Abstract

Specialist housing for older people is an important welfare service and integral part of the housing offer in many countries. An extensive evidence base details the relative merits of different modes of provision, but little light has been cast on the forces shaping provision and the interests served. Drawing on a new model of demand and supply of specialist provision in England at the local authority level, this study addresses this lacuna. Two key contributions are made to knowledge and understanding. First, the uneven landscape of specialist housing provision is charted and the extent to which this maps onto need is revealed. Second, this condition is explained by situating specialist housing within wider debates about the reimagining of housing systems driven by the neoliberal transformation of housing politics, and recognising that these processes can have uneven effects embedded in the nature of places.

Introduction

Specialist housing is an integral part of the housing offer for older people in many countries. There is a strong preference amongst older people for ‘staying put’ and ageing in place in their current home (Robinson et al., Citation2020), but a move to specialist housing can sometimes represent the most effective means of accommodating the ongoing adjustments people need to make between themselves and their environment as they age (Means, Citation2007). Specialist housing developments are distinct from residential care or nursing homes in that they provide individual dwellings with their own front door. Specialist housing is available to rent and own. Access is restricted to older people and the physical design and layout is intended to influence healthy ageing, minimise exposure to risks and make it easier to perform daily activities. Communal areas and onsite amenities including restaurants and shops are sometimes provided. There is typically some form of housing management and support service such as a manager or warden, and varying levels of care and support can be available.

An extensive evidence base has accumulated detailing the design, development and consumption of specialist housing for older people. Questions have been raised about the extent to which some forms of provision serve the age-friendly agenda, integrate older people into the wider neighbourhood, enable intergenerational interactions, and promote independence (Evans, Citation2009; Hrybyk et al., Citation2012; Liddle et al., Citation2014). However, the consensus to emerge is that decent, affordable, appropriately designed specialist housing that enables the delivery of flexible care and support can improve quality of life, have a positive impact on health and well-being, allow people to live independently in a home of their own for longer, and provide savings for health and social care budgets (Croucher et al., Citation2006; Riedy et al., Citation2017; Roy et al., Citation2018).

Specialist housing is an important welfare service and an integral component of the continuum of care in later life (Harding et al., Citation2018). It is therefore surprising that relatively little attention has been paid to the question of ‘who gets what specialist housing, where and why’? Little is known about the geography of provision and the extent to which this maps onto need at various scales. Likewise, little is known about the forces shaping provision and the particular interests served. These gaps in knowledge reflect the origins of much of the extant literature within the traditions of environmental gerontology and the resultant focus on the extent to which different forms of provision serve to optimise the relationship between older people and their living environment. Valuable insights have been provided, but analysis has largely failed to situate specialist housing provision within the political economy of housing. Meanwhile, analysis rooted within the traditions of housing and urban studies exploring the process of disruption and change associated with the neoliberal transformation of housing systems across the world has largely neglected specialist housing for older people as a focus of study, focusing instead on more visible urban margins.

This paper addresses these lacunae through a focus on specialist housing for older people in England, where seven per cent of older people (aged 55 years and over) are estimated to live in specialist housing (Pannell et al., Citation2012). Drawing on a new model of demand and supply at the local authority level to support original analysis, it makes two particular contributions to knowledge. First, it charts the contours of the uneven landscape of specialist housing provision for older people and chronicles the extent to which provision maps onto need. The degree of national coherence and extent to which provision is embedded within the nature of places is explored and the possibility that access might be more about whereabouts than need is considered. Second, it explains this variable geography by situating analysis of specialist housing within wider debates about the reimagining of housing systems driven by the neoliberal transformation in housing politics. This involves recognising and understanding uneven effects emerging in different places as the consequence of the interplay between macro processes of transformation and the particulars of local context. In doing so, this study responds to calls for analysis focusing on ‘actually existing neoliberalisations’ (Brenner and Theodore, Citation2002) in order to provide more nuanced accounts of the local variegations associated with the neoliberal reimagining of housing (Rolnik, Citation2019).

Discussion begins by outlining the conceptual framework supporting this endeavour, drawing upon Massey’s (Citation1984) geological metaphor to conceptualise how geographical variations within housing systems are co-constituted by the nature of places and the political economy of housing. Recognising the importance of history to this framing, successive phases of investment and development of specialist housing in England are then reviewed and situated within wider debates about macro process of transformation in the housing system. The methods employed in the study are then profiled, including data sources and analytical techniques. The presentation of findings is organised around three key research questions. A discussion section contextualises these findings, before a concluding section reflects upon study’s contribution to knowledge.

Conceptual framing

This study’s interest in the geography of provision of specialist housing aligns with the traditional concern of welfare geography in spatial malfunctionings and injustices within society (Smith, Citation1977). Geographical accounts of welfare have been criticised for failing to move beyond description to explain the origins of observed variations, question political and policy rationales and consider their implications (Milbourne, Citation2010). This study responds by venturing beyond description to analyse the multiple intersections and complex interactions between the state, market and third sectors that inform the provision of specialist housing for older people. To this end, the study is cognisant of two important features of this mixed economy.

First, a mixed economy of specialist housing is nothing new; there has always been a mixed economy of provision in England, involving the state, market and charitable sectors. However, the structure of provision has varied historically, as the form, nature and role played by different sectors has fluctuated through time. Second, the provision of specialist housing - as with all welfare services – is structured in and through local places and results in particular local configurations. As Charlesworth et al., (Citation1995) observe, welfare provision is ‘resolutely local’, reflecting existing patterns of provision and the presence and actions of different types of providers. The result is the existence of (plural) mixed economies rather than one (singular) mixed economy.

In considering this pluralism, it is helpful to revisit Massey’s (Citation1984) geological metaphor regarding layers of accumulation associated with different rounds or periods of investment and related activity. Paraphrasing Massey (Citation1984; 117-118), a local mixed economy of specialist housing can be understood as an historical product of a combination of layers of investment and activity in fields including housing, health and social care that have been laid down over a number of years. These sedimented layers are not just material in form (bricks and mortar), but are composed of economic, political, cultural and ideological strata. Different sectors, agencies, cultures and ways of working emerge and rise to dominance at different points in time, and then, perhaps, retreat to a more residual role or disappear completely. As one phase of activity is proceeded by another, so the structure of the mixed economy of provision can be seen to be the product of a combination of layers involving the successive imposition over the years of new rounds of policy, associated investment, forms of activity and provision.

At this point, Massey inserts an important point of clarification into her exploration of spatial structures of production, which is critical to our attempts to comprehend the variable geography of specialist housing. Localities are not mere passive recipients of processes of change handed down from some higher national or global level, for example, in the form of national policies or market dynamics. A variety of conditions inevitably arise at the local level and these variations affect the outcomes associated with wider processes of change.

This study draws on Massey’s geological metaphor and its attention to the interplay between macro-social processes, the nature of places and local responses to help understand the mixed economy of specialist housing for older people. The ongoing neoliberal transformation of the housing system and associated processes of privatisation, deregulation and reduced state spending are recognised as key to understanding disruption and change in the provision of specialist housing. However, it is acknowledged that these general processes can play out in different ways in different places; that there is a form of mutual determination between the combination of layers of investment and activity that have accumulated through time, local readings of and responses to the need for readjustments in provision, and the local outcomes associated with contemporary processes of disruption and change. This transformation has an overarching logic, but rather than taking a singular form as a regime of policy, regulation and practice, it has uneven effects that are embedded in the nature of places (Brenner and Theodore, Citation2002).

The history of specialist housing for older people

The history of specialist housing in England can be divided into three broad phases. First, from the medieval period through to the twentieth century local charities and private philanthropy were the primary providers of specialist housing for older people in England. Second, in the aftermath of the second world war the state emerged as the principal provider of welfare services, including specialist housing. Third, more recently the role of the state has diminished and the private and charitable sectors have emerged as preferred providers of new specialist housing. This section briefly reviews this history, drawing on available evidence to sketch out what is currently known about the geography of provision.

Specialist housing for older people has a long history in England, stretching back to the medieval period, when almshouse charities first emerged providing free accommodation for local older people who had fallen into poverty as a result of age or ill health (McIntosh, Citation2012). Almshouses were founded by wealthy individuals and their location reflected geographies of private wealth rather than any notion of need (Bryson et al., Citation2002). Higher levels of provision were therefore in the south and south-east (Goose, Citation2014). Public provision during this period was limited to poor houses, which provided shared accommodation for the poor and elderly. Spatial unevenness continued to be a characteristic of local systems of welfare provision into the twentieth century, reflecting variations in the accumulation of wealth, forms of patronage and pressure exerted by different groups in particular places (Milbourne, Citation2010).

The specialist housing sector remained small scale and piecemeal until the second half of the twentieth century when a major state sponsored housing assistance programme was established as part of efforts to deliver a more comprehensive welfare state. Local authorities took the lead in developing new housing and the relatively large public housing sector that emerged incorporated the provision of specialist housing for older people. Central government actively promoted the development of specialist provision by local authorities during the 1970s and 80s in response to the indifference of the private sector to the needs of older people (Barnard, Citation1982). Local authorities also increasingly recognised the potential to ‘free up’ general needs housing, which was an increasingly scarce commodity as a result of cuts to new build programmes and the loss of stock through the right to buy programme, by supporting older people to move into specialist housing (Malpass and Murie, Citation1990). Specialist provision typically took the form of sheltered housing; self-contained accommodation with its own front door in a development where other residents are older people and practical assistance is provided via an on-site warden, floating support or an on-call service. During this period, a number of housing associations formed with the specific purpose of providing housing for older people and started developing sheltered housing. It is estimated that 400,000 older people were living in specialist housing by 1981 (Butler et al., Citation1983).

A key objective of the ‘one nation’ political consensus that emerged after the Second World War was to alleviate uneven geographical development and promote greater national coherence in welfare provision (Omstedt, Citation2016). However, responsibility for the development of specialist housing was devolved to local authorities and the lack of specific guidelines left local councils free to build as much or as little as they saw fit. Consequently, development was rather haphazard, reflecting the particular interests, motivations and understandings of need amongst local housing officers and politicians, as well as available resources. Butler et al., (Citation1983) report variations in supply at the local authority level ranging from 1 unit of specialist housing per 1,000 people aged 65 years or older, through to 278 units per 1,000. No relationship was evident between the level of provision and measures of need, including the size of the older person population or the availability of alternative accommodation, such as residential care. Local authorities with a relatively large public housing stock tended to have a larger sheltered housing sector, suggesting a local political commitment to state intervention in housing was an important factor informing the size of the specialist housing sector at the local level. Metropolitan districts and London Boroughs were also reported to benefit from corporate commitment and capacity (Barnard, Citation1982).

The period since the 1980s has witnessed change and disruption in the provision of specialist housing consistent with the ongoing transformation of housing systems observed in urban contexts across the globe, driven by deregulation, privatisation and reduced state spending (Rolnik, Citation2019). Housing associations emerged as the largest providers of specialist housing. Key to this shift was the emergence of a new financial regime for social housing in 1988, founded on the redesignation of housing associations as non-public bodies. This afforded housing associations the opportunity to source private finance and to, thereby, serve as the channel through which private investment could flow into the social housing sector, supporting the political objective of reducing state spending on the provision, maintenance and repair of housing. Consequently, housing associations became government’s preferred developer of new social housing and a major programme of large-scale transfer of council stock into the housing association sector was pursued motivated by the scope for accessing private finance to redress repair and improvement backlogs (Pawson and Fancy, Citation2003).

Two notable trends in specialist provision by social landlords were associated with this new regime. First, there was a reduction in the provision of sheltered housing linked to the decommissioning of some older schemes and the redesignation of others as age-exclusive housing; housing exclusively for older people which is more suitable to their needs by virtue of location, type, design or adaptations, but where no specific support is available (Robinson et al., Citation2020). Redesignation was often pursued in response to pressures on revenue funding that prompted the removal of warden services from many sheltered schemes (Croucher, Citation2008). Decommissioning reflected difficulties funding the repair and maintenance of older schemes where problems were apparent with the quality and condition of accommodation (Wood, Citation2014). The geography of this retreat in provision is unclear.

A second notable change was a reduction in the scale and shift in the form and focus of new developments. Traditional forms of provision were increasingly criticised for offering standardised, ‘pre-packaged’ options that failed to provide choice and flexibility and promote autonomy and independence in older age, resulting in some people moving prematurely into residential care settings. Attention increasingly turned to the development of extra care housing, which was championed as providing improved housing quality, promoting independence and delivering savings for health and social care (Mullins, Citation2015). Extra care housing can be provided in a range of building types and different tenures and is characterised by independent living in a home of your own within a scheme or development where services are on hand if required, and might include care, support, domestic help, and social and community services.

Declining state commitment to and investment in the housing welfare system for older people served to limit the number of new extra care units developed by social landlords. A central government cap on local authority borrowing to fund house building resulted in a decline in the development of all forms of new housing by local authorities to 1,500 per year (Perry, Citation2014). Meanwhile, the ongoing shift away from government capital grant funding to revenue-based funding and private borrowing limited the ability of housing associations to serve as a major source of new specialist housing for older people (Harding et al., Citation2018). The result is a relatively modest total of an estimated 47,000 extra care units for rent in England (Riseborough et al., Citation2015).

In the context of cut-backs in new build and improvement programmes at a time of rising demand, social landlords increasingly focused on housing the most vulnerable older people. Choice became more limited for the majority of older people who are owner occupiers. Into this gap stepped the private sector, providing purpose built specialist housing that recognised the demands as well as the needs of older people (Butler et al., Citation1983). Specialist divisions of major housebuilders and companies focusing exclusively on the retirement market emerged as major developers of new provision in the 1980s (Bernard et al., Citation2007). Originally, these developments resembled sheltered housing, but there was soon a shift toward larger units and higher specifications, and the emergence of luxury and leisure-related developments (Williams, Citation1990). These purpose-built retirement communities combined an emphasis on leisure and lifestyle common in North American retirement communities, with a focus on participation, involvement and activity as a means of promoting well-being and independence common within retirement developments in Europe (Bernard et al., Citation2007).

Evidence suggests that older people moving into retirement housing are rewarded with a higher quality of life, more positive outcomes in relation to health and well-being, enhanced social networks and reduced living costs (Wood, Citation2014). However, many people are unable to access these benefits. It is estimated that between 40 and 50% of owner occupiers over 65 years of age cannot afford to buy a purpose built retirement property in their area (DEMOS and APPG, Citation2013). This is indicative of the tendency amongst private developments to target relatively affluent, independent older people with lower levels of physical and health needs, and to market schemes as promoting positive or active ageing (Harding et al., Citation2018).

The retreat of state involvement in the provision of specialist housing and the increasing role of the private sector over recent years has coincided with a notable reduction in the development of specialist housing for older people, from 30,000 new units per annum in the 1980s to an average of 7,000 units per annum in recent years (Lyons et al., Citation2016). This is at a time when demand outstrips supply and is likely to increase as a result of population ageing (International Longevity Centre, Citation2016). In response, it might be anticipated that new forms of state practice would emerge centred upon advancing the role of the market, particularly in places where ‘leaving it to the market’ is resulting in the undersupply of specialist provision (Robinson et al., Citation2020). However, no transformation has been pursued in the modest output of new specialist housing for older people delivered by the market; government interventions to encourage the market to provide new housing have focused on addressing the difficulties younger households encounter accessing owner-occupation (Best and Porteus, Citation2016).

Methods

Analysis was framed and focused via attention to three key questions.

What is the profile (form, nature and scale) of specialist housing for older people in England?

To answer this question analysis drew upon on data from the most comprehensive geographically defined database detailing specialist housing provision of different forms and tenures across England. Hosted by the Elderly Accommodation Counsel (EAC), this publically accessible database contains information on some 25,000 developments providing housing opportunities for older people and is updated regularly via questionnaire returns. The classification employed within the database distinguishes between three forms of specialist housing for older people:

sheltered housing, providing self-contained accommodation, with some shared facilities and supportive management, which might be on-site or involve regular visits

enhanced sheltered housing, where additional support and assistance is often provided on a 24 hour basis along with at least one meal per day

extra care housing, where a service registered to provide personal or nursing care is available on site 24 hours a day.

Other data fields include number of units, tenure and local authority area.

What is the relationship between the demand and supply of specialist housing for older people and to what extent does this vary across England?

Answering this question involved estimating the recommended supply or demand for specialist housing for older people. This was generated through the application of the Housing for Older People Supply Recommendations (HOPSR) model (CRESR, 2017). The HOPSR model generates an indication of the recommended supply – referred to here as demand – for specialist housing at the local authority level. The HOPSR model was preferred to other models for two key reasons. First, the demand estimates generated are sensitive to variations in local measures of need, including the demographics and housing situations of the local population of older people, the incidence of health problems and disabilities, access to home-based support services and the urban-rural nature of the area. Second, the model responds to criticisms of other models by generating demand estimates that are grounded within the bounds of the possible within the English context. This is achieved by basing estimates on prevalence rates for different forms of provision within the 100 local authorities with the highest level of supply per 1,000 older people aged 75 years and older. The application of the model resulted in the generation of demand estimates for three key forms of specialist housing: sheltered, enhanced sheltered and extra care housing. Geographic information systems (GIS) were used to present the distribution of relative supply – or demand - across England using thematic maps. One limitation with the application of the model that should be noted is that available data did not allow the generation of reliable demand estimates for different tenures.

What factors help to explain observed geographical variations in the supply and demand of specialist housing for older people?

A statistical model was developed using Generalised Linear Modelling (GLM) to identify factors that help explain some of the variation in relative supply at a local authority level; the difference between recommended and actual level of provision per 10,000 older people. The analysis employed a stepwise procedure. The variables considered related to factors referenced in the extant literature as potential influences upon the demand and supply of specialist housing for older people at the local level: regional location; urban or rural location; change in supply of specialist provision by housing associations; deprivation according to the indices of multiple deprivation (IMD); median house price in the area; limiting long term illness amongst people aged 75 years and over; the proportion of the population receiving day home care; home-ownership amongst people aged 75 years or older; the population aged 85 years or over; and dementia amongst people 75 years or older.

Finally, a review of the ranking of local authorities based upon the size of the deficit or surplus in provision revealed some apparent anomalies, given what modelling had revealed about factors associated with variations in relative provision. In response, cluster analysis was used to explore the characteristics of the 20 per cent of local authorities with the largest deficits and surpluses. Cluster analysis is a multivariate method, which was used here to classify local authorities based on a set of measured variables. The outcome was a series of groupings of ‘similar’ local authorities. The analysis used the TwoStep Cluster Analysis procedure in SPSS, which enables handling of categorical and continuous variables as well as the automatic selection of number of clusters. The similarity between two clusters was determined using a Log likelihood measure.

Findings

What is the profile (form, nature and scale) of specialist housing for older people in England?

The EAC database identifies 519,000 units of specialist housing for older people in 2017 (). The sector therefore accounts for just over two per cent of the 24.4 million dwellings in England (MHCLG, 2020). Almost three-quarters (73%) of these properties are available to rent from a social landlord and one-quarter (25%) are owner-occupied. The EAC database does not distinguish between different types of social landlord, but it has been estimated that 70 per cent of social rented provision is provided by housing associations (Riseborough et al., Citation2015). Shared ownership and private renting together account for less than two per cent of provision.

Table 1. Form of provision and tenure of specialist housing in England.

Sheltered housing is the dominant form of provision, accounting for 87% of all dwellings (). Sheltered housing provided by social landlords accounts for almost two-thirds (63%) of all specialist housing. Little more than 10 per cent of specialist provision is housing with care, typically in the form of extra care housing. The vast majority of housing with care is provided by social landlords, although there is some evidence of the reported emergence of an ‘assisted living’ market for self-funded older people (Mullins, Citation2015). In addition to specialist housing, there are a further 116,800 units of age-exclusive housing for older people, the vast majority (85%) of which are available to rent from a social landlord. This sector has grown in recent years as a result of the decommissioning of specialist housing in response to pressures on revenue and capital spending (Croucher, Citation2008; Wood, Citation2014).

What is the relationship between the demand and supply of specialist housing for older people and to what extent does this vary across England?

Comparing EAC data on supply with the measure of recommended provision or demand generated via the HOPSR model reveals a shortfall of 258,000 units of specialist housing in England (). A shortfall is apparent across all forms of specialist housing. The largest shortfall is in sheltered housing; 240,424 units, which is equivalent to one-third of total estimated demand.

Table 2. Supply and demand for different forms of specialist housing for older people.

A clear correlation is evident at the regional level between deprivation, need and provision (). This takes the form of an inverse relationship, with larger average shortfalls in supply recorded in more deprived regions in the North and Midlands with relatively high proportions of older people with long-term limiting illness or disability and low healthy life expectancy. These regions are more reliant on the social rented sector for specialist housing than regions in the South of England.

Table 3. Supply and demand by region.

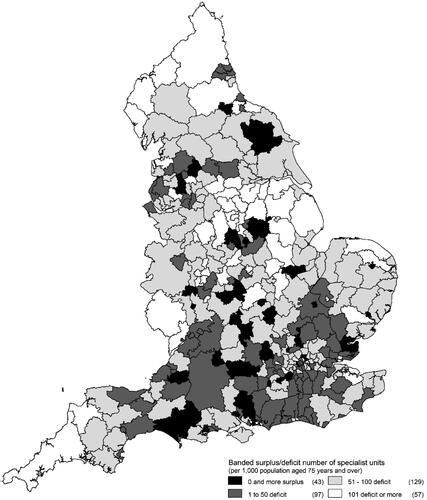

A shortfall in provision was recorded in 285 out of 326 (87%) local authority areas in England. The difference between supply and demand ranged from a deficit of 176 units (per 1000 people aged 75 years or older) in Ashfield, through to a surplus of 104 units in Northampton. maps these variations across England. A number of patterns can be observed. First, there is an outer ring of local authorities around London with either a surplus or small deficit in the supply of specialist older people housing. Second, there is a concentration of areas with larger deficits in supply in the North of England, including the M62 corridor, South Yorkshire and parts of the North East. In London only three boroughs have a surplus and 20 out of 32 have a shortfall of more than 50 units per 1,000 population aged 75 years.

What factors help to explain observed geographical variations in the supply and demand of specialist housing for older people?

Regression modelling revealed a statistically significant relationship between five contextual factors and local provision of specialist housing. The strongest relationship was a positive association between overall provision and the number of social rented specialist housing units. On average, local authority areas with larger numbers of social rented specialist units had smaller deficits or a surplus in provision. This finding underlines the continued importance of historical investment decisions and development activities pursued by local authorities and housing associations, supported by central government from the 1970s through to the 1990s. Another aspect of the local housing system revealed as statistically significant was the proportion of older people living in owner occupied housing. Local authority areas with higher levels of owner occupation reported larger deficits in the provision of specialist housing. One possible explanation is that higher levels of owner occupation are consistent with a more limited local history of state-sponsored intervention in the housing system, which is as an important predictor of specialist housing provision (Butler et al., Citation1983).

A statistically significant relationship was observed between one particular measure of need and provision of specialist housing. This was an inverse relationship: on average, areas with higher levels of older people with long-term limiting illness, who might benefit from a move into specialist housing, had larger deficits in provision. This is a notable finding that underlines the disconnect between need and provision. Two locational factors were revealed to have a statistically significant relationship with the provision of specialist housing. First, rural local authority areas were found to on average have a larger deficit in provision compared to urban areas. This finding is consistent with the known challenges of meeting the needs of more dispersed populations for a form of provision that is typically developed on a scheme basis and in clusters of multiple dwellings. Rural areas also have a more limited history of local state involvement in the housing system and lower levels of social rented provision (Milbourne, Citation1998). Second, a statistically significant relationship was observed between regional location and provision. On average, local authority areas in the South East, South West and Eastern regions of England had a smaller deficit (or a surplus) in supply. This might reflect lower levels of need combined with relatively high levels of private sector provision in these regions in recent years (see ).

Evidence of a functional relationship between the provision of specialist housing and various contextual factors provides important insights into potential cause and effect relationships informing variations in supply and demand. However, the situation in any given location is the result of the interaction of a particular combination of multiple contextual factors. Variations in the combination of factors underpinning the variable geography revealed in were explored through cluster analysis.

Three clusters were identified within the 20 per cent of local authorities with the largest deficit or shortfall in provision of specialist housing (). Levels of need varied between clusters, but common to all was the fact that supply was unresponsive to local needs, resulting in large shortfalls. The relatively large shortfall in areas within cluster 1 appears to reflect the relatively low level supply of, specifically social rented, specialist housing, rather than high absolute numbers of people in need. These areas might be described as lower demand and low supply. In contrast, areas in cluster 3 might be described as high demand and lower supply. These areas have high levels of need, as reflected in the proportion of people with long term limiting health problems, but the supply of social rented provision is relatively low compared to the national average, despite being higher than in clusters 1 and 2. Local authorities in this cluster have some of the largest deficits in provision. Finally, cluster 2 falls between the other two clusters, with areas exhibiting relatively high levels of need, as evidenced by the percentage of people with long term limiting illness, and levels of supply that are higher than in the other two clusters but relatively low compared to the national average.

Table 4. Characteristics of cluster groups with largest deficits in specialist provision.

Three clusters were apparent amongst the 20 per cent of local authorities (66) with the smallest deficits or a surplus in provision of specialist housing (). Levels of need varied across the three clusters, but supply was relatively responsive to local need, resulting in a small shortfall or even a surplus in provision. The 12 local authority areas in cluster 1 evidenced high levels of long term limiting illness and social care needs, but these needs were being met by virtue of a history of local state intervention (evidenced by relatively high levels of social rented provision), recent growth in housing association provision, and an emergent extra care sector. Areas in cluster 1 might be described as high demand and high supply. In contrast, the 26 areas in cluster 3 had low levels of social rented provision, but also relatively low levels of health and social care needs, as well as relatively high levels of private sector provision. Areas in cluster 3 might be described as low demand and low supply.

Table 5. Characteristics of cluster groups with lowest shortfall or a surplus in specialist provision.

Discussion

The result of the accumulated layers of investment associated with the history of the mixed economy of specialist housing in England is the provision of 519,000 specialist housing units for older people. The profile of this stock base reflects the enduring significance of the large-scale state sponsored specialist housing development programme pursued in the 1970s and 80s, a period that witnessed development on a scale eclipsing all previous and subsequent rounds of investment and provision. Sheltered housing was the prevailing form of specialist housing during this era and remains the predominant form of provision in England today, despite more recent forms being lauded for more effectively serving the age-friendly agenda (Mullins, Citation2015). Local authorities were the principal developers and managers of specialist housing during this period and social renting still accounts for almost three-quarters of specialist housing, in a reversal of the tenure profile of older people in general needs housing (Pannell et al., Citation2012).

The enduring significance of the social rented sector also reflects the fact that, unlike general needs council housing, specialist housing has not been subject to privatisation through the right to buy programme. In an interesting nuancing of what has been identified as one of the most iconic and significant applications of neoliberal policy worldwide (Hodkinson et al., Citation2013), the Housing Act 1985 granted local authorities the right to refuse to let tenants exercise the right to buy on the grounds that a property is particularly suitable for occupation by an older person. Some schemes were subsequently transferred to housing associations, but stock remained within the social rented sector and continued to provide the least expensive and most secure specialist housing available.

Analysis revealed a notable shortfall of 258,000 units in the supply of specialist housing for older people in England. All nine regions and most local authority areas recorded a shortfall in supply. This is not surprising. At a time of population ageing, there has been a reduction in the supply of new specialist housing. Cuts to public funding have limited the supply of new social units by housing associations, while the private sector has tended to focus on particular market segments – typically, lifestyle and leisure orientated provision targeted at more affluent, independent older people - rather than building at volume to meet wider needs. Meanwhile, stock has been lost via the decommissioning and redesignation of older social rented stock in response to cuts in capital and revenue funding.

There is a variable geography to this shortfall in supply. Analysis revealed a statistically significant relationship between regional location and shortfall in supply, with the largest shortfalls in the former industrial heartlands of the North of England, which have higher levels of deprivation, poor health and disability amongst older people and lower healthy life expectancy (Marmot, Citation2020). A statistically significant relationship was also revealed between larger deficits in provision of specialist housing and higher levels of older people with long-term limiting illness. Access to a welfare service recognised as having a positive impact on health and well-being and promoting independent living in older age appears to be more a matter of whereabouts than need.

This patterning of provision is an historical product of successive periods of policy, investment and development, which the Audit Commission (1998) has previously recognised as being resolutely local and bearing no discernible relationship to patterns of demand. In the 1970s and 80s, local authorities led the development of specialist housing and were left to build as much or little as they saw fit. The result was a variable geography of provision, with more active local programmes of development being observed in areas with an established record of council house building, often in towns and cities in the North and Midlands of England with a long history of local political commitment to social housing. Time has weathered this layer of provision, through the decommissioning and redesignation of some older schemes, although this ageing stock remains the cornerstone of the local offer in many places.

Subsequent phases of development have followed a different pattern. In particular, a distinct geography is associated with the activities of private companies that emerged during the 1990s as leading developers of specialist provision. Private developers tend to prefer more affluent locations. This reflects the fact that although land costs are lower in more deprived locations, the higher building costs associated with the specialist sector push prices beyond the reach of many local home owners, rendering new developments sub-optimal and prompting private developers to focus on higher value markets where greater numbers of older home owners have the required levels of housing equity (Archer et al., Citation2018). The result is an uneven geography of private provision that reflects the historical accumulation of housing wealth rather than any particular measure of need. For example, 11% (2,790) of specialist housing in the North East is owner occupied, compared to 40% (39,483) in the South East, a region home to some of the highest average house prices in England (Hamnett and Reades, Citation2019). This patterning mirrors phases of specialist housing development, pre-welfare state, when the government played a minimal role and local charities and private philanthropy were key providers and the geography of provision paralleled geographies of private wealth rather than need (Bryson et al., Citation2002).

The sedimented layers of provision and subsequent effects of weathering vary between places. The interaction of this variable geography of provision with local variations in need results in a complex picture. Various factors are significant in helping to explain broad patterns within this complexity, including aspects of the local housing system, the prevalence of health problems amongst the older population and various locational factors. However, cluster analysis revealed a high degree of local specificity in the interaction between the history of specialist provision and the contemporary profile of need informing a shortfall in supply.

Recognising these distinctive local trajectories, and the particularities of place that inform them, adds depth and nuance to understanding of the particulars of the crisis in specialist housing. Previous studies have pointed to the gap between the presumed efficiency of the marketised system, in which older people operate as informed welfare consumers navigating a range of local housing options, and the reality of a market unresponsive to need and characterised by scarcity (Harding et al., Citation2020). This study has revealed the geography of this scarcity. Any attempt to address this shortfall will need to be nuanced to these local particulars of supply and demand. However, precisely at the moment when there is a need for a coherent, long-term strategy to meet the needs and promote the well-being of an ageing population, the supply of specialist housing is increasingly subject to the vagaries of the market. The result is that the geography of development increasingly reflects the commercial imperatives of private developers and viability assessments of housing associations rather than the variable geography of need.

Conclusion

Most older people will continue to live independently in their current home, but sometimes ageing-well can become incompatible with ageing-in-place and a move to specialist housing might be required. This study has revealed a national shortfall in specialist housing provision in England. A variable local geography is associated with this shortfall and access to this important welfare service is more about whereabouts than need. This situation is likely to be deteriorate further without state intervention to support regeneration of ageing social rented provision upon which many areas rely, stimulate the development of new social rented provision and generate private sector interest in developing at scale across a wider geography. Yet, despite calls to ensure the housing needs of older people are better addressed in the context of population ageing (Select Committee on Public Services and Demographic Change, Citation2013), the state resolutely refuses to intervene to drive a transformation in the provision of this key welfare service. This apparent indifference reflects adherence to a central tenet of neoliberal governance; faith in the market model for effective decision-making and efficient delivery (Ives, Citation2015). This study suggests that such faith is misplaced, certainly if the aspiration is to meet need.

In seeking to understand and explain the specifics of provision and its variable geography, this study has situated analysis of specialist housing within the overarching logics of the ongoing neoliberal transformation of housing. Focusing on the ‘actually existing neoliberalism’ (Brenner and Theodore, Citation2002) of specialist housing, provision has been revealed as a geohistorial outcome embedded in the nature of places. Drawing on Massey (Citation1984), the lack of national coherence in provision is understood to be the product of the ongoing interaction between contemporary process of disruption and change and accumulated layers of national and local policy and practice, institutional frameworks, regulatory performances, political struggles and associated patterns of investment and provision. Previous studies have emphasised the importance of recognising national particularity in neoliberal transformations of housing (Beswick et al., Citation2019). This study has revealed local particularity to also be an important dimension of what Springer (Citation2010, p. 1025) refers to as “neoliberalism’s hybridized and mutated forms as it travels around our world”.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Ryan Powell and the anonymous referees for comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

David Robinson

David Robinson is Professor of Housing and Urban Studies in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning, University of Sheffield.

Ian Wilson

Ian Wilson is a Principal Research Fellow in the Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research at the Sheffield Hallam University.

References

- Archer, T., Green, S., Leather, D., McCarthy, L., Wilson, I., Robinson, D. & Tait, M. (2018) Older People’s Housing, Care and Support Needs in Greater Cambridge 2017–2036 (Sheffield: CRESR, Sheffield Hallam University).

- Audit Commission. (1998) Home Alone: The Role of Housing in Community Care (London: Audit Commission).

- Barnard, K. (1982) Retirement housing in the United Kingdom: a geographical appraisal, in: A. M. Warnes (Ed) Geographical Perspectives on the Elderly, pp. 161–190 (Chichester: John Wiley and Sons).

- Bernard, M., Bartlam, B., Sim, J. & Biggs, S. (2007) Housing and care for older people: Life in an english purpose built retirement village, Ageing and Society, 27, pp. 555–578.

- Best, R. & Porteus, J. (2016) Housing Our Ageing Population: Positive Ideas. HAPPI 3. All Party Parliamentary Group on Housing and Care for Older People.

- Beswick, J., Imilan, W. & Olivera, P. (2019) Access to housing in the neoliberal era: A new comparativist analysis of the neoliberalisation of access to housing in Santiago and London, International Journal of Housing Policy, 19, pp. 288–310.

- Brenner, N. & Theodore, N. (2002) Cities and the geographies of “actually existing neoliberalism”, Antipode, 34, pp. 349–379.

- Bryson, J. R., McGuiness, M. & Ford, R. G. (2002) Chasing a ‘loose and baggy monster’: Almshouses and the geography of charity, Area, 34, pp. 48–58.

- Butler, A., Oldman, C. & Greve, J. (1983) Sheltered Housing for the Elderly: Policy Practice and the Consumer (London: Allen & Unwin).

- Charlesworth, J., Clarke, J. & Cochrane, A. (1995) Managing local mixed economies of care, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 27, pp. 1419–1435.

- CRESR (2017) The Housing for Older People Supply Recommendations (HOPSR) https://www4.shu.ac.uk/research/cresr/ourexpertise/older-peoples-housing-care-support-needs-greater-cambridge

- Croucher, K. (2008) Housing Choices and Aspirations of Older People: Research from the New Horizons Programme (London: Department for Communities and Local Government).

- Croucher, K., Hicks, L. & Jackson, K. (2006) Housing with Care for Later Life: A Literature Review (York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation).

- DEMOS and APPG (2013) The affordability of retirement housing an inquiry by the all party parliamentary group on housing and care for older people. https://www.demos.co.uk/files/Demos_APPG_REPORT.pdf?1415895320

- Evans, S. (2009) Community and Ageing: Maintaining Quality of Life in Housing with Care Settings (Bristol: The Policy Press).

- Goose, N. (2014) Accommodating the elderly poor: Almshouses and the mixed economy of welfare in England in the second millennium, Scandinavian Economic History Review, 62, pp. 35–57.

- Hamnett, C. & Reades, J. (2019) Mind the gap: Implications of overseas investment for regional house price divergence in Britain, Housing Studies, 34, pp. 388–406.

- Harding, A., Parker, J., Hean, S. & Hemingway, A. (2018) Supply-side review of the UK specialist housing market and why it is failing older people, Housing, Care and Support, 21, pp. 41–50.

- Harding, A., Parker, J., Hean, S., Hemingway, A. (2020) ‘It can’t really be answered in an information pack…’: A realist evaluation of telephone housing options service for older people, Social Policy and Society, 19, pp. 361–378.

- Hodkinson, S., Watt, P. & Mooney, G. (2013) Introduction: Neoliberal housing policy – time for a critical re-appraisal, Critical Social Policy, 33, pp. 3–16.

- Hrybyk, R., Rubinstein, R. L., Eckert, J. K., Frankowski, A. C., Keimig, L., Nemec, M., Peeples, A. D., Roth, E. & Doyle, P. J. (2012) The dark side: Stigma in purpose-built senior environments, Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 26, pp. 275–289.

- International Longevity Centre (2016) The State of the Nation’s Housing (London: ILC).

- Ives, A. (2015) Neoliberalism and the concept of governance: renewing with an older liberal tradition to legitimate the power of capital, Cahiers de Mémoire(s), Identité(s), Marginalité(s) dans le Monde Occidental Contemporain 14. Available at https://mimmoc.revues.org/2263 (accessed 20 July 2021).

- Liddle, J., Scharf, T., Bartlam, B., Bernard, M. & Sim, J. (2014) Exploring the age-friendliness of purpose built retirement communities: Evidence from England, Ageing and Society, 34, pp. 1601–1629.

- Lyons, M., Green, C. & Hudson, N. (2016) How a greater focus on ‘last time buyers’ and meeting the housing needs of older people can help solve the housing crisis, in: B. Franklin, B. Cesira, & H. Dean (Eds) Towards a New Age: The Future of the UK Welfare State, pp. 131–140 (London: The International Longevity Centre).

- Malpass, P. & Murie, A. (1990) Housing Policy and Practice (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

- Marmot, M., Allen, J., Boyce, T., Goldblatt, P. & Morrison, J. (2020) Health Equity in England: the Marmot Review 10 Years On. Institute of Health Equity. https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/upload/publications/2020/Health%20Equity%20in%20England_The%20Marmot%20Review%2010%20Years%20On_full%20report.pdf

- Massey, D. (1984) Spatial Divisions of Labour. Social Structures and the Geography of Production (London: Macmillan).

- McIntosh, M.K. (2012) Poor Relief in England, 1350–1600. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Means, R. (2007) Safe as houses? Ageing in place and vulnerable older people in the UK, Social Policy & Administration, 41, pp. 65–85.

- MHCLG (2020) English Housing Survey 2019 to 2020: Headline Report. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-housing-survey-2019-to-2020-headline-report

- Milbourne, P. (1998) Local responses to central state restructuring of social housing provision in rural areas, Journal of Rural Studies, 14, pp. 167–184.

- Milbourne, P. (2010) The geographies of poverty and welfare, Geography Compass, 4, pp. 158–171.

- Mullins, D. (2015) Extra Care Housing. Impacts on Individual Well-Being. Evidence Review 1. (Birmingham: Housing and Communities Research Group, University of Birmingham).

- Omstedt, M. (2016) Reinforcing unevenness: Post-crisis geography and the spatial selectivity of the state, Regional Studies, Regional Science, 3, pp. 99–113.

- Pannell, J., Aldridge, H. & Kenway, P. (2012) Market Assessment of Housing Options for Older People (London: New Policy Institute).

- Pawson, H. & Fancy, C. (2003) Maturing Assets: The Evolution of Stock Transfer Housing Associations (Bristol: Policy Press).

- Perry, J. (2014) Where is Housing Heading? Why is It Important to Change Local Authority Borrowing Rules? (London: Chartered Institute of Housing).

- Riedy, C., Wynne, L., Daly, M. & McKenna, K. (2017) Cohousing for Seniors: Literature Review. Prepared for the NSW Department of Family and Community Service and the Office of Environment and Heritage, by the Institute for Sustainable Futures (Ultimo: University of Technology Sydney).

- Riseborough, M., Fletcher, P. & Gillie, D. (2015) Extra care housing: What is it? Housing LIN factsheet 1. https://www.housinglin.org.uk/_assets/Resources/Housing/Housing_advice/Extra_Care_Housing_What_is_it.pdf

- Robinson, D., Green, S. & Wilson, I. (2020) Housing options for older people in a reimagined housing system: A case study from England, International Journal of Housing Policy, 20, pp. 344–366.

- Rolnik, R. (2019) Urban Warfare. Housing under the Empire of Finance (London: Verso).

- Roy, N., Dubé, R., Després, C., Freitas, A. & Légaré, F. (2018) Choosing between staying at home or moving: A systematic review of factors influencing housing decisions among frail older adults, PLoS One, 13, pp. e0189266

- Select Committee on Public Services and Demographic Change (2013) Ready for Ageing? HL Paper 140th ed. (London: TSO).

- Smith, D. (1977) Human Geography: A Welfare Approach (London: Edward Arnold).

- Springer, S. (2010) Neoliberalism and geography: expansions, variegations, formations, Geography Compass, 4, pp. 1025–1038.

- Williams, G. (1990) The Experience of Housing in Retirement: Elderly Lifestyles and Private Initiative (Aldershot, Hampshire: Gower).

- Wood, C. (2014) The Affordability of Retirement Housing – An Inquiry by the All Party Parliamentary Group on Housing and Care for Older People (London: Demos).