Abstract

The movement of housing policy across space/time has attracted considerable policy and scholarly interest. But once we accept that policy moves, interesting questions arise. Particularly: what is it that moves? Why do some policies move but others do not? Academic conversations have involved concepts like “policy diffusion”, “policy transfer”, “lesson-drawing”, “fast policy”, “policy mobility” and “policy translation” - but a clear picture of how these concepts have been used to interpret housing policy developments is absent. Through systematic bibliographical searches, we identified 55 ‘housing’ publications to review. Our concern is the theoretical assumptions underlying these studies and their implications for the questions stated above. Through a grounded analysis, we identified ‘dominant knowledge’ as the key element shaping housing policy movement; highlighted five strategic conditions for mobility (summarized as ontological, ideological, institutional, legitimizing devices, and contingency); presented the sporadic engagement with questions of immobility; and synthesized authors’ policy recommendations, particularly their calls for deeper engagement with the people affected by policies.

1. Introduction

The movement of policy from one place to another, or from one time period to another, has attracted considerable interest from researchers across academic disciplines. In a world where emphasis is placed on ‘evidence-based’ policy making, the scope for learning lessons from policy developments in other jurisdictions is of fundamental interest for policy makers across policy fields, including housing.

But as soon as we accept that policies do, or could, move a whole range of profound and challenging epistemological and ontological questions present themselves. In the academic literature a number of parallel, but occasionally intersecting (McCann & Ward, Citation2013*),1 conversations among academics from different disciplines have involved concepts such as diffusion, transfer, lesson-drawing, fast-policy, mobility, translation, failure or tourism. These concepts developed at different times and in different disciplines. Some developed (mostly) independently, others in reaction to existing approaches that were deemed inadequate. They have been applied to a wide range of policy areas, theoretical development being derived from very different case studies of, for example, criminal justice (McFarlane & Canton, Citation2014*), cultural, environment and health policy (Evans, Citation2017*), urban policy (Pojani, Citation2020*), and also housing policy.

However, we do not have a clear picture of how the above concepts have been used to interpret housing policy developments. We aim to contribute to addressing this lacuna by presenting the first attempt to rigorously review the use of ideas of policy movement in housing research. In particular, we focus on the questions: What is it that moves? How do we find out? Can we say why some policies move and others remain immobile?

From the outset, we faced a dilemma regarding the substantive focus of our review as being directed to just one housing policy, a few field related policies or housing policy in general. While each has its merits, the last approach, which we followed, provides richer data for answering our questions with a higher degree of theoretical generalization. We thus review 55 ‘housing’ publications identified through systematic searches performed in four large bibliographical databases. We are concerned with the epistemological and ontological assumptions deployed across very heterogeneous studies - in terms of discipline, guiding theory, methodology, housing policy subfield - and how such assumptions shape authors’ claims. Consequently, we draw on principles from critical interpretative synthesis.

Clearly, reviewing methods have increasingly become more theoretically attentive and differentiated in their aims, which range from aggregation of findings (statistically or thematically) to theory-building and further to interpretative accounts that highlight (un)-bridgeable lines of difference (Barnett-Page & Thomas, Citation2009*). It is beyond our scope to review such methods here, suffice to say that critical interpretative synthesis is “a methodology that enables synthesis of large amounts of diverse qualitative data and facilitates critical engagement with the assumptions that shape and inform a body of research” (Farias & Laliberte Rudman, Citation2016* p.33). This approach has guided our research questions, the discovery of the literature, data extraction and our interpretation of authors’ claims. It also enhanced the relevance of our study in two more ways. First, we proposed a simple yet robust conceptual heuristic that allows us to navigate the many differences of this fragmented body of research, and critically reflect on their claims. Second, and more generally, our study invites caution in simple aggregation of findings in thematic or evidence reviews, demonstrating that conceptual grasp must inform the claims that a review can make.

We proceed by presenting the methodology in Section 2. Section 3 presents a conceptual heuristic of three clusters (policy diffusion, policy transfer and policy mobility), which is then employed in Section 4 to structure the answer to our research questions, and in Section 5 to reflect on their implications for policy and future-research. In order to avoid unnecessary repetition, we introduce relevant concepts from the policy ‘movement’ literature - a broad term we use to refer to this whole area of research - at the appropriate points in our discussion. Section 6 concludes the article.

2. Methodology

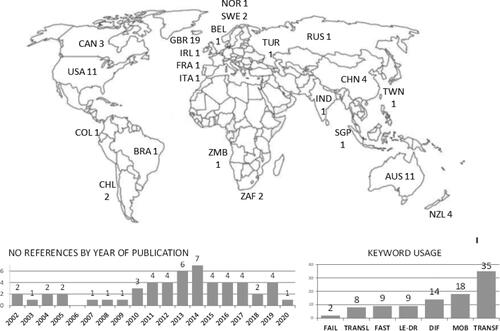

presents the sequential steps by which we selected the 55 references reviewed in this article. Our review expands on an earlier exercise of ‘mapping’ (Soaita, Citation2018*; Soaita et al., Citation2020*) the academic nexus between the subject of policy movement and that of housing across 247 publications in terms of publication timeline, geography, and conceptually-relevant keywords based on title/abstract reading and keyword searches in publication’s text (S1-S4 in ).

Table 1. Research process.

Each methodological decision was carefully considered within the team. For instance, we decided against restrictions on publication timeline, geography or housing (sub)topic because we wanted to observe related trends. The selection of keywords was informed by both prior knowledge of the literature and preliminary mapping (Soaita, Citation2018*). We agree with de Jong et al. (Citation2015* p.27) that conceptual keywords should be ‘recognized terms in the relevant international academic literature’ that are ‘taken up, and resonate, in the wider policy discourse’. Some candidate keywords were rejected for being meta-categories, (e.g. policy-making or policy-learning), others for being sub-categories (e.g. ‘fast-transfer’).

For reviewing, the first author extracted data into a large Excel file based on initial categories guided by the principles of critical interpretative synthesis (e.g. authors’ philosophical and theoretical positions; concepts of policy movement and their definitions; methods; housing policy focus; key findings and recommendations). We then identified (sub)-themes within and across categories. Separate theme files were constructed (e.g. ‘what is mobile’) to examine similarities and differences across papers.

indicates temporal and geographical patterns and keyword usage in the 55 studies reviewed. Two studies were published in the 1990s, all others were post-millennium. Seven studies addressed unspecified supra-national geographies, hence case-study geography could be mapped for 48 references; 30 are one-country and 18 multi-country analyses. The Anglo-Saxon dominance of the literature is evident, not least reflecting the structural effect of our English keywords and the availability of research funding. As some studies contained more than one of our keywords, we counted keyword usage by paper; “policy transfer” was dominant. Given our systematic though not exhaustive searches, we suggest these geographical and temporal trends broadly reflect interest in this research area.

The specific housing policy focus of the reviewed studies is very diverse (Box 1). This diversity suited the aims of our critical interpretative approach to understand the theoretical assumptions that shape this body of work while pursuing a degree of theoretical generalization, which necessarily overshadows the housing substance of the reviewed publications. We now proceed to the discussion of findings: we begin by presenting our conceptual heuristic, which will then inform the discussions in section 4 (What is mobile?) and Section 5 (Implications for policy and future research). We will differentiate references to the broader literature from the studies reviewed by starring the former.

Box 1. Policy focus.

HOMELESSNESS (n = 13): e.g. Housing First, Common Ground, UK legislation, the ‘Staircase’ model.

PLANNING (n = 11): e.g. disability-accessible housing, developing the eco-city, participatory inclusion, offsetting the environmental losses of housing developments, inclusionary zoning, the Houston low-regulation planning model; British planners’ visits in the USSR.

NATIONAL HOUSING MODELS (n = 8): e.g. Chilean affordable homeownership, Hong Kong or Singaporean public housing, South-African subsidy system, the Swedish owner-cooperative model; Taiwan’s public-private partnership model.

SOCIAL HOUSING (n = 5): e.g. UK and Dutch models of choice-based lettings, neighbourhood regeneration, stock-transfer, the Delft-model of new public management; policy reforms in Australia, UK and US.

NEIGHBORHOOD REDEVELOPMENT (n = 4): large housing estates, private-public partnership.

DEVELOPMENT OF AFFORDABLE HOUSING (n = 3): Housing Trust Funds, affordability metrics, alternative tenures and innovative finance.

GENTRIFICATION (n = 3): dispersal of public tenants and low-income residents in Australia, US and Zambia, mega-gentrification.

INFORMAL HOUSING (n = 2): slums and squatter housing.

OTHERS (n = 6), energy poverty; home repairs; residential mobility; neighbourhood and health; second-home ownership; the role of housing researchers. Note: coding each paper on one theme exclusively is challenging given thematic overlapping, nonetheless, we tried to assess above the papers’ key focus.

3. A Conceptual heuristic

We could compile a long list of words used in the reviewed publications to conceptualize, describe or qualify ideas of policy movement. Both nouns (e.g. adaptation; adoption; adjustment; contagion; circulation; diffusion; dissemination; failure; fast transfer; imitation; innovation; motion; migration; mimesis; mobility; mobilities; mutation; replicability; transfer; transferability; transference; translation; tourism) and adjective/verbs (e.g. assembled; convergent; fast; flowing; imitative; learning; mobile; mutate; travelling; selling) proliferate within the field.

We agree with Pawson & Hulse (Citation2011 p.115) that there is ‘an embarrassment of riches when it comes to theories, concepts and mechanisms’ of housing policy movement, which originate in different disciplines, and that this is not very useful. Hence, we found it valuable (as have a few others, e.g. Pojani, Citation2020*) to recommend a conceptual heuristic consisting of three clusters: policy diffusion (PD), policy transfer (PT) and policy mobility (PM). This simplifies this extremely diverse conceptual field but still remains true to the substantive and theoretical claims made. Allocating the reviewed studies correspondingly has been relatively unproblematic, albeit sometimes it required branching up authors’ own explicit/implicit affiliation (e.g. transferability into transfer). As we will reference sparingly for reason of space, the Annex lists all reviewed publications by conceptual clusters.

However, concepts of housing policy movement, even when they form the core concepts of a publication, tend to be embedded in broader theories, showing specific cluster affinities. For instance, assemblage theories figure strongly in our PM housing studies (Baker & McGuirk, Citation2017; Lancione et al., Citation2017; McFarlane, Citation2011) whereas institutional realism, with its corollaries of convergence/divergence, housing/welfare regimes, path-dependence or weak globalization frames many PT housing studies (Allen et al., Citation1999; Murie & Van Kempen, Citation2009). A couple of papers take ideology as their core concept, with policy mobility being secondary (DeVerteuil, Citation2014; Murphy, Citation2016).

Neoliberalism is a particularly common trope within the reviewed studies, whether as a core concept (Blessing, Citation2016; Darcy, Citation2013; Gilbert, Citation2002a) or more commonly as a contextual descriptor. This is perhaps not surprising given the international expansion of neoliberal housing policies (Clapham, Citation2019*; Peck & Theodore, Citation2015*). However, some scholars focusing on historical events, i.e. British policymakers’ and planners’ visits to the USSR and Scandinavia (Cook et al., Citation2014; O'Hara, Citation2008), counter the PM assumption that the movement of policy is a mark of the neoliberal ‘contemporary rise in reflexive governance, an accelerated transnationalization of policy norms and practices, and the increased mobility of policy techniques and policymakers’ (Jacobs & Lees, Citation2013 p.1577) by showing this feature of policy-making has a much longer heritage.

As with any taxonomy, our conceptual heuristic displays fuzzy borders, occasionally crossed by the same author (e.g. Gilbert, Citation2002a; Citation2002b; Murphy, Citation2014; Citation2016). About half of the 55 publications engaged with or simply acknowledged the other perspectives (reflected in the keyword usage in ), with PM scholars mostly refuting alternatives and PT scholars trying to create some positive synergies. However, engagement with a single conceptual perspective should not necessarily be seen as theoretically weak; sometimes the opposite was true (e.g. Baker & McGuirk, Citation2017 on the development of homeless policy in Australia; Mullins & Pawson, Citation2005 on the barriers to ‘choice-based-letting’ in England).

PD studies (n = 5)

These papers focus on the extent, speed and patterns of spatial and temporal movement of housing policy and on the factors that facilitate/inhibit diffusion processes. While only five publications2 used diffusion as a core concept, nine more acknowledged it. Their geographical scale goes against the main criticism that PD studies look at cross-country policy movement (Chang, Citation2017) - as many looked at the regional scale - while supporting the observation that they tend to be US-based (Soaita, Citation2018*).

There is a clear split between the quantitative and qualitative approaches across these papers. The quantitative publications - the more common approach in the broader policy diffusion field (Berry & Berry, Citation1999*) - are not necessarily actor-blind in their assumptions but rather in their method for which ‘it is not possible to assemble systematic data on the topics of [political and societal] debate’ (Meltzer & Schuetz, Citation2010, p.599) or hardly ever possible to ‘closely examine the myriad of factors that shape the adoption’ of policies (Scally, Citation2012, p.128).

Conversely, the qualitative housing PD studies (Darcy, Citation2013; Gilbert, Citation2002a; Nishita et al., Citation2007) resemble the PT literature in the ways structure and pluralistic agency are accounted for - as we will show later. This also indicates one ground for fuzzy conceptual borders: it is not the term used to capture the process of movement but the conceptual content that matters.

PT studies (n = 30)

Few PT studies acknowledge their epistemological/ontological positions (a criticism made by PM scholars, e.g. Chang, Citation2017) but those who do resonate with weak social-constructionism (e.g. Abram & Cowell, Citation2004; Akers, Citation2013; Murphy, Citation2014; Warwick, Citation2015) or institutional realism (e.g. Hodges & Grubnic, Citation2005; Pawson & Gilmour, Citation2010).

Of 30 publications, 14 focus on cross-country analyses and 15 exclusively on national actors/policies. This only partially supports a key criticism that the PT literature has a cross-country and top-down focus (Jacobs & Lees, Citation2013).

Drawing on traditional qualitative or mixed methodologies,3 PT housing studies try to explain: policy-(regime) change; ‘success’ or ‘failure’ of housing policies to transfer or lessons to be learned; potential for transferability; and the role of institutional actors that are seen as drivers of change.4 PT studies do not discuss the adaptation/mutation of policy when in motion nor the role of charismatic individuals, non-human agency or contingency in shaping policy movement: these are all issues that are explored by the PM studies reviewed below.

Interestingly, most PT papers develop some kind of historical policy analyses related to authors’ interest in policy-regime change - occasionally since the 1950s but more commonly the 1980s - either as the core argument or to contextualize more recent case-studies. This extended temporal horizon contrasts with most of our PD and PM studies.

Some PT studies see policy movement as an incontestable fact of life, past and present, needing no conceptual engagement (Savitch, Citation2011, below) whereas others carefully reflect on its relational and changing nature (Murphy, Citation2014 below):

British common law and courts successfully function on the Indian subcontinent and parts of Africa; American-type university systems operate with considerable success in Israel, Korea, and Hong Kong; and Japanese “quality circles” have been transferred to American automobile manufacturers with very positive results. On the face of it, there is no reason why urban development in America cannot profit from an experience elsewhere (Savitch, Citation2011, p.823).

Policy transfer involves both the deterritorialisation of nationally constituted and temporally specific sets of practices and, simultaneously, the reterritorialisation of these practices in a new national/local market and regulatory contexts (Murphy, Citation2014, p.894).

The latter quotation comes from a scholar who has traversed the PT/PM fuzzy border in discussing policy construction, both articles discussing the provision of affordable planning in New Zealand through planning mechanisms (Murphy, Citation2014, Citation2016). Indeed, increasing cross-disciplinarily and the recent appeal of the ‘mobility turn’ (Sheller & Urry, Citation2006*) seems to have stimulated academic conversations across perspectives.

PM studies (n = 20)

PM scholars see themselves as responding to important societal changes, arguing that ‘such is the novelty of this new era of policy mobility that scholars have distinguished between it and preceding eras of ‘policy transfer’” (Jacobs & Lees, Citation2013 p.1561). In contrast to PD and PT authors, they are keen to leave their epistemological and ontological signature, commonly associated with relational and assemblage theories (e.g. McFarlane, Citation2011; Parkinson & Parsell, Citation2018), or social-constructionism (Jacobs & Lees, Citation2013). Indeed, the concept of assemblage infuses much of the PM literature, inviting:

… geographers to approach ‘policy’ as a heterogeneous assemblage of actors (in this theoretical register, the term ‘actor’ often applies to texts, people, buildings, organisations, institutions, etc.) each with their own capacities, roles and interests but nonetheless enjoined together by mediators that induce the linkages necessary for assemblages to cohere (Baker & McGuirk, Citation2017 p.33).

Methodologically, PM scholarship is qualitatively eclectic, displaying an ‘ethnographic sensibility’ and ‘assemblage-inflected methodologies of various sorts as analytical tools for revealing, interpreting, and representing the worlds of policy-making, though few are explicit about their methodological practice’ (Baker & McGuirk, Citation2017, p.425). The questions asked refer to actor-centred processes that shape the recognition of a ‘problem’ and the endorsement of a ‘policy solution’, including the trans-local connections facilitating such processes.5

While arguably research questions may not differ substantially from those asked in PT studies, they are significantly more actor-centred, with human and non-human agency being understood as unpredictable and messy rather than rational. PM scholars are also more likely to look for thick-descriptions rather than explanations, aiming to unravel how policy is continually ‘assembled, disassembled and reassembled according to the elements (both discursive and material) that it encounters’ (Lancione et al., Citation2017, p.7). This clearly makes the PM perspective ontologically distinctive, with the PD and PT alternatives often rejected in forthright terms, as does Wells (Citation2014, p.447) in a study of ‘public property disposal’ related to a homeless shelter embarked for market redevelopment:

The rug has been pulled out from the traditional, aspatial, and too often linear political science notion of policy transfer. Policy transfer has been replaced with the sturdier concept of policy mobility.

Our three-cluster conceptual heuristic has proved valuable for understanding the assumptions shaping authors’ views related to what is it that moves and how this can be found out. The next section will answer the question of ‘what is mobile’ and extracts conditions for mobility and perspectives on immobility across the reviewed studies.

4. What is mobile?

Taken at the face value, what is mobile are certain ‘policies’, which among our reviewed papers were highly diverse (as shown in Box 1). However, the term ‘policy’ can refer to a wide range of related but distinct phenomena: these include policy discourses and symbols, as well as policy goals, content, instruments, institutions, ideologies, ideas and attitudes, and negative lessons (Dolowitz & Marsh’s Citation2000*). While policy movement could refer to any one or more of these, investigating movement of some aspects of ‘policy’ is more challenging than others. At a more subtle level - and generalizing from our very diverse case-studies - there is shared recognition that what underpins the movement of policy is the mobility of dominant knowledge and its powerful apparatus of soft and hard, human and non-human agents and devices.

PD authors are more inclined to understand knowledge as the acts of reason and reasonable negotiation (Nishita et al., Citation2007). They seem less troubled by the questions of how, why and by what means knowledge moves, is constructed and legitimized. Three of the five PD publications reviewed focus on legislative acts, which are seen as indisputable points of policy enactment, related to ‘inclusionary zoning’ (i.e. a share of affordable housing to be provided by market residential redevelopment), provision of disability access in single-family homes, and Housing Fund Trust (all in the US).

PT scholars are more likely to recognize knowledge as being socially constructed, stratified and embedded though to a lesser degree than their PM counterparts. For instance, Parsell et al’s (Citation2014, p.69) borrowed the concept of ‘knowledge hierarchy’ to explain that ‘professional intuition and personal experience were afforded a higher status than formal evaluative evidence’ in their case-study of the ‘Common Ground’ homeless policy in Australia. Likewise, in his analysis on the adaptation of the Chilean model of capital housing subsidy in Colombia, Gilbert (Citation2004, p.202) borrowed the concept of ‘transnational “epistemic communities”’ to discuss the soft mechanisms enabling the mobility of knowledge, particularly the shared sensibility of policy-technocrats and consultants who are ‘in constant contact with specialists in other nations and particularly attuned to new policy trends’. The fact that residents’ knowledge and voices are commonly silenced is rarely recognized because scholarship in all clusters remains primarily focused on policy elites; for a PD exception see Darcy’s (Citation2013) study on public tenants’ displacement under pressures for gentrification; PM exceptions will be mentioned later.

PM authors tend to be more concerned with the granular practices by which knowledge is transmitted through cross-cultural dialogue of ideas, lobbying actors, elite learning trips and professional workshops. Whatever the particular housing policy under examination, specific attention is also drawn to the agency of non-human devices, such as statistics, architectural magazines, planning exhibitions, attractive Power Point slides mobilized in disseminating knowledge, past (Jacobs & Lees, Citation2013; Baker & McGuirk, Citation2017) or present (Chang, Citation2017). PM scholars – exceptionally PD (e.g. Nishita et al., Citation2007) and sometimes PT (e.g. Murphy, Citation2014; O'Hara, Citation2008) authors – are more concerned with bottom up practices of resistance within professional communities. Exceptionally, Apostolopoulou (Citation2020) and (Wells, Citation2014) document the struggle of local communities, the former within a case-study of environmental contestation against exclusive housing, the later, already noted, against the closing of a homeless shelter. PM scholars argue that:

Without attending to the fine-grain of practice, critical policy scholars risk over-estimating the salience of influential actors and political projects, and under-estimating the contingencies, failures, course corrections, and re-directions that animate the making and implementation of policy (Baker & McGuirk, Citation2017, p.439).

The role of ideology in policy movement – particularly in situations when ideology is mobilized as depoliticized ‘knowledge’ – is perhaps best brought to the fore by authors using theories of neoliberalism (Darcy, Citation2013; DeVerteuil, Citation2014) and ‘power and conflict’ (Murphy, Citation2016).

Given space constraints, we cannot delve into the many practices of a multitude of actors who mobilize different types of knowledge, social networks, discourses and materialities through which (policy) knowledge moves as reported across the reviewed studies, particularly by PM scholars.6 Instead, in we present one of the theoretically and empirically richest papers in each conceptual cluster to provide illustrative examples. shows that, in work at this level of analytical sophistication, there are (commonly unrecognized) similarities between clusters regarding the ways in which the dissemination of knowledge and its apparatus are conceived. But differences are also apparent: the PD relational approach remains more structured (e.g. proponents versus opponents) and open to reasonable negotiation whereas the PM approach favours a more disaggregated and contingent stance.

Table 2. What is mobile? Examples of agents and devices in three planning studies.

Since so many actors and devices enact the movement of policy, it is interesting to lock at what conditions facilitate or impede (housing) policy movement across time and space.

Conditions for mobility

A focus on policies that move is dominant across the reviewed studies, this being the object of recent critique (Chang, Citation2017). Building across conceptual clusters, we wish to highlight five key insights on the conditions required for policy movement. We necessarily look beyond findings that remained specific to particular case studies in order to construct a ‘bigger picture’. While this approach could be seen as limited by the loss of housing detail and nuance, we would argue, in contrast, it is a necessary step in any synthesis.

The first insight is ontological. Whatever the conceptual perspective shaping the paper, there is recognition that policy moves but it also adapts to the specifics of the place. PM scholars argue that policy is adapted when it travels both horizontally between countries, regions or cities (e.g. Chang, Citation2017; Lancione et al., Citation2017 on eco-city planning and Housing First, respectively) and vertically when it travels through layers of governance (e.g. Cochrane, Citation2012 on the policy drive for the competitive city). In a PM study, Jacobs & Lees (Citation2013, p.1560) expressed one of the most disaggregated views of mobile policy, in this case of the urban design concept of ‘defensible space’ from the 1970s New York to the 1980s London:

What moves when policy is seen to replicate itself over time and across space is a far more disaggregated set of knowledges and techniques that are better thought of as pre-policy or sub-policy epistemes and practices.

Even PD scholars - who tend to see mobile policies as stable entities in the form of legal acts whose differences across places are downplayed - recognize some degree of reinvention as ‘an innovation is not constant during the diffusion process but is modified over time’ (Nishita et al., Citation2007, p.4). However, while claims of ‘mutation’, ‘translation’ are particularly strong in the PM literature, they were also well-rehearsed in some PT studies:

…policy transfer is not an ‘all or nothing’ process but represents a continuum from learning about a policy to adapting it to fit new contexts to implementing it and evaluating it, or deciding that it is not applicable at all (Parsell et al., Citation2013, p.188).

PT studies tend to refer to Dolowitz & Marsh’s (Citation2000*) theoretical framework of ‘policy transfer states’ that theorizes ‘the varying degrees of copying, emulating, hybridising, synthesising and inspiring that take place’ (Parsell et al., Citation2013, p.188):

(i) ‘successful transfer’ (convergence); (ii) ‘uninformed transfer’; (iii) ‘incomplete transfer’ where central features or dimensions of the policy are not transferred; and (iv) ‘inappropriate transfer’.

With others (Lovell, Citation2017*), we agree that the above taxonomy imprecisely mixes preconditions, outcomes and processes but the fact remains that policy is expected to change when moving. A distinction is that, while PT scholars can see states (ii)-(iii) as in some way deficient or falling short of ‘convergence’, PM scholars see convergence (i) as a chimera and mutation during movement as inevitable. In his analysis of the development and spread of Chilean housing policy, Gilbert (Citation2002a, p.1915–16) uses the idea of ‘six types of “diffusional episode” that characterize power relationships between “importing” and “exporting” nations.

The second insight is ideological: policy moves ‘successfully’ across places and actors of similar ideological sensitivities. There are no papers in our sample that do not reflect on - sometimes implicitly but mostly explicitly - enacted and enacting ideological beliefs, mostly of the political and professional elites and rarely those of the public/residents. From this point of view, Lancione et al’s (Citation2017 p.7) emphasis is illuminating:

we propose to understand HF [Housing First] as a policy in the dual sense of the word: both as a programme of measures to be implemented (the policy, as practice) and as a system of thought (the political, as a philosophy of intervention).

Papers tend to argue that policy movement rarely, if ever, disrupt the existing very unequal structures of power, resources and knowledge. Rather the existing structures of power and the related devices involved in policy movement – ‘including domination, authority, manipulation, inducement, coercion, seduction, and instrumental and associational powers’ (McFarlane, Citation2011 p.665) – support elites’ interests and agendas, a point to which we will return.

The third insight, most strongly apparent in PT studies, is institutional: housing policy typically moves across places with similar institutional structures. Murie & Van Kempen’s (Citation2009 p.192) call made in the context of policies towards the rehabilitation/regeneration of large housing estates in Europe can be credibly generalised:

we need to be extremely careful when talking about the possibility of policy transfer. A successful policy in one spatial or political context will not necessarily be successful in another context and, in any case, may only be able to be transferred if there are comparable legal, organisational and financial arrangements in place.

The fourth insight, coming in particular from the PM literature, refers to the legitimizing power of the various devices of policy-marketing/propaganda that communicate and sell policy from one place to another. These are of various kinds (see ) but we wish to report here two examples in more detail. Wragg & Lim (Citation2015, p.268) conclude that the persuasive power of the ‘urban visions’ proposed in the master plans produced by international developers and architect firms helped hide policy links to global profit-making while justifying the eviction of local residents from their informal settlements:

the urban visions for African cities were generally met with positive comments. They are powerful and compelling in suggesting both opportunity and a “world class” identity for the city one that appealed to a sense of national pride […]. Moreover, approval of the visions is given in a context where escalating globalized flows of goods, images and real estate investment into Lusaka is exposing urban dwellers to new landscapes of consumers’ aspirations and representations of the global city.

Other powerful devices mobilized to construct ‘successful’ policy-movement are the various calculative practices inscribed in the approach of evidence-based policy. PM scholars are highly critical of their manipulative use, whether in relation to the governance of homelessness (Baker & Evans, Citation2016) or planning procedures (Chang, Citation2017; Jacobs & Lees, Citation2013):

its ‘proven’ results, the ‘scientific nature’ of the approach and its elevation to ‘good practice’ status are arguably markers of what is currently (at least in the West) taken for, and branded as, ‘success’ […] this legitimation is the ‘Foucauldian’ truth in which a particular type of knowledge wields the power to mobilize interests, sets processes in motion and changes the state of affairs of things (Lancione et al., Citation2017, p.5/6, reflecting on the challenges of Housing First in the Italian case).

The rhetoric of ‘choice’ and ‘fairness’ in enacting housing policy movement is brought to the fore by PT studies (Gurran et al., Citation2014; Mullins and Pawson, Citation2005; Murphy, Citation2014), despite there being complex structural factors (rather than plain political intentionality) that challenge implementation. For instance, Mullins & Pawson (Citation2005 p.226) concluded that housing scarcity and concern to restrict access in case of anti-social behaviour or likely rent arrears limit the ‘implementation of choice’ in choice-based letting.

Finally, the fifth insight, coming from across clusters, but more strongly from PM studies, refers to contingency. The idea of ‘windows of opportunity’ (Kingdon, Citation1984*) may refer to the suddenly auspicious alignment of some of the above elements, e.g. the opportune meeting of a new science paradigm with a new government’s ideology (Jacobs & Lees, Citation2013) or new possibilities to shift the agenda opened by a ‘crisis’ (Akers, Citation2013):

These barriers to adoption are much weaker at times of crisis. What constitutes a crisis is not easy to define […] but by its very nature a crisis tends to encourage radical action. A precursor to such action is often to look for help from other places or to accept help from overseas that was previously unwelcome (Gilbert, Citation2004, p.200).

Perspectives on immobility

Although the literature on policies failing to move is small, it has developed several perspectives to immobility or to ‘failed’ policy-movement’; please note we are not concerned in this paper with policies failing to achieve their objectives (Howlett, Citation2012*). While very limited attention has been paid to successful policies that show no sign of being adopted anywhere else, even in modified form (but see Malone, Citation2019*), attempted movement has attracted more interest. For instance, from a PM perspective, Wells (Citation2014, p.475) examines:

the moments in which policies are defeated, stopped, or stalled, plain and simple. I use the word “moments” purposefully because the making of a policy may fail temporarily, repeatedly, or permanently.

Wells (Citation2014, p.488) clearly problematizes notions of ‘successful’ or ‘failed’ policy-movement by emphasizing ‘the utility of thinking of policyfailing as an ongoing and unstable process rather than focusing on policy failure as an unequivocal achievement’. She also directs the attention to the space of grassroots’ discontent and struggle against a policy, in this case the privatisation for demolition of a housing shelter in Washington DC. However, she concluded that punctual success - i.e. one (temporarily) stopped transaction - boosted rather than challenged existing governance structures, which became better organised to implement public property disposal to private developers at discounted rate; the shelter was later closed and likely sold in the future.

Problematizing immobility from a different perspective, Chang’s (Citation2017, p.1735) PM study argues that the ‘multifaceted and lasting influences’ of some failed projects - in this case the planning of the eco-city of Dongtan, China - call for considering the idea of learning from failure since:

…despite its apparent failure, Dongtan eco-city established a set of urban planning procedures adopted by many, including those who designed and delivered the Tianjin eco-city… The intent to avoid association with Dongtan’s failure also fostered a new eco-urbanism model based on rebranding the planning practices of Singapore’s public housing. Parts of Dongtan eco-city have also lived on through the international circulation of a piece of planning software that was first developed for the failed project (p.1719).

Although PM studies argue that their focus on immobility is novel, some PT publications have also advanced perspectives on immobility. For instance, Gilbert (Citation2002b, Citation2004) argues that the failure of Washington housing policies to transfer and counteract the established Chilean housing subsidy model was a purposeful tactics on the part of the Chilean government, which negotiated international funding while following its own rather than funders’ attached policies. Gilbert thus argues that power can sometimes be negotiated between the more and less powerful.

Another PT perspective on policy immobility is that of non-transfer rather than failed transfer. For instance, within a case of ‘policy tourism’ - that is, professional visits abroad by decision-makers and planners – O’Hara (2008) discusses Britain’s unrealized attempts to copy the model of Scandinavian housing co-operatives (i.e. subsidized by the state, but organized by owners and tenants) in the early 1960s; key barriers to transfer were the already strongly institutional and cultural entrenchment of Council housing and owner-occupation in the UK.

Likewise, in a comparative case study of Scotland and Norway, Abram & Cowell (Citation2004) noted that the global transfer of the rhetoric of ‘community planning’ in land-use planning concealed the lack of transfer of planning mechanisms and practices. Such practices remained local because ‘legal, political and cultural traditions’ differed. For instance, a key difference they noted was the degree of local administration autonomy and the strength of institutional links between planning administration and politics, both being weak in the UK and strong in Norway. In one of the less theoretically engaged studies in our sample, Savitch (Citation2011) makes a case for transferability of French urban regeneration policies to US cities, but does not question why there has never been any attempt at transfer.

Finally, while some scholars (Chang, Citation2017; Wells, Citation2014) argued that their novel focus on policy failing to move is needed to understand government processes, such a focus is far from new. In our sample, Dommel (Citation1990, p.241) is an early example. He ‘examines the initial British success or lack of success in adopting the US model’ of neighbourhood rehabilitation programme which failed to transfer in the UK. It was found that homeowners remained reluctant to move from a grant-based to a loan-based approach of financing. Additionally, they had deeply internalized ‘attachments to different perceptions of the scope of government; that is, the roles of the public and private sectors’ (p.248). For such a model to succeed in the long term, a recognized change of paradigm was seen as required:

… the policy transfer effort is likely to hinge on whether British homeowners can be convinced that the private-sector approach is here to stay and that a change of governments will not bring a return of the long-established public-sector model with its grant-based foundation (Dommel, Citation1990, p.241).

Reviewing this relatively small literature of ‘failed’ policy-movement, in conjunction with its flip-side of ‘success’, we wish to highlight Wells’s (Citation2014) call for conceptual clarity regarding the failing of policy to move over and above its ability to adapt, mutate and ‘localise’ across place and time (see also Stone, Citation2017*). In other words, how can we distinguish between a policy that moves and one that has changed while moving to such an extent that has become something new? This call may also inform PD scholarship, which analyses patterns of diffusion but not wheather non-diffusion between adjacent states indicates non-existent or failed attempt to move policy (Allen et al., Citation1999).

5. Implications for policy and future research

Given that such a diversity of housing policy subfields is covered by the 55 reviewed publications, discussing their specific recommendations for policy or future-research is unwarranted; for that a different reviewing approach is required, one that focus on much narrower questions. However, our critical interpretative approach illuminates how the way in which policy is understood has implications for the type of recommendations being made. One striking fact is that few papers contribute explicitly on these directions (22 make recommendations for policy and 28 for future research).

Policy recommendations come mostly from PT and PD qualitative studies (but also from some PM studies, e.g. Lancione et al., Citation2017), with policymakers being urged to critically consider the potential for transferability before engaging in transfers, particularly from the standpoints of embedded policy assumptions, existing institutions, and the non-linear nature of policymaking:

It is important to critically scrutinise these [homelessness] models, examining their core elements and the manner in which they are appropriated and incorporated across jurisdictions (Parsell et al., Citation2013, p.186).

[policy is] adapted to its new institutional structure; and institutional factors may also inhibit implementation despite the interest of key actors. Transfer processes may well be recursive, such that the source country continues to adapt its policy implementation (Pawson & Hulse, Citation2011, p.130).

Warwick’s (Citation2015) PT study is exceptional in advancing pragmatic policy recommendations, which spring from the case study of planning eco-towns in England but have wider relevance. She calls for genuine collaborations between levels of governance; building policy resilience to economic and political changes; and a need for policymakers to establish exemplar projects, offer practical advice and avoid both too rapid policy change and the involvement of too many agencies. While these insights apply to broader processes of policy formulation and implementation, they are equally relevant to policy transfer. What such PT recommendations have in common is a belief that rational actors are willing to negotiate and achieve stated policy aims.

Conversely, PM scholars remain sceptical about offering policy recommendations because they challenge the social-construction of evidence and see multiple (ideological, political, power) barriers to the transfer of scientific knowledge to policymaking.

Besides such irreconcilable differences, we wish to highlight scholars (across conceptual affiliations, e.g. PD: Darcy, Citation2013; PT: Hodges & Grubnic, Citation2005; PM: Lancione et al., Citation2017, DeVerteuil, Citation2014) who urge a deeper engagement with the people affected by policies, such as facilitating more participatory and consultative modes of governance and particularly the genuine inclusion of (low-income and other vulnerable) residents in the adoption, rejection or adaptation of policies affecting their housing:

What is lacking in Lusaka is the means through which residents can challenge market driven development and promote their own visions for the city (Wragg & Lim, Citation2015, p.269).

We agree that failing to involve ordinary citizens and users, or disregarding their contestations, in policymaking is nothing but a ‘democracy deficit’ as ‘citizens, as taxpayers and users of services, are always significant stakeholders’ (Apostolopoulou, Citation2020, Hodges & Grubnic, Citation2005 p.74), whether the policy is designed at home or adapted from elsewhere. Indeed, we wish to highlight this aspect - largely overlooked within the studies reviewed - as the key policy recommendation of our review. Moreover, meaningful citizen engagement in episodes of policy movement almost by definition increases the likelihood and extent of policy change during motion.

Recommendations for future research are similarly aligned with conceptual allegiances (and methodological limitations, which we will not develop here).7 For instance, following the spirit of assemblage-thinking, PM studies call for research that brings together a range of scales (global, local) and sites (countries, cities, institutions, communities) in which policies are (re)-interpreted, with particular attention to ‘local variations and the local structures of power and inequalities’ (Jacobs & Lees, Citation2013, p.1578). Likewise, research that unravels ‘the critical relationship between the actual and the virtual city, between the city that is and the city that might have been or that might otherwise arise’ (Cochrane, Citation2012; McFarlane, Citation2011, p. 668, Murphy, Citation2016; Lees, 2012; Darcy, Citation2013) is welcomed in order to counteract the limited set of ideas currently moving.

The increasing theoretical awareness and ‘more pragmatic operational concerns’ (Johnsen & Teixeira, Citation2012 p.199) of PT translate into an increasing interest in the social-construction of policymaking around very diverse foci, e.g. how ‘legislative interventions privilege private investors over public interest, while narrowing the scope for alternatives and forcing localities to adapt to market “realities” created through state power’ (Akers, Citation2013, p.1090); ‘how some ideas […] persist despite premeditated or unintentional policy derailment’ (Warwick, Citation2015, p.494); how knowledge is constructed and communicated (Gilbert, Citation2002b; Murphy, Citation2014); or how ‘problems’ and policy outcomes come to be recognized, addressed and monitored (Johnsen & Teixeira, Citation2012). These suggestions reflect a move by some PT scholars towards more relational views, while retaining the (neutral) rationality assumption embedded in the evidence-based approach. Finally, we agree and wish to close this section by extending Parsell et al.’s (Citation2014, p.85) call for research that critically evaluates policy decisions as well as their outcomes:

Decisions made now may have repercussions for many years in terms of opening up and closing off specific avenues for policy development on homelessness in Australia. Put another way, might Common Ground projects which are viewed as the solution for today (by creating additional self-contained and permanent housing for vulnerable homeless people in very tight housing markets) create the problems of tomorrow (by keeping formerly homeless people still concentrated and isolated from the rest of the society and denying them access to regular housing outside the buildings specifically designed for them).

The point is well-made whether the housing policies under consideration originate locally or draw inspiration from elsewhere.

6. Conclusions

By reviewing 55 publications, we aimed to understand the ways in which concepts of policy movement have been used to interpret housing policy developments. In particular, we focused on the questions of what moves; how we find out; and why some policies move while others do not. Before answering these questions, we wish to briefly reflect on the limitations and strengths of our method.

Our systematic yet not exhaustive searches were sufficiently broad to give us confidence that the sampled literature creates a solid base to achieve this article’s aim. Our rigorous assessment of the strength of thematic engagement led to the inclusion of five publications that proved to be rather weak alongside many deeply engaged studies. We suggest this is a feature of this area of research: there is a growing interest in the ‘mobility turn’ within housing studies, but the way the relevant concepts are deployed does not always fully reflect the sophistication of the literature from which they are drawn.

Drawing on principles from critical interpretative synthesis led us to present a simplifying three-cluster conceptual heuristic, which helped us to critically learn across highly heterogeneous studies. Our heuristic, with is fuzzy borders, is more complete than dominant two-cluster conversations, which, as we noted in section 3, sometimes promote unfair claims and criticism. To some extent, such criticism, as advanced by the authors of the publications reviewed, represents a rehearsal of contours of the broader ‘policy movement’ debate, particularly claims on the cross-country and quantitative nature of PD studies or the exclusively national focus and lack of theorization in PT studies. We found strong and weak studies in all clusters in terms of theoretical engagement. But clear differences remain between the three approaches. We would highlight the degree of multiplicity and disaggregation in the understanding of policy and the policy arena, and the degree of rationality and plurality of agency - both linked to different theories and methodologies.

In answer to our first and second research questions, there were different views on what ‘policy’ is, hence different views on that which is moving. These views were least problematic for quantitative PD scholars who, at least in our small sample, identified policy with law enactment. PT authors tended to understand policy as an (ideological) programme to be implemented while PM scholars saw policy as a (dis)/(re)-aggregated assemblage of programmes, practices, systems of thought and materialities. Obviously, these ontological tenets have major implications on how policy movement is understood and researched. Methods differ between quantitative (PD), traditionally qualitative and mixed (PD and PT) and qualitatively eclectic (PM). Despite these differences, our analysis showed there were shared views that what is moving when policy moves is dominant knowledge and movement relies on a powerful apparatus of soft and hard, human and non-human devices.

A dominant empirical focus on mobile policies was evident and not unexpected since it constitutes the core of this area of writing. Critically learning from across clusters, our synthesis put forward five key insights of what it takes for a policy to become mobile. The first (ontological) is a recognition that policy moves but it also adapts to the specifics of the new location. The second (ideological) and third (institutional) refer to the fact that policy moves among actors of similar ideological/knowledge sensitivities and across places of analogous institutional structures. The fourth (legitimacy) refers to the power of various devices that sell policy, ranging from rhetoric to evidence-based calculative practices. The fifth (contingency) refers to ‘windows of opportunity’ provided by circumstantial alignments or crises. Despite a dominant focus on mobility, we found several perspectives on immobility, which are neither purely novel nor exclusive to PM studies, ranging from local defeat of global policies to policies that remained unknown beyond the locality of origin.

Our approach of mapping understandings of policy movement across housing research broadly rather than targeted at just one specific policy has thus facilitated a higher level of theoretical generalization, which lends relevance to our arguments for both housing and policy studies. Generating a significant enough sample for analysis, our approach showed that housing research is a productive site for salient and useful recommendations on (housing) policy movement. As our broad approach precluded a focus on the substantive recommendations of the studies reviewed - given their diversity - we see merits in our reviewing method being applied to specific housing policies in the future.

We wish to close this article with one broader reflection. While many relevance claims are stated across the reviewed studies, there is a clear sense that it matters to the lives of many people what lessons from elsewhere are prioritized and what power relations they serve. With others (Murphy, Citation2016), we believe that housing studies would benefit from a renewed theoretical and empirical engagement with the ways power unfolds in processes of (dis)-empowering when policies move across space and time. Perhaps this has never been more important than now, when the Covid-19 crisis is rippling out across the globe, creating social suffering but also opening new windows of opportunity.

Acknowledgments

We thank the three reviewers for their thoughtful suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Adriana Mihaela Soaita

Dr Adriana Mihaela Soaita is a Research Fellow at the University of Glasgow. She is interested in the individuals’ experienced nexus between housing (and home), socioeconomic and spatial inequalities on which she has published widely. She is also a Romanian chartered architect and planner fascinated by home’s materialities.

Alex Marsh

Professor Alex Marsh teaches Public Policy at the School for Policy Studies, University of Bristol. His research has touched on many aspects of housing policy, with the focus currently on governance and the private rented sector. He is also a Co-Investigator for the UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence.

Kenneth Gibb

Professor Kenneth Gibb teaches at the University of Glasgow on the economic, financial and policy dimensions of housing. He is also Director of the UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence. Ken has conducted research for national and international organizations, including governments, OECD and the EU.

Notes

1 To differentiate between the broader literature referenced and the studies reviewed, we star the former.

2 Topics per Box 1: planning (n = 2); affordable housing (n = 1); gentrification (n = 1); national housing models (n = 1).

3 Mostly interviews with decision-makers and professionals in conjunction with survey data and various documents (commonly without disclosing sources); occasionally ethnography and historical archive research.

4 Topics per Box 1: homelessness (n = 6); national housing models (n = 6); neighbourhood redevelopment (n = 4); social housing (n = 4); others (n = 4); planning (n = 3); affordable housing (n = 2); informal housing (n = 1).

5 Topics per Box 1: homelessness (n = 7); planning (n = 6); gentrification (n = 2); others (n = 2); informal housing (n = 1); national housing models (n = 1), social housing (n = 1).

6 14 publications, mostly PD and PT, advanced more structural analyses, eschewing the granular detail.

7 Difficulties in assembling data are acknowledged particularly by quantitative PD papers (Meltzer and Schuetz, 2010, Scally, Citation2012) and PM scholars whose preferred ethnographic approach is constrained by lack of the resources required to follow a highly-mobile and dispersed elite (Chang, Citation2017). As there is still limited potential for (theoretically) generalization from one policy or one site (Allen et al., Citation1999, Gilbert, Citation2002a, Abram and Cowell, 2004), qualitative scholars of all persuasions call for more empirical research.

References

- Abram, S. & Cowell, R. (2004) Learning Policy – the Contextual Curtain and Conceptual Barriers, European Planning Studies, 12, pp. 209–228.

- Akers, J.M. (2013) Making Markets: Think Tank Legislation and Private Property in Detroit, Urban Geography, 34, pp. 1070–1095.

- Allen, C., Gallent, N. & Tewdwr-Jones, M. (1999) The Limits of Policy Diffusion: Comparative Experiences of Second-Home Ownership in Britain and Sweden, Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 17, pp. 227–244.

- Anderson, J.T. & Collins, D. (2014) Prevalence and Causes of Urban Homelessness among Indigenous Peoples: A Three-country Scoping Review. Housing Studies, 29, pp. 959–976.

- Apostolopoulou, E. (2020) Beyond Post-Politics: Offsetting, Depoliticisation, and Contestation in a Community Struggle against Executive Housing, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 45, pp. 345–361.

- Baker, T. & Evans, J. (2016) Housing First' and the Changing Terrains of Homeless Governance, Geography Compass, 10, pp. 25–41.

- Baker, T. & McGuirk, P. (2017) Assemblage Thinking as Methodology: Commitments and Practices for Critical Policy Research, Territory, Politics, Governance, 5, pp. 425–442.

- Barnett-Page, E. & Thomas, J. (2009)* Methods for the Synthesis of Qualitative Research: A Critical Review, BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9, pp. 59

- Berry, F.S. & Berry, W.C. (1999)* Innovation and diffusion models in policy research, in P.A. Sabatier (Ed) Theories of the Policy Process, pp. 169–200 (Boulder, CO: Westview Press).

- Blessing, A. (2016) Repackaging the Poor? Conceptualising Neoliberal Reforms of Social Rental Housing, Housing Studies, 31, pp. 149–172.

- Chang, I.C.C. (2017) Failure Matters: Reassembling Eco-Urbanism in a Globalizing China, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49, pp. 1719–1742.

- Clapham, D. (2019)* Remaking Housing Policy: An International Study (London: Routledge).

- Cochrane, A. (2012) Making up global urban policies, in: G. Bridge & S. Watson (Eds) The New Blackwell Companion to the City.; pp. 738–746 (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell).

- Cook, I.R., Ward, S.V. & Ward, K. (2014) A Springtime Journey to the Soviet Union: Postwar Planning and Policy Mobilities through the Iron Curtain, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38, pp. 805–822.

- Darcy, M. (2013) From High-Rise Projects to Suburban Estates: Public Tenants and the Globalised Discourse of Deconcentration, Cities, 35, pp. 365–372.

- de Jong, M., Joss, S., Schraven, D., Zhan, C. & Weijnen, M. (2015)* Sustainable–Smart–Resilient–Low Carbon–Eco–Knowledge Cities; Making Sense of a Multitude of Concepts Promoting Sustainable Urbanization, Journal of Cleaner Production, 109, pp. 25–38.

- DeVerteuil, G. (2014) Does the Punitive Need the Supportive? A Sympathetic Critique of Current Grammars of Urban Injustice, Antipode, 46, pp. 874–893.

- Dolowitz, D.P. & Marsh, D. (2000)* Learning from Abroad: The Role of Policy Transfer in Contemporary Policy-Making, Governance, 13, pp. 5–24.

- Dommel, P.R. (1990) Neighborhood Rehabilitation and Policy Transfer, Environment & Planning C: Government & Policy, 8, pp. 241–250.

- Evans, M. (Ed.) (2017)* Policy Transfer in Global Perspective (London: Routledge).

- Farias, L. & Laliberte Rudman, D. (2016)* A Critical Interpretive Synthesis of the Uptake of Critical Perspectives in Occupational Science, Journal of Occupational Science, 23, pp. 33–50.

- Gilbert, A. (2002a) Power, Ideology and the Washington Consensus: The Development and Spread of Chilean Housing Policy, Housing Studies, 17, pp. 305–324.

- Gilbert, A. (2002b) Scan Globally; Reinvent Locally': Reflecting on the Origins of South Africa's Capital Housing Subsidy Policy, Urban Studies, 39, pp. 1911–1933.

- Gilbert, A. (2004) Learning from Others: The Spread of Capital Housing Subsidies, International Planning Studies, 9, pp. 197–216.

- Gurran, N., Austin, P. & Whitehead, C. (2014) That Sounds Familiar! A Decade of Planning Reform in Australia, England and New Zealand. Australian Planner, 51, pp. 186–198.

- Hodges, R. & Grubnic, S. (2005) Public Policy Transfer: The Case of PFI in Housing, International Journal of Public Policy, 1, pp. 58–77.

- Howlett, M. (2012)* The Lessons of Failure: Learning and Blame Avoidance in Public Policy-Making, International Political Science Review, 33, pp. 539–555.

- Jacobs, J.M. & Lees, L. (2013) Defensible Space on the Move: Revisiting the Urban Geography of Alice Coleman, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37, pp. 1559–1583.

- Johnsen, S. & Teixeira, L. (2012) Doing It Already?': Stakeholder Perceptions of Housing First in the UK, International Journal of Housing Policy, 12, pp. 183–203.

- Kingdon, J.W. (1984)* Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies (New York: The Book Service Ltd.).

- Lancione, M., Stefanizzi, A. & Gaboardi, M. (2018) Passive Adaptation or Active Engagement? The Challenges of Housing First Internationally and in the Italian Case, Housing Studies, 33 pp. 40-57.

- Lovell, H. (2017)* Are Policy Failures Mobile? An Investigation of the Advanced Metering Infrastructure Program in the State of Victoria, Australia, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49, pp. 314–331.

- Malone, A. (2019)* (Im)Mobile and (Un)Successful? A Policy Mobilities Approach to New Orleans’s Residential Security Taxing Districts, Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 37, pp. 102–118.

- McCann, E. & Ward, K. (2013) A Multi-Disciplinary Approach to Policy Transfer Research: Geographies, Assemblages, Mobilities and Mutations, Policy Studies, 34, pp. 2–18.

- McFarlane, C. (2011) The City as Assemblage: Dwelling and Urban Space, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 29, pp. 649–671.

- McFarlane, M.A., & Canton, R. (Eds.) (2014)* Policy Transfer in Criminal Justice: Crossing Cultures, Breaking Barriers (New York: Palgrave Macmillan).

- Meltzer, R. & Schuetz, J. (2010) What Drives the Diffusion of Inclusionary Zoning?, Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 29, pp. 578–602.

- Mullins, D. & Pawson, H. (2005) ‘The Land That Time Forgot': Reforming Access to Social Housing in England, Policy & Politics, 33, pp. 205–230.

- Murie, A. & Van Kempen, R. (2009) Large housing estates, policy interventions and the implications for policy transfer, Mass Housing in Europe: Multiple Faces of Development, Change and Response., pp. 191–212 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan).

- Murphy, L. (2014) Houston, We've Got a Problem’: The Political Construction of a Housing Affordability Metric in New Zealand, Housing Studies, 29, pp. 893–909.

- Murphy, L. (2016) The Politics of Land Supply and Affordable Housing: Auckland’s Housing Accord and Special Housing Areas, Urban Studies, 53, pp. 2530–2547.

- Nishita, C.M., Liebig, P.S., Pynoos, J., Perelman, L. & Spegal, K. (2007) Promoting Basic Accessibility in the Home Analyzing Patterns in the Diffusion of Visitability Legislation, Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 18, pp. 2–13.

- O'Hara, G. (2008) Applied Socialism of a Fairly Moderate Kind': Scandinavia, British Policymakers and the Postwar Housing Market, Scandinavian Journal of History, 33, pp. 1–25.

- Osypuk, T.L. (2015) Shifting from Policy Relevance to Policy Translation: Do Housing and Neighborhoods Affect Children’s Mental Health? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50, pp. 215–217.

- Parkinson, S. & Parsell, C. (2018) Housing First and the Reassembling of Permanent Supportive Housing: The Limits and Opportunities of Private Rental, Housing, Theory and Society, 35, pp. 36–56.

- Parsell, C., Fitzpatrick, S. & Busch-Geertsema, V. (2014) Common Ground in Australia: An Object Lesson in Evidence Hierarchies and Policy Transfer, Housing Studies, 29, pp. 69–87.

- Parsell, C., Jones, A. & Head, B. (2013) Policies and Programmes to End Homelessness in Australia: Learning from International Practice, International Journal of Social Welfare, 22, pp. 186–194.

- Pawson, H. & Gilmour, T. (2010) Transforming Australia's Social Housing: Pointers from the British Stock Transfer Experience, Urban Policy and Research, 28, pp. 241–260.

- Pawson, H. & Hulse, K. (2011) Policy Transfer of Choice-Based Lettings to Britain and Australia: How Extensive? How Faithful? How Appropriate?, International Journal of Housing Policy, 11, pp. 113–132.

- Peck, J. & Theodore, N. (2015)* Fast Policy: Experimental Statecraft at the Thresholds of Neoliberalism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota).

- Pojani, D. (2020)* Planning for Sustainable Urban Transport in Southeast Asia. Policy Transfer, Diffusion, and Mobility (Gewerbestrasse: Springer).

- Savitch, H.V. (2011) A Strategy for Neighborhood Decline and Regrowth: Forging the French Connection, Urban Affairs Review, 47, pp. 800–837.

- Scally, C.P. (2012) The Past and Future of Housing Policy Innovation: The Case of US State Housing Trust Funds, Housing Studies, 27, pp. 127–150.

- Sheller, M. & Urry, J. (2006)* The New Mobilities Paradigm, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 38, pp. 207–226.

- Sheppard, G. & Beck, M. (2018) The Evolution of Public-private Partnership in Ireland: A Sustainable Pathway? International Review of Administrative Sciences, 84, pp. 579–595.

- Soaita, A.M. (2018)* Mapping the Literature of ‘Policy Transfer’ and Housing. Working Paper, Glasgow, UK: UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence.

- Soaita, A.M., Serin, B. & Preece, J. (2020)* A Methodological Quest for Systematic Literature Mapping, International Journal of Housing Policy, 20, pp. 320–324.

- Stone, D. (2017)* Understanding the Transfer of Policy Failure: Bricolage, Experimentation and Translation, Policy & Politics, 45, pp. 55–70.

- Van Vliet, W. (2003) So What if Housing Research is Thriving? Researchers’ Perceptions of the Use of Housing Studies. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 18, pp. 183–199.

- Warwick, E. (2015) Policy to Reality: Evaluating the Evidence Trajectory for English Eco-Towns, Building Research & Information, 43, pp. 486–498.

- Wells, K. (2014) Policy Failing: The Case of Public Property Disposal in Washington, D.C, ACME, 13, pp. 473–494.

- Wragg, E. & Lim, R. (2015) Urban Visions from Lusaka, Zambia, Habitat International, 46, pp. 260–270.