Abstract

A spectre haunts how we think about housing—describing it in binaries, in oppositions, in ‘essentialised’ identities (formal/informal, north/south, social/spatial, product/process). What does a more nuanced understanding of assemblages—drawn from the original work of Deleuze and Guattari—have to offer housing studies to move beyond such dichotomies? This paper outlines a conceptual framework where housing is re-thought as an unfolding of socio-material processual-relations and desires forming a field of intensities. This theoretical framework is used to think through empirical findings from a six-month socio-spatial ethnography conducted in Karail, the largest informal settlement in Dhaka that houses 300,000 people. The findings, seen through assemblages, allow identifying, firstly, the interconnections between different actors across different binaries that make it work and secondly, the different modes of settlement’s production itself. Lastly, the paper recasts the settlement as a manifestation of a landscape of intersecting desires in an effort to speak of housing in a new language transcending the stifling dichotomy of top-down/bottom-up.

Prologue

A spectre haunts how we think—describing the world in binaries, in oppositions, in ‘essentialised’ identities. Pragmatically useful, they appear to us as ‘common sense’ without demanding any attention. In relation to urban informality, a well-established common sensical notion in housing and urban scholarship is that often, they are seen as instances of ‘bottom-up’ relationalities and are ‘self-organised’ in terms of their production processes (while too numerous to cite how many papers use these terms, see recent work by Kamalipour, Citation2016; Suhartini & Jones, Citation2020; Hernández-García & Hernández-García, Citation2021). A recently edited volume by Arefi and Kickert (Citation2019) seeks to ‘connect the recent trend of bottom-up efforts in the West with urban informality in the Global South’, furthering such notions. Another recent paper by Streule et al. (Citation2020), aims to transcend the term informal for its ‘lack of differentiation of the various ways in which informality emerges and develops’—with which the content of this paper wholly agrees—and uses the term ‘popular urbanization’. However, in defining it, they fall back on the all-familiar use of ‘self-organization’ (p. 666).

My own experiences—from the deep ethnographic fieldwork in one such settlement, Karail in Dhaka—has made me aware that such terms offer little value to explain what I came across. At the end of my fieldwork, I could not describe the settlement as being bottom-up, for there were many levels of top and bottom within it. Nor could I say it was self-organised, as there were simultaneous processes that involved multitude of actors (human and non-human)—too plural to question who the ‘self’ is in a so-called self-organized settlement. Given the formalities and protocols of urban governance I encountered there, it might be contradictory to call such a settlement as ‘informal’. However, I use it in a very particular sense to denote a settlement that has been produced outside the state-or-capital-led planning process (see our recent paper on the conceptual distinction between informal settlements and slums, Dovey et al., Citation2021).

The challenge of this paper, then, is to bypass the use of these familiar binaries and established terms in describing how housing is produced and maintained in such a settlement in Dhaka. I will be utilising assemblage thinking, as articulated by Deleuze and Guattari, to develop a vernacular to do so. However, rather than using jargons as simply a ‘theoretical manoeuvre’ (Simone, Citation2016, p. 6), the task here will be to construct an abductive theory that explains the empirical.

Therefore, firstly, a conceptual framework is generated that connects disparate notions within assemblage thinking. Rather than being simply descriptive of secondary work, this framework itself is an analysis of assemblage thinking and an attempt to extract a clear toolkit that can be used widely. Using it, the paper presents a new vernacular, where housing relationalities are rethought in terms of tendencies of entanglements, the ongoing processes are differentiated in terms of mechanisms of production and the relations and process are further explained by developing the concept of landscape of desires. The paper will conclude by showing how such a re-reading can help shape potential actions, policies and instrumentalities for an alternative housing future.

The need to re-think housing is even more evident in a Post-COVID world. The pandemic has painted the ‘global risk society’ (Beck, Citation2016) we find ourselves in with a neon glow. It has made apparent how housing injustices continue to perpetuate in many guises across the world, caring little for the global North/South divide, where billions of people continuing to live in inadequate housing (UN-Habitat, Citation2016). This paper speaks of housing in informal settlements, but it is hoped that the assemblage analytical framework is helpful across wider housing and urban scholarship.

A brief note on assemblages

Storper and Scott (Citation2016) count assemblage thinking as one of the key schools of thought in urban studies discourse. While it has been used widely across urban geography, urban studies and planning (McFarlane and Anderson, Citation2011; Thrift, Citation2008; Dovey, Citation2016; Purcell, Citation2013), there is a paucity when it comes to housing research. Notable instance of its use for analytical work is most potent in Koster’s (Citation2015) study of social housing in the Netherlands and Lea’s (Citation2015), study of indigenous public housing in Australia. However, in many cases, even when a work uses assemblage in housing studies research—as an example see Maalsen’s work on re-thinking the smart home as an assemblage (Maalsen, Citation2020)—there is often no deeper engagement in depth with the philosophical concepts within the work of Deleuze and Guattari. In other words, while assemblages have been useful to show the relationality of the world across socio-material binaries, perhaps there is more analytical purchase if one were to delve deeper.

Explicitly making this point, Buchanan (Citation2015) laments that assemblage thinking, devoid of the specificities found in the original works of Deleuze and Guattari, often is used for its capacity to link disparate elements without understanding the role of desire as underlying mechanisms of the assemblage. In other words, often ‘assemblage’ is used simply as a synonym for ‘collection of things’—an otherwise arbitrary ‘compilation’ of heterogeneous entities—rather than to analyse the ‘composition’ of the elements (Buchanan, Citation2015). This is not to say that the usage of assemblage thinking is to be policed or there is only a right version of it, but rather, in housing and urban scholarship, there is a scope to go beyond the generic usage of assemblage to unearth particular concepts that may provide a way to go beyond binaries. The coming section, which may seem like a theoretical detour, precisely is necessary to make sense of the analysis conducted in the latter part. Hopefully, this will help to avoid charges of ‘naïve objectivism’ (Brenner et al., Citation2011) and lack of analytical depth (Buchanan, Citation2017)—the case often made against using assemblage.

Assemblage thinking is based on the philosophical work of Deleuze (Difference and Repetition, Deleuze, [1968] Citation1994) and his later collaboration with Guattari (A Thousand Plateaus, 1988). Deleuze talks of thinking in rhizomes, referring to roots that grow interconnected in all directions. However, this notion is a continuation of the minor strand of Western philosophy—such as the work by Spinoza, Hume, Leibniz, Nietzsche, Bergson, Hjelmslev and Bateson—all of whom saw reality as interconnected and fluid. This minor strand can be broadly identified as processual-relational (Ivakhiv, Citation2014), in the sense that it posits reality as flowing, contingent and emergent—to consist of processes and relations that only appear to our common sense as fixed identities. It’s a world of becomings.

What it implies for research is that it is important to identify the immanent processes and relations that produce the world i.e. ‘the movement, forces, speeds and intensities’ (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1988) but also to ask what holds them together. The question isn’t ‘what is?’ but rather ‘how does it work?’, ‘what is it doing?’, ‘How is it maintained?’ (Holubec, Citation2014). By focusing on how this world works, rather than what it is, assemblage thinking allows us to ask, ‘given a certain effect [say, the proliferation of substandard council housing in a city], what kind of machine (assemblage) is capable of producing it?’ (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1988: 3). For our purposes here, the question is: what kind of assemblages have produced the settlement under investigation? What are the processes and relations that holds it together and makes it work? Are there underlying logic organizing these processes and relations?

In other words, in thinking through housing realities, perhaps we ought not to limit ourselves as providing thick descriptions, rich empirical insights, and nuanced observations about only the interconnectedness of things. The task is to transcend the relationalities we identify, and to arrive at underlying apparatus that hold heterogenous formations together in producing that effect—in what Deleuze had called transcendental empiricism (St. Pierre, Citation2016). Therefore, this is an explicit call within assemblage thinking to move beyond recent relational turn, and dare I say even the materialist turn in social sciences—to move beyond descriptions towards identifying the logic of production of a situation/effect/condition.

Therefore, before presenting the case study, the next section will use a more in-depth engagement with assemblage thinking to extract a new but coherent language with which to speak about the empirical findings.

Conceptual framework

It has become well-known that assemblages are relations of heterogenous entities, generated via different processes, and operating with certain logics. These three aspects—the relations, processes and logic of operation form the analytic triad that will be used to investigate the empirical findings from the settlement. The first thread will be investigating how different entities within an assemblage are related and how they make the settlement work; secondly, the different modes of production which produces the housing in the settlement; and thirdly, exploration of the concept of desire as a way to identify the logic underlying the assemblage.

It might be useful to think of assemblages being composed of two series of interrelated things. The first is ‘a machinic assemblage of bodies, of actions and passions, an intermingling of bodies reacting to one another’ (bodies), and the second is ‘a collective assemblage of enunciation, of acts and statements, of incorporeal transformations attributed to bodies’ (expressions) (D&G 1988). While these two are often reduced to a material-semiotic dialectic, it is simply not. Deleuze’s concept of bodies is not just the material, since it would lead back to the dualism he was trying to avoid. Rather, bodies are composites themselves of the physical and the affective domain. The second series, that of expressions, is not simply language-as-communication either. It is the ensemble of expressions (including language but not limited to) that are performative, rather than being about representation or signs (following Speech Act Theory by Searle, 1970). An example of this is the incorporeal transformation of a man to a husband by enunciating ‘I Do’ in which the assemblage of expression transforms the bodily assemblage by the act of language. It is crucial to note that these two series within assemblages exist together and do not presuppose or cause each other (St. Pierre, 2016). The complexity is a result of interconnections of bodies and expressions—or better yet, their entanglements (see use of the word by Paddison et al., Citation1999).

Moving beyond simply describing empirically the connectedness between these, the task is to identify the kinds of entanglements based on how they operate on the ground in enabling or constraining the housing. Rather than thinking in transcendental types, we can think in terms of immanent tendencies. Tendencies in assemblage thinking are dispositions for a certain attribute to emerge based on both contingent events and inherent capacities (DeLanda, Citation2016). Bodies can show multiple tendencies simultaneously and can be in flux from one to the other, which often is missed in thinking using common-sense pre-fixed categories. The first line of inquiry then is to identify the tendencies of entanglements that make the settlement work as a housing.

The bodies and expressions entangled together in an assemblage can be quite similar to each other (homogeneous) or quite different (heterogeneous)—situated in a continuum from a territorial or repetitive extreme on one end to a deterritorialized or differentiated other. The territoriality-deterritoriality continuum determines the level of homogeneity/heterogeneity of the entities arranged. One could say a suburb is more stratified, accounting little difference in terms of, say, ethnicity as opposed to a CBD being more deterritorialized, as in it accommodates more difference. There are multiple other two-fold concepts (Dovey, Citation2016) sprinkled through-out A Thousand Plateaus (1981) as a means to understand assemblages—such as, tree/rhizome, striated/smooth, major/minor, molar/molecular, rigid/supple, hierarchy/network and state/nomad—that are analogical to territorialisation/deterritorialisation. It must be reiterated that these are not binaries but rather could be thought as two ends of a singular continuum along which assemblages move towards order (repetition) or randomness (difference).

The important takeaway here is that there are organizing mechanisms often trying to territorialize/give order/homogenize, which structures entities in one way reducing internal differences. On the other hand, some mechanisms move it away towards accommodating more difference, which makes the assemblage more heterogeneous. If reality is seen as being consisting of flows and intensities that are constantly changing, then, to explain how the settlement works as housing, it is important to ask how the settlement has emerged as such. What are the organizing mechanisms? Tracking how the settlement was territorialised or deterritorialized over time can be a key indicator of the processes involved in making those changes. Thus, the second line of inquiry for the analysis will be to identify the organizing mechanisms that have been instrumental in producing the settlement itself.

So far, we have conceptualised the relations between different entities within an assemblage and mechanisms that produce them. However, it’s important to ask what brings together the different processes and relations (the actual things). What holds them together? In assemblage thinking, what conditions the ‘actual’ are the underlying desires, dispositions and capacities, which often is termed as the ‘virtual’. The virtual operates underneath the actual and is real, rather than being ideal (DeLanda, Citation2016; Nail, Citation2017). The virtual gives assemblages specific generative conditions. As the simplest example, the virtuality of a waterfall would be the disposition for water to flow towards the lowest point. The disposition is not an actual sensed entity, but quite real, it exists and structures the potential places where water can flow. While dispositions (what a body usually does), capacities (what a body can do) and desires (what a body wants) are fairly self-explanatory, what’s brings a second degree of complexity to cities and settlements is human reflexivity in determining desires.

Drawn from Nietzsche’s will-to-power, desire is fundamental in establishing assemblages. Purcell (Citation2013) notes, ‘desire drives the process of becoming, of change, of transformation from one thing into another’ (Purcell, Citation2013). The point here is that these intersecting desires and capacities of different bodies, both human and non-human, generate a field of possibilities that guide the becoming of a settlement or a city. Since human desires can be reflexive and are more than instinctive dispositions, they can be contrary to past desires and therefore are fundamentally unpredictable, making cities not only complex but also ‘perplex’.

However, common-sense thinking uses ‘desire’ only as a synonym for ‘want’ or ‘need’. What distinguishes Deleuze’s concept of desire is the fact that, in his conception, desires are not singular needs in the abstract. As he outlines:

[we] speak abstractly about desire because [we] extract an object that’s presumed to be the object of desire. [We always desire] in an entire context, a context of our own life that we organize, we desire in relation with a landscape [my emphasis]. [We] never desire something all by itself, [we] don’t desire an aggregate either, [we] desire from within an aggregate. (Paraphrased from Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1988)

Therefore, the key to understanding desire is not a reduction into the instrumental notion of what is desired, but to trace the lines that form the landscape of desire (aggregate, in Deleuze’s term). For this paper, this is the third and final line of inquiry to investigate the settlement—Karail.

Karail: the protagonist

The paper uses empirical findings from my doctoral dissertation on Karail, the largest informal settlement in Dhaka—a burgeoning megacity where more than three-and-a-half million people live in such settlements (Swapan et al., Citation2017). Currently, Karail houses upwards of 300,000 dwellers in a diverse typology of housing options and a mix of functions, public open spaces and infrastructural adaptations (Bertuzzo, Citation2016). The only catch is that the settlement has been built on unused public land owned by a State agency. For this particular reason, Karail is often derided as a ‘slum’ in the mass media and popular narrative.

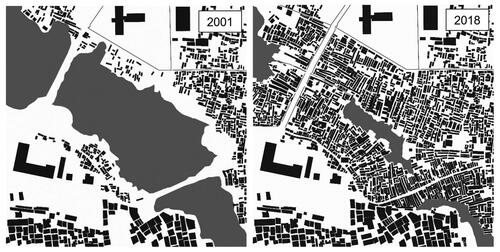

The stigma of being a ‘slum’ is an intangible part of housing condition in Karail and the residents currently face threats of eviction to allow the state to build a software industry park. Oscillating in-between the desire for a better life in the city and the fear of displacement, collectively the ‘slum dwellers’ have re-claimed a large lake to produce their housing—nothing short of a major urban transformation in the last twenty years. As noted in below, in 2001, the waterbody is largely vacant. By 2018, the settlement has grown inwards, producing not just the housing built form but also the land itself. Taking this production of housing as our point of departure, the pertinent questions to ask are: how had they done it? What were the assemblages underlying the production of this informal settlement?

Methodology

Karail was taken as a case study to allow for an understanding of the practices through abductive reasoning (Thomas, Citation2010). Since assemblages operate across the material and the social, the concomitant methodology required for this study was a mixed-method approach. In phase 1 of the fieldwork, the focus was on the spatial-material changes during the 2001–2018 urban transformation, which were investigated using on-site morphological mapping (Dovey & Ristic, Citation2017), archival analysis of Google Earth database spanning from 2001 to 2018, as well as participatory mapping involving the local community to track the transformation at multiple scales. The maps were analysed to identify patterns, repetitions and peculiarities of the urban change, which formed a forensic basis for the social inquiry in the second phase. The primary method of the ethnographic inquiry was using semi-structured conversations with relevant actors and focus group discussions with local organizations. The participants were chosen based on purposive and snowball sampling. They included local landlords, shop owners, elders, political club leaders, NGO workers, mosque imams, trader’s union members and renters. A second method used for the social inquiry was participant observation of certain local practices pertaining to the production of the settlement. They included landfilling practices for the encroachment of the waterbody and producing new land, construction practices, NGO meetings related to providing urban infrastructure services and informal tea-stall meetings of local elders and community gatekeepers. The entire on-site spatial mapping and social inquiry lasted for eight months during 2019.

The primary outcome of the socio-spatial inquiry were 94 morphological maps, 101 interviews and multiple volumes of field notes. These sources were used to generate a set of ‘closed vignettes’—empirical stories that provided detailed and theoretically-informed accounts of processes (Alvehus & Crevani, 2018, p. 11). The findings are organized into the three lines of inquiry developed in the conceptual framework.

Tendencies of entanglements

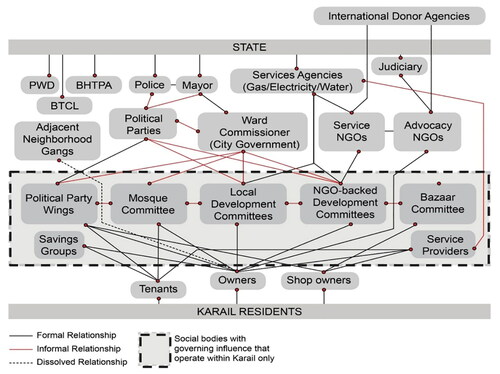

Therefore, the first task to analyse the entanglements in and around Karail was to map the multiple relations amongst the different social bodies (see diagram in below). These relations are not only external to the settlement but also extend inwards and are amongst the different bodies within it, which reveals a heterogeneous internal composition as well.

Beyond the bodies internal to the settlement, the diagram implicates immediate local actors outside of the settlement such as the different state and political bodies, NGOs and extra-state actors enabling and constraining how Karail works as a housing. However, the diagram fails to point out any qualitative difference between the different relationalities. To articulate further, I have identified four tendencies immanent within the entanglements—synergies, antagonisms, opportunisms and empathies.

Synergistic

Entanglements in which both bodies help to flourish each other, the most evident synergistic relations are perhaps the ones related to the local economy. Following structural adjustment of the 80 s, ready-made garments sector flourished in Bangladesh and multiple industrial clusters developed. Without provisions for housing in planning, a discernible pattern of informal settlements close to industrial clusters emerged. In the case of Karail, the synergy with the local industrial clusters within walking proximity is key to generating livelihoods and making it attractive as housing in the first place.

While this may be the most apparent relation, multiple minor practices enable Karail to be productive beyond servicing the adjacent neighbourhoods and labour jobs. A diversified recycling industry has developed in Karail that acts as a sponge, retaining all recyclable materials from a municipal garbage disposal site next to it. These are then collected by other industries within and outside, and curiously, most make their way back to China. Another synergy that sustains the livelihoods in Karail is the rickshaw industry. Unaccounted for in the formal planning, there is no place to store and maintain a million tricycles that clog Dhaka’s streets. Places like Karail have become the rickshaw housing as well, creating a small industry around it and fostering grassroots innovation. The first electric rickshaws in Dhaka—using old car batteries and wires recycled from the garbage dump—came from Karail’s rickshaw garages, and not imported from Tesla!

Antagonistic

Against the synergistic tendencies, a set of antagonistic ones manifests themselves in various guises. The most apparent ones are the collective effort of different governmental agencies to unhouses (read evict) the residents through formal means. Their primary method is using colonial-era laws and property rights to cast the residents as squatters and creating a narrative of ‘rescuing’ public lands from ‘encroachment of the mafia’. Legal instruments become the expressions used by the State, as Roy (Citation2011) had noted in India, to declare the settlement as undesirable and worthy of demolition. There have been multiple attempts so far in Karail (2002, 2012, 2017). However, what is crucial to note is that the State operates through other ‘informal’ means as well to carry out evictions, one of them being arson. This is speculative since no investigation of multiple fires has ever seen the light of day, but co-incidentally, ‘slum fires’ often are followed quickly by repossession of the land by the State. How convenient! In either case, the antagonism sits within a larger narrative of ‘slums’ as zones of criminality, drugs and filth, which endlessly circulates in the mainstream media. Cumulatively, the legal instruments and media narratives become the expression—acts of enunciations—that anoints the informal settlement as the ‘slum’ and in effect helps to legitimise the abrupt evictions and the consequent erasure of the everyday urbanism.

However, not all forms of antagonism are so insidious. Some are constitutive of the everyday life within the settlement, manifesting with a bodily presence instead of operating through expressions. One such case is the 3 m high wall that separates Karail from the city outside, constructed by the State agency (BTCL) with offices adjacent to Karail. Built perhaps to protect the land and to avoid the public gaze veering into ‘slum’ from the street, the antagonistic effect of the wall is the amputation of the laneways inside Karail from the city outside. The residents have negotiated by making holes through the wall, setting up markets along with it, building over it and in some cases, bribing the contractor hired by the State to leave gaps at strategic locations. Karail oozes out the through these holes and gaps, resembling more like a border with intense public activity rather than acting like a boundary built to restrain lives and livelihoods (Sennett, Citation2017).

It’s also important here to note the human/non-human entanglements can be equally viewed through this lens. The lake on which the residents expanded the settlement, instead of developing into a synergy, was the site of slow ecological death. The excessive landfilling blocked the natural stormwater system, causing waterlogging in the northern parts of the Dhaka. This also shows the multiplicative nature of entanglements that transcend particular scales.

Opportunistic

Between the more extreme tensions outlined so far, some tendencies are more ambiguous in practice—both exploitive and helpful in ensuring that the settlement flourishes. Like in many such settlements, an intricate relationship exists in Karail with the national political parties. Often termed as a ‘clientelist’ practice, there is a tendency for political leaders to accord legitimacy to an informal activity, squatting in this case, in exchange for votes. Curiously, the housing production in Karail peaked in 2015, right after the 2014 parliamentary elections. Local residents confirmed that the local community leaders, who simultaneously hold a position in the lowest rung of the national parties, became more emboldened after their party had won the election. This particular entanglement is concerned more about mutual reinforcement rather than exploitation.

A more fitting example of an opportunistic tendency is the major mode of housing finance in Karail. Although initially self-organised saving groups were operational, currently, the majority of housing is funded by NGOs running microfinance programmes, albeit informally. Leading the pack is BRAC Microfinance, subsidiary of the largest NGO in the world. Their factsheet from 2017 shows outstanding loans upward of BDT 25 million in Karail alone. Officially, their microfinance loan products are only for entrepreneurship. However, a large number of housing additions and upgrades can be attributed to loans from BRAC. From the focus group discussion with BRAC employees in Karail, it is clear that an informal financial mechanism has been invented with the help of local leaders. In addition to the genuine applicants for businesses, house owners get loans without one. These fake applications were often in the name of their wives since women entrepreneurs have a greater chance of getting the loan as part of the NGO’s women empowerment policies. These ‘informal’ loans are then diverted towards the housing market, expanding and densifying the houses, which then are rented out to pay the instalments. The crucial fact is that the interest rates of such loans are at 26% as opposed to the standard home loans of around 12% in the formal financial market, to which the residents have no access. One NGO worker commented, ‘there would be no new house without the extensive loan programs by us. We don’t care what they use it for as long as they can pay it’ (interview, 2019). What this exposes is an opportunistic tendency on part of the microfinance NGOs, discontents of which has been investigated by others (Karim, Citation2011; Mannan, Citation2015).

On part of the residents in Karail, practices such as siphoning off electricity, gas and water from the surrounding neighbourhoods show a similar exploitative tendency. In many cases, the employees of the service-provider agencies help set-up and maintain these arrangements, making an extra buck in the process. The informal arrangements allow for another level of opportunism within the settlement since there isn’t any equitable distribution system. Rather, those who are socially skilled and politically resourceful often take charge of the siphoning and distribution, effectively setting up one-man companies with exorbitant prices charged to the residents. Lack of options is a key parameter in ensuring the continuation of opportunistic tendencies.

Empathetic

In contrast, another set of tendencies are operational, in which the entanglements are marked by kindness and solidarity. Although the least visible, these practices are key to Karail’s resilience. The rapid reconstruction that followed a recent fire in 2017 that destroyed more than 5000 homes was largely possible due to collaborative solidarity between the State, NGOs and local communities. Additionally, the informal support network reached the small towns and villages from which the residents had migrated. In effect, the fire acted as an event that reframed the usual tendencies. The antagonist State and the opportunist NGOs retreated and instead provided both material and monetary support to build back better. Given the massive scale of help in reconstruction from the ‘top’ after the fire, one could ask whether Karail was still a ‘bottom-up’ settlement.

Similar empathetic tendencies can be particularly observed following eviction attempts, in particular by NGOs providing pro-bono legal support such as BLAST and ASK. Indeed, Karail’s major growth has occurred following the 2012 High Court rule against unlawful eviction by the State, which conferred a de facto tenure security. However, empathetic responses are not only episodic and external to the settlement. Informal support groups such as local mosque committees raising funds to build an elderly home, children being taken care by neighbours, local stores allowing borrowing without interest—such everyday empathies act as a cohesive agent for the settlement, forming a rich tapestry of social capital that is crucial in making Karail work as a convivial housing.

The argument here is simple, that how Karail works as housing is an outcome of the collective resonances and dissonances of these relational tendencies. To say that it works in a bottom-up way, would simply be reductive. Equally reductive would be to say that there are relationalities that maintain it. Rather, as we have seen, there is a temporal dynamics to these tendencies of entanglements and their different kinds allow for a more nuanced engagement on the ground, both in research and policy-making. We are forced to ask: which synergies and empathies are we helping to flourish, and which opportunisms and antagonisms are we overlooking in a given housing scenario?

The discussion so far has focused largely on external actors/factors and its entanglements with the settlement. Next, the second line of inquiry probes the organizing mechanisms underlying the urban production of the settlement itself.

Mechanisms of production

If one were to ask how Karail was produced, typical answers would range from the ‘unplanned’ to the ‘self-organised’ but that hardly explains anything. To begin unpacking the production mechanisms, it is helpful to re-visit the notion of ‘slum dwellers’. In terms of the composition, recent surveys have noted that about 20% of the population in Karail are owners (with de facto tenure) while roughly 80% are tenants. The materiality in Karail—the housing units, streets and public spaces—are largely produced by these owners since tenants have almost no involvement in the decision-making. Having traced both the oral and material histories of how the housing has emerged, I have identified three distinct organizing mechanisms—ad-hoc-ism, collectivism and monopolism—each with a different level of territorialisation. To illustrate the mechanisms empirically, I use ethnographic data from four different neighbourhoods within Karail.

Ad-hoc-ism

Ad-hoc-ism is a mode of production that is characterized by urgency and improvisation in the face of survival needs. It is marked by minimal coordination and planning between the dwellers in producing their housing units, resulting in individual acts of housing efforts. In Karail, most of the pioneer settlers—those who erected the first houses in the vacant public land—were not from the rural countryside but forced out by increasing rents from the surrounding formal neighbourhoods. Politically marginal, with little social or financial capital, they had used discarded materials to erect these first houses in spaces that attracted the least attention. There was no political agenda, no conscious exercise of the ‘right to the city’ present in their practices. If the vacant land is considered as a smooth space, they hardly ordered it for their occupation. They rather utilized pre-existing paths, edges, and suitable land to build. The owners themselves built most houses, comprising of just one or two rooms. The housing was temporary not only due to the financial condition of the dwellers, but most did not want to invest in a house with virtually no tenure security. The ad-hoc-ism is evident from mapping the earliest neighbourhoods in Karail with labyrinthine lanes that end abruptly, houses that don’t align, places where services are built post-facto with a minimal sense of collective decision-making. In these earlier neighbourhoods, the houses were built in a process of least-coordinated settling. They were built incrementally as temporary shelters without any community-based planning for future expansion or establishing a permanent settlement.

While most houses are indeed permanent by now, the pioneer settlers from one such settlement, Beltola, reminisced about their time in houses made by tarpaulin, strings and pieces of bamboo. Analogical to an economic life based on bare subsistence, ad-hoc-ism in Karail resulted in the stereotypical slum-like conditions of squalor. While it seems that this is the only mode of production in ‘slums’, the next two mechanisms prove otherwise.

Collectivised

Not all pioneer settlers acted ad-hoc. There were cases of producing housing in which a form of joint decision-making between many different dwellers can be traced, pointing towards different forms of collectivism. In one particular case, in the Boubazar neighbourhood, there was an overnight occupation of an unused stretch of land by 35 local renters. Even before dawn, the land was marked by bamboo poles and distributed equally amongst them—a paltry 6 by 6 feet for each family, but which nonetheless transformed them from renters to de-facto owners or ‘landholders’. It is crucial to note that this wasn’t a spur-of-the-moment decision or action. The month-long planning before this overnight operation mostly consisted of coaxing a form of legitimacy from the local party leaders to occupy the land and saving funds to build the house once the plan was executed.

In contrast to such synchronous collectivism, a more protracted, subtle and community-oriented form is the accretion of settlers in a neighbourhood over a longer period, which nonetheless follows a form of planning. In such cases, while the process of settling may be incremental, there is a form of collective decision-making between the earlier settlers and newer ones in distributing the land for housing. In the neighbourhood of Mosharof Bazar in Karail, the housing was settled over a long time, but usually, it was not an ad-hoc process, in the sense that one couldn’t simply move in and build a house. Rather, the local community leaders played a part in allocating land to the new arrivals using social norms to enforce informal planning regulations that ensured adequate access and public facilities. These practices can be framed as accretive collectivism.

Whether accretive or synchronous, common to both are certain key features—a form of community planning and anticipation of a longer stay, roughly equal distribution of plots, parity in de facto tenure rights, lack of strict hierarchy in decision-making and strong social norms guiding the settling process. These features can be seen as a successful case of commoning (Ostrom, Citation1990)—where the vacant land is seen as a common pool resource and is used equitably. The allocated plot sizes usually were larger than ad-hoc settlers, which allowed the landholders to build multiple rooms (5 to 10 rooms, on average), some of which were rented out for extra income. For many, this was housing-as-entrepreneurship to generate livelihood. Another crucial factor in the collectivising mechanism is the role of local institutions such as the mosques and bazaars. The everyday practices of meeting for prayers and trading allowed the formation of a neighbourhood-citizenship and a sense of collective intentionality (Searle, Citation1990).

Syndicated

In contrast to both ad-hoc and collective forms of urban production, a third mechanism is discernible in Karail’s emergence, particularly in recent years. In this mechanism, housing production and planning processes become centralised in the hands of a few particular actors with the highest financial and political capital. As opposed to the land or lake being treated as a common-pool resource, it is ‘enframed’ as a resource for monetizing in the form of housing. In its milder form, as seen along the lake edge in the western neighbourhood of Poshchimpara, a few of the ad-hoc settlers used the proximity to the lake as an opportunity to extend their houses for long stretches and reclaim the lake. Additional rooms in the extension were then rented out. In extreme cases, some houses are one room wide (10 feet) and reaching up to 250 feet in length with 25 rental rooms arranged sequentially. This form of extension into the lake by ‘lucky’ owners have meant a tripling of the housing production in the last 10 years and emergence of ‘super-landlords’ who owns upwards of 100 s of rooms. The planning to produce this housing no longer remained a communal matter but had become syndicated.

A more rapid and centralized form of syndication can be traced in the emergence of the northern neighbourhood of Satellite Poshchim. In this mechanism, certain local ‘leaders’ used their political capital to take hold of the entire lake edge adjacent to this neighbourhood. Instead of building rental housing, they reclaimed the lake in increments of roughly 4-rooms, developed a housing unit on the reclaimed land and then sold it on the local housing market internal to Karail, before repeating the process. These grabber-developers, while being local owners, usually don’t live in the housing they produce. Often they resort to coercive means, manipulation and violence to take control of the land/lake. Most decisions regarding the neighbourhood are planned by them usually to expand the profit margin. The accumulated capital helps these ‘developers’ to reach into the State apparatus, befriend police and politicians, and maintain the housing production line. What is produced is cookie-cutter units with minimal community involvement in the urban production process.

The three mechanisms can be framed as movements from a smooth to a striated space, in increasing levels of territorialisation. The initial growth in the form of ad-hocism (deterritorialized/discordant decision-making) allowed the initial temporary settlement to form, followed by more collective forms of production (meso-territoriality/distributed but organized decision-making). However, without any effective means to stop the escalation, or make the process stable, the housing production began to be syndicated by a few, essentially becoming a capitalist mode of production (become territorialised/centralized).

While the narrative here may portray a linear sequence with one evolving into the other, these mechanisms operate simultaneously in different degrees of mix in Karail. One could easily find a one-room housing unit built ad-hoc and barely existing in-between large rental clusters. Moreover, these mechanisms are in constant mutations, playing off each other, combining and abstracting from the logics of their procedures. In other words, they dynamically respond to the entanglements described earlier and in turn re-compose new relations. Karail is produced as a result of this flux. Rather than a singular organising process, these multiple mechanisms—each driven by a different desire—are in constant tension. The desire to temporarily survive in a city may lead to an ad-hoc organisation, which may mutate to a more collectivist mechanism when that desire shifts to long-term settlement, or it can become monopolistic in a desire for profiteering. However, desire is more than just individualistic ‘want’, the logic of which we unpack next.

Landscapes of desire

Perhaps it’s best to illustrate how desire operates by ethnographically elaborating one particular practice in Karail that is common in all three mechanisms and is fundamental to the local perception of adequate housing—the production of land.

While walking in Karail one morning, I noticed a rickshaw van loaded with cement bags parked at the entrance of a laneway too narrow to allow it through. The driver picked up a bag, went in and came back to take one more in. I followed him in. His journey ended directly into what looked like someone’s home. We went to the back of the house, where the wooden planks of the bedroom floor had been torn apart, revealing the lake on which it was built. The labourers dumped the cement bags into the water. Curiously, the bags weren’t full of cement, but rather building debris—chunks of plaster, bricks chips, concrete pieces—all seemingly gathered from a demolition site. The owner of the house was working there as well. I asked him what was going on.

The owner had been a renter for 5 years before finding a spot on the lake edge where he had built his home on stilts. But now, he wanted his house to be on land. So, he went ahead with filling up the lake under his house. I asked him what the process was and the specific materials used in the filling. ‘Oh, that is what we call ‘rubbish’—building demolition waste that is collected from the city outside. There are people here in the slum who we get in touch with when we have to do some ‘filling’—’the rubbish guys’ (interview, 2019). Once it reached somewhat close to the plinth of the house, he would use fresh sand to seal off the reclaimed land and patch up the floor.

While my first impulse was to look for an instrumental reason for such an endeavour, there seemed to be something more to this. Why was land produced post-facto, even when there was a lack of tenure security and it wasn’t needed for supporting the structure? Many water-based settlements across the world have houses on stilts for a long period without producing land. The pertinent question here was to ask not what the desire is, which is self-evident, but the larger narrative in which this desire has emerged.

A given-ness of the need to have land was evident during my conversations with the dwellers. Most people in Karail spoke of landfilling as a right, as ‘natural’. The desire to have land was unequivocal. I held an FGD in discussing the narrative of land and why it was so important. For the landless coming to Karail from the rural areas, the narrative of reclaiming land was an important one since a lot of them had lost not just material land but the ‘social ground’ that the land provided. To be landless conferred a low social status. The landholders in Karail were in a different class, but within them, those who had permanent land and concrete structures were higher in the ladder. And it is nothing essential to Karail. To own land is a particularly strong cultural drive in Bangladesh. Discussions in tea-stall in Karail are often about where to buy land—back home in the village or in the outskirts of Dhaka—if the state succeeds in evicting them. In such a narrative frame, rental housing on stilts is framed as inferior. Housing with a tree (confirming contact with the ground) is seen as better. Collectively, what this creates is a landscape of desire in which land is highly valued. The developers operating in Karail clearly responded to this desire. They have gone to extraordinary lengths to ensure that they fill the lake up before building the houses despite incurring higher-cost, and not just because of structural necessity. Bamboo stilt houses just would not sell.

This may seem like a detour but I think it is necessary to understand desire in the sense of how it operates within an assemblage of materialities and narratives, of physical objects and affects. The housing production is not driven by a singular logic, yet are not incoherently assembled. There is a multiplicity behind that simple operation of dumping a few bags of rubbish into the lake. People are not after just ‘shelter’ or ‘housing’ in the abstract but desire housing in an image pre-conditioned by the larger narrative. When the narrative changes, so do the desire. The largest changes in housing conditions in Karail has been only after significant reconfiguration of their landscape of desire.

A most evident example is the large-scale self-upgrading program in 2017, wherein a matter of months, thousands of owners retracted their front of the house to allow for the laneways to widen. Although many NGOs had previously attempted to pursue road widening programmes for decades, most failed due to the owners not negotiating. That changed in 2017 after the large fire mentioned earlier that had gutted thousands of homes, even in neighbourhoods that were unharmed by it. The event had shifted the narrative of what was acceptable as a housing condition. The landholders went through a collective reflection, forsaking the previous desire to cling on to even an inch of land. The self-widened roads were not because of a long-negotiated process done by the communicative planning work of external planner and architects. The event of a fire was more than the actual burning of the houses. It had an afterlife in the form of the linguistic expressions it received. It became part of the expressive aspect of Karail’s assemblage. The event impacted the narrative that went on in the tea-stalls where the men spent most of their evenings as it did in the internal courtyards where women gathered. Once the landscape slowly shifted, the self-widening of the road was only an aftereffect. In other words, the agency of events was in shaping the imaginaries of what constitutes as housing.

Karail, or cities for that matter, is complex precisely because the landscape of desire is not simply the sum of individual needs of humans. Humans are agentic but so are the non-humans. In a simple assemblage of producing land, the ‘fill-ability’ of the lake with rubbish is as much a constituent as is the ‘culturally constructed’ desire to have land. Indeed, the capacity of Karail’s land, in a prime location within the city, is the material (read morphological) condition generating a desire for the State to capitalize it. In the recent plans by the State to establish a software industry park replacing Karail, one can trace such a desire to be borne out of a ‘Global city/Smart city—development’ narrative. This desire, itself part of a larger narrative of Bangladesh becoming a ‘developed country’ can be traced further back to global structures of power—experts from IMF and World Bank armed with bar charts and stories of economic benefits of megaprojects circling in the corridors of the government ministries. Indeed, the exercise of hegemonic power is most effective when it silently shapes our landscape of desire.

Having traced these three lines of inquiry, it’s prudent to ask of their implications.

New ways to engage

While a singular case study perhaps is not enough to generalise, after the learnings from Karail in this paper, can we simply speak of such settlements as ‘self-organised’ or generated from the ‘bottom-up’? Can we speak any longer of housing policies, instruments, and plans without a concomitant understanding of the heterogeneity of the housing—assemblage? It is clear that there are no homogenous quintessential ‘slum dweller’ residing therein. However, such simplistic notions continue to be used in policy documents in Bangladesh. For example, while the segment on housing in Dhaka’s new masterplan for 2035 acknowledges such settlements being a major mode of housing production for low-income population (RAJUK, Citation2020, Section 4.2.1), it fails to acknowledge the differences within such settlements even as it promises everyone with equitable housing. There is no mention of how planning policy is to be differentiated based on the internal stratifications. The generalities and abstract notions of justice serve the planning documents well, it is hailed as one of the most progressive so far, but sadly in reality, housing policies continue to be made that is unable to serve the most vulnerable. It cannot see the difference in the world, precisely because there isn’t a vernacular with which to speak of them. This paper is therefore an intervention in that regard.

As mentioned earlier, Karail is slated to be developed as a high-tech software park. On paper, the ‘slum-dwellers’ have been promised compensation or a flat in the new development, but recent experiences show that the syndicates established in such settlements tend to control the distribution of any compensation (Shafique, Citation2021). Such promises of a middle-class dream of living in a high-rise flat destroy the collectivised organization processes as it lures many away from organized action and protests. The final outcome of such a formalization project creates a fresh cycle of ad-hoc housing production by the dwellers left out of the benefits in someplace else. Time and again, despite mountain of evidence against the negative impact of eviction and state-provided housing, settlements like Karail are under a constant fear of displacement and loss of livelihoods. As alluded to in the last section, the constructed desire for a so-called modern city forms a legitimizing narrative for such housing injustices to persist.

While the housing future for Karail may sound bleak, it would be a disservice not to mention the range of local activists, lawyers, architects, urban planners and community leaders who have been forming synergistic ties—’weird alliances’, to use a term from Lancione (Citation2020, p. 274). Such heterogenous alliances offer a glimmer of hope for an alternative housing future for Karail and other settlements as well. I am privileged as a researcher to be part of these ongoing collaborations to negate the antagonistic entanglements that are in the process of facilitating the eviction. Moreover, once we have learnt of the mechanisms of production at work, we are in the process of engaging selectively to bring back collectivist actions, subvert the existing syndication, and most importantly, create a dialogue between the most vulnerable within Karail and the state officials. This has been facilitated by establishing a new citizen-led initiative called Platform for Housing Justice (Najjyo Abashon Moncho, or NAM), convening which is part of my ongoing research with residents in Karail. The line between the researcher and the researched has become blurry since my early days there.

Fundamental to the ongoing work is a renewed understanding of how injustices happen within narratives created to shape public desire, say evictions that are accepted within the desire for smart city. Our work has now focused on re-shaping these fundamental desires and narratives that has taken hold in Bangladesh with regards to housing and is starting to take different forms. Alongside traditional research work, community gatherings, social media engagement and art events around housing issues are proving to be quite important in shaping the narrative. COVID-19 has normalised the use of virtual platforms for gathering, even with community leaders in such settlements. It has greatly facilitated our ongoing work to repel the planned eviction in Karail and re-imagine the narrative of housing futures in general. Working to challenge these narratives that benefit a neoliberal and authoritarian agenda at the expense of collective and equitable ways of being, to imagine alternative housing futures and to instil a sense of housing justice is perhaps a project of a lifetime. The analysis presented in this paper have been instrumental in these ongoing work and struggles, as it has given a vernacular to speak of realities without resorting to the entrenched and simplistic binaries.

It is hoped that one sees the intellectual work not as a binary opposite of being an ally of the struggles on the ground, but rather see the allyship as a source of insight and motivation to desire an alternative housing future. Ananya Roy’s recent work with the homeless and unhoused in Los Angeles provides us with such new imaginations of what scholarship can do (personal communication, 2019). Such notions of research justice are implied within the work of Deleuze since his primary desire was to re-think the traditional philosophy that is foundational to the colonial/capitalist/Leviathan project. Therefore, there is a call to action embedded within assemblage thinking for housing scholars to engage sideways beyond the academic ivory towers to find forms of grounded engagement, to be part of the struggle of the housing communities that we study with, to be the allies of the oppressed within the cracks that our studies reveal—and thereby remake the landscape of radical housing scholarship itself.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Arefi, M. & Kickert, C. (Eds.). (2019) The Palgrave handbook of bottom-up urbanism (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

- Beck, U. (2016) The metamorphosis of the world: How climate change is transforming our concept of the world (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons).

- Bertuzzo, E. T. (2016) The multifaceted social structure of an unrecognised neighborhood of Dhaka City: Experience from Karail Basti, in: M. Rahman (Ed) Dhaka: An urban reader, pp. 151–168 (Dhaka: UPL).

- Brenner, N., Madden, D. & Wachsmuth, D. (2011) Assemblage urbanism and the challenges of critical urban theory, City, 15, pp. 225–240.

- Buchanan, I. (2015) Assemblage theory and its discontents, Deleuze Studies, 11(3), pp. 382–392.

- Buchanan, I. (2017) Assemblage theory, or, the future of an illusion, Deleuze Studies, 11, pp. 457–474.

- DeLanda, M. (2016) Assemblage theory (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press).

- Deleuze, G. (1994) Difference and repetition (New York: Columbia University Press).

- Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (1988) A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia (London: Bloomsbury Publishing).

- Deleuze, G. & Parnet, C. (2007) Dialogues II (New York: Columbia University Press).

- Dovey, K. (2016) Urban design thinking: A conceptual toolkit (New York: Bloomsbury Academic).

- Dovey, K. & Ristic, M. (2017) Mapping urban assemblages: The production of spatial knowledge, Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 10, pp. 15–28.

- Dovey, K., Shafique, T., van Oostrum, M. & Chatterjee, I. (2021) Informal settlement is not a euphemism for ‘slum’: What’s at stake beyond the language?, International Development Planning Review, 43, pp. 1–12.

- Hernández-García, J. & Hernández-García, I. (2021) Smart and informal? Self-organization and everyday, in A. Aurigi & N. Odendaal (Eds), Shaping smart for better cities, pp. 307–319 (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press).

- Holubec, P. (2014) Assemblage thinking in urban studies: how to conceive of a city?, In Advanced Engineering Forum, Vol. 12, pp. 17–22. (Trans Tech Publications Ltd.).

- Ivakhiv, A. (2014) Beatnik brothers? Between Graham Harman and the Deleuzo-Whiteheadian axis, Parrhesia, 19, pp. 65–78.

- Kamalipour, H. (2016) Urban morphologies in informal settlements: A case study, Contour Journal, 1, pp. 1–10.

- Karim, L. (2011) Microfinance and its discontents: Women in debt in Bangladesh (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press).

- Koster, M. (2015) Citizenship agendas, urban governance and social housing in The Netherlands: An assemblage approach, Citizenship Studies, 19, pp. 214–228.

- Lancione, M. (2020) Radical housing: On the politics of dwelling as difference, International Journal of Housing Policy, 20, pp. 273–289.

- Lea, T. (2015) What has water got to do with it? Indigenous public housing and Australian settler-colonial relations, Settler Colonial Studies, 5, pp. 375–386.

- Maalsen, S. (2020) Revising the smart home as assemblage, Housing Studies, 35, pp. 1534–1549.

- Mannan, M. (2015) BRAC, global policy language, and women in Bangladesh: Transformation and manipulation (Albany NY: SUNY Press).

- McFarlane, C. & Anderson, B. (2011) Thinking with Assemblage, Area, 43, pp. 162–164.

- Nail, T. (2017) What is an Assemblage?, SubStance, 46, pp. 21–37.

- Ostrom, E. (1990) Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

- Paddison, R., Philo, C., Routledge, P. & Sharp, J. (1999) Entanglements of Power: Geographies of Domination/Resistance, pp. 320 (London: Routledge).

- Purcell, M. (2013) A new land: Deleuze and Guattari and planning, Planning Theory & Practice, 14, pp. 20–38.

- RAJUK. (2020) Dhaka draft detail area plan 2015–2035 (Dhaka: RAJUK)

- Roy, A. (2011) Slumdog cities: Rethinking subaltern urbanism, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 35, pp. 223–238.

- Searle, J. R. (1990) Collective intentions and actions, In P. R. Cohen, J. Morgan & M. Pollack (Eds) Intentions in Communication, pp. 401.

- Sennett, R. (2017) The open city, in: The post-urban world, pp. 97–106 (New York: Routledge).

- Shafique, T. (2021, August 24) What sort of ‘development’ has no place for a billion slum dwellers? The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/what-sort-of-development-has-no-place-for-a-billion-slum-dwellers-120600.

- Simone, A. (2016) City of potentialities: An introduction, Theory, Culture & Society, 33, pp. 5–29.

- St. Pierre, E. A. (2016) The empirical and the new empiricisms, Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, 16, pp. 111–124.

- Storper, M. & Scott, A. (2016) Current debates in urban theory: A critical assessment, Urban Studies, 53, pp. 1114–1136.

- Streule, M., Karaman, O., Sawyer, L. & Schmid, C. (2020) Popular urbanization: Conceptualizing urbanization processes beyond informality, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 44, pp. 652–672.

- Suhartini, N. & Jones, P. (2020) Better understanding self-organizing cities: A typology of order and rules in informal settlements, Journal of Regional and City Planning, 31, pp. 237–263.

- Swapan, S. M. Z., Atiq, U., Ahsan, T. & Ahmed, F. (2017) Transforming urban dichotomies and challenges of South Asian megacities: Rethinking sustainable growth of Dhaka, Bangladesh, Urban Science, 1, pp. 31.

- Thomas, G. (2010) Doing case study: Abduction not induction, phronesis not theory, Qualitative Inquiry, 16, pp. 575–582.

- Thrift, N. (2008) Non-representational theory: Space, politics, affect (London: Routledge).

- UN-Habitat (2016) World Cities Report 2016: urbanization and development: emerging futures. (Nairobi: UN-Habitat).