ABSTRACT

This article examines the infrastructural histories and legacies of three transnational corridors centred on the Mozambican cities of Maputo, Beira and Nacala. Underpinned by physical infrastructures, corridors were central to the extractive European colonial enterprise in Africa. Corridors facilitated the flows of resources, goods and knowledge between metropoles, African urban centres, and their hinterlands. Nowadays, corridors insert African cities and regions into global circuits of capital that perpetuate past extractive practices and policies. They are also powerful imaginary spaces for advancing political projects and developing specific configurations of government. Accordingly, the idea of a corridor may remain useful over time even as claims for their economic necessity ebb and flow. In this article, we examine the continuities between three contemporary Mozambican corridors and older colonial transitways that connected the three cities to British colonial interests in southern Africa. Then, drawing on Laclau and Mouffe’s discourse analysis, we suggest that corridors can serve as ‘empty signifiers,’ becoming linked to diverse understandings, standing for fluid yet enduring ambitions of connectivity, competitiveness, and regional integration. After scrutizing recent investments in the corridors, we reflect on their role in constructing a ‘new’ Mozambican economic order that is nevertheless deeply entangled in the country’s past.

Introduction

Corridors have long played a key role in the production and maintenance of the infrastructural state,Footnote1 underpinned as they are by specific physical infrastructures (e.g. railways, roads, ports, pipelines), legal apparatuses (e.g. concessions, exception regimes) and enclaved forms of spatial development (e.g. special zones). In Africa, infrastructure corridors were key to the extractive European colonial enterprise. Corridors enabled racial capitalism, and the exploitation of African populations and environments, by facilitating flows of resources, goods, and knowledge between metropoles, African coastal urban centres, and their hinterlands. Colonial administrations routinely masked the infrastructural violence of corridor projects by advancing now discredited claims about the unproductiveness of African land and labour and the need to create markets, spur industrialization, and promote progress and civilization in African territories. Nowadays, corridors remain central to the twenty-first-century African economy. Postcolonial governments continue to deploy corridors as essential to insert African cities and regions into global circuits of capital and commodities. Indeed, recent corridor developments have been lauded as the key to unlocking Africa’s potential and creating win-win conditions for more inclusive economic development.Footnote2 As in the past, local organizations and communities often refute and resist these claims, as corridors perpetuate past extractive policies and practices for the sake of state-building and regional cooperation.

This article explores the persistence of corridors as infrastructural tools through the notion of an ‘empty signifier’: a free floating container of multiple meanings, histories, and practices.Footnote3 The concept makes it possible to explain how certain words or phrases acquire political importance, and how ongoing political struggles seek to establish the definition of certain terms, giving them relevance for social processes.Footnote4 As claims for their economic necessity and appropriateness ebb and flow, corridors can harbour different meanings to different actors, helpfully organizing their conflicting interests and concerns, while pointing to a desired future of economic development and progress that may support some but exclude others. In other words, corridors remain powerful imaginary spaces for advancing disparate and even conflicting political projects and specific configurations of government and state-society relations. Tracing the infrastructural histories and discursive framings of a corridor can reveal much about such imaginations, their traction and staying power, along with the spaces for political intervention they afford.Footnote5

Our understanding of empty signifier draws on wider conceptions of discourse as proposed by theorists such as Laclau and Mouffe, Foucault, Saussure and Derrida. Such approaches emphasize the importance of discourse for reality construction while highlighting the connection between language, knowledge and power.Footnote6 We emphasize four related dimensions of discourse in our analysis. First, following a constructivist view, things do not have inherent meaning that can be captured by words; instead, meaning is constructed through mediating concepts, or ‘signifieds.’Footnote7 Second, discourse is primarily a social practice that brings together elements into relational systems that can be signified. Third, words, or social, cultural, natural or physical things, are all ‘radically contingent,’ meaning that they have ‘no fixed essence or full identity,’ but can be developed and reinterpreted ‘in different ways by competing forces.’Footnote8 Accordingly, meanings have fluidity and can never be entirely fixed, opening space for continued struggle over definitions of society or identity and for the emergence of counter-hegemonic narratives.Footnote9 Such a perspective is useful for analysis of infrastructural processes as it offers insights into the ways that storylines evolve and compete to become partially fixed, or hegemonic, allowing meanings to permeate and gain socio-political significance.Footnote10

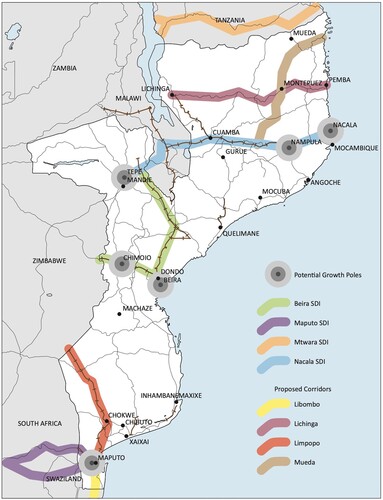

This article examines the infrastructural histories and legacies of three contemporary transnational corridors centred on the Mozambican coastal cities of Maputo, Beira, and Nacala (). It looks at how the three corridors represent a layered set of ambitions in colonial and postcolonial Mozambique that have deeply structured the country’s economic geography to date. The article starts with an overview of the role played by corridors in Africa and how they are justified through lofty ideals of connection that often have deeply exclusionary effects. It proceeds to contrast the colonial and postcolonial ambitions for the Mozambican territory and the role played by corridors in the construction of a ‘new’ Mozambican economic order that is, nonetheless, deeply entangled with the country’s past. We then examine each corridor in turn, followed by a discussion of their relevance for thinking through corridors as empty signifiers. The article draws on several phases of qualitative social science research conducted by the authors since 2012, and on the review of secondary literature, archival records, official reports, working papers and other materials available online, including local and national news reports and websites of the three contemporary corridor initiatives analyzed in the study.

Corridors and development in Africa

While the idea of economic development corridors may be a creation of the late 1990s and early 2000s, notions of linear development have a long history.Footnote11 For instance, the development of the railways in the nineteenth-century transformed transnational connections between urban hubs as transport and trade nodes on a much larger scale. In much of Africa, as in other colonized territories, railways were the ultimate extractive ‘tools of empire’.Footnote12 In postcolonial Africa, railways became key to the consummation of the ‘infrastructural state’,Footnote13 although at times only symbolically. Indeed, enhanced freight connectivity through combinations of transport infrastructures – rail, roads, ports, and airports – are now key to the African economy, as well as across the world. Development corridors connect spaces of extraction to spaces of consumption through myriad nodes and spaces of exception (e.g. special economic zones, industrial enclaves, etc.).Footnote14 In doing so, corridors create uneven geographies of development, fragmented territories managed by complex assemblages of public and private actors, whose aims rarely consider the needs of local communities and instead privilege extractive capital accumulation and short-term economic growth goals.Footnote15

In many respects, contemporary development corridors in Africa are reiterations of older imperial projects, especially those underpinned by railway infrastructures. Enns and Bersaglio suggest that ‘visions and territorial plans of colonial administrators are reappearing in visions and plans for these new mega-infrastructure corridors today’ underpinned by old imaginations of connectivity.Footnote16 Postcolonial infrastructure projects seem to reinstate and revise the imaginaries of older imperial projects designed to connect and integrate Africa in a relationship of dependency with Europe. In fact, as Hansen and Jonsson argued, the geopolitical reorganization that emerged after World War II – which would later culminate in the EEC/EU – was seen initially as the integration of continental European countries and their African ‘possessions’ in a single Eurafrican common market space.Footnote17 African natural resources were essential not just to the post-war reconstruction effort in Europe but also to the ascendancy of the European bloc as a player in the Cold War.Footnote18 As independence unfolded across the African continent, the Eurafrican project gave way to a new (neo-colonial) project underpinned by various trade and aid conventions (i.e. Yaoundé and Lomé Conventions).Footnote19 Substantive investment under these conventions went to the building of infrastructures through the European Development Fund (e.g. roads, railways, schools, hospitals), and to investments in agricultural development and some industrialization.Footnote20

Nowadays, development corridors continue to capture the attention of many African governments and the global development community under the ambition that corridors can not only improve connectivity but also deliver social and economic development. As Enns argues, ‘[t]he corridor agenda has been constructed on the imaginary of a seamless Africa, as new corridors are promised to enable flows of capital, commodities and people to circulate with ease across space and between scales.’Footnote21 Alongside the desire for ‘shiny new cities’,Footnote22 corridors encapsulate the interest of African political and economic elites to partake in and benefit from the latest global scramble for Africa’s natural resources in ways that perpetuate extractive and exclusionary practices. Examining the infrastructural histories of corridors, how they have been imagined and implemented by colonial and postcolonial governments, is thus a helpful way to think through how African populations have experienced different forms of connection and disconnection over time.

Colonial corridors in Mozambique

Corridors have been central to the political economy of Mozambique since colonial times. Arguably, the infrastructural histories of the three corridors examined in this article – Maputo, Beira and Nacala – are grounded in commercial and migration routes of diverse ethnic groups that precede colonial occupation.Footnote23 These routes, via land and river transport, connected the resource-rich hinterland regions to the Indian Ocean and from here to the Arabian Peninsula and the East.Footnote24 Portuguese colonial interests, as well as those of other European nations, notably British, repurposed these corridors to the service of an extractive economy, mostly by building new roads and railways. The Maputo corridor supported the mining operations in the South African Transvaal, while the Beira and Nacala corridors underpinned British farming interests in southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and British Nyasaland (now Malawi), respectively.Footnote25 Before examining the histories of each corridor and the ways they have been discursively framed, implemented and contested, we first review the broader ambitions of colonial and postcolonial policies towards the Mozambican territory and their articulation with investments in large-scale infrastructures along these corridors.

Colonial ambitions: Portugal’s peculiar ‘Eurafrican’ project

The three corridors were of essence to the Portuguese colonial enterprise in Mozambique, especially after World War II. Various authors have debated the nature of Portuguese colonialism in East Africa, offering explanations that range from seeing it as a symbolic project of preserving Portuguese political pride vis-à-vis dependency on Britain,Footnote26 to underscoring the strong influence of parochial metropolitan economic interests,Footnote27 or emphasizing a complex set of socio-economic, spatial, and political motivations.Footnote28 Despite their differences, all concur in the intensification of Portuguese presence after the war, a process that sought to implement a peculiar post-war ‘Eurafrican’ project, if not in practice at least on paper.

As noted earlier, the geopolitical reorganization that emerged after World War II led European nations to forge concerted connections with African territories. However, Portugal remained thoroughly suspicious of this integration project. Having gone through WWII formally as a neutral nation, Portugal sought to protect its African colonies in the post-war period. Post-war reconstruction and the winds of change it would unleash with the first wave of decolonization unsettled the stability of the Portuguese Empire. Salazar, Portugal’s Estado Novo dictator, initially refrained from engaging with the Marshall Plan or the European integration project for fear of becoming enmeshed in geopolitical dynamics that lay outside the regime’s control.Footnote29 Instead, in 1951, Salazar proposed a new geopolitical integration project of its own: a vision of a pluricontinental Portugal, with its European territory joined by its African and Asian territories in a single, integrated economic and political bloc. This was Portugal’s own brand of the ‘Eurafrican’ project. This new political integration retained the fantasy of Portugal as a great nation with a civilizing mission, an imaginary that obscured the regime’s brutal oppression and injustice.Footnote30 This territorial integration was not new insofar it was a reformulation of the regime’s propaganda from the onset of the Estado Novo in 1933. A now infamous map by the propaganda services, dated 1934, claimed Portugal ‘was not a small country’ (). As noted by Cairo, this form of representing disparate territories in a single map was a way of presenting the spaces of empire as coinciding with the space of a single nation – albeit a pluricontinental one.Footnote31 The map thus framed imperial Portugal’s geopolitical ambitions for its two largest African colonies, underscoring their vast territorial extension as juxtaposed on European territory, with attendant possibilities for resource exploitation.Footnote32

Figure 2. ‘Portugal Não É Um País Pequeno [Portugal Is Not a Small Country],’ map by Henrique Galvão, 1934 (Source: Cornell University Library Digital Collections, Persuasive Maps – PJ Mode Collection, available from: https://digital.library.cornell.edu/catalog/ss: 3293851, accessed on 21 May 2020).

![Figure 2. ‘Portugal Não É Um País Pequeno [Portugal Is Not a Small Country],’ map by Henrique Galvão, 1934 (Source: Cornell University Library Digital Collections, Persuasive Maps – PJ Mode Collection, available from: https://digital.library.cornell.edu/catalog/ss: 3293851, accessed on 21 May 2020).](/cms/asset/10be7f72-e015-4978-bab5-25f9e1721e6c/rppe_a_2173636_f0002_oc.jpg)

Through this ideographic and political project, the Estado Novo regime sought to bring the African colonies – now designated as ‘overseas provinces’ – even closer into the metropole’s sphere of influence, serving the interests of its economic elites and political regime.Footnote33 Driving this project were four economic development plans (Planos de Fomento), implemented from 1953 and until 1974, when the dictatorship crumbled under the weight of its internal economic and political contradictions and the African liberation wars. These plans foresaw economic integration through settlement of white population in the provinces, focused largely on agricultural development. Planners loosely modelled this approach on similar initiatives elsewhere – including the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) in the U.S. of the 1930s, South Africa’s Integrated Vaal River System, and mid-century regional planning doctrine applied in developing states.Footnote34 In practice, the plans sought a slow pace of development with only modest industrialization, for this was seen as potentially disruptive to the regime.Footnote35 According to Pereira, investments in the overseas provinces were under a third of the total investment budgeted, with Angola and Mozambique absorbing c. 85-90% of the investment across the four plans.Footnote36 In Mozambique, these investments were geared towards transport and communications infrastructures in the three corridors – Lourenço Marques (Maputo), Beira and Nacala – with a view to strengthening the transit/service economy.Footnote37 Funds flowed to ports and railways, along with roads and airports, all aimed to facilitate white settlement and to overcome territorial disconnects while improving prospects for trade and mobility, a key Portuguese concern from 1964 onwards due to the liberation wars waged by Frelimo.

Despite the intentions, the plans faced multiple challenges in execution. There was resistance not only from metropolitan interests but also colonial administrations, interested in preserving their turf and status, as well as maintaining as much autonomy from the metropolitan government as possible.Footnote38 Moreover, these plans required the development of a specialized knowledge base (e.g. baseline data, surveys, maps, etc.), which was unavailable at the time.Footnote39 Through this process of better knowing the territory, Portuguese experts (particularly social scientists) developed a deeper understanding of the oppression, exploitation and uneven development experienced by African populations.Footnote40 Concurrently, these infrastructures were targeted by Frelimo’s forces: roads and railways were sabotaged, especially along the Nacala and Beira corridors, rendering these infrastructures unusable for long stretches of time.

While the Portuguese occupation ended in 1974, the imaginaries underpinning the infrastructural projects at the service of a peculiar ‘Eurafrican’ project lived on. We now turn to the way these old imaginations of connectivity persisted in the post-colonial period, albeit under different guises.

Post-colonial ambitions: the same old service economy in new bottles

In post-colonial times, corridor projects in Mozambique retained the purpose of facilitating the service economy to neighbouring countries. Indeed, despite its deficiencies and periods of interruption, Mozambique remains a provider of transport services to landlocked countries – such as Eswatini, Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and even parts of South Africa and DRC – linking them to the Indian Ocean seaports and markets beyond. Railway and road links extend inland from the ports of Maputo, Beira and Nacala, operating as nodes and conduits in regional and worldwide movements of natural resources and all types of consumption goods.Footnote41

While these transnational movements betray enduring colonial practices, investments in corridor projects have adopted novel rhetorical imaginations. This is especially the case of development corridors, which – as a concept and a practice – are nowadays intricately connected with ideas of tapping into ‘productive synergies’ across regional and national transport systems and the broader national productive base.Footnote42 These claims are based on a model introduced regionally by South Africa in the late 1990s through its Spatial Development Initiative (SDI), a part of Mandela’s post-apartheid Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) programme.Footnote43 GEAR sought to reintegrate South Africa into the global economy, while aligning it with the shift to neoliberalism then sweeping across Africa. More specifically, SDI projects were aimed at supporting South Africa’s natural-resource export-oriented economy by removing obstacles to large-scale investment and promoting improvements in transport infrastructure, with the state operating as an enabler of market actors.Footnote44 This was to be achieved by attracting foreign investment and fostering public-private partnerships in areas with ‘under- or unutilized potential.’Footnote45 Such a framing drew on earlier ‘growth pole’ applications in South Africa, but with SDIs departing from previous inward looking, state-led regional policy designed to enforce apartheid’s system of racial restrictions.Footnote46 The Maputo Development Corridor, examined below, was one such project, given its potential to ‘unlock’ regional development opportunities in underserved northeast South African provinces and in southern Mozambique.Footnote47

The introduction of this model in Mozambique took place alongside broader political events of regional and global import. On the one hand, Mozambique’s 1992 peace accord that concluded a long-running civil war, the end of apartheid, and the first free elections in South Africa in 1994, all shaped possibilities and policies for transport along these corridors. For instance, the withdrawal of international sanctions and post-apartheid South Africa’s reinsertion in the global economy spurred the Port of Durban’s revitalization, which became a regional ‘transhipment hub’ for Mozambican ports from late 1990s onwards.Footnote48 On the other hand, other global transformations reverberated in Mozambique and continued to shape the narratives, political framings and practices underpinning infrastructure corridors. Structural adjustment policies, deregulation, and trade liberalization, for instance, led to the privatization of port services as well as other sectors of the economy.Footnote49

The stage was set for a corridor development approach to remain a key instrument of the infrastructural state in post-colonial Mozambique. Corridors became the physical manifestation of state and private-led efforts to accelerate short-term economic growth and trade liberalization through linking large scale investment projects in resource extraction or commercial agriculture and processing across a spatially demarcated area surrounding an infrastructural backbone of road and rail networks.Footnote50 Discourses around the importance of corridors remain key to mobilizing resources, at least among the political and business elites. They legitimise specific political-economic projects, and marshal capital and institutional support from the development community and private investors. While the technical aspects of these contemporary corridors have been well researched, their socio- political dimensions remain emergent and less studied. We explore these aspects for each of the three corridors next.

Contemporary corridors in Mozambique

The Maputo Development Corridor

The Maputo Development Corridor (MDC), founded in 1996 on a 500 km road and railway link connecting Maputo and Pretoria/Johannesburg in South Africa, draws on multiple historical connections dating back to the late 1800s. The MDC offers insights into the ways in which the sedimentation of different configurations of state-society relations along a geographical area provides the staying power for the imaginary space of a corridor.

The origins of the corridor date back to a road opened in 1874 connecting Lourenço Marques/Delagoa Bay (Maputo’s colonial designation) to Lydenburg (today’s Mashishing), then in the South African Republic. The road offered the new independent republic direct access to the port of Lourenço Marques/Delagoa Bay outside British control. Two decades later, in 1895, a railway connection was inaugurated connecting the port with Pretoria, thus consolidating the port town as key to the booming South African mining industry for decades to come. From the mid-1950s onwards, through investments made with the support of Portugal’s economic development plans, the railway line in Lourenço Marques was extended eastwards towards settler farming sites in southern Mozambique (Colonato do Limpopo/Chókwè) and northwards towards the industrial centre of Bulawayo in Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe). Investments in the port enabled the corridor to remain the gateway to international markets for South Africa, and an important source of foreign-exchange reserves for the colonial government in Mozambique.Footnote51 While remaining under direct control of the Portuguese colonial administration, this corridor was a key geopolitical asset in maintaining Portuguese presence in Mozambican territory, and in facilitating Salazar’s project of political and economic integration. In the post-colonial period and during the Mozambique civil war, the once important corridor suffered damage and neglect, forcing South African traders to develop alternative transport routes, mainly through their own ports at Durban and Richards Bay.Footnote52

The confluence of the end of Mozambique’s civil war and the end of apartheid ushered in a renewed focus on regional integration, strengthening the economic relationships between Mozambique and South Africa, as well as with Eswatini, albeit to a lesser extent. Under the auspices of SDI, the MDC was expected to deliver shared benefits, including rejuvenating mining, manufacturing, agriculture, logistics and tourism while advancing social and equity aims, such as redressing racial inequalities in business ownership in the Corridor region.Footnote53 Aligned with a neoliberal policy ethos, these benefits would be delivered through state-supported cross-border infrastructure development and by facilitating private-led investment to a total of 180 projects with an estimated value of US$7billion.Footnote54

In practice, the MDC project involved investment in a toll road connecting Maputo to Witbank, South Africa, including improvements to the border post at Ressano Garcia/Komatipoort.Footnote55 It also entailed improvements to the railway network in the southern Mozambique and the refurbishment of Maputo’s port facilities.Footnote56 In terms of business investments, the MDC foresaw the construction of several projects in Mozambique, including the Mozal Aluminium Smelter, the Pande/Temane gas pipeline, and the Maputo Iron and Steel project.Footnote57 In South African territory, the MDC facilitated the construction of an oil-from-coal plant at Secunda South, intended to stimulate South Africa’s petrochemicals industry.Footnote58 Finally, the MDC also promoted land suitable for export-oriented agri-food production spanning Mpumalanga and Maputo provinces.Footnote59

While there is some evidence that the MDC facilitated South African capital flows into southern Mozambique,Footnote60 several commentators have found that limited collaboration between different stakeholders has curtailed the corridor’s potential. Weak collaboration and interagency coordination have led to creating ‘enclave’ developments that were unable to spread benefits across sectors and localities.Footnote61 The MDC’s development has thus served to reinforce pre-existing capital markets on an axis centred on Gauteng and other smaller, non-contiguous regional hubs, generating limited employment and backwards and forwards linkages. Indeed, former white areas in South Africa have received most of the economic opportunities.Footnote62 Others have noted a tendency for public sector guarantees and tax breaks associated with the MDC to ‘crowd in’ external and South African private capital while ‘crowding out’ local development needs.Footnote63

Moreover, contradictions have arisen between the MDC’s goals of encouraging transnational private investment and the empowerment of local communities. Some developmentalist gains have emerged. Rogerson highlighted the Mozal aluminium smelter venture, located in an industrial park outside Maputo, as ‘changing the structure of [Mozambique’s] industrial base,’ while providing ‘a critical signal of private sector confidence in its economy and smoothing the path for future investment.’Footnote64 Nevertheless, ongoing corruption, neglect of local stakeholders, and the dominance of international capital have proven difficult to overcome.Footnote65 While some analysts have advocated examining these dynamics ‘from below’,Footnote66 the voices and histories of subaltern groups scarcely appear in the literature. The reproduction of colonial relations that foregrounded territories and sites of extraction while neglecting endogenous economic development are not sufficiently reckoned with. An exception is Dzumbira et al., who found the MDC ‘mainly acts as an import-export axis serving Gauteng and extracting industrial nodes such as eMalahleni (Witbank) and Ngodwana (Sappi) along the corridor.’Footnote67 Accordingly, they advocated greater state intervention and long-term investment in capacity building and skills transfer, especially in localities spatially distant from the Maputo-Witbank toll road, where positive spillover effects have been weakest.

Twenty-five years on, the MDC is often considered the most successful of the SDI projects initiated in the 1990s.Footnote68 Although the SDI programme continued under the New Growth Path policy that succeeded GEAR in 2011, the South African government began to withdraw support from the MDC in 2003.Footnote69 In 2004, a group of investors and service providers spanning the private and public sectors launched the non-profit Maputo Corridor Logistics Initiative, suggesting the staying power of the corridor in the region.Footnote70 Despite some unforeseen challenges, inefficiencies, and unequal trade flows, the corridor has provided a framework for subsequent cross-border political and institutional arrangements, including eliminating visa requirements and enacting new regional agreements easing travel and investment. While its effects continue to be debated, the waning of discussion and public discourse on the Maputo Development Corridor hints at its longer-term success, as the mobilizing narrative is no longer needed while the approach continues.

The Beira corridor

Whilst the Maputo Corridor has a consolidated history of both infrastructural and business investments, the nature of the Beira corridor has remained much less defined. In examining the lineage of infrastructural and business development of this corridor, we can more clearly distinguish how the idea of ‘corridor’ serves as an empty signifier for disparate ambitions.

Historically, the Beira corridor maps onto trade routes in central Mozambique, connecting the port town of Beira with the landlocked hinterland territories to its west, nowadays Zimbabwe, Zambia, Malawi and even beyond to DRC.Footnote71 In the colonial period, the area was under a royal charter concession to the Mozambique Company, which was initially set up in 1891 in Lisbon but came to be dominated by British interests by the 1910s.Footnote72 For the duration of the concession, until 1942, the Company led a largely extractive endeavour, based on African taxation and sub-concessions to plantation owners and mining operations.Footnote73 Underpinning these commercial efforts were a number of infrastructural investments: first, in developing the Beira port; second, in establishing a railway connection to Southern Rhodesia in 1900 (Machipanda Railway); and third, in rolling out another railway line linking Beira to Nyasaland in 1904 (Sena Railway), via the coal-rich areas of Tete (near Moatize). These railway lines were crucial to the production of cotton and sugar in central Mozambique, to coal extraction in the Benga-Moatize areas (Tete province), and to import-export activities between the port of Beira and the resource-rich hinterland areas controlled by British interests.Footnote74

As in the case of the Maputo corridor, these transportation corridors were also targeted by Portuguese improvements under the post-war economic development plans, especially in terms of road investments. Another significant investment in the region was the Cahora Bassa dam and hydroelectric power plant, concluded after Mozambique’s independence, which was to underpin a substantive agricultural development along the Zambezi River valley. These roads, railway, and power lines were also targeted by Frelimo’s liberation efforts in the 1960s-1970s, as well as by Renamo during the Mozambican civil war in the post-independence period and, more recently, from 2013 to 2017.Footnote75 Key infrastructures have since been revamped and upgraded with the support of donors and the multilateral financial institutions, largely spurred by the commodities ‘super cycle’ of the 2000s and the possibilities of profitable coal mining in Tete province (see ). Indeed, the coal boom motivated ambitious plans to promote agribusinesses as an additional development stream for Mozambique’s centre.Footnote76 However, their fulfilment has remained elusive, as it did with the Mozambique Company in the past.

Figure 3. Railway link near Moatize mine, Tete province, in the Beira Corridor (photo by J. Kirshner).

An example of these elusive promises is the Beira Agricultural Growth Corridor (BAGC). The BAGC was initiated in 2010 with a view to establish an ‘agricultural growth corridor’ in a vast area entailing the provinces of Tete, Manica, and Sofala and extending into Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Malawi.Footnote77 The initiative brought together in a public-private partnership format the Mozambican government, foreign investors, smallholder farmer associations, and international development agencies. Together, they were to promote a long-term development project that contrasted with, but also relied on, the region’s speculative investments in the extractive and processing industries.Footnote78

Early BAGC presentations, termed ‘blueprints,’ continued to rely on dubious narratives of ‘unproductive land’.Footnote79 They emphasized ‘greenfield investments’ on ‘over 10 million hectares of arable land available’ with ‘less than 0.3% farmed commercially.’Footnote80 Drawing on international agricultural advisors, BAGC’s blueprints hoped to catalyze commercial value chains of agribusiness investments in the region through agricultural zoning, input supply chains (fertilizer and seeds), investment in mechanization and irrigation, the building of storage silos and food processing facilities.Footnote81 These approaches emphasized economies of scale and locational clustering of firms to create competitive operations while enhancing connectivity.Footnote82 The initiative was underpinned by a Catalytic Fund, sponsored by donor agencies from the UK, the Netherlands, and others, to support pilot business development projects that promoted smallholder farmers and local communities.Footnote83 BAGC also spurred other programmes from the Mozambique government (e.g. SUSTENTA), international donor agencies such as USAID (Resilient Agricultural Markets Activity), or financial institutions such as the World Bank (PROIRRIGI).Footnote84 Overall, the proliferation of projects contributed to an image of dynamism in the region, as different entities sought to capitalize on the opportunity to expand commercial agriculture in an area considered Mozambique’s ‘breadbasket’.Footnote85

However, there is a shared sense among critics that the BAGC never achieved the coordinated framework for large-scale investments in agribusiness that its supporters envisioned.Footnote86 Despite gaining momentum at certain times, no major BAGC-linked foreign investments materialized. The resurgence of armed conflict in 2013 affected local livelihoods, thwarting investments and disrupting supply chains.Footnote87 The success of the corridor required active, high-level state engagement to attract investment in commercial agri-food ventures, but governing elites have shown historical disinterest in promoting large-scale agriculture schemes,Footnote88 notwithstanding frequently citing agriculture as a basis for development.Footnote89 The limited state-level support hindered the programme’s ability to adapt to changing regional conditions, such as demographic shifts, changing demands for services and growing climate disruption (e.g. 2019 Cyclone Idai), while the prolonged political-economic crisis in Zimbabwe has heightened these challenges.

Moreover, the transformative narrative underpinning the Beira corridor contrasted with local residents’ experiences, for whom land is far from empty but entails a wealth of lived experiences and aspirations being changed by BAGC’s proposed shifts in traditional farming practices.Footnote90 Indeed, the land availability figures draw on calculations unrecognized at the local level,Footnote91 but which may rely on insecure land tenure status among local communities.Footnote92

In sum, through the BAGC initiative and wider rhetoric of the corridor as an axis of connectivity, competitiveness, economic dynamism and regional integration, the Beira Corridor serves mainly as a mobilizing narrative circulating in governance networks since the late 1990s, rather than an actual spatial and socio-economic tool for regional planning and development. Accordingly, the corridor can only operate if the material and institutional connections, partnerships, and infrastructures are in place, which has proven elusive thus far. Despite the practical impediments to the BAGC, the discourse of corridor-enabled connectivity remains influential in the region, helping investors and elite groups mobilize capital and institutional support.

The Nacala corridor

Much like the Beira Corridor, the Nacala Corridor is a complex assemblage of initiatives focused on logistics and agribusiness-led economic development. It links the port of Nacala—one of the Indian Ocean’s deepest natural harbours—to fertile grounds in Nampula province, and through Malawi to resource-rich Tete province. As the two previous corridors, the Nacala Corridor has its origins in the colonial period, when a railway line first connected Nyasaland (Malawi) in 1915, not to Nacala, but to the port of Lumbo, near Ilha de Moçambique.Footnote93 It was only in 1924 that a new line connected to Nacala, after the port at Lumbo was deemed too limited for further expansion. Nacala port was first developed in 1950 with the construction of a deep-water berth on the site.Footnote94 It was linked by rail to the Lumbo-Nampula railway line, later extended to the Malawian border at Entre-Lagos, and then connected to Malawi’s rail system in 1970.Footnote95 In 1983, the railway closed to traffic following RENAMO’s repeated sabotage amid the civil conflict. The line reopened in 1987, but service languished for the next several decades until the 2010s, when a multilateral agricultural development programme, ProSAVANA, triggered efforts to revive the Nacala Corridor.Footnote96

Plans and protocols for ProSAVANA were rooted in an earlier agricultural project based in Brazil, which echoes familiar narratives of transformation of ‘empty,’ ‘unproductive’ lands, but also in ‘unlocking’ investment. The project, a three-way cooperation with Japan and the U.S. from the 1980s, aimed to transform the Cerrado grasslands—a vast tropical savannah on the Brazilian Plateau deemed ‘vacant’—into a productive agribusiness and agrofuel production frontier.Footnote97 ProSAVANA was established in 2011 as a rural development programme to promote a number of studies, skills, and technology transfer initiatives and credit concession arrangements to create an enabling environment for commercial agriculture along the Nacala Corridor.Footnote98 The initiative consisted of a public-private partnership comprising the Mozambican government, Japanese development finance, and Brazilian tropical agribusiness technical expertise and targeted 14 million hectares of land spanning 19 districts in Nampula, Niassa and Zambezia provinces.Footnote99 The Mozambican government also set up special economic zones (SEZs) adjacent to Nacala, as it did near Beira and Maputo, with further zones focused on agro-industrial activities planned along the corridors.Footnote100 However, much like BAGC, numerous initiatives have yet to materialize, such as the agroindustry clusters and logistics operations linking inland districts with ports, failing to catalyze economic development and poverty reduction.

Instead, by 2013, the ProSAVANA programme increasingly overlapped with plans for revitalizing the Nacala Corridor’s multimodal rail and port infrastructures to increase export capacity, particularly for coal from the Moatize mines, in Tete province. These plans were of particular interest to Vale S.A., the Brazilian mining company, which controlled the mines from 2004 to 2021, as well as to Japanese business interests that took up stakes in Vale’s coal operations in 2014.Footnote101 Through a new investment completed in 2016, extending 912 km, the corridor now provides a rail link between the Moatize mine and the coal export terminal at Nacala-a-Velha port on the Indian Ocean. Other investments included a Japanese government-funded upgrade to the Nampula-Cuamba road.Footnote102 Along the way, various private interests acquired thousands of hectares of land outside the purview of the ProSAVANA programme.Footnote103 The Nacala Corridor’s rhetoric of farming development reverted, once again, into the familiar realm of the extractive economy.

Considering developments over the last decade, conflicting views have emerged on the success of ProSAVANA and, by extension, of the Nacala Corridor. Some early studies found in ProSAVANA an innovative model for regional development through market-led agribusiness clusters and value chains targeting both domestic and international markets, especially in Africa and Asia.Footnote104 Other research has been more critical, some arguing that ProSAVANA has failed to deliver on its promises,Footnote105 while others see it as ‘neo-colonial’ South-South relations amid rising investment from the BRICS in Africa.Footnote106 Critics claim that ProSAVANA interventions along the Nacala Corridor have endangered land tenure for smallholders, threatened livelihoods and heightened pressures over land acquisitions through state- and private-led efforts to render land ‘investible’.Footnote107

Indeed, the initiatives around the Nacala Corridor have not been without contest. The ProSAVANA Master Plan leaked to the press in 2013, leading the Mozambican National Peasant Union UNAC (União Nacional de Camponeses) to decry the programme as a land grab that would dispossess smallholders and peasants in the region.Footnote108 UNAC’s intervention drew on the experience of Brazilian rural grassroots organizations, such as the Landless Rural Workers Movement MST (Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem Terra), who opposed the Cerrado initiatives at the heart of ProSAVANA.Footnote109 It is somewhat ironic that state-led South-South narratives of cooperative development are countered by South-South advocacy networks facing similar struggles despite different spatial and socioeconomic contexts.Footnote110 Overall, the corridor narrative can serve as juncture for debates over aspirations for development and justice alike.

While serving as a counterpoint to the Beira Corridor experience, ProSAVANA overlaps with BAGC in several ways. ProSAVANA deployed a similar ambition of opening-up green-field agriculture, or ‘unlocking’ empty spaces to spark economic dynamism, with the state granting exemptions from certain regulations to accelerate the process. We see that particular configurations of state-business relations in Mozambique and neighbouring states continue to shape the prospects for the Nacala Corridor, as it did for the Beira Corridor. In contrast to the Maputo Corridor, with its relatively dense and embedded infrastructural connections along its backbone and in the South Africa–Mozambique borderlands, the two more northerly corridors remain as partial and uneven bundles of infrastructure. Moreover, the growing Islamic State-backed insurgency in the gas-rich province of Cabo Delgado to the north of Nacala, in which 3,300 have been killed and 800,000 displaced, heightens the risk of operations in the two corridor areas.Footnote111 Overall, the notion of corridor development may be rhetorically appealing, but its endurance requires long term commitment from state actors to deliver on its many promises.

Discussion

The three corridors examined in this article – Maputo, Beira, and Nacala – have their own infrastructural histories rooted in Mozambique’s transit/service economy, each having emerged at particular moments in time and performing different roles. Conceived during Portuguese colonial rule amid wider efforts to govern and derive value from its overseas territories, the material realities of the corridors are uneven and their outcomes debatable. Yet the visions and narratives supporting the corridors have proved malleable and enduring, with meanings that are flexible and not entirely fixed, making it a powerful political tool.Footnote112 As such, the corridor projects have gained momentum at certain times, but their construction, financing and usage has been contested and not assured. We suggest, in line with Brown, that ‘corridor’ can act as a signifier that ‘gestures towards the failure(s) of signification itself,’Footnote113 thus reminiscent of what Ernesto Laclau termed an ‘empty signifier.’Footnote114 Some authors have emphasized an element of universality, or universal appeal, of empty signifiers, which can garner broad consensus.Footnote115 As such, ‘corridor’ can become linked to various, often diverse understandings, serving distinct interests or purposes, enabling or reinforcing hegemonic dominance while also opening possibilities for contestation and counternarratives.Footnote116 In the examples examined above, the corridor as empty signifier comes to embody, through its physical design and material context, a hegemonic vision of seamless connectivity for spaces with potentially high capital value. Yet, given the signifier’s ‘radical contingency,’ it becomes difficult to catalyze and stabilize it.

With investments committed through the Estado Novo regime’s economic development plans (1953-1974), grand infrastructural projects – e.g. ports, railways, roads, and airports – aimed to facilitate white colonial settlement in Mozambique’s interior and integrate territories while improving the prospects for trade and mobility. Linking these non-contiguous, often spatially isolated projects, the corridors were framed in discourses of connectivity between the metropole and overseas provinces, strengthening the service economy and increasing governance visibilities in nascent regions, or entrepôts, of investment.Footnote117 Above all, the emphasis was on consolidating an imagined, unitary Portugal, with echoes of the Eurafrican nations pursued by other European powers. Yet, these plans neglected endogenous development and local needs, in keeping with modes of colonial planning enforced by the Estado Novo.

Having attained political independence from colonial rule in 1975, Mozambique’s new, socialist ruling party, Frelimo, sought to harness key infrastructure for broad-based, socially egalitarian, national-scale development while adhering to long-cherished goals of economic growth acceleration, poverty reduction and transition from low- to middle-income status.Footnote118 By the early 1990s, Frelimo had abandoned the pursuit of a socialist, planned economy amid economic malaise and a long-running civil war and espoused neoliberal market integration.Footnote119 As noted, this shift coincided with Pretoria’s launching of the Spatial Development Initiative (SDI) in the wider region, offering an aspirational framework for enhancing transport infrastructure and resource extraction for export. Much as in the colonial period, the visions and plans associated with the corridors were performative of political-economic integration, but with a new emphasis on ‘global development’ reaching into the southern African region, ‘unlocking’ potential in underinvested localities, encouraging the involvement of large private-sector firms and SMEs alongside state support, with promises of equitable growth and prosperity through connectivity.Footnote120

Yet, despite concerted efforts, especially in the Beira and Nacala corridors, the plans never stuck, remaining disconnected from local realities, with little resonance for local people, and scant outcomes.Footnote121 As in the case of the Nacala Corridor, an active local resistance took root, drawing on a counter-narrative and South-South activism networks, based not on connectivity or ‘unlocking’ value, but on dispossession and displacement. The Maputo Corridor offers a counterpoint to the pattern of disintegration seen in the Nacala and Beira Corridors. Sitting atop multiple well-established and dense infrastructural connections linking Johannesburg and the Gauteng province to the Mozambique border and Maputo’s port, the Maputo Development Corridor was defined through the consolidation and upgrade of existing infrastructures to service a longstanding history of dense economic relations. One scarcely hears the ‘corridor’ discourse used to promote the subregion between Gauteng and Maputo in subsequent years—nowadays, the mobilizing narrative of the corridor is less needed.

The idea of the development corridor as a mobilizing narrative, however, continues to find receptivity, gain credibility and acceptance, and circulate within public-private governance networks in Mozambique, irrespective of whether there are material outcomes of notice. As we have shown, the Maputo, Beira and Nacala corridors each constitute, to varying degrees, imagined spaces situated beyond their respective anchoring cities, in need of narration, but also requiring hard infrastructure, such as toll roads, border posts and railways, viewed by investors and policymakers as catalysts for developing these subregions. We have suggested that in cases where such material infrastructure is uneven or lacking, tying projects to wider storylines and signifiers through corridor narratives can be an effective means of legitimizing construction, attracting investment and channelling it towards certain geographic areas, and thus an important political tool.Footnote122 Accordingly, corridor narratives can imbue such projects with diffuse and contingent meanings that garner support from investors, ruling party elites, supporting donors and other stakeholders.

Importantly, the breakdown of corridor initiatives has not brought an end to the political approach embedded within it. The process of political ‘infrastructuring’ remains central to state strategies deployed by Frelimo in Mozambique, and ruling parties elsewhere in Africa.Footnote123 Regardless of the risks and opportunities in relying on a form of market utopianism or the ‘promise of infrastructure’,Footnote124 investors and officials in Mozambique have shifted their attention to a new corridor iteration centred on heavy sands mining in Chongoene district, Gaza province, in Southern Mozambique.Footnote125 The Chongoene Development Corridor project includes a new deep-water seaport, a multipurpose freight rail line, installation of eco-industrial and petrochemical parks, and a free zone for agro-processing.Footnote126 This new ‘El Dorado’ is expected to attract an estimated US$7.2 billion in investment, nearly half of Mozambique’s current GDP.Footnote127 The idea is familiar: enhanced transport infrastructure and ‘anchor commodities’ unlocking the growth potential of this less-favourable area, with ‘corridor’ narratives inspiring investment.

Conclusion

In post-colonial times, development corridor projects in Mozambique – as a concept and a practice – are entangled with enduring ideas of mobilizing ‘unproductive’ lands and labour, tapping into ‘productive synergies’ between enhancing regional transport systems and supporting extractive economies and Mozambique’s broader productive base.Footnote128 We have argued that corridors can serve as empty signifiers, standing for fluid and malleable, yet also enduring ambitions of connectivity, competitiveness, economic dynamism, and regional integration, while obscuring the same forms of socio-spatial exclusion, violence, and exploitation that featured in the colonial past. Accordingly, corridors are discursively constructed in ways that encapsulate the interests of contemporary African political and economic elites to take part in, and benefit from, the latest global scramble for Africa’s natural resources in ways that perpetuate extractive and exclusionary practices. At the same time, corridors are presented as technical, apolitical projects, built in the interest of social and economic development, irrespective of their success in delivering benefits to local communities.

Development corridors have proved effective as a mobilizing narrative, spurring the interest of a range of investors, luring substantial financial capital and technical expertise, while adapting to different geographical contexts and becoming linked to multiple and diverse understandings. Concurrently, they offer a fluidity of meaning, under which a range of projects can be articulated, promoted, and linked together, often through idealized spaces. Yet, as the meaning of an empty signifier cannot be entirely fixed, this opens an avenue for contestation over these corridors, and the possibilities of counterhegemonic narratives and practice.Footnote129 While such opportunities gain momentum at certain times, this space is suggestive of the progressive and creative potential that corridors may hold amid ongoing territorial reconfigurations and their uneven effects on local communities.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the reviewers for their constructive criticism and support in drawing out the full potential of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Joshua Kirshner

Joshua Kirshner is Associate Professor in Human Geography in the Department of Environment and Geography, University of York. His current research explores relationships between resource governance, urban and environmental conflict, and the economic and political geographies of low-carbon transition.

Idalina Baptista

Idalina Baptista is Associate Professor in Urban Anthropology in the Department for Continuing Education, University of Oxford. Her current research interests focus on the colonial and post-colonial geographies of urban energy infrastructure and urbanization in African cities.

Notes

1 Mann, ‘The Autonomous Power of the State.’

2 Enns, ‘Mobilizing Research on Africa’s Development Corridors.’

3 Laclau and Mouffe, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy.

4 Wullweber, ‘Global Politics and Empty Signifiers;’ Howarth, ‘Power, Discourse, and Policy.’

5 Barry, Material Politics; Mitchell, Carbon Democracy.

6 Laclau and Mouffe; Howarth.

7 Yapa, ‘What Causes Poverty?’

8 Tafon, et al., ‘The Politics of Estonia’s Offshore Wind Energy Programme,’ 159.

9 Atkins, ‘Dams, Political Framing and Sustainability as Empty Signifier.’

10 Atkins.

11 Brunner, What Is Economic Corridor Development; Priemus and Zonneveld, ‘What Are Corridors.’

12 Headrick, The Tentacles of Progress; Headrick, Power Over Peoples.

13 Mann; Soifer, ‘State Infrastructural Power.’

14 Easterling, Extrastatecraft; Ferguson, Global Shadows; Ong, Neoliberalism as Exception.

15 Ferguson; Lesutis, ‘How to Understand a Development Corridor?.’

16 Enns and Bersaglio, ‘On the Coloniality of “New” Mega-Infrastructure Projects in East Africa,’ 2.

17 Hansen and Jonsson, ‘Imperial Origins of European Integration;’ See also Martin, ‘Africa and the Ideology of Eurafrica.’

18 Hansen and Jonsson.

19 Martin.

20 Mailafia, Europe and Economic Reform in Africa.

21 Enns, 106.

22 Côté-Roy and Moser, ‘Does Africa Not Deserve Shiny New Cities?’

23 There are more than 20 ethnic groups across Mozambique, and while some groups are dominant in certain regions, their mobility during the colonial period, not least as part of forced labour processes, makes it hard to associate them with specific corridors. Newitt, A History of Mozambique.

24 Newitt; Kaarhus, ‘Land, Investments and Public-Private Partnerships.’

25 Kaarhus.

26 Hammond, Portugal and Africa.

27 Clarence-Smith, The Third Portuguese Empire.

28 Alexandre, ‘A África No Imaginário Político Português.’; Newitt; Pitcher, Politics in the Portuguese Empire.

29 Pereira, ‘A Economia Do Império’.

30 Pereira.

31 Cairo, ‘Portugal Is Not a Small Country’.

32 In terms of relative size, Mozambique as demarcated in 1891 is 309,000 square miles in extent, with Angola 481,354 square miles and Portugal 35,560 square miles (Newitt). The number of Portuguese permantly settling in Mozambique in the late colonial period was relatively small. By the First World War, there were an estimated 10,000 Europeans in Mozambique (a figure that included many who were not Portuguese, along with administrators, soldiers and some convicts). By 1945, when regular censuses were being taken, the number had increased to just over 31,000, in part reflecting administrative expansion in the 1930s and 1940s. In total, between 1943 and the end of colonial rule in 1975, 164,000 Portuguese arrived in Mozambique. Despite large numbers returning or moving on to South Africa, this was the figure recorded in the 1970 census. See Castelo, Passagens para África, 97.

33 Pereira.

34 For example, Friedmann, Regional Development Policy.

35 Pereira.

36 Pereira, 252.

37 Pereira.

38 Pereira; Pitcher.

39 Newitt.

40 Pereira.

41 Perez-Niño, ‘The Road Ahead’; Meeuws, Mozambique — Trade and Transport Facilitation Audit.

42 Perez-Niño, 269.

43 Rogerson, ‘Spatial Development Initiatives in Southern Africa.’

44 Kaarhus; Taylor, ‘Globalization and Regionalization in Africa;’ Peberdy, ‘Border Crossings.’

45 Meeuws, 62; Rogerson.

46 Rogerson.

47 Rogerson, 326; Taylor.

48 Taylor, 323.

49 Pitcher, Transforming Mozambique; Taylor.

50 Kaarhus; Rogerson.

51 Newitt.

52 Rogerson.

53 Mitchell, ‘The Maputo Development Corridor.’; Rogerson.

54 Dzumbira et al., ‘Measuring the Spatial Impact of the Maputo Development Corridor.’; Rogerson; Taylor.

55 Dzumbira et al.

56 Dzumbira et al.

57 Dzumbira et al; Taylor.

58 Rogerson.

59 Rogerson.

60 Dzumbira et al; Mitchell.

61 Baxter et al., ‘A Bumpy Road.’; Söderbaum and Taylor, ‘Transmission Belt for Transnational Capital or Facilitator for Development?.’

62 Mitchell; Rogerson.

63 Söderbaum and Taylor, ‘Competing Region-Building in the Maputo Development Corridor’ 52; Nuvunga, ‘Region-Building in Central Mozambique’.

64 Rogerson, 336.

65 Söderbaum and Taylor; Söderbaum and Taylor.

66 Grant and Söderbaum, The New Regionalism in Africa; Söderbaum and Taylor; Söderbaum and Taylor.

67 Dzumbira et al., 644.

68 AfDB et al., African Economic Outlook 2015.

69 Dzumbira et al; Baxter et al.

70 Baxter et al.

71 Newitt.

72 Newitt.

73 Newitt.

74 Perez-Niño.

75 Smith, ‘The Beira Corridor Project.’; Muchemwa and Harris, ‘Mozambique’s Post-War Success Story.’; Vines, Prospects for a Sustainable Elite Bargain in Mozambique.

76 Coughlin et al., How USAID Can Assist Mozambique; Mosca and Selemane, El Dorado Tete.

77 BAGC, Beira Agricultural Growth Corridor.

78 Dzumbira et al; Mitchell.

79 Shankland and Gonçalves, ‘Imagining Agricultural Development in South–South Cooperation.’

80 BAGC, 9 and 12.

81 Byiers et al., A Political Economy Analysis of the Nacala and Beira Corridors; Gonçalves, ‘Agricultural Corridors as “Demonstration Fields”.’

82 ACB et al., Agricultural Investment Opportunities in the Beira Corridor, Mozambique.

83 Kaarhus.

84 Smalley and Gonçalves, Cyclone Idai Hits Agriculture in Beira Corridor: Preparing for the Future.

85 Gonçalves.

86 Kaarhus; Shankland and Gonçalves.

87 Kaarhus.

88 Buur et al., ‘The White Gold.’; Hanlon and Mosse, Mozambique’s Elite.

89 Kaarhus.

90 Stein and Kalina, ‘Becoming an Agricultural Growth Corridor.’

91 ACB et al; Kaarhus.

92 Smalley and Gonçalves.

93 Newitt.

94 Fair, ‘Mozambique.’

95 Fair.

96 Shankland and Gonçalves.

97 Clements and Fernandes, ‘Land Grabbing, Agribusiness and the Peasantry in Brazil and Mozambique.’; Wolford and Nehring, ‘Constructing Parallels.’

98 Clements and Fernandes; Wolford and Nehring.

99 Gonçalves.

100 Gonçalves.

101 England, Mitsui Invests $1bn in Vale’s Mozambique Coal Projects.

102 Gonçalves.

103 Gonçalves.

104 Collier and Dercon, ‘African Agriculture in 50 Years.’

105 Shankland and Gonçalves.

106 Alden et al., Mozambique and Brazil; Carmody, The New Scramble for Africa.

107 Goldstein and Yates, ‘Introduction: Rendering Land Investable.’; Selemane, A Economia Política Do Corredor Do Nacala.

108 Chichava et al., ‘Brazil and China in Mozambican Agriculture.’; Lagerkvist, ‘As China Returns.’

109 Shankland and Gonçalves.

110 Shankland and Gonçalves; Cezne, ‘Forging Transnational Ties from Below.’; Cezne and Hönke, ‘The Multiple Meanings and Uses of South–South Relations in Extraction.’

111 Morier-Genoud, ‘The Jihadi Insurgency in Mozambique.’

112 Crow-Miller, ‘Discourses of Deflection.’

113 Brown, ‘Sustainability as Empty Signifier,’ 115.

114 Laclau, On Populist Reason.

115 Despite some differences, the concept is similar to Lacan’s notion of master signifier and Barthes’ concept of myth. Wullweber, 80.

116 Laclau and Mouffe.

117 Ferguson; Mohan, ‘Beyond the Enclave.’

118 Newitt.

119 Pitcher.

120 Söderbaum and Taylor; Enns; Rogerson.

121 Gonçalves; Stein and Kalina.

122 Atkins; Brown; Crow-Miller.

123 Enns; Lesutis.

124 Appel et al., ‘Introduction: Temporality, Politics, and the Promise of Infrastructure’; Enns and Bersaglio.

125 Chilingue, Vem Aí O Novo ‘Eldorado’ De Moçambique Para Os Próximos Tempos.

126 Chilingue.

127 Mosca and Selemane.

128 Perez-Niño, 269.

129 Laclau and Mouffe.

References

- African Centre for Biodiversity, Kaleidoscópio and União Nacional de Camponeses. Agricultural Investment Opportunities in the Beira Corridor, Mozambique: Theats and Opportunities for Small-Scale Farmers. Johannesburg, South Africa, 2015.

- African Development Bank, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and United Nations Development Programme. African Economic Outlook 2015: Regional Development and Spatial Inclusion. Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, 2015.

- Alden, Chris, Sérgio Chichava, and Ana Christina Alves. Mozambique and Brazil: Forging new Partnerships or Developing Dependency? Johannesburg, South Africa: Jacana Media, 2017.

- Alexandre, Valentim. “A África No Imaginário Político Português (Séculos XIX-XX).” Penélope 15 (1995): 39–52.

- Appel, Hannah, Nikhil Anand, and Akhil Gupta. “Introduction: Temporality, Politics, and the Promise of Infrastructure.” Chap., In The Promise of Infrastructure, edited by N. Anand, A. Gupta, and H. Appel, 1–38. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018.

- Atkins, E. “Dams, Political Framing and Sustainability as an Empty Signifier: The Case of Belo Monte.” Area 50, no. 2 (2018): 232–239.

- Barry, Andrew. Material Politics: Disputes Along the Pipeline. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013.

- Baxter, Julia, Anne-Claire Howard, Tom Mills, Sophie Rickard, and Steve Macey. “A Bumpy Road: Maximising the Value of a Resource Corridor.” The Extractive Industries and Society 4, no. 3 (2017): 439–442.

- Beira Agricultural Growth Corridor. Beira Agricultural Growth Corridor: Delivering the Potential. Beira, Moçambique, 2010.

- Brown, Trent. “Sustainability as Empty Signifier: Its Rise, Fall, and Radical Potential.” Antipode 48, no. 1 (2016): 115–133.

- Brunner, Hans-Peter. What is Economic Corridor Development and What Can It Achieve in Asia’s Subregions? (Working Paper Series 117). Manila, Philippines: Asian Development Bank, 2013.

- Buur, Lars, Carlota Mondlane Tembe, and Obede Baloi. “The White Gold: The Role of Government and State in Rehabilitating the Sugar Industry in Mozambique.” Journal of Development Studies 48, no. 3 (2012): 349–362.

- Byiers, Bruce, Poorva Karkare, and Luckystar Miyandazi. A Political Economy Analysis of the Nacala and Beira Corridors (Discussion Paper No. 277). Maastricht, The Netherlands: European Centre for Development Policy Management, 2020.

- Cairo, Heriberto. ““Portugal is not a Small Country”: Maps and Propaganda in the Salazar Regime.” Geopolitics 11, no. 3 (2006): 367–395.

- Carmody. Pádraig. The New Scramble for Africa. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2016.

- Castelo, Claudia. Passagens Para África: O Povoamento de Angola e Moçambique com Naturais da Metrópole (1920-1974). Lisboa, Portugal: Edições Afrontamento, 2007.

- Cezne, Eric. “Forging Transnational Ties from Below: Challenging the Brazilian Mining Giant Vale S.A. Across the South Atlantic.” The Extractive Industries and Society 6, no. 4 (2019): 1174–1183.

- Cezne, Eric, and Jana Hönke. “The Multiple Meanings and Uses of South–South Relations in Extraction: The Brazilian Mining Company Vale in Mozambique.” World Development 151, no. March (2022): 105756.

- Chichava, Sérgio, Jimena Duran, Lídia Cabral, Alex Shankland, Lila Buckley, Lixia Tang, and Yue Zhang. “Brazil and China in Mozambican Agriculture: Emerging Insights from the Field.” IDS Bulletin 44, no. 4 (2013): 101–114.

- Chilingue, Evaristo. “Vem Aí O Novo ‘Eldorado’ de Moçambique Para Os Próximos Tempos,” Carta de Moçambique, 2021, 23 December. Available from: https://cartamz.com/index.php/politica/item/9589-vem-ai-o-novo-eldorado-de-mocambique-para-os-proximos-tempos.

- Clarence-Smith, William Gervase. The Third Portuguese Empire, 1825-1975: A Study in Economic Imperialism. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1985.

- Clements, Elizabeth A., and Bernardo M. Fernandes. “Land Grabbing, Agribusiness and the Peasantry in Brazil and Mozambique.” Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy: A Triannual Journal of Agrarian South Network and CARES 2, no. 1 (2013): 41–69.

- Collier, Paul, and Stefan Dercon. “African Agriculture in 50Years: Smallholders in a Rapidly Changing World?” World Development 63 (2014): 92–101.

- Coughlin, Peter E., Charles Esser, Peter Bechtel, Ruth Mkhwanazi Bechtel, and Dionísio Nombora. How USAID Can Assist Mozambique to Cope with the Impending Resource Boom. Maputo: Moçambique, 2013.

- Côté-Roy, Laurence, and Sarah Moser. “‘Does Africa Not Deserve Shiny New Cities?’ The Power of Seductive Rhetoric Around New Cities in Africa.” Urban Studies 56, no. 12 (2019): 2391–2407.

- Crow-Miller, Britt. “Discourses of Deflection: The Politics of Framing China’s South-North Water Transfer Project.” Water Alternatives 8, no. 2 (2015): 173–192.

- Dzumbira, Witness, Herman S. Geyer Jr., and Hermanus S. Geyer. “Measuring the Spatial Economic Impact of the Maputo Development Corridor.” Development Southern Africa 34, no. 5 (2017): 635–651.

- Easterling, Keller. Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space. London, UK: Verso, 2014.

- England, Andrew. “Mitsui Invests $1bn in Vale’s Mozambique Coal Projects.” Financial Times (2014.

- Enns, Charis. “Mobilizing Research on Africa’s Development Corridors.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 88 (2018): 105–108.

- Enns, Charis, and Brock Bersaglio. “On the Coloniality of “New” Mega-Infrastructure Projects in East Africa.” Antipode 52, no. 1 (2020): 101–123.

- Fair, Denis. “Mozambique: The Beira, Maputo and Nacala Corridors.” Africa Insight 19, no. 1 (1989): 21–27.

- Ferguson, James. Global Shadows: Africa in the Neoliberal World Order. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006.

- Friedmann, John. Regional Development Policy: A Case Study of Venezuela. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1966.

- Goldstein, Jenny, and Julian Yates. “Introduction: Rendering Land Investable.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 82 (2017): 209–211.

- Gonçalves, Euclides. “Agricultural Corridors as ‘Demonstration Fields’: Infrastructure, Fairs and Associations Along the Beira and Nacala Corridors of Mozambique.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 14, no. 2 (2020): 354–374.

- Grant, Andrew, and Fredrik Söderbaum. The New Regionalism in Africa. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2003.

- Hammond, Richard J. Portugal and Africa, 1815-1910: A Study in Uneconomical Imperialism. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1966.

- Hanlon, Joseph, and Marcelo Mosse. Mozambique’s Elite – Finding Its Way in a Globalized World and Returning to Old Development Models (Working Paper No. 2010/105). Washington, D.C.: UNU-WIDER, 2010.

- Hansen, Peo, and Stefan Jonsson. “Imperial Origins of European Integration and the Case of Eurafrica: A Reply to Gary Marks’‘Europe and Its Empires’.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 50, no. 6 (2012): 1028–1041.

- Headrick, Daniel R. The Tentacles of Progress: Technology Transfer in the Age of Imperialism, 1850-1940. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1988.

- Headrick, Daniel R. Power Over Peoples: Technology, Environments and Western Imperialism, 1400 to the Present. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010.

- Howarth, David. “Power, Discourse, and Policy: Articulating a Hegemony Approach to Critical Policy Studies.” Critical Policy Studies 3, no. 3-4 (2010): 309–335.

- Kaarhus, Randi. “Land, Investments and Public-Private Partnerships: What Happened to the Beira Agricultural Growth Corridor in Mozambique?.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 56, no. 1 (2018): 87–112.

- Laclau, Ernesto. On Populist Reason. London, UK: Verso, 2005.

- Laclau, Ernesto, and Chantal Mouffe. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy. London, UK: Verso, 1985.

- Lagerkvist, Johan. “As China Returns: Perceptions of Land Grabbing and Spatial Power Relations in Mozambique.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 49, no. 3 (2014): 251–266.

- Lesutis, Gediminas. “How to Understand a Development Corridor? The Case of Lamu Port–South Sudan–Ethiopia-Transport Corridor in Kenya.” Area 52, no. 3 (2020): 600–608.

- Mailafia, Obadiah. Europe and Economic Reform in Africa: Structural Adjustment and Economic Diplomacy. London, UK: Routledge, 2005.

- Mann, Michael. “The Autonomous Power of the State: Its Origins, Mechanisms and Results.” European Journal of Sociology 25, no. 2 (1984): 185–213.

- Martin, Guy. “Africa and the Ideology of Eurafrica: Neo-Colonialism or Pan-Africanism?.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 20, no. 2 (1982): 223–238.

- Meeuws, René. Mozambique — Trade and Transport Facilitation Audit. Rijswijk, The Netherlands: NEA Transport Research and Training, 2004.

- Mitchell, Jonathan. “The Maputo Development Corridor: A Case Study of the SDI Process in Mpumalanga.” Development Southern Africa 15, no. 5 (1998): 757–769.

- Mitchell, Timothy. Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil. London, UK: Verso, 2011.

- Mohan, Giles. “Beyond the Enclave: Towards a Critical Political Economy of China and Africa.” Development and Change 44, no. 6 (2013): 1255–1272.

- Morier-Genoud, Eric. “The Jihadi Insurgency in Mozambique: Origins, Nature and Beginning.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 14, no. 3 (2020): 396–412.

- Mosca, João, and Tomás Selemane. El Dorado Tete: Os Mega Projectos De Mineração. Maputo, Moçambique: Centro de Integridade Pública, 2011.

- Muchemwa, Cyprian, and Geoffrey T. Harris. “Mozambique’s Post-War Success Story: Is It Time to Revisit the Narrative?” Democracy and Security 15, no. 1 (2019): 25–48.

- Newitt, Malyn. A History of Mozambique. London, UK: Hurst & Company, 1995.

- Nuvunga, Milissão. “Region-Building in Central Mozambique: The Case of the Zambezi Valley Spatial Development Initiative.” Chap., In Afro-Regions: The Dynamics of Cross-Border Micro-Regionalism in Africa, edited by F. Söderbaum, and I. Taylor, 74–89. Uppsala, Sweden: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, 2008.

- Ong, Aihwa. Neoliberalism as Exception: Mutations in Citizenship and Sovereignty. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006.

- Peberdy, Sally. “Border Crossings: Small Enterpreneurs and Cross-Border Trade Between South Africa and Mozambique.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 91, no. 4 (2000): 361–378.

- Pereira, Victor. “A Economia Do Império E Os Planos De Fomento.” Chap., In O Império Colonial Em Questão (Sécs. Xix-Xx): Poderes, Saberes E Instituições, edited by M.B. Jerónimo, 251–285. Lisboa, Portugal: Edições 70, 2012.

- Perez-Niño, Helena. “The Road Ahead: The Development and Prospects of the Road Freight Sector in Mozambique – A Case Study of the Beira Corridor.” Chap., In Questions on Productive Development in Mozambique, edited by C.N. Castel-Branco, N. Massingue, and C. Muianga, 269–289. Maputo, Mozambique: Instituto de Estudos Sociais e Económicos, 2015.

- Pitcher, M. Anne. Politics in the Portuguese Empire: The State, Industry, and Cotton, 1926-1974. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Pitcher, M. Anne. Transforming Mozambique: The Politics of Privatization, 1975-2000. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Priemus, Hugo, and Wil Zonneveld. “What Are Corridors and What Are the Issues? Introduction to Special Issue: The Governance of Corridors.” Journal of Transport Geography 11, no. 3 (2003): 167–177.

- Rogerson, Christian M. “Spatial Development Initiatives in Southern Africa: The Maputo Development Corridor.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 92, no. 3 (2001): 324–346.

- Selemane, Thomas. A Economia Política Do Corredor Do Nacala: Consolidacão Do Padrão De Econonia Extrovertida Em Mocambique. Maputo, Moçambique: Observatório do Meio Rural, 2017.

- Shankland, Alex, and Euclides Gonçalves. “Imagining Agricultural Development in South–South Cooperation: The Contestation and Transformation of ProSAVANA.” World Development 81 (2016): 35–46.

- Smalley, Rebecca, and Euclides Gonçalves. “Cyclone Idai Hits Agriculture in Beira Corridor: Preparing for the Future.” Future Agricultures Blog (2019.

- Smith, José. “The Beira Corridor Project.” Geography: Journal of the Geographical Association 73, no. 3 (1988): 258–261.

- Soifer, Hillel. “State Infrastructural Power: Approaches to Conceptualization and Measurement.” Studies in Comparative International Development, no. 3-4 (2008): 231–251.

- Söderbaum, Fredrik, and Ian Taylor. “Transmission Belt for Transnational Capital or Facilitator for Development? Problematising the Role of the State in the Maputo Development Corridor.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 39, no. 4 (2001): 675–695.

- Söderbaum, Fredrik, and Ian Taylor. “Competing Region-Building in the Maputo Development Corridor.” Chap., In Afro-Regions: The Dynamics of Cross-Border Micro-Regionalism in Africa, edited by F. Söderbaum, and I. Taylor, 35–52. Stockholm, Sweden: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, 2008.

- Stein, Serena, and Marc Kalina. “Becoming an Agricultural Growth Corridor.” Environment and Society 10, no. 1 (2019): 83–100.

- Tafon, Ralph, David Howarth, and Steven Griggs. “The Politics of Estonia’s Offshore Wind Energy Programme: Discourse, Power and Marine Spatial Planning.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 37, no. 1 (2019): 157–176.

- Taylor, Ian. “Globalization and Regionalization in Africa: Reactions to Attempts at Neo-Liberal Regionalism.” Review of International Political Economy 10, no. 2 (2003): 310–330.

- Vines, Alex. Prospects for a Sustainable Elite Bargain in Mozambique: Third Time Lucky? London, UK: Chatham House, 2019.

- Wolford, Wendy, and Ryan Nehring. “Constructing Parallels: Brazilian Expertise and the Commodification of Land, Labour and Money in Mozambique.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies / Revue Canadienne D'études du Développement développement 36, no. 2 (2015): 208–223.

- Wullweber, Joscha. “Global Politics and Empty Signifiers: The Political Construction of High Technology.” Critical Policy Studies 9, no. 1 (2015): 78–96.

- Yapa, Lakshman. “What Causes Poverty?: A Postmodern View.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 86, no. 4 (1996): 707–728.