ABSTRACT

This research reveals children’s stories of sustainability learning utilising a scalar framework to understand the influence of information flows. Eleven Scottish primary school pupils captured images illustrating their sustainability understanding which informed subsequent interviews. This research contributes to theory by examining the Eco-school curriculum within a scalar framework and providing empirical narratives that illustrate how children understand and assume responsibility for sustainability, as learned within vertical and horizontal scaling. In adopting a novel approach of listening to children, the findings extend scalar frameworks from organisational settings to examine sustainability discourse through their perceptions of who are sustainability heroes and villains. Within this, nuances of emergent activism and the application of local initiatives to ‘save the planet’ provide implications for markets, marketing management and policy development.

Introduction

This exploratory paper examines the voice of children as they narrate stories constructed from their learning and understanding of sustainability, informed by Eco-school curricula, as a means of scaling sustainability information within macro and micro sites that encourage sustainable practice. From a theoretical perspective, scaling provides an illustration of how sustainability is infusing into wider society, from governance, business and consumer perspectives, to better understand how education and marketing cumulate into driving sustainable practice. Children’s voices are under examined in the academic sustainability literature (Davies et al., Citation2020; Hosany et al., Citation2022; Schill et al., Citation2022), and little is known about how they absorb and interpret sustainability learning or how this translates into beliefs and practices. While research has considered sustainability from the perspectives of numerous generational cohorts, especially millennials and Generation Z, there has been little examination of Generation Z under the age of 18 years. This seems somewhat remiss, given that Generation Z consumers over the age of 18 years are increasingly engaged and vocal in expressing their concern for sustainability (Dabija et al., Citation2019); previous generations are merely custodians of the planet, whereby arguably the acceleration of utilising planetary resources for economic development has significantly compromised the future of humanity (Nuccitelli, Citation2017). With only nine years left to halt the irreversible damage caused by accelerated production, consumption, and the generation of waste (United Nations, Citation2019), there are reports on how young people’s concern for sustainability impacts on their mental health (Richardson, Citation2019). Greta Thunberg, a prominent Generation Z self-appointed spokesperson, has voiced her dismay at the lack of consideration for sustainability, from governments and businesses, and has campaigned globally over the last four years for immediate action to tackle climate change (Hosany et al., Citation2022). Thunberg is now 18 years old, but began her campaign aged 14 years, by encouraging pupils to take strike action by being absent from school and to protest for action on climate change: the #FridaysForFuture movement (Hosany et al., Citation2022; Newsround, Citation2019). In a speech made at the 2018 United Nations Climate Change Conference, held in Poland, Thunberg said:

Since our leaders are behaving like children, we will have to take the responsibility they should have taken long ago. Greta Thunberg, COP24, Poland, 4 December 2018 (Newsround, Citation2019)

The idea that global leaders are not taking responsibility for ensuring future prosperity was evident in the last Global Shapers Annual Survey from 2017, which found that for the third consecutive year climate change was the main concern for young consumers (aged 18–35 years) (World Economic Forum, 2017), and that 91% of those surveyed believed that science has proven that humans are responsible for climate change. Currently, children will inherit a commodity-oriented world with behaviours that are detrimental for the future health of the planet. Thunberg noted that ‘fairy tales of economic growth’ were prioritised over planetary protection and at a UN Climate Summit in New York in 2019 she said:

The eyes of all future generations are upon you. And if you choose to fail us, I say – we will never forgive you. Greta Thunberg, UN Climate Summit, New York, 23 September 2019 (Newsround, Citation2019)

This quote underpins responsibility towards ensuring a healthy ecosystem for future generations; therefore, this paper is concerned with the eyes, and especially the voices, of school children, a cohort that has so far been underrepresented in sustainability research (Davies et al., Citation2020). Yet, the influence of children on household consumption and related behaviours is significant (Chitakunye, Citation2012; de Faultrier et al., Citation2014; Kerrane & Hogg, Citation2012; Singh et al., Citation2020). Research has found that children influence their family to adopt sustainable behaviours, such as recycling and the purchase of Fairtrade products (Ritch & Brownlie, Citation2016a, Citation2016b). Ritch & Brownlie (Citation2016a, Citation2016b) found that children in the household had learned about sustainability in the curriculum through ‘Eco-Schools’, a global initiative developed by the United Nations to empower children to engage in their environment and community, to bring about change that will address climate change (Eco-schools, Citation2014). Schools wishing to attain eco-status, educate pupils in sustainability issues and terminology to empower their responsibility for sustainability. This situates schools as scalar-social sites for exchanging information that can infuse within wider society: Eco-schools enable the space to produce behaviours that provide practical purchase for sustainability. Extant literature has identified that the main routes to socialise children about sustainability are parents/household (Davies et al., Citation2020; de Faultrier et al., Citation2014; Singh et al., Citation2020) and school (Jorgenson et al., Citation2019); yet this often adopts a dual lens of analysing transference of the message rather than examining the agency of children and how they lead change for themselves, their peers and their household (Davies et al., Citation2020). While Ritch and Brownlie (Citation2016b) reported that children influenced sustainability within household decision-making, what was missing was the voice of children. This research seeks to address this disparity by asking children how they construct sustainability and how this informs their perceptions of their wider contribution to society through everyday behaviours. Consequently, this research does not include parental contributions to household sustainability practice or reports on how sustainability information and activities are disseminated by the school. It solely considers how the children construct understandings of, and their responsibility to, sustainability, by listening to how they interpret information communicated within horizontal and vertical flows. Moreover, other modes of influencing sustainability to young children are not reported in the literature, yet messages communicated more widely in society may be absorbed; this exploratory research aims to obtain a better understanding of which messages are effective in influencing responsibility for sustainability. Understanding this will help to illuminate upon what younger consumers expect from marketing management in terms of how sustainability is being addressed.

This research makes contributions to theoretical development firstly by examining Eco-school curricula through a scaling lens. Concepts of scaling sustainability have been somewhat neglected, despite climate change being everyone’s responsibility: from international governance to businesses and consumers (Spicer, Citation2006). While scaling sustainability has been examined in organisational settings (Ivory & MacKay, Citation2020; Springer, Citation2014; Swaffield & Bell, Citation2012), the impact of scaling sustainability through the curriculum, to educate future generations in their formative years, has not been examined. In this research, scaling does not refer to growth or expansion (Ivory & MacKay, Citation2020), it refers to a process of extending influence to encourage behavioural responses that lead to impact (Duggan et al., Citation2014), as exemplified by Eco-schools as social sites for information flows. This is consolidated into examining the influence of stimuli that encourages behavioural response and impacts behavioural change. Secondly, there is a paucity of research on Eco-school implementation (Davies et al., Citation2020), especially from a pupil perspective, and how this resonates with the school setting to inform household behaviours. As this paper examines scaling sustainability through listening to children’s stories of Eco-school curriculum, it will be of interest to marketing managers and policy makers to gain a deeper understanding of how young consumers may demand change that is responsive to the sustainability agenda. The paper begins by establishing the importance of addressing sustainability, developing the argument for scaling sustainability, and examining the scaling of information flows and the permeation into wider discourse. This is followed by consideration of the role of Eco-school implementation, and how sustainability is framed within the curriculum and related activities to engage with pupils. Methodology is then outlined, before discussing the themes identified through the analysis and concluding with recommendations for progressing the sustainability agenda.

A critical time for sustainability

The concept of sustainability emerged as a response to climate change (United Nations, Citation2019), exacerbated by systemic scaling of industrialisation, and globalised markets that are reliant on scarce resources for production and the international transportation of commodities. Recent debates at COP26 in November 2021 have illustrated the complexity of addressing responsibility (United Nations, Citation2021), especially when emissions are higher in production countries who are less financially equipped to combat the detrimental impact (United Nations, Citation2020) and more reliant on production for economic development. This is a critical stage for the future of the planet (Ivory & MacKay, Citation2020), and limited time remains to address the climate crisis (United Nations, Citation2019). This situates responsibility for sustainability at international, national, local, and consumer levels, leading to the concept of scaling information to widen impact (Adger et al., Citation2005; Spicer, Citation2006). Therefore, educating the next generation of consumers of their responsibility to manage sustainability is an important tool in addressing climate change (Jorgenson et al., Citation2019). It is clear that those future generations, currently too young to vote to bring about change, are increasingly vocal in their concern for sustainability (United Nations, Citationn.d.). Scaling, therefore, provides a framework to examine how sustainability constructs are infiltrating through society.

Scaling sustainability

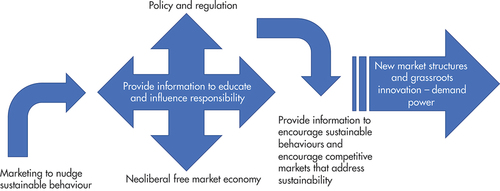

Scaling involves expanding concepts within and beyond the original context, including local and global settings (Duggan et al., Citation2014). Academic literature examining scaling reveals the nuances of theoretical and practical scalar applications that fall within economic and governance debates (Marston et al., Citation2005). Vertical scales are best placed to address the climate crisis, including implementing policy, business regulation and informing citizens/consumers; transcending from global to local initiatives. However, vertical scaling conflicts with neoliberalism, which proliferates individuals’ free choice within the market (Springer, Citation2014; Swaffield & Bell, Citation2012). If policy and regulation were implemented to reflect the true cost of production for the environment and workers, prices would become less competitive, and consumer options would be restricted. Additionally, autocratic governance can minimise opportunities for innovation and ownership at a grassroots level (Springer, Citation2014), and it is grassroots movements where alternative sustainable systems that challenge behavioural norms often emerge from (Casey et al., Citation2020; Davies et al., Citation2020). Yet, Adger et al. (Citation2005) argue that individual (consumer) behaviour is currently constrained within market structures, particularly when competitive global markets are driven by decreasing prices, reflected within consumers pricing thresholds (Ritch, Citation2020). What is required is a multiple scalar approach, as presented in , that provides choice that reflects the diversity of economic flows and the social conventions of countries and individuals (Jonas, Citation2007).

Figure 1. Multi-scalar approach to extend influence that empowers sustainable people and encourage demand power in the market.

In this sense, horizontal scales are affected vertically, and governments have a responsibility to structure and provide ‘nudges’ to consumers that encourage sustainability within a local setting, as well as working towards a global consensus. This enables consumers to manage consumption to reflect their sustainability preferences and finances. provides an example of a multiple scalar approach to sustainability using plastic shopping bags, as provided by retailers at the point of consumption. The plastic bag became a symbol of a ‘throwaway society’, amid concerns for the growth of single-use plastic routinely disposed of at landfill, as well as littering localities (Ritch et al., Citation2009). Prior to regulations imposing a charge (initially 5 pence and now 10 pence), businesses and environmental groups campaigned to encourage more responsible consumer behaviour, such as the reuse of bags. Marketing has informed consumers about ways in which the retailer has supported responsible behaviours, including instore signage, consumer incentives (such as green points), cloth and durable plastic bags for life, and facilities to recycle plastic bags (Ritch et al., Citation2009). This provided a nudge to consumers to consider the impact of their behaviours, support behavioural change and reinforce societal norms. Positive responses from consumers and businesses encouraged regulation, firstly in Ireland in 2002, and followed by the UK Governments of Wales (2011), Northern Ireland (2013) Scotland (2014) and England (2015) (Centre for Public Impact, Citation2016).

Figure 2. Plastic shopping bags: an example of a multi-scalar approach from policy, marketing, and consumer-behaviour.

This exemplifies how adopting a multiple scalar approach can engage and empower all stakeholders to advance the sustainability agenda. The paper continues with this theme using the example of Eco-school activities as a multi-scalar site that seeks to inform and motivate children, consumers of the future, to consider influences that encourage sustainable practice. This is an important site for understanding responsibility for sustainability, especially within neoliberal markets where consumers may feel overwhelmed by individual responsibility and appropriate ‘blame’ elsewhere (Ritch & Brownlie, Citation2016a), disabling practical purchase. Luchs et al. (Citation2015) consider understanding the concept of consumer responsibility as being under-researched in the marketing literature, despite this being a better predictor of practicing sustainable behaviours. They also caution that responsibility is ideographically constructed through a process or responsibilisation, which has the potential for ‘demand power’ within the marketplace. The aspect of scaling addressed is empowerment that enables consumers the space to produce sites and behaviours that underpin practical purchase for sustainability. First, this will be examined in organisational settings.

Scaling sustainability in organisational settings

Increasingly, organisations address sustainability as competitive positioning to address consumer concern for the detrimental impact of business practice on the environment (Luchs et al., Citation2015). Internally, organisations appoint sustainability champions to identify specific objectives who then assume responsibility for encouraging and implementing sustainable business practice; this represents horizontal scaling. Swaffield and Bell (Citation2012) interviewed a number of sustainability champions within several UK organisational contexts (including energy, finance, retail, and construction) and found that sustainability champions assume that their colleagues operate within a neoliberal mindset of economic self-interest and therefore seek to ‘nudge’ behavioural change through education. This means that the issue of climate change is not tackled at an institutional level or included as a strategic business goal; although this is systematic of neoliberalism that does not disrupt market structures, it does not progress the sustainable agenda in the same way as vertical scaling (regulation). Nevertheless, Swaffield and Bell (Citation2012) found that sustainable practice was transferred to the home setting, evidence of the success of horizontal-scaling, nudging responsibility for sustainability.

Swaffield and Bell (Citation2012) call on future research to consider the ability of sustainability champions in other horizontal-scalar settings, to challenge the dominance of neoliberalism and promote sustainability in a wider context. This would involve empowering individuals/consumers with information that encourages responsibilisation for sustainable change, as portrayed in the Eco-school movement. This means that scaling is important within as consumers have free choice. Sustainable information and education can be provided through effective marketing to engage consumer responsibilisation (Davies et al., Citation2020). Engaging with younger consumers may help shape the future development of consumer culture and market structures to include sustainability. Despite the dominance of neoliberalism within government and business contexts, concern for climate change has provided opportunities for resistance and grassroots movements, illustrating the potential for sustainable business structures and scalar flows into the household (Springer, Citation2014; Swaffield & Bell, Citation2012). Consequently, Eco-Schools can influence young consumers to become sustainable people (Davies et al., Citation2020).

Eco-school as a site for scaling sustainability

Scaling sustainability has the potential to empower sustainable practice and activate ‘demand power’ within markets, an approach adopted by UNICEF to plant the seeds of sustainability into children’s awareness to fertilise growth for sustainability practice (UNICEF, Citation2019). Ivory and MacKay (Citation2020) conceptualise scaling as assimilation, mobilisation, and transition. Assimilation refers to conformity, where agency focuses on what can be achieved by an individual and integrated into practice, to become a normalised behaviour from which scaling can be progressed. Mobilisation is where leverage for scaling is escalated through awareness of the issues, which are then scaled beyond original concepts; in this sense, applying broad concepts of sustainability in one context to stimulate cognitive transferral to other contexts. Transition occurs through embedded sustainability practice, accelerating to shape wider societal behaviours to expand practical purchase and responsibilisation (Ivory & MacKay, Citation2020; UNICEF, Citation2019).

The aim of the Eco-school movement is to educate children of their responsibility to care for the environment and to transition sustainable practice into local communities (Eco-schools, Citation2014). Eco-schools are a global initiative that seek to empower children to engage in their environment and bring about change that will address climate change (Eco-schools, Citation2014), and are therefore social sites for assimilation, mobilisation and transition. Although previous research has examined the implementation of Eco-schools as engaging with children in the school setting (Ozsoy & Ertepinar, Citation2012; Powell et al., Citation2008), there has been little attention on how Eco-schools develop sustainable people (Davies et al., Citation2020) or how knowledge informs behaviours that scale into the home to influence household practice. Eco-schools provide an example of how Springer (Citation2014) suggests scaling can be used to assimilate a dynamic sustainability strategy within vertical and horizontal scales; in particular, Eco-schools provide leverage for mobilising social structures and power relationships to identify hierarchical structures. As such, Eco-schools provide a scalar site for information flows and establishing new social behavioural norms, moving through the curriculum to influence peers and family.

Eco-school implementation

The concept of Eco-schools emerged from the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (Earth Summit), held in 1992, in Rio de Janeiro and were established in the UK in 1995 (Pirrie et al., Citation2006). There are currently 49,000 Eco-schools in 64 countries (both developed and developing), illustrating that Eco-schools are considered as an important social site to tackle concerns around climate change. Eco-schools are awarded a green flag which is to be displayed in the playground, that signals and celebrates the commitment to climate change. Achieving Eco-school status requires an environmental review, aligning curriculum objectives with local issues that will assimilate sustainability into each pupil’s everyday experiences to mobilise transition. Examples include questioning how the school impacts on sustainability, such as the 3Rs (reduce, reuse and recycle), and appropriating information which would mobilise into activities that address litter, energy use, food, waste-management, and recycling (Ozsoy & Ertepinar, Citation2012; Pirrie et al., Citation2006). Responsibility for scaling sustainability transitions are encouraged through the production of an eco-code, decided by the school’s eco-committee which consists of teachers and pupils, to identify ways in which the school activities impact on climate change and to decide which to focus their attention on for positive change. In Scotland, Pirrie et al. (Citation2006) found that conversations around Eco-schools enabled teachers to work on health, transport and enterprise issues, assimilating links between the ‘health and well-being’ of the pupils and ‘that of the planet’ (ibid, p1). In research commissioned by Scotland’s Commission for Children and Young People, Eco-school involvement was found to be an important link between pupil achievement and attainment in areas of deprivation (Mannion et al., Citation2015). Participation not only provided opportunities for decision-making but also fostered positive relations between pupils and teachers that enabled mutual respect (Mannion et al., Citation2015).

Research by Ozsoy and Ertepinar (Citation2012) on elementary schools (the age group is not established) in Turkey found that the active involvement of pupils, from the environmental review through to monitoring of the impact of the action plan, assimilated and mobilised the pupils’ attitude to caring for the environment. This demonstrates that scaling from global to local levels minimises the scale of the issues, enabling feasible action that can transition into practice. Ozsoy and Ertepinar (Citation2012) attribute this scaling exercise as pertaining to a higher awareness of the issues and active involvement in Eco-school activities, such as planting trees in the school grounds or establishing a school garden. Developing an action plan through an eco-code helps to structure activities more effectively, particularly through informing and involving others in the home and community, acting as transformative leaders to transition positive change (Tourish et al., Citation2010). Often, this would include partnerships with local community-based initiatives that respond to sustainability, providing a means by which pupils can learn about the environment and actively progress positive outcomes. As the pupils identify the main issues of concern within their local area, this encourages ownership of the solutions (Swaffield & Bell, Citation2012). The curriculum objectives would be aligned with the environmental review and used to develop knowledge and implement sustainable behaviours. Additionally, the review includes global citizenship to educate children on production in developing countries, linking with the Fairtrade movement to encourage responsible consumption.

An example of active assimilation and mobilisation was outlined by Cairns (Citation2017), who examined the discourse around school gardens, initially from the perspective of media reports. She outlines the growth in school gardens as emerging out of concern for contemporary health and the environment, arguing that school gardens are a useful tool for connecting children, through hands-on experiences, to their food. Cairns (Citation2017) notes that school gardens have received much praise; even the critics who profess the neoliberal ethos of choice in the marketplace have not contradicted the approach. This is important to address, given that neoliberal politics criticise the implementation of sustainability legislation that would prohibit choice within a free market (Foley, Citation2021). Cairns (Citation2017) illustrates the positive links between education, authentic experiences, and sustainability: children are not only learning new skills and benefiting from time outdoors, but also learning about where food comes from and how to be self-sufficient. Research on outdoor learning and attainment is gaining traction, resulting in new nurseries and schools being situated outside (Ewert et al., Citation2005). This is especially important for urban children who may have little opportunity and access to rural landscapes (Cairns, Citation2017). Cairns (Citation2017) concludes that the benefits of engaging children with food, not only provides a ‘site for creating social change’ (p. 3), but as a means of accessing healthy food and promoting scalar notions of individual responsibility; this transcends the structural issue of who produces food to inserting ‘consumer driven change’, that can progress a ‘more sustainable society’ (ibid). Underpinning the school garden is the promotion of ‘ecological sustainability through an appreciation for nature’ (Cairns, Citation2017), which aligns with the Eco-school agenda and promotes concern for climate change within the curriculum. Examining the pupils’ perspective offers new insight that will determine whether the Eco-school curriculum advances a more sustainable society.

Childhood is a time where behaviours and beliefs are socially constructed (Cairns, Citation2017), and embedding the importance of climate change focuses this agenda more acutely, especially as children are socialised through engaging their imaginations. Carrying out an environmental review does not only situate responsive sustainability to local capabilities but stimulates ownership; as the pupils determine which sustainability activities are important to them, they become champions of the sustainability agenda by collectively responding to climate change (Swaffield & Bell, Citation2012). However, if an advantage of Eco-schools is to provide opportunities to encourage children to become socially responsible consumers, this could influence businesses to address sustainability within production and marketing practice. Eco-school activities may shape the expectations and behaviours of young people, who will emerge as consumers with new sustainable expectations. Consequently, Generation Z may be less forgiving over the nuances of politics and commerce while ‘our house is on fire’ (Thunberg, Citation2019). More importantly, it embeds climate change as an issue that requires new market structures, and, as such, young consumers’ moral outlook will shape business and organisational practice (Antonetti & Maklan, Citation2016) to adopt more sustainable ways of production and retailing to obtain competitive advantage, as well as potentially influencing policymakers to progress the sustainability agenda through regulation at an international level.

Although previous research has examined the implementation of Eco-schools as engaging with children in the school setting (Ozsoy & Ertepinar, Citation2012; Powell et al., Citation2008), this has been limited and there has been little attention paid to how children absorb, interpret, and assume responsibility for sustainability. Ritch and Brownlie (Citation2016b) found that sustainability is often included by children as a persuasive means for consumption, and aspects of sustainability like ‘recycling’, ‘Fairtrade’ and ‘organic’ are becoming commonplace in household ideology. They also report on children bringing home information from school that aligns with sustainable activities in the home, although it is not clear whether children influence household behaviours or whether household behaviours that reflect parental preferences for sustainability are then endorsed by the curriculum; arguably, what is important is situating responsibilisation for sustainability into young mindsets to shape and encourage sustainable practice. As previous research has focused on the voice of the parents as the main gatekeepers to consumption and household behaviours (Davies et al., Citation2020), this research turns attention to the children in the household to examine the link between what is taught through school and what is practiced at home (Chitakunye, Citation2012). Educating the next generation of consumers about the implications of production, consumption and household behaviours, and their responsibility as citizens to manage sustainable implications, is an important tool in addressing climate change. As such, this paper contributes to understanding the scaling of sustainability information flows through the Eco-school curriculum.

Methodology

This research is underpinned by the ethos that children will have been educated from a young age in caring for the planet through the Eco-school movement, adopting an interpretative approach in acknowledging that involvement in sustainability is socially constructed (Cairns, Citation2017; Chitakunye, Citation2012; Schill et al., Citation2022). To listen more closely to the children’s voices, it was considered relevant to assign autonomy over to them (Chitakunye, Citation2012; O’Connell, Citation2013); therefore, to focus their attention on the task, the children were given a disposable camera, with the potential to take 27 photographs, and asked to capture activities that related to what they had learned through the Eco-School curriculum. Their guidance was:

I would like you to take photographs of the activities you see out of school that remind you of what you have learned through Eco-School learning. There is no right or wrong answer, and this is not a test. I am interested in your thoughts about what you have learned through Eco-School in the classroom and how you see this outside of school. Once you have taken the photographs, I would like you to tell me why you captured that scene and how it relates to Eco-School learning.

O’Connell (Citation2013) adopted a similar approach of photo-elicitation when exploring family food practice with children. This led to more insightful data because children use imagery to build stories. Adopting a similar approach, this paper sought children mature enough to articulate their behaviours, therefore convenience and snowball sampling led to the recruitment of ten pupils, aged between 10 and 12 years, from two Scottish primary schools. The children are represented within this paper by pseudonyms. An additional ten children had agreed to take part and were provided with cameras after an initial meeting, however requests to collect the camera and conduct the interviews failed due to the children losing interest in the project; this was assumed to be a consequence of assigning autonomy to the pupils, but also illustrates that participation was voluntary. Ethical consent was obtained along with parental approval, and some parents were present during the interviews, often contributing with stories around household activities. A few parents had been involved with providing the children with guidance on what to photograph, slightly skewing the results by making it less clear who instigated sustainable practice. In the case of Liam, his younger sister Ava (aged eight) had been involved with taking the photographs and she also contributed to the interview (totalling eleven participants); as an Eco-school champion, Ava was vocal about implementing sustainability in the home. Other children were evidently playing independently outside the home when taking photographs, and their stories illustrate higher autonomy. Some children felt overwhelmed at the task, particularly the interview, perhaps scared this was testing their sustainability knowledge!

Parents were asked to complete a short questionnaire on household demographic information, including the involvement of the children in the Eco-School committee – Mark, Lara, Violet, and Ava were Eco-school committee members who represented their class. Initial meetings were carried out with the parent and child to discuss the guidance given on what to photograph, and to arrange subsequent interviews to discuss the images captured. These meetings did not include data capture but included teaching the children how to work the manual aspect of moving the disposable camera on in order to take the next photograph; there was confusion at the inability to see the photograph taken! While most of the children had access to their own mobile phone, this was not assumed, and while the disposable camera is viewed as single-use plastic that is an antithesis to sustainability, it was considered necessary to ensure inclusivity of participating in the research. Once the photographing task was completed, the cameras were collected, and the images developed; it is important to note that not all photographs reflected sustainability, and that some were ‘accidents’! Following on from this, the children participated in audio-recorded interviews, with conversational questions structured around their images; they were asked to describe the content of each of the photographs and their thoughts around this in relation to sustainability. The interviews lasted between 30 and 60 minutes, and data comprised of 107 A4 pages once transcribed verbatim. Thematic analysis from the interviews and images were identified and are presented next.

Topic and theme development

Similar to the coding adopted by Schill et al. (Citation2022), analysis was both inductive and deductive. Initial coding began by deductively examining the photographs related to Eco-School activities, including the 3Rs, and protecting nature, as captured in . Topics were literally derived, and illustrates the number of times that topics were captured in the photographs. Because the discussion was led by the photographs, the topics directed the interviews. What is interesting to note from the table is that certain aspects were captured more frequently by each child; for example, David was very focused on waste, recycling, and reuse, whereas Robbie was very focused on reuse and growing flowers and vegetables. This may be a consequence of applying a narrow lens to the task and not thinking more widely, or possibly associated to their age-related cognitive ability (Hosany et al., Citation2022). Additionally, the purpose of the research was not testing sustainability knowledge, but to better understand how they conceptualised wider constructs of sustainability information flows and how this was reflected in their everyday lives. The photographs provided evidence of Eco-School education underpinning the children’s understanding of what were considered as sustainable and unsustainable behaviours. The interview discourse illustrated ways in which the children incorporated Eco-School knowledge outside of school, illustrating their connectivity with responsibilisation that advances understanding of perceptions of socially acceptable behavioural norms for a more sustainable future as an illustration of vertical scaling influencing practical sustainable purchase.

Table 1. The contents of the photographs which led to the development of topics.

Table 2. Participation in sustainable activities represented in the photographs.

Having established assimilated knowledge, the next stage was to inductively decipher the children’s conversations around the topics and their rationale for capturing the image, which included: determining their understanding of why it was important to adopt sustainable behaviours and their perceptions of responsibility towards sustainable practice. The inductive coding stage was then aligned deductively with theoretical constructs from Ivory and MacKay’s (Citation2020) scalar framework of assimilation, mobilisation, and transitioning. However, under the construct of ‘transitioning’, the data revealed two manifestations:

Firstly, critical activists emerged from frustration that despite assimilating knowledge (not only through Eco-School learning but also wider media and social influences), and amid much encouragement to mobilise sustainable practice and become sustainable people (from Eco-School, family, friends, and social influences, such as the Newsround programme), scaling sustainability was not prioritised by local council, businesses, and adults in their locality. Therefore, some were critical of those who they felt should be more responsible towards sustainability. While this affront to their moral code of objective right and wrong behaviours may be a consequence of their age-related cognitive development (Hosany et al., Citation2022), it does advance understanding of how the critical lens through which Thunberg challenges global governance is reflected in this generation.

Secondly, scaling sustainability globally represented micro-activism mirroring macro- activism (Thunberg), and managing localities to make a global impact.

The emergent scalar framework (described next) for analysis includes a baseline of assimilating knowledge that emerges from the topics captured in the photographs, followed by three themes, one that represents mobilisation and the other two that represent transitioning.

Eco-School scalar framework

Assimilating knowledge of eco-curriculum: Eco-school becomes a site for assimilation and practical purchase (baseline).

Mobilising sustainability to situate collective responsibilisation

Transitioning as critical activists: questioning why others were being irresponsible by not adopting sustainable practice.

Scaling sustainability globally: transitioning into sustainable people through extending influence and increasing impact

Findings and discussion

As stated previously, certain concepts had resonated with each child, and external imagery had ignited their imaginations to shape their perception of what was important for sustainability. For example, Robbie (aged 12 years) had taken a photograph of a poster he had drawn in Primary 1 (aged 5 years) (). He was told that it was better to plant flowers than cut flowers, because flowers attract bees and there was a dwindling bee population which would impact on the wider environment. Robbie had kept that picture: he was now in Primary 7 and remembered this story; the activity of drawing from his imagination led to the story resonating with him.

Further photographs taken by Robbie demonstrate that this impacted on his current activities: he had photographed soil, flower, and vegetable seeds which he intended to sow to support bee populations and to have home grown produce. This is an illustration of how Eco-school learning can impact on actions and behaviours, even years later, through assimilation of the key message, mobilising the message into action and transitioning it into an embedded behaviour. Also interesting was that the main discussions in the interviews centred on concerns for the welfare of sea life and wildlife, even though there were no images of these subjects captured in the photographs; yet images in the wider media depicting the dangers of litter in our seas and oceans and to wildlife had infused the pupil’s imaginations, illustrating that the children were thinking through the consequences of human behaviour and how this impacts more widely on sustainability. This thinking through was drawn from probing the content of the photographs and the child’s thoughts of the implications, based on their understanding of sustainability. The ‘assimilation of knowledge’ theme lays the foundation for the understanding of key sustainability concepts and constructs, illustrating the premise from which mobilisation and transition emerges. Therefore, assimilating knowledge is addressed first.

Assimilating knowledge

In was expected that Eco-school learning would lead to knowledge of the 3Rs, litter, waste-management, energy, and transport, as was reported by the literature (Ozsoy & Ertepinar, Citation2012; Pirrie et al., Citation2006). What was unexpected was how much this had assimilated embedded normalised behaviours. Eco-schools are evidently successful in priming pupils for issues in the locality as being everyone’s responsibility, much like the sustainability champions reported by Swaffield and Bell (Citation2012). Litter in the locality was a primary concern for the pupils, and most of the photographs included examples of litter in parks and the street. Two conversations emerged from this: a reduced pleasure from playing in what was perceived as a dirty environment and concern for the impact this may have on wildlife, as illustrated in the following quotes:

In our playground there’s crushed up cigarettes on the floor. That’s where people play. In the playground, there’s more litter [on the ground] than there is in the bins, because people just put it somewhere thinking no one will see it. Milly

If you are playing football and there’s a bit of litter right in front of you, and you are about to shoot [a goal, litter gets in the way]. Dimos

Cigarette butts and ash just scattered around and I think that people should be more caring about their environment. If you are smoking, you should still care about the people around you and what damage it could do. Luke

We need to be more careful of the amount of plastics we use, what we drop on the floor, and make sure we’re using the bins. Harry

My mum says mice go to dirty places, like where lots of litter is. Dimos

Ingrained concern that litter should be disposed of responsibly was a key theme within the data. Milly reports confusion that litterers cannot see the very existence of their action, in what is a shared space. Smoking in particular, especially around where children play, was considered an action illustrating lack of care for others and the environment. Luke echo’s Thunberg’s assertion of a lack of adult responsibility when he states: smokers ‘should be more caring about their environment’. The quotes underpin notions of ‘our’ and ‘their’ space; note Harry applying responsible behaviours as a collective, assimilating ownership and acknowledgement of shared space and shared responsibility (Mannion et al., Citation2015; Swaffield & Bell, Citation2012). That others would tarnish their locality and inflict poor hygiene is evident in Dimos’ quote; however, he also indicates that litter impacted on play both physically, by getting in the way, and psychologically as this infers filthiness and disease. These concepts of litter, hygiene, disease, lack of concern for others signalled to the children the potential for danger, indicating their assertion for responsibilisation. This was often expressed in concern for wildlife, which seemingly emerged from images of sea life entangled with waste, as evident in the following quotes:

Animal cruelty and animals getting trapped in plastic; there was something on Newsround, they get a dead bird and cut it up and there would be tons of plastic. It will get in its food and poisons them. It’s real dangerous to animals. Mark

If you didn’t recycle and left plastic bags, if that was blown into the sea, then turtles could eat the plastic bags because they think its jelly fish. We learned that in school. David

Litter shouldn’t be left right in the middle of this field. It was a surprise to me that nobody had picked it up. Something really small could get stuck inside it. If this glass got broken, that could be doing real damage to humans as well. If something like this got into the sea, that would be even more damage. Harry

Have you seen on Blue Planet just how much litter there is in the ocean? I was frustrated seeing animals dying from that. Dimos

Following on from litter, much concern for sea life and wildlife was evident. In the previous quotes, the pupils consider the consequences of littering as irresponsible, due to the opinion it impacts on wildlife and sea life. Note that Mark refers to this as ‘animal cruelty’, and that Harry expresses surprise that no-one had removed litter, both of them demonstrating shared responsibility, scaling from localised concern (Ozsoy & Ertepinar, Citation2012) to ownership (Mannion et al., Citation2015; Swaffield & Bell, Citation2012) of the wider impact and consequences of littering that emerges as a concern for nature (Cairns, Citation2017). Embedded perceptions regarding litter were not only borne out of Eco-school learning but were also informed by parental ideologies (Ritch & Brownlie, Citation2016b). For example: Milly said ‘My mum wants us recycling’; and Adam and his gran often collected litter and dog excrement when out in the locality, assuming responsibility for the cleanliness of the area. This illustrates horizontal scaling of key sustainability messages, and there were many photographs of household responsible waste disposal systems. In this sense, ownership transcended to all who lived in the home; it also became clear that shared ownership was evident in school behaviours and was expected in the wider locality, illustrating the scaling of sustainability practice. There were also expressions of how easy responsible waste disposal was:

You don’t really have to do much, except put [waste] in a certain bin. It’s not very hard and you could be helping a lot; it could affect so many things. Lara

As Lara illustrates, responsible waste disposal was considered an effortless task, something noted by many of the children. Waste management was an embedded behaviour, interconnected with the 3Rs, and had become an everyday practice, providing evidence of horizontal and vertical scaling of agreements to reduce emissions, local targets to increase recycling and reduce landfill, and businesses nudging sustainable practice. Assimilation has emerged from Eco-school and local councils providing street and home recycling bins. Mobilisation is encouraged through the ease of responsible waste disposal, and this transitioned into practice, scaling through hierarchical information sites. When asked why this contributed to the sustainability agenda, it was clear that the lasting impact of waste on the environment informed behaviours:

We try and help the amount of waste to go down, because there’s wastelands of rubbish that will take like hundreds of years to burn down. Robbie

[Litter] take years and years to disappear. Harry

Littering causes problems with animals in eco and food chains. Lara

The quotes illustrate that the pupils connect individual behaviours with the wider impact on the environment and how this assimilation of knowledge mobilises transitioning sustainable behaviours from micro to macro sites, which is evident in Lara linking environmental degradation as impacting on food chains and threatening the existence of humanity. This knowledge that resources take years to decompose and damage eco-systems partially led to reuse of what would normally be considered single-use materials or waste. Efforts to reduce single-use plastic included using your own bag when shopping, which featured in a few photographs. Liam, Ava, Robbie, Mark, Lara, and Milly had photographs of crafts they had made from unwanted waste, not just from paper, but plastic cables, coat-hangers and wood. Robbie had recently made a pillow with stuffing out of old fabric. Violet explained a novel use of carpet samples:

Little carpet samples in stores, we use those. They are free, and, instead of them going in the bin, we take them home and use them as placemats. We [also] use broken cups as little plant pots. Violet

Violet demonstrates that alternative everyday commodities can creatively be fashioned from materials that are no longer considered useful to avoid contributing to landfill. Similarly, Mark had photographs () of garden furniture that his brother (aged 11 years) had made from ‘an old bed’ and pallets.

It was our grandad’s idea, reusing an old bed [to make] two new chairs. This is the same [the photo shows a picnic table and two benches], our grandad made it as a surprise for my mum’s birthday, he made it out of a pallet. Mark

There were other examples in the photographs of crafting for play and recreating household objects from materials considered as waste. Sometimes this repurposing was influenced from Eco-school activities (Ozsoy & Ertepinar, Citation2012; Pirrie et al., Citation2006), and sometimes from family members. Combining learning through activities is, as Cairns (Citation2017) notes, an authentic way of embedding knowledge. The shared crafting of ‘hands-on’ activities that linked education with authentic sustainable experiences resonated with the pupils, particularly when this required imaginative responses. It is interesting that reuse was considered gift worthy, as second-hand gifting is not always socially acceptable; however, the novelty of sustainable reuse or upcycling in gifting is considered as putting more thought and effort into gift selection (Ritch, Citation2020). Reuse, therefore, is redirecting socially constructed notions of value. The desire to apply the 3Rs to behaviours extended to energy, water, and transport:

This is our reusable light. It’s powered when, the sun [shines]. It’s the solar system, it doesn’t use any power up. That’s a gas fire, that is not that good, it wastes gas. Luke

Make sure that you turn the tap off when you leave the room, so you don’t waste any [chanting] turn it off when you are not using it; turn it off when you are not using it. Ava

Cars take up quite a lot of energy; riding a bike is good for your health and for the ecosystem, and it’s much better because you don’t have to use petrol. Lara

It’s better to have buses than cars. It’s not good that some of them are not electric, but it still is better than cars. You could fit, maybe 50, people on a bus. With a car you can only fit a minimum of five people. If everyone went on buses, it would be a lot better for the environment. Or walk, as legs are not electronic. Milly

These quotes situate the assimilation of new behaviours that are responsive in protect natural resources, developed through activities in the Eco-school curriculum (Tourish et al., Citation2010). For example, harnessing nature to avoid energy use: using wind to dry clothes, or the sun to fuel light, rather than electricity. Note Ava’s chanting of ‘turn it off when you are not using it’, acting as though this notion was ingrained into her consciousness to trigger sustainable practice. There were also many photographs of buses and bicycles as a means to reduce emissions; as Milly explains, ‘legs are not electronic’ and therefore have no emissions, and buses enable the sharing of emissions for multiple users. Concurrent with research from Pirrie et al. (Citation2006), Eco-school curriculum was linked with ‘health and well-being’ of the pupils and ‘that of the planet’ (ibid, p. 1), as stated by Mark:

It’s just good to get outdoors, you could be working for hours inside and not seeing the sunlight or you could be outside growing and making use of the sun. Mark

Mark indicates the health qualities of nature, and collectively the quotes indicate that core messages of sustainability are part of the pupil’s everyday discourse and practice, illustrating that Eco-school pupils can act as transformative leaders to bring about positive change (Tourish et al., Citation2010). As reported by Ritch & Brownlie (Citation2016a; Citation2016b), albeit from the mothers’ perspective, the children were well voiced in sustainability. The eco-code constructed collaboratively between teachers and pupils had located the issues at a micro and macro level (Ozsoy & Ertepinar, Citation2012), informing practical purchase on everyday practice that was situated as contributing towards the overall sustainability agenda: from local to global and from self to others. It should be acknowledged that sustainability practice was embedded in household behaviours, supporting horizontal scaling between the child, their parents and the school, and informing new societal norms. Having set the scene with the children’s knowledge of sustainability and how this had inspired behavioural change in the home and the locality, the children also indicated that assuming responsibility and ownership for implementing sustainable principles was important, illustrating Ivory and MacKay’s’s (Citation2020) scaling construct of assimilation moving into mobilisation.

Mobilising responsibility and ownership

Progressing from practicing the 3Rs, there were many examples of the pupils thinking through their actions within the spaces they visited. This section captures some of the examples narrated in the interviews. Not all of the children provided examples of this, however it was evident that they were conditioned to mobilise sustainability by Eco-school learning. Examples of this include the creative reuse of waste materials, saving energy and minimising car use. As Generation Z are unique in having been socialised in sustainability throughout their school years, understanding how this forms perceptions and practice has implications for markets and marketing. What was interesting within this discourse was the focus on assuming responsibility, despite not being the perpetrator of littering, as Harry notes in the following quote:

That’s basically a pile of everything that I found in The Hermitage. [Interviewer: You gathered it up?] Yes, but we didn’t have anything to take it back. That’s why we left it like this. Maybe someone would pick it up and take it home. Harry

Harry and his friends had taken ownership of the littering in the park area and had gathered it all together in the hope that someone would remove it ().

As identified by Ozsoy and Ertepinar (Citation2012), involvement in designing an environmental review encouraged the pupils to care for their environment; as an illustration of scaling from assimilation to mobilisation, the pupils had decided which activities were important to them. Taking ownership was also evident in Robbie’s efforts to minimise waste:

That’s a polystyrene cup that I got about two years ago; at school they taught us that polystyrene will never decompose naturally. So, I just put ‘Robbie’s cup’ on it and drew some stuff on it and, I’ve been using it [since]. Robbie

What Harry and Robbie demonstrate is that they are thinking through their actions in order to reduce consumer impact on the environment. Learning assimilates within the Eco-school curriculum and mobilises as efforts for sustainable practice. From taking part in playground litter picks and school gardening, children are not only learning new skills and benefiting from time outdoors (Cairns, Citation2017; Ewert et al., Citation2005), but also learning about where food comes from and how to be self-sufficient. This was evident in Robbie’s efforts to grow flowers and vegetables; growing produce at home was also mentioned by David, Mark, Harry and Lara:

We are growing extra plants for food and everything, so we don’t have to buy things from Tesco’s which are being flown halfway across the country using so much fuel. Lara

Lara also offers practical purchase on practice that is underpinned by sustainability (Ozsoy & Ertepinar, Citation2012). This is akin to the authentic experiences reported by Cairns (Citation2017), that Eco-schools become a site for social and ‘consumer driven change’ that will lead to a ‘more sustainable society’ (ibid). While Cairns examined media reports on school gardening, the pupils informing this research provide evidence of Eco-schools driving sustainability as a social norm. The pupils report taking ownership for sustainability as consumers and citizens: caring for the locality, responsible waste disposal and reuse, as well as engaging with food production. Eco-school activities have developed new practice through shared identification of the problems, shared solutions and hands-on activities. As sustainable practice was considered as everyone’s responsibility (Springer, Citation2014) and easy to adopt, and there was growing criticism for those who were not engaging.

Critical activists

Certain behaviours that had been shaped through Eco-school learning had informed social norms, and those who did not comply were criticised (and this often was directed at adults). For example, Milly told a story of when driving with her mum and they had become held up by a refuge bin lorry, she observed one of the refuge workers attempt to upload a bin into the refuge lorry and some litter had fallen out. Rather than pick up the litter, and despite wearing protective gloves, the worker had kicked the rubbish aside. Milly was horrified and said:

That was really stupid because, well, it’s a bin, and obviously, you’re not meant to be doing that. You’re the opposite. You’re not meant to kick it around. Milly

Milly’s reaction illustrates her dismay that the very service that was meant to facilitate cleanliness in the area was contributing to littering, despite the proximity to the bin: ‘the opposite’ of what the role should entail. Mobilising ownership emerged from concern that human activity was destroying the environment, as expressed by Milly:

Half the world [is] littered and that’s how you know that you’re destroying earth because there’s so much litter. Milly

Drawing on the aformentioned themes of litter equating to squalor, a lack of hygiene and evidence of a lack of care for the environment, Milly is critical of the disdain for the environment by wider society. Her contempt was similar to Thunberg’s call to world leaders that younger generations would not forgive neglect for sustainability, an illustration of mobilising responsibility and ownership with an underlying condescension. Milly also noted that her teacher:

Really likes doing, she saw the world goals and she likes that, she respects that, she also respects the 3Rs. Every day after we leave [she] checks the [classroom paper recycling] bin for plastic bottles and takes them out and puts them in the [correct] bin. Milly

Milly refers to her teacher’s admiration for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs), so she is aware of the need for scaling sustainability. Milly was not alone in recognising the global imperative for sustainability, as the following quotes also support global recognition. In Milly’s example, the teacher is acting as a sustainability champion (Swaffield & Bell, Citation2012), not only educating but demonstrating responsible behaviours, and by doing so is gaining her pupil’s respect (Mannion et al., Citation2015). There is clarity in Milly’s perception as to who is a sustainability villain and who is a hero. Harry, who had previously gathered litter when out playing in the hope that someone would remove it, was actively trying to engage his school with cleaning the locality:

I’ve been trying to get my deputy head to organise a litter pick in Hermitage after I took all these pictures. She’s probably going to get a few people from each class to go and do a litter pick. Harry

Aware that his deputy head teacher was also engaged in progressing the sustainability agenda, Harry expresses confidence that she will support his efforts, again an illustration of teachers and pupils working together on a shared goal (Mannion et al., Citation2015). Harry’s idea for a litter pick had been inspired by ‘some kids [who] talked about watching it on Newsround’ [a children’s news programme on BBC]:

They were saying all we’re doing is destroying our world. That we’re just wasting time and that people should be trying to do stuff. Actually, I also saw this thing when loads and loads of people from a school went to a beach to pick up straws and then found all kinds of stuff. Harry

Harry expresses wanting to become more involved in ‘trying to do stuff’ to be part of the solution and avoid ‘wasting time’, providing more evidence of scaling, and information flows from vertical and horizontal sources (Springer, Citation2014): Eco-schools, parental influence, and TV programmes. Dimos mentioned being informed by the BBC’s Blue Planet series, and other children also referenced Newsround:

There was something on Newsround. Iceland, the shop, they promised to make sure there’s no plastic packaging and only [use] paper packaging, within the span of five years for every single product they have. That is definitely good and people have decided to write letters to other supermarkets, like Lidl and Tesco, asking them if it would be possible [to use] paper bags [too]. This has been going on for a while and we need to put a stop to it. Mark

Mark extends sustainability knowledge from Eco-school activities and home practice to business operations, applauding the move by a food retailer to reduce plastic packaging. He expresses support for sustainability measures as progressive and he also notes that other food retailers are being encouraged to adopt similar practices by consumers. A number of children related that they had been encouraged in class to write to their local Member of the Scottish Parliament about their concerns for the local area, which included their disquiet about littering. The pupils were active and vocal in what was considered as contributing to sustainability. In developing ownership and responsibility for their locality, as part of the Eco-school curriculum, the pupils are encouraged to adopt activism to advance the sustainability agenda. This is evidence of Eco-schools providing leverage for mobilising social structures and power relationships to challenge hierarchical structures, which will have implications for businesses and policymaking: something that organisations and politicians will need to be aware of (Antonetti & Maklan, Citation2016). The themes presented so far illustrate scaling sustainability through the assimilation of progressing Eco-school learning from individual behaviours to what is expected practice (Ivory & MacKay, Citation2020). The pupils are not only championing sustainability (Swaffield & Bell, Citation2012), but mobilising their advocation of what are socially acceptable behaviours in wider society. Hierarchical assumptions are made about those who are part of progressing sustainability, and those who perpetrate unsustainable behaviours: sustainability heroes and villains. The aim of adopting a scalar approach is to provide momentum for transitioning sustainability (Ivory & MacKay, Citation2020). As previously established, the core message for sustainability was amplified through scaling individual and local behaviours to acknowledge macro issues of sustainability, leading to the final theme of scaling globally.

Scaling globally – to ‘save the planet’

Scaling was evident through locating responsibility from individual to collective practice as necessary to ‘save the planet’ (Mark). This discourse of wanting to belong to progressing sustainability was also displayed as pride in being part of the movement. For example, some of the pupils mentioned the Eco-school flag, which featured in some photographs, as illustrating their commitment to sustainability; for example, Ava said ‘our giant flag says eco, it’s cool’. The literal visualisation of being ‘eco’, as a school community, signals belonging to the wider sustainability movement, and their awareness that this links into a global community, not just of Eco-schools, but through programmes such as Newsround and Blue Planet, as well as through the UNSDGs. What made the global issue relatable was that the same global messages were pertinent to their local area, as identified through the Eco-code developed by teachers and pupils:

I was watching this thing and it was about the world goals for 2030 and one of them was no poverty and [in poor] places there’s rubbish everywhere. Milly

Developing countries will experience the impact of climate change before developed countries, due to geographical location, reliance on agriculture for economic development, and their lack of finance to improve infrastructure (United Nations, Citation2020). Imagery of inequality disparities were observed and equated to squalor; given the pupils’ disgust for litter (as illustrated in quotes), this imagery evoked concern. Milly goes on to make the connection between what occurs in her locality and how this impacts globally:

The sea is large, and you don’t know where it ends. And things live in the sea, it is not empty. Milly

What Milly indicates is her higher awareness that the planet is connected, geographically and through eco-systems; she understands that what occurs in developed countries impacts on developing countries and vice versa. She further expands on this understanding by acknowledging the link between the environment, animals and humans within food chains:

I watched on Newsround about how it’s damaging not only our environment but a lot of animals. Animals, start everything. Some people eat animals. Do you know what I mean? Milly

As Milly notes, the intersectionality of human behaviour and the environment are reflected in links between sustainability, poverty and inequality disparities, and the pupils’ illustrated knowledge of the critical urgency for sustainability. For example, Luke had photographs of abnormal weather patterns, noting that extreme weather conditions were evidence of accelerated climate change (NASA, Citation2021). Scaling sustainability was not only considered as expanding globally, but the pupils were also mindful of future generations and their responsibility towards those who would come after them; this captures the spirit of sustainability of meeting ‘the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’, as defined by the World Commission on Environment and Development (Citation1987).

That’s a picture of some trees and flowers and just how many trees are in Leith Links. It’s good because people can have a nice walk and you can see how nice it is. You wouldn’t want to be destroying these trees so that one day, there might not be any of them for your great, great, great grandchildren ever to see them. That would be a shame. Lara

Lara is projecting forward, concerned that the pleasure she finds in nature may not be available for future generations. In this, the pupils assume responsibility and ownership for the health of the planet, acting as custodians. Although none of the children mentioned Greta Thunberg, their sentiment is similar in that they are taking responsibility for scaling sustainability and that they are critical of adults who are not participating in advancing sustainability. There was also a sense of urgency in their concern, as summarised by Violet:

The planet is dying, we are terrible for our planet. The planet hates us. We have got to be nice to the planet, so it doesn’t die quicker. Violet

Concluding discussion

This exploratory research sought to investigate how the Eco-school curriculum enabled scalar information flows to assimilate learning and understanding of sustainability that can transition into everyday practice, combining a novel theoretical framework with a cohort of children, both of which advance knowledge in sustainable marketing literature. This paper offers contributions to theory, marketing management and public policy. Although academic literature has examined sustainable consumer behaviour for over two decades, the voice of children has been underrepresented (Chitakunye, Citation2012), despite their role as future guardians of the planet, and as future consumers. There has also been little attention given to exploring children’s experience of the Eco-school curriculum and how this informs their construction of sustainability and related practice, despite the global implementation of Eco-schools over the last 27 years and childhood being a pivotal time for socially constructing attitudes and behaviours (Cairns, Citation2017; Davies et al., Citation2020). Collectively, there are four implications for theory. Firstly, this research presents scaling through a new conceptual lens by examining the Eco-school curricula, both theoretically and empirically, as a means to embed responsibility in addressing climate change, building on previous research from organisational settings (Ivory & MacKay, Citation2020; Springer, Citation2014; Swaffield & Bell, Citation2012). The literature review applied Eco-schools to a scalar framework to exemplify how connecting vertical and horizontal flows constructively can promote sustainable lifestyles (Springer, Citation2014); to direct sustainable behaviours within neoliberal markets (Kemper & Ballantine, Citation2019); and to embed responsive practice (Davies et al., Citation2020). While this may not impact as comprehensively as implementing vertical sustainability scaling, it is responsive to growing consumer concern for the climate crisis, and illustrates how marketing management can contribute to scaling awareness and responsiveness for sustainability.

Secondly, the benefits of examining scaling as a means to infuse sustainability are evident from vertical (Eco-school curriculum) and horizontal flows (family, peers, media), allowing for a holistic understanding of how messages are consolidated and to encourage ownership. Empirical evidence of children’s voices and listening to their narrations illustrates that multiple influences led to the construction of their sustainability understanding: from Eco-Schools, their parents and extended family, to wider media. This is a new discourse in marketing literature. Their influences were idiographic, based on their personal interests, exposure to experiences and what captured their attention; yet, the messages were underpinned by a core and consistent message towards reducing contributions to climate change as learned within Eco-schools. Imagery played a role, as the children’s narrations wove imaginative stories around their photographs and they adopted restorative measures, illustrating their understanding of responsibilisation for protecting eco-systems and wildlife, and their desire to play the hero. Sustainability is intrinsically linked with good housekeeping and care for planetary life. Scaling sustainability illustrates that responsibility for sustainability falls within governance, business and consumer/citizens (Spicer, Citation2006) and rather than displacing neoliberal markets, individual responsibility is encouraged through social marketing, both by governments and businesses. This develops assertions made by Kemper and Ballantine (Citation2019) that marketing can influence behaviour and practice without being profit-oriented and that consumers can lead change, as evidenced in the plastic bag example earlier. This research suggests that young people are empowered with knowledge to lead change which may result in them demanding more from businesses and policy makers, as indicated next.

Thirdly, findings advance Ivory & McKay’s previous framework of assimilation, mobilisation, and transitioning: assimilation is understood as a baseline where children, at worst, are socialised to conform to sustainable practice during their formative years. Even if this is not practiced at home, seeds of sustainability have become an embedded discourse to be mobilised when triggered. While previous research has examined influences of socialisation in formative years, and how intergenerational families share practice around sustainability (Davies et al., Citation2020; de Faultrier et al., Citation2014; Singh et al., Citation2020), this has not included children’s independent conceptualisations of sustainability. While Eco-schools could introduce children whose parents do not embody concern for the climate crisis to sustainable practice, what was of interest in this paper was the intersections of influence, from family, school and external media channels that benefits from adopting a multi-scalar approach. Note that the quotes from Greta Thunberg were obtained from Newsround, a children’s BBC news programme that the children accessed as part of Eco-school learning and in their own time too. This programme had informed their knowledge of sustainability, along with knowledge of which businesses were being responsive. For example, Mark had learned of the responsiveness of UK food retailer Iceland in reducing single-use plastic packaging. He is looking to markets for responsive solutions, and suggesting they may need to be ‘nudged’ by consumers to address sustainability concerns.

As children have been neglected in sustainability marketing literature, this new contribution has implications for markets and marketing management. Examining mobilisation illustrates the ways in which children assume responsibility for sustainability; even when actions seem insignificant, such as reusing a polystyrene cup, it is an illustration of them considering what materials are used to make commodities and what implications this has for the environment in terms of use and disposal. As the first generational cohort to be educated in sustainability from an early age, this has implications for markets and marketing. Much has been made of millennials being the first digital natives and how this has transformed their practice and expectations (Francis & Hoefel, Citation2018). This research contributes to the literature by consolidating what children know about sustainability and how it informs their practice. Marketing management decisions should take this into account.

Yet, it is the transitioning phase that is most illuminating in the children’s discourse: the disdain for those not conforming was evident, and aligns with newly emerging literature examining activism and criticism for greenwashing in older members of Generation Z (Djafarova & Foots, Citation2022), leading to implications for marketing management. Although none of the children mentioned Greta Thunberg, Newsround focused on her activism as an example of how children can become involved in sustainability campaigning; the evidence from this research illustrated that the pupils were incentivised by the programme to instigate campaigns and responsibility for sustainability, such as Harry organising a litter clean-up with his school. Similarly, much like Greta Thunberg, the children expressed frustration that adults were not taking responsibility for the environment, evident in their disgust for litter in the streets and their expressions of how easy it is to dispose of waste responsibly. When Milly expressed disdain that adults perpetrated unsustainable behaviours, this was similar to Thunberg’s accusation that ‘the eyes of all future generations are upon you’! Concurrently, there was criticism of those whose behaviours hinder sustainability (the villains) and who act irresponsibly and this was often directed towards adults. This youthful critical activism has not been identified previously in research; yet, it has the potential to destabilise neoliberal politics and markets. Given the lack of implementation of vertical scalar structures that will address the climate crisis, marketing sustainability will become more important, especially as younger consumers have been attuned to sustainability in their former years.

This demonstrates the fourth contribution to the theory of multiple scaling sites working together, as exemplified in the plastic bag case mentioned earlier, calling into sharp focus the need for public policy to be more attuned to public awareness and concern for climate change that is not reflected in regulation. Marketers increasingly address children’s preferences for products and brands and the notion of ‘pester power’ is often considered as obtrusive (Lawlor & Prothero, Citation2011); but perhaps ‘pester power’ with a social conscience, and acknowledgement of the need for sustainability will be a positive move towards counteracting the negative assumptions of consumer culture and improving sustainable behaviours within households (Ritch & Brownlie, Citation2016b). Responsibilisation could lead to consumer resistance and demand power (Luchs et al., Citation2015), where businesses not demonstrating sustainability will fall within this critical gaze, as will politicians considered to be neglecting their responsibility to implement sustainability. More importantly, it embeds climate change as an issue that requires new market structures, and as such young consumers’ moral outlook will shape business and organisational practice (Antonetti & Maklan, Citation2016) to adopt more sustainable ways of production and retailing to obtain competitive advantage (horizontal scaling) (Pecoraro et al., Citation2021). Potentially, this cohort will also influence policymakers to progress the sustainability agenda through regulation at an international level (vertical scaling). The pupils identified as global citizens, assuming citizenship responsibility that sometimes manifested in enterprise. What this demonstrates is a sustainability engaged cohort with fertile imaginations and the potential to become future transformative leaders (Swaffield & Bell, Citation2012). As the children mature and their access to media expands, this may further stimulate activism and concern. For example, the popularity of TikTok could be a platform for disseminating sustainability imagery. Politicians may currently be concerned for neoliberalism and free market choice; however, future generations may demand legislation that protects the environment and sea life and wildlife – and ultimately humans too.

Limitations and future research