?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Homeownership levels among young adults in the UK are declining. This paper compares youth transitions to homeownership in Scotland during the 1990s and 2000s by examining the roles of both personal and parental socio-economic characteristics and local house prices. It demonstrates demographic diversity among young people, with gender and partnership status interacting to shape their transitions to homeownership. The findings reveal that, although single women are less likely than single men to become homeowners, women are more likely to make the transition if they live with a partner. For all young adults, patterns of advantage and disadvantage are defined by personal resources and parental background. While many of these inequalities have persisted over time, the distance between the most and least advantaged has widened, new inequalities have emerged and local housing markets have come to play a greater role for some.

Introduction

Changing transitions to adulthood have been the subject of recent demographic research focussing on Europe (see, amongst others, Gauthier, Citation2007 and Billari & Liefbroer, Citation2010 ), which has highlighted how youth pathways have shifted from being ‘early, contracted, and simple’ to ‘late, protracted and complex’ (Billari & Liefbroer, Citation2010, p. 60). Leaving the parental home continues to mark a crucial moment in young people’s entry into adulthood, and homeownership remains a desirable goal. However, the increasing diversification of young adults’ life courses has seen more young adults staying in the parental home for longer, the postponement of family formation, and delayed access to homeownership (Beer & Faulkner, Citation2011). For some, indeed, the purchase of a home is either not desired or is never achieved. This paper explores such life course diversity by investigating how gender and partnership status shape young adults’ housing transitions in Scotland, and asks whether new inequalities in access to homeownership have emerged in the early twenty-first century.

The recent economic recession in the UK has accentuated economic uncertainty, and in combination with rising housing prices and tighter lending requirements, has contributed to the more prolonged presence of young adults in their parental home and the increasing difficulties they face getting onto the housing ladder. Declining rates of homeownership among younger adults have been observed throughout Europe, including in the UK where homeownership has been the dominant tenure of choice at least since the 1980s (McKee, Citation2012; Ronald, Citation2008). A substantial body of social research within the British context has now turned its attention to young adults’ housing transitions and the factors influencing them (Clapham et al., Citation2014; Coulter, Citation2016a, Citation2016b; Hoolachan et al., Citation2017; Sissons & Houston, Citation2018). Of particular interest is whether homeownership is generally becoming less accessible for all young adults, or whether only some population groups have become increasingly disadvantaged.

This paper contributes to the ongoing debate by investigating transitions to homeownership among young adults in the distinctive housing context of Scotland (McKee et al., Citation2017) in the first decade of the 2000s. We then compare the results with those for the previous decade in order to identify persisting and/or emerging drivers of inequality. We draw on recent theorizations of housing transitions over the life course (Beer & Faulkner, Citation2011), which recognize the fluidity and growing complexity of young adulthood and the consequent diversity of housing pathways among young people. We argue that it is important to consider demographic diversity as this may reflect different life choices and opportunities, which in turn shape housing pathways. We therefore examine the transition to homeownership of four population groups: young men and young women either living as single or with a partner. The life-course perspective (Elder et al., Citation2003) also emphasizes the importance of linked lives and interdependencies, thus suggesting that young adults’ biographies and housing transitions result from interactions in multiple life domains, and are connected with the lives of other people in their household and the wider family, as well as being shaped by contextual conditions and historical events. This study acknowledges linked lives by recognizing the growing importance of parental resources for securing homeownership (Coulter, Citation2016a, Citation2016b; Druta & Ronald, Citation2016; Heath & Calvert, Citation2013), and explores the role played by young adults’ parental, as well as personal, socio-economic characteristics, in shaping transitions to homeownership. It also recognizes that young adults’ ease of access to homeownership may vary geographically, depending on the features of local housing markets.

The study further extends the scope of existing work on Britain by focusing on Scotland, where responsibility for housing is devolved to the Scottish Government. As McKee et al. (Citation2017) pointed out, there is no such thing as a UK housing context due to differences in policy and political narratives across the UK. Historically, and unlike the rest of the UK, social housing was the dominant tenure in Scotland. According to data from Scotland’s census, over half of households were living in the social rented sector in 1981. Since the 1980s, however, the share of social rented housing has fallen while that of owner-occupied housing has grown significantly, mainly as a result of new legislation that allowed social housing tenants to purchase their homes (the Right to Buy scheme1), along with low levels of new build social housing. With the Right to Buy legislation, the UK government sought to encourage homeownership, which became the main type of housing tenure in Scotland for the first time in 1988, and the private sector responded with more than 20 thousand new build units per year – mainly for sale, but also for rent (Graham et al., Citation2017).

In the 1990s and the early 2000s, demand for privately owned housing exceeded supply, fuelling substantial increases in house prices. While the former decade was marked by steady increases, between 2001 and the global financial crisis of 2007/08 average house prices in Scotland more than doubled – particularly in the East of Scotland around Edinburgh and Aberdeen (Graham et al., Citation2017), as did the ratio of average house price to income for those aged 25–34 (Cribb et al., Citation2018). One consequence has been a decline in homeownership rates – particularly among young adults. According to data from Scotland’s census, half of the households where the head of household was aged under 34 were living in owned accommodation in 2001, but the proportion fell to just above one third in 2011 (General Register Office for Scotland, Citation2003; National Records of Scotland, Citation2013). This raises questions about who did, and who did not, make the transition to owner-occupation in the 2000s, and who was newly disadvantaged compared with the decade before.

Demographic diversity and transitions to homeownership

Gender and partnership are two major dimensions of demographic diversity. Numerous studies highlight gender differences in the process of leaving home. Not only do young women typically leave home earlier than men (Chiuri & Del Boca, Citation2010; Corjin & Klijzing, Citation2001), they also do so more often to form a family with an (older) partner (Billari & Liefbroer, Citation2007). Men, on the other hand, leave at relatively older ages, and they do it more often alone and for work reasons. Although these differences may not be as pronounced as they once were (Furstenberg, Citation2010; Iacovou, Citation2010), gender remains an important dimension of diversity.

Gender differences are also observed in the role played by young adults’ socio-economic characteristics (Iacovou, Citation2010), as well as in the influence of parental resources or characteristics of the family of origin (Blaauboer & Mulder, Citation2010; Buck & Scott, Citation1993; Goldscheider & Goldscheider, Citation1999; Mulder & Hooimeijer, Citation2002). In part, these differences relate to different pathways out of the parental home for men and women. Personal income, for instance, has been found to be more important for partnered men than for partnered women (Iacovou, Citation2010; Whittington & Peters, Citation1996), suggesting gendered expectations about family roles. In contrast, research has shown that the influence of the family of origin is generally more important for women than for men, although this varies depending on whether or not young adults leave their parents’ home to live with a partner (Blaauboer & Mulder, Citation2010; Iacovou, Citation2010; Mitchell, Citation2004; Mulder & Smits, Citation2013; Rusconi, Citation2004).

It is therefore surprising that housing research – in spite of recognizing the link between the family life course and housing (Mulder, Citation2013) – has devoted little attention to how gender and partnership status interact with other factors in shaping young adults’ transitions to homeownership. To our knowledge, the only exception is a study by Blaauboer (Citation2010) which investigated the role of family background and personal resources on the homeownership of couples and singles in the Netherlands. Her study showed that there is a difference between men and women in couples, as well as between men and women without partners, in the level of homeownership and in its determinants. Her work provided valuable insights but it included respondents up to age 65 rather than focusing exclusively on young adults. More recently, a comparative study of Germany, the Netherlands and the UK by Thomas and Mulder (Citation2016) on young adults aged 25–40 confirmed a hierarchy in homeownership according to partnership status. Greater propensities to own a home were observed among couple households compared to single-person households, with dual-earner households being most likely to achieve homeownership. However, the study did not investigate whether the importance of other factors associated with homeownership varies by gender and partnership status nor whether inequalities in homeownership have increased over time.

Our study aims to address this research gap by exploring the diversity of young adults’ transitions to homeownership by gender and partnership in order to highlight differences in their propensity to become homeowners. Acknowledging the largely overlooked role of demographic diversity in shaping housing pathways, we extend the scope of previous empirical studies by looking explicitly at whether and how gender and partnership status define the transition to homeownership among young nest-leavers in Scotland, as well as interact with the factors enabling or hindering such a transition. Our first research question therefore asks:

RQ1: Do young adults’ transitions to homeownership vary by gender and partnership?

Since demographic diversity may reflect life choices rather than inequalities of access, our second aim is to determine which groups in the young adult population continue to be disadvantaged and whether new dimensions of disadvantage have emerged in the twenty-first century.

Drivers of inequality in transitions to homeownership

Previous research on young adults’ housing transitions has shown that economic independence and the availability of a sufficient income are often regarded as important pre-requisites both for the departure from the parental home and the entry into homeownership (Aassve et al., Citation2002, Citation2013; Iacovou, Citation2010; Lersch & Dewilde, Citation2015). As market earnings represent the major source of income for most young adults, a secure and established job with good remuneration is needed in order to save for a sizeable deposit and to cover mortgage payments and maintenance costs associated with homeownership. Further, young adults in insecure employment experience higher residential mobility for occupational reasons, and are therefore likely to postpone home purchase until they have ‘settled down’ (Coulson & Fisher, Citation2009). Investments in education are seen as one way to enhance labour market security and future income prospects (Blundell et al., Citation2000; O’Leary & Sloane, Citation2008), and lenders may be more willing to provide higher mortgages to the highly educated. Nevertheless, tertiary education normally entails prolonged economic dependency on the family of origin and substantial student debt, both of which are likely to delay the transition to homeownership (Andrew, Citation2010, Citation2012).

Whether or not young adults become homeowners does not always depend solely on their personal finances or future earning prospects. A growing body of research has highlighted the role played by parental resources. Young adults from more advantaged socio-economic backgrounds are more able to prolong co-residence with their parents, particularly if facing employment insecurity (Stone et al., Citation2011), enabling them to accumulate enough savings for a deposit on a house (Ermisch & Halpin, Citation2004). Loans or gifts towards housing costs is another way that parents help their children to get a foothold on the housing ladder (Heath & Calvert, Citation2013; Helderman & Mulder, Citation2007). Parents who are themselves homeowners will often have greater available resources, either in the form of housing equity or of household savings (Enström Öst, Citation2012; Mulder & Smits, Citation2013). Young adults without such parental support are disadvantaged and are more likely to live in the rental sector. The influence of the family of origin on young adults’ housing outcomes might also be exerted through a socialization mechanism, as parents directly or indirectly shape their children’s aspirations, preferences, knowledge and habitual behaviours (Boehm & Schlottmann, Citation1999; Charles & Hurst, Citation2003; Henretta, Citation1984; Lersch & Luijkx, Citation2015). Therefore, young adults who have grown up in owner-occupied housing are more likely to regard it as the ‘normal’ tenure and aim to achieve homeownership over their life course.

In addition to personal and familial resources, the affordability of house purchase depends considerably on the opportunity structure of the local housing market. Young adults’ transitions out of the parental home and into homeownership need to be examined within the spatio-temporal framework of the housing markets in which these transitions take place (Beer & Faulkner, Citation2011; Mulder & Wagner, Citation1998). Spatial differences in the relative cost of owner-occupation, for instance, are one of the aspects contributing to geographically unequal access to homeownership. Coulter (Citation2016a, Citation2016b) has shown that higher regional house prices dampen the probability of owner-occupancy in England and Wales; and research specifically on Scotland has recognized geographical variations in housing opportunities for young people, highlighting problems of access not only in expensive housing markets such as Edinburgh, but also in rural areas, where property prices are usually cheaper but job opportunities are fewer and wages are lower (Hoolachan et al., Citation2017; Jones, Citation2001).

Moreover, life course literature recognizes the role of individual resources in the development of different trajectories, while at the same time emphasising the situatedness of individual lives within networks of relationships and structural contexts. Therefore, our second research question investigates the role of both nest-leavers’ personal resources and the resources of their family of origin, as well as the contextual constraints imposed by local housing prices:

RQ2: Which personal, parental and contextual drivers of inequality shape advantage and disadvantage in young adults’ transitions to homeownership?

Lastly, acknowledging that individual life courses are embedded and shaped by temporal contexts, our third research question compares the experience of young nest-leavers in Scotland across the two consecutive but contrasting decades of the 1990s and 2000s. It asks:

RQ3: Have the drivers of inequality in young adults’ transitions to homeownership changed over time?

Existing evidence indicates that young adults in Scotland, as elsewhere in Europe, are staying longer in their parental home and those who leave are increasingly turning to housing tenures other than homeownership, in particular to privately rented accommodation. Less is known about who does and who does not become a homeowner. In this study we focus explicitly on the transition of nest leavers to homeownership. We use quantitative evidence from a large longitudinal dataset to extend previous work by examining both the diversity of housing transitions and the drivers of persisting and emerging inequalities in young adults’ access to homeownership.

Data and methods

We use data from the Scottish Longitudinal Study (SLS), a large-scale anonymized linkage study on a 5.3% sample of the Scottish population. For approximately 270 thousands individuals, the SLS links data from the 1991, 2001 and 2011 censuses and from other administrative sources. The SLS is a dynamic study, regularly updated by the linkage of vital registration and other administrative records. SLS members were initially selected from the 1991 census based on 20 birthdates. In addition, individuals born on the same dates enter the sample if they are either born in Scotland or have moved to Scotland during the decade. At the same time, SLS members leave the sample if they emigrate from Scotland or die during the decade. Analyzes of decadal changes are therefore limited to individuals who are enumerated both at the beginning and end of each decade (Boyle et al., Citation2009).

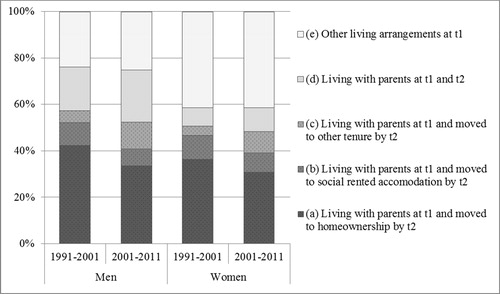

Our core data are from the last three Censuses of Scotland, which restricts our ability to undertake longitudinal analysis of the timing of moves out of the parental home and into owner-occupation. We therefore focus our analyses on decadal change and adopt a repeated cross-sectional design to examine the circumstances of young adults at the beginning and end of each of two decades. For the purpose of this study, young adults are defined as all SLS members who were aged 16–24 at the beginning of each decade. presents a breakdown of the living arrangements and housing tenure of young men and women in each of the decades between 1991 and 2011. Comparing the two decades, we see a decline in the proportion of young adults leaving their parental home and an increase in the proportion of young adults who are still living with their parents. In contrast, the proportion of young adults who had already left home at the beginning of each decade has remained fairly stable at around 25% for young men and 40% for young women, suggesting that these relatively ‘early leavers’ faced different housing market constraints compared to those who left home during the first decade of the new millennium when house prices rose steeply. The most notable decline, however, is in the overall proportion of young adults making the transition from parental home to homeownership during the decade, which fell from 42% in the 1990s to 34% in the 2000s among men and from 36% to 31% among young women.

Figure 1. Young adults aged 16–24 at the start of the decade, by living arrangement and housing tenure at the start and at the end of the decade. 1991–2001 and 2001–2011. Percentage distribution. Source: Authors’ analysis of the Scottish Longitudinal Study.

In order to investigate the transition to homeownership, we select only those individuals who are living with (at least one of) their parents (in a nuclear family) at the beginning of the decade (at time 1), and living away from their parental home in a private household ten years later (at time 2) (groups a, b and c in ). Young adults already living outside their parental home, or living with their parents but in a multi-generational household, at the start of each decade (group e), as well as those who were still living with their parents at the end of the decade (group d) are excluded from our analyzes.2 Our final analytical samples consist of 12,245 young adults for the decade 1991–2001 and of 9614 young adults for the decade 2001–2011.

A particular strength of the SLS is that it also collects information on individuals living in the same household at the time of the census (Boyle et al., Citation2009). Although our samples include SLS members only, we make use of information on their parents to derive measures of parental characteristics, and on their household composition to define their living arrangements. Another feature of the SLS is the availability of a detailed geography facilitating linkage to geographically referenced data. The study exploits this potential and enhances the dataset by linking individual records to data on local transactional house prices.

Our dependent variable is Housing tenure at time 2 (1 = homeownership; 0 = other tenure). Logistic regression models are used to estimate young adults’ probability of having moved out of the parental home and into owned accommodation by the end of the decade. Formally, the model can be expressed as follows (Agresti, Citation2013):

(1)

(1)

where

is the probability of becoming a homeowner by the end of the decade for the individual i and

is the vector of individual-level covariates.

All analyses are stratified by gender and partnership status. Partnership status is defined by looking at the living arrangement of the SLS member at the end of the period, and the variable distinguishes between those who are living with a partner and those who are not. This variable represents the best approximation of partnership trajectories throughout the period. Thus, for each decade we estimate four separate logistic regression models: for single men, single women, men in a couple and women in a couple.

The core independent variables included in the model capture the personal, parental and contextual characteristics associated with inequalities in the access to homeownership among young adults, as reported in the literature. The dataset does not include measures of individual or household income and we therefore use a range of proxy indicators: SLS members’ Educational attainment (below secondary, secondary, post-secondary) and a combination of their Employment status and Social class3 (employed-high, employed-medium, employed-low, unemployed, students, not in the labour force), all measured at time 2, are included to summarize the young adults socio-economic status by the end of the decade. For SLS members living with a partner at the end of the decade, the variable also distinguishes the Earner typology, i.e. whether they are living in a single- or dual-earner couple. Again, being measured at the end of the decade, these variables do not necessarily reflect young adults’ situation at the time they moved to homeownership. However, they do represent a better proxy of their socio-economic trajectories compared to the same measures at the start of the decade, when a large majority of young adults was still in education or at the early stage of their employment careers.

An additional variable accounts for young adults’ family background. We initially considered including both parental social class and housing tenure. However, we do not include parental social class in the final models, as its effect on young adults’ housing tenure is well captured by the inclusion of Parental housing tenure (homeownership, social rent, other tenure) alone.

Finally, as housing outcomes may be constrained by the characteristics of the local housing market, we include a measure of average Mean house prices in the Local Authority of residence at time 2. Data come from the Registers of Scotland, which record all residential property transactions with a purchase price between £20,000 and £1,000,000. The measure is included in the models as an ordered categorical variable, where each category corresponds to a quintile of the distribution of Local Authorities by Mean house prices. Local Authorities with the lowest prices fall in the first quintile, whereas those with the highest prices are in the fifth quintile.

Beyond these key analytical variables, our models also control for young adults’ Age and Health status, whether they were Living in a single parent household at the start of the decade and whether they Have children by the end of the decade.

The percentage distributions of the core independent and control variables are presented separately by gender and partnership status in (1a for the decade 1991–2001 and 1b for the decade 2001–2011). Reflecting trends observed for the total youth population in Scotland, the distribution of the main characteristics of the SLS sample shows an increasing proportion of young adults attaining post-secondary qualifications, growing employment levels for young women, and lower levels of homeownership for the smaller percentage of both single and partnered men and women who do leave the parental home during the decade.

Table 1. Percentage distribution of the variables included in the analyzes, by partnership status at time 2 and gender.

The multivariate analyses reported in the next section estimate the probabilities of transitioning to homeownership for all those who were living with their parents at time 1 but have moved away by time 2 in order to explore diversity and inequality among this group of young adults. Results are reported as Predicted Probabilities and Average Marginal Effects (AMEs). AMEs show how the predicted probability of being a homeowner by time 2 changes for each category of the predictor relative to the reference category, while the other variables are held at their observed values. Predicted Probabilities and AMEs also have the advantage of being directly comparable across groups and between models. Thus, if the confidence intervals of the estimates for our key variables across gender/partnership types do not overlap, then we are at least 95% confident that there is a difference. On the other hand, if there is a large overlap, then the difference is not statistically significant (Mood, Citation2010). A similar comparison can be made between the two decades, indicating whether the change over time is statistically significant.

The nature of SLS data imposes some limitations on the interpretation of the results. We cannot, for example, determine the exact timings of transitions to homeownership and partnership formation. Nor do we know when other changes in individual circumstances occurred, or the number of residential moves that individuals made during the 10-year period between censuses. More detailed longitudinal data with full educational, employment, partnership and housing histories would be needed to investigate the causal direction of the relationships between changes in young adults’ circumstances and the move to owner-occupation. Nevertheless, the SLS provides a large representative sample of the Scottish population, enabling us to focus on a select age group while still making use of detailed classifications of young adults’ characteristics and to explore demographic diversity in relation to homeownership by stratifying the empirical analyses by gender and partnership status. Further, because the SLS links data from the 1991 census onward, we are able to observe decadal changes across two time periods, 1991–2001 and 2001–2011, which is of particular interest for providing insights into inequalities in transitions to homeownership that are persistent over longer periods of time and others that have emerged in the context of the recent housing crisis.

Results

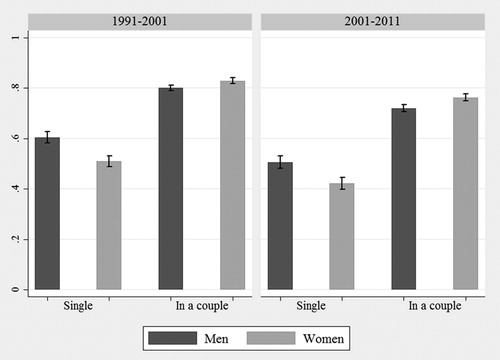

Our three research questions draw inspiration from the recent theoretical developments on the fluidity and diversity of housing and life course experiences among young adults (Beer & Faulkner, Citation2011). To address our first research question, we investigate diversity in young adults’ transitions to homeownership by examining whether the probability of becoming a homeowner by the end of the decade of interest differs between single men and women, and women and men living with a partner. reports unadjusted predicted probabilities (and their confidence intervals) by gender and partnership status for each decade. Comparing the two decades, we can also determine whether any differences between these groups have changed over time.

Figure 2. Demographic diversity in transitions to homeownership: unadjusted predicted probability, by gender and partnership status. Decade 1991–2001 and 2001–2011. Source: Authors’ analysis of the Scottish Longitudinal Study.

As might be expected, in both decades, young Scots living in a couple have the highest probabilities of being homeowners by the end of the period. There are, however, significant differences between men and women in our samples. In both decades single women are less likely than single men to be homeowners by the end of the period. On the other hand, young women who are living with a partner by the end of the decade are more likely than partnered men to be living in owned accommodation. Further, the comparison of predicted probabilities for the two decades clearly indicates an overall significant reduction in the chances of becoming a homeowner for all young adults, although the decline appears more pronounced for those living as singles at time 2.

Our second and third research questions focus attention on the drivers of inequalities. Our interest is in how personal and parental resources, as well as the characteristics of local housing market, define the chances of young adults’ becoming homeowners, which groups are disadvantaged, and how this may have changed over time.

presents the average marginal effects (AMEs) from the estimation of logistic regression models for the four groups of young adults (by gender and partnership status), for the two decades.

Table 2. Logistic regression models on the probability of becoming homeowners by time 2, by gender and partnership status.

We address our second research question by focussing explicitly on the most recent decade (2001–2011), and investigating the main drivers of inequality in the probability of becoming a homeowner. Results are reported in the left panel of . They confirm the existence of pronounced socio-economic inequalities in transitions to homeownership, as both individual and parental resources are significantly associated with young adults’ chances of moving to owned accommodation.

Compared to young adults who attained post-secondary qualification, those who did not complete secondary education have the lowest chances of becoming homeowners by 2011. This result holds for men and women, both single and living with a partner. Additionally, having only a secondary qualification is negatively associated with the probability of homeownership for single women and for men in a couple.

Results also highlight the existence of clear differences in homeownership rates for both young men and women depending on their employment and social class status. Among nest leavers who are single in 2011, those who are employed in lower status occupations are significantly less likely to become homeowners compared to individuals in high status jobs. Moreover, not being in employment at the end of the decade is associated with much lower probabilities of homeownership for both men and women. Interestingly, no significant gender differences are observed in the association between employment status/social class and homeownership among adults who are single at the end of the decade. Yet a clear occupational status differential is evident among young adults living in a couple at the end of the decade. In particular, among individuals in a dual-earner couple, those in lower status occupations have a significantly lower probability of being in owned accommodation by the end of the decade compared to young adults in high status jobs. Further, all young adults within a single-earner couple show significantly lower probabilities than the reference category, with those in lower status occupations displaying the lowest. The negative effect of being the only earner in a couple is greater for women than men, although the differences in AMEs are only statistically significant for single-earners in lower status occupations. Lastly, not being in employment is associated with lower probabilities of becoming a homeowner, but its negative effect is significantly stronger for partnered men than for partnered women.

Inequalities associated with family background are assessed through the inclusion of parental housing tenure in the models. The predicted probability of owner-occupation is significantly lower for the adult children of social renters as compared with young adults whose parents were homeowners. A negative effect is also observed for young adults whose parents were in private rented accommodation, although this group represents only 3% of the total sample of nest leavers. A further specification of the models (results not presented) included a measure of parental social class and confirmed that individuals from lower socio-economic backgrounds are less likely to move to owner-occupation.

The probabilities of moving to owner-occupation during the decade 2001–2011 for young men and women living in a couple also respond to regional differences in housing prices. Partnered men living in local authorities within more expensive local housing markets (the third, fourth and fifth quintile of the housing prices distribution), and partnered women living in the most expensive local authorities (in the fifth quintile), have significantly lower probabilities of being in owner-occupation compared with partnered men and women who are living in local authorities with the lowest mean housing prices. In contrast, young singles appear to be less sensitive to local house prices, possibly because fewer of them make the transition to homeownership and, when they do, may be purchasing smaller housing units.

Our analyses thus far indicate that young adults’ probabilities of moving from their parents' home into owner-occupation has decreased over the last two decades, and that personal, parental and local housing market characteristics all play an important role in shaping current inequalities in access to homeownership. A comparison of these results with results for the previous decade allows us to address the third and last research question, and to explore whether the decline in homeownership rates reflects emerging or widening inequalities as housing outcomes become more socially and geographically polarized.

To address the final research question, we compare the AMEs (and their confidence intervals) estimated for the decade 2001–2011 (, left panel) with those for the same age group of young adults in the previous decade, 1991–2001 (, right panel). Results show the existence of very similar patterns of disadvantage in transitions to owner-occupation across the two decades. As in the 2000s, education, employment status/social class, parental housing tenure and, for some, education are significant drivers of the transition to homeownership in the 1990s, suggesting enduring inequalities. At the same time, for some young adults new inequalities have emerged and others have become more pronounced.

Among young singles, educational attainment in the 1990s did not differentiate their probability of becoming homeowners as it does in the first decade of the 2000s. Young adults without secondary education were not significantly less likely to be in owner-occupation as compared with those with post-secondary qualifications, and women with secondary education were even more likely than the reference category to have secured homeownership by the end of the decade. There are, however, no statistically significant differences in the unequal way that young adults’ employment status/social class affects their chances of being in owner-occupation across the two decades. Parental housing tenure is also persistently associated with young singles’ housing tenure, as those whose parents were social renters are significantly less likely in both decades to become homeowners. Further, the negative effect of having parents who were private renters becomes statistically significant in the last decade. For young singles, the effect of house prices in local housing markets is less clear and differences between the decades are not statistically significant.

Among young adults living with a partner at the end of the decade, inequalities associated with educational attainment and occupational status are consistent across the two decades. Although the magnitude of the AMEs in the most recent decade as compared to the previous one suggests a widening of educational differences for men and a more pronounced negative effect of being the sole earner in a couple for women, these differences are not statistically significant in our models. However, the disadvantage for partnered young men whose parents were social renters as compared to those whose parents were homeowners has widened significantly, while securing homeownership for young women living with a partner has become more difficult over the second decade in the most expensive local housing markets.

In sum, our findings reveal significant demographic diversity: not only are men more likely than women, and partnered individuals more likely than single, to become homeowners, but gender and partnership status interact in shaping the transition to homeownership of young adults in Scotland. Whereas single women are less likely than single men to become homeowners, women are more likely to become homeowners if they live with a partner. For all young adults, similar patterns of advantage and disadvantage are observed, with personal resources as well as parental background defining inequalities in the transition to homeownership. While these inequalities persist over time, the decadal comparison also suggests that the distance between the most and least advantaged has widened among single women and among partnered men and women.

Discussion

Homeownership rates amongst young adults have declined in several Western countries. While this partly reflects the changing nature of the transition to adulthood, which has become increasingly extended and diversified, there is also growing concern in the UK that widening social inequalities within the current period of economic austerity might be resulting in some population groups facing greater challenges than in the past in accessing the homeownership market. Our study investigates transitions to homeownership among young adults in Scotland between 2001 and 2011, and compares the results to similar transitions in the previous decade. As observed elsewhere, stepping onto the property ladder at younger ages has become less common in Scotland as more young adults are remaining in their parental home, or are moving to (and staying longer in) private rented accommodation if they leave (Sissons & Houston, Citation2018).

The study contributes to the ongoing debate on the reasons for declining homeownership levels among young adults by addressing three research questions. First, it explores the issue of demographic diversity by asking whether young adults’ transitions to homeownership vary by gender and partnership. In line with existing literature on housing and the life course (Blaauboer, Citation2010; Clark & Mulder, Citation2000; Mulder, Citation2003, Citation2013; Mulder & Hooimeijer, Citation2002), our study reports that young adults living with a partner have higher rates of homeownership compared to singles. Different reasons might explain this diversity. It might be that young adults living as single prefer private renting as a more temporary and flexible arrangement with lower upfront costs, particularly if they are at the beginning of their employment career. Living in a co-residential partnership, on the other hand, reflects greater stability and commitment to long-term goals, including the joint purchase of a house (Thomas & Mulder, Citation2016). Partnered individuals also benefit from joint household production, as they can pool their resources to cover the costs associated with homeownership (Mulder & Wagner, Citation1998). This view is supported by our findings which show that levels of homeownership are significantly higher for young adults living in dual-earner couples.

Demographic literature suggests that gender plays an important role in decisions to leave the parental home (Blaauboer & Mulder, Citation2010; Chiuri & Del Boca, Citation2010; Corjin & Klijzing, Citation2001). To the extent that women tend to leave home earlier than men, but more often in order to live with a partner (Billari & Liefbroer, Citation2007; Kerckhoff & Macrae, Citation1992), and women tend to partner with men a few years older than themselves, gender is recognized as an important dimension of diversity in the transition to homeownership. Our analyzes show that younger women in Scotland are less likely to become homeowners than younger men, possibly because, on average, they earn less and thus delay the transition into ownership until they embark on the process of family formation and can pool resources with their partners. This observation is supported by our finding that women, if partnered, are more likely than men to be homeowners. Conversely, levels of homeownership are lower for single women than for single men in our samples. It may be that the housing preferences of single young adults are shaped by gendered expectations about their future lives (Saugeres, Citation2009). While young women might anticipate their dependency on a partner’s income during their childrearing years, and therefore be more reluctant to commit to homeownership, single young men rely on the continuity of their labour market engagement and have expectations about their role as the main income provider (Blaauboer, Citation2010). Gendered routes out of the parental home, as well as the ability to afford homeownership, are thus likely to condition the housing preferences of single men and women, although we cannot directly test this with our data. We do observe, however, that a greater percentage of single women than single men in our sample is living as a lone parent, which determines not only the resources available to cover housing costs but most importantly their entitlement to access the social rented sector. The inclusion in our multivariate analyses of a control variable for the presence of children in the household, and its negative association with homeownership among single women, supports this latter view. Thus, our results suggest that gendered pathways to adulthood might also be leading to differences between men and women in their housing preferences and behaviour.

The second research question concentrates attention on the drivers of inequality that are shaping recent patterns of advantage and disadvantage in young adults’ transitions to homeownership. Demographic diversity might also find expression in the way inequalities are defined, as gender and partnership configure different opportunities and constraints in the lives of young women and men.

Previous research on young peoples’ transitions to homeownership in Britain and in the European context has highlighted the existence of social disparities, showing that young adults with lower education and socio-economic status are more likely to be excluded from the homeownership market (Coulter, Citation2016a, Citation2016b; Enström Öst, Citation2012; Lersch & Dewilde, Citation2015). Our analyses confirm these disparities for young adults in Scotland. Those who achieve post-secondary qualifications by the end of the decade are the most likely group to become homeowners and there is a clear gradient in occupational status (as measured by the combination of employment status and social class). Those employed in professional/managerial jobs are more likely to become homeowners by the end of the decade than those of any other employment/social class group. Moreover, the chances of homeownership decline across other employment/social class groups, being lowest for singles or men in couples who are not in employment and for women in low status occupations whose partner is not in employment. As expected, higher education and well-paid professional/managerial employment give significant advantages for achieving homeownership. Further, the benefits of pooling resources for young adults living with a partner are also evident, as men and women in co-residential couples where both partners are earning have higher chances of becoming homeowners compared to those in single-earner couples. Interestingly, whereas our findings for single young adults support the argument that men and women have become more alike in terms of how they move into adult roles (Furstenberg, Citation2010), the analyses for young adults living in a couple show that the resources of the man are still more important for achieving homeownership than the resources of the woman (Mulder & Smits, Citation1999). We find that, for both partnered men and women in single-earner couples, the probabilities of the transition to homeownership are much lower when the man is not employed compared to when the woman is not in employment.

Inequalities are not shaped only by young adults’ personal resources. The role of parental resources in influencing young adults’ transitions to homeownership has been the subject of a growing body of recent literature, which argues that children from less privileged backgrounds face greater challenges in accessing the housing market (Coulter Citation2016a, Citation2016b; Druta & Ronald, Citation2016; Heath & Calvert, Citation2013). Indeed, our results show that parental homeownership is strongly associated with the chances of achieving homeownership for young adults, thus reproducing existing inequalities across generations. This confirms for Scotland what other studies have found for England and Wales, namely that adult children of tenants – either in the social or private rented sector – are less likely to become homeowners (Coulter, Citation2016a, Citation2016b, Citation2016c).

We hypothesized, in addition, that inequalities in young adults’ transitions to homeownership are shaped by local variations in the opportunity structures of the housing market; young adults would struggle more to get a foot on the housing ladder in local housing markets where average house prices are high, as the financial resources needed for the transition to homeownership would also be higher than in lower-cost housing markets. Our results for the more recent decade partly confirm this hypothesis. Interestingly, although generally less likely than men and women in couples to become homeowners, neither single men nor single women are especially disadvantaged in expensive housing markets despite the steep rise in house prices during the 2000s. In contrast, men living in a couple experience disadvantage in medium to high cost markets but women living in a couple are least likely to become homeowners only in the most expensive local housing markets. The diversity among those living as single and those in a couple suggests that the impact of different housing markets is not only gendered but also depends on individual life course choices. It may be that single young adults prioritize urban location over housing costs (Sissons & Houston, Citation2018) and those who do make the transition to homeownership are therefore likely to be concentrated in smaller housing units in higher cost markets. Men and women in couples, on the other hand, may seek larger ‘family’ housing and, if they plan to have children, may expect to rely primarily on the man’s income at least in the short term, resulting in a greater sensitivity to local house prices among young adult men who are living with a partner. Our results hint at, but do not confirm, a changing pattern of association between house prices and transitions to homeownership across the demographically diverse groups. It would be interesting to see whether or not this is confirmed in the 2010s when the full impact of the economic downturn and austerity measures are more likely to be manifest.

The final research question focuses attention on temporal change in the main drivers of inequality. Comparison of the results for the 2000s with those for the 1990s reveals enduring inequalities, as particular individual socio-economic characteristics and parental housing tenure have been associated with young adults’ transitions to homeownership for at least two decades. However, while the probability of young adults becoming homeowners has generally declined over time for all population groups, some patterns of disadvantage have become more pronounced, and new inequalities have emerged in the more recent period.

For singles, the relative advantage of having attained secondary education has disappeared for women, and the relative disadvantage of lower educational achievement appears to have increased for both men and women, although the latter differences are not statistically significant. While the gradient of socio-economic disadvantage has changed little, the transition of single men and women to homeownership seems to have become less responsive to local house prices over time. This finding is not easily explained but could be related to changes in the housing preferences of singles. Further research is needed to investigate whether the geographical distribution of homeowners in this group has also changed between the two decades, and how this relates to local house prices.

Importantly, for young adults who are living with a partner by the end of the period, who represent the majority in our study samples, inequalities associated with personal as well as parental resources have widened over time. The probabilities of becoming homeowners have become especially low for individuals – particularly women – who are the sole earner in the couple, confirming the greater importance of pooling resources between partners at a time of declining housing affordability. The relative (and increasing) disadvantage of single-earner couples compared to dual-earner couples is a feature that Scotland shares with the rest of the UK. Thomas & Mulder (Citation2016) noted that being part of a dual-earner couple is of much greater importance for achieving homeownership in the comparatively (and increasingly) expensive UK housing market, than it is in the Netherlands or in Germany; and the study by Coulter (Citation2016b) on England and Wales reported a deterioration in the relative position of single-earner couples in more recent cohorts. At the same time, local house prices in higher cost housing markets emerged as a significant constraint on transitions to homeownership. As rapid house price increases outstripped wage increases in the 2000s (Cribb et al., Citation2018), and mortgage lenders required substantial deposits towards house purchase, housing affordability became a major challenge for young first time buyers. Even before the global financial crisis towards the end of the decade, more and more young people were turning to their families for financial help (Tatch, Citation2007).

Our findings for Scotland indicate decreases across the two decades in the likelihood of making the transition to homeownership for both young singles and those living in couples whose parents are social housing tenants compared to those whose parents are themselves owner-occupiers. This is consistent with young people increasingly relying on parental support to establish themselves in the housing market, as has been found in other parts of the UK (Coulter, Citation2016b), and suggests the further deepening of social inequalities across generations. For adult children from disadvantaged family backgrounds, homeownership is becoming even more out of reach, while for those with greater family support, the achievement of homeownership is increasingly dependent on familial resources (McKee, Citation2012).

Conclusions

This study has revealed diversity in the life courses of young men and women that influence their transitions to homeownership, and marked inequalities in who gets onto the housing ladder in Scotland. Evidence on the patterns of advantage and disadvantage suggests that the main drivers of inequality are entrenched, having persisted at least since the early 1990s. Nevertheless, some inequalities have widened over time as new groups in the young adult population experience advantages and disadvantages related to their own household resources and the resources of their parents. It is likely that these emerging inequalities will have widened further in the past few years in response to the on-going impacts of the economic recession and the failures of local housing markets to respond to demands for affordable housing.

Narratives of a ‘housing crisis’ and ‘generation rent’ emphasize the difficulties for young people in making the transition to homeownership, difficulties that were heightened following the credit crunch and global economic crisis of 2007/08. Homeownership is seen as increasingly unaffordable for many millennials due to sharply increasing house prices, low-paid or precarious employment and a mortgage squeeze. In line with the rest of the UK, we have shown that rates of homeownership over the last two decades have declined for all young adults in Scotland. However, following nearly a decade of house price inflation and increasing levels of youth economic insecurity, young adults’ access to homeownership appears to have become more socially uneven. Lower educational attainment, unemployment, not having an earning partner and not having parents who can provide financial assistance, all condition to a greater extent than before young adults’ ability to buy a house. With the residualization of social housing following the introduction of Right to Buy legislation in 1980, intergenerational transmission of disadvantage from the smaller number of social tenants to their adult children has become even more evident. Widening differences between the least and most expensive housing markets might be among the factors contributing to a more geographically uneven housing market. Whether these drivers of inequality are combining to produce cumulative advantage and disadvantage would be an interesting path for future enquiry.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore demographic diversity by examining young adults’ transitions to homeownership separately by gender and partnership status. It demonstrates that the likelihood of becoming a homeowner varies for men and women and is associated with life course choices, such as when to live with a partner. It also suggests the importance of linked lives, where some parents are able to help their offspring get onto the housing ladder. This is of interest not only because it reveals that gendered pathways to adulthood shape levels of homeownership, but also because young adults leaving the parental home to live as singles represent only a minority. The majority of young adults who undertake this transition are living with a partner and, for them, social inequalities over the first decade of the 2000s have widened to a greater extent, with possible implications for other demographic transitions. Given the well-established link between housing and family formation, leaving the parental home to start a family could be increasingly postponed for the less privileged groups of young adults who cannot rely on their partner’s income and their parents’ support.

The longitudinal design of SLS and large sample size allowed us to compare the circumstances of individual young adults in Scotland at the time they were still living with their parents, with the outcomes of their employment, educational, partnership and housing trajectories 10 years later. It is possible that limiting the study to young adults still living with their parents at the start of each decade produced biased estimates, particularly as early leavers may differ in their probability of becoming homeowners. Nevertheless, the stability in the proportion of early leavers becoming homeowners across the two decades (approximately 40%) leads us to expect that any bias will be consistent over time and thus not affect our decadal comparisons. Importantly, we were unable to determine the timings of the transitions out of the parental home and into homeownership during each decade. We could not therefore investigate detailed individual trajectories or the role of ‘surprises’(Ermisch & Di Salvo, Citation1996), or ‘turning points’ (Stone et al., Citation2014), such as partnering, partnership breakup, or spells of unemployment, or examine the impact of exogenous shocks such as the global financial crisis on housing tenure. Nor were we able to establish the ordering of events such as having a child and purchasing a home, and cannot therefore determine causality. While these are all critical topics for further research, they await a suitably large and detailed dataset for the unique context of the Scottish housing market.

Social inequalities in access to homeownership are not new. What is new, at least since the 1980s, is the ubiquity of the aspiration to own a home, the available alternatives to homeownership and the extent to which different groups are advantaged or disadvantaged in making the transition to homeownership. In Scotland, as in the rest of the UK, the current housing crisis is especially affecting young adults seeking to establish independent living arrangements. Some groups – defined by their personal characteristics, including gender and partnership status – are more disadvantaged than others. For them, the contraction of social housing means that the alternatives to homeownership are now either to remain living with their parents or to rent in the private sector. Understanding this socio-demographic diversity as it affects housing careers contributes to the evidence base for policy development. The distinctiveness of the Scottish housing system provides the opportunity for the Scottish Government to develop different policies, appropriate to Scotland (McKee & Phillips, Citation2012). Steps have already been taken in this direction with the suspension of the Right to Buy legislation and the increased regulation of the private rented sector through the Private (Tenancies) (Scotland) Act 2016. At the UK level, the aspirational norm among young people remains homeownership but what is needed in Scotland is a more multi-faceted approach to the housing crisis that not only promotes secure and good quality affordable housing in the private sector but also (again) recognizes the positive contribution of social housing to reducing current inequalities in Scottish society.

Acknowledgements

Francesca Fiori undertook the work for this paper when she was a Research Fellow at the University of St Andrews. This research was funded by the ESRC Secondary Data Analysis Initiative (Grant Number ES/K003747/1).

The help provided by staff of the Longitudinal Studies Centre – Scotland (LSCS) is acknowledged. The LSCS is supported by the ESRC/JISC, the Scottish Funding Council, the Chief Scientist's Office and the Scottish Government. Census output is Crown copyright and is reproduced with the permission of the Controller of HMSO and the Queen's Printer for Scotland. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions of this analysis are solely those of the authors and should not be attributed in any manner to the ESRC, National Records of Scotland (NRS) or LSCS.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Right to Buy legislation was suspended in Scotland in August 2016 but not before it had had a major impact on the availability of social housing.

2 We also dropped students who are residing elsewhere during term time to ensure comparability of our samples, as information on them was not collected at their parents’ household in the 2001census.

3 Our measure of social class was derived using the national statistics socio-economic classification (grouped to analytical class) which provides an indication of socio-economic position based on occupation. As this is only available for individuals who are employed, to avoid collinearity issues between employment status and social class we combined the two variables. Our category employed-high includes employers in large organisations and those in higher managerial occupations, higher professional occupations, lower professional and higher technical occupations and lower managerial and higher supervisory occupations. Employed-medium consists of intermediate occupations, employers in small organisations, own account workers, and lower supervisory and lower technical occupations, whereas employed-low includes semi routine and routine occupations. For individuals who are not in employment, the variable then distinguishes between unemployed, student and inactive.

References

- Aassve, A., Billari, F.C., Mazzuco, S., & Ongaro, F. (2002) Leaving home: a comparative analysis of ECHP data, Journal of European Social Policy, 12(4), pp. 259–275.

- Aassve, A., Cottini, E. & Vitali, A. (2013) Youth prospects in a time of economic recession, Demographic Research, 29(36), pp. 949–962.

- Agresti, A. (2013) Categorical Data Analysis, 3rd ed. (New York, NY: Wiley).

- Andrew, M. (2010) The changing route to owner occupation: the impact of student debt, Housing Studies, 25(1), pp. 39–62.

- Andrew, M. (2012) The changing route to owner occupation: the impact of borrowing constraints on young adult homeownership transitions in Britain in the 1990s, Urban Studies, 49(8), pp. 1659–1678.

- Beer, A. & Faulkner, D. (2011) Housing Transitions Through the Life Course: Aspirations, Needs and Policy (Bristol: The Policy Press).

- Billari, F.C. & Liefbroer, A. (2007) Should I stay or should I go? The impact of age norms on leaving home. Demography, 44(1), pp. 181–198.

- Billari, F.C. & Liefbroer, A. (2010) Towards a new pattern of transition to adulthood? Advances in Life Course Research, 15(2–3), pp. 59–75.

- Blaauboer, M. (2010) Family background, individual resources and the homeownership of couples and singles, Housing Studies, 25(4), pp. 441–461.

- Blaauboer, M. & Mulder, C.H. (2010) Gender differences in the impact of family background on leaving the parental home, Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 25(1), pp. 53–71.

- Blundell, R., Dearden L, Goodman, A. & Reed, H. (2000) The returns to higher education in Britiain: Evidence from a British cohort. The Economic Journal, 110(461), pp. 82–99.

- Boehm, T. P. & Schlottmann, A. M. (1999) Does homeownership by parents have an economic impact on their children? Journal of Housing Economics, 8(3), pp. 217–232.

- Boyle, P. J., Feijten, P., Feng, Z., Hattersley, L., Huang, Z., Nolan, J. and Raab, G. (2009) Cohort profile: the Scottish longitudinal study (SLS). International Journal of Epidemiology, 38(2), pp. 385–92.

- Buck, N. & Scott, J. (1993) She’s leaving home: But why? An analysis of young people leaving the parental home. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 55(4), pp.863–874.

- Charles, K.K. & Hurst, E. (2003) The correlation of wealth across generations, Journal of Political Economics, 111(6), pp. 1155–1182.

- Chiuri, M.C. & Del Boca, D. (2010) Home-leaving decisions of daughters and sons, Review of Economics of the Household, 8(3), pp. 393–408.

- Clapham, D., Mackie, P., Orford, S., Thomas, I., Buckley, K. (2014) The housing pathways of young people in the UK, Environment and Planning A, 46, pp. 2016–2031.

- Clark, W.A.V. & Mulder, C.H. (2000) Leaving home and entering the housing market. Environment and Planning A 32(9), pp. 1657–1671.

- Corjin, M. & Klijzing, E. (2001) Transitions to Adulthood in Europe (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publisher).

- Coulson, E. & Fisher, L. (2009) Housing tenure and labor market impacts: the search goes on, Journal of Urban Economics, 65(3), pp. 252–264.

- Coulter, R. (2016a) Local house prices, parental background and young adults’ homeownership in England and Wales, Urban Studies.

- Coulter, R. (2016b) Parental background and housing outcomes in young adulthood, Housing Studies.

- Coulter, R. (2016c) Social disparities in private renting amongst young families in England and Wales, 2001–2011, Housing, Theory and Society.

- Cribb, J., Hood, A. & Hoyle, J. (2018) The Decline of Homeownership Among Young Adults, Institute for Fiscal Studies Briefing note BN224 (London: The Institute for Fiscal Studies)

- Druta O. & Ronald, R. (2016) Young adults’ pathways into homeownership and the negotiation of intra-family support: a home, the ideal gift, Sociology. doi:10.1177/0038038516629900.

- Elder, G.H., Johnson, M.K. & Crosnoe, R. (2003) The emergence and development of life course theory, in: J.T. Mortimer & M. J. Shanahan (Eds) Handbook of the Life Course, pp. 3–19 (New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers).

- Enström Öst, C. (2012) Parental wealth and first-time homeownership; A cohort study of family background and young adults’ housing situation in Sweden, Urban Studies, 49(10), pp. 2137–2152.

- Ermisch, J. & Halpin, B. (2004) Home ownership and social inequality in Britain, in: K. Kurz & H.-P. Blossfeld (Eds) Home Ownership and Social Inequality in Comparative Perspective, pp. 255–280 (Stanford: Stanford University Press).

- Ermisch, J. & Di Salvo, P. (1996) Surprises and housing tenure decisions in Great Britain, Journal of Housing Economics, 5(3), pp. 247–273.

- Furstenberg, F.F. (2010) On a new schedule: transitions to adulthood and family change. The Future of Children, 20(1), pp. 67–87.

- Gauthier, A. (2007) Becoming a young adult: an international perspective on the transitions to adulthood, European Journal of Population, 23(3-4), pp. 217–234.

- General Register Office for Scotland (2003) Scotland’s Census 2001 Reference Volume (Edinburgh: General Register Office for Scotland).

- Goldscheider, F., & Goldscheider, G. (1999) The Changing Transition to Adulthood. Leaving and Returning Home (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage).

- Graham, E., Fiori, F. & McKee, K. (2017) Invited Chapter: Household Changes and Housing Provision in Scotland, in: National Records of Scotland (Ed) Scotland's Population 2016 – The Registrar General's Annual Review of Demographic Trends, pp. 85–109 (Edinburgh: National Records of Scotland).

- Heath, S. & Calvert, E. (2013) Gifts, loans, and intergenerational support for young adults, Sociology, 47(6), pp.1120–1135.

- Helderman, A. & Mulder, C. (2007) Intergenerational transmission of homeownership: the roles of gifts and continuities in housing market characteristics, Urban Studies, 44(2), pp. 231–247.

- Henretta, J.C. (1984) Parental status and child’s home ownership, American Sociological Review, 49(1), pp. 131–140.

- Hoolachan, J., McKee, K., Moore, T. & Soaita, A.M. (2017) ‘Generation rent’ and the ability to ‘settle down’: economic and geographical variation in young people’s housing transitions, Journal of Youth Studies, 20(1), pp. 63–78.

- Iacovou, M. (2010) Leaving home: Independence, togetherness and income, Advances in Life Course Research, 15(4), pp. 147–160.

- Jones, G. (2001) Fitting Homes? Young people’s housing and household strategies in Rural Scotland, Journal of Youth Studies, 4(1), pp. 41–62.

- Kerckhoff, A. C., & Macrae, J. (1992) Leaving the parental home in Great Britain: a comparative perspective. Sociological Quarterly, 33(2), pp. 281–301.

- Lersch, P.M. & Dewilde, C. (2015) Employment insecurity and first time home-ownership: evidence from twenty-two European countries. Environment and Planning A, 47, pp. 607–624.

- Lersch, P.M. & Luijkx, R. (2015) Intergenerational transmission of homeownership in Europe: revisiting the socialisation hypothesis, Social Science Research, 49, pp. 327–342.

- McKee, K. (2012) Young people, homeownership and future welfare, Housing Studies, 27, (6), pp. 853–862.

- McKee, K., Muir, J. & Moore, T. (2017) Housing policy in UK: the importance of spatial nuance, Housing Studies, 32, (1), pp. 60–72.

- McKee, K. & Phillips, D. (2012) Social housing and homelessness policies: reconciling social justice and social mix, in: G. Mooney & G. Scott (Eds) Social Justice and Social Policy in Scotland, pp. 227–242 (Bristol: Policy Press).

- Mitchell, B. A. (2004) Making the move: cultural and parental influences on Canadian young adults’ homeleaving decisions. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 35(3), pp. 423–441.

- Mood, C. (2010) Logistic regression: why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it, European Sociological review, 26(1), pp.67–82.

- Mulder, C.H. (2003) The housing consequences of living arrangements choices in young adulthood. Housing Studies 18(5), pp. 703–719.

- Mulder, C.H (2013) Family dynamics and housing: conceptual issues and empirical findings, Demographic Research, 29(14), pp. 355–378.

- Mulder, C.H. & Hooimeijer, P. (2002) Leaving home in the Netherlands: timing and first housing. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 17(3), pp. 237–268.

- Mulder, C.H. & Smits, A. (2013) Inter-generational ties, financial transfers and homeownership support, Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 28(1), pp. 95–112.

- Mulder, C.H. & Smits, J. (1999) First-time home-ownership of couples: the effect of inter-generational transmission, European Sociological Review, 15(3), pp. 323–337.

- Mulder, C.H. & Wagner, M. (1998) First-time home-ownership in the family life course: a West German–Dutch comparison, Urban Studies, 35(4), pp. 687–713.

- National Records of Scotland (2013) Statistical Bulletin. 2011 Census: Population and Household Estimates for Scotland. Release 3L – Detailed characteristics on Housing and Accommodation in Scotland. Available at: http://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/news/census-2011-release-3l-detailed-characteristics-housing-and-accommodation-scotland (accessed 9 April 2017).

- O’Leary, N.C. & Sloane, P.J. (2008) Rates of returns to degrees across British regions. Regional Studies, 42(2), pp. 199–213.

- Ronald, R. (2008) The Ideology of Home Ownership: Home Owner Societies and the Role of Housing (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan).

- Rusconi, A. (2004) Different pathways out of the parental home: a comparison of West Germany and Italy, Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 35(4), pp. 627–649.

- Saugeres, L. (2009) ‘We do get stereotyped’: gender, housing, work and social disadvantage, Housing, Theory and Society, 26(3), pp. 193–209.

- Sissons, P. & Houston, D. (2018) Changes in transitions from private renting to homeownership in the context of rapidly rising house prices, Housing Studies.

- Stone, J., Berrington, A. & Falkingham, J. (2011) The changing determinants of UK young adults’ living arrangements, Demographic Research, 25(20), pp. 629–666.

- Stone, J., Berrington, A. & Falkingham, J. (2014) Gender, turning points, and boomerangs: returning home in young adulthood in Great Britain, Demography, 51(1), pp. 257–276.

- Tatch, J. (2007) Affordability: Are Parents Helping? Housing Finance (London: Council for Mortgage Lenders).

- Thomas, M.J. & Mulder, C.H. (2016) Partnership patterns and homeownership: a cross country comparison of Germany, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, Housing Studies, 31(8), pp. 935–963.

- Whittington, L. & Peters, H. E. (1996) Economic incentives for financial and residential independence. Demography, 33(1), pp. 82–97.