ABSTRACT

Chosen three times as the host city for the Summer Olympic Games (1940, 1964 and 2020), Tokyo's city layout is historically linked to the Olympics. Including the bid project for the 1960 and the 2016 Games, Tokyo has presented five Olympic projects, each time with five different urban visions which enlighten the nature of the past and present political Japanese regimes. The recurrence of the Olympic Games in the planning and growth of Tokyo leads to the idea of a major influence of the Olympics both on the physical evolution of the urban structure but also on that, immaterial, of its planning culture – or, in other words, on the representations, imaginary and practices of the institutional stakeholders of Tokyo's urban fabric. The aim of the paper is therefore double. First, it analyses each urban vision of the Games of 1940, 1964 and 2020. Secondly, it analyses the influence of each Olympic project on greater Tokyo's urban planning and regional development, as well as the influence of each Olympiad on the following ones. Doing that, the paper discusses the formalization of a planning culture through organizing the Olympics on the long run in Tokyo.

Introduction – a near-century of Olympic planning in Tokyo

Chosen three times as the host city for the Summer Olympic Games (1940, 1964 and 2020), Tokyo’s city layout is historically linked to the Olympics. That level of interaction with the Games is rare and has so far only been matched by London, although Paris (from 2024) and Los Angeles (2028) will soon equal that number. The Japanese capital's relationship with the Olympics has, however, at times experienced significant difficulties. The 1940 session was cancelled due to WWII, and the 2020 session was postponed for a year due to the global coronavirus pandemic, becoming Tokyo 2020 + 1. In addition to those three successful bids, Tokyo has also had two failed bids to host the games: 1960, which was ultimately lost to Rome, and the 2016 Games, lost to Rio de Janeiro. The formalization of a development project for a summer Olympics application requires years for unrealized projects and almost a decade for project winners. Therefore, the city’s five Olympic projects formalized from the 1930s to the 2010s occupied the public (and private) teams in charge of the development of Tokyo for almost half of the period in question – a considerable time commitment.

The recurrence of the Olympic Games in the planning and dynamics of urban growth in Tokyo thus leads to the question of the influence of the Olympics not only on the physical evolution of the urban structure, but also on the intangible nature of the city’s planning culture. Is there any broad continuity in urban planning across Tokyo 1940, Tokyo 1964, and Tokyo 2020? To what extent has each Olympics impacted not only the evolution and urban trajectory of Tokyo, but also the practices, representations and postures of the actors involved in Tokyo’s urbanization and planning? This article formulates the hypothesis that hosting the Olympic Games has had a great material and immaterial influence on the logic and dynamics of Tokyo's development from the 1930s to the present day. In particular, the article forwards the idea that Tokyo’s Olympic planning over nearly a century has generated a significant legacy, although one that is fairly hidden within the built-up environment itself. This legacy consists of a culture of Olympic event planning that remains in the logics, dynamics and practices of urban making in Tokyo. This article contends that this culture of planning through events is not only the most important legacy of the Tokyo Olympics but also, paradoxically, its least documented and most underestimated legacy. This lack of in-depth prior analysis grants a degree of urgency to its re-evaluation in academic literature.

The first section of this report contains a literature review on the relationship between the Olympics and urban planning. This has a double focus. First, it looks at the few available works dedicated to urban planning in Tokyo. Second, it examines the largely unknown issue of an Olympics-related event planning culture. The second section presents the research materials and the methodology used for their analysis. A third section analyses the urban planning component of each Olympiad and Olympic project in Tokyo since the 1930s. A final section discusses the status of each Olympiad in terms of the dynamics, logics and practices of planning in Tokyo, and their role in the formalization of a possible culture of planning through Olympic events. The article concludes with a reflection on the nature and scope of the planning culture that has evolved from the recurrence of Olympic planning efforts in Tokyo. In doing so, it argues that hosting the international mega-event of multiple Olympics has enabled Japanese stakeholders to resolve internal tensions inherent in the development of their capital.

Literature review

The Olympics is the subject of numerous academic works. However, the notion of legacy is fairly recent and, while the subject of some notable publications in Western languages, it is still very little studied in Japan. The notion of planning culture analysed here is absent from any publication on Olympic studies or even events studies, and therefore constitutes a real contribution both to Olympic studies and planning studies in Japan.

Planning and legacy in Olympic studies

The impact of the Olympic Games on host cities is a topic particularly well analysed in the scientific literatureFootnote1 and has led to a critical questioning of the methodologies used.Footnote2 The relationship between major sporting events and urban regeneration is also well documented.Footnote3 The acceleration of urban regeneration for the Games is observed in many host cities: BarcelonaFootnote4, AthensFootnote5, BeijingFootnote6, and even London.Footnote7 The question of long-term impact is, however, still little addressed. This includes recent analysis of older iterations of the games that take into account the different phases host cities go through – candidacy, preparation, legacyFootnote8 – but without analysing the post-event dimension over more than a decade.

The interest of academic literature in the urban dimension of a sporting event such as the Olympics is quite recent and dates mainly from the Barcelona Games in 1992.Footnote9 It follows the entrepreneurial turn in public city planning policies of the 1980sFootnote10, when municipalities began to view hosting the Games as an opportunity for the regeneration of dilapidated neighbourhoods, particularly with a view to post-industrial requalification of wasteland sites.Footnote11 The Los Angeles Games in 1984 were thus the occasion for a definitive shift in urban governance towards a neo-liberal logic which seized upon the event as a way to catalyse regeneration programmes carried out by public-private partnershipsFootnote12, first at the neighbourhood level, then, in the 1990s and 2000s, at the entire city level.Footnote13 The Tokyo 2020 Games are part of this dynamic and as such benefit from the urban renaissance policy promoted by the central government in 2002 and reinforced in 2011, the effects of which are ongoing.Footnote14

At the same time, competition to secure Olympics-hosting rights between countries from the 1920s until the 1970s moved towards a competition between metropolises after the 1980s.Footnote15 Olympism turned from geopolitical issues, even quasi-militarized ideological oppositions, to issues of economic competition between large urban regions. The Games were then increasingly subsumed into the soft power efforts of urban territories and the processes of financial and cultural globalization.Footnote16 In this sense, they fall within the framework of fantasy city studiesFootnote17 or festive city studiesFootnote18 based on post-industrial logics of capital fixation in a limited number of metropolitan territories.Footnote19 This was the case in 2012 in London with the renovation of Stratford into a new commercial and residential centre; in 2008 in Beijing with the development of the north and the creation of a scientific park nearbyFootnote20; and in 2020 in Tokyo with the requalification of the waterfront into a district and sustainable activity zone.Footnote21

In view of the spectacular growth in budgets allocated to Olympic Games planning, the attention of academic works has focused from the 2000s on the notion of the legacy of the event and its inscription in long-term urban planning.Footnote22 Since the financial difficulties of Montreal in 1976, evaluation of the economic fallout from the Games on the local and national economy of host territories and the valorization of its material effects – sporting infrastructure in particular – constitute central issues on which citizen debates and opposition among residents have focused.Footnote23 However, the intangible inscription of the Olympics over the long term is a subject that is still rarely discussed or studied.

The notion of legacy is different to that of impact.Footnote24 The latter refers to a short- or medium-term phenomenon linking a mechanistic and immediate relationship between cause and effect. Contrastingly, the notion of legacy is a social construct which supposes transmission between people or communities over the long term.Footnote25 It is therefore a transgenerational process. It is also based on a double component: a material dimension, observable and quantifiableFootnote26, and an immaterial dimension. The latter is often reduced to the symbolic. However, it is in truth much broader than that, affecting practices, representations, behaviour and even the relationships between groups across space and time.Footnote27 It is therefore a notion related to culture, of which the culture of planning is part. Legacy thus presupposes the existence of formal transmission mechanisms, favouring the constitution or reactivation of material and immaterial social links. The organization of an Olympics involves highly codified and ritualized decision-making processes and planning mechanisms. It therefore constitutes a powerful lever for the reactivation and transmission of memory as well as the enhancement of heritage, as has been the case in Tokyo, which has hosted the Games on average every 20 or 30 years over a century. Legacy is therefore not a natural or automatic principle. It must instead be understood as an immaterial social construct, a living material to be nourished.Footnote28

The Tokyo Games and Japan in Olympic studies literature

In Japan, Olympic studies is a dynamic research fieldFootnote29 affected positively by each new iteration of the Games, as seen in the field’s revival during the 2010s ahead of Tokyo 2020.Footnote30 However, the attention given to each Games in the existing literature is unevenly distributed depending on the time period, the Olympics in question, and the disciplinary fields mobilized. The 1940 Games are, for example, the subject of just a small number of works, prompting Sandra Collins to describe them as the missing Olympics.Footnote31 The 2020 Games, for their part, offered an opportunity to partially rediscover those ‘missing’ Games.Footnote32 But few works have attempted to draw a parallel between the war-cancelled 1940 Olympics and the misadventures of Tokyo 2020, which was itself severely comprised by the global COVID-19 pandemic.

Much has been written about the 1964 Games, from their preparation and holdingFootnote33, to their subsequent influence on Tokyo and on wider Japanese society. Most considerations of the capacity of the Olympics to influence the development of host cities, however, postdate the 1964 Games. The attention paid to the 2020 Games therefore provides an opportunity to rediscover the 1964 Games also, but in a new epistemological light.Footnote34 Previous studies have highlighted the pivotal role of Tokyo 1964 in linking the pre-war period, the high economic growth period, and the contemporary period.Footnote35 Other works have analysed the correspondences between Tokyo 1940 and Tokyo 1964 from the critical historical perspective allowed by the temporal distance of the 2010s.Footnote36 In this vein, certain works also began to emphasize the intangible, even invisible, legacy of past Olympics on the development of Tokyo, as well as on subsequent Olympics.Footnote37

Due to their topicality on the one hand, and the maturity of Olympic studies as an academic field on the other, the Tokyo 2020 Games led to multiple publications, mainly in the fields of economics and media studiesFootnote38, but also within the fields of sociology and politics. As such, the political field saw works related to various anti-Olympic movementsFootnote39 and others concerning the COVID-19 pandemic and its effect.Footnote40 More so than for either the 1940 or 1964 Olympics, urban studies also saw the analysis of the urban project of Tokyo 2020 from the perspective of a critical political economy. This relates to its planning logic as well as its effects on the urban fabric of Tokyo.Footnote41 To date, no work has examined Tokyo's Olympic trajectory since 1940 from an overarching historical perspective, much less the planning culture that has emerged in Japan as a result of hosting the Games.

A culture of planning and urban making through Olympic organization

The notion of ‘planning culture’ is almost absent from Olympic studies, as well as from research in the humanities and social sciences produced in Japan. In Europe, research on planning culture appeared in the 1990s, first in German with Planungskulturen, then in English.Footnote42 The rise of a European academic literature focusing on ‘planning culture’ can be explained by two factors: on the one hand, the cultural turn in economics and political sciences of the 1990sFootnote43; on the other hand, the intensification of European integration after the Treaty of Maastricht which initiates an intense reflection on the cultural differences of territorial planning between member countries and the means of optimal coordination for the major transnational works carried out in the Union.Footnote44 According to Sanyal, a planning culture relies on ‘a collective ethos and dominant attitudes of planners regarding the appropriate role of the state, market forces, and civil society in influencing social outcomes’.Footnote45 However, there is no consensus on the definition of either ‘planning culture’ as a concept or indeed, beyond that, the more encompassing concept of ‘culture’.Footnote46 Defining what a ‘development culture’ is, however, requires first defining what is meant by the term ‘culture’. For GullestrupFootnote47, culture refers to

world conception and the values, moral norms and actual behavior – and the material, immaterial, and symbol results thereof – which people (in a given context and in a given period of time) take over from a preceding ‘generation’ which they – possibly in a modified form – seek to pass on to the next ‘generation;’ and which in one way or another make them different from people belonging to other cultures.

We could thus formalize the culture of planning as a nebulous collection of knowledge, practices, values, norms and representations common to a group of planners, both public and private. This planning culture is transmitted and gradually transformed between generations during the long series of planning projects – whether these projects are carried out or not. In this context, any event, in particular the Olympic Games, would constitute a key moment during which the culture of planning would experience a sort of collective epiphany. Not only would it be explained and formalized via the production of documents, maps, plans and texts accompanying the preparation of the event, but it would be transmitted from one generation to another thanks to the intensification of exchanges and debates, the multiplication of discussion forums and meetings, as well as the production and circulation of grey literature that is both expert and general for public consumption. To put it another way, the Olympic Games would then be the moment when, in the parlance of pragmatic sociology, a grammar is put in place and manifested in the field of planning. Namely, it is the point at which ‘more or less general normative benchmarks of validity, both integrated [in] cognitive skills [of actors] and inscribed in devices (and in particular object devices), rooted in situations’Footnote49 become, one could say, ‘territories’ or ‘spaces’ designed by a society according to its own culture.

Given their weight in contemporary imaginations, this article discusses the influence of the Olympics on the culture of planning in Tokyo, from the cancelled session of Tokyo 1940, through to the postponed Tokyo 2020. The main hypothesis is based on the idea that the 1964 Games constituted the founding act of a culture of urban planning in Tokyo via sporting events. It is broken down into three sub-hypotheses. First of all, the 1964 Games partly influenced the development of the 2020 Games as well as the unrealized 2016 project through its symbolic importance in Japan’s collective consciousness. Secondly, the 1964 games exerted a broad effect over the framework for Olympic planning, thus influencing the overall layout of Tokyo throughout the twentieth century. Finally, the ultimately cancelled 1940 session laid the foundations for an Olympic culture of Tokyo planning that was then reactivated and operationalized in urban planning practices on the occasion of the 1964 Olympics.

Materials and methods

The methodology of this research is essentially qualitative and combines three approaches. First of all, it is based on numerous semi-structured interviews with institutional actors made up of developers, politicians, members of the municipal technical teams in charge of the candidacy files and the organization of the Games, academics and opponents of the events. These interviews were conducted over ten years, most of the time in Japanese, sometimes in English. The methodology then consisted of the analysis of an extensive range of grey literature. This included development plans and numerous maps available from government agencies and from private companies involved in the construction of the Olympic infrastructures, but also from other more or less related projects taking place in Tokyo during the preparation period for the Games (mainly those of 2020, given the obvious generational connection). This work was supplemented by archival work at the Olympic Studies Centre, where the documents of the 1940 and 1964 projects are conserved (notably the candidacy files). It also extended to correspondence between the IOC, the various Japanese Olympic Committees and the Organizing Committees of each Olympiad, as well as numerous press cuttings in English and Japanese from the 1930s–1940s and 1950s–1960s. These archives made it possible to establish, via correspondence and press clippings, the state of mind of each organizing team, as well as that of the actors in charge of each project, their interests, and the issues they confronted. Finally, field work carried out over a decade included visits to existing Olympic sites, often accompanied by experts who commented on the principles of spatial and urban organization.

Results – Olympic planning in Tokyo: from sports infrastructure to urban development

Cancelling Tokyo 1940: planning a non-event

The 1940 Olympic Games occupy a special place in the history of modern Olympics for two reasons. First, these were to be the first Olympic Games to take place in Japan and Asia, outside the closed circle of European and North American countries. These were then the second (and last) Summer Games to have been cancelled, in this case due to war (similarly to the 1916 Berlin Games).

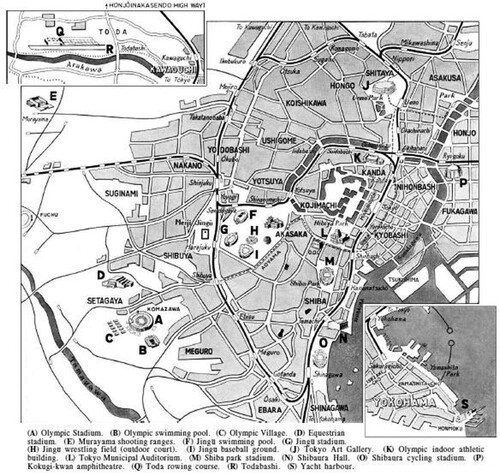

From an urban planning point of view, the Tokyo 1940 development project obeys two apparently opposing spatial logics: a concentration of the main infrastructures within two clusters, and a residual dispersion of secondary facilities (). A first cluster brings together most of the sports infrastructure close to Tokyo city centre. It extends from the districts of Meiji and Yoyogi on its western fringes, to Akasaka on its eastern borders. It includes, among other things, a swimming pool, a stadium, a baseball field, and a smaller outdoor field. A second cluster constitutes the symbolic heart of the 1940 project including, among other facilities, the Olympic stadium, the athletes’ village and the main swimming pool. It is located in the Komazawa district, the frontier of urbanization at that time. In addition to these two clusters for the 1940 project, there are a number of isolated facilities, such as the racecourse in Setagaya on the urban fringes of the city, the velodrome in Shinagawa on the industrial waterfront, the shooting range in Murayama along the green belt of greater Tokyo, and the athletics centre in Kanda in the city centre.

Figure 1. Development plan for the Tokyo 1940 Summer Olympic Games. Source: Report of the Organizing Committee on its work for the XIIth Olympic Games of 1940 in Tokyo (1940): 51.

The 1940 Olympic project was part of the development plans of the 1930s which prepared the country for war and anticipated the possibility of a large-scale attack on the Japanese capital. Thus, we observe three main planning logics. First, the Olympic project structures around Harajuku, Yoyogi, Shibuya and Komazawa, a new urban centre on the western fringes of Tokyo, less densely populated than the downtown area to the east or the historical/ geographic centre of the city. This reflects a level of control exerted over the urbanization process aimed at preventing its disordered spread over the green belt surrounding Tokyo. This dynamic accompanies the densification of urbanization fronts that opened to the west following the inauguration of stations on the Yamanote-sen circular line, completed in 1925.

Olympic developments, in particular the scattered sports infrastructure and numerous parks constructed in densely built spaces, increased the number of green spaces and collective facilities. These could be transformed into fallback and refuge areas for residents and the army in the event of an enemy attack on the capital and/or natural disasters (fires, earthquakes, etc.). The aim was therefore to improve the resilience of Tokyo's urban spaces in the face of military and fire risks, among others. This planning strategy was based on recent lessons learned during the mega-fires which followed the great Kanto earthquake of 1923, which destroyed a large part of Tokyo. During those post-earthquake fires, the city’s wooded areas resisted much better than mineralized public spaces. This point explains why a certain amount of secondary sports infrastructure was scattered throughout the urban fabric of Tokyo, in particular the industrial waterfront in Shinagawa, the densely built-up centre in Kanda or even the eastern downtown area – i.e. the spaces most damaged by fire in 1923. These planning considerations accompanied a strategic dispersion of activities, which the central government encouraged in 1936 with the enactment of the National Territory Plan for Kantô (Kantô kokudo keikaku). The following year, the Air Defense Law (Bôkû hô) led to the reinforcement of green spaces serving as buffer spaces and evacuation zones. The military objective of de-concentrating urban populations, activities and infrastructures at the city’s outskirts also served to benefit private railway companies (ôtemintetsu). These companies were responsible for planning the first ring of suburbs around the city centre. There they erected quality housing developments for the upper-middle class (as in Sendagaya and Suginami) and garden cities, such as Den’en Chôfu, (by Tôkyû), or Tokiwadai (by Tôbu).Footnote50

Finally, selection of Komazawa as the centre of the 1940 Olympic project can be explained by the relationships the imperial-militarist regime established with Japan’s conglomerates (the zaibatsu), in this case the sprawling railway company Tokyu. The latter had built a new suburban railway line near Komazawa in the 1920s which connected the centre of Tokyo to the high-end garden cities it had built in the green belt, in particular Den'en Chofu (Kubo, 2017). The economic model of private railway companies (ôtemintetsu) was based on a virtuous circle which linked growth in railway traffic with residential developments at stations served by the newly built lines. Rail traffic provided significant cash flow, which could then be invested in residential real estate along the lines, increasing the pool of commuters and therefore passengers on the lines. This generated ever more cash flow for mobilization in the form of real estate, therefore proliferating the urban sprawl. This model ensured the growth of Japanese metropolises throughout the twentieth century. The location of the Olympic stadium and the athletes’ village in Komazawa was therefore, in the 1930s, a form of clientelism between Tokyu and the central government. The system aimed to increase attendance on the railway company's lines and therefore, ultimately, its anchorage in western Tokyo.

Tokyo 1964: bringing modernity to Japan

Following the Japanese Olympic Committee’s decision to cancel the 1940 Games, the reaction of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) was particularly strong. In the correspondence between the two bodies, the IOC threatened to never again grant the Olympic Games to Japan. However, it was not even a quarter of a century later, in 1964, when Tokyo again hosted the Games. That followed an unsuccessful attempt to obtain the 1960 Games, which was ultimately hosted by Rome.

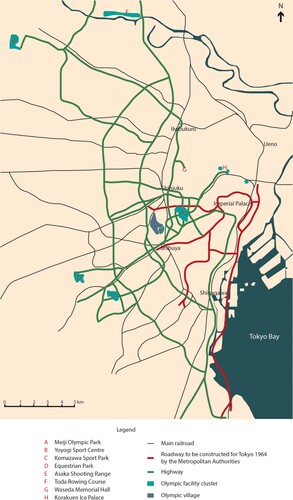

In this new Olympic project, once again the urban spaces located to the west and south of Tokyo’s hyper- centreFootnote51 benefited from most of the infrastructure, which was distributed in the form of three main clusters (). The Meiji Cluster, also called Meiji Park, is the smallest, but hosted the National Olympic Stadium, where the opening and closing ceremonies of the 1964 Games took place. Originally, the site was occupied by the Meiji-jingû Gaien Stadium where the Meiji Shrine Games took place almost annually between 1924 and 1943 and where the Far Eastern Games of 1930 also took place. Demolished in 1956, it was replaced by the Olympic stadium in 1958, which was used for the first time that year during the Asian Games. In this respect, it is striking to note that the Far Eastern Games, which became the Asian Games after the war, played the role of Olympic antechamber for the 1940 and 1964 sessions. This acknowledgement feeds into the hypothesis that Tokyo’s planning culture through events existed even prior to the Olympics.

Figure 2. Development plan for the Tokyo 1964 Summer Olympic Games. Source: Organizing Committee for the Games of the XVIII olympiad, 1964.

The second cluster, the largest of the three, was located in Komazawa. Named ‘Komazawa Olympic Park General Sports Ground’, the site was also further south, at the urbanization frontier of the time. It accommodated much of the Olympic infrastructure, including a large athletics stadium. The site was previously occupied by a Shôwa era golf course. It was then used by the military during the 1940s as agricultural land and air defense space in case of air raids. Tôkyû Corporation subsequently used the land to house a sports facility for its in-house baseball team from 1953. Work on Olympic facilities began there in 1962, a year after the Games were awarded to Japan. In total, the complex includes ten facilities, half of which were built especially for the 1964 Olympics.

Finally, a third cluster, located to the West in Jingu, hosted both the athletes’ village and Tange Kenzo’s renowned sports complex, which included a stadium and a gymnasium. More than any other Olympic project, the athletes’ village constituted a major development challenge for both local and central government alike in the 1950s and 1960s. Originally used as a parade space for the Japanese Imperial Army, the site was requisitioned by the US Air Force in 1946 following the military defeat of Japan. Named Washington Heights, the complex housed 827 military housing units until 1964. Despite the Mutual Cooperation Treaty of 1960, which stipulated that Washington Heights must remain in operation and under the military administration of the US Air Force, the US government agreed to return the site to Japan on 30 November 1962, allowing work on the stadium and Yoyogi gymnasium to start in February 1963. Those constructs were completed on 31 August 1964. However, unlike most traditional Olympic villages, Tokyo’s did not give rise to a major construction project. During the games, the former homes of US soldiers were used to house national Olympic teams. They were only demolished after the Games, with the Dutch team house the only one preserved. Currently, in addition to sports facilities, the site houses the media centre for public broadcaster NHK.

Aborted Tokyo 2016: a sustainable turn for a more compact Olympics

After a long period of almost half a century, the end of the 2000s saw the re-emergence of the Olympic conversation in Tokyo with the city’s unsuccessful bid for the 2016 Games, which ultimately went to Rio de Janeiro. The intrinsic quality of the Tokyo proposal had, however, met the requirements of the slimmed-down and sustainable Olympic city model of the 2000s, and was based on two principles: compactness and inter-linkage (musubi).

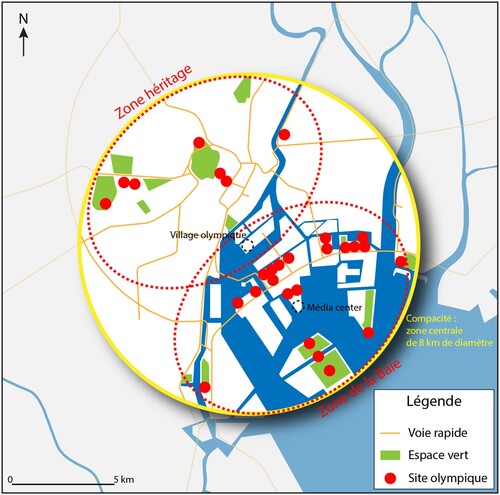

The principle of urban compactness was present in the Tokyo bid on two levels. On a macro-urban scale, more than 95% of sports facilities and services would be concentrated within a 4-kilometre radius around the Olympic stadium. This would be located in Chûô Ward’s ‘Harumi’ development – an area of reclaimed land on the waterfront. On this scale, the 2016 Olympic project was made up of two large groups: a so-called Legacy Zone, in reference to the infrastructure inherited from the 1964 Games and partially reused; and a seafront area named ‘Tokyo Bay Zone’. The Olympic stadium served as a juncture between the two areas. On a more local level, the project also linked five Olympic infrastructure clusters, bringing together most of the sports and logistical facilities to be used in the Games.

The central waterfront cluster that served as the juncture between the Heritage zone and the Tokyo Bay zone was named ‘Musubi’. It housed the Olympic stadium in a basin around which the rest of the infrastructure was built. It also housed the Olympic village, the media hotel, the main press centre, as well as six competition venues. The other four clusters were evenly distributed between the Heritage Zone and Tokyo Bay Zone. The Heritage Zone’s two clusters were Yoyogi, which remained from the 1964 Games, and the Palace, an area that includes the imperial grounds and other districts forming the traditional seat of power in the city. The Tokyo Bay Zone’s two clusters corresponded to the key spaces of the city’s contemporary urbanization frontier. The cluster named Island of Dreams (Yume no shima) symbolized the city’s success in developing green spaces reclaimed from the sea. The Sea Forest (Umi no mori) cluster was a continuation of the theme of revegetation on the Island of Dreams, with the eponymous park’s design and construction led by Andô Tadao.

The plan was to build the Olympic village in Ariake-Kita. This would be part of a movement to convert Tokyo's open spaces into a showcase for sustainability – a continuity project that dovetailed with the reorientation of the Odaiba and Rinkai Fukutoshin development project. In the Olympic Village, the principle of compactness was also found on two levels. In terms of the urban area, its central location made competition sites accessible in less than 10 min for 70% of the athletes. In terms of the neighbourhood itself, the compactness of the building meant all housing and services lay within 500 metres of the main entrance. Universal design considerations made it possible to adapt housing for people with disabilities, particularly those in wheelchairs. The buildings were no higher than nine floors and offered apartments ranging from 63 m² (for four people) to 136 m² (for eight people). Each building was built to the standards of passive architecture, including consideration of the microclimate of the ground, energy savings and the greening of roofs and exterior walls.

Tokyo 2020(+1): the empty shell of an Olympics under quarantine

On 7 September 2013, the Olympic Committee awarded the 2020 Games to Tokyo. The city’s 2020 Olympic development project was based on the clear principle of ‘keeping the best of 2016, improving the rest’. The main principles of the 2016 project were therefore retained. The 2020 plan reused the division of the centre of Tokyo between Heritage Zone and Tokyo Bay Zone, retaining the same conceptual distinction between the two. Namely, the Heritage Zone made use of the infrastructure built for the 1964 Games, while the Tokyo Bay Zone created new infrastructure, integrating these into a resolutely urbanized and futuristic view of Tokyo Bay (). The Tokyo Bay Zone holds most of the newly built Olympic facilities and constitutes the new urbanization frontier for the metropolis that emerged in the 2000s and 2010s. The Olympic village is located within that perimeter, within the so-called Harumi reclaimed land development. The Olympic stadium was built on the former site of the Tokyo 1964 stadium. Its construction gave rise to numerous tensions, most notably around the competition for who would act as architect. Held in 2013, the first round of that competition was won by the office of Anglo-Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid. However, Hadid’s candidacy was cancelled by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe on 16 July 2015. Officially, the reason given was the project’s disproportionate cost. However, when the next round was held five months later, the selection committee refused Hadid’s right to reapply with a new stadium project. Two Japanese architects were then selected for the final phase: Toyo Ito and Kuma Kengo – both of whom enjoyed the backing of Japanese construction companies Taisei Corp. and Azusa Sekkei Co. – with Kuma ultimately winning the top prize.

Figure 3. Location of the main sports venues for the Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games. Source: Tokyo 2020 bid file, Vol. 1, pages 2–3. Cartography: the author.

Tokyo’s 2020 planning efforts were also closely linked to issues of public health, from the application phase all the way to the event itself. Tokyo filed its bid for the Games in September 2011. That was just months after the triple disaster of 11 March 2011, when a high-magnitude earthquake followed by a deadly tsunami led to a nuclear meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi Power Plant. While the risks of radioactive contamination in the city could have led to a de facto disqualification of Tokyo’s candidacy, the IOC proclaimed the city’s victory on 7 September 2013. Then at the start of 2020, almost a decade after Fukushima and with the event deadline fast approaching, the COVID-19 pandemic suddenly spread throughout the world. At the urging of domestic health authorities, Japan’s central government announced on 24 March 2020 that it would postpone the Tokyo Olympic Games 2020 by one year.Footnote52 The following year, due to an increase in cases and the rise of local opposition to holding the event, the central government decided to hold the Games without an audience, rendering the spectator-less stadiums nothing but large empty shells. Olympic sites including the athletes’ village were quarantined in what the media called a ‘sanitary bubble’ – a public health measure greatly assisted by much of the Games’ central but isolated location in Tokyo Bay.

Discussion

A huge amount of infrastructure was either created or rehabilitated for the three Olympics of 1940, 1964 and 2020. Given the scale of the spaces each project invested in and developed, it is now necessary to discuss the material and intangible impacts of the Olympics on Tokyo’s urban development from the perspective of this article’s general hypothesis. Namely, that the city’s planning culture evolved through the medium of hosting Olympic events. If we can then indeed speak of an ‘Olympic planning culture’, what can be considered its causes, its main characteristics, and the specific timeframe in which it first appeared in Tokyo? To answer these questions, it is necessary to first establish the influence of each Olympiad on the development of Tokyo, and the influence exerted by each iteration of the Games on those that followed.

Beyond the Games, what influence has each Olympiad had on the development of Tokyo?

Planning dynamics of the 1930s, resulting in the 1940 Olympic project, determined the general structure of the metropolitan core and outskirts of Tokyo. Accompanying a dynamic of not only urbanization around the new central districts of Shibuya and Shinjuku, but also a dynamic of suburbanization in western Tokyo along the Tokyu rail lines, the Olympic project of the 1930s formalized the general spirit of structural development in post-war Tokyo. The symbol of this continuity is the shinkansen high-speed rail line, inaugurated for the 1964 Games, but designed during the key period of the 1930s. Although the 1940 Olympic project did not include the shinkansen’s commission, the government of the time launched preliminary work on the line in 1938 with the acquisition of land and the construction of engineering structures. Although the work was abandoned in 1943 due to WWII, it was resumed after the war’s end, with the 1964 Olympic project set as a delivery horizon. The shinkansen thus symbolically connects the pre- and post-war periods in a continuity overseen by the same actors in charge of the two Olympic projects.

The 1964 Olympic Games have acquired an almost mythological dimension in the minds of many Japanese people.Footnote53 After the widespread destruction of the Second World War came an intense period of reconstruction characterized by the creation of public infrastructure, much of which is still in operation half a century later. This is the case for many of the transport networks across Tokyo and Japan, including urban highways and the shinkansen. The scale of Tokyo 1964 projects had a profound impact on the structure of Tokyo in the long term, which helps explain the subsequent trajectory of certain urban areas and neighbourhoods. It accelerated the urbanization of Tokyo’s western districts, namely Shibuya and Shinjuku, but also further west in the districts of Suginami and Setagaya. It also helped make Shibuya a major hub of Tokyo's cultural industry, later becoming a sub-centre (fukutoshin) in the 1980s as part of the metropolitan government's polycentric policy. In the 2000s, Shibuya became a creative cluster in line with the government’s National Urban Renaissance Policy framework.Footnote54 Finally, the inauguration of the shinkansen reinforced the centrality of the Marunouchi District as Tokyo’s principal business hub. It also boosted the growth of Shinagawa to the south, which many years later became the gateway to the 2020 Olympic project thanks to its connection to Haneda International Airport.

The weight of the 1964 Olympic Games on Japan’s collective consciousness also constitutes a turning point for Tokyo, and for the country as a whole, that functions on three different levels. At the geopolitical level, the 1964 iteration of the Games presented an opportunity for Japan reclaim its sovereign territory – the parts of Tokyo ceded to forces US occupation forces in the post-war period – via the construction of Olympic facilities on that land. This was the case for both the athletes’ village/ sports complex in Yoyogi and the athletics stadium in Komazawa. It also constitutes a turning point at the symbolic level, formalizing the entry of Japan into the circle of industrialized and developed countries, and Tokyo into the circle of modern capitals. Finally, with the 1964 Games, Japan leveraged the Games to show the world its own culture and celebrate its recent past. This soft power dynamic is inscribed in the territory itself, both in the architecture of the various sports facilities, but also via their insertion into the local urban fabric of Tokyo.

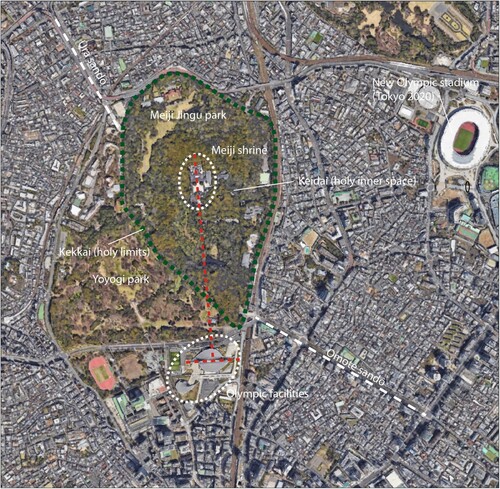

The Yoyogi stadium and gymnasium, for example, are built on the former site of Washington Heights near Meiji Shrine. Ines Tolic has shown that, at the architectural level, the shape of the Yoyogi Olympic gymnasium echoes that of a Buddhist temple, using a refined and concrete form found in Western modernist architecture and the international style.Footnote55 At the urban planning level, the lines of flight and the layout of the complex inscribes in the territory a dialogue with the process of modernization experienced by Japan from the Meiji era onwards. Within the immediate vicinity of the Olympic site in Yoyogi Park, the famous Meiji Shrine commemorates the memory of the eponymous emperor, considered the founder of modern Japan. The perpendicular line formed by the roof of the stadium (), if followed in the direction of its neighbour, divides Meiji Shrine into two perfectly symmetrical parts. Connecting the sporting ‘gods’ of the stadium to the deified emperor, this symbolism is married to an architectural, territorial and historical continuity that is particularly vivid here. The dialogue between the park, the urban environment, the gymnasium and Meiji Shrine forges a close link between the site of the Games, the recent history of Japan and Shintô (the state religion during the militarist period). This perfectly exploits the genius of place through what Livio Sacchi call an ‘urbanism of situations’.Footnote56

Figure 4. Correspondence lines and territorial dialogue between the Yoyogi Olympic Complex and the Meiji Shrine. Made by the author.

Unlike the 1964 Games, the 2020 Games did not directly initiate major infrastructure projects. There were three construction projects of a more modest size: a portion of an urban highway (the Kanko Nigosen); the expansion of Haneda Airport; and the inauguration of a new station on the Yamanote circular line. The modesty of these development projects can be explained as much by the high level of maturity reached by Tokyo's infrastructure in the 2000s and 2010s on the one hand, as by the promotion of a sustainable development model on the other. This model questioned the need for further construction, necessitating a turn instead to the rehabilitation of existing infrastructure. From the perspective of the Olympic Games, this also led to the valorization of the material heritage of past Olympics.

The section of highway built for the Tokyo 2020 Games is 14km long. It starts in Kanda, bypasses the Imperial Palace, before heading southeast towards Tokyo Bay. As it passes through the dense urban fabric, it moves underground in places, notably in the Toranomon and Shinbashi areas of Minato Ward. Where it re-emerges at Toranomon, the real estate company Mori Biru built the Toranomon Hills complex, a 247m, mixed-used tower complex spread over fifty floors. Its construction illustrates the avenues of opportunity that Olympic development can generate within the fabric of host cities. The expansion of Haneda Airport, which is located in Tokyo Bay, greatly increased the number of international flights landing near the waterfront and the city centre. The new station built along the Yamanote-sen was the first station created since 1971. Named Takanawa Gateway, it was the fulfilment of a campaign promise from former Tokyo Governor Masuzoe Yōichi (2014–2016), the aim being to relieve congestion along the southern approach to Tokyo, in particular Shinagawa. It also provides a service to Haneda Airport and Shinkansen connections between Tokyo and the west of the country. Finally, Olympics-adjacent infrastructure building in the area included the relocation of the Tsukiji fish market to make way for a portion of the urban highway connecting the Olympic village with the centre of Tokyo.

If Tokyo’s development of Olympic infrastructure for 2020 was not as extensive as that of 1940 and 1964, its indirect effect on real estate production and construction in the 2010s was nonetheless particularly strong. That is particularly evident in areas around the athletes’ village in Chuo Ward and also numerous real estate redevelopments Minato-ku. The developments coincided with the construction of multiple residential towers along the waterfront, and a set of mixed-use towers on its reverse side.Footnote57 From the perspective of a financialized urban capitalism, those developments speak to the genesis of something resembling an Olympic spatial fix, or an event fixFootnote58 in the way Harvey uses the notion of ‘spatial fix’ but in the case on an event planning, and not a zoning planning.

What is the legacy of each Olympiad for those that followed?

From Tokyo 1940 to Tokyo 1964

Because of their dimension and mythical image, the 1964 Games had the most significant and visible impact on the urban structure and planning culture of Tokyo. This aura is partially explained by the tabula rasa the city offered at the end of the war, a void that the Games helped to fill. The rupture was only material, however, and a large number of the individuals responsible for Tokyo's development in the 1930s and 1940s ensured a transition during the years of reconstruction. The significance of the generational and cultural gap between the Olympic project of 1940 and that of 1964 is therefore reduced, the most notable difference being that the political regime and related issues had changed. This continuity in terms of skills, representations and human resources explains why the 1964 Games reused some of the principles and ideas of 1940. Another common thread connecting the two projects was the war and other military concerns as a driver for Olympic developments. However, between the two events, the planning perspective had also changed. The Tokyo 1940 project asked if Olympic infrastructure could be built with a view to improving Tokyo's resilience in times of war. Tokyo 1964, on the other hand, asked if Olympic infrastructure building could help Japan recover its sovereignty vis-à-vis the US occupation of the territory, particularly within the Cold War context in East Asia.

From a more urban perspective, although the preceding 1940 Olympic project largely explains the spatialization of the Tokyo 1964 Olympic infrastructure project, there are nevertheless some modifications between the two Olympiads. The site of the Olympic stadium was transferred from Komazawa in 1940 to Meiji in 1964, removing it from a suburban location to a more central location. This was likely due to the weakening of the Tokyu railway company (which was partially dismantled by the US occupying forces at the end of the war). For similar reasons, the athletes’ village moved from Komazawa in 1940 to Jingu (Yoyogi, Shibuya Ward) in 1964, a site laden with military associations. Therefore, the heart of the 1940 project, planned in Komazawa, was transferred to Shibuya for the Tokyo 1964 project, where it served as a cultural and creative catalyst for local industry.

This modification is particularly important. It allows us to take stock of the transformations within internal power relations in Japan. In 1940, the main political relationships were those of the central government and the zaibatsu, in this case the very powerful Tokyu railway company. In 1964, what took precedence was the re-appropriation of land that was (a) occupied by the US military, and (b) close to the national parliament, making it a symbol of national sovereignty. In both cases, the urban form and location of Olympic infrastructure facilities was directly connected to relationships of power, even to the nature of the political regime in place in Japan at the time. However, the ambition of making Tokyo a resilient metropolis in the face of enemy bombing was secondary to the objective of urban control over certain territories, Namely, those occupied by the US since the defeat of 1945, and those located on the advancing frontier of the metropolis. Pericentral urbanization, national retrocession and emancipation were therefore the three principles on which the development plan for the 1964 Olympic project was based.

From Tokyo 1964 to Tokyo 2016 and 2020

The influence of the Tokyo 1964 project in the minds of planning stakeholders as well as in the urban structure of Tokyo in the 2000s and 2010s is such that the 2016 and 2020 projects explicitly refer to it, meaning the general spirit of Tokyo 2016 and Tokyo 2020 resemble one another.

Despite its non-realization, the Tokyo 2016 project had a considerable impact on the urbanization logic of Tokyo in the 2010s on the one hand, and on the development of the 2020 Games on the other. If analysing an Olympic project from an unsuccessful candidacy may seem useless given that it was never carried out, Tokyo 2016 demonstrates that, on the contrary, there is a great deal of interest to be found in such projects for geographers and urban planners. Tokyo 2016 is therefore a key project for at least two reasons. It is first of all responsible for an unprecedented and lasting transformation in Tokyo’s urbanization and Olympic development logics. The ambition of the project was to make the Games an exemplar of sustainable urban planning through its principle of compactness, and also through the Olympic village as a model of sustainability (after the Games, Ariake-Kita district should have become a residential area and a new urban centre on the seafront as provided for in the master urban development plan for the Ariake-Kita district, amended by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government in 2007 to include Tokyo 2016 Olympic Village): ‘the Olympic Village will become an urban residential “solution model” for sustainability’.Footnote59; ‘The Olympic Village will leave a lasting legacy for the citizens of Tokyo and Japan and will be the showcase of sustainability to the wider world.’Footnote60 Tokyo 2016 therefore established the principle of a multi-scalar and transgenerational role for Olympic facilities in Tokyo through the idea of musubi (inter-linkage) – the project’s leitmotif. A knot woven of multicolored threads used to celebrate the birth of a child, the musubi symbol was used in the context of Tokyo 2016 to represent the urban renaissance policy implemented in Tokyo since the turn of the 2000s. It also echoed the slogan ‘Reboot Tokyo’, used during the third campaign of Ishihara Shintarô, Tokyo Governor at the time. With the musubi concept, the 2016 Olympic candidacy was the culmination of more than a decade of intense urban renaissance policy which had led to Tokyo's return to the rank of major international metropolis. It also connected the Games and Tokyo with past eras, including the triumphant 1960s.

The Tokyo 2020 project was partly the result of a deep impression left in the city by the unrealized 2016 project. However, despite their similarity, the two projects also exhibited notable differences, primarily the location of the Olympic stadium. Planned on the waterfront for the 2016 project, it would have sat at the intersection of the so-called Heritage and Tokyo Bay zones, highlighting the notion of musubi (multidimensional inter-linkage) central to the project’s design. However, Tokyo 2020 moved the stadium to what was the site of the 1964 Olympic stadium at the heart of the Heritage Zone, the original 1964 stadium demolished to make way for Kengo Kuma’s 2020 stadium. This modification reinforces the symbolic relationship between 1964 and 2020. In this case, the continuity is more situational or relational than physical, and in a sense more temporal than spatial. It resonates with Livio Sacchi's analysis of architecture and urban planning, of which Tokyo is the main modern paradigm. Other facilities from 1964 were, however, either kept and simply rehabilitated, or modernized, as was the case with the Nippon Budôkan martial arts centre. In doing so, Tokyo 2020 borrows more from Tokyo 1964 than the Tokyo 2016 project did, even though the latter sought to promote the notion of inter-linkage (musubi) which is as much spatial as temporal and generational. Abandoned for the 2020 project, the musubi spirit was reinforced in a more temporal – rather than spatial – dimension via the placement of Olympic infrastructure. Disappearing from the project literature, the concept of musubi is nonetheless reinforced by the materiality and territorialization of Tokyo’s 2020 Olympic facilities.

Finally, despite the influence of Tokyo 1964 on Tokyo 2016 and Tokyo 2020, the urbanization dynamics driven or reinforced by the 1964 Games and those of 2020 are, however, opposed. The 1964 developments all reinforced the urbanization of western Tokyo, with the establishment of Shibuya as a major urban centre. For its part, Tokyo 2020 accompanied the reversal of the urbanization frontier as it moved towards the waterfront, strengthening the polarity of reclaimed land in Tokyo Bay to the east and Shinagawa to the south. In this sense, it is important to note that the different iterations of the Tokyo Olympic Games did not generate new development dynamics ex nihilo. Rather, they reinforced existing dynamics that, wrapped up in the major planning principles of former Olympic eras, brought together otherwise disparate interests and power dynamics for a one-time meeting of minds on the issue of Tokyo’s urbanization and governance.

Conclusion – towards an urban planning culture through Tokyo’s development of the Olympics

In less than a century, from the 1930s to the 2020s, the relatively small world of Tokyo development stakeholders achieved the considerable feat of formalizing five Olympic projects: the unrealized 1940 Games, the mythical Olympiad of 1964, the postponed 2020 iteration, and the unrealized Games of 1960 and 2016. These projects are representative of four distinct periods in the history of Japan and its capital. As such, they provide insight into not only the nature of the regimes that designed them, but also, when viewed from a longer-term perspective, the evolution of Tokyo’s culture of planning.

If we take GullestrupFootnote61’s definition of culture as a set of values, norms, practices and behaviours that intergenerational transmission gradually transforms, and that of Knieling and OrthengrafenFootnote62 which applies to the field of planning, it is evident that the pomp and scale of planning for the 1964 Games helped to shape the development of a planning culture in Tokyo. The precedent of the 1964 Games not only helps explain the development dynamics of the Japanese capital, but its reactivated presence can also be felt in the 2020 Olympic project itself. However, it should be noted that the generational leap between 1964 and 2020 is so large that it jeopardizes any sense of direct legacy, instead rather favouring a refoundation narrative. This generational leap between 1964 and 2020 is almost three times as significant as the leap between 1940 and 1964. Therefore, rather than identifying the 1964 Games as the founding project for Olympic planning culture in Tokyo, should that distinction not go instead to the 1940 Olympic project?

Focused on the modernization of Tokyo, the 1964 Games project drew to a close a particularly troubled period in Japan's recent history and heralded the advent of the modern capital. Its legacy continues to inform planners’ imaginations and the fabric of urban spaces half a century later. However, from a planning perspective, the break with both the Taisho era and the pre-war period remains blurred. A significant part of the projects carried out for the 1964 session were directly inherited from the development plans formalized in the 1930s for the 1940 Games. Although ultimately cancelled due to the Sino-Japanese War/WWII, the influence of these developments on the planning logic of post-war Tokyo requires further analysis. That is particularly so given their partial reuse in the 1964 Olympic project, which continued into the 2020 project, where there were explicitly highlighted. The same goes for the ultimately unrealized 2016 Games, the weight of which needs to be reassessed.

From a geo-historical perspective, the planning culture established in Tokyo at the turn of the 1960s via Olympic planning was inherited from the 1940 Games. However, it is difficult to determine how long after the 1964 Games that planning culture continued to exert a structural influence over the growth and evolution of Tokyo. If it was partly reactivated in the unrealized 2016 Olympic project, and again in 2020 via the establishment of an explicitly identified ‘Heritage Zone’, it is more as a symbolic form of this narrative, rather than a substantive element of planning practice. However, the narrative does indeed seem to have been effective enough to fire the imagination of developers, as evidenced in the choice of location for the 2020 Olympic stadium.

Although the generational transmission between 1964 and 2020 was indirect, it is still possible to establish certain continuities between 1940, 1964 and 2020. Here the 1964 Olympics acts as a nexus marking the development of Tokyo from, first, a material viewpoint given its spatial structure, and second, an immaterial viewpoint that understands this culture in a broader sense. However, more in-depth work on the individual trajectories and interpersonal relationships of the players involved in planning is necessary for a more in-depth understanding of the survival and evolution of a planning culture in Tokyo shaped by almost a century of Olympism.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the research institutions which have financed his work since 2015, in particular the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Sciences, the FMHS, the EFEO, the Centre for Olympic Studies, the Swiss government and the French Institute for Research on Japan at the Maison franco-japonaise. He also thanks Professor Hosono Sukehiro, from Chuo University, and Professor Laurent Matthey, from the University of Geneva, for their support.

Disclosure statement

The article is the result of several programmes and years of research, started in 2009 during Tokyo's bid phase for the 2016 Games and consolidated thanks to funding obtained by the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Sciences in 2015–2016, the Advanced Olympic Research Grant from the Olympic Studies Centre in 2016–2017, and funding from the Fondation Maison des Sciences de l'Homme, obtained in 2017 in partnership with the Ecole Française d'Extrême Orient de Tokyo.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Raphaël Languillon-Aussel

Raphaël Languillon-Aussel is a Researcher at the French Research Institute on Japan (IFRJ-MFJ) in Tokyo and Associate Researcher at the University of Geneva where he was a lecturer for four years. Holding a doctorate in planning, he conducts work on the relationships between planning dynamics, types of policy regimes and the development of capital regimes. He has been working on Olympics since the failed Tokyo BID for the 2016 Olympics. Former fellow of the IOC Olympic Studies Centre in 2017, he published several reports and academic papers on Tokyo Olympics.

Notes

1 Gold and Gold, Olympic Cities, City Agendas, Planning.

2 Vanwynsberghe, “The Olympic Games Impact (OGI) Study.”

3 See for example Chalkley and Essex, “Urban Development Through Hosting International Events”; Hiller, “Post-Event Outcomes and the Post-Modern Turn”; Smith, “Urban Regeneration.”

4 Garcia-Ramon and Albet, “Pre-Olympic and Post-Olympic Barcelona.”

5 Gold, “Athens 2004.”

6 Broudehoux, “Spectacular Beijing.”

7 Evans, London’s Olympic Legacy.

8 Machemehl and Robène, “L'olympisme et la ville. De la candidature à l'héritage.”

9 See for example Brunet, “An Economic Analysis of the Barcelona”; Garcia-Ramon and Albert, “Pre-Olympic and Post-Olympic Barcelona.”

10 Harvey, “From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism”; Zukin, Landscape of Power.

11 See Chalkley and Essex, “Urban Development Through Hosting International Events”; Davis, “Sport and Economic Regeneration.”

12 Preuss, The Economics of Staging the Olympics.

13 Hannigan, Fantasy City; Gravari-Barbas, “La 'ville festive' ou construire la ville.”

14 Languillon, “De la renaissance urbaine des années 2000.”

15 Augustin and Gillon, L’Olympisme, bilan et enjeux géopolitiques.

16 Horne and Manzenreiter, Sports Mega-Events, Social Scientific Analyses; Short, “Globalization, Cities and the Summer Olympics.”

17 Hannigan, Fantasy City.

18 Gravari-Barbas, “La 'ville festive' ou construire la ville.”

19 Hiller, “Post-Event Outcomes and the Post-Modern Turn”; Preuss, “Olympic Finance.”

20 Broudehoux, “Spectacular Beijing.”

21 Aoyama, “Tokyo 2020”; Languillon, “De la renaissance urbaine des années 2000.”

22 See for example Borja, “Barcelone ou les effets pervers de la réussite”; Preuss, “Olympic Finance.”; Cashman, The Bitter-Sweet Awakening; Evans, London’s Olympic Legacy.

23 Lefebvre and Roult, “L’après JO. Reconversion et réutilisation des équipements olympiques”; Minnaert, “An Olympic Legacy for All?”

24 On this subject, the International Olympic Committee replaced “impact assessment” with “legacy frameworks” at the end of the 2010s.

25 Evans, London’s Olympic Legacy; Attali, “Les défis de l’héritage des Jeux olympiques”; Loudcher, Suchet and Soulier, Héritage olympiques et patrimoine des événements sportifs.

26 Evans, London’s Olympic Legacy.

27 Girginoy, Rethinking Olympic Legacy.

28 Attali, “Les défis de l’héritage des Jeux olympiques.”

29 Shimizu, Olympic Studies.

30 Ishizaka and Matsubayashi, Orinpikku no isan no shakai-gaku; Featherstone and Tamari, “Olympic Games in Japan and East Asia.”

31 Collins, The 1940 Tokyo Games.

32 Ikeda, “The Tokyo Olympics: 1940/2020”; Weber, “Tokyo’s 1940 ‘Phantom Olympics’ in Public Memory.”

33 Saiga, “Olympic Tokyo Taikai no shisetsu keikaku ni tsuite”; Azuma, Olympic.

34 Ishii, 1964 nen no Tokyo Orinpikku.

35 Yoshimi, “1964 Tokyo Olympics as Post-War Games.”

36 Katagi, Olympic City Tokyo 1940/1964.

37 Hashimoto, Maboroshi no Tokyo Orinpikku.

38 See for example Mano, Kiseki no 3-nen 2019 2020 2021 gōruden supōtsuiyāzu ga chihō o kaeru.

39 Ogasawara, Han Tōkyō orinpikku sengen.

40 Languillon, “The Postponed Tokyo 2020 Games.”

41 Appert and Languillon, Impacts des jeux olympiques sur la recomposition; Languillon, “De la renaissance urbaine des années 2000”; Aramata, Political Economy of the Tokyo Olympics.

42 Friedman, “Globalization and the Emerging Culture of Planning.”

43 Knieling and Othengrafen, “Planning Culture.”

44 Dethier, “Le rôle de la culture dans l'aménagement du territoire.”

45 Sanyal, Comparative Planning Cultures, 21.

46 de Vries, “Planning and Culture Unfolded.”

47 Gullestrup, Cultural Analysis.

48 Knieling and Othengrafen, “Planning Culture.”

49 Boltanski, “Preface,” 11.

50 Kubo, “Les cités-jardins au Japon.”

51 The hyper-centre of Tokyo is usually defined as the area encompassed by the JR Yamanote-sen rail loop.

52 Languillon, “The Postponed Tokyo 2020 Games.”

53 Yoshimi, “1964 Tokyo Olympics as Post-War Games.”

54 Languillon, “De la renaissance urbaine des années 2000.”

55 Tolic, Tange Kenzo.

56 Sacchi, Architecture et urbanisme.

57 Appert and Languillon, Impacts des jeux olympiques sur la recomposition.

58 Languillon, “De la renaissance urbaine des années 2000.”

59 Tokyo 2016 BID book, vol. 2, 202.

60 Ibid., vol. 2, 204.

61 Gullestrup, Cultural Analysis.

62 Knieling and Othengrafen, “Planning Culture.”

Bibliography

- Aoyama, Yasushi. “Tokyo 2020.” In Olympic Cities, City Agendas, Planning and the World’s Games, 1896–2012, edited by Gold John and Gold Margaret, 424–437. New York: Routledge, 2017.

- Appert, Manuel, and Raphaël Languillon. Impacts des jeux olympiques sur la recomposition des marchés immobiliers matures: le cas de Tokyo à travers ses comparaisons internationales [Impacts of the Olympic Games on the Reorganization of Mature Real Estate Markets: The Case of Tokyo Through Its International Comparisons]. Report of the Advanced Olympic Research Grants, Olympic World Library, 2017. https://library.olympic.org/Default/doc/SYRACUSE/171060/impact-des-jeux-olympiques-sur-la-recomposition-des-societes-matures-le-cas-de-tokyo-a-travers-ses-c.

- Aramata, Miyo. Political Economy of the Tokyo Olympics Unrestrained Capital and Development Without Sustainable Principles. Tokyo: Routledge, 2023.

- Attali, Michaël. “Les défis de l’héritage des Jeux olympiques et paralympiques. De la croyance aux possibilités” [Olympic and Paralympic games’ legacy issues. From belief to possibilities]. Revue Internationale et Stratégique 114, no. 2 (2019): 127–137.

- Augustin, Jean-Pierre, and Pascal Gillon. L’Olympisme, bilan et enjeux géopolitiques [Olympism, assessment and geopolitical issues]. Paris: Armand Colin, 2004.

- Azuma, Ryutaro. Olympic. Tokyo: Waseda Shobo, 1962.

- Boltanski, Luc. “Preface.” In Introduction à la sociologie pragmatique [Introduction to pragmatic sociology], edited by Nachi Mohamed, 9–16. Paris: Armand Colin, 2006.

- Borja, Jordi. “Barcelone ou les Effets Pervers de la Réussite” [Barcelona or the perverse effects of success]. Revue Urbanisme 331 (2003): 23–24.

- Broudehoux, Anne-Marie. “Spectacular Beijing: The Conspicuous Construction of an Olympic Metropolis.” Journal of Urban Affairs 29, no. 4 (2007): 383–399.

- Brunet, Ferran. “An Economic Analysis of the Barcelona 92 Olympic Games: Resources, Financing, and Impact.” In The Keys to Success: The Social, Sporting, Economic and Communications Impact of Barcelona’92, edited by de Moragas Miquel and Botella Miquel, 203–237. Barcelona: Autonomous University of Barcelona, 1995.

- Cashman, Richard. The Bitter-Sweet Awakening: The Legacy of the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games. Sydney: Walla Walla Press, 2006.

- Chalkley, Brian, and Stephen Essex. “Urban Development Through Hosting International Events: A History of the Olympic Games.” Planning Perspectives 14 (1999): 369–394.

- Collins, Sandra. The 1940 Tokyo Games: The Missing Olympics: Japan, the Asian Olympics and the Olympic Movement. New York: Routledge, 2008.

- Davis, Larissa. “Sport and Economic Regeneration: A Winning Combination?” Sport in Society 13, no. 10 (2010): 1438–1457.

- de Vries, Jochem. “Planning and Culture Unfolded: The Cases of Flanders and the Netherlands.” European Planning Studies 23, no. 11 (2015): 2148–2164.

- Dethier, Perrine. “Le rôle de la culture dans l'aménagement du territoire vis-à-vis des attitudes en faveur de l'auto-gouvernance” [The role of culture in territorial planning vis-à-vis attitudes in favor of self-governance]. PhD thesis, University of Liège, 2019.

- Evans, Graeme. London’s Olympic Legacy. The Inside Track. London: Springer, 2016.

- Featherstone, Mike, and Tomoko Tamari. “Olympic Games in Japan and East Asia: Images and Legacies.” International Journal of Japanese Sociology 28, no. 1 (2019): 3–10.

- Friedmann, John. “Globalization and the Emerging Culture of Planning.” Progress in Planning 64, no. 3 (2005): 183–234.

- Garcia-Ramon, Maria-Dolors, and Abel Albet. “Pre-Olympic and Post-Olympic Barcelona, a Model for Urban Regeneration Today?” Environment and Planning 32, no. 8 (2000): 1331–1334.

- Girginov, Vassil. Rethinking Olympic Legacy. London: Routledge, 2018.

- Gravari-Barbas, Maria. “La ‘ville festive’ ou construire la ville contemporaine par l'événement.” Bulletin de l'Association de Géographes Français 86, no. 3 (2009): 279–290.

- Gold, John, and Margaret Gold. Olympic Cities, City Agendas, Planning and the World’s Games, 1896–2012. 3rd ed. New York: Routledge, 2017.

- Gold, Margaret. “Athens 2004.” In Olympic Cities, City Agendas, Planning and the World’s Games, 1896–2012, edited by J. Gold and M. Gold, 315–339. New York: Routledge, 2017.

- Gullestrup, Hans. Cultural Analysis: Towards Cross-Cultural Understanding. Aalbrorg: Aalbrorg University Press, 2006.

- Hannigan, John. Fantasy City. Pleasure and Profit in the Postmodern Metropolis. New York: Routledge, 1998.

- Harvey, David. “From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism: The Transformation in Urban Governance in Late Capitalism.” Geografiska Annaler. Series B: Human Geography 71, no. 1 (1989): 3–17.

- Hashimoto, Kazuo. Maboroshi no Tokyo Orinpikku [The phantom Tokyo Olympics]. Tokyo: Kodansha, 2014.

- Hiller, Harry. “Post-Event Outcomes and the Post-Modern Turn: The Olympics and Urban Transformations.” European Sport Management Quarterly 6, no. 4 (2006): 317–332.

- Horne, John, and Wolfram Manzenreiter. Sports Mega-Events, Social Scientific Analyses of a Global Phenomenon. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2006.

- Ikeda, Asato. “The Tokyo Olympics: 1940/2020.” The Asia-Pacific Journal 18 (2020). https://apjjf.org/2020/4/ikeda.

- Ishii, Masami. 1964 nen no Tokyo Orinpikku [1964 Tokyo Olympics]. Tokyo: Kawadeshobo-shinsha, 2014.

- Ishizaka, Tomoji, and Hideki Matsubayashi. Orinpikku no isan no shakai-gaku: Nagano orinpikku to sonogo no tōnen [Sociology of Olympic heritage: The Nagano Olympics and the decades afterward]. Tokyo: Seikyu-sha, 2013.

- Katagi, Atsushi. Olympic City Tokyo 1940/1964. Tokyo: Kawadeshobo-shinsha, 2010.

- Knieling, Joerg, and Frank Othengrafen. “Planning Culture. A Concept to Explain the Evolution of Planning Policies and Processes in Europe?” European Planning Studies 23, no. 11 (2015): 2133–2147.

- Kubo, Tomoko. “Les cités-jardins au Japon: entre urbanisme occidental et hybridation locale” [Garden cities in Japan: Between Western urban planning and local hybridization]. Géoconfluences (2017). http://geoconfluences.ens-lyon.fr/informations-scientifiques/dossiers-regionaux/japon/corpus-documentaires/cites-jardins.

- Languillon, Raphaël. “De la renaissance urbaine des années 2000 aux Jeux Olympiques de 2020: retour sur vingt ans d’intense spatial fix à Tokyo” [From the urban renaissance of the 2000s to the 2020 Olympic Games: A look back at twenty years of intense spatial fixation in Tokyo]. Ebisu 55 (2018): 25–58. https://journals.openedition.org/ebisu/2324.

- Languillon, Raphaël. “The Postponed Tokyo 2020 Games: From Planning Conflicts to Covid.” Metropolitics (2022). https://metropolitics.org/The-Postponed-Tokyo-2020-Games-From-Planning-Conflicts-to-Covid.html.

- Lefebvre, Sylvain, and Romain Roult. “L’après JO. Reconversion et réutilisation des équipements olympiques” [After the Olympics. Reconversion and reuse of Olympic equipment]. Revue Espaces 263 (2008): 30–42.

- Loudcher, Jean-François, André Suchet, and Pauline Soulier. Héritage olympiques et patrimoine des événements sportifs: promesses, mémoire et enjeux [Olympic heritage and heritage of sporting events: Promises, memory and challenges]. Montpellier: Presses universitaires de la Méditerranée, 2023.

- Machemehl, Charly, and Luc Robène. “L'olympisme et la ville. De la candidature à l'héritage.” Staps 105, no. 3 (2014): 9–21.

- Mano, Yoshiyuki. Kiseki no 3-nen 2019 2020 2021 gōruden supōtsuiyāzu ga chihō o kaeru [Three miraculous years 2019, 2020, 2021 golden sports years will change the region]. Tokyo: Tokumashoten, 2015.

- Minnaert, Lynn. “An Olympic Legacy for All? The Non-Infrastructural Outcomes of the Olympic Games for Socially Excluded Groups (Atlanta 1996–Beijing 2008).” Tourism Management 33, no. 2 (2012): 361–370.

- Ogasawara, Hiroki. Han Tōkyō orinpikku sengen [Anti-Tokyo Olympics declaration]. Tokyo: Kō Shitausha, 2016.

- Organizing Committee. Report of the Organizing Committee on its work for the XIIth Olympic Games of 1940 in Tokyo until the relinquishment, 1940. https://digital.la84.org/digital/collection/p17103coll8/id/14513/rec/18.

- Organizing Committee. Games of the XVIII Olympiad, Tokyo 1964: The Official Report of the Organizing Committee. 1964. https://digital.la84.org/digital/collection/p17103coll8/id/27247/rec/31.

- Preuss, Holger. “Olympic Finance.” In Olympic Cities, City Agendas, Planning and the World’s Games, 1896–2012, edited by J. Gold and M. Gold, 139–160. New York: Routledge, 2017.

- Preuss, Holger. The Economics of Staging the Olympics. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2004.

- Sacchi, Livio. Tokyo: Architecture et urbanisme [Tokyo: Architecture and Urbanism]. Paris: Flammarion, 2005.

- Saiga, Izumi. “Olympic Tokyo Taikai no shisetsu keikaku ni tsuite” [Regarding facility planning for the Tokyo Olympics].” Shintoshi 14 (1960): 16.

- Sanyal, Bishwapriya. Comparative Planning Cultures. Oxon: Routledge, 2005.

- Shimizu, Satoshi. Olympic Studies. Tokyo: Serica Shobo, 2004.

- Short, John R. “Globalization, Cities and the Summer Olympics.” City 12, no. 3 (2008): 321–340.

- Smith, Andrew. “Urban Regeneration.” In Olympic Cities, City Agendas, Planning and the World’s Games, 1896–2012, edited by J. Gold and M. Gold, 217–228. New York: Routledge, 2017.

- Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Tokyo 2016 (BID Book), Vols. 1, 2 and 3, 2006.

- Tolic, Inès. Tange Kenzo. Milan: Motta Architettura, 2009.

- Vanwynsberghe, Robert. “The Olympic Games Impact (OGI) Study for the 2010 Winter Olympic Games: Strategies for Evaluating Sport Mega-Events’ Contribution to Sustainability.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 7, no. 1 (2015): 1–18.

- Weber, Torsten. “Tokyo’s 1940 ‘Phantom Olympics’ in Public Memory. When Japan Chose War Over the Olympics.” In Japan Through the Lens of the Tokyo Olympics, edited by Barbara Holthus, Isaac Gagné, Wolfram Manzenreiter, and Franz Waldenberger, 66–72. London: Routledge, 2020.

- Yoshimi, Shunya. “1964 Tokyo Olympics as Post-War Games.” International Journal of Japanese Sociology 28, no. 1 (2019): 80–95.

- Zukin, Sharon. Landscape of Power: From Detroit to Disney World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.