Abstract

Psychotherapy has been practised via remote technology since the mid-1990s and has grown in mainstream popularity; yet, it remains controversial, particularly for psychoanalytically informed treatment, and limited research in this area has been published. However, COVID-19 provoked a necessary transition to online working across the psychotherapy profession, including clinicians providing psychoanalytic treatment to a unique forensic outpatient group remotely for the first time. This qualitative research study sought insights from this sample via grounded theory interviews and analysis to inform hypothetical future practice of remote psychotherapy via videoconferencing to forensic populations with limited access to treatment. This generated a substantive theory about how forensic psychotherapy works remotely: In the context of a forced transition to remote working, forensic psychotherapists make attempts to substitute for real by establishing an alternative frame; noticing how differently contact is mediated; adapting technique; and evaluating suitability for remote treatment. An implication of these findings may be that developing a new Virtual Frame for forensic psychotherapy, supported by specialist training and supervision, could increase its reach within settings that provide sufficient containment for the work. Further research is encouraged to support this undertaking and consider which patients, and/or clinicians, might work effectively this way.

Introduction

Reviewing the literature has shown that online therapy was relatively commonplace for several years before COVID-19, since the world’s first online clinical counselling service was founded in 1995 (Murphy et al., Citation2009) and there is a small body of research on this mode of practice, to which recent studies refer (Fisher et al., Citation2020). Many quantitative studies evaluated effectiveness of online counselling and CBT, but very few studies considered the process of treatment, with only 1.3% investigating the therapeutic alliance (Kortz, Citation2017; Machado et al., Citation2016). Further research was evidently required into providing longer-term psychotherapy online, for approaches where the therapeutic relationship is primary.

The pandemic shifted the landscape for remote video psychotherapy significantly and many professionals experimented with the use of technology for the first time, including The Portman Clinic’s highly specialist psychoanalytic psychotherapists working with a forensic patient group. No research has ever been undertaken into clinicians working psychoanalytically with forensic patients remotely and this study offered a unique opportunity to explore their experiences of this new way of working. Research into service-delivery under stress may generate important knowledge to improve delivery of any planned future remote psychotherapy for this patient group.

The aim of the study was to gain specific insights into psychotherapy with a forensic patient group when practised online via videoconference technology, to inform the training and supervision of psychoanalytic clinicians working remotely. It is hoped that sharing findings with a wider community of professionals may inform best practice in this new way of working and highlight the potential it may offer to increase access to this specialist forensic treatment.

Method

Design

The chief concern of the research design was the usefulness of its outputs for future practice, which may be enhanced by a degree of commonality among participants, should this legitimately be found. However, the researcher’s emphasis was on the qualitative exploration of phenomena encountered by clinicians doing this kind of work.

A priority audience for the study’s findings is The Portman Clinic, who are keen to learn more about the service they provide. McPherson et al. (Citation2018) maintain that any credible contribution to NHS body of knowledge must be undertaken in accordance with prevailing positivist standards, lest it be disregarded by its reviewers, who may yet to have fully adopted a pragmatic attitude towards epistemology (Greenwood, Citation2010). However, as an entirely novel practice of psychotherapy, with no extant theory to use as a hypothesis, an explorative methodology seeking to discover new theoretical possibilities was required.

For this most practical of research subjects, the researcher drew upon the epistemological paradigm of pragmatism as a basis for acquiring knowledge to inform clinical practice. Central to pragmatic inquiry is the use of abductive reasoning, which is privileged by Glaser and Strauss (Citation1967) in their Classical Grounded Theory method, which seeks a plausible explanation from a set of observations that can subsequently be tested further through hypotheses. Birks and Mills (Citation2015) guided the practical application of this method and ethical approval for the study was granted by Brighton University.

Participants

The population under study are forensic psychotherapists employed by The Portman Clinic, of which nine fully qualified clinicians met the sampling criteria of having recent experience, during the last two years, in practising with forensic patients both face-to-face and online.

Recruitment for participants was undertaken via clinic-distributed email, and initial purposive sampling of the first three volunteers was followed by theoretical sampling of two further participants. The selection of these participants was informed by the data analysis of the first interviews, in line with the method, which indicated a) that there may be particular phenomena arising within therapy groups and b) that clinicians who practice psychoanalysis may experience specific dimensions of process that could be helpful in defining the emerging conceptual categories. The two additional participants were both practising psychoanalysts, who also facilitated psychotherapy groups at The Portman Clinic before, during and after the pandemic.

Procedure

The primary data source was semi-structured interviews, with further data gathered from a quantitative service audit, undertaken by The Portman Clinic’s Research Team (Rubitel & Miller, Citation2022), and from a systematic literature review completed after initial analysis. A detailed exposition of this is beyond the scope of this paper, however some references have been incorporated within the discussion.

Each 60-minute interview was scheduled, conducted and recorded in a confidential setting, and then manually transcribed by the researcher. Some interviews were conducted in person, others via Zoom, to incorporate the duality of modes under study within the research itself.

The central research question How does forensic psychotherapy work remotely? is deliberately framed to allow participants to respond to the word work in their own way, allowing for both positive and negative reactions amongst participants, some of whom may have challenged the idea that therapy can work at all when carried out in this way. Each interview was structured only inasmuch as it opened with the ‘spill question’ (Nathaniel, Citation2008): ‘How have you found working online with forensic patients via Zoom?’ which provided the freedom to allow emerging themes to be explored as they arose.

Data analysis

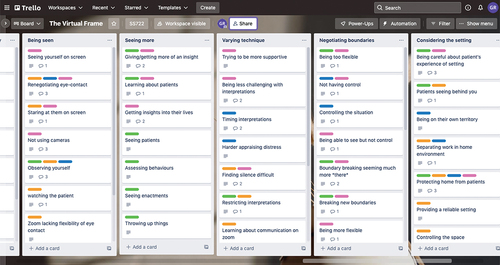

Data analysis was carried out continuously by constant comparison, from coding the first interview through to final incorporation of data from the literature search. This was supported by reflexive memoing throughout. In line with the technology-centric research area, a digital platform – Trello, as shown in – was used to record and analyse the data, using coloured labels to identify the participant data source whilst anonymising the data at the same time: Dr Pink, Dr Blue, Dr Green, Dr Purple, Dr Orange.

Results

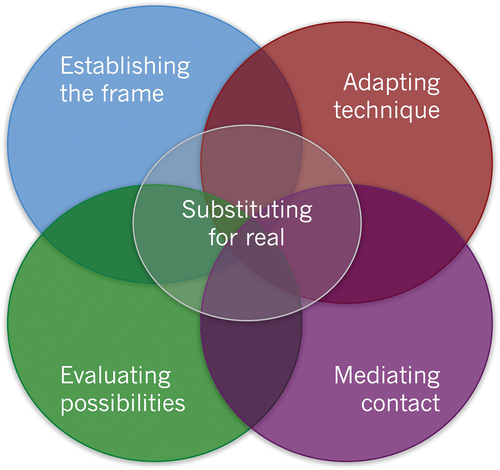

Of the several hundred codes analysed, conceptualised and categorised, a small selection of the verbatim comments from the interviews is reproduced here to illustrate the four saturated categories that emerged from the fieldwork and secondary data analysis. Together, these form a basis for a substantive theory for this research area and they are summarised in , with further details below.

Table 1. Saturated categories defined by their dimensions.

Establishing the frame

Preserving significance

There was a universal sense that the unique significance that forensic psychotherapy requires is compromised by working remotely.

there’s something also just about the the therapy itself becomes less distinguished as an event for a person

The instantaneous accessing of an online space meant that patients were missing the time needed to journey to and from the clinic and the processing of feelings that takes place with that transition.

such an incredibly valuable time and so full of feelings you know the feeling of not wanting to go [laughs] that you have to work with for the length of the journey rather than the ten minutes it takes to set up the zoom um yeah and a lot of the resonance of what comes comes afterwards

With the normalising effects of the Zoom platform being used during the pandemic, by clinicians and patients alike, for myriad other purposes, therapy blended in and lost vital significance through a lack of differentiation from things outside its frame. Particularly the transference significance that the therapist can draw for the patient, as just another person to be seen on screen.

it’s the power of transference and um how you can actually sort of … the significance that you take on for the patient. And I think inevitably it becomes degraded by teletherapy. Er you’re less potent as a transference object. Um you draw less you draw less significance, right.

Several clinicians highlighted a need to normalise things during COVID, leading them to believe in a substitute, illusory experience of real significance. only recovering awareness of the absent immediacy and contact when returning to the clinic.

it might sound obvious what I’m saying but it sort of took me by surprise. How I guess how much more real it was or vivid or … stays in your mind more.

Sharing responsibility

One of the greatest concerns shared by clinicians was the lack of control over the therapeutic setting. Trusting this patient group to maintain responsibility for their side of the frame was anxiety-inducing, with confidentiality breaches and uncertainty around appropriate limits to flexibility.

when you’ve got control of the setting then you have a kind of stable mirror, if you like. Whereas if you’re bequeathing that to the patient then the mirror is sort of constantly being distorted

Where patients were unable to maintain a consistent frame, it was more difficult to interpret this psychoanalytically, given the context of real-life practical constraints on accessing private space.

there might be other people in the house and it’s quite difficult. And actually you might need to do it in your car because there’s nowhere else to do it.

Though there was understanding about why some patients may turn off cameras, being able to see the patient became the sine qua non of Zoom therapy. There were advantages of some patients being on their own territory and some clinicians gained surprising insights by seeing into their lives more.

‘they’re sort of showing you something aren’t they? Um … er … you know another guy would sort of show a sort of quite clearly show us his book collection, you know’.

However, there was a counter-preoccupation with revealing the therapist’s private space and considering what the patient would make of what they were able to see in return.

‘because I really didn’t want patient … particularly this sort of patient … I really did not want them having a having an insight into my home at all’.

Protecting ourselves

Clinicians expressed a strong sense of both intrusion and exposure and a need for protection, when having to invite these patients virtually into their homes. This was particularly relevant for more perverse patients, who may triumph at entering the therapist’s private space as a breach of boundary.

I think I find it very hard to find the frame. Actually. Or a frame that feels protective. For me.

It was therefore important to create a separate space for work, to process difficult material without it contaminating the rest of the clinician’s home life.

making like so a definite work area and stuff that’s to do with work only in a certain area and have kind of quite symbolic ways of stopping and going and not being at work

Yet there was an acknowledgement that the instinct to protect oneself risked engendering a distancing response in the therapist.

that’s the risk of being distant virtually because it’s a way of protecting yourself from that again.

Containing the work

Perhaps the most strongly felt impediment to working remotely with this patient group was the lack of containment for the work. Initially, this manifested in the clinician feeling anxiously unheld in the absence of the ‘brick mother’ (Rey, Citation1994), which represents a place of physical and psychic safety for patients and therapists.

being actually physically with colleagues. And the running, the containment of the clinic. Because it all feels … it’s not quite all fitting together because we’re all kind of virtual

However, as remote working continued, adaptations to process restored some analytic containment and the possibility of working this way increased clinicians’ confidence and comfort.

tried to kind of recreate as many of the distancing elements of the treatment as possible. So you only get admin to speak with them, email them. If there’s a problem it has to go through admin.

It was acknowledged that, although video provided more cues for holding patients than the telephone, it also revealed more to them when clinicians felt helpless in dealing with the technological and clinical challenges arising from the new way of working. Therefore, it was difficult to have confidence in containing patients via the screen, particularly those who struggle with regulating aggression or present with high risk.

I think the less contained we seem to them, the more uncontained they feel. And I think it can escalate things

Mediating contact

Patient regulating contact

Interestingly, within therapy groups attendance increased for some and declined for others, when transitioning to video sessions. Meeting online offered more opportunities for patients to moderate the intensity of contact, either by using distractions or discretely pausing their group participation by switching off cameras.

one of the guys said in the assessment that you know ‘It’s a lot easier just to switch off your camera and go and get a cup of tea or have a fag and calm down’ but if you walk, storm out of a room group and then you have to make a re-entry that’s a far far more complicated in terms of things the sort of humiliation what have you.

Instantaneous termination of contact could be more easily achieved for some patients, with the press of a button, whereas others were felt to spend a lot of time getting rid of the therapist after sessions.

actually he told me he cleaned the flat before we talked but actually my fantasy was that there was a lot of cleaning that went on afterwards to get rid of me [laughs]. In a way. Um but with a lot of sadness because he would have liked I think to be kind of close. But he couldn’t tolerate it

A perceived comfortable distance assuaged ‘core complex’ anxieties (Glasser, Citation1979) of being engulfed or abandoned, potentially reducing shame and facilitating progress. However, a new mode of abandonment was easily overlooked, as some patients quietly receded into increasing remoteness in groups.

I guess a comfortable a comfortable distance can so easily flip I think with these patients into feeling abandoned or unattended to

Obstructing contact

Initial complications and frustrations around technology were keenly felt but became less obstructive with growing familiarity. However, problems with internet, audio and cameras continued to impede connection.

so there’s something about finding your way through frustration in terms of modelling, just pure modelling the technology.

A particular concern was the difficulty discerning how intentional these problems were, on the part of the patient.

that really did happen you know whether whether it was sort of accidental, or whether the patient is you know is sort of turning it off or something

An enduring and universal issue was the paradox of false intimacy: a close-up face on screen seeming closer and more intense, while masking a lack of real availability and presence on the part of the therapist, who might risk unconscious collusion in avoidance.

It’s like closeness at a distance. Er … you know it’s a kind of false intimacy in a way …

Missing dimensions of contact

The pandemic left some clinicians professionally bereft of the irreplaceable human comfort of real-life contact, which could not be replicated.

I mean it’s just you know again it’s just like a two-dimensional space versus three-dimensional. Seems less room for for a I guess a contact.

Psychoanalyst participants especially perceived a loss of unconscious contact, resulting sometimes in banal or superficial interactions or working at the level of the ego.

‘Because the nature of human interaction is so complex and so much of it is unconscious … um … that you don’t know what you miss until it’s sort of gone’.

Adapting technique

Seeing & being seen

Participants differed in how confident they were in perceiving emotional states accurately. Some said this was harder to trust than it would be in the room, others saying that being close-up on screen was beneficial and there were more cues over video. However, limitations on assessing non-verbal communication and accurately observing appearance and behaviours were frequently highlighted.

it’s amazing the level of emotional cues you can pick up by observing someone’s face close up. I mean that’s one advantage isn’t it that you can really see the patient? In some ways. What you don’t see is their fidgety fingers or their tapping toes or you know their crossing legs or whatever

Camera positions made replicating natural eye contact difficult, and the absence of common objects in a shared space on which to focus left some clinicians with a sense of a binary choice between staring or looking away. Many spoke of being distracted by seeing themselves on screen, with some turning this view off but others wanting to see what the patient can see, especially during assessments.

in an assessment I will make sure I can see my face because then I because I don’t know the patient’s face so so well but I find it distracting to see my face um you know it’s not something I usually have to do during my day

Some participants felt that they were more present and attentive working on screen, whereas another felt less available. More difficult to articulate was the distorting effect of the screen and how it somehow gets in the way, although this also sometimes generated useful material.

so much gets in the way in terms of zoom. And what gets in the way like I say with time is all could be grist for the mill and probably very profitable to think about.

Doing things differently

Rapid learning was necessary to understand how technology was mediating interactions and new ways it could be used effectively by clinicians, especially when facilitating groups.

you may be picking up a sense of somebody feeling very excluded who actually to me looks like they’re right next to me on my screen. And it took me a long time to understand that our screens are showing us different configurations of people but it’s quite important.

There were significant contrasts in how clinicians perceived changes in their approach to the work. Some admitted to becoming lazier, and others feared lapses in professionalism with the disinhibiting effects of remote working. Conversely, an inclination to work harder to engage and be more supportive was expressed, although this was tempered with caution about colluding with patients.

I think in some regards you do have to work a bit harder to to sort of get through the screen as as if you know er … to sort of engage the patient. There is that um … but you’ve got to be very careful when doing that with this patient group, you know

Many clinicians felt less able to challenge or use silence and transference interpretations appropriately, with the latter becoming more tentative and structured differently.

how challenging can you be in your interpretations? You know are you less challenging than in person?

Timing of interpretations was more difficult to judge, as was the ability of patients to use them as intended. Likewise, interpretations of enactments were more complicated.

if we rely – especially with these patients – on interpretation of enactments as a crucial part of the work, and the enactments are very tied up with the limitations of reality, your hands are tied behind your back

Some clinicians did find ways to recreate the analytic situation and maintain the heat of interactions, while others foreclosed this possibility.

I’ve got a patient who puts the telephone behind them. So I see the. I see them. Er on the couch, on their own couch. Er so it’s possible to do analytic work like that.

Negotiating boundaries

Changing the frame provoked anxiety and increased obvious testing of boundaries in order to seek containment, which provided opportunities to learn more about patients. Clinicians differed in their judgements about what new boundaries could and should be established and how possible it was to discern when these were being tested.

We’re trying to work out a technical problem together. I mean it really compromises the boundaries that you would normally keep. And I think that’s disturbing for both parties

Boundaries had to be reconsidered because patients could do new things they had not done in the clinic and no existing rules governed these behaviours. Anti-social patients found new boundaries to break with use of phones and smoking substances, and many brought hot drinks to sessions.

it was very difficult to take these things up because when the boundaries aren’t as clear in your mind as a clinician, it’s much harder to first of all know what they are and second to reinforce them because I guess we were in a period of thinking, trying to think together as a clinical team: ‘well what is acceptable and what’s not?’

Interventions equally varied, with some allowing breaches; others confronting them; many interpreting them; but all having to make decisions in the moment. A general consensus prevailed that greater flexibility was needed to allow contact and acknowledge the patients’ autonomy in their own environment.

it becomes necessary to allow certain things that you wouldn’t otherwise and then their sort of antisocial traits come out, you know like … smoking in a session even. Like we wouldn’t have smoking in the room. But if it’s their space then we can’t control that

Working with enactment

Although enactments were not mentioned by all participants, many highlighted how technology offered new ways for this patient group to act out, especially when the clinic provided equipment. Joining sessions from inappropriate locations, or under the influence of substances, provided new insights. Using video presented more opportunities for visual enactment, such as inappropriate self-exposure, but the limits of screen-view and camera-control equally facilitated covert behaviours.

whatever the enactment might be: sitting off camera, sabotaging the technology, it’s understandable that this way of working you know video working is very anxiety provoking for for the patient

Enactments were often used as a way to attack, disrupt or denigrate the therapy, or to display contempt, such as by viewing online pornography or using the toilet during sessions.

of course it was a complete enactment in terms of his you know anality. And you know the kind of significance of being in the toilet literally and what that means you know the contempt.

Although some of the significant examples of acting out were obvious, it was more difficult to get a purchase on these remotely as they differed from the clinic experience.

And that’s the point is that you want to have that in the room where you can apprehend that and you know gather it up.

Acknowledging limitations

All clinicians described restrictions on their practice, in varying dimensions. Zoom fatigue was associated with a holding back of instincts; restricted freedom of movement, and a deadening effect of on-screen working, making reverie more elusive.

Zoom is exhausting um and that’s partly why it’s exhausting because you’re holding back so much of your kind of instinct um because it comes from somewhere else

There were divergent opinions about how transference is impacted, with some participants maintaining that the level of emotional traffic transferred well onto screen, whereas others felt that transference was less potent.

‘I felt that I was developing a countertransference to these patients. Certainly the assessment. So being on a screen didn’t in any way mean that there wasn’t that level of emotional traffic happening’.

However, the significance of physical and bodily presence and countertransference could not be replicated remotely. Not knowing how patients would be positioning themselves and using a shared space was felt to be a significant loss by clinicians.

I guess because of um the sort of bodily presence then you’re more attuned to a bodily countertransference. Maybe even a you know a alive in the room. You’re more aware I guess of the complexity of the of your countertransference

Evaluating possibilities

Assessing suitability

Participants carefully evaluated how possible remote working was for different patients, with some managing to replicate in-person therapy and others losing too much, hiding in groups, or struggling with technology.

I think some people er it lends itself better than others. Actually. Like it’s more possible to approximate er the in-person thing er whereas other people there’s too much lost.

Participants recognised the significance of inviting patients to use the same means for therapy as they use for offending, in terms of both erotising equipment and fear of vengeance via the device.

I think it’s really important to bear in mind that you might be seeing the patient on the same piece of equipment that they use for inordinate amount of pornographic activity.

Some paranoid patients felt unable to tolerate the therapist’s intrusion into their homes and minds. Whereas core complex (Glasser, Citation1979) anxieties may incline other patients towards working at a distance, when this may not necessarily be appropriate.

there’s something very particular about this patient group which I think teletherapy um kind of almost. it suits them. Because it’s kind of becomes a safety strategy. You can do it at a distance.

Accessing treatment

The Portman Clinic’s clinicians recognised that offering remote therapy could provide an opportunity for more patients to access this national service, as most referrals are currently from London.

some travel a long distance to come here but now we’re online people can access therapy online

However, they recognised that forensic patients from lower economic groups may not have a laptop or smartphone. Difficulties with internet access prevented some patients from joining by Zoom, so some therapy groups mixed phone and video channels, with difficulty.

‘Zoom has proved either impossible because of restrictions on their use of the internet um or they have opted against it um or we’ve tried it and it hasn’t really worked’.

Although some paedophile therapy group patients did have restrictions on their use of internet, there was speculation that patients may claim this defensively, so clinicians might explore with police and offer to provide secure equipment.

Shifting between modes

According to the service evaluation (Rubitel & Miller, Citation2022), patients appreciated working online as a temporary pandemic solution and clinicians considered potential merits of hybrid working.

I think a mixed practice is better, like if somebody is to attend on zoom, it’s better for them to sometimes have a session in person.

Clinicians felt some in-person working was important to address attachment disorders and to fully experience the patient’s physicality. Some felt that patients and clinicians might adapt to changing from one mode to another, although maintaining the frame was an important consideration and caution was raised about the constant state of loss inherent in switching between settings.

some therapists think you should always keep the frame, so if you’re working on zoom you’re working on zoom. At least with him it made me think there’s real value to just meeting the patient once.

Participants also recognised the perception of rejection that both offering and revoking Zoom contact might engender. Some attendance difficulties arose when inviting patients to return to the clinic after working online, either due to intensity or inconvenience.

since we’ve been back in person his attendance has really dropped. And it was difficult to explore because he’s he’s got quite a serious physical illness so he often uses that as an excuse but … I don’t know whether it’s just too much seeing me again

Some participants identified patients who could be treated without any in-person contact, but occasional meeting was preferable, ideally at the beginning and end of treatment, but ending on Zoom warranted particular consideration.

ideally I think you’d meet the patient you know to begin with and then do it remote then meet the patient at the end

Gauging therapeutic progress

Participants vary on their evaluations of the effectiveness of remote therapy.

Can remote working be therapeutic in the sense can it cause any change? Er or is it just supportive? I mean I very much think it can be done. And you know that people can still make significant gains.

Some evidence of effective holding was offered, in that patients refrained from offending during treatment. Whereas a lack of holding was hypothesised as a cause of higher patient drop-out rates, which clinicians observed amongst patients accessing online treatment with the clinic’s trainee therapists. Remote working also made it more difficult to perceive pseudo progress with Borderline presentations.

you’re less likely to be able to pick up a patient who seems to be doing well but actually it’s all a bit sort of false-self

Generally, it was felt that some good work can be done, but something gets lost with remote working, which may limit progress. Ultimately, it was not considered by any clinician as a direct replacement for traditional treatment.

it feels like a a very second best really. Or second best is putting it a bit strongly actually. I think err err you know it’s really err err really degrades the therapy … possibilities

Core category: substituting for real

Although the above themes have each been explored separately, shows how these all intersect and contribute to a central core category of what’s going on in the case of the phenomenon under study (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967).

Throughout the analysis of the emerging categories, it became clear that attempts were being made by clinicians to adapt ways of working to try and offer the treatment they had been trained to provide for their patients, despite the changes in conditions.

I think you can very quickly be lulled into a belief that it’s actually it’s a kind of a substitute for real, rather than something almost entirely different.

It is this attempt to substitute something else for the ‘real work’ that all participants were struggling with. Each manifested this in their own way: with manic attempts to make technology work and manage risk; anxiously protecting vulnerable patients and therapists; denying difficulty by asserting that it works just as well; disillusioned mourning of something being lost; or a powerfully angry resistance to being obliged to do something that just felt wrong.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to explore the experience of psychodynamic clinicians working remotely with forensic patients, to gather knowledge that might inform any future service delivery using videoconferencing technology to improve access to this specialist treatment. To this end, the foregoing data must be assimilated and considered in the context of other sources of information provided by those working with relevant forensic populations, as well as data about working psychoanalytically using this technology.

How does Forensic Psychotherapy work remotely?

The findings of this study offer the substantive theory that, in the context of a forced transition to remote working, forensic psychotherapists made attempts to substitute for real with varying degrees of success that correlate with their personal feelings towards engaging in this work. In collaboration with their patients, they try to establish an appropriate frame to contain the work and preserve its significance, whilst protecting themselves. They notice how differently contact is mediated, with patients attempting to regulate connection, technology both enabling and obstructing it, and an irreplaceable loss of physicality and concomitant unconscious communication. They adapt their technique to make the most of new opportunities and mitigate challenges, doing things differently and acknowledging the limitations of this way of working. They evaluate what is and is not possible; which patients might experience benefit or detriment; and they consider the potential for offering a combination of in-person and virtual therapy where this could be helpful for those unable to access it otherwise.

However, it appears that offering forensic psychotherapy virtually is significantly different from practising it in person and therefore might be considered a specific discipline in its own right, rather than an adaptation of the real model. The data also indicate that remote forensic psychotherapy is not an equal substitute for in-clinic work.

This is at odds with the prominent voice for online therapy training, which asserts that all mainstream psychotherapy can be adapted to transfer online (Anthony & Nagel, Citation2020). However, there are converse arguments that remote therapy should be regarded as a distinct discipline, rather than simply a way of doing standard practice differently (Anthony, Citation2020; Smith et al., Citation2021).

How willing and able clinicians are to work with technology (Dominey et al., Citation2020; Kip et al., Citation2018; Kirschstein et al., Citation2021; Sturm et al., Citation2021), may have important implications for practice. If there is a pervasive reluctance in forensic settings to use technology (Kip et al., Citation2018; Kirschstein et al., Citation2021; Oncu & Balcioglu, Citation2021) and a similar resistance amongst psychoanalysts (Agar, Citation2020; Scharff, Citation2018; Symington, Citation2011; Velykodna & Tsyhanenko, Citation2021; Wanlass, Citation2019), it may follow that remote forensic psychotherapists are likely to be a rare breed. However, should forensic psychotherapy have a future online, some of the challenges raised in this study may benefit from further exploration.

Participants’ concerns about remotely containing patient risk are echoed in the literature (Anthony & Nagel, Citation2020; British Association of Counselling and Psychotherapy, Citation2021; Daffern et al., Citation2021; McGarry & Reeves, Citation2020; Oncu & Balcioglu, Citation2021; The Open University, Citation2020; Smith & Gillon, Citation2021; Vossler et al., Citation2021; Wanlass, Citation2019). However, levels of risk may be more possible to monitor and contain in secure settings, where access to dynamic insight-based psychological treatment is limited (Brettle, Citation2010; Towl, Citation2011), despite its effectiveness for forensic presentations (Elliott, Citation2011). Whilst general prison environments may not be suitable for patients to receive therapy that dismantles their defences (Bartlett, Citation2011), the necessary containment for intense work may be possible within specialist units, such as Psychologically Informed Progression Environments (PIPEs) and Long Term and High Security Estate (LTHSE) communities, which are designed with rehabilitative principles. Providing consistent containment for clinicians working remotely may still necessitate the provision of a clinic setting (Chong et al., Citation2021) from which to offer remote treatment and meaningful contact with colleagues. Maintaining the all-important ‘brick mother’ (Rey, Citation1994) safety for clinicians may reduce the risk of avoidance resulting from the sense of intrusion into home working environments expressed by this study’s participants and shared by forensic practitioners (Dominey et al., Citation2020; Sturm et al., Citation2021).

Making use of containing infrastructure within secure settings may also mitigate the important issue of surrendering power and responsibility for the setting, which is widely referenced (Lemma, Citation2017; Miermont-Schilton & Richard, Citation2020; Moller & Vossler, Citation2021; Norwood et al., Citation2018; The Open University, Citation2020; Simpson & Reid, Citation2014; Tao, Citation2018). Although the impact of a change in power balance may vary by analysand (Vincent et al., Citation2019), this seemed to be more critical for forensic psychotherapists, especially in the case of perverse patients for whom boundary violating is a defining characteristic – both in terms of their offending behaviour and their use of therapeutic interventions. By maintaining control over the psychoanalytic frame and observing and interpreting attempts to subvert it, the forensic psychotherapist can begin to understand these enactments and their unconscious origins with the patient, as a crucial element of the treatment (Aiyegbusi & Kelly, Citation2012; Motz, Citation2008).

The uncertainty around virtual boundaries and significance of the remote frame found in the present study is also highlighted in the literature (Anthony & Nagel, Citation2020, Miermont-Schilton & Richard, Citation2020; Music & Waterfall, Citation2020, Russell, Citation2018; Scharff, Citation2012; Tao, Citation2017, Citation2018; Treanor, Citation2017; Wanlass, Citation2019). However, both the loss of real-world boundaries (Holland, Citation1996, Miermont-Schilton & Richard, Citation2020; Padfield, Citation2021) and intrusions from external sources (Ahlquist & Yarns, Citation2022; Hendry, Citation2020) seem less problematic for other groups than for forensic psychotherapists, who may need more guidance on establishing and working effectively with new boundaries afforded by technology.

Whilst technology in forensic settings has been historically unreliable (Kirschstein et al., Citation2021; Oncu & Balcioglu, Citation2021), the widespread implementation of ‘purple visits’ (videoconferencing) during the pandemic may have sufficiently improved infrastructure and attitudes to allow mitigatons for some of the technological issues highlighted throughout psychotherapy literature (Drogin, Citation2020; Dunn & Wilson, Citation2020; Hendry, Citation2020; Oncu & Balcioglu, Citation2021; Russell, Citation2018; Scharff, Citation2018; Vincent et al., Citation2019; Vossler et al., Citation2021; Wanlass, Citation2019; Zoumpouli, Citation2021) and in this study. However, the nature of this technology may only realistically allow for individual interactions between a single patient and therapist, rather than facilitating group therapy. The present study highlighted that therapy groups vary in their effective use of remote treatment, perhaps unsurprisingly given the conclusion of this study, in that their membership compositions vary widely in attitude, aptitude and access to technology. A full exposition of experiences in remote forensic psychotherapy groups is beyond the scope of this paper, and the literature is limited in this area. However, further research is recommended to explore some of the foregoing findings: changes in attendance and involvement, abuses of technology, difficulties in integrating hybrid modes of contact, and new approaches adopted by group facilitators making use of technology.

The significance of physical, bodily presence could not be replicated remotely, which is an important issue for forensic treatment but also recognised throughout psychoanalytic literature (Hendry, Citation2020; Music & Waterfall, Citation2020; Padfield, Citation2021, Russell, Citation2018; Scharff, Citation2012; Wanlass, Citation2019). This supports the need to at least assess forensic patients once in person if there is a move to hybrid working, as predicted by other forensic professionals (Sturm et al., Citation2021). This recommendation is in line with general consensus among therapeutic professionals (Dunn & Wilson, Citation2020; The Open University, Citation2020; Simpson & Reid, Citation2014).

Although clinicians naturally evaluate therapeutic effectiveness in comparison with their usual in-person practice (Hoffmann et al., Citation2020; Norwood et al., Citation2018), and in this study found it to be degraded, remote psychotherapy may be the only option available for some patients. In common with the service evaluation findings (Rubitel & Miller, Citation2022), literature suggests that recipients of remote therapy had a more favourable impression of the work than clinicians (Norwood et al., Citation2018; Simpson & Reid, Citation2014; Wang et al., Citation2021). Findings from research with individuals for whom access to specialist treatment is particularly limited, indicate a higher perceived value of video contact (Kip et al., Citation2018), which may also be applicable to forensic populations lacking therapy provision.

If this is the case, offering forensic psychotherapy remotely by video may be a worthwhile endeavour. A key principle of pragmatic grounded theory is the testing of hypotheses through action (Morgan, Citation2020) and one such action the community may consider is to define and pilot a Virtual Frame for Forensic Psychotherapy.

Limitations

The context of the study featured a global pandemic, which provoked widespread anxiety and distress. Clearly, this will be incorporated within the data and it is impossible to discern how much of the experiences may be attributable to this context and to sudden transition, rather than exclusively to working in a different way.

The sampling design excluded clinicians working with children and adolescents because they did not engage with their patients remotely during the pandemic. Therefore, the study cannot be considered representative of even the full range of forensic psychotherapy offered by The Portman Clinic. Further research would be required to understand whether any results from this small study can be generalised more widely across the discipline, perhaps gathering data from the international community of forensic psychotherapists.

A richer theoretical understanding of the implications of offering a Virtual Frame model might be gained by examining, in the context of remote treatment, relevant forensic psychotherapy concepts implicated by the present study: Glasser’s (Citation1979) core complex, the importance of containment for forensic work (Pfafflin & Adshead, Citation2004), simulation of pseudo therapeutic progress (Blumenthal, Citation2022; Glasser, Citation1992), perverse corruption of reality (Ruszczynski, Citation2018), role of the superego in exhibitionism (Glasser, Citation1978), suicide risk in perverse transference interpretation (Yakeley, Citation2018); the role of aggression (Glasser, Citation1987), doubt in paedophile psychoanalysis (Campbell, Citation2014), internet escalation of sexual compulsive behaviour (Wood, Citation2011), and boundary elasticity (Ferenczi, Citation1928).

Conclusion

Forensic psychotherapy was offered to patients remotely via videoconference for the first time during the COVID-19 pandemic. This qualitative research studied the experience of forensic psychotherapists at The Portman Clinic to explore how forensic psychotherapy works remotely. The substantive grounded theory offered is that clinicians attempt to substitute for real, with varying degrees of success. They each do this in their own ways, which reflect their own attitudes, both to technology and to adapting to a new way of working. Modifications were attempted in establishing the frame; adapting technique; mediating contact; and evaluating possibilities. Some of the clinicians’ experiences were shared by general psychotherapeutic professionals offering remote therapy before and during the COVID-19 pandemic; others were specific to psychoanalytic process and reflected the significant debate about whether this can translate to online working. Yet more dynamics were peculiar to their patient population, and some of these considerations were echoed by practitioners in related forensic fields. There was recognition that working remotely could broaden the reach of specialist treatment to more service users who could benefit from it but that it is not equivalent to forensic psychotherapy in a clinic setting.

The implication of these findings may be that a new Virtual Frame for Forensic Psychotherapy is recommended, with appropriate training and supervision developed to support it and due consideration given to which patients, and clinicians, might work effectively this way. More research is required to support this undertaking; however, the present study offers some hypothetical factors that might be considered, including providing containment for clinicians and patients, defining new boundaries, ensuring appropriateness of equipment and setting, training in specific application of techniques, and requiring at least one assessment session in-person. If taken forward, there would seem to be potential for using technology to improve future access to forensic psychotherapy, especially within underserved secure populations.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the valuable support of Dr Yakeley and Dr Rost from The Portman Clinic in facilitating the research and providing feedback on this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agar, G. (2020). The clinic offers no advantage over the screen, for relationship is everything: Video psychotherapy and its dynamics. In H. Weinberg & A. Rolnick (Eds.), Theory and practice of online therapy: Internet-delivered interventions for individuals, groups, families, and organizations (pp. 66–78). Routledge.

- Ahlquist, L. R., & Yarns, B. C. (2022). Eliciting emotional expressions in psychodynamic psychotherapies using telehealth: A clinical review and single case study using emotional awareness and expression therapy. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 36(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02668734.2022.2037691

- Aiyegbusi, A., & Kelly, G. (Eds.). (2012). Professional and therapeutic boundaries in forensic mental health practice. Jessica Kingsley.

- Anthony, K. (2020). Moving your practice online. Online Therapy Institute. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://kateanthony.net/shortcoursementalhealth/

- Anthony, K., & Nagel, D. M. (2020). Ethical framework for the use of technology in mental health. Online Therapy Institute. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://www.onlinetherapyinstitute.com/ethical-training/

- Bartlett, A. (2011). Symposium commentary. European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling, 13(4), 395–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642537.2011.645621

- Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide. Sage.

- Blumenthal, S. (2022). Mother nature and father time: Oedipal imbalance and the premature structuring of reality in the perversions. British Journal of Psychotherapy, 38(2), 253–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjp.12717

- Brettle, A. (2010). Counselling in prisons: A summary of the literature. British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://bacp.co.uk/media/1967/bacp-counselling-in-prisons-literature-summary.pdf

- British Association of Counselling and Psychotherapy. (2021). Online and phone therapy (OPT) competence framework. British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://www.bacp.co.uk/media/10849/bacp-online-and-phone-therapy-competence-framework-feb21.pdf

- Campbell, D. (2014). Doubt in the psychoanalysis of a paedophile. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 95(3), 441–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-8315.12196

- Chong, S. C., Ang, J. K., & Tan, K. P. (2021). A “good enough” remote psychodynamic psychotherapy – a psychiatry trainee’s novice experience during coronavirus pandemic. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 65, 102835–102835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102835

- Daffern, M., Shea, D. E., & Ogloff, J. R. P. (2021). Remote forensic evaluations and treatment in the time of COVID-19: An international survey of psychologists and psychiatrists. Psychology, Public Policy, & Law, 27(3), 354–369. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000308

- Dominey, J., Coley, D., Devitt, K. E., & Lawrence, J. (2020). Remote supervision: Getting the balance right. Cambridge University Centre for Community, Gender and Social Justice. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://www.ccgsj.crim.cam.ac.uk/system/files/documents/remote-supervision_0.pdf

- Drogin, E. Y. (2020). Forensic mental telehealth assessment (FMTA) in the context of COVID-19. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 71, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2020.101595

- Dunn, K., & Wilson, J. 2020. Working online and in person. British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://video.silverstream.tv/view/aVUP3E2b

- Elliott, S. (2011). ‘Blind spots’: Shame, jealousy and envy as hidden aspects within forensic psychotherapy. European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling, 13(4), 357–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642537.2011.625199

- Ferenczi, S. (1928). ‘The elasticity of psychoanalytic technique’. In M. Balint (Ed.), Final contributions to the problems and methods of psychoanalysis (pp. 87–101). Karnac Books.

- Fisher, S., Guralnik, T., Fonagy, P., & Zilcha-Mano, S. (2020). Let’s face it: Video conferencing psychotherapy requires the extensive use of ostensive cues. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 34(3–4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2020.1777535

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine.

- Glasser, M. (1978). The role of the superego in exhibitionism. International Journal of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 7, 333–353.

- Glasser, M. (1979). ‘Some aspects of the role of aggression in the perversions’. In I. Rosen (Ed.), Sexual deviation (pp. 278–305). Oxford University Press.

- Glasser, M. (1987). Psychodynamic aspects of paedophilia. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 3(2), 121–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/02668738700700111

- Glasser, M. (1992). Problems in the psychoanalysis of certain narcissistic disorders. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 73(3), 493–504.

- Greenwood, D. (2010). Embracing the ‘allegiance effect’ as a positive quality in research into the psychological therapies – exploring the concept of ‘influence’. European Journal of Psychotherapy and Counselling, 12(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642531003637767

- Hendry, S. (2020, June 26). The virtual couch. 1843 magazine.

- Hoffmann, M., Wensing, M., Peters-Klimm, F., Szecsenyi, J., Hartmann, M., Friederich, H. C., & Haun, M. W. (2020). Perspectives of psychotherapists and psychiatrists on mental health care integration within primary care via video consultations: Qualitative preimplementation study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6), e17569. https://doi.org/10.2196/17569

- Holland, N. N. (1996). The internet regression. John Suler’s The Psychology of Cyberspace. Retrieved November 12, 2021, from https://www.truecenterpublishing.com/psycyber/holland.html

- Kip, H., Bouman, Y. H. A., Kelders, S. M., & van Gemert-Pijnen, L. J. E. W. C. (2018). eHealth in treatment of offenders in forensic mental health: A review of the current state. Systematic Review, 9, 42. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00042

- Kirschstein, M. A., Singh, J. P., Rossegger, A., Endrass, J., & Graf, M. (2021). International survey on the use of emerging technologies among forensic and correctional mental health professionals. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 50(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/00938548211042057

- Kortz, L. (2017). Understanding the working alliance and alliance ruptures in online psychotherapy from the therapist’s perspective. Albany.

- Lemma, A. (2017). The digital age on the couch: Psychoanalytic practice and new media. Routledge.

- Machado, D. D. B., Laskoski, P. B., Severo, C. T., Bassols, A. N. A. M., Sfoggia, A. N. A., Kowacs, C., Krieger, D. V., Torres, M. B., Gastaud, M. B., Wellausen, R. S., Teche, S. P., & Eizirik, C. L. (2016). A psychodynamic perspective on a systematic review of online psychotherapy for adults. British Journal of Psychotherapy, 32(1), 79–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjp.12204

- McGarry, A., & Reeves, A. (2020, December). Managing risk online. Therapy Today, 32–35.

- McPherson, S., Rost, F., Town, J., & Abbass, A. (2018). Epistemological flaws in NICE review methodology and its impact on recommendations for psychodynamic psychotherapies for complex and persistent depression. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 32(2), 102–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/02668734.2018.1458331

- Miermont-Schilton, D., & Richard, F. (2020). The current sociosanitary coronavirus crisis: Remote psychoanalysis by Skype or telephone. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 101(3), 572–579. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207578.2020.1773633

- Moller, N., & Vossler, A. (2021). What do we know about online therapy? [Keynote at British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy one-day online research conference] Research online – Keeping Clients at the Centre. May 16, 2020.

- Morgan, D. L. (2020). Pragmatism as a basis for grounded theory. The Qualitative Report, 25(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2020.3993

- Motz, A. (2008). The place of psychotherapy in forensic settings. Psychiatry, 7(5), 206–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mppsy.2008.03.003

- Murphy, L., Parnass, P., Mitchell, D. L., Hallett, R., Cayley, P., & Seagram, S. (2009). Client satisfaction and outcome comparisons of online and face-to-face counselling methods. British Journal of Social Work, 39(4), 627–640. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcp041

- Music, G., & Waterfall, A. (2020). Holding the frame and sense of connectedness during the pandemic. In Confer, (Ed.). Series 1: The Coronavirus series. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0F5NOZfcRxQ

- Nathaniel, A. (2008). Eliciting spill: A methodological note. Grounded Theory Review, 7(1), 61–66.

- Norwood, C., Moghaddam, Malins, S., Sabin-Farrell, R., & Moghaddam, N. G. (2018). Working alliance and outcome effectiveness in videoconferencing psychotherapy: A systematic review and noninferiority meta‐analysis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 25(6), 797–808. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2315

- Oncu, F., & Balcioglu, Y. H. (2021). Virtualization of mental health care in the midst of chaos: Is telepsychiatry a silver lining? The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences, 34, 219–222. https://doi.org/10.14744/DAJPNS.2021.00141

- The Open University. (2020). How to do counselling online: A coronavirus primer. In: British Association of Counselling and Psychotherapy and The Open University, (Eds.). Open learn create. Retrieved May 24, 2022, from https://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/course/view.php?id=5039

- Padfield, L. R. (2021). On disembodiment, dissonance and deprivation – why remote psychotherapy in the time of COVID-19 is so taxing. Psychoanalysis, Self and Context, 16(3), 218–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/24720038.2021.1933986

- Pfafflin, F., & Adshead, G. (2004). A matter of security: The application of attachment theory to forensic Psychiatry and psychotherapy. Jessica Kingsley.

- Rey, H. (1994). Universals of psychoanalysis in the treatment of psychotic and borderline states. Free Association Books.

- Rubitel, A., & Miller, L. (2022). An audit into the portman clinic’s adult patients and the portman clinic’s clinicians experiences of in-person versus remote therapy and research sessions [ Unpublished work].

- Russell, G. I. (2018). Screen relations: The limits of computer-mediated psychoanalysis and psychotherapy. Routledge.

- Ruszczynski, S. (2018). ‘The problem of certain psychic realities: Aggression and violence as perverse solutions’. In D. Morgan & S. Ruszczynski (Eds.), Lectures on violence, perversion and delinquency (pp. 23–42). Routledge.

- Scharff, J. S. (2012). Clinical issues in analyses over the telephone and the internet. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 93(1), 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-8315.2011.00548.x

- Scharff, J. S. (2018). Psychoanalysis online: Mental health, teletherapy, and training. Routledge.

- Simpson, S. G. & Reid, C. L. (2014). Therapeutic alliance in videoconferencing psychotherapy: A review. The Australian Journal of Rural Health, 22(6), 280–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12149

- Smith, J., & Gillon, E. (2021). Therapists’ experiences of providing online counselling: A qualitative study. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 21(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12408

- Smith, K., Moller, N., Cooper, M., Gabriel, L., Roddy, J., & Sheehy, R. (2021). Video counselling and psychotherapy: A critical commentary on the evidence base. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 22(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12436

- Sturm, A., Robbers, S., Henskens, R., & de Vogel, V. (2021). ‘Yes, I can hear you now … ’ online working with probationers in the Netherlands: New opportunities for the working alliance. Probation Journal, 68(4), 411–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/02645505211050869

- Symington, N. (2011). Analysis and supervision by telephone and Skype: Letter. The Bulletin of the British Psychoanalytical Society, 47(9), 46.

- Tao, L. (2017). The effect of the analytic couple’s shared physical presence on transference fantasy. In J. S. Scharff (Ed.), Psychoanalysis online 3: The teleanalytic setting (pp. 97–104). Routledge.

- Tao, L. (2018). Teleanalysis: Problems, limitations, and opportunities. In J. S. Scharff (Ed.), Psychoanalysis online 2: Impact of technology on development, training, and therapy (pp. 105–122). Routledge.

- Towl, G. (2011). Forensic psychotherapy and counselling in prisons. European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling, 13(4), 403–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642537.2011.645620

- Treanor, A. (2017). The extent to which relational depth can be reached in online therapy and the factors that facilitate and inhibit that experience: A mixed methods study [ Student thesis: PsychD]. University of Roehampton. 19 Dec 2017.

- Velykodna, M., & Tsyhanenko, H. (2021). Psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic psychotherapy in Ukraine during the COVID-19 pandemic unfolding: The results of practitioners survey. Psychological Journal, 7(1), 20–33. https://doi.org/10.31108/1.2021.7.2

- Vincent, C., Barnett, M., Killpack, L., Sehgal, A., & Swinden, P. (2019). Technology and private practice. In J. S. Scharff (Ed.), Psychoanalysis online 4: Teleanalytic practice, teaching, and clinical research (pp. 109–122). Routledge.

- Vossler, A., Moller, N., Full, W., Phybis, J., & Roddy, J. (2021, November 10). Here to stay … !? The future of online therapy [free online research event series 2021 – 2022]. Society for Psychotherapy Research.

- Wang, X., Gordon, R. M., & Snyder, E. W. (2021). Comparing Chinese and US practitioners’ attitudes towards teletherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asia Pacific Psychiatry, 13(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/appy.12440

- Wanlass, J. (2019). Assessing the scope and practice of teleanalysis: Preliminary research findings. In J. S. Scharff (Ed.), Psychoanalysis online 4 (pp. 1–18). Routledge.

- Wood, H. (2011). The internet and its role in the escalation of sexually compulsive behaviour. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 25(2), 127–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/02668734.2011.576492

- Yakeley, J. (2018). Psychoanalytic perspectives on paraphilias and perversions. European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling, 20(2), 164–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642537.2018.1459768

- Zoumpouli, A. (2021). Is a ‘good enough’ experience possible for patients and clinicians through remote consultations? A guide to surviving remote therapy, based on psychoanalytic and neuroscientific literature. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 34(4), 278–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/02668734.2021.1875025