ABSTRACT

Over time, a large number of stakeholders have affected the Italian port city of Naples. The millenary history of Naples reveals a port that has been strongly intertwined with the city. Yet, recent history shows a different story. The historical investigation analysed in this article points out a conflict between several different authorities that led the port. As these developed into separate entities they detached people from the water. This article offers an institutional history. Using the concept of path dependence it argues that a past system of decision-making concerning the development of the port city reinforced the separation of land from water in Naples. Path dependence is understood as a resistance by institutions (rules) and actors (decision makers) to changes in patterns of behaviour and a tendency to repeat previous decisions and practices. This article analyses a series of critical junctures so as to analyse the constellation of actors and decisions which have prevented the city from living with water. The article concludes by arguing that understanding the articulated system of past decision-making is a key to (re)conceptualizing the current state of the city and (re)imagining ways by which the city might be reunited with its waters.

Introduction

Port cities are peculiar landscapes at the intersection of land and water. They form an interconnected spatial entity where a multitude of actors with contrasting motivations, responsibilities and visions have historically influenced planning decisions across different scales. The term actors is used here to describe the range of different people who have played a role in a particular development or political scenario. These could include decision makers, professionals, researchers, community members, companies. Through the lens of specific planning decisions, this article analyzes Naples, a millenary city facing the Mediterranean Sea built around its port. Here, urban and port functions have come to coexist at the intersection of land and water for a long time. It was precisely the port that gave rise to the evolution of the city, built to protect the port and to provide the necessary infrastructures to the city. This intimate relationship between land and water was also reflected in the governance structure of the city. Until the second half of the nineteenth century, those in charge of port planning were also in charge of the city. Specifically, in Naples, for more than two thousand years, the city and port have been backdrops for theatrical acts where kings and colonizers from different cultures competed for the spaces of interaction between the port and the city, and enriching these with architecture and monuments that are now widely regarded as the most beautiful in the world. As a result, the development of the port was planned in conjunction with the city. A detail of the famous Strozzi table () in fact describes this strong link between land and water, between the urban palimpsest and peoples’ lives. The painting depicts a Mediterranean imaginary of a port conceived and planned as a public space on the water, the place of commerce and a natural continuation of the city at sea.

Figure 1. Tavola Strozzi Napoli 1472. Attributed to Francesco Rosselli, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Source: URL: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/dd/Tavola_Strozzi_-_Napoli.jpg

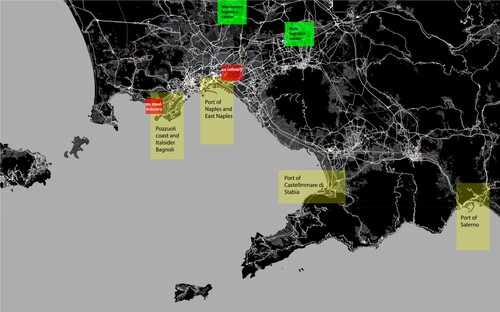

In Naples, as well as globally, from the second half of the nineteenth century industrialization imposed significant infrastructural changes which moved port areas away from city centres.Footnote1 This has undermined understandings of ports as urban entities. It has helped to redefine them as economic machines serving industry in spaces that are detached from the city and popular imaginaries. In the case of Naples, the system of short-sighted and sectoral decisions related to the port planning have trapped the port between two industrial areas: the steel industry in Bagnoli to the west of the city and the oil refinery to the east of Naples. This has prevented actors from integrating the port into the wider territory both infrastructurally and culturally. In Naples the port has become a mental and spatial fracture, which distances people from the sea ().

Figure 2. Map of Naples today with indication of the industrial areas. Both the still industry and the oil refinery have been closed down in the 80s.

This fracture still characterizes the current city, and even though the port authority aims to better connect the port to the larger region, and whilst the municipality and regional authority aim for a larger environmental regeneration of the brownfields around the port area. To find a compromise between these two aims, it is necessary to once more rethink the port as a public square on the sea while retaining its nature as an infrastructural machine. However, past decisions have slowed down processes in ways that today prevent the same authorities from returning to the idea of the port as part of the city palimpsest. As a result, despite many historical changes, the port and city remain spatially distinct and separately governed. These have deeply impacted the territory.

The article looks at the history of Naples through the lens of historical institutionalism and path dependence as the main theoretical framework for investigating whether history can help us understand the planning challenges of today and the future.Footnote2 The article builds upon the PhD dissertation entitled ‘Land in Limbo’ completed by the author in May 2021. The thesis is an indispensable starting point for understanding the history of Naples and, it is hoped, in moving beyond path dependence.

Naples through the lens of path dependence

This article starts with two important assumptions. The first one is that space is an institutional construct. The entire evolutionary history of Naples, its architecture and infrastructure coincides with the history of its institutions, of the actors who in different ways and with different powers, influenced the evolution of the port to the point of dissolving any relationship between city and water. The second assumption, which builds upon the research of the Canadian scholar Andre Sorensen, is that planning institutions are often designed to be difficult to change.Footnote3

As for the concept of institutions, there are many possible definitions depending on the disciplines and scope of the analysis. For the purpose of this study, we will refer to institutions as a system of formal and informal rules that organize social, political and economic relations.Footnote4 According to Sorensen, institutions within political and planning organizations have a tendency to persist over time and to reinforce each other. According to this perspective, spatial changes can no longer be understood only as a sequence of chronological events but rather as strongly interconnected to the changes in the governance and institutional sphere. The historical developments of cities can be summarized as the history of their institutions, as the evolution of a complex and articulated system of decisions, rules, codes of conduct and practices developed over time.Footnote5

This article offers an institutional history using the concept of path dependence as a theoretical tool for interpreting actors’ interactions and better understanding the spatial condition of Naples. The use of path dependence has a dual purpose. It is used as an interpretative tool to understand the spatial condition of the city detached from water due to port transformation. At the same time path dependence is also reconceptualised as a transversal principle to approach the porosities of Naples in the existing governance structure, and in order to move beyond what has been defined as the ‘waiting condition’.Footnote6

The concept of path dependence was first introduced by economists Paul David and W. Brain Arthur mostly to understand economic and social evolutionary dynamics and their inertia mechanisms.Footnote7 Later, the concept was used by other scholars in specific research fields to analyse the phenomena of inertia and institutional rigidity.Footnote8 Only recently has the concept of path dependence been applied to urban studies and port cities thanks to scholars who have argued that awareness of historical practices could help to better understand the current situation and how to overcome obstacles to change.Footnote9

Port cities are by nature path dependent. They are at the intersection of land and water and this frequently means dealing with two different planning approaches, cultural traditions and economic regimes (port and city planing). Their planning is also influenced the concept of time both the time of transformation of the city and port and the temporalities of the transformation of the actors in charge who change according to different speeds and modalities. The overlap of all these factors makes port cities highly path dependent, controversial by nature and therefore an interesting laboratory to understand how history often represents an obstacle to change.

Path dependence is understood as a resistance by institutions and people to change patterns of behaviour and a tendency to repeat decisions and experiences of the past. If, on the one hand, the concept of path dependence refers directly to a problem of governance, on the other hand Fernand Braudel talked about a dimension of inertia linked to space and the geography of places. Braudel in several publications (1997, 2017) discussed long durée as a parameter for measuring space.Footnote10 According to him, the geography and long history of a place also matter and can contribute to path dependence. The geography of a place is the destiny of that place. According to the concept of long-durée, in the geography of a given territory are all the problems and potentialities with which the territory has related and will relate in the future. This basically builds upon Corboz’s concept of land as a palimpsest and which looks at a given territory as something that is written and rewritten and which becomes a heritage in itself.Footnote11

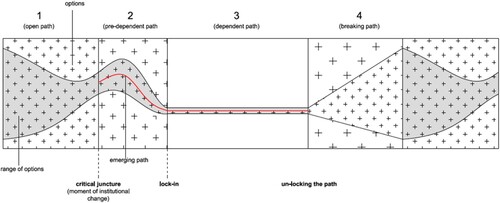

Path dependence thus explains how history matters in the sense that past decisions impact both the present and mostly the future, and how this may be true even if the past circumstances are no longer relevant today. Due to path dependence, actors are used to keeping their positions which limit the possibility for looking for alternatives. The mechanism that guides path dependence () can be schematized through the identification of a series of events (initially contingent choices by the actors involved) that, once established, generate self-reinforcing mechanisms or feedback loops, that contribute to defining a precise trajectory of intervention (locked-in), from which it is very difficult (but not impossible) to deviate and which tends to strongly influence future choices.Footnote12 The breacking paths are new critical junctures that can be understood as windows of opportunities in a specific timeframe. Those can be a change in the governance structure or simply the introduction of new ideas coming from outside the system that migh challenge the current mindset of the actors. Those are difficult for actors recognize and can easily turn into new dependent paths.

Figure 3. Breaking path dependence. Scheme developed by the author based on the model developed by Schreyogg, and Sydow. (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242492187_Subtheme_1_Path_Dependence_and_Creation_Processes_in_the_Emergence_of_Markets_Technologies_and_Institutions_Convenors_Michel_Callon_Raghu_Garud_and_Peter_Karnoe_Organizational_Paths_Path_Dependency_an/figures?lo = 1).

Interpreting Naples through the lens of path dependence means entering the history of decisions, visions of the actors and the transformation mechanisms of the port-city relationship that still influence the present. Historical institutional theory understands critical junctures as processes of relatively rapid institutional change when the course of history changes direction, leading to new developmental pathways. Each of these paths were characterized by a specific morphological structure, a recognizable landscape and a different social and political context. Therefore, each of these junctures introduced different problems, solutions, and imaginaries. This article identifies two main critical junctures in the reconcetualisation of the port transformation and presented as: ‘the port next to the city’ and ‘the port outside the city’. These two critical junctures were times when specific actions put in place by local and national authorities have had the ability to trigger changes in the geography of the port of Naples, creating a fracture related to both space and culture.

The port next to the city

The spatial, social and cultural separations between land and water in Naples are the result of developments in governance structure and planning tools which have their origins in the past.

We can identify multiple moments of change or, using the language of path dependence, critical junctures in the port city’s history. Each of these moments were characterized by a progressive spatial separation of the port from the city and therefore of people from the sea. For centuries and until the second half of nineteenth century, various kings and rulers of the city were also in charge of the port. During that period, port and city stakeholders supported each other to facilitate trade and military activities. The famous Tavola Strozzi from 1472 (see ) illustrates Naples’ growth. It shows the port as a continuation of the city, and the small and compact mercantile city, with a mixture of houses, port warehouses, and social groups that made the market area an iconic place for trade and commerce. Naples was the capital of the kingdom and, therefore, the centre of political and administrative power of all Southern Italy. Until the nineteenth century, the city and port grew together. Piers and docks were built in relation to the urban streets and public squares.

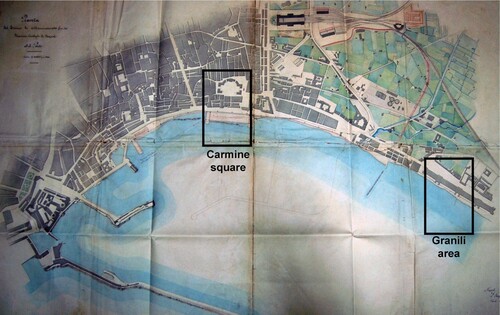

The first significant critical juncture took place in the second half of the nineteenth century. The port city spatial continuity came to an end with the Unification of Italy (1861) which negatively affected the history of the Neapolitan port. The city was no longer the capital of the Kingdom.Footnote13 The centre of political power moved to Turin, thus starting an institutional detachement that marked a decline in trade and port activities. This period saw the construction by the central government of the new port next to the historic city. The decision to build it by the central government was preceded by a long political debate with several architects and engineers bringing forward proposals for the location of the new port. The advantages and disadvantages of the port in the city were discussed for more than twenty years with professionals who believed that a port serving the city had to be close to the city and those claiming that a modern port had to serve the region, and by being located where there was room for new infrastructures outside the city centre. According to professionals, such as the engineer Domenico Cervati (Naples, 1809 – news until 1873), detaching the port from the city would have allowed the city to keep a continuous relationship with the sea and give more space to the city.Footnote14 ().

Figure 4. Port city map of Naples nineteenth century. Source: historical archive municipality of Naples.

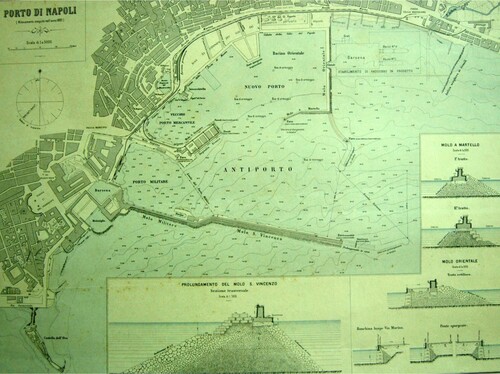

However, despite the pressures from the municipality and from Cervati to build the new port outside the city, the central government decided to construct the port next to the city and designed by the engineer Zainy, on the axis of Carmine square. This interrupted the historic interconnection between land and water in one of the oldest and densest parts of the city ().

Figure 5. The port of Naples in 1889 following the Zainy proposal. Source: historical archive municipality of Naples.

In addition to the spatial fracture, it can be argued that positioning the port in the area of Mercato square was not the best choice from a logistical perspective. The port in fact had already significant infrastructural deficiencies, with goods waiting for weeks on the docks. The port expansion only made the situation worse, reinforcing the climate of uncertainty and governmental fragmentation.

The spatial fragmentation also reflected a fragmentation of the tools. A Royal decree of 1865 was an important turning point in the port legislation, marking the beginning of the separation of the planning tools. It stated that for the ports, such as Naples, which had national and international relevance, port development plans needed to be prepared by the Minister of Public Works.Footnote15 In addition, the state as a unique actor started to fragment into different smaller authorities with diverse visions and interests: the chamber of commerce responsible for the control of the warehouses, the civil engineering office responsible for the construction of the port, the municipality in charge of the areas close to the docks, the public security in charge of access to the port, the port cooperatives that controlled the movement of the goods and finally the customs office responsible for the financial matters.Footnote16 The political distance and the related decentralization of decision-making power played a key role in defining the first interruption of the historical and intimate relationship between port and city.

The port outside the city

The construction of the port outside the city went through two main phases of change: first the petroleum revolution, and later containarisation. The beginning of the twentieth century was characterized by a new significant change in the governance structure which became very centralized. The twentieth century introduced a new imaginary linked to the construction of the modern port that saw a significant impulse starting from the 1920s with the fascist regime. The vision promoted by the regime in Naples was in fact that of modernity through the construction of a new, industrial and efficient port. During the Fascism Regime (1921–1945 circa) new docks and port basins were built to the east of the city.Footnote17 New railway infrastructures and roads started to define the highly infrastructural character of the port, which also created a separation between the port and its ancient city and related history. We can argue that petroleum was an important juncture in the history of the city as the port gradually lost its character as an urban space and became an impenetrable barrier between the city and the sea. The presence of a new power regime manifested in the construction of buildings inside and outside the port. Industries and oil facilities cemented in the collective imagination occupying docks and the areas behind the port.Footnote18 ().

Figure 6. Map of Naples, 1940. Here we see the expansions taking place towards east. Source: URL: https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY∼8∼1∼323465∼90092662:Pianta-della-Cita-di-Napoli–Rappor?sort = Pub_List_No_InitialSort%2CPub_Date%2CPub_List_No%2CSeries_No&qvq = q:naples;sort:Pub_List_No_InitialSort%2CPub_Date%2CPub_List_No%2CSeries_No;lc:RUMSEY∼8∼1&mi = 7&trs = 538#

After the war, the political scene changed again with the establishment of the first Republic starting in 1946 which was in charge of reconstructing the port in the configuration that we see today. Containerization was a second juncture in the history of the city. The arrival of containerization found the port unprepared and, despite a clear vision of an enlarged scale promoted by the port agency, the government planned the port with a vision limited to the city boundary.Footnote19 In the 1960s, the city grew in scale. So too did the port traffic which, nevertheless, remained confined and isolated.Footnote20 Despite the clear need to integrate the port into the urban dynamics, the municipality acted as spectator and was unable to foster the integration of port and city.Footnote21 On the contrary, the city agency contributed to reinforcing the image of separation between land and water. In fact, the various city plans since 1939 have defined the port just as a pattern of colour whose planning was to be delegated to the port agency. Such a way of planning is still visible today in the contemporary city plans.

The 1970s and 1980s introduced new moments of change following an uncontrolled process of growth of the city. This was an opportunity to bring the city back to the water.

From a spatial perspective, the port in this period did not grow much; on the contrary, the city expanded by creating disconnections with the port both towards the west and the east. Large residential neighbourhoods and road infrastructures altered the eastern landscape of Naples, generating dormitory neighbourhoods close to the city that we still see today. The 1980s also saw the collapse of the Italian industrial and production system. Large industries closed down, such as the steel industry in Bagnoli and the refineries of Naples. However, while in other European contexts, the deindustrialization processes were the opportunity to bring people back to water (waterfront regenerations are a tangible example) in Naples the port did not play a strategic role in the territory. On the contrary, national and local authorities still have perceived the port as an element on the edge and disconnected from the city and the larger region ().

How can we move beyond path dependence?

The reading of Naples through the lens of path dependence has highlighted the presence of a cultural approach to the planning of the port as a separate entity from the city, although actors had the chance to select alternative paths or to better use the opportunities (such as deindustrialization processes) to bring people back to the water. Since 2016, the reorganization of the Italian port system through the legislative decree n.169 has created port clusters, an institutional reorganization aimed at providing ports with more efficiency for logistics. This development challenged the urban strategies of many cities and municipalities that are part of the larger regions to which these ports belong. The new governance organization resulted in the creation of the Central Tyrrhenian Sea Port Authority as an entity overseeing the ports of Naples, Castellammare di Stabia and Salerno ().

The centralization of planning powers over an extended region, was a unique opportunity for the different municipalities in charge of urban design in the region, to (re)think, (re)discuss, and (re)design the spatial development of the region and to facilitate a (re)integration of port and city. This certainly was a potential critical juncture. However, this has not yet been followed by a territorial vision that looks at the ports of the region in a systemic and integrated way across the territory. Port authority, and municipality co-exist in the same space still competing for space while lacking common goals, values, tools, and venues to achieve them, leading to a situation where large spaces are still awaiting redevelopment. As a result, an eco-system approach that allows for a (re)conceptualization of the port as new public space is much needed ().

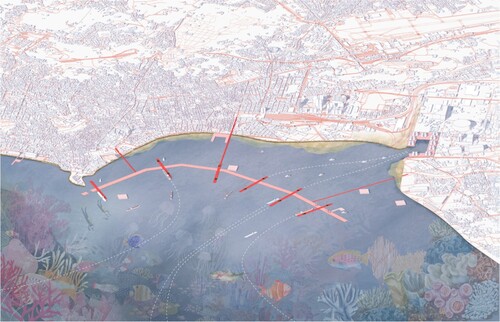

Figure 9. ‘Floating Fiction’ by Giacomo Pimpini, Jiacheng Xu, Matilda Hoffmann, Meng Chen, Sora Kaito. The proposal has been developed within the Course ‘Adaptive Strategies’ AR0110, led by Carola Hein, John Hanna and Paolo De Martino at TU Delft in 2022.

The main challenge for the actors is to recognize the critical junctures as opportunities for change. Why should actors change a path that they consider efficient? What are the incentives to do so? To answer these questions, some scholars have introduced the concept of ‘irritating new perspectives’ or ‘provocative design’ that have the power to shift old paths and make the actors aware of possible and alternative futures.Footnote22 article argues that those provocative scenarios can be generated in academia through design studios and that these can be tools to challenge our current conceptual models, thereby helping decision-makers to move beyond path dependence.

Scenario thinking

This section of the article deals with the theme of the provocative design and the role that scenarios play in the production of new knowledge. The analysis carried out in this article highlights a profound disconnect between land and water as a result of port developments. In the light of the profound changes affecting the city of Naples, including climate change and changing water conditions, contemporary actors need new approaches and ways of reading the territory that should be as integrated as much as possible.

In the case of Naples, the opportunities offered by history have not always been recognized by various actors as opportunities for generating new visions. And that is why this article argues that a change of path can only be triggered by an external shock rather than a slow transition. In this specific case it is argued that the development of (im)possible scenarios can represent a possibility to move beyond path dependence.

As Arie de Geus, one of the pioneers of scenario thinking, once explained: ‘Scenarios are stories. They are works of art, rather than scientific analyses. The reliability of (their content) is less relevant than the types of conversations and decisions they spark’.Footnote23

The idea behind the scenario is to build new imaginaries and narratives to move beyond path dependence. Scenarios do not claim to plan everything, they are not conclusions, rather points of departure. They do not propose final assumptions, rather they can help us to imagine new forms and urban potentials for living with/on water. New (provocative) scenarios can initiate conversations among local stakeholders and help a new generation of people to engage with the critical relationship between land and water.

The scenario becomes an image, a fascination capable of tracing a direction in a context made up of differences, complexities, conflicts and uncertainties. More than assertive projects, the scenario indicates new (im)possible paths, interpretative models and cultural approaches for living with water.

A study carried out by TU Delft students during the Adaptive Strategies course is presented here as an emblematic example of a scenario. The project deals with the port of Naples, with its long-durèe history and with the need to respond in the future to the pressing questions posed by climate change, by asking: how can we imagine resilient visions for the port city of Naples which will allow people to adapt to changing water conditions? The students built their ‘floating fiction’ vision by imagining a fairly extreme scenario, namely the city below sea level by 2100.

The vision for 2100 is a floating and adaptive port-city. It will develop in phases (2050 and 2075), starting with more realistic interventions and moving toward more imaginative futures. A floating structure will be gradually put in place, mirroring the morphology of the existing waterfront. The new floating city is composed of two elements. Firstly, a continuous publicly-accessible path. Transversally to this path, are the transhipment units that allow goods and people to be transferred from large ships to smaller ships that can reach the mainland.

One of the main goals is to free the coastline from the monofunctional and inaccessible port in order to make the coast more accessible and to relocate the port before its flooding. By doing so, a new ecological area in the central part of Naples will provide fertile ground for biodiversity, while connecting the western and eastern neighbourhoods with more efficient means of transport between them. Parts of the existing port will be transformed to welcome new functions which can adapt to the rising water and future scenarios. A new educational network will grow across water and land to support marine and port research and educate learners in social awareness and scientific excellence. The existing industries will be transformed for future needs. Energy will be produced by exploiting the submarine geothermal and the wave-energy potential, supplying energy for the regional port network. Naples will become the prototype for a strategy that can spread throughout the Mediterranean. The floating port is composed of modular elements. Thus, the port can grow or shrink, and parts can travel to other ports where they are most needed ()

Figure 10. New port city development in light of sea level rise. ‘Floating Fiction’ by Giacomo Pimpini, Jiacheng Xu, Matilda Hoffmann, Meng Chen, Sora Kaito. The proposal has been developed within the Course ‘Adaptive Strategies’ AR0110, led by Carola Hein, John Hanna and Paolo De Martino at TU Delft in 2022.

Concluding remarks

Today the dependence that authorities are facing refers to a dependence on a modern culture and planning approach. This approach, however, can no longer tackle contemporary challenges. This article has analysed the recent history of Naples through the lens of path dependence. Path dependence has enabled the identification of some significant critical junctures that have triggered key spatial transformations of the port in response to a shift in governance leading to the two main spatial developments that have been described as ‘the port next to the city’ and ‘the port outside the city’. The history of Naples shows that those transformations to the port were the main reasons behind the spatial, cultural and governance separation of the city and the sea. It also shows the authorities’ resistance to changing patterns of behaviour and therefore traces of path dependencies.

The first spatial transformation has been described as ‘the port next to the city’. The main critical juncture here is represented by the governance shift. It introduced the loss of the economic and political power of the city which marked the beginning of a period of institutional uncertainty. This also reflected a change in the conceptualization of the port. While in the past various kings aimed to plan the city and port together, after the unification of Italy the new government gradually decomposed into different authorities with overlapping roles, ambitions and competences. This intricate network of actors prevented the construction of a vision, giving rise to a modus operandi fragmented and inert which institutionalized and trapped the city into its past. Despite long debate and the existence of valid alternative designs for the construction of the new port, the national authorities opted for a new port next to the city reinforcing existing conflicts with the city itself.

The second port transformation has been conceptualized as ‘the port outside the city’. This includes two main critical junctures related to the construction of the oil port and the container port. The port outside the city is the celebration of the modern port due to the pressure of the Fascist Regime which aimed at making Naples Italy’s most important industrial and oil port. The port continued to expand eastward without really creating any integration with the city. The container revolution made the situation even worse. Containarisation filled the port with obsolete infrastructures and disconnected it from the hinterland. The history of Naples up to that moment was the history of a mercantile city. As the Tavola Strozzi shows, Naples was a city that owed its strength to its relationship with the sea rather than with the hinterland, and for morphological reasons of the city. The construction of the container terminal therefore ended up disintegrating the port-city relationship, making the port an insurmountable barrier within the city and isolated within its own port perimeter.

Deindustrialization processes could have been perceived as a potential change and an opportunity to rethink Naples’ relation with water. However, the municipality especially made city plans that did not include the port area as of interest to planning. This has reinforced the phenomena of path dependence.

Today new opportunities may arise from contemporary and future challenges. However, existing approaches to planning are unable to grasp the complexities in an holistic way. There is a renewed interest in imagining the future, but this must go through the experimentation of new imaginaries and provocative ideas capable of undermining the current mindsets of actors. The floating fiction study proposed by students, beyond its actual feasibility, is an interesting document which supports the thesis that path dependence can be broken through the introduction of alternative narratives. And it is precisely what this scenario aims to do. Climate change challenges are reinterpreted as opportunities to rethink the nature of the port so as to transform it from an industrial machine into a flexible body which is able to change over time through the redesigning of the coastline so as to lay the foundations for a re-appropriation of the sea by people. Coordination on a regional scale would be necessary to (re)conceptualize Naples as a multifunctional port cityscape where new economies, technologies and infrastructures are truly integrated with the spaces and the cultures of people living around the port.Footnote24

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Hilde Sennema and Penglin Zhu of TU Delft for the productive comments that greatly improved the manuscript. I would also like to show my gratitude to all the reviewers for their insights and feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Paolo De Martino

Paolo De Martino graduated in Architecture from the Department of Architecture of the University of Naples Federico II (DiARC). After graduating he worked as an architect in Naples, focusing mainly on the reuse of the existing architectural heritage and on urban regeneration. In 2014 he moved to Delft, the Netherlands, where he completed a PhD in a dual research programme between Delft University of Technology (TU Delft) and University of Naples Federico II. His research, entitled ‘Land in Limbo’, investigates port cities from a spatial and governance perspective, analysing the impact that actors have in shaping spatial development. The city of Naples is an emblematic case to question how to rethink the areas of land-sea interaction, at different scales, as opportunities for territorial regeneration. Since 2017 he has been teaching at the Department of Architecture of TU Delft where he is tutoring students in Design Studios such as ‘Architecture and Urbanism beyond oil’, ‘Adaptive Strategies’ and ‘Designing Public Spaces for Maritime Mindsets’, coordinated by Carola Hein. Since 2021, in collaboration with TU Delft, he has been involved in teaching two MOOCs entitled: (Re) Imagining Port Cities: (Re)Imagining Port Cities: Understanding Space, Society and Culture and Water Works: Activating Heritage for Sustainable Development. Paolo De Martino is a member of the PortCityFutures research group and a member of the coordination group. Since 2022 he is a Post doc at the University IUAV of Venice, under the supervision of Prof. Francesco Musco, working on the theme of Maritime Spatial Planning.

Notes

1 Hein, Port Cities; Kokot et al., Port Cities as Areas of Transition; Pinder and Hoyle, Cityport Industrialization and Regional Development.

2 Arthur, “Urban Systems and Historical Path-Dependence”; Djelic and Quack, “Overcoming Path Dependency,” 161–86; Garud and Karnoe, Path Dependence and Creation; Mahoney, “Path Dependence in Historical Research,” 507–48.; Pierson, “Increasing Returns, Path Dependence," 251–67.; Troy, “The Future of Cities,” 162–70.

3 Sorensen, “Institutions and Urban Space,” 21–38; “Taking Path Dependence Seriously,” 17–38.

4 North, “Institutions,” 97–112.

5 Sorensen, “Taking Path Dependence Seriously,”17–38.

6 De Martino, “Land in Limbo”.

7 Arthur, “Urban Systems and Historical Path-Dependence”; David, “Clio and the Economics of Qwerty,” 332–37; David, “Path Dependence – a Foundational Concep for Historical Social Science”.

8 Schreyogg and Sydow, The Hidden Dynamics of Path Dependence; Schreyogg, Sydow, and Koch, “Organizational Path Dependence,” 689–709; “Organizational Paths”.

9 De Martino, “Land in Limbo”; Hein and Schubert, “Resilience and Path Dependence,” 1–31; Sorensen, “Institutions and Urban Space,” 21–38; “Taking Path Dependence Seriously,” 17–38.

10 Braudel, Il Mediterraneo; Storia Misura Del Mondo.

11 Corboz, “The Land as Palimpsest,” 12–34; Braudel, Il Mediterraneo; Storia Misura Del Mondo.

12 Arrow, “Path Dependence and Competitive Equilibrium”.

13 Comune di Napoli. “Atti Del Consiglio Comunale.” (1896); “Atti Del Consiglio Comunale.” 1909.

14 Campania, ANIAI. Associazione Nazionale Ingegneri Architetti Italiani-Sezione. "Infrastrutture a Napoli – Progetti Dal 1860 Al 1898." edited by ANIAI. Napoli: Biblioteca Nazionale, 1978; Alisio, Izzo, and Amirante, Progetti Per Napoli; Cervati, D. “Sui Vantaggi Della Costruzione Del Porto Di Napoli Alla Riva Dei Granili.” 1862.

15 Pavia and Di Venosa, Waterfront.

16 Comune di Napoli. “Atti Del Consiglio Comunale.” 1911 (1).

17 Comune di Napoli “Bollettini Comune Di Napoli.” 1941; “Bollettini Comune Di Napoli.” 1931; “Bollettini Comune Di Napoli.” 1927.

18 Gabinetto di Prefettura di Napoli, “Opere Pubbliche, Ricostruzione a Napoli. Terzo Versamento, Fascio 1491, Fascicolo 001.” 1953-1955; “Petrolio-Varie. Terzo Versamento, Fascio 1650, Fascicolo 001.” 1953-1955; “Stabilimenti Petroliferi. Terzo Versamento, Fascio 1651, Fascicolo 001.” 1953-1955.

19 Ibid.

20 Gabinetto di Prefettura di Napoli, “Secondo Versamento, Fascio 1042, Fascicolo 078.” 1945.

21 Maglietta and Damiani, Il Porto Di Napoli; Porto di Napoli, “Bollettino Ufficiale Del Porto Di Napoli.” 1963.

22 Schreyogg, Sydow, and Koch, “Organizational Path Dependence,” 689–709.

23 GBN, “What If? The Art of Scenario Thinking for Non profits.” 2004; Sarpong and Maclean, “Scenario Thinking.” 1154–63.

24 Hein, “The Port Cityscape”; “Port Cityscapes”.

References

- Alisio, G., R. Izzo, and R. Amirante. Progetti Per Napoli. Ercolano: Guida editore, 1987.

- Arrow, K. J. “Path dependence and competitive equilibrium.” History matters: Essays on economic growth, technology, and demographic change (2004): 23–35.

- Arthur, W. Brian. Increasing returns and path dependence in the economy. University of michigan Press, 1994.

- Braudel, F. Storia Misura Del Mondo.: Storica Paperbacks, 1997. Historie, mesure du monde in Les Ambitions de l’Historie, by R.de Ayala e P. Braudel, Paris, Editions de Fallais, 1997.

- Braudel, F. Il Mediterraneo. Lo Spazio, La Storia, Gli Uomini, Le Tradizioni. Translated by Elena De Angeli. Bompiani, 2017. Milan: La Méditerranée.

- Campania, A. N. I. A. I. Associazione Nazionale Ingegneri Architetti Italiani-Sezione. “Infrastrutture a Napoli - Progetti Dal 1860 Al 1898.” edited by ANIAI. Napoli: Biblioteca Nazionale, 1978.

- Cervati, D. “Sui Vantaggi Della Costruzione Del Porto Di Napoli Alla Riva Dei Granili.” 1862.

- Corboz, A. “The Land as Palimpsest.” Diogenes 31, no. 121 (1983): 12–34.

- David, P. A. “Clio and the Economics of Qwerty.” The American Economic Review 75, no. 2 (1985): 332–337.

- David, P. A. “Path Dependence - a Foundational Concep for Historical Social Science.” Cliometria 1, no. 2 (2007): 91–114.

- De Martino, P. “Land in Limbo. Understanding Path Dependencies at the Intersection of the Port and City of Naples.” TU Delft Open, 2021.

- Djelic, M. L., and S. Quack. “Overcoming Path Dependency: Path Generation in Open Systems.” Theor Soc 36 (2007): 161–186. doi:10.1007/s11186-007-9026-0

- Garud, R., and P. Karnoe. Path Dependence and Creation. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2001.

- GBN. “What If? The Art of Scenario. Thinking for Nonprofits.” 2004.

- Hein, C. Port Cities: Dynamic Landscape and Global Networks. New York: Routledge, 2011.

- Hein, C. “Port Cityscapes: Conference and Research Contributions on Port Cities.” Planning Perspectives (2016). doi:10.1080/02665433.2015.1119714.

- Hein, C. “The Port Cityscape: Spatial and Institutional Approaches to Port City Relationships.” Portus Plus, the Online Magazine of Rete 8 (2019): 1–8.

- Hein, C., and D. Schubert. “Resilience and Path Dependence: A Comparative Study of the Port Cities of London,: Hamburg, and Philadelphia.” Journal of Urban History 47, no. 2 (2020): 1–31.

- Kokot, W., M. Gandelsman, K. Wildner, and A. Wonneberger. Port Cities as Areas of Transition. Ethnographic Perspectives. Wetzlar: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH., 2008.

- Maglietta, C., and C. Damiani. Il Porto Di Napoli. Note Preliminari Per Un Piano Di Studi. Roma: Centro Studi della Piro e C., 1960.

- Mahoney, James. “Path Dependence in Historical Research.” Theory and Society, 29 (2000): 507–548.

- Napoli, Comune di. “Atti Del Consiglio Comunale.” (1896).

- Napoli, Comune di. “Atti Del Consiglio Comunale.” 1909.

- Napoli, Comune di. “Atti Del Consiglio Comunale.” 1911 (1).

- Napoli, Comune di. “Bollettini Comune Di Napoli.” 1927.

- Napoli, Comune di. “Bollettini Comune Di Napoli.” 1931.

- Napoli, Comune di. “Bollettini Comune Di Napoli.” 1941.

- Napoli, Gabinetto di Prefettura di. “Secondo Versamento, Fascio 1042, Fascicolo 078.” 1945.

- Napoli, Gabinetto di Prefettura di. “Opere Pubbliche, Ricostruzione a Napoli. Terzo Versamento, Fascio 1491, Fascicolo 001.” 1953-1955.

- Napoli, Gabinetto di Prefettura di. “Petrolio-Varie. Terzo Versamento, Fascio 1650, Fascicolo 001.” 1953-1955.

- Napoli, Gabinetto di Prefettura di. “Stabilimenti Petroliferi. Terzo Versamento, Fascio 1651, Fascicolo 001.” 1953-1955.

- Napoli, Porto di. “Bollettino Ufficiale Del Porto Di Napoli.” 1963.

- North, D. C. “Institutions.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 5, no. 1 (1991): 97–112.

- Pavia, R., and M. Di Venosa. Waterfront. From Conflict to Integration. Trento: LISt Lab Laboratorio. Internazionale Editoriale, 2012.

- Pierson, Paul. “Increasing Returns, Path Dependence, and the Study of Politics.” American Political Science Review 94, no. 2 (2000): 251–267.

- Pinder, B. S., and D. A. Hoyle. Cityport Industrialization and Regional Development. London: Oxford, 1981.

- Ramos, Stephen J. “Resilience,: Path Dependence, and the Port: The Case of Savannah.” Journal of Urban History 47, no. 2 (2017): 1–22.

- Sarpong, David, and Mairi Maclean. “Scenario Thinking: A Practice-Based Approach for the Identification of Opportunities for Innovation.” Futures 43, no. 10 (2011): 1154–1163.

- Schreyogg, G., and J. Sydow. The Hidden Dynamics of Path Dependence, Institutions and Organizations. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- Schreyogg, G., J. Sydow, and J. Koch. “Organizational Paths: Path Dependency and Beyond.” In 21th Egos Colloquium. Berlin, Germany: Academy of Management Review. 34, no. 4 (2009): 689–709.

- Schreyogg, G., J. Sydow, and J. Koch. “Organizational Path Dependence: Opening the Black Box.” Academy of Management Review 34, no. 4 (2009): 689–709.

- Sorensen, A. “Taking Path Dependence Seriously: An Historical Institutionalist Research Agenda in Planning History.” Planning Perspective 30, no. 1 (2015): 17–38.

- Sorensen, A. “Institutions and Urban Space: Land, Infrastructure, and Governance in the Production of Urban Property.” Planning Theory & Practice 19, no. 1 (2018): 21–38.

- Troy, P. “The Future of Cities.” Australian Planner 36, no. 3 (1999): 162–170.