Abstract

Online platforms have become central to the operation of the housing market in the UK and elsewhere. This paper extends recent scholarship on the impacts of ‘the digital’ on housing outcomes by assessing the ‘performative’ ability of property platforms to maintain and construct market practices. Using actor-network theory, a distinction is made between platforms as intermediaries that advertise properties and link different parties to a transaction and as mediators, capable of changing how the world is interpreted. Recognising platforms as intermediaries enables a classification of matchmaking types. Recognising platforms as mediators enables an assessment of the extent of their impact on tenure preferences and mobility and raises questions about the applicability of sharing economy concepts to housing. Actor-network theory allows a qualified and differentiated assessment of the varied impact of platforms, enabling a consideration of the factors that lead to continuity as well as those that promote change.

Introduction

Online platforms, defined as digital services that facilitate interactions ‘between two or more distinct but interdependent sets of users’ (OECD Citation2019, 20) are now very widely used within housing markets in the UK (Rowley, Citation2005) as in the US (Besbris, Citation2020, 26) and elsewhere. This paper seeks to provide a framework that is derived from actor-network theory (ANT), performativity and to some extent practice theory and that might answer the deceptively simple question about whether and how online property platforms (hereafter, ‘platforms’) have influenced UK housing market practices, meaning the practices associated with the search for a home and with the making of property transactions. Performativity means a repeated concern with how markets work and like ANT, of which concepts of performativity are an extension (Latour, Citation2005, p. 63), has the merit of assuming that technology and objects have a degree of agency.

The emergence of platforms is significant as it has occurred alongside other economic and social shifts, including an increase in e-commerce and a concomitant widening of socioeconomic inequalities (Piketty, Citation2014) and spatial segregation (Musterd et al., Citation2017). It is intuitive, therefore, to link these various trends together circumstantially, even if not causally, in a global paradigmatic transformation. However, as this paper argues, to make any such causal inferences in a rigorous way should proceed first from a precise conceptualization and typology of platforms and the logic of the relevant technology. Understanding the impact and workings of platforms is overdue and timely and should be seen as a necessary aspect of any serious attempt to understand how housing markets work.

This account starts with an explanation of different ways of understanding the role of online technology in housing markets, with an emphasis on ANT. The paper then poses three questions that generate the different sections in the paper:

How, acting as intermediaries, do platforms interact with the different parties involved in a transaction?

To what extent, acting as mediators, have platforms changed the housing market?

Finally, what are the regulatory implications?

Theorising and analysing platforms

Owing to their high public profile and to the importance of housing within public and media discourse, platforms have generated a huge amount of information both on their websites and in the associated ‘grey’ literature (the principal UK financial and property newspapers and journals, commercial reports and blogs). The sheer quantity of available information indicates a wide and potentially important research agenda. The analytical task is to find a way that relates the conceptual to the mass of available information; a way that provides more than a mere case study of platform effects whilst also avoiding ‘pure conceptual speculation’ (Beaulieu et al., Citation2007; Gad & Ribes, Citation2014).

The relevance of ANT is to offer the methodological precept ‘to start from ‘the middle of things’ (Latour, Citation2005, p. 27, between the conceptual and the ever-changing multiplicities of media and scientific discussions. In principle, therefore ANT is well suited to analysing the implications of platforms. ANT is not the only way of undertaking a ‘middle range’ analysis, however. Its specificity needs to be explained. Moreover, the distinction between case study and conceptual approaches has taken a slightly different form in accounts of platforms in housing, compared to socio-technical studies and has become conflated with another distinction between the micro and macro levels of the market.

Case studies, macro studies and middle range analysis

In relation to the micro, existing housing case studies have, for example examined the way that online information is used in housing search strategies by the visitors to Rightmove (the most visited of all UK platforms) (Rae, Citation2015) and the contrasting local impacts where online advertising promotes either innovatory forms of housing provision (Sharam & Bryant, Citation2017) or, in the case of tourist sites, has had an inflationary effect and changed the character of neighbourhoods (Cocola-Gant & Gago, Citation2021; Stabrowski, Citation2017; Wachsmuth & Weisler, Citation2018). Taken together, the case studies reveal a diversity of local market conditions and the persistence of locality as an influence in housing searches.

Other accounts have, in contrast, been mostly concerned with how digital and online technologies reflect broader macro-level economic changes, notably the use of data as capital (Fields & Rogers, Citation2021) and the emergence of new forms of ‘platform real estate’ (Shaw, Citation2020) and the ‘platform economy’ (Montalban, et al., Citation2019). Such accounts, though global in outlook, may be readily applied to UK ‘PropTech’. Private investors note that Rightmove has become one of the most profitable UK companies (Oakley, Citation2018), they believe that real estate, both for sale and for the management of rented property, is a candidate for on-going efficiency gains and, in addition, that real-time data analytics provides a means of predicting trends in demand and prices (D’Adderio, Citation2011).

In assessing the impact of technology, it is insufficient, however, to demonstrate the scale of private investment in PropTech. Evidencing investment still begs the question as to exactly how and if technology has changed market practices, expectations or trends. To give an example: using data made available by Rightmove, Rae (Citation2015) has shown that the availability of online information does not require a substantial reinterpretation of earlier theories of housing search and the formation of submarkets within the owner-occupied sector. The main observed change was not in the factors that influenced the choice of home, but in the way that different stages in the search process (determining the area, determining available properties and then considering the various properties) had collapsed into a single exercise.

The notion of a ‘platform economy’ encompasses a variety of other more specific concepts, including the ‘gig economy’, ‘Uberization’ and ‘the sharing (or shared) economy’. Of these various terms, the gig economy and Uberization are mostly used, pejoratively, to denote the way that some platform companies have reduced the security and other conditions of employment. The sharing economy, meaning the sector of the economy where transactions are made without the transfer of ownership (ONS, Citation2017: p. 4), is distinctive in that it may be applied directly to housing as an influence in favour of renting and the shared occupation of housing units (Baum, Citation2017; Frenken & Schor, Citation2019, p. 124; Sundararajan, Citation2017). Its implications deserve clarification and assessment.

Like the gig economy and Uberization, the sharing economy is a ‘middle range theory’ as defined by Merton (Citation1968, pp. 39–40), namely a theory covering a ‘delimited aspect of social phenomena’ and existing between ‘working hypotheses’ and ‘all-inclusive systematic efforts to develop a unified theory’ of society. ANT, in contrast, is primarily a methodology (Latour, Citation2005, p. 17), combining, inter alia, an emphasis on the problematic construction of meaning and an ontological insistence on the ‘networky character’ of human and non-human interaction (Latour Citation1996). As a result of this latter ontological assumption and contrary to some earlier discussions of performativity in housing, for example by Smith & Munro (Citation2008), ANT cuts across the micro/macro distinction (Latour, Citation2005, p. 184).

This same ‘networky’ assumption also means that ANT is more than a mere variant of social constructionism, an approach that has long been used in housing and social policy research, for example in understanding how issues and situations become defined as a ‘problem’ (Jacobs & Manzi, Citation2000). For Latour (Citation2005, 91) society is indeed constructed, but in a ‘realist’ way akin to a building site through ‘mobilising various entities whose assemblage could fail.’

Performativity and practice

Performative approaches (Çalışkan & Callon, Citation2010; Callon & Muniesa, Citation2005) likewise accept markets are constructed, whilst enquiring as to the role of different practices and actors (including technology as an actor) in making them work. Like ANT, they also assume that markets are characterised by a wealth of information that is itself of empirical value. For ANT, there is no need to search out invisible processes and invisible actors. The focus is on the tangible, visible and traceable, including the comments made by the participants in a situation or process (Latour, Citation2005, pp. 4, 21, 31).

Tracing associations, relationships and impacts involves, in part, the use of interviews and social surveys, including secondary, published survey information. The English Housing Survey (EHS) is, for example, the largest single source of housing data in the UK. Whilst not dealing directly with the use of platforms, the EHS shows patterns of occupation that might be expected to change over time if the growing use of platforms were having an effect. Moreover, the information contained on the platform websites is itself relevant and has the advantage of being in the public domain.

To an extent, housing researchers have already noted that the data available from websites may supplement conventional survey data in identifying trends (Boeing et al., Citation2020). The significance of the information available on platforms goes beyond this. In a world that has moved online, online information becomes the infrastructure that allows markets to continue whilst also acting as a framing device within which transactions are undertaken.

The framing processes mean that some groups, activities and effects are excluded, so leading to ‘overflows’ that correspond broadly to ‘the category that economists call externalities’ (Callon, Citation2007: p. 143). These include ethical and political questions that cannot be resolved through monetary compensations (ibid: p. 160). Markets are understood as ‘socio-technical agencements’ (STAs) where agencement means both agency and assemblage (Callon, Citation2007) and whose operation involves a double process of framing and overflowing and in which governmental action seeks to regulate undesirable and promote desirable overflows. ANT has the merit therefore of treating regulation as a necessary aspect of market activities. Moreover, through the incorporation of regulation, the ultimate issue becomes, as Smith et al. (Citation2006: p. 95) have stated, ‘not how are housing markets performed, but how should they be performed’.

STAs are, as their name implies, hybrid (human and nonhuman) combinations of elements and networks where rules, routines and value orientations become meaningful through their enactment. Online platforms may therefore be treated as a specific form of market STA.

Performativity and agency

Other, practice-based theories make similar assumptions about the hybrid human/technological character of modern businesses and institutions. For Orlikowski (Citation2005) for example technology becomes ‘mangled’ with social practices. Notions of mangling and hybridity provide, in turn, an initial answer as to whether technology might influence the housing market. Technology offers the promise of change. However neither technology nor the market should be given any special or distinct explanatory status. They operate together.

Saying that technology offers the promise of change implies in turn a separation of theory from practice, with practices understood in this context as ‘signifying the common-sensical notion of practical activity and direct experience’ (Orlikowski, Citation2010: pp. 23–24). In particular, concepts of performativity suggest that economic laws and, by extension, economic discourses contribute to the phenomenon that they seek to explain (Callon, Citation1998; Smith et al., Citation2006). Economic theory, from this perspective, is not simply an explanation. It is a statement of how the economy ought to and will work. However, economic laws are also not legal documents that prescribe a specific course of action. To this extent, therefore, performativity also admits the possibility of ‘misfires’ (Butler, Citation2010) where events in the ‘real world’ do not turn out as expected or where an innovation undermines its own logic.

Platforms are a form of communicative technology and, as such, involve two, overlapping, effects (Latour, Citation2005: 39): as an intermediary and as a mediator. An intermediary is a messenger that ‘transports meaning or force without transformation’ (ibid), providing information and connections but no more. In market terms they may facilitate or enact introductions between parties. In contrast, mediators ‘translate, distort or modify the meaning or elements they are supposed to carry’ (ibid). Communicative technology, including online platforms, may, moreover, act simultaneously as both an intermediary and a mediator. The distinction is also fluid. Technology and social practices may switch from intermediary to mediator and back again. The role of platform as intermediary and mediator is recognised in the account of ‘platform real estate’ by Shaw (Citation2018), but is not fully applied or operationalised.

An intermediary, for all its potential complexity, leads in one direction, as defined by the messenger. The task of analysis is to describe how the different parties are deployed in relation to each other in a market that is itself diverse (Latour, Citation2005: pp. 136–137). The platforms need to be classified and described, with the classification being defined by the character of the relation between different parties. Description is therefore a necessary aspect of ANT, intended to ground analysis in reality and to reveal how human and non-human actors are deployed. A mediator, in contrast, leads in ‘multiple directions’, ‘where passions, opinions, and attitudes bifurcate at every turn’ (Latour, Citation2005: p. 39). As a result, mediated understandings may go beyond those intended by platform designers and firms and, through repetition, may also become internalised (Callon & Muniesa, Citation2005 p. 1237: D’Adderio, Citation2011, p. 209) as part of the users’ habitual background. As a result, types of mediation are best examined by actual and claimed outcomes.

Though the intermediary/mediator distinction is characteristic of ANT, similar distinctions have arisen in other accounts. For example, Bessy & Chauvin (Citation2013) have defined the institutional forms of market intermediaries, noting that these ‘can improve the coordination of actors in markets, but also reorganize the markets in different ways’ (p. 111). Likewise, in an ethnographic study of real estate agents in the New York area, Besbris (Citation2020) notes that agents act as market intermediaries but also ‘mediate consumers’ experiences by helping them narrow down search options, negotiate on their behalf and give advice’ (ibid, p. 113).

Both Bessy & Chauvin and Besbris are talking about the agency of human intermediaries, such as property professionals. ANT may also be used to analyse the work of property professionals, as Smith et al. (Citation2006) showed in an account of the Edinburgh housing market at a time when platforms were not as widely used or sophisticated as they have become. However, the distinctiveness of ANT is to transfer agency from specific actors to networks. Neither performativity nor ANT favours the language of individual choice and decision, as this is too close to the oversimplified behavioural concepts of the rational ‘homo economicus’ (Callon, Citation1998: pp. 50–51). To the extent that it is possible to identify individual purchase and rental decisions, these are treated as the cumulative product of the interaction between multiple sources of information and influence, both technological and human.

Platforms as intermediaries

In performing the market, platforms also enact its uncertainties. For this reason, analysis does not begin with the techniques of asset valuation and calculation, as suggested by Callon & Muniesa (Citation2005). Instead, analysis starts, as Latour (Citation2005: p. 45) puts it, ‘with the under-determination of action’, with the process of creating a network so that a transaction can be made. A property may be valued in the stages identified by Callon & Muniesa (Citation2005: p. 1231) but will not be sold until a buyer comes forward.

The ability of the market to perform is therefore dependent on an initial ‘matchmaking’ process in which people, goods and services are brought together, albeit seldom in a completely synchronized timescale with immediate communication. Buyers and sellers need time to consider and respond to information. The performativity of the market is nevertheless dependent on mechanisms that facilitate speedy communication amongst the largest possible audience. Online platforms, considered as STAs, have exactly this role of matchmaking (OECD, Citation2019), supplementing or replacing human intermediaries (such as auctioneers, brokers, dealers and agents).

Classifying platform practices

The market-making function of platforms in turn enables their logical classification in relation to how they create associations, bringing together buyers and sellers, renters and landlords. Perren & Kozinets (Citation2018) define joint online presence as a form of ‘consociality’. To facilitate matchmaking, however, consociality must be converted into an exercise in ‘intermediation’, the action of the platform business as an intermediary. As a logical extension, therefore, it is possible to distinguish between ideal types of e-commerce STA, depending on whether the platforms have high or low levels of consociality, as determined by whether the platforms allow peer-to-peer (P2P) transactions and high or low levels of intermediation depending on their level of intervention in transactions.

applies the consociality/intermediation classification to platforms currently active in the UK housing market.

Table 1. A classification of property platforms.

The table as presented ignores cross listing. Local agents use their own local platforms as well as Rightmove and Zoopla. Specialist full matchmaking and hub businesses seek to take advantage of the larger traffic volumes of other platforms. Onthemarket is, for example, a partner company to Facebook Marketplace. Purplebricks, an online hub, also lists on Rightmove and makes this a selling point in its marketing.

The distinctions are nevertheless significant in relation to business aims. ‘Enablers’ and ‘connectors’ are advertisers that do not, in general, compete directly with traditional property agents. The high intermediation platforms– the full matchmakers and hubs – in contrast are more innovative in attempting to either create new markets for short-term housing or ‘disrupt’ the business of established agents.

A further qualification is necessary. As presented by Perren & Kozinets (Citation2018) the typology rests on the concept of a ‘lateral exchange market’, a ‘technologically intermediated exchange between actors occupying equivalent network positions’ (ibid, p. 20). Lateral exchange ignores the asymmetries that ANT and many other approaches recognise as characteristic of markets and societies. ANT focuses, in part, on the information used in market exchange (Çalışkan & Callon, Citation2010). Informational asymmetries arise because the seller of a good, service or property invariably knows more about its character and performance than the buyer (Stigler, Citation1961). They also arise from differential access to information amongst consumers and other market players.

Market supporting or neutral platforms

Of the various platform types, the enablers have the most online visitors. According to the traffic analysis site ‘Similarweb’, Rightmove was ranked number 17 amongst all UK websites in 2020, with 183.6 million visits in June of that year.Footnote1 Zoopla was ranked number 43 in the UK. No other specialist property platform is listed in the top 50 most popular UK websites.

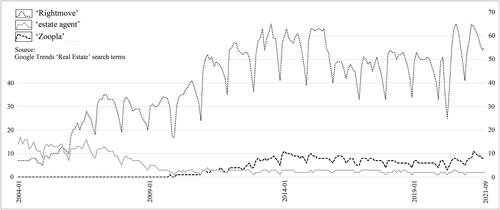

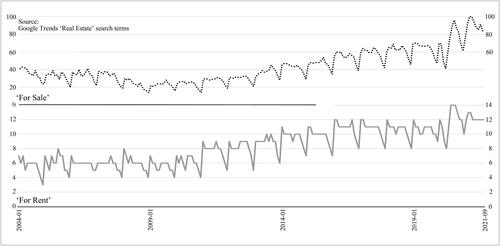

Rightmove and Zoopla also dominate searches revealed by Google Trends.Footnote2 As shown in , searches for ‘Rightmove’ and ‘Zoopla’ increased markedly from about 2010 to 2015, after which they have stabilised, with seasonal and other fluctuations associated with the pandemic restrictions of 2020 and 2021. Searches for ‘estate agent’ declined in the same period and remain low. To an extent, however, stability in the number of searches for Rightmove and Zoopla conceals a continuing growth in the number of online searches using the terms ‘for sale’ and ‘for rent’ as shown in . Searches of the term for ‘for rent’ are less numerous, varying between 11 per cent and 23 per cent of ‘for sale’ searches, but have a similar rate of increase and similar fluctuations.Footnote3 Other data from Google Trends shows that the popularity of ‘for sale’ and ‘for rent’ is more apparent in Scotland and Northern Ireland, suggesting more direct contacts with local agents (or solicitors in Scotland) in these nations.

Under the enabling model characteristic of Rightmove and Zoopla, matchmaking involves a two-stage process where the platform generates leads for the property agent that has made the listing. The transactional stage is then facilitated by the agent, even for a potentially different property. Agents therefore retain their long-standing role as advisors to consumers. Agents also continue to serve the existence of a minority of offline purchasers and renters, about 22 per cent of transactions according to Advantage Zoopla (Citation2020).

The enabling role means a business strategy that serves, rather than transforms, the housing market. For Rightmove, for example, the business strategy is to ‘to reach the largest audience of UK home movers’.Footnote4 The logic is about efficiency and consumer sovereignty. Rightmove and Zoopla are also clearly aimed at the UK property market, though Rightmove also has a section listing overseas properties in which UK residents might be interested. Elsewhere in the world, apart from ‘Idealista’, operating in Portugal, Spain and Italy, multi-national property platforms are rare (Keith, Citation2020). The UK, national orientation of Rightmove and Zoopla is not unusual, therefore.

In serving the housing market, enablers charge property agents. The level of charges by Rightmove in particular and the apparently opaque character of the pricing policies is of contention amongst agents who have little choice but to use the listings services despite the existence of lower priced alternatives in Zoopla and a third enabler ‘Onthemarket’ launched in 2015. (‘Estate Agent Today’, 22/10/2019). Rightmove and other similar platforms would be vulnerable to economic pressure were agents to act collectively. However, agents have not yet acted collectively, certainly not in the sense of an organised embargo and collective action would be difficult to organise.Footnote5 Nevertheless, an analysis of the Rightmove annual reports and Zoopla press releases undertaken by Keith (Citation2021) suggests that, since about 2018, Rightmove is losing affiliated agents, in part to Zoopla.

The high consociality/low intermediation ‘connectors’ Facebook Marketplace and Gumtree are far ahead of the property sites in the number of visits. Facebook is rated UK number 3 by SimilarWeb, whilst Gumtree is number 36 (counting visits to all sections of Facebook and Gumtree, not just the property section).

Facebook Marketplace and Gumtree are international platforms aimed predominantly for the P2P sale of second-hand goods. They use the same model for property and unless a link is provided to another platform, they display a limited range of property information compared to Zoopla and Rightmove. Neither Facebook nor Gumtree charge for a basic listing. Revenue comes from third-party advertising, including targeted advertising and on Gumtree from sponsored listing that gives an item greater prominence.

Market innovative platforms

Full matchmakers such as SpareRoom and Airbnb take the P2P model further by organising and supporting the letting of rooms and houses. They have different target markets, with Airbnb focussing more on short-term tourist lets. Some convergence, however, is apparent between the two sites through the introduction in 2020 of a new ‘sublet’ feature within Airbnb, aimed at longer-term stays of one month or more. The market for ‘sublet’ ostensibly includes students, health care professionals and others on work assignments or changing jobs.

Nevertheless, the character of the sites is obviously very different. The provision of tourist accommodation means an emphasis on ‘destinations’ on the Airbnb site, whereas SpareRoom is about the practicalities and sensitivities of living together. These latter concerns lead SpareRoom to invite prospective tenants to provide personal preferences, whether for example for LGBT households, vegetarian households or non-smoking households and, in addition, to provide personal photographs. SpareRoom is distinctive amongst property platforms in matching people to each other and tenants to landlords as well as matching renters (or buyers) to a property.

The final type of platform, the hubs, is more diverse, covering businesses that compete with conventional property agents and others, notably ‘property guardians’ (Ferreri & Dawson, Citation2018; Meers & Hunter, Citation2020), that have sought to create new market types. Purplebricks, arguably the best-known hub in the UK, is an example of a company that seeks to bypass local estate agents in favour of a network of agents under centralised control. Purplebricks uses freelance, self-employed agents on the gig economy model to reduce transaction costs and, in so doing, has aimed to undercut fees charged by estate agents (‘Financial Times’ 03/07/2019). The use of freelance agents is not a necessary aspect of the ‘hub’ model, however. The appointment of salaried staff would also be possible and might have advantages in terms of quality control (Perren & Kozinets, Citation2018).

Whilst hubs offer high levels of support compared to enabler or connector platforms, support may be lower than offered by the traditional agents that advertise on the enablers. Purplebricks argues, nevertheless, that it receives high levels of customer satisfaction and that the attraction of online technologies and online property sales is not just about prices and costs, but is also generational: ‘Generation digital’ will expect ‘the whole process [of making property transactions] to be online’.Footnote6 The quarterly reviews undertaken by the consultancy twentyci (2021) show that hubs have undertaken 7–8 per cent of property sales for the past two years, with the use of online agencies mostly concentrated amongst medium and lower priced properties.

Within the category of a centralising ‘hub’ there is a further distinction between intermediary businesses that advertise and organise transactions and those that take temporary ownership or occupation. The US platform Zillow has offered, for example, an ‘iBuyer’ or instant home purchasing programme for selected property. There are, however, no indications of any move towards the Zillow business model amongst UK platforms (Smith, Citation2018). Existing professional UK house buying businesses such as ZoomProperty, UKHomeBuyers or Swiftmove offer, in any case, a similar facility of cash sales for owners.

For property where sale is subject to delays, ‘property guardian’ companies such as Global Guardians, Ad Hoc Guardians and others offer an alternative form of temporary occupation, acting as a hybrid between a security firm and a lettings agent. The guardian companies acquire the property on a licence and let for rent on sub-licences of varying length at a rent that is typically less than the local going rate but with little security of tenure. They have their own websites and cross-advertise on SpareRoom and other platforms.

Given the geographically scattered and sometimes unusual character of available properties, it is difficult to see how the property guardian companies could have easily emerged as viable businesses without online platforms. In finding tenants, however, a survey of the occupants of guardian properties found that most had entered the sector through ‘word of mouth’ (Meers & Hunter, Citation2020). As is an assumption of socio-technical analysis, technology acts alongside and within the market and becomes entangled or ‘mangled’ in the realities of practice (Orlikowski, Citation2005).

Platforms as mediators

Rather than simply extending traditional market spaces, platforms also translate, rework and change the meaning of information. In part, the platforms create meaning through changing context. To give an example: Rightmove (Citation2015) reports that the busiest time of day on their website ‘is in the evening’ when people watch television whilst searching on a mobile device. Fields & Rogers (Citation2021: p. 16) suggest that platforms encourage a ‘calculative mentality’. Aspects of online data may have such implications. Mediation is not in a single direction. However, Rightmove’s comments suggest that platforms also blur the boundaries between housing search as an instrumental, contingent practice and an unstructured, discretionary and leisure-based activity.

Rightmove’s activities as an online influencer reinforce the discretionary, leisure-based aspects of housing searches. Rightmove provides examples of celebrity homes, expensive dream homes and a selection of stories showing how different individuals and families have realised their aspirations. By implication, therefore, Rightmove seeks to promote demand through encouraging people to move to more attractive and more expensive property.

Remediation

In addition, digital media rework older images and forms of expression in a process that Bolter & Grusin (Citation2000: pp. 14–15) call ‘remediation’, comprising two aspects of ‘immediacy’ (or transparency) and ‘hypermediacy’. Immediacy attempts to make the viewer or reader forget about the medium, while ‘hypermediacy’ offers a heightened sensibility, drawing attention to the medium and its workings. Google Maps and Google Street View, taken together as a technology that is commonly used in property websites, provide an example. They allow a more immediate, transparent experience of a wider neighbourhood context than can be generated by agents’ site photographs. In addition, Google Maps allows the conversion of conventional two-dimensional map images into simulated three dimensional images in a way that is not just of practical value but offers an immersive and enjoyable experience for those engaging casually in property search.

Remediation applies to statistical data as well as visual images. Platforms present statistics to draw out the immediacy of trends in house prices, by area and by dwelling type. In doing this and based on the US experience, Benites-Gambirazio (Citation2020) suggests that platforms help bring sellers and buyers in line with the realities of the market. Equally, drawing on underlying linked databases, platforms can algorithmically generate automated valuation models (AVMs), providing a range of property valuations with varying degrees of sophistication and robustness. Zoopla is distinct in making AVM estimates freely available, whereas other platforms may demand a subscription as part of their business strategy.

The sharing economy, private renting and home ownership

‘Sharing economy’ theory extends the mediating and remediating function of platforms to tenure and residential mobility. The growing use of platforms, it is suggested, mark the emergence of a more mobile, flexible economy, with ‘less stable career paths’ (Sundararajan, Citation2018). Moreover, by ‘shifting spending from physical places to digital interfaces’, the sharing economy will ‘over time’ encourage shared living and shared housing’ (ibid). Consumers will also come to question ‘ownership as a necessity for security and a fulfilling life’ (Baum, Citation2017: p. 42) so promoting renting rather than owner-occupation and, amongst renters, promoting ‘a move away from long-term leases towards a hybrid of homes and hospitality’ (Wisniewska, Citation2019). Equally, for owner-occupiers, these same trends are likely to involve a higher rate of turnover in house sales (Baum, Citation2017: 52). Claims for the sharing economy are based in part on the assumed impact of a flexible ‘gig economy’ and in part on the apparent ability of the internet to provide services independently of space and place. However, increased residential mobility would also be expected if the platforms were performative, as the main platform companies insist, in facilitating transactions.

The EHS provides data on how long occupants have been living in their present home. As shown in , the length of time fluctuates from year to year for owner-occupied housing, with an increase (and therefore a reduction in mobility) for private renters.

Table 2. Trends in residential moves in England.

The growing popularity of property searches and of platforms ( and ) has not been matched by a growing number of moves, at least not in the period up to the unique market conditions caused by both the Covid 19 lockdowns and the suspension of property sales taxes (stamp duty) in 2020 and 2021. Putting aside those unique market conditions, the growth in the number of platform visitors has mostly manifested in a growth of searches that have not proceed to the ‘functionally active’ stage of a property transaction, to use a term derived from Rae (Citation2015, 459).

Contrary to the sharing economy thesis, not all aspects of online platforms favour renting. The remediation of financial statistics helps owners envisage the value of their property. Although AVMs have limitations – they are methodological ‘black boxes’ and do not predict the future course of house prices – their existence and the ‘price paid’ data on Zoopla and other sites make value calculation more accessible and visible.

In addition, platforms enable owners to find new ways to make or supplement an income. Online equity release platforms enable homeowners to calculate how much they can borrow, given an estimate of the value of their home (for example from an AVM) and a statement of their age. Equity release has increased substantially over the past decade (ERC, Citation2021). Further, platforms enable owners to rent out their home as tourist accommodation. A survey of 2,149 respondents undertaken in October 2019 jointly by YouGov and Capital Economics suggests that 16 per cent of adults in Britain ‘have let out all or part of their property on a short-term basis over the past two years’ and that ‘most commonly they have let out their main residence’ (Evans & Osuna, Citation2020, p. 6).

Given such tendencies, the use of platforms has not undermined owner-occupation as the ideal tenure, long normalised in popular culture or promoted in government policy (Gurney, Citation1999; Smith, Citation2015). For example, according to the EHS, the proportion of private renters ‘who expect to buy’ in 2019/20 was about 59% and had hardly changed in a decade (MHCLG, Citation2020: p. 19). Private renting may still increase for affordability reasons or because of governmental support but there is no evidence of changed lifestyle expectations, as is the assumption of the sharing economy.

The EHS also provides data on numbers of households renting privately. While number of households has doubled since the early 2000s, ‘the rate has remained around 19% or 20% since 2013–14′ (MHCLG Citation2020, 6). Some care is necessary, however. The EHS provides an overview of trends in the existing housing stock and is a poor indicator of emerging trends associated with institutional build for rent. This latter has grown rapidly in the past few years, according to statistics prepared by the British Property Federation (BPF, 2021a), albeit from a small base. In Q3 of 2020, for example, new build for rent only accounted for about 5.7 per cent of all housing units given planning consent.Footnote7

Build to rent, as conceived by the BPF, is funded by institutions that have identified a new, growing source of investment income (Evans Citation2015; Nethercote Citation2020). Build to rent has attracted a dedicated online ratings site, ‘HomeView’, where tenants provide assessments of completed schemes. Further, it is promoted in the property and financial press in exactly the way that would be predicted by sharing economy theory for a target clientele of ‘footloose, job-hopping younger people [who] no longer want to be tied down to bricks-and-mortar homes’ (‘Financial Times’, 25/01/2019).

Concepts of performativity suggest that economic discourse helps create the phenomenon its explains. The sharing economy discourse is therefore performative in indicating possibilities for investment. Equally, however, the sharing economy discourse is exaggerated, given the way that the BPF (2021a) defines institutional investment as being about new build, rather than investment in the existing stock and given its small size in relation to other forms of new build. The composition of build to rent housing is, in any case, more diverse than the target clientele would suggest. Analysis undertaken by the BPF (2021 b) suggests that in London, where most institutional new build has been concentrated, the tenants of build to rent schemes have similar characteristics to those in the wider privately rented sector, except that the occupants are younger and that a higher proportion are ‘sharers’, unrelated adults living in the same accommodation.

Sharing and shared accommodation

The phenomenon of shared accommodation deserves more attention. The renting of rooms is facilitated by many platforms. Specialist renting (SpareRoom, OpenRent, companies promoting property guardianship) and tourist accommodation (Airbnb) platforms are the most prominent. Rightmove also allows searches for room renting via appropriate search terms, notably ‘shared’.

The EHS provides data on two types of sharing: two or more families living in the same property and single people sharing with others. As is shown in , sharing households remain relatively small as a proportion of the total. As a result, changes should be considered as indicative, rather than precise measures. The proportions have nevertheless grown in the privately rented sector compared to the situation in the year 2015/16 and compared to the trend in all households. The assumption of ANT is neither to prioritise technological nor socio-economic causes of change. Increased housing shortages would offer, for example, a non-technological explanation for increased sharing. Equally, however, the various room renting and other platforms make it easier to find shared accommodation.

Table 3. Trends in sharing in England.

For consumers, the implications of ‘sharing’ are differentiated and qualified. For affluent consumers, sharing platforms may facilitate labour market mobility or the purchase of a short-term holiday letting, as is a repeated theme in how the platforms, and in some cases the housing searchers (as on SpareRoom), present themselves. For others, sharing may enable new social contacts or alternative lifestyles. For example, interviews with property guardians undertaken by Ferreri & Dawson (Citation2018) suggest that residents have a polarized ‘love-hate’ relationship with their temporary home. For others still, in a context of growing economic precarity amongst young people (McKee et al., Citation2020), the information available on sharing platforms is, in principle, a means of facilitating the management of constraint, enabling the renting of a room rather than ‘sofa surfing’. In the context of housing shortages, sharing will also indicate, depending on the exact circumstances, a degree of overcrowding. Sharing, as applied to housing, therefore corresponds to the view of Jarvis (Citation2019: p. 258) as a ‘mosaic’ of multiple and contested meanings.

Regulatory and policy issues

The earliest experiments in e-commerce occurred on the West Coast of the US in a political culture that was individualistic and libertarian (Barbrook & Cameron, Citation1996). Such assumptions have persisted in the way that socio-technical researchers have sometimes conceptualised the workings and impact of e-commerce. The idea of a ‘lateral exchange market’, as presented by Perren & Kozinets (Citation2018), is, for example, based on the assumption that platforms promote trust and self-governance. The sharing economy concept likewise implies a preference for self-regulation, presented as promoting transactions of benefit to all parties.

The arguments in favour of self-regulation have been qualified by Cohen & Sundarajan (Citation2015) who, writing as sharing economy theorists, suggest that the case for self-regulation is confined to full P2P transactions and is applicable to resolving informational asymmetries rather than externalities. Informational asymmetries, including consumer protection and the avoidance of externalities are, in any case, considered in the UK under separate legislative powers and policy frameworks. Yet the comment of Cohen & Sundarajan is itself problematic. Housing is a special type of consumer good, a necessity of life where the legal protection of the rights of tenants and buyers has a long history.

Information asymmetries and consumer protection

In support of their claims, the advocates of self-regulation can point to a tendency for some old complaints to disappear or become less credible since the emergence of platforms- for example that the published marketing terminology used by estate agents is exaggerated and tendentious (Shears, Citation2009). The search facilities on many platforms typically involve standardised data categories that enable consumers to make an initial judgement based on published information. The availability of multiple photographs, indicative layouts and links to Google Maps helps consumers visualise the property at a very early stage. The availability of online information has also to some extent rendered obsolete attempts by governments to introduce mandatory seller information, such as the Home Information Pack (HIP) requirement used in England from 2007–2010 (Wilson, Citation2010) or the Home Report regime in Scotland. The relevant information is now mostly available online either at no charge or at a reduced cost (Mead Citation2018).

The efficiency gains of the past few years are not solely attributable to commercial platforms. The performativity of the property market is itself dependent on and enhanced by online public information resources, notably the Land Registry for England and Wales, its Scottish equivalent, the General Register of Sasines and the sites of local authorities. The land registries provide the official record of who owns which property and parcel of land, how much it was worth at the time of the last transaction as well as information about legal restrictions attached to a property. Local authorities websites have a similar function in providing records of town planning decisions. Online public registers are therefore instruments of public accountability and a means of reducing market uncertainty- a positive overspill to use the language of Callon (Citation2007).

Yet information asymmetries remain. Digital images may be edited to remove eyesores; and many important area characteristics – such as air pollution or contention for on-street parking - are not easily available online. Moreover, the level of detail varies between platforms. Apart from cross-listed properties, for example those originating from Onthemarket, the less expensive rental and for sale properties listed on Facebook and Gumtree contain relatively little detail or visual information. The pattern suggests, therefore, a correspondence between the uneven quality of online information and inequality in housing market position- a tendency that Boeing et al. (Citation2021) have noted in the US. The level of detail and accuracy is not necessarily worse than the alternatives to online platforms- for example, advertisements in newspapers or posted notices in local shops. However, the variations undermine any claim that the emergence of platforms might counter market inequalities. Moreover, the level of detail in a listing can never be exhaustive. Much of the accuracy of property descriptions depends on disclosure of information by the owner or landlord.

The increased availability of online information has not, in any case, led to increased satisfaction with or confidence in agents. The Property Ombudsman for England and Wales (2019; 2020) has reported an increase in formal complaints by 16% from 2017 to 2018 and by a further 20% from 2018 to 2019, although compensatory awards rose by a lesser amount (1.4% from 2018 and 2019).Footnote8 Likewise, the report of a ministerial working party (the ‘Best Report’) (MHCLG Citation2019, 9) commented that public trust with agents is low and that the basic problem remains a ‘lack of information and of market power’ amongst consumers (ibid).

Under existing legislation, the process of buying, selling or renting out property is regulated by at least three different regulators who can prohibit agents to practice if they act illegally (Conway, Citation2019). The regulatory framework is therefore complex. In addition, other than in Scotland and Wales where separate legislation has been in operation since 2018, there is no restriction on who can call themselves a property agent (Bulmer & Pickford, Citation2014). Access to the large enabling platforms is restricted to those who provide evidence that they are acting as agents. No such limitation applies to the connector platforms, Facebook Marketplace or Gumtree. Current regulatory arrangements are subject to further proposals for licencing and additional requirements for agents of all types including online ‘hub’ agents (MHCLG, 2019). The mainstream UK policy discourse rejects any idea that the growth of online information, even with a proliferation of rating sites, might enable self-regulation. Other than prescriptions against misdescription and deception, the current UK policy discourse does not extend to moderating the quality and detail of the information that owners and landlords are required to post on the web.

Negative externalities: the special case of short-term renting and multi-occupation

In relation to negative externalities, the local impact of short-term tourist accommodation on affordable rents, house prices and the character of neighbourhood is well evidenced (Evans & Osuna, Citation2020, 21). While, under existing town planning legislation, local authorities can exercise control if conversion of a property from permanent to tourist accommodation amounts to a ‘material change of use’, enforcement is discretionary. In London, following the Deregulation Act 2015, a 90-day limit is in force for the letting of a whole dwelling or flat without planning permission (Cosh, Citation2020). Unauthorised use is not always easy to identify, however. Elsewhere in the UK there is no fixed statutory time limit.

The position of the UK government has been to mitigate the impact of tourist accommodation through voluntary co-operation (Cromarty & Barton, Citation2019: p. 38). Under devolved powers, the Scottish Government (Citation2020) has, in contrast, accepted proposals to introduce a licencing requirement for the use of a dwelling for short-term accommodation, though implementation has been delayed partly by Covid 19 restrictions. Political ideology still counts therefore in determining the response to the issues created by platforms.

Apart from neighbourhood effects, sharing, room renting and multiple occupation also raise fire safety and public health concerns. Conditions in houses in multiple occupation (HMOs), including overcrowded conditions are regulated by local authorities. Enforcement involves time consuming and labour-intensive surveys and inspections and, where practice has been examined in detail (Battersby, Citation2015) enforcement is commonly undertaken reactively and pragmatically after complaints from the public or reports from other governmental agencies. However, the EHS does not provide evidence of a general deterioration of conditions in privately rented housing. For example, the number of privately rented homes in the worst condition, with ‘HHSRS category 1 hazards’ reduced by half between 2008 and 2019, with the proportion of the privately rented housing stock with such hazards falling from over 28.2 per cent to 13.2 per cent in the same period. (MHCLG, Citation2020, Annex Table 2.4 and Figure 2.7).

Moreover, even reactive enforcement can act as a deterrent. For example, the national association of guardian companies (PGPA, Citation2019) argues that current HMO regulations are inappropriate, too rigid in their application and so damage the ability of its members to provide affordable housing. As the PGPA report reveals, the existing legal frameworks for the regulation of shared housing are capable of enforcement.

Conclusions

Assessing the impact of online technology on housing markets requires an acceptance of continuities as well as change. A growing number of online searches has not, for example, been associated with an increased frequency of household moves. Moreover, contrary to claims about the emergence of a platform-based sharing economy with its preference for renting, changes in tenure preferences have not materialised. The impact of the sharing economy is specific to those platforms that offer short-term and room rentals: it is manifest in the local growth of tourist accommodation, as has been documented elsewhere and, in addition, as shown here, is apparent in the EHS through the growth of sharing households.

At this point, explanations of market stability might ignore technology in favour of the durability of expectations, the impact of economic constraints or the continuing political influence of established interest groups. A conventional explanation might also point to the constraining effect of relatively rigid legal and administrative frameworks. The distinctive contribution of ANT is to recognise that platforms act as mediators as well as intermediaries and that their mediating effects go in multiple and sometimes contradictory ways, so resulting in a differentiated pattern of impacts, including ‘misfires’ where the impact is minimal.

Platforms facilitate or promote the advantages of sharing, renting and home ownership alike. They promote a calculative mentality in transactions, through AVMs whilst also making searches a discretionary, leisure-based and enjoyable experience. The operation of platforms therefore reinforces the observation of Besbris (Citation2016: 2020) that the sales process in owner-occupied housing is an exercise in ‘romancing the home’ as well as the earlier remark of Smith & Munro (Citation2008: pp. 160–161) that ‘the emotional and the economic, the passionate and the rational come together in the workings of the housing market.’

Continuity is also apparent in the persistence of issues connected to market asymmetries and inequalities. As evidenced in the Best Report (MHCLG, 2019), political discourses have mostly been about the actions of human intermediaries, the property agents, rather than platforms and solutions have been sought in promoting the professionalisation of agents. Proposals could be taken further, with, for example, one possibility being to require online property advertisements to follow a minimal standard format.

The research agenda raised by platforms will surely cover the impacts of and potential for different forms of regulation in the context of concerns about affordability, mixed trends in housing conditions and marked local price variations. Otherwise, two broad research priorities are apparent.

First, Çalışkan & Callon (Citation2010, p. 22) suggest a continued focus on STAs as informational intermediaries- how STAs frame markets and distribute knowledge between different parties. The consociality/intermediation distinctions offer a way of classifying platform types as STAs in the UK, as this paper has shown. The classification is derived from a general classification of e-commerce and would benefit from comparisons with other countries and jurisdictions. Moreover, given that the market is recognised in ANT as a place of struggle (Çalışkan & Callon Citation2010, 3), the analysis can be taken further, through comparing the business strategies and tactics of different platform companies and their continuing relation to human intermediaries, notably property agents.

Second, for Latour (Citation2005: p. 27) the main priority concerns the processes of social group formation and, by extension therefore for housing studies, a better understanding of how different platforms are used and how this affects residential patterns and segregation. For example, which platform type is used by different age groups? To what extent do lower income individuals and families rely on platforms when searching for privately rented accommodation? Which types of platforms are favoured by landlords and for what reason? Is the use of sharing economy platforms (not just the tourist accommodation sites) in the UK confined to ‘mostly white, highly educated, able-bodied urbanites’ as stated of the US (Frenken & Schor, 2019: p. 121)? How, moreover, are the emotional or romantic aspects of the housing market mediated by different platform types in different tenures and price ranges?

Markets for ANT are the coming together of a variety of heterogeneous elements- technology, practices, the habitual expectations of users and regulatory frameworks. ANT is not the only way of disentangling these elements. Social constructivism, with which ANT has similarities, allows an analysis of how expectations arise through social interactions and persist over time. ANT, nevertheless, has strengths in cutting across the micro/macro distinction in a way that suits the analysis of platforms and, in addition, in showing the diversity of entities and actors that influence market outcomes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Barry Goodchild

Barry Goodchild is Professor (Emeritus) at Sheffield Hallam University.

Ed Ferrari

Ed Ferrari is Director of the Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research (CRESR) at Sheffield Hallam University.

Notes

1 ‘Top sites ranking for all categories in United Kingdom’, https://www.similarweb.com/top-websites/united-kingdom/ (Consulted July 2020): semrush.com. ‘Traffic Analytics’ (Retrieved July 2020)

2 Information is taken from https://trends.google.com/trends/?geo=GB (used October 2021) and then presented using EXCEL.

Google Trends does not give absolute numbers only trends measured against a peak of 100%, determined by the level of the search term ‘for sale’ in May 2021. Datapoints are every other month.

3 Figure 2 is a split graph so that the growth in for rent searches is easily apparent.

5 See the following discussions

https://propertyindustryeye.com/forums/topic/rightmove-the-invisible-weekend/

https://propertyindustryeye.com/forums/topic/if-otm-dies-can-our-industry-talk-act-collectively/

(Discussions posted 2016, 2017, 2018: Retrieved July 2020)

6 https://www.thedrum.com/news/2020/02/12/purplebricks-ceo-using-less-commisery-and-more-data-boost-its-brand-creds (Retrieved February 2020)

7 The figure is calculated by the authors from a combination of the new build for rent numbers published on the site of the BPF (https://bpf.org.uk/media/press-releases/green-light-for-record-breaking-number-of-new-build-to-rent-homes/) and the private sector housing pipeline numbers published by the Home Builders’ Federation (https://www.hbf.co.uk/documents/10691/HPL_REPORT_2020_Q3_FINAL.pdf). Both the BPF and HBF are derived from Glenigan, a construction data tracking company.

8 Property Ombudsman (2019) (2020) Annual Report 2018, Annual Report 2019 Retrieved July 2021 from https://www.tpos.co.uk/news-media-and-press-releases/reports

References

- Advantage Zoopla. (2020) ‘The tech effect’. Chapter 2 in State of the Property Nation. Available at https://advantage.zpg.co.uk/insights/reports/state-of-the-property-nation-report-2020 (retrieved May 2020).

- Barbrook, R. & Cameron, A. (1996) The Californian ideology, Science as Culture, 6, pp. 44–72.

- Battersby, S. (2015) The Challenge of Tackling Unsafe and Unhealthy Housing: Report of a Survey of Local Authorities for Karen Buck MP. Available at http://www.sabattersby.co.uk/papers.html.

- Baum, A. (2017) PropTech 3.0: The Future of Real Estate (Oxford: Said Business School, Oxford University).

- Beaulieu, A., Scharnhorst, A. & Wouters, P.(2007) Not another case study: a middle-range interrogation of ethnographic case studies in the exploration of e-science, Science, Technology, & Human Values, 32, pp. 672–692.

- Benites-Gambirazio, E. (2020) Working as a real estate agent. Bringing the clients in line with the market, Journal of Cultural Economy, 13, pp. 153–168.

- Besbris, M. (2016) Romancing the home: Emotions and the interactional creation of demand in the housing market, Socio-Economic Review, 14, pp. mww004–482.

- Besbris, M. (2020) Upsold: Real Estate Agents, Prices, and Neighborhood Inequality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

- Bessy, C. & Chauvin, P. M. (2013) The power of market intermediaries: From information to valuation processes, Valuation Studies, 1, pp. 83–117.

- Boeing, G., Besbris, M., Schachter, A. & Kuk, J. (2021) Housing search in the age of big data: Smarter cities or the same old blind spots?, Housing Policy Debate, 31, pp. 112–126.

- Boeing, G., Wegmann, J. & Jiao, J. (2020) Rental housing spot markets: How online information exchanges can supplement transacted-rents data, Journal of Planning Education and Research, first published online, 18 February.

- Bolter, J.D. & Grusin, R.A. (2000) Remediation: Understanding New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

- BPF (British Property Federation) (2021a) Green light for record-breaking number of new build-to-rent homes, Press Release, 24.

- BPF (British Property Foundation) (2021b) B. Who-Lives-in-Build-to-Rent Report (BPF, London First and UK Apartment Association).

- Bulmer, A & Pickford, L. (2014) Is it time for regulation?, RICS Property Journal, July/Aug, p. 35.

- Çalışkan, K. & Callon, M. (2010) Economization, Part 2: A research programme for the study of markets, Economy and Society, 39, pp. 1–32.

- Callon, M. ( (1998) ed.) The Laws of the Market (Oxford: Blackwell).

- Callon, M. (2007). An essay on the growing contribution of economic markets to the proliferation of the social, Theory, Culture & Society, 24, pp. 139–163.

- Callon, M. & Muniesa, F. (2005) Economic markets as calculative collective devices, Organization Studies, 26, pp. 1229–1250.

- Cocola-Gant, A. & Gago, A. (2021) Airbnb, buy-to-let investment and tourism-driven displacement: A case study in Lisbon, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 53, pp. 1671–1688.

- Cohen, M. & Sundararajan, A. (2015) Self-regulation and innovation in the peer-to-peer sharing economy, University of Chicago Law Review Online, 82, pp. 116–133.

- Conway, L. (2019) Regulation of Estate Agents. Briefing Paper No. CPB6900. House of Commons Library.

- Cosh, G. (2020) Short-term and holiday letting in London. Housing Research Note 2020/04. Greater London Authority.

- Cromarty, H. & Barton, C. (2019) The growth in short-term lettings (England). House of Commons Briefing Paper, No. 8395

- D’Adderio, L. (2011) Artifacts at the centre of routines: Performing the material turn in routines theory, Journal of Institutional Economics, 7, pp. 197–230.

- ERC (Equity Release Council) (2021) Q4 and FY 2020 equity release market statistics (press release), 28 January.

- Evans, A. & Osuna, R. (2020) The impact of short-term lets analysing the scale of Great Britain’s short-term lets sector and the wider implications for the private rented sector, Capital Economics, London.

- Evans, J. (2015) Investors bet on build-to-let for UK’s ‘generation rent, Financial Times, December 5.

- Ferreri, M. & Dawson, G. (2018) Self-precarization and the spatial imaginaries of property guardianship, Cultural Geographies, 25, pp. 425–440.

- Fields, D. & Rogers, D. (2021) Towards a critical housing studies research agenda on platform real estate, Housing, Theory and Society, 38, pp. 72–94.

- Frenken, K. & Schor, J. (2019) Putting the sharing economy into perspective. In A research agenda for sustainable consumption governance (Cheltenham, Glos: Edward Elgar Publishing).

- Gad, C. & Ribes, D. (2014) The conceptual and the empirical in science and technology studies, Science, Technology, & Human Values, 39, pp. 183–191.

- Gurney, C. (1999) Pride and prejudice: Discourses of normalisation in public and private accounts of home ownership, Housing Studies, 14, pp. 163–183.

- Jacobs, K. & Manzi, T. (2000) Evaluating the social constructionist paradigm in housing research, Housing, Theory and Society, 17, pp. 35–42.

- Jarvis, H. (2019) Sharing, togetherness and intentional degrowth, Progress in Human Geography, 43, pp. 256–275.

- Keith, E. (2020) 6 Reasons Google and Facebook Haven’t Eaten Portals’ Dinner Yet. Property Watch Portal, May 21.

- Keith, E. (2021) Is Rightmove’s Crown Slipping? – An Online Marketplaces Deep Dive. Online Marketplaces, April 8.

- Latour, B. (1996) On actor-network theory: A few clarifications, Soziale Welt, 47, pp. 369–381.

- Latour, B. (2005) Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory (New York: Oxford University Press).

- McKee, K., Soaita, A.M. & Hoolachan, J. (2020) Generation rent’ and the emotions of private renting: Self-worth, status and insecurity amongst low-income renters, Housing Studies, 35, pp. 1468–1487.

- Mead, E. (2018) Agent Provocateur: Has the time come to rethink Home Information Packs?. Property Industry Eye March 5.

- Meers, J. & Hunter, C. (2020) The face of property guardianship: Online property advertisements, categorical identity and googling your next home, People, Place and Policy, 14, pp. 142–156.

- Merton, R.K. (1968) Social Theory and Social Structures (New York: Macmillan).

- MHCLG (Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government) ( 2019) Regulation of Property Agents: Working Group Final Report London, MCHLG.

- MHCLG (2020) English Housing Survey Headline Report, 2019-2020 (London, MHCLG).

- Montalban, M., Frigant, V. & Jullien, B. (2019) Platform economy as a new form of capitalism: A Régulationist Research Programme, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 43, pp. 805–824.

- Musterd, S., Marcińczak, S., van Ham, M. & Tammaru, T. (2017) Socioeconomic segregation in european capital cities. Increasing separation between poor and rich, Urban Geography, 38, pp. 1062–1083.

- Nethercote, M. (2020) Build-to-rent and the financialization of rental housing: Future research directions, Housing Studies, 35, pp. 839–874.

- Oakley, P.(2018) Can anything stop the Rightmove juggernaut? Investors Chronicle, December 5.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) (2019) An Introduction to Online Platforms and Their Role in the Digital Transformation (Paris: OECD Publishing).

- ONS (Office of National Statistics) (2017) The feasibility of measuring the sharing economy: November 2017 progress update. ONS Article 9 November.

- Orlikowski, W.J. (2005) Material works: Exploring the situated entanglement of technological performativity and human agency, Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems, 17, pp. 6.

- Orlikowski, W.J. (2010) Practice in research: Phenomenon, perspective and philosophy, Cambridge Handbook of Strategy as Practice, 2, pp. 23–33.

- Perren, R. & Kozinets, R.V. (2018) Lateral exchange markets: How social platforms operate in a networked economy, Journal of Marketing, 82, pp. 20–36.

- PGPA (Property Guardian Providers Association) (2019) Review of the Year 2019 December 19.

- Piketty, T. (2014) Capital in the Twenty-First Century (A Goldhammer, Trans) (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press).

- Rae, A. (2015) Online housing search and the geography of submarkets, Housing Studies, 30, pp. 453–472.

- Rightmove (2015) 5 simple ways to make a big impact on mobile Rightmove Report, June 19.

- Rowley, J. (2005) The evolution of internet business strategy, Property Management, 23, pp. 217–226.

- Scottish Government (2020) Short-Term Lets – Licensing Scheme and Planning Control Areas: Consultation Analysis (Edinburgh: Scottish Government).

- Sharam, A. & Bryant, L. (2017) The uberisation of housing markets: Putting theory into practice, Property Management, 35, pp. 202–216.

- Shaw, J. (2020) Platform real estate: Theory and practice of new urban real estate markets, Urban Geography, 41, pp. 1037–1064.

- Shears, P. (2009) Hang your shingle and carry on: estate agents–the unlicensed UK profession, Property Management, 27, pp. 191–211.

- Smith, P.(2018) Opinion piece: Will UK portals follow the zillow model and start buying and flipping homes?,’ Property Eye Industry, 15 June.

- Smith, S. J. (2015) Owner occupation: At home in a spatial, financial paradox, International Journal of Housing Policy, 15, pp. 61–83.

- Smith, S. J. & Munro, M. (2008) Guest editorial: The microstructures of housing markets, Housing Studies, 23, pp. 159–162.

- Smith, S. J., Munro, M. & Christie, H. (2006) Performing (housing) markets, Urban Studies, 43, pp. 81–98.

- Stabrowski, F. (2017) People as businesses’: Airbnb and urban micro-entrepreneurialism in New York City, Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 10, pp. 327–347.

- Stigler, G.J. (1961) The economics of information, Journal of Political Economy, 69, pp. 213–225.

- Sundararajan, A. (2017) The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

- Sundararajan, A. (2018) How the Sharing Economy Could Transform the US Housing Market Freddie Mac, June.

- twentyci (2021) Property & Homemover Report Q1 2021, 20 April.

- Wachsmuth, D. & Weisler, A. (2018) Airbnb and the rent gap: Gentrification through the sharing economy, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 50, pp. 1147–1170.

- Wilson, W. (2010) Home Information Packs: a short history. Research Paper 10/69 (London: House of Commons Library).

- Wisniewska, A. (2019) Property in the 2020s Financial Times, October 18.