Abstract

Given the growing threat of housing instability in the United States, this study explores the variability in housing instability experiences in terms of severity and persistence by tracking low-income households in the Panel Study of Income Dynamics data from 2003 to 2017. First, this study examines the associations between one housing instability incident at a particular time and subsequent mobility trajectories. Second, by incorporating sequence analysis, this study explores the conditions under which low-income households are likely to suffer from more chronic forms of housing instability. The results reveal that the more severe one housing instability incident is, the more prolonged the entire housing instability experience is likely to be over time. The ability to maintain homeownership, repeated transitions in partnerships, job insecurity, and repetitively moving across distressed neighborhoods are the conditions for housing instability that occurs more frequently. Moreover, younger households and households with a member with health problems are likely to suffer from more chronic forms of housing instability.

Along with the housing affordability crisis happening in major cities across the world (Florida & Schneider, Citation2018), achieving and maintaining housing stability becomes challenging for many low-income households in the United States, where approximately one in every four renters is severely cost burdened, spending more than half of their household income on housing costs (Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University [JCHS], 2020). The prevalence of high housing cost burdens implies that millions of households’ housing situations can be easily destabilized by minor financial shocks. One important by-product of the severe shortage of affordable housing is housing instability, often represented by frequent and involuntary residential moves. Although there is no universally accepted definition of housing instability (Cox et al., Citation2017), it usually refers to various residential situations where households do not have sufficient control over their residential environments (Beer, Citation2011). Housing instability is often represented by living in unaffordable, overcrowded, or doubled-up housing in combination with frequent residential relocations (Kleit et al., Citation2016).

Existing studies have well documented the detrimental impacts of housing instability on many dimensions of low-income households lives, such as children’s education (Ziol-Guest & Mckenna, Citation2014), employment (Desmond & Gershenson, Citation2016a), physical and mental health (Desmond & Kimbro, Citation2015), and social networks (Oishi, Citation2010). Given its negative impacts, scholars increasingly recognize that housing instability is not a simple consequence of poverty; instead, it can function as a significant cause of poverty (Desmond, Citation2016).

Based on this recognition, housing scholars have investigated low-income households residential moves as a symptom of housing instability, and they have strived to understand the mechanisms through which housing instability occurs and persists (Clark, Citation2010; Desmond & Gershenson, Citation2016a; Fargo et al., Citation2013; Kang, Citation2019; Phinney, Citation2013). Many quantitative and qualitative works have identified a wide range of household-level factors that can cause housing instability directly or indirectly, such as marriage dissolution, domestic conflicts, job loss, network disadvantage, and lack of transportation modes, as well as neighborhood-level and regional determinants, such as crime and poverty rates and the degree of car dependency. However, many important questions about the conditions under which housing instability persistently occurs over time remain largely unanswered.

In many cases, residential mobility has an entirely different meaning for low-income households. Different from high- or moderate-income households’ residential moves that occur in ways to resolve their residential dissatisfaction or disequilibrium between current and desired housing consumption (Hanushek & Quigley, Citation1978; Speare, Citation1974), low-income households’ residential moves tend to occur frequently and involuntarily. Their moves tend to be highly mobile (Coulter & van Ham, Citation2013), to fail to move beyond low-priced rental units instead of climbing up the “housing ladder” (Clark et al., Citation2003, p. 146), or to frequently rely on informal housing arrangements such as doubling up over the long term (Skobba & Goetz, Citation2013). Their moves tend to be responsive to a wide range of economic and social problems that make it hard for them to continue to stay in their current residences (Clark, Citation2010) and often lead them to substandard living environments (Desmond et al., Citation2015). In the worst case, their moves can result in a severe form of housing instability, homelessness (May, Citation2000). The accumulated evidence demonstrates the longitudinal pattern of one housing instability incident being followed by another. This pattern may reflect vicious cycles driven by the negative interactions between housing-related hardships and other dimensions of life. However, scholars are still in the early stage of generally characterizing housing instability experiences as a longitudinal phenomenon. Most empirical evidence on various triggers of housing instability and its consequences have been largely derived from studies focusing on short-term transitions, such as comparing the times right before or after a certain housing instability incident (except for Clark et al., Citation2003; Skobba & Goetz, Citation2013). To address the longitudinal nature of housing instability, I argue that a valuable first step is to place one housing instability incident within the wider life course trajectory of a household to distinguish varying trajectories reflecting housing instability. Doing so would contribute to broadening the understanding of long-term problems and disadvantages intertwined with housing instability experiences.

This study investigates low-income households’ residential trajectories by embracing the life course perspective and the associated analytic techniques. Over the last several decades, the mobility literature has increasingly examined how households’ residential environments have changed over time through residential relocations and how residential trajectories are interconnected with other aspects of their lives, such as their professional careers or changes in their family composition (Elder et al., Citation2003). Examining households’ residential trajectories through the lens of the life course perspective provides a comprehensive understanding of cumulative decisions and outcomes associated with a series of residential moves within biographical and structural contexts (Halfacree & Boyle, Citation1993) rather than simply regarding individual moves as occurring independently. To exploit this advantage, a large body of literature has analyzed the residential trajectories of households in varied contexts, such as residential attainments in terms of neighborhood poverty (Lee et al., Citation2017; Sharkey, Citation2012), housing careers from low-priced renting to high-priced ownership (Clark et al., Citation2003; Kendig, Citation1984), and the sequence of moving/staying decisions and potential mismatch between mobility desires and behaviors (Coulter & van Ham, Citation2013). However, few studies have incorporated the life course perspective in the context of housing instability, even though scholars increasingly argue that housing instability should be understood as a cumulative and longitudinal process (Kleit et al., Citation2016). With this recognition, this study investigates low-income households’ residential mobility sequences within which housing instability experiences are formulated and accrued.

In exploring residential mobility trajectories, putting an emphasis on housing instability is worthwhile for two reasons. First, it enables scholars to understand how long housing instability has persisted over time. If one housing instability incident is likely to be followed by stable housing for many low-income households, providing them with preventive interventions that alleviate housing instability at an earlier stage does not need to be prioritized. However, if housing instability tends to occur chronically over time in certain conditions, those preventive interventions are crucial to minimizing the cumulative exposure to such instability and its associated problems (Culhane et al., Citation2011; Desmond, Citation2016). Moreover, given the severe shortage of affordable housing in the United States (JCHS, 2019), unraveling the longitudinal patterns of housing instability could not be more timely.

Second, exploring low-income households’ mobility trajectories expands the knowledge about the variability in housing instability experiences—for example, between those who have chronically suffered from housing instability and those who have experienced it occasionally—and about certain vulnerable subpopulations that are likely to experience more chronic forms of housing instability. This examination provides a more comprehensive understanding of housing instability experiences beyond the snapshot based on the simple distinction between housing stability and instability at a certain time, which has been widely used in existing studies (Cox et al., Citation2017). Through this examination, the subpopulations that are the most vulnerable to chronic forms of housing instability can be identified, and this knowledge can help with devising unique strategies for alleviating different types of housing instability experiences.

This study has two central purposes. First, by incorporating multiple and robust measures for housing instability, this study examines the associations between one housing instability incident of varying degrees of severity at a particular time and subsequent mobility trajectories up to six years after the incident. By doing so, this study examines the extent to which housing instability can be viewed as a longitudinal process that continuously occurs over a long-term period. Second, this study analyzes the residential trajectories of low-income households to distinguish different types of mobility experiences, placing a particular emphasis on the frequency of housing instability incidents. As such, this study aims to identify distinctive residential mobility trajectories that reflect chronic or occasional housing instability. After that, I explore the characteristics of households that are likely to suffer from more persistent forms of housing instability.

To achieve the research objectives above, I analyzed the residential mobility trajectories of 2,370 low-income households that participated in the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) from 2003 to 2017. I established a unique panel dataset built on multiple data sources, including the public PSID data, the PSID Event History Calendar Between-Wave Moves (Between-Wave Moves) data, the PSID Geocode Match file, and Assisted Housing Database (AHD). In this study, a housing instability incident is defined as frequent, involuntary, or nonnormative residential moves measured according to the following aspects of residential mobility: (1) transience (frequently moving within a given period), (2) involuntariness (moving for involuntary reasons), and (3) nonnormativeness (moving to precarious housing conditions). Based on the operationalized definitions of a housing instability incident, I incorporated sequence analysis to identify distinctive residential trajectories (hereafter the term a sequence is used interchangeably). These groups include (1) chronically unstably housed (CUH) households, (2) mostly unstably housed (MUH) households, (3) mostly stably housed (MSH) households, and (4) consistently stably housed (CSH) households. Based on this categorization, I estimated a series of logistic regression models to explore the unique characteristics of households that are likely to fall in each group.

Measuring residential mobility as a symptom of housing instability

In this section, I briefly review the literature to rationalize my approach to measuring a housing instability incident. I conceptualize that housing instability is not a single moving event but a phenomenon that can be captured by considering multiple aspects of residential mobility. To overcome limitations that originate from relying only on a single aspect of mobility, I focus on accounting for three dimensions of residential mobility based on the previous literature.

The first dimension is residential transience, which usually refers to the frequency of housing change during a given period. Residential transience is often defined as situations where people move in an unsettled way between dwellings and do not have a stable long-term residence (Coulter et al., Citation2016). Having a stable residence yields social and physical stability. In contrast, frequent changes in residence can destabilize many dimensions of life and minimize the extent to which one can develop a sense of attachment and maintain social ties and daily routines in surrounding environments (German et al., Citation2007). This aspect of residential mobility has been measured by asking households how many times they moved in a given period. For example, the retrospective period could be the past six months (Davey-Rothwell et al., Citation2008; German et al., Citation2007), the past year (Carrion et al., Citation2015; Cutts et al., Citation2011), or the past three years (Burgard et al., Citation2012). In most cases, residential transience measures have incorporated the simple distinction of whether a household was transient. However, relying only on this dimension could be problematic when households frequently move to adjust their residential environments actively to their changing needs—many of which can be viewed as an improvement—for housing, education, and employment.

The second dimension is involuntariness, which usually indicates whether a household moved for involuntary reasons. Some households are forced to move from their homes for reasons beyond their control. In previous studies, the measurement of involuntariness has heavily relied on the answer to the question, “Why you moved?” (Heller, Citation1982). Based on Rossi’s widely cited book, Why Families Move, the mobility literature has examined expressed reasons for moving to reveal housing and neighborhood characteristics that households seek to change in their relocation processes (Rossi, Citation1955). In particular, measuring self-reported reasons for moving has been widely accepted as a way to distinguish involuntary moves from moves that voluntarily occur (Desmond & Shollenberger, Citation2015). However, some scholars have expressed concerns that self-reported reasons for moving should be interpreted with some caution because the reasons people retrospectively report for moving may reveal only part of the story about why they moved (Coulter & Scott, Citation2015; Halfacree & Boyle, Citation1993).

The third dimension is nonnormativeness, which indicates whether a household moved to precarious living conditions—or at least not superior conditions compared to previous locations (Clark et al., Citation2003; Collins & Curtis, Citation2011; Feijten & van Ham, Citation2010; Kleinhans, Citation2003; May, Citation2000; Skobba & Goetz, Citation2013 ). Clark et al. (Citation2003) found that the majority of Americans moved from renting to homeownership, improving their housing tenure and quality with successive moves. Meanwhile, in their study, very low-income populations tended to show descending or stagnated housing careers manifested by sequences that do not lead to improvements in housing tenure status and living arrangements over time. One limitation of merely focusing on this nonnormativeness dimension of mobility is that if the data only cover a short period, it is challenging to distinguish one-time setback or voluntary nonnormative moves (e.g., empty nesters) from housing instability; these are two different situations that may require different policy supports.

Many studies have largely relied on examining a single dimension of residential mobility as a symptom of housing instability, primarily because of data constraints (Cox et al., Citation2017). Recently, a few scholars have strived to capture the multidimensional aspects of housing instability by developing unique and comprehensive measures (Burgard et al., Citation2012; Geller & Curtis, Citation2011; Geller & Franklin, Citation2014; Kang, Citation2019; Routhier, Citation2018). Based on the recognition that if housing instability is broadly defined as a state of residential mobility with a lack of control over mobility decisions, relying on a single indicator may not accurately capture the essence of housing instability, the best possible way to measure housing instability may be to use multiple measures to take into account multidimensional aspects. Thus, based on the three dimensions of housing instability drawn from the previous literature, this study incorporates three indicators that reflect these different aspects (details about the indicators are introduced in the following section).

Data and methods

The analysis in this study relies on the PSID, a nationally representative panel survey of households in the United States. The PSID began in 1968 with approximately 5,000 households and has followed them and their descendants over time. Given the focus of this study on examining long-term trajectories of low-income households, I selected the sample households by applying the following sample selection rules.

First, among all PSID surveys collected from 1968, I only used the observations from 2003 to 2017, which constitute eight surveys with two-year gaps. This period was selected mainly because the Between-Wave Moves data that contain detailed information about the total number of residential moves that occurred between two consecutive PSID surveys only cover the period after 2003.

Second, following the conventional way to analyze residential trajectories of households (Lee, Citation2017; Lee et al., Citation2017), this study focuses on household-level PSID data. Basically, residential mobility has been known as the outcome of a household-level decision. This household-level approach can be rationalized by the fact that the ability of a household to avoid housing instability is formulated collectively by individual members of the household. This approach is also expected to minimize potential biases originated from the loss of the sampled households.

Third, given the focus on low-income households, I included low-income households that were low income at the first two waves (i.e., 2003 and 2005) of the entire panel period. According to the definition of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), low-income households are defined as households whose annual household incomes were below 80% of the area median income (AMI) for their local housing markets. Based on this definition, by using the PSID Geocode Match file that provides the location information of sample households at a certain time, 80% of AMI for their housing market is compared with the sample households’ incomes at a particular year. By doing so, the analytic sample successfully extracts low-income households’ residential trajectories and excludes relatively affluent and highly mobile professionals who should not be viewed as being unstably housed households.

Fourth, to preserve the quality of mobility trajectories, the analytic sample includes households that responded to all eight PSID surveys, and households with missing values for key variables used to measure housing instability were excluded. According to the sequence analysis literature, there is no specific threshold for the minimum length of sequences, but there is the agreement that sequence length is important for cluster quality (Dlouhy & Biemann, Citation2015; Studer & Ritschard, Citation2016). Based on the sample selection rules above, in total, 18,960 observations for 2,370 households (approximately 57% of the selected low-income households) were selected.

I addressed the potential biases resulting from these sample selection rules by incorporating Heckman’s two-stage selection method. I firstly estimated the first-stage probit model based on the sample of the entire low-income households (the results are presented in Appendix B) and then included the estimated selection bias variable constructed by the estimated probability that a household is selected in the analytic sample—widely called lambda—in main regression models. The results derived from the probit first-stage model reveal that the excluded households, in other words, truncated trajectories of low-income households tend to experience fluctuations between being a couple and being a single, not to continuously stay with children, to be relatively older, to indicate low educational attainments, to have an unstably employed member, and to have a member with health problem, and to reside in socially distressed neighborhoods consistently. The differences listed above show that the analytic sample tends to exclude those who have vulnerabilities and instabilities in non-housing dimensions. Thus, despite the inclusion of the selection bias variable (Lamda), the results should be interpreted as conservative estimates of relationships between different mobility trajectories and other life trajectories.

Measuring the severity of a housing instability incident

Based on the review introduced in the previous section, I measured a housing instability incident at a certain time (hereafter, called an element variable, which is commonly used in the sequence analysis literature) by examining the three dimensions of residential mobility that reflect housing instability: (1) transience, the total number of residential moves within an approximately two-year period; (2) involuntariness, whether a household moves due to involuntary reasons; and (3) nonnormativeness, whether a household ends up living in precarious housing conditions including unaffordable, overcrowded, or doubled-up housing after moving. presents the details of the identification rules.

Table 1. Categories of housing instability incidents based on three dimensions of residential mobility.

By combining the detailed information related to reasons for moving, housing and utility costs, overcrowding as indicated by the number of rooms per person, and doubled-up housing (e.g., living with another household without paying rent), this study categorized each observation—that is, each household-period—into the following four cases: (1) staying, (2) conventional mobility, (3) housing instability, and (4) severe housing instability.Footnote1

Classification of mobility trajectories

Based on the categorization of the four values of the element variable at a certain time, I classified the sample households’ mobility trajectories by incorporating sequence analysis. Sequence analysis was originally developed by biologists to compare DNA sequences and quantify the extent to which two DNA strands are homologous to each other. Thus, sequence analysis enables researchers to compare sequences of large numbers of individuals, identify similarities, quantify distances between sequences, and classify them (Brzinsky-Fay & Kohler, Citation2009). In this study, the unit of analysis is a low-income household’s entire sequence from 2003 to 2017—which is also called a trajectory.

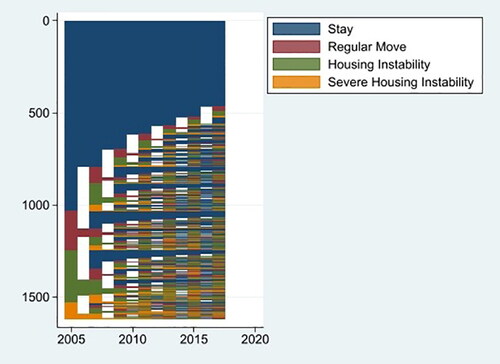

This study tracks 2,370 sequences of the element variable, which can be visualized as a series of individual timelines representing how each household did or did not experience housing instability over time (see ). Although the varying severities of housing instability incidents have been the subject of a growing body of literature (O’Campo et al., Citation2016; Routhier, Citation2018), this study’s focus highlights the interconnection between the severity and persistence of housing instability experiences by analyzing an entire sequence rather than just one incident.

Following the previous literature on low-income households’ residential trajectories (Coulter & van Ham, Citation2013; Lee et al., Citation2017), this study uses the optimal matching (O.M.) method to quantify the distance between all pairs of sequences and classify them (Brzinsky-Fay et al., Citation2006). In applying the O.M. method, this study regards being a stayer and a conventional mover as the status of being stably housed. Based on this, this study sets the baseline sequence as a sequence without any housing instability incident—including both housing instability and severe housing instability incidents. This baseline sequence can consist of the combination of staying and conventional mobility based on the assumption that conventional moves occur voluntarily to adjust for changing housing needs along with life course. The calculated distances from each sequence to the baseline sequence are used to classify the sequences into the four groups: (1) chronically unstably housed (CUH) households, (2) mostly unstably housed (MUH) households, (3) mostly stably housed (MSH) households, and (4) consistently stably housed (CSH) households.

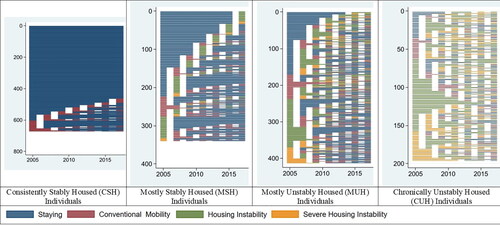

displays the descriptive features of the four types of mobility sequences. Among the sampled households 277 of them are CUH households (approximately 12%) and 472 of them are MUH households (approximately 20%). The majority of the sample households did not experience any housing instability incident at all from 2003 to 2017 (approximately 36%) or show sequences where housing instability sometimes occurred (approximately 32% of the sample). As a supplementary analysis to validate the categorization of mobility trajectories into the four groups, I examined the prevalence of the four values of the element variable across the typology of mobility trajectories. presents the average numbers of the four static housing statuses from 2003 to 2017. As expected, CSH households did not experience any housing instability incident, and MSH households rarely experienced housing instability incidents, whereas MUH and CUH households experienced housing instability incidents multiple times. In particular, CUH households experienced staying and conventional mobility less than twice on average. In contrast, they experienced housing instability incidents more than three times and severe forms of housing instability more than twice. This supplementary analysis confirms that the O.M. method appropriately classifies the mobility sequences for the comparisons between the four groups.

Table 2. Four types of residential trajectories among low-income households.

Table 3. The average numbers of housing instability statues from 2003 to 2017.

To examine how the different types of mobility sequences are associated with other households’ life trajectories, I estimated a series of logistic regression models that explain the likelihood that a household experiences a particular sequence type. Developing Coulter and van Ham’s (Citation2013) empirical model, I included a set of independent variables that might be associated with experiencing housing instability in general. Some variables capture time-invariant characteristics of the sample households, whereas the other variables summarize trajectories of each household in various life dimensions over the period between 2003 and 2009, which covers the first half of the study period.

The growing body of literature points out that racial minorities, female-headed households with children (Desmond, Citation2012; Desmond et al., Citation2013; Greenberg et al., Citation2015; Lundberg & Donnelly, Citation2019), and those who experience repeated transitions in adult members within a household (Desmond & Perkins, Citation2016) can be more vulnerable to involuntary forms of residential mobility than their counterparts. Thus, the variables related to race, gender, children, marital status are included. Also, the propensity to move generally varies with age (Rossi, Citation1980). Those in their early life stages can be more vulnerable to housing instability due to their relatively less established economic conditions (McDonald, Citation2011). Thus, the variables related to age groups are included. Considering that housing scholars have viewed homeownership as the status of housing security compared to renting for a long time (Clark et al., Citation2003; Colic‐Peisker & Johnson, Citation2010; Pendall et al., Citation2012), a set of trajectory variables related to housing tenure transitions are included. Also, job security and having health problems limiting the ability to work can affect financial insecurity and eventually increase the likelihood of experiencing housing instability (Desmond & Gershenson, Citation2016b; Kang, Citation2019), so relevant variables are included. Receiving housing assistance can significantly reduce the risk of housing instability (Kang, Citation2021), so the variable that indicates the receipt of housing assistance is included. Lastly, the literature highlights that the risk of experiencing housing instability is not uniformly distributed across neighborhoods (Desmond & Gershenson, Citation2016b; Kingsley et al., Citation2012; Raymond et al., Citation2018; Rutan & Desmond, Citation2021; Shelton, Citation2018). Especially, low-income households may enter distressed neighborhoods when they suffer from housing instability and may move again to recover the quality of neighborhoods shortly (Desmond & Shollenberger, Citation2015). To take into account neighborhood-related factors that might influence the likelihood of experiencing housing instability, I measured socially distressed neighborhoods based on the methodology developed by Kasarda (Citation1993) and created a set of variables that indicate neighborhood trajectories between 2003 and 2009. The details of descriptive statistics are presented in Appendix A.

Empirical results

To explore how one housing instability incident is associated with the following mobility trajectories, I descriptively analyzed wave-to-wave transitions for all combinations of the element variable’s values at two different times and found several noteworthy patterns (see ). First, the results indicate that strong state dependency exists over time. For example, if a household stayed in one place during a certain period, that status is likely to remain over time. Among the 8,564 cases indicating staying, approximately 81% of them retained the same status after two years, and among the 5,786 cases indicating staying, approximately 79% of them remains the status after six years. Meanwhile, relatively milder forms of housing instability incidents tend to be followed by another milder form of housing instability. In the case of severe housing instability incidents, this dependence pattern becomes even stronger. Among the cases that indicate a severe housing instability incident, 22% (255 cases) were followed by another severe housing instability incident within the following two years, and 14% of the cases showed a severe housing instability incident after six years. This state-dependent pattern demonstrates that one status indicating housing instability at a certain time is closely associated with following statuses over time.

Table 4. Wave-to-wave transitions for all combinations of housing instability statuses at two different times.

Second, demonstrates the potential interconnection between the severity of a certain housing instability incident and its persistence. From a short-term perspective, severe forms of housing instability incidents are likely to be followed by another housing instability incident either severe in form or milder. In contrast, they are less likely to be followed by the status of staying. Compared to severe forms of housing instability incidents, milder forms are less likely to be followed by severe housing instability incidents. Moreover, compared to other potential combinations, infrequently does a household experience severe housing instability at some point and then successfully achieve staying within two years (approximately 23%). It is also rare for a household to stay at some point and then experience severe housing instability incidents subsequently within two years (approximately 2%). Compared to mild forms of housing instability incidents, severe forms are likely to be followed by other housing instability experiences after six years. Thus, in general, mild forms of housing instability are likely to be followed by relatively stable housing statuses, whereas severe forms of housing instability are likely to be followed by another housing instability experience. This pattern suggests that once households fall into severe degrees of housing instability, they may experience persistent housing instability that may have cumulative effects over time.

Third, both mild and severe forms of housing instability incidents are likely to be followed by conventional mobility. This conventional move may be driven by the motivation to regain housing needs generated by previous housing instability incidents. As Desmond et al. (Citation2015) suggest, households that experience involuntary forms of residential mobility often sacrifice some aspects of their residential environments, such as neighborhood quality or the size of a housing unit, due to various constraints, and they tend to move again soon to regain those environments.

To present households’ mobility biographies, provides a visualization of all mobility sequences of the sample from 2003 to 2017. Each horizontal line represents the sequence of each household, with the colored blocks indicating the values of the element variable recorded at each time. indicates that among low-income households, a large portion of them stayed in their residences for a long time (presented as long blue lines) while adjusting their residential environments through conventional mobility (presented as red lines). However, also demonstrates that housing instability incidents are relatively common among low-income households because the green and yellow lines appear in the majority of the sample households’ sequences. This descriptive information suggests that many low-income households have various mobility sequences that represent their heterogeneous residential histories.

To explore the four types of mobility sequences separately, presents plots of individual sequences within each type. Most households in the CSH group continued to stay in their residences over multiple years or the entire panel period. Some CSH households occasionally experienced conventional moves, presumably to adjust their housing units according to their changing housing needs. In the group of MSH households, housing instability incidents tend to last no more than two consecutive waves (approximately four years). Moreover, after they experienced housing instability once, they were likely to experience conventional mobility or staying. This pattern suggests that housing instability experience can be a temporary hardship for some households and that they are likely to move again for nonnegative reasons. MUH households tend to experience housing instability much longer than MSH households. In some cases, MUH households experienced a combination of mild and severe forms of housing instability for more than two consecutive waves or experienced housing instability incidents at two different time points during the study period. Not surprisingly, in the case of CUH households, most blocks of the sequences consist of housing instability experiences. They tend to keep experiencing housing instability and conventional moves, and they rarely stayed in the same residence over two consecutive waves.

To explore the associations between mobility sequences and other life trajectories as a predictor based on the four types of housing instability sequences presented in estimated a series of logistic regression models. The multivariate models include a set of time-invariant variables as well as variables that summarize other life trajectories between 2003 and 2009, and the results are presented in .

Table 5. Logistic Regression Results.

Model 1 compares CSH households—those who never experienced any housing instability incident—with MSH households—those who experienced housing instability sporadically over the study period. The results reveal that compared to CSH households, MSH households tend to be consistently widowed, divorced, or separated, or to fluctuate between being a couple and being single. This finding is consistent with Desmond and Perkins (Citation2016)’s study highlighting the strong relationship between transitions in adult members and housing instability. Additionally, compared to CSH households, MSH households were likely to have at least one child, suggesting that the presence of children may place low-income households at a heightened risk of housing instability (Desmond et al., Citation2013; Kang, Citation2019). Compared to those who stably maintained homeownership status, households that consistently rented, entered homeownership, or experienced fluctuation between renting and owning between 2003 and 2009 were more likely to belong to the MSH group. Also, in this comparison, households were likely to be MSH households when the households’ heads were in earlier life stages, particularly those under 30 in 2003. Also, being a household with at least one unstable income source and fluctuating between a household with and without a member with health problems were likely to be MSH households compared to CSH households. Lastly, households that consistently moved in and out of socially distressed neighborhoods over the period were likely to be MSH households, suggesting that households occasionally experienced housing instability when they voluntarily and involuntarily escaped from distressed neighborhoods (Darrah & Deluca, Citation2014; Desmond & Shollenberger, Citation2015).

Model 2 compares MUH households (DV = 1) with MSH households (DV = 0). The likelihood of being a MUH household was relatively high when household heads were female. This finding is consistent with the recent findings indicating that the risk of housing instability can be gendered. Also, the households were likely to be MUH households, (1) when they consistently rented or fluctuated between owning and renting between 2003 and 2009, (2) when they were in earlier life stages, and (3) when they exited no-income households or fluctuated between one- and no-income household. Similar to the findings from Model 1, compared to MSH households, MUH households tend to move in and out of socially distressed neighborhoods over the period. This finding reflects the possibility that when low-income households exited distressed neighborhoods due to substandard housing and neighborhood conditions (Desmond & Shollenberger, Citation2015; Kingsley et al., Citation2012), they may not have achieved housing stability in new places and may have returned to distressed neighborhoods. This returning move may occur voluntarily (e.g., moving for larger space by giving up neighborhood quality) or involuntarily (e.g., being evicted or foreclosed).

One counterintuitive finding is that African American households were less likely to be MUH households than non-Hispanic White households. This finding is somewhat surprising given the high prevalence of homelessness, especially family homelessness, among African American households (National Alliance to End Homelessness, Citation2020). This association is statistically significant after controlling for various hardships that African American households are likely to be exposed to—for example, job insecurity, lack of wealth, or discriminatory practices of landlords against female-headed households or families with children. Thus, the association may capture some hidden benefits that African American households are likely to receive compared to non-Hispanic White households. These benefits may include receiving formal supports from social and homeless programs that are designed to target African American households disproportionately. For example, despite the highest rate of homelessness among African American households, they may not be disproportionately harmed because they are most likely to receive shelter services; according to one recent report, in 2018, only 23% of African American households are unsheltered, whereas approximately 50% of Native Americans are not. Or, African American households may achieve relatively stable residential trajectories by receiving informal supports from families or community networks (e.g., congregation/church networks) (Sarkisian & Gerstel, Citation2004; Taylor et al., Citation2013), even though there should be further studies that examine the factors that actually help them stably housed.

Model 3 compares MUH households (DV = 0) with CUH households (DV = 1) that suffered from the most chronic forms of housing instability during the study period. The results indicate that households whose heads were in earlier life stages and had relatively low educational attainments tend to be CUH households. Additionally, CUH households were likely to have a member with health problems, suggesting that chronic forms of housing instability are closely associated with household members’ capability to work. Different from the results of the previous logistic models, I mostly found no significant relationship with household employment structure, neighborhood trajectories, tenure transitions, and other sociodemographic characteristics, probably due to the limited sample size of MUH and CUH households. Although these findings are marginally significant, the results indicate that compared with MUH households, CUH households tend to fluctuate between being a couple and single and have no children. In particular, the presence of children was negatively associated with the likelihood of being CUH households. Although the underlying mechanisms benefitting households with children cannot be explained by the estimated model, one possible explanation is that this association may result from many social and homeless programs designed to disproportionately target households with children to help them be stably housed. Or, this pattern simply shows that CUH households may overrepresent single-person homeless households that are likely to face challenges in health, such as mental illness and substance abuse, and who are ineligible for benefit programs that favor families (Burt, Citation2001).

Discussion and conclusion

Housing instability becomes prevalent among low-income households in the United States, and a growing number of studies have pointed out that a single housing instability incident could be associated with subsequent housing instability experiences. However, few empirical studies have examined a series of housing instability experiences from a longitudinal perspective. By embracing the life-course framework and associated analytic techniques and by placing one housing instability incident into the broader life course trajectories of households, this study investigates 2,370 low-income households’ mobility trajectories based on the uniquely constructed PSID data from 2003 to 2017.

Broadly speaking, the examination of wave-to-wave transitions echoes the importance of adopting the life course perspective in understanding the longitudinal nature of housing instability. This examination confirms that the dependence of housing instability incidents does exist, and the severity and persistence of housing instability experiences are interconnected to each other. It means that some low-income households that have suffered from severe forms of housing instability incidents in the past are likely to continue suffering from housing instability for a longer time than those who experienced milder forms of housing instability or those who did not experience housing instability at all. This interdependency implies that given previous studies highlighting the detrimental impacts of housing instability on many dimensions of low-income households’ lives, the influence of more severe forms of housing instability may not be short-lived. This pattern also emphasizes the importance of examining whether such cumulative housing instability experiences affect low-income households’ lives cumulatively. For example, future research could investigate whether chronic forms of housing instability more negatively affect educational outcomes, physical and mental health, social networks, or job performance than a one-time housing instability incident. If such cumulative effects exist, benefits resulting from preventive policy interventions for alleviating housing instability at earlier stages could be much larger than previously thought.

The results derived from the multivariate analyses reveal that different types of mobility sequences are associated with different sets of predictors. First, among households that experience housing instability sporadically, the ability to maintain housing stability is closely associated with maintaining the status of homeownership. Especially if households consistently experience tenure transitions between renting and owning, they are likely to be exposed to more chronic forms of housing instability over time. However, the variables of tenure-related trajectories do not significantly explain the difference between CUH and MUH households, both of whom already experienced housing instability multiple times over their trajectories. It may be largely because both CUH and MUH households did not have opportunities for homeownership in the first place, and both groups were likely to be renters consistently. In the analytic sample of this study, only 8% of CUH households were homeowners in 2003, and only 18% of MUH households were homeowners, whereas 72% of CSH households were homeowners. These findings suggest that housing programs that provide a small emergency fund to those who are exposed to the risk of losing homeownership may work to alleviate short-term housing instability, but its role could be limited in addressing chronic forms of housing instability.

Second, one factor that significantly explains the differences between the four groups is a household head’s age. Generally, the risk of more persistent forms of housing instability is high among those under 30 or those between 30 and 49. This vulnerability of younger households to chronic forms of housing instability is understandable because they have had limited opportunities to accumulate wealth or other financial cushions to secure housing stability in response to financial shocks. Although the focus of this study is not on the transition into adulthood among those who just form their own households, it suggests that many young low-income households may start their housing careers without sufficient resources for achieving housing stability. Then, is housing instability experience transmitted to the next generations? What is the role of parents’ wealth and other economic conditions in making their adult children achieve housing stability in their early life stages? Answering these questions will shed light on the intergenerational transmission of housing instability, which could be a critical mechanism that drives the intergenerational transmission of poverty in the United States.

Third, no statistically significant difference in the likelihood of being MUH households exists between households with a stable income source and households without any income source consistently. This association remains statistically insignificant after controlling for differences in household income, suggesting that housing instability that frequently occurs may be triggered by not just a sudden loss of income but also the loss of anticipated financial shocks caused by job loss. This result implies that job insecurity and income instability, not the absence of income sources themselves, may be the key drivers that make housing instability experience occur frequently, which is consistent with findings derived from previous studies (Desmond & Gershenson, Citation2016b; Kang, Citation2019). To provide stable jobs and housing to these households, there should be programs to provide permanent housing in the way many programs based on the Housing First model have successfully done (Padgett et al., Citation2016; Pearson et al., Citation2009) as well as other social services such as counseling, treatment, and job training.

Fourth, having a member with health problems limiting the ability to work is a significant factor that contributes to making housing instability more persistent. This finding may be related to the presence of extra barriers to decent housing options, which is largely applied to households with disabled members (Hammel et al., Citation2017; Levy et al., Citation2015). Although this connection should be further examined by future studies, if this is the case, the broadened and active application of the Fair Housing Act should be considered to minimize discriminatory practices in housing markets. Generally, the findings derived from multivariate models imply that housing and social programs intended to alleviate housing instability need to take into account the unique conditions for persistent housing instability identified in this study.

Fifth, this study highlights that housing instability trajectories are closely associated with repeated moves across socially distressed neighborhoods. In the analytic sample of this study, only 2.9% of households stably resided in distressed neighborhoods between 2003 and 2009, and 18% of households repeatedly moving in and out of distressed neighborhoods. This pattern implies that, from the spatial perspective, chronic forms of housing instability do not occur simply within distressed neighborhoods and may occur across those neighborhoods in the form of multiple residential moves, including both voluntary and involuntary moves. According to the evidence from the Making Connections surveys targeting low-income neighborhoods in 10 cities in the United States, the mobility rate in distressed neighborhoods is high on average, and all their moves cannot be viewed as being completely positive or negative. Although many moves are churning moves happening within those neighborhoods (approximately 46%), a significant portion of the moves is moving out of those neighborhoods to reside in better neighborhoods (approximately 29%). Given these double-sided meanings of residential moves among low-income households, housing instability may persist longer in the form of sequential moves across distressed neighborhoods along with their life trajectories.

Many questions remain about the residential trajectories of low-income households. First, this paper does not provide clear answers about the real mechanisms through which low-income households suffer from chronic housing instability. Unraveling the potential mechanisms by incorporating dynamic modeling approaches would provide implications for preventive policies that could address chronic forms of housing instability at proper timings. Second, given the focus of this study on the variability in housing instability, this study does not closely examine the associations between conventional mobility and housing instability. This study points out that one housing instability experience is likely to be followed by certain types of voluntary and intentional mobility, which may occur to improve residential environments. However, there should be further examination of the conditions under which low-income households can make those recovery moves and where the moves lead them.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The PSID data do not provide a direct measure for doubling up. Thus, this study regards two situations as doubled-up situations: (1) where a household did not own or rent a house and lived with at least one family adult member who is neither a householder nor a marriage partner, or a nonfamily member, or (2) where a household reported that the household rented a house but paid no rent for the house, and lived with at least one family adult member who is neither a householder nor a marriage partner, or a nonfamily member. By combining multiple variables, I believe this approach well captures various situations of living with another household without contributing to housing-related payments.

References

- Beer, A. (2011) Housing Transitions through the Life Course: Aspirations, Needs and Policy, Portland, OR: Policy Press.

- Brzinsky-Fay, C. & Kohler, U. (2010) New developments in sequence analysis, Sociological Methods and Research, 38(3), pp. 359–364.

- Brzinsky-Fay, C., Kohler, U. & Luniak, M. (2006) Sequence analysis with stata, Stata Journal, 6(4), pp. 435–460.

- Burgard, S. A., Seefeldt, K. S. & Zelner, S. (2012) Housing instability and health: Findings from the Michigan recession and recovery study, Social Science & Medicine (1982), 75, pp. 2215–2224.

- Burt, M. R. (2001) Homeless families, singles, and others: Findings from the 1996 National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients, Housing Policy Debate, 12, pp. 737–780.

- Carrion, B. V., Earnshaw, V. A., Kershaw, T., Lewis, J. B., Stasko, E. C., Tobin, J. N. & Ickovics, J. R. (2015) Housing instability and birth weight among young urban mothers, Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 92, pp. 1–9.

- Clark, S. L. (2010) Housing Instability: Toward a Better Understanding of Frequent Residential Mobility Among America’s Urban Poor. (Washington, DC: Center for Housing Policy). Available at https://nhc.org/media/files/LawsonClark_analysis_for_Report.

- Clark, W. A. V., Deurloo, M. & Dieleman, F. (2003) Housing careers in the United States, 1968–93: Modelling the sequencing of housing states, Urban Studies, 40, pp. 143–160.

- Colic‐Peisker, V. & Johnson, G. (2010) Security and anxiety of homeownership: Perceptions of middle‐class Australians at different stages of their housing careers, Housing, Theory and Society, 27, pp. 351–371.

- Collins, M. E. & Curtis, M. (2011) Conceptualizing housing careers for vulnerable youth: Implications for research and policy, American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81, pp. 390–400.

- Coulter, R. & Scott, J. (2015) What motivates residential mobility? Re-examining self-reported reasons for desiring and making residential moves, Population, Space and Place, 21, pp. 354–371.

- Coulter, R. & van Ham, M. (2013) Following people through time: An analysis of individual residential mobility biographies, Housing Studies, 28, pp. 1037–1055.

- Coulter, R., van Ham, M. & Findlay, A. M. (2016) Re-thinking residential mobility: Linking lives through time and space, Progress in Human Geography, 40, pp. 352–374.

- Cox, R., Henwood, B., Rice, E. & Wenzel, S. (2017) Roadmap to a unified measure of housing insecurity, Cityscape, 21(2), pp. 93–128. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2817626

- Culhane, D. P., Metraux, S. & Byrne, T. (2011) A prevention-centered approach to homelessness assistance: A paradigm shift?, Housing Policy Debate, 21, pp. 295–315.

- Cutts, D. B., Meyers, A. F., Black, M. M., Casey, P. H., Chilton, M., Cook, J. T., Geppert, J., Ettinger de Cuba, S., Heeren, T., Coleman, S., Rose-Jacobs, R. & Frank, D. A. (2011) US housing insecurity and the health of very young children, American Journal of Public Health, 101, pp. 1508–1514.

- Darrah, J. & Deluca, S. (2014) “Living here has changed my whole perspective”: How escaping inner-city poverty shapes neighborhood and housing choice, Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 33, pp. 350–384.

- Davey-Rothwell, M. A., German, D. & Latkin, C. A. (2008) Residential transience and depression: Does the relationship exist for men and women?, Journal of Urban Health : Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 85, pp. 707–716.

- Desmond, M. (2012) Eviction and the reproduction of urban poverty, American Journal of Sociology, 118, pp. 88–133.

- Desmond, M. (2016) Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City. (New York, NY: Crown).

- Desmond, M., An, W., Winkler, R. & Ferriss, T. (2013) Evicting children, Social Forces, 92, pp. 303–327.

- Desmond, M. & Gershenson, C. (2016a) Housing and employment insecurity among the working poor, Social Problems, 63, pp. 46–67.

- Desmond, M. & Gershenson, C. (2016b) Who gets evicted? Assessing individual, neighborhood, and network factors, Social Science Research, 62, pp. 362–377.

- Desmond, M., Gershenson, C. & Kiviat, B. (2015) Forced relocation and residential instability among urban renters, Social Service Review, 89, pp. 227–262.

- Desmond, M. & Kimbro, R. T. (2015) Eviction’s fallout: Housing, hardship, and health, Social Forces, 94, pp. 295–324.

- Desmond, M. & Perkins, K. L. (2016) Housing and household instability, Urban Affairs Review, 52, pp. 421–436.

- Desmond, M. & Shollenberger, T. (2015) Forced displacement from rental housing: Prevalence and neighborhood consequences, Demography, 52, pp. 1751–1772.

- Dlouhy, K. & Biemann, T. (2015) Optimal matching analysis in career research: A review and some best-practice recommendations, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 90, pp. 163–173.

- Elder, G. H., Johnson, M. K. & Crosnoe, R. (2003) The emergence and development of life course theory, in: J.T. Mortimer & M.J. Shanahan (Eds) Handbook of the Life Course, pp. 3–19. (New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers).

- Fargo, J. D., Munley, E. A., Byrne, T. H., Montgomery, A. E. & Culhane, D. P. (2013) Community-level characteristics associated with variation in rates of homelessness among families and single adults, American Journal of Public Health, 103(Suppl 2), pp. S340–S347.

- Feijten, P. & van Ham, M. (2010) The impact of splitting up and divorce on housing careers in the UK, Housing Studies, 25, pp. 483–507.

- Florida, R. & Schneider, B. (2018) The global housing crisis, Citylab. https://www.citylab.com/equity/2018/04/the-global-housing-crisis/557639/

- Geller, A. & Curtis, M. A. (2011) A sort of homecoming: Incarceration and the housing security of urban men, Social Science Research, 40, pp. 1196–1213.

- Geller, A. & Franklin, A. W. (2014) Paternal incarceration and the housing security of urban mothers, Journal of Marriage and the Family, 76, pp. 411–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12098

- German, D., Davey, M. A. & Latkin, C. A. (2007) Residential transience and HIV risk behaviors among injection drug users, AIDS and Behavior, 11, pp. 21–30.

- Greenberg, D., Gershenson, C., Desmond, M., Harris, D., Caramello, P. E., Fallon, R. & Greiner, D. J. (2015) Discrimination in evictions: Empirical evidence and legal challenges, Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, 51, pp. 115–158.

- Halfacree, K. H. & Boyle, P. J. (1993) The challenge facing migration research: The case for a biographical approach, Progress in Human Geography, 17, pp. 333–348.

- Hammel, J., Smith, J., Scovill, S. & Duan, R. (2017) Rental Housing Discrimination on the Basis of Mental Disabilities: Results of Pilot Testing, Government Printing Office. (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development).

- Hanushek, E. A. & Quigley, J. M. (1978) Housing market disequilibrium and residential mobility, in: W. A. V. Clark & E. G. Moore (Eds) Population Mobility and Residential Change, pp. 51–98). (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University).

- Heller, T. (1982) The effects of involuntary residential relocation: A review, American Journal of Community Psychology, 10, pp. 471–492.

- Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. (2019) The State of the Nation’s Housing 2019. (Cambridge, MA).

- Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. (2020) America’s Rental Housing 2020. (Cambridge, MA).

- Kang, S. (2019) Why low-income households become unstably housed: Evidence from the panel study of income dynamics, Housing Policy Debate, 29, pp. 559–529.

- Kang, S. (2021) To whom do housing policies provide stable housing? Examining housing assistance recipients and leavers, Urban Affairs Review, 57, pp. 1252–1285.

- Kang, S. (2021) Beyond households: Regional determinants of housing instability among low-income renters in the United States, Housing Studies, 36, pp. 80–109.

- Kasarda, J. D. (1993) Inner‐city concentrated poverty and neighborhood distress: 1970 to 1990, Housing Policy Debate, 4, pp. 253–302.

- Kendig, H. L. (1984) Housing careers, life cycle and residential mobility: Implications for the housing market, Urban Studies, 21, pp. 271–283.

- Kingsley, G. T., Jordan, A. & Traynor, W. (2012) Addressing residential instability: Options for cities and community initiatives, Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research, 14, pp. 161–184.

- Kleinhans, R. (2003) Displaced but still moving upwards in the housing career? Implications of forced residential relocation in The Netherlands, Housing Studies, 18, pp. 473–499.

- Kleit, R. G., Kang, S. & Scally, C. P. (2016) Why do housing mobility programs fail in moving households to better neighborhoods?, Housing Policy Debate, 26, pp. 188–209.

- Lee, K. O. (2017) Temporal dynamics of racial segregation in the United States: An analysis of household residential mobility, Journal of Urban Affairs), 39, pp. 40–67.

- Lee, K. O., Smith, R. & Galster, G. (2017) Neighborhood trajectories of low-income U.S. households: An application of sequence analysis, Journal of Urban Affairs, 39, pp. 335–357.

- Levy, D. K., Turner, M. A., Santos, R., Wissoker, D., Aranda, C. L., Ritingolo, R. & Ho, H. (2015) Discrimination in the Rental Housing Market against People Who are Deaf and People Who Use Wheelchairs: National Study Findings, Washington, DC: The Urban Institute.

- Lundberg, I. & Donnelly, L. (2019) A research note on the prevalence of housing eviction among children born in U.S. Cities, Demography, 56, pp. 391–404.

- May, J. (2000) Housing histories and homeless careers: A biographical approach, Housing Studies, 15, pp. 613–638.

- McDonald, L. (2011) Examining evictions through a life-course lens, Canadian Public Policy, 37, pp. S115–S133.

- National Alliance to End Homelessness. (2020) Homelessness and Racial Disparities. https://endhomelessness.org/homelessness-in-america/what-causes-homelessness/inequality/

- O’Campo, P., Daoud, N., Hamilton-Wright, S. & Dunn, J. (2016) Conceptualizing housing instability: Experiences with material and psychological instability among women living with partner violence, Housing Studies, 31, pp. 1–19.

- Oishi, S. (2010) The psychology of residential mobility: Implications for the self, social relationships, and well-being, Perspectives on Psychological Science : A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 5, pp. 5–21.

- Padgett, D. K., Henwood, B. F. & Tsemberis, S. J. (2016) Housing First: Ending Homelessness, Transforming Systems, and Changing Lives, New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Pearson, C., Montgomery, A. E. & Locke, G. (2009) Housing stability among homeless individuals with serious mental illness participating in housing first programs, Journal of Community Psychology, 37, pp. 404–417. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20303

- Pendall, R., Theodos, B. & Franks, K. (2012) Vulnerable people, precarious housing, and regional resilience: An exploratory analysis, Housing Policy Debate, 22, pp. 271–296.

- Phinney, R. (2013) Exploring residential mobility among low-income families, Social Service Review, 87, pp. 780–815.

- Raymond, E. L., Duckworth, R., Miller, B., Lucas, M. & Pokharel, S. (2018) From foreclosure to eviction: Housing insecurity in corporate-owned single-family rentals, Cityscape, 20, pp. 159–188. https://login.lp.hscl.ufl.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/2174191318?accountid=10920

- Rossi, P. H. (1955) Why Families Move: A Study in the Social Psychology of Urban Residential Mobility, New York, NY: Free Press.

- Rossi, P. H. (1980) Why Families Move, 2nd ed. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publication.

- Routhier, G. (2018) Beyond worst case needs: Measuring the breadth and severity of housing insecurity among urban renters, Housing Policy Debate, 29(2), pp. 235–249.

- Rutan, D. Q. & Desmond, M. (2021) The concentrated geography of eviction, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 693, pp. 64–81.

- Sarkisian, N. & Gerstel, N. (2004) Kin support among blacks and whites: Race and family organization, American Sociological Review, 69, pp. 812–837.

- Sharkey, P. (2012) Temporary integration, resilient inequality: Race and neighborhood change in the transition to adulthood, Demography, 49, pp. 889–912.

- Shelton, T. (2018) Mapping dispossession: Eviction, foreclosure and the multiple geographies of housing instability in Lexington, Kentucky, Geoforum, 97, pp. 281–291.

- Skobba, K. & Goetz, E. G. (2013) Mobility decisions of very low-income households, Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research, 15, pp. 155–172.

- Speare, A. (1974) Residential satisfaction as an intervening variable in residential mobility, Demography, 11, pp. 173–188.

- Studer, M. & Ritschard, G. (2016) What matters in differences between life trajectories: A comparative review of sequence dissimilarity measures, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A: Statistics in Society, 179, pp. 481–511.

- Taylor, R. J., Chatters, L. M., Woodward, A. T. & Brown, E. (2013) Racial and ethnic differences in extended family, friendship, fictive kin and congregational informal support networks, Family Relations, 62, pp. 609–624.

- Ziol-Guest, K. M. & Mckenna, C. C. (2014) Early childhood housing instability and school readiness, Child Development, 85, pp. 103–113.