Abstract

This article examines the crises of post-war modernist housing estates in West Germany and Austria, illuminating the key differences that emerged despite the strong similarities in terms of urban design and share in overall housing stock. With an analysis of the different framing and narration in the professional discourse between 1960 and 1990, the paper reveals that the estates served as a battleground for negotiating broader socio-political questions, resulting in different politizations of the estates. By deciphering the complex and partly contingent entanglements between the built form and politics, the paper contributes to research on post-war modernist housing estates and to the reassessment of these urban structures. It also enhances our understanding of the varied perceptions and performances of the ‘same’ built structures, thereby opening up new perspectives for the ongoing discussions about the revival of mass housing.

Introduction

My experience with the different perceptions of post-war modernist housing estates in GermanFootnote1 and Austrian professional debates provided the initial impetus for the research. Trained as an architect and urban designer in Austria, I considered the large-scale housing estates, built from the 1950s up to 1970s, as only one of the periods in the long and complex history of urban planning and design, marked by its unique advantages and shortcomings as well as supporters and critics. After relocating to Germany to pursue a doctorate in urban studies, I noted a much more critical view of the urban heritage of this period. Indeed, the topic of post-war housing estates dominates university seminars, lectures on urban planning and development as well as the wider literature on housing development in Germany. This paper explores why the dominant discourse in Austria and Germany treats these built structures differently, despite their numerous similarities. It analyses different crises of post-war modernist housing estates, re-constructs how they evolved and identifies major influencing factors.

The paper engages with crises as socially constructed and politically shaped processes. It puts forward an analytical framework based on Hay’s (Citation1996) concept of crisis construction and Keller’s (2007, 2011) approach to discourse analysis, reconstructing the emergences of what came to be perceived as the crisis of post-war modernist housing estates. The paper finds that these estates were framed and narrated differently in each country; however, these differences cannot be sufficiently explained by diverging quantities or qualities of the built structures. Instead, post-war modernist housing estates became a battleground of pressing socio-political questions, resulting in different politizations of the estates.

The paper deciphers the complex and partly contingent entanglements between the built form and politics, thereby contributing to the interdisciplinary scholarship on post-war modernist housing estates and to the recent debates on the ‘revival’ of mass housing. By foregrounding the socio-political rather than the built environment roots of crisis, the findings caution against generalizations and transfers of context-specific problematizations. An enhanced understanding why perceptions and performances of the ‘same’ built structures are different in different contexts is also essential for guiding the renewed efforts to build mass housing today. Indeed, such insights might offer new perspectives by indicating and legitimising novel ways forward in mass housing provision.

The cases of Austria and the Federal Republic of Germany can be regarded as very similar in terms of their socio-political, cultural and planning context (Hafner et al., Citation1998; Newman & Thornley, Citation1996). The case selection is, thus, well-suited for analysing the processes and identifying the factors that – despite many similarities and intense mutual exchange – led to different framings and crisis constructions of post-war modernist housing estates. Drawing on materials collected between 2013 and 2017, the study provides a comprehensive quantitative and qualitative discourse analysis of German and Austrian professional journals in the fields of urban planning and design from 1960 until 2015.Footnote2 Based on the theoretical framework, more than 400 articles on post-war modernist housing estates were identified, systematically recorded, categorized and analysed. Furthermore, the study builds on in-depth expert interviewsFootnote3 conducted with planning professionals in the fields of planning practice, policy and research as well as on an analysis of quantitative and qualitative data on housing estates.

The remainder of this paper is organized in four parts. Section two reviews the scholarship on post-war modernist housing estates and presents the analytical framework. Section three elaborates different framings of post-war housing estates in West Germany and Austria that emerged despite strong similarities in terms of urban design and share in overall housing stock. Accordingly, section four reconstructs how the perceived crisis was constructed differently in West Germany and Austria, revealing multi-dimensional politicization processes. Section five summarizes the central findings and provides reflections on implications for future research and planning practice.

Background and framework

Over the last decades, an extensive body of literature on post-war modernist housing has emerged. Engaging with their physical form as well as underlying ideas and concepts, these works emphasized the similarities and ubiquity of modernist, large-scale housing around the world (e.g. Rowlands et al., Citation2009; Urban, Citation2012; van Kempen et al., Citation2005; Wagenaar & Dings, Citation2004). Referred to as ‘high modernism’ (Scott, Citation1998), the housing estates of the post-war era were depicted as the ‘mass outcome’ of idealistic visions that were subverted to serve politico-economic imperatives. In many contexts these estates were subsequently labelled as failed experiments, with researchers intensively querying the reasons for this ‘failure’ (ibid, pp. 88f.; Jessen, Citation1989, pp. 573ff.).

Strong similarities and the ubiquity of post-war modernist housing around the globe meant that the growing criticism that emerged from the 1960s onwards, specific for the context of the USA and a few Western European countries, was often considered generalizable to many other contexts. Indeed, soon research took on the assumption that post-war modernist housing estates presented a problem (e.g. Skifter-Andersen, Citation2003; van Kempen et al., Citation2005). The absence of problems generally associated with housing estates in some places was seen as an exception in need of further explanation – and it was assumed that problems would sooner or later emerge. In Austria, the first comprehensive study of these estates was published in 1991, driven by the perceived fear that alarming developments in other Western European countries would soon arrive in Austria, with the ‘usual time delay’ (Czasny & Feigelfeld, Citation1991, p. 1). Similarly, research suggested that in the cities of the former Soviet Union ‘the whole belt of “new housing estates” is likely to become the slums of the early twenty-first century’ (Szelenyi, Citation1996, p. 315).

However, more recent studies rightly point out that despite their numerous similarities post-war housing estates present a highly differentiated phenomenon, both internationally (e.g. Hess et al., Citation2018; Kovács & Herfert, Citation2012; Rowlands et al., Citation2009; Urban, Citation2012) and within countries (e.g. Grossmann et al., Citation2015; Kabisch & Grossmann, Citation2013; Kemppainen et al., Citation2018; Kennett & Forrest, Citation2003). Urban (Citation2012, p. 2) identified several factors that explain the variegated outcomes and performances of the estates at neighbourhood level, including form, location, social composition and maintenance. While ‘the myth of a common destiny of post-war housing estates’ is increasingly being challenged (Grossmann et al., Citation2015, p. 144), ‘Großsiedlungs-Bashing’Footnote4 is still en vogue (Kil, Citation2017). The literature still embraces the assumption of a persistent condition of crisis and seeks to depict the ostensible or actual failures of this urban heritage. Such perspective is, however, problematic, because it distracts from an equally important question – How was the perception of a ‘crisis of post-war modernist housing’ constructed in the first place? Footnote5 This question is all the more relevant, as for example in West Germany right from the beginning, the estates were subjected to a one-sided negative evaluation, even though empirical studies demonstrated a much more differentiated picture (e.g. Siebel, Citation2005).

Only a few studies have sought to address this gap. In Germany, the scholarly focus on post-war modernist housing estates remained uninterrupted throughout the last decades (for a systematic overview see Schöller, Citation2005). This literature acknowledges that the discreditation of the estates was partly driven by exogenous political dynamics. Nevertheless, calls for a more respectful engagement with this urban heritage and for a systematic analysis of their discreditation have emerged only recently (e.g. Harnack & Stollmann, Citation2017; Haumann & Wagner-Kyora, Citation2013). Some studies trace the shifting perceptions of single housing estates (e.g. Kramper, Citation2013; Reinecke, Citation2013), while others engage with the public media discourses through an international, comparative perspective (Brailich et al., Citation2008; Glasze et al., Citation2012). The latter provide valuable insights into the variegated perceptions of large housing estates in different countries; however, they do not shed light on the questions of how these perceptions evolved over time, which actors participated in this process and how to account for the identified differences between countries.

In contrast to West German post-war housing, Austrian estates are still under-researched, with only a few comprehensive studies to date (e.g. Czasny & Feigelfeld, Citation1991; Kapeller, Citation2009; Mayer, Citation2006). Most works and edited volumes on large-scale housing estates in different countries lack Austrian examples (e.g. Haumann & Wagner-Kyora, Citation2013; Hess et al., Citation2018; Rowlands et al., Citation2009; Urban, Citation2012). This is all the more regrettable as the perception and performances of Austrian estates have the potential to challenge the hegemonic discourses about the problematic nature of modernist mass housing, dominant in Central and Western Europe.

Beyond the German and Austrian cases, the literature on housing estates is also lacking a systematic analysis of the dynamics of crisis construction, influencing factors and actor groups as well as a cross-country comparison. By reconstructing and comparing the discreditation of these estates in Austrian and West German professional debates, this paper seeks to address this gap.

Such undertaking requires an analytical framework that can enable adequate assessment of how this complex process unfolded over time. For this purpose, the paper draws on Keller’s (Citation2007) sociology of knowledge approach to discourse analysis and Hay’s (1996) concept on the discursive construction of crises. Following Hay’s work (1996, pp. 254f.), this paper understands crisis not as a condition of accumulated tensions and contradictions but as a process of transformation. Consequently, a crisis is not an objective condition or inherent feature of a situation but something that is perceived and identified, defined and constituted as such (ibid, p. 255; see also Stone, Citation1989, pp. 282, 299). Failure and crisis cannot be equated – crises represent social constructions of failure (Hay, Citation1996, p. 255). A given constellation of contradictions, failures and inherent tensions can sustain multiple conflicting and often competing narratives of crisis (ibid). A comprehensive analysis must, therefore, seek to expose how the specific framings and construction of the crisis evolved and came to dominate.

Hay’s (Citation1996) work provides a useful conceptualization of what constitutes a ‘crisis’. His approach is especially well suited to reconstruct the linguistic devices and rhetorical strategies used in narrating ‘crisis’. This paper, however, goes beyond linguistic discourse analysis in that it engages with the complex, socio-historically evolving processes of knowledge transformation and the actors involved in such processes (Keller, Citation2011, p. 63). For this purpose, the paper extends Hay’s concept on crisis by drawing on Keller’s (Citation2007, Citation2011) sociology of knowledge approach to discourse analysis. Keller (Citation2007, Citation2011) combines Berger & Luckmann’s (Citation1966) pivotal work on the social construction of knowledge with the ideas of Michel Foucault (Citation1988, Citation1989). In Keller’s (Citation2007, p. 63; 2011, p. 46; see also Foucault, Citation1988, p. 74) understanding, discourses constitute reality and knowledge in specific ways, for example, by determining what is important and unimportant, true and false, good and bad, rational and irrational, normal and abnormal. Every society constructs its own ‘order of truth’, by accepting certain crisis constructions and disregarding others (Foucault, Citation1989, p. 13), thereby creating, transforming or stabilising knowledge orders (Keller, Citation2007, p. 7). An analysis of transforming knowledge orders allows the researcher to expose not only how but also why certain constructions of crisis became dominant in particular contexts (Rose, Citation1999, p. 8).

From this perspective the remaining sections seek to answer the following questions: First, how was the crisis of post-modernist housing estates constructed – how did the knowledge orders shift from perceiving these estates as one of the great achievements of the post-war era into portraying them as a problem? Second, which factors influenced particular crisis constructions? And third, who were the main actor groups involved? Before engaging with these questions in detail, the following section will discuss the underlying principles and the built environment realities of post-war modernist housing estates in West Germany and Austria.

Post-war housing estates in West Germany and Austria: characteristics and framing

This paper focuses on large-scale, modernist housing estates built between 1950 and 1980 in West Germany and Austria, constructed based on a unified planning concept and comprising 1,000 or more dwelling units (DUS). Prominent examples include ‘Neue Vahr’ in Bremen (1957, 10,000 DUS), ‘Märkisches Viertel’ in Berlin (1963, 16,900 DUS) and ‘Ben-Gurion-Ring’ in Frankfurt (1976, 1,700 DUS) in West Germany. In Austria, well-known examples are ‘Südstadt’ in Maria Enzersdorf (1960, 1,940 DUS), ‘Großfeldsiedlung’ (1967, 6,936 DUS) and ‘Trabrenngründe’ (1975, 1,407 DUS) in Vienna. In West Germany and Austria alike, these estates were constructed with extensive public sector involvement, backed by a system of regulations (e.g. on occupancy rates, limit of rental costs etc.) and direct subsidies from the state (Czasny & Feigelfeld, Citation1991, p. 13; Kirchner, Citation2006, p. 93; Matznetter, Citation2002, p. 267). The leading providers of social housing were non-profit housing associations and, to a lesser extent, non-profit cooperatives and municipalities (Czasny & Feigelfeld, Citation1991, p. 13; Herlyn et al., Citation1987b, pp. 35f.).

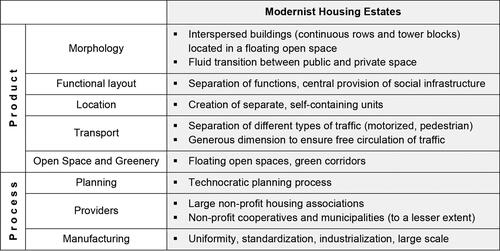

The underlying planning paradigm of functionalist modernism that shaped these estates has been researched in detail and shows overwhelming similarities in both countries (Hafner et al., Citation1998; Pfeiffer et al., Citation1993). outlines the main elements of this planning paradigm. Besides their qualitative characteristics, it is important to also note the sheer volume of modernist housing estates constructed in both countries – 268 housing estates with 711,000 DUS in West Germany and 49 housing estates with 90,000 DUS in Austria.Footnote6 showcases these numbers in relation to the overall housing stock in both countries. Two facts stand out: First, the percentage of post-war modernist housing estates in relation to the entire housing stock is almost the same in both countries. It can be assumed that this urban heritage presents an equally important and visible phenomenon in West German and Austrian cities. Second, post-war modernist housing estates make up only a small part of the entire housing stock.Footnote7 Despite this relatively minor presentence, these estates evoked intense professional and public debates – an issue that will be discussed in section four.

Figure 1. Main characteristics of post-war modernist housing estates in West Germany and Austria (based on Zupan, Citation2018).

Table 1. Dwelling units in housing estates as defined above in relation to overall housing stock.

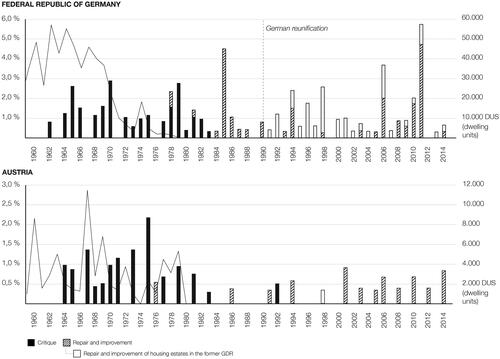

While the estates present a very similar phenomenon with regard to the underlying principles and built environment realities, they were framed differently over the last decades – and continue to be evaluated through contrasting lenses to today. The analysis revealed the following sub-discourses that shaped this process (). First, substantial criticism gained momentum from the beginning of the 1960s onwards, largely disappearing with the end of large-scale modernist housing construction during the 1980s. Discourse analysis as well as expert interviews revealed that these estates faced weaker resistance in Austria than in West Germany, where fundamental criticism was more pronounced and widespread. Some well-known endogenous shortcomings – thus issues concerning the urban model itself – like lack of infrastructure provision, mono-functionality, sterile and monotonous architecture or structural damages – were discussed in both countries alike. More far-reaching accusations – like lack of developed political organisation, social conflicts or communicative impoverishment – were, however, much more characteristic for West German debates.

Figure 2. Relevant discourses on post-war modernist housing estates in (West) German and Austrian professional journals, 1960–2015. Y-axis, left side: Percentage of thematic articles in relation to the total amount of articles published annually in the analysed journals. Y-axis, right side: Dwelling units in housing estates as defined above, recorded according to year of construction.

Second, the debate on Nachbesserung (‘repair and improvement’) and demolition of the estates, which started in the late 1970s, was relatively pronounced in West Germany and almost completely absent in Austria. In West Germany, these estates were depicted as failed experiments and mistakes (Jessen, Citation1989, p. 568; interview I, 2015; interview II, 2014; interview III, 2014; interview IV, 2015). The term Großsiedlung became one dominant label for referring to the large, modernist housing estates of the 1950s to the 1970s,Footnote8 thus sharply demarcating a distinct, finished historical phenomenon and de-emphasising housing continuities before and after (Deutscher Bundestag, Citation1988, p. 7; Herlyn et al., Citation1987a, p. 47). What is more, in the course of German reunification the large share of large-scale housing estates of the former GDR became subject of discussions and substantially intensified debates (e.g. Breuer & Hunger, Citation1992; Hegner, Citation1992; Hunger, Citation1992). In the Austrian discourse, endogenous shortcomings and the need for improvements were broadly acknowledged; however, these estates were understood as progress with regard to preceding epochs (interview XVI, 2016). What is more, Austrian discourse was keen to stress historical continuities. The term Großsiedlung is hardly used in Austrian debates, and the most commonly used term, Großwohnanlage, is not limited to post-war housing but refers to housing estates from the early 20th century to today (Czasny & Feigelfeld, Citation1991, p. 9). The 1950s–1970s modernist housing estates are hardly demarcated as a distinct historical phenomenon in Austria but rather situated within a broader, continuous line of housing provision efforts.

The politicization of post-war housing estates

The previous section highlighted that despite substantial parallels in terms of underlying ideas as well as quality and quantity, post-war modernist housing estates are framed differently in West Germany and Austria. Based on qualitative discourse analysis as well as interviews, this section reconstructs the construction of the crisis, demonstrating that the estates became a battleground where broader political questions were negotiated. This politicization can explain the different perceptions of the estates in the two countries as well as the mismatch between the considerable attention these estates provoked in professional and public debates, on the one hand, and their marginal significance for the national housing stocks, on the other. Discourse analysis revealed three dimensions that contributed to shaping crises: definitions of urbanity, housing policies, and diverging positions on socialist urban planning and design. While these dimensions are hardly separate in reality, their analytical differentiation and separate discussion in the subsequent sections serve to illustrate and explain variegated crisis constructions in West Germany and Austria.

West Germany

From the early 1960s onwards, West German housing discourse was marked by intense debates, with the harsh criticism levelled on housing estates being peppered with such pejorative terms as Verdichtungsmaschinerien (‘densification machineries’)‚ monotone Wohnsilos (‘monotonous housing silos’) or sterile Betonburgen (‘sterile concrete fortresses’). Well-known critical writings from various disciplines (Bahrdt, Citation1968, Citation1969; Jacobs, Citation1963; Mitscherlich, Citation1965; Siedler et al., Citation1964) were readily taken up in professional debates and – despite their often-exaggerated critique and harsh rhetoric – became very influential. Originating from this early criticism, West German housing estates were problematized in the following decades.

Urbanity

Discussions about how living together shall be organized in cities and which kind of urbanity is to be achieved started in the early 1960s. The ideas of Swiss sociologist Edgar Salin (Citation1960) provided the intellectual stimulus: he defined urbanity as a process of active citizenship and political participation, concluding that contemporary, modernist city-making would not allow for such urbanity to emerge. Subsequently, professional debates were characterized by a search for a path to regaining this ‘lost’ urbanity (e.g. Bahrdt, Citation1960, Citation1968; Boeddinghaus, Citation1995). Planners assumed that this could be achieved through higher building densities. Accordingly, the leitmotiv Urbanität durch Dichte (‘urbanity through density’) characterized West German housing production during the 1970s and resulted in dense housing estates (e.g. ‘Ratingen-West’ in Ratingen, 1966, 5,300 DUS; ‘Osterholz-Tenever’ in Bremen, 1968, 2,600 DUS; ‘Olympisches Dorf’ in Munich, 1968, 4,300 DUS). While intended as substantial improvements, these denser estates could not provide the desired kind of urbanity and led to even stronger criticism.

Indeed, West German discourse increasingly displayed a shift from addressing endogenous weaknesses – i.e. issues concerning the urban model and structures – to exogenous factors. From the early 1970s onward, the democratization of planning and active citizenship became subjects of political contestation. In Berlin and other cities, students’ initiatives and resistance movements opposed plans of large-scale clearances and the relocation of residents from inner-city neighbourhoods to newly built modernist housing estates (BfS, 1970; Harlander, Citation1999, pp. 308ff.; interview V, 2014). As an urban planner who was involved in these processes put it: ‘These initiatives played a pivotal role in publicly condemning the Berlin practice of large-scale clearances on a nationwide scale’ (interview VI, 2014, author’s translation). In particular, they criticized the compulsory relocation of residents from long-grown social milieus into new estates characterized by ‘disorientation, conflicts and communicative impoverishment’ (Pfeil, Citation1970, pp. 58f., author’s translation). Even though these initiatives primarily condemned the practice of large-scale clearances, they simultaneously contributed to the discreditation of modernist housing estates.

Along with this growing politicization, a narrative evolved that directly linked the practice of large-scale clearances and the production of modernist housing estates. The publishers of the influential, leftist journal Arch+, for example, depicted both practices as contemporary ‘outrages of urban restructuring’, which ‘cannot be tolerated any longer’ (Ehrlinger et al., Citation1975, p. 7, author’s translation). Critics attributed the destructive threat to both practices: in the case of large-scale clearances the destruction was caused by the factual demolition of urban structures. In the latter case, the destruction was interpreted in a more metaphorical sense, namely as denying the possibility for any kind of urbanity to emerge in these estates. Indeed, even researchers documented the perceived lack of developed political activism and organisation in post-war housing estates (Herlyn, Citation1987, p. 123).

While large-scale clearances and the relocation of residents into new housing estates were by no means common practice in West Germany, the narrative of linking the two practices – the clearing of traditional neighbourhoods and the construction of large-scale modernist housing estates – and assigning destructive potential to both became widespread. This was possible because actors from different political camps, ranging from conservatives to progressive leftist movements, participated in this discreditation process (see also Adrian, Citation1983, p. 1927). All of them supported the emergence of a rather narrow understanding of urbanity found in the pre-modernist Bürgerstadt (‘bourgeois city’). The rediscovery of the Bürgerstadt, however, simultaneously served to draw a devastating verdict of modernist urban development, which was accused of having disrupted or even destroyed the former. The influential writer Heinrich Klotz (Citation1984), for example, demanded the ‘revision of modernism’ – a claim, that consequently guided the professional lives of many thinkers and planners in West Germany. As a well-known urban planner explained: ‘My lifelong mission was to accomplish a revision of modernism, to correct mistakes, to fix the errors that earlier generations have made’ (interview I, 2015, author’s translation).

Housing policies

Vacancies and social problems arising in some estates during the 1970s paved the way for another dimension of politicization. The reasons for vacancies and social issues lay in the oversupply of housing, a subsidy system producing unfavourable price–performance ratios, and occupancy policies leading to one-sided allocations of socially vulnerable groups to certain locations (Walter & Schmidt-Bartel, Citation1986, pp. 88ff.). Nevertheless, critics rendered the built structures (co-)responsible for these challenges, an opinion that is only slowly being questioned. An expert who was actively engaged in the maintenance and improvement of post-war modernist housing structures in a planning department acknowledged that ‘only many years later we understood that the problems did not result from the built form but from social housing policies’ (interview VII, 2015). These challenges grew with the economic recession of the 1970s. The declared ‘limits of growth’ (Club of Rome 1972) provided the background for demanding an end to large-scale modernist housing (Ganser, Citation1974, p. 86; Hafner et al., Citation1998, p. 98). It was in this context that the term ‘crisis’ was first applied to economic development and extended stepwise to modernist housing production. Petzinger & Kraft (Citation1974), for example, published an article on the ‘construction crisis’, pleading for alternatives. Others (Evers, Citation1978; Gschwind, Citation1978) engaged with the crisis of modernist urban development more generally.

Even though the ‘end of mass housing’ (Herlyn et al., Citation1987b) was declared and no new large-scale modernist housing estates were built in West Germany during the 1980s, the crisis continued to deepen. Indeed, debates saw a new wave of intense discussion focused on Nachbesserungen (‘repair and improvement’), which included repair, substantial improvement and the possibility of demolishing these estates (e.g. Becker, Citation1990; Gibbins, Citation1988). Critics asked ‘why the future-oriented designs of the 1960s were likely to become the slums of tomorrow’ (Durth & Hamacher, Citation1978, p. 80, author’s translation). The professional public provided important stimuli to this debate, inter alia by organizing highly visible exhibitions (e.g. at the IBA Berlin in 1984) or by publishing special issues (e.g. Stadtbauwelt, Citation1985). By the end of the 1980s, large volumes of public moneys were being allocated to improvement programmes (Becker, Citation1990, pp. 20f.; Deutscher Bundestag, Citation1988). It was against this background that these estates were reinterpreted – namely from newly built housing estates into cost-intensive and long-term areas of redevelopment (Herlyn et al., Citation1987b, p. 49). Such reinterpretation went hand in hand with depicting them as an error and failed experiment. The early 1980s scandal with the biggest housing association Neue Heimat additionally fanned this negative perception, rendering these estates as outcomes of nepotism, profiteering and heavy mismanagement (Schöller, Citation2005, p. 9).

Despite empirical studies that warned against exaggerations, sweeping condemnations or the generalization of problems that affected merely a handful of estates (e.g. Walter & Schmidt-Bartel, Citation1986, p. 90), it was too late to salvage the image of the modernist housing estate in West Germany. By then the detected endogenous weaknesses – lack of infrastructure, monotonous appearances and mono-functionality – had already blended together with exogenous factors – in particular the negative effects of social housing policies as well as the broader economic crisis. Social housing policies and modernist planning were fused together in the single notion of ‘mass housing’, which was increasingly stigmatized as housing for the worst off in society. It became common practice to associate Großsiedlungen with ‘vacancies and problems finding tenants, social problems, neighbourhood problems and violence’, as highlighted by a politician and representative of the housing industry (interview VIII, 2015, author’s translation).

The built structures turned into a battleground for negotiating housing policies, which led to exaggerated critique – far beyond issues of urban planning and design. Critics considered modernist housing estates as the direct expression and most forthright built manifestation of a welfare approach to housing that could and should no longer be sustained (interview IX, 2015; interview IV, 2015; Schöller, Citation2005). Such discreditation was facilitated by a trend of economic liberalization. Indeed, social housing was never intended as a long-term strategy in West Germany but merely as a temporal fix to overcome periods of hardship (von Beyme, Citation1999, p. 133). Thus, already from the 1960s onwards, policies of economic liberalization were being implemented: the reduction of public spending, an accelerated replacement of supply-side (‘object’) subsidies by demand-side (‘subject’) subsidies, an extension of tax benefits for private developers, and the abolishment of the non-profit status of housing associations (ibid: 97, 131; Kirchner, Citation2006, pp. 104–113; Wukovitsch, Citation2009, p. 62).

However, the profound discreditation also rested on the fact that actors of different political leanings were involved in constructing the crisis. First and foremost, proponents of economic liberalization advocated for freeing the housing market from strong state interference and made use of the built manifestation’s shortcomings to bolster their arguments. Also critical leftist initiatives and movements contributed to this process, by accusing the local state of pursuing capitalist interests and demanding reduced state interference (e.g. BfS, 1970, p. 229).

Socialist urban planning and design

During the Cold War urban planning and design became a means of political positioning and a source of legitimization in the competition between the systems in East and West Germany (Großbölting & Schmidt, 2015, p. XVII). Such positioning also influenced the respective crisis constructions of post-war modernist housing estates.

Reflecting the Cold War and the division of Germany, West German professional debates generally showed little engagement with urban planning and design from ‘the East’ during the 1950s and 1960s. This hardly changed when détente, a phase of relaxation of political tensions during Cold War, allowed for enhanced exchange and travel during the 1970s. Despite individual efforts to initiate a non-polemic and ideology-free discussion (Hillebrecht, Citation1971, p. 105), urban planning and design in the GDR and other socialist countries attracted little attention in West German professional debates (Machule & Stimmann, Citation1981, p. 383). It would be wrong, however, to conclude that it played no role at all. Instead, it was constructed as an antipode. This was probably most clearly reflected in the flagship projects emerging in East and West Berlin during the 1950s. East Berlin saw the construction start of the ‘Stalinallee’, which served as a role model for socialist urbanism. The project was characterized by a rejection of ‘international’ modernism and relied on historical and national references, following the proclamation ‘national in form, socialist in content’ (Betker, Citation2015, p. 4; Düwel, Citation2004, p. 54). At the same time, the international building exhibition Interbau took place in West Berlin in 1957. One of its showcases was the housing estate ‘Hansaviertel’ (1955, 1,300 DUS). Designed by well-known planners and following international, modernist principles of city planning, it was publicly declared a counter-model to socialist ‘traditionalist’ developments (Großbölting, 2015, p. 36; Harlander, Citation1999, p. 279).

While this desire for differentiation spurred internationalist, modernist principles of urban planning and design in West Germany, the situation profoundly changed when the proclamation of ‘national in form, socialist in content’ was replaced by the demand ‘faster, better and cheaper’ in East Germany and other socialist countries. Confronted with an enormous housing shortage and de-Stalinization, Nikita Khrushchev held his famous 1954 speech, outlining the measures to be taken. Consequently, socialist planning saw a return to ‘international’ modernist principles, with an accompanying upsurge in industrialized, standardized building methods (Düwel, Citation2004, p. 57). The new large-scale housing projects showed many similarities with ‘the West’ in terms of urban planning principles and appearances. This shift did not pass unnoticed in West Germany. West German debates reflected on the similarities between socialist and capitalist housing production and discussed possible explanations (Hillebrecht, Citation1971, p. 105; Posener, Citation1975, p. 17; Schneider, Citation1971, pp. 134–137). In general, socialist developments were seen as trailing behind and merely replicating Western models. Accordingly, the West German planning profession did not perceive these countries as progressive or as potential role models.

While being constructed in East and West alike, industrialized panel housing was stepwise equated with the ‘Eastern bloc’ and as such increasingly rejected in West Germany (interview X, 2015; Großbölting, 2015, p. 41). But this was not merely a rejection of these urban planning and design principles – the denunciation of the associated housing policies was even more important. Indeed, panel houses were rendered as the built manifestations of the Soviet Union’s ideal of collectivization and the abolishment of private property (Lücke, Citation1960, p. 570). From the 1960s onwards, conservative political camps in West Germany strongly advocated against social housing and for private ownership (Großbölting, 2015, p. 38). In the words of Paul Lücke (Citation1960, quoted in Spiegel, 1969, p. 50, author’s translation), the minister for construction, this step was necessary ‘to confront the political threat posed by the collective powers of the East’. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, German debates (e.g. Hoffmann-Axthelm, Citation1990, p. 110) followed the internationally evolving narrative of ‘the end of history’ (Fukuyama, Citation1992). The collapse of state socialism across Eastern Europe was interpreted as a proof of the unrivalled superiority of capitalism and the ‘triumph of the free market’ (Büdenbender, Citation2017, p. 20; Rose, Citation1999, p. 61).

In summary, an important shift of knowledge orders took place in West Germany from the 1960s onwards – from perceiving large housing estates as one of the great achievements of the post-war era to portraying them as a societal problem and even a mistake. In the course of this process, endogenous weaknesses and dysfunctions were combined with external pressures, facilitating a profound discreditation. Indeed, a threefold politicization reinforced the crisis of post-war modernist housing in West Germany. First, the estates were depicted as a destructive practice as the possibility for any kind of urbanity to emerge in these estates was denied. Second, negative socio-spatial effects resulting from social housing policies were attributed to the built environment, rendering these estates (co-)responsible for the emerging challenges. Housing policies and built forms were reduced to the single notion of ‘mass housing’, which was increasingly stigmatized as housing for the worst off in society. Finally, reflecting the Cold War and German division, socialist planning practice and housing policies were depicted as an antipode, spurring the dismissal of large-scale modernist housing.

Austria

The Austrian discourse was generally more moderate than in West Germany. While pejorative terms like Schlafstädte (‘dormitory towns’) or monotone Zeilensiedlungen (‘monotonous slab estates’) were used, the estates also received almost endearing labels – Emmentaler-Stil (‘Emmental-style’) or Mannerschnitten (a popular Austrian confectionary). This is not to say that fundamental criticism was absent. On the contrary, the ideas of Bahrdt, Mitscherlich or Jacobs were discussed and similar arguments developed by Austrian writers (Feuerstein, Citation1958; Hundertwasser, Citation1958; Rainer & Prachensky, Citation1958; Sedlmayr, Citation1965). However, they were less influential in professional debates and generated fierce controversies, with strong opponents bemoaning the exaggerated criticism (e.g. Freisitzer, Citation1979; Slavik, Citation1979). Indeed, many critical, leftist thinkers and planners perceived such criticism as bourgeois (interview XI, 2015; interview XII, 2015).

Urbanity

Discussions about urbanity started in Austria’s professional community in the early 1960s. The debates also affected planning practice, leading to a shift toward dense and complex housing ensembles (e.g. ‘Großfeldsiedlung’, 1967, 6,936 DUS and ‘Rennbahnweg’, 1975, 2,407 DUS in Vienna, parts of ‘Siedlung Oed’, 1960, 2,127 DUS and ‘Niedernhardt’, 1964, 1,011 DUS in Linz). While the built realities show overwhelming similarities with West Germany at that time, the professional negotiations about the urbanity of these estates were fundamentally different. The influential planner, architect and writer Wilhelm Kainrath (Citation1971, p. 14, author’s translation), for example, critically engaged with narrow, ‘bourgeois’ conceptualizations of urbanity and pointed to the dangers of elevating such understanding when commenting on re-urbanization concepts for the city of Vienna:

I cannot imagine that I will see new faces there. The same sonorous ‘Kommerzialräte’,Footnote9 nimble advocates, jovial professors, the same snobbish ladies…. What shall attract the workers, small employers, the frugal housewives, the children and pensioners, the migrant workers? (…) This is just a refurbishment of the ‘Bourgeoisie’s front parlour’ – servants more than ever just come in when needed for serving.

This quote reflects a dominant line of thinking in Austrian debates, which did not limit ‘urbanity’ to certain, pre-modernist urban structures and critically engaged with bourgeois conceptualizations of urbanity. Instead, a broad understanding of ‘multiple urbanities’ evolved, as reflected in different pre-modernist as well as modernist and post-modernist urban environments (e.g. Swoboda, in CitationTabor, 1992). Such understanding of multiple urbanities shaped the perception of post-war modernist housing estates in important ways. First, post-war modernist housing estates were not depicted as anti-urban, and the possibility for urbanity to emerge in these structures was not denied. Second, the relation between inner city renewal and the construction of modernist housing estates was framed in a positive way: ‘The construction of these estates was the central precondition for making urban renewal happen: they enabled it’, as an expert on urban development in Vienna explained (interview XI, 2015, author’s translation, see also interview XII, 2015). Finally, in contrast to substandard housing in the city centres, these new estates substantially improved living conditions and were highly valued by their residents (e.g. Bandel, Citation1983; Slavik, Citation1979).

Various explanations can be put forward to this difference in framing. First and foremost, it was spearheaded by the leftist actors’ refusal to accept a narrow definition of urbanity and exaggerated criticism. In addition, large-scale clearances were almost completely absent in Austrian cities, and comprehensive urban renewal programmes started later than in West Germany (Hafner et al., Citation1998, p. 161). As a result, fighting for the preservation of these structures did not appear as necessary. Indeed, a re-evaluation of pre-modernist, Wilhelminian urban structures was less pronounced in Austrian discourse at that time. Instead, the professional community was much more concerned with the rediscovery of the social and urban heritage of ‘Red Vienna’ and the architecture and social achievements of the early modernist movement (interview XIII, 2015; interview XIV, 2015; Koch, Citation1984; Mang, Citation1978).

Housing policies

In contrast to the dominant narrative in West Germany and other countries (Hafner et al., Citation1998, p. 98), Austrian discourse did not chiefly associate the 1970s economic recession with large-scale modernist housing, which continued to be built with high intensity until the end of the 1970s.Footnote10 But even when production rates went down in the 1980s, housing estates in Austria offered sceptics fewer causes for criticism. Vacancy rates were low, and it was assumed that there were fewer social problems than in post-war modernist housing estates in other countries (the empirical data was and still is lacking) (Czasny & Feigelfeld, Citation1991, pp. 299–303; interview XV, 2015). Scholars identified several explaining factors (ibid.), ascribing the low vacancy rates to the fact that there was no oversupply of housing, to funding schemes that prevented disproportionate increases in rental costs, and to relatively few alternatives on the housing market. The lower incidence of social problems was mainly explained by the fact that access to social housing was open for broad segments of the population, thus facilitating a diverse social mix within these structures. Another important fact was that social rental housing was largely not accessible to foreigners at that time.Footnote11 Notwithstanding the long shadow this exclusion casts on the often-celebrated Austrian social housing policies, it forestalled the ‘explosive mix of unemployment, poverty and national conflicts’ seen in other countries (Czasny & Feigelfeld, Citation1991, p. 304, author’s translation).

Against this background, professional debates on post-war modernist housing basically ended in the 1980s. Neither the need for comprehensive publicly funded improvement programmes nor calls for demolitions were articulated. This is not to say that there were no improvements at all. Many Austrian estates have been modernized and continue to be upgraded. The few articles published on renovations and improvements of these estates (e.g. Kapeller, Citation2009; Löffler, Citation2001) do not depict this urban heritage as particularly problematic or as requiring more maintenance than others.

Social housing policies and the relatively minor negative effects are important factors that explain why housing estates in Austria did not experience the same level of stigmatization as in Germany and other Western countries. This was also facilitated by the fact that the central pillars of social housing – including a focus on supply-side (‘object’) subsidies or a strong non-profit sector – have been maintained in Austria until today (Kirchner, Citation2006, p. 271; Wukovitsch, Citation2009, p. 63) – ‘the whole armoury of post-war social housing is still in place’ (Matznetter, Citation2002, p. 267).Footnote12 Still, social housing policies were subject to intense disputes. Proponents of economic liberalization bemoaned that large parts of housing were withdrawn from the ‘free market’ and promoted both a break with modernist planning principles and a liberalization of housing policies (interview XII, 2015). Such voices were, however, confronted by a strong social democratic political base, non-profit housing associations as well as municipalities, all advocating for a continuation of welfare housing policies. They understood the fierce criticism not merely as an assault on the built structures and the underlying planning principles, but on the very concept of social housing (interview XI, 2015; interview XII, 2015):

The conservative, bourgeois critique started in the 1960s. They did not like these estates, because the buildings had no decorated façade. The true reason was, of course, different: They were against social housing because they interpreted it as an affront to withdraw housing from the free market. (interview XII, 2015)

Socialist urban planning and design

Finally, the analysis revealed a different position with regard to socialist urban planning, which acted as an important source of inspiration in Austria. On the one hand, this development can be understood as emerging out of the historically rooted strong links with Eastern Europe. On the other, it rested on Austria’s neutrality and ‘exit’ from the Cold War after 1955, which – in the words of Khrushchev – made it a ‘prime example of peaceful coexistence’ (Müller, Citation2008).

Experts from socialist Europe were regularly invited to juries of important town planning competitions, to professional events and as visiting professors. Relations were also characterized by an intense exchange of ideas. Apart from projects in Great Britain, France, Scandinavia and West Germany, examples from socialist countries received broad attention in Austria’s professional community (see Breit, Citation1967; Heim, Citation1968; Gaberščik, Citation1969; Zupanjevac, Citation1974). There is also evidence of direct idea transfers, for example, the procedure for carrying out open idea competitions. In the 1960s, the city of Bratislava held such a competition for the development of ‘Petržalka’, with several Austrian firms participating (Breit, Citation1967). Directly referring to the Petržalka process, this novel procedure was applied for the first time in Austria in the international competition ‘Wien Süd’, a planned satellite town for more than 60,000 inhabitants (aA, 1971).

Austrian journals also served as platforms for ‘alternative’ discourses, including those from socialist countries. The journal Raumforschung und Raumplanung, for example, published an article by Joachim Bach (Citation1986, pp. 20f.) – professor of urban planning in Weimar – in which he critically engaged with the growing critique of new housing estates in the GDR: ‘With a delay of about a decade, the GDR has recently started following the international trend of condemning large-scale housing construction as a societal and planning mistake without carrying out sound sociological and historical research’. Such ‘alternative’ opinions showed some common features with Austrian discourse, where unfounded or excessive criticism was also questioned and exaggerations were largely condemned. The same holds true for debates about ‘urbanity’. While this leitmotiv was hardly taken up in East Germany, due to its bourgeois connotation (Betker, Citation2015, pp. 18ff.), the concept became influential in Austrian professional debates, but – as we have seen in the last section – not without critically addressing and deconstructing its bourgeois foundations.

These developments underline that there was no trend of conscious distancing or positioning Austria’s planning tradition vis-á-vis the capitalist West or socialist East. And, while the dissolution of the Soviet Union spurred ‘free market’ narratives in West Germany, Austrian debates – especially in the ‘fortress Red Vienna’ – inspired different reactions. Many authors, among them the prominent thinkers Kohoutek & Pirhofer (Citation1991, p. 10, author’s translation), still advocated for a continuation of strong state intervention in housing:

If with the provisional or ultimate end of communism, of socialism (…) every remaining notion of ‘the social’, ‘the common’, ‘the communities’, ‘the collective’ and of a non-market and media-structured public incrementally ceases to exist – and if the rather simple, almost primitive principle of commodity exchange and markets has ultimately lost every critical theoretical context, then we would have to take a final leave from communal housing in its historic and contemporary form in Vienna. For many reasons this is not the case.

In summary, post-war modernist housing estates experienced a certain level of problematization in Austria from the 1960s onwards, and by the 1980s it was broadly acknowledged that improvements to the urban model were necessary. However, by and large the perception of ‘crisis’ remained focused on endogenous weaknesses, due to the following factors: First, an understanding of multiple urbanities evolved and modernist housing estates were not depicted as anti-urban areas. Second, the negative effects of social housing policies were limited, and the central pillars of social housing were maintained, helping avoid their discreditation in terms of housing policies. Finally, Austrian neutrality coupled with historically rooted close relations with Eastern Europe allowed for intense exchanges with and learning from socialist countries.

Conclusion

This paper engaged with the crisis of post-war modernist housing estates in West Germany and Austria. An analytical framework based on Keller’s (Citation2007) sociology of knowledge approach to discourse analysis and Hay’s (1996) work on crisis construction was used to foreground the procedural and political dimensions of the crisis. From this perspective, the article demonstrated how what was initially perceived to be a great achievement of the post-war era subsequently became problematized in both countries – with marked and important differences. In West Germany, critique was quantitatively and qualitatively more pronounced. The estates were rendered as a failure and mistake, clearly demarcating them from housing constructed in other epochs. While the discourse in Austria did not ignore their deficiencies, the estates were understood as a progression from previous epochs and depicted as an integral part of the unbroken history of housing provision.

The paper further demonstrated that these differences cannot be solely explained by differences in the housing stock. The estates were built according to the same underlying principles of modernist city planning and show overwhelming similarities in terms of their qualitative realization and quantitative significance. Instead, the paper heighted how the estates became a battleground for negotiating broader political questions, resulting in their variegated politicization, and foregrounded three key dimensions that shaped this process.

First, the evolving conceptualizations of urbanity influenced their respective processes of crisis construction in diverging ways. While ‘urbanity’ became an important leitmotiv for urban planning and design in both countries, it was conceived differently. In West Germany a narrow, ‘bourgeois’ understanding of urbanity came to dominate, and modernist housing estates were not considered conducive to bringing about this urbanity. The construction of these estates was depicted as a destructive practice with anti-urban effects, and a ‘revision of modernism’ was demanded. In Austria, an understanding of multiple, modernist as well as pre-modernist urbanities emerged. Accordingly, post-war modernist housing estates were not depicted as anti-urban areas. What is more, these estates were perceived as enablers of further urban development.

Second, while the social housing policies that gave birth to the estates show many similarities in both countries, important differences shaped the dynamics of crisis constructions. Taken together with the diverging paths in housing policies from the 1960s onwards, they also influenced the politicizations of post-war modernist estates. In West Germany, the negative effects of social housing policies were linked to a critique of endogenous factors of the urban model. Despite empirical studies that warned against exaggerations, sweeping condemnations or the generalization of problems that affected a handful of estates, the built structures were still rendered co-responsible for these challenges. Embedded in a trend of economic liberalization, social housing policies and built forms were subsumed under the notion of ‘mass housing’, which was stigmatized as housing for the worst off in society. In Austria, these estates did not experience higher vacancy rates than other urban structures and the social problems were perceived as less serious than in other countries. Thus, efforts of problematizing these estates by referring to weaknesses of social housing policies had little success. Furthermore, the continuation of social housing policies hindered the critiques of these estates from dominating the discourse.

Finally, the different geopolitical positions of both countries – the Cold War and German division, on the one hand, and Austrian neutrality coupled with historically rooted deep relations with Eastern Europe, on the other – were reflected in the respective professional discourses and contributed to different problematizations. West German debates showed a tendency towards divergence from and denigration of socialist planning concepts and policies. When industrialized ‘mass housing’ became common practice in East and West alike, it spurred the discreditation of modernist housing estates. In Austria, an intense exchange of ideas, knowledge and experts flourished throughout the period. The analysis also revealed some common features in discourses, for example, regarding a critical stance towards the exaggerated critique of modernist housing estates or towards ‘bourgeois’ conceptualizations of urbanity.

Differences in social housing policies, the unique evolving conceptualizations of urbanity as well as their respective geopolitical positions influenced different crisis constructions in West Germany and Austria. Nevertheless, the exact outcomes of crisis constructions were contingent. The analysis revealed a highly complex process, in which certain attributes were ascribed to these structures, different understandings were negotiated, and multiple narratives were spread. Thereby, it was not necessarily the narratives that reflected the common practices or knowledge gained through systematic empirical studies that became the most influential. Different political actor groups were involved in shaping the crisis and played an important role in its country-specific manifestations. In West Germany, a broad spectrum of political groups with different ideologies and in pursuit of diverging goals – ranging from supporters of economic liberalization to critical leftist movements – were involved in crisis construction and allowed certain narratives to become dominant. Due to this broad ‘opposing coalition’, post-war modernist housing estates were discredited so rapidly, profoundly and on such broad scale. In Austria, in contrast, fierce criticism was opposed by a strong social democratic political base, which defended not so much the current planning paradigm of modernism but rather the welfare approach to housing policies. What is more, the profound critique of strong state institutions and speculative, autocratic urban development, brought forward in West Germany by critical leftist movements, was less pronounced in Austria.

While these estates show overwhelming similarities at first glance, they actually present different socio-political phenomena in West Germany and Austria, respectively. This finding reminds us to be cautious about transfers of problematizations and discreditation discourses to other contexts. The paper confirms the finding that ‘design is not to blame’ (Urban, Citation2012, p. 2) for the mixed achievements of these estates and takes a step beyond. The findings show that the procedural and political dimensions of crisis production have to be put in centre focus, to adequately understand different problematizations and performances of the built environment. By attempting to systematically disentangle built form and political factors, the analysis revealed the multidimensional politicization process that led to an exaggerated discreditation of these estates in West Germany. This insight has highly relevant implications for the future of these estates. The discreditation of the estates continues to affect their image and thus their prospective development paths today, and their chastising as a mistake and failed experiment still influences contemporary housing production. In Germany we observe a continuing uncertainty within the planning community and a fear of experimenting with large-scale housing production. A prevailing assumption is that ‘you cannot solve housing shortages through mass housing. If you do so you, you produce the ghettos of tomorrow’ (interview VIII, 2015, author’s translation). Given the contemporary housing shortage, it is necessary to reflect on and to acknowledge the contingency and the specific political climate that birthed the respective crises. The disentanglement between the built form and politics, therefore, presents an important step to opening up and legitimizing new perspectives and possibilities for future mass housing in European cities.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Mirjam Büdenbender for providing constructive criticism and valuable comments at the various stages of this article. I want to thank the InnoPlan research group and especially Johann Jessen for their support. I am also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Daniela Zupan

Daniela Zupan is an Assistant Professor for European Cities and Urban Heritage at the Institute for European Urban Studies at Bauhaus-Universität Weimar. Her research interests include urban planning and design concepts, housing, neoliberal urbanism and post-socialist urban transformations.

Notes

1 Due to limited resources the analysis was limited to Austria and the Federal Republic of Germany and does not cover the housing developments under the German Democratic Republic.

2 The journals were selected according to their relevance and potential to represent the fields of practice, policy and research. The following journals were analysed for the German context: Stadtbauwelt, Bundesbaublatt, Informationen zur Raumentwicklung, Archiv für Kommunalwissenschaften, and Arch+. For the Austrian context the following journals were used: Architektur aktuell, Forum, Perspektiven, and Berichte zur Raumforschung und Raumplanung. Due to limited resources, public media was not included in the analysis (for a recent study on the role of public media see Kearns et al., Citation2013).

3 In total, 47 interviews were conducted between May 2014 and April 2016, with 16 interviews quoted in this paper: Interview I: urban planner and designer, Berlin, 9 January 2015; interview II: intellectual and publicist, Berlin, 24 October 2014; interview III: urban planner and designer, Stuttgart, 24 June 2014; interview IV: key figure city administration, Frankfurt, 18 February 2015; interview V: researcher, Berlin, 23 October 2014; interview VI: urban planner, Berlin, 24 October 2014; interview VII: local politician, Hamburg, 29 June 2015; interview VIII: representative of the housing industry and politician, Hamburg, 26 June 2015; interview IX: architect and urban planner, city administration, Berlin, 10 January 2015; interview X: urban planner within city administration, Hamburg, 29 June 2015; interview XI: intellectual and publicist, Vienna, 25 November 2015; interview XII: architect and urban historian, Vienna, 26 November 2015; interview XIII: politically active architect and publicist, Vienna, 30 October 2015; interview XIV: architect, researcher and publicist, Vienna, 11 December 2015; interview XV: key figure in city administration, Vienna, 26 November 2015; interview XVI: representative of the housing industry, Linz, 04 March 2016.

4 In Germany these estates are often called Großsiedlungen (‘large housing estates’), a term that was unfamiliar to me, despite coming from the same language area.

5 Goetz (Citation2013) and Flanagan (Citation2018) use discourse analysis to engage with the discreditation of public housing. They do, however, specifically focus on housing policies.

6 Data was collected and compiled from different sources, including Czasny & Feigelfeld (Citation1991), compilations of housing estates published for different cities, municipal and architectural online platforms.

7 In other European countries (especially in Eastern Europe), a substantial share of housing units is located in such neighbourhoods (Hess et al., Citation2018, p. 13). In cities like Moscow, for example, post-war modernist housing dominates and defines the cityscape (Gunko et al., Citation2018, p. 290).

8 Other terms, each of which having a slightly different connotation, include Schlafsiedlung (‘sleeping district’), Sozialwohnungsbau (‘social housing’), Massenwohnungsbau (‘mass housing’) or Plattenbauten (‘prefabricated slab buildings’).

9 ‘Kommerzialrat’ is a title that is awarded to outstanding businesspersons in Austria.

10 The economic policy under Bruno Kreisky, known as ‘Austro-Keynesianism’, and his approach of deficit spending is considered important in this regard (Butscheck, 2011, pp. 346ff.).

11 Indeed, restrictions in this regard have only recently been relaxed due to guidelines set by the European Union (News, Citation2006; Der Standard, Citation2006).

12 Nevertheless, Austrian housing policies have experienced a certain level of economic liberalization from the 1960s onwards (Matznetter, Citation1991), particularly intensified in recent decades (see Jäger, Citation2006; Kadi, Citation2015).

References

- aA – Architektur Aktuell (1971) Wettbewerb Wien Süd, Architektur Aktuell, 24, pp. 17–24.

- Adrian, H. (1983) 1968 und die Folgen: Auf dem Weg zu Städtebauschulen?, Stadtbauwelt, 80, pp. 314–333.

- Bach, J. (1986) Städtebau im Ballungsgebiet – Probleme des Wohnungsbaues in der DDR am Beispiel des Bezirkes und der Stadt Halle, Raumforschung und Raumplanung, 4, pp. 14–23.

- Bahrdt, H. P. (1960) Nachbarschaft oder Urbanität, Bauwelt, 51/52, pp. 1467–1477.

- Bahrdt, H. P. (1968) Humaner Städtebau. Überlegungen zur Wohnungspolitik und Stadtplanung für eine nahe Zukunft (Hamburg, Germany: Wegner).

- Bahrdt, H. P. (1969) Die moderne Großstadt. Soziologische Überlegungen zum Städtebau, 1st 1961 (Hamburg, Germany: Wegner).

- Bandel, H. (1983) 60 Jahre kommunaler Wohnhausbau, Aufbau, 4, pp. 156–173.

- Becker, H. (1990) Neubauerneuerung. Vom Rückbau zur Nachverdichtung (Berlin, Germany: DifU).

- Berger, P. & Luckmann, T. (1966) The social construction of reality (Garden City, NY: Anchor Books).

- Betker, F. (2015) Ließ der Sozialismus Raum für Urbanität? Grundsätze, Leitbilder, Institutionen und Resultate im Städtebau der DDR (1945–1989), in: T. Großböltling & R. Schmidt (Eds) Gedachte Stadt – Gebaute Stadt. Urbanität in der deutsch-deutschen Systemkonkurrenz 1945–1990, pp. 1–28 (Köln, Germany: Böhlau).

- BfS – Büro für Stadtsanierung und soziale Arbeit Berlin-Kreuzberg (Ed) (1970) Sanierung - für wen? Gegen Sozialstaatsopportunismus und Konzernplanung (Berlin, Germany: BfS).

- Boeddinghaus, G. (Ed) (1995) Gesellschaft durch Dichte. Kritische Initiativen zu einem neuen Leitbild für Planung und Städtebau 1963/1964 (Braunschweig, Wiesbaden: Bauwelt Fundamente).

- Brailich, A., Germes, M., Schirmel, H., Glasze, G. & Pütz, R. (2008) Die diskursive Konstitution von Großwohnsiedlungen in Deutschland, Frankreich und Polen, Europa Regional, 16, pp. 113–128.

- Breit, R. (1967) Die Vielfalt städtebaulicher Gestaltungsmöglichkeiten, Wettbewerb Bratislava-Petrzalka, Aufbau, 9/10, pp. 388–399.

- Breuer, B. & Hunger, B. (1992) Städtebauliche Entwicklung großer Neubaugebiete in den fünf neuen Bundesländern und Berlin-Ost, Informationen zur Raumentwicklung, 6, pp. 429–445.

- Büdenbender, M. (2017) New Spaces of Capital: the Real Estate/Financial Complex in Russia and Poland. (Thesis PhD, KU Leuven).

- Butschek, F. (2011) Österreichische Wirtschaftsgeschichte. Von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart (Wien, Austria: Böhlau).

- Czasny, K. & Feigelfeld, H. (1991) Großwohnanlagen in Österreich. Zustand, Nachbesserung, Perspektiven (Wien, Austria: Institut für Stadtforschung).

- Der Spiegel (1969) Es bröckelt, Der Spiegel, 6, pp. 38–63.

- Der Standard (2006) Wiener Gemeindebau schon seit 1. Jänner auch für Ausländer geöffnet. Available at http://derstandard.at/2294757/Wiener-Gemeindewohnungen-schon-seit-1-Jaenner-auch-fuer-Auslaender-geoeffnet (accessed 07 September 2016).

- Deutscher Bundestag (Ed) (1988) Städtebaulicher Bericht der Bundesregierung. Neubausiedlungen der 60er und 70er Jahre. Probleme und Lösungsansätze, Drucksache 11/2568. Available at http://dip21.bundestag.de/dip21/btd/11/025/1102568.pdf (accessed 09 September 2016).

- Durth, W. & Hamacher, G. (1978) Wohnen vor der Stadt, Arch+, 40/41, pp. 80–81.

- Düwel, J. (2004) ‘Wir sind das Bauvolk’, in: C. Wagenaar & M. Dings (Eds) Ideals in Concrete. Exploring Central and Eastern Europe, pp 53–58 (Rotterdam, the Netherlands: NAi Publishers).

- Ehrlinger, W., Evers, A., Feldtkeller, C., Fester, M., Kraft, S., Kuhnert, N. & Pampe, J. (1975) Editorial: Tendenzwende?, Arch+, 27, pp. 1–11.

- Evers, A. (1978) Stadtentwicklung in der Krise – Eine Debatte, die noch nicht begonnen hat, Arch+, 38, pp. 2–3.

- Feuerstein, G. (1958) Thesen zu einer inzidenten Architektur, in: G. Feuerstein (Ed) (1988) Visionäre Architektur, pp 51–54 (Berlin, Germany: Ernst).

- Flanagan, K. (2018) Problem families’ in public housing: discourse, commentary and (dis)order, Housing Studies, 33, pp. 684–707.

- Foucault, M. (1988) Archäologie des Wissens (Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp).

- Foucault, M. (1989) Der Wille zum Wissen (Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp).

- Freisitzer, K. (1979) Einflüsse von Planungsideologien auf die Stadtentwicklung, Berichte zur Raumforschung und Raumordnung, 2, pp. 3–10. /pp.

- Fukuyama, F. (1992) The End of History and the Last Man (London, UK: Hamish Hamilton).

- Gaberščik, B. (1969) 25 Jahre Stadtentwicklung Ljubljana, Berichte zur Raumforschung und Raumordnung, 2, pp. 17–28.

- Ganser, K. (1974) Zur Lage, Stadtbauwelt, 42, pp. 86.

- Gibbins, O. (1988) Großsiedlungen: Bestandspflege, Weiterentwicklung (München, Germany: Callwey).

- Glasze, G., Pütz, R., Germes, M., Schirmel, H. & Brailich, A. (2012) The same but not the same: the discursive constitution of large housing estates in Germany, France, and Poland, Urban Geography, 33, pp. 1192–1221.

- Goetz, E. G. (2013) The audacity of HOPE VI: discourse and dismantling of public housing, Cities, 35, pp. 342–348.

- Großböltling, T. (2015) Der Osten im Westen? Bundesrepublikanische Praktiken urbanen Planens und Bauens in Abgrenzung und in Verflechtung zur DDR, in: T. Großböltling & R. Schmidt (Eds) Gedachte Stadt – Gebaute Stadt. Urbanität in der deutsch-deutschen Systemkonkurrenz 1945–1990, pp. 20–43 (Köln, Germany: Böhlau).

- Großböltling, T. & Schmidt, R. (2015) Gedachte Stadt – Gebaute Stadt. Urbanität in der deutsch-deutschen Systemkonkurrenz 1945–1990, in: T. Großböltling & R. Schmidt (Eds) Gedachte Stadt – Gebaute Stadt. Urbanität in der deutsch-deutschen Systemkonkurrenz 1945–1990, pp. XV–XXVI (Köln, Germany: Böhlau).

- Grossmann, K., Kabisch, N. & Kabisch, S. (2015) Understanding the social development of a post-socialist large housing estate: the case of Leipzig-Grünau in Eastern Germany in long-term perspective, European Urban and Regional Studies, 24, pp. 142–161.

- Gschwind, F. (1978) Wohnen in der Stadt, Über das Krankheitsbild der städtischen Krise und einige Therapievorschläge, Arch, +, 38, pp. 4–10.

- Gunko, M., Bogacheva, P., Medvedev, A. & Kashnitsky, I. (2018) Path-dependent development of mass housing in Moscow, Russia, in: Hess, D. B., Tammaru, T. & van Ham, M. (Eds) Housing estates in Europe. Poverty, ethnic segregation and policy challenges, pp. 289–311 (Cham, Switzerland: Springer).

- Hafner, T., Wohn, B. & Rebholz-Chaves, K. (1998) Wohnsiedlungen. Entwürfe. Typen, Erfahrungen aus Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz (Basel, Switzerland: Birkhäuser).

- Harlander, T. (1999) Wohnen und Stadtentwicklung in der Bundesrepublik, in: I. Flagge (Ed) Geschichte des Wohnens. Band 5. 1945 bis heute, pp. 233–417 (Stuttgart, Germany: Deutsche Verlagsanstalt).

- Harnack, M. & Stollmann, J. (Eds) (2017) Identifikationsräume. Potenziale und Qualität großer Wohnsiedlungen (Berlin, Germany: Universitätsverlag TU Berlin).

- Haumann, S. & Wagner-Kyora, G. (2013) Westeuropäische Großsiedlungen – Sozialkritik Und Raumerfahrung, Informationen zur modernen Stadtgeschichte, 1, pp. 6–12.

- Hay, C. (1996) Narrating crisis: the discursive construction of the winter of discontent, Sociology, 30, pp. 253–277.

- Hegner, H. (1992) Neue Bundesländer. Sanierung industriell errichteter Wohngebäude, Bundesbaublatt, 11, pp. 839–844.

- Heim, E. (1968) Wohnungsbau und Wohnsiedlungsbau in Budapest, Aufbau, 7, pp. 250–259.

- Herlyn, U., von Saldern, A. & Tessin, W. (Eds) (1987a) Neubausiedlungen der 20er und 60er Jahre. Ein historisch-soziologischer Vergleich (Frankfurt am Main, New York: Campus).

- Herlyn, U. (1987) Lebensbedingungen und Lebenschancen in den Großsiedlungen der 60er und 70er Jahre, in: U. Herlyn, A. von Saldern & W. Tessin (Eds) Neubausiedlungen der 20er und 60er Jahre. Ein historisch-soziologischer Vergleich, pp. 102–126 (Frankfurt am Main, New York: Campus).

- Herlyn, U., von Saldern, A. & Tessin, W. (1987b) Anfang und Ende des Massenwohnungsbaus, Archiv für Kommunalwissenschaften, 26, pp. 34–51.

- Hess, D. B., Tammaru, T. & van Ham, M. (2018) Lessons learned from a pan-European study of large housing estates: origin, trajectories of change and future prospects, in: Hess, D. B., Tammaru, T. & van Ham, M. (Eds) Housing estates in Europe. Poverty, ethnic segregation and policy challenges, pp. 3–31 (Cham, Switzerland: Springer).

- Hess, D. B., Tammaru, T. & van Ham, M. (Eds) (2018) Housing estates in Europe. Poverty, ethnic segregation and policy challenges (Cham, Switzerland: Springer).

- Hillebrecht, R. (1971) Zur Lage, Stadtbauwelt, 30, pp. 105.

- Hoffmann-Axthelm, D. (1990) Die Stadt, das Geld und die Demokratie, Arch+, 105/106, pp. 107–111.

- Hundertwasser, F. (1958) Verschimmlungs-Manifest gegen den Rationalismus in der Architektur, in: U. Conrads (Ed) (1964): Programme und Manifeste zur Architektur des 20. Jahrhunderts, pp. 149–152 (Berlin, Germany: Ullstein).

- Hunger, B. (1992) Neue Bundesländer, Zur städtebaulichen Weiterentwicklung der Neubaugebiete, Bundesbaublatt, 11, pp. 834–838.

- Jacobs, J. (1963) Tod und Leben großer amerikanischer Städte (Berlin, Germany: Ullstein).

- Jäger, J. (2006) Akkumulation und Wohnungspolitik, Kurswechsel, 3, pp. 31–37.

- Jessen, J. (1989) Aus den Großsiedlungen lernen? Das Scheitern eines Modells, Die alte Stadt, 4, pp. 568–581.

- Kabisch, S. & Grossmann, K. (2013) Challenges for large housing estates in light of population decline and ageing: results of a long-term survey in East Germany, Habitat International, 39, pp. 232–239.

- Kadi, J. (2015) Recommodifiying housing in formerly ‘red’ Vienna?, Housing, Theory and Society, 32, pp. 247–265.

- Kainrath, W. (1971) Urbanie, Architektur Aktuell, 24, pp. 14.

- Kapeller, V. (2009) Umfassende Erneuerung der Plattenbausiedlungen in Wien und Bratislava, Europa Regional, 17, pp. 95–107.

- Kearns, A., Kearns, O. & Lawson, L. (2013) Notorious places: image, reputation, stigma. The role of newspapers in area reputations for social housing estates, Housing Studies, 28, pp. 579–598.

- Keller, R. (2007) Diskursforschung. Eine Einführung für SozialwissenschaftlerInnen (Wiesbaden, Germany: VS).

- Keller, R. (2011) The sociology of knowledge approach to discourse (SKAD), Human Studies, 34, pp. 43–65.

- Kemppainen, T., Kauppinen, T., Stjernberg, M. & Sund, R. (2018) Tenure structure and perceived social disorder in post-WWII suburban housing estates: a multi-level study with a representative sample of estates, Acta Sociologica, 61, pp. 246–262.

- Kennett, P. & Forrest, R. (2003) From planned communities to deregulated spaces: social and tenurial change in high quality state housing, Housing Studies, 18, pp. 47–63.

- Kil, W. (2017) ‘Wie Häuser altern auch Stadtteile…’ – Die Normalisierung der Moderne, in: J. Richter, T. Scheffler & H. Sieben (Eds) Raster Beton: vom Leben in Großwohnsiedlungen zwischen Kunst und Platte, pp. 8–11 (Weimar, Germany: Mbooks).

- Kirchner, J. (2006) Wohnungsversorgung für unterstützungsbedürftige Haushalte. Deutsche Wohnungspolitik im europäischen Vergleich (Wiesbaden, Germany: DUV).

- Klotz, H. (Ed) (1984) Die Revision der Moderne. Postmoderne Architektur 1960–1980 (München, Germany: Prestel).

- Koch, E. (1984) Aufbruch aus Emmental, Wohnbau, 10, pp. 4–15.

- Kohoutek, R. & Pirhofer, G. (1991) Jeder erstelle seine eigenen Leitlinien, Perspektiven, 6/7, pp. 10–14.

- Kovács, Z. & Herfert, G. (2012) Development pathways of large housing estates in post-socialist cities: an international comparison, Housing Studies, 27, pp. 324–342.

- Kramper, P. (2013) Die Neue Vahr und die Konjunkturen der Großsiedlungskritik, Informationen zur modernen Stadtgeschichte, 1, pp. 13–24.

- Löffler, R. (2001) Gebietsbetreuung für Gemeindebauten, Perspektiven, 1, pp. 14–17.

- Lücke, P. (1960) An einem wohnungspolitischen Wendepunkt, Bundesbaublatt, 10, pp. 565–570.

- Machule, D. & Stimmann, H. (1981) Auf der Suche nach der Synthese zwischen heute und morgen – Zum Städtebau der Nachkriegszeit in der DDR, Stadtbauwelt, 72, pp. 383–392.

- Mang, K. (1978) Ausstellung Kommunaler Wohnbau in Wien - Aufbruch 1923-1934 – Ausstrahlung (Wien, Germany: Presse- u. Informationsdienst der Stadt Wien).

- Matznetter, W. (1991) Wohnbauträger zwischen Staat und Markt. Strukturen des Sozialen Wohnbaus in Wien (Frankfurt am Main, New York: Campus).

- Matznetter, W. (2002) Social housing policy in a conservative welfare state: Austria as an example, Urban Studies, 39, pp. 265–282.

- Mayer, V. (Ed) (2006) Plattenbausiedlungen in Wien und Bratislava zwischen Vision, Alltag und Innovation (Wien, Germany: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie für Wissenschaften).

- Mitscherlich, A. (1965) Die Unwirtlichkeit unserer Städte. Anstiftung zum Unfrieden (Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp).

- Müller, W. (2008) Kalter Krieg, Neutralität und politische Kultur in Österreich, ApuZ. Available at http://www.bpb.de/apuz/32264/kalter-krieg-neutralitaet-und-politische-kultur-in-oesterreich (accessed 20 July 2018).

- Newman, P. & Thornley, A. (1996) Urban Planning in Europe. International competition, national systems and planning projects (London, UK: Routledge).

- News (2006) EU-Richtlinie wird umgesetzt. Ab heute sind alle Gemeindebauten für Ausländer offen. Available at www.news.at/a/eu-richtlinie-ab-gemeindebauten-auslaender-131283# (accessed 06 September 2016).

- Petzinger, R. & Kraft, S. (1974) Baukrise 73/74 – Entwicklungstendenzen im Wohnungsbau, Arch+, 22, pp. 8–19.

- Pfeiffer, U., Aring, J. & Schote, H. (1993) Große Wohnbaugebiete der 90er Jahre (Bonn, Germany: Empirica).

- Pfeil, E. (1970) Die Stadtsanierung und die Zukunft der Stadt, in: BfS – Büro für Stadtsanierung und soziale Arbeit (Ed) Sanierung – für wen? Gegen Sozialstaatsopportunismus und Konzernplanung, pp. 53–63 (Berlin, Germany: BfS).

- Posener, J. (1975) Kritik der Kritik des Funktionalismus, Arch+, 27, pp. 11–18.

- Rainer, A. & Prachensky, M. (1958) Architektur mit den Händen, in: G. Feuerstein (Ed) (1988) Visionäre Architektur, p. 47 (Berlin, Germany: Ernst).

- Reinecke, C. (2013) Laboratorien des Abstiegs? Eigendynamiken der Kritik und der schlechte Ruf zweier Großsiedlungen in Westdeutschland und Frankreich, Informationen zur modernen Stadtgeschichte, 1, pp. 25–34.

- Rose, N. (1999) Power of Freedom: Reframing Political Thought (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press).