Abstract

Broadly understood as a housing form that combines individual dwellings with substantial common facilities and activities aimed at everyday living, Danish cohousing communities (bofællesskaber) are often seen as pioneering and comparatively successful. Yet, in spite of frequently being mentioned or addressed as case studies in the growing literature on cohousing and, more generally, alternative forms of housing, Danish cohousing experiences have not been systematically analysed since the 1980s. Emphasizing broader trends and evolving societal contexts, this article investigates the development of Danish cohousing over the past five decades. Through this historical analysis, the article also draws attention to the largely neglected issue of tenure structures in the evolution of cohousing. The multifaceted phenomenon of cohousing cannot and should not be reduced to issues of tenure. But if cohousing is to spread and contribute affordable alternatives to mainstream housing, tenure structures should be a key concern.

Keywords:

Introduction

We have in recent years seen a revival of cohousing in (and beyond) North America and Europe (Sargisson, Citation2012; Tummers, Citation2016b). This has produced significant academic interest, and cohousing is increasingly if patchily embraced by decision-makers as a means to address issues of urban sustainability. Broadly understood as a housing form that combines individual dwellings with substantial common facilities and activities aimed at everyday living, cohousing is also experiencing a revival in Denmark. However, Danish cohousing has evolved over a period of five decades. In fact, it was on the basis of Danish experiences with bofællesskaber (roughly meaning living or housing communities) that McCamant & Durrett (Citation1988) allegedly coined the term ‘cohousing’ (cf. Vedel-Petersen et al., Citation1988, p. 101), and in the most recent edition of their influential book, McCamant & Durrett (Citation2011, p. 37) characterize Danish cohousing as ‘the gold standard for cohousing world-wide’. This characterization can certainly be debated, but cohousing has not only become a well-established alternative to mainstream housing in Denmark; Danish cohousing is also routinely seen as pioneering and comparatively successful (e.g. Tornow, Citation2015). Nonetheless, and somewhat surprisingly considering how often Danish experiences are mentioned or addressed as case studies, the development of Danish cohousing has not been systematically investigated since the 1980s.

This article investigates the history of Danish cohousing beyond the existing case studies of individual communities. This entails a ‘macro’ perspective that cannot address the myriads of often bottom-up struggles and experiences that are covered in much of the evolving cohousing literature (for recent reviews, see Lang et al., Citation2018; Tummers, Citation2016a). As Jarvis (Citation2015, p. 94) points out, cohousing as a ‘living arrangement’ of ‘social architecture’ obviously ‘represents much more than simply an alternative system of housing’. But by examining how cohousing has evolved within broader social, economic and political trends over some fifty years, the analysis can provide context for detailed analysis and comparisons, and it can help to bring out overlooked concerns. It is in the latter respect that the article aims to make a general contribution from its specific analysis, namely to draw attention to the under-studied issue of tenure forms in cohousing. Chiodelli (Citation2015) closes in on this issue when comparing cohousing with gated communities, while Blandy (Citation2013) presents a fascinating analysis of property as lived process in cohousing. But the issue of tenure (or ownership) forms is mainly addressed in passing or as a subset of other concerns, typically the important issues of access, affordability and social inclusion in cohousing (e.g. Chatterton, Citation2015; Garciano, Citation2011; Jakobsen & Larsen, Citation2018).

It is the contention of this article that tenure forms are important for cohousing initiatives – and how we evaluate them – in several respects. First, and vividly illustrated by the Danish history, tenure forms can be of key importance for how effectively cohousing ideas are realized in actual communities. Second, tenure forms have implications for who can access cohousing. This housing form is frequently seen as contributing to sustainable (urban) development and living (e.g. Vestbro, 2010). But if sustainability is to include dimensions of affordability and social inclusion, then tenure must be central. Third, cohousing is often evoked as a way to challenge the commodification of housing, which is to say that housing ‘is seen as predominantly a traded commodity which is valued for its financial status, rather than as a human right or a product valued for its use rather than its exchange value’ (Clapham, Citation2018, p. 4). For Tummers (Citation2015), for instance, the non-speculative nature of cohousing initiatives is a recurring feature. While obviously a shorthand symbol, tenure forms say something important about relationships between occupancy and ownership. Finally, although not investigated in this article, tenure forms can have important implications for the functioning of realized cohousing communities. In Denmark, for example, a community based on cooperative tenure can prioritize the access of younger people to an aging community. This is not possible in owner-occupied communities, where units are exchanged individually on the private property market. Spurred on by such concerns, and borrowing from Cox’s (Citation1994) conceptualization of ‘critical’ (as opposed to ‘problem-solving’) research, this article aims to take a step back from the existing tenure order of Danish cohousing to question how that order came into being and how it may be challenged, if that is deemed necessary. And following from this, the article seeks to address the wider question: What is the role of tenure forms in the development and accessibility of cohousing?

Focusing on tenure is not unproblematic. For a start, there is the problem of identifying tenure ‘types’ and dealing with the bewildering differences between ostensibly similar typologies across jurisdictions (Ruonavaara, Citation1993). Even in a small country, like Denmark, ‘owner-occupied’ covers several different and historically contingent forms of property relations, for example, while ‘housing cooperative’ has significantly different meanings when applied to, say, Denmark, Norway and Sweden (Larsen & Lund Hansen, Citation2015; Sørvoll & Bengtsson, Citation2018). More fundamentally, as argued by Barlow & Duncan (Citation1988), conceptions of housing tenure can be misused in several ways, for example to assume that taxonomic tenure types correspond to substantive categories such as social status. Nonetheless, tenure structures are powerful institutions, which can facilitate as well as obstruct the formation of and access to cohousing communities, and as Tummers (Citation2016a, p. 2036) more generally points out in relation to the cohousing literature, ‘the absence of institutional context may lead to a misreading of case studies’. Still, focussing on tenure can only be a first (and rather blunt) step in opening up the issue of property relations in research on cohousing and alternative forms of housing in generally. As Blomley (Citation2016a, Citation2016b) argues, property relations are not universal and singular, but complex and lived. The same should apply for the seeming singularity of tenure forms, although this article can only hint at the complexities and lived worlds of property in cohousing (cf. Blandy, Citation2013).

To encompass its dual purpose of analysing the historical development of Danish cohousing and the role of tenure forms, the article consists of three main sections that address each of the three phases of Danish cohousing, which the article identifies and starts out by introducing in the next section. The first two phases are addressed in greatest detail, as they illustrate the formation of some core features of Danish cohousing. To contextualize these developments, the analyses of the first and second phases are preceded by shorter sections that respectively emphasize the broader societal background that engendered Danish cohousing and the criticism this housing form occasioned as the first phase gave way to the second. The third and current phase is essentially a continuation of, and a return to, the past – if under new conditions. Therefore, the analysis of the third phase focuses on the context in which the now well-established features of Danish cohousing are articulated and opens a discussion of implications of tenure forms for cohousing.

Three phases of cohousing

This article’s focus on tenure forms derives from a larger, interdisciplinary project on cohousing and urban sustainability in four European countries, including Denmark. Danish cohousing communities are not systematically registered by any public or private entity. Therefore, we sought to compile a reasonably comprehensive list of communities using the Internet website bofællesskab.dk and other sources, including inputs from cohousing residents (see, Jakobsen & Larsen, Citation2018). The resulting list of 110 intergenerational cohousing communities is not exhaustive. There are undoubtedly communities we have failed to register, and in some cases, it is difficult to draw a clear line between ‘cohousing’ and kindred forms of collaborative housing. Some eco-villages have not been included (cf. Marckmann et al., Citation2012), for example, and cohousing reserved for particular groups – notably senior cohousing – is similarly left out (for a quantitative assessment of Danish senior cohousing, see Pedersen, Citation2015). Still, the list is the most complete and systematic record of ‘traditional’ Danish cohousing communities today. Based on the list, we conducted a survey that was completed by 72 communities. For the remaining communities, basic data on location, establishment, size and form of tenure was compiled using Internet sources, primarily community homepages. This analysis only captures communities that still exist, but very few cohousing communities have dissolved – once they have negotiated the thorny establishment phase.

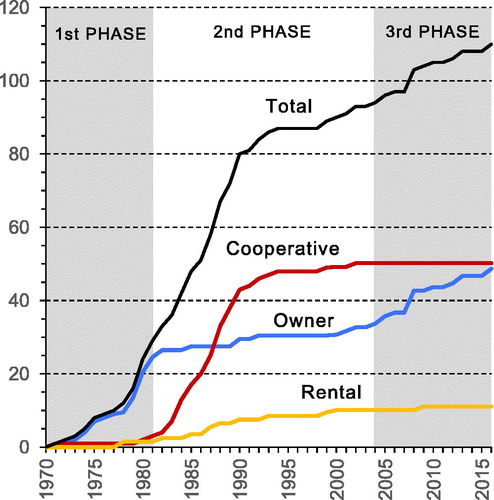

Although modest in comparison to the flourishing of cohousing communities during the 1970s and 1980s, the collected data shows that Denmark has also experienced a recent revival in the establishment of cohousing communities (). The communities established over the past fifteen years are almost exclusively based on owner occupation, as in the 1970s when cohousing first emerged. But throughout the five decades represented in , cohousing communities have also utilized other tenure forms (for an overview of Danish tenure forms, see Kristensen, Citation2007). Most prominent in this respect is the surge of new cohousing communities based on cooperative tenure during the 1980s. Setting aside rental cohousing, for a start, it is thus possible to identify three phases of Danish cohousing with respect to the dominant tenure form of new communities (). And as these phases importantly tie in with general changes in housing legislation, notably the introduction and eventual termination of state support for new-build housing cooperatives, these phases can be dated quite precisely. It should be noted, however, that although the second phase formally can be delimited to the period 1981–2004, the period of cohousing based on cooperative tenure effectively culminated in the early 1990s (see below).

Figure 1. Danish intergenerational cohousing communities by tenure form, 1970–2016 (cumulative count of 110 communities). New communities are listed by the year that the first members took up residence. Source: Jakobsen & Larsen (Citation2018)

To investigate and contextualize the three phases represented in , the article is mainly based on a systematic analysis of writings on Danish cohousing and related topics over the past five decades. This includes academic analyses, newspaper and journal articles, public reports and publications by cohousing communities. Several of these sources are ‘primary’ in the sense that they are not based on other (preserved) sources and are historically closer to the analysed events than, for example, a present-day interview. While by no means exhausting the issue, this analysis revealed three intersecting features of Danish cohousing: (1) separation between private and common, (2) spatial form in terms of architecture and location, and (3) dominant forms of tenure. These three features guide the analysis of the three phases of Danish cohousing, which relate to but are distinct from wider historical changes in Danish housing. The two first features link up with broader debates on cohousing, notably on social architecture (e.g. Jarvis, Citation2015) and built form (e.g. Williams, Citation2005). The third feature, tenure forms, is a staple of housing studies. But as already suggested, this feature has received little systematic attention in relation to cohousing. All translations have been made by the author for the purpose of this article.

A child of the 1960s

A little over a decade after people took up residence in what is generally seen as the first Danish cohousing communities, Sættedammen (est. 1972) and Skråplanet (est. 1973),1 Hansen (Citation1984a, p. 240) described cohousing as a ‘Child of the 1960s’ and ‘a new critical awareness of cultural, social and political circumstances.’ Taking inspiration from the Soviet Union and particularly Sweden, a few so-called collective houses (kollektivhuse) had been built in the 1930s and 1950s (Langkilde, Citation1970). But in stark contrast to these projects, which sought to rationalise everyday life in order to make women in particular available to the labour market, the visions from which Danish cohousing emerged were in part a revolt against the conventional family: ‘Collective community should replace the isolated nuclear family’, as Hansen (Citation1979, p. 55) put it. This vision loomed large in two influential feature articles on alternative child-rearing and family life by Graae (Citation1967, Citation1969), which, for example, provided the ideational basis for the Sættedammen and Overdrevet (est. 1980) communities (Bendixen et al., Citation1997; Ove R. Drevet, Citation1982).

Such ideas grew out of the many different strands of developments, which reached their symbolic (and rebellious) apogee in 1968. Set within a broader socio-economic context of mounting prosperity and the ‘golden years’ of the welfare state (Petersen et al., Citation2012), one of these developments was the emergence of a significant ‘commune movement’ during the 1960s. In their seminal study, Christensen & Kristensen (Citation1972) estimate that there by 1971 there were more than 700 of these usually small communes (kollektiver), which Christensen and Kristensen see as based on a ‘commune dream’ that emphasized shared economy, absence of property rights, gender and power equality, common child-rearing, voluntary division of labour, dissolution of one-to-one relationships and common outward-directed political and creative activities. But the spirit of 1968 also generated visions for broader settlement structures. A vivid example is The Langeland Manifesto – named after an island that became the focus of intense communal activities (Rasmussen, Citation2017) – in which two well-known members of the Maos Lyst (Mao’s Pleasure) commune set out seven fundamental demands for profound social change, including ‘the right to close, human community’ (Reich & Prins, Citation1977, p. 2). First published in 1972, the manifesto outlines a vision of Denmark in which thousands of intergenerational settlements of 200–1000 individuals supersede the work-home separation of late capitalism and become foundations for a loosely federalized wider community.2 As is often the case in utopian visions, the manifesto contains a solid measure of – possibly ‘progressive’ (Jarvis & Bonnett, Citation2013) – nostalgia: ‘What once was a great community, which included all age groups and resisted all pressures in solidarity, has become a two-and-a-half room flat with a mother and two-three children and, at best, a father’ (Reich & Prins, Citation1977, p. 8). However, it was not only from the more or less declared Left that radical visions of this sort were voiced. Co-authored by a prominent social-liberal politician, the much-debated Revolt from the Centre also includes visions of a society restructured into small, mainly rural units based on fundamental participation (Meyer et al., Citation1978, Citation1981). It is notable that this utopian proposal, like The Langeland Manifesto, is ‘anti-urban’ in the sense that it favours small and geographically disbursed village-like communities. In significant part, Nygaard (Citation1984) sees this as a national-romantic reaction to developments such as Denmark’s entry into European Economic Community in 1973. While not necessarily for this reason, the Danish cohousing communities generally also assumed the spatial form of village-like developments in suburban or quasi-rural settings (for a map, see Jakobsen & Larsen, Citation2018).

In relation to housing and everyday living, developments in the years around 1970 were clearly conductive for experimentation and collectivism (Schultz, Citation1984). It is indicative, for example, that a pioneering attempt at setting up a cohousing community was obstructed by neighbours in 1964, but only a few years later, cohousing experiments were met with much interest and little resistance (Gudmand-Høyer, Citation1984b). The wave of generally small communes that gathered force from the mid-1960s was undoubtedly an inspiration. The Sættedammen community at first described itself as a ‘kollektiv’ (a commune) (Bendixen et al., Citation1997), for example, and the first recoded use of ‘bofællesskab’ appeared in a newspaper notice seeking people interested in forming a ‘kollektivlignende bofællesskab’ (a commune-like cohousing community) (Anonymous, Citation1971, p. 5; Jarvad, Citation1999). And well into the 1980s, Andersen & Lyager (Citation1984) found it necessary to distinguish between ‘actual communes’ and cohousing, while Reich & Bjerre (Citation1984) wrote about ‘small’ and ‘big’ cohousing communities, the former being another term for communes. The collectivist spirit also spurred larger experiments such as Thylejren (est. 1970) in Northern Jutland and Christiania (est. 1971) in Copenhagen (Buus et al., Citation2010; Thörn et al., Citation2011). Yet in Denmark, as in the Netherlands and Sweden, for example, ‘cohousing emerged as a mainstream housing option, despite being underpinned by many of the principles and practices of its predecessor communes’ (Meltzer, Citation2005, p. 6). It is in this respect possible to recognize three intersecting features that distinguish (Danish) cohousing communities: a separation between private homes and common facilities, the spatial form this typically came to take in Denmark, and the tenure forms that were adopted to realize cohousing projects. These three features emerged during the first phase of Danish cohousing.

First phase: the missing link

One clear distinction between the small communes in particular and the emerging cohousing communities was and remains today an emphasis on self-contained and private household units within a larger collective setting. This was already suggested in a pioneering feature article by Jan Gudmand-Høyer (Citation1968, p. 3), which made a passionate plea for probing the ‘practical possibilities of realising “the missing link” between utopia and the outdated single-family house’. Gudmand-Høyer was somewhat vague on the nature of this ‘missing link’, but he suggested a vision of a housing form that could further ‘interplay between common and private spaces’. If the contemporaneous feature articles by Bodil Graae inspired visions of alternative everyday life in the emerging Danish cohousing communities, Gudmand-Høyer’s article – and his work as architect in and on behalf of pioneering cohousing communities – had an influence on their concrete form. In contrast to the communes, where borders between private and common could blur considerably, a core feature of Danish cohousing became an emphasis on a separation between the private (but not necessarily individually owned) and the common. A material hallmark of the collective dimension is the ‘common house’ with, among other features, facilities for cooking and eating common meals. While also stressing procedural and organizational dimensions, this is arguably the fundament material dimension of Danish cohousing that was internationalized by McCamant & Durrett (Citation1988) (also McCamant & Durrett, Citation2011, p. 5). Likewise, if not necessarily directly derived from Danish experiences, this private/common separation is central to most wider characterizations of cohousing. For Lietaert, for example, ‘Cohousing communities are neighbourhood developments that creatively mix private and common dwellings to recreate a sense of community, while preserving a high degree of individual privacy’ (Lietaert, Citation2010, p. 576). In the Danish context, Navne (Citation1987, p. 11) characterizes cohousing as ‘several, fundamentally independent living-units, which are inhabited by families, individuals or groups that cooperate on a range of activities in relation to their daily household work’. Similarly, a report taking stock of what by the late 1980s had become a well-established housing form defines cohousing as:

a housing group which involves a number of independent homes with additional common facilities, such as common rooms and open spaces. […] It is a characteristic of [cohousing communities] that the use of common facilities and the occurrence of activities such as common dinners, are supplementary features, because the individual dwellings are completely equipped with, amongst other things, their own kitchens. (Vedel-Petersen et al., Citation1988, p. 101).

Partly to facilitate the characteristic mix of private and common, Danish cohousing generally adopted a distinct spatial form that became known as the ‘dense-low’ (‘tæt-lav’) architecture (Jantzen & Kaaris, Citation1984). During the 1970s, this became ‘the architecture of the new Left’, in which the ideal was to ‘build low to preserve relations to nature and dense to achieve social contact’ (Nygaard, Citation1984, p. 227, 230). Not confined to cohousing, but embodying the wider aspirations for community that nourished the emergence of cohousing, this dense-low architecture is particularly associated with a 1971 ‘idea competition’ by the Danish Building Research Institute, which, in the spirit of the time, aimed to link architecture and planning to include ‘new family forms and groups’ (Byggeforskningsinstitut, 1972, p. 2). The competition was won by a newly established architectural firm, Vandkunsten, which in a poetic and clearly Left-leaning entry outlined some features that came to characterize many cohousing communities (several of them using Vandkunsten as architects). Most visibly, this model is based on green spaces with detached or semi-detached houses organized around a common house. Looking back at some fifteen years of cohousing development, Hansen acknowledges that cohousing communities come in many different forms, but that these communities have some structural commonalities: ‘a ring of dense and low buildings around some form of common space is the most general image of the contemporary Danish cohousing community’ (Hansen, Citation1984b, p. 17). Hansen also recognizes that these communities mainly have a ‘somewhat solitary location’ in the urban periphery. This contrasts with the Swedish trend of establishing cohousing in existing urban estates (Caldenby & Walldén, Citation1984; Sandstedt & Westin, Citation2015). As Lund (Citation1981) points out in a theme issue of Blød By that examines 10 years of dense-low (co)housing experiences, the quasi-rural Danish cohousing communities have antecedents, such as Ebenezer Howard’s vision of the garden city, and associated visions of the ‘evil city’ set against the ‘good countryside’. Nonetheless, the architecture of dense-low housing in the urban periphery became almost synonymous with Danish cohousing. A few communities have retro-fitted existing structures, for example Jernstøberiet (est. 1981), or utilized existing buildings, typically for common facilities. But the private/common socio-spatial character, and the often associated dense-low architecture, mean that most Danish cohousing has been (and still is) purpose built. However, as in cohousing elsewhere (Jarvis, Citation2011), private residences are typically smaller than the general average, in order to leave space and financial resources for common facilities.

Somewhat paradoxically, considering that it emerged in many respects from criticisms of established society, early Danish cohousing was almost exclusively based on that hallmark of bourgeois society: individual property rights in the form of owner-occupation ().3 Contrary to some suggestions (e.g. Egerö, Citation2014; Meltzer, Citation2005), public housing rented through non-profit housing associations (almennyttige boliger, now almene boliger) never took a lead in Danish intergenerational cohousing.4 There are at least three intersecting reasons for this. First, in the years around 1970 there were few existing models other than some form of owner-occupation for groups that wanted to create (legal) alternative housing forms (it is necessary to emphasize legality here, as other contemporaneous attempts to provide housing alternatives relied on squatting, most famously in the case of Christiania). Second, while rental public housing could have been a model, this sector did not (at the time) leave much room for the direct participation and experimentation that aspiring cohousing communities sought – and still seek. In relation to one of the first cohousing communities including public housing tenure (Drejerbanken, est. 1978), for instance, an analysis concluded that the ‘rules for [state-] supported public housing do not leave many options for even limited experimentation’ (quoted in Byggeriets Udviklingsråd, 1983, p. 13). One of the few other examples of cohousing based on public housing, Tinggården (est. 1979), was the material result of Vandkunsten’s winning entry for the ‘dense-low’ competition. Third, it could be argued that that would-be cohousing communities primarily wanted to experiment with alternative forms of living and everyday life, and that structural questions about property relations in that respect were secondary. The pioneering feature articles by Graae and Gudmand-Høyer make no reference to property issues (or affordability), for example. This is not to say that property relations were not an issue during the first phase of Danish cohousing. A central problem in this respect was how to accommodate the mix of private dwellings and common facilities. This led to rather inventive ownership structures. For example, the group behind what eventually became the Sættedammen community first established itself as a private limited company (aktieselskab), which subsequently (for tax purposes) was reorganized as a private partnership company (interessantselskab) (Bendixen et al., Citation1997; also, Illeris, Citation2018). However, most owner-occupied cohousing communities have solved the issue by defining the private dwellings as individual property, while common spaces and buildings are owned and managed collectively through some form of compulsory organization. This is usually the model of an owners’ association, typically set up for buildings of owner-occupied flats (condominiums) – a model which in Denmark became a legal possibility in 1966.

Well-to-do communes

In the early 1980s, Hansen (Citation1984b, p. 15) declared the model of dense-low cohousing to be ‘the most original Danish architecture that has been produced over the past ten years’ (cf. Dirckinck-Holmfeld, Citation1984). Others passed far less enthusiastic verdicts. For Mogensen (Citation1981, p. 49), the dense-low vision was a ‘narrow product of the 1960s – an ideal image of those currents, which at a particular historical juncture manifested themselves in a narrow stratum of the population: the radicalized segments of the middle class’. Writing at a time when the stagflation crisis began to bite into the welfare state (Petersen et al., Citation2013), and when the ‘anarchic and imaginative spirit’ of 1968 was giving way intellectually to dogmatic forms of Marxism as well as a renewed concern for the urban (Nygaard, Citation1984, p. 227), Mogensen judged cohousing communities to be ‘snug places’ where the educated class could cuddle up with their peers in ‘cold times’. For Lund (Citation1981, p. 37), these ‘utopian escapes’ were:

marginal solutions that do not contribute much to the reconstruction of our cities – the fundamental task of the next decade. Rather than attempting to re-cultivate the city’s ideology, they have become flirtations with the countryside. One works in the city but seeks rest among equals far from its roar. The single-family dream has been multiplied by twelve or fifteen. That does not make it any better.

Others assessed the emerging phenomenon of cohousing more positively (e.g. Andersen, Citation1985; Johnsen, Citation1981). It is significant, however, that by the early 1980s cohousing as ‘bofællesskab’ was a sufficiently distinct housing form to become a subject of debate. The critical assessments mainly inserted cohousing into structural critiques, which went beyond the circumscribed aims of most cohousing communities. Nonetheless, some had far-reaching ambitions from the outset. ‘In a way,’ Kløvedal (Citation1981, p. 21) reflected, ‘we accepted “the reform” as the road to “the revolution”; house building as a road to social change.’ But Kløvedal was ‘furious’ when he saw the pragmatic result of what he had helped to conceive – Tinggården, Vandkunsten’s winning entry in the dense-low competition. Possibly as a belated reply to the criticism of the 1980s, on the other hand, Bjerre (Citation1997, p. 70) saw cohousing as a ‘quiet rebellion’ that ‘sprouts “from below” with irresistible force’, and reflecting the environmental concerns that took hold around 1980 in and beyond cohousing, he found that cohousing could be ‘a bastion’ in ‘a global, green rebellion’ against capitalism – ‘if they are capable of seeing themselves in a larger context’.

Whether assessed positively or negatively, many in the early 1980s noted that access to cohousing communities was restricted. Particularly because of the owner-occupied tenure of most communities, they could be seen as ‘well-to-do communes’ (velhaverkollektiver) (Nygaard, Citation1984, p. 251). Some of those engaged in the planning of the Overdrevet community (est. 1980) could not afford to move in, for example (Ove R. Drevet, Citation1982). More generally, a report aimed at promoting cohousing found that due to ‘demands on personal and economic resources’, cohousing had not become as widespread as it could, and the report concluded that ‘the privately-owned cohousing communities will remain reserved for a rather small group of the better-off’ (Byggeriets Udviklingsråd, 1983, p. 20). However, the early 1980s also marked an important shift in the structure of Danish cohousing, which many saw as a golden opportunity to continue the notable if still modest success in establishing cohousing communities, not least by making the housing form more affordable. This marked the second phase in the development of Danish cohousing.

Second phase: the Volkswagen of cohousing

In the second phase of Danish cohousing, two of the three features that emerged during the first phase persisted. First, this involved a continuation of the mixing of private dwellings with common facilities and activities, though the nature of the common activities in particular often took other forms than expected. The Sættedammen community had originally expected children to be a pivot of common activities, but somewhat unexpectedly, shared meals assumed this role (Bendixen et al., Citation1997, p. 12; also, Illeris, Citation2018). In fact, common cooking and shared meals, usually with an option of cooking and/or eating privately, have become a hallmark of communal activity in Danish cohousing. Tellingly, the Overdrevet community made ‘Do you really eat together every day?’ the title of its silver jubilee publication (Ove R. Drevet, Citation2005). Second, although not dense-low architecture in the strictest sense, the spatial form of the first phases persisted during the second. Some communities established themselves in urban settings, but most cohousing continued to be established as low, detached or semi-detached houses in suburban or quasi-rural contexts. Prompted by the energy crises and the wider rise of environmental awareness, greater attention to the environment and ecology was arguably the main change in new cohousing during the 1980s (Nygaard, Citation1984). In some cases, this is reflected in the naming of communities, for example Sol og Vind (Sun and Wind) (est. 1980) (Byggeriets Udviklingsråd, 1982). This fed into the subsequent development of eco-villages, which in several cases overlap with cohousing (Marckmann et al., Citation2012). It is in relation to the third feature, the dominant tenure form, that the second phase marks a fundamental shift. For while the pioneering cohousing communities of the 1970s with only a few exceptions were owner-occupied, the communities that were established during the 1980s were overwhelmingly based on cooperative tenure (). Because this made cohousing ‘accessible to a much wider group of people’, some wittily dubbed this model ‘the Volkswagen of cohousing’ (Bjerre & Sørensen, Citation1984, p. 43).

Cohousing communities of the second phase essentially tapped into a revival of cooperative tenure in Danish housing politics during the 1970s and 1980s. Cooperative tenure played a key role in the formation of alternatives to owner occupation and rental housing from around 1900, but cooperative housing was from the 1930s largely absorbed into what became public housing owned by non-profit housing associations. From the mid-1970s, however, new legislation made it easier to establish housing cooperatives (andelsforeninger). This tenure takes the form of limited equity cooperatives in which the property is owned collectively by an association. Members of such housing cooperatives have a right of use to a dwelling, and membership is accessed through the purchase of a ‘share’ (andel), which is valued by set formulae outlined by law rather than ‘free’ market value (Bruun, Citation2011; Larsen & Lund Hansen, Citation2015). This form of tenure was revitalized when legislation in 1975 gave tenants a first option (tilbudspligt) to buy existing rental housing and form a housing cooperative, should their landlord choose to sell (Jonasson, Citation2010). But from 1981, and more significant for cohousing communities, additional legislation made it possible to apply cooperative tenure to newly built housing (Erhvervsministeriet, 1980). More specifically, the 1981 law allowed housing cooperatives to cover 80 per cent of construction costs through loans on which they should pay index-linked instalments while the state covered accrued interest. This option was regulated by quotas, however; the Ådalen 85 community (est. 1988), for example, had to wait several years before it was granted a quota (Ådalen 85, n.d.).

The 1981 law was, as McCamant & Durrett (Citation1988, p. 142) put it, ‘a windfall for cohousing’. This description is apt, for the law was passed to aid a depressed construction industry, not to assist cohousing. But, as Reich & Bjerre (Citation1984, p. 5) pointed out, this opened up ‘a hitherto unknown opportunity for people who wish to set up cohousing communities who did not have much money for which to do so’. Reich and Bjerre’s text was the first in a series of feature articles in the newspaper Information, which from the 1970s became a key arena for debates on all dimensions of the new social movements. These interventions sought to draw attention to ‘the unused forces of community’, not least through a cohousing movement reenergized by cooperative tenure (Brydensholt, Citation1984; Gaardmand, Citation1984; Gudmand-Høyer, Citation1984b; Kjeldsen, Citation1984; Meyhoff, Citation1984; Reich & Bjerre, Citation1984). This enthusiasm did not pass unchallenged. In line with the structural criticism noted in the preceding section, a reader questioned whether cooperative tenure would truly widen the socio-economic composition of cohousing, and he suggested that ‘the unused forces of community’ should be applied to change ‘the private-capitalistic society so that the cohousing communities can benefit all social groups’ (Petersen, Citation1984, p. 9). Interestingly, the reader predicted that housing cooperatives in a capitalist society would eventually be capitalized. Some twenty years later, this was exactly what befell Danish housing cooperatives (Bruun, Citation2018; Larsen & Lund Hansen, Citation2015), but how this has affected cohousing based on cooperative tenure remains to be analysed.

Cooperative tenure seems to have furthered or at least sustained the remarkable expansion of cohousing communities during the 1970s and 1980s (). It is difficult to retrospectively establish whether the introduction of cooperative tenure widened the socio-economic composition of new cohousing communities. But a calculation based on the legal and economic conditions of the early 1980s suggests that housing costs in owner-occupied cohousing in the first year (depending on loan types) would be 34–85 % above the costs for comparable cohousing based on cooperative tenure (Udviklingsråd, 1983). This difference would slowly decrease after the establishment of a community, but the example clearly suggests that cooperative tenure could significantly lower the financial barriers to cohousing. Moreover, based on detailed data on one of the first cooperative-tenure cohousing communities, Uldalen (est. 1983), Bjerre & Sørensen (Citation1984) found that while owner-occupied cohousing typically presupposed each household to include two relatively high and stable incomes, the composition of Uldalen was different. Single breadwinners occupied half of the 18 units, and in contrast to the predominance of academics in owner-occupied cohousing, around three-quarters of the thirty adults in Uldalen had vocational training or were students. Moreover, at a time marked by unemployment, 26 per cent were unemployed when they movied in. A somewhat later analysis confirms that cooperative-tenure cohousing communities were more diverse than owner-occupied ones with respect to age, income occupation and family structure (Vedel-Petersen et al., Citation1988). This tallies with Werborg’s (Citation1996) general assessment of housing cooperatives as socio-economically ‘in between’ rental and owner-occupation. Still, Bjerre & Sørensen (Citation1984, p. 43) observed that the Uldalen community was ‘dominated by middle-class public employees,’ and ‘in that respect there is probably little difference from the known [i.e. owner-occupied] cohousing communities’.

Cooperative tenure was highly attractive to cohousing communities. On one hand, this tenure form was more affordable and simpler to apply than owner occupation. On the other hand, and in contrast to the highly regulated public housing sector, cooperative tenure also provided members with the autonomy to develop and run cohousing projects. New cohousing communities would probably have been established without the introduction of state support for housing cooperatives, but it is reasonable to assume that state support facilitated the significant growth of cohousing communities during the 1980s. This is supported by the fact that most state-supported (and quota-regulated) housing cooperatives were constructed in the period 1981–1991 (Erhvervs- og Byggestyrelsen, Citation2006), and it is also in the early 1990s that we – for a while – see a pause in the establishment of new cohousing communities (). But cohousing groups were not the only groups to see opportunities in producing state-supported housing cooperatives. In some cases, cooperative tenure became a means to produce housing that is owner-occupied in all but name – with state support (Andersen, Citation2006). Partly for this reason, but also due to shifting state priorities in a situation of economic recovery and improving conditions for the construction industry, notably but not exclusively in Greater Copenhagen (Andersen & Winther, Citation2010; Clark & Lund, Citation2000), state support for new-build housing cooperatives was gradually phased out and eventually terminated in 2004 (Erhvervs- og Byggestyrelsen, Citation2006). Thus, while the introduction of state support for the construction of housing cooperatives was a ‘windfall’ of wider developments for would-be cohousing communities, the benefits of cooperative tenure for cohousing initiatives were also undermined by wider developments.

Third phase: a practical lifebelt

While the 1970s and 1980s were the ‘golden age’ in the establishment of cohousing communities (), Denmark has since the late 1990s seen a revival of intergenerational cohousing. Or, more precisely, new communities continue to be formed, if under new conditions. McCamant & Durrett (Citation2011, p. 5) suggest that there were more than 700 Danish cohousing communities by 2010. If we focus on the ‘traditional’ form of intergenerational cohousing communities, this estimate is clearly too high (for other high estimates, see Daly, Citation2015; Sargisson, Citation2012). Not all communities are captured by the analysis that informs , but a qualified estimate would be that there are no more than 150 ‘traditional’ intergenerational cohousing communities in Denmark today; that is, communities that maintain a balance between the common and the private and are not reserved for particular groups. Still, the often (too) high estimates of cohousing in Denmark are indicative, as they suggest how successful the notion of ‘bofællesskab’ has become. Most closely related to the ‘traditional’ intergenerational communities are the approximately 250 senior cohousing communities (seniorbofællesskaber) that have been established over the past three decades (Pedersen, Citation2013, Citation2015). But since it became possible in the mid-1980s to establish ‘municipal cohousing communities’ (kommunale bofællesskaber) for adults with ‘extensive physical and psychological disabilities’ (Boligministeriet, Citation1992, p. 6), the notion of cohousing has been extended to housing for groups with special needs, including groups of socially excluded people (Jensen et al., Citation1997). Most recently, this has also come to involve guidelines for ‘collective cohousing’ (kollektive bofællesskaber) for refugees (Retsinformation, 2016). While most of these adaptions fall short of the original meaning of cohousing as bofællesskab, they do suggest the positive connotations that have become attached to the notion. In the Hertha community (est. 1996), for example, intergenerational cohousing is combined with a living and working community for adults with disabilities (Hertha, 2016).

Focusing on the ‘traditional’ intergenerational form, the third and current phase of Danish cohousing is essentially a continuation of, and a return to, the features that came to characterize this housing form during the earlier phases. The separation between private and common remains a characteristic feature, and while there are exceptions, most new cohousing communities continue to be village-like developments in suburban or quasi-rural settings. In part, this non-urban character relates to the price of land. This was a factor for the suburban location of the Lange Eng community (est. 2008), for example (interview 8 May 2015). But apart from questions of price (and related issues of housing quality), anti-urban motives generally remain a reason for settling in non-urban milieus (Aner, Citation2016). In the perspective of this article, the key change is the return to owner-occupation as the dominant tenure form (). This does not imply that everything remains (or has return to) the way it was. Before turning to the issue of tenure, two contextual developments should be noted.

First, while cohousing was previously mainly a ‘windfall’ beneficiary of wider changes such as a broader acceptance of communal alternatives in the 1970s and state support for new-build housing cooperatives in the 1980s, there is now a growing interest in cohousing among policy-makers. This is exemplified by three government-commissioned reports aimed at promoting cohousing (Dansk Bygningsarv, 2016; Second City, 2016; Urgent.Agency & LB Analyse, 2016). But as in cities such as Barcelona, Hamburg and Gothenburg (Montaner, Citation2016; Scheller & Thörn, Citation2018), some municipalities, for instance Odsherred and Roskilde, are now actively trying to assist the establishment of cohousing communities. This contrasts with the previous lack of municipal interest in cohousing (Gudmand-Høyer, Citation1984b). Such political interest in to cohousing is in large part driven by a perceived competition between cities for socio-economic ‘attractive’ residents and concerns about the emergence of an ‘outer Denmark’ (Udkantsdanmark) – that is, depopulating areas peripheral to the prospering metropolitan regions (Carter et al., Citation2015). Cohousing is, in other words, used as an instrument of urban and regional policy (on local development and alternative housing in other countries, see e.g. Lang & Stoeger, Citation2018; Mullins, Citation2018). ‘Cohousing communities as drivers of regional development’ is the telling subheading of one report, which continues to pose the question: ‘Can cohousing play a part in reversing the development in provincial Danish towns that struggle with population flight, empty shops, dying city centres and school closures?’ (Urgent.Agency & LB Analyse, 2016, p. 8). The report does not answer this question. But tapping into notions of the sharing economy and rehearsing longer-standing trends such as sustainability, new work structures and pluralistic family patterns, the report lists some recommendations for how particularly municipalities can mobilize cohousing. ‘Can these units [of cohousing] – the new goldmine – live up to politicians’ expectations?’ asked a well-informed newspaper article when the government-commissioned reports were published (Stensgaard, Citation2016, p. 4). This remains to be seen. But the reports promoting cohousing as an instrument of regional development exemplify how central government increasingly expects municipalities to be ‘entrepreneurial’ and ‘competitive’ in addressing development problems (Carter, Citation2011). This entails risks as well as opportunities. In the more general assessment of Arbell (Citation2016, p. 563):

The risk of empowering local groups to develop their own housing is that the neoliberal state will withdraw its responsibility to welfare and expect the most vulnerable to show entrepreneurialism and solve their housing problems with their limited means. If groups could maintain their free engagement in self-governance with the aid of locally tailored planning, this would be a fantastic use of local authorities’ resources and expertise.

Second, there are suggestions that the motivations for living in cohousing have changed. In the words of one recent report, cohousing communities (and communes) of the 1970s ‘were in many ways ideological experiments, which sought to challenge the norms and values of established society and to explore new gender roles and family forms’ (Dansk Bygningsarv, Citation2016, p. 15). In contrast, the report suggests that contemporary cohousing is

a sort of practical ‘lifebelt’ for the modern human and an attempt to recreate the meaningful social relations that are no longer automatically provided by the nuclear family one no longer is part of, or have been lost in the modern society in which we no longer know our neighbours. (Dansk Bygningsarv, Citation2016, p. 15)

This does not imply that cohousing today is ‘devoid of social idealism’, the report adds, because ideals of economic and environmental sustainability are widespread, and social sustainability is ‘embedded in the social-practical communities of cohousing and has provided this housing form with a new immediacy’ (Dansk Bygningsarv, Citation2016, p. 15). While it is beyond the scope of this article to analyse shifting motivations for choosing cohousing, it could be argued that the renewed interest in cohousing in large part is driven by pragmatic considerations about how to cope with the individual and social challenges of modern life rather than desires to explore (radical) alternatives. As Sandstedt & Westin (Citation2015, p. 145) argue in relation to Swedish cohousing, Danish cohousing life could probably also be seen as ‘a distinct late-modern phenomenon’ that unfolds in the interstices between received notions of Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft. Still, Sargisson (Citation2012, p. 45, 49) proposes in relation to the United States that cohousing may be ‘a pragmatic utopian phenomenon’ in which members ‘become virtuous property-owning citizens.’

This point could also be valid in the Danish context, as new cohousing communities of the third phase are overwhelmingly based on owner occupation. This has not arrested the diffusion of cohousing. But owner-occupation is exclusionary, and in Denmark as elsewhere, social inequalities and socio-geographical segregation are increasingly tied to ownership of housing (Olsen et al., Citation2014). That this is also the case for cohousing is suggested by a recent analysis, which shows that contemporarary cohousing residents are significantly above the Danish average in socio-economic status and level of education. This is most pronounced in owner-occupied cohousing, but residents in communities based on cooperative tenure are also noticably above the Danish average (Jakobsen & Larsen, Citation2018). It has been debated whether cohousing is a variant of arguably the most manifest form of housing segregation, gated communities (Chiodelli, Citation2015; Chiodelli & Baglione, Citation2014; Ruiu, Citation2014). This is a valid debate, but little suggests that Danish cohousing in a foreseeable future will become gated communities in a literal sense. Rather, the more likely risk is that cohousing communities become (if not remain) enclaves for the privileged. The greatest potential for affordable cohousing today lies in the sector of non-profit public housing, because apart from not having to take out a mortgage or purchase a share, as in owner-occupied housing or housing cooperatives, residents in public housing can also receive public housing benefits.

There are some cohousing communities that are based on public housing tenure or a mix of this and other tenure forms. But in terms of the number of communities, intergenerational cohousing in rental public housing is still limited (). In significant part, this relates to a historical ‘inflexibility’ of the public housing sector. But public housing tenure has become widespread in senior cohousing (Pedersen, Citation2015), and there have been developments in the public housing sector which, in relation to intergenerational cohousing, could also facilitate the direct involvement sought by many would-be cohousing residents. First, although still in many ways restricted by legislation, the sector has in recent years begun to experiment with housing types that give residents a greater say in the design and running of their housing, for example ‘AlmenBolig+’ (Jensen & Stensgaard, Citation2016). Second, this could feed into a participatory democracy with significant decision-making for public housing residents, which, albeit with tensions and problems, has been introduced since the 1970s (Hansen & Langergaard, Citation2017). At the time when state support for new-build housing cooperatives was introduced, Andersen & Lyager (Citation1984) saw this tenure form as an advantages for the spread of cohousing, and yet they conclude that the greatest potentials for cohousing is in the public housing sector. If the aim is to deflect the strong socio-economic biases that come with owner occupation, this still seems to be the case.

Conclusions

In his pioneering feature article, Gudmand-Høyer (Citation1968) outlined cohousing as a link between ‘utopia’ and the ‘outdated single-family house’. Such claims are not new, of course:

For centuries, architects and utopians have pursued the idea that housing can provide the basis for a humane society. Such projects return again and again to the same themes: decommodification, collective amenities, social spaces, democratic self-government, and engagement with the political and cultural life of residents. (Madden & Marcuse, Citation2016, p. 114)

To a noticeable degree, Danish cohousing communities have been successful in realizing such ideas. Residents find that this housing form positively influence their life satisfaction (Jakobsen & Larsen, Citation2018), and for close to five decades cohousing has spurred thriving and varied communities. While still a modest element in Danish housing, it attests to the vitality of cohousing that established communities flourish and that new ones are continuously being created (). Yet, although rarely a central concern of its proponents, Danish cohousing has generally been unsuccessful in de-commodifying housing.

From the outset, during the first phase of Danish cohousing in the 1970s, owner occupation was the only readily available model for most cohousing communities. The non-profit public housing sector played a role, but this sector and proponents of cohousing never got together to any significant extent. This considerably reduced access to cohousing. To a degree, this situation changed during the second phase when in 1981 it became possible to build cohousing based on cooperative tenure with state support. Much suggests that this helped the cohousing idea to thrive and expand into the 1980s, and that cooperative tenure made cohousing an accessible housing alternative for a wider group. Cooperative tenure is not a panacea, but particularly in light of the mounting lack of affordable housing in Europe and elsewhere, the diversifying effect of cooperative tenure in Danish cohousing should be noted. Largely due to wider housing-political changes, this option was finally removed in 2004. Since then, in the third phase, new (intergenerational) cohousing communities have again been dominated by owner-occupation – and the socio-economic biases that follows this tenure. Delgado (Citation2012, p. 431) perceptively suggests that the term ‘housing alternative’ must ‘assert that the housing in question is in some way divergent from the current production of housing’. Leaning on Harvey (Citation2000), Delgado further suggests that collaborative housing alternatives, like cohousing, can be located in a continuum between ‘utopias of built form’ and ‘utopias of social process’. At the local scale of individual communities, Danish cohousing has advanced alternatives in both these respects. But on a wider scale, Danish cohousing has not provided significant alternatives to the ‘ownership model’, which ‘identifies property as essentially private, with state property as the anomalous exception’ (Blomley, Citation2004, p. xix). With its institutionalization of collective property, the Danish form of cooperative tenure could question this. But in the history of Danish cohousing, it is suggestive that cooperative tenure only had a significant impact in the period when the state – for reasons that had no relation to cohousing – supported the tenure financially. In the Danish context, a more actual de-commodification of cohousing – and with that a greater accessibility for lower-income groups – would require a stronger role of public rental tenure.

As Jarvis (Citation2015, p. 95) points out, ‘it is important to recognize that the underlying concept [of cohousing] is essentially socio-spatial rather than specifying a particular legal and financial model of land purchase or construction’. This is an important point, and researchers have in recent years made headway in our understanding of socio-spatial dimensions of cohousing and related housing alternatives. But questions of tenure have mostly been neglected. This is unfortunate, because as Danish history reveals, tenure forms can facilitate as well as obstruct the realization of cohousing ideas and have implications for who can access this housing form. Based on data from the United States, for example, Boyer & Leland (Citation2018, p. 654) suggest that ‘the slow diffusion of cohousing is likely the consequence of inaccessibility (rather than low appeal).’ More widely, Czischke (Citation2018, p. 58) identifies affordability and social inclusion as driving forces for the renewed interest in housing alternatives, which ‘marks a departure from the often “middle-class” character attributed to these initiatives in the past, most notably co-housing projects’. Tenure is only one aspect of accessibility and social inclusion. It is an important one, however, and tenure forms must be accorded greater attention if cohousing is to develop into a wider and more accessible housing alternative. That said, tenure is only a simple shorthand for property relations, and there are deeper questions to be pursued in what Blomley (Citation2016a, p. 225) terms ‘property’s lived world’. This could address questions such as how property relations are worked out when establishing cohousing communities, what those relations imply for the lived experience in these communities and what kind of social and geographical boundary practices are imposed by property. In any case, ‘there are real costs in forgetting property, for property has not forgotten us’ (Blomley, Citation2005, p. 127).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Henrik Gutzon Larsen

Henrik Gutzon Larsen teaches Human Geography at Lund University. His research addresses urban geography and housing, political geography and history of geographical thought.

Notes

1 In this article, ‘established’ indicates the year the first members of a cohousing community took up residence. The group behind the community is generally several years older. This can cause some confusion – or even debate. In a critical reply to Andersen & Lyager (Citation1984), for example, Gudmand-Høyer (1984a) challenges the assertion that Sættedammen was be the first Danish cohousing community, presumably because the founding of his own community (Skråplanet) has a longer history.

2 Reich and Prins use ‘boplads’ for what is translated here as ‘settlement’. In Danish, ‘boplads’ has a distinctly primordial resonance that harks further back than even the (pre-modern) village – a recurring image in writings on cohousing (e.g. Lietaert, Citation2010; McCamant & Durrett, Citation2011). Madsen (Citation1981) later uses ‘boplads’ as heading for an article arguing for diversity in alternative housing, including cohousing.

3 The often-forgotten exception is Toustrup Mark (est. 1971), which, apart from arguably being the first established Danish cohousing community, is notable for being based on cooperative tenure – ten years before this became the norm for new cohousing communities (El-Tanany & Flamsholt Christensen, 2011; Nygaard, Citation1984).

4 This tenure is sometimes translated as ‘social housing’. In part, the sector functions as social housing. However, as access to rental housing in non-profit housing associations is not regulated by means testing, public housing is a better translation. Literally, but also reflecting the ideational foundations of the sector, ‘almen bolig’ could be translated as ‘common housing’ (see, for example, Vidal, 2018).

References

- Ådalen 85. (n.d.) Der var engang. Available at www.aadalen85.com/historie (accessed 26 March 2018).

- Andersen, H. S. (1985) Danish low-rise housing co-operatives (bofællesskaber) as an example of a local community organization. Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research, 2(2), pp. 49–66.

- Andersen, H. S. & Lyager, P. (1984) Tæt-lave bofællesskaber – erfaringer, problemer og perspektiver [Dense-low cohousing – experiences, problems and perspectives]. Arkitekten, 86(4), pp. 78–81.

- Andersen, H. T. (2006) Andelsboligen – fremtidens boligtype? [The cooperative dwelling – the housing type of the future?], in: ATV Temagruppe for Byggeri og Bystruktur (Ed) Den gode bolig – hvor skal vi bo i fremtiden?, pp. 27–29 (Lyngby: Akademiet for de Tekniske Videnskaber).

- Andersen, H. T. & Winther, L. (2010) Crisis in the resurgent city? The rise of Copenhagen. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 34(3), pp. 693–700.

- Aner, L. G. (2016) Dwelling habitus and urban out-migration in Denmark. European Urban and Regional Studies, 23(4), pp. 662–676.

- Anonymous. (1971) Kan dit barn heller ikke klare alm. skole? [Is your child also unable to follow normal school?], Dagbladet Information, November 15, p. 5.

- Arbell, Y. (2016) Review of ‘The re-emergence of cohousing in Europe’. International Journal of Housing Policy, 16(4), pp. 561–564.

- Barlow, J. & Duncan, S. (1988) The use and abuse of tenure. Housing Studies, 3(4), pp. 219–231.

- Bendixen, E. L., Dilling, L., Holten, C., Illeris, S., Illeris, G., Bjerre, B. & Rasmussen, B. (1997) Sættedammen i 25 år [Sættedammen for 25 years] (Hillerød: Sættedammen).

- Bjerre, L. & Sørensen, E. M. (1984) Bofællesskabernes folkevogn [The cohousing communities’ Volkswagen]. Blød By, no. 29, pp. 41–43.

- Bjerre, P. (1997) Bofællesskab og oprør? [Cohousing and rebellion?], in: E. L. Bendixen, L. Dilling, C. Holten, S. Illeris, G. Illeris, B. Bjerre & B. Rasmussen (Eds) Sættedammen i 25 år, pp. 68–70 (Hillerød: Sættedammen).

- Blandy, S. (2013) Collective property: owning and sharing residential space, in: N. Hopkins (Ed) Modern Studies in Property Law: Vol. 7, pp. 151–172 (Oxford: Hart Publications).

- Blomley, N. (2004) Unsettling the City: Urban Land and the Politics of Property (Abingdon: Routledge).

- Blomley, N. (2005) Remember property? Progress in Human Geography, 29(2), pp. 125–127.

- Blomley, N. (2016a) The boundaries of property: complexity, relationality, and spatiality. Law & Society Review, 50(1), pp. 224–255.

- Blomley, N. (2016b) The territory of property. Progress in Human Geography, 40(5), pp. 593–609.

- Boligministeriet (1992) Bofællesskaber: Rapport afgivet den 28. februar 1992 af arbejdsgruppen om bofællesskaber [Cohousing communities: Report submitted 28 February 1992 by the task force on cohousing] (Copenhagen: Boligministeriet).

- Boyer, R. H. & Leland, S. (2018) Cohousing for whom? Survey evidence to support the diffusion of socially and spatially integrated housing in the United States. Housing Policy Debate, 28(5), pp. 653–667.

- Bruun, M. H. (2011) Egalitarianism and community in Danish housing cooperatives. Social Anlysis, 55(2), pp. 62–83.

- Bruun, M. H. (2018) The financialization of Danish cooperatives and the debasement of a collective housing good. Critique of Anthropology, 38(2), pp. 140–155.

- Brydensholt, H. H. (1984) Magt gennem dagligdags fællesskab [Power through everyday community], Dagbladet Information, March 13, p. 5.

- Buus, M., Knudsen, P. Ø., Poulsen, O., Skipper, F. & Sørensen, S. (2010) Thylejren (Thisted: Museet for Thy og Vester Hanherred).

- Byggeriets Udviklingsråd (1982) Bofællesskabet Sol og Vind [The cohousing community Sol og Vind] (Copenhagen: Byggeriets Udviklingsråd).

- Byggeriets Udviklingsråd (1983) Veje til bofællesskab [Ways to cohousing] (Copenhagen: Byggeriets Udviklingsråd).

- Caldenby, C. & Walldén, Å. (1984) Kollektivhuset Stacken [The collective house Stacken] (Gothenburg: Korpen).

- Carter, H. (2011) Compelled to Compete? Competitiveness and the Small City (Aalborg: Department of Development and Planning, Aalborg University).

- Carter, H., Larsen, H. G. & Olesen, K. (2015) A planning palimpsest: neoliberal planning in a welfare state tradition. European Journal of Spatial Development, no. 58, pp. 1–20.

- Chatterton, P. (2015) Low Impact Living: A Field Guide to Ecological, Affordable Community Building (Abingdon: Routledge).

- Chiodelli, F. (2015) What is really different between cohousing and gated communities? European Planning Studies, 23(12), pp. 2566–2581.

- Chiodelli, F. & Baglione, V. (2014) Living together privately: for a cautious reading of cohousing. Urban Research & Practice, 7(1), pp. 20–34.

- Christensen, S. K. & Kristensen, T. S. (1972) Kollektiver i Danmark [Communes in Denmark] (Copenhagen: Borgen/Basis).

- Clapham, D. (2018) Remaking Housing: An International Study (Abingdon: Routledge).

- Clark, E. & Lund, A. (2000) Globalization of a commercial property market: the case of Copenhagen. Geoforum, 31(4), pp. 467–475.

- Cox, R. W. (1994) The crisis in world order and the challenge to international organization. Cooperation and Conflict, 29(2), pp. 99–113.

- Czischke, D. (2018) Collaborative housing and housing providers: towards an analytical framework of multi-stakeholder collaboration in housing co-production. International Journal of Housing Policy, 18(1), pp. 55–81.

- Daly, M. (2015). Practicing sustainability: Lessons from a sustainable cohousing community. Paper presented at the State of Australian Cities Conference 2015, Gold Coast, Queensland.

- Dansk Bygningsarv (2016) Fremtidens bofællesskaber [Cohousing communities of the future] (Copenhagen: Udlaendinge-, Integrations- og Boligministeriet).

- Delgado, G. (2012) Towards dialectic utopias: links and disjunctions between collaborative housing and squatting in the Netherlands. Built Environment, 39(2), pp. 430–442.

- Dirckinck-Holmfeld, K. (1984) Moderne fællesskab [Modern community]. Arkitektur, 28(6), pp. 209.

- Egerö, B. (2014) Puzzling patterns of co-housing in Scandinavia. Available at http://kollektivhus.nu (accessed 30 September 2016).

- El-Tanany, R. A. A. & Flamsholt Christensen, J. (2011) Drømmen lever – 40 år i kollektivlandsbyen Toustrup Mark [The dream lives – 40 years in the collective village Toustrup Mark] (Odense: Kle-art).

- Erhvervs- og Byggestyrelsen. (2006) Analyse af andelsboligsektorens rolle på boligmarkedet [Analysis of the cooperative sector’s role in the housing market] (Copenhagen: Erhvervs- og Byggestyrelsen).

- Erhvervsministeriet. (1980) Cirkulære om offentlig støtte til opfaerelse og drift af andelsboliger. Available at https://www.retsinformation.dk/print.aspx?id=83515.

- Gaardmand, A. (1984) Udnyt lokalsamfundets mange kræfter [Utilize the many strengths of local communities]. Dagbladet Information, 6 March, p. 6.

- Garciano, J. L. (2011) Affordable cohousing: challenges and opportunities for supportive relational networks in mixed-income housing. Journal of Affordable Housing, 20(2), pp. 169–192.

- Graae, B. (1967) Børn skal have hundrede forældre [Children should have a hundred parents], Politiken, 9 April, pp. 49–50.

- Graae, B. (1969) Den store familje [The big family]. Politiken, 16 March, pp. 49–50.

- Gudmand-Høyer, J. (1968) Det manglende led mellem utopi og det forældede enfamiliehus [The missing link between utopia and the outdated single-family house]. Dagbladet Information, 26 June, p. 3.

- Gudmand-Høyer, J. (1984a) Brugerkonsulent og bofællesskaber [User-consultant and cohousing]. Arkitekten, 86(7), pp. 147–148.

- Gudmand-Høyer, J. (1984b) Ikke kun huse for folk – også huse af folk [Not only houses for people – also houses of people]. Dagbladet Information, 4 April, p. 7.

- Hansen, A. V. & Langergaard, L. L. (2017) Democracy and non-profit housing. The tensions of residents’ involvement in the Danish non-profit sector. Housing Studies, 32(8), pp. 1085–1104.

- Hansen, J. W. (1979) Sættedammen – 60’ernes sociale opbrud og kollektiverne [Sættedammen – social upheavals of the 60s and the communes]. Blød By, no. 3, pp. 54–55.

- Hansen, J. W. (1984a) Den nye type: Tæt-lav bofællesskaberne i Danmark [The new model: dense-low cohousing in Denmark]. Arkitektur, 28(6), pp. 239–247.

- Hansen, J. W. (1984b) Made in Denmark: De danske bofællesskaber [Made in Denmark: The Danish cohousing communities]. Blød By, no. 31, pp. 15–19.

- Harvey, D. (2000) Spaces of Hope (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press).

- Hertha (2016) Hertha Living Community – social and cultural value creation in a village of the future. Available at http://hertha.dk (accessed 3 January 2017).

- Illeris, S. (2018) Fællesskab, forskning og landsplanlægning: Sven Illeris’ erindringer [Community, research and spatial planning: Sven Illeri’s memories] (Copenhagen: Forlaget Underskoven).

- Jakobsen, P. & Larsen, H. G. (2018) An alternative for whom? The evolution and socio-economy of Danish cohousing. Urban Research & Practice, doi: 10.1080/17535069.2018.1465582.

- Jantzen, E. B. & Kaaris, H. (1984) Danish low-rise housing. Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research, 1(1), pp. 27–42.

- Jarvad, P. (1999) Nye Ord: Ordbog over nye ord i dansk 1955–98 [New words: Dictionary of new words in Danish 1955–98] (Copenhagen: Gyldendal).

- Jarvis, H. (2011) Saving space, sharing time: integrated infrastructures of daily life in cohousing. Environment and Planning A, 43(3), pp. 560–577.

- Jarvis, H. (2015) Towards a deeper understanding of the social architecture of co-housing: evidence from the UK, USA and Australia. Urban Research & Practice, 8(1), pp. 93–105.

- Jarvis, H. & Bonnett, A. (2013) Progressive nostalgia in novel living arrangements: a counterpoint to neo-traditional new urbanism? Urban Studies, 50(11), pp. 2349–2370.

- Jensen, J. O. & Stensgaard, A. G. (2016) Evaluering af AlmenBolig+ [Evaluation of AlmenBolig+] (Copenhagen: Danish Building Research Institute).

- Jensen, M. K., Kirkegaard, O. & Varming, M. (1997) Sociale boformer: Boformer for psykisk syge, alkohol- og stofmisbrugere samt socialt udstødte og hjemløse [Social housing forms: Housing forms for the mentally ill, alcohol- and drug-addicted as well as outcasts and homeless] (Hørsholm: Statens Byggeforskningsinstitut).

- Johnsen, M. S. (1981) Hvem taler om arkitektoniske behov? Kan boligfællesskaberne vise vejen? [Who is talking about architectural needs? Can the cohousing communities show the way?]. Blød By, no. 13, pp. 38–43.

- Jonasson, K. (2010) Tilbudspligt [First refusal], in: M. Dürr, T. L. Witte & K. Jonasson (Eds) Administration af boliglejemål: Bind 2, pp. 1149–1175 (Copenhagen: Ejendomsforeningen Danmark/Schultz Information).

- Kjeldsen, J. (1984) Man kan ikke bo sig til et andet samfund [One cannot house oneself to another society], Dagbladet Information, 1 May, p. 6.

- Kløvedal, H. J. (1981) Hvad var det nu vi ville? Et rasende indlæg i jubilæumsdebatten [What was it we wanted? A furious contribution to the jubilee debate]. Blød By, no. 13, pp. 16–21.

- Kristensen, H. (2007) Housing in Denmark (Copenhagen: Centre for Housing and Welfare).

- Lang, R., Carriou, C. & Czischke, D. (2018) Collaborative housing research (1990-2017): a systematic review and thematic analysis of the field. Housing, Theory and Society, doi: 10.1080/14036096.2018.1536077.

- Lang, R. & Stoeger, H. (2018) The role of the local institutional context in understanding collaborative housing models: empirical evidence from Austria. International Journal of Housing Policy, 18(1), pp. 35–54.

- Langkilde, H. E. (1970) Kollektivhuset – en boligforms udvikling i dansk arkitektur [The collective house – the development of a housing form in Danish architecture] (Copenhagen: Dansk Videnskabs Forlag).

- Larsen, H. G. & Lund Hansen, A. (2015) Commodifying Danish housing commons. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 97(3), pp. 263–274.

- Lietaert, M. (2010) Cohousing’s relevance to degrowth theories. Journal of Cleaner Production, 18(6), pp. 576–580.

- Lund, N.-O. (1981) Den onde by og det gode land [The evil city and the good countryside]. Blød By, no. 13, pp. 35–37.

- Madden, D. & Marcuse, P. (2016) In Defense of Housing: The Politics of Crisis (London: Verso).

- Madsen, B. (1981) En boplads [A settlement]. Blød By, no. 14, pp. 43–44.

- Marckmann, B., Gram-Hanssen, K. & Christensen, T. H. (2012) Sustainable living and co-housing: evidence from a case study of eco-villages. Built Environment, 38(3), pp. 413–429.

- McCamant, K. & Durrett, C. (1988) Cohousing: A Contemporary Approach to Housing Ourselves (Berkeley: Habitat Press).

- McCamant, K. & Durrett, C. (2011) Creating Cohousing: Building Sustainable Communities (Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers).

- Meltzer, G. (2005) Sustainable Community: Learning from the Cohousing Model (Victoria, BC: Trafford Press).

- Meyer, N. I., Helveg Petersen, K. & Sørensen, V. (1978) Oprør fra midten [Revolt from the centre] (Copenhagen: Gyldendal).

- Meyer, N. I., Helveg Petersen, K. & Sørensen, V. (1981) Revolt from the Center (London: Boyars).

- Meyhoff, P. (1984) Den man elsker tugter man [Spare the rod and spoil the child], Dagbladet Information, 20 March, p. 5.

- Mogensen, D. (1981) Tæt-lav-strømningen går mod højre [The low-dense trend swings to the right]. Blød By, no. 13, pp. 46–49.

- Montaner, J. M. (2016) ‘Covivienda’ en Barcelona [‘Cohousing’ in Barcelona], El Periódico de Catalunya, 19 December.

- Mullins, D. (2018) Achieving policy recognition for community-based housing solutions: the case of self-help housing in England. International Journal of Housing Policy. 18(1), pp. 143–155.

- Navne, A.-D. (1987) At bo i fællesskab: En bog om kollektiver og bofællesskaber [To live in community: a book on communes and cohousing communities] (Copenhagen: Arkitektes Forlag).

- Nygaard, E. (1984) Tag over hovedet: Dansk boliggyggeri fra 1945 til 1982 [Roof over head: Danish housing from 1945 to 1982] (Copenhagen: Arkitektens Forlag).

- Olsen, L., Ploug, N., Andersen, L., Sabiers, S. E. & Andersen, J. G. (2014) Klassekamp fra oven: Den danske model under pres [Class struggle from above: the Danish model under pressure] (Copenhagen: Gyldendal).

- Ove R. Drevet (1982) Overdrevet: Et bofællesskab [Overdrevet: A cohousing community] (Meilgaard: Forlaget Skippershoved).

- Ove R. Drevet (2005) Spiser I virkelig sammen hver dag? Et bofællesskab i 25 år [Do you really eat together every day? A cohousing community for 25 years] (Hinnerup: Bofællesskabet Overdrevet/SøftenDal).

- Pedersen, M. (2013) Det store eksperiment: Hverdagsliv i seniorbofællesskaber [The big experiment: Everyday life in senior cohousing communities] (Copenhagen: Statens Byggeforskningsinstitut).

- Pedersen, M. (2015) Senior co-housing communities in Denmark. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 29(1–2), pp. 126–145.

- Petersen, H. (1984) Det store parcelhus [The big detached house], Dagbladet Information, 27 March, p. 9.

- Petersen, J. H., Petersen, K. & Christiansen, N. F. (Eds) (2012) Dansk velfærdshistorie, bind 4: 1956-1973 [Danish welfare history, volume 4: 1956–1973] (Odense: Syddansk Universitetsforlag).

- Petersen, J. H., Petersen, K. & Christiansen, N. F. (Eds) (2013) Dansk velfærdshistorie, bind 5: 1973-1993 [Danish welfare history, volume 5: 1973–1993] (Odense: Syddansk Universitetsforlag).

- Rasmussen, D. (2017) Kollektiver og bevægelser på Langeland: 1970’erne og 1980’erne [Communes and movements on Langeland: the 1970s and 1980s] (Rudkøbing: Langelands Museum).

- Reich, E. K. & Bjerre, P. (1984) Fællesskabets ubrugte kræfter [The unexploited strengths of community], Dagbladet Information, 28 February, p. 5.

- Reich, E. K. & Prins, H. K. (1977) Langelands-manifestet – en skitse til Danmark [The Langeland Manifesto – an outline for Denmark] (second ed.) (Copenhagen: Imladris).

- Retsinformation (2016) Vejledning om kollektive bofællesskaber i almene familieboliger. Available at https://www.retsinformation.dk/Forms/R0710.aspx?id=180116.

- Ruiu, M. L. (2014) Differences between cohousing and gated communities: a literature review. Sociological Inquiry, 84(2), pp. 316–335.

- Ruonavaara, H. (1993) Types and forms of housing tenure: towards solving the comparison/translation problem. Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research, 10(1), pp. 3–20.

- Sandstedt, E. & Westin, S. (2015) Beyond Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft: cohousing life in contemporary Sweden. Housing, Theory and Society, 32(2), pp. 131–150.

- Sargisson, L. (2012) Second-wave cohousing: a modern utopia? Utopian Studies, 23(1), pp. 28–56.

- Scheller, D. & Thörn, H. (2018) Governing ‘sustainable urban development’ through self-build groups and cohousing: the cases of Hamburg and Gothenburg. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 42(5), pp. 914–933.

- Schultz, M. (1984) Drømmen om et nyt samfund: alternative samfundseksperimenter i 70’ernes Danmark [The dream about a new society: alternative social experiments in Denmark in the 70s] (Nimtofte: Forlaget Indtryk).

- Second City (2016) Fire byer på jagt efter nye fællesskaber [Four cities seeking new communities] (Copenhagen: Udlændinge-, Integrations- og Boligministeriet).

- Sørvoll, J. & Bengtsson, B. (2018) The Pyrrhic victory of civil society housing? Co-operative housing in Sweden and Norway. International Journal of Housing Policy, 18(1), pp. 124–142.

- Statens Byggeforskningsinstitut. (1972) Tæt lav – en boligform [Dense-low – a housing model] (Copenhagen: Statens Byggeforskningsinstitut).

- Stensgaard, P. (2016) Den nye guldgrube [The new gold mine], Weekendavisen, 15 April, p. 4.

- Thörn, H., Wasshede, C. & Nilson, T. (Eds) (2011) Space for Urban Alternatives? Christiania 1971-2011 (Möklinta: Gidlunds förlag).

- Tornow, B. (2015) Dänemark, Pionierland für Cohousing/Denmark, pioneer country for cohousing, in: wohnbund E.V. (Ed) Europa: Gemeinsam Wohnen/Europe: Co-operative Housing, pp. 80–91 (Berlin: jovis Verlag GmbH).

- Tummers, L. (2015) Understanding co-housing from a planning perspective: why and how? Urban Research & Practice, 8(1), pp. 64–78.

- Tummers, L. (2016a) The re-emergence of self-managed co-housing in Europe: a critical review of co-housing research. Urban Studies, 53(10), pp. 2023–2040.

- Tummers, L. (Ed) (2016b) The Re-Emergence of Cohousing in Europe (Abingdon: Routledge).