echoes of the Parisian ‘Left Bank’.Footnote119 He also notes the ‘nationalist nomenclature’ of the individual buildings which reiterates the idea of an English standard that would flow outwards to the nation and Commonwealth. Like Christopher Grafe, Taylor sees the architecture of the Centre buildings as representative of a stylistic shift that signalled a more profound distancing from what Taylor calls the ‘bourgeois public sphere’ of the Festival Hall.Footnote120 Grafe argues for the complex as transitional and that typologically, stylistically and in terms of programmatic organization, the SBAC avoids direct lineage to RFH.Footnote121 The suggestion here is otherwise: that the SBAC is as conceptually linked to the Festival Hall (and previous iterations of the centre-idea) as it is physically connected to it by the walkways around which it is built. Here is an agglomeration of functions, ‘completed’ a decade later by the National Theatre, that work as a cultural complement to the seat of democratic government across the Thames at Westminster. They are a centre from which excellence emanates. Spatially, we might understand the SBAC as a jazz riff on key centre-idea motifs of foyers, promenades and settings which are designed to be furnished by people and their actions; remove the exterior walls from the Festival Hall and there is the layered interconnecting environment of the riverside site. Finally, although the so-called Brutalism of the SBAC’s architecture can be read as a riposte to the New Monumentality of the Festival Hall, its use of exposed concrete, and, in particular, the use of mushroom columns throughout, is surely a continuation of architectural homages to the ur-centre, the Pioneer Health Centre, as one of its architects, Warren Chalke, noted in his 1967 account of the design ().Footnote122

Conclusion

In the two parts of this article we have charted the genesis and evolution between the 1920s and the 1960s of what we have termed the centre-idea. This was an environment typically bringing together a range of functions, either within one building or a complex of buildings, in an urban or rural space, which created a setting for ‘people and their actions’ and which, through this interface, was understood to effect new forms of human relationships and subjectivity suited to a democratic and increasingly post-imperial modernity. We have seen that this idea had its roots in the British voluntary sector and had its original formation in the activities of the Peckham Experiment. The concept was disseminated through reformist networks which transcended professional boundaries, and was embraced by the public sector during the Second World War and its aftermath. As pre-war reformers became post-war legislators and practitioners, the centre-idea was embedded in modernist architectural practice and post-war British planning.

We have also shown how an idea that originated in an English socio-medical context was able, through associational networks (or ‘zones of mutuality’) to connect first with the British modernist architectural community and thence to the European and North American avant-garde that constituted CIAM. Evidenced by the invitation to George Scott Williamson to speak at the organization’s eighth Congress, we have suggested that the centre-idea was integral to the re-orientation of modernist praxis more widely from the mid-1940s onwards, shaping not just post-war public architecture in Britain, but that of western democracies more widely also. The idea was flexible, transcending institutional arrangements and funding mechanisms but always rooted in a view of the collective, and the individual’s place within that community. Ultimately, it would enable and transform its users, in terms of better bodily health, expanded cultural horizons, or greater community-mindedness in place of individualism. It was thus an expression not simply of wider concerns relating to the contemporary city, but also the contemporary nation, being, ultimately, the embodiment of an evolving contemporary democracy and a bulwark against the emergence of the Iron Curtain.

The story of the centre-idea does not quite end here, although, as society became more atomised, affluent, and commercially focused, the idea that the built environment might ‘transform’ its users into a particular kind of citizen was challenged during the last decades of the twentieth century not only by the evidence of actual practice but also by growing scepticism of state paternalism. Nonetheless, there are parallels between the centre-idea and the theories developed by the architects who formed Team 10, the group which supplanted CIAM, whose members who saw the city as formed from a series of associations (and as a setting for them). Meanwhile, across Europe, as Kenny Cupers has shown, the cultural centre was a key post-war building type.Footnote123 In a British context, there are continued echoes of the centre-idea in key projects of the 1960s and 1970s. Cedric Price and Joan Littlewood’s ‘Fun Palace’ proposals, for example, comprised an open structural frame into which volumes containing activities from car maintenance to theatre were to be slotted. The Fun Palace was open, almost facade-less; its structural frame placed these activities on clear view, inviting participation and self-discovery. The proposals remained unbuilt in their original form (although they inspired the Centre Culturel Georges Pompidou in Paris of 1971-7, surely a further progeny of the Pioneer Health Centre.) Nonetheless, the centre-idea was also present in the many new subsidized civic and repertory theatres which were built from the end of the 1950s, and with the arts centres which sprang up during the following decades.Footnote124 In particular, the final piece of the LCC’s 1953 vision for London’s South Bank was the construction of the National Theatre (begun in 1963, and opened in 1976). It formed the final part of the conversation among the SBAC, Festival Hall and the Pioneer Health Centre, with the National‘s layered section, inside/outside foyers intended as a setting for people, and béton brut all linking back to that first building on St Mary’s Road, Peckham, of 1935 (). There are resonances, too, with the new leisure centres of the 1960s and 1970s. For example, Billingham Forum, near Stockton-on-Tees, completed in 1968, was the vision of a wealthy local authority which viewed leisure as an essential part of their ‘design for living’.Footnote125 A focal point within Billingham’s modern town centre, the Forum combined facilities for sports and the arts: everything from a modest theatre to a full-size swimming pool and spaces for bowls, drinking, and dancing. The interior spaces opened one to the next, with vistas between the different areas. Similar centres followed. The Arts and Leisure centre in the Hertfordshire new town of Stevenage (1976) also mixed sport and the arts; a walkway through the core of the building between the railway station and town centre provided deliberate glimpses of activity. Meanwhile the Magnum Centre in Irvine new town, Ayrshire (1976), offered a very deliberate recapitulation of the thinking that has been at the core of this article. Running between the sports halls, swimming pools, ice rink and theatre were ‘public concourses’, intended to connect back into the town centre megastructure and understood by the Development Corporation as ‘a large viewing gallery from which most of the activities can be seen.’Footnote126 They concluded that this arrangement would promote ‘the full benefits of the leisure centre … a bringing together of all ages and interests.’ Now translated to 1970s Scotland, here, once more, we have the ‘interfacial membrane’ of the Pioneer Health Centre.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Jessica Kelly and to Alborz Dianat for sharing their work with us prior to publication and to Dr Harriet Atkinson for her help with illustrations. We would also like to thank the four anonymous referees for their helpful and enthusiastic comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Elizabeth Darling

Elizabeth Darling is a Reader in Architectural History at Oxford Brookes University. Her research focuses on gender, space and reform in the 1890s-1940s, and the genesis and nature of English modernism. Recent publications include AA Women in Architecture 1917–2017 (2017) and Suffragette City: Gender, Politics and the Built Environment (2020). Her current research focuses on networks of women urban reformers in Edwardian Edinburgh, and on the architecture and design of BBC Broadcasting House.

Alistair Fair

Alistair Fair is a Reader in Architectural History at the University of Edinburgh, and a historian of architecture in Britain since 1918. His recent books include Modern Playhouses: an Architectural History of Britain’s New Theatres, 1945–1985 (2018) and Peter Moro and Partners (2021), while his current work includes research on the Scottish new towns pro- gramme, the idea of ‘community’ in twentieth-century Britain, and the architecture of post-war Edinburgh.

Notes

1 For the first part of the discussion, see Darling and Fair, ‘“The Core” … Part One’.

2 https://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/imtjames.asp accessed 17th March, 2022.

3 Madge, ‘Workers’ Life’, 10.

4 Huxley, ‘Changing Britain’, 8.