ABSTRACT

This article employs an Olympic urbanism perspective on the transformation of Beijing’s planning and development. For Beijing, holding the Olympic Games was not just about staging the city – and the nation – to the world as commonly understood. It was also about transforming the city through megaprojectification – the use of megaprojects like the Olympic Games to boost urban growth. The 2008 Summer Olympics played a critical role in growing Beijing in terms of the economy, population, fixed assets investment, infrastructure provision, and real estate development. Rapid but ill-planned growth within a decade exacerbated many pre-existing problems of the megacity. In the post-Olympic years, big city syndrome became Beijing’s calling card: pollution, congestion, unliveability, and unsustainability. Since then, a post-growth discourse has been emerging, reimagining the capital’s future in the context of balanced, coordinated development of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region. These include the construction of a new city Xiong’an to decentralize Beijing. This post-growth discourse that influenced the 2022 Winter Olympics was a contrast to the growth discourse that had underpinned the 2008 Summer Olympics. Beijing presents an unusual case of holding two Olympics within a short timeframe but under two contrasting urbanisms.

Introduction

A handful of cities have held the Olympic Games for more than once, but Beijing boasts of being ‘the world’s first dual Olympic city’: it held both the Summer and Winter Olympics in 2008 and 2022, respectively.Footnote1 It also held the Paralympics immediately after the Olympics in the same year; the organization and venues for the two distinct Games were highly integrated.Footnote2 It is unusual for one city to hold two Olympics only 14 years apart. It is more unusual that these two Olympics were held in two different urbanisms of the host city and, further, of the host nation. During this period, both Beijing and China have experienced rapid growth and then a drastic shift from growth to post-growth in urbanism, including urban thinking, urban imaginary, and urban practice of planning and development. Growth and post-growth, among other attributes, characterize China’s contemporary urban transformation; the two Olympics in Beijing sit squarely within the timeframe of this transformation.

The two decades that have spanned the two Olympics – including the bidding, planning, preparation, and operation of the events and pre- and post-event effects – have witnessed the largest scale of urbanization in human history as well as its most drastic transformation in China. In 2001, the year when Beijing won the bid for the 2008 Olympic Games, China’s urbanization rate was 37 per cent; in 2022, it was 64 per cent.Footnote3 But this urban transformation is more than quantitative; it is qualitative. China is becoming a highly urbanized society as well as a high-income country. Along with these socioeconomic transformations have been emerging a new discourse of ‘new-type urbanisation’ and ‘high-quality development’,Footnote4 a post-growth discourse that signifies a departure from the previous one of growth.

An urban China – its progress, challenges, and transformation – is the most symptomised and reflected in its capital city. During the period of holding the two Olympics, Beijing has experienced profound urban changes, to which the Olympics are contributory and integral. The contexts for understanding these urban changes are multi-scalar – local, regional, and national, involving Beijing’s own development, its positioning in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region, and the reorientation of national development under a new power regime. The two Olympics provide a unique perspective on a transformative Beijing in these contexts.

Megaprojectification

On the night of 14 July 2001, Beijing was announced as the host city of the 2008 Olympic Games. For the Chinese government and Chinese people, they anticipated this outcome and prepared for it – many signs had indicated that Beijing would win it this time. An official evening party was organized at the China Millennium Monument to the west of Tiananmen. Once the news was announced, China’s then president, Jiang Zemin, showed up at the evening and made a welcome speech to the world. Beijingers went to streets to celebrate until very late that night. People also flocked to Tiananmen Square to parade. After the Tiananmen Square movement – a students-led anti-corruption and pro-democracy movement that ended tragically with the killing of students and civilians by the army in June 1989, it was the first time that such a popular gathering was allowed there. Policemen were on alert, but they kept the order sensibly and calmly. The whole city was in an excitement that had been unprecedented and has been hardly paralleled after that night.

The year 2001 was special for China and was even more special for Beijing. After Beijing’s successful bid for the Olympics, later that year, China’s football team qualified for the FIFA World Cup for the first time and China was admitted into the World Trade Organization, both of which were longer and more arduous journeys than winning the Olympic bid. In the first year of a new millennium, both the city and the nation were in a state of aspiration, hope, and buoyancy. China was increasingly integrated with the world. In those years, both China and the world were profoundly different from today.

It was not the first time that Beijing bid for the Olympics. In 1992–1993, Beijing also bid for the 2000 Olympics but lost to Sydney in the end. The reasons for this failure were complicated, involving factors such as human rights (especially the backlash of the Tiananmen Square movement), environmental concerns, and political and ideological considerations. This failure was received in China with grave disappointment and bitterness, but it did not daunt the state’s determination to engage the world through such a megaevent.

In 1990, Beijing held the Asian Games, the first time that a Chinese city had held such a megaevent. During the process of planning and preparing for the Asian Games, policymakers and planners already had the idea that someday Beijing might hold the Olympics through building on the legacies of the Asian Games. It was Deng Xiaoping, China’s then paramount leader, who first expressed a desire to host the Olympics. On 3 July 1990, two months before the opening of the Asian Games, Deng visited the Asian Games village and was impressed by the newly constructed facilities. During this visit, Deng urged his aides in charge of sport to consider hosting the Olympics, ‘Have you made the decision to host the Olympics? Why dare you not do this? We have constructed these facilities. If we don’t host the Olympics, half of them will be a waste.’Footnote5 In February 1991, the State Council approved Beijing’s proposal to bid for the 2000 Olympic Games. So, Beijing’s formal pursuit for the Olympics did not start in 2001 but in 1991.

Holding the Olympics in Beijing, like holding similar megaevents elsewhere, is about staging the city – and the nation – to the world. While Beijing held the 2008 Olympics, Shanghai held the Expo 2010. These events are the urban icons orchestrated by the state to showcase not only the rise of these cities into world cities but also the rise of China.Footnote6 Staging a city or a nation through holding megaevents is not unique to the Chinese cities. But these events in Beijing and Shanghai have a strong resonance with ‘reform and opening-up’, a national development agenda that was masterminded by Deng Xiaoping and launched in 1978 to modernize China through reforming the old institutions and opening up to the world. This agenda has largely shaped China’s engagement with the world – through opening-up – since then, including the aspiration for megaevents like the Olympics. However, the staging effects of the Beijing Olympics – in terms of city branding, iconic architecture, spatial and non-spatial legacies, and the narrative of a rising China re-entering the world – have been read with mixed interpretations, pending contexts, perspectives, disciplines, and focuses.Footnote7

An alternative but related approach to the Beijing 2008 Olympics is megaprojectification – the use of a megaproject or megaevent to drive urban growth or transformation. An array of local development benefits for host cities and/or nations from staging global events are well appreciated.Footnote8 These benefits – some are visible and measurable, but some are intangible – are ‘highly desirable’ to the host city.Footnote9 This explains why those global events have been vehemently pursued by cities (and nations) across the globe. Francesc Muñoz argues that ‘the urbanisation of the Western world during the 20th century cannot be understood fully without consideration of the contribution of major urban events’ like the Olympics.Footnote10 This argument can also be comfortably applied to understanding the Olympic effect on Beijing. At the turn of the century, Beijing needed such a megaproject to drive its urban development; China needed such a megaevent to engage the world.

Faster, higher, stronger

The precinct for the Olympic Games was designated in north Beijing. It neighbours the 1990 Asian Games village and sits on the north–south axial line that runs through the whole city (see ). This north–south axial line is both physical and virtual. Penetrating through the centre of the Forbidden City, the traditional and spatial centre of Beijing, this axial line has historical, cultural, and political importance in defining the city’s planning and its spatial evolution.Footnote11 It has governed the reality and imagining of Beijing’s urban structure since probably the city’s genesis. The Olympic precinct is called Olympic Green, responding to the slogan of ‘Green Olympics, High-tech Olympics, and People’s Olympics’ for the 2008 Games. It has an area of 1505.9 hectares.Footnote12 In early 2002, an international competition for conceptual planning and design for the precinct was held. The scheme proposed by Sasaki Associates, a Boston-headquartered design firm, won the first prize for the scheme’s expression of the green concept, its dialogue with the city’s history and urban structure, and a cultural appreciation of orientalism.Footnote13 This wining scheme forged the base for the precinct’s planning, design, and development (see ).

Figure 1. Model of the Olympic Precinct in Beijing. Source: The author.

Note: This photo shows the location of the Olympic precinct in Beijing in a reversed north–south orientation. It shows an explicit north-south axial line that links the Olympic precinct with the city’s structure. This photo, taken in September 2016, is part of the city’s model displayed in the Beijing Planning Hall.

Before the designation of the Olympic precinct in north Beijing, there were proposals of having it in south Beijing.Footnote14 The rationale was to use the Olympic megaproject to drive the growth of south Beijing, which has been less developed than north Beijing in history and at present. This proposal was not accepted. The current site was endorsed because its surrounds had been well developed, including the legacy infrastructure and facilities of the 1990 Asian Games. In 1983, when Beijing started to bid for the Asian Games, the precinct was largely undeveloped. It was chosen as the site of the Asian Games for its availability of a vast tract of land, access to arterial roads, and proximity to the Beijing Capital International Airport.Footnote15 The Asian Games had transformed it into an urban precinct with quality and morphology that were superior to elsewhere in Beijing then. It was the first exemplary case of megaprojectification of urban development in a Chinese city. The precinct has been formally called Asian Games Village since its construction in the late 1980s.

During the process of bidding for the 2008 Olympic Games, another major consideration for proposing the site in north Beijing was to build up confidence in the city’s capacity of holding the event by presenting the best developed precinct of the city.Footnote16 Beijing lost the bid for the 2000 Olympics; the state did not want to lose it again. These considerations had their justifications more than two decades ago. In retrospect, not having the Olympic precinct in south Beijing had lost a rare opportunity of megaprojectification to rebalance intracity development. As it turned out, the Olympic Games, among other factors, had exacerbated the north–south imbalance in the city’s development. The north–south divide in socioeconomic development had been enlarged during the Olympic years. In 2001, GDP per capital in north Beijing was 2.22 times that in south Beijing; in 2010, the difference increased to 2.51 times.Footnote17

Audiences at home and overseas must be impressed by the extravagance of the 2008 Olympic Games. Here are two observations made by international experts: being ‘the most lavish in Olympic history’, it presented a memorable spectacle and supported the Olympic core values;Footnote18 it created a Beijing model of Olympics for its scale, majesty, and effective and efficient organization.Footnote19 During the Olympic season, many Chinese netizens criticized the way taxpayers’ money had been spent largely for the state’s vanity. According to an audit report produced by the National Audit Office in June 2009, for the 2008 Olympic Games, a total of 102 venues were built or renewed, including 36 venues for holding the games and 66 for training, which amounted to a total investment of RMB 19.49 billion.Footnote20 These venues are mostly located in Beijing; a small number of them are in other cities like Tianjin, Shanghai, Shenyang, Qinhuangdao, and Qingdao. As far as the operation of the event is concerned, the 2008 Olympics made a profit of over RMB 1 billion (total revenues of RMB 20.5 billion and total expenditures of RMB 19.343 billion); the Paralympics made the ends meet (both total revenues and total expenditures equalled at RMB 863 million).Footnote21 For many Chinese citizens, it was surprising that the 2008 Olympics managed to make a marginal profit. The official audit report did not disclose any further financial details but generic aggregates. An international study indicates that the costs of organizing the Olympics in 2000–2012 are usually covered by revenues, but the core Olympic capital investments show cost overruns;Footnote22 the study also indicates the unavailability of data about capital investments for the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games.Footnote23

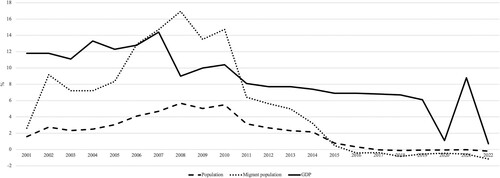

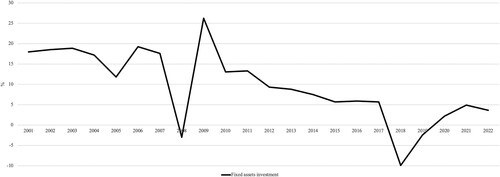

In the period of the decade-long Olympic effect (the years before and after the Olympics from 2001 to 2010), Beijing experienced massive growth, seeming to echo the Olympic motto ‘faster, higher, stronger’. present major aspects of the city’s growth in the pre- and post-Olympic years. In 2001–2010, Beijing increased its population by 41.6 per cent, migrant population by 168.2 per cent, population density by 45.1 per cent, GDP by 287.5 per cent, and metro length by 522.2 per cent.Footnote24 In this decade, Beijing maintained two-digit average annual growth rates of major indicators for urban development (see ).

Figure 2. Growth Rates of Population, Migrant Population, and GDP in Beijing, 2001–2022. Data source: Beijing Bureau of Statistics, 2023, Beijing 2023 Statistical Yearbook, created by the author.

Figure 3. Growth Rates of Fixed Assets Investment in Beijing, 2001–2022. Data source: Beijing Bureau of Statistics, 2023, Beijing 2023 Statistical Yearbook, created by the author.

Note: In the Olympic year of 2008, Beijing had a negative growth rate of fixed assets investment. This was because the government restricted major constructions in this year to minimize their negative impacts on the urban environment like air pollution to prepare for the event.

Table 1. Average Annual Growth Rates of Major Indicators for Beijing’s Development, 2001–2022

The Olympic decade witnessed the fastest growth in Beijing’s history; the scale and speed of this growth have been hardly paralleled by any other city at home or overseas. The 2008 Olympics significantly boosted the city’s growth that had already been in momentum. One study of Summer Olympic cities from Athens (1896) to Sydney (2000) indicates that the host cities do not experience a measurable increase in population size relative to non-host cities and, further, these host cities experience a relative decline in city size after the Games.Footnote25 If this finding is valid – the study does not investigate why this happens and suggests it as future research, Beijing, which is not included as a case in the study, seems to be an outlier among the Olympic cities in terms of urban growth.

The Olympics also emboldened the city’s vision and pro-growth ambition. In 2002, one year after the successful bid for the 2008 Olympics, the Beijing government decided to make a new master plan for the city’s strategic development, which led to the fruition of the Beijing Municipal Master Plan (2004–2020). A master plan is the most important in the Chinese planning system and is of both strategic and statutory status.Footnote26 This master plan, among other goals, explicitly set the strategic goal for Beijing to become a world city: ‘establish on the goal of building a world city, and continuously enhance Beijing’s status and role in the world city system’.Footnote27 In those years, concepts like the ‘world city’ or ‘global city’ proposed by authors such as Peter Hall, John Friedmann, and Saskia Sassen were very popular and appealing when internationalization and globalization were the buzzwords in China’s urban discourse, policymaking, and city branding.Footnote28

In 2009, one year after the Olympic Games, the Beijing government formally announced its initiative of building Beijing into a ‘world city’, mapping the city’s path in the coming decades towards the vision. This initiative immediately generated a ‘world city’ fanfare in public debates, media reportage, professional interest, and academic research. At that time, few commentators would predict that this growth-oriented ethos for ‘worlding’ the city would end abruptly only several years later.

More polluted, more congested, more unliveable

Many cities in the world suffer the so-called big city syndrome – the unhealthy, unliveable, and unsustainable symptoms of living and working in a big city that is often ill-planned and poorly managed. Among the Chinese cities, Beijing is the primary city that should wear the hat of big city syndrome in general perception. In the Olympic decade, the city’s growth was beyond the boldest projection in planning. The Beijing Municipal Master Plan (2004–2020) stipulated that the city’s population would be controlled at around 18 million by 2020.Footnote29 In reality, Beijing’s population reached 20 million in around 2010.Footnote30 This is the challenge in the planning of Chinese megacities like Beijing: the most radical projection in strategic planning might prove to be conservative in actual urban development. Consequently, there was a dilemma between planning-led development and development-led planning when these cities were experiencing rapid growth. This dilemma was the most acute in Beijing in those years leading up to the 2008 Olympics. Many developments were so fast and massive that they were not well planned before development, creating new problems and exacerbating old problems that were associated with the city’s ever-growing size.

Since the late twentieth century, pollution, congestion, and high cost but low quality of living had been the hallmarks of Beijing despite many enviable opportunities that the capital could offer. But the big city syndrome did not become the city’s calling card until the years around 2010 when the symptoms seemed to reach a peak level. Beijing was becoming ‘more polluted, more congested, more unliveable’ along with its growth that was ‘faster, higher, stronger’. Statistically, Beijing’s GDP growth, population growth, vehicle growth, and energy consumption growth were generally concurrent and correlated in recent decades.Footnote31 But there was a clear Olympic effect in the growth patterns of these indicators. Nationally, in those years around 2010, there were also wide-spread concerns, debates, and complaints about pollution and environmental degradation, the side effects of the nation’s rapid growth mainly in an economic sense. There were also critical reflections on the growth-oriented development model that the nation had followed during the several decades of ‘reform and opening-up’ since 1978.

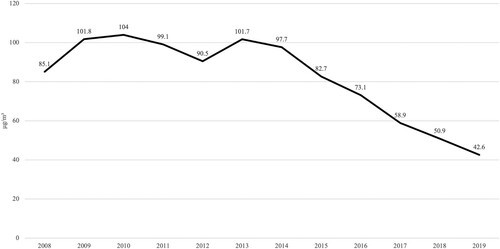

While many Chinese cities were more polluted and confronted more serious urban challenges, Beijing’s big city syndrome had attracted the most attention and concerns. Compared to other indicators of pollution, air quality is the most obvious and it turned out to be the worst in the several post-Olympic years in Beijing (see ). Air pollution presented probably the most challenging issue for the preparation of the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Compared with infrastructure construction and event organization, air was harder to plan and manage. But the government had a will to ‘command’ the air: it ordered the polluters – factories, construction sites, and vehicles – to pause in Beijing and its surrounds before and during the Olympic season. This explained why Beijing’s air quality was comparatively better in 2008 than the subsequent years (see ); this also explained why Beijing experienced a negative growth rate in fixed assets investment, including infrastructure and real estate investments, in that year (see ). However, it was assumed that those polluters that were paused for the event would emit more after the event to compensate for their economic loss. This assumption was not unjustified or unevidenced. In the several post-Olympics years, Beijing’s air quality became much worse (see ).

Figure 4. The Yearly Average PM2.5 Concentration in Beijing, 2008–2019. Data source: IQAir, 2019, Beijing Air Quality Report, created by the author.

As presented earlier, the 2008 Olympics was a boost to Beijing’s infrastructure investment and provision. In 2001, Beijing had only two metro lines; in 2008, it had eight. Beijing’s metro construction has continued in the post-Olympic years. As of 2022, Beijing had 27 metro lines with a total length of 797.3 km.Footnote32 However, the growth in infrastructure investment and provision did not help improve the city’s transport as wished. The problem was that the city’s urban development and urban infrastructure had moved ahead fast but concurrently. There was a clear lack of coordination between them, and the new infrastructure system and the old one were not well articulated. Users of them could spontaneously feel that they were planned and constructed in a sort of ‘rush’. The city has not been short of complaints about the inconvenience of its public transit system despite increasing provision of it. Growth does not always create desired urban environment. The speed and scale of Beijing’s growth have challenged its capacity and capability of urban planning and management.

Beijing seemed to be marching on a growth odyssey: its size was bigger and bigger; its urban form was denser and denser; its metro system was longer and longer; its traffic was busier and busier; and its sky was grayer and grayer. The city government had made policy and non-policy interventions. These included the restriction of private car ownership and use through setting strict quota on issuing new plates and allocating the running of cars according to plate numbers. These interventions had mitigated the traffic and pollution problems to a limited degree but added to the inconvenience of urban living. Piecemeal approaches did not seem to solve the big city syndrome. The capital required some fundamental reimaging of its future.

Reimagining the capital in the region

Concerns and debates about Beijing’s population growth and associated urban densification and expansion have been intensifying since the late 1990s before the Olympic decade. Many ideas were considered in the context of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region to seek balanced, coordinated development of it instead of the existing Beijing-dominated regional structure. One radical thought was even to relocate the capital elsewhere considering the city’s urban pressures and problems and its constraints of land and water resources. The city’s growth juggernaut seemed unstoppable. At the turn of the second decade of the twenty-first century, it became a consensus that Beijing’s growth had reached a bottleneck. Beijing’s air pollution and all-day traffic jams were not only complained and derided by residents but also often became headlines in local and international media. Beijing, despite being an important and dynamic city in the national and international urban systems, was becoming a textbook case of unliveability and unsustainability. To change the city’s trajectory required bold vision and strong political will. After coming into power in late 2012, Xi Jinping decided to make a difference in addressing its big city syndrome in the context of advancing coordinated development of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region.

The Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region is among the trio of China’s mega city regions; the other two are the Pearl River delta region (or Greater Bay Area) and the Yangtze River delta region. In many aspects of regional development, like economic prowess, global competitiveness, and marketization of economic sectors, the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region is lagging behind its southern counterparts. Its regional development issues, especially in terms of intraregional imbalances, are the most acute and complicated among the trio. While Beijing has been overdeveloped into a megacity with many urban problems, the other cities in the region have been disadvantaged in accessing opportunities and reaching their development potentials. Tianjin, despite its proximity to Beijing and status of provincial-level municipality,Footnote33 has been struggling in transforming from an industrial to post-industrial city. In the Chinese urban system, Tianjin has been eased out of the top ten list of GDP by those southern cities like Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Suzhou, and Hangzhou that are not provincial-level municipalities.Footnote34

Hebei province has some geospatial blessings, but these do not seem to have translated into its socioeconomic development benefits. It is a coastal province for its modest coastline along the inlet Bohai Bay, countering the general misperception that it is an inland province. Within its territory, it contains Beijing and Tianjin, both provincial-level municipalities. However, the province does not seem to have benefited from its coastal access and proximity to the two megacities, while several southern provinces, like Guangdong and Jiangsu, have clearly capitalized on similar geospatial assets. For long, Hebei has been perceived as the province that has sacrificed for the national capital’s development in terms of provision of water and environmental resources and loss of socioeconomic development opportunities. Further, some Hebei counties bordering Beijing and Tianjin have been poverty-ridden, forging a ‘poverty belt’ surrounding them.Footnote35

The intraregional imbalances are epitomized as the overconcentration of growth and resources in Beijing in contrast with – and at the cost of – its neighbouring cities. The reasons are complicated and have historical roots. The emergence of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region is more an outcome of political factors than market forces. The regional economy has a higher share of state-owned enterprises – implying a lower marketization level – than the national average.Footnote36 Those southern provinces that have benefited from the agglomeration economies of megaregions are also known for their high marketization levels and dynamic private sectors in the provincial economies. Market forces enable and lubricate regional collaboration and spill-overs. On the contrary, in some places of the ‘poverty belt’ in Hebei, local economic development is restricted out of administrative and military controls there for their proximity to the national capital in addition to their unfavourable geographical and climatic settings. While Beijing is growing bigger and bigger, its divide with other cities in the region is becoming wider and wider, exacerbating intraregional imbalances.

In the recent decade, the central government has endorsed the strongest intervention into the planning of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region, largely driven by Xi Jinping’s advocacy and political will. The major tenet is to alleviate Beijing of its non-capital functions and relocate them elsewhere in the region. This has dual aims of reducing Beijing’s size and density and achieving balanced, coordinated regional development.

In 2013–2017, Xi Jinping visited sites in the region and gave a series of directives on coordinated development of it. In February 2014, the region's coordinated development was elevated into a national strategy. In June 2014, the central government established the Leadership Group for Coordinated Development of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region headed by the deputy premier in office to oversee the regional planning and development. This is an exceptional high-profile leadership arrangement endorsed presumably by Xi Jinping. In June 2015, the Chinese government released the Outline Plan for Coordinated Development of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region to provide guidance for strategic development of the region.Footnote37 This top-down planning approach has followed so-called top-level design, a notion promoted by Xi Jinping who claimed a ‘new era’ to mark his rule since late 2012.

On 26 February 2014, when Xi Jinping inspected Beijing and convened a meeting to discuss the development of the city and the region, he gave instructions to: ‘maintain and strengthen the core functions of the capital, adjust and reduce the functions that are incompatible with the capital, and relocate some [non-capital] functions to Hebei province and Tianjin’.Footnote38 Xi Jinping’s vision and will reoriented the strategy of Beijing, which was materialized in the latest Beijing Municipal Master Plan (2016–2035). This master plan repositioned and stressed Beijing as the national political centre, a cultural centre, an international communication centre, and a sci-tech innovation centre – a so-called four-centre vision.Footnote39 This vision marks a strategic shift in imagining Beijing’s future. To illustrate the shift: as discussed earlier, the previous 2004 master plan set one strategic goal of building Beijing into a ‘world city’ and enhancing the city’s ‘status and role in the world city system’. This ‘world city’ goal was removed from the latest plan. In reimaging the city, a ‘global Beijing’ is being replaced by a ‘capital Beijing’.

Decentralizing Beijing

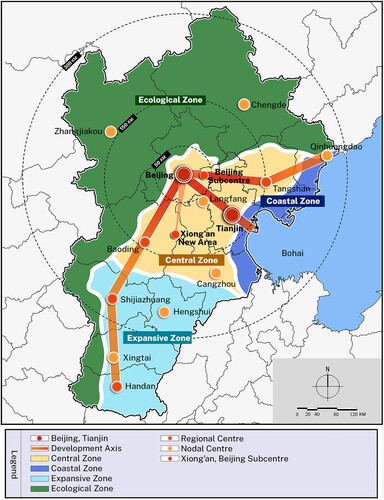

In the Beijing Municipal Master Plan (2016–2035), alleviating the city’s non-capital functions became a keynote of its future development. The plan set a spatial structure of ‘one core, two wings’ – one core of central Beijing and two wings of Beijing subcentre and Xiong’an – for the city in the region (see ). The ‘two wings’ were set to alleviate the urban pressures and crowding in the ‘one core’.

Figure 5. Beijing in the Region. Source: Beijing Government, 2017, Beijing Municipal Master Plan (2016–2035), recreated by the author.

The ‘two wings’ involve the building of two new cities to relocate Beijing’s non-capital functions there. One is the Beijing subcentre. The idea of building a subcentre for Beijing to alleviate the overcrowding in the central city area had been on and off for some years. In 2015–2016, the idea was formalized and endorsed by the central government as part of the national strategy for coordinated development of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region. The Beijing subcentre was designated in Tongzhou district to the east of central Beijing. Tongzhou is an existing urban centre in metropolitan Beijing. Building it into the Beijing subcentre did not have to start from scratch in terms of urban development, but the initiative has significantly enhanced the district’s importance in metropolitan Beijing and the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region.

With a planned area of 155 km2,Footnote40 the Beijing subcentre is a new civic centre for holding the Beijing municipal government and its agencies and associated resources, which are going to be relocated there from central Beijing. With this relocation, central Beijing is dedicated to exclusively accommodating the central government agencies and functions, fulfilling the city’s role as the national capital. In January 2019, the Beijing municipal government formally moved into the Beijing subcentre. Both the construction of the civic centre and the movement of other municipal agencies are still going on.

The relocation of the Beijing municipal government out of central Beijing and the reconstruction of a civic centre are a bold endeavour. An even bolder endeavour is to build a new city from scratch in a vast rural land in the region. This is the Xiong’an New Area, which was announced on 1 April 2017. Xiong’an sits in Hebei province, 100 km to the south of Beijing. According to Xu Kuangdi, Shanghai’s ex-mayor and the lead advisor for selecting the site, the location of Xiong’an has a spatial continuation from Beijing’s urban structure of north–south orientation,Footnote41 which is also reflected in the selection of the Olympic precinct as stated earlier. In the reginal context, Xiong’an is in the geometrical centre of several major cities, but the site itself is in the middle of nowhere (see ). So far, both strategic and detailed plans for Xiong’an have been completed. In the long run, Xiong’an will become a city with a construction land area of 530 km² for a population of around five million.Footnote42 As of December 2023, Xiong’an was in the early stage of infrastructure construction and urban development (see ).

Figure 6. Xiong’an under Construction. Source: The author.

Note: Photo 1 is the state-invested business service centre that is already completed. Photo 2 shows the site delineated for a campus of the University of Science and Technology Beijing to be planned and constructed. Photo 3 shows the headquarters of two state-owned enterprises under construction. Photo 4 is a construction site fenced in a farmland. All photos were taken in December 2023, showing the latest construction state of various sites in Xiong’an.

Xiong’an has triggered romantic imaginings about China’s ‘new-type urbanisation’, like green, smart, sustainable, human-centric, and liveable – the notions exactly opposite to Beijing’s big city syndrome. But it has also raised criticism and doubt, arousing justified observations about the ‘Xiong’an paradox’ between imaginary and reality.Footnote43 Indeed, Xiong’an is Xi Jinping’s city-making project. Official reportage stressed that Xi proposed the idea and made the decision. The imagining of building such a new city in the middle of nowhere is more of political will than pragmatic reasoning. It is a state project and does not seem to have engaged market forces. Since its announcement in 2017, no sign has shown that it would grow organically and naturally by itself if it were not for the state machine driving its planning, investment, and construction. The idea of building such a big city largely through government intervention and investment is more than bold; it is utopian. Utopianism is not a rarity in Chinese urban imaginary. The critical prism to the future of Xiong’an is the government–market relationality – how a government-backed initiative will sustain a new city’s growth, which will have to be tested by the market in the long run.

Geospatially, Beijing’s dominance in the region counters the natural evolutions of many megaregions that are coastal. Tianjin is better positioned than Beijing to become a great city for the former’s access to coast and port. However, the emergence of this region has not been natural but political. Beijing’s status as the national capital has put all the other cities in the region under its shadow. The current regional planning approach aims to counter the centripetal forces of Beijing to rebalance regional development – a centrifugal process. Both centripetal and centrifugal forces are at play in negotiating a coordinated development of the region. The state intervention has made Beijing’s dominance in the region. Now the state intervention is trying to mitigate its dominance.

‘Reduction-based development’, literally an oxymoron, was coined to describe Beijing’s new development thinking of and approach to reducing its population and relocating certain urban functions elsewhere in the region. The strategy for decentralizing and downsizing Beijing seems to be taking some effect. Beijing has decreased both population and migration population, albeit at modest rates, from the mid-2010s (see ). The post-growth Beijing is measured not only by its reduced population but also by its lower growth rates in GDP and fixed assets investment (including infrastructure, real estate, and transport) – several indicators had negative growth rates in certain years – than the growth-dominated Olympic decade (see ). In 2011–2022, the average annual growth rates of major indicators for Beijing’s development were significantly lower than those in the previous Olympic decade of 2001–2010 (see ).

Meanwhile, Beijing’s air quality has markedly improved (see ). As of 2020, Beijing’s air quality was classified as ‘moderate’ – an acceptable level – according to the criteria of the World Health Organization.Footnote44 There is still much room for Beijing to improve its air quality and further liveability and sustainability, but its progress in the recent decade suggests remarkable improvement from the peak years of air pollution around 2010.

In a report on the work of the Beijing government in 2017–2022 delivered in January 2023, Yin Yong, the mayor of Beijing, made the following statement on the reorientation of Beijing’s urban strategy and its reduction-based development:

We have kept to the strategic positioning of Beijing as the national capital, and embraced historic changes in the city’s development … We have attained the goals of [reduction-based development] set out for the first phase implementation of the [Beijing Municipal Master Plan (2016–2035)]. We have met the target of a 15 per cent reduction of permanent residents in Beijing’s six urban districts [in central Beijing] compared with 2014. The supply of land for urban and rural construction has been cut by 120 km². The 132 km² of land strategically vacated and reserved for future development has been placed under rigorous management. Thanks to these efforts, Beijing now boasts [of] a more balanced spatial layout that better harmonises the needs for people’s work and daily life with the requirement to protect the environment.Footnote45

A Summer–Winter contrast

Beijing won the bid for the 2022 Winter Olympics on 31 July 2015. It did not cause as much a sensation as the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing or in China, nor did it generate as much an Olympic effect on the city’s development. This is understandable since the Winter Olympics is not comparable with – and indeed is different from – the Summer Olympics in terms of scale, influence, and requirements for venues and infrastructure.

During the Winter Olympic period from 2015 to 2022, China was in a different discourse of urban planning and development from the period of the 2008 Summer Olympics. In 2015, the same year as when Beijing was awarded the Winter Olympics, the Chinese government rephrased a ‘people-centric’ development philosophy featured by concepts like ‘innovation’, ‘coordination’, ‘green’, ‘openness’, and ‘sharing’.Footnote46 None of these concepts is new. But, put together, they were meant to mark Xi Jinping’s ‘new era’ and its focus on ‘high-quality development’ to differentiate itself from the previous growth-dominated development philosophy. One year earlier, the Chinese government released the National New-Type Urbanization Plan (2014–2020), the first national urban plan of its kind to advance a new urban thinking that prioritizes qualitative upgrading over quantitative growth in urbanization.

The new urban imaginary for Beijing and the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region influenced the way the 2022 Winter Olympics had been prepared and organized. It did not incur massive urban construction of infrastructure or venues, but largely reused the old ones – the legacies of major venues of the 2008 Summer Olympics. The Winter Olympics was held under very strict control of COVID-19, impacting many aspects of the event’s local engagement and global outreach. Its operation did not seem as extravagant as the 2008 Olympics but followed the principle of holding a ‘simple, safe, and excellent’ Olympic event set by the government. According to a financial statement issued by the organizing committee in May 2023, the Winter Olympics had total revenues of RMB 15.39 billion and total expenditures of RMB 15.04 billion, generating a marginal profit of RMB 350 million.Footnote47 Like the financial report for the 2008 Olympic Games, this statement provided aggregates only and lacked details.

The venues for the Winter Olympics are in central Beijing, Yanqing – a mountainous peri-urban district of Beijing, and Zhangjiakou, a city in Hebei that neighbours Beijing. There were considerations for regional development in this allocation of venues. Those mountainous areas in Yanqing and Zhangjiakou have the geographical conditions for the winter sports. Another consideration was to use this event to drive local infrastructure provision and socioeconomic development in Zhangjiakou, which, despite being close to Beijing, had not benefited much from the capital’s spill-overs. In late 2019, a high-speed rail connecting Beijing and Zhangjiakou was put in use both to prepare for the Winter Olympics and to advance coordinated development of the region. Chongli, a district of Zhangjiakou city, used to be known as a ‘poverty county’ in the ‘poverty belt’ in Hebei province, has now been transformed into a hotspot ski resort, thanks to being a venue of the 2022 Winter Olympics and the high-speed rail that links it to Beijing. The Olympic effect on Chongli tells a story of transformation ‘from poverty to prosperity’ in the regional context.Footnote48

Within central Beijing, there was only one venue for the Winter Olympics, which was used for freestyle and big-air snowboarding events. This venue seems to establish a connection between the Summer and Winter Olympics, substantially and symbolically. The venue sits in the site of an industrial legacy – the Capital Steel Group, a mega steel mill and a Fortune 500 giant. The steel mill had been in Beijing for nearly a century, but it was removed out of the city to Caofeidian, a coastal district of Tangshan in Hebei province (see ), to prepare for the 2008 Summer Olympics out of concerns of its pollution.Footnote49 Its industrial legacy is being transformed into a post-industrial business park for creative and cultural activities. These include one venue for the 2022 Winter Olympics. This venue will remain permanently, aiming to boost the site’s transformation and branding (see ). Now, the site is a place of multiple contrasts – between industrial and post-industrial, between old and new, between growth and post-growth, and between the Summer and Winter Olympics – that are playing out in Beijing.

Conclusion

Beijing’s rapid, drastic transformation in urban imaginary and urban development is a microcosm for understanding the transformation of China’s urbanization in the twenty-first century. The shift from growth to post-growth, in both discourse and practice, applies to China’s urban development and broader national development. But this shift is the most noted in Beijing for the city’s importance in the national and global urban systems as well as for the prominence of the shift itself. Olympic urbanism provides an unusual and accidental perspective on the transformation of the city and, further, of the nation’s urbanization. Beijing is the only city that has held two Olympics within such a short timeframe. And the period of the two Olympics happens to span across the city’s transformation between two contrasting urbanisms. A revelation of this experience sheds light on a transformative city and a rapidly urbanizing nation, and enriches our understanding of Olympic urbanism in the host city’s local and national contexts.

The transformation of Beijing as a dual Olympic city is recent, short, and intense. The transformation has been driven by an effort to seek the city’s identity in relation to its role as the national capital. Peter Hall classifies seven types of the capital city, including multi-function capitals, global capitals, and political capitals.Footnote50 Beijing has functioned as a multi-function capital, like London, Paris, and Tokyo and has also aspired for becoming a global capital like them. The 2008 Summer Olympics fit into this global imaginary underpinned by a growth ethos. The city’s strategic reorientation in the recent decade prioritized its role as a political capital over other national or global functions like an economic centre in the world city system. This shift has involved a local imaginary of decentralizing and downsizing the city and a regional imaginary of balancing the development of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region. The 2022 Winter Olympics sit within these local and regional imaginaries underpinned by a post-growth ethos. Beijing’s transformation as viewed through the two Olympics is not only historical but also contemporary and futuristic. Much of the reimagining of the capital and its materialization is too early to be judged but awaits the test of time.

Acknowledgements

Two reviewers provided useful comments to improve the article. Edward Hu reviewed it and suggested good comments and edits. The author is responsible for any errors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Richard Hu

Richard Hu is an award-winning urban planner. His recent books include Megaregional China (2024, Routledge) and Reinventing the Chinese City (2023, Columbia University Press).

Notes

1 Meng and Neto, “Beijing”.

2 In this article, discussions about the Olympics in Beijing also include the Paralympics unless they are specifically differentiated.

3 The World Bank, Urban Population.

4 Chinese Government, National New-Type Urbanization Plan.

5 The Paper, From Asian Games to Summer and Winter Olympic Games.

6 Hu and Chen, Global Shanghai Remade, 224.

7 See: Broudehoux, “Images of Power”; Ren, “Olympic Beijing”; Ren, “Aspirational Urbanism”; Schneider, Staging China; Zhang and Zhao, “City Branding and the Olympic Effect.”

8 Clark, Local Development Benefits from Staging Global Events, 15–18.

9 Gold and Gold, “Introduction,” 9.

10 Muñoz, “Olympic Urbanism and Olympic Villages,” 175.

11 Yu, “Redefining the Axis of Beijing.”

12 Beijing Municipal City Planning Commission, 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, 8.

13 Ibid., 36–55.

14 Jia, “Axial Line.”

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Huxiu, Why is South Beijing So Inferior?

18 Gold and Gold, “Introduction,” 2.

19 Cook and Miles, “Beijing 2008,” 359.

20 National Audit Office, Audit Report.

21 Ibid.

22 Preuß, Andreff and Weitzmann, Cost and Revenue Overruns of the Olympic Games, x.

23 Ibid., 80.

24 Beijing Bureau of Statistics, Beijing 2023 Statistical Yearbook, calculated by the author.

25 Nitsch and Wendland, “The IOC’s Midas Touch.”

26 Hu, Reinventing the Chinese City, 204.

27 Beijing Government, Beijing Municipal Master Plan (2004–2020).

28 See works by these authors: Friedmann, “The World City Hypothesis”; Hall, The World Cities; Sassen, The Global City.

29 Beijing Government, Beijing Municipal Master Plan (2004–2020).

30 Beijing Bureau of Statistics, Beijing 2023 Statistical Yearbook.

31 United Nations Environment Programme, A Review of 20 Years’ Air Pollution Control in Beijing, 18.

32 Beijing Bureau of Statistics, Beijing 2023 Statistical Yearbook.

33 Within China’s administrative system, there are four such provincial-level municipalities: Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, and Chongqing.

34 China Daily, “Top 10 Chinese cities by GDP.”

35 South China Morning Post, “Beijing's ‘Poverty Belt’ Raises Alarm.”

36 Song, “Retrospect and Prospect,” 4.

37 Chinese Government, Outline Plan for Coordinated Development of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region.

38 Xinhua News Agency, Millennium Plan, National Initiative.

39 Beijing Government, Beijing Municipal Master Plan (2016–2035).

40 Ibid.

41 The Paper, “Xu Kuangdi on the Planning of Xiong’an New Area.”

42 Hebei Government, Outline Plan for the Hebei Xiong’an New Area.

43 Hu, The Shenzhen Phenomenon, 151–153.

44 IQAir, Air quality in Beijing.

45 Yong, Report on the Work of the Government.

46 Kuhn, “The Five Major Development Concepts.”

47 Beijing Government, Financial Report by the Organising Committee for the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games.

48 Wright, “From Poverty to Prosperity.”

49 Hu, Reinventing the Chinese City, 49–51.

50 Hall, “Seven Types of Capital City,” 8–9.

Bibliography

- Beijing Bureau of Statistics. 北京2023 统计年鉴 [Beijing 2023 Statistical Yearbook]. 2023. Accessed January 16, 2024. https://nj.tjj.beijing.gov.cn/nj/main/2023-tjnj/zk/indexch.htm.

- Beijing Government. 北京城市总体规划 (2004–2020年) [Beijing Municipal Master Plan (2004–2020)]. 2004. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://zh.m.wikisource.org/zh-hans/北京城市总体规划(2004年–2020年).

- Beijing Government. 北京城市总体规划(2016– 2035年) [Beijing Municipal Master Plan (2016–2035)]. 2017. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://www.beijing.gov.cn/gongkai/guihua/wngh/cqgh/201907/t20190701_100008.html.

- Beijing Government. 北京冬奥组委财务收支报告 [Financial Report by the Organising Committee for the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games]. 2023. Accessed January 23, 2024. https://www.beijing.gov.cn/ywdt/yaowen/202305/t20230506_3088472.html.

- Beijing Municipal City Planning Commission. 2008 Beijing Olympic Games: International Competition for Conceptual Planning and Design of Beijing Olympic Green & Wukesong Cultural and Sports Center. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press, 2003.

- Broudehoux, Anne-Marie. “Images of Power: Architectures of the Integrated Spectacle at the Beijing Olympics.” Journal of Architectural Education 63, no. 2 (2010): 52–62.

- China Daily. “Top 10 Chinese cities by GDP.” February 8, 2023. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://govt.chinadaily.com.cn/s/202302/08/WS63e30f7d498ea274927af396/top-10-chinese-cities-by-gdp.html.

- Chinese Government. 国家新型城镇化规划 (2014–2020年) [National New-Type Urbanization Plan (2014–2020)]. March 16, 2014. Accessed January 31, 2024. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2014-03/16/content_2640075.htm.

- Chinese Government. 京津冀协同规划纲要 [Outline Plan for Coordinated Development of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region]. 2015. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://zyk.bjhd.gov.cn/zwdt/szgb/zcjd/201810/P020170510385409623558.docx.

- Clark, Greg. Local Development Benefits from Staging Global Events. Paris: OECD, 2008.

- Cook, Ian G., and Steven Miles. “Beijing 2008.” In Olympic Cities: City Agendas, Planning and the World’s Games, 1896–2020, edited by J. R. Gold, and M. M. Gold, 359–377. London: Routledge, 2017.

- Friedmann, John. “The World City Hypothesis.” Development and Change 17, no. 1 (1986): 69–83.

- Gold, John R., and Margaret M. Gold. “Introduction.” In Olympic Cities: City Agendas, Planning and the World’s Games, 1896–2020, edited by J. R. Gold, and M. M. Gold, 1–17. London: Routledge, 2017.

- Hall, Peter. The World Cities. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1984.

- Hall, Peter. “Seven Types of Capital City.” In Planning Twentieth Century Capital City, edited by David Gordon, 8–14. London: Routledge, 2006.

- Hebei Government. 河北雄安新区规划纲要 [Outline Plan for the Hebei Xiong’an New Area]. 2018. Accessed January 31, 2024 http://www.xiongan.gov.cn/2018-04/21/c_129855813.htm.

- Hu, Richard. The Shenzhen Phenomenon: From Fishing Village to Global Knowledge City. London: Routledge, 2020.

- Hu, Richard. Reinventing the Chinese City. New York: Columbia University Press, 2023.

- Hu, Richard, and Weijie Chen. Global Shanghai Remade: The Rise of Pudong New Area. London: Routledge, 2019.

- Huxiu. “北京南城为什么这么惨” [Why is South Beijing So Inferior]. July 17, 2018. Accessed February 24, 2024. https://www.huxiu.com/article/253187.html.

- IQAir. Beijing Air Quality Report: State of the Air and Progress from 2008 to August 2019. 2019. Accessed January 28, 2024. https://www.iqair.com/assets/2019-beijing-air-quality-report.pdf.

- IQAir. Air Quality in Beijing. 2024. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://www.iqair.com/au/china/beijing.

- Jia, Dongting. “中轴线, 从亚运到奥运的心理轴线” [Axial Line, a Psychological Line from Asian Games to Olympic Games]. Life Week 45 (2007). Accessed February 16, 2024. https://www.lifeweek.com.cn/article/35749.

- Kuhn, Robert Lawrence. “The Five Major Development Concepts.” China Daily, September 23, 2016. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2016-09/23/content_26872399.htm.

- Meng, Lingcheng, and Virgilio Neto. “Beijing: The World’s First Dual Olympic City.” October 27, 2021. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://olympics.com/en/news/100-days-to-go-beijing-worlds-first-dual-olympic-city.

- Muñoz, Francesc. “Olympic Urbanism and Olympic Villages: Planning Strategies in Olympic Host Cities, London 1908 to London 2012.” The Sociological Review 54, no. 2_suppl (2006): 175–187.

- National Audit Office. 北京奥运会财务收支和奥运场馆建设项目跟踪审计结果 [Audit Report on the Revenues and Expenditures of the Beijing Olympics and the Construction of Olympic Venues]. 2009. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2009-06/19/content_1344706.htm.

- Nitsch, Volker, and Nicolai Wendland. “The IOC’s Midas Touch: Summer Olympics and City Growth.” Urban Studies 54, no. 4 (2017): 971–983.

- Preuß, Holger, Wladimir Andreff, and Maike Weitzmann. Cost and Revenue Overruns of the Olympic Games 2000–2018. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 2019.

- Ren, Xuefei. “Olympic Beijing: Reflections on Urban Space and Global Connectivity.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 26, no. 8 (2009): 1011–1039.

- Ren, Xuefei. “Aspirational Urbanism from Beijing to Rio de Janeiro: Olympic Cities in the Global South and Contradictions.” Journal of Urban Affairs 39, no. 7 (2017): 894–908.

- Sassen, Saskia. The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo. Princeton University Press, 1991.

- Schneider, Florian. Staging China: The Politics of Mass Spectacle. Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2019.

- Song, Yingchang. “京津冀协同发展的回顾与展望” [Retrospect and Prospect of the Coordinated Development of Beijing, Tianjin, and Hebei]. Urban and Environmental Studies 2 (2017): 3–15.

- South China Morning Post. “Beijing’s ‘Poverty Belt’ Raises Alarm.” February 27, 2006. Accessed January 31, 2024 https://www.scmp.com/article/538193/beijings-poverty-belt-raises-alarm.

- The Paper. “从亚运到夏奥再到冬奥, 中国谱写32年体育强国梦” [From Asian Games to Summer and Winter Olympic Games, China’s 32-year Pursuit for a Strong Country of Sports]. February 21, 2022. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://m.thepaper.cn/kuaibao_detail.jsp?contid=16769833&from=kuaibao.

- The Paper. “徐匡迪详解雄安新区规划” [Xu Kuangdi on the Planning of Xiong’an New Area]. June 7, 2017. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://m.thepaper.cn/kuaibao_detail.jsp?contid=1702581&from=kuaibao.

- The World Bank. Urban Population (% of Total Population)—China. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS.

- United Nations Environment Programme. A Review of 20 Years’ Air Pollution Control in Beijing. 2019. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/27645/airPolCh_EN.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Wright, Jamie. “From Poverty to Prosperity: The Story of Chongli.” China Focus. November 27, 2019. Accessed January 31, 2024. http://www.cnfocus.com/from-poverty-to-prosperity-the-story-of-chongli/.

- Xinhua News Agency. 千年大计、国家大事 [Millennium Plan, National Initiative]. April 13, 2017. Accessed January 31, 2024 from http://www.xiongan.gov.cn/2017-04/13/c_129769126.htm.

- Yong, Yin. Report on the Work of the Government: Delivered at the First Session of the Sixteenth Beijing Municipal People's Congress on January 15th, 2023. 2023. Accessed January 31, 2024. https://wb.beijing.gov.cn/en/center_for_international_exchanges/headlines/202301/t20230128_2907664.html?

- Yu, Shuishan. “Redefining the Axis of Beijing: Revolution and Nostalgia in the Planning of the PRC Capital.” Journal of Urban History 34, no. 4 (2008): 571–608.

- Zhang, Li, and Simon Xiaobin Zhao. “City Branding and the Olympic Effect: A Case Study of Beijing.” Cities 26 (2009): 245–254.