ABSTRACT

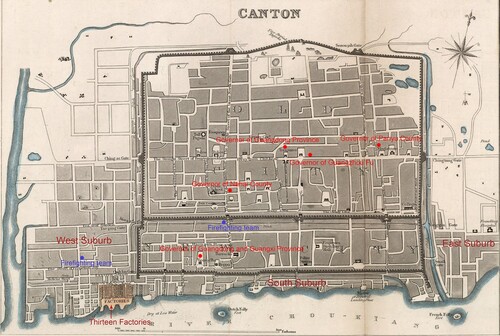

Canton (present-day Guangzhou) has long flourished as a port city. As the city expanded in the nineteenth century, the risks of conflagrations increased; streets became more crowded, buildings were more often made of wood, and there was more use of open fires. The reconstruction of Canton after conflagrations provides an excellent way to observe the resilience of urban space, understood here as the result of interactions among different stakeholders. This paper explores how authorities, local communities, foreigners, and Hong merchants addressed fires and rebuilt through laws, regulations, technologies and cooperation, and how responses to fire destruction shaped urban space. Divers stakeholders affected the reconstruction of buildings and streets. The government made laws to widen streets, communities built watchtowers, and foreigners made new plans for Thirteen Factories, a neigbhorhood along the Pearl River. At the same time, conflicts between communities and foreigners obstructed plans for urban transformation and maintained the stability of urban structures. The communities kept the traditional local community organizations the ‘Kaifong’ (local organization in street) who opposed the widening streets and fought against proposed fire zones around Thirteen Factories, thus pitching local interests against those of the foreigners in a complex social, political, and cultural context.

Introduction

Fires have long destroyed cities around the world; however, the ways in which different population groups have addressed rebuilding varies extensively. At times, rebuilding has led to minor adjustments in building materials or street width, on other occasions disasters have led to large-scale urban rebuilding. Bankoff, Luebken, and Sand brought together a number of essays to illustrate the diversity of post-fire rebuilding.Footnote1These decisions were often results of specific local conditions, stakeholder settings, technological conditions, or the political and economic context of the time. For example, plans for a large-scale rebuilding after the London fire of 1666 were discarded, and the capital of Britain saw rather limited changes. Lessons from the London fire were implemented in the conception of Philadelphia after 1862 instead. The fire of Hamburg in 1842, however, led to complete rebuilding of the inner city to respond to the needs of industrialization and the construction of new railways. The rebuilding of Tokyo after the Ginza fire of 1872 is yet another case, as it led to street readjustment that partially failed afterwards.Footnote2 The ways in which different population groups in Canton have responded to fires provides insights into yet another facet of the rebuilding after fire.

Large numbers of traders, shopkeepers, hawkers, craftsmen, workers, and beggars gathered in Canton (present-day Guangzhou), a prestigious port city for a long time. From 1757 AD to 1840 AD, Canton, located on the banks of the Pearl River and faces the South China Sea, was the only legal port city in China open to people from Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. Most of the trade taking place between China and the rest of the world was managed in this city, especially in the West Suburb where the neighbourhood of Thirteen Factories was located. Canton’s commerce attracted large numbers of people who sought success in businesses that reached around the nation and the world, as evidenced in a record from an officer of the British East India Company:

Though I had been in Paris, London, Amsterdam, &c. I never saw any thing like the crowds of people that attend the trading streets of Canton. I often thought that they were going to walk over one another. It is reckoned that there is in the city and suburbs 1,200,000 people.Footnote3

Scholars have studied nineteenth century Canton, after the arrival of foreigners, extensively, often focusing on modern (or western) architecture and planning, with much attention given to hospitals, churches, factories, accommodations, as well as the planning of Shameen (the British and French concession)Footnote5 and the Long Bund (长堤), the urban development on the bank of the Pearl River.Footnote6 This article adds to the existing scholarship by focusing on reconstruction after fires and the role played by various population groups – government, local communities and foreigners, and Hong merchants – whose responses varied in relation to their respective means and interests in the city.

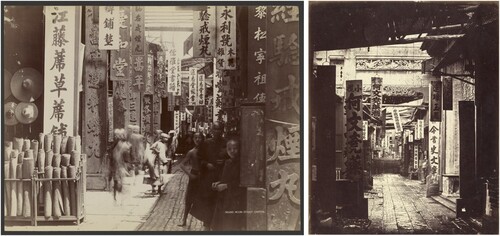

The urban history of Canton and the role of fires

In the traditional city of Canton, fires spread easily due to urban form, dense use, and flammable building materials. Most of the streets were narrow, with a width from three to fifteen feet, with the medium width in the city probably not exceeding eight feet.Footnote7 Courtyard buildings of two to three stories height lined both sides of the narrow streets. High land costs and population increase led to great demand for housing space. The streets were all flagged with large slabs of smooth stone on the ground, principally granite, which were not flammable. Yet, to protect pedestrians from sun and rain, they were covered by thin boards or matting or by canvas attached to the buildings alongside, allowing fire to be spread easily from one street to another. Similarly the walls were usually made of bricks with granite blocks at the bottom, supporting double-pitch roofs covered by tiles, but the buildings, the beams, floors, partitions, doors, windows and furnitures were made of wood, and the use of paper or gauze lanterns for lighting exposed the buildings constantly to the danger of fire ().

Figure 1. Left: Seung Moon Street, Canton, by A. Chan. About 1870; Right: Treasury Street, Canton, by Felice Beato. About 1860. Source: Digital images courtesy of Getty's Open Content Program.

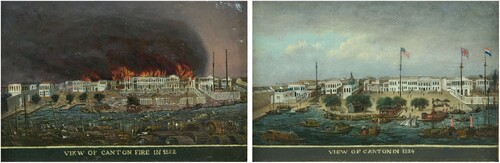

There are numerous fires recorded in the county annals, newspapers, and travel notes. One of the most famous and serious fires occurred in 1822. On the evening of November 1st, a bakery in West Suburb caught fire, which quickly spread to adjacent blocks. The governor, Ruan Yuan, climbed the city wall to alert officers to fight fire, but it could not be stopped. The citizens escaped with their belongings. The Hong merchants and foreigners hurried to transport commodities to boats on the Pearl River. The conflagration lasted for three days, destroying more than 70 streets, 700 lanes, and 15,000 houses. More than 100 people died in the disaster, including some foreigners.Footnote8 According to Dr. Morrison, who was an eyewitness:

The English warehouse was entirely consumed, but nine suits of apartments were preserved. The factories of the hong merchants, Fatqua, Chunqua, Punkhequa, and Mowqua, were completely destroyed. Thousands of houses and shops besides, were burnt to the ground. The Kwangchow hee said, that 50,000 persons were rendered houseless by the fire.Footnote9

Figure 2. Left: Thirteen Factories in fire, 1822. Source: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11840/71831 Right: Thirteen Factories after fire, 1824. Source: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11840/71827.

The response to the conflagration varied, with differences between population groups, the government, locals, and foreigners. The reconstruction after fires reflected the interests of various citizen groups and their control over space and their perceptions of the goal of rebuilding and planning. The next section explores their respective roles, power, and goals.

The role of the city government in fire control and rebuilding in Canton

Canton was an important city not only because it was a port city, but also because it was the capital of Guangdong Province. It was surrounded by double walls, with the inner encircling the area known as Old City and the outside wall encircling New City. Most of the government apparatus was inside city walls. Outside the city walls were several suburbs, which became the business centre ().

In the nineteenth century, Canton was a city with mature urban management policies. The New Regulations of Guangdong Province, a book on city management laws, details the new laws of firefighting that were established after the great fire of 1822.Footnote10 Here are two tenets of the firefighting laws:

First, the city government was expected to provide water and equipment for firefighting. The available water storage relied on wells, which could work as cisterns. In each principal street, a large well was dug; these were called ‘Great Peace Wells (太平井)’, and were most often used when fires broke out.Footnote11 The government was also responsible for the manufacture of firefighting equipment, such as fire engines, fire hoses, water guns, hooks, ladders, and buckets.

Second, firefighting teams needed to be established. There were two kinds of firefighting teams. One was a special team with 70 people (like a fire brigade), divided into two groups and taking turns going on patrol on ordinary days. The other team consisted of 80 soldiers chosen from armies. Half of the team were stationed respectively in areas called New City and West Suburb (), both of which were commercial centres where conflagrations broke out frequently. When team members discovered a fire, it was necessary to inform the rest of the team who were required to arrive at the scene of the fire as quickly as possible. They put out fires using fire engines and the water stored in the Great Peace Wells. If a fire was hard to put out, they climbed the roofs of buildings and disassembled them, removing flammable materials to keep the fire from spreading.

The authorities of Canton put a lot of effort into stopping fires. Their goal was to save the lives of citizens, preserve the economic power of the city and the tax revenue of government. The city government provided a system of fire prevention, including fire engine manufacture, firefighting, and fire use regulations. Their efforts to fight fire across the city included positioning firefighting teams in two commercial centres and requiring people to dig wells in every street. They occasionally issued regulations regarding reconstruction after fires. Some records show that the government tried to broaden streets after a conflagration in 1892. They ordered the reconstructed houses to be built two feet back from the street and required that all covers be cleared away from the tops of streets.Footnote12 The city authorities did not direct the street reconstruction, which was carried out by local street organizations, the Kaifong. In order to figure out why the local government seldom managed to massively transform urban space, we must take our concerns to the block scale, to explore how local communities dealt with fire and how their approach to reconstruction.

Approaches by Kaifong and individuals to fire prevention and rebuilding

The city was organized in small self-governing units called Kaifong, based in and around streets. A Kaifong functioned like an urban cell within the large city. The government could not interfere in Kaifong affairs, with some legal exceptions. A typical Kaifong had a main street and several small lanes intersecting it (). Buildings lined each side of the street or lanes, facing the street and stretching far behind it. Every building occupied a fixed site which was the legal property of the owner. Most of the buildings in a Kaifong were shops and residences with several apartments separated by one or two courtyards. The first apartment facing the street was usually set up as a shop or a gate, with a highly decorated appearance.

Figure 4. Sixteen Pu Kaifong,1907 Source: Illustrating the City’s Cultural Context-Past and Current Atlas of Guangzhou,edited by author.

These Kaifong had self-governing powers and independent finances; they established regulations of the community’s management, set up the residential blocks, maintained the public facilities, as well as managed reconstruction in the blocks. The Kaifong leadership collected funds in the name of rewarding gods, and gathered in the street temple to discuss community affairs.Footnote13 The communities were responsible for sacrifices, road construction, drain repairs, social relief, defence, and firefighting.Footnote14 After a fire, the Kaifong assigned people to clean the site, calculate loses, rebuild the public space with public finance, and supervised the residents in rebuilding their houses. Reconstruction in the Kaifong usually preserved the space and morphology that existed prior to the conflagration. The streets continued to be narrow and the buildings still featured wooden materials. After a fire, individual proprietors rebuilt their houses quickly to reduce business losses.

In general, local government did not have the power to rebuild community blocks and the Kaifong were unwilling to give up residential sites to increase the width of the street. As a result, the streets and buildings remained little changed after reconstruction. However, the community fought fires by taking measures to manage risks particularly in relation to buildings’ upper roofs.

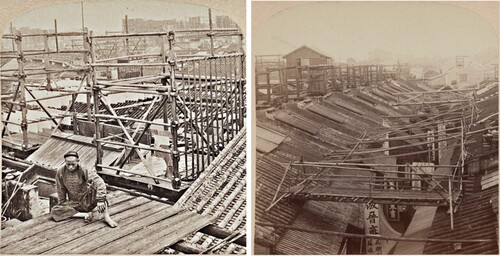

In a Kaifong, gates were erected at both ends of a main street; at night they were closed. Each gate was guarded by a watchman responsible for calling out the time, examining people crossing the street, as well as looking out for fires. In some principal streets, watchmen were stationed in watchtowers. Each of the watchmen was provided with a tom-tom and small gong. If a fire arose, by beating his small gong loudly and incessantly, he gave the alarm to the watchmen stationed in the adjacent watchtowers. The watchtowers in which these watchmen stationed at night consisted of small mat-covered shelters. They were erected on wooden platforms, or scaffolds raised far above the tops of adjacent houses, and were supported by long bamboo poles, which were tightly bound by strong cordsFootnote15 ( left). In addition, the watchtowers could be connected by wooden passageways that traversed the roofs, letting watchmen patrol from up high ( right). Watchtowers and passageways mostly appeared in prosperous commercial areas such as New City and West Suburb, where they formed a rooftop communication system. This system contributed to transforming the urban landscape.

Figure 5. Left: A watchman on a watchtower, by Underwood & Underwood, about 1900. Right: Watchtowers and passageways crossing streets, by Underwood & Underwood, about 1900. Source: Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Besides the watchtowers, communities also made efforts to set up firefighting regulations and facilities. In 1847 The Chinese Repository (a periodical published in Canton by Western missionaries) recorded a document translated from Chinese that reveals rare details of firefighting regulations in Kaifong.Footnote16 The text, roughly translated here explains that the shops should be each furnished with two large cisterns and twenty small jars, to hold a great quantity of water to be constantly ready for use. Every cistern should have a large bamboo trough to carry the water from place to place. As soon as a fire was discovered a connection was to be formed between the adjoining shops counting five in all from left to right, and three in all from front to rear. The whole number of cisterns was 30 and of the jars 300. As soon as flames broke out the water was to be freely distributed and poured in upon them. The watchmen were asked to ascend roofs and fill the cisterns and jars with water on the first and sixth of each month.

This document shows a complex firefighting system. These measures described were to be taken before the fire engines arrived. The document indicates that the measures were devised on the scale of an individual city block. When a fire broke out, the watchmen would warn the community and inform the city’s firefighting team. At the same time, the fire control system’s upper roof attendants worked immediately to stop fire spreading. It reveals the cooperation between Kaifong and the city in fighting fires.

The reconstructions and measures after fire conducted by communities related to the society and culture of local people. Their measures of fire prevention such as building watch towers, passageways, and cisterns reshaped the city scape. The water storage on roofs became a special scene in old Canton for a long time.Footnote17 It reveals the change of city reconstruction due to the technology and social organization at that time. In this progress, conflicts and cooperation between city government and communities contributed to the practice in Kaifong reconstruction. Communities had the power to rebuild their blocks and refused to change the dimensions of streets and buildings. On the other hand, the communities carried out fire prevention facilities above houses, cooperating with the city’s firefighting system to put out fires in the blocks. However, there was a special group who came from overseas and traded in Canton, trying to make some space transformation when rebuilt their blocks after fires.

Actions of foreigners and Hong merchants after conflagration

In the Canton System, Hong merchants monopolized external trade. They contacted foreigners directly, guaranteed for them, traded with them, and provided them with houses along the bank of the Pearl River, which contributed to the block known as Thirteen Factories.Footnote18.Foreigners were also constantly threatened by conflagrations, and they contributed technology and ideas to fire prevention. In 1743, the British Commodore Gorge Anson visited Canton, and helped use fire engines to put out a great fire. Footnote19 After that, people in Canton began to import fire engines from the British, making the engines an important component of Thirteen Factories and the city’s firefighting forces. After the great fire of 1822, foreigners came up with the idea of fire zones.

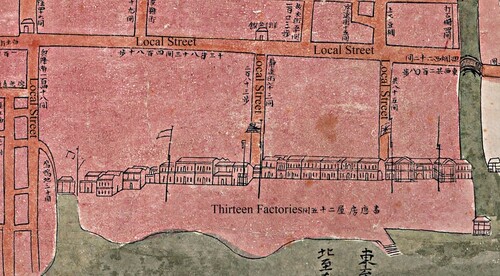

The Thirteen Factories can be regarded as a special Kaifong in which foreigners and Hong merchants resided and worked. In the reconstruction of Thirteen Factories after fires, Hong merchants and foreigners had common interests and acted as one stakeholder. After the fire of 1822, the foreigners petitioned the city government to create a fire zone between Thirteen Factories and adjacent commercial streets. They recognized the danger arising from local residents’ houses being built up against the walls of the factories and begged the government to make some sort of equitable arrangement with the owners of the ground so as to leave a space between the local people’s houses and the factories. Governor Li Hongbin approved the request and commanded Hong merchants to examine the place referred to and see if they could make a detailed report that would enable the government to act upon it.Footnote20 When local communities heard the news, they were angry about the idea of giving up land for fire zones which would harm their businesses. They were also insulted. They united against the plan, refused to sell burned land, and quickly rebuilt their shops. Hong merchants determined that it would be impossible to force the shop owners to sell their land. And the prices demanded were so exorbitant that but few of the shops could be acquiredFootnote21 ().

Figure 6. Map of Thirteen Factories and the adjacent streets, 1822. Source: The British Library. Edited by author.

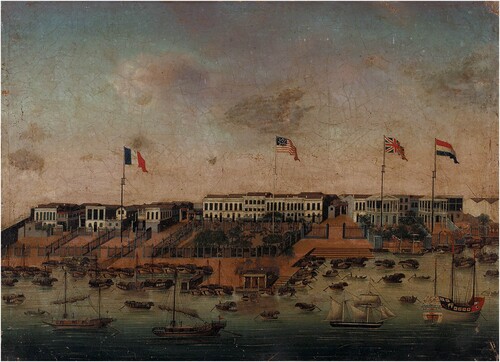

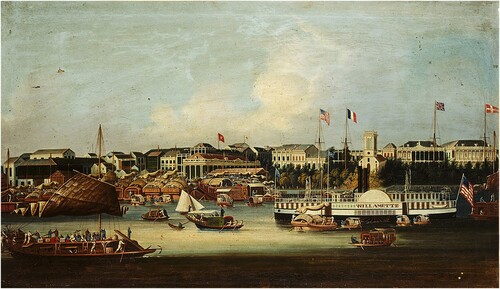

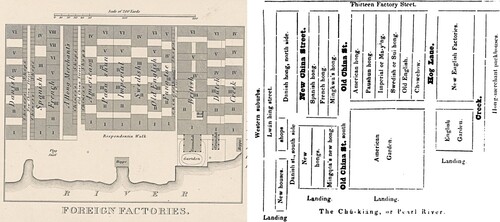

Although the idea of creating a fire zone failed because of the community opposition, the reconstruction of Thirteen Factories still contributed to a transformation of city space, and finally the fire zone idea was realized with Shameen Concession. However, the fires had already created opportunities for transforming Thirteen Factories, as can be seen in the export paintings. The landscape of Thirteen Factories was a popular subject of paintings which were painted by Chinese artists and bought by foreigners as souvenirs of visits to Canton. In paintings of Thirteen Factories from the 1770s to the 1850s, we can see the transformation of the landscape and buildings. In the early years of this period, the buildings were in Chinese style. One ‘factory’ was a long building that stretched from the river to the street behind and consisted of a number of courts, halls, and warehouses,Footnote22 with brick or wooden walls, tile roofs, and a simple façade with few decorations. After the 1770s, many export paintings showed that Western architectural decorations had been introduced to the factories. According to records, a conflagration destroyed 450 houses in 1773, affecting the factories.Footnote23 After the fire, the Hong merchants agreed that the foreigners could rebuild their facilities with western decorations, such as arches, pilasters, pediments, and colonnades (). Afterwards, Thirteen Factories became well known for its exotic appearance. The fires in 1822 and 1836 also brought changes to the factories. Although the fire zone proposal failed, Hong merchants tore down several buildings in the factories’ block and broadened Old China Street and Hog Lane. They also opened New China Street between the Spanish and Danish ‘factory’,Footnote24 creating gaps in the dense block (, left). To provide more space for entertainment and socializing, the square in front of the factories was expanded and a garden was erected on it ().

Figure 8. Plan of Thirteen Factories. Source: Left, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 1840. Right: Chinese Repository Vol16, No.7. July, 1846: 400.

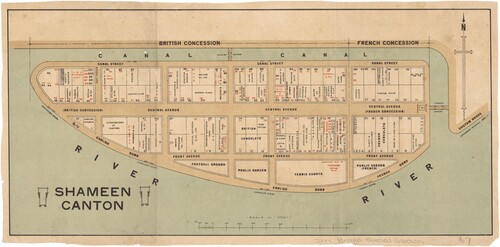

In 1840, The First Opium War broke out in Canton, and the British army attacked the city in 1841, ending in the Treaty of Nanking signed by the Chinese and British government. After the war, foreigners returned to Thirteen Factories and faced a tense relationship with local communities. Because of the conflicts between Chinese and Westerners, Thirteen Factories suffered arson, including the fires of 1842 and 1843, which resulted in major damage to the eastern and western factories. Because foreigners acquired more rights to rent land and rebuild houses after the treaty, after reconstruction Thirteen Factories was more splendid than ever. Three new factories were built on the square in front of the Spanish and French factories. The rest of the square became English Garden and American Garden (, right). A church was erected in the middle of the two gardens and a rectory behind it replaced Hog Lane. To the west of American Garden, a so-called Water Club was erected for entertainment. The Dutch and Creek Factories were disappeared and replaced by a New British Factory in the so-called Colonial Veranda Style (). With the new factories, gardens, church, and club, Thirteen Factories became more of a foreign community rather than a temporary commercial base. However, the new Thirteen Factories burnt again in the Second Opium War in 1856, when it was reduced into ashes. The site of Thirteen Factories was then abandoned by the foreigners, who proposed a plan for a concession in Shameen located to the west of Thirteen Factories. Shameen concession was divided into British and French concession by regular road grids (). A canal was dug between the island and West Suburb to separate the foreigners and Chinese. We argue that the planning of the Shameen concession reflected the 1822 proposal to create a fire zone around the foreigners’ block.

Thirteen Factories were destroyed in fire, rebuilt from fire, and finally disappeared in fire in 1856. Each reconstruction brought new transformations to the buildings and space, such as the Western-style decorations, new roads, new factories, gardens, church, and club. Thirteen Factories transformed for nearly a century, acting as an interaction centre of Westerners and Chinese ideas. The rebuilding of the Thirteen Factories by foreigners shows a different approach, with continuous changes compared with the ‘Kaifong’ block which was kept by local people. The foreigners introduced different technologies and ideas about firefighting and rebuilding to Canton, in a pattern of intercultural communication. Their behaviours also caused conflicts with local people, which acted as a political microcosm at that time. However, the reconstruction of Thirteen Factories helped to bring change to Canton. First, it brought an exotic landscape to the bank of the Pearl River. It also continued to change the city landscape along the river and triggered the construction of several commercial buildings along the bank of river.

Conclusion: the transformation and stability of urban space

In the nineteenth century, as people from different backgrounds gathered in Canton, they cooperated and conflicted with each other, developing two types of responses to reconstruction after fires. While the Kaifong communities rebuilt in line with traditional practices, the foreign communities saw fires as an opportunity to rebuild with new technologies and styles.

Different population groups in the city dealt with reconstruction after fires with different goals and tools, indicating the complex circumstances of city resilience. The management of fire prevention and firefighting by city government was one portion of city administration in the Qing Empire. The reconstruction and management of Kaifong by local communities reflected the culture of local society. The reconstruction and planning of Thirteen Factories and Shameen indicated the foreign factors. The urban form and function of Canton city in nineteenth century was linked to the national city administration, local culture and foreign factors, which was rare in the other cities. It provides a special perspective to study the transformation of a port city in the global context.

The conflicts among different groups and the wars between China and the West made the city to be a centre of cultural encounter. The case of Canton reveals how the people of Canton brought in their local culture and outside influence in the tumultuous nineteenth century, providing a deeper understanding of the early modern transformation of Chinese cities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Xueping Gu

Xueping Gu is PhD Student at School of Architecture, South China University of Technology and Visiting Student at Delft University of Technology with a grant from the China Scholarship Council. The article is related to her PhD research.

Carola Hein

Carola Hein is Professor History of Architecture and Urban Planning at Delft University of Technology, Professor at Leiden and Erasmus University and UNESCO Chair Water, Ports and Historic Cities. Her recent books include: Oil Spaces (2021), Urbanisation of the Sea (2020), Adaptive Strategies for Water Heritage (2020), The Routledge Planning History Handbook (2018).

Notes

1 Bankoff et al., Flammable Cities.

2 Hein, ‘Resilient Tokyo’; Hein, ‘Shaping Tokyo’.

3 Noble, A Voyage to the East Indies, 219.

4 Zhang and Liu, ‘The Exploration of the Late Qing Dynasty’s Fire Disaster,’ 30–35.

5 Peng, Modernity and Locality; Farris, Enclave to Urbanity.

6 Yang, ‘The Relationship of the Construction of Long Bund,’ 12–17.

7 Abeel, Journal of a Residence in China, 76.

8 Zhang, ‘The Several Conflagrations,’ 193.

9 Bridgman, ‘Fire Insurance in Canton,’ 30–37.

10 Huang, The New Regulations of Guangdong Province.

11 Gray, Walks in the City of Canton, 16.

12 Zhang and Liu, ‘The Exploration of the Late Qing Dynasty’s Fire Disaster,’ 30–35.

13 Qiu, ‘The Negotiation in Temples,’ 187–203.

14 He, ‘The Development of Kaifong Organization,’ 37–46.

15 Gray, Walks in the City of Canton, 31–32.

16 Bridgman ‘Regulations to Prevent Fires and Promote the Public Security,’ 332–333. This article was translated from Chinese. The original one was missed. It is said by the translator that the document appeared as early as 1817, recorded by Li Changjin of the District of Nanhai. Printed and published by Kung, at the Kingshu Office.

17 General Affairs Section of Guangzhou Municipal Council, The Abstract of Municipal Affairs of Canton, 2.

18 Liang, Study of Thirteen Hongs of Guangdong, 307–303.

19 Morse, The Chronicles of the East India Company Trading to China, 327.

20 Bridgman. ‘Fire Insurance in Canton,’ 30–37.

21 Morse, The Chronicles of the East India Company Trading to China, 66.

22 Becket and Dehondt, A Voyage to the East Indies, 223.

23 Conner, The Hongs of Canton, 39.

24 Dyke, Images of the Canton Factories, 83.

Bibliography

- Abeel, David. Journal of A Residence in China and The Neighboring Countries from 1823-1833. New York: J. Abeel Williamson, corner of Vesey and Washington Streets, 1836: 76.

- Bankoff, Greg, Uwe Luebken, and Jordan Sand. Flammable Cities: Urban Fire and the Making of the Modern World. Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2012.

- Bridgman, Elijah C. “Regulations to Prevent Fires and Promote the Public Security.” Chinese Repository 16, no. 7 (1847): 332–333.

- Bridgman, Elijah C. “Fire Insurance in Canton.” Chinese Repository 4, no. 1 (1835–1836): 30–36.

- Conner, Patrick. The Hongs of Canton: Western Merchants in South China 1700-1900, as Seen in Chinese Export Paintings. Beijing: The Commercial Press, 2014.

- Dyke, Paul A. V. Images of the Canton Factories 1760∼1822, Reading History in Art. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2015.

- Farris, Johnathan A. Enclave to Urbanity: Canton, Foreigners, and Architecture from the Late Eighteenth to the Early Twentieth Centuries. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2016.

- General Affairs Section of Guangzhou Municipal Council. The Abstract of Municipal Affairs of Canton in the Tenth Year in Republic of China, Canton: 1922.

- Gray, John H. Walks in the City of Canton. Hongkong: DE SOUZA & CO, 1875.

- Guangzhou Municipal Planning Bureau, and Guangzhou Urban Development Archives. Illustrating the City’s Cultural Context-Past and Current Atlas of Guangzhou. Guangzhou: Guangdong Map Publishing House, 2010.

- He, Yuefu. “The Development of Kaifong Organization in Canton in The Modern Time.” Twenty-first Century 3 (1996): 37–46.

- Hein, Carola. “Resilient Tokyo: Disaster and Transformation in the Japanese City.” In The Resilient City, edited by Lawrence Vale and Thomas Campanella, 213–234. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Hein, Carola. “Shaping Tokyo: Land Development and Planning Practice in the Early Modern Japanese Metropolis.” Journal of Urban History 36, no. 4 (2010): 447–484.

- Huang, Entong. New Regulations of Guangdong Province (粤东省例新纂), published in 1846, Canton.

- Liang, Jiabin. Study of the Thirteen Hongs of Guangdong. Guangzhou: Guangdong’s People Publishing House, 2009.

- Morse, Hosea B. The Chronicles of the East India Company Trading to China 1635-1834. vol 4. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1926.

- Morse, Hosea B. The Chronicles of the East India Company Trading to China 1635-1834, vol 1. Guangzhou: Guangdong’s People Publishing House, 2016.

- Noble, Charles F. A Voyage to the East Indies in 1747 and 1748. London: Tully’s Head; and T. DURHAM, at the Golden Ball, near Norfolk-Street, in the Strand, MDCCLXII, 1762: 219.

- Peng, Changxin. Modernity and Locality: The Modern Transformation of City and Architecture in Lingnan. Shanghai: Tongji University Press, 2012.

- Qiu, Jie. “The Negotiation in Temples by Residents of Canton in The Late Qing Dynasty.” Modern Chinese History Studies 2 (2003): 187–203.

- Yang, Yingyu. “The Relationship of the Construction of Long Bund and the Urban Development of Canton in the Morden Time.” Guangdong History 4 (2002): 12–17.

- Zhang, Jiayu, and Liu Zhenggang. “The Exploration of the Late Qing Dynasty’s Fire Disaster and Defense Mechanism: Taking Guangzhou for Instance.” Historical Research in Anhui 4 (2005): 30–35.

- Zhang, Wenqin. “The Several Conflagration Accrued in Thirteen Factories, West Suburb of Canton in Qing Dynasty.” In Thirteen Factories in Canton and the Early Relationship Between China and the West, edited by Zhang Wenqin, 193–200. Guangzhou: Guangdong Economy Publishing House, 2009.