?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The study of reference dependence in housing markets is of practical importance due to the unusual characteristics of property transactions, such as high information asymmetry caused by many individuals’ lack of experience in housing markets. The overall low transaction frequency and general illiquidity of housing markets can exacerbate and reinforce behavioural anomalies such as reference dependence. The knowledge gained through an empirical investigation in the UK housing market can assist in the understanding of these behavioural biases. By conducting an online experiment at a UK online panel data platform, we identify the presence of reference dependence in the UK housing market, and the extent to which they are caused by both historical and recent prices. The influence of expectations and social norms is also investigated in this novel context. The findings of this study pave the way for reliable economic modelling of such anomalies and a better understanding of behaviours in the housing market.

1. Introduction

Traditional economic theory predicts that people will maximize their expected utility under uncertainty and seek to make a rational decision by considering all relevant information. However, observations and experimental evidence across various disciplines have highlighted the existence of behavioural biases in the decision-making process. Many researchers have attempted to integrate psychological understandings into classical economic models to provide an explanation for such observed irregularities.

Reference dependence, in the context of prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky, Citation1979), is the most popular of these explanations. The concept presumes that individuals exhibit behavioural biases because they evaluate choice outcomes as gains or losses around a reference point. As reference points are vital to the categorisation of a gain and loss domain, and therefore to overall choice outcomes, it is beneficial to obtain a good understanding of how they are formed and how they can be adapted. It is especially pertinent to study reference dependence in housing markets due to their unusual characteristics, such as high information asymmetry caused by many individuals’ lack of housing market experience. Indeed, this could be exacerbated in the UK market, which recently saw homeownership fall to its lowest level in over 30 years (Evans, Citation2017). Therefore, since Arkes et al. (Citation2008) find that cultural factors bear some weight in reference point adaptations, this study of the UK housing market fills an important cultural gap in the literature. Moreover, the overall low transaction frequency and general illiquidity of housing markets can exacerbate and reinforce the observed anomalies. However, the knowledge gained through an empirical investigation in the UK housing market can assist in the attenuation of these distortions.

Based on the analytical framework in Paraschiv & Chenavaz (Citation2011), where reference dependence was studied in the French housing market, we conduct controlled experiments to investigate the presence of multiple reference points in the UK housing market. Our study adds to the behavioural housing studies literature in the following ways.

Firstly, we segregate respondents into sellers, buyers who are homeowners, and buyers who are renters. This is to recognize the potential effect of homeownership on housing decisions. We design separate questionnaires for buyers and sellers, with one respondent taking only one rule (i.e. a seller, an owner-buyer, or a renter-buyer). This avoids participants confusing their market roles, thus strengthening the robustness of the findings.

Secondly, in an important work on reference point formation and adaptation by Baucells et al. (Citation2011), intermediate prices are the least important determinants of reference point formation and adaptation. However, Paraschiv & Chenavaz (Citation2011) found that this is not true, at least in the French housing market. As the current literature is somewhat unclear on the influence of intermediate prices, we introduced two questions specifically testing the effect of historical peak and trough prices alongside the test of other intermediate prices.

Thirdly, we also considered two factors that are specifically relevant and important in housing markets: expected profits as reference points and the effect of social norms on the formation of reference points. At the time of writing, these factors have not been incorporated in reference point dependence studies in the housing market. However, given the fact that properties are seen as both consumption and investment goods, and are often used as a signal for social status, it is important to study the role of sellers’ target profit level and the role of social comparison.

Finally, we used online panel data (OPD) in this study. This approach is a significant improvement over the traditional online survey method used in Paraschiv & Chenavaz (Citation2011) in terms of sample representativeness and efficiency. An online panel is an electronic database of registrants who have indicated a willingness to participate in future web-based research studies. Examples of online panel data platforms include Amazon Mechanical Turk and Prolific. OPD and online panel participants have been gaining attention from researchers in social science studies. Given the cost and complexity of conducting behavioural studies in housing markets, it is worthwhile to explore the applicability of OPD in housing research. This is particularly true when the COVID-19 pandemic has already made virtual or distance activities the new norm for many aspects of our personal and professional lives. Our findings will be helpful for researchers to explore new data collection venues in response to these changes.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a critical review of the literature. Section 3 details the analytical framework and the five testable hypotheses this study aims to test. Section 4 explains the experimental design and justification for the data collection method. Section 5 presents analysis of the data and reports the empirical results. The final section summarises the paper and offers areas for future research.

2. Literature review

2.1. Behavioural housing studies

Although both Marsh & Gibb (Citation2011) and Smith (Citation2011) pointed out the potential of applying behavioural economics in housing studies, the challenges of finding suitable theories and empirical strategies are not to be underestimated. As Watkins & McMaster (Citation2011, p. 286) said in the same special issue of Housing, Theory and Society,

‘An urgent next step is to further elaborate on what an inter-disciplinary agenda might look like and how the insights generated might be reconciled to establish a coherent alternative (or addition) to the insights and stylized facts revealed by mainstream economists’ (page 286).

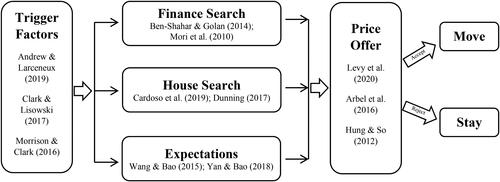

To illustrate the many aspects of housing choice decisions that have been analysed with behavioural tools, we constructed based on the housing choice process diagram in Maclennan (Citation1982). In this simplified version of a homebuyer’s move-stay decision process, we listed important steps from the trigger factors of a moving decision to the final decision to move or stay. We found representative behavioural studies in each of the steps listed between 2010 and 2020.

The housing choice process starts with some trigger factors, such as job changes and downsizing. Behavioural housing studies focus on psychological factors that trigger move decisions. For example, Andrew & Larceneux (Citation2019) investigated the effect of emotion in owning a new building apartment in influencing the decision to purchase off-plan apartments in France; Clark & Lisowski (Citation2017) studied the role of endowment effects in decisions of whether to migrate or not; and Morrison & Clark (Citation2016) discussed the relationship between loss aversion and the duration of residence. These psychological factors, along with other conventional triggers such as job changes, will lead an individual to collect information about how to finance the move, where to relocate, and what kind of property to buy. Studies show that personality and cultural factors significantly affect choice of mortgage products (Ben-Shahar & Golan, Citation2014; Mori et al., Citation2010). The advantages of using behavioural theories to explain irrational housing search decisions have been explored in Cardoso et al. (Citation2019) and Dunning (Citation2017). Evidence has also been found that expectations play a significant role in the decisions and outcomes of mega-event- or regeneration-led relocations in China (Wang et al., Citation2015; Yan & Bao, Citation2018).

The most important stage of the housing choice process is the ‘Price offer’ step, where the homebuyer places bids on identified properties. A wide range of behavioural factors have been investigated when studying how price offers are determined. For instance, Arbel et al. (Citation2016) found that past price information serves as reference points in public housing tenants’ decisions; Hung & So (Citation2012) showed how much extra a loss-averse home buyer will pay for a house; and Levy et al. (Citation2020) investigated the role of framing effects on homebuyers’ estimation of future house prices. All of these behavioural factors can affect the possibility of price offers to be accepted by sellers, and eventually whether the move is successful.

The papers included in are not a comprehensive list of behavioural housing studies in the last decade. They are chosen to demonstrate the scope of the literature, instead of its depth. To comment on the depth of behavioural housing studies literature, we need to focus on prospect theory, because it is the only behavioural economic theory that has been widely employed and rigorously tested in the housing studies literature.

2.2. Prospect theory and reference dependence

The most influential theory used to emphasize the importance of psychological aspects when modelling choice behaviour is prospect theory, developed by Kahneman & Tversky (Citation1979). Prospect theory illustrates how people’s observed preferences systematically deviate from the predictions of standard economic theory (SET hereafter). Three fundamental behavioural aspects for modelling individual decision-making processes are presented by prospect theory: reference dependence, loss aversion, and diminishing marginal sensitivity. According to prospect theory, the utility derived from consuming good/service X can be estimated by the value function below.

(1)

(1)

where

is the value function based on the consumption of X, and r is the reference point. The reference point divides the value function into two parts: one for a gain domain where X is greater than r and another one for a loss domain where X is below r.

> 1 reflects that individuals’ value function in the loss domain is steeper than that in the gain domain (i.e. loss aversion).

and

capture the effect of diminishing marginal sensitivity.

EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) shows that the role of reference point is instrumental for the applications of prospect theory. Reference dependence assumes individuals evaluate the outcome of a choice based on positive or negative changes relative to a reference point. This is contrary to SET which assumes individuals judge the outcomes of decisions on final states of wealth or assets. The observed inconsistencies between actual behaviour and the predictions of SET have been the subject of much academic interest in the real estate domain. For example, studies show that the behaviour of housing valuers and appraisers can be subject to behavioural biases. Appraisers tend to seek evidence in support of initial beliefs they form during the valuation process (Clayton et al., Citation2001).

Although there is ample empirical evidence on reference dependence, the literature comes to little agreement on the nature of the reference point. Indeed, in their formalization of prospect theory, Kahneman & Tversky (Citation1979) do not provide guidance or rules for how reference points are formed. This makes the identification of reference points an empirical issue, which has attracted much research interests in the past decades.

2.3. The search for reference points in housing markets

We now focus on studies of reference dependence in the residential property market. A total of 13 publications are identified from searches in the Web of Sciences database. A few papers, such as Genesove & Mayer (Citation2001), study loss aversion instead of reference point formation. However, the crucial first step of loss aversion analysis is to define loss and gain domains correctly. This inevitably involves the identification of reference points. Consequently, important loss aversion studies such as Genesove & Mayer (Citation2001) are included in our literature review because they have significant implications to reference dependence research. We summarize the research design and findings of these papers in .

Table 1. Reference dependence studies in residential property markets.

Several observations can be drawn from . Firstly, housing decisions involve multiple reference points. Although most of the reviewed papers employed one single reference point, the choice of the reference point varies among these studies. For example, initial transaction information is the predominant reference point identified among these studies. Ten out of the 13 studies use initial transaction information, such as purchase price (Anenberg, Citation2011; Einio et al., Citation2008; Genesove & Mayer, Citation2001; Leung & Tsang, Citation2013; Paraschiv & Chenavaz, Citation2011; Sun & Ong, Citation2014) and rent paid in previous cities (Simonsohn & Loewenstein, Citation2006) as a reference point. Decision makers also refer to the most recent transaction information when determining property prices or rents (Arbel et al., Citation2016; Hirota et al., Citation2020; Paraschiv & Chenavaz, Citation2011; Sun & Ong, Citation2014). Other significant historical information, such as all-time high or low prices, are valid reference points as well (Paraschiv & Chenavaz, Citation2011; Seiler et al., Citation2008).

Secondly, the reference dependence literature tends to focus on either seller or buyer behaviour, with nine out of the 13 papers study reference points used by sellers in their decisions. Paraschiv & Chenavaz (Citation2011) add an important dimension to the current research on property market behavioural biases by identifying that the reference point is influenced by the buyer or seller role. However, whilst their findings are illuminating, it can be argued they are specific to the French housing market and therefore may lack general applicability. More empirical evidence is needed to verify their findings.

Thirdly, there is a geographic shift in term of empirical investigations over the last two decades. Earlier behavioural housing studies draw conclusions primarily based on data from the US housing market (Anenberg, Citation2011; Bucchianeri & Minson, Citation2013; Genesove & Mayer, Citation2001; Simonsohn & Loewenstein, Citation2006) and EU countries (Einio et al., Citation2008; Paraschiv & Chenavaz, Citation2011). Recent investigations of reference dependence are mainly from Asian counties, such as China (Leung & Tsang, Citation2013), Israel (Arbel et al., Citation2014; Arbel et al., Citation2016), Singapore (Sun & Ong, Citation2014), and Japan (Hirota et al., Citation2020). Despite the UK’s importance in the world economy in general and the global financial market in particular, empirical evidence from the UK is lacking. The only study using UK data is Scott & Lizieri (Citation2012). However, the reference point investigated in the paper is a ‘false’ one: respondents’ telephone numbers. Specifically, the paper shows that first-time homebuyers’ pricing decisions are affected by irrelevant reference points (i.e. anchors). Although this is a useful exercise to verify findings from psychology studies in housing markets, the effects of valid reference points (e.g. purchase price and all-time high/low price) has not been verified in the UK property market yet.

To conclude, the identification of reference points in housing market is not straightforward. There is more than one reference point at work, and reference point dependence may differ between buyers and sellers, as well as vary among geographic regions. There are also evidence that the effect of reference points is moderated by gender (Seiler et al., Citation2008), age and income (Arbel et al., Citation2014), and market conditions (Paraschiv & Chenavaz, Citation2011). In the next section, we propose an analytical framework that incorporate all of these critical factors in the study of reference dependence in property price determinations. The framework is subsequently tested by using experimental data from the UK.

3. Research design

3.1. Analytical framework

Assuming a buyer/seller is trying to determine the market price of a property, the following equation can be constructed based on SET.

(2)

(2)

where

is the price that the buyer/seller is willing to pay/accept for the property,

is a collection of structural features of the property such as size and the number of bedrooms,

is a matrix of neighbourhood characteristics such as property crime rate and the distance to the nearest primary school,

denotes personal traits of the decision maker such as age and income, and

is the error term.

Prospect theory suggests that one or several reference points should be included in the general function in EquationEquation (2)

(2)

(2) . This gives us the following equation.

(3)

(3)

where

is a matrix of reference points. In the literature, EquationEquation (2)

(2)

(2) has been routinely estimated with linear regression and transaction data (i.e. hedonic price modelling). Using the same technique and data to estimate EquationEquation (3)

(3)

(3) can be problematic for two reasons. Firstly,

is usually highly correlated with

and determined by

as well. This gives raise to multicollinearity and endogeneity problems, both of which will bias the estimates. Secondly, the multiple reference points included in

are usually highly correlated among themselves too. It will be difficult to separate the net effect of each of the reference points considered. Finally, if any important attributes in

are missing, omitted variable bias could lead to unreliable estimation of reference dependence.

To address these issues, we adopt controlled experiments in our analysis. This method allows explicit control of the participants’ decision-making environment, making it possible to isolate the impact of important variables and identify any causal relationship between them (Rabin, Citation2002). This extra influence and ability to isolate variables is what makes controlled experiments one of the most widely used research methods in behavioural economics. For example, most of the studies of judgement bias in real estate valuation have been generated using experimental settings (Klamer et al., Citation2017).

In controlled experiments respondents are randomly allocated to a control group and a treatment group. The two groups are identical (on average) except for the treatment, such as the availability of historical transaction information. As a result, any difference in the average responses from the two groups can be attribute to the treatment, and a causal relationship can be established between the respond and treatment variables. If we let and

be the average price of the control and the treatment group respectively, the difference between

and

will be entirely due to the effect of

This is because the average value of

are identical between the two groups. As a result,

A rejection of the null hypothesis of

or

means that

has a significant impact on prices. In other words, reference dependence presents when

or

3.2. Testable hypotheses

Our research is developed from the experimental design in Paraschiv & Chenavaz (Citation2011), which is the only paper in the literature that considers multiple reference points in one setting, recognizes the role of buyers and sellers, and allows the effect of moderators such as market conditions to be investigated. We extend the work in Paraschiv & Chenavaz (Citation2011) by considering the effect of expectations and social norms in reference point formation. A total of five hypotheses are derived as outlined below.

Hypothesis 1: Initial purchase price is used as a reference point

Often the most salient reference point is the price the property was initially purchased for, as it acts as a natural indicator for whether money has been gained or lost on a transaction. Although many reference points are context-dependent, initial purchase price is one of the few that has been proven significant across different contexts. For example, Leung & Tsang (Citation2013) also found support for initial purchase price as the reference point using empirical evidence from the Hong Kong property market. It would seem, therefore, that initial purchase price has been well-studied and proven to be used as a reference point in a variety of contexts.

Hypothesis 2: Intermediate prices are used as reference points

An intermediate price, for this study, is that price which is observed after the initial purchase price and before the current price of the property. This includes both linear increases/decreases and historical peaks/troughs in price. Paraschiv & Chenavaz (Citation2011) determine that non-extreme intermediate prices have less of an impact than extreme ones, such as a historical peak, and show that individuals actually shift their reference points towards the historical peak. Yet, there are important empirical results that contradict this view. For example, Baucells et al. (Citation2011) adapted the experimental design of Arkes et al. (Citation2008) enabling them to directly observe the reference point formation process. The purchase price and current price of the time-series seem to be the main determinants of the participants’ reference price, while intermediate prices are relatively unimportant. The implications of the current findings on intermediate prices are therefore somewhat contradictory. As such, this investigation of intermediate prices as reference points in a UK property market context is a useful and necessary extension of the current literature that can hopefully bring some clarity to the current findings.

Hypothesis 3: Recent prices are used as reference points

Recent prices take on a slightly different meaning for a buyer and a seller in this study. For a seller, a recent transaction price of a similar property may act as a reference point for their valuation of their own property. Whereas, for a buyer, knowledge of an alternative offer received for a similar property may act as their reference point. Consequently, for a buyer, information of an alternative offer for the property is introduced in the hypothetical scenarios, while information about a recent transaction price of a similar property is introduced for sellers. Paraschiv & Chenavaz (Citation2011) find that the introduction of an alternative offer price shifts buyers’ reference points further than when initial purchase price is introduced. This result suggests recent information is weighted more highly than past information in the formation of reference points, supporting the findings of Baucells et al. (Citation2011).

We also investigate the effect of factors not previously applied to a property market context have on reference points. Specifically, this study will look at the role of aspirations in terms of an expected profit, and the moderating effect of social norms on reference dependence. Two more hypotheses are set up accordingly as follows.

Hypothesis 4: Expectations serve as reference points

The expected profit is defined as the level of profit that the seller would like to make between when they bought it and when they eventually sell it. There is ample evidence from the labour market to suggest that workers, specifically those that are free to choose the hours they work in a day, tend to serve a target level of income instead of maximizing their daily income (see, e.g. Camerer et al., Citation1997; Fehr & Goette, Citation2007). This seemingly illogical result can be explained by an expected daily income being used as a reference point. Home sellers will likely be affected by an expected profit because houses are both durable consumption goods and financial investments. In fact, this dual role of houses has significant implications for individuals’ decisions regarding housing and non-housing consumptions (Černý et al., Citation2010; Hung & So, Citation2012; Yang et al., Citation2018). For example, properties can enjoy unearned land value uplifts resulting from wider societal and infrastructural change in an area, which may occur despite no aspect of the property changing. Such market characteristics may result in agents expecting to sell their properties for more than they bought them. Therefore, it is important to verify whether expected profit affects reference point formation among home sellers in the UK.

Hypothesis 5: Social norms influence reference point formation

The effect of social norms, or the tendency for people to compare their lifestyles to the lifestyles of their peers, will be investigated as well. Decisions are rarely made in the socially isolated conditions adopted by most of the literature in this area, and hence the social context should be considered in the field of decision-making under risk (Linde & Sonnemans, Citation2012). One conceptualization of the reference price is that it represents a normative price, that is, the price the buyer believes to be ‘fair’ for the seller to charge (Bolton et al., Citation2003; Campbell, Citation1999). Viglia & Abrate (Citation2014) build on earlier work that looked at price sequences (Ariely & Zauberman, Citation2000; Baucells et al., Citation2011), but control for the presence of social influence. They find that individuals appear to be averse to paying much more than their peers as they would categorize this as a ‘loss’ when using a social reference point. The nature of housing markets may enhance the likelihood of individuals making social comparisons. Goethals (Citation1986) notes that where there is no physical reality to compare to, people tend to make social comparisons to satisfy their need to evaluate their opinions and abilities. Therefore, the infrequent trading and lack of transparency in property transactions may invite social comparison among housing market participants. Consequently, this investigation into whether reference point formation is influenced by social norms is beneficial for gaining an improved understanding of what drives the observed behavioural irregularities in the housing market.

4. Empirical implementations

4.1. Experimental design

To test the hypotheses outlined in Section 3, we set up a series of one-factor controlled experiments based on the framework in Paraschiv & Chenavaz (Citation2011), which is the only online experiment among the 13 papers included in . Conducting behavioural experiments online has the benefits of reaching respondents that other than university students, i.e. real decision makers. This is particularly important for housing decision studies, because university students are unlikely representative of the target population. We make adjustment to their experiment design by segregating sellers and buyers (which are further divided into homeowner and renter subgroups). Specifically, Paraschiv & Chenavaz (Citation2011) asked each respondent to answer questions for sellers first, and then questions for buyers. In our experiment, respondents take one and only one role: seller or buyer. This approach keeps the number of questions and the length of experiment shorter, which is critical to obtain reliable answers in online experiment; it also avoids the potential spill-over effect when respondents cannot quickly switch their role between seller and buyer. Admittedly, this approach will substantially increase the cost of the experiment but is necessary to ensure the reliability of the study.

Although buyers and sellers are segregated, both are put through the same ten hypothetical scenarios with the wording changed slightly to reflect their market role. The first four questions have been adapted to a growing market and a declining market (see ). The seller questionnaire asked for the minimum price the respondent would be willing to sell the property for; the buyer questionnaire asked for the maximum price the respondent was willing to pay for the property. From this point onwards, the buyers’ maximum buying price will be referred to as their ‘willingness to pay’ (WTP) and the sellers’ minimum selling price will be their ‘willingness to accept’ (WTA).

Table 2. Scenario designs.

To determine the presence of a behavioural bias, the first step is to establish a benchmark price according to SET. Buyers and sellers would behave rationally and refer to this market price to form their WTP/WTA. This piece of information is provided to all respondents in Questions 1 (in a declining market) and 5 (in an increasing market) as a price range of a property under consideration. Due to our natural tendence to maximize utility from the transaction, we expect that the average responds to Question 1 may be higher than that to Question 5. However, this potential discrepancy between sellers and buyers’ benchmark prices will not affect our analysis, because we focus on changes relative to these benchmarks.

Questions 1 − 4 and Questions 5 − 8 are used to test Hypotheses 1 − 3 in a decreasing and an increasing market condition, respectively. First, initial purchase price is introduced in Questions 2 and 6, followed by an intermediate price in Questions 3 and 7, and finally an alternative offer price (buyer) or a recent transaction price (seller) in Questions 4 and 8. The first four questions form three pairs, which are effectively three one-factor controlled experiments. For example, Questions 1 and 2 are the control and treatment groups to test the effect of initial purchase price. Let and

be the answers from respondent (buyer) i to Questions 1 and 2, respectively.

will be calculated for all respondents and used to test Hypothesis 1. Note that even if a respondent’s WTA is affected by the housing prices in her own city, the size of this anchoring effect remains the same in

and

because they are reported by the same individual from the same city. Because the only difference between these two questions is the introduction of an initial purchase, we can be confident that any changes in reported WTA is due to the initial purchase price. The same logic applies to Questions 2 to 4, as well as Questions 5 through 8 for the increasing market condition. This incremental introduction of the information makes it possible to isolate the effect of specific information, as no other aspects of the scenarios are changed. summarises which questions are used to test each hypothesis.

Table 3. Questions use to test hypotheses.

Questions 9 and 10 are used to test Hypothesis 4. The two questions have the same initial purchase price of £300,000. However, a historical high/low price that is £50,000 above/below the current market valuation is introduced in these two questions. If the average responses from these two questions are significantly above/below the current market valuation, there is evidence of historical high/low prices being used as reference points.

The seller questionnaire then has three additional questions (Questions 11 − 13) that introduce the concept of an expected profit that the respondent wants to earn when they eventually sell the property. They are then given the range of market price of similar properties and asked what their WTA was. Hypothesis 4 was tested by comparing the average responses to these three questions. Specifically, if the reported WTA increases as the target profit level changes from £25,000 to £75,000, expected profits are used as reference points.

Whilst the first four hypotheses verify the role of different reference points in house price determination, Hypothesis 5 checks the moderating effect of social norms on these relationships. To test Hypothesis 5, we use the differences between reported WTA/WTP and SET predictions (i.e. behavioural biases) as the dependent variable, and social norm measurements as the independent variable in regression models. The coefficient estimates of social norm variables, if statistically significant, can be used to gauge the direction and strength of the moderating effect. We design three questions to determine the respondent’s propensity for social comparisons. Initially, they were presented with a list of peers, for example ‘a close friend’, or ‘a colleague’, and were asked to select those which they had compared their lifestyle to. Participants were then asked how often they made these lifestyle comparisons and, on a scale of 0 to 10, how important it was that they were better off than the person(s) they had previously selected. The definition of these variables, along with other control variables in the regression models, are given in .

Table 4. Personal traits of respondents.

4.2. Online panel data

We used the online panel data (OPD) platform Prolific to conduct the experiment online. The number of published papers in social sciences that are using OPD has surged in recent years (Porter et al., Citation2019). Yet some researchers remain sceptical about the use of OPD platforms. Firstly, critics argue that participants are non-naïve to the studies, citing the emergence of ‘professional survey takers’ who participate in a high number of experiments and subsequently become aware of researchers’ motives. However, studies have shown evidence that crosstalk between participants, as well as respondents intentionally attempting to participate in one study repeatedly, is nearly non-existent (Chandler et al., Citation2014).

Secondly, there are fears that the quality of online sample data is inadequate due to respondents’ inattentiveness or lack of effort. However, substantial evidence suggests that attention levels of online participants either meet or exceed those from traditional sources (Behrend et al., Citation2011; Buhrmester et al., Citation2011; Crone & Williams, Citation2017; Goodman & Paolacci, Citation2017; Ramsey et al., Citation2016).

Finally, the representativeness of online participants has been questioned but the evidence compellingly suggests that online samples are more representative of typical working adults than traditional university student samples used in many behavioural experiments (Crone & Williams, Citation2017; Goodman & Paolacci, Citation2017; Peer et al., Citation2017). Indeed, Casler et al. (Citation2013) compared the results of online crowd-sourced respondents with in-lab respondents who both completed a behavioural task. They determined the responses of the two groups to be equivalent and found the crowd-sourced participants were significantly more representative.

The most widely used OPD platform is Amazon Mechanical Turk (or MTurk in short). We choose Prolific over MTurk because its abundance of UK respondents. MTurk’s respondents consisting of predominantly US (75%) and Indian (16%) citizens (Difallah et al., Citation2018). Prolific, on the other hand, have members from the UK primarily. As our objective is to collect empirical evidence from the UK housing market, Prolific provides us with access to the target population. Moreover, the extent to which we could pre-screen our sample was one of the main benefits of using Prolific. The platform allows us to pre-select respondents and classify them into homeowners and renters sub-sample and conduct experiment separatelyFootnote1. This filter facilitates the test of differences between the effects on first-time homebuyers and experienced homebuyers.

5. Empirical findings and discussions

In the last two columns of , we summarize the profile from the seller, the owner-buyer and the renter-buyer subsamples respectively. Respondents in the first two groups are very similar in all personal traits considered. The renter sub-sample are relatively younger, less educated, and with lower monthly income and housing expenditure. For example, none of the 195 renters paid more than £1,500 per month for housing. These patterns are consistent with the conventional profiles of homeowners and renters. It is worth noting that the proportion of females in all three sub-samples are consistently high, i.e. between 69% and 75%. This is certainly not representative of the whole population in the UK. However, this is an indication of the profile of online panel members at Prolific and maybe in the UK as well. Although there is no evidence that there is a significant gender imbalance in other OPD platforms, the UK OPD platforms might be dominated by female members. Our empirical findings should be interpreted with this caveat in mindFootnote2.

summarises responses from the three sub-samples respectively. The ‘SET Predictions’ column contains the prediction of SET based on the information given in Questions 1 and 5 (i.e. the average market prices). The ‘Manipulated Information’ column gives the new information provided in each corresponding question (further information can be found in the last column of ). The ‘Average Reported Prices’ column presents the average responses to each corresponding question. The ‘Deviation from SET Predictions’ column contains the difference between figures in the ‘Average Reported Prices’ column and the ‘SET Predictions’. Finally, the ‘Price Distribution’ panel shows how reported prices in each question are distributed around the SET predictions, providing further information for the ‘Deviation from SET Predictions’ column. Specifically, the ‘Lower’, ‘SET Predictions’, and ‘Higher’ columns contain the proportion of responses that are below, equal, and above the SET predictions respective. Figures in the last four columns in indicate clear deviation from the SET predictions in all questions across three subsamples.

Table 5. Behaviour under different market conditions.

To verify the statistical significance of identified biases in , we perform paired two-sample t test on each of the question pairs given in , and one-sample t test on the difference between average responses to questions 9 − 10 and their corresponding SET predictions. This evidence is used to test hypotheses 1 through 4, and the results are reported in .

Table 6. Test results for Hypothesis 1 through 4.

Hypothesis 5 is tested by using linear regressions, with differences in responses between question pairs in .e. for questions 1 − 8, and 11 − 13) or differences between average responses and SET predictions (i.e. for questions 9 − 10) as the dependent variable, and social norm measurements as the key independent variables. The general model specification is given below.

(4)

(4)

The definition of each independent variable can be found in the first column of . is defined either as the difference between answers to question pairs or the difference between answers and the corresponding SET predictions. The absolute values (i.e. the

function in the above equation) of

is used because the direction of biases does not matter. We used natural log transformation of all dependent variables to facilitate the comparison of coefficient estimates among models. Because the minimum value of

is zero (i.e. the reported WTP/WTA equals the SET prediction), we add one to the results so that the natural log transformation can be performed. In total there are 11 models estimated for sellers, and 8 models for buyers (owners or renters). These models are estimated by OLS, and the results are reported in . The test of each hypothesis is discussed below.

Table 7. Test results for Hypothesis 5 (seller, sample size = 197).

Table 8. Test results for Hypothesis 5 (Buyer – Owner, Sample Size = 203).

Table 9. Test results for Hypothesis 5 (Buyer – Renter, Sample Size = 195).

5.1. Hypothesis 1: initial purchase price is used as a reference point

The benchmark market price referred to in is established in Question 1 and Question 5 in a declining and growing market respectively. The reported responses in both questions are close to the SET predictions (i.e. an average market price of £300,000 for Question 1 and £500,000 for Question 5). This means that both sellers and buyers are able to predict market price rationally, in the absence of information manipulation.

Question 2 and Question 5 then introduced the initial purchase price. All three groups of respondents changed their WTA/WTP accordingly. For example, sellers increased their WTA by more than 25% in a declining market to be closer to the initial purchase price, while renters’ adjustment is more modest (i.e. 12.25%) in a similar setting. Initial purchase price has a stronger reference point effect in a declining market than in a growing market, for both sellers and buyers, and affects sellers’ reference point formation more than buyers, particularly in a declining market. Note that the responses from buyers are very similar between the owner and renter subgroups, which means homeownership did not change the effect of initial purchase price. Despite the differences in the responses among sellers and buyers, as well as in different market conditions, the effect of initial purchase price in reference point formation is statistically significant across the board, as can be seen in .

The results support Hypothesis 1, that initial purchase price is a reference point, as sellers’/buyers’ WTA/WTP deviates from SET predictions. As such, there is a clear behavioural bias and home sellers/buyers do not rationally refer to the average market price as SET would predict.

5.2. Hypothesis 2: intermediate prices are used as reference points

We then introduced a non-peak intermediate price in Question 3 and Question 7 for a declining and growing market respectively. Sellers and buyers altered their WTA or WTP towards this price accordingly. For example, in the average WTA reported in Question 3 was 17.67% higher than the SET prediction now, or a downward adjustment of 9% from the average WTA reported in Question 2. This highlights that when the intermediate price is closer to the current market price or SET prediction, sellers adjusted their WTA towards it. The price distribution also suggests that a higher proportion of respondents reported a WTA closer to the SET prediction, suggesting the intermediate price is being used as a reference point. The use of an intermediate price as a reference point seems to persist, regardless of market conditions.

The relevance of a historical peak/trough in price was also investigated. Question 9 introduced a scenario whereby the seller’s property had increased in value to a peak in price several years ago, but the market had subsequently fallen to the low current price. Question 10 followed the same structure but in the opposite market scenario, to elicit the effect of a historical trough in price. The findings indicate that information about a historical peak in price do lead to distortions in WTA/WTP. shows that the differences between the reported WTA/WTP and the average market price in both scenarios was highly statistically significant in the sellers and buyers (owners) group. The effect is weaker in the renter subsample, with significant effect identified for historical low price only.

The findings are consistent with the conclusions in Paraschiv & Chenavaz (Citation2011), but seemingly run counter to the results of Baucells et al. (Citation2011) who found relatively weak to no influence of historical peak and trough prices. However, their study uses stock prices rather than property prices, suggesting the disparity in results could be a consequence of the asset market studied. Price information is more valuable in the property market due to infrequent trading and lack of transparency in valuation compared to the stock market. This interpretation is supported by Seiler et al. (Citation2008) who noted that, in the real estate market, sellers experienced higher regret if they failed to sell at an all-time peak in price. Therefore, we conclude the results support Hypothesis 2; intermediate prices are used as reference points, and this remains the case when the intermediate price is a historical peak or trough.

5.3. Hypothesis 3: recent prices are used as reference points

Additionally, the results support the idea that recent prices were used as reference points. For sellers, Question 4 introduces information about a similar property that recently transacted below the market price. Following the introduction of this information, sellers’ average WTA drifted by 3.81% below the SET prediction. Indeed, just over 82% of sellers do not refer to the average market price when they are aware of a recent transaction price. 57.36% of this deviation is accounted for by sellers reporting a WTA below the market price, clearly showing their behavioural bias has been influenced by the recent price. Moreover, in a growing market the recent price also produces a statistically significant deviation in WTA, but in an opposite direction. The same patterns are observed for the two groups of buyers as well. All observed deviations from SET predictions are statistically significant at the 1% level, as reported in . As such, it can be said that the results confirm the notion that recent prices influence respondents’ WTP/WTA by acting as a reference point.

5.4. Hypothesis 4: expectations serve as reference points

Questions 11, 12 and 13 were used to test Hypothesis 4. Each question instructed the seller to imagine that when they bought their property, they had wanted to earn a certain level of profit on it when they eventually sold it. The desired level of profit was increased in each subsequent question. Because the information in these three questions is identical except for the target profit, we use the difference between questions to test the influence of expected profits. Specifically, if the average WTA in a question is higher than that from its preceding question, there is evidence that expectations serve as reference point.

Indeed, the responses do seem to be influenced by the introduction of an expected profit, as reported in the last three rows in . The results show that sellers adapt their WTA towards the expected profit, regardless of its size, suggesting that expectations influence the behavioural biases of sellers in the property market. By performing matched two sample t tests on the responses, it is possible to determine whether the reported WTAs differ significantly from SET predictions. illustrates that for all levels of expected profits, the observed differences are statistically significant at the 1% significance level.

5.5. Hypothesis 5: social norms influence reference point formation

EquationEquation (4)(4)

(4) is estimated by using OLS for each of the behavioural biases calculated based on Questions 1 − 13. The dependent variable for each model was the difference in WTP/WTA caused by the introduction of each new piece of information. Social norm variables are the key independent variables in this analysis. Participants were also asked a series of basic demographic questions which were used to control for these characteristics during the regression. Since the answers to these questions consisted primarily of categorical data, we translate them into a series of dummy variables (see for variable definitions and descriptive statistics). Regression results are reported in for sellers, buyers (owners) and buyers (renters) respectively. The discussions in this section are based on coefficient estimates that are statistically significant at the 10% level or lower, as highlighted with asterisks in the tables. Three observations can be drawn from these models.

First, the behavioural bias is primarily psychological and can only be marginally explained by observable demographics factors. This is evident from the low R squares reported for all models. Specifically, these factors can explain between 8.88% to 18.85% of the variation of the observed behavioural bias. As the data were generated in a controlled environment that allows little room for other confounding factors, we conclude that the observed bias is indeed primarily due to the psychological responses to each of the reference dependence determinants introduced in the experiments.

Second, the size of the effect of demographic factors is not negligible. For example, males and older people are more rational in housing decisions in general; higher education attainment seems to help reducing the size of bias for both sellers and buyers. The absolute values of these coefficient estimates are all greater than one, which translates to 100% changes from the base category due to the natural log transformation of the dependent variables. The moderating effect of these demographic factors on behavioural bias is economically significant. Note that the proportion of female respondents is high in all three subsamples (see ). Therefore, it is possible that some of the behavioural biases identified in our sample, such as the effect of initial purchase price on sellers in a decreasing market, are over-estimated.

Finally, social norms can influence the size of behavioural bias, but the size of the social norm effect is relatively small among homeowners. We examine the influence of social norms by identifying possible social groups to compare with (i.e. variables SOCIAL1 – SOCIAL5, representing a close friend, a colleague, a neighbour, a family member, or oneself in the past respectively) and the level of social comparison (i.e. variables FRE1 and FRE2 to measure the frequency of comparison, and IMP to measure the importance of social comparison to each individual). We find that comparing to a neighbour actually leads to the smallest behavioural biases among all social groups considered. This pattern holds true for all homeowners (sellers or buyers). Using other social groups tends to increase behavioural bias in housing decisions, but the pattern is weaker. On the other hand, comparison frequency does not affect the size of the bias, but the self-reported importance of social comparison does. This is particularly true for buyers (owners), because the coefficient estimate of IMP is positive and significant in five of the eight models estimated. The size of these coefficient estimates, albeit statistically significant at the 10% level, are generally smaller than that of the demographic factors. For example, the coefficient estimate of IMP in the first model in is 0.24. Because the standard deviation of IMP is 2.70 for sellers, a one standard deviation change in IMP will lead to a 64.8% change in the bias caused by initial purchase prices. This is small when compared with the coefficient estimates of most of the demographic factors.

The effect of social norms on behavioural biases is different for renters in both direction and magnitude. Firstly, comparison frequency has a negative relationship with behavioural biases, which means individuals who make more frequent social comparisons are less reference dependent. Second, the effect of comparison frequency variables is larger than that of control variables. We do not identify a clear pattern among the regression models reported in . One of many possible reasons is that on average renters are younger and inexperienced. This makes them more susceptible to psychological biases. It is also an indication that renters’ response to social norms may be different from homeowners, although we do not observe any differences between homeowners and renters in other aspects of our analysis.

In summary, we found some weak support for Hypothesis 5 and conclude that social norms may influence reference point formation. A qualification to this conclusion is that social norms seem to be more influential for certain reference points – specifically the reference points that are formed from new and contemporary information, such as a recent transaction price or an alternative offer price. However, this conclusion does not hold for the renter group, where more empirical investigation is needed for further verification.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents a controlled experiment to gain insight into reference dependence in the UK housing market. We use an online panel platform to conduct experiments with potential home buyers and sellers in the UK. Both homeowners and renters are included in our sample. The results of the experiment clearly indicate that buyers and sellers in the UK housing market use the initial purchase price, intermediate prices, recent prices, and expected profits as reference points, leading to seemingly irrational deviations in WTP/WTA. We also find some weak evidence that an individual’s propensity to compare their lifestyle to others can influence the formation of their reference points.

We hope our study will encourage more empirical investigations of reference point dependence in housing markets. Although reference dependence is by far the most extensively explored behavioural topic in housing economics, the number of publications is still too small to rule out publication bias, i.e. a result of any tendency to publish only statistically significant findings and replications. In order to verify whether the effect of a given behavioural factor is really significant, a good number of replications is necessary. This has not yet been achieved in the study of reference dependence in housing decisions. To illustrate, whilst Kahneman & Tversky (Citation1979) is the most cited paper in the publication history of Econometrica, with over 22,000 citations in the Web of Sciences database as of February 2021, we found the number of papers using prospect theory to test reference dependence in the housing market is only 13.

To move forward, the next step is to investigate the relationship between identified reference points. The objective of our study is to confirm the presence of multiple reference points in housing markets. Our experiment design does not allow the assessment of the relative importance (i.e. the weights) of identified reference points. Baucells et al. (Citation2011) is a good framework for such analysis. However, it is difficult to implement in online experiments because of the length of the questionnaires. For example, respondents in Baucells et al. (Citation2011) had to answer 60 questions, each of which is based on a series of initial, intermediate, and current prices of a stock. Although the design facilitates the estimation of the weights of multiple reference points, it is very demanding to implement outside of a laboratory where respondents can be supervised to fully engage in the experiment. There is a delicate balance to strike between internal and external validity in behavioural housing economics, and this is a good example of such a challenge.

Finally, behavioural housing studies is not a replacement for, or even a challenge to, established knowledge of housing market economics, which is largely based on the SET. To the contrary, it helps us to better understand housing decision processes by making sense of seemingly irrational behaviours in housing markets. Researchers have already noted asymmetric patterns among housing market agents at different stages of housing cycles decades ago (e.g. Evans, Citation2004; Meen, Citation2002; Muellbauer & Murphy, Citation1997). What is missing is a convincing explanation of these anomalies, which are still the topics of ongoing debates (see, for example, Alqaralleh, Citation2019; Alqaralleh & Canepa, Citation2020; Andre et al., Citation2019; Hu & Lee, Citation2020; You, Citation2020). Prospect theory is a potential solution, because its assumption of different responds in the loss and gain domain (e.g. loss aversion) fits the behaviours in housing markets nicely. However, to test the presence and effects of loss aversion in housing decision making process, the first step is the reliable identification of reference points. Building on this paper’s application of novel reference points to the UK property market, research into newly considered reference points can be integrated into existing housing models to enhance their predictive power. Therefore, our study is part of the effort to take us from we have already known (e.g. the importance of expectations in housing decisions) to what we may learn based on new theories (e.g. a behavioural explanation of asymmetric patterns in housing prices).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the financial support from the Economic and Social Research Council (Grant No. ES/P004296/1), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71661137009), the Cambridge University Land Society, Department of Land Economy Research Development Fund, and Newnham College Senior Member Research Fund.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 The filters are not visible to potential participants and works on existing information in user profiles. Hence workers (i.e., members to answer questionnaires at Prolific) cannot change their profile in order to meet the selection criteria in a specific experiment.

2 We divided the sample into male and female subsamples and explored whether there is a significant gender divide. We found that the two subsamples are similar in most demographic, social, and economic aspects, and empirical results by gender are consistent with those based on the whole sample. Results of these gender analyses are available from the authors upon request.

References

- Alqaralleh, H. (2019) Asymmetric sensitivities of house prices to housing fundamentals: Evidence from UK Regions, International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 12, pp. 442–455.

- Alqaralleh, H. & Canepa, A. (2020) Housing market cycles in large urban areas, Economic Modelling, 92, pp. 257–267.

- Andre, C., Gupta, R. & Muteba Mwamba, J. W. (2019) Are housing price cycles asymmetric? Evidence from the US states and metropolitan areas, International Journal of Strategic Property Management, 23, pp. 1–22.

- Andrew, M. & Larceneux, F. (2019) The role of emotion in a housing purchase: An empirical analysis of the anatomy of satisfaction from off-plan apartment purchases in France, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 51, pp. 1370–1388.

- Anenberg, E. (2011) Loss aversion, equity constraints and seller behavior in the real estate market, Regional Science and Urban Economics, 41, pp. 67–76.

- Arbel, Y., Ben-Shahar, D. & Gabriel, S. (2014) Anchoring and housing choice: Results of a natural policy experiment, Regional Science and Urban Economics, 49, pp. 68–83.

- Arbel, Y., Fialkoff, C. & Kerner, A. (2016) Does the first impression matter? Efficiency testing of tenure-choice decision, Regional Science and Urban Economics, 60, pp. 223–237.

- Ariely, D. & Zauberman, G. (2000) On the making of an experience: The effects of breaking and combining experiences on their overall evaluation, Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 13, pp. 219–232.

- Arkes, H.R., Hirshleifer, D., Jiang, D. & Lim, S. (2008) Reference point adaptation: Tests in the domain of security trading, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 105, pp. 67–81.

- Baucells, M., Weber, M. & Welfens, F. (2011) Reference-point formation and updating, Management Science, 57, pp. 506–519.

- Behrend, T. S., Sharek, D. J., Meade, A. W. & Wiebe, E. N. (2011) The viability of crowdsourcing for survey research, Behavior Research Methods, 43, pp. 800–813.

- Ben-Shahar, D. & Golan, R. (2014) Real estate and personality, Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 53, pp. 111–119.

- Bolton, L. E., Warlop, L. & Alba, J. W. (2003) Consumer perceptions of price (un)fairness, Journal of Consumer Research, 29, pp. 474–491.

- Bucchianeri, G. W. & Minson, J. A. (2013) A homeowner's dilemma: Anchoring in residential real estate transactions, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 89, pp. 76–92.

- Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T. & Gosling, S. D. (2011) Amazon's Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data?, Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 6, pp. 3–5.

- Camerer, C., Babcock, L., Loewenstein, G. & Thaler, R. (1997) Labor supply of New York City cabdrivers: One day at a time, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112, pp. 407–441.

- Campbell, M. C. (1999) Perceptions of price unfairness: Antecedents and consequences, Journal of Marketing Research, 36, pp. 187–199.

- Cardoso, R., Meijers, E., van Ham, M., Burger, M. & de Vos, D. (2019) Why bright city lights dazzle and illuminate: A cognitive science approach to urban promises, Urban Studies, 56, pp. 452–470.

- Casler, K., Bickel, L. & Hackett, E. (2013) Separate but equal? A comparison of participants and data gathered via Amazon's MTurk, social media, and face-to-face behavioral testing, Computers in Human Behavior, 29, pp. 2156–2160.

- Černý, A. L. E. Š., Miles, D. & Schmidt, L. (2010) the impact of changing demographics and pensions on the demand for housing and financial assets, Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 9, pp. 393–420.

- Chandler, J., Mueller, P. & Paolacci, G. (2014) Nonnaïveté among Amazon Mechanical Turk workers: Consequences and solutions for behavioral researchers, Behavior Research Methods, 46, pp. 112–130.

- Clark, W. A. V. & Lisowski, W. (2017) Prospect theory and the decision to move or stay, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114, pp. E7432–E7440.

- Clayton, J., Geltner, D. & Hamilton, S. W. (2001) Smoothing in commercial property valuations: Evidence from individual appraisals, Real Estate Economics, 29, pp. 337–360.

- Crone, D. L. & Williams, L. A. (2017) Crowdsourcing participants for psychological research in Australia: A test of microworkers, Australian Journal of Psychology, 69, pp. 39–47.

- Difallah, D., Filatova, E. & Ipeirotis, P. (2018) Demographics and Dynamics of Mechanical Turk Workers, Wsdm'18: Proceedings of the Eleventh Acm International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Marina Del Rey, CA, pp. 135–143.

- Dunning, R. J. (2017) Competing notions of search for home: behavioural economics and housing markets, Housing, Theory and Society, 34, pp. 21–37.

- Einio, M., Kaustia, M. & Puttonen, V. (2008) Price setting and the reluctance to realize losses in apartment markets, Journal of Economic Psychology, 29, pp. 19–34.

- Evans, A. W. (2004) Economics, Real Estate and the Supply of Land (Chicester, UK: John Wiley and Sons Ltd.).

- Evans, J. (2017) Home ownership in England falls to 30-year low, Financial Times. 2 March 2017. https://www.ft.com/content/90fb85a8-ff5d-11e6-8d8e-a5e3738f9ae4.

- Fehr, E. & Goette, L. (2007) Do workers work more if wages are high? Evidence from a randomized field experiment, American Economic Review, 97, pp. 298–317.

- Genesove, D. & Mayer, C. (2001) Loss aversion and seller behavior: Evidence from the housing market, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, pp. 1233–1260.

- Goethals, G. R. (1986) Social comparison theory: Psychology from the lost and found, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 12, pp. 261–278.

- Goodman, J. K. & Paolacci, G. (2017) Crowdsourcing consumer research, Journal of Consumer Research, 44, pp. 196–210.

- Hirota, S., Suzuki-Löffelholz, K. & Udagawa, D. (2020) does owners' purchase price affect rent offered? Experimental evidence, Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 25, pp. 100260.

- Hu, M. R. & Lee, A. D. (2020) Outshine to outbid: Weather-induced sentiment and the housing market, Management Science, 66, pp. 1440–1472.

- Hung, M. W. & So, L. C. (2012) How much extra premium does a loss-averse owner-occupied home buyer pay for his house?, The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 45, pp. 705–722.

- Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A. (1979) Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk, Econometrica, 47, pp. 263–291.

- Klamer, P., Bakker, C. & Gruis, V. (2017) Research bias in judgement bias studies - A systematic review of valuation judgement literature, Journal of Property Research, 34, pp. 285–304.

- Leung, T. C. & Tsang, K. P. (2013) Anchoring and loss aversion in the housing market: Implications on price dynamics, China Economic Review, 24, pp. 42–54.

- Levy, D. S., Frethey-Bentham, C. & Cheung, W. K. S. (2020) Asymmetric framing effects and market familiarity: Experimental evidence from the real estate market, Journal of Property Research, 37, pp. 85–104.

- Linde, J. & Sonnemans, J. (2012) Social comparison and risky choices, Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 44, pp. 45–72.

- Maclennan, D. (1982) Housing Economics: An Applied Approach. New York: Longman.

- Marsh, A. & Gibb, K. (2011) Uncertainty, expectations and behavioural aspects of housing market choices, Housing, Theory and Society, 28, pp. 215–235.

- Meen, G. (2002) The time-series behavior of house prices: A transatlantic divide?, Journal of Housing Economics, 11, pp. 1–23.

- Mori, M., Diaz, J., Ziobrowski, A. J. & Rottke, N. B. (2010) Psychological and cultural factors in the choice of mortgage products: A behavioral investigation, Journal of Behavioral Finance, 11, pp. 82–91.

- Morrison, P. S. & Clark, W. A. V. (2016) Loss aversion and duration of residence, Demographic Research, 35, pp. 1079–1100.

- Muellbauer, J. & Murphy, A. (1997) Booms and Busts in the UK housing market, The Economic Journal, 107, pp. 1701–1727.

- Paraschiv, C. & Chenavaz, R. (2011) Sellers' and buyers' reference point dynamics in the housing market, Housing Studies, 26, pp. 329–352.

- Peer, E., Brandimarte, L., Samat, S. & Acquisti, A. (2017) Beyond the Turk: Alternative platforms for crowdsourcing behavioral research, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 70, pp. 153–163.

- Porter, C., Outlaw, R., Gale, J. P. & Cho, T. S. (2019) The use of online panel data in management research: A review and recommendations, Journal of Management, 45, pp. 319–344.

- Rabin, M. (2002) A perspective on psychology and economics, European Economic Review, 46, pp. 657–685.

- Ramsey, S. R., Thompson, K. L., McKenzie, M. & Rosenbaum, A. (2016) Psychological research in the internet age: The quality of web-based data, Computers in Human Behavior, 58, pp. 354–360.

- Scott, P. J. & Lizieri, C. (2012) Consumer house price judgements: New evidence of anchoring and arbitrary coherence, Journal of Property Research, 29, pp. 49–68.

- Seiler, M. J., Seiler, V. L., Traub, S. & Harrison, D. M. (2008) Regret aversion and false reference points in residential real estate, Journal of Real Estate Research, 30, pp. 461–474.

- Simonsohn, U. & Loewenstein, G. (2006) Mistake #37: The effect of previously encountered prices on current housing demand, Economic Journal, 116, pp. 175–199.

- Smith, S. J. (2011) Home price dynamics: A behavioural economy? Housing, Theory and Society, 28, pp. 236–261.

- Sun, H. & Ong, S. E. (2014) Bidding heterogeneity, signaling effect and its implications on house seller's pricing strategy, The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 49, pp. 568–597.

- Viglia, G. & Abrate, G. (2014) How social comparison influences reference price formation in a service context, Journal of Economic Psychology, 45, pp. 168–180.

- Wang, M., Bao, H. X. H. & Lin, P. T. (2015) Behavioural insights into housing relocation decisions: The effects of the Beijing Olympics, Habitat International, 47, pp. 20–28.

- Watkins, C. & McMaster, R. (2011) The behavioural turn in housing economics: Reflections on the theoretical and operational challenges, Housing, Theory and Society, 28, pp. 281–287.

- Yan, J. H. & Bao, H. X. H. (2018) A prospect theory-based analysis of housing satisfaction with relocations: Field evidence from China, Cities, 83, pp. 193–202.

- Yang, Z., Fan, Y. & Zhao, L. Q. (2018) A reexamination of housing price and household consumption in China: The dual role of housing consumption and housing investment, The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 56, pp. 472–499.

- You, T. W. (2020) Behavioural biases and nonlinear adjustment: Evidence from the housing market, Applied Economics, 52, pp. 5046–5059.