Abstract

This study examines to which extent neighbourhood ties relate to employment status for the less-well educated inhabitants of 71 neighbourhoods in the Dutch city of Rotterdam. Previous research has produced different expectations as to whether having contact with neighbours is either positively or negatively related to being employed and how this relation differs across neighbourhoods. Two waves from the Neighbourhood Profile survey (N = 8507) were used, which included measures of the contact frequency with neighbours and their willingness to help. We find that for the less-well educated neighbourhood ties have a modest negative relation to employment. Moreover, this relation does not vary across neighbourhoods with different socioeconomic statuses, with the exception of part-time working men. Our research implies that neighbourhood ties in mixed neighbourhoods do not positively relate to employment for the less-well educated, thereby questioning policy assumptions about ‘social mix’. Contributions to the field of neighbourhood studies are made by employing measures of the social networks mechanism and taking into account the conditionality of effects across neighbourhoods.

Introduction

Labour markets play a key role in integrating people into society. Yet, participation among the low and middle educated is generally lower than among the high educated due to several factors such as skills demand and technological innovation (Brynjolfsson & McAfee, Citation2014; David et al., Citation2006; Goos & Manning, Citation2007; Goos et al., Citation2014), discrimination (Andriessen et al., Citation2015; Bertrand & Mullainathan, Citation2004), and a lack of social capital (Kanas et al., Citation2011). In the neighbourhood effects literature, theories of ‘social mix’ suggest that mixed neighbourhoods can reduce these differences in employment, because low and middle educated groups – hereafter referred to as less-well educated groups – may profit from the proximity of resourceful neighbours (see Bolt & Van Kempen, Citation2013). Hence, ties with neighbours might provide access to the labour market. However, the role of neighbourhood ties in job attainment is empirically understudied, which is odd to a certain extent because people find jobs primarily through contacts (Granovetter, Citation1995) and for low educated people – and middle educated people to a lesser extent – the neighbourhood is usually an important social setting (Campbell & Lee, Citation1992; Fischer, Citation1982, Van Kempen & Wissink, Citation2014). This study therefore focuses on the relation between neighbourhood ties and employment for less-well educated groups and in addition, this study investigates to which extent this relation varies across neighbourhoods with different socioeconomic statuses (SES).

A limited number of studies with diverging approaches have examined how both neighbourhood ties and neighbourhood SES relate to labour market outcomes (Damm, Citation2014; Elliot, Citation1999; Kasinitz & Rosenberg, Citation1996; Kleit, Citation2001; Miltenburg, Citation2015; Pinkster, Citation2007, Citation2009, Citation2014; Reingold et al., Citation2001). Most of these studies were either qualitative in nature (e.g. Kasinitz & Rosenberg, Citation1996) or focused on earnings (e.g. Elliot, Citation1999) and not employment as an outcome. Little is therefore known about the relation between neighbourhood ties and labour market participation (cf. Aguilera, Citation2002). These studies have produced contradicting hypotheses about the strength and direction of these relations. On the one hand, it is believed that social contacts in low SES neighbourhoods are less effective for employment chances than the more bridging contacts (cf. Putnam, Citation2000) in mixed or high SES neighbourhoods because low SES neighbourhoods lack the necessary job-related resources. In low SES neighbourhoods, neighbourhood ties are presumed to constrain employment as fellow residents hold weak labour market positions. However, more qualitative research shows that in low SES neighbourhoods residents can help each other obtain a job through referrals or giving advice (Pinkster, Citation2007, Citation2014; Tersteeg et al., Citation2015), indicating that having contacts in low SES neighbourhoods can actually be beneficial for labour market participation. Such ties seem especially helpful in obtaining flexible jobs at the lower end of the labour market. Based on a large dataset that includes 71 urban neighbourhoods, this study tests these different hypotheses in a systematic way. We investigate both the size and direction of the relationship between neighbourhood ties and employment and subsequently, we test whether this relation differs between lower and higher SES neighbourhoods. Multilevel models estimate to which extent neighbourhood ties relate to our dependent variable of labour market participation, which includes whether people are unemployed, work part-time, or full-time.

This study builds on previous research in two ways. First, we include multiple measures of neighbourhood social interactions in our empirical models. Neighbourhood effects studies examine relations between neighbourhood characteristics and individual outcomes, but rarely test the underlying mechanisms (see Galster, Citation2012) that are believed to transmit these effects (Sharkey & Faber, Citation2014). For example, while many studies estimate to which extent neighbourhood SES affects employment without including social-interactive measures, they assume social capital to be a transmitting mechanism of this neighbourhood effect (cf. Miltenburg, Citation2015). In this study we refrain from interpreting any neighbourhood effects, that is, the effect of neighbourhood SES on employment. Instead we investigate the association between neighbourhood ties and employment, and how this relation differs according to neighbourhood SES. In our models we include both measures of the frequency of contact with neighbours and an attitudinal component that signifies whether neighbours are willing to help each other.

Second, we take into account that associations are potentially conditional, meaning they might differ between groups and across neighbourhoods. Although this point is often emphasized in the literature, researchers fail to systematically take this into account (Miltenburg, Citation2015; Sharkey & Faber, Citation2014; Small & Feldman, Citation2012). We focus exclusively on less-well educated people because prior research has shown that, in terms of social networks and behaviour patterns, they tend to orientate more towards the neighbourhood than the high educated (Campbell & Lee, Citation1992; Fischer, Citation1982; Van Kempen & Wissink, Citation2014). The less-well educated are therefore more likely to employ local ties when searching for a job (Van Eijk, Citation2010a). In addition, we split our analyses by gender to examine how the specified relations differ between men and women.

Since this study uses cross-sectional data, based on two waves (2013 and 2015) from the Neighbourhood Profile (Municipality of Rotterdam, Citation2016), it is – like other quantitative studies in the field of neighbourhood effects – prone to issues of causality and self-selection (see Galster, Citation2008). The main problem lies in the complexity to distinguish whether a neighbourhood characteristic causes an effect, or whether this effect is a result of peoples’ selective migration into a neighbourhood (Cheshire, Citation2012). This issue is not directly evaded by our focus on mechanisms instead of neighbourhood effects, because self-selection could also influence the formation of neighbourhood ties. We address this issue in a theoretical manner, rather than approaching it from a common-used methodological perspective (see Galster et al., Citation2016). We do so by theoretically discussing how neighbourhood ties and employment affect each other reciprocally, and we are cautious with any causal interpretations of our results.

Finally, our research focuses on Rotterdam, the second most populous city of the Netherlands (over 600,000 inhabitants), which has the country’s highest unemployment level (Dirven et al., Citation2015). In the years following the 2000s, the city has adopted many policies, such as the Rotterdam law, which aim to deconcentrate poverty and create mixed communities (Snel & Engbersen, Citation2009; Van der Laan Bouma-Doff, Citation2007). From a policy perspective, ideas about social mixing and its presumed benefits are unmistakably present in Rotterdam (Bolt & Van Kempen, Citation2013; Doucet et al., Citation2011). We aim to address three questions in this study:

To which extent do neighbourhood ties and employment associate for the low and middle educated?

Do these associations vary across low, mixed, and high SES neighbourhoods?

How do outcomes differ when we distinguish between men and women?

Theory

Neighbourhood effects studies

Following the influential work by Wilson (Citation1987, Citation1996) about social isolation in inner city neighbourhoods, many scholars have theorized and empirically investigated why living and growing up in poor neighbourhoods might additionally disadvantage people in achieving social mobility compared to people living in more wealthy neighbourhoods. From this body of research the idea of neighbourhood effects emerged: does living in a certain neighbourhood affect your chances for employment and other outcomes (Van Ham et al., Citation2012)? Studies in the US context found strong correlations between neighbourhood SES and labour market outcomes (e.g. Vartanian, Citation1999), although depending on the research design the results are often debated (De Souza Briggs, Citation1997; Clampet-Lundquist & Massey, Citation2008; Jencks & Mayer, Citation1990). European studies have produced mixed results (Andersson, Citation2004; Musterd & Andersson, Citation2006; Musterd et al., Citation2003; Urban, Citation2009; Van Der Klaauw & Ours, Citation2003; Van Ham & Manley, Citation2010, Citation2015), which has led to further debate about the theoretical and methodological issues concerning neighbourhood effects.

These studies treat the neighbourhood SES effect as a proxy for the multiple ways in which a neighbourhood may influence an individual, while it remains unclear what is exactly conveyed by such an effect (Slater, Citation2013). Many of these studies assume that neighbourhood effects are transmitted through several mechanisms such as social-interactive ones (see Galster, Citation2012) but they lack measures of these mechanisms in their models (De Souza Briggs Citation1997; Sampson, Citation2008; Sharkey & Faber, Citation2014). A way to lift the lid of this ‘black box’ and to better understand neighbourhood effects is to focus on the contacts and interactions between residents in neighbourhoods (Miltenburg, Citation2015, p. 274). Hence, we elaborate on the social networks mechanism, one of the social-interactive mechanisms, which denotes that individuals in a neighbourhood can be influenced by their neighbours through the exchange of information, resources, and support (Galster, Citation2012, p. 25).

Contacts in low SES neighbourhoods

Since neighbourhood ties are heterogeneous by nature, the social networks mechanism might operate diversely in low SES neighbourhoods. The general view of low SES neighbourhoods is that neighbours can help each other ‘get by’ but not ‘get ahead’ since they lack necessary resources (De Souza Briggs, Citation1998). Moreover, neighbours can inhibit each other from making meaningful contacts with more resourceful persons when they form closed, restrictive networks (cf. Portes, Citation1998). In addition, the intimacy of neighbourhood ties strongly varies, ranging from superficial, nodding relationships (Blokland & Nast, Citation2014) to supportive contacts (in line with a Dutch saying: ‘A good neighbour is worth more than a distant friend’). The ways in which interaction with neighbours can relate to job attainment are thus versatile. Therefore, in order to theorize why having contacts with neighbours can either be beneficial or detrimental for labour market participation, we distinguish between a positive and a negative hypothesis about the role of neighbourhood ties.

The positive hypothesis holds that having contacts with neighbours is positively related to employment. In the Dutch context, having contacts with neighbours means having contacts with people who live close by whom are not family or considered to be close friends. They are therefore seen as weak ties (Granovetter, Citation1973), which potentially serve as bridges to job information and opportunities. Although much research indicates that neighbours are generally not a prime source of job-related info and contacts (e.g. Mollenhorst, Citation2015), Van Eijk (Citation2010a, p. 81) shows that poor urban residents frequently mobilize neighbours when searching for a job. This latter observation corresponds with evidence that the personal networks of the less-well educated are more local. A larger part of their networks consists of local ties compared to the high educated, whom often have relatively more ties outside the neighbourhood (Fischer, Citation1982; Van Eijk, Citation2010b).

Multiple qualitative neighbourhood studies further illustrate why being embedded in neighbourhood networks might form a direct or indirect link to the labour market (Kloosterman & Van der Leun, Citation1999; Pinkster, Citation2007, Citation2009, Citation2014; Tersteeg et al., Citation2015). These studies provide evidence that, contrarily to common perceptions, the neighbourhood is a social context in which people search for jobs and exchange job-related information. Social life in many urban neighbourhoods is constituted by multiple communities, which are separated along socioeconomic, ethnic, religious, or political lines (cf. Butler & Robson, Citation2001). Pinkster (Citation2007, Citation2014) shows that such communities consist of close-knit relations that provide emotional and instrumental support. These communities possess informal job networks that contain available job positions and job-related resources such as information, contacts, and advice. Thus, being part of such a neighbourhood-based network could increase chances for employment. Moreover, Tersteeg et al. (Citation2015) indicate that job-related exchanges do not only take place within communities with particular ethnic and socioeconomic characteristics, but also between people from different backgrounds. Building on social network theory (Granovetter, Citation1995; Lin, Citation1999), this implies that job-related resources transfer across different neighbourhood networks, increasing employment chances for those being part of a network. Even if neighbourhood ties are moderately resourceful, having these contacts then trumps having no contacts at all.

An important note here is that although studies have shown that such theories of social networks are instrumental in explaining how labour markets operate, they often exclude the unemployed and underemployed (Aguilera, Citation2002, p. 871). In other words, most studies using social network theory focus on how people obtain a good job (cf. Granovetter, Citation1995), that is, with high earnings or status, and not on how people obtain employment. Yet, when we conceive neighbourhood ties as a form of weak ties that can provide access to resources such as information or references, they can be seen as ties that provide leverage for job attainment. Such ties might help the unemployed in finding their way back to the job market. The social mechanisms which help people obtain a good job are therefore expected to operate in a similar way for people who are looking to become employed.

In contrast to the positive hypothesis about the effect of neighbourhood ties, the negative hypothesis presumes that neighbourhood ties constrain people instead of foster their labour market participation and therefore have negative influence. Less-well educated people who socialize with poor neighbours can get ‘trapped’ in neighbourhood networks, which block their potential social mobility. Such ‘draining ties’ exist when less-well educated people are asked to provide or reciprocate assistance, money, or time to others (Blokland & Noordhoff, Citation2008; Curley, Citation2008; Nguyen et al., Citation2016). These appeals can place strain on their already scarce resources, which in turn affects their ability to work. Blokland & Noordhoff (Citation2008) refer to this kind of social capital as ‘the weakness of weak ties’.

Another negative link between neighbourhood ties and employment exists when the unemployed are analyzed in terms of the time, money, and work available to them (Engbersen et al., Citation2006). Since they have too little of the latter two resources and too much of the former, the unemployed develop different strategies to cope with this situation. Although not the majority, some unemployed refrain from attaining a job and choose to dedicate their time to socializing in the neighbourhood (Engbersen et al., Citation2006). Thus, this ‘type’ of unemployed can have many neighbourhood ties without having any job prospects. Moreover, if they socialize with other unemployed in the neighbourhood, having these contacts actually hinders their potential labour market participation because this network is poor in terms of job-related resources and restricts them in making connections to more resourceful persons (Field, Citation2008, p. 86–87). This line of reasoning employs a reversed causal order, namely that labour market status determines the extent of engagement in neighbourhood ties (cf. Campbell & Lee, Citation1992). People who spend less time on work can spend more time on socializing with neighbours, as seen from a time-use perspective.1

Contacts in mixed and high SES neighbourhoods

Our contradicting hypotheses about the relation between neighbourhood ties and labour market participation are predominantly based on research in low SES neighbourhoods. For mixed and high SES neighbourhoods, it is assumed that contacts provide better access to the labour market (Wilson, Citation1987). In these neighbourhoods less-well educated groups have more opportunities to connect with resourceful, largely middle-class, people who follow ‘mainstream’ norms of work and family and possess better job networks (Curley, Citation2010; Harding & Blokland, Citation2014, p. 162). Indeed, Volker et al. (Citation2014) indicate that the neighbourhood is one of the most important social settings where the lower and higher educated have overlapping networks. Assuming that these bridging networks exist in mixed and high SES neighbourhoods and that job-related resources such as information and recommendations are being exchanged, it is likely that neighbourhood ties increase employment chances for the less-well educated since these neighbourhoods are more resourceful than low SES neighbourhoods.

Much research has, however, contested this theory about how mixed neighbourhoods operate. Residents with different characteristics in mixed neighbourhoods seldom have overlapping neighbourhood networks (Tersteeg & Pinkster, 2015; Van Beckhoven & Van Kempen, Citation2003; Van Eijk, Citation2010a). When these networks do exist, the ties do not have the appropriate strength for transferring resources (Blokland, Citation2008; Kleit, Citation2001). Such mixed reciprocal networks only tend to develop in particular cases, inter alia depending on urban design and the residents’ length of residence in a community (see Bolt & Van Kempen, Citation2013). In sum, resourceful neighbours in mixed and high SES neighbourhoods could provide better labour market access for their less-well educated neighbours, but this effect is not likely to occur due to a lack of overlapping networks. Our analyses will test whether there is any support for this social mix hypothesis, which thus reads that the association between neighbourhood ties and employment becomes more positive when neighbourhood SES increases.

Data and measurements

In order to investigate the relations between neighbourhood ties, employment, and neighbourhood SES, data from two waves (2013 and 2015) of the Rotterdam Neighbourhood Profile (Municipality of Rotterdam, Citation2016) were merged and combined with administrative data provided by the research department of the Rotterdam municipality (Research and Business Intelligence: RBI). The Rotterdam Neighbourhood Profile is a biannual cross-sectional survey that has been conducted since 2008 and serves as an instrument to monitor the ‘social and physical state’ of Rotterdam.2 A completely new sample is drawn for every wave. The respondents, approximately 15,000 per wave, resided in 71 neighbourhoods, which are defined by Statistics Netherlands as the spatial level between the municipality and lowest spatial neighbourhood level and follow natural demarcation lines and homogenous architecture styles. The net response rates in 2013 and 2015 were 22.5% and 21.5%, respectively. We selected respondents who belonged to the labour market population, that is, who indicated that they were either employed or available for work. A further selection was made based on the achieved educational level; respondents with a high educational level were excluded from the analyses.3 Missing values on variables were excluded through listwise deletion, which formed 9.0% of the target sample. After the data preparations, the final sample contained 8507 respondents.

Individual-level variables

The dependent variable employment consists of three categories, namely people who were unemployed and/or on welfare (0), worked part-time (1), or full-time (2). Respondents had to indicate whether they had a paid job and if so, how many hours they worked a week (on average). In accordance with the definition by Statistics Netherlands, respondents were categorized as ‘full-time’ when they worked more than 35 hours a week and ‘part-time’ when they worked between 12 and 35 hours. Respondents without a job or working less than 12 hours were categorized as ‘unemployed’ if they stated that their current situation was either ‘unemployed/looking for a job’ or ‘receiving social benefits’.4

Socializing with neighbours (contact frequency with neighbours) was operationalized by two items: how often respondents had personal, telephonic, or written contact with direct neighbours (a) or other neighbours in the area (b). The response categories varied from never (0) to almost daily (5). A Spearman-Brown test (see Eisinga et al., Citation2013) indicated that the reliability of both items is sufficient (.77), thus a scale was constructed with their mean score. A limitation of this measure is that it does not account for the type of neighbourhood contacts (e.g. resource-rich or resource-poor) respondents have. Nor does it indicate what is being exchanged: whether neighbours discuss their employment opportunities or merely make casual conversation. However, we can assume that more information and resources are exchanged when neighbours interact more frequently. We elaborate on this measurement issue in the discussion.

Perceptions of neighbours’ preparedness to help (willingness to help) were measured by asking respondents to which extent they agreed with the statement ‘people in this neighbourhood help each other when necessary’. The response categories were coded to (completely) disagree (0), neutral (1), and (completely) agree (2), and included as dummy variables in the analyses because of the high number of missing values (13%).5 Again, this measurement is not directly related to employment matters and therefore requires careful interpretation.

Education was measured as the highest level of achieved education. Levels of education ranged from ‘none/elementary education’ (0) to ‘preparatory scholarly education’ (5). Several control variables were included in our models to account for potential omitted influences and neighbourhood self-selection to a certain degree. The personal characteristics gender, age, ethnicity, household status, health disabilities, language fluency (based on three items), tenure situation, length of residence, and wave year were added to the models.6 In addition, other social network features involving contact frequency with family and contact frequency with friends and close acquaintances were controlled for. Including these network measures reduces the probability that we find a spurious relation between neighbourhood ties and employment, for instance in the case that employment is mainly related to friendship ties (Aguilera, Citation2002). Descriptives of these variables can be found in .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Neighbourhood-level variables

One of the central variables of interest, neighbourhood SES, was operationalized by combining different information from RBI on the neighbourhood level, namely the percentage of low incomes (a), the percentage of people on social benefits (‘bijstand’) (b), percentage of unemployed aged 23–64 (c), and the percentage of working people aged 23–64 (d).7 A factor analysis showed that these items constitute one dimension (factor loadings > .83) and a reliability analysis confirms the reliability of this scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .93). Hence, a standardized factor score was calculated to rank the 71 neighbourhoods according to their SES, corresponding to the Neighbourhood Profile year of data collection.

Other factors at the neighbourhood level could relate to a respondent’s labour market position, such as the presence of higher educated residents. Therefore, based on inter alia the System of Social Statistical Datasets (Statistics Netherlands), the percentage of higher educated neighbours was added as control variable on the neighbourhood level.8 Moreover, in our models we also controlled for the influences of ethnic diversity (Herfindahl index9) and residential turnover (percentage of moved households), but these neighbourhood effects were non-significant. They are excluded from the analyses for reasons of parsimony. Information about neighbourhood SES and the percentage of higher educated neighbours is provided in .

Analytical strategy

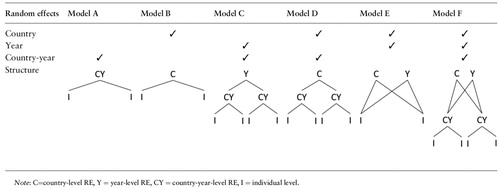

We are interested in what important predictors are for being employed compared to being unemployed. We therefore estimate random intercept logistic models, that is, multilevel regression models (Snijders & Bosker, Citation2012), with the unemployed as the baseline category and part-timers and full-timers as the corresponding other categories to account for the complex nesting structure of our data.10,11 Because our data do not only contain individuals nested within neighbourhoods but also in years, we need a three-level structure that controls for all possible dependencies. Schmidt-Catran & Fairbrother (Citation2015) have demonstrated why an appropriate modelling structure is imperative for obtaining correct regression estimates. We adopt model F proposed by Schmidt-Catran & Fairbrother (Citation2015), which treats neighbourhood-years as cross-classified within neighbourhoods and years, and individuals as strictly nested in neighbourhood-years (see ). Empty models with this nesting structure have better fits than non-hierarchical models or multilevel models with different nesting structures (as in ).12 The empty models show considerable variance at the neighbourhood level for both the odds of working part-time or full-time; the respective intraclass correlations are .077 and .074.13

Figure 1. A typology of random effects structures for multilevel models of comparative longitudinal survey data (adopted from Schmidt-Catran & Fairbrother (Citation2015)).

In our analyses we present three models for both employment states. The first model contains all individual and neighbourhood variables to assess how contact frequency with neighbours and their willingness to help relate to employment, controlled for possible other influences. In the second and third models interaction terms are added, namely the interaction between neighbourhood SES and contact frequency with neighbours (second model) and the interaction between neighbourhood SES and willingness to help (third model). The latter two models enable us to research how the effect of neighbourhood ties varies across low, mixed, and high SES neighbourhoods. Furthermore, we estimate these six models for both men and women to investigate to which extent gender differences exist. For reasons of parsimony we only present the coefficients of interest for the gender models, which are contact frequency with neighbours, willingness to help, neighbourhood SES, and the corresponding interaction terms. Finally, all continuous variables on the individual and neighbourhood levels presented in are mean-centred in the multilevel analyses, which was required for the models to converge.

Results

reports the full multilevel models including all individual and neighbourhood variables. Model 1 shows that the contact frequency with neighbours is negatively related to working part-time: the odds ratio (OR) is .938 and significant (α = .01). The effect is even more negative for full-timers (OR = .881, Model 4). These findings indicate that working more hours is inversely related to having contacts with neighbours. Conversely, for the willingness to help neighbours we find one positive effect: respondents who have a neutral attitude have higher odds to be full-time employed than respondents who indicate that their neighbours are not willing to help (OR = 1.285, Model 4). The effects of our social-interactive measures seem to mainly support our negative hypothesis, namely that neighbourhood ties are negatively associated with employment.

Table 2. Random intercept logistic models with odds ratios for employment status (ref. = unemployed/welfare benefits).

According to the social mix hypothesis, the effects of contact with neighbours and willingness to help are expected to be more positive when neighbourhood SES increases. shows that all interaction terms (Models 2, 3, 5, and 6) are insignificant, meaning that the effects of contact frequency and willingness to help on employment do not significantly vary across neighbourhoods. This observation implies that for the less-well educated it does not matter whether they live in a low, mixed, or high SES neighbourhood with regard to obtaining employment through neighbours, because the association between neighbourhood ties and employment appears to be invariable.14

The models in show a significant impact of several control variables on the odds to be working part-time or full-time compared to the odds of being unemployed. Contact frequency with family is positively related to both working part-time (OR = 1.158, Model 1) and full-time (OR = 1.188, Model 4), indicating that kin – regarded as strong ties – might play an important role for job attainment among less-well educated groups (cf. Blokland & Noordhoff, Citation2008). Other effects are in accordance with earlier research, such as the lower participation odds of the low educated, young and old respondents, the non-Dutch, and respondents with disabilities.

Previous neighbourhood research has demonstrated that effects for certain groups differ between neighbourhoods, whereby gender differences are often found to be profound (e.g. Kling et al., Citation2005). Looking at the distribution of employment, indicates that the largest share of men worked full-time (67%), whereas women mostly worked part-time (48%). In and the full models are split by gender. The analyses for women do not yield very different results compared to ones discussed above; contact frequency with neighbours is negatively associated to working part-time (OR = .942, α = .05, Model 1a) and full-time (OR = .871, Model 4a). The effects of willingness to help are not significant and moreover, both relations do not vary across neighbourhoods since the interaction terms in Models 2a, 3a, 5a, and 6a are insignificant.

Table 3. Random intercept logistic models with selected odds ratios for women’s employment status (ref. = unemployed/welfare benefits).

Table 4. Random intercept logistic models with selected odds ratios for men’s employment status (ref. = unemployed/welfare benefits).

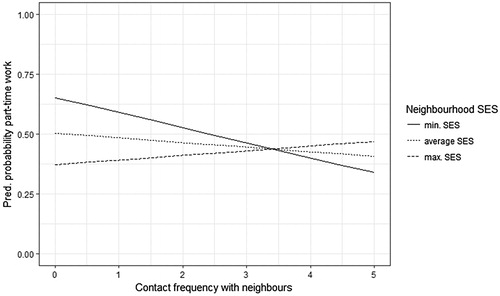

For full-time working men, we find that contact frequency with neighbours has a negative effect (OR = .889, Model 4b) and having a neutral attitude towards helping has a positive effect (OR = 1.413, α = .05). Again, these effects do not vary across neighbourhoods with different SES (see Models 5b and 6b). On the other hand, the results for part-time working men compared to unemployed men show a different picture. In Model 1b none of the relevant effects are significant, but Model 2b demonstrates that the relation between contact frequency with neighbours and part-time employment significantly varies across neighbourhoods (OR = 1.075, α = .1). Hence, the association between contact with neighbours and part-time employment positively increases with neighbourhood SES. We particularly note that for a neighbourhood with average SES – the variables were mean-centred – the effect of contact with neighbours is negative and not significant (OR = .937, Model 2b). To better understand this interaction effect, we depict the effects for the minimum, average, and maximum neighbourhood SES based on predicted probabilities (). shows that the slope is most steep for the minimum neighbourhood SES (negative effect), whereas the slope is slightly positive for the maximum neighbourhood SES. In our interpretation, it is likely that mixed SES neighbourhoods prevent a negative association between contact with neighbours and part-time employment of men, rather than foster a positive association.

Figure 2. Effect of contact frequency with neighbours on part-time employment for men (ref. = unemployed/welfare benefits)., moderated by neighbourhood SES.

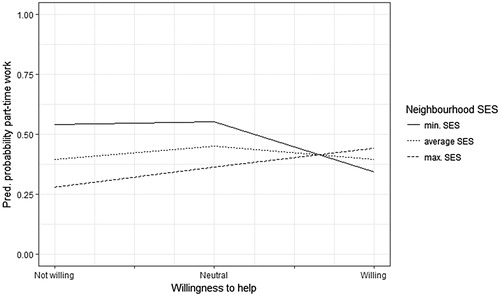

In Model 3b the interaction between neighbourhood SES and willingness to help is positive and significant (OR = 1.390, α = .05), signifying that neighbours’ willingness to help has a stronger positive impact on part-time male employment when neighbourhood SES increases. , which illustrates the interaction effect using predicted probabilities, shows that the effect of willingness to help is positive for neighbourhoods with maximum SES, but turns negative for neighbourhoods with minimum SES. This plot suggests that for low SES neighbourhoods, the willingness of neighbours to help is associated with a reduced chance of part-time employment for men.

Conclusion and discussion

This study of less-well educated groups set out to answer three questions regarding the relations between neighbourhood ties, employment, and neighbourhood SES: to which extent do neighbourhood ties and employment associate for the low and middle educated? Do these associations vary across low, mixed, and high SES neighbourhoods? And how do outcomes differ when we distinguish between men and women? Using two cross-sectional waves (2013 and 2015) from the Neighbourhood Profile survey, covering 71 neighbourhoods in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, multilevel models were estimated that included measures of contact frequency with neighbours and perceptions of neighbours’ willingness to help. By employing these measures, this paper sheds more light on the mechanisms that underlie neighbourhood effects (cf. Miltenburg, Citation2015).

Concerning the first two questions, our main conclusion is that neighbourhood ties are predominantly negatively related to being employed – an association stronger for full-timers than for part-timers – and this relation does not vary across neighbourhoods with a different SES. Based on our theoretical framework, we offer three possible explanations for these findings. First, neighbourhood ties among less-well educated groups operate as a ‘dark side’ of social capital with respect to labour market participation (cf. Portes, Citation1998). These contacts might offer support to ‘get by’ in other domains such as informal care or chores, but for obtaining a job their resources (e.g. references, advice, job information) are too limited to ‘get ahead’ (De Souza Briggs, Citation1998). Moreover, the negative association implies that neighbours may act as ‘draining’ ties, meaning that neighbours’ appeals put strain on people’s resources such as money, time, and energy, which in turn affects their ability to work consistently (Blokland & Noordhoff, Citation2008; Curley, Citation2008; Nguyen et al., Citation2016). We emphasize, however, that our measures did not include any potential negative aspects of neighbourhood ties. Whether neighbourhood ties really have a draining effect needs to be further scrutinized (Blokland & Noordhoff, Citation2008).

Second, from a time-use perspective it follows that people who work less hours can spent more time socializing in the neighbourhood. Having frequent contacts with neighbours might thus be a result of unemployment, but not necessarily one of its causes (Engbersen et al., Citation2006). We thereby note that we mainly found effects for our behavioural measure (contact frequency with neighbours) and not our attitudinal measure (willingness to help). This finding might indicate that neighbours help each other regardless of their labour market statuses, whereas their level of interaction is higher as people work less hours.

Third, in accordance with earlier research it is likely that mixed neighbourhoods do not equal mixed or ‘bridging’ networks and even if these mixed networks do exist, they do not have the appropriate strength for transferring resources that can lead to employment for the less-well educated (Blokland, Citation2008; Kleit, Citation2001). Since our models did not include any measures of how mixed people’s neighbourhood networks were, for instance in terms of bridging or resource-rich ties, we cannot empirically sustain that the invariability of the relationship between neighbourhood ties and employment across neighbourhoods is due to a dearth of mixed networks.

Turning to our third research question, we found one exception to our main conclusion. For part-time working men, when compared to unemployed men, we established a varying relationship between neighbourhood ties and employment across different neighbourhoods. Regarding neighbourhood contacts, this relation is negative in low SES neighbourhoods, more or less neutral in mixed SES neighbourhoods, and it is slightly positive in high SES neighbourhoods. Neighbours’ willingness to help has a positive association with part-time employment in high SES neighbourhoods. These findings imply that neighbours do not form draining ties in mixed neighbourhoods and moreover, that in high SES neighbourhoods neighbours can actually help men obtain part-time employment. A possible explanation is that in high SES neighbourhoods there are resources (information, advice, and references) available which provide access to ‘small’ part-time jobs and these resources are attainable for less-well educated men though informal neighbourhood channels (cf. Pinkster, Citation2009).

As our empirical results provide tentative evidence that the employed have less neighbourhood ties, we can, given our explanations above, ponder about the implications of our main conclusion. People who work more have less time to engage with their neighbours. Their contribution to local networks might therefore be rather low, as is their capability to help other neighbours obtain a job (cf. Van Eijk, Citation2010a). Several studies further indicate that people prefer having ties with similar others in their neighbourhood, that is, based on homophily (see Bolt & Van Kempen, Citation2013). In this respect the exchange of resources between the employed and unemployed is likely to be restricted. Based on these propositions, that is, limited participation in local networks by the employed and the tendency to form homogeneous networks, one could infer that neighbourhood ties have limited relevance for labour market participation.

This latter implication finds some support in our models, which indicate that other factors such as education level and health disabilities are more powerful predictors of employment status. Hence, we should not overemphasize the role of neighbourhood ties in relation to employment.

To conclude, we point out some limitations of our study and general points for discussion. We already mentioned some of the deficits of our neighbourhood ties measures regarding their limited coverage of aspects relevant to respondents’ employment status. For instance, our measures did not include the kind of neighbours with whom respondents had contacts (resource-rich or resource-poor), what kind of information was exchanged between neighbours, nor the quality of ties. Other labour market research has already demonstrated how such tie characteristics relate to a higher job status or earnings (e.g. Granovetter, Citation1995). Yet, less is known about which relational factors relate to obtaining employment (see Aguilera, Citation2002) and which aspects of neighbouring relations might be important. Our study provides some preliminary insights into these issues.

Another limitation is that the cross-sectional design of our study does not enable us to further address issues of causality. Although we found associations between neighbourhood ties and employment, we cannot empirically establish the causes of these associations in this research. We have therefore tried to be cautious with our interpretations. If we, however, assume that our established negative associations between neighbourhood ties and employment are a result of draining ties, then the elemental question would remain: do less-well educated people become unemployed as a result of having draining ties in the neighbourhood, or did they develop resource-poor neighbourhood ties as a result of unemployment (cf. Cheshire, Citation2012)? We believe that one perspective is not antithetical to the other. Unemployment and resource-poor networks can mutually reinforce each other in the persistence of poverty; people move into poor areas and develop ties with neighbours, which in in turn hinder their labour market opportunities. Understanding such processes is at the core of neighbourhood research and requires more in-depth examination of how moving behaviour and the development of neighbourhood ties are interrelated. Such research would, for example, require a combination of (a) a social network analysis of neighbourhood networks, thus mapping residents’ networks within a confined geographical area and (b) a life history analysis of residents, which would uncover both their arrival and embeddedness in the neighbourhood. To be clear, we do not claim that our study provides any empirical evidence of draining ties; our intention here is to discuss the questions that our research raises.

A final remark is that we have tested different hypotheses in this study which were derived from multiple qualitative neighbourhood studies, thus employing ethnographies to generate specific hypotheses (Small & Feldman, Citation2012). Our quantitative results support the view that neighbourhood ties are rather negatively related (e.g. Blokland & Noordhoff, Citation2008) than positively related (e.g. Tersteeg et al., Citation2015) to employment. By integrating insights from qualitative studies into our theoretical framework, we have contributed to obtaining a more coherent interpretation of how neighbourhoods matter (Small & Feldman, Citation2012). Future qualitative studies could further disentangle why such opposing hypotheses exist by investigating how different neighbourhood mechanisms operate and especially for whom (Small & Feldman, Citation2012). Moreover, findings from quantitative studies can fuel research agendas for neighbourhood ethnographies. For instance, field observations might reveal in what ways men can obtain part-time jobs in high SES neighbourhoods with the help of their neighbours, or conversely, why this finding from our study might be spurious. Such observations might also explain why we found effects for men in this regard and not for women (cf. Hanson & Pratt, Citation1991). In turn, more specific hypotheses about neighbourhood mechanisms – and to whom they apply – can be formulated, which can be then tested across neighbourhood contexts by conducting quantitative research.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the three anonymous referees and the editor of Housing Studies for their constructive comments. Furthermore, I would like to thank Godfried Engbersen, Erik Snel, and Iris Glas for their continuous support and feedback on earlier versions of this paper. I am also grateful to Joost Jansen for proofreading, to Luc Benda for methodological remarks and to Ingmar van Meerkerk for his comments during the PhD Day.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 People who work in their own neighbourhood might be an exception to this expectation.

2 The survey was available in three different languages, that is, Dutch, English, and Turkish.

3 This included respondents that obtained a higher professional education (HBO) or university degree.

4 In the Netherlands, people who receive social benefits (‘bijstand’) are by law required to search for a job.

5 An additional dummy variable was included in the analyses to account for the missing values.

6 Tenure situation and length of residence are based on personal administrative data that were linked to the survey data.

7 Low incomes are people in the bottom 40% of the national income distribution.

8 Neighbourhood SES and the percentage of higher educated neighbours have quite a strong correlation (r = .50).

9 The Herfindahl index measures the probability that two individuals who are randomly chosen from a closed population belong to the same group (see Abascal & Baldassari, 2015).

10 Models were estimated in R using the ‘lme4’ package, which produces generalized linear mixed models with a maximum likelihood fit (Laplace Approximation).

11 We tested whether we needed to include random slopes for our variables contact frequency with neighbours and willingness to help, which were expected to vary across neighbourhoods. However, models including these random slopes did not have a significant better fit, based on −2Loglikelihood comparisons, than the models including fixed effects.

12 Based on AIC and BIC criteria. These results are available upon request.

13 These intraclass correlations were computed following the latent correlation application described by Rodriguez & Elo (Citation2003).

14 We performed additional tests for our models to check for non-linear relations between our independent variables (contact frequency with neighbours, willingness to help, and neighbourhood SES) and our dependent variable by using dummy variables for the independent variables. These tests did not yield any different results, nor did they provide better model fits.

References

- Abascal, M., & Baldassarri, D. (2015) Love thy neighbor? Ethnoracial diversity and trust reexamined. American Journal of Sociology, 121(3), pp. 722–782.

- Aguilera, M. B. (2002) The impact of social capital on labor force participation: Evidence from the 2000 Social Capital Benchmark Survey. Social Science Quarterly, 83(3), pp. 853–874.

- Andersson, E. (2004) From valley of sadness to hill of happiness: The significance of surroundings for socioeconomic career. Urban Studies, 41(3), pp. 641–659.

- Andriessen, I., Van der Ent, B., Van der Linden, M., & Dekker, G. (2015) Op Afkomst Afgewezen. The Hague: The Netherlands Institute for Social Research (SCP)).

- Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2004) Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. The American Economic Review, 94(4), pp. 991–1013.

- Blokland, T. (2008) Gardening with a little help from your (middle class) friends: Bridging social capital across race and class in a mixed neighbourhood, in: T. Blokland & M. Savage (Eds) Networked Urbanism: Social Capital in the City, pp. 147–170 (Hampshire: Ashgate).

- Blokland, T., & Nast, J. (2014) From public familiarity to comfort zone: The relevance of absent ties for belonging in Berlin’s mixed neighbourhoods. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(4), pp. 1142–1159.

- Blokland, T., & Noordhoff, F. (2008) The weakness of weak ties: Social capital to get ahead among the urban poor in Rotterdam and Amsterdam, in: T. Blokland & M. Savage (Eds), Networked Urbanism: Social Capital in the City, pp. 105–127 (Hampshire: Ashgate).

- Bolt, G., & van Kempen, R. (2013) Introduction special issue: Mixing neighbourhoods: success or failure? Cities, 35, pp. 391–396.

- Brynjolfsson, E., & McAfee, A. (2014) The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies (New York: WW Norton & Company).

- Butler, T., & Robson, G. (2001) Social capital, gentrification and neighbourhood change in London: A comparison of three south London neighbourhoods. Urban Studies, 38(12), pp. 2145–2162.

- Campbell, K. E., & Lee, B. A. (1992) Sources of personal neighbor networks: Social integration, need, or time? Social Forces, 70(4), pp. 1077–1100.

- Cheshire, P. (2012) Are mixed community policies evidence based? A review of the research on neighbourhood effects, in: M. Van Ham, D. Manley, N. Bailey, L. Simpson, & D. Maclennan (Eds), Neighbourhood Effects Research: New Perspectives, pp. 267–294 (Dordrecht: Springer).

- Clampet-Lundquist, S., & Massey, D. S. (2008) Neighborhood effects on economic self-sufficiency: A reconsideration of the Moving to Opportunity experiment. American Journal of Sociology, 114(1), pp. 107–143.

- Curley, A. M. (2008) A new place, a new network? Social capital effects of residential relocation for poor women, in: T. Blokland & M. Savage (Eds), Networked Urbanism: Social Capital in the City, pp. 85–103 (Hampshire: Ashgate).

- Curley, A. M. (2010) Relocating the poor: Social capital and neighborhood resources. Journal of Urban Affairs, 32(1), pp. 79–103.

- Damm, A. P. (2014) Neighborhood quality and labor market outcomes: Evidence from quasi-random neighborhood assignment of immigrants. Journal of Urban Economics, 79, pp. 139–166.

- David, H., Katz, L. F., & Kearney, M. S. (2006) The polarization of the US labor market. American Economic Review, 96(2), pp. 189–194.

- de Souza Briggs, X. (1997) Moving up versus moving out: Neighborhood effects in housing mobility programs. Housing Policy Debate, 8(1), pp. 195–234.

- de Souza Briggs, X. (1998) Brown kids in white suburbs: Housing mobility and the many faces of social capital. Housing Policy Debate, 9(1), pp. 177–221.

- Dirven, H.-J., Michiels, J., & Ter steege, D. (2015) Regionale Verschillen in Arbeidsparticipatie, Werkloosheid en Vacatures (The Hague: Dutch Statistics).

- Doucet, B., Van Kempen, R., & Van Weesep, J. (2011) “We’re a rich city with poor people”: Municipal strategies of new-build gentrification in Rotterdam and Glasgow. Environment and Planning A, 43(6), pp. 1438–1454.

- Eisinga, R., Grotenhuis, M., & Pelzer, B. (2013) The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman-Brown? International Journal of Public Health, 58, pp. 637–642.

- Elliot, J. R. (1999) Social isolation and labor market insulation. The Sociological Quarterly, 40(2), pp. 199–216.

- Engbersen, G., Schuyt, K., Timmer, J., & Van Waarden, F. (2006) Cultures of Unemployment: A Comparative Look at Long-Term Unemployment and Urban Poverty (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press).

- Field, J. (2008) Social Capital, 2nd ed. (Abingdon: Routledge).

- Fischer, C. S. (1982) To Dwell Among Friends: Personal Networks in Town and City (London: University of Chicago Press).

- Galster, G. C. (2008) Quantifying the effect of neighbourhood on individuals: Challenges, alternative approaches, and promising directions. Schmollers Jahrbuch, 128(1), pp. 7–48.

- Galster, G. C. (2012) The mechanism(s) of neighbourhood effects: Theory, evidence, and policy implications, in: M. Van Ham, D. Manley, N. Bailey, L. Simpson, & D. Maclennan (Eds), Neighbourhood Effects Research: New Perspectives, pp. 23–56 (Dordrecht: Springer).

- Galster, G., Andersson, R., & Musterd, S. (2016) Neighborhood social mix and adults’ income trajectories: Longitudinal evidence from Stockholm. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 98(2), pp. 145–170.

- Goos, M., & Manning, A. (2007) Lousy and lovely jobs: The rising polarization of work in Britain. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(1), pp. 118–133.

- Goos, M., Manning, A., & Salomons, A. (2014) Explaining job polarization: Routine-biased technological change and offshoring. The American Economic Review, 104(8), pp. 2509–2526.

- Granovetter, M. (1995) Getting a Job: A Study of Contacts and Careers, 2nd ed. (London: University of Chicago Press).

- Granovetter, M. S. (1973) The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), pp. 1360–1380.

- Hanson, S., & Pratt, G. (1991) Job search and the occupational segregation of women. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 81(2), pp. 229–253.

- Harding, A., & Blokland, T. (2014) Urban Theory: A Critical Introduction to Power, Cities and Urbanism in the 21st Century (London: Sage).

- Jencks, C., & Mayer, S. E. (1990) The social consequences of growing up in a poor neighborhood, in: L. E. Lynn & M. G. McGeary (Eds), Inner-City Poverty in the United States, pp. 111–186 (Washington, DC: National Academy Press).

- Kanas, A., Van Tubergen, F., & Van der Lippe, T. (2011) The role of social contacts in the employment status of immigrants: A panel study of immigrants in Germany. International Sociology, 26(1), pp. 95–122.

- Kasinitz, P., & Rosenberg, J. (1996) Missing the connection: Social isolation and employment on the Brooklyn waterfront. Social Problems, 43(2), pp. 180–196.

- Kleit, R. G. (2001) The role of neighborhood social networks in scattered-site public housing residents’ search for jobs. Housing Policy Debate, 12(3), pp. 541–573.

- Kling, J. R., Ludwig, J., & Katz, L. F. (2005) Neighborhood effects on crime for female and male youth: Evidence from a randomized housing voucher experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(1), pp. 87–130.

- Kloosterman, R. C., & Van Der Leun, J. P. (1999) Just for starters: Commercial gentrification by immigrant entrepreneurs in Amsterdam and Rotterdam neighbourhoods. Housing Studies, 14(5), pp. 659–677.

- Lin, N. (1999) Social networks and status attainment. Annual Review of Sociology, 25(1), pp. 467–487.

- Miltenburg, E. M. (2015) The conditionality of neighbourhood effects upon social neighbourhood embeddedness: A critical examination of the resources and socialisation mechanisms. Housing Studies, 30(2), pp. 272–294.

- Mollenhorst, G. (2015) Neighbour relations in the Netherlands: New developments. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 106(1), pp. 110–119.

- Municipality of Rotterdam. (2016) Neighbourhood Profile., Available at http://wijkprofiel.rotterdam.nl/nl/2016/rotterdam (accessed 3 July 2017).

- Musterd, S., & Andersson, R. (2006) Employment, social mobility and neighbourhood effects: The case of Sweden. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 30(1), pp. 120–140.

- Musterd, S., Ostendorf, W., & De Vos, S. (2003) Neighbourhood effects and social mobility: A longitudinal analysis. Housing Studies, 18(6), pp. 877–892.

- Nguyen, M. T., Rohe, W., Frescoln, K., Webb, M., Donegan, M., & Han, H.-S. (2016) Mobilizing social capital: Which informal and formal supports affect employment outcomes for HOPE VI residents? Housing Studies, 31(7), pp. 785–808.

- Pinkster, F. M. (2007) Localised social networks, socialisation and social mobility in a low-income neighbourhood in the Netherlands. Urban Studies, 44(13), pp. 2587–2603.

- Pinkster, F. M. (2009) Neighbourhood-based networks, social resources, and labor market participation in two Dutch neighbourhoods. Journal of Urban Affairs, 31(2), pp. 213–231.

- Pinkster, F. M. (2014) Neighbourhood effects as indirect effects: Evidence from a Dutch case study on the significance of neighbourhood for employment trajectories. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(6), pp. 2042–2059.

- Portes, A. (1998) Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 24(1), pp. 1–24.

- Putnam, R. D. (2000) Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (New York: Simon and Schuster).

- Reingold, D. A., Van Ryzin, G. G., & Ronda, M. (2001) Does urban public housing diminish the social capital and labor force activity of its tenants? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 20(3), pp. 485–504.

- Rodrıguez, G., & Elo, I. (2003) Intra-class correlation in random-effects models for binary data. The Stata Journal, 3(1), pp. 32–46.

- Sampson, R. J. (2008) Moving to inequality: Neighborhood effects and experiments meet social structure. American Journal of Sociology, 114(1), pp. 189–231.

- Schmidt-Catran, A. W., & Fairbrother, M. (2015) The random effects in multilevel models: Getting them wrong and getting them right. European Sociological Review, 32(1), pp. 23–38.

- Sharkey, P., & Faber, J. W. (2014) Where, when, why, and for whom do residential contexts matter? Moving away from the dichotomous understanding of neighborhood effects. Annual Review of Sociology, 40, pp. 559–579.

- Slater, T. (2013) Capitalist urbanization affects your life chances: Exorcising the ghosts of “neighbourhood effects,” in: D. Manley, M. Van Ham, N. Bailey, L. Simpson, & D. Maclennan (Eds), Neighbourhood Effects or Neighbourhood Based Problems? pp. 113–132 (Dordrecht: Springer).

- Small, M. L., & Feldman, J. (2012) Ethnographic evidence, heterogeneity, and neighbourhood effects after moving to opportunity, in: M. Van Ham, D. Manley, N. Bailey, L. Simpson, & D. Maclennan (Eds), Neighbourhood Effects Research: New Perspectives, pp. 57–77 (Dordrecht: Springer).

- Snel, E., & Engbersen, G. (2009) Social reconquest as a new policy paradigm: Changing urban policies in the city of Rotterdam, in: K. De Boyser, C. Dewilde, D. Dierckx, & J. Friedrich (Eds), Between the Social and the Spatial: Exploring the Multiple Dimensions of Poverty and Social Exclusion, pp. 149–166 (Farnham: Ashgate).

- Snijders, T. A. B., & Bosker, R. J. (2012) Multilevel Analysis (London: Sage).

- Tersteeg, A. K., & Pinkster, F. M. (2016) “Us up here and them down there”: How design, management, and neighborhood facilities shape social distance in a mixed-tenure housing development. Urban Affairs Review, 52(5), pp. 751–779.

- Tersteeg, A. K., Van Kempen, R., & Bolt, G. S. (2015) Fieldwork Inhabitants, Rotterdam (the Netherlands) (Utrecht: Utrecht University).

- Urban, S. (2009) Is the neighbourhood effect an economic or an immigrant issue? A study of the importance of the childhood neighbourhood for future integration into the labour market. Urban Studies, 46(3), pp. 583–603.

- Van Beckhoven, E., & Van Kempen, R. (2003) Social effects of urban restructuring: A case study in Amsterdam and Utrecht, the Netherlands. Housing Studies, 18(6), pp. 853–875.

- Van der Klaauw, B., & Van Ours, J. C. (2003) From welfare to work: Does the neighborhood matter? Journal of Public Economics, 87(5), pp. 957–985.

- Van der Laan Bouma-Doff, W. (2007) Confined contact: Residential segregation and ethnic bridges in the Netherlands. Urban Studies, 44(5/6), pp. 997–1017.

- Van Eijk, G. (2010a) Unequal networks: Spatial segregation, relationships and inequality in the city, Doctoral dissertation, Delft University of Technology.

- Van Eijk, G. (2010b) Does living in a poor neighbourhood result in network poverty? A study on local networks, locality-based relationships and neighbourhood settings. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 25(4), pp. 467–480.

- Van Ham, M., & Manley, D. (2010) The effect of neighbourhood housing tenure mix on labour market outcomes: A longitudinal investigation of neighbourhood effects. Journal of Economic Geography, 10, pp. 257–282.

- Van Ham, M., & Manley, D. (2015) Occupational mobility and living in deprived neighbourhoods: Housing tenure differences in “neighbourhood effects.” Applied Spatial Analysis, 8, pp. 309–324.

- Van Ham, M., Manley, D., Bailey, N., Simpson, L., & Maclennan, D. (2012) Neighbourhood Effects Research: New Perspectives (Dordrecht: Springer).

- Van Kempen, R., & Wissink, B. (2014) Between places and flows: Towards a new agenda for neighbourhood research in an age of mobility. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 96(2), pp. 95–108.

- Vartanian, T. P. (1999) Adolescent neighborhood effects on labor market and economic outcomes. Social Service Review, 73(2), pp. 142–167.

- Volker, B., Andriessen, I., & Posthumus, H. (2014) Gesloten werelden? Sociale contacten tussen lager-en hogeropgeleiden, in: M. Bovens, P. Dekker, & W. L. Tiemeijer (Eds) Gescheiden Werelden: Een Verkenning van Sociaal-Culturele Tegenstellingen in Nederland, pp. 217–234 (The Hague: SCP & WRR).

- Wilson, W. J. (1987) The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy (London: University of Chicago Press).

- Wilson, W. J. (1996) When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor (New York: Vintage).