ABSTRACT

This mixed-methods study examined educational psychologists’ (EP) experiences of occupational stress, well-being, and implications for their professional practice. Phase 1 involved an online survey of 300 EPs in England using the Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL) and the Short Warwick and Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (SWEMWBS). The findings revealed 78% reported low or moderate compassion satisfaction, defined as the positive emotional fulfilment derived from helping others and making a positive difference; 72% reported moderate or high levels of burnout; and 73 % reported moderate or high levels of secondary traumatic stress. 99% of the participants’ well-being scores fell within the low or medium category. Semi-structured interviews in Phase 2 with 12 EPs revealed risk of burnout, workforce retention challenges, and intensified feelings of autonomy loss and helplessness since the COVID-19 pandemic. Protective factors included connection with colleagues, recognition, shared values, and meaningful impact opportunities. Implications for practice are discussed.

Introduction and literature review

Occupational stress results from conditions within the workplace that can lead to an individual’s perception that they are unable to cope with the demands placed on them (Health and Safety Executive [HSE], Citation2021). It can be associated with experiences of excessive workloads, conflicting expectations, physical and/or emotional changes, or unexpected/unrealistic responsibilities (Van den Broeck et al. Citation2008). This requires individuals to adapt or respond in ways that may exceed their knowledge, skills, or expectations, thereby reducing their ability to cope (Reupert et al., Citation2022). Occupational stress can also be influenced by a perceived lack of workplace support, or lack of control over work processes (Van den Broeck et al., Citation2016); its impact can be observed in a range of domains, including affective (for example, depressed mood, anxiety), cognitive (for example, reduced ability to concentrate or make decisions), physical (for example, poorer health), behavioural (for example, high staff turnover), and motivational (for example, withdrawal, low levels of engagement with others) (Rupert et al., Citation2015).

While identified as a concern in a range of health and social care professions (Sinclair et al., Citation2017), published data on the level and impact of occupational stress in applied psychology professions remains scarce (Berjot et al., Citation2017). An awareness of a potential risk of stress within the educational psychology profession was first raised over two decades ago (Leyden Citation1999), and later a pilot study by Gersch and Teuma (Citation2005) across four local authorities in the UK explored educational psychologists’ perceptions of their own stress levels. Since then, a workforce survey commissioned by the Department for Education (DfE) in 2019 revealed that 79% of EPs found their job stressful, and 43% reported it to be challenging in a negative way (Lyonette et al. Citation2019). In the same study, over two-thirds of the surveyed Principal Educational Psychologists (PEPs) reported difficulties in filling vacant positions, resulting in inadequate staffing to cope with demands. The report also revealed that 93% of Local Authority (LA) PEPs were facing more demand for EP services than they could meet (Lyonette et al., Citation2019).

These studies highlight that understanding factors affecting EP recruitment, retention, and training is crucial due to the potential implications of high turnover and burnout on the profession, and reveal the presence of ongoing stress in educational psychology practice. However, there remains a need to delve deeper into specific stressors, moderators, and outcomes directly from EPs, and an exploration of protective factors is necessary to enhance professional experiences. Since the aforementioned research predates COVID-19, it is relevant to consider the pandemic’s impact on occupational stress levels among EPs.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a major impact on the way the profession functions and on training experiences, with some evidence that this has been negative in part. For example, consultation and therapeutic work moved online, changing almost overnight with little chance to prepare (Reupert et al., Citation2022). Research on video-conferencing suggests that this way of working with technology is relatively new to the field of education in comparison to the medical and business professions (Schaffer et al., Citation2021). This presented applied psychologists with not only practical issues but also some potential ethical and confidentiality concerns, and some psychologists reported feeling de-skilled when trying to meet the demands of online service expectations (Reupert et al., Citation2022). In relation to training, trainee educational psychologists (TEPs) were concerned about the way in which the pandemic was impacting on the development of their placement skills, producing feelings of disconnect and uncertainty over which academic tutors had little control or reassurance (Shield, Citation2023).

The pressure that EPs work under was already well recognised prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to repeated calls for expanding the EP workforce (Association of Educational Psychologists [AEP], Citation2023, Lyonette et al., Citation2019). Recent policy developments, such as the UK Government’s Green Paper and the SEND improvement plan by the Department for Education (DfE), recognised the vital role of EPs in supporting children and young people with SEND (Department for Education [DfE], Citation2023). Despite this recognition, legislative changes and growing demands for statutory work have heightened the profession’s workload further. Therefore, there is an urgent need to fully understand the implications of occupational stress on educational psychology practice in order to protect the workforce and communities they serve from its adverse effects.

Current study aims and research questions

This study aimed to ascertain the different domains and levels of perceived occupational stress and well-being of EPs, exploring more fully how they relate to the EP profession and their implications for practice. These aims were achieved through the following research questions:

RQ1:

To what extent do EPs experience occupational stress?

RQ2:

What are the relationships between compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and well-being among EPs?

RQ3:

What are EPs’ perceptions of the potential stressors involved in their experiences of occupational stress and well-being?

RQ4:

What are EPs’ perceptions of potential moderators involved in their experiences of occupational stress and well-being?

RQ5:

What are the views of EPs on the implications of occupational stress on EP practice?

Methods

Research design

In pursuit of the research objectives, and in accordance with the pragmatism research paradigm, a mixed-methods, explanatory sequential design was employed. This approach encompasses a two-phase methodology. First, a quantitative phase was developed, followed by the design and implementation of a subsequent qualitative phase. The latter phase served the purpose of elucidating and providing a more comprehensive understanding of the quantitative findings (Creswell and Hirose, Citation2019). Carson and Kuipers’ (Citation1998) stress model was employed as a guiding framework for this research. By applying this model, this study aimed to examine the factors influencing the impact of occupational stress on EPs. The theoretical model delineates the stress process into three levels, where the primary objectives are to identify potential stress risk factors, protective factors or buffers, and the resulting effects or implications of stressors on educational psychologists and their professional practices.

Ethics

Ethical approval for this research study was granted by the University of Exeter Ethics committee. This study followed the updated British Psychological Society’s Code of Human Research Ethics (Oates et al., Citation2021).

Participants

In Phase 1, N = 327 participants working in England volunteered to participate in the online survey. The online questionnaire link was distributed to the target population of EPs through the following channels:

• The Association of Educational psychologists (AEP)

• The National Association of Principal Educational psychologists (NAPEP)

• EPNET – an online professional email forum

• edpsy.org.uk – a project page on the online blog space

• Twitter (now known as X) – social media platform

In addition, a generic recruitment email containing a link to the online questionnaire was sent to the researcher’s placement service, whereby some colleagues shared the link with more potential participants by utilising their own contacts. The pre-set inclusion criteria required that the questionnaire be open only to qualified educational psychologists (EPs) in England who were registered with the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC). There were no exclusion criteria based on whether the participants worked for a local authority (LA) or in the private sector.

In Phase 2, data were collected through semi-structured interviews with 12 participants, all working in England. These were selected from a larger number of participants who expressed interest after Phase 1. To increase external validity, purposive sampling was performed to obtain heterogeneity in gender, current role, geographical region, and occupational sector (that is, self employed/local authority [LA]). In order to ensure there was a mix of self employed and LA representation in the sample, this resulted in two out of the three self employed EPs being from the same geographic region. Self employed EPs were harder to recruit in terms of a wider geographical area compared to LA EPs due to more limited ways to reach them. provides a breakdown of the demographic data.

Table 1. Phase 2 demographic data.

Data collection: phase 1

Participants completed an online survey comprising two validated data collection instruments: The Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL) and the Short Warwick and Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (SWEMWBS). These were used to provide robust measures of different dimensions of occupational stress, and of well-being.

The fifth revised version of the ProQOL scale is widely recognised for investigating the professional quality of life of those working within helping professions (Stamm, Citation2010). This scale measures both positive (compassion satisfaction) and negative (compassion fatigue) aspects, including burnout and secondary traumatic stress. As reported in the ProQOL manual, the compassion satisfaction scale has good internal consistency (α = .88), the burnout scale has acceptable internal consistency (α = .75), and the secondary traumatic stress scale has good internal consistency (α = .81) (Stamm, Citation2010).

On each subscale, participants rated 10 self-report statements on a 5-point Likert scale (1-never to 5-very often). Following the scoring methods recommended by the ProQOL manual, raw scores were converted to T-scores for all statistical analyses (M = 50, SD = 10) (Stamm, Citation2010). In addition, selected items from the instrument were individualised for relevance to the target population of this study, as recommended by Stamm (Citation2010). Specifically, the term “helper” was replaced with the term “educational psychologist”.

The Short Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS) (Warwick Medical School, Citation2016) has been found to be more psychometrically robust than the full version (WEMWBS) (Vaingankar et al., Citation2017) and, benefitting from its brevity, has become widely used in well-being studies across the globe. The scale comprises seven positively worded items, with scores ranging from 7 to 35, with higher scores indicating greater mental well-being. Respondents used a 5-point Likert scale to rate each statement. In this study, SWEMWBS raw scores were converted into metric scores using a conversion table (Stewart-Brown and Janmohamed, Citation2008). The SWEMWBS demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .84) (Ng Fat et al., Citation2017). The authors of the measure emphasise that there is currently no established gold standard for assessing high mental well-being, making all score cut points arbitrary (Stewart-Brown and Janmohamed, Citation2008). In this study, the cut points provided in the measure’s guidance were used, and descriptors aligned with previous research utilising the SWEMWBS; however, in some studies, the descriptor “medium” has been used in place of “moderate”.

Data collection: phase 2

The Phase 1 questionnaire findings influenced the design of the Semi-Structured Interviews (SSIs) by incorporating pre-set questions based on the identified factors, such as the workload’s impact on EPs’ occupational stress. Based on these findings, further exploration of EPs’ perceptions of their workloads and contributing factors was pursued. The interview structure was influenced by the hierarchical focused interview technique (Tomlinson, Citation1989) because of its balance of structure and flexibility, effectively addressing research aims while allowing in-depth probing of responses.

Phase 2 research questions centred on EPs’ own experiences and perspectives, guiding the development of interview questions and techniques as well as the analysis approach. Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) highlight two analytical approaches: the theoretical thematic analysis or “top-down” approach, driven by specific research questions or the researcher’s focus, and the inductive “bottom-up” approach, driven by the data itself. In this study, Phase 2 aligned more with the top-down approach, as it was influenced by the research questions and Phase 1 findings.

Data analysis: phase 1

Phase 1 data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 28. Partial responses were removed, resulting in a final sample size of N = 300. Scoring, including reverse-scored items, was performed in Qualtrics before exporting the data to SPSS. The Phase 1 research questions were addressed using descriptive, frequency, and inferential statistics. The data were subjected to a one-way independent ANOVA to examine demographic characteristics, encompassing responses categorised into three or more groups, such as Region, Age Range, and Occupational Position. For demographic characteristics involving only two groups, namely Gender and Occupational Sector, independent t-tests were used for the analysis.

Data analysis: phase 2

The transcribed interviews in Phase 2 were analysed using Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006, Citation2021) thematic analysis framework. Thematic analysis was chosen as it aligned with the research paradigm of the study, allowing for a representative and respectful exploration of participants’ views and experiences. This approach also acknowledged the reflexive influence of the researcher’s interpretations of the data, as highlighted by Braun and Clarke (Citation2021), who state that researchers’ own values, skills, experience, and training can shape the thematic analysis process. By following this framework, the analysis aimed to ensure comprehensive and meaningful insights into the qualitative data collected in Phase 2 (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2021, Briggs, Citation1986).

Phase 1 findings

In Phase 1 of the study, data (N = 300) were collected across England via an online quantitative survey: provides a breakdown of the demographic data.

Table 2. Phase 1 demographic data.

Results across demographic data

The results of the one-way independent ANOVA for each ProQOL subscale and the SWEMWBS showed that there were no statistically significant differences between Region or Gender, and Compassion Satisfaction (CS), Burnout (BO), Secondary Traumatic Stress (STS), and Well-being (SWEMWBS) scores.

The results showed a main effect of age range on CS scores (F (4,295) = 2.71, p < .03, np2 = .04). Tukey HSD post-hoc tests showed that while participants in the 25–34 age range scored lower than all older groups, the difference between the groups did not reach significance.

The results of the one-way independent ANOVA showed that there was a difference of statistical significance observed on CS scores between EPs and SEPs. Main-grade EPs reported less CS (F (2,297) = 6.23, p < .002, np2 = .04).

Participants who worked mainly in the private sector had higher CS scores, lower BO scores, lower STS scores, and higher SWEMWBS scores. An independent t-test for each subscale found this pattern to be significant: CS = t (298) = −3.90, p < .001; BO = t (298) = 4.31, p < .001; SWEMWBS = t (298) = −4.59, p < .001. The difference between the Occupational Sector and STS scores did not reach statistical significance (p > .05).

Results across individual scales

The compassion satisfaction scale in the current study gauges positive emotions related to EPs feeling competent in their work. Higher scores indicate more positive experiences in their job. Overall, 78% of participants scored within the low or moderate range on the CS subscale (34% and 44%, respectively). Certain items received more positive responses, such as over 74% felt that they get satisfaction from being able to help people (44.67% “Often” and 29.67% “Very Often”) and 70% felt happy that they chose to do this work (42.33% “Often” and 27.67% “Very Often”). More negatively, over 67% of participants rarely or only sometimes had thoughts that they are a success as an EP.

The burnout scale captures feelings of hopelessness, ineffective work, lack of impact, and work-related stress or overload. In this study, 72% of the EP sample scored within the moderate or high range on the burnout subscale. Interestingly, some items received more positive responses, with 87.33% (40.33% “Very Often” and 47% “Often”) feeling that they are very caring individuals, while 64% (43.7% “Often” and 20.3% “Very Often”) felt that they have sustaining beliefs. Concerningly, 59.33% felt worn out due to their work as an educational psychologist (31% “Very Often” and 28.33% “Often”) and 31.33% reported this to be the case sometimes. In addition, 68% felt overwhelmed by their seemingly endless workload (39% “Very Often” 29% “Often”) while 21.33% felt like this sometimes. 70.67% reported feeling “bogged down” by the system (48% “Very Often” 22.67% “Often”) and a further 21.33% felt this way sometimes.

The secondary traumatic stress scale assessed EPs’ reactions to exposure to stressful or traumatic events through their work with service users. Higher scores indicate a greater need to examine what aspects of their work or work environment were causing them to feel afraid, experience difficulty sleeping, or avoid reminders of these events. In this study, 73% of the EP sample scored within the moderate or high range on the STS subscale. 29.66% reported feeling “on edge” about things because of the nature of their work (7.33% “Very Often” and 22.33% “Often”) and a further 37.33% felt this way sometimes. Similarly, 35.33% of EPs often found it difficult to separate their personal life from their life as an EP (12.33% “Very Often” and 23% “Often”) and a further 37.33% reported this to be the case sometimes. Additionally, 53.67% felt preoccupied with more than one person they help (17% felt “Very Often” and 36.67% “Often”) and 35.33% responded they felt this way sometimes.

The Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS) was used to measure overall mental well-being, rather than specific determinants. Mental well-being can be assessed in two distinct ways: hedonic and eudaimonic (Ryan & Deci, Citation2001). The hedonic aspects focus on subjective well-being, including feelings of happiness and contentment. The eudaimonic aspects centre on meaning, purpose, and functioning, such as self-acceptance, personal growth, positive relationships, and environmental control (Ryan & Deci, Citation2001).

The SWEMWBS items predominantly represent the eudaimonic perspective, emphasising functioning over emotions. The SWEMWBS, as observed in UK general population samples by Ng Fat et al. (Citation2017), has a mean score of 23.5 and a standard deviation of 3.9. Consequently, approximately 15% of the population is likely to obtain a score exceeding 27.4, prompting the threshold for high well-being to be set at 27.5. Similarly, around 15% of individuals may score below 19.6, leading the cut-off for low well-being to be set at 19.5. In this study, 47% of the EP sample scored within the low well-being range on the SWEMWBS and 1% in the high well-being range (M = 20.8 SD = 2.60). Certain items received more negative responses: 81.33% reported they felt relaxed only rarely or some of the time; 59.7% reported “I’ve been feeling close to other people” only rarely or some of the time. In addition, 54.67% felt that they were “dealing with problems well” only some of the time. When asked if they felt optimistic about the future, 64.67% responded they felt that way rarely or only some of the time.

Phase 2 findings

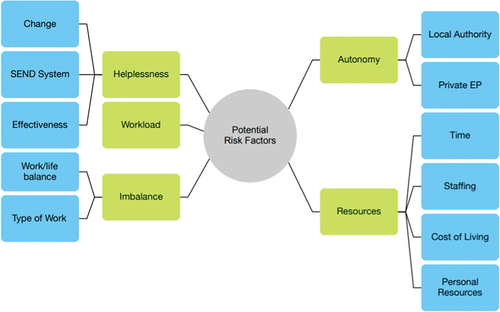

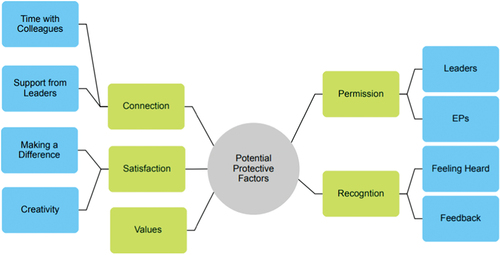

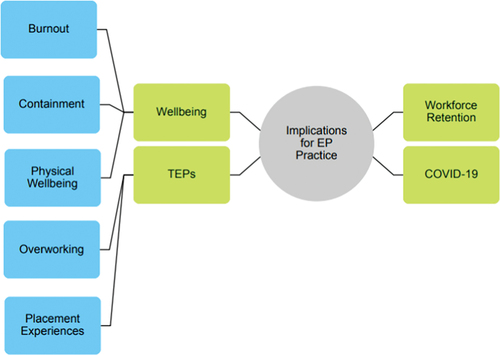

In Phase 2 of the study, 12 EPs participated in semi-structured interviews (see Appendix 1). The themes generated through the analysis of Phase 2 data were then presented in thematic maps in relation to the Phase 2 research questions (see , ).

RQ3:

What are EPs’ perceptions of the potential stressors involved in their experiences of occupational stress and well-being?

Helplessness

The theme of “helplessness” refers to EPs’ frustration with working within the current legislative Special Educational Needs and Disability (SEND) system, and political climate, and the growing sense of futility with regard to the type of work they are required to do. This theme comprised subthemes of change, SEND system, and effectiveness.

Frankly, I don’t see how things are going to change because the level of statutory demand is not decreasing and because the same amount or more is still coming in, we’re never going to catch up with ourselves … there is that sense of it’s just the way it is, and we can’t do anything about it. Almost a sense of helplessness at the moment. (Participant 1)

Workload

The theme of “workload” refers to EPs’ experiences of pressure from current demands and ways of working.

… there is just so much need out there that you can work 24 hours a day if you want to. There is no end, there’s no finish … I’m just battered by statutory working. (Participant 2)

Autonomy

The theme of “autonomy” refers to EPs’ perceptions of their current levels of autonomy, and how that impacts upon their practice, from both LA EPs’ and private EPs’ perspectives: This theme comprised the subthemes of local authority, and private EP.

We’ve had a lot of changes in policy and practice which has reduced our level of autonomy massively as well. So, we have a lot less say in changes and what’s going on within our service … Getting some autonomy back over that is really, you know, crucial to me. (Participant 4)

Resources

The theme of “resources” refers to EPs’ perceptions of what resources they feel they need to do their job well and whether they feel they have those resources. This theme comprised the subthemes of time, staffing, cost of living, and personal resources.

It’s all very well saying how much time things take, but not only is there a time bank, but there’s also banks of stress and energy and resilience which get depleted too, and I’m not confident that that has really been ever explicitly acknowledged in our profession. (Participant 5)

Imbalance

The theme of “imbalance” refers to EPs’ experiences of their work frequently encroaching on their personal time and also refers to the current imbalance between statutory work and other work. This theme comprised the subthemes of work – life balance and type of work.

All of our time has got so squeezed that you’re constantly trying to cut time from other areas. And that’s often your evenings or your weekends or your lunch breaks (Participant 5).

RQ4:

What are EPs’ perceptions of potential moderators involved in their experiences of occupational stress and well-being?

Connection

The theme of “connection” reflects EPs’ views on the importance of feeling connected with others as a way of mitigating some of their occupational stress, and in increasing their feelings of well-being This theme comprised the subthemes of time with colleagues, and support from leaders.

‘I think the opportunities for connection should be highlighted and that we all enjoy our work more when we are connected in some way and we know this, we promote that in our schools but where are we promoting that in our teams? And how do we promote it more?. (Participant 12)

Values

The theme of “values” became prominent in each interview when discussing whether EPs had unique personal qualities that may serve as protective factors against occupational stress. After reflection, all participants felt strongly that this points to a sense of shared values. The more they reflected on this during the interview, the stronger this belief became and led to some useful insights into how this helped them mitigate their occupational stress:

‘… one thing that we’ve done as a team is share all of our individual values to come up with a collective sense of values that we have as a team, and they weren’t far off from each other really. And it’s wonderful because you can meet other EPs and we are really all very different but, on the whole, we are thinking about things in the same way. In that sense, you know you could be psychologically coming from different angles completely, but your underlying aim is the same, which is really key … It was a really lovely experience to do that values work, and it was definitely something that gelled us together. (Participant 8)

Permission

The theme of “permission” captures EPs’ views on how explicit permission around deadlines can help mitigate occupational stress. This theme comprised the subthemes of leaders and EPs.

‘I think we feel better when we are given permission to meet each other and do projects together and work together and share together. We always feel better from that. So, if they give us permission rather than us feeling guilty about it like it’s a forbidden thing, then that would help. Where you’ve got all of these deadlines, to step outside of that would need a senior to sort of say no, absolutely we want you to do that and take time for that. (Participant 5)

Satisfaction

The theme of “satisfaction” refers to the role of job satisfaction as a mitigating factor for EPs in their experiences of occupational stress and the types of opportunities that there are to gain satisfaction from their work. This theme comprised the subthemes of making a difference and creativity.

I think that one of the things that I’ve noticed as I’ve moved through my career is the creativity of EPs. There is a lot of creative thinking around how to work with schools, how to work with children, and how to work at systemic as well as group levels … if there were opportunities for EPs to work in the ways they want to work, using pure consultation, using more creative methods, working systemically with schools with less emphasis on individual assessment then that would be hugely protective. (Participant 4)

Recognition

The theme of “recognition” captures the importance of EPs knowing that their contributions are listened to, included, and valued. This theme comprised the subthemes of feeling heard and feedback.

Getting feedback, even if it’s just to say well done, or thanks for doing that. That is great. And it just helps. It helps to make sense of why I choose to do what I do and then I go on to the next one. For me, that would be enough. I don’t need all bells and whistles of how amazing I am. I just need that little bit of yeah that was good enough, that was okay, and that worked well in that situation. (Participant 5)

RQ5:

What are the views of EPs on the implications of occupational stress on EP practice?

Well-being

The theme of “well-being” refers to the implications for EP practice when considering the reported levels of well-being in EPs. This theme comprised the subthemes of burnout, containment, and physical well-being.

I remember going to one school and spending time with a child. And it was absolutely fine, and she wouldn’t have known and no one in the primary school would have known there was anything up for me. But I remember getting back into my car and being kind of close to tears because of the effort it had taken for me to pretend that everything was okay. (Participant 2)

I think therapists in training have a lot more support around acknowledging the impacts of that transference between stressful situations and on them as individuals. I’m not sure any of that is ever really, properly acknowledged in the EP profession and we are seen as this kind of people that just crack on regardless. (Participant 5)

If nothing changes, I think there will be EPs taking more time off, having more illnesses. (Participant 6)

Workforce retention

The theme of “workforce retention” relates to the views of participants regarding the perceived implication that a greater number of EPs will seek alternative ways of working in response to current stressors:

It’s sad because we spend a lot of time and effort and money to train people and get people to a good place and we just can’t retain them. So, it feels like something’s got to give. It’s not going to be us in the sense that we won’t be around. But it’s ultimately the children and young people that are going to suffer at the end of it - ironically, the people you’re trying to help. (Participant 8)

Trainee educational psychologists (TEPs)

The theme of “TEPs” refers to EPs’ concern over the implications for practice that the current workforce stressors and challenges may have on trainees. This theme comprised the subthemes of overworking, and placement experiences.

I think a lot of EPs feel more despondent, helpless at the moment. And that makes me worry for the TEPs coming through, they’re starting from a different place than they were ten years ago (Participant 12)

I feel so sorry for the TEPs because they’re not in an office space, hanging around other EPs to just pick up little snippets of information and to learn more. I feel that they’re really lonely and isolated, often only with their supervisor when actually I think they need to be with lots of EPs and just absorb information. (Participant 12)

COVID-19

The theme of “COVID-19” refers to findings that highlight that the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic have been overwhelming for some of the EP professionals. Increased demand and complexity of casework, responsibilities, and changes to home – work life could have a lasting impact on well-being and professional quality of life.

And I naively, I suppose, assumed that COVID wouldn’t have the impact it did have. But that is our life now and it feels very much that when you are very, very stretched, the one thing you can rely on is our relationships with each other. But if you can’t fully access that in a way that feels like it’s meeting that emotional kind of need then that makes it even harder. Resilience is lowered even further. (Participant 8)

Discussion

The insights gained from this study have contributed to a better understanding of the occupational stress experiences of EPs. Although the aim of this study was not to explore the wider political landscape of special educational need and disability (SEND) legislation, it would be naïve to dismiss the significant part this has played in the findings that have emerged. The findings of this research have shed light on the wider systems and political contexts that impact EPs’ levels of occupational stress and well-being. In recent years, there have been numerous reports of widespread shortfalls in support for children with SEND, including a shortage of specialist teachers, long waiting times for EHC plans, and inadequate funding to provide SEND support in schools (The British Psychological Society [BPS], Citation2020). The impact of these challenges has been felt acutely by EPs, who play a critical role in supporting children with SEND. The increasing demand for their services, combined with the lack of resources and support, has led to prominent levels of occupational stress and a high risk of burnout among educational psychologists.

The findings of Phase 1 suggested that participants experienced reduced levels of compassion satisfaction along with moderate to high levels of burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and decreased well-being. In Phase 1, a total of 92% of participants reported that they felt “bogged down” by the system, whilst just under 90% reported feelings of being overwhelmed due to a workload that seems endless. These findings were further supported in Phase 2, when participants were asked to describe their work, and were consistent with each other when recounting the relentlessness of the workload throughout the academic year, insufficient staffing, and the overwhelming nature of time-bound statutory demands. In Phase 2, the lack of connection with others, reduced autonomy, and lack of resources were also emphasised as significant contributing factors to their elevated levels of stress.

Everyday stressors identified through Phase 2 were a gradual erosion of professional autonomy, insufficient remuneration for additional incurred costs, such as fuel, and everyday administrative tasks that were in addition to their tasks as an EP. Previous research conducted by Deci et al. (Citation2017) identified the significance of employee autonomy as a crucial factor in experiencing a sense of accomplishment in their role. The current research suggests that when EPs feel capable of controlling their work environment, this can assist them in moulding their jobs to align with their values, thereby reducing the effects of excessive job demands. Consequently, this helps to prevent emotional exhaustion and promotes a sense of achievement linked to the job (Karasek, Citation1979).

These findings emphasise the need to ensure that both workload and work-related control are congruent with the values of EPs to facilitate a sense of achievement within their EP role. In addition, an examination of the qualitative data from Phase 2 revealed that increasing worry over the cost of living, high fuel costs in the course of carrying out their work, and additional travel time incurred over expanding geographical patches of schools were also highlighted as sources of significant stress for some EPs.

The results and findings obtained from Phases 1 and 2 indicated elevated levels of occupational stress in EPs, particularly in the domains of burnout and secondary traumatic stress. Consequently, a hypothesis proposing the susceptibility of EPs to developing compassion fatigue is plausible. To understand the current risks associated with compassion fatigue development in EPs, two theoretical frameworks are valuable.

First, the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, Citation2001) asserts that individuals strive to acquire, retain, and safeguard resources that are significant to them, such as social support, financial means, and time. When considering the Phase 1 findings, it seems that EPs’ work may deplete their emotional and cognitive resources to a considerable extent, rendering them susceptible to compassion fatigue if these resources are not replenished adequately (Hobfoll et al. Citation2018).

Second, the availability of job resources plays a crucial role in mitigating compassion fatigue among EPs. The job demand-resources (JD-R) model (Demerouti et al., Citation2001) proposes that job demands, such as heavy workloads, time pressure, and role ambiguity, can lead to stress and burnout unless they are balanced by job resources, such as autonomy, support, and recognition. These findings suggest that some of the major factors in EPs’ levels of occupational stress and well-being are related to the wider systemic issues highlighted in previous research (Gersch & Teuma, Citation2005; Leyden, Citation1999; Lyonette et al., Citation2019). It is worth noting that these factors have continued to intensify, with systemic stressors at the governmental level remaining largely unchanged. Referring to Leyden’s (Citation1999) contribution nearly a quarter of a century ago, his prophetic words undoubtedly strike an uncomfortable chord when considering the findings of this study:

‘If the “coping response” to increasing workloads, expectations, and accountability is for EPs to work longer and harder, the inevitable result will be professional burnout (Leyden, Citation1999, p. 227).

Strengths and limitations of the current research

For both phases of the research, participation was limited to EPs in England. Individuals from Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland were not included due to the additional time and resources that would have been required, which were beyond the scope of this study. In Phase 1, data were gathered using an online survey employing a convenience sampling method. The survey link was broadly shared via social media and sent to educational psychology services in England. Although this data collection approach was straightforward and efficient, it could have introduced a potential for bias in participant selection. It could be argued that the sample in both phases might have been skewed towards those with available time to participate, or those particularly concerned about their well-being and that of their colleagues, thus influencing their willingness to take part. In addition, it is important to acknowledge a limitation regarding the lack of collection of ethnicity information from participants. Consequently, the findings may not be easily applied to a broader population of educational psychologists and could be influenced by bias.

Additionally, there was no assessment conducted before participation to identify whether respondents had encountered any specific challenges that might have impacted how they reported their professional quality of life and well-being. Nonetheless, it should be noted that this study employed a mixed-method approach, with Phase 1 having a sample of over 300 participants, which has the advantage of mitigating the drawbacks of each method while capitalising on their strengths (Creswell & Clark, Citation2017); in other words, the data gathered in phase one provided support for the data collected in phase two, thereby enhancing the overall validity of the results (Dawadi et al., Citation2021).

Implications for practice

These findings have numerous practical implications. First, it is important for government policymakers at both local and national levels to acknowledge and address the factors that are contributing to such elevated levels of occupational stress in the educational psychology profession. Open and honest consultations need to be held with EPs to increase confidence that their expertise is valued, and that they are being listened to, particularly when the concerns that they are expressing about their own current occupational stressors could also be said to be reflective of the wider systemic issues within SEND.

Overall, the combined effects of burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and reduced levels of compassion satisfaction and well-being can have a significant impact on the mental and physical health of educational psychologists. Additionally, the phenomenon of compassion fatigue has been found to result in increased incidences of staff absence and staff turnover, as well as decreased productivity, as reported by Figley and Ludick (Citation2017). Based on the findings of this study, it can be inferred that psychological distress, including burnout and compassion fatigue, could be a significant factor prompting EPs to exit local authority work and explore alternative avenues to remain within their profession. Although participants in the study did not encounter compassion fatigue to an extent necessitating the complete abandonment of their occupation, indications of compassion fatigue were manifest within their discourse.

It was suggested that social factors could either add to, or shield individuals from, compassion fatigue. The EPs stated that having time to be with supportive colleagues helped mitigate their stress. This supports the findings of Bessen et al. (Citation2019), who emphasised the importance of healthcare professionals being able to talk about patient/client experiences with their colleagues. However, owing to their increasing workload, EPs may often neglect this sharing of experiences, which increases the risk of developing compassion fatigue. This implies that a compassionate fatigue framework may serve as a pertinent instrument for comprehending the experiences of occupational stress and the low levels of well-being encountered by EPs. Participants’ honest reflections about the challenges of feeling overwhelmed, managing workload, attaining a satisfactory work/life balance, with diminishing personal resources also highlighted noteworthy aspects of compassion fatigue.

This study also underscores the significance of recognising that the educational psychology workforce in the UK was already a challenging area of employment before the COVID-19 pandemic, as found in the EP workforce study in 2019 (Lyonette et al., Citation2019), with an elevated risk of stress associated with work pressures and caseloads. Therefore, a major implication of this study is that it draws attention to the need for services and government agencies to address the widespread stressors that were already present before the pandemic, and have been exacerbated since, and which may still be contributing to the high vacancy rates and increasing retention challenges. Such factors not only directly affect the well-being of EPs but may also negatively impact the children, families, and communities they remain committed to serving.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Association of Educational Psychologists [AEP]. (2023). General secretary blog: Insights on the EP workforce. https://www.aep.org.uk/articles/general-secretary-blog-insights-ep-workforce

- Berjot, S., Altintas, E., Grebot, E., & Lesage, F.-X. (2017). Burnout risk profiles among French psychologists. Burnout Research, 7, 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2017.10.001

- Bessen, S., Jain, R. H., Brooks, W. B., & Mishra, M. (2019). “Sharing in hopes and worries” a qualitative analysis of the delivery of compassionate care in palliative care and oncology at end of life. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 14(1), 1622355. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2019.1622355

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide [eBook version]. SAGE.

- Briggs, C. L. (1986). Learning how to ask: A sociolinguistic appraisal of the role of the interview in social science research. Cambridge University Press.

- The British Psychological Society [BPS]. (2020). Changing ideologies and the role of the educational psychologist. Retrieved September 25, 2022, from https://www.bps.org.uk/psychologist/changing-ideologies-and-role-educational-psychologist

- Carson, J., & Kuipers, E. (1998). Stress management interventions. In S. Hardy, J. Carson, & B. Thomas, (Eds.), Occupational stress: Personal and professional approaches (pp. 157–174). Nelson Thornes.

- Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Hirose, M. (2019). Mixed methods and survey research in family medicine and community health. Family Medicine and Community Health, 7(2), e000086. https://doi.org/10.1136/fmch-2018-000086

- Dawadi, S., Shrestha, S., & Giri, R. A. (2021). Mixed-Methods research: A discussion on its types, challenges, and criticisms. Journal of Practical Studies in Education, 2(2), 25–36. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED611786

- Deci, E. L., Olufsen, A. H., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-Determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4(1), 19–43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113108

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

- Department for Education [DfE]. (2023). Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) and Alternative Provision (AP) Improvement Plan: Right support, right place, right time. Retrieved March 6, 2023, from. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1139561/SEND_and_alternative_provision_improvement_plan.pdf

- Figley, C. R., & Ludick, M. (2017). Secondary traumatization and compassion fatigue. In: APA handbook of trauma psychology: Foundations in knowledge (Vol. 1, pp. 573–593). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000019-029

- Gersch, I., & Teuma A. (2005). Are Educational Psychologists Stressed? A Pilot Study of Educational Psychologists’ Perceptions. Educational Psychology in Practice, 21(3), 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667360500205909

- Health and Safety Executive [HSE]. Stress at work—Work-related stress and how to tackle it. https://www.hse.gov.uk/stress/what-to-do.htm

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

- Karasek, R. A. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(2), 285–308. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392498

- Leyden, G. (1999). Time for change: The reformulation of applied psychology for LEAs and schools. Educational Psychology in Practice, 14(4), 222–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/0266736990140403

- Lyonette, C., Atfield, G., Baldauf, B., & Owen, D. (2019). Research on the educational psychologist workforce: Research report. Retrieved March, 2019. Research on the Educational Psychologist Workforce: Research report (ioe.ac.uk).

- Ng Fat, L., Scholes, S., Boniface, S., Mindell, J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2017). Evaluating and establishing national norms for mental wellbeing using the Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (SWEMWBS): Findings from the health survey for England. Quality of Life Research, 26(5), 1129–1144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1454-8

- Oates, J., Carpenter, D., Fisher, M., Goodson, S., Hannah, B., Kwiatowski, R., Prutton, K., Reeves, D., & Wainwright, T. (2021). BPS Code of human research ethics. British Psychological Society.

- Reupert, A., Schaffer, G. E., Von Hagen, A., Allen, K.-A., Berger, E., Büttner, G., Power, E. M., Morris, Z., Paradis, P., Fisk, A. K., Summers, D., Wurf, G., & May, F. (2022). The practices of psychologists working in schools during COVID-19: A multi-country investigation. School Psychology, 37(2), 190–201. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000450

- Rupert, P. A., Miller, A. O., & Dorociak, K. E. (2015). Preventing burnout: What does the research tell us? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 46(3), 168–174. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039297

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

- Schaffer, G. E., Power, E. M., Fisk, A. K., & Trolian, T. L. (2021). Beyond the four walls: The evolution of school psychological services during the COVID‐19 outbreak. Psychology in the Schools, 58(7), 1246–1265. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22543

- Shield, W. (2023). The role of academic and professional tutors in supporting trainee educational psychologist wellbeing. Educational Psychology in Practice, 39(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2022.2148635

- Sinclair, S., Raffin-Bouchal, S., Venturato, L., Mijovic-Kondejewski, J., & Smith MacDonald, L. (2017). Compassion fatigue: A meta-narrative review of the healthcare literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 69, 9–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.01.003

- Stamm, B. (2010). The concise manual for the professional quality of life scale. Retrieved March 25, 2022 from https://www.academia.edu/download/62440629/ProQOL_Concise_2ndEd_12-201020200322-88687-17klwvb.pdf

- Stewart-Brown, S., & Janmohamed, K.(2008). Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS) User Guide Version 1 (Edited by, Parkinson J.). NHS Health Scotland.

- Tomlinson, P. (1989). Having it both ways: Hierarchical focusing as research interview method. British Educational Research Journal, 15(2), 155–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192890150205

- Vaingankar, J. A., Abdin, E., Chong, S. A., Sambasivam, R., Seow, E., Jeyagurunathan, A., Picco, L., Stewart-Brown, S., & Subramaniam, M. (2017). Psychometric properties of the short Warwick Edinburgh mental well-being scale (SWEMWBS) in service users with schizophrenia, depression and anxiety spectrum disorders. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 15(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0728-3

- Van den Broeck, A., Ferris, D. L., Chang, C.-H., & Rosen, C. C. (2016). A review of self-determination theory’s basic psychological needs at work. Journal of Management, 42(5), 1195–1229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316632058

- Van den Broeck, A., Vansteenkiste, M., De Witte, H., & Lens, W. (2008). Explaining the relationships between job characteristics, burnout, and engagement: The role of basic psychological need satisfaction. Work & Stress, 22(3), 277–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370802393672

- Warwick Medical School. (2016). Swemwbs. Retrieved November 1, 2023, from. https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/med/research/platform/wemwbs/