ABSTRACT

This paper presents a periodized overview of informal urbanization in Vienna in the twentieth century. It offers a new perspective on the evolution of planning discourse and the phenomenon’s handling by planning authorities. The variegated manifestations of ‘Informal Vienna’ triggered an ongoing dispute on how orderly city development could be re-established after 1945. Our approach combines quantitative and qualitative aspects and illuminates not only the shifting significance of informal urbanization over several decades – especially in their lengthy formalization process – but also highlights the co-evolution of formal planning and the Viennese informal ‘grand project’.

In a comparative historical analysis based on the evaluation of the balances of formal and informal production of space, previous narratives of Red Vienna’s dominant role in answering the ‘housing question’ in the interwar period (and beyond) are challenged. The frictions it created with the instruments and categories of formal planning, we argue, are crucial to understanding the consequences of informal development in Vienna.

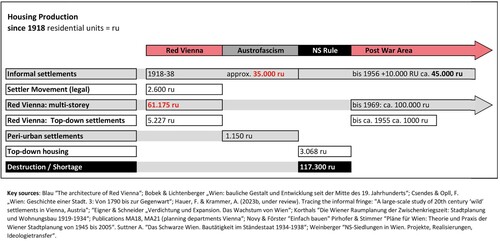

Furthermore, we present a typological approach on the grades of informality which allows for a reconstruction of the formalization processes in time. This ‘graduation of informality’ contributes to the ongoing attempts to classify various manifestations of informal urban development in the global South and North.

Introduction: the perception of the informal city in the field of urban research

In recent decades the informal city was primarily considered a phenomenon of the Global South.Footnote1 The UN report ‘The Challenge of Slums. Global Report on Human Settlements’ of 2003 impressively described the spread of the Informal City: In 2003 almost 1 billion people – then 32 percent of the world’s urban population – lived in slums, the majority of them in the developing world.Footnote2 Today – despite efforts at improving slums and preventing the emergence of new ones, which has led to a reduction of people living in slums in the developing countries to 30 per cent – absolute numbers are still rising. Divergent perceptions of the phenomenon evolved and interpretations were formulated. In his 2005 book The Planet of Slums (2005)Footnote3 the urban theorist Mike Davis described the fast-growing shantytowns in the global south as a symptom of maldevelopment that derived from the downside of (capitalist) globalization. Others, like the economist Hernando de SotoFootnote4, considered informal development a supplement to the formal sector that could make an important contribution to the overall economic system. Recent contributions to the debate on the implications of global informal urbanization like those of journalist Doug SaundersFootnote5 stand in the tradition of an affirmative approach. Saunders, unlike Davis, describes the global slum as vibrant place, where new forms of social and spatial organization and entrepreneurship can emerge – the productive slum as an engine of economic globalization.Footnote6

Informal production of space in Europe

To this day, comprehensive and comparative research on the history and presence of informal city development in Europe is still missing. An exception is the work of Spanish urbanist Noel ManzanoFootnote7, who attempts to open up a perspective on European Informality as a diverse phenomenon with partially shared characteristics. Otherwise, scholarly work is restricted to specific territories – states, regions and cities.Footnote8

There is relevant research on the history of informal development in France. The studies of the French bidonvilles by Marie-Claude Blanc-Chaleard are particularly noteworthy.Footnote9 Additionally, there are substantial studies on informal production of space in south-eastern Europe. Dubravka SekulićFootnote10, Bizerka MitrovićFootnote11 and others are researching informal development in past and recent times in Belgrade. During the transition from a socialist to a capitalist system, informal settlements continued to grow in the Western Balkans. A wide variety of social groups were involved in the illegal building activity, which is still an important element of general building culture today.Footnote12 It is not a mere crisis phenomenon, but a form of informality that has a certain legitimacy.Footnote13 This form of consolidation of informal practices demonstrates that informality continues to be a relevant factor for spatial development in present-day Europe.

This concentration in scholarly works on singular contexts may be related to the complex variations and nuances of informality that are tied to particular geographical and historical contexts as well as the cumbersome scientific groundwork in tracing the spatial and social development of these urban entities. Thus, systematic comparison and generalization are challenging tasks. It speaks volumes that in a recently published handbook on informal urbanizationFootnote14 only one article out of twenty-six is dealing with European informality, while all the others are devoted to case studies located in the Global South.

The crises that shook Europe in the twentieth century – above all two World Wars as well as the global financial crisis of 1929 – were already global phenomena that demonstrated an increasing geopolitical and financial interconnectedness. The social dislocations of European colonialism – which continued during its eventual erosion – and those that followed the implosion of the European order are closely linked. The result was devastating social hardship in the Global South as well as in the Global North, which led to the self-help project ‘Informal Settlement’. Although informality arose in specific regional circumstances, it is rooted in the same global context.

In Europe, spurts of informal urban development occurred in states of exception, in the shadow of rigorous martial law, in the political vacuum of the post-war period or in phases of economic and social hardship. In a state of exception, there was not only emergency law and measures executed top-down – as described by Giorgio AgambenFootnote15 – but also a partial powerlessness of the legislative and executive state organs which ultimately laid the ground for informal development. Later, the fall of the iron curtain and more current crises such as the Balkan Wars also resulted in social distress and widespread states of emergency. This has triggered various forms of self-help in the form of illegal land appropriation and settlement activity as well as practices of home-grown food and subsistence farming, all in an effort to reduce housing shortages and acute famine. The Parisian bidonvilles (canister villages), the Fischkistendörfer (fish box villages) of Hamburg and the Viennese Bretteldörfer (board villages) share their origin in the social and often political state of emergency but differ largely in their ‘careers’ in subsequent phases of normalization. A closer look at the history of many European and North American and even Australian cities reveals an often hidden history of informal development that has been described in a growing number of studies in recent decades.Footnote16 Recent forms of informality in the context of European city development present a heterogenous picture. For instance, the ‘informal building culture’ of Italy that is an often-tolerated part of the real estate industryFootnote17, must be distinguished from current forms of ‘European slums’ as they manifest themselves on the outskirts of the Spanish capital Madrid. In Southern Europe, a tendency to disregard building and zoning regulations can be observed to varying extents in several countries. Overall, informal development is neither a marginal nor a predominant practice in this region.Footnote18

Vienna’s ‘wild’ settlements – state of research

The largely illegal ‘wild’ settlements have left their mark in the collective memory of generations: The ‘wild settlement’ (vernacular) was a common expression in Vienna also used in Germany and in former Yugoslavia (‘wild building’). It is a multifaceted term that seems to ambiguously refer to a disorderly character of both the dwelling structure and its inhabitants.

Scientific literature on the topic of Vienna’s informal settlements is scarce and all but comprehensive. The historiography of twentieth century urban development and planning in Vienna typically discusses the surge of spontaneous settlements after the collapse of Austria-Hungary as a prelude to the study of the imposing architectural schemes of ‘Red Vienna’ executed between 1924 and 1934.Footnote19 According to most publications, the squats evolved into a highly organized cooperative settlement movement that, by 1921, was no longer ‘wild’ but largely co-opted by the city government and the social democratic party. In 1923, it was replaced by a programme of large-scale public housing and municipal settlements.Footnote20

The cooperative grassroots movement, with its innovative organizational and architectural forms, has attracted wide scholarly attention since the 1980s.Footnote21 As Peter MarcuseFootnote22 noted, Vienna’s post WWI settlers and gardeners are ‘probably the most widespread example of physical self-help in housing in the twentieth century in an industrialized nation’. However, as numerous examples showFootnote23, informal settlements and practices did not disappear after the advent of the cooperative settlement movement, nor was the surge from 1918 to 1921 the only one. Bottom-up urbanism was a continuous practice for almost half a century, albeit in an individualistic fashion rather than as cooperative socialism.

Accounts of Vienna’s urban development during Austrofascist (1934–1938) and Nazi rule (1938–1945) tend to neglect the topic of bottom-up urbanism outside the given legal framework.Footnote24

After 1945, Vienna’s informal urban heritage and the ongoing illegal occupations of land prompted a lively debate among urban planners and in the wider public.Footnote25 Yet the topic is all but absent from studies on Vienna’s post-war development and planning.Footnote26 Evidently, it is eclipsed by the powerful narrative of urban ‘rebirth’Footnote27 and Fordist modernization of the city that was widely fostered after major reconstruction works were completed and the country had regained independence in 1955. The surveys and studies conducted by urban geographers Hans Bobek and Elizabeth LichtenbergerFootnote28 in the 1950s and 1960s are the only exceptions to this trend.

Only recently have the Viennese allotments, their multi-layered organizational background and their importance for urban food production in times of crisis received some academic attention.Footnote29 Friedrich Hauer and Andre KrammerFootnote30 have highlighted the overall importance of informal urban development since WW1.

Methods: reconstruction and mapping, timelines, quantitative comparative analysis, typological differentiation, discourse analysis

The research presented in this article, which was produced within the framework of the project ‘Wien Informell – Informelle Stadtproduktion 1945–1992’ and is based on cartographic, quantitative as well as qualitative research and methods.Footnote31

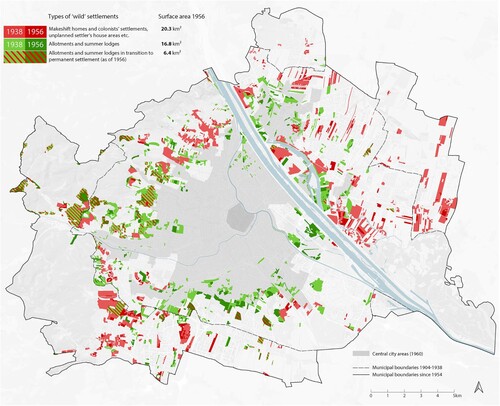

Cartography ()

A spatial reconstruction of Vienna’s Informal Settlements 1938–(1928)–1956–2020 was accomplished with the aid of GIS-based mapping.Footnote32 The cartographic reconstructions () show the expansion of informal settlements between Vienna’s inner and outer periphery, as well as the results of a decades-long process and the transfer of formerly informal structures into various zoning categories.

Typology

A typological system was developed in order to distinguish basic types and development phases of Vienna's informal settlements. It differentiates between gradations of informality by considering various sub-aspects of informality in relation to legal frameworks and infrastructural equipment (see below).

Contextualization

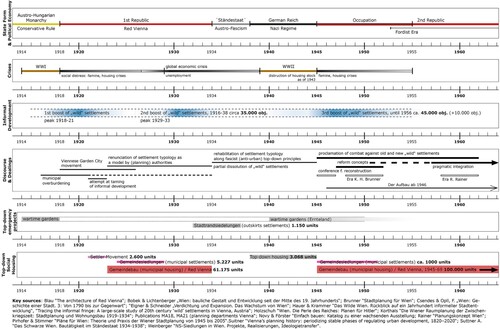

The spatial reconstruction was supplemented by timelines that trace phases and peaks of the ‘wild’ (informal) settlement activity and relate them to relevant parallel historical developments. The contextualization also includes quantitative comparisons with contemporary forms of housing production in order to derive conclusions about the significance of informal urbanization for the development of the city as a whole.

Discourse analysis

A reconstruction of the planning debates on the ‘problem of the “wild” settlement’ was undertaken within the framework of a discourse analysis.Footnote33 The professional discourse was investigated in publications on provincial and spatial planning, as well as in professional publications of the city planning departments such as the periodical Der AufbauFootnote34 (The Construction) – and other periodicals of the administration such as the Amtsblatt der Stadt Wien (Official Journal of the City of Vienna) or the Rathaus-Korrespondenz (Town Hall Correspondence) 1945–1985. In addition to the Wiener Stadt-und Landesarchiv – WStLA (City and Provincial Archives of the City of Vienna) and the archives of the city planning departments, the holdings of various specialized libraries were consulted. Relevant monographs such as Karl Heinrich Brunner's Stadtplanung für Wien (Urban Planning for Vienna) 1952 or Roland Rainer's Planungskonzept Wien (Vienna Planning Concept) 1962 supplemented the evaluation.

CartographyFootnote35

The identification and categorization of informal settlements was based on the research carried out by Hans Bobek and Elizabeth Lichtenberger at the Institute of Geography of the University of Vienna in the 1950s and 1960s. Under their tutelage, comprehensive urban structure maps (scales 1:25,000–1:3500) were produced. Phases of urban development, situational factors as well as building typologies were investigated. These surveys were summarized and published in several series of maps, corresponding articles and books: Besides Bobek and Lichtenberger, Trimmel was of particular importance for our study. During digitization, punctual additions and corrections were made based on local survey maps and photographs.

Geo-referencing and rectifications relied on historical and present-day geodata provided by the City of Vienna (MA 41, open government data). Ortho imagery of the urban area from 1938, 1956, 1976, 1992, 2014 and 2021–2023 enabled the tracing of the emergence and transformation of settlements, using regressive-iterative map sequencing. GIS-data on present-day zoning was provided by the city’s department of area planning and zoning (MA21).Footnote36

Contextualization 1: informal settlement in three main spurts

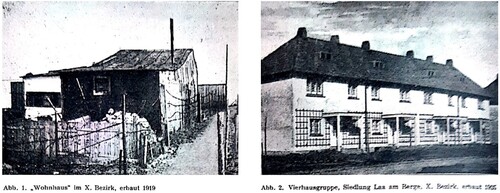

The triggers for the emergence of ‘wild’ informal settlements in Vienna were various political and social crises in the twentieth century – especially the devastations resulting from two world wars and the world economic crisis of the late 1920s (). The origin of the ‘wild’ settlements as a mass phenomenon is likely to be found in the food shortage that occurred in Vienna as the First World War dragged on. From 1914 onwards, there was a widespread garden land campaign, in the course of which so-called Kriegsgemüsegärten (wartime gardens) were made available to the Viennese for partial self-sufficiency. Contemporary sourcesFootnote37 already indicate that during the war, simple dwellings were erected on wartime garden areas during the war, which served the purpose of habitation. By the mid-1900s, the self-made ‘city of settlers and gardeners’ had transformed more than 43 km² of peri-urban terrain.Footnote38 In 1918, after the end of the First World War and the collapse of the Habsburg Monarchy, the Viennese suffered from persistent food and housing shortages. Private housing construction had come to a halt by this time, and although the population as a whole was declining, more households were developing due to a tendency to avoid living in overcrowded tenements. In spontaneous self-help, tens of thousands of Viennese acquired plots of land on the outskirts of the city or used existing plots of former wartime gardens and allotments to keep their heads above water by growing their own food. They often erected simple huts from readily available material, popularly known as Brettelhütten (board huts), forming so called Bretteldörfer (board villages) which served as informal living compounds. The ‘wild’ settlements in Vienna were clusters of simple self-built shacks and later consolidated single-family houses on plots of often very different sizes. In some cases, rooms seem to have been sublet, as records from the 1930s show.Footnote39 In winter, heating was provided by firewood taken from the floodplain forests or the Vienna Woods, or by coal and coke, which could also be found in waste dumps.

Figure 2 . Contextualization of Vienna’s ‘wild’ urbanization 1918 onwards. Source: Andre Krammer (research project ‘Wien Informell – Informelle Stadtproduktion 1945–1992’ funded by Jubiläumsfonds der Oesterreichischen Nationalbank (OeNB) under grant number 8584).

In the first years of the interwar period there was a rapid expansion of ‘wild’ settlements in Vienna’s fringe zones. Inflation and rising unemployment in the years leading up to the world economic crisis of 1929 – which also affected Vienna – led to another boom in ‘wild’ settlements that lasted well into the 1930s.Footnote40

A third significant surge in ‘wild’ settlements occurred towards the end of the Second World War, when food shortages and the destruction of buildings drastically increased the number of ‘bombed out’ people. Social hardship continued in the state of exception of the post-war years. Informal settlement activity then gradually declined due to the slow onset of economic recovery – but probably only came to a standstill in the course of the 1960s.

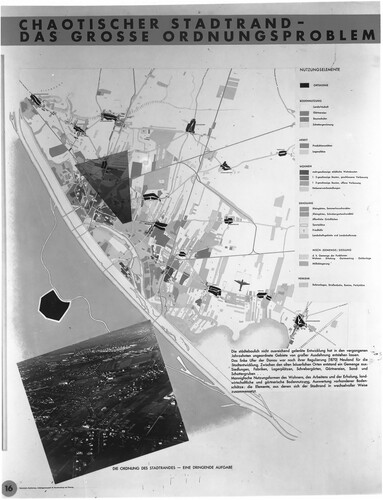

Contextualization 2: comparative analysis and conclusions

Informal housing development was an essential factor in the overall balance of urbanization and housing production in Vienna during the First Republic (1918–1934) and in a weakened form in the phase of reconstruction after 1945 (). Cautious estimates assume that approximately 35,000 informal housing units were created between 1918 and 1938 as part of informal developments.Footnote41 This assessment is based on area calculations (see cartography) and derived estimates of an average plot size and percentage of residential use sourced from case studies. After the Second World War, an estimated 10,000 additional housing units were added according to the increase in area.Footnote42 The total of 45,000 units considered with an average family size in this period in a range of 2.3–2.5 persons, leads to an estimated 100,000–110,000 Viennese who met their housing needs in ‘wild’ settlements.Footnote43 This figure coincides with contemporary estimates.Footnote44 In order to assess the importance of this phenomenon, the number of units created in ‘informal housing production’ must be compared with those created in the framework of Red Vienna between 1918 and 1934. The latter amounts to a total of 62,000 units.Footnote45 It can be concluded that the social housing construction of the interwar period, which was realised top-down, and the housing supply through the informal self-help project ‘from below’ functioned like communicating vessels, both of which contributed simultaneously to the ‘resolution of the housing question’: Informal Vienna relieved the pressure on Red Vienna.

Figure 3. Comparative analysis of housing production since 1918. Source: Andre Krammer (research project ‘Wien Informell’ (OeNB) grant number 18584.).

Private housing construction had more or less come to a standstill at the latest after the implementation of the ‘Tenant Protection Ordinance’ (1917), the ‘Housing Requirement Act’ (1919) and further tenant protection laws that made private housing construction largely unprofitable. The linear model developed by the urban und housing construction researchers Klaus Novy and Wolfgang FörsterFootnote46 distinguished four phases:

Phase I: Emergency project from below – the wild settlements 1919–1921

Phase II: Cooperative settlements – new foundation, concentration, formation of associations (1921–1923)

Phase III: The Communalization of the Settler Movement – The Community Settlement 1923–1930

Phase IV: Emergency project from above – suburban settlements as a job creation programme 1930–1934

With today's knowledge, which traces the persistence of informal settlement activity in several spurts, the long-lasting co-existence of informal and formal settlement structures must be emphasised. In addition, the balance of the cooperatively organized and municipally supported settler movement between 1921 and 1923 with about 2,600 dwelling units compared to that of the informal settlement activity – about 35,000 dwelling units until 1938 (see above) – challenges previous weightings. The hypothesis of a more or less ‘tamed’ wild movement cannot be upheld, since only a fraction of the settlement movement could be steered into formal channels.

In the post-war period after 1945, the municipality's social housing programme was resumed and by 1969, around 100,000 dwelling units had been realized.Footnote47 But these first and foremost compensated the loss of housing stock due to wartime destruction. The extent of the destroyed substance and the sluggishness of the reconstruction measures also explain why there was a further push for self-help and a renewed growth of ‘wild’ settlements in the post-war period.

Definitions and graduation of informality

Any definition of informality has to be relatively complex since it needs to integrate various levels of observations simultaneously. The UN Report ‘The Challenge of slums’ proposed an ‘operational definition of slums’Footnote48 that was developed in the context of the ‘United Nations Expert Group Meeting’. Physical as well as legal aspects were combined while social factors that are more difficult to grasp were excluded. The central parameters were ‘inadequate supply with safe water, inadequate access to sanitation and other infrastructure, poor structural quality of housing, overcrowding and ‘insecure residential status’.Footnote49

Other perspectives display different priorities: Urbanistic perceptions focus more on the informality of housing and settlements, while economic approaches concentrate on informal underground economies. The economic perspective is split into a structuralistic and legalistic tradition.Footnote50 While the former attributes an important role to the shadow economy, that refers to the inner contradiction of the capitalist system as a wholeFootnote51 and is interrelated with it on numerous levels, the latter stresses the potentials of a small-scale structure of microenterprises.Footnote52 The legalistic or bureaucratic perspective is largely compatible with neoliberal concepts that differentiate between a state-driven formal economy and one that is primarily driven by individual stakeholders and entrepreneurs.Footnote53 In this tradition of thought Hernando de Soto saw the informal city as a survival strategy and a safety net for social tensions and stressed the entrepreneurship of the poor and the destitute.Footnote54 The legalists considered this a reaction to overly state-driven regulations.Footnote55 Another aspect concentrates on landownership and property issues in general.Footnote56 Informal land appropriations in this view include regulated as well as unregulated occupations, unauthorized subdivision of legal properties and distinct forms of unofficial tenancy systems.Footnote57 Recently, a number of authors point out that a clear distinction between the formal and the informal system (city) is hardly possible.Footnote58 Often the informal sector of the economy and the informal city (production of space) is considered an integral part of the capitalist system.

A graduation of informality of ‘wild’ settlements of Vienna ()

Due to the long and turbulent history, the diverse groups of people involved and the city’s variegated geographyFootnote59, Vienna’s informal settlements were clearly a colourful phenomenon. While urban informality is treated in terms of illegality, insecurity, self-organization and incrementalityFootnote60, the focus of this research lies on settlements rather than informal construction practices. We deliberately use the umbrella term ‘wild’ settlement, which has become entrenched both in everyday language and in planning circles.Footnote61 We subsume the following under it: Settlement structures that, either as a whole or in partial aspects, did not comply with zoning and building regulations.Footnote62

Figure 4. Typology and Graduation of Informal Settlements (in Vienna). Source: Andre Krammer (research project ‘Wien Informell’ (OeNB) grant number 18584.).

The various causes of informal settlement activity – the desire for partial self-sufficiency, the housing shortage and later also real estate speculationFootnote63, often created a situation of mixed land use and buildings.Footnote64Settlement houses cobbled together with basic materials, recreational gardens and wastelands coexisted for decades in the same settlement. The ‘wild’ compounds underwent a complex process of transformation and formalization, which was often marked by different speeds of change for the city as a whole and for the individual settlements..Footnote65 After 1945, it took several decades to integrate ‘wild’ settlements into the formal city. The confusion of legal status, as well as of the urban fabric as a whole, continued during this time. In order to clarify this complex situation and to be able to distinguish basic types of informal settlements in Vienna, a systematic classification was developed ().

The emanating shades of informality allow a differentiated discussion in relation to tenure, zoning law, building code and public utilities. It combines a legalistic perspective with an urbanistic one. A graduation of informality () – grade 3 (squatter settlement) to grade 0 (formalized settlement) simultaneously enables the differentiation of types of informal settlements as well as the reconstruction of the trajectory of a specific settlement in the context of its formalization. The wide-spread integration of previously informal settlements into the formal city suggest the importance of a dialectic of general categorization AND the reconstruction of distinct careers of individual settlements. Singular characteristics and ‘biographical’ particularities evade a strict categorial and typological classification and can only be reconstructed in the framework of case studies that cannot be considered here and will be discussed in detail in subsequent publications.

The legal perspective and its relation to infrastructural aspects

The legal perspective emphasizes the state of contradiction of ‘wild’ settlements to the formal instruments and legal regulations used by planning authorities. The infrastructural equipment of the settlement (or plot) – regarding paved roads, canalization, water supply and electricity – is included in the categorization since a complete infrastructural embedding has been a precondition for legalization. The proposed graduation of informal settlements in Vienna will serve as a basis for further categorial differentiation that needs to include territorial, geographical and morphological considerations.Footnote66

Breakdown of the proposed gradation system

Grade 03 – Squatter Settlement: It is marked by an informality (or rather illegality) – on all levels. The typical geographical setting is a cleared area in the floodplain forest of the Danube river or in the Viennese woods. Especially after 1918, in the immediate post-war period, countless Viennese undertook forest clearings in order to obtain firewood. The cleared terrain was subsequently often used for dwelling in simple habitations due to the prevailing housing shortage and often also for self-supply and sometimes even small animal breeding. These settlements were often developed on precarious sites – like steep terrains threatened by landslides or in floodplains haunted by recurring floods and subsequently threatened by epidemics. These endangerments were later often used by the authorities to argue for resettlement. Examples for this category are the Bretteldorf, the Bruckhaufen and the Biberhaufen settlements, all located in the floodplains of the Danube, or the settlements at the foot of the Wolfersberg, a distinctive elevation in the Viennese woods. Today most of these former squatter settlements are formalized suburban housing quarters – residential areas (Wohngebiete WI), garden settlement areas (Gartensiedlungsgebiet GS) and today constitute fully reformed building areas of the city.

Grade 02 – Type A – Informal Plot Settlement: It is marked by the simultaneity of formal land use (often lease contracts of some sort) and an informal (illegal) utilization for dwelling purposes. The typical geographical setting is a farmland area in the north-eastern part or in the southern fringe areas of the city. Often farmers subdivided some of their arable fields and leased them to those who were obviously willing to settle. These plots were situated in designated farmland, outside official building land zones. For the most part these ‘wild’ arable settlements – so called Ackersiedlungen – had no connection to the infrastructural networks of the city, like paved roads, sewerage, water supply and electricity.

Typical examples for this category are the wide-spread Ackersiedlungen around the core of Essling, an established village structure in the north-eastern part of Vienna. Today, most of these erstwhile ‘informal plot settlements’ have been transformed into suburban housing quarters (residential areas or garden settlement areas) dominated by single-family houses or allotments with now legal all-year residences.

Grade 02 – Type B – Informal Allotment Settlement: It is characterized by an overlap of an initial allotment use and an additional utilization for (illegal) dwelling purposes. The typical geographical setting is the fringe area of the consolidated city. Often these were mixed settlements – so called Gemengesiedlungen – that were characterized by a coexistence of plots of solely horticultural utilization nearby others with all-year residences. The condition of these buildingswas often very heterogeneous, ranging from simple self-built shacks to solid houses, also often self-built e.g. by the use of self-produced clay bricks.

Examples for this category can be found all around the outskirts of the city, often side by side with former ‘wild’ settlements. They have often developed from more or less informal allotments – as in other cities Viennese allotments were in many cases marked by an informal interim use of provisional and temporary character. Today most of these ‘informal allotment settlements’ are allotments with legalized all-year residences (Eklw zoning) that are no longer traditional allotment structures of temporary character but residential areas with mostly privately owned plots.

Grade 01 – Defect Settlement: This category describes a ‘wild’ settlement that is (at a given time) in the process of transformation from a mainly illegal to a legal respectively formalized settlement. Informal (illegal) and formal (legal) characteristics co-exist. The persisting deficiencies may lie on different levels. For instance, there might still be an infrastructural shortcoming – e.g. no connection to sewerage – or a location in a zone without a building area designation.

Examples for this category are all types of former ‘wild’ settlements, regardless of their origin. The duration of the formalization process can vary significantly depending on site-specific parameters or the progress of the negotiations between settler associations and the municipality.

Grade 0 – Formalized Settlement: It is a former ‘wild’ settlement whose illegal aspects have been dissolved. The connection to the infrastructural systems of the city has been fully established. Additionally, the settlement has been transferred into an official zoning category that corresponds to the actual use. Today almost all former ‘wild’ settlements have either been cleared or are fully integrated into the formal system of the city. Since in most cases the plot structure and residential use have been preserved, the former ‘wild’ settlements are now a substantial part – not least in quantitative terms – of the extensive suburban layer within the municipal boarder of Vienna.

Overall, the degree of integration or the persistence of the ‘wild’ settlements in Vienna is astonishing. Today, they have largely mutated into single-family housing estates and thus contributed to the consolidation of suburban settlement structures within the urban area: More than 70% of today's allotment gardens (Eklw) and garden settlements (GS) and 42% of the low-density residential areas (W I) dominated by single-family houses go back to an informal origin.Footnote67

Problematization

From the perspective of the concept of order in concerted urban planning, the expansive ‘wild’ settlements posed a major challenge from 1918 at the latest, especially in a time period when the discipline of urban planning and urban design was still forming and consolidating. As a ‘reverse form of urban planning’, the informal city also influenced the development of planning instruments.Footnote68 The primary conflict was certainly caused by the contradiction of building regulations and the specifications of defined zoning categories. In particular, the location of a large number of ‘wild’ settlements in the protected area Wald- und Wiesengürtel (Forest and Meadow Belt) was bound to cause lasting irritation. In addition, the often illegal taking of land contradicted the principles of the modern constitutional state and liberal democracy, which is based not least on the right of ownership of land. The composition of the ‘wild’ settlements, which often appeared as mixed settlements, also contradicted modern concepts of differentiated zoning. At the level of the city as a whole, the ‘wild’ settlement clusters appeared as a threatening disorder. This meta-level of perception, which contrasted order and chaos, was also accompanied by – implicit or explicit – aesthetical and ideological reservations.

The Viennese Garden City Movement of the interwar period and its ‘Messy Sister’

The Viennese Garden City Movement was an influential current at the beginning of the Austrian First Republic, a circumstance which was also expressed on an institutional level. In 1919, a Siedlungsamt (Settlement Office) was founded, and in 1921 the Gemeinwirtschaftliche Siedlungs- und Baustoffanstalt GESIBA (Public Settlement and Building Materials Institution), which supplied legal settlements with building materials at low cost, was established. Prominent architects of the time such as Adolf Loos and Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky worked for the Siedlungsamt and propagated a future development of the city of Vienna according to the principles of the International Garden City Movement. This current, which was also firmly anchored in the Social Democracy, would be on the defensive in the planning discourse in the mid-1920s (see below).

In 1926, the movement published the monthly periodical Der AufbauFootnote69 for one year. The authors propagated a further development of Vienna according to the principles of the garden city model. Interestingly, the phenomenon of ‘wild’ settlements – which at least the Viennese authors had to be aware of – is rarely mentioned directly. But it is precisely in their eloquent absence that the ‘wild’ settlers and their chaotic manifestations, as a ‘disorderly sister movement’, take on a key role in Der Aufbau. With the support of international comrades-in-arms, the proponents of orderly development had to distance themselves from a predominantly spontaneous and disorderly grassroots movement in order to be able to propagate their idea of a collectivist-oriented ‘city of gardeners’. This model of a top-down planned synthesis of city and countryside had to distance itself from a supposedly possessive individualist-oriented informal settlement activity that was perceived as detrimental to the common good. Architect and co-editor of Der Aufbau Franz Schacherl writesFootnote70:

From the pile of shacks and huts resembling a gypsy camp, built by individualistic, solitary, property-addicted people, to the uniformly planned cooperative settlement with five-room houses, there was an arduous journey to be made. From the house, made of box lids and fence scraps, roofing felt and tin scraps, the open heap of manure and the mass latrine, to the two-storey property with a cellar, brick-built, reinforced concrete ceilings and sewage system, there was an admirable achievement to be made.

Red Vienna's turning away from the settlement movement

After a decisive change in the mayor's office from Jakob Reumann, who was considered a supporter of the formalized settlement movement, to Karl Seitz – both Social Democrats – in 1923, the advocates of a social housing programme in multi-storey construction gained the upper hand. At the same time, support was withdrawn from the official and legal settlement movement that had been promoted between 1921 and 1923.Footnote72 The reasons for this break in social democratic spatial policy in the mid-1920s have been the subject of debates. From the point of view of the research results available here, it can be assumed that the continuing and – as has been shown – by no means halted ‘wild’ settlement activity in the mid-1920s contributed to the shift away from the typology of the settlement. It was no longer seen as an answer to the ‘housing question’ – apart from the fact that in multi-storey residential construction more dwellings can be built more efficiently with a given budget in a given area. In addition, the suspicion of a growing ‘petit-bourgeois attitude’ associated with one's own settlement house and the garden may also have contributed to the turn towards the collectively oriented residential courtyard. The cooperatively organized housing projects with close ties to social democracy remained – as has been shown – in the minority.

In the Austrofascist (1934–1938) and the subsequent (1938–1945) Nazi Regimes, there was an ideological renaissance of the settlement typology.Footnote73 However, this was oriented towards anti-urban ideas of order derived from fascist doctrine, with which settlement structures that arose spontaneously ‘from below’ could not be reconciled. The ‘wild’ settlements were also thematized and denounced as undesirable developments during the Nazi period.Footnote74 This period still needs to be examined more closely in terms of how the manifestations of informal urbanization in Vienna are dealt with.

Post-war period – intensified confrontation with the ‘problem of the “wild” settlement’

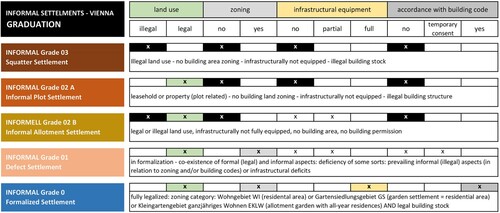

After 1945, in the incipient phase of reconstruction, Viennese urban planning had to reform and realign itself. Reconstruction measures and development issues were discussed in parallel. A comprehensive survey of the city revealed, among other things, a largely fragmented periphery characterized not least by extensive ‘wild’ settlements. Under this impression, the Enquete für den Wiederaufbau der Stadt Wien (Enquete for the Reconstruction of the City of Vienna) 1945–1946 already called the prevention of further ‘wild’ settlements an ‘urgent emergency measure’. In the monthly magazine Der AufbauFootnote75 – not in succession of the 1926 magazine – published from 1946 onwards by the Stadtbauamtsdirektion (City Planning Directorate), the ‘problem of the wild settlement’ became the subject of intensive debates. This is reflected in a series of articles devoted to the subject from the late 1940s to the mid-1960s. But also, in thematically wide-ranging texts on different aspects of urban development, the ‘wild’ settlements appear repeatedly as a disturbing factor. In 1952, in the publication Stadtplanung für Wien by architect Karl H. BrunnerFootnote76 – head of Urban Planning in Vienna 1948–1952 – the description of the necessity of redevelopment of settlements takes up considerable space. Of the total 215 pages of the planning concept, 17 pages are devoted to the phenomenon alone, no less than 8% of the entire publication. In the same year, the 8-Punkte-Programm des sozialen Städtebaus (8-point programme of social urban development) Footnote77 was adopted. Here point 6 is also dedicated to the ‘redevelopment of wild settlements’. In 1962, in the Planungskonzept Wien (Vienna Planning Concept)Footnote78 by architect Roland Rainer – head of Urban Planning Vienna between 1958 and 1962 – the remaining informal settlement structures are still a topic, albeit mostly implicit.

Inventories and structural analyses

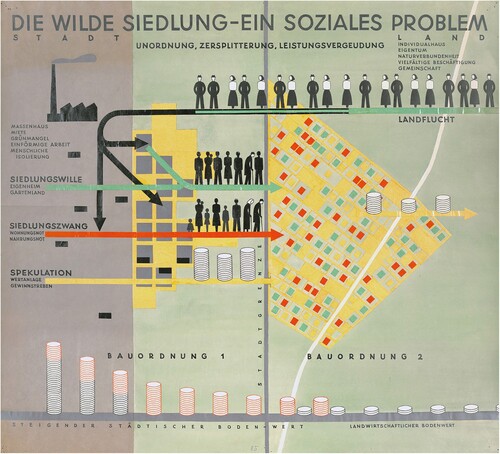

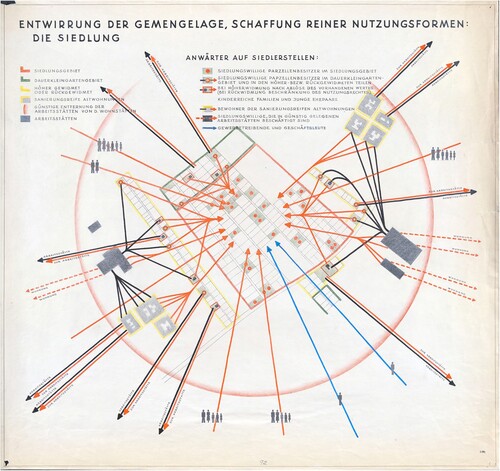

In the post-war period, a number of studies were commissioned by the city planning authorities to provide an inventory of the ‘wild’ settlements. An early study, which can be dated to 1949Footnote79 contains inventories of individual ‘Gemengesiedlungen’ (mixed settlements), as well as discussions of their location in the urban area. Furthermore, a number of interesting diagrammatic representations are provided, that negotiate socio-spatial contexts in the emergence of a ‘wild’ settlement ( and ), as well as concepts for an ‘disentanglement of the mixed situation’ (discussed later).

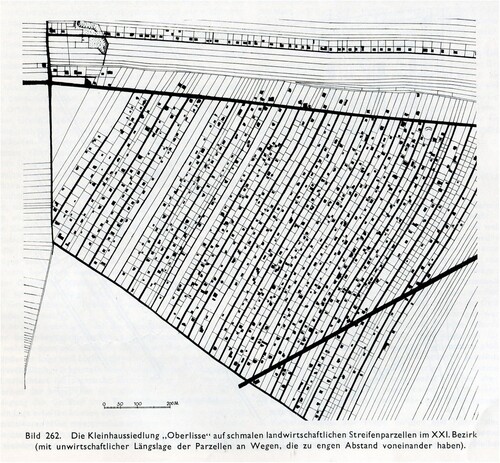

The structural analysis of typical arable settlements contained in the study is particularly illuminating. Typically, these compounds arose on subdivided farmland which was sold or leased to settlers (often via middlemen). The settlement of the arable fields followed the logic of a linear sequence of longitudinally oriented plots. The quantitative analysis (cf. ) shows that arable settlement – a typical ‘informal plot settlement’ – was the most widespread morphological form of ‘wild’ settlement, accounting for between a quarter and a third of all informally occupied areas.Footnote80 This spatial-structural setting lacks an overarching spatial context or a balance between private and public or communal use of space. Since the arable settlements also have a high number of development axes, a subsequent upgrade with paved roads was therefore considered an uneconomical undertaking. The inhomogeneity of the forms of use and development, the juxtaposition of fallow land, garden plots, board huts and solid settlers’ houses is graphically problematized. The heterogeneously composed community settlement contradicted an understanding of pure forms of use that was considered advanced and was a fundamental principle of modern zoning.

Tidying up the urban fringe as an urgent task

In the 1950s, Viennese planning discourse problematized the spatial and functional fragmentation of the urban fringe and the surrounding countryside as a ‘major problem of order’.Footnote81 In 1956, the XXXIII. Kongress für Wohnungswesen und Städtebau (XXXIII Congress for Housing and Urban Development) was held in Vienna, accompanied by an exhibition Die Stadt von Heute und Morgen und ihr Umland (The City of Today and Tomorrow and its Surroundings). The Viennese urban planning department presented the ‘chaotic outskirts’ of Vienna on its display boardsFootnote82 (). Analytical mapping showed in particular the insufficiently guided urban development on the southern edge and especially in the areas north of the Danube, where ‘a mixture of settlements, factories, storage areas, allotment gardens, market gardens, town and gravel pits’Footnote83 had developed between the old rural villages. The ‘wild’ settlements – or ‘mixed settlements’ – were identified as a decisive factor of disorderly development and were also made jointly responsible for a general ‘density problem’.Footnote84 The urban fringe was presented as a loose patchwork composed of outsourced functions (industry, urban infrastructure), low-rise settlements – a large proportion of which are ‘wild’ settlements – and sub-areas of urban agricultural use. The thematization of the interlocking of urban structures and genuinely rural forms of use can be seen as an early preoccupation with the zone between city and countryside, which the German urban planner Thomas Sieverts was to describe and introduce into the discourse some forty years later as a more or less autonomous ‘Zwischenstadt’Footnote85 (Inbetween City).

Figure 7. ‘Chaotic city fringe – the big problem of order’. Source: XXXIII. Kongress für Wohnungswesen und Städtebau 1956 (XXXIII Congress for Housing and Urban Development) was held in Vienna, accompanied by an exhibition ‘Die Stadt von heute und morgen und ihr Umland’ (The City of Today and Tomorrow and its Surroundings). Display board: WStLA Fotoarchiv Gerlach FC1 17328.

Handling ‘wild’ Vienna in post war Vienna

Given the expansion of informal settlements in Post War Vienna the resistance to the persistence and emergence of informal settlements was strongly articulated. In retrospect, five main ways of addressing the phenomenon can be identified:

Combating and preventing ‘wild’ settlements

Concepts of disentanglement

Reform concepts

Channelization

Pragmatic integration (formalization)

The various forms of dealing with the phenomenon often existed side by side with changing emphases. They represented not least the attitude of individual actors in urban planning and positions in an ongoing discourse.

Combating and preventing ‘wild’ settlements – legal and didactic aspects

On the legal level, a distinction was made between preventive and repressive measures against ‘wild’ settlements. As a preventive measure subdivision of land should only be possible after approval by the building authorities.Footnote86 Furthermore, a prohibition of land divisions without connection to the road network and basic infrastructure (water, sewage system, electricity) was demanded. The practice of private land subdivision was thus seen as the origin of all undesirable developments, as a potential prelude to illegal settlement activity. This circumstance also points to the fact that in the post-war period the self-help emergency project of ‘wild’ settlement had become a lucrative business for many landowners.

As repressive measures, it was proposed to forcefully stop the construction of unlawfully erected buildings, to impose sanctions within the framework of the Administrative Penal Code and to impose penalties for building without a building permit. The reason that these measures could only be implemented piecemeal was not least due to the extent of the ‘wild’ settlement activity and a simultaneous lack of personnel in the responsible departments of the building police. In addition, ‘insufficiently high penalties’Footnote87, i.e. insufficient deterrence, were cited as a reason for the only partial success in curbing ‘wild’ settlements.

A form of ‘soft intervention’ was reflected in the instrument of an informative ‘Bauberatung’ (building consultancy) that was intended warn against the uncertainties and pitfalls of ‘wild’ settlement activity. Early on, in the context of the Enquete für den Wiederaufbau der Stadt Wien (Enquete for the Reconstruction of the City of Vienna) 1945–1946, ‘detailed proposals for the design of building consultancy’Footnote88 were elaborated. In order to prevent more ‘wild’ settlements, ‘the creation of settlement zones that meet the needs of the building population’Footnote89 was proposed. The ‘entire urban area subject to the supervision of the building advisory service’ was to be divided ‘into zones or sectors’. Each sector was to be headed by an architect, who in turn was to be in contact with the ‘central advisory office’.Footnote90 In particular, the expansion of allotment gardens into further ‘wild’ settlements was to be preventedFootnote91:

In those areas for which allotment garden control commissions have been set up, the field offices of the building advisory service must work in constant contact with these commissions. It must be achieved that in this way any wild building becomes impossible in the future.

Concepts of disentanglement, reorganization and reordering

In the already mentioned early study form 1949 Vom Grabeland zur wilden SiedlungFootnote92 (From kitchen garden to wild settlement), in addition to an inventory of informal settlementsFootnote93, the social and economic causes that favour the emergence of a ‘wild’ settlement were also considered. In a diagrammatic presentation (), both social need – housing shortage and food shortage – and the will to settle – the longing for one's own home and garden land – are named as triggers for informal urbanization. In addition, the speculative interest of private actors motivated by the pursuit of profit, in other word trading land as an investment, is held responsible for the undesirable development. A vertical line divides the diagram into two parts, symbolizing the city boundary, which since 1920/21 has also been a federal state boundary and thus also separates two building codes. The background to this is the observation that many ‘wild’ settlements have accumulated immediately outside the city boundary and thus elude the regulatory grasp of the Viennese planning authorities. In further site plans and diagrams, proposals are made for disentangling the mixed situation both at the level of the city as a whole and at the level of the individual ‘wild’ settlement or communal settlement. The aim of the outlined manoeuvres should be the creation of ‘pure forms of use’Footnote94 (), separating permanent allotments – pure garden use without residential use – from settlements of primary residential use and sub-areas that should be put to a higher use (industry, transport) or rezoned – into farmland or forest and meadow belt. At the higher level of the city as a whole, an exchange and steering point was proposed.Footnote95 Depending on the location of the workplace, it should organize the ‘allocation to a settlement area’Footnote96 (favourable location to shorten the commute to work) and, depending on the location of the dwelling, the allocation to a nearby allotment garden area. ‘Pure forms of use’ should replace the mixed-use situation and be brought into a spatial proximity in accordance with the everyday routes: First separation then reorganization.

Figure 8. ‘The wild settlement as a social problem’: Source: ‘Vom Grabeland zur wilden Siedlung’ (From kitchen garden to wild settlement), study ca. 1949, archive MA18 SEP-P05226.

Figure 9. ‘Disentanglement of the mixed situation, creation of pure forms of use’. Source: ‘Vom Grabeland zur wilden Siedlung’ (From kitchen garden to wild settlement), study ca. 1949, archive MA18 SEP-P05226.

The ‘disentanglement’ was then to take place only at the level of individual settlement structures, within the framework of a complex process of formalization. This should – after infrastructural upgrading and subsequent readiness for building – aim at transferring as many sub-areas of the informal city as possible into clearly defined categories of zoning. The reorganization at city level outlined and proposed in the diagram never took place. The inertia of socio-spatial structures and ownership prevented a city-wide reorganization and made only local disentanglements feasible.

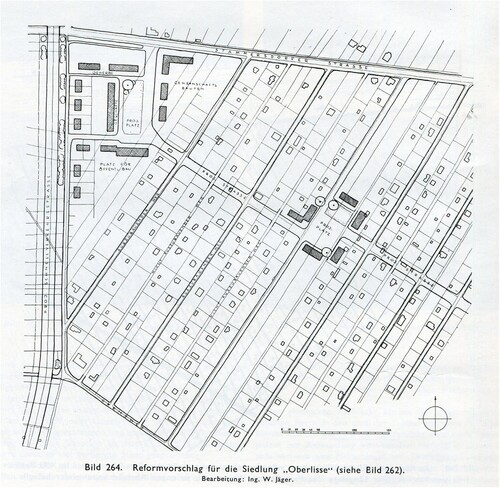

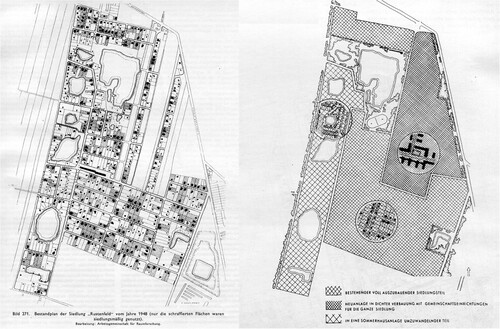

Reform concepts

From the late 1940s onwards, partly very concrete reform concepts of ‘wild’ settlements were developed, which were published and discussed in Der Aufbau.Footnote97 These were developed, for example, by Werner Jäger, head of the later ‘Österreichisches Institut für Raumplanung’ (Austrian Institute for Spatial Planning – ÖIR). These reform approaches were then collected in Karl H. Brunner's ‘Stadtplanung Wien’ (Urban Planning Vienna) of 1952 and presented as solutions to ‘the problem of wild settlements’. A study on zoning as a proposal for ‘disentanglement’ of the settlement Rustenfeld (), which today lies just outside the city limits – is illuminating. According to the concept, a sub-area – characterized by gravel ponds used for bathing in summer was to be re-dedicated as a summer house area (, left side). Other areas were to be upgraded as a purely residential settlement and infrastructurally retrofitted and redeveloped according to building law. A third sub-area of the settlement was to be subjected to a re-foundation in the form of a ‘new development in dense construction’ and accommodate community facilities. A look at today's Rustenfeld settlement shows that Jäger’s and Brunner's transformation concept did not succeed. It is a now legalized monofunctional housing area characterized by single-family houses in an open design layout. Structural densification – in the form of terraced houses and multi-storey housing – has only partially taken place.

Figure 10. Reform concept for the ‘Rustenfeld’ settlement. Source: Brunner ‘Stadtplanung für Wien: Bericht an den Gemeinderat der Stadt Wien.’ 1952, left ‘Gemengesiedlung’: p. 195, right (reform concept): p. 196.

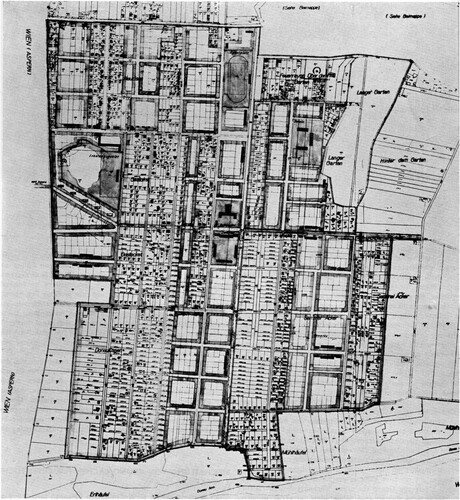

Another interesting structural reform is proposed in Brunner's publication for the typical arable settlement Oberlisse (). Its linear plot logic, based on the arrangement of longitudinal plots in long stretching former arable fields – with a length of up to 900 m – and accessed by a multitude of parallel access paths, should be linked by a transverse connection ( and ). Here, the transverse axis conceptually becomes a community space, which is extended in sections in the shape of a square. There, community facilities can be found as in a traditional village square. The ‘wild’ settlement is thus to be rebuilt and reformed along the lines of the ‘organically’Footnote98 grown village settlement. Of course, without the traditional agricultural use that gave rise to the traditional ‘Angerdorf’ – a settlement built around a village green. The inhabitants of the ‘wild’ settlement work in the region or in the nearby town and have mostly long since lost their connection to the cultivation of land. A look at the current setting of the settlement also shows a structurally unchanged low-rise housing estate as an endless string of single-family houses without any community space.

Channelization (of the will to settle)

A conceptual approach that aimed to contain the ‘wild’ settlement activity sought to channel the ‘will to settle’, which many contemporaries believed ultimately resulted from a tendency to urban exodus, and to recapture the ‘movement from below’. Architect Roland Rainer adopted an overall urban perspective early on in his reflections on Viennese urban planning. He considered land use balances – especially in the already mentioned Planungskonzept (Planning Concept) of 1962 – and was already working on his concept of Verdichteter Flachbau (dense low-rise housing) in the 1950s. The uncontrolled land consumption of the ‘wild’ garden city was to be replaced by structurally dense low-rise housing estates, which were composed of the basic unit ‘house with private garden’. However, the garden cell was confined to 50–150 square metres.Footnote99 By the end of the 1950s, ‘the economic miracle’ had long since set in, and ‘wild’ settling as a symptom of acute need could no longer be recognized by Roland Rainer. Accordingly, in his concept the garden plot loses its function as an emergency reserve, as a production area for at least partial self-sufficiency, and becomes purely a recreational area, ultimately an extension of the living room. Rainer's version of the garden city is a future city of leisure freed from all the ravages of the past. The social hardship that produced the ‘wild’ settlement is pushed into the background, the ‘will to settle’ is derived from a persistent anti-urban attitude (urban exodus). Rainer's ‘dense low-rise housing’ represents an attempt at a further synthesis of city (density) and countryside (garden), albeit no longer with the radicality of Ebenezer Howard's garden city model.Footnote100 Roland RainerFootnote101 writes:

But as long as the need for personal and nature-connected dwellings cannot be satisfied in an economically viable and urbanistically legal way, one will not be able to cope with the illegal satisfaction of these elementary needs by the so-called ‘wild’ settlements with their terrible destruction of the landscape around Vienna, and thus also with the enormous, subsequent expenditure for roads, sewage systems, etc. in these quite uneconomically laid-out areas.

Pragmatic integration (formalization)

As early as the 1920s, the municipality began to formalize ‘wild’ settlements on the level of infrastructural equipment and legally in terms of zoning and building law. In the immediate post-war period, the departments of urban planning continued this formalization process where it was left off in 1938. Informally created settlement structures were integrated into the formal city without much noise. This form of more or less ‘silent pragmatic integration’ was to dominate the next decades. First of all, infrastructural retrofitting had to take place. The connection to the road network, to the sewage system, electricity and water corresponded to a subsequent submission for the approval under building law. This in turn was a prerequisite for baurechtliche Sanierung (redevelopment under building law), i.e. the integration into an official zoning category. Often, pragmatic integration was what remained of reform concepts. In some areas, however, reform concepts have left their mark. One example is the community of Essling that today belongs to Vienna's 22nd district Donaustadt. As early as the 1940s, the planning community had become aware of the widespread farmland settlements south of the original Essling village centre. In Brunner's Stadtplanung Wien (Urban Planning Vienna) there is an elaborate ‘Study for the Redevelopment for the Purpose of Subsequent Creation of a Community Structure’ of the ‘Strip Settlements in the Southern Area of Essling’ ().Footnote102

The entire area was to be developed with paved roads, sewers, electricity and water, and as yet unsettled farmland was to be built on with closed rows of terraced houses in accordance with the orderly structure of the garden city. 25% of the development zones were to be transferred to public property and used for public amenitiesFootnote103 such as sports facilities, recreation areas, schools and administrative facilities.Footnote104 Here, too, the initial ‘wild’ settlement became the crystallization point of an expansive suburban development.Footnote105 The proposed update here is denser in form – namely rows of terraced houses – to mitigate the original density problem. The current state shows the southern area of Essling as a relatively homogeneous residential area dedicated ‘WI’ (construction class I). Partial areas are allotment settlements for year-round living (Eklw) – a category introduced by an amendment to the Viennese allotment garden law in 1992 – while only a small portion is a garden settlement area (GS). Single-family house development still dominates; in some cases, there have been plot mergers resulting in terraced house projects or multi-storey residential buildings, although these are not social housing but commercially oriented real estate projects. Here, too, the original reform concept had to give way to pragmatic integration. What has been preserved, however, is a central strip of public land (former arable field), which today, as proposed by JägerFootnote106 and BrunnerFootnote107, contains public infrastructure (sports facilities and school). It received zoning as public park area and further south in the transition to the Nationalpark Lobau (Lobau National Park) as a Schutzgebiet Wald- und Wiesengürtel (protected area forest and meadow belt).

Discussion and conclusions

Due to their large number and the vast territories they occupied, Vienna’s ‘wild’ settlers were a critical and hence politically relevant mass. By the early 1960s out of the challenge of sheer numbers a decision for a process of gradual integration of informal structures into the formal system of the city was made. There was no manifesto of pragmatism, since it was a process of learning by doing. The inertia of socio-spatial structures and ownership prevented a city-wide reorganization and made only local disentanglements feasible. Repeated states of exceptionFootnote108 in Vienna's history of the twentieth century generated facts on the ground in the form a huge informal ‘grand projet’ of the many without an author nor a driving collective idea. It could no longer be fundamentally questioned in phases of consolidation and rehabilitation of order and law. The resettlement of tens of thousands of Viennese would in itself have been another large-scale project that was organizationally, legally and politically not worth the huge effort and cost. Moreover, there was no demographic growth pressure in Vienna in the corresponding decades.

However, the ‘silent work’ on infrastructural upgrading and ‘legal rehabilitation’ of the formerly ‘wild’ settlements, which was hardly noticed or discussed in the general public at the time, also encouraged a lengthy suburbanization process that had far-reaching consequences for all Viennese, as it severely limited the scope for later urban expansion within Vienna's municipal territory. The transfer of the informal margins into the formal city has solidified a suburban development layer within the Viennese urban area that is still significant today and limits the scope of today’s fast growing city.

This occupation of urban land has an ongoing influence on the availability and price of land and the affordability of housing. The 1992 amendment to the allotment garden law, which introduced the zoning category ‘Eklw’ – recreational area allotment garden for permanent residence – and thus transformed allotment garden zones into de facto building land, led to a renewed push of suburbanization. Since the city boundary is also the boundary between federal states and thus separates two administrative districts and tax areas from each other, politicians and city administration felt compelled time and again to encourage Viennese to remain within the city area, not least by endorsing land-intensive and short-sighted suburban settlement structures.

Figure 12. ‘Study for the Redevelopment for the Purpose of Subsequent Creation of a Community Structure’ for the area ‘Essling Süd’, district ‘Donaustadt’, Vienna Source: Brunner, ‘Stadtplanung Wien’, 192, p. 266.

Contextualization: The periodization and contextualization of ‘Informal Vienna’ undertaken here for the first time shows the implication of wild urbanization for the city as a whole ( and ). It also highlights the extent to which the phenomenon of ‘wild’ settlements has been neglected in the context of Viennese urban planning history. The method of a contemporary historical evolutionary perspective on urban planning applied here ‘addresses the interrelation between “episodes” of governance and the broader socio-economic and political context'.Footnote109 It proves how ‘systematized overviews can add considerable explanatory value to how urban planning and urban development relate'.Footnote110 In a dialectical approach, the consideration of informal urban development as ‘The reverse of urban planning’Footnote111 can contribute to illuminating the history of ideas of urban planning and the evolution of planning instruments. Planning in this sense is always both a reactive and a proactive discipline, arising in specific territorial as well as temporal-historical contexts. The history of how Viennese planning authorities dealt with the manifestations of informal urban production is especially illuminating. The threatening disorder and the supposed chaos of ‘Informal Vienna’ were countered with shifting and developing ideas of order. In the synopsis of planning dispositions and real development a field of tension was created from which future guiding principles and new instruments are derived.

Particularly when considering the area balances () and the quantitative comparison of the housing units created in the context of informal as well as formal urban production, it becomes apparent that ‘wild’ settlements represented a significant factor in the general housing supply from 1918 until the 1960s. Informal Vienna hereby significantly relieved the pressure on Red Vienna.

Typology: The ‘gradation of the informal’ proposed here () is a systematic approach that enables a differentiated consideration of the various levels that the informal can have in relation to the formal. Our Typology and Graduation of Informal Settlements developed for the Viennese context allows a differentiation in type and process. It has to be discussed if it is possible to generalize it for other cities and contexts.

The informal needs a formal frame of reference and vice versa. In addition, the recording of the shades of the informal allows the reconstruction of formalization processes over time that can serve as a tool to evaluate the significance of case studies. An important derivation from this is the perspective of the instability of the socio-political and spatial meaning of settlement structures when viewed over time. In the case of Vienna’s ‘wild’ settlements both visible manifestations and invisible parameters were and still are in a state of flux, an evaluation can therefore only take place critically and historically. The mere evaluation of ‘frozen images’ and maps cannot deliver a resilient narrative. This legalistic and urbanistic categorizationFootnote112 that differentiates certain settlement types should – in combination with a morphological approachFootnote113 – contribute to elaborating the complexity and processual quality of the phenomenon. A gradual distinction between the formal and the informal system is possible when specific parameters are taken into consideration (). This is to be discussed with approaches that put a stress on the intrinsic merging of informal and formal aspects of the city.Footnote114

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Thomas Bozzetta, Brigitte Ott, Andreas Hofer, Angelika Psenner, Johannes Suitner, Peter Eigner and Susanne Tobisch for their support in the project and Christoph Sonnlechner, Nikolaus Schobesberger, Mario Marth and Marion Kreindl of the City of Vienna for facilitating their research. Both authors are also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Andre Krammer

Andre Krammer was trained an architect/urbanist in Vienna, Austria. He has project expertise in architecture and urban planning. His research areas include the interrelations between formal (top-down) urban planning and informal (bottom-up) urban development, architectural and urban planning history and discourse. He is currently lecturer and researcher at TU Wien's urban design research unit and is co-editor of dérive - magazine for urban research.

Friedrich Hauer

Friedrich Hauer was trained an architect/urbanist and historian in Vienna, Austria. Since 2010 he has been a member of various interdisciplinary working groups on urban development and urban environmental history, focusing on questions of urban morphology, urban metabolism and infrastructures. He is currently lecturer and PostDoc researcher at TU Wien's urban design research unit.

Notes

1 Krammer and Hauer, “Bidonvilles, Fischkistensiedlungen, Bretteldörfer. Anmerkungen zur informellen Raumproduktion in Europa”; Chiodelli, “Juggling the formal and the informal: The regulatory environment of the illegal access to public housing in Naples”

2 UN Habitat, “The challenge of Slums”

3 Davis, “The Planet of Slums”

4 De Soto, “The other path: The invisible resolution in the Third World”

5 Saunders, “Arrival City: How the Largest Migration in History Is Reshaping Our World”

6 Ibid.

7 Manzano, “La urbanización informal en Europa en el siglo XX: una historiografía”

8 IJURR Magazine – International Journal of Urban and Regional Research Volume 43, Issue 3.

9 Blanc-Chaleard, “En finir avec les bidonvilles. Immigration et politique du logement dans la France des Trente Glorieuses”.

10 Sekulic, “Glotz nicht so romantisch! On Extralegal Space in Belgrade”; “The extra-legal production of space in Belgrade during socialism and after”.

11 Mitrovic, “Informal growth of housing in Belgrade under the impact of transition to global economy”

12 Pojani, “Urban form of informal settlements in the Western Balkans”.

13 Pojani and Baar, “The legitimacy of informal settlements in Balkan States”.

14 Rocco and Ballegooijen (Eds.), “The Routledge Handbook on Informal Urbanization”.

15 Agamben, “State of Exception. Homo Sacer II”

16 Mukhija & Loukaitou-Sideris, “The informal American city: Beyond taco trucks and day labor”; Iveson et al., “The informal Australian city”.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid. 2.

19 Tafuri, “Vienna rossa: la politica residenziale nella Vienna socialista”; Blau, “The architecture of Red Vienna, 1919–1934”.

20 Pirhofer, “Pläne für Wien: Theorie und Praxis der Wiener Stadtplanung von 1945 bis 2005”; Korthals and Faludi, “Why the greening of Red Vienna did not come to pass: An unknown chapter of the Garden City movement 1919–1934”.

21 Altfahrt, “Die Zukunft liegt in der Vergangenheit”; Novy and Förster ”Einfach bauen: Katalog zu einer wachsenden Ausstellung”; Frei, “Die Arbeiterbewegung und die ‘Graswurzeln’ am Beispiel der Wiener Wohnungspolitik 1919–1934”; Baldauf et. al. “Study across Time: Glancing Back at Vienna’s Settlers’ Movement”

22 Marcuse, “A Useful Installment of Socialist Work; Housing in Red Vienna in the 1920s”. 565.

23 Hoffmann, “Die Geschichte vom ‘Bretteldorf’ – ‘Wilde’ Siedler gegen das Rote Wien“; Zimmerl, ”Kübeldörfer: Siedlung und Siedlerbewegung im Wien der Zwischenkriegszeit”.

24 Holzschuh, “Wien. Die Perle des Reiches: Planen für Hitler“; Weinberger, “NS-Siedlungen in Wien. Projekte, Realisierungen, Ideologietransfer”; Suttner, “Das Schwarze Wien. Bautätigkeit im Ständestaat 1934–1938”.

25 Brunner, “Stadtplanung für Wien: Bericht an den Gemeinderat der Stadt Wien”. 185–201; Rainer, “Planungskonzept Wien”. 64–72, 154–195.

26 Diefendorf, “Planning postwar Vienna”; Eigner and Schneider, “Verdichtung und Expansion. Das Wachstum von Wien”; Csendes and Opll, “Wien: Geschichte einer Stadt. 3: Von 1790 bis zur Gegenwart”; Pirhofer and Stimmer, “Pläne für Wien: Theorie und Praxis der Wiener Stadtplanung von 1945 bis 2005”

27 Ziak, “Wiedergeburt einer Weltstadt. Wien 1945–1965”.

28 Lichtenberger (most publications in German) exception, “Vienna: Bridge Between Cultures”.

29 Machat, “Land in der Stadt. Kleingärten und Siedlungen in Wien”; Mattl, “Lob des Gärtners. Der Krieg und die Krise der Urbanität”; Autengruber, “Die Wiener Kleingärten: von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart”

30 Hauer and Krammer, “Wilde Siedlungen und rote Kosakendörfer. Zur informellen Stadtentwicklung im Wien der Zwischenkriegszeit”; “Das Wilde Wien. Rückblick auf ein Jahrhundert informeller Stadtentwicklung”; “Bidonvilles, Fischkistensiedlungen, Bretteldörfer. Anmerkungen zur informellen Raumproduktion in Europa”.

31 This work is a product of the research project “Wien Informell – Informelle Stadtproduktion 1945–1992” funded by Jubiläumsfonds der Österreichischen Nationalbank (OeNB) under grant number 18584.

32 Hauer and Krammer, “Tracing the informal fringe: A large-scale study of 20th century ‘wild’ settlements in Vienna, Austria” (forthcoming).

33 Landwehr, “Historische Diskursanalyse”.

34 Stadtbauamtsdirektion Wien, “Der Aufbau„ (1946–1918).

35 Hauer and Krammer, ”Tracing the informal fringe: A large-scale study of 20th century ‘wild’ settlements in Vienna, Austria” (forthcoming).

36 Ibid. sections 3.1–4.1.

37 Brunner, “Ein Jahr Stadtplanung für Wien.” 501.

38 Hauer and Krammer, “Tracing the informal fringe: A large-scale study of 20th century ‘wild’ settlements in Vienna, Austria” (forthcoming), section 4.

39 Wiener Stadt-und Landesarchiv (WStLA), Sign. 1.3.2.223b. A13.

40 Hoffmann, “Die Geschichte vom ´Bretteldorf´ – ´Wilde´ Siedler gegen das Rote Wien”.

41 Hauer and Krammer, “Tracing the informal fringe: A large-scale study of 20th century ‘wild’ settlements in Vienna, Austria” (forthcoming), section 4.2.

42 Area comparison and estimation, see: Vienna’s informal fringe 1918–1938–1956 Source: Friedrich Hauer & Thomas Bozzetta, basemap: data source – Stadt Wien.

43 For the time around 1950 it is safe to estimate the (at least semi-permanent) population of Vienna’s ‘wild’ fringe at above 100,000 (Brunner, Citation1949: 501) in a city of 1.6 million.

44 Brunner, “Ein Jahr Stadtplanung für Wien.” 501.

45 Blau, “The architecture of Red Vienna, 1919–1934”.

46 Novy and Förster, “Einfach bauen: Katalog zu einer wachsenden Ausstellung”

47 Bobek and Lichtenberger, “Wien: bauliche Gestalt und Entwicklung seit der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts”.

48 UN Habitat ”The Challenge of Slums” (foreword).

49 Ibid. S. 12.

50 AlSayyad, “Urban Informality: Transnational Perspectives from the Middle East, Latin America, and South Asia”.

51 Ibid.

52 Ibid; De Soto, “The other path: The invisible resolution in the Third World”

53 AlSayyad, “Urban Informality: Transnational Perspectives from the Middle East, Latin America, and South Asia”; Rakowski, “Contrapunto: The Informal Sector Debate in Latin America”.

54 AlSayyad, “Urban Informality: Transnational Perspectives from the Middle East, Latin America, and South Asia”; De Soto, ”The other path: The invisible resolution in the Third World”.

55 Ibid.

56 Payne, “Urban land tenure policy options: titles or rights?”.

57 Ibid. 417.

58 Chiodelli, “The production of informal space: A critical atlas of housing informalities in Italy between public institutions and political strategies”; Azzelini and Lanz et. al., “Caracas, sozialisierende Stadt – die „bolivarianische” Metropole zwischen Selbstorganisation und Steuerung”.

59 Novy and Förster, "Einfach bauen: Katalog zu einer wachsenden Ausstellung“; Brunner and Schneider, „Umwelt Stadt. Geschichte des Natur-und Lebensraumes Wien”.

60 Roy and Alsayyad “Urban Informality: Transnational Perspectives from the Middle East, Latin America, and South Asia”.

61 Krzizek, “Gefahren und Bekämpfung des wilden Bauens“; Heiss, “Zum Problem der Wilden Siedlungen“; Bobek and Lichtenberger, "Wien: bauliche Gestalt und Entwicklung seit der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts”.

62 Hauer and Krammer, “Tracing the informal fringe: A large-scale study of 20th century ‘wild’ settlements in Vienna, Austria” (forthcoming), section 3.4.

63 Ibid.

64 Magistratsabteilung 18, ”Vom Grabeland zur Wilden Siedlung“; Jäger, „Organische oder wilde Siedlung. Gedanken zur Sanierung der wilden Siedlungen“, Depot MA18, Sign. P 5226.8.

65 Dovey et. al., ”Informal/Formal Morphologies“.

66 Hauer, „Hauer and Krammer, “Tracing the informal fringe: A large-scale study of 20th century ‘wild’ settlements in Vienna, Austria” (forthcoming), section 4.

67 Hauer and Krammer, “Tracing the informal fringe: A large-scale study of 20th century ‘wild’ settlements in Vienna, Austria” (forthcoming).

68 Manzano, “The Reverse of Urban Planning. First Steps for a Genealogy of Informal Urbanization in Europe”.

69 Schacherl and Schuster, “Der Aufbau“.

70 Schacherl, "Das österreichische Siedlungshaus. I. 21.

71 Schacherl and Schuster, “Der Aufbau”. 22.

72 Blau, “The architecture of Red Vienna, 1919–1934”.

73 Weinberger, “NS-Siedlungen in Wien. Projekte, Realisierungen, Ideologietransfer”.

74 Ibid.

75 Stadtbauamtsdirektion Wien, “Der Aufbau” (1946–1918).

76 Brunner, “Stadtplanung für Wien: Bericht an den Gemeinderat der Stadt Wien”.

77 Thaller, “8-Punkte-Programm des sozialen Städtebaus”.

78 Rainer, "Planungskonzept Wien“.

79 Magistratsabteilung 18, “Vom Grabeland zur Wilden Siedlung”; Jäger, “Organische oder wilde Siedlung. Gedanken zur Sanierung der wilden Siedlungen“, Depot MA18, Sign. P 5226.8.

80 Hauer and Krammer, “Tracing the informal fringe: A large-scale study of 20th century ‘wild’ settlements in Vienna, Austria” (forthcoming).

81 XXXIII. Kongress für Wohnungswesen und Städtebau, Exhibition: Wien – Die Stadt und ihr Umland. Catalogue (unnumbered), Display board: WSTLA_Fotoarchiv_Gerlach_FC1_17328.

82 Display board: WSTLA_Fotoarchiv_Gerlach_FC1_17328.

83 XXXIII. Kongress für Wohnungswesen und Städtebau, Catalogue (unnumbered).

84 Display board: WSTLA_Fotoarchiv_Gerlach_FC1_17342.

85 Sieverts, “Zwischenstadt: Zwischen Ort und Welt, Raum und Zeit. Stadt und Land”.

86 Krzizek, “Gefahren und Bekämpfung des wilden Bauens” 374–378.

87 Ibid. 374–378.

88 Maetz, ”Die Enquete über den Wiederaufbau der Stadt Wien (III)“ 132.

89 Ibid.

90 Leischner, "Bauberatung – Warum und Wie?“.

91 Ibid.

92 Magistratsabteilung 18, “Vom Grabeland zur Wilden Siedlung”.

93 Ibid.

94 Magistratsabteilung 18, “Vom Grabeland zur Wilden Siedlung”, Diagrammes: “Entwirrung der Gemengelage”.

95 Magistratsabteilung 18, “Vom Grabeland zur Wilden Siedlung”, Diagramme: “Tausch-und Lenkungsstelle”.

96 Ibid.

97 Stadtbauamtsdirektion Wien, “Der Aufbau” (1946–1918).

98 Jäger, ”Organische oder wilde Siedlung. Gedanken zur Sanierung der wilden Siedlungen“. 517–529.

99 Rainer, “Mensch, Masse und Wohnungsbau”. 225.

100 Howard, "Garden Cities of To-Morrow”.

101 Rainer, “Mensch, Masse und Wohnungsbau”. 224.

102 Brunner, “Stadtplanung Wien“, 192, image 266.

103 Ibid.

104 Ibid.

105 Hauer and Krammer, “Tracing the informal fringe: A large-scale study of 20th century ‘wild’ settlements in Vienna, Austria” (forthcoming).

106 Jäger, “Organische oder wilde Siedlung”

107 Brunner, “Stadtplanung Wien“, 192, Image 266, Supplement XII.

108 Agamben “State of Exception. Homo Sacer II”.

109 Suitner, ”Vienna’s planning history: periodizing stable phases of regulating urban development, 1820–2020” 882.

110 Ibid.; Ward et al. “The ‘new’ Planning Histroy” 241.

111 Manzano, “The Reverse of Urban Planning. First Steps for a Genealogy of Informal Urbanization in Europe”.

112 Chiodelli, “The production of informal space: A critical atlas of housing informalities in Italy between public institutions and political strategies”.

113 Hauer and Krammer, “Tracing the informal fringe: A large-scale study of 20th century ‘wild’ settlements in Vienna, Austria” (forthcoming).