Abstract

The Covid-19 pandemic has demonstrated the fundamental importance of secure, affordable and quality housing. However, it has also revealed the precariousness of housing for many and how pre-existing inequalities have been amplified by a global health emergency. The private rental sector has long been considered a precarious tenure, owing to weaker regulation, the temporary leases and a power imbalance between the rights of tenants and the interests of landlords. This article mobilises the concept of precarity to explore the lived experiences of tenants navigating Ireland’s rental sector, the challenges they face regarding housing affordability, security, quality and accessibility, and the ways the pandemic has intensified their experience of housing precarity. The research is operationalised through 28 interviews with renters from Dublin’s inner-city, suburbs and commuter belt. The concept of precarity captures the economic importance of housing for financial well-being and security, as well as the non-economic functions of home as an emotional conduit for belonging, ontological security and mental health.

Introduction

The fundamental importance of housing for financial and emotional well-being has been revealed by the Covid-19 pandemic. Never before has the message to remain at home and restrict social interactions been such a matter of life and death, as health authorities grapple with a virus that has claimed over 5 million lives (WHO, 2021). The home has literally become a refuge as people restrict their movements, work from home and isolate the most vulnerable to limit the impact of the virus. In such circumstances, the centrality of housing for maintaining individuals’ economic security has been made clear, as have the non-economic functions of home, particularly its role as a spatial and emotional conduit for belonging, intimacy and exchange, and for the maintenance of individual well-being, ontological security and health.

As the ‘home front’ has become the ‘new front line’ in the public health response (Gurney, Citation2020), concerns about the increasingly precarious nature of working and living conditions for renting households have emerged and how these might be exacerbated by the pandemic. Restrictions on travel and working have impacted through job losses and income reductions, which have affected tenants’ ability to make their rental payments, and rent arrears rates have risen as a result (Parrott and Zandi, Citation2021, Shelter, Citation2021). The prospect of evictions has raised new concerns over housing displacement and overcrowding, the ability of households to access rental housing in the context of public health restrictions and the potential of such movement on virus transmission rates. The emphasis on self-isolation and home working have placed new demands on individuals, raising questions about housing quality, the adequacy of internal environments and provision of space and amenities (Ahmad et al., Citation2020). Enforced isolation and the ability to engage in home making are likely to have affected individuals’ physical and mental health.

The private rental sector is often considered the most precarious of housing tenures, characterised by an inherent power imbalance between tenants and landlords, weaker regulation and the temporary nature of leases (Byrne and McArdle, Citation2022). Before the pandemic private renters were often those most exposed to issues of housing unaffordability and insecurity (Soaita et al., Citation2020). The last decade has witnessed a major expansion in the rental sector across advanced economies, including the UK (Ronald and Kadi, Citation2018), Australia (Hulse and Yates, Citation2017), Spain (Fuster et al., Citation2019) and Ireland (Waldron, Citation2021), where issues of high rents, evictions and overcrowding have become major political concerns. However, while the structural conditions shaping the growth of the private rental sector are increasingly understood, research has focused less on the psycho-social dimensions of this shift and how renters experience the various dimensions of housing precarity (McKee et al., Citation2020).

This article contributes to literature on the private rental sector in two ways. Firstly, it demonstrates the value of precarity as a concept to capture renters’ multiple and overlapping experiences of difficult housing conditions, while exploring how these issues intersect with other employment and welfare vulnerabilities. This approach allows deeper investigation of the emotive and affective implications of renters’ experiences, as expressed in their own self-understanding. Secondly, the article contributes to emergent literature on the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic on renters (Soaita, Citation2021, Preece et al., Citation2021), and how this has amplified pre-existing precarities regarding affordability, tenure security, the quality and accessibility of accommodation.

The research takes the case of Ireland, and specifically Dublin, as its focus, which has been an exemplar for international comparison, owing to the extent and speed of the shift toward the private rental sector (Waldron, Citation2021). Despite its rapid growth, the Irish rental sector has been characterised by a pernicious affordability crisis, as well as long-standing issues regarding security of tenure and an imbalance between the rights of tenants and landlords (Sirr, Citation2014). These challenges have likely been exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, although systematically recorded data on rent arrears levels are unavailable. To operationalise the research, twenty-eight interviews were conducted with tenants from Dublin’s inner city, suburbs and commuter belt, thereby ensuring a wide spectrum of renters’ viewpoints. These interviews explored renters’ housing histories, their understanding of multiple dimensions of precarity, as well as the confounding impacts of the pandemic. Before discussing the findings, the following section locates the research within the relevant debates regarding precarity and the rental sector, before reviewing the methodological and analytical approaches used to interrogate the interview data. Finally, some broad conclusions are drawn in relation to the results and their implications for theory and policy.

The private rental sector: from precarity to the pandemic

As articulated by McKee et al (Citation2017), the concept of precarity originated within the field of labour studies to describe the risks arising from the spread of greater labour market flexibility, employment insecurity, low incomes and a weakening of social welfare provision (Kalleberg, Citation2009). This growth of precarious work in Europe and North America lies in response to the neoliberalization and financialization of economies from the 1980s and the privatization of risk that accompanied these transformations as the costs and responsibilities for risk were shifted from employers to workers (Vosko, Citation2006). Precarious working is evident in many forms, including low wage work, the casualisation of contracts, as well as uncertain working hours and frequency of pay, and has become a more permanent fixture within labour markets (Pembroke, Citation2018). For Standing (Citation2014), such conditions have created a new class of the ‘precariat,’ a large group united by conditions of vulnerability and multiple degrees of social exclusion, who experience fewer certainties regarding work, income and housing (Lombard, Citation2021). However, precarity also cuts across traditional class distinctions and markers of social position, like income, employment status and education and individuals can experience precariousness even if they are well educated and in employment (McKee et al., Citation2017). In short, the concept of precarity captures the distribution of risks within society and explores how an individual’s exposure to adverse events might be amplified by their economic and social circumstances (Clair et al., Citation2019).

Precarious working and living conditions are acknowledged to negatively impact on individual wellbeing, especially for vulnerable groups within society (Bentley et al., Citation2019). Indeed, the fear of losing one’s job or home can negatively impact ontological security, or the stable psychological basis that underpins one’s self-confidence in the trajectory of their lifecourse. Such an erosion of stability contributes negatively to subjective wellbeing and mental health, as well as to one’s sense of identity and social relations (Lombard, Citation2021). Such effects can leach into other domains of a person’s life, causing them to live in an atmosphere of anxiety and fear that can hinder their efforts to engage in constructive life planning (Huisman and Mulder, Citation2020). Indeed, individuals may experience multiple and over-lapping dimensions of precarity, where one form of precarity (e.g. labour insecurity) might aggravate other aspects of one’s experience (e.g. eviction from home). Indeed, the utility of precarity as a concept lies in its ability to disentangle these multiple and overlapping elements of an individual’s experiences of labour, housing, welfare status and immigration.

Increasingly, the concept of precarity has been mobilised within the sphere of housing research (McKee et al., Citation2020). Clair et al (Citation2019, 16) specifically define housing precariousness as a “state of uncertainty which increases a person’s real or perceived likelihood of experiencing an adverse event, caused by their relationship with their housing provider, the physical qualities, affordability, security of their home and access to services.” Housing affordability is a key driver of precarity, where high housing costs push a household below the poverty line, limiting their participation in economic and social life. Housing quality can impact individuals’ physical and mental health, particularly through issues of overcrowding, insufficient light, damp, poor ventilation and facilities (Baker et al., Citation2016). Security is a crucial dimension of precarity, including the contractual security of leases and the ontological security of controlling one’s personal space and the confidence in one’s lifecourse to deal with everyday experiences (Hulse and Milligan, Citation2014). Housing accessibility refers to securing an appropriate home relative to one’s needs, that is adequately served by amenities and facilities.

Within housing debates, private renting has long been considered a precarious tenure, owing to the temporary nature of leases, the power imbalance between the rights of tenants and the interests of landlords and the weaker nature of regulations (Soaita et al., Citation2020). Following the global financial crisis, the private rental sector has witnessed exceptional growth as younger households are locked out of the wealth enhancing effects of homeownership by high prices and restrictive lending. In England, the ownership rate amongst under 35 year olds dropped from 50% to 29% between 2003 and 2015, while the renting rate expanded from 27% to 50% (Ronald, Citation2018). This dramatic shift has been fuelled by the aggressive entry of investors into rental housing (Waldron, Citation2018), permissive rental regulations and diminished public housing provision (Chisholm et al., Citation2020), which have fuelled new affordability crises. The rental sector is often characterised by poorer quality accommodation, minimal security and high levels of financial stress amongst tenants (Soaita et al., Citation2020). Renters’ experiences are often bound up in wider precarities relating to employment, lower incomes and the rise of the gig economy which can have a range of economic, social and health impacts (Fuster et al., Citation2019).

Certain renters are more vulnerable to housing precarity, including those on low-incomes, lone parents, migrants, the unemployment, students and elderly (Soaita et al., Citation2020). Rent can be a considerable financial burden, sometimes necessitating choices between making rent payments and providing for families (Smith et al., Citation2014). Some struggle with debt management and borrowing to cover deposits, rent payments and day-to-day living costs. Unsustainable rents can lead to undesired overcrowding, resulting in discomfort, lack of personal space and privacy (Soaita and McKee, Citation2019). Economic evictions through unanticipated rent increases are a real threat, and the stress and expense of finding affordable accommodation can be dramatic. Forced relocations can be difficult for children, leading to the loss of social networks, disrupted schooling and impacts upon well-being (Desmond, Citation2016). Friends and family often provide economic support, which can feed into a diminished sense of independence and self-worth (Hoolachan and McKee, Citation2019). Older renters are vulnerable to affordability issues, particularly if rents are paid from pensions, or if they have been forced into renting through life events, like divorce, bankruptcy or illness (Morris, Citation2013).

The contractual and legal conditions of tenants vary markedly by jurisdiction. Indeed, market-led housing systems, like those found in Anglo-Saxon countries, are often characterised by weak protections, limited duration contracts and few restrictions on rent setting (Ronald and Kadi, Citation2018). Short-term leases are problematic for families, who are less flexible and mobile due to the presence of children and for whom finding accommodation at short notice can be a financial and emotional strain (Desmond, Citation2016). The weakness of regulation around rent setting is a profound insecurity, while landlords can upend a tenant’s life by exercising their economic interests; for example, by executing a ‘no fault eviction’ under a number of grounds (e.g. to sell or refurbish the property).

Landlords exert considerable influence over tenants’ lives, restricting their homemaking activities such as decorating, having pets or social gatherings. Landlords’ biases often mitigate against migrants and lower-income renters in receipt of rent subsidies (Lombard, Citation2021). The unresponsiveness of landlords to maintenance requests is an oft quoted frustration, particularly when tenants pay high rents for a poor-quality service. Descriptions of poor quality accommodation abound, particularly regarding mould, infestations, damp and poor ventilation (McKee et al., Citation2020). Yet, tenants often refrain from seeking repairs over fears of rent reprisals, the termination of a tenancy and the costs of finding another property (Chisholm et al., Citation2020). Literature also reports abusive landlord practices, including the withholding of deposits, unannounced inspections or illegal rent increases (Byrne and McArdle, Citation2022).

While research on the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on renters is tentative, the foregoing illustrates how vulnerable renters face a suite of inequalities that may be amplified by the pandemic (Horne et al., Citation2020). Unemployment and income cuts resulting from working restrictions are impacting renters’ ability to make payments, leading to concerns of arrears, debt and evictions. In England, 445,000 renters were in arrears as of December 2020 (Shelter, Citation2021), while in the US one-in-six renters were behind on rent payments and at risk of eviction (Parrott and Zandi, Citation2021). Evidence from Australia suggests that almost one-third of renters reported difficulties with paying rent and bills, or went without meals during the pandemic (Baker et al., Citation2020). In the UK, Soaita (Citation2021) reports 24% of renters have experienced income reductions, while 22% of renters had limited savings to fall back, compared to just 16% and 11% of mortgagors respectively. While numerous jurisdictions imposed eviction moratoria and rent relief early in the crisis, as society moves toward normalisation such conditions create the potential for increasing evictions, which may affect renters’ ability to access credit or other rental properties (Simcock, Citation2020).

As lockdowns have forced people to work from home, a premium has been placed on the quality of internal environments, space and storage. Yet, the home is often not equipped as an office, which may impact workers’ physical and mental health. A lack of a workstation, overcrowding and disruptive events (e.g. from children or housemates) may limit an individual’s ability to complete work privately, as well as blurring the lines between work and home life (Green et al., Citation2020). In a UK study of housing conditions during the pandemic, Brown et al (Citation2020) found issues of incomplete maintenance, landlords’ refusals to complete repairs, overcrowding and additional heating costs, which had considerable impacts on tenants’ quality of life. As individuals spend more time in internal environments with mould, poor ventilation and daylight, there are likely to be significant health impacts (Ahmad et al., Citation2020). Overcrowding can lead to increased virus transmission and has been linked to higher mortality rates, particularly among minorities (Public Health England, Citation2020). Such confinement, overcrowding and sedentary behaviour has been linked to a worsening of mental health disorders such as anxiety, depression, and developmental issues in children (Amerio et al., Citation2020).

Methodology

Case selection and Ireland’s private rental sector

The expansion in Ireland’s private rental sector has been driven by economic, policy and political factors. Firstly, rebounding property values following the last crash, a restricted lending environment and population growth have fuelled housing demand and prices, while deflecting younger, lower income households into the rental sector (Waldron, Citation2021). The rate of homeownership has declined from 80% in 1991 to just 68% in 2016 (CSO, Citation2021b). Secondly, there has been a retraction in state support for social housing construction, as exchequer funding fell from €1.4 billion to €167 million between 2008 and 2014. Thirdly, Government policy accommodates social housing need by subsidising private market rents and spending on the State’s primary subsidy, the Housing Assistance Payment or HAPFootnote1, has ballooned from €23 m in 2015 to €480 m in 2020 (DoHPLG, Citation2021). Finally, the State has incentivised institutional investors into the rental market. Property assets that were temporarily nationalised in a State backed ‘bad bank’ following the financial crisis have been sold to a coterie of financial funds at fire sale prices. A highly facilitative capital gains tax regime and new investment structures were also established to attract investors (Waldron, Citation2018).

The growth of private renting has been most evident in Dublin, where the homeownership rate has fallen to just 60% and 25% of households are private renters. Yet, amongst the under 35 age cohort the ownership rate has collapsed to 22%, while the share of those renting has surged to 60% (CSO, Citation2021b). Such demand, coupled with a prolonged shortfall in supply, has fuelled an affordability crisis. Average Dublin rents rose by 49% between 2014 and 2020 (from €1,057 to €1,574), yet average earnings increased by just 9% (€44,829 to €48,946) (CSO, Citation2021a). Waldron (Citation2021) found that 36% of renters experienced difficulty or great difficulty in making ends meet, while 62% would be unable to meet unexpected expenses from their current financial resources. Such pressures have resulted in a severe housing crisis, one marked by elevated levels of overcrowding, evictions and homelessness (Waldron et al., Citation2019).

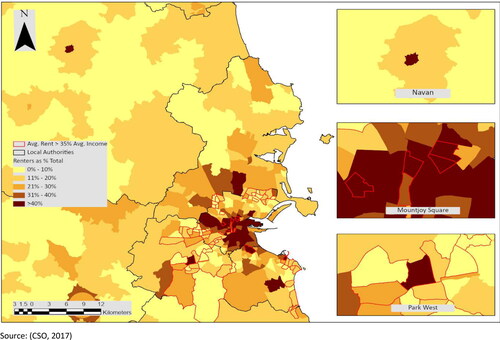

An area-based approach identified Dublin neighbourhoods with high concentrations of renters and strong rent inflation between 2014 and 2020. Mapping of Census data identified three locations where more than 40% of total households rented privately and where average rents exceeded 35% of average local incomes (). Mountjoy Square is an historic, inner-city neighbourhood formerly composed of low-income housing that is undergoing rapid gentrification. Between 2014 and 2020, rents for an average 2-bedroom property increased by 47% and demand is driven by its proximity to the Dublin Docklands, Ireland’s main financial/technology hub. Park West is a suburban neighbourhood 10 km west of Dublin City Centre. The area experienced significant development during the property bubble of the 2000s and average rents for a 2-bedroom property increased by 43%. Navan is a commuter town located 55 km northwest of Dublin City. The number of renting households increased by 160% between 2006 and 2016, which has fuelled a 73% increase in the cost of renting a three-bedroom property.

Qualitative approach

The locations of residential buildings in each neighbourhood were mapped using a shapefile provided by Ordnance Survey Ireland. This map was reviewed against the national postal service’s online address database and a random selection of 200 addresses were extracted using excel from each area. As it was impossible to ascertain the tenure of households in advance, a high attrition rate was expected. Interview request letters were posted to residents living within apartment complexes, due to difficulties in gaining access to buildings, while letters were hand delivered to houses. In total, 28 responses were achieved: 10 from Mountjoy Square, 8 from Park West and 10 from Navan. This return is appropriate as Mason’s (Citation2010) survey of 2,533 qualitative studies found that the most common sample sizes were between 20 and 30.

demonstrates the sample was largely balanced in terms of gender, while most respondents were either single renters or couples without children, as reflected in the national population. Half of the sample were migrant renters, including respondents from Spain, Algeria, Nigeria, Mongolia, Brazil, Poland and Hungary. The sample was under-represented among couples with children and over-represented among households sharing with non-related persons. More respondents lived in apartments than houses, though this can be expected from the types of neighbourhoods targeted in the inner-city and suburbs. Most respondents rented from individual landlords, while one-third rented properties from letting agents and a smaller proportion rented from corporate landlords. Most properties in the inner-city and suburbs were one and two bed apartments, while three or four bed houses were more common in the commuter belt. Most respondents had rented their current property for more than three years (43%), while 25% were within the first year of their current lease. The average rent paid by tenants was reflective of average rents in each location.

Table 1. Profile of interview participants.

The research was operationalised through online semi-structured interviews to avoid unnecessary social contact. Interviews were completed between August 2020 and January 2021 and the duration ranged from 37 minutes to 1 hour and 38 minutes. The themes covered included the tenant’s renting history; their reasons for moving to their current property; their perceptions of issues regarding rental affordability, accessibility, security and quality; as well as reflections on the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on their lives. Respondents were informed that interviews would be digitally recorded, transcribed and subjected to a detailed coding process using NVIVO software. These codes were developed around the four dimensions of housing precarity as devised by Clair et al (Citation2019). Common themes emerging from the data were extracted and subjected to additional scrutiny, the results of which are presented in the following section.

Renters’ experience of housing precarity

Accessibility

The lack of control suggested by housing precarity is identified within respondents’ experiences of the inaccessibility of rental accommodation (Preece et al., Citation2019). Renters not only struggle to find suitable accommodation, but also must contend with landlords’ highly selective tenant criteria, which can impact upon one’s self-esteem and well-being. Fifteen respondents referenced the severe supply-demand imbalance in Dublin’s rental market, where demand has been driven by economic and demographic growth, yet the supply of rental homes (both new and existing) has fallen to its lowest level since 2006 (Lyons, Citation2021). Where new supply is forthcoming, it has tended to be for high-end apartments or purpose-built student accommodation developed by institutional investors, which participants referenced was beyond their means. Participants reported the financial burden, time and emotional stress of finding accommodation, often scouring property websites, making multiple contacts to landlords and queueing for hours at property viewings, which they found mentally exhausting. Ten respondents reflected their experiences of upset when forced to outbid other renters and the dejection that came with being refused a property. The findings demonstrate how the screening process of landlords, and the lack of transparency involved in such processes, can lead to intense feelings of judgement that prospective renters sometimes internalise as a personal rejection.

“…there’s not much choice in the rental market, so you kind of take what you can get and if you get something good, you’re lucky. And if you’re not you just have to take what’s available…Unless you’ve loads of money and you’re kind of in that kind of like luxury premium space.” (Emma, Inner-City, House Share)

“I had to go through more viewings, and it is not pleasant to have go and take part in casting and you either get accepted or not. And you received a couple of rejections and it just, it feels, you know, it does not feel great.” (Michal, Inner City, Couple)

The accessibility dimension of precarity reveals tenants’ lack of agency within especially tight rental markets and the performative practices tenants must engage in to appeal to landlords (Power and Gillon, Citation2020). Six respondents expressly discussed the emotional strain of accessing accommodation and the pressure to perform as the ‘ideal tenant,’ which some found a demeaning exercise. Clearly, the ability to pay was linked to the performance of the ideal tenant, with respondents having to emphasise their security of income and employment, and their ability to pay rent on time. Respondents emphasised how their rental payment was the first line item in their monthly budgets, which sometimes meant they periodically had to cut back on discretionary spending or juggle bills (e.g. heat). Respondents discussed how they would prepare themselves before viewings, presenting themselves as professionals, brining cvs, references, evidence of employment and income to viewings to secure a rental agreement immediately if possible. The performance of the ‘ideal tenant’ was emphasised in projecting their ‘responsible’ nature to landlords, and their willingness to provide ‘stewardship’ of the landlord’s property. This involved convincing landlords that their property would be cared for, with tenants undertaking minor repairs and maintenance or volunteering additional access to landlords to conduct inspections, thereby emphasising their desirability as a tenant.

“I was kind of really trying to be like charming and lovely and professional and nice, because you’re doing this performance to be like I’m the ideal tenant. Like I can pay my way… you put this pressure on yourself to perform to be appealing to landlords and estate agents, which is ridiculous.” (Emma, Inner-City, House Share)

In specific reference to the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on the supply of rental properties, five respondents felt supply was improving in the short-term, as landlords converted Air BnB lettings to long-term rental units and as migrants and younger adults returned to their home countries or parental homes, which had freed up existing rental stock. Some felt the pandemic could yield positive benefits by normalising home working, thereby enhancing the attractiveness of renting in cheaper locations further from metropolitan cores. However, interviewees also felt landlords were adapting to these changing market conditions. Some identified the introduction of shorter leases (i.e. six months), which they felt landlords had introduced to manage the short-term dip in rental values, after which they would revert to pre-pandemic rents. Others felt that landlords were manipulating asking rents during the pandemic by setting artificially high rental values, so as to minimise the deflationary effects of the pandemic. This would ensure that any future rent increases or negotiations to the extension of leases would be determined from the inflated headline rent; a point subsequently confirmed through journalistic reporting (Woods and Cooney, Citation2021).

“When I was looking for this…I saw a lot of six-month leases … I think maybe the market dipped a little bit, so they’re like Ok, we’ll find someone for six months and then we push the rent.” (Ravi, Single, Inner City)

“…we look at the market prices and we feel that it’s manipulated… here in [building name] you pay €1500-ish and there’s one advertisement which went for €1900 for 2 bedrooms and it’s up for three months!” (Tobias, Suburban, Couple)

The interviews further revealed the gendered, racial and ageist dimensions of housing precarity and how discriminatory practices arose from landlords’ subjective interpretations of what separates ‘good’ and ‘risky’ tenants (Power and Gillon, Citation2020). Landlords not only make judgements on prospective renters’ ability to pay for and maintain a property, but also by proxy markers of tenant risk, including households with children, social welfare recipients and young people (Hulse and Milligan, Citation2014, Hulse et al., Citation2011). Eight respondents felt landlords avoided letting to families because of perceived difficulties in evicting households with children and additional maintenance costs. Three respondents felt migrants were more likely to experience discrimination, indicating landlords preferred letting properties to those with English or Irish names. Students were also deemed less desirable, owing to perceived anti-social behaviour or irresponsibility in maintaining properties. Grace discussed the challenges in convincing landlords to let properties to those in receipt of rent subsidies, which oftentimes required the rehearsing of explanations of how the subsidy worked and why it would guarantee their payments. In summary, renters’ experiences of the accessibility dimension of housing precarity are shaped by their lack of agency relative to landlords and the biases and discriminatory practices of landlords, which exacerbate tenants’ insecurity and fears of accessing accommodation (McKee et al., Citation2020).

“… ethnicity is also a problem… Will not prefer Polish people, will not prefer Indians, will not prefer different peoples…” (Danesh, Suburban, House Share)

“… the HAP payments as well…. A lot of landlords wouldn’t be too keen. Not that I even got a chance to tell… but I nearly had a sales pitch in my head on how to explain… there was definitely a stigma attached to it” (Grace, Suburban, Lone Parent, HAP Recipient)

Affordability

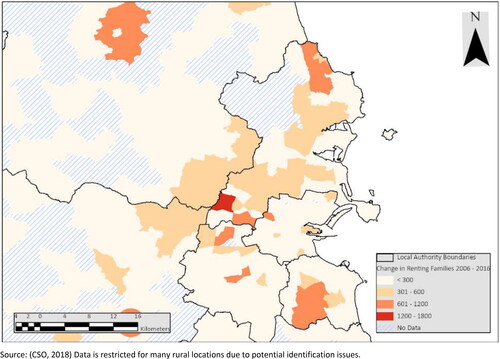

The affordability dimension of precarity generates strong negative experiences, impacting tenants’ quality of life in terms of financial stress, reduced saving capacity and limiting their ability to participate fully in social life. Furthermore, the experience of housing precarity must be understood in relation to broader employment and financial uncertainties, which were amplified during the Covid-19 pandemic (Brown et al., Citation2020). Under the ‘Planning and Development Act 2000,’ a household demonstrates an affordability problem when their housing payments exceed one-third of their income. The rents of 39% of participants exceeded this threshold, while 36% spent about one-third of their income on rent. Some 25% indicated their rent payments were a ‘Heavy Burden,’ while 43% stated rent was ‘Something of a Burden.’ Reflecting Hulse and Yates’ (Citation2017) work, there is a spatial dimension to the experience of housing precarity, with greater pressures evident in the suburbs. Half of suburban renters spent more than one-third of their income on rent and 38% felt their rent was a heavy burden. Interestingly, suburban renters were more likely to be families, reflecting the additional financial costs imposed by children. Recent years has witnessed a spatial deflection of renting families to the western suburbs (), and eleven respondents recognised that exorbitant city-centre rents, tight supply conditions and the draw of larger properties were pushing renters to the suburbs and the commuter belt. Two respondents reflected on how this impacted their quality of life, as they trade-off long commuting times and costs against lower rents in non-metropolitan areas. The affordability dimension of housing precarity is not only bound up in wider income and wealth inequalities, but also spatial processes of urban change and displacement.

“… I do the trek by commute from Navan to Dublin which is 3 hours every single day… it does have an effect on your quality of life….” (Elaine, Commuter Belt, Single)

Renters’ perceptions of market insecurity are shaped by their experiences of the regulatory structure of the rental market and the inflationary actions of landlords (Byrne and McArdle, Citation2022). Ten respondents specifically commented on the short nature of leases in Ireland and how the consistent turnover in tenancies maintains an upward pressure on rent reviews. Indeed, tenants discussed the anxieties they felt as their lease renewal dates came into view and how they would manage anticipated rent increases. In the context of Covid-19, Tobias elaborated on how his letting agent had pressurised him to commit to a lease renewal months in advance of his deadline, thereby locking him into a higher rent at a time when wider rental values were falling. Indeed, the inflationary actions of letting agents in setting higher rents were discussed by four respondents. As such agents typically charge 5%-8% of the annual rental income, they are incentivised to generate higher fees by maintaining high returns for clients. Hence, tenants’ perception of the affordability dimension of precarity is very much shaped by their powerlessness relative to the market setting actions of landlords and their agents.

“Every time the renewal comes, they raise and we never get anything for it…we’re dreading the moment when we get the (renewal) letter, because we are pretty sure that especially now with covid raging that the prices are manipulated…in May we got a letter from them that the lease is up for renewal and the rate you pay will be €1600 effective from the end of October and sign it now!” (Tobias, Suburban, Couple)

“Until 2018 we were paying same price. But suddenly like they increase €200 and then €200 again in two years. So if you see it’s their monopoly… the owner’s management company they’re like responsible for this price inflation…” (Danesh, Suburban, House Share)

Low-income tenants are often those most exposed to affordability concerns, as they tend to exhibit more limited financial reserves, more precarious employment and feature more prominently in economic sectors affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, like retail and hospitality (Byrne, Citation2021). Interviewees discussed their experiences of rental affordability during the pandemic in both financial and emotional terms. Nine respondents discussed the challenge of maintaining rent commitments and spending on household consumption, sometimes having to juggle bills or cutting back on spending. Some described having to engage in exhausting mental budgeting as they tried to ensure their rental payments were prioritised. For some, such spending restrictions were minor or temporary inconveniences, such as foregoing socialising, while for others cutbacks represented more serious curtailments, such as an inability to save or invest in pension planning, which might erode their ability to cope with future economic shocks. Indeed, two respondents elaborated on the challenges their limited financial reserves provoked, sometimes necessitating borrowing from family or friends to meet unexpected expenses. Clearly, the mobilisation of intergenerational resources is a key mechanism for some renters to cope with affordability challenges (Hoolachan and McKee, Citation2019). However, such responses are not without their limitations, including a diminished sense of adulthood as well as the burden of loan repayment, which could provoke familial tensions or guilt as adult children rely on parental financial support.

“…just left with the bare minimum…when it comes to holidays and stuff like that you’re going ‘Jesus, how are you going to save for something like that.’ (Eabha, Commuter, Couple)

“…if something happens, I have no money for like emergency expenses…I would be able to ask my partner or my parents for help” (Michal, Inner-City, Couple)

“…well, I wasn’t starting a pension. I wasn’t putting money into my pension because it’s money I kinda need to be able to pay rent and bills .” (Aoife, Suburban, House Share)

Reflecting Soaita’s (Citation2021) findings, participants’ perceptions of housing precarity were influenced by their experiences of labour market precarity during the pandemic. Renters employed in higher income occupations, such as those in the financial or tech sectors, or front-line workers (nurses of police officers) maintained their employment and income. However, workers employed in sectors more vulnerable to lockdowns and mobility restrictions were impacted to a greater degree. Among the sample, twenty-four participants managed to continue working full time from home, while four were impacted by job losses and two others were affected by temporary wage reductions. These workers could avail of the State’s ‘Pandemic Unemployment Payment,’ which provided a benefit of up to €350 per week. Hence, most respondents continued to make rental payments during the pandemic. For those who fell behind on rent payments, three were offered deferred payments by their landlords. Despite this, some reported significant stress in worrying about their rent and how the loss of employment had been a shock for them, or their housemates. In two cases, housemates had returned to their family home to avoid paying rent, resulting in the remaining tenants letting rooms in the midst of the pandemic.

“I was unable to pay it in full for the first month, so he offered to cut it in half… I pay €50 extra every month and pay him back” (Eabha, Commuter, Couple)

“One of my roommates is doing a PhD. She lost teaching hours. She lost exam invigilation… already obviously doing a PhD like the salary like is financially challenging” (Emma, Inner City, House Share)

“… we had a room that was free for two months and we honestly couldn’t actually fill it… they didn’t need to be in the city anymore” (Margaret, Inner City, House Share)

Participants expressed frustration toward the State’s response to the affordability crisis. The flagship policy since 2016 has been an area-based approach involving Rent Pressure Zones (RPZs), where annual rent increases are capped at 4%. RPZs now cover all major urban areas and 70% of tenancies are located in an RPZ (RTB, Citation2020). However, criticisms have been noted regarding a lack of enforcement of RPZ rules and the presence of loopholes that allow landlords sidestep the regulations. Landlords are exempt from the 4% cap in certain circumstances, such as where substantial renovations are undertaken or where a property has not been rented in the previous two years. Furthermore, a striking proportion of tenancies within the RPZs have simply breached the 4% cap (Ahrens et al., Citation2019). Non-compliant landlords risk a €15,000 fine, but sanctions are trivial when compared to the potential profit from flouting the rules. Eleven respondents discussed their concerns with the nature of these loopholes, while two could document personal examples of how landlords had ended their tenancy, only to re-let the property at a higher rent and without penalty. In policy terms, the results highlight the need for further monitoring of RPZ tenancies and research into landlord compliance to assess the functionality and appropriateness of landlord exemptions.

“… I have been there for less than six months, and it was a shared apartment…we just got a letter from the landlord saying that she’s selling the apartment…obviously you have to leave… two months after that they renovated the full apartment in the inside and they put it up for rent again at a higher price.” (Chifa, Inner City, House Share)

The findings reveal the clear connections between labour market security, rental affordability and financial stress in the Irish context and the challenges faced by young and economically vulnerable renters. While affordability challenges are prevalent across the rental sector (Waldron, Citation2021), it is clear that the Covid-19 pandemic reinforced the vulnerabilities for lower income groups and those employed in sectors that were impacted by lockdown restrictions. The findings emphasise renters’ lack of agency in rent setting, their limited power to influence rent affordability and their dependence on their landlords’ good will when faced with an economic shock, like unemployment or income loss.

Physical qualities

The negative emotional effects of precarious housing are intertwined with respondents’ experiences of the physical qualities of home and their ability to exert agency in homemaking (Soaita and McKee, Citation2019). Almost all participants (n = 22) reflected on the quality of rental accommodation, with the most common issues being mould, damp and heating. Migrants compared Irish rental standards and construction quality with other contexts, deeming Irish apartment standards to be lower quality in terms of space, daylight, warmth and insulation than European peers. Eight respondents expressed frustrations with small space standards and their frustrations in storing belongings, limited personal space and impediments to homemaking. One respondent discussed how she stored personal belongings outside in her car, owing to the lack of storage within her four-person house share, which amplified inter-personal tensions within the home. Others expressed dissatisfaction with the increasing prevalence of smaller one-bedroom apartments and studios. Indeed, between 2015 and 2018, in a bid to stimulate apartment construction, the Government adopted new apartment size standards that reduced the minimum size of a one-bedroom apartment in Dublin from 55 m2 to 45 m2 and introduced a new ‘studio’ classification of just 37 m2. Some participants expressed great frustration at these new standards, particularly as the impacts of limited personal space became amplified during the Covid-19 pandemic as people spend more time living and working at home.

“We definitely struggled with storage in our house… You find yourself putting some of your your clothes in the kitchen… there’s no room out in the boiler under the stairs… sometimes I leave a lot of stuff in my car.” (Margaret, Inner-City, House Share)

“…if you find something over €1,000, it’s always a studio…They’re very small and I don’t know how people live in it… my room was just a double bed and a really small wardrobe… when you just walk into the room and just like go on the bed and that’s it… like there’s no turn around” (Alicija, Suburbs, Couple)

The most serious issues arose from poor maintenance and standards and the resultant impacts upon tenants’ physical and mental health. Reflecting existing research (Fields, Citation2017), eleven participants recounted their experiences with damp in their properties, as well as infestations, poor-quality heating and ventilation. Twelve participants had experienced issues of black mould within bathrooms and kitchens, which in some instances led to physical health issues, like chest infections or asthma, which they attributed to poorly ventilated buildings. In two serious cases, respondents reported infestations of rats and bed bugs which were the result of degraded walls or old furniture. These experiences had dramatic impacts on the well-being of tenants, impeding their ability to find comfort in their homes. Some reported feeling sick or run down from residing in poor-quality environments or experiencing feelings of depression in properties that were poorly insulated or had inefficient heating. Such experiences negated tenants’ efforts to engage in homemaking, to make their properties comfortable; thereby adding to their negative experiences. In Elaine’s experience, she felt it was commonplace for renters to under-report maintenance issues over fear of rent reprisals. As well as contributing to physical and mental stress, such experiences reflect tenants’ lack of agency relative to landlords, sometimes having to endure poor conditions as they waited for market conditions to change before they could secure better quality accommodation.

“…a rat the size of my hand came running across the room and I went like a lunatic… You’d nearly put up with it because you’re afraid of the landlord putting up your rent or putting you out…” (Elaine, Commuter, Single)

“… it was affecting my well-being. It just it was making me depressed that this disgusting apartment that is always cold. I was spending all my time in there and just, you know, sitting there into blowers because it was so cold. So yeah, that did weigh on me…” (Michal, Inner City, Couple)

The quality dimension of housing precarity reveals how tenants are often strategic in raising issues of poor maintenance to landlords, fearing that such requests may be met with rent reprisals or the termination of a tenancy. Six participants discussed how they were strategic in requesting maintenance, only asking for major repairs they couldn’t complete themselves as they feared antagonising their landlords. Furthermore, 12 respondents discussed how requests for maintenance had led to tensions with their landlords, or their dissatisfaction when repairs were completed. Describing a culture of poor service provision, participants described how landlords would delay or ignore maintenance requests, meaning tenants often took on repairs themselves.

Such challenges were amplified during the Covid-19 pandemic, as social distancing requirements and restrictions on travel and construction limited contractors from entering homes. Emma described how neighbouring construction work had damaged her bedroom wall, which resulted in draughts and mould that affected her ability sleep and to work remotely from home. Her landlord initially deflected the task of arranging repairs with the contractors to Emma, which she found both stressful to manage and a dereliction of her landlord’s responsibilities. However, as the pandemic wore on and the repair work failed to be completed, Emma’s landlord stated he would be unable to rectify the situation until lockdown restrictions on movement had passed and advised her to temporarily plug the gap with newspaper. While landlords are legally obligated to provide properties in good structural repair, eight participants discussed how landlords would often provide a ‘patch job’ to minimise the costs of maintenance or provide second-hand furniture or appliances when replacements were required. As such, the quality dimension of precarity not only demonstrates how landlords can offload the risks and responsibilities for property management onto tenants, but also how tenants pay exorbitant rents for what they often consider to be poor-quality service, thereby negating their ability to enjoy that property as their home.

“… with the hole in the wall… We had to kind of navigate the relationship with the builders… that was just really stressful…as opposed to coming from the landlord… Now like it’s obviously covid and stuff. I think he said at one stage. ‘Oh, I’d come and do it myself if I could, but I can’t. So, just maybe…. I don’t know stick some newspaper in it” (Emma, Inner-City, House Share)

“The things he would replace for equipment that was also second-hand… the apartment was very old, the carpets were very old.” (Ravi, Inner-City, Single)

The Covid-19 pandemic has introduced new challenges for renters as they adapt their homes as working environments (Preece et al., Citation2021). While most respondents continued to work from home, a small number (n = 4) specifically detailed challenges regarding inadequate personal space and tensions with housemates, which impacted upon well-being. Debare was a recently arrived student who shared a cramped two-bedroom apartment with three other migrant students and described how the lack of privacy in sharing a bedroom and his desire for greater personal space impacted his mental health and ability to engage in online classes. While sharing tenancies is a common strategy for young people to address affordability concerns, the results reveal how over-crowding can impact upon tenants’ well-being. Three respondents reflected upon the challenges of adapting their rental properties to home offices and the difficulties of balancing home life with their working demands. Some discussed their unwillingness to invest in equipment for a home office due to expense, limited space availability and the likelihood they would have to leave items behind when moving. The challenges of working in tight spaces was a frustration, where participants were disturbed by the noise of housemates taking work calls, challenges of broadband connectivity and privacy. Two respondents described the stress of being constantly ‘available’ to colleagues due to online working, meaning they worked longer hours and struggled with the lack of a barrier between work and home life.

“…I’m kind of like I need my space. I’m kind of an introvert so there will be times I would like to be alone and I can’t do anything about it….So it’s not comfortable… having your room is like important.” (Debare, Suburban, House Share)

“… it was a difficult, or parts of it is difficult… The bad side of it I would say, is that you find yourself working longer hours. You know, so I would just jump to bed and then the desk and I’m going to work.” (Chifa, Inner-City, House Share)

Security of tenure and landlord relationship

While the interviews identified the fundamental importance of housing quality to renters’ experience of home, they also revealed how the temporary nature of renting served to undermine tenants’ personal connections to their homes (Byrne and McArdle, Citation2022). Indeed, research has documented the importance of tenure security, homemaking and the ability to personalise one’s space to renters’ feelings of well-being and identity, and how the denial of such agency can impact quality of life (Preece et al., Citation2021). Of the seven respondents who experienced the sudden ending of a tenancy, Grace’s experiences revealed the powerlessness many renters feel when faced with eviction. Grace had experienced two forced terminations of tenancies. In one case, a landlord had failed to maintain their mortgage obligations and the bank had repossessed the property, while another case resulted in the forced sale of a property following her landlord’s divorce. Grace had believed these to be long-term rentals for herself and her young daughter and described the considerable anxiety she felt when confronted with the reality of finding suitable nearby properties. Reflecting research on the impacts of eviction on children (Desmond, Citation2016), Grace described how her daughter’s well-being was affected by the loss of her social networks. When she couldn’t find affordable accommodation, Grace and her daughter had to move into her parent’s home, which raised complex emotions for her in terms of parenting her child while under her parent’s roof and a diminished sense of adulthood and independence.

“…the property that I was in was being taken back with the bank… that’s when I went back to my parents…there was no indication that there was any problems… I was left in such a predicament….a massive ordeal at the time….my daughter had made a lot of friends and she was at that age where friendships are really important… you’re put in a situation where you’re no longer feeling like an adult… you have another two parents that you nearly have to coparent with, which is really difficult.” (Grace, Suburban, Lone Parent)

Participants reflected on the temporary nature of renting which mitigated against their efforts to establish permanent homes where they could settle down and start families. Fifteen respondents did not view renting as a long-term option, as their tenancies could be terminated at the end of their lease agreements or if their landlord decided to sell or renovate their properties. They expressed frustration with the short durations of leases, oftentimes drawing parallels to European models where longer contracts (10+ years) are common. Indeed, ten respondents expressly described their rentals as temporary residences to facilitate working and invested limited time or expense in acquiring furniture or trying to personalise their space. Eleven respondents reflected on their frustrations to decorate their homes, have pets or invest in furniture, which limited their ability to shape their living environments. For Tobias, another limitation on homemaking was the recurrent property inspections by his letting agent, which he felt were an invasion of privacy and restricted his ability to enjoy his home as a space for socialising. In summary, the interviews reveal how the insecurity of tenure and restrictions on personalisation undermine tenants’ enjoyment of their dwellings as home; a point that was intensified during the pandemic as people were required to comply with lockdown restrictions.

“…I feel like it’s temporary….it’s not a home because, you know, I would love to have a dog…this is not my home and I know that if I ever have a problem at work…this is not going to be here waiting for me… we are the generation rent where we’re deprived of that feeling of belonging to a place”(David, Inner City, House Share)

“…[letting agent] come three or four times a year, usually after bank holidays… they want to check if you have had a party and ruin the place….and they take pictures for every room right…that’s a little you know, an intrusion on our privacy.” (Tobias, Suburban, Couple)

Conclusions

This article has examined differing aspects of housing precarity amongst tenants navigating the private rental sector in Dublin and the ways such impacts have been amplified by the Covid-19 pandemic. The paper contributes to the broader literature on private renting (Kemp, Citation2015) by elaborating on renters’ subjective experiences of housing precarity, emphasising its affective and embodied dimensions. The paper elaborates on renters’ feelings of a lack of control and uncertainty over their housing situations, and how such experiences negatively impact on their emotional well-being. Conceptually, the paper further elaborates on the utility of precarity within housing research; how it can capture multiple dimensions of households’ experiences under a single, framework, quite unlike related concepts like housing instability or deprivation, which are narrower in scope and tend to focus on the most marginalised in society (Clair et al., Citation2019). Indeed, the research demonstrates the experience of housing precarity cuts across traditional socio-economic lines, as even those from more middle-income backgrounds experience precarity in the rental sector, thereby adding to existing work on the experiences of more vulnerable renting groups (Lombard, Citation2021, McKee et al., Citation2020).

Empirically, the findings explore how housing precarity is experienced as scale of intensity that can be amplified during periods of peak economic stress. Indeed, while most participants had experienced housing precarity before the onset of Covid-19, these experiences were amplified by the economic and social fallout from the pandemic. As such, the prevalence of housing precarity can fluctuate in response to wider economic conditions, and may be experienced more severely at particular points in time by more vulnerable renting sub-groups, like lone parents or the unemployed (Waldron, Citation2021).

The research elaborates on renters’ subjective experiences of housing precarity, recognising that an individual’s perception of their circumstances might be different from their reality, but is nonetheless likely to affect their wellbeing (McKee et al., Citation2017). Reflecting Soaita et al’s (Citation2020) work, renters experience a lack of control over their own housing situations, economic security and a lack of alternative housing options, which contributes to feelings of anxiety and uncertainty. High rents, weak regulation and landlords’ selective criteria are significant barriers to finding suitable accommodation. The interviews revealed renters’ limited negotiating power in renting setting and their limited options in the rental sector given a pernicious supply-demand imbalance, the property rights of landlords and non-compliance with existing rent controls. In a novel contribution, the article further details a spatial dimension to the experience of housing precarity for young families and their increasing deflection to the urban periphery, where they must trade off lower rental values and large units against the costs of being more distant from employment centres, amenities and transportation hubs (Hulse and Yates, Citation2017).

Precarious housing is often poor-quality housing, and the findings point to significant issues with space, storage, damp, heating and infestations. Reflecting the findings of Byrne and McArdle (Citation2022), participants elaborated on their anxieties of raising maintenance issues with landlords, fearing they might be subjected to rent reprisals or evictions, which resulted in some enduring poor housing conditions which affected their mental and physical health. The findings reveal how such insecurity reinforces the temporality of renting, and participants rarely viewed renting as a long-term housing option. Indeed, housing precarity is clearly experienced on an emotional level, as many expressed fears for their financial security and inability to access homeownership, thereby contributing to emergent literature on the intergenerational inequalities in housing access and the politics of housing more generally (Ronald, Citation2018).

The paper makes a significant contribution to the emergent literature on the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on renters’ well-being. Echoing findings from the UK and Australia (Horne et al., Citation2020, Soaita, Citation2021), the interviews demonstrate how the pandemic amplified existing housing precarities for many, as well as introducing new challenges for home working and landlord relationships. While most respondents continued to work and met their rent obligations, a small number struggled with affordability concerns arising from the temporary loss of employment or reduced incomes. These financial stresses were compounded by their limited saving capacity and financial buffers, which meant they often struggled with unexpected expenses. Some had slipped into rent arrears, which had been a significant source of anxiety and required forbearance arrangements with landlords; further demonstrating tenants’ dependency on their landlords. Others pointed to flatmates returning to their home countries or parental homes, which created difficulties in finding replacements during a health crisis. Similar to Brown et al (Citation2020), the interviews revealed significant issues with minimum standards, maintenance and space quality, which impact individuals’ ability to work remotely. These findings highlight the short sightedness of recent policy initiatives to reduce apartment sizes further. If home working becomes more normalised as societies reopen, then those impacted by poor-quality internal environments may be further disadvantaged. The research elaborates on the range of impacts and the unevenness of the effects of Covid-19 on renters, suggesting that recovery efforts not only need to target the economic and security dimensions of housing precarity, but also issues regarding the quality of housing and neighbourhoods.

The Irish rental sector has undergone significant changes in recent years and has been impacted by a variety of problems, not least during the Covid-19 pandemic. While these challenges were somewhat alleviated by emergency unemployment benefits, rent subsidies and eviction bans, such interventions should be maintained for as long as it takes for affected households to recover their economic position. A three-year rent freeze and a tax credit for renting households has been mooted by opposition parties, while others point to the need for better regulation around rent setting to provide greater economic certainty to renters. One immediate response may be to increase the enforcement powers of the RTB through the range of sanctions and fines available for non-compliant landlords. Increasing the resources for Environmental Health Officers to conduct proactive inspections of landlords’ properties and increasing sanctions for landlords would also help address issues regarding housing quality. Enhancing measures to support tenants in long-term, secure leases is an essential step for addressing housing precarity and non-compliance with existing rental regulations. Such responses are urgently required to address the negative experiences of tenants in a lightly regulated private rental markets and to mitigate the worst impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 HAP tenants secure their own private tenancy and pay a rent contribution linked to their income. The remainder is subsidised by government and paid directly to the landlord. There are rent limits under HAP, which are determined by local authority area and household size. For example, in Dublin City the maximum rent allowable under HAP is €1,275 for a couple with two children.

References

- Ahmad, K., Erqou, S., Shah, N., Nazir, U., Morrison, A. R., Choudhary, G. & Wu, W.-C. (2020) Association of poor housing conditions with COVID-19 incidence and mortality across US counties, PloS One, 15, pp. e0241327.

- Ahrens, A., Martinez-Cillero, M. & O’Toole, C. (2019) Trends in Rental Price Inflation and the Introduction of Rent Pressure Zones in Ireland (Dublin: Economic and Social Research Institute).

- Amerio, A., Brambilla, A., Morganti, A., Aguglia, A., Bianchi, D., Santi, F., Costantini, L., Odone, A., Costanza, A., Signorelli, C., Serafini, G., Amore, M. & Capolongo, S. (2020) Covid-19 lockdown: Housing built environment’s effects on mental health, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, pp. 5973.

- Baker, E., Daniels, L., Pawson, H., Baddeley, M., Vij, A., Stephens, M., Phibbs, P., Clair, A., Beer, A. & Power, E. (2020) Rental Insights A COVID-19 Collection (Melbourne: AHURI - Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute).

- Baker, E., Lester, L. H., Bentley, R. & Beer, A. (2016) Poor housing quality: Prevalence and health effects, Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 44, pp. 219–232.

- Bentley, R., Baker, E. & Aitken, Z. (2019) The ‘double precarity’ of employment insecurity and unaffordable housing and its impact on mental health, Social Science & Medicine (1982), 225, pp. 9–16.

- Brown, P., Newton, D., Armitage, R. & Monchuk, L. (2020) Lockdown. Rundown. Brokedown: The Covi-19 Lockdown and the Impact of Poor-Quality Housing on Occupants in the North of England (Huddersfield: The Northern Housing Consortium).

- Byrne, M. & Mcardle, R. (2022) Secure occupancy, power and the landlord-tenant relation: A qualitative exploration of the Irish private rental sector, Housing Studies, 37, pp. 124–142.

- Byrne, M. (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on the private rental sector: emerging international evidence, Public Policy.IE, 2021(February), pp. 1–14. [Online]. Dublin: PublicPolicy. ie. Available at https://publicpolicy.ie/perspectives/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-the-private-rental-sector-emerging-international-evidence/.

- Chisholm, E., Howden-Chapman, P. & Fougere, G. (2020) Tenants’ responses to substandard housing: Hidden and invisible power and the failure of rental housing regulation, Housing, Theory and Society, 37, pp. 139–161.

- Clair, A., Reeves, A., Mckee, M. & Stuckler, D. (2019) Constructing a housing precariousness measure for Europe, Journal of European Social Policy, 29, pp. 13–28.

- CSO. (2021a) Average Annual Earnings and Other Labour Costs by Type of Employment, NACE Rev 2 Economic Sector, Year and Statistic [Online] (Dublin: Central Statistics Office). https://www.cso.ie/px/pxeirestat/Statire/SelectVarVal/Define.asp?maintable=EHA05&PLanguage=0.

- CSO. (2021b) Private Households in Permanent Housing Units 2011 to 2016 [Online] (Dublin: Central Statistics Office). https://data.cso.ie/ (accessed 4 May 2021).

- Desmond, M. (2016) Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City (London: Penguin).

- DOHPLG. (2021) HAP Scheme 2014-2020 (Dublin: Department of Housing, Local Government, and Heritage).

- Fields, D. (2017) Unwilling subjects of financialization, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41, pp. 588–603.

- Fuster, N., Arundel, R. & Susino, J. (2019) From a culture of homeownership to generation rent: housing discourses of young adults in Spain, Journal of Youth Studies, 22, pp. 585–603.

- Green, N., Tappin, D. & Bentley, T. (2020) Working from home before, during and after the Covid-19 pandemic: implications for workers and organisations, New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 45, pp. 5–16.

- Gurney, C. (2020) Out of Harm’s Way? Critical Remarks on Harm and the Meaning of Home During the 2020 Covid-19 Social Distancing Measures (Glasgow: UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (CaCHE)).

- Hoolachan, J. & Mckee, K. (2019) Inter-generational housing inequalities:’Baby Boomers’ versus the ‘Millennials’, Urban Studies, 56, pp. 210–225.

- Horne, R., Willand, N., Dorignon, L. & Middha, B. (2020) The Lived Experience of COVID-19: Housing and Household Resilience (Melbourne: AHURI).

- Huisman, C. J. & Mulder, C. H. (2020) Insecure tenure in Amsterdam: who rents with a temporary lease, and why? A baseline from 2015, Housing Studies, doi: 10.1080/02673037.2020.1850649.

- Hulse, K. & Milligan, V. (2014) Secure occupancy: A new framework for analysing security in rental housing, Housing Studies, 29, pp. 638–656.

- Hulse, K. & Yates, J. (2017) A private rental sector paradox: unpacking the effects of urban restructuring on housing market dynamics, Housing Studies, 32, pp. 253–270.

- Hulse, K., Milligan, V. & Easthope, H. (2011) Secure occupancy in rental housing: conceptual foundations and comparative perspectives (Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute).

- Kalleberg, A. L. (2009) Precarious work, insecure workers: Employment relations in transition, American Sociological Review, 74, pp. 1–22.

- Kemp, P. A. (2015) Private renting after the global financial crisis, Housing Studies, 30, pp. 601–620.

- Lombard, M. (2021) The experience of precarity: low-paid economic migrants’ housing in Manchester, Housing Studies, doi: 10.1080/02673037.2021.1882663.

- Lyons, R. (2021) The Daft.ie Rental Price Report (Dublin: Daft.ie).

- Mason, M. (2010) Sample Size and Saturation in PhD Studies Using Qualitative Interviews (Forum: qualitative social research).

- Mckee, K., Soaita, A. M. & Hoolachan, J. (2020) Generation rent’and the emotions of private renting: self-worth, status and insecurity amongst low-income renters, Housing Studies, 35, pp. 1468–1487.

- Mckee, M., Reeves, A., Clair, A. & Stuckler, D. (2017) Living on the edge: precariousness and why it matters for health. Archives of Public Health, 75, 13.

- Morris, A. (2013) The trajectory towards marginality: how do older Australians find themselves dependent on the private rental market?, Social Policy and Society, 12, pp. 47–59.

- Parrott, J. & Zandi, M. (2021) Averting an Eviction Crisis [Online] (Washington, DC: Urban Institute). https://www.urban.org/research/publication/averting-eviction-crisis (Accessed 11 May 2021).

- Pembroke, S. (2018) Precarious Work, Precarious Lives: How Policy Can Create More Security (Dublin: TASC).

- Power, E. R. & Gillon, C. (2020) Performing the ‘good tenant’, Housing Studies, doi: 10.1080/02673037.2020.1813260.

- Preece, J., Bimpson, E., Robinson, D., Mckee, K. & Flint, J. (2019) Forms and Mechanisms of Exclusion in Contemporary Housing Systems: A Scoping Study (Glasgow: The UK Centre for Collaborative Housing Evidence).

- Preece, J., Mckee, K., Robinson, D. & Flint, J. (2021) Urban rhythms in a small home: COVID-19 as a mechanism of exception, Urban Studies. doi: 10.1177/00420980211018136.

- PUBLIC HEALTH ENGLAND. (2020) Beyond the Data: Understanding the Impact of COVID-19 on BAME Groups (London: Public Health England).

- Ronald, R. & Kadi, J. (2018) The revival of private landlords in Britain’s post-homeownership society, New Political Economy, 23, pp. 786–803.

- Ronald, R. (2018) Generation Rent’ and intergenerational relations in the era of housing financialisation, Critical Housing Analysis, 5, pp. 14–26.

- RTB. (2020) Residential Tenancies Board: Annual Report 2019 (Dublin: Residential Tenancies Board).

- SHELTER. (2021) Shelter Briefing: Lords’ Debate on Mass Evictions and COVID-19 Related Poverty [Online] (London: Shelter). Available at https://england.shelter.org.uk/professional_resources/policy_and_research/policy_library/briefing_house_of_lords_debate_on_the_risk_of_mass_evictions_resulting_from_covid-19-related_poverty (accessed 11 May 2021).

- Simcock, T. (2020) What is the Likely Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the UK Private Rental Sector? [Online] (UK Collaborative Center for Housing Evidence). Available at https://housingevidence.ac.uk/what-is-the-likely-impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-the-uk-private-rented-sector/(Accessed 18 May 2021).

- Sirr, L. (2014) Renting in Ireland: The Social, Voluntary and Private Sectors (Dublin: Institute of Public Administration).

- Smith, M., Albanese, F. & Truder, J. (2014) A Roof Over My Head: The Final Report of the Sustain Project. Final Report of the Sustain Project (London: Shelter & Crisis).

- Soaita, A. (2021) Renting during the Covid-19 Pandemic in Great Britain: The Experiences of Private Tenants (Glasgow: CACHE - UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence).

- Soaita, A. M. & Mckee, K. (2019) Assembling a ‘kind of’home in the UK private renting sector, Geoforum, 103, pp. 148–157.

- Soaita, A., Munro, M. & Mckee, K. (2020) Private Renters’ Housing Experiences in Lightly Regulated Markets: Review of Qualitative Research (Glasgow: UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence).

- Standing, G. (2014) The Precariat-The New Dangerous Class (London: Bllomsbury Academic).

- Vosko, L. F. (2006) Precarious Employment: Towards an Improved Understanding of Labour Market Insecurity (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press).

- Waldron, R. (2018) Capitalizing on the state: The political economy of real estate investment trusts and the ‘resolution’ of the crisis, Geoforum, 90, pp. 206–218.

- Waldron, R. (2021) Generation rent and housing precarity in ‘post crisis’ Ireland, Housing Studies, doi: 10.1080/02673037.2021.1879998.

- Waldron, R., O’Donoghue-Hynes, B. & Redmond, D. (2019) Emergency homeless shelter use in the Dublin region 2012–2016: Utilizing a cluster analysis of administrative data, Cities, 94, pp. 143–152.

- WHO. (2021) WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard [Online]. Available at https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed 08 November 2021).

- Woods, K. & Cooney, R. (2021) Landlords adopt ‘incentivised’ rents amid warnings of market distortion, Business Post, 25/04/2021.