Abstract

This article focuses on the influence of state-led urban redevelopment on the place attachment of deprived and old homeowners living in danwei communities that are facing demolition in Shenyang, China. It investigates lived experiences through in-depth interviews with homeowners in the context of the pre-demolition phase, i.e. an inevitable prospect of having to move out. The article reveals how these homeowners cleverly mobilize local resources, such as strong social bonds, low living costs, flexibility on space use and good neighbourhood location to cope with their life constraints, which is translated into their strong neighbourhood attachment. However, various forms of neighbourhood decline have decreased their quality of life. Meanwhile, they soon have to move due to the impending demolition of their neighbourhood. State-led urban redevelopment, therefore, confronts those deprived residents with a dilemma concerning their strong neighbourhood dependence and their desire for better living conditions. The impending neighbourhood demolition uncovers accumulated social issues in danwei communities in the context of market reforms and institutional changes in current China, such as the emergence of deprived social groups and their struggles for better housing.

1. Introduction

Neighbourhood redevelopment projects often involve the large-scale demolition of houses and the forced relocation of residents (Popkin, Citation2010; Posthumus et al., Citation2013). Forced relocation is highly frequent in urban redevelopment projects in China. It is estimated that between 2008 and 2012 approximately 12.6 million households were affected by the redevelopment of declining neighbourhoods initiated by the central government of China (Li et al., Citation2018; MOHURD, Citation2013). Previous studies in the United States and Western Europe have shown that the demolition of a neighbourhood involves more than tearing down physical buildings. For those residents who have been living in a neighbourhood for a long time and/or are poor, it can cause dramatic changes to the daily routines and living strategies that they have developed in their neighbourhoods over a long period of residence (Manzo et al., Citation2008; Vale, Citation1997; Popkin, Citation2010). Demolition and the associated forced relocation are especially threatening to less mobile residents, who are often low-income, aging, or have severe mental or physical problems (Fried, Citation1963; Gilroy, Citation2012; Manzo et al., Citation2008; Popkin et al., Citation2004; Posthumus & Kleinhans, Citation2014).

Place attachment is associated with the affection residents have for their neighbourhood (Anguelovski, Citation2013; Fried & Gleicher, Citation1961). The existing literature presents various findings regarding the influence of urban redevelopment on the place attachment of residents. Some argue that the extent to which urban redevelopment affects place attachment is closely related to the lived experiences of residents (Manzo, Citation2014; Manzo et al., Citation2008). For instance, several studies report that demolition of public housing disrupts place attachment, as residents are forced to leave their familiar environment and social networks (e.g. Fried, Citation1963, Citation2000; Fullilove, Citation1996; Manzo et al., Citation2008). However, other research has found that some residents may be less attached to their neighbourhoods due to the deterioration of various aspects, such as physical decline or high population turnover (Bailey et al., Citation2012), with strong place attachment not necessarily translating into a strong willingness to stay (Wu, Citation2012).

The diverse research outcomes related to residents’ place attachment and the impact of urban redevelopment may be closely related to the ambivalent feelings that residents may have about their neighbourhood experiences. Residents can feel attached to their neighbourhood while neighbourhood decline may simultaneously damage their attachment and stimulate them to leave. It appears that ambivalence in the neighbourhood experiences of residents has not yet been adequately studied in relation to the influence of urban redevelopment on residents (Manzo, Citation2014; Vale, Citation1997). In addition, previous literature has focused on place attachment during and after forced relocation in Western Europe and the United States, or merely in deprived neighbourhoods, without any indication of whether they have been redeveloped or not. There is a lack of research on residents’ place attachment in declining neighbourhoods in the pre-demolition/pre-relocation phase (Goetz, Citation2013; Manzo et al., Citation2008; Tester et al., Citation2011). This gap is even larger in research focusing on China, despite its large-scale demolition of dwellings and the forced relocation of millions of residents (Li et al., Citation2018, Li et al., Citationforthcoming). Moreover, the literature from the US and Europe almost exclusively concerns redevelopment of public or social housing, while redevelopment in Chinese cities targets particular declining neighbourhoods with private housing. Most long-staying homeowners in these places are old and/or deprived residents. The specific residential composition and the differences in ownership in redevelopment areas are bound to have major implications for the impact of impending relocation on residents’ lived experiences and place attachment.

Inspired by these concerns and knowledge gaps, this article aims to investigate the lived experiences of old and relatively poor homeowners in declining danwei communities that face demolition in Shenyang, China. The article highlights (1) aspects of the declining neighbourhoods that residents are attached to and why, (2) the ambivalence in their place attachment, and (3) the influence of the impending demolition and forced relocation on their place attachment. In the article, residents' perceptions on both the impending demolition and situation after demolition are reported. Neighbourhood demolition was about to happen soon after the in-depth interviews with residents. In other words, residents’ perceptions reflect the pre-relocation impacts on their place attachment, based on a combination of expectations regarding the near future relocation situations with their lived experiences in the current situation. The following section provides a theoretical background that locates place attachment in the context of declining neighbourhoods facing urban redevelopment. Section 3 introduces the research area and methods, while Section 4 analyses the results from the interviews, focusing on residents’ lived experiences and dimensions of attachment. Section 5 explains the impacts of the impending demolition and forced relocation on residents. Section 6 discusses the empirical findings by placing them in the wider context of structural economic transitions, market mechanisms and urban redevelopment in China. The final section offers our conclusions.

2. Place attachment, neighbourhood decline and urban redevelopment

2.1. Place attachment in declining neighbourhoods

Place attachment is defined as an affective bond between people and places (Altman & Low, Citation1992; Giuliani & Feldman, Citation1993; Hidalgo & Hernández, Citation2001; Lewicka, Citation2011; Scannell & Gifford, Citation2010). In the context of residential place, the development of place attachment is closely related to residents’ living experiences within their neighbourhoods over time, ie, how a neighbourhood can functionally and emotionally meet residents’ demands (Corcoran, Citation2002; Jean, Citation2016; Livingston et al., Citation2010; Scannell & Gifford, Citation2010). Some research has highlighted the importance of place attachment for residents living in declining neighbourhoods. For instance, the material and spiritual support that residents gain from a declining neighbourhood can alleviate the life constraints they must cope with, such as poverty, unemployment or mental and physical disability, which contribute to their social, physical and economic dimension of place attachment (Anguelovski, Citation2013; Brown et al., Citation2003; Corcoran, Citation2002; Fried & Gleicher, Citation1961; Wu, Citation2012). Other studies indicate that an involuntary move can be disruptive to the residents involved as it interrupts their routines and social networks, and causes a discontinuity to their place identity (Brown & Perkins, Citation1992; Fried, Citation2000; Manzo et al., Citation2008). For example, Fried (Citation1963) reveals the grief and affliction felt by residents after the forced relocation out of their home in working-class communities.

However, these studies have not paid adequate attention to residents’ ambivalent feelings towards their declining neighbourhoods as a result of negative lived experiences, which might affect their perceptions of (impending) neighbourhood redevelopment and in turn their moving behaviour (Manzo, Citation2014; Oakley et al., Citation2008). Vale (Citation1997) used the concept of ‘empathology’ to refer to ambivalent attitudes of residents towards an environment that is both ‘a source of empathy as well as a locus of pathology’ (Vale, Citation1997, p. 159). He discussed the ambivalence in the experiences of residents who are living in declining public housing communities, demonstrating that residents are both socially and economically dependent on their neighbourhoods, while their quality of life is negatively affected by various forms of neighbourhood disorder, such as drug dealing and gang violence (Vale, Citation1997). In fact, the development of place attachment can be seen as an outcome of residents’ cost–benefit evaluation about their positive and negative neighbourhood experiences (Bailey et al., Citation2012; Brown & Perkins, Citation1992; Brown et al., Citation2003; Giuliani & Feldman, Citation1993; Manzo, Citation2014; Wu, Citation2012). Residents in declining neighbourhoods are likely to have negative lived experiences based on various forms of neighbourhood decline, which cause degradation of their quality of life, disrupts residents' sense of place and further drive some of them to leave (Feijten & Van Ham, Citation2009; Livingston et al., Citation2010; Wu, Citation2012).

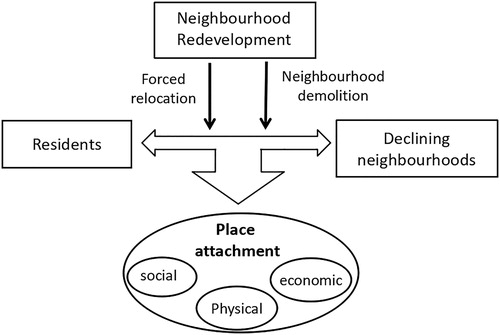

Recognizing this ambivalence in residents’ lived experience and place attachment in declining neighbourhoods may help us clarify vital issues, revealing which dimensions of place attachment – and to what extent and why – are significant to residents and how urban redevelopment can affect their place attachment. Residents’ interaction with the physical, social and economic aspects of neighbourhoods partly determine their dependence on and emotional affection with their neighbourhoods, thus constituting social, physical and economic dimensions of place attachment (Bailey et al., Citation2012; Corcoran, Citation2002; Jean, Citation2016; Lewicka, Citation2011; Manzo et al., Citation2008; Oakley et al., Citation2008; Ramkissoon et al., Citation2013; Stokols & Shumaker, Citation1981; Vale, Citation1997; Windsong, Citation2010). The physical dimension of place attachment is achieved through residents’ interaction with the tangible physical attributes (e.g. facilities, dwelling quality and sanitation condition) of a neighbourhood, which meet their needs in relation to surviving and achieving their longer term goals (Fullilove, Citation1996; Lewicka, Citation2011; Scannell & Gifford, Citation2010). The social dimension of place attachment is on the basis of the cultural and social attributes of a neighbourhood (e.g. numbers of acquaintance, mutual help, neighbourhood socio-economic status), which generates a sense of belonging, familiarity and affection (Fried, Citation2000; Lewicka, Citation2011; Relph, Citation1976; Scannell & Gifford, Citation2010). The economic dimension is developed through economic benefits that residents gain from their neighbourhood (e.g. neighbourhood-based income and living cost) by living close to job opportunities, paying low rent or running neighbourhood-based businesses (He et al., Citation2010; Luo, Citation2012; Manzo et al., Citation2008).

This article focuses on the influence of urban redevelopment on residents at the pre-demolition/pre-relocation phase in China, through revealing the ambivalence in the physical, social and economic dimensions of residents’ place attachment (as shown in ). Currently, only a small body of research focuses on the influence of urban redevelopment on residents’ place attachment in the pre-demolition/pre-relocation phase (Manzo, Citation2014; Oakley et al., Citation2008; Tester et al., Citation2011; Tester & Wingfield, Citation2013). This means that there is a lack of knowledge about an important phase – the pre-demolition stage – of urban redevelopment (Kearns & Mason, Citation2013), which limits our capacity to develop a deeper understanding of the overall impact of redevelopment on residents, especially in relation to issues such as time and context (see also Kleinhans & Kearns, Citation2013).

2.2. Place attachment and urban redevelopment in Chinese cities

This article investigates the place attachment of old and relatively poor residents in declining danwei communities facing demolition in Shenyang, a Chinese city. Danwei communities were originally established to reside employees from state-owned enterprises (SOEs), collectively owned enterprises (COEs), government departments or institutions such as universities. Previous studies of residents’ attachment to declining neighbourhoods have usually focused on renters who are living in public or social housing in Western Europe and the US. The resulting body of knowledge may not be applicable to the Chinese situation because of the differences in development history, social composition and the physical environment of neighbourhoods in China and Western countries.

In the socialist era, residents of danwei were socially, physically and economically dependent on these communities. The danwei contains sources of employment associated with industrial production and other enterprises, and also provides those employed with other services and social welfare (Bjorklund, Citation1986; Bray, Citation2014; Wang & Chai, Citation2009). Danwei communities provide residential accommodation to danwei employees in a relatively homogeneous social space, where neighbours are also working colleagues. Residents living in danwei communities thus often have strong social capital and close relationships due to the long length of residence and shared work and social experiences. In addition, the residents develop a strong place identity embedded in the danwei system because ‘A danwei identity hinders the freedom of mobility of workers, because mobility without permission (from a worker’s danwei) will cause the loss of personal identity (income, position, etc.)’ (Lu, Citation1989, p. 77).

However, under market transition and rapid urbanization in China, danwei have experienced disinvestment and decline at multiple levels (He et al., Citation2008; Wu & He, Citation2005). Also, most danwei have retreated from these neighbourhoods by providing housing, employment and even community management. Population turnover, social stratification and residential changes have become more common in these neighbourhoods as well, with those who have more resources moving out, while those who are less mobile, due to poverty or ageing, remaining trapped (He et al., Citation2008). Also, many residents who were employees in danwei became unemployed due to the collapse of these companies. These neighbourhoods have increasingly become enclaves characterized by a migrant population of renters on the one hand, and homeowners in the aged or low-income categories, on the other hand (He et al., Citation2008). These transitions have diverse impacts on homeowners’ sense of place, residential satisfaction and residential mobility. Some research has revealed that place attachment and social interaction remain stronger in these neighbourhoods than in newly built neighbourhoods, however this strong place attachment does not contribute to the residents’ willingness to stay (He et al., Citation2008; Wu & He, Citation2005; Wu, Citation2012; Zhu et al., Citation2012). The strong sense of place alongside an intention to move reflects ambivalent feelings of residents in relation to their neighbourhood experiences.

In China, numerous old neighbourhoods (not only danwei communities) have been subject to demolition, initiated by governments and/or developers (Hin & Xin, Citation2011; Li et al., Citation2018). The dilapidated danwei communities investigated in this article are involved in state-led national-scale Shantytown Redevelopment Projects (SRPs, Peng-hu-qu in Pinyin), which aim at improving the living conditions of low- and middle-income residents in declining neighbourhoods (MOHURD, Citation2013). These neighbourhoods will hence undergo neighbourhood demolition and the forced relocation of their residents. This will have a major impact on these neighbourhoods and their residents. In this article, we focus on how SRPs and impending forced relocation can affect the place attachment of the long-staying homeowners in these declining danwei communities at the pre-demolition stage. We investigate both their lived experiences in the current situation, and their expectations regarding the relocation process and the resulting housing situation in Section 4 and Section 5, respectively. The next section will introduce our research area, data and methods.

3. Research area, data and methods

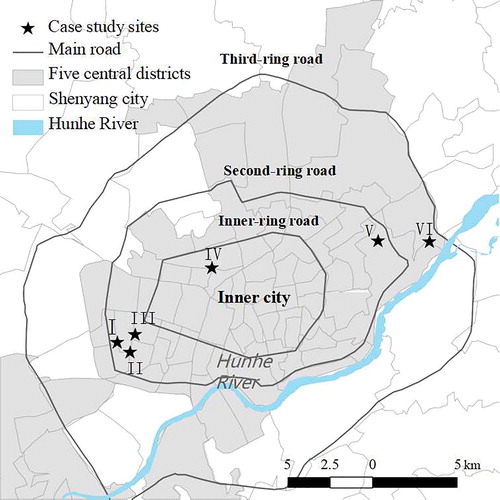

The danwei communities in our research are located in the city of Shenyang in Northeast China (). Shenyang is a typical old industrial city, and has been called the ‘Ruhr of the East’. The city once had many state-owned enterprises and danwei during the era of centralized economic planning. Most of them are located in the old industrial areas. Shenyang, therefore, had – and still has – a lot of industrial workers and danwei communities. The empirical basis for this article consists of in-depth interviews conducted in March, April, September and October in 2015. We interviewed homeowners who were long-term stayers in a number of neighbourhoods in Shenyang that will be demolished according to the national redevelopment policy – SRPs. and show the location and information of the six danwei communities which have been included in our fieldwork. Neighbourhoods I, II, III and IV were affiliated to state-owned manufacturing enterprises for machine or rubber production and are located in urban areas. Neighbourhoods V and VI are located in a suburban area. Neighbourhood V was affiliated to a government apparatus (prison). Neighbourhood VI belonged to a state-owned farm, and the residents mainly conducted farming activities and were involved in agricultural production. These neighbourhoods were constructed during the socialist era around the 1950s–1970s by danwei organizations to reside their employees. These danwei have resigned their responsibility on neighbourhood management to local housing bureaus during SOE reforms around 2000. Meanwhile, many state-owned enterprises in Shenyang went bankrupt and their workers (residents from our neighbourhoods) were laid-off. Some original residents have moved out because they could afford so as they successfully adjusted to the economic reforms and found business opportunities in the market. However, the residents who stayed in these neighbourhoods have mainly been relying on their pension or basic living fees provided by their danwei and local government.

We recruited respondents from the latter group of residents (homeowners who were long-term stayers) through a combination of snowball sampling and door knocking. All of the interviews were conducted face to face using a semi-structured interview schedule. A total of 33 interviews were conducted in these danwei communities (see ). The physical conditions of the dwellings and neighbourhoods have severely deteriorated. The dwelling sizes of the respondents ranged from 20 m2 to more than 100 m2. The residential composition of these neighbourhoods is becoming increasingly heterogeneous, including homeowners who have lived there all of their lives, and renters who are mainly from rural areas and who now work as construction workers, porter, servants etc. In this research, we focus on the homeowners who have not (yet) moved out the danwei communities. As shown in , they have been living in these neighbourhoods for at least ten years, in some cases, for their whole life (more than 60 years). The respondents themselves and/or their family members used to work in the danwei. The interviewed residents reported that they regard themselves as belonging to the most deprived socio-economic group, and that their poor economic situation has prevented them from getting better dwellings in better neighbourhoods. As shown in , 23 respondents are more than 55 years old. They have been retired and can get a pension ranging between 1800 and 3000 RMB/month (around €233–€390). Those respondents who are younger either have part-time jobs or are self-employed. Respondents who can rent out rooms to migrants earn around 200 RMB per month per room (around €26). Some of the interviewed households have unemployed family members due to a lack of education, a disability, serious illness, or a lack of job opportunities. Their income can just meet their basic living costs and medical treatment. These low-income households cannot afford new dwellings to rehouse their whole family, as the average selling price of commercialized residential dwellings is around 6400 RMB per square meter (around €831) (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2015). The total amount of interviewing time is 21 h, and the average interviewing time is 41.9 min (median: 39.6 min). The interview time differed quite substantially, with the shortest interview taking 15 min and the longest interview taking 2,5 h. The ages of the respondents range from around 30 to more than 80 years. Some respondents were approached more than once to obtain supplementary information.

During the interviews, questions were asked about topics such as family and moving history, moving intentions (regardless of the impending relocation), residential satisfaction, various dimensions of place attachment, perceptions of the impending demolition and recent neighbourhood changes. All interviews, with the exception of three (either because of the author getting no permission to record or due to a recording device failure), were recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim, enabling content analysis of the transcriptions. In addition, the emotions and tones of voice of the respondents were noted while analysing the transcription. As a preparation for the coding procedure, the transcriptions were read and listened to several times to gain familiarity with the stories and mentioned elements related to place attachment and lived experiences. Atlas.ti was then used to code and categorize these concepts and elements in relation to residents’ place attachment into social, economic and physical dimensions. For example, friends, relatives, family members, acquaintances and mutual assistance were coded as social dimensions of place attachment. Information about and comments on the physical environment, such as dwelling quality, toilets, roads, transportation, schools and other neighbourhood features were grouped under physical dimension. Economic aspects such as income, pension and living costs in the neighbourhood are categorized as the economic dimension. To guarantee the anonymity of respondents in the analysis, the quotes are accompanied by gender, age category and fictitious names.

4. Lived experiences and place attachment in declining danwei communities

4.1. The ambivalence in the social dimension of place attachment

High population turnover and increasing social heterogeneity appear in danwei communities against the context of neighbourhood decline, rapid urbanization, housing market development and the dismantling of danwei system, causing a shrinking of social networks among our respondents. Many of their original neighbours have moved out of their neighbourhoods or died, while many renters, who are mostly migrants from rural areas have moved into the neighbourhoods, in search of cheap apartments. This population turnover has disrupted the established social networks of the long-staying residents. Many respondents, especially the older ones have strong negative opinions about the renters. They regard migrant renters as outsiders who lack a place-based identity. This might be because that these renters are not homeowners, and their family history is not embedded in the neighbourhoods. Therefore, they perceive that migrant renters lack a sense of rootedness since they will neither stay in the neighbourhood for a long time nor will they consider the neighbourhood as home. Moreover, most migrants are from rural areas and are participating in low-end labour market. Their relatively low socioeconomic status further contributes to our respondents’ negative opinions about them. Many consider these migrants to be the cause of a neighbourhood deterioration and of enhanced levels of crime. They distrust these renters and feel unsafe to live together with them.

The old neighbours have already moved out … I don’t know them [renters] … I am not able to put stuff outside [any more] … my cabbages were stolen! … These old neighbours won’t steal cabbages. I know who stole them. (Meng, 80s, male, resident of Neighbourhood II for more than 30 years)

Therefore, many respondents try to avoid contacts with the migrant renters. In combination with the deaths of old acquaintances and moving out of other original residents, their social networks within these neighbourhoods are subject to continuous shrinkage.

Long-term stayers retain their (remaining) strong social bonds with each other within their enclosed social networks. Some stayers reported a family-like relationship with their neighbours because they have grown up in the same neighbourhood and worked in the same place. They maintain their frequent interaction, including chatting, playing mahjong or providing mutual assistance. Moreover, although the danwei system has disintegrated over time, it still has a unique social and cultural meaning, and continues to influence the respondents. Their affiliation to danwei used to provide them with a job for themselves and/or their family members. Respondents reported that other people know who they are and what they do, just by telling them the name of their danwei community. Also, their family history and that of their neighbourhood are intertwined with each other and have developed into collective memories and neighbourhood-based place identity. In the context of the impending redevelopment, most respondents think they can still maintain their current social networks after demolition if local governments provide them with in-situ relocation opportunities.

My parents worked in this danwei … Then I came back to work in this danwei. At that time, it was common [in danwei] to succeed your parents’ positions … (Hui, 60s, female, retired with a pension, resident of Neighbourhood VI for more than 60 years)

Every evening about ten households came out and ate their dinner at the corridor… they walked around and shared food with neighbours from this side of the corridor to the other … It used to be such a great time here! Mr Liu is the joke master of this floor, … These guys were quite active and humour! Their jokes can make you laugh for the rest of a day…. It used to be a lot of fun here! (Wen, around 70s, female, 50 years’ residence in Neighbourhood V)

Meanwhile, the social bonds among the stayers are enhanced because they have similar experiences and a similar disadvantaged socio-economic status, including poverty, unemployment, ageing or disability, contrary to their old neighbours who have moved out, often as a result of upward social mobility. This has made them develop a sense of belonging to the same social group as they understand each other’s hardships compared with the out-movers. The stayers’ shared social resources (e.g. mutually physical and social assistance), which have developed on the basis of the long-term residence, help to relieve some of the constraints and hardships in their daily lives. For example, Mei (60s, female) had been living in a small apartment in Neighbourhood V with her family for about 30 years. Her husband was seriously ill and the family relied on her pension to make ends meet. She appreciated the mutual support in the neighbourhood as “they [neighbours] treat me very well. They help to look after my husband when there was nobody at home…” . She also felt not judged as neighbours appear to understand each other’s hardships:

80 per cent of the stayers are in poverty … Some families are in difficult situations, just like us: some have health issues and [even worse] don’t have a pension or insurance; some have mental illness …Her son is addicted to drugs…She [a neighbour] doesn’t need to ask for a favour, and I will help her … You cannot ignore her situation, because you know she is suffering … You [I] have to help her…

However, many respondents also reported the decrease of their sense of place about their neighbourhoods, which is related to the dismantling of the danwei system, the influx of migrants, the increased social inequality and the perceived decrease of their own socioeconomic status. Many respondents regard themselves as the most deprived households compared to those who have moved out of the neighbourhoods. Many felt that their self-esteem and prospects are being undermined due to the decline of their neighbourhoods and their deprived situation. One respondent (30s, male) said he was attached to the neighbours and felt convenient living in Neighbourhood I. However, he also told that the neighbourhood stigma had a negative influence because nobody would like to marry a guy and then move into a declining neighbourhood like this.

4.2. The ambivalence in the economic dimension of place attachment

As mentioned earlier, most respondents are economically deprived. They live in their current neighbourhoods because they cannot afford to move out. Those who have retired or were laid-off at an early age from their danwei can rely on a pension which ranges from approximately 1800 RMB to around 3000 RMB per month (around €233–€390). However, currently, their income is just sufficient to maintain their basic living costs. In order to make ends meet, they have developed coping strategies by clever use of neighbourhood resources. This echoes a Chinese saying: ‘kai yuan jie liu’ (tap new sources and reduce expenditure). For instance, some older respondents go around to pick up firewood for heating through which they can save money.

These neighbourhood-based economic strategies and opportunities have become part of the respondents’ daily life. For example, some respondents rent out rooms (rent price around 200 RMB per month, which is around €26), have part time jobs or run restaurants or supermarkets, which have become the dominant source of income. Jun (40s, male) had been living in Neighbourhood VI for about 20 years. Recently, he built many rooms in his yard and above his own rooms to rent out to incoming migrants from rural areas. He considered this as an achievement that has increased his self-esteem, as he is able to make a living on his own rather than rely on government subsidies.

Most respondents reported they need much less resources to maintain their life in the declining neighbourhood than they would in the high-rise apartments which will be made available by the local government as part of the relocation process. First of all, they now have to pay little, if any, housing management fees compared to residents in newly built neighbourhoods. Local residents do not need to pay for a real-estate management company to undertake general neighbourhood maintenance. Second, by mobilizing local resources, such as building hot-brick beds1 and collecting firewood, residents can save money on living costs. For instance, respondents living in Neighbourhood I and II reported that they really enjoy the open market near their neighbourhoods because they can save money by buying good-quality goods at a low price.

Local residents are also economically dependent on job opportunities in, or close by, these neighbourhoods. These neighbourhoods are often in relatively desirable locations (often close to the public transportation) making these parcels of land potentially expensive after redevelopment. Thus, some respondents consider remaining in occupancy as a positive strategy that will result into more compensation from the redevelopment agencies. However, the disparity between their expectation of the increased future land value and the current compensation criteria makes most residents dissatisfied with the redevelopment and unwilling to move (He & Asami, Citation2014). For instance, some respondents from urban and suburban danwei communities reported that the housing prices in the adjacent newly built neighbourhoods are higher than the financial compensation offered to them by local governments. This means that they cannot afford the dwellings from surrounding neighbourhoods with merely the monetary compensation from local governments, because they are not fairly compensated based on the market price.

We found that many respondents are generally in a position to maintain their current living conditions, but are not able to improve them, or to achieve upward social mobility, due to limited resources, including basic features such as education or social networks including ‘outsiders’ that may be a link to employment opportunities. Thus, those who stay in these declining neighbourhoods are to some extent economically trapped there. This may explain why some respondents said that they had been looking forward to redevelopment as they would like to move into newly built neighbourhoods. They want to escape the stigma of the declining neighbourhood. However, they are also concerned about their economic situation, because after relocation it seems almost impossible for them to mobilize local resources again to gain income and reduce their living costs:

I prefer the current undesirable living conditions, and at least I still have my income as a safeguard … After this [demolition and relocation] my conditions will be better… but I will be nothing …I will have no money in my pocket anymore… (Jun, 40s, male, Neighbourhood VI)

4.3. The ambivalence in the physical dimension of place attachment

Respondents have developed their own patterns of using neighbourhood and housing space, reflecting activity patterns established over a long period of residence. Many respondents reported that their neighbourhoods provide good access to public transport, schools, hospitals, and open markets. Most residents live on low incomes and cannot afford taxis or a private car, making the proximity to these facilities highly important, especially for the aged people.

The majority of our respondents from both urban and suburban areas are satisfied with the physical aspects of their current dwellings. The residential buildings are from one to five stories, which enables residents to get out of their private rooms easily for daily activities such as cooking or exercise. This is especially important for the aged or the disabled since their mobility can be greatly affected by physical barriers. They are worried about moving into the high-rise buildings because they would be less motivated to go outside. Unlike high-rise buildings, these low-storey buildings are more open and their neighbourhoods provide more public space than apartments in the high-rise buildings, which makes it easier for residents to meet and interact with their neighbours. This was important for most respondents as it allowed them to maintain their social network. Ai (30s, female, Neighbourhood VI) gave her opinion on moving to a high-rise building after demolition, compared with her current courtyard:

Residents living in the high-rise building apartment are trapped in it … Now you see I live in this courtyard, and I feel very comfortable to go outside and inside … and it is very convenient. If I live in the high-rise building, it will take time to go up into the apartment and go down to the ground …

Residents in these traditional neighbourhoods have the flexibility to change some of the characteristics and lay-out of their dwelling space. This is because these neighbourhoods have more open space and less rigid construction management than the newly built neighbourhoods. As we saw above, for example, residents can employ empty spaces in their yard to construct more rooms to house other family members, store furniture or rent to others. Also, some of the respondents have their own gardens, which are scarce or non-existent in the high-rise buildings. More importantly, these residents have more autonomy than those who are living in the recently built commodity dwellings in relation to construction within their dwellings. For example, they can build their own heating systems, such as hot-brick beds, to warm the rooms. However, this will not be possible when they move into the high-rise buildings. In addition, some respondents considered that the actual amount of living space they will have will shrink if they move into apartments in high-rise buildings after relocation. Respondents recounted the many advantages of their current dwellings and how they better meet their lifestyle, both practically and emotionally. As Jun (40s, male, Neighbourhood VI) indicated:

Here [in my courtyard] I can grow vegetables and raise chickens or a dog. I like animals. My children like animals … I don’t think there will be enough space in the high-rise apartment [even] for my furniture ….

Nevertheless, residents feel ambivalent about the overall physical state of their neighbourhood. Many respondents reported that they were not satisfied with the deterioration of the sanitation conditions. The decay in the physical conditions, such as the lack of toilets and sewage system in their dwellings, as well as the poor sanitation conditions in their neighbourhoods, have motivated their moving intention. Some respondents would prefer that the living conditions of their existing dwellings are improved, while others would prefer that the neighbourhood conditions are improved while their dwellings remain unchanged. A third category would prefer to leave both their current neighbourhood and dwellings. Ai (30s, female) recounted her ambivalence about moving:

Now these residents have all occupied the streets with constructed dwellings, so there is no room for sewage at all on the street. It is very dirty here … I never wear my good shoes and walk here … I have an ambivalent feeling. I want to move out and also don’t want to (laugh, observed hesitation). I want to move out into the apartments in the high-rise building just because it is very neat and clean.

As mentioned above, respondents claim that the lack of investment by danwei and local governments and the perceived anti-social behaviour of migrants (see Section 4.1) have contributed to the physical deterioration of the neighbourhoods. However, Ai’s statement implies that local residents are also abusing their own neighbourhood environment. In addition, many homeowners have stopped investing in their dwellings to maintain good dwelling conditions due to the extent of neighbourhood degradation and the strong likelihood of redevelopment. In fact, many local residents have established many illegal constructions merely to enlarge the floor area of their dwellings, because (the amount of) compensation is partly dependent upon the size of the current dwelling. Some of these illegal constructions have almost no residential function and they only serve to accelerate the degradation of the neighbourhood and disturb the residents’ sense of place.

5. Perceptions towards the impending demolition and relocation

This section further unfolds how residents perceive the impending demolition (or situation after demolition) which was about to happen soon after the interviews were conducted. Most respondents from urban and suburban neighbourhoods have reported that they feel that the redevelopment is necessary. Some of them discussed their neighbourhoods in terms of ‘you cannot find another place as worse as this in Shenyang’. These respondents intend to move into newly built neighbourhoods if the opportunity arises. In fact, some of them have been anticipating the redevelopment for a long time since they expect to ‘live a happy life [after moving into relocation neighbourhoods!]’. Some of them even went to the office of the local government to make appeals for the redevelopment of their neighbourhood.

Many factors contribute to their willingness to accept the redevelopment and the associated forced relocation. The aforementioned perceived neighbourhood decline and deprived socio-economic status have negatively affected their quality of their life and self-esteem. As part of wider societal changes, the changing meaning of ‘home’ under market transitions in China also raises their aspiration for state-led neighbourhood redevelopment. The meaning of home is not limited to the dwelling, but it has also increasingly becoming an asset of growing financial importance, reflecting the resources and social status of an individual or a household. For instance, in current urban China, a dwelling is required for a marriage in most cases, which was also reported by several interviewed residents. Also, based on the fact that it has become increasingly difficult for these stayers to afford dwellings under current housing market, SRPs with large government subsidies can be a chance for these residents to improve their living conditions.

Residents living in these deprived neighbourhoods cannot afford better housing. Now [with the compensation] you can buy a dwelling slightly better than the current one. That is fine. We should be happy with this improvement although it is very tiny (Mei, female, 60s, Neighbourhood V).

However, when they are informed that their neighbourhoods are going to be redeveloped, many respondents reveal obvious ambivalent feelings, as mentioned in the previous subsections. Because the danwei neighbourhoods provide them with housing, a sense of place, and various resources with which they can relieve their life constraints, forced relocation can be very disruptive. In the post-relocation situation, it is highly unlikely that they can mobilise the same resources as in their danwei communities.

The perceived lack of autonomy in relation to the impending forced relocation process also bothers many respondents. They feel insecure about the forced relocation process. They have witnessed many examples in adjacent neighbourhoods or within Shenyang about how local governments or developers fail to realize their promises on rehousing the affected residents on time. Residents can now reveal their opinions on whether they agree with the redevelopment or not and to choose the real estate assessment company which sets the compensation criteria by assessing the value of residents’ dwellings. However, the influence of residents on the redevelopment process is limited. As soon as the local governments start the redevelopment process, it is impossible for the residents to stop it. Therefore, they feel uncertain about whether their living conditions will improve or not, as the current relocation neighbourhoods provided by local governments are distant from and lack many public facilities. Some residents reported that it would still difficult for them to afford bigger dwellings to accommodate their family members after the redevelopment. These respondents expect the current redevelopment to lift themselves out of their multi-deprived situation, which is out of the scope of the current SRPs focusing merely on improving residents’ living conditions. Therefore, some stayers realize that there probably will be limited improvements in their life after redevelopment:

We cannot afford the new buildings and we have to buy another one just like this …. The redevelopment is like sun shining into dark corners, but we are so dark and cold …. The redevelopment cannot improve our situation fundamentally…(Mei, 60s, female, Neighbourhood V)

Meanwhile, most of them are concerned about how they will adapt to the physical environment after forced relocation. Ai (30s, female) regarded moving to a high-rise building after relocation as becoming ‘trapped in it’. Respondents from either urban or suburban danwei communities reported that the location of their current neighbourhood has obvious advantages over that of the relocation neighbourhoods provided by local governments (see also Section 4.3). They reported that the proposed relocation neighbourhood provided by local governments to rehouse them is far from the city centre and that it currently lacks many public and commercial facilities, increasing their reluctance to relocate. Moreover, they were concerned about a potential dramatic reduction in neighbourhood contacts once they moved to a high-rise building. Respondents regard the level of social engagement in high-rise relocation neighbourhoods as relatively superficial and generally showing indifference. This finding is in line with previous research, which found that residents currently living in newly built neighbourhoods in urban China cherish privacy and prefer to maintain anonymity and a distance within their communities (Zhu et al., Citation2012).

6. Discussion

Residents’ lived experiences and their ambivalent feelings regarding place attachment to their soon-to-be demolished neighbourhoods, show the importance of the danwei communities for residents who live in multiple-deprived situations. Danwei communities, on the one hand, represent the symbolic meaning of socialism and collectivism, which make residents feel nostalgic about their past collective experiences. On the other hands, in daily practise, its functional aspects (tangible social, economic and physical resources) seem even more important to deprived residents. Facing sharply rising housing prices and severe neighbourhood decline, residents need to cope with a dilemma concerning the relative importance of their dependence and attachment to their danwei community and their desire to relocate to achieve better living conditions. This is playing out in a changing context, in which the joint effects of market forces, institutional arrangements and individual situations have contributed to the decline of their danwei communities, the emergence of deprived social groups, and their struggles for decent housing. We will now discuss the influence of these developments in more detail.

A series of SOE reforms has led many danwei to transfer their obligations regarding neighbourhood management to local governments such as local housing bureaus. However, these departments invest little in these neighbourhoods and the residents themselves also lack the motivation for investing in their declining neighbourhoods because they are financially incapable and expect neighbourhood redevelopment in the near future, which would surely destroy their investment. Return on investment is not only important for the residents themselves. Redevelopment of declining neighbourhoods in China has been selective as it is mostly driven by market mechanisms (Liu & Wu, Citation2006). While declining neighbourhoods with high profit potentials (e.g. good location, large-scale and relatively simple homeownership2) have become the priority for redevelopment, those neighbourhoods with high redevelopment costs and less economic profits (e.g. complicated homeownership structures, relatively small scale or poor location) have remained underdeveloped by both the governments and the market (Liu & Wu, Citation2006).

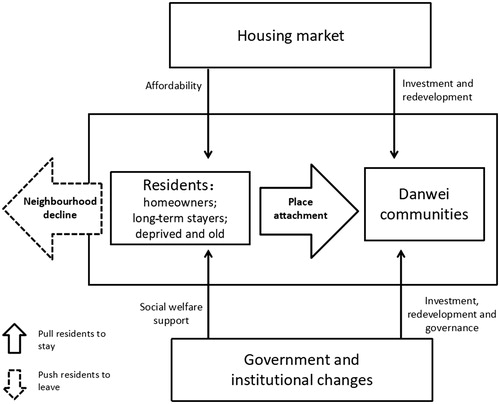

Parallel to the increasing importance of market transition, the unemployed and laid-off residents from danwei communities have developed into one of the most deprived social groups in urban China (He et al., Citation2008, Citation2010; Liu & Wu, Citation2006). Wu (Citation2004) has indicated these laid-off workers may ‘slip into poverty, becoming segregated from mainstream society in terms of their consumption and life styles’ (p. 414). He et al. (Citation2010) further explained that social welfare entitlement and market remuneration are the two dominant factors that lead to these residents’ being trapped in deprivation. The pension or Minimum Living Standard Scheme (MLSS) subsidies from danwei or local governments can only maintain these residents’ basic living. Sudden family changes or events such as enrolling at universities, serious illness or buying dwellings, can lead these households into severe poverty. Also, the unemployed residents cannot sell their labour capital with a decent price in current labour force market, because of their low education and limited skills; they cannot meet the job requirements under industrial restructuring and upgrading in China (Wu, Citation2004). In addition, they are also not willing to work in the low-end service or labour intensive industries (He et al., Citation2010). Therefore, these residents become socially, physically and economically dependent on and trapped in danwei communities. Specifically, they are in a multi-dilemma relationship with their declining neighbourhoods: (1) poor residence but enough space for accommodating their family members by adapting their dwellings and constructing illegal extensions, (2) low-income but also and low-cost living in these neighbourhoods, (3) and shrinking but strong social networks and a sense of place. Based on Section 4 and 5, provides a summary of residents’ ambivalent opinions and lived experiences, embedded in different dimensions of their place attachment while facing the impending demolition and relocation. The table embodies the ambivalence by distinguishing between factors that, for each dimension of place attachment, may act either as a pull factor (reflected in their unwillingness to leave) or a push factor that motivates respondents to leave. From the people-place interaction point of view, this might be contradicting earlier research which emphasizes the more ‘romantic’ side of people–place interactions (including place attachment) that contribute to relocatees’ willingness to stay in their neighbourhoods when facing neighbourhood redevelopment and demolition (Fried, Citation1963; Manzo et al., Citation2008). In fact, previous research has not fully justified the complex interactions between people and place of different characteristics, since lived experiences of deprived residents in declining neighbourhoods are not purely positive (see e.g. Feijten & Van Ham, Citation2009; Livingston et al., Citation2010; Vale,Citation1997). In fact, when studying the influence of urban redevelopment on relocatees, the impacts of place attachment on their moving behaviour should be monitored by carefully examining their positive and negative lived experiences and the roles of different dimensions of place attachment (Livingston et al., Citation2010; Oakley et al., Citation2008; Vale, Citation1997).

Table 1. Summary of resident’s ambivalent perceptions of place attachment in the context of impending neighbourhood redevelopment.

As shown in , neighbourhood deterioration has negatively affected the capacity of many of our respondents to live a decent life and motivated them to leave. However, the rising housing prices cut off alternative housing. This dilemma is closely related to the fact that housing access in current urban China is largely dependent on a household’s income and status and whether people qualify for subsidized housing provided by the state or work units (Chen et al., Citation2014; Lee, Citation2000; Wang et al., Citation2012). Therefore, these old and deprived homeowners in danwei communities are, to a large extent, excluded from the current housing provision system in China. As a result, state-led neighbourhood redevelopment projects, such as the SRPs, which focus on improving the living conditions of deprived residents by governmental subsidies, appear to offer the only way out of their current housing situation. However, the amount of relocation compensation these residents can get from governments strongly determine the utility of this escape (see Li et al., Citation2018 for a detailed discussion of compensation in the context of urban redevelopment).

In the US and Western Europe, renters can get compensation from local governments (Goetz, Citation2016; Kleinhans & Kearns, Citation2013), which is quite different from the experiences of their counterparts in China. In China, renters in declining neighbourhoods are mostly migrants seeking for cheap apartments. They are usually excluded during the redevelopment process. They can neither get compensation from the governments nor developers, because homeownership determines residents’ accessibility to different social resources such as compensation during urban redevelopment. Also, unlike the case in the UK which displays that migrants are more attached to their neighbourhoods compared with the natives (Egan et al., Citation2015), Wu (Citation2012) shows that migrants in China have a slightly lower level of neighbourhood attachment than local residents. Nevertheless, Wu (Citation2012) found that migrants have a stronger willingness to remain in these neighbourhoods than local residents. This might be because compared with their former places of residence in rural areas, migrants can economically and socially benefit from the job opportunities, low-living cost and the social networks in the danwei communities, which makes them more tolerant of the deteriorated living conditions compared to the original long stay homeowners (He et al., Citation2010; Wu, Citation2012).

Overall, access to decent housing for deprived social groups in declining neighbourhoods, including deprived homeowners, renters and migrants, is challenged under market transitions in China. These groups can neither afford commodity dwellings nor obtain access to subsidized housing, which shows the dysfunctioning of the marketization of the Chinese housing market (Chen et al., Citation2014; Lee, Citation2000; Meng, Citation2012). shows some of the relationships between the housing market, government and institutional changes, and the danwei communities and their residents.

7. Conclusions

This article has analysed the place attachment of old and deprived homeowners in declining Chinese danwei communities which face demolition in the context of state-led urban redevelopment in Shenyang. Specifically, the article reveals how residents’ perceptions reflect the pre-relocation impacts on their place attachment, based on a combination of expectations regarding the near future relocation situation with their lived experiences in the current situation. We found that these residents have become increasingly ambivalent regarding their place attachment in the face of neighbourhood redevelopment and impending forced relocation. While they report a sense of satisfaction with and dependence on their neighbourhoods, they simultaneously report dissatisfaction and an inclination to move due to the decline in the quality of life in their neighbourhood.

This article contributes to the literature by demonstrating that studying the pre-relocation perceptions of residents and their place attachment amplifies our understanding of the (somewhat paradoxical) post-relocation perspectives of old and deprived residents. It shows the utility of taking stock of residents’ ambivalent perceptions of place attachment, which is strongly affected by the impending urban redevelopment of the danwei communities. In essence, the governments’ promise of a better future, driven by new housing construction in the context of SRPs, might be heavily compromised in advance. Relocation will very likely end the support structures and coping strategies based on long-standing social networks and place attachment, but also cut off good access to public transport, schools, hospitals, markets and job opportunities close to residents’ current neighbourhoods. Last but not least, relocation will very likely saddle these deprived residents with much higher housing costs, because they can barely afford the current housing price which is based on the market-rate rents with the financial compensation they get from the local governments based on their small dwelling size.

The impending demolition forces residents to face a dilemma concerning the relative importance of various dimensions of their attachment to the neighbourhood and the desire to relocate to achieve better living conditions. This article also contributes to the literature on relocation and urban redevelopment by showing how the affliction (i.e. a sense of loss and grief), which may manifest itself during or at the post-relocation stage of urban redevelopment (Fried, Citation1963), may already emerge strongly at the pre-relocation stage in the case of poor Chinese homeowners in danwei communities. The coping strategies of relocatees at the pre-demolition stage play a significant role, influencing their experiences at the following-up stages of forced relocation and urban redevelopment. Urban redevelopment and forced relocation often last for years, during which period various incidents happen to relocatees in parallel with the changing macro- (social, economic and institutional) and micro-context. By capturing the sequence of the events that occur to relocatees during urban redevelopment, it helps to reduce the distraction caused by the accumulation of the dynamics of relocatees’ experience as the urban redevelopment proceeds over time. Therefore, it is worthwhile to study relocatees’ experiences at the pre-demolition stage and to acknowledge the significance of the temporal feature of urban redevelopment and forced relocation. Our findings for this particular stage and group of residents, therefore, fills a clear gap in the literature that is dominated by experiences of public or social housing tenants in the United States and Europe.

Exploring the ambivalence in their neighbourhood experience helps us understand how these homeowners have coped over time with changing conditions in their neighbourhood which are currently amplified by their almost certain relocation if redevelopment actually starts in their neighbourhood. These (neighbourhood) changes to some extent disrupt their place attachment. Due to serious physical decline and high population turnover, deprived homeowners living in these neighbourhoods have already experienced the sense of discontinuity even before the start of the redevelopment project. On the other hand, their place attachment in some cases is even enhanced while they are suffering from negative neighbourhood changes. This is because these changes force and stimulate these residents to transfer the challenges caused by them into resources from which residents can benefit. In light of this, place attachment can be regarded as the outcome of a combination of the living strategies of residents over time under changing socioeconomic and institutional contexts. These old and relatively poor residents are attached to danwei communities emotionally based on the long term of residence, family history and the collective memories in the socialist era. Also, their relatively poor economic situation makes these residents strongly dependent on the functional aspects of danwei communities, which seems to be more significant as it is related to their living strategies.

To summarize, it is vital to focus on residents’ lived experiences and place attachment at the pre-relocation phase, because it can help us better understand the coping strategies of residents facing urban redevelopment. Gaining an understanding of their perspectives while they are living through this phase may provide better insights than asking residents in the post-relocation phase, i.e. making a retrospective assessment of their pre-demolition life (Goetz, Citation2013). During the pre-relocation phase, they need to make compensation choices based on their current household, dwelling and neighbourhood situation. They also need to evaluate the merits and demerits of staying in their declining neighbourhood and the potential outcomes of redevelopment. It is vital that policymakers and local governments take these factors associated with residents’ lived experiences and living strategies into consideration if they wish to improve the living conditions of those who are deprived.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to the anonymous reviewers and the editor for their valuable suggestions and comments on the previous version of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Xin Li

Xin Li is a Human Geographer and she obtained her Doctoral Degree at the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment, Delft University of Technology. Her PhD research is about urban redevelopment and its impacts on the residents in China. Her expertise includes urban regeneration, governance of land development, residential mobility, neighbourhood changes and housing research.

Reinout Kleinhans

Reinout Kleinhans is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment, Delft University of Technology. His research interests includes urban regeneration, self-organisation, social capital, community entrepreneurship, online-offline citizen engagement, social media, collective efficacy, and participatory planning.

Maarten van Ham

Maarten van Ham is the Professor of Urban Studies at the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment, Delft University of Technology and professor of Geography at the University of St Andrews. His expertise includes urban poverty and inequality, neighbourhood effects, neighbourhoods changes and residential mobility. Currently he is leading a 2 million Euro personal EU-ERC grant to investigate Socio-spatial inequality, deprived neighbourhoods, and neighbourhood effects (DEPRIVEDHOODS).

Notes

1 The hot-brick bed is a traditional type of bed found in northern China, designed to provide a warm bed when it is cold. They are made from bricks or clay and can be connected to either or both the stove and the central heating system in the dwelling.

2 The homeownership composition in a neighbourhood affects local governments’ willingness on neighbourhood redevelopment. If the homeownership is complicated, it means that local governments need to spend more efforts on mediating the interests between different households and family members, which not only involves a lot of conflicts but also might increase the cost and time for the development.

References

- Altman, I., & Low, S. M. (1992) Place Attachment (New York: Plenum).

- Anguelovski, I. (2013) From environmental trauma to safe Haven: Place attachment and place remaking in three marginalized neighborhoods of Barcelona, Boston, and Havana, City & Community, 12(3), pp. 211–237.

- Bailey, N., Kearns, A. & Livingston, M. (2012) Place attachment in deprived neighbourhoods: The impacts of population turnover and social mix, Housing Studies, 27(2), pp. 208–231.

- Bjorklund, M. (1986) The Danwei: Socio-spatial characteristics of work units in China's urban society, Economic Geography, 62(1), pp. 19–29.

- Bray, D. (2014) Social Space and Governance in Urban China: The Danwei System (Nanjing: Southeast University).

- Brown, B. & Perkins, D. D. (1992) Disruptions in place attachment, in: I. Altman & S. M. Low (Eds) Place Attachment, pp. 279–304 (New York: Plenum).

- Brown, B., Perkins, D. D. & Brown, G. (2003) Place attachment in a revitalizing neighborhood: Individual and block levels of analysis, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 23(3): pp. 259–271.

- Chen, J., Yang, Z. and Wang, YP. (2014) The new Chinese model of public housing: A step forward or backward? Housing Studies, 29(4), pp. 534–550.

- Corcoran, M. (2002) Place attachment and community sentiment in marginalised neighbourhoods, Canadian Journal of Urban Research, 11(2), pp. 201–221.

- Egan, M., Lawson, L., Kearns, A., Conway, E., & Neary, J. (2015) Neighbourhood demolition, relocation and health. A qualitative longitudinal study of housing-led urban regeneration in Glasgow, UK, Health & Place, 33, pp. 101–108.

- Feijten, P. & van Ham, M. (2009) Neighbourhood change… Reason to leave? Urban Studies, 46(10), pp. 2103–2122.

- Fullilove, M. (1996) Psychiatric implications of displacement: Contributions from the psychology, The American Journal of Psychiatry, 153(12), pp. 1516–1523.

- Fried, M. & Gleicher, P. (1961) Some sources of residential satisfaction in an urban slum, Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 27(4), pp. 305–315.

- Fried, M. (1963) Grieving for a lost home, in: L. J. Duhl (Ed) The Urban Condition, pp. 151–171 (New York: Basic Books).

- Fried, M. (2000) Continuities and discontinuities of place, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 20(3), pp. 193–205.

- Gilroy, R. (2012) Physical threats to older people's social worlds: Findings from a pilot study in Wuhan, China, Environment and Planning A, 44, pp. 458–476.

- Giuliani, M. V. & Feldman, R. (1993) Place attachment in a developmental and cultural context, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 13, pp. 267–274.

- Goetz, G. (2013) Too good to be true? The variable and contingent benefits of displacement and relocation among low-income public housing residents, Housing Studies, 28(2), pp. 235–252.

- Goetz, E. G. (2016) Resistance to social housing transformation, Cities, 57, pp. 1–5.

- He, S.J., Webster, C., Wu, F. L., & Liu, Y. T. (2008) Profiling urban poverty in a Chinese City, the case of Nanjing, Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy, 1(3), pp. 193–214.

- He, S., Wu, F., Webster, C., & Liu, Y. (2010) Poverty concentration and determinants in China's urban low‐income neighbourhoods and social groups, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 34(2), pp. 328–349.

- He, Z. Y. & Asami, Y. (2014) How do landowners price their lands during land expropriation and the motives behind it: An explanation from a WTA/WTP experiment in central Beijing, Urban Studies, 51(2), 412–427.

- Hidalgo, M. C. & Hernández, B. (2001) Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21(3), pp. 273–281.

- Hin, L. L. & Xin, L. (2011) Redevelopment of urban villages in Shenzhen, China – An analysis of power relations and urban coalitions, Habitat International, 35(3), pp. 426–434.

- Jean, S. (2016) Neighbourhood attachment revisited: Middle-class families in the Montreal metropolitan region, Urban Studies, 53(12), pp. 2567–2583.

- Kearns, A. & Mason, P. (2013) Defining and measuring displacement: Is relocation from restructured neighbourhoods always unwelcome and disruptive? Housing Studies, 28(2), pp. 177–204.

- Kleinhans, R. & Kearns, A. (2013) Neighbourhood restructuring and residential relocation: Towards a balanced perspective on relocation processes and outcomes, Housing Studies, 28(2), pp. 163–176.

- Lewicka, M. (2011) Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? Journal of Environmental Psychology, 31(3), pp. 207–230.

- Lee, J. (2000) From welfare housing to home ownership: The Dilemma of China's housing reform, Housing Studies, 15(1), pp. 61–76.

- Li, X., Kleinhans R., & van Ham, M. (2018) Shantytown redevelopment projects: State-led redevelopment of declining neighbourhoods under market transition in Shenyang, China, Cities, 73, pp. 106–116.

- Li, X., van Ham, M., & Kleinhans, R. (forthcoming) Understanding the Experiences of Relocatees during Forced Relocation in Chinese Urban Restructuring, Housing, Theory and Society. doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2018.1510432

- Liu, Y. T. & Wu, F.L. (2006) Urban poverty neighbourhoods: Typology and spatial concentration under China’s market transition, a case study of Nanjing, Geoforum, 37(4), pp. 610–626.

- Livingston, M., Bailey, N. & Kearns, A. (2010) Neighbourhood attachment in deprived areas: Evidence from the north of England, Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 25, pp. 409–427.

- Lu, F. (1989) Danwei: A special form of social organisation. Social Sciences in China, 1, pp. 71–88.

- Luo, Y. (2012) Institutional Arrangements and Individual Action: The Spontaneous Moving Back of Urban Inhabitants of Resettlement and Space Reconstruction of the Original Community, Master Dissertation, East China Normal University, 2012.

- Manzo, L. C., Kleit, R.G. & Couch, D. (2008) "Moving Three Times Is Like Having Your House on Fire Once": The experience of place and impending displacement among public housing residents, Urban Studies, 45(9), pp. 1855–1878.

- Manzo, L. C. (2014) On uncertain ground: Being at home in the context of public housing redevelopment, International Journal of Housing Policy, 14(4), pp. 389–410.

- Meng, X. (2012) The Transformation of Modi Community: The Redevelopment and Community Governance in the Deprived Neighbourhoods in Inner City (Beijing: Renming University Press).

- MOHURD. (2013) Youju Bian Yiju Baixing Tiandashi: Duihua Zhufang ChengXiang Jianshebu Fu Buzhang Qi Ji. Available at http://www.mohurd.gov.cn/bldjgzyhd/201309/t20130909_214987.html.

- Oakley, D., Ruel, E., & Wilson, G. E. (2008) A Choice with No Options: Atlanta Public Housing Residents’ Lived Experiences in the Face of Relocation (Atlanta: Georgia State University).

- Popkin, S.J., Levy, D.K., Harris, L.E., Comey, J., Cunningham M.K., & Buron, L.F. (2004) The HOPE VI Program: What about the residents? Housing Policy Debate, 15(2), pp. 385–414.

- Popkin, S. J. (2010) A glass half empty? New evidence from the HOPE VI Panel Study, Housing Policy Debate, 20(1), pp. 43–63.

- Posthumus, H., Bolt, G. & van Kempen, R. (2013) Victims or victors? The effects of forced relocations on housing satisfaction in Dutch cities, Journal of Urban Affairs, 36(1), pp. 13–32.

- Posthumus, H. & Kleinhans, R. (2014) Choice within limits: How the institutional context of forced relocation affects tenants’ housing searches and choice strategies, Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 29(1), pp. 105–122.

- Ramkissoon, H., Smith, L. D. G. & Weiler, B. (2013) Testing the dimensionality of place attachment and its relationships with place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviours: A structural equation modelling approach, Tourism Management, 36, pp. 552–566.

- Relph, E. (1976) Place and Placelessness (London: Poin).

- Scannell, L. & Gifford, R. (2010) Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(1), pp. 1–10.

- Stokols, D. & Shumaker, S. A. (1981) People in places: A transactional view of settings, in: J. H. Harvey (Ed) Cognition, Social Behavior and the Environment, pp. 441–488 (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates).

- Tester, G., Ruel, E., Anderson, A., Reitzes, D., & Oakley, D. (2011) Sense of place among Atlanta public housing residents, Journal of Urban Health, 88(3), pp. 436–453.

- Tester, G. & Wingfield, A. H. (2013) Moving past picket fences: The meaning of “home” for public housing residents, Sociological Forum, 28(1), pp. 70–84.

- Vale, L. J. (1997) Empathological Places: Residents’ ambivalence towards remaining in public housing, Journal of Planning Education and Research, 16(3), pp. 159–175.

- Wang, D. G. & Chai, Y. W. (2009) The jobs–housing relationship and commuting in Beijing, China: The legacy of Danwei, Journal of Transport Geography, 17(1), pp. 30–38.

- Wang, Y. P., Shao, L., Murie, A., et al. (2012) The maturation of the neo-liberal housing market in Urban China, Housing Studies, 27(3), pp. 343–359.

- Windsong, E. A. (2010) There is no place like home: Complexities in exploring home and place attachment, The Social Science Journal, 47(1), pp. 205–214.

- Wu, F. (2004) Urban poverty and marginalization under market transition: The case of Chinese cities, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 28(2), pp. 401–423.

- Wu, F. L. (2012) Neighborhood attachment, social participation, and willingness to stay in China's low-income communities, Urban Affairs Review, 48(4), pp. 547–570.

- Wu, F. L. & He, S. J. (2005) Changes in traditional urban areas and impacts of urban redevelopment: A case study of three neighbourhoods in Nanjing, China, Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 96(1), pp. 75–95.

- Zhu, Y., Breitung, W. & Li, S.-M. (2012). The changing meaning of neighbourhood attachment in Chinese commodity housing estates: Evidence from Guangzhou, Urban Studies, 49(11), pp. 2439–2457.

Appendix 1. Socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents.