Abstract

Based on an analysis of 31,909 listings on SpareRoom.co.uk – the self-proclaimed “#1 Flatshare site in the UK” – this paper makes two arguments. First, that housing benefit recipients are systemically excluded from listings on online flat-sharing websites through the construction of the “professional” prospective tenant. The UK’s much derided “No DSS” has evolved into a “professionals only” proxy. This is not confined solely to landlords and agents posting on the platform – it is also reflected by sitting tenants advertising spare rooms. Second, that the design of the SpareRoom.co.uk platform exacerbates this exclusion by facilitating the use of this “professional” construction. Through the design of inputs and built-in classifications within the platform, users posting listings are prompted to select from a finite list of housemate preferences, which in turn increases the number of listings adopting exclusionary practices. These findings have implications for research on low-income renters, “generation rent” and the role of online renting platforms.

1. Introduction

This paper has two agendas. The first is to examine the barriers recipients of housing benefit face when finding property to rent. Often billed in the UK as “No DSS” – a reference to the long defunct Department for Social Security – lettings agents and private landlords have been found to exclude applications from prospective renters in receipt of housing benefit (O’Leary & Simcock, Citation2020; Watts & Stephenson, Citation2017). This is far from a problem confined to the UK, with research in Belgium, France, Switzerland, Australia, the United States, Ireland and Germany (Bonnet & Pollard, Citation2021; Clarke & Oxley, Citation2017; Maalsen et al., Citation2021; Verstraete & Moris, Citation2019) – to name but a few – identifying similar barriers to the PRS for renters receiving state support for their housing costs. Current research in this area, and associated legal action, focuses on the practices of lettings agents or the operation of blanket policies by landlords – it is concerned with the physical or online equivalent of the lettings agent’s window. Such exclusionary practices, characterised as “queuing” techniques (Preece et al., Citation2020) have been interrogated in research into low income renters and “generation rent” (Hoolachan et al., Citation2017; Watt, Citation2020). This paper explores whether similar practices are found on online “flat share” platforms, where renters themselves and live-in landlords also advertise vacant rooms.

The paper’s second agenda is to analyse the role of online platforms themselves in excluding individuals from rental markets. Notwithstanding their dominance in the property search process, these websites are not passive platforms. By determining and shaping the inputs, pre-determined categories and blank boxes filled out by an advertiser, these websites configure the content of room listings and in turn their perceived or actual availability to prospective renters. This is part of what Fields and Rogers characterise as “platform logic”: how the technology these companies adopt facilitates interaction between their users and is active in “shaping markets and market interactions” (Fields & Rogers, Citation2021, p. 78).

Based on an analysis of 31,909 advertisements for properties in England on SpareRoom.co.uk – the self-proclaimed “#1 Flatshare site in the UK” (Blandy, Citation2018, p. 32) – this paper makes two arguments cutting across these two agendas. First, housing benefit recipients are systemically excluded from listings on flat share websites through the construction of the “professional” prospective tenant. Second, that the design of the SpareRoom.co.uk platform exaserbates this exclusion by facilitating the use of this “professional” construction through its housemate preferences function. The argument is in four parts. Part One outlines current research on the exclusion of housing benefit recipients from rental markets. Part Two focuses on the role of online rental listings and flat share platforms. Part Three provides an overview of the methods underpinning this study. Part Four details the findings, focusing in particular on the means by which this exclusion occurs: the construct of the “professional” prospective occupier. The paper concludes by drawing together the implications of this argument for research into the exclusion of low-income renters from the PRS and so-called “Generation Rent” more broadly.

2. “No DSS”: the systematic exclusion of housing benefit recipients from private renting

The perfect storm facing low-income renters seeking property in the United Kingdom is part of the broader story of PRS sector growth in what housing scholars considered to be “classic homeowner” societies (Bryne, Citation2020, p. 743). Echoing arguments made across the literature, Bryne argues that a potent mix of “deregulation”, “residualization” and “financialization” of housing in Ireland, Spain and the UK has undermined access to homeownership and catalysed a growth in the PRS from the 1980s onwards (Bryne, Citation2020). Morris et al.’s “Back to the Future” framing of the growth of the PRS in Australia underscores how policy decisions – particularly tax arrangements encouraging investment in rental housing, closing down access to public housing, and increasing affordability barriers to home ownership – have swung the Australian housing market back to a growing, increasingly overburdened PRS (Morris et al., Citation2021, pp. 1–23). This is a shared experience across many Western countries that have spent decades crafting heavily financialised “homeowning” societies. In their analysis of the PRS in the Netherlands, Aalbers et al. identify similar patterns in the growth of the Buy-to-Let market and the interaction between national housing policies and global economic and monetary developments (Aalbers et al., Citation2021), that characterise analyses of PRS growth elsewhere (see, for instance, Beswick et al., Citation2016).

An expanding and increasingly unaffordable PRS – especially at the expense of social housing provision – brings with it significant demands on support for housing costs for renters on low incomes (Clair, Citation2021). This leads to a two key problems facing low-income renters in the UK. First, relatively low levels of housing benefit render most properties unaffordable. In the UK, housing benefit for private renters is paid as an ex ante maximum allowance, pegged to Local Housing Allowance (LHA) rates across large Broad Rental Market areas. Indeed, linking allowances to larger geographical regions (as opposed to individual local authority areas) was a core aim of the policy, intended to flatten out allowances and encourage individuals to move to less expensive properties, leading to very significant discrepancies between LHA and (in many areas) actual rents (Powell, Citation2015, pp. 337–338). Although initially tied to median rents, LHA was subject to a series of cuts and freezes from 2010. Rates were frozen at the 30th percentile in 2012-13 and held at this level, with some modest uprating prior to 2016, until 2020. Faced with a woefully deficient allowance, households faced significant affordability challenges. For small families, LHA rates in 25 per cent of the country left them with a shortfall between housing benefit and rent of over £100 per month to service (Shelter, Citation2017), and the National Housing Federation estimated that 9 in 10 properties within the private rented sector (PRS) were unaffordable to recipients of LHA in 2019 (National Housing Federation, Citation2019). These problems have a keen geographical edge, with different and more acute challenges facing low-income renters in “hot” housing markets where competition and costs are high, compared to lower rent areas (McKee et al., Citation2017, p. 331).

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, LHA rates were increased to the 30th percentile of rents in April 2020 (Harris et al., Citation2020, p. 60), improving access to support significantly. However, the Government has defaulted back to the squeeze and freeze approach, with the Spending Review holding rates flat for 2021/2022 (under the Rent Officers (Housing Benefit and Universal Credit Functions) (Modification) Order 2020 (SI 2020/1519)). Assuming this policy persists, this simply “resets the clock” on increasing differentials between rents and LHA rates over time (Institute for Fiscal Studies, Citation2020). As cautioned by the Resolution Foundation, allowing LHA to “become unmoored again” from rent levels would have particularly acute effects in areas with where rental costs have grown faster, such as London, Cambridge, Glasgow, Bristol and Manchester (Brewer et al., Citation2020). Indeed, the Institute for Fiscal Studies calls on the Government to “avoid such a disconnection” by “re-linking LHA rates to current local rents and maintaining this link going forward” (Institute for Fiscal Studies, Citation2020). For our purposes, it is sufficient to note that housing benefit rates by design are focused on limited affordability across large broad rental market areas and - particularly between 2016 and 2020 - have fallen significantly short of actual hosting costs.

The second element of this perfect storm is pressure on the PRS. These relatively low levels of housing benefit support need to be considered in the context of an expanding and (in some areas) oversubscribed PRS which is short of affordable accommodation. The numbers renting in the UK have more than doubled from 8% in the mid-1990s to nearly 20% two decades later (Joyce et al., Citation2017; Marsh & Gibb, Citation2019). 25 to 34 year olds have felt this rise disproportionately, where the increase over the same period was from 12% to 37% (Joyce et al., Citation2017). This is coupled with significant churn within the sector, with 532,000 households moving from one PRS property to another in 2007, increasing to 860,000 in 2017 (Christiansen & Lewis, Citation2019). The swelling burden shouldered by the PRS suffers from a fundamental problem of supply and demand. There is, as Preece et al. put it, “a shortage in the supply of decent, affordable secure housing at a time of rising demand”, made worse by the state assuming a decreasing role in the direct provision of housing assistance (Preece et al., Citation2020). There is not enough affordable housing – or in some areas, enough housing of any type – to go around.

These changes to the demographic composition of the PRS and increasing pressures on the sector have led McKee et al. to describe the phenomenon of “generation rent”: a term capturing the increasing time spent by both young people and increasingly other demographics (such as families with children) renting, who would prefer to own their homes but cannot afford to buy property (Hoolachan et al., Citation2017; McKee et al., Citation2020). Research examining the experience of “generation rent” has found that a lack of security in the sector, compounded by a lack of protection from no-fault eviction, are a major source of anxiety and stress (McKee & Soaita, Citation2018). The increasing prevalence of shared accommodation – perhaps in-part catalysed by the expansion of the “shared room” rate in LHA from under 25 s to under 35 s (O’Leary & Simcock, Citation2020, pp. 2–3) – can exaserbate problems experienced by tenants who are forced, for affordability reasons, to share accommodation against their preference (McKee et al., Citation2020; Ortega-Alcázar & Wilkinson, Citation2021).

These two core dynamics – limited support for private renters via the social security system and increasing pressure on the PRS – create room for landlords and/or their agents to exercise discretion over their prospective tenants in high-demand areas. Put simply, it is a seller’s market. This imbalance of power has a significant impact on prospective tenants searching for property. Writing about the Irish private rented sector, Bryne and McArdle underscore how this “power asymmetry” between tenants and landlords impacts on the letting process (Bryne & McArdle, Citation2020). Their tenant participants “described themselves as ‘literally begging’ to be offered the tenancy” (Bryne & McArdle, Citation2020, p. 12). Preece et al.’s work on housing exclusion in the UK draws this same link between pressures on the PRS sector and what they describe as “techniques and practices” by landlords to decrease their perceived exposure to risk and maximise their financial return (Preece et al., Citation2020). Of particular interest for our purposes is their description of “queuing” techniques, where landlords or their agents “advertise opportunities, manage applications and determine eligibility” in a way that best ensures their return on investment (ibid).

It is these “queuing” techniques, broadly conceived, that have a particularly acute impact on recipients of housing benefit seeking accommodation in the PRS. Previous research has underscored the prevalence of “No DSS” policies in both public-facing property listings and in the internal working practices of lettings agents (such as tenant screening). Participants in McKee et al.’s study were “dispirited at adverts” which would frequently specify “no DSS”; a frustration mirrored in Watt’s work, where participants lamented “most of them” landlords “saying ‘no DSS’” (Watt, Citation2020). Work with landlords themselves has demonstrated a reluctance to rent to households on housing benefit, due to concerns that they are a “risky” proposition, due to lower income levels and, as Hoolachan et al. argue, because of longstanding negative stereotyping (Hoolachan et al., Citation2017). These findings are supported by O’Leary and Simcock’s recent review of the existing literature, highlighting that twice as many landlords were unwilling to let to housing benefit recipients because of their negative perception of potential problems that could arise (for instance, with the payment of Universal Credit), compared to those who had experienced problems first-hand (O’Leary & Simcock, Citation2020). Evidence from CentrePoint suggests the percentage of landlords willing to accept tenants in receipt of benefits fell from 40% 2011 to just 17% by 2017 (Centre Point, Citation2019). Shelter’s submission to the Work and Pensions Committee 2019 inquiry, No DSS: discrimination against benefit claimants in the housing sector, outlines the extent of the problem:

In our experience of working with those struggling with bad housing and homelessness, ‘no DSS’ policies and practices are both the most reported problem our clients face, and the most difficult problem for our support services to tackle (Work & Pensions Committee, Citation2019a).

3. The role of the SpareRoom.co.uk platform

Private renting has evolved dramatically from the days of “No DSS signs in windows” (Layard, Citation2018, p. 446). Online property listings – either on bespoke websites built for the purpose (such as RightMove or Zoopla in the UK) or bigger platforms, carrying rooms for rent alongside other small advertisements (as is more common in the US, on websites such as Craiglist and Gumtree), now dominate the process of finding property to rent in the UK. It is big business. In information released to its shareholders, RightMove notes it earns an average of £1,088 per month from an average advertiser, reflecting the high presence of lettings agents posting their advertisements routinely on the platform: a total of 16,347 agency companies in 2019. Some researchers (particularly in the US) have argued that these platforms are so dominant that they form an integral part of analysing access to rental markets, particularly in urban areas (Boeing et al., Citation2020, Citation2021).

SpareRoom, the focus of this study, descends from a different lineage to the UK’s other two largest rent listings websites, Rightmove and Zoopla. As the name implies, the platform’s target market were those seeking to “rent” (or perhaps in reality, licence) occupation of their property’s spare room, or to help match potential housemates together where a tenant leaves a joint-tenancy and a spare room is available. Indeed, a survey by SpareRoom in 2015 demonstrated that 45% of live-in landlords posting advertisements on the platform could not afford to pay their mortgage without a lodger (Blandy, Citation2018).

Its roots therefore therefore lie, as Blandy argues, in the “sharing economy” – a potentially precarious form of housing consumption, driven by a lack of availability and affordability, particularly in areas with high housing costs. This is a problem Blandy refers to as “enforced sharing”, highlighting the increased numbers of advertisements seeking to share twin or even triple rooms, especially in London (ibid, 31). Indeed, Harris and Nowicki underscore the central role websites like SpareRoom, Gumtree and Craigslist play for churn within Houses in Multiple Occupation: a legal term for properties with more than one household sharing common areas (Harris & Nowicki, Citation2020). This is far from confined to younger generations. Maalsen underscores how users of SpareRoom aged between 35 and 44 increased by 186% between 2009 and 2014, and by 300% for those aged 45–54 (Maalsen, Citation2020, pp. 108–109).

These sharing-led websites often offer services to both those renting space in accommodation and those seeking a room. The former by posting adverts of properties for rent and the latter by posting “room wanted” requests. Much current analysis focuses on the way in which prospective landlords or renters/lodgers frame these requests (for example, the way in which a prospective lodger attempts to make themselves appealing to a sitting or landlord, or vice versa). Drawing on an analysis of user profiles on an Australian flat share website, Maalsen and Gurran have argued that prospective renters attempt to make themselves more appealing by underscoring desirable qualities – particularly their busy lives and resulting lack of time spent at the property itself (Maalsen & Gurran, Citation2021). This leads to them to argue that these matching platforms for online property search “actively shape user profiles and performances” which in turn influence their housing outcomes (ibid). This practice of presenting oneself as an “ideal tenant” has also been explored in offline contexts (McKee et al., Citation2020, p. 1480). However the majority of activity and churn on these platforms is vacancy-led: an advert for a vacant property or room is posted, to which responses are invited.

The leading renting platforms in the UK therefore (mostly) carry familiar lettings agent advertisements, alongside those of sitting tenants, live-in landlords, and small-scale private landlords. An analysis of postings on SpareRoom therefore offers an insight into how these different stakeholders in the PRS differ (or not) from each other in their efforts to secure prospective tenants. Are the “queuing” practices ascribed to lettings agents also reflected in listings posted by live-in landlords, sitting tenants and landlords not engaging the services of a lettings agent? If pressures to share accommodation are sometimes financial in nature, are advertisements listed by live-in landlords or sitting tenants more accommodating of those in receipt of housing benefit than those listed by lettings agents or live-out landlords? As the leading platform entertaining listings from across these stakeholders, SpareRoom provides a unique opportunity (at least as far as the UK is concerned) to explore these questions.

The other core difference from the lettings agent window is that the platform itself plays its own role. Manging the interactions between users – both the advert posters and those seeking properties – forms part of what Fields and Rogers describe as “platform logic” (Fields & Rogers, Citation2021, p. 78). Their core insight is that platforms like SpareRoom are not passive entities; they actively shape interactions between users and in turn the market itself (ibid). For our purposes, Fields and Rogers underscore the importance of “standardization and classification” processes within these platforms, where users self-classify themselves or others in order to manage data input into the system to facilitate the ordering of content (such as search results or suggested listings) and the analysis of data necessary to sustain the platform (ibid, 79). To illustrate their point, they use the example of RentBerry – an international renting platform:

… the “fields” a prospective tenant might fill out to create their application on RentBerry (and similar platforms such as Biddwell, based in Canada) underpin the ability to profile the “recommended tenant”, or to offer “intelligent predictive pairing” of tenants and listings (ibid, 79).

Landlords and agents can’t list their rooms as unavailable to housing benefit claimants on property sites any more. Changing the way rooms are advertised is the first step, but changing perceptions and behaviour will take longer. That’s something we’ll be working on over the coming months but it does mean, for now, you may still find landlords who will decide not to rent to you if you receive housing benefit, but they won’t be able to say so in their ads (SpareRoom, Citation2020).

4. Method

This study adopted a webscraping method, using data mining software to pull property listings from SpareRoom.co.uk. This is an increasingly common method in the content analysis of property listings. Perhaps most notably, Boeing and Waddell’s large-scale scraping of Craiglist property advertisements has informed analyses of rental market activity in US cities, inequalities in access to the PRS, affordability, asking rents, and correlation with neighboured socio-demographics (Boeing, Citation2020; Boeing et al., Citation2020, Citation2021; Boeing & Waddell, Citation2017). AirBnB – a “holiday rentals” platform with a significant presence in many large cities across the world – has been a prime target for webscraping researchers. Indeed, “Inside AirBnB” is an open-access dataset of scraped listings and reviews on the AirBnB platform that is widely used by researchers, notwithstanding criticisms of its accuracy (Alsudais, Citation2021). Jiao and Bai’s work is illustrative of the method widely adopted: pulling off listings from the platform, followed by a content analysis drawing on location and other advert data (Jiao & Bai, Citation2020). More recently in this journal, Simock has used webscraped AirBnB listings to make a convincing case that privately rented properties have increasingly been converted into tourist accommodation, especially in London (Simcock, Citation2021).

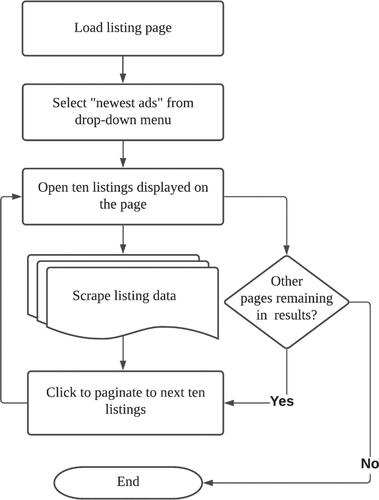

There are three main stages to a web-scraping method of this kind. Designing the web crawler, cleaning the collected data, and then content analysis of the listings. For this study, a web crawler was set up to access ninety-eight listing pages on the SpareRoom website – each tied to a particular English city or region. Within these listing pages, up to 1,000 results are displayed, separated into individual pages of ten (to go beyond 1,000 results, the user is prompted to refine their search term). The web-crawler’s design is detailed in . In summary, the crawler loaded the listing page, opened each advertisement, scaped the data, then did the same for all remaining pages until it could go no further (i.e. it hit the 1,000 result maximum or ran out of pages to scrape).

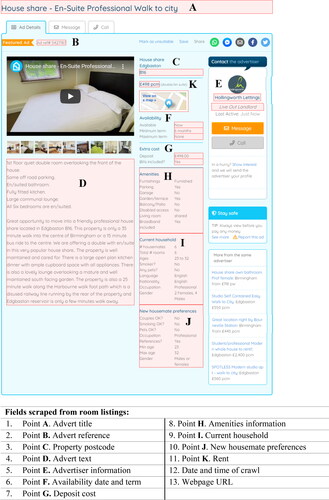

A total of thirteen fields were captured from each of the individual listing pages. These are detailed in below, using an example listing as a reference point. Although all SpareRoom pages share a common template, for a small minority of data in the sample (105 entries) at least one field was blank. The crawler ran on 28th May 2021, taking 6 hours and 22 minutes to mine 31,909 listings after duplicates were removed.

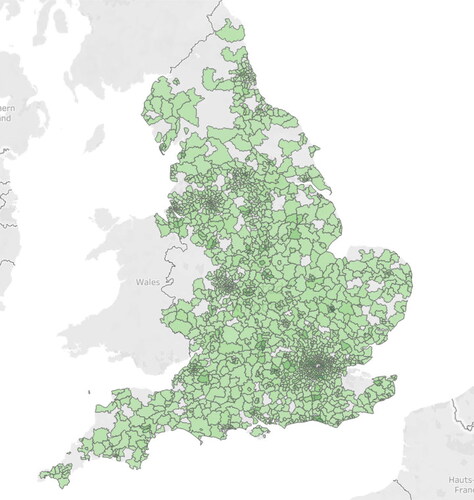

Geographically, the adverts cover a wide range of locations, including 68% of English outward postcode areas (e.g. "RH1", "RH10", etc) and almost all English BRMAs. details the spread of listings across the sample.

Figure 3. Map of listings in the sample by postcode. Interactive version available at: https://tinyurl.com/4tbnfbyn.

To analyse the data, duplicate entries were removed and the advert text (at Point D above) was added to NVivo for content analysis. The rest of the data were analysed in Excel. Before proceeding to the analysis, it is important to note some of the internal classifications within the SpareRoom platform. As a poster of an advert, you are prompted to select from one of six categories to describe yourself: agent, live-out landlord, live-in landlord, current flatmate, former flatmate and current tenant. Although the first three fulfil a landlord function of some kind, the latter three instead tend to reflect advertisements where someone has left a HMO rented via a joint tenancy, and the housemates are seeking a replacement tenant (in the case of the “former flatmate”, a replacement for themselves). There was significant variation across the sample in the numbers of these different users, with “current tenants” in particular being an option rarely chosen by those posting adverts. This spread is detailed in .

Table 1. Categories of users posting adverts within the sample.

Having provided an overview of the data collection, the next section turns to the analysis.

5. The “professional” proxy: a modern “no DSS”

It is nothing new for property advertisements to detail all kinds of inclusion and exclusion criteria to narrow the pool of prospective applicants. Specific requirements (for example, “salary must be at least 2.5 times the rent”) or exclusions of whole classes (for example, “no students” or “no couples”) communicate to the prospective tenant their own desirability, or lack thereof, to the advertising landlord. Although the exclusion of benefit recipients can take the indirect form of detailing salary requirements and so on, advertisements often adopt a more direct approach. As detailed above, the phrase subject to the most enduring criticism is “No DSS” – standing for “no Department for Social Security”, a long defunct predecessor of the Department for Work & Pensions. In qualitative studies of private renting on low incomes, participants have referred to being “dispirited” at the prevalence of “No DSS” adverts when searching for property (McKee et al., Citation2020). As one advice sector worker put it to Hoolachan et al.: “all the two and three bedroom properties within a 20-mile radius have got all, saying in their adverts ‘No DSS’, or essentially nobody on housing benefit…” (Hoolachan et al., Citation2017). In the wake of the real-term reductions to Local Housing Allowance detailed above, Rugg and Rhodes suggest that the adoption of such a “blanket NO DSS policy” is more widespread than ever before (Rugg & Rhodes, Citation2018, p. 57).

Targeting this direct exclusion was the core focus of the eponymous Work and Pensions Committee inquiry, No DSS: discrimination against benefit claimants in the housing sector. An exchange between committee member Chris Stephens MP and Helen Buck, the executive director of the lettings agency YourMove, illustrates this well:

Chris Stephens: Both your organisations have advertisements that contain the phrase “No DSS”. Do you consider that to be legal or illegal?

Helen Buck: We don’t have any adverts that say “No DSS”.

Chris Stephens: It is interesting that you say that, Helen, because Shelter provided us with some adverts from March 2019 that say “No DSS”: a bedroom property to rent in Essex—no DSS; a property to rent in west Yorkshire—no DSS; a property to rent in Romford—no DSS; and my favourite one, a one-bedroom property to rent in Telford: “Sorry no DSS. Small dogs considered.” Presumably the small dog has to provide some form of proof of income.

Helen Buck: They are shocking.

Chris Stephens: That is just a Google search, Helen, from Your Move, in March 2019, so do you consider adverts like that to be legal or illegal?

Helen Buck: Those adverts are not acceptable and I will need to go back and make sure that they are not appearing. We certainly have a policy of not having “No DSS” adverts… (Work and Pensions Committee, Citation2019b).

On letting agents saying “No DSS”, they are dressing it up now by saying, “Working professionals only” or “People who are working only”. My daughter is a carer for my Mum. In my opinion, she does a really good job. My Mum is 92 and she has to care for her and she also helps me. I’m finding it very frustrating because, when I ring them up, I just get, “No DSS. No, we’re not interested. We are not going to let out to DSS” (Work and Pensions Committee, Citation2019b).

5.1. Professionals only: housing preferences and advert text

On the SpareRoom platform, there are three ways that listing posters can express this preference for professionals: (i) through SpareRoom’s built-in housing preferences function (on which more below), (ii) by saying so in the free-form advert text, or (iii) doing both. Within the sample, 17,111 adverts do one of these: 5,969 specify “professional” in the housemate preferences function but not the advert text; 5,591 do so in the advert text, but not in the housemate preferences; and 6,151 do so in both.

This construction of the “professional” is important when considering the role of the SpareRoom website itself, as these platforms often utilise classes of persons as search parameters, allowing users – both the landlords posting the advertisements and those searching for a home – to navigate postings with reference to pre-determined exclusion criteria and requires those posting adverts to engage with them. Power’s analysis of the difficulties faced by those renting with pets in Sydney illustrates this well. The website in her study used a “pet-friendly filter” to help distinguish between those landlords willing to let to tenants with pets or not. When activated, “only just over 2% of properties advertised tagged themselves as being available to those with pets” (Power, Citation2017, p. 348).

When a user posts a property listing on SpareRoom, the form prompts them to select a preferred “occupation” for a prospective tenant. As far as the SpareRoom platform is concerned, there are two categories of person: “professional” and “student”. Everyone else exists under “no preference”. In neither the form itself, public facing webpages, information on user accounts, or in the accompanying “info & advice” pages do SpareRoom define what is meant by “professional”. The term is not included in its “glossary of terms” (SpareRoom, Citation2021). Of the adverts in the sample, 12,120 chose “professionals” from this housemate preferences box, 1,591 chose “students”, and the rest (a total of 18,144) expressed no preference. A breakdown of these is provided in .

Table 2. Breakdown of listings detailing and not-detailing “professional” in housemate preferences.

The results demonstrate that adverts specifying “professionals” in housemate preferences are present across all advert poster types – they are not confined to agents and landlords. Although live-out and live-in landlords are those most likely to express a preference for “professionals” in the housemate preferences box (45% of their listings did so), current flatmates are more likely to do so than agents (38% to 32% of listings), and it remains a significant proportion of listings from current tenants (30%). Former flatmates are by far the least likely to specify a preference for professionals, with just 19% of their listings doing so.

These data need to be read alongside the content of the advert text –the other principle route for expressing a preference for professionals only. The listing adverts contain a huge variety of details, ranging from information about the property, its current tenants, application processes, local amenities and information about the advert poster (especially if they are a lettings agent, where information about the company may be provided). References to the word “professional” therefore arise in a range of contexts. Advert posters often describe themselves as professional, such as “Considerate Professional Landlord with 16 Year’s Experience Letting own properties”. Adverts also sometimes specify that the services of a professional cleaner have been contracted as part of the advertised rent, such as “professional cleaning service every week for common areas”. However, the term is also used in much the same way as the housemate preferences box: to express a preference for particular kinds of prospective tenant to apply.

These take one of three forms. The first state that applicants should be “professional”, sometimes tied to required employment, or other characteristics (such as being respectful, tidy, responsible, etc). The phrase “working professional” appears in 2,163 results in the sample, “young professional” in 1,567, and “single professional” in 337 – as opposed to “No DSS” in only 80. Examples include:

“Ideally we are looking for a mature and responsible professional, preferably full time employed.”

“OUR PREFERRED TYPE OF TENANT IS A PROFESSIONAL, KIND, RESPECTFUL AND WORKING”

“All new applicants must be working professionals who are able to pass our vetting. We don’t take any DSS and we try to avoid work from home people or those on retirement/looking for work as generally it can be very annoying if one person is always home and always just hanging around in the lounge”

The other is to refer to the accommodation itself as being a particular kind of “professional” rental or sharing arrangement. References to “professional house shares” are common, appearing in 542 listings. Examples include:

“MODERN DOUBLE ROOM TO RENT IN GORGEOUS PROFESSIONAL SOUTH LONDON HOUSE-SHARE – VIEW NOW!”

“En-suites available within an executive professional house share in Filton.”

“Newly renovated, fully furnished, bright and spacious high end, professional house share situated within walking distance from Bolton Town centre.”

“I am friendly and easy-going professional living with my partner who is also professional; both working within office hours… We are looking for a friendly and easy-going housemate, preferably professional, who is tidy and clean.”

“If you are looking for private room in the company of like-minded professionals, in a nice house in a good location with young professional housemates, then this is it!”

*3 WORKING PROFESSIONAL FLATMATES*

Table 3. Breakdown of listings detailing and not-detailing “professional” in the advert text.

The findings here mirror broadly those of the “housemate preferences” box. Live-out landlords, live-in landlords, agents and current flatmates are most likely to express a preference for “professionals” in the advert text. “Former flatmates” are – perhaps unsurprisingly – the least likely to specify a preference for “professionals, alongside “current tenants” (though the total sample for the latter is small – just 16 posts out of 124 detailed a preference for professionals in the advert text). Before turning to the implications of these data, details how many listings did either a combination of expressing a preference for professionals in the housemate preferences and/or the advert text, and those that did neither of these.

Table 4. Matrix table of listings detailing and not-detailing “professional” in the advert text and housemate preferences, number in the sample, and percentage total of listings by that advert poster.

These data illustrate two things. First, there are a substantial number of listings that do not express a preference for a professional prospective tenant in the advert text itself, but do within the housemate preferences box. This is a substantial volume of listings − 5,969 in total, 19% of the total listings in the sample, and a quarter of listings posted by “Live-In Landlords”. This suggests that the inclusion of the “professional” option within the housemate preferences box is likely to lead to more listings excluding non-professionals from applying for the property than if relying on advert text alone. The design of the “housemate preferences” function may therefore be an example of the “classification” processes in online platforms (Fields & Rogers, Citation2021, p. 78) exacerbating the exclusion of prospective tenants on housing benefit. If the housing preferences box did not exist, these adverts may be prima facie accessible to those in receipt of housing support seeking to apply.

Prior to their statement to users in 2020, SpareRoom’s housemate preferences included the prompt: “Housing benefit considered?”. This was widely utilised in adverts (Meers & Hunter, Citation2019, p. 225). In their message to users removing this function, SpareRoom underscored that “Landlords and agents can’t list their rooms as unavailable to housing benefit claimants on property sites any more” (SpareRoom, Citation2020). The removal of the “housing benefit considered?” is an acknowledgement that these inputs matter when considering the availability of property to prospective occupants. However, removing this explicit barrier to such applications has seemingly been replaced by the option of the implicit “professional” barrier.

Second, there are some substantial differences in the extent to which advert posters express a preference for a professional prospective tenant, either through the advert text or housemate preferences box. A large majority of listings made by “former flatmates” – a total of 70% – detailed no such preference, as opposed to a sample average of 44%. The same is true of “current tenants” – however, very few identify as such in the sample (just 4% of listings), making drawing conclusions from these percentage differences problematic. For our purposes, what is perhaps most striking is that “current flatmates” are broadly in line with live-in landlords, live-out landlords, and agents – indeed, “current flatmates” are more likely than “agents” to express a preference for professionals within the housemate preferences box. This suggests that these exclusionary practices and “queuing” techniques attributed to landlords (see Preece et al., Citation2020) extend to current flatmates posting advertisements to fill rooms themselves.

This suggests two things. First, that the “queuing techniques” so often ascribed to landlords may also apply to sitting tenants looking for housemates. This could be for a number of reasons. Flatmates may consider the “professional” label in much the same way Cowan characterises its use, as associated with “a person in work, who dresses well and is polite and responsible”, drawing “distinction between housing benefit recipients and others in this regard” (Cowan, Citation1999, p. 320). As argued by Maalsan and Gurran, the “ideal” housemate for a sitting tenant is one who has an “active work and social life” which reduces “their time spent at home and their dependency on the household space as central to their lives” (Maalsen & Gurran, Citation2021, p. 15). Put simply, sitting tenants may perceive “professionals” as better to share property with. Second, it could be that sitting tenants share the well-documented concerns of landlords about the risk of non-payment of rent for housing benefit recipients (O’Leary & Simcock, Citation2020). This is in turn could be associated with the preponderance by many landlords in England to rent to groups using joint tenancies – where tenants are, in the event of non-payment, ultimately liable for the rent of their fellow joint tenants (a problem characterised as a potential “trap” of tenancy law for renters by Sparkes and Laurie (Citation2014)).

5.2. Relative affordability of listings

The final issue to consider is whether this differentiation across listings is simply a matter of cost: do more expensive listings, unaffordable to tenants in receipt of housing benefit, account for the majority of those specifying a preference for professionals? In order to explore this question, listings were matched against their respective Broad Rental Market area and in turn LHA rates. Given the majority of listings are for rooms in shared properties, shared-accommodation rates were used as a reference point.

Only a minority of listings were within LHA rates – a total of 2,795, or 9% of the sample. Comparing those listings within LHA rates and those above, there were significant differences. As detailed in , those listings within LHA rates were considerably less likely to detail a preference for “professional” prospective tenants, with 59% of the sample not doing so, compared to 41% of the sample outwith LHA rates.

Although these data demonstrate that listings within LHA rates are more likely not to specify a preference for professionals, a significant proportion of the sub-sample still do so (41%). Indeed, for those listings detailing a preference for professionals within the advert text but not in housing preferences, the rates are the same as for the rest of the sample. This demonstrates that a significant proportion of the cheapest listings still specify that “professionals” are preferred. It is not a phenomenon confined to only the most expensive properties. This is significant, as it suggests that even that sub-set of properties which are affordable to those on LHA, still suffer from these same exclusionary practices. and take a broader look at rents and LHA shortfalls across the sample. The former details the average and median rents for listings, and the latter the average and median shortfalls between LHA levels and rent.

Table 6. Average and median rents per month in property listings.

Table 7. Average and median shortfall between listed rent and LHA.

It is clear from these data that there is a modest association between higher rents and a greater likelihood of specifying a preference for professionals in the advert text, housemate preferences, or both. Average LHA shortfalls varied between -£153.24 for those listings specifying a preference in both, to an average of -£127.21 for those did neither. However, given the standard deviation of LHA shortfalls within the data sits at -£148.60, these variations are relatively modest. Indeed, the median rents across all four quadrants in remain the same. Taken together, and both suggest that – although listings with a lower LHA shortfall and rent are less likely to exclude non-professionals – the practice is widespread across the whole of the sample.

Table 5. Listings with advertised rent within LHA rates compared to listings above LHA rates. Percentages detail the proportion of listings within the subsample.

This is significant for those tenants on low-incomes seeking property to rent online. Even among the small proportion of listings (approximately 9%) which were within LHA rates, 41% excluded non-professionals (13% via the housing preferences function, 18% via the advert text, and 10% by doing both). This suggests that the already heavily constrained availability of affordable accommodation is made even more acute by indirect exclusion of benefit recipients in advert listings. As above, the housing preferences box appears to be complicit − 10% of listings within LHA affordability only exclude non-professionals via use of the “professionals” category built-in to SpareRoom.co.uk.

6. Conclusion

What this study suggests is that the widely derided and unlawfully discriminatory “No DSS” policy is not the only means through which a pre-determined categorisation of prospective tenants can exclude those in receipt of housing benefit. The classification of the “professional” – presented as “distinct” or even antithetical to a recipient of housing benefit (Cowan, Citation1999, p. 320) – allows advert posters on these platforms to signal their reluctance to let or share with those on low-incomes or without stable work. Housing benefit recipients are systemically excluded from listings on online flat share websites through the construction of the “professional” prospective tenant and the design of the SpareRoom.co.uk platform itself exacerbates this exclusion by facilitating the use of this “professional” construction. As Lynne Mapp, a tenant in receipt of housing benefit struggling to find property, put it to the Work & Pensions Committee, “on letting agents saying “No DSS”, they are dressing it up now by saying, ‘Working professionals only’ or ‘People who are working only’ (Work and Pensions Committee, Citation2019b).

Within this study of 31,909 SpareRoom listings, the preference for “professional” prospective tenants was widespread, accounting for a majority (53%) of the sample. Although there are variations depending on the advert poster, strikingly, current flatmates are more likely to exclude non-professionals via the advert text and SpareRoom’s housemate preferences than agents, and remain broadly in line with Live-in and Live-out landlords. It is also clear from the data that the design of SpareRoom itself contributes to these exclusionary practices. Although SpareRoom removed pre-determined inputs for directly excluding recipients of housing benefit (e.g. “No DSS” (see SpareRoom, Citation2020)), by providing a housemate preferences box the platform introduces a “classification” that can achieve a similar end (Fields & Rogers, Citation2021, p. 79). Indeed, the data suggest that the very inclusion of this classification at the point at which a user posts a listing may lead to higher levels of exclusion. A substantial volume of listings − 5,969, or 19% of the total listings in the sample – do not express a preference for a professional prospective tenant in the advert text itself, but do within the housemate preferences box. This suggests that the inclusion of “professional” within the housemate preferences box is likely to lead to more listings excluding non-professionals than if relying on the user to do so themselves in the advert text alone.

These findings have three implications. First, they suggest the much-derided “No DSS” rubric may have evolved into a “professionals only” proxy. Legal action and campaigning work in the UK – particularly by Shelter – has been incredibly effective at reducing the prevalence of “No DSS” style express exclusion of housing benefit recipients in rental advertisements (Shelter, Citation2021). Indeed, SpareRoom itself, alongside other online platforms, removed an existing “no housing benefit” preferences function, stating in a message to users that advert posters “can’t list their rooms as unavailable to housing benefit claimants on property sites any more” (SpareRoom, Citation2020). However, much like Rosett & Cressey’s analogy for discretionary decision-making (1976, p. 170), the findings here suggest that exclusion of housing benefits is like a closed tube of toothpaste; if squeezed at one spot, the bulge simply moves elsewhere. The use of the indirect “professionals only” rubric appears to have supplanted the more direct forms of exclusionary practices targeted by campaigners and legal action.

Second, this study suggests that these exclusionary practices are not something limited solely to landlords and lettings agents. In flat-sharing arrangements, such as tenants looking for replacement housemates on joint-tenancies, similar levels of expressed preferences for “professionals” were present in the sample. This suggests that those “queuing” techniques and other exclusionary practices identified by Preece et al., also apply to sitting tenants looking for fellow flatmates (Preece et al., Citation2020). Research into the challenges faced by low-income renters, especially those flat-sharing out of choice or necessity, should examine more indirect forms of exclusion, such as “professionals only”, in addition to the more express forms of exclusion associated with “No DSS”. It is clear from this research that targeting the express exclusion of certain categories of prospective tenants, though welcome, leaves open these indirect forms of exclusion.

Third, these data suggest that even small elements within the design of online renting platforms can have significant impacts on the advert poster’s behaviour and consequently the resulting listings. As Boeing et al. have argued:

“Technology platforms have the potential to broaden, diversify, and equalize housing search information, but they rely on landlord behavior and, in turn, likely will not reach this potential without a significant redesign or policy intervention” (Boeing et al., Citation2021, p. 1).

Given these problems, why do online renting platforms, and SpareRoom in particular, provide a built-in means to express a preference for “professionals” in listings? As argued above, SpareRoom does not define the term and advert posters are welcome to, if they wish, assess the affordability of the property relative to the applicant’s earnings at the point of application in any event. It appears it can only serve much the same function highlighted by Cowan: as a moniker for a “good tenant”, someone who “appears to be a person in work, who dresses well and is polite and responsible”, with a distinction drawn a “between housing benefit recipients and others in this regard” (Cowan, Citation1999, p. 320). Given its clear potential to exclude low-income prospective renters from applying for listings, this “professionals only” proxy should be consigned to the same fate as the express exclusion of housing benefit recipients.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aalbers, M., Hochstenbach, C., Bosma, J. & Fernandez, R. (2021) The death and life of private landlordism: How financialized homeownership gave birth to the buy-to-let market, Housing, Theory and Society, 38, pp. 541–563.

- Alsudais, A. (2021) Incorrect data in the widely used inside airbnb dataset, Decision Support Systems, 141, pp. 113453.

- Beswick, J., Alexandri, G., Byrne, M., Vives-Miró, S., Fields, D., Hodkinson, S. & Janoschka, M. (2016) Speculating on London’s housing future: The rise of global corporate landlords in ‘post-crisis’ urban landscapes, City, 20, pp. 321–341.

- Blandy, S. (2018) “Precarious homes: The sharing continuum, in H. Carr, B. Edgeworth & C. Hunter (Eds) Law and the Precarious Home: Socio-Legal Perspectives on the Home in Insecure Times, pp. 23–46 (Oxford: Hart).

- Boeing, G., Wegmann, J. & Jiao, J. (2020) Rental housing spot markets: How online information exchanges can supplement transacted-rents data, Journal of Planning Education and Research, https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X20904435

- Boeing, G. (2020) Online rental housing market representation and the digital reproduction of urban inequality, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52, pp. 449–468.

- Boeing, G., Besbris, M., Schachter, A. & Kuk, J. (2021) Housing search in the age of big data: Smarter cities or the same old blind spots?, Housing Policy Debate, 31, pp. 112–126.

- Boeing, G. & Waddell, P. (2017) New insights into rental housing markets across the United States: Web scraping and analyzing craigslist rental listings, Journal of Planning Education and Research, 37, pp. 457–476.

- Bonnet, F. & Pollard, J. (2021) Tenant selection in the private rental sector of Paris and Geneva, Housing Studies, 36, pp. 1427–1445.

- Brewer, M., Corlett, A., Handscomb, K., McCurdy, C. & Tomlinson, D. (2020) The Living Standards Audit 2020. Resolution Foundation, Available at https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2020/07/living-standards-audit.pdf (accessed 5 May 2021).

- Bryne, M. (2020) Generation rent and the financialization of housing: A comparative exploration of the growth of the private rental sector in Ireland, the UK and Spain, Housing Studies, 35, pp. 743–765.

- Bryne, M. & McArdle, R. (2020) Secure occupancy, power and the landlord-tenant relation: A qualitative exploration of the Irish private rental sector, Housing Studies, https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1803801

- Centre Point (2019). Everything you need to know about DSS discrimination, Available at https://centrepoint.org.uk/about-us/blog/what-is-dss-discrimination-everything-you-need-to-know/# (accessed 5 May 2021)

- Christiansen, K. & Lewis, R. (2019) UK private rented sector: 2018, Office for National Statistics, Available at https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/articles/ukprivaterentedsector/2018#household-flows-between-tenure-sectors (accessed 5 May 2021)

- Clair, A. (2021) The effect of local housing allowance reductions on overcrowding in the private rented sector in England, International Journal of Housing Policy, https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2021.1964253

- Clarke, C. & Oxley, M. (2017) “Using incentives to improve the private rented sector for people in poverty: An international policy review”. Cambridge Centre for Housing and Planning Research, Available at https://www.cchpr.landecon.cam.ac.uk/system/files/documents/I_P_Review.pdf (accessed 27 October 2021)

- Cowan, D. (1999) Housing Law and Policy (London: Macmillan).

- Fields, D. & Rogers, D. (2021) Towards a critical housing studies research agenda on platform real estate, Housing, Theory & Society, 38, pp. 72–94.

- Harris, N., Fitzpatrick, C., Meers, J. & Simpson, M. (2020) Coronavirus and social security entitlement in the UK”, Journal of Social Security Law, 27, pp. 55–84.

- Harris, E. & Nowicki, M. (2020) GET SMALLER’? Emerging geographies of micro-living, Area, 52, pp. 591–599.

- Hoolachan, J., McKee, K., Moore, T. & Soaita, A. (2017) Generation rent’ and the ability to ‘settle down’: Economic and geographical variation in young people’s housing transitions, Journal of Youth Studies, 20, pp. 63–78.

- Institute for Fiscal Studies (2020). The temporary benefit increases beyond 2020–21, Available at https://ifs.org.uk/uploads/CH8-IFS-Green-Budget-2020-Temporary-benefit-increases.pdf (accessed 5 May 2021)

- Jiao, J. & Bai, S. (2020) An empirical analysis of airbnb listings in forty American cities, Cities, 99, pp. 102618.

- Joyce, R., Mitchell, M. & Keiller, A. (2017) Low-income households increasingly exposed to rent increases, Institute for Fiscal Studies, Available at https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/9987 (accessed 5 May 2021)

- Layard, A. (2018) Property and planning law in England: facilitating and countering gentrification, in L. Lees &M. Phillips (Eds) Handbook of Gentrification Studies, pp. 444–466 (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar).

- Maalsen, S. (2020) ‘Generation share’: Digitalized geographies of shared housing, Social & Cultural Geography, 21, pp. 105–113.

- Maalsen, S. & Gurran, N. (2021) Finding home online? The digitalization of share housing and the making of home through absence, Housing, Theory & Society, https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2021.1986423

- Maalsen, S., Wolifson, P., Rogers, D., Nelson, J. & Buckle, C. (2021) Understanding Discrimination Effects in Private Rental Housing (Australia: AHURI).

- Marsh, A. & Gibb, K. (2019) The private rented sector in the UK: An overview of the policy and regulatory landscape, UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence, Available at https://housingevidence.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/TDS-Overview-paper_final.pdf (accessed 5 May 2021)

- McKee, K., Moore, T., Soaita, A. & Crawford, J. (2017) Generation rent’ and the fallacy of choice, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41, pp. 318–333.

- McKee, K., Soaita, A. & Hoolachan, J. (2020) Generation rent’ and the emotions of private renting: Self-worth, status and insecurity amongst low-income renters, Housing Studies, 35, pp. 1468–1487.

- McKee, K. & Soaita, A. (2018) The ‘frustrated’ housing aspirations of generation rent, UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence, Available at https://eprints.gla.ac.uk/169206/1/169206.pdf (accessed 5 May 2021)

- Meers, J. & Hunter, C. (2019) No children, no DSS, no students: Online adverts and “property guardianship, Journal of Property, Planning and Environmental Law, 11, pp. 217–229.

- Memery, C., Kerrins, L. & Browne, M. (2002) Rent supplement in the private rented sector: Issues for policy and practice, Comhairle, Available at https://www.threshold.ie/assets/files/pdf/rent_supplement_social_policy_report__comhairle.pdf (accessed 5 May 2021)

- Morris, A., Hulse, K. & Pawson, H. (2021) The Private Rental Sector in Australia: Living with Uncertainty (London: Springer).

- National Housing Federation (2019). Housing benefit freeze: 9 in 10 homes unaffordable for families, 7 October 2019, Available at https://www.housing.org.uk/news-and-blogs/news/housing-benefit-freeze-9-in-10-homes-unaffordable-for-families/ (accessed 5 May 2021)

- O’Leary, C. & Simcock, T. (2020) Policy failure or f***up: homelessness and welfare reform in England, Housing Studies, https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1849573

- Ortega-Alcázar, I. & Wilkinson, E. (2021) ‘I felt trapped’: Young women’s experiences of shared housing in austerity Britain, Social & Cultural Geography, 22, pp. 1291–1306.

- Powell, R. (2015) Housing benefit reform and the private rented sector in the UK: On the deleterious effects of short-term, ideological ‘knowledge’, Housing, Theory and Society, 32, pp. 320–345.

- Power, E. (2017) Renting with pets: A pathway to housing insecurity?, Housing Studies, 32, pp. 336–360.

- Preece, J., Bimpson, E., Robinson, D., McKee, K. & Flint, J. (2020) Forms and Mechanisms of Exclusion in Contemporary Housing Systems: A Scoping Study, UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence, Available at https://housingevidence.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/200204-forms-and-mechanisms-of-exclusion-in-contemporary-housing-systems_final.pdf (accessed 5 May 2021).

- RightMove. (2019). 2019/20 Annual Report, Available at https://plc.rightmove.co.uk/∼/media/Files/R/Rightmove/2019/2019%20Annual%20Report.pdf (accessed 5 May 2021).

- Rosett, A. & Cressey, D. (1976) Justice by Consent (Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott).

- Rugg, J., Rhodes, D. & Jones, A. (2002) Studying a niche market: UK students and the private rented sector, Housing Studies, 17, pp. 289–303.

- Rugg, J. & Rhodes, D. (2018) The Evolving Private Rented Sector: Its Contribution and Potential, Nationwide Foundation, Available at http://www.nationwidefoundation.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2018/09/Private-Rented-Sector-report.pdf

- Shelter. (2017). “Analysis: Local housing allowance freeze, Available at https://england.shelter.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/1349012/Final_LHA_analysis.pdf (accessed 5 May 2021).

- Shelter. (2021). “End DSS discrimination, Available at https://england.shelter.org.uk/support_us/campaigns/dss (accessed 27 October 2021).

- Simcock, T. (2021) Home or hotel? A contemporary challenge in the use of housing stock”, Housing Studies, 34, pp. 588–608.

- SpareRoom. (2020). “DSS/housing benefit rooms, Available at https://www.spareroom.co.uk/dss-rooms-to-rent (accessed 5 May 2021).

- SpareRoom. (2021). Glossary of terms, Available at https://www.spareroom.co.uk/content/info-faq/glossary-of-terms/ (accessed 5 May 2021).

- Sparkes, P. & Laurie, E. (2014) Tenancy Law and Housing Policy in Multi-Level Europe: England and Wales. European Union, Available at https://www.uni-bremen.de/fileadmin/user_upload/fachbereiche/fb6/fb6/Forschung/ZERP/TENLAW/Brochures/England_WalesBrochure_09052014.pdf (accessed 28 October 2021).

- Verstraete, J. & Moris, M. (2019) Action–reaction. Survival strategies of tenants and landlords in the private rental sector in Belgium, Housing Studies, 34, pp. 588–608.

- Watt, P. (2020) ‘Press-ganged’ generation rent: Youth homelessness, precarity and poverty in East London, People, Place and Policy Online, 14, pp. 128–141.

- Watts, B. & Stephenson, A. (2017) ‘No DSS’ A review of evidence on landlord and letting agent attitudes to tenants receiving housing benefit, Shelter Scotland, Available at https://assets.ctfassets.net/6sqqfrl11sfj/tjWBSAqVrqBOnA3eT3C9j/dd94e17d6070f98f5ad2fa6c03364692/Shelter_No_DSS_Report.pdf (accessed 5 May 2021).

- Work & Pensions Committee. (2019a). Written evidence from Shelter (NDS0001), Available at http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/work-and-pensions-committee/no-dss-discrimination-against-benefit-claimants-in-the-housing-sector/written/97946.pdf (accessed 5 May 2021).

- Work and Pensions Committee. (2019b). Oral evidence: No DSS: discrimination against benefit claimants in the housing sector, HC 1995, Available at http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/work-and-pensions-committee/no-dss-discrimination-against-benefit-claimants-in-the-housing-sector/oral/100549.pdf (accessed 5 May 2021).

- York County Court. (2020). Statement of reasons: F00YO154, Available at https://tinyurl.com/an6pja2 (accessed 5 May 2021).