ABSTRACT

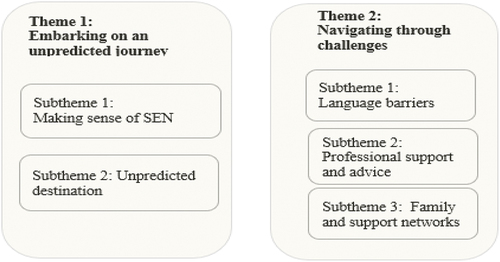

Parenting a child with Special Educational Needs (SEN) presents numerous challenges for families. For immigrant parents, these challenges can be particularly difficult to overcome when faced with structural, cultural and linguistic barriers. This qualitative study explored the lived experiences of eight Eastern European immigrants parenting a child with SEN in England. Semi-structured interviews were conducted, and a data-driven thematic analysis of a series of interviews was carried out. The study identified two key themes: (a) embarking on an unpredicted journey and (b) navigating through challenges. The analyses highlight discrepancies in partnership working between parents and educators and shortcomings in advice that professionals provided to these parents, potentially placing pupils and their families at a disadvantage. The implications for educational psychologists (EPs) and other professionals working with Eastern European parents raising a child with SEN are also discussed.

Introduction

In 2004, the European Union (EU) saw the single largest expansion in the union’s history where eight Eastern European countries (Poland, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Slovakia, Lithuania, Estonia, Hungary and Latvia) joined the EU (Sturge, Citation2018). These countries have been grouped and are widely referred to as the Accession Eight (A8). Since then, more than 2 million A8 citizens have made the United Kingdom (UK) their home (Sturge, Citation2018). In England, over 21% of primary school pupils have English as an Additional Language (EAL), and 14% of all children are identified as having special educational needs (SEN) (Department for Education, DfE, Citation2021). Pupils from minority groups are twice as likely to be diagnosed as having SEN than monolingual children (Strand & Lindorff, Citation2021). Despite the high prevalence of SEN, minority ethnic groups and immigrants are underrepresented in accessing support (Mestry & Grobler, Citation2007). Parenting a child with SEN presents numerous and distinctive psychological, social and administrative challenges to caregivers (DePape & Lindsay, Citation2015).

For immigrant parents, raising a child with SEN can be particularly complex, especially when they have limited knowledge of the language and the host country’s education system (Shah et al., Citation2004; Theara & Abbott, Citation2015). Such difficulties can have multiple implications for the quality of care and educational support they provide to their children (Siddiqua & Janus, Citation2017). The published literature highlights how minority groups are reluctant to seek help, even when support is offered (Manzoni & Rolfe, Citation2019; Mestry & Grobler, Citation2007; Shah et al., Citation2004). Therefore, it is essential to understand the A8 parents’ experiences of raising a child with SEN in the UK in order to provide targeted support that considers the socio-cultural and socio-economic factors.

Typically, research has examined the education of pupils from immigrant backgrounds and the education of pupils with SEN separately (Soriano et al., Citation2009). This study combined these two key factors by applying Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979, Citation2005) bioecological system theory, which was considered as the most appropriate model to capture the complexity of immigration and SEN education. Bronfenbrenner highlights the significance of expected and unexpected events and the impact these can have on an individual’s life and, as such, has been viewed as a suitable lens to explore the parents’ experiences dealing with life challenges such as SEN diagnosis, seeking support and interventions, and making educational choices for their children (Swick & Williams, Citation2006).

According to Bronfenbrenner, individuals can be perceived as being rooted in multiple dynamic nested systems of relationships. Starting from the school and family influences, the Microsystem, which consists of the child’s most immediate environment (psychological, social, and physical), offers a reference point of the world through those earliest encounters. The Mesosystem, which has the power of connecting two or more systems in which the child and family live, permeates every dimension; here, one will find the interaction between family, school, community and specialist professional services (for example, educational psychologist and speech and language therapist). The quality of the interactions (the Mesosystem) between families and professionals are significant factors in the child’s development and parents’ capacity to effectively contribute to their children’s learning (Desforges & Abouchaar, Citation2003). The Exo-system, though not directly linked to the learner’s immediate environment, still impacts on the learner’s experience of education due to school policies, values and ideologies, leadership structures, support structures and allocation of resources. The Macrosystem that exists outside the child’s physical environment influences the central systems, such as the curriculum, political, social, global, and historical factors that affect the learner (Hornby & Blackwell, Citation2018). The Chrono-system is made up of environmental transitions and events that influence the surrounding levels. For Accession Eight (A8) parents, going through the process of SEN diagnosis and navigating through an unfamiliar education system is a non-ordinary event that can present psychological, social and administrative challenges in all levels of this complex bioecological system (Hornby & Blackwell, Citation2018).

SEN in immigrant families

A review of available literature into immigrant parents’ experiences of raising children with SEN found very little relevant published research in this area. Due to the lack of central policy or guidance in the UK for how EAL learners’ (including those with SEN) needs should be addressed, there is significant variation in practices and the resources available between schools (Hughes, Citation2021). The importance of maintaining children’s home language is not always embraced (Howard et al., Citation2021; Hughes, Citation2021; Suárez-Orozco et al., Citation2011). A recent study found that, in England, practitioners viewed the school setting as an ‘English only’ environment and that they were not expected to devote curriculum time or resources to maintaining or developing children’s home language (Howard et al., Citation2021; Snell & Cushing, Citation2022). In a study that involved 15 schools across the UK, Manzoni and Rolfe (Citation2019) found that school staff were mostly positive about the contribution that immigrant children can bring, such as exposing pupils and staff to different cultures and languages. However, the lack of knowledge amongst school staff about immigrant pupils and their families hindered the development of empowering partnerships and potentially placed pupils at a disadvantage (Howard et al., Citation2021; Manzoni & Rolfe, Citation2019).

The challenges that a child with SEN and EAL face in education are not ordinary (Swick & Williams, Citation2006). Due to the complexity, there is a lack of resources available to schools to assess EAL learners in both their first language and in English (Niolaki et al., Citation2021). Using psychometric instruments in a non-dominant language can result in misdiagnosis and gives an inaccurate representation of the children’s linguistic ability, risking labelling them inappropriately as SEN (Marinis et al., Citation2017). Due to the shortage of practical tools to identify language difficulties, it is hard to ascertain whether the difficulty is due to the lack of exposure to the English language or due to a genuine cognitive difficulty (Niolaki et al., Citation2021). Tan et al. (Citation2017) explored the assessment and pedagogy of EAL learners with SEN, and found inconsistency within assessment and teaching strategies. Recently, Howard et al. (Citation2021) highlighted that practitioners working with EAL learners with SEN in England lacked the confidence in supporting learners and that the existing training was unsatisfactory. The insufficient training (Nutbrown, Citation2012), shortage of resources and curriculum demands (Flynn, Citation2015) are just some reasons why educators make referrals for SEN diagnosis, often without wide-ranging assessments and evidence. Consequently, the literature highlights disproportional representation in SEN diagnosis where bilingual children are under-diagnosed or over-diagnosed in comparison with monolingual children (Manzoni & Rolfe, Citation2019; Roman-Urrestarazu et al., Citation2021; Strand & Lindorff, Citation2021; Sullivan, Citation2011).

The sensitive nature of immigration complicates the collection of data when SEN pupils enter UK schools (Jørgensen et al., Citation2021). In a qualitative study with 12 special needs coordinators (SENCos) and special needs teachers, Jørgensen et al. (Citation2021) highlighted the complexities of working in the intersection between SEN and immigration. The participants strongly emphasised the importance of communication and culture differences in terms of SEN. All participants highlighted the difficulty they faced in gathering information about the children’s level of first language, medical history, education and intervention records and they emphasised the need for training for schools and organisations working with immigrant families. Similarly, a recent study which looked at practitioners’ perspectives and experiences of working with bilingual pupils with SEN highlighted the importance of partnerships with parents due to cultural and linguistic differences (Howard et al., Citation2021). An additional difficulty derives from the fact that some A8 countries do not start formal schooling until seven years of age (Manzoni & Rolfe, Citation2019). This is very different to the UK where children typically start school during the academic year that they are five-years-olds, and is also a factor that will disadvantage children moving to the UK and entering the education system, again, making the identification of SEN problematic.

Considering that the most commonly identified SEN in EAL learners is speech, language and communication needs (SLCN; DfE, Citation2021), targeted training for educators and other professionals working with EAL families and partnership with parents are essential to identify any SEN and provide tailored support (Hall et al., Citation2012; Liasidou, Citation2013; Tan et al., Citation2017). A strong relationship between parents and schools is beneficial for both parties and facilitates children’s educational success and wellbeing (Ahad et al., Citation2022; Desforges & Abouchaar, Citation2003; Sylva et al., Citation2004). In a longitudinal study that looked at 3,000 children’s progress, Sylva et al. (Citation2004) found that families’ interactions with children at home were much more important than their background. Similarly, Desforges and Abouchaar’s (Citation2003) literature review concluded that family contribution is extremely beneficial across all social classes and ethnic groups.

Acknowledging the importance of working with families, Part 3 of the Children and Families Act (2014) makes it a legal requirement for the local authorities to involve both the families and children themselves in drawing up the Education, Health and Care (EHC) plans. The concept of parents as partners has been firmly embedded in the Special Educational Needs and Disability (SEND) Code of Practice which provides statutory guidance relating to a number of legislations (DfE, Citation2015). The guidance states that partnerships with parents should be established, involving them in planning support and, where appropriate, in reinforcing the provision or contributing to progress at home (DfE, Citation2015, p. 81). Whilst the importance of partnership working is well documented, Goodall and Vorhaus (Citation2011) acknowledge that for parental engagement to be effective, strategies must be tailored to the families’ needs, considering the cultural and socio-economic environment’s perspective as proposed by Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation2005) framework.

Research into parents’ experiences with SEN services in the UK has highlighted many challenges during the assessment of SEN and accessing support (Ahad et al., Citation2022; DePape & Lindsay, Citation2015; Kwan-Tat, Citation2018; Shah et al., Citation2004; Theara & Abbott, Citation2015). As parents come to terms with their child’s SEN, emotions such as fear, anxiety, guilt, anger, grief as well as acceptance and hope are common across most cultures (DePape & Lindsay, Citation2015; Soriano et al., Citation2009). However, the feeling of hope can be complicated to achieve for immigrant parents who may not know where to turn for support, or have not been able to access support from their extended family (Shah et al., Citation2004; Theara & Abbott, Citation2015). Kwan-Tat’s (Citation2018) small scale exploration of the experience of five Sri Lankan parents, parenting a child with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in London, found that parents felt isolated and disempowered to participate and engage with educational and health professionals. Equally, Theara and Abbott’s (Citation2015) study echoed the feeling of isolation, which presented the perceptions of nine South Asian parents’ experiences of parenting a child with ASD in the UK. Similarly, Shah et al. (Citation2004) found that families grieved the absence of normality and were reluctant to access the SEN services available. In contrast, Habib et al.’s (Citation2017) study with eight Pakistani mothers raising a child with SEN in Ireland, found strong connections between mothers and service providers. As Habib et al. (Citation2017) acknowledged, parents in this study were professionals, educated in the UK to at least level 6 (some to doctoral level) and had lived in the UK for more than 10 years. More than half of the mothers in Habib et al.’s (Citation2017) study were married to a medical professional, consequently making them better positioned to support their children.

Although the research into A8 parents’ experience of SEN in the UK is absent, researchers have started making references to the differences between the UK and A8 countries concerning homework (Christie & Szorenyi, Citation2015) and behaviour expectation (Sales et al., Citation2008). Christie and Szorenyi’s (Citation2015) study of relationships between UK and A8 families highlighted that parents said that they experienced communication issues, were left marginalised, and found the UK education system difficult to understand. Other studies have found that the differences in the education systems, where in most of the A8 countries children start compulsory school at the age of seven, have also been found to present challenges for families and children when they move to the UK (Manzoni & Rolfe, Citation2019; Sales et al., Citation2008). The cultural views of SEN and educational opportunities available for children who have SEN also differ between UK and A8 countries and that has been found to be a key factor in why some parents have been reluctant to share their children’s SEN assessments from their country of origin (Manzoni & Rolfe, Citation2019). The gap in literature here has highlighted the necessity to ascertain the A8 parents’ experiences of raising a child with SEN in the UK.

The current study

The study aimed to acknowledge the voices of A8 parents as an underrepresented group in research. Placing the A8 families at the forefront of research allowed them to voice their experiences regarding inclusive education in the UK and share their social, cultural and administrative challenges. Ascertaining parents’ experiences can help professionals working with these families, and future research directions can be identified. The following three questions were examined:

What are the experiences of A8 families during the identification of their children’s SEN?

What are their experiences in accessing support and guidance to meet their children’s needs?

What kind of feelings do parents have about their children’s future educational prospects?

Method

Methodological approach

To investigate the A8 parents’ lived experiences, a phenomenological lifeworld approach with in-depth semi-structured interviews and thematic analysis (TA), was chosen. Semi-structured interviews are one of the most common qualitative data collection methods as they facilitate an open discussion with the participants (Forrester & Sullivan, Citation2018). TA forms the basis of all qualitative analysis that seeks to explore people’s lived experiences. It is the most widely used method of analysis in many disciplines due to its flexibility (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013). TA seeks to identify, analyse, and report patterns and themes representing participants’ subjective experiences (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021). The objective of this is to establish knowledge about parents’ experiences and psychological phenomena through a dialogue with participants and analysis of their accounts. While the hermeneutic-phenomenological epistemology used implies that themes identified describe key lived experiences of these parents, the researchers’ own perception of the phenomena have inevitably played a part in the interpretation (Gair, Citation2012).

Participants

Purposive sampling was used in this study as a critical principle of qualitative research, which involves collecting data only from those who can contribute to this exploration (Coolican, Citation2017; Silverman, Citation2016). The inclusion criteria were as follows: a parent from an A8 country that joined European Union (EU) in 2004; namely, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Slovakia, Lithuania, Estonia, Hungary and Latvia (Sturge, Citation2018); a parent who has been residing in the UK for more than three years; a parent of a child with SEN as defined by the Department of Education (DfE) which states that a child has an SEN if he/she has a learning difficulty or disability which calls for special provision to be made for them (DfE, Citation2015, p. 15).

Participants were recruited through advertising at two different settings in England. No monetary or other forms of rewards were offered. Six mothers and one couple approached the researcher; three participants made contact by phone and five via email. The participants’ occupation and level of education varies, improving the representativeness and validity of the sample ().

Table 1. The demographic details of eight participants.

Procedure

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was sought from and granted by the Coventry University ethics committee. The research fully adhered to the British Psychological Society’s (BPS) Code of Human Research Ethics (British Psychological Society, Citation2014), the General Data Protestation Regulation 2016 (European Parliament and Council of European Union, Citation2016) and the Data Protection Act 2018 (Great Britain, Citation2018). All participants consented to take part in the research.

Data collection and transcription

The interview questions (Appendix 1) were developed for the purpose of this study, and were theory driven. A pilot interview was completed to ascertain the flow and suitability of the questions selected with one A8 mother of an 8-year-old child with ASD. Following the piloted interview, some minor amendments were made to facilitate the interview flow and improve parents’ experiences. It was this amended interview schedule that was used to collect data from the participants in this study. Further questions were derived from the discussion as it was impossible to anticipate the A8 parents’ experiences with SEN in England (Silverman, Citation2016).

Six participants were interviewed individually, and a couple were seen together as requested by the mother of the child as she wanted her husband to help with the translation. All interviews were conducted face-to-face, in a quiet room at a community centre, between July 2019 and October 2019. The duration of the interviews was between 21 minutes and 38 minutes, with an average of 31 minutes. All interviews were conducted in English and were audio recorded and password-protected. No interpreter was required, and the questions were rephrased and simplified when needed. The verbatim transcription commenced following the interview, and the recording was deleted immediately after.

The method of analysis

An inductive data-driven thematic analysis (TA) was employed, which highlighted patterns and themes between participants across the whole dataset (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013). While the interview questions were theory-driven, the study aimed to explore the A8 parents’ experiences and generate meanings from the data in order to identify relationships and patterns. Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006, Citation2021) guide to TA was used and applied to all transcripts as outlined in .

Table 2. The process used to thematically analyse each interview (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2021).

Analysis and discussion

Two key themes that conceptualised and evidenced key concepts of A8 parents’ journey of parenting a child with SEN in England are outlined in .

Theme 1. embarking on an unpredicted journey

Theme one is divided into two subthemes: (a) making sense of SEN, and (b) unpredicted destination.

Subtheme 1: making Sense of SEN

As parents recalled their experiences of first becoming aware of their children’s SEN, they all remarked that they struggled to make sense of the situation. Although two of the parents were aware of their children’s developmental delays beforehand, most of them were first made aware of their children’s SEN when children entered nursery or school. Consistent with the existing literature (Manzoni & Rolfe, Citation2019), their previous experiences in their home country and their perceptions of SEN were echoed in most of the responses. Some viewed SEN as something physically obvious, referring to their children’s appearance and their physical ability:

‘Back home, autistic children do not always go to school … A friend of mine has a girl with autism … she hits, bites people, screams all the time and throws things. My son is not like that’ (Lena).

‘ … everything is SEN here (UK), lots of children learn to talk late … girls are shy and get upset easily, that is normal. She can walk, she can talk … ’ (Anna).

As Lena talked about children with autism in her own country and SEN in the UK, she highlights the culture and educational provision differences between her country and the UK. Due to these differences, she also communicates a sense of fear that a label might deny her son the right to education (Manzoni & Rolfe, Citation2019). Therefore, this highlights the importance of being socially and culturally sensitive during the assessment process (Hornby & Blackwell, Citation2018).

The idea of a label was not received well by some parents. One parent expressed disagreement with the individuals and settings who first made her aware of her child’s SEN:

‘ … he loved numbers and I think because he likes numbers … they (the nursery staff) said “oh he is special, need to have him assessed” … If they talked to him about numbers, I think he would have showed interest in talking and interacting’ (Lena).

This can suggest that Lena felt that the professionals were more concerned with labelling her son than offering strategies to help him. Flynn (Citation2015) highlighted that the lack of resources and insufficient training (Nutbrown, Citation2012) lead some teachers to make referrals for SEN diagnosis.

Other parents disclosed that they felt pressured by professionals to agree to SEN referrals, particularly by the early years’ educators. Whilst many parents revealed that they accepted the advice given and went ahead with the referrals, some parents recalled waiting before pursuing an assessment. One parent communicated a sense of regret for delaying the assessment. It portrayed her as being in denial of her child’s SEN and that changed the dynamics of the partnership (Siddiqua & Janus, Citation2017). The following quote helps to illustrate this:

‘ … it was all about convincing me that my son has SEN … In the end I agreed with the school … I think that was the best thing I did … the focus shifted to talk about what can be done to support my son rather than play the convincing game’ (Beata).

As parents try to make sense of their children’s SEN, in the absence of support, different emotions have left some parents physically and emotionally drained and feelings of helplessness overwhelm them:

‘I just keep stressing and worrying about how to help my daughter … It breaks my heart when I see her sad and do not know what to do’ (Anna).

‘I just do not know what to do, I have tried everything … the rewards and things … it is impossible to keep up’ (Paulina).

Whilst multiple socio-economic and socio-cultural pressures associated with immigration can worsen parents’ emotions, parents from all backgrounds get overwhelmed with mixed feelings as they came to terms with their child’s SEN (DePape & Lindsay, Citation2015; Siddiqua & Janus, Citation2017). For A8 families, further difficulties derive from the difference between the UK educational system and the education system in some A8 countries (Manzoni & Rolfe, Citation2019), and the lack of support from extended family (Theara & Abbott, Citation2015).

Subtheme 2: unpredicted destination

Navigating a pathway that they were not expecting to take presents implications and difficulties for all parents. DePape and Lindsay’s (Citation2015) systematic literature review found that in 27 out of 31 studies they looked at, parents reported challenges in life adjustment following an SEN diagnosis. Most parents emphasised that the plans and the life they envisaged when they left their country for a better life in the UK were altered when they discovered their children’s SEN. Dora’s quote serves to illustrate this experience:

‘I am worried that my son will not do well … if I cannot help him, I feel that I have failed in life … I have given up everything, I was a secondary teacher back home and I came here, and I work in a shop’ (Dora).

The fear of being perceived as a failure was echoed in other parents, not just Dora. Some parents talked about the broader pressure and the difficulty to tell friends and family in their home country about their children’s needs:

‘Oh, my god, (deep breath) that was very difficult … Yes! … when I came to the UK, I thought my son will be going to Oxford University, not to a special school. That was very difficult to tell people’ (Daniela).

Similarly, a father communicated his initial feeling and how he considered a change of family plans as he comes to terms with his son’s ADHD:

‘ … it was so embarrassing to hear that my child is not listening to the teacher … I told him (son) that if he cannot behave, we will have to go home … I could not say my child is naughty … now at least we know he is not naughty’ (Rick).

The socio-cultural pressures and stigma associated with SEN have been observed in other minority groups (Shah et al., Citation2004). Considering that discipline is heavily emphasised in A8 countries (Sales et al., Citation2008), Rick communicates a sense of relief in understanding that his son’s behaviour is governed by his difficulties and not a discipline issue. Mestry and Grobler (Citation2007) argue that some parents view SEN as a negative reflection of themselves.

Though many parents saw the transformation of the life they had previously envisaged in a less favourable light, some saw it as an opportunity for their children as they would not have had the same level of support in their home country:

‘My mum reminds me of how lucky my boy is to have such a good school … it is the best place for my son but is far from the real world, and that still hurts’.

Although Daniela accepts that the special school is the ‘best place’ to meet her son’s needs, the fear of separation from the ‘real world’, her child being segregated and not included in society still troubles her. DePape and Lindsay (Citation2015) have highlighted that many parents from all walks of life grieve the ‘absence of normality’ as they come to terms with their children’s SEN.

Theme 2: navigating through challenges

Theme two is divided into three subthemes: (a) language barriers, (b) professional support and advice (c) family and support networks.

Subtheme 1. language barriers

Reflecting on their first encounters with education settings in the UK, parents recall that the language barriers were a challenge for most of them. Although two participants said that translation services were provided over the phone, others relied heavily on family support. Paulina, who came to the UK after her husband, stated:

‘I was still learning English … I did not know what they were saying, what they wanted me to do. He was in school, and I was at home. I used to say to school to call my husband’ (Paulina).

Similarly, other parents talked about the challenge that their elders faced as they interacted with their grandchildren’s schools:

‘The nursery would call my mother in law and say, “Come and pick him up”. I would be on the phone with the nursery and my mother in law because she did not understand much English. It was very difficult for her’ (Lena).

Language barriers have been largely felt by staff, parents and children due to the shortage of translated materials to support new arrivals (Sales et al., Citation2008). Paulina, for example, who was the latest arrival, highlighted the challenges she and her child faced when she first moved to the UK (Christie & Szorenyi, Citation2015). Most of the parents in this study communicated that challenges related to the English language impacted their elders and their children more than them as individuals. The support that Lena’s mother-in-law could provide was very restricted due to the language barriers (Theara & Abbott, Citation2015).

Subtheme 2: professional support and guidance

All parents talked about their children’s difficulties when they were formally exposed to the English language as they entered pre-school or school. Most parents recalled that educators advised them to talk to their children in English, only to be given conflicting advice when they sought support from other professionals. Some parents recalled that education psychologists and speech and language therapists discussed linguistic choices and advised parents not to mix languages in one sentence. Contradictory advice had confused parents as they saw the educators and other professionals as experts in their field:

“ … the nursery was saying ‘speak English, speak English, speak English’ and speech and language therapist told me to speak our language “ (Lena).

‘When you are a young parent, you think the doctors and teachers know best, but now I think mums know a lot’ (Anna).

Liasidou (Citation2013) advocates that professionals should not advise parents to abandon their home language. However, the educators’ lack of understanding of the importance of home language and curriculum demands could have affected their pedagogy and guidance (Tan et al., Citation2017). The UK government’s strong emphasis on the use of standard English and the use of English language in educational settings could also be a reason why teachers advise parents to speak English (Snell & Cushing, Citation2022). Promisingly, parents reported that as children progressed to primary school and beyond, the advice of which language to use became more consistent as Anna recalled:

‘They (schoolteachers) have told me to keep reading stories in my language and in English … and talk and talk to her so that she can learn more words’.

Still, some parents highlighted the absence of the discussion about linguistic choices when planning intervention support for EAL children with SEN:

‘I do not remember the teacher, or the SENCO talk about what language to use when doing the activities’ (Dora).

Indeed, linguistic or other support and guidance these EAL learners and families received depended greatly on the type of settings and individual professionals. Hughes (Citation2021) found that due to the lack of central policy for how EAL learners’ needs should be addressed, there is significant difference in practices between schools and highlighted the need for clearer guidance. Whilst some of the parents were appreciative of the support educators gave to their children, some were less content with the help and strategies provided:

‘A few times they (pre-school) called me to go and change his nappy … now when my son is at school; the school does everything for him … They are amazing’ (Daniela).

Although educational settings have a legislative duty (Children & Families Act, Citation2014 & Equality Act, Citation2010) to support children who have health needs, Daniela’s quote highlights discrepancies amongst settings (DfE, Citation2015). Similarly, Dora’s quote provides a picture of the varied advice and support:

‘One teacher told me that they are trying to separate my son and his friend because all they do is chat (in-home language) … The key worker was good; she kept sending me things for me to do at home’ (Dora).

In this case, the benefits of home language have not been embraced (Suárez-Orozco et al., Citation2011) and the opportunities to continue developing children’s home language seem to have been missed (Howard et al., Citation2021). These missed opportunities can impact children’s learning as research has found that supporting children’s home language is beneficial for acquiring an additional language, critical thinking, literacy skills and cultural identity (Howard et al., Citation2021; Suárez-Orozco et al., Citation2011). Hughes (Citation2021) stated that the variation in support is largely due to the lack of central policy or guidance for how EAL learners’ needs should be addressed. Snell and Cushing (Citation2022) highlighted the government’s strong emphasis on standard English, and the use of English language in educational settings can present implications for diversity, inclusion and appreciation of other languages. From a parental perspective, Mejía (Citation2016) reported the case of a mother who confessed feelings of sadness when her children did not prefer to speak in her mother tongue.

Subtheme 3: family and support networks

Although the role of extended family and older family members varies across cultures, for A8 families in this study, the absence of grandparents’ contribution has been missed. In contrast, those who had grandparents’ support had high regard and appreciation for their influence and involvement:

‘I have been so blessed to have had my mother-in-law with me; otherwise, I don’t know what I would do … she does everything for my children’ (Lena).

Many parents expressed that they missed the support and access from their elders and wider family. Dora reflects how things would have been different if she had had her mother’s support:

‘My mother is very encouraging … she looks after my nephews back home … If she was with me, she would help look after him; I would spend more time at work’ (Dora).

Similarly, Daniela recalls the difficulties when she had to pick her son up unplanned before her mother came to the UK:

‘I did not know that many people, and it is not like I can call my mum, or my sister to go and get him. They were back home’ (Daniela).

Indeed, research highlights the significance of support that grandparents and extended family provide on the upbringing of children with SEN (Kwan-Tat, Citation2018; Theara & Abbott, Citation2015). At times, the challenges accessing the needed support leave some parents feeling helpless and defeated (Soriano et al., Citation2009). Such feelings can cause substantial distress and have a massive impact on their quality of life and the quality of their children’s upbringing (Kwan-Tat, Citation2018). In spite of this, as the journey continued, many participants gained a better understanding of their children’s needs. They started to accept a new normal, and as a result, they felt more empowered to help their children.

Discussion

This study acknowledged the voices of eight A8 parents as an under-represented group in research. It is a distinctive study, using Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979, Citation2005) bioecological theory, giving them an opportunity to share their experiences with education in the UK. The conceptualisation of the dynamic relationship between objective and subjective experiences permitted putting parents’ concerns at the centre point of this research, examining their feelings, experiences, and perceptions during the non-normative transitions of SEN identification and engagement with education professionals (Bronfenbrenner, Citation2005).

Findings from this study corroborated previous studies on parents’ experiences (Christie & Szorenyi, Citation2015; Kwan-Tat, Citation2018; Sales et al., Citation2008). Many of the themes identified in this study also apply to non-immigrant parents as they embark through the non-normative transitions of SEN diagnoses, learning about their child’s needs, and navigating support (Stephenson et al., Citation2021). Through the SEN identification process, amongst many feelings, relief and grief have been felt by parents of all backgrounds (DePape & Lindsay, Citation2015). There is also the operation of cultural values related to aspiration (from coming to the UK to improve family prospects) turning to shame (related to child’s SEN) or empowerment depending on the received support and family networks.

Similar to A8 parents, research has found that the feeling of devastation stemmed from parents’ shattered dreams about their children’s future, including education, career and family (DePape & Lindsay, Citation2015). On the other hand, an SEN label gave the parents an explanation of the atypical behaviours and a sense of direction of moving forward. Whilst research acknowledges that feeling overwhelmed is a process that all parents experience, it is vital to recognise the multiple socio-economic and socio-cultural challenges that immigrant parents may experience could exacerbate these feelings. A critical example of these challenges felt by most parents in this study was the language barrier. Indeed, other studies have found that language barriers have created additional stress for educational psychologists, parents and children (Christie & Szorenyi, Citation2015; Kwan-Tat, Citation2018), particularly in recent years as thousands of A8 nationals have come to the UK in a relatively short time (Sales et al., Citation2008).

Cline and Frederickson (Citation2009, p. 25) state ‘the definition and explanation of what children and teachers experience as “learning difficulties” became a site for fruitless debates between theorists and practitioners who adopt incompatible terminology to reflect different perspectives and then cannot engage in a meaningful dialogue’. Although those researchers stressed this in 2009, it seems to be a substantial challenge even today; and it seems like an issue that educational psychologists need to combat to gain the most from partnerships with parents. Good communication between home and school is the critical determinant in unlocking learner potential and operates as a protective factor for the child and the family going through diagnosis and trying for the best for their child (Stephenson et al., Citation2021); Snell and Cushing (Citation2022).

A8 parents recalled the advice given regarding their children’s linguistic choices; they highlighted inconsistency in the advice offered by educators and other professionals. This adds to Flynn’s (Citation2015) study, emphasising that the difficulties in assessing children’s learning and the curriculum demands had left teachers imposing guidance and rules on children’s use of the first language. Similarly, Manzoni and Rolfe (Citation2019) found that financial constraints have limited schools’ ability to allocate resources to EAL children, stating that the previous funding method was preferable by some schools as EAL attracted specific funding. This is another example of how decisions made by policymakers at the Exosystem have a massive impact at the Microsystem level and on the quality of the interactions within the Mesosystem (Bronfenbrenner, Citation2005). The figure presented below (), captures what has been learned about the experiences of these parents by locating analysis in summary form against each of the elements of Bronfenbrenner’s model. In that way, the researchers attempted to identify the systemic elements that need to be targeted for change in order to support these families better.

Figure 2. Experiences of these parents against each of the elements of Bronfenbrenner’s model (Bronfenbrenner, Citation2005).

Consistent with Christie and Szorenyi (Citation2015), this study highlights the discrepancy in partnership working and the shortcomings in advice and support provided to parents. These findings of the present study differ from the findings of Habib et al. (Citation2017), which found satisfaction in the support provided and strong partnership between Pakistani mothers and educators. However, the participants’ socio-economic and socio-cultural status differs. Participants in Habib et al.’s (Citation2017) study were UK educated, and many were married to medical professionals; therefore, they were familiar with the education system and were able to pay for private diagnoses and tuition to support their children. Although many of the present study participants were degree graduates from their own country, most of them were not working in the field in which they were trained, and they spoke of the challenges they faced as they navigated the education system.

Similar to Christie and Szorenyi’s (Citation2015) findings, the support depended greatly on educational settings and individual educators. A8 parents were less satisfied with the support from the early years’ settings than from primary schools. An explanation of this may be the difference in the training that the early years’ workforce and the schoolteachers receive (Nutbrown, Citation2012). However, it could also be linked to the parents feeling empowered through knowledge as they better understand their children’s SEN and the education system. This also highlights the need for parents to be encouraged and empowered to collaborate and work with educational psychologists and teaching staff. This is the only way children’s needs can be successfully met and identified, as parents can be empowered only when effective communication is achieved. Educational psychologists can play an active role in ensuring that information is accessible and communicated clearly.

Limitations, implications for EP practice, and conclusion

Limitations

While the findings of this small exploratory study can be informative for future research and for education psychologists, as with any qualitative research, the generalisability of these findings is limited. The description of A8 parents’ experiences with SEN services in England does not represent the experiences of all A8 parents in England or the UK. In an attempt to minimise subjectivity, a rigorous approach of reflexivity was adopted, acknowledging that the researchers’ presumptions and subjectivity can impact each phase of the research process (Gair, Citation2012). However, despite the steps taken to present transparency, researchers with different theoretical viewpoints or experiences might have identified different themes from the same data (Forrester & Sullivan, Citation2018).

Further research concerning A8 immigrant families’ experiences and SEN is required, for example, consider the voices of immigrant children with SEN. Additionally, an interesting avenue for further research would be ascertaining the views of educators and other professionals on the use of the first language, as this study highlighted the inconsistency in the advice provided to parents.

Implications for EP practice

A number of implications for educational psychologists and other relevant professionals arise from the findings of this study. The authors would like to summarise some essential practical and helpful strategies for educational psychologists as these have emerged from the current small-scale study. Educational psychologists need to be aware that the fear of stigma and exclusion may affect A8 parents’ ability to be open about children’s SEN. Therefore, the parents’ views and wishes should be central in the process of SEN assessment. In addition, it is critical to be aware that parents may feel worried or frightened about what their children’s education might be like if they are identified as having SEN. Also, diagnosis with SEN may entail an unexpected entry into an unfamiliar world as there are cultural and educational differences between the UK and A8 countries. This could be reduced by strong partnerships with parents, and frequent meetings where the parents’ and child’s needs and perspectives are taken into account. Desforges and Abouchaar (Citation2003) highlight that the quality of the interactions (the Mesosystem) between families and educational psychologists and teaching staff are significant factors to the child’s development and parents’ capacity to contribute to their children’s learning effectively. Parents can find the experience of interacting with professionals pressurising and daunting; therefore, educational psychologists must be aware of power differences and how A8 parents may view these powers.

The teaching staff working with A8 families and using a multi-disciplinary approach need to ascertain that the advice and support are consistent throughout the schooling system. Educational psychologists should be aware of the complexity of the lives of immigrant parents of SEN children and the lack of supporting networks associated with immigration. Training for all professionals involved in working with immigrant parents and EAL pupils with SEN is also vital, which has also been highlighted by other research (Hall et al., Citation2012; Jørgensen et al., Citation2021; Liasidou, Citation2013; Tan et al., Citation2017).

Finally, it is crucial to develop a central policy of supporting EAL learners (including those with SEN) as this could help reduce the shortcomings and inconsistency in the advice provided to parents by different professionals.

Conclusion

This exploration of A8 parents’ experiences of raising a child with SEN provides professionals, policymakers and service providers with awareness of socio-economic and socio-cultural issues when engaging with this population. These findings are particularly relevant for educational psychologists as they have a crucial role in supporting children with SEN and advising parents and educators. The absence or inadequacies of partnerships between A8 families and educators should be seriously addressed following extensive research highlighting that such partnerships are crucial and key to tackling challenges in progressing education for SEN children (Desforges & Abouchaar, Citation2003; Sylva et al., Citation2004).

The social, cultural and economic dynamics of immigrants are complex and can present a range of challenges for parents who have children with SEN (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979, Citation2005). Parenting a child with SEN in an unknown environment and with limited knowledge of the education system and English language can influence the parental contribution and ability to reach out for support. Therefore, for educational psychologists to provide socio-culturally and socio-economically sensitive support for immigrant families parenting a child with SEN, knowledge of their multilevel challenges is fundamental.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahad, A., Thompson, A. M., & Hall, K. E. (2022). Identifying service users’ experience of the education, health and care plan process: A systematic literature review. Review of Education, 10(1), e3333. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3333

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis. Analysing qualitative data in psychology. Sage Publications Ltd.

- British Psychological Society. (2014). BPS code of human research ethics (2nd ed.). British Psychological Society. https://www.bps.org.uk/news-and-policy/bps-code-human-research-ethics-2nd-edition-2014

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (2005). Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development. Sage.

- Christie, S., & Szorenyi, A. (2015). Theorising the relationship between UK schools and migrant parents of Eastern European origin: The parents’ perspective. The International Journal about Parents in Education, 9(1), 145–156. http://www.ernape.net/ejournal/index.php/IJPE/article/view/316/254

- Cline, T., & Frederickson, N. (2009). Special educational needs, inclusion and diversity. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

- Coolican, H. (2017). Research methods and statistics in psychology. Psychology Press.

- Data Protection Act 2018, c. Retrieved December 2, 2019, from http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2018/12/contents/enacted

- DePape, A. M., & Lindsay, S. (2015). Parents’ experiences of caring for a child with autism spectrum disorder. Qualitative Health Research, 25(4), 569–583. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732314552455

- Desforges, C., & Abouchaar, A. (2003). The impact of parental involvement, parental support and family education on pupil achievement and adjustment: A literature review (Vol. 433). DfES.

- DfE. (2015). SEND Code of Practice 0-25 Years. Department for Education, Department of Health, 2015–229. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/send-code-of-practice-0-to-25

- DfE. (2021). Schools, pupils, and their characteristics: June 2021. Retrieved December 2021, from file://https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-pupils-and-their-characteristics

- European Parliament and Council of European Union. (2016). Regulation (EU) 2016/679. Retrieved December 2, 2019, from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legalcontent/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679&from=EN

- Flynn, J. M. (2015). Teachers’ pedagogic discourses around bilingual children: encounters with difference [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Manchester Metropolitan University.

- Forrester, M. A., & Sullivan, C. (Eds.). (2018). Doing qualitative research in psychology: A practical guide. SAGE Publications Limited.

- Gair, S. (2012). Feeling their stories: Contemplating empathy, insider/outsider positionings, and enriching qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 22(1), 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732311420580

- Goodall, J., & Vorhaus, J. (2011). Review of best practice in parental engagement (Report No. DFE-RR156). Department for Education.

- Habib, S., Prendeville, P., Abdussabur, A., & Kinsella, W. (2017). Pakistani mothers’ experiences of parenting a child with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in Ireland. Educational & Child Psychology, 34(2), 67.

- Hall, D., Griffiths, D., Haslam, L., & Wilkin, Y. (2012). Assessing the needs of bilingual pupils: Living in two languages. Routledge.

- HM Government. (2018). Data Protection Act 2018. legislation.Gov.uk. https://www.lesilation.gov.uk/ukpga/2018/12/contents/enacted

- Hornby, G., & Blackwell, I. (2018). Barriers to parental involvement in education: An update. Educational Review, 70(1), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2018.1388612

- Howard, K. B., Katsos, N., & Gibson, J. L. (2021). Practitioners’ perspectives and experiences of supporting bilingual pupils on the autism spectrum in two linguistically different educational settings. British Educational Research Journal, 47(2), 427–449. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3662

- Hughes, V. (2021). Child migrants’ right to education in a London academy: Tensions between policy, language provision, and international standards. Human Rights Education Review, 4(1), 70–90. https://doi.org/10.7577/hrer.4010

- Jørgensen, C., Dobson, G., & Perry, T. (2021). Supporting migrant children with special educational needs: What information do schools need and how can it be collected? University of Birmingham.

- Kwan-Tat, N. (2018). Social representations and special educational needs: The representations of SEN among Sri Lankan, Tamil families and educational professionals [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University College London.

- Liasidou, A. (2013). Bilingual and special educational needs in inclusive classrooms: Some critical and pedagogical considerations. Support for Learning, 28(1), 11–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12010

- Manzoni, C., & Rolfe, H. (2019). How schools are integrating new migrant pupils and their families. National Institute of Economic and Social Research.

- Marinis, T., Armon-Lotem, S., & Pontikas, G. (2017). Language impairment in bilingual children: State of the art 2017. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 7(3–4), 265–276. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.00001.mar

- Mejía, G. (2016). Language usage and culture maintenance: A study of Spanish-speaking immigrant mothers in Australia. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 37(1), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2015.1029931

- Mestry, R., & Grobler, B. (2007). Collaboration and communication as effective strategies for parent involvement in public schools. Educational Research and Reviews, 2(7), 176.

- Niolaki, G., Terzopoulos, A. R., & Masterson, J. (2021). More than phonics: Visual imagery and flashcard interventions for bilingual learners with spelling difficulties. Patoss Bulletin, 34(2), 14–25.

- Nutbrown, C. (2012). Foundations for quality: The independent review of early education and childcare qualifications. Crown.

- Roman-Urrestarazu, A., van Kessel, R., Allison, C., Matthews, F. E., Brayne, C., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2021). Association of race/ethnicity and social disadvantage with autism prevalence in 7 million school children in England. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(6), e210054–e210054. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.0054

- Sales, R., Ryan, L., Lopez Rodriguez, M., & D’Angelo, A. (2008). Polish Pupils in London Schools: Opportunities and challenges. Social Policy Research Centre Research Report.

- Shah, R., Draycott, S., Wolpert, M., Christie, D., & Stein, S. M. (2004). A comparison of Pakistani and Caucasian mothers’ perceptions of child and adolescent mental health problems. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 9(3), 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363275204047808

- Siddiqua, A., & Janus, M. (2017). Experiences of parents of children with special needs at school entry: A mixed method approach. Child: Care, Health and Development, 43(4), 566–576. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12443

- Silverman, D. (Ed.). (2016). Qualitative research. Sage.

- Snell, J., & Cushing, I. (2022). The (white) ears of Ofsted: A raciolinguistic perspective on the listening practices of the schools inspectorate. Language in Society, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/404522000094

- Soriano, V., Grünberger, A., & Kyriazopoulou, M. (2009). Multicultural Diversity and Special Needs Education. Brussels. Odense: Europian Agency for Development in Special Needs Education.

- Stephenson, J., Browne, L., Carter, M., Clark, T., Costley, D., Martin, J., … Sweller, N. (2021). Facilitators and barriers to inclusion of students with autism spectrum disorder: Parent, teacher, and principal perspectives. Australasian Journal of Special and Inclusive Education, 45(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/jsi.2020.12

- Strand, S., & Lindorff, A. (2021). Ethnic disproportionality in the identification of high-incidence special educational needs: A National Longitudinal Study ages 5 to 11. Exceptional Children, 87(3), 344–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402921990895

- Sturge, G. (2018). Migration statistics. House of Commons Library Briefing Paper, No: SN06077, 1–39.

- Suárez-Orozco, M. M., Darbes, T., Dias, S. I., & Sutin, M. (2011). Migrations and schooling. Annual Review of Anthropology, 40(1), 311–328. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-111009-115928

- Sullivan, A. L. (2011). Disproportionality in special education identification and placement of English language learners. Exceptional Children, 77(3), 317–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291107700304

- Swick, K. J., & Williams, R. D. (2006). An analysis of Bronfenbrenner’s bio-ecological perspective for early childhood educators: Implications for working with families experiencing stress. Early Childhood Education Journal, 33(5), 371–378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-006-0078-y

- Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Taggart, B. (2004). The effective provision of pre-school education (EPPE) project technical paper 12: The final report-effective pre-school education. DfES: Institute of Edcation.

- Tan, A. G. P., Ware, J., & Norwich, B. (2017). Pedagogy for ethnic minority pupils with special educational needs in England: Common yet different? Oxford Review of Education, 43(4), 447–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2017.1331845

- Theara, G., & Abbott, D. (2015). Understanding the experiences of South Asian parents who have a child with autism. Educational & Child Psychology, 32(2), 47–56.

- UK Government. (2010). Equality Act. Equality Act. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents

- UK Government. (2014). Children and Families Act 2014. Legislation.gov.uk. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/06/contents/enacted

Appendix 1

Semi-Structured Interview

These are questions that I intended to ask. Further questions will derive based

on the participants response. These questions may not be asked in this order.

Demographic information will be gathered.

Can you tell me a little bit about your child/children?

What is their specific need?

What was your experience during the early assessment?

What were the biggest challenges?

How has the diagnosis impacted your child’s use of first language?

What has been the advice from professionals?

How supporting have the school/preschool been?

Now that your child is diagnosed, how supported do you feel?

What support (if any) does you and your family receive to help your child?

What support would you like to receive?

How well do you feel your child’s needs are met in school?

What level of support does your child get?

Is there anything that you want to tell me that you think might be important?

Thank the participant and debrief.