Abstract

This paper compares two strikingly different uses of water. The first by an adolescent young man on the autistic spectrum, in an art psychotherapy session; the second, by an ordinary developing toddler, observed at home. It uses insights gleaned from psychoanalytic infant observation to illuminate the seemingly enigmatic behaviours found in clinical practice. In doing so, it delineates the centrality of joint visual attention in the development of symbol formation. Understanding is advanced by making evident that water may be used to either enable or inhibit this process. As such, it argues that the phenomenon of liquidity be given greater consideration. Further, it critically champions for the inclusion of infant observation in art psychotherapy training.

Introduction

In this paper I investigate two children’s different uses of water. My interest was sparked from my work as an art psychotherapist within a school for profoundly autistic children on the one hand, as well as from my observations of an ordinary developing infant, as part of a psychoanalytic observational training, on the other. I noticed that many of the young people who attended art psychotherapy were preoccupied with water at the sink often to the exclusion of everything else. Water is one of the few substances that spontaneously holds their attention. It has been interesting to observe the young people’s idiosyncratic use of water, which reveals something of their personalities. Their repertoire of behaviours around the sink include: leaving the tap running or constantly turning it on and off; using a container and being aware when it is full or letting water endlessly overflow; being interested in the empty plug hole or concerned with blocking it up; using their bodies to engage with the water or only touching water through another object; using water either with precision or with carefree abandon, as well as many variations in between. Although often enigmatic, their use of the water appeared to me to hold a valuable opportunity to gain insight into their way of being in the world.

Coincidentally, during this time, the young girl that I had been naturalistically observing since birth – as part of a psychoanalytic infant observation training – at 17 months, started to use water in her sink at home. What was striking about her play with water was that it was highly imaginative and relational. This was in sharp contrast to the repetitive and insular quality of the young people’s use of water at the school. From these contrasting experiences I was prompted to investigate how infant observation might inform understanding of the conditions that enable water to be used in a symbolic, playful and relational manner. Therefore, this paper endeavors to look with liquid in light of infant observation to illuminate the encounter in art psychotherapy. In doing so, it aims to understand the preconditions that enables symbol formation in the respective contexts. This exploration may, in turn, inform art psychotherapists’ understanding and facilitation of how the concrete may be transformed into the symbolic, in the service of object relations.

Method: infant observation as research

Prior to exploring how psychoanalytic observational practises may inform art psychotherapy, it is useful to delineate its methods and to situate it within qualitative research more broadly. Psychoanalytic infant observation is associated with Esther Bick who inaugurated the practice, with the support of John Bowlby, in 1948 at the Tavistock clinic, London (Bick, Citation1964). Bick’s formalisation of infant observation, as part of child psychotherapy training, suggests an hour-long, weekly observation of an infant from birth until two-years-old, with mother and family, in their domestic setting.

The observational protocol includes that the observer be a friendly but non-initiating presence and to pay close attention to the unfolding interaction between baby, their carers and siblings. Following this, the observer is expected to write-up their observations, which are later presented to a small seminar group, classically led by an experienced child psychotherapist. These seminars aim to infer – amongst other elements – the subjectivity and intrapersonal process of the infant through the unfolding interpersonal relationship between the infant and their primary caregivers. This process points to a central paradox of infant observation, that of looking from the outside while seeing on the inside. Despite this methodological complexity, the growth in appreciation of Bick’s infant observational protocol is evident by its incorporation as a standard training component in many therapeutic courses in the United Kingdom including several arts and play therapy programmes.

Bick’s observational methodology places extensive importance on the observer’s own subjectivity to inform the observation and can be understood to operate as a ‘particular kind’ of subjective objectivity. Alvarez describes this objectivity as:

… (the observer uses his feelings of empathy and even of countertransference in his description of what is taking place,) but he also tries to use perception to act as a check on preconception. (Citation1989, p. 14)

Rustin points out that Bick’s methodology was to use the observations to generate hypotheses about the inferred ‘states of mind, interactions and unconscious communication’ (Citation2009, p. 31). This requires additional observations to either confirm or refute interpretations regarding the internal world of the infant and the observed family.

This hermeneutic tradition of naturalistic infant observation has been broadened out as a methodology for understanding unconscious and infantile process in other environments and contexts – see Shuttleworth (Citation2012), Elfer (Citation2006), and Hinshelwood et al. (Citation2002).

The controversial encounters between André Green and Daniel Stern in 1997, and between Green and Peter Fonagy in 2002, have deepened the debate around the value of visual research in psychoanalysis. These encounters have provocatively questioned the degree of relevance of child development research and neurodevelopmental studies for clinical psychoanalysis. In turn, this raises several clinical and research concerns for related fields such as art psychotherapy. The debate involves a clear divide between those who only considered the clinical context able to generate psychoanalytic insight and those who value extra-clinical research (Leuzinger-Bohleber & Fischmann, Citation2006), which included the observational practices described above.

These debates open up a space for art psychotherapy to also explore and test out the epistemological value of some of its truth claims, which – similar to infant observation – are also predicated on visual forms of knowing. While it is outside the remit of this paper to explore the epistemological affordances and constraints of naturalistic infant observation, it is useful to be critical of its truth claims. Against this backdrop, the data collection reports within the paper-one from a work experience context, the other from an infant observation – have been written within the overarching principles of Bick’s observational practice. The data collection also form part of a methodological tradition in psychoanalysis where infant observations are used as part of case study research (see McLeod, Citation2010, and Skogstad, Citation2004).

Having briefly described the method of infant observation, its problematics and potential, it is now possible to begin to explore its methodological relationship to art psychotherapy. In doing so, this research paper occupies a meta-methodological position in relation to the respective fields.

Methodological framework: triadic practices of looking

While many art psychotherapists are drawn to the practice of baby watching, theoretical and conceptual links between art psychotherapy and infant observation remain sparse. Exceptions to this include the work of Radley (Citation2018), Siegel (Citation2011), Waller & Dalley (Citation1992) and Zago (Citation2008). These examinations are important. However, this investigation takes a different investigatory route while simultaneously avoiding any conflation between the fields. Here, their link is studied by examining the practices of looking implicit in the respective disciplines. As shortly explicated, art psychotherapy and infant observation can both be understood to be predicated on – as well as to promote – triangular ways of looking. These triadic practices can be considered to be underpinned by joint visual attention skills, which structures how two sets of eyes join minds on a shared object, event or experience. As such, triadic ways of looking will be deployed as the central structural and methodological motif intersecting both domains. It should be noted that triangular ways of looking are used here as the prototypical form, although clearly more complex permutations may exist (See Case, Citation2011).

Further, this triangular relationship implicit in infant observation, art psychotherapy and joint visual attention skills is privileged, as this exploration is concerned with the virtuous cycle in which triadic ways of looking on the outside may help structure the development of symbol formation and reflexivity on the inside, which is arguably the central capacity for therapeutic efficacy. This capacity for symbol formation and reflexivity – as well as its absence – has been a longstanding preoccupation in both psychoanalysis (see Segal, Citation1957) and art psychotherapy (see Mann, Citation1997), making it pertinent for investigation. To begin, it is first useful to examine how triadic ways of looking are intrinsic to the capacity of joint visual attention.

Triangular structure of joint visual attention

Joint attention skills are a range of behaviours that usually develop within the latter part of the infant’s first year of life and include the sharing of attentional focus and affect around a common object or event (Scaife & Brunner, Citation1975). Although shared attention is not dependent on sight, joint visual attention corresponds to the ability to follow another’s eye direction or gaze and requires, to put it simply, ‘looking where someone else is looking’ (Butterworth, Citation1991, p. 223). Pointing and head-eye orientation are central in aligning the line of sight of both participants, so that ‘one interactional partner attends to the other's direction of gaze’ (Corkum & Moore, Citation1998, p. 28). Joint visual attention episodes are triadic in nature and involve the infant’s alternating co-ordination of visual attention both to the target object and to the partner, prototypically the mother. It not only includes the infant sharing attention with mother but also includes the monitoring and shaping of the mother’s attention around an object.

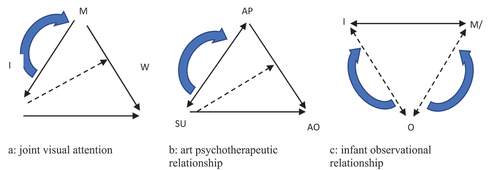

For Trevarthen (Citation1979), this developmental achievement is a two-step process where the infant first needs an experience of primary intersubjectivity prior to developing the capacity for secondary intersubjectivity. Primary intersubjectivity refers to the phenomena of face-to-face relatedness between the infant and their primary caregiver, illustrated by the bidirectional arrows on the I-M axis in . In important ways, this capacity for the mother to attune (Stern, Citation1985) to the infant in face-to-face relating is also dependent on mother’s capacity to allow the infant to look away and self-regulate prior to returning to engagement (Stern, Citation2004). From here the infant may develop a capacity for secondary intersubjectivity which is the growing awareness that other people have minds of their own with their unique attentional focus (represented by the curved arrow in ), and that this may shape and direct a shared experience of the world (represented by the dotted arrow in ). This alternating of the attentional gaze between both participants M(other) and I(nfant) and the W(orld) is triangular in structure and requires the capacity for triadic relating, which, rather than being an innate behaviour, is borne out of earlier interpersonal relating and emotional development.

Figure 1. (a–c) Triangular structure of joint attention, art psychotherapy and infant observation (with reference to Hobson, Citation2002).

Triangulation in art psychotherapy

The intentional introduction of art materials as a third element into the therapeutic dyad, creates the triangular structure that comprises the art psychotherapeutic relationship (see ). This triadic relationship may be regarded as the defining characteristic of the profession. Scholars such as Wood (Citation1990), Case (Citation1990) and Schaverien (Citation2000) have all contributed to the profession’s theoretical development by placing different emphasis on the constituent axes of the triangle. Although the structure of joint visual attention can easily be transposed onto the art psychotherapeutic relationship ( is almost identical to ), joint attention skills have largely been considered as an implicit or a priori capacity of the service user within the therapeutic setting, rather than a developmental achievement.

More recently, the role of joint visual attention in art psychotherapy has been given greater attention. Damarell (Citation1999) and Isserow (Citation2008, Citation2013), have begun to make links between joint visual attention skills and art psychotherapy noting how triadic practices of relating in art psychotherapy are predicated on, and also promote the experience of looking together. This alternating gaze between participatory partner and the art object – as described above – actively establishes the opportunity for the service user to apprehend the mind of the therapist in relation to their own mind. This can be seen in , where the ability to occupy the other’s position is indicated by the arrow moving on axis SU to AP. This flexibility of orientation – so that both service user and therapist may occupy the other’s point of view and infer their state of mind – is also known in developmental psychology as mentalisation (Franks & Whitaker, Citation2007) and contains the potential to promote epistemic trust (Fonagy & Allison, Citation2014). In clinically important ways, art psychotherapy offers the opportunity for shared psychological contact vis-à-vis the art object, that can modulate the intensity experienced through direct eye-to-eye contact.

The triangulated infant observational gaze

The domestic ethnographic context of infant observation is highly complex, potentially comprised of multiple minds that may look separately and together in their evolving relationships. The infant, located in this matrix, forms the focus of these observations. However – taking up the position of the observer – it is possible to consider the observational gaze as triadic in structure, as it is prototypically comprised of the (O)bserver looking at the (I)nfant—(M)other dyad, as seen in . As already explored, the gaze of the art psychotherapist and that of the service user can also be thought of as triangulated. As such, it is a small step to link the triadic structure of the infant observational gaze with practices of looking in the art psychotherapeutic relationship, while simultaneously noting their radically different components, contexts and outcomes.

This triangulated observational gaze provides significant opportunity to develop a range of emotional skills, so that the observer may look with ‘feeling and meaning’ (O’Shaughnessy, Citation1989). Maiello (Citation2007) articulates this from a psychoanalytic perspective, writing about the triadic gaze in relation to the paternal function of the observer:

This function entails the development of the ability to bear feelings of exclusion, to tolerate not knowing, to be in the position of the third, which is the position of otherness. It means accepting not to be in control, allowing events to happen without being able to foresee and to monitor them. It means developing the negative capability. This is the basis of the capacity for genuine listening and creative thinking about psychic reality, not only the others’, but essentially one’s own (pp. 48–49).

These emotional capacities are pedagogically useful, placing infant observation, as Sternberg (Citation2018) notes, at the heart of psychotherapeutic training. Following on, it may be argued, that similar emotional capacities are required in the trainee art psychotherapist who occupies a triadic position akin to that described above. Further, triangular relationships are also central to meaning production in art psychotherapy and infant observation. Supervision is part of good practice in art psychotherapy providing the ‘third gaze’ from a senior clinician overseeing clinical practice. Similarly, in infant observations, understanding is generated through the triangular perspectives of the study group and facilitator, who may occupy different emotional and psychological understandings to that of the observer. These interdependent and nested triangular ways of ‘seeing’ are implicit in the understanding gleaned from the respective experiences, as briefly explored below. In exploring triangularity in relation to the development of symbolism, it is useful to make explicit the psychoanalytic theory of symbol formation that underpins this paper. It draws on the Bionic tradition as adumbrated in ‘A Theory of Thinking’ (Bion, Citation1962). Here, the birth of symbolic thought is formed in direct relationship with the infant’s capacity to tolerate frustration when faced with the absent breast. He writes: ‘If the capacity for toleration of frustration is sufficient then ‘no breast’ inside becomes a thought, and an apparatus for ‘thinking’ it develops.’ (Citation1962, p. 179). By implication, the capacity to tolerate the frustration of the absent primary object must include the capacity to bear separateness and the inevitable thought that the primary object (mother) is with (an)other, establishing the third position of a triangular relationships. In this sense, symbolic thinking is not only borne out of the capacity to tolerate the frustration of separateness but also of the frustration of exclusion. It is this theory of the formation of symbolic thinking that acts as a leit motif, applied retrospectively to the observations below.

So far, this investigation has begun to explore how joint visual attention structurally links infant observation with art psychotherapy. It is now possible to examine this phenomenon more closely by comparing the two different uses of water. Consent to use clinical material for educational and research purposes including publication was obtained from the parents, through the school’s head teacher. Similarly, consent to use observational material has been obtained for educational and allresearch purposes including publication was obtained from the parents of the observed infant at the start of the infant observation. All personal information has been anonymised.

Data description 1

Andrew: identification with a speaking mouth

At the time of writing the report, I worked as an art psychotherapist within a residential school for profound learning-disabled children that presented with autistic and challenging behaviour. The art therapy room is of moderate size, containing a large table with a variety of art materials. There is also a sink in the corner with a range of containers available on the side for the young people to use.

Andrew is a 15-year-old boy on the autistic spectrum who had been attending art therapy on a weekly basis over a period of 4 months. There was limited historical and contextual information about him when we started working together. On first meeting him, I was struck by how his blond-brown hair fell like a mop over his eyes hiding his face behind a tall and heavy-set build. He has a kind face which is often scrunched up in a half grimace or smile. Behind this are two intensely blue eyes, which seldom allow any mutual contact. Andrew is incontinent and requires the use of pads to keep himself clean. He has a gentle, if not placid, feel about him and often when I arrive to collect him, I find him sitting slumped at his desk or focusing on a distant place. When I approach him, his eyes do not adjust to meet mine, and his gaze seems to look right through my body. However, one substance that evokes life and interests for Andrew is water, which he has access to in his art psychotherapy sessions. He often uses water obsessively to the exclusion of all else, becoming strangely animated while doing so. The following is an extract from our session just after a break. It is 11.00 am in the morning and this is an extract from both the start and end of a 50-minute session:

Coming into the art room Andrew makes straight for the sink and points his index finger into the empty plughole. He maintains a fixed gaze on the hole while I say to him that I was wondering if he was thinking about things gone and me gone over the holiday? There is no sign that my words mean anything and he begins his ritual of placing his face near the container in the sink, filling it up to just overflowing, only to tip the water out and watch intently as it disappears down the hole, all the time becoming more and more excited … He repeats this cycle continuously at the sink and I try to put into words and describe his actions and excitement of filling and emptying the container with water. Suddenly, Andrew stops and brings his face almost uncomfortably close up to mine. For a micro-moment, there is sense of possible eye contact. However, he moves away and swiftly returns to the sink where he begins his ritual of filling up and pouring out the container in the sink. After a while I encourage Andrew to sit at the table and use the art materials. He complies, sits down and without looking, draws on the paper with the lid still firmly on the felt tip. He leaves no mark on the paper and he quickly stands up to return to the sink.

Then later …

It is time to go and I tell Andrew that we will need to finish being together today. After repeating this to him a few times he finally responds by placing the empty bowl upside down on the side. I say bye-bye to him and to my surprise he briefly glances at my face and says ‘bye-bye’ back to me (These are the first words I have ever heard him say!). We then make our way back to his class.

Data analysis 1

This report provides a wealth of material for exploration, however, for the purposes of this paper, I will focus on moments of the development of visual intersubjectivity. On returning to the room after the break, Andrew proto-imperatively points to the empty plughole as if to say that there should be water in there. As he makes no eye contact at this point, this does not feel like a communication of my absence during the break, which on reflection makes my commentabout my absence premature. Instead, it seems to be an attempt to regain that watery substance which could possibly support an amorphous and undifferentiated state of mind in the world. His use of water can possibly be understood to support a fused relationship with the sink and plughole, becoming increasingly excited as the fluidic substance flows down the plug, again blurring any distinctions of a self and an other.

However, there is a sudden change in his behaviour after I describe his actions and behaviour to him at the sink. This description seems to help Andrew connect up to me as he responds to my words by coming to stand very close, looking into my face. I wondered at the time if my verbal descriptions of his actions helped Andrew achieve a faint awareness of myself as a separate person in the room.

With this burgeoning awareness of myself in the room, being more separate and available ‘out there’ for him, he is able to bring his face close up to mine, in similar proximity and position to when he looked into the water contained in the sink. It is possible to speculate that, at this moment, Andrew is no longer equated with the sink; rather his face is in direct relation to a human face which forms the conditions for primary intersubjectivity. He sustains eye contact (albeit brief) with a ‘live object’ (Alvarez, Citation1992) who has a mouth like him and who pays attention to him, reflecting him back to himself. Perhaps this human engagement with myself potentially opens up the realm of interpersonal engagement and symbol formation as a means of making a connection between two people. However, the intensity of his look into my eyes feels as if it quickly becomes unbearable for Andrew, as he seems incapable of sustaining and retaining this recognition of the other, and he rapidly returns to the sink. I was left wondering how Andrew experiences the meeting of eyes. As mentioned above, in ordinary mother-infant development, the mother also needs to allow the infant to self-regulate and look away during intersubjective moments.

When he turns away from this visual contact, I attempt to retain a sense of being in relationship with Andrew and ask him to draw on the paper. This would enable us to potentially have a shared visual encounter by looking together. Andrew seems to find dyadic (let alone triadic) looking challenging. However, it is most surprising when at the end of the session he is able to acknowledge something of our separateness and absence when he says ‘bye-bye’. His vocalisation, along with his briefly sustained eye contact, feel like a communication rather than a mechanical echolalic response. At this moment he does seem to be able to identify with my speaking mouth, a human mouth that can then be used in a meaningful way, to make a meaningful connection between us.

Data description 2

Katie: the re-creation of memory

The following extract is of an observed infant called Katie, who is the third daughter in a family who live in a garden flat in a large city in the United Kingdom. Katie has a brother and sister, three and five years older respectively. Katie’s parents are professionals and both in their mid-thirties. This observation finds Katie playing at the sink, with Mother in the kitchen, shortly after the return of the whole family from an enjoyable holiday on the coast. It is evident how much Katie has changed over the summer: her straight blond hair has grown down almost to her shoulders, framing her face, and accentuating her complexion and large green eyes. She also appears taller and more confident.

As Katie’s behaviour has its roots in her infancy, it is helpful to briefly gain a background picture of her development, prior to examining her use of water. Katie and her Mother have always enjoyed, from the start of life, a very affectionate relationship, except around areas of food and feeding. From very early on, when Katie was around three weeks old, Mother and daughter experienced difficulties in feeding as Katie – sucking at the breast – would often insert her fingers or muslin cloth into her mouth. Mother would then gently pull Katie’s fingers away from her mouth which in turn disrupted the feed. There seemed to be a sense in their relationship of a struggle of control or ownership over the breast. This resulted at 6 weeks of Katie being unable to take to the breast and for a short period there was a failure to thrive before Katie was fed on the bottle. While Katie continued to insert her fingers alongside the teat of the bottle into her mouth when feeding, there was a greater sense of Mother allowing Katie to do this and she could be fed.

This is our first observation since their return from the break. It is 4:00 pm afternoon on a late summer's day. Katie is 16 months and 3 weeks old. The extract is from twenty minutes into an hour-long observation:

Coming over to the sink Katie points up to the taps saying ‘mummy mummy’ in an imploring manner. Mother, who is standing attentively beside her, asks her if she would like to play in the sink. Katie nods her head and smiles sticking out her tongue at the side of her mouth in eager anticipation. Mother gingerly lifts Katie up so that she is sitting on the kitchen counter, barefooted with her legs inside the sink. Emphatically Katie points to the drying rack on the other side of the sink and makes an exclamatory ‘kaah’ sound. Mother asks her if she would like some of the containers to fill up? Mother finds several different sized plastic cups and containers and places them in the sink beside Katie’s feet. She facilitates the space by removing some of the more breakable cups and items around the sink. On seeing this Katie makes a protesting sound and she looks very displeased but is quickly reassured when Mother explains to her that they might break and that she has other cups that she can use.

Surveying the sink’s contents with a look of delight on her face, Katie solidly and deliberately turns on the tap with her right hand. Mother looks up at me and laughs in proud delight. Mother then turns to preparing dinner at the stove a few feet away from Katie.

With the tap turned on, Katie curls and stretches her toes repeatedly as the water gushes over her feet and legs. She almost seems to have the look of sitting on the shore with the waves lapping deliciously at her feet. Lifting her head up she smiles a toothy grin and giggles. Mother smiles back at her and asks if she is having a good time. Leaning forward, Katie picks up a red beaker and fills it up with water. She watches it carefully as it fills and then using both hands, places it on the side counter, all the while sticking her tongue out to the side in quiet concentration. She then takes each cup and beaker in the sink, carefully fills it up with water and places it on the counter, right next to Mother who is watching her while she cooks. Occasionally, she looks up at Mother to see what she is doing or for possible reassurance. It seems like Katie is playing at making tea. The space next to Katie is filling up with cups of ‘tea’ and Mother helps Katie by making more space on the counter top. After a while and with some effort Katie manages to turn the tap off using her right hand. Looking at Mother she says ‘down’ and Mother asks her if she would like to go down now. Katie nods and Mother brings over a tea towel to dry her hands and feet. Katie then lifts up her arms and Mother picks her up and places her on the ground, where she quickly clings onto mum’s legs and begins a game of peek-a-boo with mum.

Data analysis 2

The most striking fact observed in this situation is the degree of relaxed facilitation that Mother shows towards Katie in allowing her to sit with her bare feet inside the sink to play and be messy in the kitchen. Mother’s unusual alacrity in allowing Katie to be ‘messy’ and in charge of the water on the kitchen counter, seems possible, like with the play with the cloth, only after Mother first has an experience of control in the kitchen herself. Additionally, Katie’s masterful turning on (and later off) of the taps can be linked to Katie’s earlier attempt to supplement the feed by the substitution of her fingers for the nipple. Here there is evidence of Katie’s normal development, as she seems to be able to work through and gain integration of this experience through a more symbolic relationship with the taps. She is also able to acknowledge the actual properties of the water and the taps, which can be used for pretend games.

With the water lapping against her feet in an enjoyable way, Katie seems to recreate in the kitchen an experience of her recent holiday. By creating a ‘sea side scene’ within the sink, she is able to share an experience with Mother, who takes much delight in her daughter’s enjoyment of this lived-out-memory. It seems important to note here that mother and daughter seem to be in joint attention to the representation of a past experience. Katie and Mother seem to be displaying joint attention to an experience of absent realities, suggesting a capacity to tolerate the loss of an enjoyable experience of the holiday.

Katie, like Andrew, also fills up containers with water; however, there is a significant difference in her use. Katie manages to give the water an ‘as if’ quality, lifting her behaviour up into the world of play and pretend. The plastic containers become ‘teacups’ and the water functions as ‘pretend tea’. Additionally, as Katie prepares the ‘tea’, Mother prepares the evening meal on the cooker adjacent to the sink. It can be inferred here that Katie’s capacity for symbolic play is linked to her identification with a good feeding mother. Mother’s receptivity and understanding of Katie’s use of water in the containers as a pretend game helps Katie use the water symbolically as it becomes an experience, which they both can share and take mutual delight in.

Katie’s social referencing of looking up occasionally to see if Mother is aware of what she is doing, or drawing Mother’s attention to what she is doing, suggests that Katie has a solid theory of Mother’s mind. By keeping Katie in the back of her mind while at the same time continuing to cook, Mother displays the capacity for ‘two tracked thinking’ (Alvarez & Furgiuele, Citation1997, p. 125). This enables Katie to identify with Mother’s capacity for multi-tasking, in the sense of being able to think about more than one thing at a time, which is a necessary prerequisite for symbolism. Alvarez & Furgiuele goes on to suggest that the infant may also experience agency when having an experience of a caregiver who can step aside and wait with interest while the baby’s attention is elsewhere (Alvarez & Furgiuele, Citation1997, p. 125). Both Mother and Katie in the above extract experience each other as being in the back of each other’s minds as they get on with their primary interest. Katie here must also have an experience of Mother waiting for her while she plays with the water. This can be seen when Mother and Katie make eye contact when Mother sees Katie looking up from her play every now and then. This capacity to ‘think in parentheses’ (Alvarez & Furgiuele, Citation1997, p. 125), which is the ability to manage two or more trains of thought at the same time, similar to that of joint attention, provides the infant with the mechanisms for symbolic thinking, contributing to the ordinary development of the mind in the world.

Results

From the above comparison it is possible to consider that both Andrew and Katie can be located on a symbol-formation continuum: on one end there is a position of fusion with the water, where there is no symbol formation; on the other end there is a position of separateness, where relating is more symbolic. This suggests the need to consider whether the water is being used to obliterate differences between self and other, as can be seen with Andrew, or as a means of communication, in spite of differences, as can be seen with Katie. Although there is no way of gaining early observational material of Andrew it can be speculated that his developmental pathway from the start was very different to that of Katie. Despite struggling at the breast, Katie was able to connect up to, and identify with, a mother who could shape, regulate and create a multitude of experiences with her, placing her on a developmental trajectory where she can develop the capacity to use the water symbolically. Pertinently, the comparison brings to the fore the vexed question of the timing of the infant’s first experience of sense of difference and therefore sense of separation.

Following a Winnicottian tradition (Winnicott, Citation2009), it may be argued that the infant achieves a sense of self from their initial experience of being fused with their mother. It is possible to speculate that at the start of life the infant experiences transmodal perception where there is little distinction between self and other. As a result of an attuned experience with mother (Stern, Citation1985), the encounter is not only transmodal but transpersonal, resulting in the confluence of two people into one perception. This suggests that what is relevant is not the distinction of who is having the feeling, but rather that the infant has an experience of a shared feeling state with their mother in the first place. Following from this, the infant may experience the slow disillusionment in which difference is gradually apprehended (Winnicott, Citation2009). This suggests the primacy of a shared emotional experience out of which differentiation may emerge with the potential for dyadic and then, triadic relating.

A good example of the clinical relevance of this idea is when Andrew is able to have a shared experience with me. From this he is able to show something of his identification with a human object, which arguably develops his capacity to say ‘bye-bye’, promoting greater connection. This seems a more productive identification with a live object, rather than in a difficult and fused identification with the sink, which generates limited behaviour. It seems for Andrew that difference is very difficult to tolerate, and water, which is first experienced within the womb, is used to confirm a perception of sameness. Possibly for Katie her experience of difference could be tolerated and initiates in her a rudimentary capacity to begin to see other minds, and sets her on the developmental path towards symbol formation. As a result, she is able to recreate a shared memory in her playful use of water.

Discussion

The intersection of infant observation and art therapy in this paper has brought to the fore the space between the young person and the material where there is a transformation from water to words. Andrew’s capacity to say ‘bye-bye’ at the end of the session can be seen as a culmination of his momentary shift from being in a fused relationship with the sink, to being more relational with myself, a live human being. It is possible to speculate that at the moment he identifies with my mouth, he is able to use his mouth to generate words, which are meaningful to both of us. Andrew can engage in symbolic relating at the moment when he manages to be in relation to, and in identification with, a human mind. Consequently, Andrew at this moment must be able to construct a theory that I too have a mind, with which to communicate and with which he has a desire to share (Baron-Cohen et al., Citation1985; Hobson, Citation2002).

Katie, who has reached a greater and more stable degree of self-other differentiation, uses the sound ‘kaah’ to refer to the cup and is able to point to the taps and exclaims ‘mummy, mummy!’ Katie knows that Mother’s gaze will follow her pointing and that she will deduce from this that Katie would like to play with the water. This clearly shows that Katie can experience secondary intersubjectivity (Trevarthen, Citation1979) with her Mother, enabling her to develop joint attention skills. This in turn reveals that Katie has been able to develop a theory of mind from which she can identify other minds, which can confer meaning onto objects rather than meaning being intrinsic to the object itself. She can take on a different perspective and use words to communicate this shared understanding (Hobson, Citation2002).

It is now possible to explore how the repeated experience of triangular ways of looking on the outside, becomes internalised as a structure of the mind on the inside, scaffolding the capacity for symbolic thinking and reflexivity. To begin to understand this further, it is first necessary to briefly unpack what is meant by a symbol. The area of semiotics – the study of signs – finds its contemporary theoretical base in the work of Saussure and Peirce (See Yakin & Totu, Citation2014). While a semiotic discussion is outside the scope of this paper, it can be argued that in its simplest form a symbol stands in for, or refers to, something else. The term ‘referent’ is just right as this ‘points to’ what it stands in for. The capacity for symbol formation requires holding two things in mind at the same time as they involve the alternating attention to its concrete dimension while simultaneously ‘keeping an eye on’ an additional meaning. This capacity for two-track thinking or holding two things simultaneously in mind, lifts the concrete material (water) into the symbolic (‘tea’). In this way, the capacity for joint attention is a prerequisite to the development of language, making visible the process in which the sound ‘water’–for example – refers to the liquid, transparent substance. Language is structurally predicated on joint attention where alternating attention is given to both sound and its referent. It is only when there is an absence of symbolism that the developmental difficulties resulting from the inability to relate triadically come to the fore.

Limitations of the study

As explored above, the significant limitation with hermeneutic infant observation is its over-reliance on the subjectivity of the observer. Both observational reports require the use of the self in the generation of data. This is further compounded by the time delay in observing and the subsequent ‘write-up’ which usually takes place immediately after the observational period. This lag may produce a kind of secondary revision of the data observed. The inevitability of subjectivity seeping into observations may be mitigated by the inclusion of researcher reflexivity in the development of qualitative data. The psychoanalyst Robert Wallerstein notes the personal dimension and bias in all forms of looking within the human sciences when he says:

All looking is contaminated by your perspective and you see through your own eyes. And somebody else, who has had a different life experience sees through different eyes. So there is no true objectivity but that’s a problem for all of science all the time, when you are dealing with human beings. (Wallerstein, Citation2015) (From Observation to Apres Coup) [Online Video]

An additional conception of how the observer’s subjectivity may inform understanding can be taken from Ogden’s notion of the analytic third, that is, a third subjectivity borne out of the ‘unique dialectic generated by /between the separate subjectivities of analyst and analysand within the analytic setting’ (Ogden, Citation2004). In infant observation and art psychotherapy, this co-production of what may be regarded as being akin to the analytic third, is also located in and informed by, the subjectivity of the observer or therapist. However, it is used in the service of understanding of the subject of observation or therapy, rather than for the observer themselves. As such, while the author’s subjectivity is acknowledged as important in meaning production, it is situated outside this paper.

Visual research can be considered to function on a positivist- hermeneutic spectrum with naturalistic infant observation being located towards the relativist end. As such, it is open to criticisms of not being able to provide ‘hard data’. However, as a qualitative method, it is productive at meaning generation that enables a 'thickening' of understanding, and which finds a correlate in the visual ways of knowing in art psychotherapy. ‘Thickening’ here refers to the anthropologist, Clifford Geertz’s (Citation1973) concept of thick description, which advocates a deeper exploration and understanding of meaning of signs within the broader patterning of social and cultural relationships.

Implications for practice/research

There are several implications for practice, research and training as a result of beginning to explore the intersection of triadic practices of looking within the two domains. Firstly, it suggests the fruitful inclusion of infant observation as a core component of all art psychotherapeutic trainings. The mutually informing methodological relationship between practices of looking in the respective fields opens up the potential to enrich art psychotherapy. However, the current exclusion of infant observation from many art psychotherapy trainings is also understandable in light of contemporary curriculum demands, which are already challenging to complete. Nonetheless, the potential pedagogic value at the intersection of infant observation with art psychotherapy has only just begun.

Secondly, this investigation has emergent implication for praxis where greater appreciation and attention may be given to the art psychotherapist’s capacity to look with ‘feeling and meaning’ (O’Shaughnessy, Citation1989). The art psychotherapy gaze is not just passive, rather, it is borne out of a therapeutic training that nurtures the capacity to stay with, and attune to, primitive states of mind, as well as to tolerate the emergent unknown. It is this capacity that is fostered both in infant observation (vis-à-vis the mother – baby dyad) and art psychotherapy training (vis-à-vis the art making process). Further, art psychotherapy provides an exemplary context for the generation of visual joint attention, potentially setting in motion a process whereby its structure is internalised within the service user, and – in virtuous cycles – promoting greater symbol formation and reflexivity.

A third implication for research is the understanding that the art therapeutic triangular relationship may be further conceptualised as spatial and temporal under the realm of the gaze. In regards to temporality, visual joint attention requires alternating attention, turn taking and reciprocity, which all have a temporal component. Spatially, it can be understood in regards to perspective and proximity of the art object and/or art therapist. If the service user is too close, then there is a danger of a fusion, resulting in the exclusion of the third. Similarly, if the service user is too far away, there can be an absence of emotional contact. Art psychotherapy can help regulate the temporal-spatial relationship by maintaining optimal ways of triadic relating for each unique service user, which allows for a flexibility within and between the different positions on the axis, whilst allowing for moments of dis/connection.

Fourthly, water is one of the most fundamental materials for art making. Its infinitely adaptive form may generate particular ways of relating to it. In doing so it may provide an external material space for the working through of emotional and developmental difficulties. The implications of working with the fluidity of water or other malleable materials in art psychotherapy therefore requires further examination.

Conclusion

It may be considered from the above observations that the use and function of water is dependent on whether it is being used in the service of object relating and development, or in the denial and avoidance of object relating (see Bierschenk, Citation2020, on the function of the art therapy object). The fascination with the fluidic and pliable quality of water can be understood to reside within ordinary sensuality, which Katie seems to demonstrate in her appreciation and enjoyment of its feel. This is vastly different from Andrew's use of the sensuality of water, which is often mind-killing, self-hypnotic and excluding. In sum, the comparison of the two children’s different uses of water has led to the investigation into the primary nature of relating.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alvarez, A. (1989). Ways of seeing: 1. Journal of Child Psychotherapy, 15(2), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/00754178908254842

- Alvarez, A. (1992). Live company: Psychoanalytic psychotherapy with autistic, borderline, deprived and abused children. Routledge.

- Alvarez, A. & Furgiuele, P. (1997). Speculations on components in the infant’s sense of agency: The sense of abundance and the capacity to think in parentheses. In S. Reid (Ed.), Developments in infant observation: The Tavistock model (pp. 113–139). Routledge.

- Baron-Cohen, S., Leslie, A. M., & Frith, U. (1985). Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind”? Cognition, 21(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(85)90022-8

- Bick, E. (1964). Notes on infant observation in psychoanalytic training. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 45, 558–574.

- Bierschenk, L. (2020). The function of the art object: Art-psychotherapy theory and practice. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 34(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/02668734.2020.1750053

- Bion, W. (1962). A theory of thinking. The International Journal of Psycho-analysis, 43, 306.

- Butterworth, G. (1991). The ontogeny and phytogeny of joint visual attention. In A. Whiten (Ed.), Natural theories of mind: Evolution, development, and simulation of everyday mindreading (pp. 223–232). Blackwell.

- Case, C. (1990, Winter). The triangular relationship (3) the image as metaphor. Inscape, 20–26.

- Case, C. (2011). Our lady of the queen. In A. Gilroy & G. Mc Neilly (Eds.), The changing shape of art therapy: New developments in theory and practice (pp. 15–54). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Corkum, V. & Moore, C. (1998). The origins of joint visual attention in infants. Developmental Psychology, 34(1), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.34.1.28

- Damarell, B. (1999). Just forging, or seeking love and approval? An investigation into the phenomenon of the forged art object and the copied picture in art therapy involving people with learning disabilities. Inscape, 4(2), 44–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454839908413076

- Elfer, P. (2006). Exploring children’s expressions of attachment in nursery. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 14(2), 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930285209931

- Fonagy, P. & Allison, E. (2014). The role of mentalizing and epistemic trust in the therapeutic relationship. Psychotherapy, 51(3), 372. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036505

- Franks, M. & Whitaker, R. (2007, June). The image, mentalization and group art psychotherapy. International Journal of Art Therapy: Inscape, 12(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454830701265188

- Geertz, C. (1973). Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Cultures. Basic Books.

- Hinshelwood, R. D., Skogstad, W., Hinshelwood, R. D., & Skogstad, W. (2002). Observing organisations: Anxiety, defence and culture in health care. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203135150

- Hobson, P. (2002). The cradle of thought. Macmillan.

- Isserow, J. (2008). Looking together: Joint attention in art therapy. International Journal of Art Therapy. 13(1), 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454830802002894

- Isserow, J. (2013). Between water and words: Reflective self-awareness and symbol formation in art therapy. International Journal of Art Therapy, 18(3), 122–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2013.786107

- Leuzinger-Bohleber, M. & Fischmann, T. (2006). What is conceptual research in psychoanalysis? 1. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 87(5), 1355–1386. https://doi.org/10.1516/73MU-E53N-D1EE-1Q8L

- Maiello, S. (2007). Containment and differentiation: Notes on the observer’s maternal and paternal function. Infant Observation, 10(1), 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698030701234715

- Mann, D. (1997). Masturbation and painting. In Killick (Ed.), Art, psychotherapy and psychosis (pp. 64–70). Routledge.

- McLeod, J. (2010). Case study research in counselling and psychotherapy. Sage Publications.

- Ogden, T. (2004). The Analytic Third: Implications for Psychoanalytic Theory and Technique. The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 73(1), 167–195. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2167-4086.2004.tb00156.x

- O’Shaughnessy, E. (1989). Ways of seeing: 3. Seeing with meaning and emotion. Journal of Child Psychotherapy, 15(2), 27–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00754178908254844

- Radley, S. (2018). The contribution of infant observation to art therapy in private practice. In J. D. West (Ed.), Art therapy in private practice (pp. 131–151). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Rustin, M. (2009). Esther Bick’s legacy of infant observation at the Tavistock—some reflections 60 years on. Infant Observation, 12(1), 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698030902731691

- Scaife, M. & Brunner, J. S. (1975). The capacity for joint visual attention in the infant. Nature, 253(5489), 265–266. https://doi.org/10.1038/253265a0

- Schaverien, J. (2000). The triangular relationship and the aesthetic countertransference in analytical art psychotherapy. In A. Gilroy & G. McNeilly (Eds.), The changing shape of art therapy: New developments in theory and practise (p. 55–83). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Segal, H. (1957). Notes on symbol formation. International Journal of Psychoanalysis 38, 391–397.

- Shuttleworth, J. (2012). Infant observation, ethnography and social anthropology. In C. Urwin & J. Sternberg (Eds.), Infant observation and research emotional processes in everyday lives (pp. 171–180). Routledge.

- Siegel, L. (2011). A mother learns to enjoy her baby: Parent-infant psychotherapy and art therapy in the treatment of intergenerational separation-individuation struggles. Infant Observation, 14(1), 61–74.

- Skogstad, W. (2004). Psychoanalytic observation–the mind as research instrument. Organisational and Social Dynamics, 4(1), 67–87.

- Stern, D. N. (1985). The interpersonal world of the infant. Basic Books.

- Stern, D. N. (2004). The first relationship: Infant and mother. Harvard University Press.

- Sternberg, J. (2018). Infant observation at the heart of training. Routledge.

- Trevarthen, C. (1979). Communication and co-operation in early infancy: A description of primary intersubjectivity. In M. Bullowa (Ed.), Before speech. The beginnings of interpersonal communication (pp. 321–348). Cambridge University Press.

- Waller, D. & Dalley, T. (1992). Art therapy: A theoretical perspective. In Art therapy: A handbook (pp. 3–24).

- Wallerstein, R. S. (2015). From observation to Apres Coup. [Online]. Retrieved November 6, 2016, from http://www.pep-web.org/document.php?id=pepgrantvs.001.0006a

- Winnicott, D. W. (2009). Winnicott on the child. Da Capo Lifelong Books.

- Wood, C. (1990, Winter). The triangular relationship (1): The beginnings and the endings of art therapy. Inscape: Journal of Art Therapy, 713.

- Yakin, H. S. M. & Totu, A. (2014). The semiotic perspectives of Peirce and Saussure: A brief comparative study. Procedia-Social & Behavioral Sciences, 155, 4–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.10.247

- Zago, C. (2008). Coming into being through being seen: An exploration of how experiences of psychoanalytic observations of infants and young children can enhance ways of ‘seeing’ young people in art therapy. Infant Observation, 11(3), 315–332.