Abstract

Expanded state-subsidised housing programmes in middle-income countries raise questions about the displacement and socio-spatial marginalisation of poor households. Examining these questions through people’s experiences of resettlement indicates the importance of mobility to their lives. Drawing on a mixed-method comparative study of Ahmedabad, Chennai and Johannesburg, we ask: How does the relocation of low-income households to urban peripheries reshape the links between their physical and socio-economic mobility, and how does this impact on their ability to build secure urban futures? Experiences of families moving to five peripheral settlements indicate two linked challenges to the social and economic mobility of the peripheralised urban poor: first, their immediate and individual ability to be mobile within the city and second, the longer-term social mobility of their households. While trajectories towards secure urban citizenship for all remain a policy aspiration, housing policies and practices are placing this on hold or even reversing this, with mobility constraints locking many low-income groups into marginality.

1. Introduction: Peripheral relocation and (Im)mobility

Many cities in middle-income countries are witnessing significant expansions in the production of state-subsidised housing, at a scale that is relocating millions of people. Their promise is to deliver housing, infrastructure and services that meet universal standards of decency and sustainable human settlements and, at the same time, to replace informal tenure arrangements, services, and governance with legible and governable urban environments (Patel, Citation2016). The danger is that delayed or partial implementation of this promise can itself contribute to the marginalisation of low-income city dwellers. The move to formal housing, much of which is being developed on the edges of cities, can also differentially expose residents to new financial risks, spatial dislocation, and the disruption of jobs and livelihoods. We argue here that (im)mobility is central to how this risk is experienced, with relocation potentially locking them into places that are peripheral to and marginalised from the rest of the city.

This paper builds on previous work highlighting the tensions low-income groups experience as they transition into formal settlements. Our central question is How does the relocation of low-income households to urban peripheries reshape the links between their physical and socio-economic mobility, and how does this impact on their ability to build secure urban futures? The linkages between physical and socio-economic mobility are particularly important for low-income urban households. Physical access to work and key services that are tied to particular locations is crucial to sustaining livelihoods, for example by allowing households to stitch together marginal jobs that require their physical presence. This access is underpinned by physical mobility, spanning from small-scale movement to much larger forms of travel. Relocation to peripheral housing significantly alters the physical mobility demands on low income households, and can increase travel costs and times to critical everyday locations such as workplaces and schools, and potentially fracture existing socio-spatial networks. As a result, physical mobility is centrally and intimately constitutive of people’s experience of place, and where relocation disrupts this, it risks significantly constraining their longer-term socio-economic mobility. By evidencing low-income households’ experiences of relocation through a three-city study (Ahmedabad, Chennai, Johannesburg), the wider contribution of this paper is to use residents’ (im)mobility to raise critical questions about the long-term socio-economic impacts of their rehousing.

The peripheries of cities in the Global South are diverse and shaped by a variety of processes and drivers, but academic engagement with them has been somewhat selective. As Coelho et al. (Citation2020) note, they are often understood as places where agricultural hinterlands are being turned into urban real estate: this focus on an investment frontier emphasises high-end enclave development of industrial estates, gated communities and luxury townships (for India, see Raman, Citation2016; Balakrishnan, Citation2019; Gururani, Citation2018; Vijayabaskar & Varadarajan, Citation2018). Alternatively, when low-income groups are studied, the periphery is seen as a space of auto-construction (Caldeira, Citation2017) and in-situ urbanisation, where informal settlements dominate (Desai et al., Citation2020). The role of formal low-income housing projects and their distinctive roleFootnote1 in reshaping the urban periphery is largely missing in these accounts. This absence is surprising given that the 21st century has seen a range of middle-income countries, from Argentina to Indonesia, embarking on a new generation of housing programmes. Each of these promises to deliver many hundreds of thousands of units through various forms of state support (Buckley et al., Citation2016a, Citation2016b), dwarfing the ambitions of equivalent programmes present from the 1960s (Jenkins et al., Citation2007). The vast majority of this housing is being built in the peripheries of large cities, with the industrial scale of projects “dangerously echoing past failures of social housing as witnessed in the post-World War II era in European and American cities” (Buckley, Citation2016a, p.120). This wider global trend suggests that the (re)expansion of state-supported low-income housing programmes has become an important mode of urbanisation in its own right. With affordability of delivery driving city-edge locations, questions of mobility become central to the experiences of their relocated inhabitants, and the wider sustainability of this form of urbanisation.

This trend is well exemplified in both countries represented here. South Africa’s post-apartheid Constitution promises to produce decent homes for all, and this has driven delivery of over 3 million housing units to first-time owners since 1994. These have predominantly been detached houses on fully-serviced plots in new developments (supplemented by the transfer of some existing state housing stock), gifting freehold ownership to qualifying citizensFootnote2. Within a wider context of very high unemployment, this programme has assumed great practical and political importance with the legal and formal status of this housing also being tied in policy terms to the idea that housing can provide a pathway to secure urban living. A persistent backlog of potential recipients has, however, meant continued tensions between quality, cost and location of the housing delivered. Increasing political pressure to tackle this backlog has resulted in national government’s calls to accelerate delivery primarily through the building of ‘megaprojects’ of over 15,000 units. This threatens to reproduce the existing dominance of city-edge sites (Ballard & Rubin, Citation2017), which often work against city-level strategic spatial planning objectives seeking to address mobility constraints through densification and transport-oriented development.

India too has seen a recent step-change in low-income housing projects within a broader policy context concerned with including marginalised groups, but primarily focused on capturing land value and the potential for urban development. As India’s market liberalisation has gradually extended to its real estate sector ( Shatkin & Vidyarthi, Citation2013; Goldman, Citation2011; Balakrishnan, Citation2019), some inner-city informal settlements have become prime sites for commercial redevelopment. Since the 2000s, new national initiatives have offered cities additional finance to invest in key urban infrastructure and build subsidised housing for those being displaced from slums, with the current target being delivery of 20 million affordable houses by 2022. Although these initiatives recognise the desirability of in situ rehousing, well-located sites can be developed for more profitable purposes, and housing delivery for those being resettled is dependent on cheap land. Subsidised housing, usually in the form of apartments within multi-storey blocks, is seen as a private good to be delivered at minimum cost. Again, scaled-up delivery has increasingly gone hand-in-hand with city-edge locations, with the tacit assumption that the resultant mobility costs can be passed on to those being relocated in return for the security formal housing delivers.

The production of this housing, in these instances and more widely, is moving large numbers of poorer people to the urban periphery. Their experiences of relocation are central to this paper’s evaluation of how this spatial reconfiguration is reshaping crucial links between physical and socio-economic (im)mobility for low-income urban households. Kleinhans & Kearns (Citation2013) argue that any evaluation of relocation needs to consider its policy, context, process and outcomes, and they specifically question work that takes ‘displacement’ as its framing, arguing that this term fits people’s experiences into pre-structured narratives of loss (c.f. Atkinson, Citation2004). Writing against such accounts may be seen as contentious (or even reactionary) to academics actively engaged with residents’ battles to stay in place both in the Global North and the Global South (see, among others Bhan & Menon-Sen, Citation2008; Bhan, Citation2016; Doshi, Citation2011; HLRN (Housing & Land Rights Network), Citation2019). However, being open to the potentially mixed and uneven outcomes of relocation is important if we are to understand the complexity of changes in residents’ lives after they have moved (Coelho et al., Citation2012; Lemanski et al., Citation2017; Charlton, Citation2018; Wang, Citation2020).

We build on Kleinhans & Kearns’ (Citation2013) call to capture the context-specific and contradictory outcomes of state-directed relocation through what Meth et al. (under review) term ‘disruptive re-placement’ - the challenges that low-income households face in place-making in a new setting. This highlights both the trauma of moving itself, but also people’s affective need to feel settled in their new location, elevating residents’ efforts and strategies to forge new lives, and the difficulties they face in doing so. Their framing is particularly attuned to conditions in our Indian and South African cases. First, as with Kleinhans and Kearns’ work, Meth et al. deliberately extend analysis beyond the delivery of housing itself, seeing re-placement as a process of rebuilding economic and social networks that have suffered disconnection. Their focus on the global South, however, emphasises the roles and unintended consequences of state-driven ‘developmental’ agendas. These may be tied to ideals of decency and changed living practices that residents may themselves attempt to uphold (Charlton, Citation2018; Pancholi, Citation2020; Patel, Citation2016), but alongside gains in privacy, space and security (Meth et al, under review), the practical experience of relocation into state housing is often marred by poor quality construction and soaring costs, producing ‘marginalised formalisation’ (Meth, Citation2020). Second, they highlight the spatiality of re-placement. The urban periphery offers a settled place in the city that is not intrinsically disadvantaged: it can be made liveable, but only if supported through integrated planning, independent forms of mobility or alternative forms of connectivity. Where these are not present, as is often the case for poorer households, the periphery is experienced as a challenging location, distant and under-serviced. Finally, they raise important questions of temporality: how long do the effects of disruption last for residents, are they being moved to places that are still ‘incompletely urban’, and to what extent is this politically justifiable if it holds open the possibility of a better future?

We use mobility as a lens to exemplify and extend this idea of disruptive re-placement, because it provides a bridge between the production of low-income housing and people’s experiences of re-establishing their lives within the urban periphery. As noted above, our interest in mobility is driven by the importance to poorer urban households of direct, physical access to work and key services that are fixed in particular locations. Our work is informed by the ‘new mobilities paradigm’ and in particular by Cresswell’s (Citation2006; Citation2010) analysis of mobility as movement, representation and practice. This extends the term beyond what Ernste et al. (Citation2012) call ‘transport mobility’, or “perceiving mobility [as] a way to overcome the friction of distance and a functionalist force… (re)structuring the urban landscape” (p.509), to a broader ‘practice mobility’ that sees mobility as significant within place-making, and in shaping the experience and identities of those who move (and of those who are rendered immobile: Cresswell, Citation2012; Straughan et al., Citation2020). As such, Cresswell’s triad opens up inherently political questions about movement (who moves?) representation (how is movement constructed?) and practice (how is mobility embodied?) that can directly address mobility’s links to issues of inequality and governmentality.

These broader politics of mobility have long been a subject of study in the global South, where researchers have addressed differential access to mobility (Venter, Citation2007; Lucas, Citation2011; Mahadevia, Citation2015), the vital and often hidden role of mobility within marginal livelihoods (Dierwechter, Citation2004; Esson et al., Citation2016), and the value of non-motorised and informal transport to the urban poor (Srinivasan & Rogers, Citation2005). Priya Uteng & Lucas (Citation2018) contribute to this tradition of critical scholarship, showing the new mobilities paradigm’s reach into contexts beyond its explicitly Western roots (Cresswell, Citation2006), and highlighting the vital links that exist between physical and socio-economic mobility. They argue that within dominant approaches to transport policy in the Global South, understandings of movement focus on developing (car-enabling) infrastructure, representations of mobility are driven by the aspirations of a globalised ‘middle class’, and the mobility practices of the urban poor are ignored. The resulting discrepancies in physical mobility can materially and significantly curtail the right to the city for those that this marginalises, identifying mobility as an important issue of social justice (Ernste et al., Citation2012). These criticisms have important echoes in our work, but rather than using a broadened concept of mobility to challenge a narrow, technocentric vision of transport planning in the global South, we want to focus on (im)mobility’s crucial role in place-making for those displaced in state housing projects.

We therefore look at the links between mobility and re-placement in three ways. First, relocation changes mobility needs. Informal housing, while often physically and legally insecure, does offer many people a viable place in the city, where work, home and social networks are often spatially compact. The initial focus of our empirical work thus looks at the moment of disruption: how does the move to the city edge transform the spatial practices of those being relocated? This links to ongoing concerns within the literature on the ‘poor location’ of state-subsidised housing (Todes, Citation2003; Turok, Citation2013), and the inadequacy of transport networks in peripheral areas of the global South (Oviedo Hernandez & Titheridge, Citation2016). Centrally, it recognises that relocation can create new mobility needs, for example by increasing dependency on vehicular transport (Srinivasan & Rogers Citation2005) or disrupting women’s ability to make safe, multi-tasking trips by foot (Mahadevia, Citation2015). Second, day-to-day mobility should allow these new frictions of distance to be overcome, and this therefore provides our second focus: how is mobility experienced within these housing projects – who moves, how, and at what costs, and who is rendered immobile? This links directly to Cresswell’s questions about movement and practice, and builds on critical Southern scholarship that recognises how people’s economic means and intersecting identities (within which gender is an important concern: Alberts et al., Citation2016; Levy, Citation2015) structure mobility outcomes, including the production of immobility and ‘stuckness’ (Straughan et al., Citation2020). Finally, we address the questions of temporality raised by Meth et al.: what are the linkages between current disruption of physical movement and longer-term socio-economic mobility? Here, we use Cresswell’s broader question of representation to take a particular focus on how those being re-placed see their own futures: how are their aspirations of enjoying a secure place in the city being reshaped, or even abandoned, in the face of mobility-based exclusion (c.f. Oviedo Hernandez & Dávila, Citation2016).

2. Methodology and contexts

Our empirical research examined five city-edge low-income housing sites within a generative and open-ended comparative study that used mobility to capture the impacts of relocation within and across households. Team members’ extensive prior research enabled us to place people’s everyday experiences of disruptive re-placement within a wider context of national (and sub-national) housing policy, and city-specific development trajectories. Our specific sites () represented different modes of housing delivery in Ahmedabad, different scales of delivery in Chennai, and a flagship housing ‘megaproject’ in Johannesburg, but all were indicative of wider patterns of rehousing within their respective cities. Additionally, choosing relatively recent relocation sites where most residents had been living for under five years, allowed investigation of individuals and households adjusting to their new homes. Through this, we intended that our cross-sectional work would provide not only a ‘snapshot’ of current mobility challenges, but also an opportunity to explicitly recognise and engage with the dynamism of relocation processes (Kleinhans & Kearns, Citation2013: 169).

Table 1. Case study sites.

Within this overall comparative framing, primary data collection followed a mixed-methods approach that was undertaken in parallel across all five sites. This began with a questionnaire survey on day-to-day mobility and the effects of relocation, conducted with a randomly-sampled group of 100 households per cityFootnote3. Follow-up qualitative work with a purposively-selected sub-set of questionnaire respondents from each settlement allowed further in-depth insights into how household composition impacted on these experiencesFootnote4. This was further supported with direct observations of everyday living conditions and mobility experiences of different age groups and gender in all five sites and interviews with ‘resource persons’ involved in transport provision in each. Before addressing these experiences, we place our case study sites within their broader city contexts.

2.1. Ahmedabad

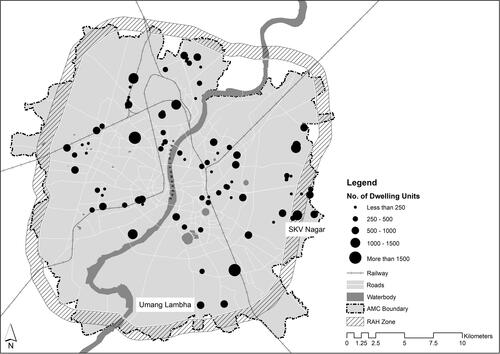

Ahmedabad city is split between middle-class and elite western suburbs, and low-income housing in its industrial east. The latter has grown through ‘informal commercial sub-divisions’ (Desai et al., Citation2020), conversions of farmland to low-cost and partially-serviced housing. Informal housing has also long been present on vacant state-owned lands, the largest concentration being on the Sabarmati Riverfront. In the 1990s, its municipal government undertook an innovative in-situ upgrade programme in collaboration with NGOs and slum residents (Mahadevia et al., Citation2018), but from 2005 these efforts stopped following a changed national policy context. The JNNURM, a national urban renewal programme, increased both supply and demand for publicly-provided housing. It funded infrastructure projects like road-widening, flyover-construction, and a bus rapid transit system that displaced low-income households on a huge scale: an estimated 21,480 households were evicted from the city between 2005 and 2017, with the Sabarmati Riverfront Project alone displacing around 12,000 households (Desai et al., Citation2018). Simultaneously, JNNURM’s funding for low-income housing delivered 33,000 housing units between 2007 and 2012, but 70% of public housing built since 2010 is located on the periphery (Mahadevia, Citation2019, see ). While national policy theoretically supports in-situ redevelopment, Ahmedabad’s Master Plan has created a Residential Affordable Housing zone in a 1 km band around its outer ring road: over 90% of planned future low-income housing will be built in these cheaper city-edge sites, further locking-in peripheralisation.

Our case study sites reflect these wider trends within the city: both are located in the eastern periphery, but within the ring road. One is a JNNURM-funded project on municipal land. The other reflects Gujarat’s own experiments with delivering low-income housing through the market, being an estate for low-income ‘first time buyers’, where a local NGO helped to find clients, connect them with the developer, and broker finance for them (through government-subsidised mortgages).

2.2. Chennai

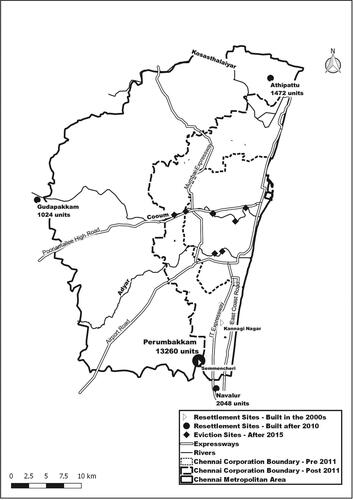

Chennai has a longer history of direct state action in affordable housing and slum clearance, boosted by the creation of the Tamil Nadu Slum Clearance Board (TNSCB) in 1971. The TNSCB experimented with constructing in-situ rehousing tenements, before building a series of sites and services schemes in north Chennai. By 1994 these had provided over 57,000 plots which have become ‘thriving and inclusive neighbourhoods’, mixed-class and mixed-use with a ‘human scale urban fabric’ (Owens et al., Citation2016: 36), and among Chennai’s most successful examples of public housing (Coelho, Citation2016). In the late 1990s, however, slum resettlement changed to state-built, mass-scale tenements outside the city, driven by increasing pressures on urban land for infrastructure and waterways restoration, and by the availability of large-scale funding first from the World Bank, and then from the national government under the JNNURM (Coelho, Citation2016). Nearly 24,000 of Chennai’s 25,000 JNNURM-funded units were peripherally-located resettlement tenements (Venkat & Subadevan, Citation2015), and the bulk of 50,000+ units constructed by TNSCB since 2000 are on the city’s southern outskirts. Although these sites are presented as ‘integrated townships’ equipped with schools, hospitals, crèches and playgrounds, in reality these amenities are often, at best, installed several years after households are resettled.

Our case studies again reflect these shifts to sites offering cheap land (): Perumbakkam, one of Chennai’s largest resettlement colonies, is located at its southern edge and Gudapakkam lies beyond the metropolitan area’s western boundary. A significant proportion of the almost 24,000 houses built in Perumbakkam are currently empty, awaiting further evictions from inner-city slums. In contrast to Ahmedabad, the state remains the predominant supplier of low-income housing in Chennai: efforts to mandate or incentivise the private sector to build affordable housing have failed to yield results.

2.3. Johannesburg

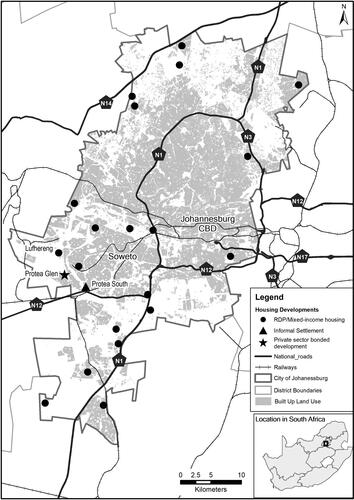

Johannesburg’s housing challenges include under-serviced townships, multiple informal settlements, and squatting and overcrowding within some inner-city buildings. From 2000, its new unitary Municipal government sought to improve apartheid-era townships and since then, its strategic plans have stressed spatial reintegration: improving existing housing, whilst using transport investments to support the interlinked goals of connecting low-income areas to sites of economic opportunity (concentrated in the city’s wealthy northern suburbs), containing sprawl, and increasing density (Ballard & Rubin, Citation2017). This agenda has been challenged by attempts to address Johannesburg’s housing backlog, which initially saw ‘monocultures’ of low-density housing built at the city-edge, reproducing existing spatial marginalisation (Haferburg, Citation2013). City planners have long advocated that state-provided housing should reconnect poorer residents with the city, and have promoted ‘infill’ in well-located sites combined with selective upgrade of informal settlements. With these finer-grained solutions failing to deliver at speed, the Provincial government has taken up the National call for ‘megaprojects’, arguing that massive-scale and mixed-tenure developments will be self-sustaining. Johannesburg’s proposed megaprojects are, however, peripherally located and poorly connected to established areas of economic opportunity (Wray et al., Citation2015).

Our Lufhereng case study lies at Johannesburg’s western municipal boundary, some 25 km from the CBD, and exemplifies these tensions (). Under construction since 2008, it falls outside the City’s designated public transport investment corridors, but is seen by Provincial planners as a natural extension of Soweto and is now a flagship ‘megaproject’. Planned to contain over 20,000 houses, a third for mortgage-linked sale to middle-income families, it is intended to catalyse private sector-led investment in the area and local economic opportunities based around agri-processing, light industry, and services (Charlton, Citation2017). During our field research in 2018, construction of some private sector housing had begun, but the only occupied units were around 2,500 fully state-subsidised houses for poor households.

Our three cities collectively show the city-level consequences of the renewed push for state-supported housing described by Buckley et al. (Citation2016a, Citation2016b), and its importance in reshaping the urban periphery. Nationally, accelerated housing delivery (in scale and speed) and the relocation of low-income households to the urban periphery has been proposed as an acceptable response to a problem framed as a housing shortage. With the notable exception of City of Johannesburg’s planning ideals, this response has largely overlooked the impact this disruptive re-placement has had on many thousands of relocated residents. It is their experiences of rebuilding their lives at the urban periphery we look at now, using the lens of mobility to focus in turn on the disruption of relocation, everyday experiences of mobility, and their implications for longer-term socio-economic mobility.

3. Life at the periphery: exploring disruptive re-placement through the lens of mobility

3.1. Disruptions: Moving to the city edge

We begin by asking how does the move to the city edge transform the spatial practices of those being relocated? The context of this move significantly differed across our sites: for both Chennai sites, and SKV Nagar in Ahmedabad, this was an unplanned and enforced relocation, with most households being displaced from informal settlements that were well-located within their cities. Households here were predominantly within the Indian government’s category of the Economically Weaker Section: the working poor, employed in a range of largely insecure and lower-skilled jobs.Footnote5 It was only in Umang Lambha, Ahmedabad, that households had expressed a choice to move by purchasing a house, assisted by an NGO that arranged state-subsidised finance. Household incomes of Lambha residents were higher (around double those of our other Ahmedabad site), reflecting their ability to take on a mortgage. Lufhereng residents were different again: the tight income limitations on eligibility for South Africa’s housing subsidy meant that unemployment was far higher than among our Indian participants, with the most commonly reported source of income being social security payments. Given the size of Johannesburg’s housing backlog, many residents had long been waiting for this move, but had no control over either its timing or location.

For the vast majority of our households, relocation was a significant move across their cities. This was most pronounced in Chennai, where most came from city-centre informal settlements, meaning that on average, Perumbakkam residents had moved over 15 km, and those in Gudapakkam over 25 km. This pattern was repeated for SKV Nagar, Ahmedabad, although the absolute distance was lower (12 km) given the city’s smaller size. Residents in Umang Lambha, where relocation was based around assisted purchase of property, had come from a range of locations scattered across Ahmedabad, but concentrated in the southeast. Surprisingly, given existing criticisms of South Africa’s state housing, it was Lufhereng’s residents who had moved least in absolute terms: 71% of households had lived in the Protea South informal settlement (10 – 13kms away), another 9% from plots on the farmland in the immediate vicinity of Lufhereng, and a further 9% came from various parts of Soweto, most relocating from backyard rooms or shared houses.

Transport infrastructure in the destinations was far from ideal. There were bus stops relatively close to all four Indian sites, but walking to these was made hazardous by needing to cross busy highways (in Ahmedabad), and negotiate poorly-lit pathways in all sites (an issue we take up below). A bus terminus 2 km from Perumbakkam ran limited routes to the city, but here and in the other three sites, infrequent services, compounded in Gudapakkam by the need to combine at least two buses to reach most locations, made shared auto-rickshaws an important mode of transport. Lufhereng’s nearest bus (Rea Vaya: Johannesburg’s BRT) and train stops were around 5 km away, making paratransit in the form of kombi taxis (shared minibuses) vital for residents (61% of journeys to work) but the nearest taxi rankFootnote6 was located beyond the settlement, again across a busy highway. The outlier here was Umang Lambha in Ahmedabad, where higher incomes allowed more widespread motorbike ownership. This was the modal transport type for male residents travelling over 2 km, but women were largely dependent on walking or autorickshaws.

These changes in location, and the resulting increased costs and difficulty of transport meant significant changes in employment and schooling for a number of our households across all five sites. In Lufhereng, households relocated from Protea South informal settlement had been living close to Lenasia, a relatively affluent former ‘Indian’ neighbourhood of Johannesburg which had provided opportunities for domestic work that were no longer tenable:

It is far here. I worked for Indians in their homes for some time and we did not earn a lot of money. In Protea South it was enough for food and immediate needs at the time. Now here that money could be used just on transport alone, so I figured that I should stay at home and make other plans.

(Lufhereng Resident)

This statement reflects an underlying pattern of precarious and extremely low-paying work, where a 10 km move fundamentally changes income and expenditure calculations, highlighting the importance of location to low-income residents’ livelihoods. Across all our field sites, the time and cost of longer commutes undermined the viability of the lowest-paid jobs, which were themselves concentrated among women.Footnote7 The most pronounced collective impact of relocation on employment was that of 200 families from central Ahmedabad, workers in its Jamalpur flower market. When they were relocated to SKV Nagar, some continued to make the early morning commute to the market, but around 100 families had instead stopped living in their government housing, choosing instead to illegally rent this out.

Integrating housing with supporting amenities can, of course, increase accessibility and decrease the need for expensive or longer-distance travel. For Lufhereng residents, spazas (small shops, usually informal) were present on site, but there was still a need to travel back to Protea South or to the mall at Protea Glen, some 4kms from Lufhereng, for more major purchases, or to receive welfare payments. The opening of local schools within Lufhereng was an important positive contribution, with our survey recording that 55% of school pupils were now walking to school, significant given the impacts of the high taxi transport costs they faced previously:

I remember last year my neighbour was writing his matric final exams and when he was writing his last paper he had no money to go to school, his grandmother did not have and I also did not have money to give him. He did not write it, because of transport money to Protea South. Can you imagine? He is now not doing anything but smoke nyaope [a narcotic].

(Lufhereng Resident)

In three of our Indian case studies, project design included some on-site amenities. Gudapakkam had space for on-site shops, a primary health centre and anganwadisFootnote8, which, however, were barely functioning over a year after relocation. SKV Nagar was served by travelling food vendors and informal shops set up within flats, but its primary health centre and anganwadi were both vandalised and non-functioning. Umang Lambha, a private development, stood out as having no facilities on site, meaning that residents had to make a journey of around 2 km to make even the most basic of purchases.

Dislocation thus produces new mobility needs, but is also experienced as affective disruption (Kleinhans & Kearns, Citation2013), or feeling out-of-place. Here Lufhereng and Gudapakkam residents expressed alienation from being relocated beyond the city, and needing to make adjustments to the ‘rural’ aspects of their new neighbourhoods.Footnote9 In Gudapakkam, this was particularly commented on by younger adults, for whom the lack of access to urban life – including cinemas, internet centres, and markets –was keenly felt. In Lufhereng, residents expressed their trepidation about being relocated during the early stages of the project, when the site had felt remote and undeveloped:

People did not want to come as they felt that we were being thrown far away, because the thing is we were used to walking by foot to the station at Protea, so now we saw that it was a veldt (grassland)…

(Lufhereng Resident).

3.2. Frictions of distance: Experiencing mobility

We now address how mobility is experienced within these housing projects, using residents’ accounts of their day-to-day travel to examine who moves, how, and at what costs, and who is rendered immobile. Dislocation meant that longer and more arduous journeys were widespread. Lufhereng residents unable to afford taxis walked over 10 km to Protea Gardens mall for services, around 3 hours each way, and limited transport connections meant increased spatial splitting of households to accommodate journeys to school or work. 25 people reported sleeping outside their homes for part of the week, whereas only 9 had done so prior to moving to Lufhereng. Workers in SKV Nagar who retained work in central Ahmedabad markets made a daily 3.30am start to set up their market stalls at 5am, requiring expensive shared-auto rides because no buses were available at that time.

These journeys clearly had impacts on our research participants beyond their time and cost implications. Some families in Chennai had kept children in their existing schools, meaning multiple bus rides, a stretched school day (7am-5pm), and children too tired to study properly. Across our Indian sites, girls could not make these journeys independently, meaning that shifts to local schools (often poorer-quality) or school drop-outs were focused on female students:

The Government girls’ school is not nearby. To go to the nearest government school, I would end up spending INR 40 a day. My family says it is unsafe to walk and they don’t send me in the van as it has too many boys.

(SKV Nagar Resident)

Gender-based threats or exclusion were ubiquitous in shaping the experience of transport usage across our Indian sites. Research team members accompanied women making their commutes from Perumbakkam – which had the best access to public transport of our sites – to understand this for themselves. This meant a dawn/pre-dawn 2 km walk through the housing project’s badly lit access roads to the bus stand, where they were exposed to hostile stares, name-calling and taunts from groups of men. Although buses to central Chennai are frequent, they are crowded: female-only seating is inadequate and women travellers face the near-constant threat of physical molestation by male passengers.

These costs and the gendered risks of using public transport were perhaps to be expected, but we had not anticipated residents’ repeated reference to how fear of crime and violence shaped mobility in and around all five sites. In Lufhereng the walk to the main road to get a taxi was seen as risky early in the morning or after dark: ‘You will scream but no one will come out to help you’ (Lufhereng Resident). Similarly, the approach roads to Umang Lambha, SKV Nagar and Gudapakkam were unpaved, without streetlights and perceived as dangerous. In Perumbakkam, the size and the social problems of the settlement itself were seen as an additional risk, with groups of local men making all residents feel unsafe, particularly after dark: “Here everyone including the children live in fear always.” (Perumbakkam Resident).

The combined result of this was to make mobility not merely uncomfortable, but also highly structured by gender, age and income. Those owning motorbikes in Umang Lambha, or those able to afford taxis in Lufhereng, were mobile whereas others were simply stuck in place: ‘If you do not have money for transport you cannot go anywhere. You need to have enough money for that alone’ (Lufhereng Resident). For many in Lufhereng, violence-based restrictions on mobility were simply a fact of life (with some indicating that conditions were worse in their previous locations), but across our Indian sites, this was experienced as a loss of security that was significantly altering their behaviour:

I have to accompany my son to school; he accompanies me to the market. No one can ever go alone here, especially children and women. I take my son even when I visit relatives and go for shopping nearby.

(SKV Nagar Resident)

The costs of keeping themselves and family members safe fell disproportionately on women, who missed the ease of movement they had in their former neighbourhoods, where they could independently go to the market at any time of day. After being relocated, many reported travelling far less, saying that they had to plan and strategize so much to leave the house – whom to go with, what transportation to take, when to return – that they simply stayed put. Footnote10 This was experienced as a loss of mobility, but also of an independence that was a key part of their former urban lives: one respondent said she felt that “they are boxed inside the area, lost somewhere in the forest” (Gudapakkam Resident).

3.3. Peripheral re-placement and social immobility

Finally, we turn to the linkages between housing, the current disruption of physical movement and longer-term socio-economic mobility. For residents in all our Indian sites, the difficulties of location were clearly compounded by the poor quality of the housing itself, echoing Meth (Citation2020) on marginalised formalisation. Gudapakkam’s apartment blocks had defective water pumps, but many units also had such severe structural problems that electrocution was a real concern during the monsoon:

For the last year the house is leaking…We have complained to many Assistant Engineers and many others, but there has been no response. During the rain, it leaks in the bedroom and spreads over to the switches. I am really scared living with my children in the house.

(Gudapakkam Resident)

In Perumbakkam’s eight-storey blocks, internal lighting and elevators were often not working, compounding the sense many had of being unsafe and isolated. Both Umang Lambha and SKV Nagar suffered from over-flowing septic tanks that left raw sewage in public areas of their sites and contaminated water supplies. This made purchase of drinking water an additional financial burden for residents, reducing their savings and chances of economic mobility.

Beyond these immediate adverse impacts on residents, the longer-term effects of these service failures and poor construction work was to nudge entire projects towards a downward social trajectory. The model intended for these sites was owner-occupation, which was in turn supposed to provide stability and allow a sense of community to develop. This was being undermined in practice through the combination of the mobility challenges residents faced, and these physical problems of the sites: in response, many residents were selling on, renting out, or simply not using their homes, producing new forms of insecure mobility. This was most marked in SKV Nagar: of its 700 units, 29% were vacant, and a further 34% were rented out, leaving only 37% of the original allottees living on the site. Although Gudapakkam largely escaped this problem, residents in the other three sites reported that criminal elements were moving into empty units, using the flats for trafficking of sex workers and sale of drugs and alcohol, further accelerating a downward spiral.

If re-placement is about rebuilding lives and social networks, then the disruption our Chennai and Ahmedabad residents experienced clearly went beyond the ‘teething troubles’ and ‘transitional’ issues expected of moving to new housing. These projects’ lack of public transport and on-site amenities were already driving changes that would lead to inter-generational downward social mobility for many – jobs and schooling foregone, particularly for women and girls – and the criminal problems emerging within them that were stigmatising their entire communities. While services and amenities have improved gradually over time, at least in the Chennai sites (bus services added, streetlights installed, buildings repaired), evidence (from here as well as from other resettlement colonies) suggest that the early years of service inadequacies and the disruptions they caused created significant setbacks and long-term consequences for residents’ pathways out of poverty.

As noted by Kleinhans & Kearns (Citation2013), residents shouldn’t be assumed to be ‘passive’ victims of change, but equally their scope for collective action was undermined by the structural challenges they faced. The only concrete indication we had of their agency in re-shaping place was where a community of expatriate Sri Lankans within Gudapakkam had formed an association and successfully lobbied to move the bus-stand closer to the settlement. In Perumbakkam, efforts (by NGOs and state agencies) to organise residents into associations have had limited success, as distrust and hostility still divide households relocated from various slums across the city.

Lufhereng was clearly in a different dynamic, despite high joblessness and resulting poverty-based immobility. This was aided by better quality housing, but also because many residents experienced an area improving over time. Although the difficulties of commutes forced some people to live away from home for part of the week, households were, in general, valuing and holding on to their housing, giving a far greater stability to the population than was present in Chennai or Ahmedabad. Significantly, this seemed to be resulting in examples of community-based action: volunteer security guards were protecting the settlement (an initiative organised by the African National Congress’s local branch), and traffic lights had been installed to improve safe road crossing in response to a community protest after a school child had been hit and killed by a motorist.

Supporting these incremental changes was the wider promise of Lufhereng as a megaproject – the ‘new city’ in the veldt waiting to emerge around its government housing. The building of the first mortgage-based housing units offered residents a glimpse of this materialising, and provoked reactions from our interview participants that differed across generations. Younger residents were more likely to express feelings of being excluded, bored or marginalised (‘there is no source of inspiration here’: Lufereng Resident): for them, the promised future needed to come sooner, so that their lives were not simply put on hold. By contrast, older residents showed some satisfaction in being ‘settled’ in a stable and respectable place, despite their poverty, and the resulting immobility and relative isolation.Footnote11 Linking these differing reactions is a passivity that reflects these residents’ position as foot soldiers within a wider process of development, where Lufhereng’s low-income housing was hoped to pave the way for more profitable private sector investment. Although a far cry from apartheid-era displacements, this shows a state still willing to place poorer people within a peripheral development whose economic viability is far from secure, and likely a long way in the future.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we have explored the impact of peripheral relocation on low-income groups, developing the concept of disruptive re-placement through mobility to capture the effects of state-backed rehousing projects. Our study shows how relocation was experienced very differently across and within households through the complex ways in which it changes access to jobs, amenities and services. Most residents faced increased times and costs of travel, but poor public transport connections, expensive paratransit options, and the physical risks of moving within and around these housing projects also concentrated the resulting frictions of distance onto the poorest, the unemployed, and onto women. Although the receipt of state-backed housing should secure residents’ right to their cities, practical realisation of this right was undermined by the harassment, fear of assault and absolute poverty that placed serious constraints on their mobility. Generational differences within this experience are worthy of further study: for older people being settled in decent, if peripheral, housing appeared to meet their aspirations more than it did for younger residents who felt keenly disadvantaged by physical separation from urban life and amenities. Importantly, however, for households struggling to adjust to the disruption of relocation, physical immobility fed into downward socio-economic mobility, as evidenced by jobs or schooling foregone, or most dramatically in people renting out or selling on their housing.

In our Indian and South African case studies, housing delivery was clearly not centred around poor people’s ability to resettle, despite this being integral to its practical success. This was partly an issue of policy framing: as long as housing projects are simply seen as responses to a meeting a large numerical shortfall in formal dwelling units (dealing with a backlog), then engagement with people’s everyday practices is always likely to be sacrificed for speed and scale of delivery. Beyond this lie issues of the state’s relationship with housing beneficiaries that warrant further investigation. Our Indian cases pointed to a normalisation of low-quality in housing projects in distant, disconnected locations, producing “ghetto effects” that inhibited processes of place-making, feelings of ownership and belonging, and socio-economic mobility. Here, discriminatory standards were supported by formal housing being presented as state largesse toward squatters, slum-dwellers, migrants, and minorities. The project ideals within South Africa may have embraced more ambitious and mixed-class development, but the only guaranteed deliverable in the here-and-now was decent housing for those on the lowest incomes. Complaint or objection from recipient households was blunted by the widespread and persistent demand for housing, granting the state tacit affirmation for a programme of peripheral development. Until there is more effective representation of residents’ voices, the limitations of the housing projects reviewed here are likely to be repeated over and again.

More widely, our study engages with a new generation of government housing programmes across a range of middle-income countries, opening up a different avenue for critique from the macro-scale questions of affordability, targeting and distribution raised by Buckley et al. (Citation2016a, Citation2016b). Meth et al.’s formulation of disruptive re-placement instead addresses the ambivalent costs and benefits of state-supported housing. As we have shown, linking this to mobility extends the concept’s value, further developing its focus on residents’ experiences and the spatiality and temporality of place-making. Being rehoused is a moment of disruption that creates new mobility needs, and these in turn reshape people’s day-to-day movement and practices. The resulting experiences of (im)mobility are not only important in the here and now, but also in highlighting the links between physical movement and longer-term socio-economic mobility. There is an intimate connection between the questions Cresswell raises about movement and practice (who can move, and how is this movement embodied?), and issues of representation and a right to city. If the burdens of spatial dislocation placed on housing beneficiaries are too severe, and the timelines for improved amenities and connectivity too stretched and uncertain, then residents are unable to re-establish the everyday rhythms of movement needed to sustain themselves. This has lasting effects through disrupted access to education and employment, but also through alienation: making people feel ‘cast out’ from an earlier, more intensely urban existence, and unable to contribute positively to practices of place-making in their new, peripheral locations.

Importantly, this drilling down into experiences of (im)mobility also shows the critical importance of what might at first seem like more micro-scale concerns. It demonstrates that if in situ redevelopment of housing is seen as too expensive a policy option for rehousing poorer people in these countries, peripheral redevelopment does not ‘save’ these costs. Instead, it simply transfers them on to its intended beneficiaries, through longer and costlier journeys to work, reduced access to services, or changed intra-household dynamics (workers living away from home, or diminished mobility for those undertaking reproductive labour). Critical transport scholarship based in the global South has called for all development projects “to have an inbuilt agenda on mobilities – detailing out ‘mobility needs’ and ‘mobility gaps’” (Priya Uteng & Lucas, Citation2018: p.12): we argue that this should also be seen as a central housing issue, particularly across the swathe of middle-income countries currently addressing their housing challenges. This would, in turn, make a series of mobility-supporting practical changes integral to the delivery of housing projects. These would include making sure key amenities such as crèches are available from projects’ inception, linking housing to public transport provision or improved paratransit alternatives, and paying attention within project delivery to the provision of street lighting, paving, safe road crossings and other minor infrastructure that is vital to ‘last mile’ connectivity. These interventions are not high cost in themselves, particularly in comparison to the total sums states are committing to housing development, but they are vitally important in enabling people’s physical access to work and key services, and hence their longer term socio-economic mobility. To ignore them removes the ambivalent promise disruptive re-placement holds, turning it instead into an unequivocally callous act of social and spatial marginalisation.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the residents of all five of our case study settlements and our additional interview respondents for their engagement with our project, and our research assistants Fikile Masikane (Johannesburg), Abhilaasha N (Ahmedabad) and Selva Ziona B (Chennai) for their thorough and sensitive work in collecting the primary data and supporting its analysis.Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the Royal Geographical Society Annual Conference 2019, and at a British Academy Virtual Seminar in February 2021: the constructive comments from participants there, and from the three anonymous reviewers, have been invaluable in refining our arguments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We see these projects as distinctive precisely because they involve a shift – often abrupt or forced – to an already built site, rather than a long engagement with informal auto-construction of housing or settlement: this in turn implies a very different set of social relationships with place (see also Coelho et al., Citation2020).

2 Recipients must be very low-income and not previously property owners.

3 In the empirical material that follows, all descriptive statistics relating to our sites are based around analysis of this data.

4 In all sites, we ensured that those selected for follow-up interviews included female-headed households, and those with female wage-earners and/or school students, to ensure these key groups’ experiences were not ignored.

5 Economically Weaker Section households are defined as earning under INR 25,000 (GBP 270)/month: most individuals in our sample earned under INR 10,000/month, with modal incomes for women being INR 5-6,000.

6 Although kombi taxis reach far beyond the formal bus network, coverage is not even or ubiquitous. Ranks, where vehicles wait for passengers before departing on set routes, are more reliable than intermediate pick-up points, where people will be ignored by vehicles already at capacity. Shared autorickshaws are similarly structured, meaning users must walk to key intersections to board.

7 Even in Perumbakkam, which was best served by public transport, bus passes cost around INR 1000/month – making travel for domestic work (with incomes starting at INR 3000/month) unsustainable.

8 Anganwadis provide pre-school education and childcare, nutrition and health services for mothers and young children across India, particularly for low-income communities.

9 Perumbakkam and our Ahmedabad sites were contiguous with existing urban areas, but this did not stop residents experiencing other forms of disconnection from place: see (Coelho et al., Citation2020) for further details.

10 In Ahmedabad, 56% of women and 40% of men in SKV Nagar didn’t make any regular journeys on a weekday: this gender difference was even more marked in Umang Lambha (60% women versus 32% men).

11 These generational differences were echoed in Gudapakkam: while young people described feeling cut off from the city, an older man commented that the place was suitable ‘for retired people like me…..we can just sit here and complete our remaining life…’ (Gudapakkam Resident).

References

- Alberts, A., Pfeffer, K. & Baud, I. (2016) Rebuilding women’s livelihoods strategies at the city fringe: Agency, spatial practices, and access to transportation from Semmencherry, Chennai, Journal of Transport Geography, 55, pp. 142–151. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2015.11.004

- Atkinson, R. (2004) The evidence on the impact of gentrification: New lessons for the urban Renaissance?, European Journal of Housing Policy, 4, pp. 107–113.

- Balakrishnan, S. (2019) Shareholder Cities: Land Transformations Along Urban Corridors in India (University of Pennsylvania Press).

- Ballard, R. & Rubin, M. (2017) A ‘Marshall Plan’ for human settlements: how megaprojects became South Africa’s housing policy, Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa, 95, pp. 1–31.

- Bhan, G. & Menon-Sen, K. (2008) Swept Off the Map: Surviving Eviction and Resettlement in Delhi (Delhi: Yoda Press).

- Bhan, G. (2016) In the Public’s Interest: Evictions, Citizenship and Inequality in Contemporary Delhi (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press).

- Buckley, R., Kallergis, A. & Wainer, L. (2016b) The emergence of large-scale housing programmes: Beyond a public finance perspective, Habitat International, 54, pp. 199–209.

- Buckley, R.M., Kallergis, A., & Wainer, L. (2016a) Addressing the Housing Challenge: avoiding the Ozymandias Syndrome”, Environment and Urbanization, 28, pp. 119–138.

- Caldiera, T. (2017) Peripheral urbanization: Autoconstruction, transversal logics, and politics in cities of the global South, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 35, pp. 3–20.

- Charlton, S. (2017) Poverty, subsidised housing and Lufhereng as a prototype megaproject in Gauteng”, Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa, 95, pp. 85–110.

- Charlton, S. (2018) Spanning the spectrum: infrastructural experiences in South Africa’s state housing programme, International Development Planning Review, 40, pp. 97–120.

- Coelho, K. (2016) Tenements, ghettos or neighbourhoods? Outcomes of slum-clearance interventions in Chennai, Review of Development and Change, 21, pp. 111–136.

- Coelho, K., Mahadevia, D. & Williams, G. (2020) Outsiders in the periphery: studies of the peripheralisation of low income housing in Ahmedabad and Chennai, International Journal of Housing Policy,

- Coelho, K., Venkat, T. & Chandrika, R. (2012) The spatial reproduction of urban poverty: labour and livelihoods in a slum resettlement colony”, Economic and Political Weekly, 47, pp. 53–63.

- Cresswell, T. (2006) On the Move: Mobility in the Modern Western World (New York: Routledge).

- Cresswell, T. (2010) Towards a politics of mobility, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 28, pp. 17–31.

- Cresswell, T. (2012) Mobilities II: Still”, Progress in Human Geography, 36, pp. 645–653.

- Desai, R., Sanghvi, S. & Abhilaasha, N. (2018) Mapping evictions and resettlement in Ahmedabad, 2000–2017, CUE Working Paper 39, September. Centre for Urban Equity, CEPT University. https://cept.ac.in/UserFiles/File/CUE/Working%20Papers/Revised%20New/CUE%20WP39%20-%20Mapping%20Evictions%20and%20Resettlement%20in%20Ahmedabad%20%282000%20%E2%80%93%202017%29%20-%20%20Sept%202018.pdf.

- Desai, R., Mahadevia, D. & Sanghvi, S. (2020) Urban planning, exclusion and negotiation in an informal subdivision: The case of Bombay Hotel, Ahmedabad, International Development Planning Review, 42, pp. 33–56.

- Dierwechter, Y. (2004) Dreams, bricks and bodies: mapping ‘neglected spatialities’ in African Cape Town, Environment and Planning A, 36, pp. 959–981.

- Doshi, S. (2011) The Right to the Slum? Redevelopment, Rule and the Politics of Difference in Mumbai. Thesis/dissertation submitted to UC Berkeley. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4tx6v6sw.

- Ernste, H., Martens, K. & Schapendonk, J. (2012) The design, experience and justice of mobility, Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 103, pp. 509–515.

- Esson, J., Gough, K., Simon, D., Amankwaa, E., Ninot, O. & Yankson, P. (2016) Livelihoods in motion: Linking transport, mobility and income-generating activities, Journal of Transport Geography, 55, pp. 182.

- Goldman, M. (2011) Speculative urbanism and the making of the next world city, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 35, pp. 555–581.

- Gururani, S. (2018) Frontier urbanism, Economic and Political Weekly, Review of Urban Affairs, 53, pp. 41–45.

- Haferburg, C. (2013) Townships of tomorrow? Cosmo City and inclusive visions for post-apartheid urban futures”, Habitat International, 39, pp. 261–268.

- HLRN (Housing and Land Rights Network). (2019) Report: Forced Evictions in India in 2018: An Unabating National Crisis (New Delhi: Housing and Land Rights Network).

- Jenkins, P., Smith, H. & Wang, J.P. (2007) Planning and Housing in the Rapidly Urbanising World. Series: Housing, planning, and design series (Abingdon, UK: Routledge).

- Kleinhans, R. & Kearns, A. (2013) Neighbourhood restructuring and residential relocation: Towards a balanced perspective on relocation processes and outcomes, Housing Studies, 28, pp. 163–176.

- Lemanski, C., Charlton, S. & Meth, P. (2017) Living in state housing: expectations, contradictions and consequences, Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa, 93, pp. 1–12.

- Levy, C. (2015) “Routes to the just city: towards gender equality in transport planning” in: C. Moser (Ed.) Gender, Asset Accumulation and Just Cities: Pathways to Transformation, pp. 135–149 (Abingdon, UK: Routledge).

- Lucas, K. (2011) Making the connections between transport disadvantage and social exclusion of low income populations in the Tshwane Region of South Africa”, Journal of Transport Geography, 19, pp. 1320–1334.

- Mahadevia, D. (2015) Gender Sensitive Transport Planning for Cities in India (UNEP DTU Partnership, Centre on Energy, Climate and Sustainable Development Technical University of Denmark). http://www.unep.org/transport/lowcarbon/publications.asp.

- Mahadevia, D. (2019) “Unsmart outcomes of the smart city initiatives: displacement and peripheralization in Indian Cities” in: T. Banerjee & A. Loukaitou-Sedris (Eds.) Urban Design Companion: A Sequel, pp. 310–324 (Abingdon, UKRoutledge, Taylor and Francis Group)..

- Mahadevia, D., Bhatia, N. & Bhatt, B. (2018) Private sector in affordable housing? – Case of slum rehabilitation scheme in Ahmadabad, India”, Environment and Urbanization Asia, 9, pp. 1–17.

- Meth, P. (2020) Marginalised Formalisation’: An Analysis of the in/Formal Binary through Shifting Policy and Everyday Experiences of ‘Poor’ Housing in South Africa”, International Development Planning Review, 42, pp. 139–164.

- Meth, P., Belihu, M., Buthelezi, S. & Masikane, F. (under review) Not Always Displacement: conceptualising Relocation in Ethiopia and South Africa as ‘Disruptive Re-Placement’”, Urban Geography.

- Oviedo Hernandez, D. & Dávila, J.D. (2016) Transport, urban development and the peripheral poor in Colombia—Placing splintering urbanism in the context of transport networks, Journal of Transport Geography, 51, pp. 180–192.

- Oviedo Hernandez, D. & Titheridge, H. (2016) Mobilities of the periphery: Informality, access and social exclusion in the urban fringe in Colombia”, Journal of Transport Geography, 55, pp. 152–164.

- Owens, K. E., Guliyani, S. & Rizvi, A. (2016) Success when we deemed it failure: Revisiting sites and services projects in Mumbai and Chennai 20 years later. World Bank. Retrieved December 15, 2016, from http://www.pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/371181489181586833/Sitesandservices-DRAFT-for-discussion-15Dec2016.pdf.

- Pancholi, V.S. (2020) Planned ambitions versus lived realities: an examination of the BSUP scheme in the periphery of Mumbai. PhD Thesis, University of Sheffield. Accessible online at: http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/27320/.

- Patel, K. (2016) Encountering the state through legal tenure security: Perspectives from a low income resettlement scheme in urban India, Land Use Policy, 58, pp. 102–113.

- Priya Uteng, T. & Lucas, K. (2018) The trajectories of urban mobilities in the Global South: an introduction. in: T. Priya Uteng & K. Lucas (Eds) Urban Mobilities in the Global South, pp. 1–19 (Abingdon: Routledge).

- Raman, B. (2016) Reading into the politics of land, review of urban affairs, Economic and Political Weekly, 51, pp. 76–84.

- Shatkin, G. & Vidyarthi, S. (2013) Introduction: Contesting the Indian City, in: G. Shatkin (Ed) 2013: Contesting the Indian City: Global Visions and the Politics of the Local. Studies in Urban and Social Change Series, 1–38 (Oxford: Wiley‐Blackwell).

- Srinivasan, S. & Rogers, P. (2005) Travel behaviour of low-income residents: studying two contrasting locations in the City of Chennai, India, Journal of Transport Geography, 13, pp. 265–274.

- Straughan, E., Bissell, D. & Gorman-Murray, A. (2020) The politics of stuckness: Waiting lives in mobile worlds”, Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 38, pp. 636–655.

- Todes, A. (2003) Housing, integrated urban development and the compact city debate. in: U. Pillay, R. Tomlinson, & J. Du Toit (Eds) Democracy and Delivery. Urban Policy in South Africa (Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council Press).

- Turok, I. (2013) Transforming South Africa’s divided cities: can devolution help?International Planning Studies, 18, pp. 168–187.

- Venkat, T. & Subadevan, M. (2015) Implementation of JNNURM-BSUP: A case study of the housing sector in Chennai, Report for the project: Impact of infrastructure and governance transformations on small, medium and big cities in India. Centre for Urban Policy and Governance, School of Habitat Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences.

- Venter, C., Vokolkova, V. & Michalek, J. (2007) Gender, residential location, and household travel: empirical findings from low-income urban settlements in Durban, South Africa. Transport Review, 27, pp. 653–677.

- Vijayabaskar, M. & Varadarajan, R. (2018) The mirage of inclusive growth? Metropolitan expansion and emerging livelihoods in the new urban periphery, in: A. Bhide & H. Burte (Eds) Urban parallax: Policy and the city in contemporary India, pp. 92–103 (New Delhi: Yoda Press).

- Wang, Z. (2020) Beyond displacement – exploring the variegated social impacts of urban redevelopment, Urban Geography, 41, pp. 703–712.

- Wray, C., Everatt, D., Götz, G., Ballard, R., Culwick, C. & Katumba, S. (2015) ‘The location of planned mega housing projects in context’. Gauteng City-Region Observatory Map of the Month. May 1. https://www.gcro.ac.za/outputs/map-of-the-month/