Abstract

Housing has always had a close association with refugees but despite this, the knowledge base about housing and its impact in the lives of refugees lacks cohesion. The accommodation of refugees tends to be connected with broader neo-liberal trends, alongside a general animosity towards refugees, culminating in an overt, or implied, ‘hostile environment’. This paper synthesises the available evidence to understand several key issues in the settlement of refugees, including: the role and impact of housing systems and policies, the impact of housing quality, tenure, housing support workers and how the diversity of the refugee population is reflected in the evidence. We also point towards gaps in the knowledge base and call for housing studies scholars to focus on the plight faced by refugees in order to help challenge the wider structural inequalities which constrain their lives. In this discussion, our focus is the United Kingdom (UK), although the paper draws on literature from a wider international perspective.

Introduction

There is an urgent need to address the issues facing refugees in relation to their housing opportunities and housing pathways. Housing has always had a close association with migration, particularly for involuntary migrants who have been forced to move from their homes in their country or place of origin, due to an experience or fear of persecution, to seek sanctuary elsewhere. As Flatau et al. (Citation2015) have observed, ‘[h]ousing plays a fundamental role in the journey of refugees following resettlement in a host country’ (p. 8). The movement of refugees is, by definition, a planetary issue. The policy approach of one state such as [the lack of] military involvement, the provision of foreign aid, and immigration policies directly and indirectly effects the living conditions, and the context, in which millions of people who and vulnerable to exile live. The access to housing is seen as a major resource to be manipulated by governments in order to manage the movement of refugees. For example, within the UK steps are being taken to ‘reform’ the system of managing and restricting the asylum and refugee system which will once again transform the way in which refugees access accommodation (Home Office, Citation2021a, Citation2021b). Amongst the proposals are the potential for ‘off-shoring’ asylum seekers in re-purposed accommodation units, an increase in the use of reception centres as well as the continuation of resettling sponsored refugees. These proposals should be of serious interest to housing scholars, especially given that refugees are particularly disadvantaged in relation to housing. Drawing on the work of Powell and Robinson (Citation2019), who argue that in the ‘midst of a housing crisis’, there are particular negative consequences for those ‘at the bottom of the class structure’ (p. 188). This wider context is critical in any effort to analyse the impact of housing on refugees. The housing crisis relates to a ‘…lack of affordable housing, falling quality standards, insecurity and socio-spatial concentrations of poverty’ (Powell & Robinson, Citation2019, p. 188) and although these are often interpreted in simplistic ways, the reality is far more complex, played out against a rhetoric of ‘them’ and ‘us’ whereby migrants are falsely constructed as taking preference for housing against those already living in the UK (ibid.). When combined with the impact of racism and racialisation, this results in migrants being placed at ‘particular disadvantage’ (Powell & Robinson, Citation2019, p. 202).

There is general agreement that housing is a key pillar of integration for refugees (Ager & Strang, Citation2008), yet it remains an area for which there is little attention in housing studies. However, the availability of housing remains at the centre of localised debates regarding immigration in which discourses of blame blur boundaries between migrant and ethnic ‘others’ (Powell & Robinson, Citation2019), Phillips (Citation2006) provided a key analysis of the intersection between housing and integration based on fieldwork undertaken almost two decades ago. However, since this time there has been global social change and multiple policy interventions, including the advancement of neoliberalism and welfare retrenchment (Powell & Robinson, Citation2019), which together has provoked a great deal of research interest. Despite this, the knowledge base about housing and its impact on refugees lacks cohesion. Amongst many issues there remains a lack of understanding about the role and impact of housing systems and policies, housing quality, tenure, housing support workers and how the diversity of the refugee population is reflected in this evidence. Moreover, there is a lack of understanding about what gaps there are in our knowledge base. Because of this gap, the political sensitiveness of refugee movements, coupled with the recent return of policy makers to this area, it is vitally important that information and evidence is gathered on what is known about this subject. This is critical as Hauge et al. (Citation2017) have argued, ‘the built environment contributes to the recognition or lack of recognition of various groups as equal in the society’ (p. 17). Whilst these issues are planetary in nature (The Lancet, Citation2015) because of the socio-legal complexities involved our focus is on housing and refugees relating to a UK context. In doing so we draw upon research from the UK and other contexts in order to enhance our understanding. However, we believe that the findings contained within this paper have resonance far beyond the UK.

It is noted that in common parlance it is usual for all forced or involuntary migrants to be referred to as ‘refugees’ but in legal terms this is a narrow category reflecting only those that can demonstrate a compatibility with the definition of a refugee outlined in the 1951 United Nations (UN) Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. Whilst there exist critiques of the Convention (Benhabib, Citation2020; Greatbatch, Citation1989) it still operates as a framework from which a large number of refugees can be identified and provided with the appropriate protection, support and rights (including the right to housing). Within this paper we recognise that for many refugees their resettlement experience is part of a continuum which includes, for many, a period awaiting a decision on their status. As such their experience of settlement as a refugee is entangled with their experience pre-status accordingly our focus in this paper includes those seen as asylum seekers as well as recognised refugees.

This paper is divided into five sections. Sections one and two of the paper provide a contemporary refugee policy perspective of housing in the UK. Moving on from this, in section three of the paper the authors set out in precise detail the research method that was applied. Then from this, section four presents the results from the scoping review presented into different subject themes. In the final section, the authors draw the paper to a close by providing a discussion on the important aspects of refugee housing from a global perspective and provide recommendations.

The intended contribution of knowledge is twofold. Firstly, the authors of this work wish to further highlight the impact upon refugees by their limited access to decent housing and support. Secondly, the authors would like to draw on these findings to call for the greater engagement by a wider group of scholars and practitioners in improving the housing system for refugees.

Background

Contemporary refugee policy in the UK

The existence and number of asylum seekers and refugees has long fascinated social scientists (see in particular Dwyer et al., Citation2016; Fiddian-Qasmiyeh & Qasmiyeh, Citation2010; Phillips, Citation2006; Stewart, Citation2005 ). Moreover, there has been increasing interest in debates around asylum seekers and refugees as related to the tragic events of the European ‘migrant crisis’ which ‘peaked’ in 2015. Nested against a backdrop of migration control there is little doubt that the visibility of the European migrant crisis has brought a new political focus on the economic, political, cultural and social aspects of refugee challenges in a public policy context (see Cheung & Phillimore, Citation2014; Guma et al., Citation2019; Mulvey, Citation2015). This is particularly acute in the UK where migration casts a long shadow due to a complex history of social policy relating to migration more broadly, and asylum seeking/refugees specifically, reflecting an immigration process informed by racialisation and racism at several points (Solomos, Citation2019). These issues remain a ‘hot topic’ of political, policy and public concern (Jones et al., Citation2017). It is beyond the scope of this paper to review these policy developments, authors such as Rutter (Citation2015) and Goodfellow (Citation2019) have provided comprehensive historical analyses. However, it is important to recognise that current policy and approaches to the welcome (and otherwise) afforded to migrants (and in particular asylum seekers and refugees) is rooted in this particular socio-political context. Following numerous attempts at reform over the last 25 years the UK government is, at the time of writing, once again updating its immigration policies and laws. The recent Home Office strategy statement outlines the principles of the emerging points-based system, which are: Fairer, Firmer, and Skills-led (Home Office, Citation2021a). Whilst the UK Government has underlined its intention to continue to play a role in providing sanctuary for refugees, there are specific proposals announced in early 2021 which outlined its intention to radically reform the process and system. These proposals largely consist of increasingly restrictive measures (reflecting broader neoliberal trends in responding to migration) including: reducing the level of protection for refugees who arrive via irregular routes; replacing current arrangements for accommodation with reception centres in the south of England; and, developing off-shore accommodation processes for those awaiting a claim (see Home Office, Citation2021b). Over the last 25 years the provision of housing, or rights to housing, has been at the centre of reforms to the refugee system and how asylum seekers are managed. Whilst we acknowledge the role of devolution in the UK the asylum system is an issue reserved to the UK Government and managed by the Home Office. Although it should be noted that Scotland’s New Scots approach seeks to support refugees and asylum seekers in their settlement from their initial arrival (Scottish Government, Citation2018) and devolved regions of England (e.g. Greater Manchester, Liverpool, the West Midlands, etc.) drive housing policy in those areas.

The role of housing in the support of refugees in the UK

The UK has mobilised a housing-led approach to support and manage the asylum system since far-reaching reforms in 1999 and the ability to resettle recognised refugees is, in large part, dependent upon having access to available and suitable housing. There are currently two main routes to refugee status in the UK each comes with particular challenges but once recognised as refugees in the UK they have largely the same rights as citizens. The first route is through arriving independently in the UK and applying for refugee status, during which time an individual is classified as an asylum-seeker, which represents 73% of the total number of refugees (Sturge, Citation2019). Individuals through this route tend to be subject to dispersal across the UK into allocated accommodation units managed by a private contractor on behalf of the Home Office. Asylum-seekers who are subsequently granted refugee status are given 28 days to transition to life as a UK resident. During this time, this group of new refugees are required to move out of the accommodation provided by the Home Office while their claim for asylum was considered and find a job and/or apply for mainstream benefits. After the move-on period, support available to refugees, for example to learn English or access employment, is ad hoc and varies by location (Refugee Action, Citation2016; Refugee Employment Network, Citation2018).

The second route is as part of a government resettlement programme, whereby an individual is granted refugee status outside the UK and is voluntarily relocated to the UK. There is a history of resettlement programmes in the UK which reflect the UK government intervention in international events. These include the post-war Polish resettlement programme, the Ugandan Asian programme and the support provided to Chilean refugees in the 1970s, the Vietnamese programme in 1979, the Bosnian resettlement programme in the early 1990s and the Kosovan humanitarian evacuation programme in 1999. Recently, there have been four programmes for the resettlement of refugees in the UK: the Gateway Protection Programme, the Vulnerable Children Resettlement Scheme, the Mandate Resettlement Scheme and the Syrian Vulnerable Person Resettlement Scheme (VPRS). Within 2021 the UK government initiated two new routes for citizens of Afghanistan to receive protection these include the Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme (ACRS) and the Afghan Relocations and Assistance Policy (ARAP) provides. These routes are similar to the VPRS and offers access to housing, healthcare, education, and support into employment. Resettled refugees typically receive more formal support than refugees who arrive independently and move through the asylum system.

There has been much public policy focus on the way refugees have been given access to accommodation as part of the resettlement process. Housing is critical as it provides shelter and security, and a base from which both community and social connections are made, education and employment links are secured, and from which wellbeing grows. Historical evidence suggests that access to quality accommodation for refugees who settle in the United Kingdom is challenging (Rowley et al., Citation2020; Robinson et al., Citation2007; Zetter & Pearl, Citation1999). These challenges are driven by the way housing is provided and managed, the quality of accommodation on offer and inherent vulnerabilities associated with the position refugees occupy in the UK. In the current post austerity context, with the persistence of neo liberalism, this is even more acute. We acknowledge the powerful presence of neoliberalism in shaping contemporary housing policy for refugees, whilst this has not been the specific focus of this review, as we instead attempt to consolidate the evidence base, we direct others to important work of authors such as Wacquant (Citation2014), Bhagat (Citation2021) and Powell and Robinson (Citation2019). In taking stock of the literature against this canvas it is of little surprise that vulnerable migrants, such as refugees, are particularly susceptible to housing stress, housing insecurity and, ultimately, even to homelessness, in their new life in their destination countries. Literature has reported that this risk is often exacerbated by racism and discrimination, poor health outcomes, lack of social assistance, poor educational access, and low levels of host language proficiency.

The authors are engaged in a large scale study which seems to explore the housing pathways of refugees in the UK. Following Hallinger’s (2013) position that ‘.research reviews enhance the quality of theoretical and empirical efforts of scholars to contribute to knowledge production; (p. 126), in order to inform the focus of our empirical work and understand the knowledge base we sought to systematically synthesize the available evidence on this issue.

Methods

As Munn et al. (Citation2018) identify, scoping reviews are particularly useful as a tool to ‘determine the scope or coverage of a body of literature on a given topic and give clear indication of the volume of literature and studies available as well as an overview (broad or detailed) of its focus’ (p. 2). They go on to identify six purposes for undertaking a scoping review, which are:

To identify the types of available evidence in a given field

To clarify key concepts/definitions in the literature

To examine how research is conducted on a certain topic or field

To identify key characteristics or factors related to a concept

As a precursor to a systematic review

To identify and analyse knowledge gaps

This approach is in contrast to a systematic review which is ideally suited to those research questions which seek to address the feasibility, appropriateness, meaningfulness or effectiveness of a certain treatment or practice (Pearson, Citation2004; Pearson et al., Citation2005).

The search protocol

Informed by the framework for scoping reviews set out by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) we adopted the following process. Firstly, we undertook an initial broad search of the literature to familiarise ourselves with the current state of knowledge in relation to refugees and housing. Following this a scoping strategy document was produced which acted as a search protocol. This search protocol was subsequently peer-reviewed by a colleague with expertise in evidence synthesis, a librarian and two colleagues (academics embedded within refugee organisations) with subject expertise.

Inclusion and exclusion of literature

A scoping question was determined: In what ways do housing and housing-related services impact refugees in their resettlement? This was then developed into a search string and inclusion and exclusion criteria developed (see ).

Table 1. Search string, inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Housing was broadly defined and included any aspects of housing and accommodation but the balance was towards the materialities of housing as opposed to more subjective and conceptual definitions relating to terms such as ‘home’, ‘place’ and ‘belonging’. When issues such as the neighbourhood and the location of housing was mentioned as impact on refugees, in order to be included in the review, papers needed to also specifically highlight the role of housing itself. As stated we recognise the difficulty of separating asylum seeker and refugee populations, and we recognise that refugee status is often part of a continuum which is routinely shaped by a period of time awaiting a decision on an asylum claim. As such the review included both asylum seekers and refugees as well as variations of this term. Finally, we recognise that the concept of ‘integration’ is charged and contested (Brown et al., Citation2020; Saharso, Citation2019) as such we chose to take a broad definition and seek papers which evoked notions of settlement and various related manifestations that feature in the literature. Furthermore, a number of the exclusion criteria are worth drawing out for additional comment. As the scoping study was developed to inform work in the UK it was important that the available material would be applicable to the UK context in terms of the housing or refugee system. As such, material deemed non-applicable was excluded as was studies not available in English. Similarly, we recognised that the refugee experience is distinct from the broader experience of migration therefore we excluded material that did not clearly identify impacts and outcomes for refugee populations. Finally, of note is our desire to include aspects of ‘housing-related’ support but to exclude ‘care’ as the main focus in isolation from the provision of/experience of housing/accommodation. Therefore, we excluded papers where the focus was on the experience of an institution or the experience of the care system. Whilst the authors acknowledge that the issue of detention and its impacts, and the settlement experience of unaccompanied minors, are critical in their own right (Hollis, Citation2019; Wade, Citation2017), these issues are not the focus of this paper due to the specific set of socio-legal issues they entail.

The search strategy

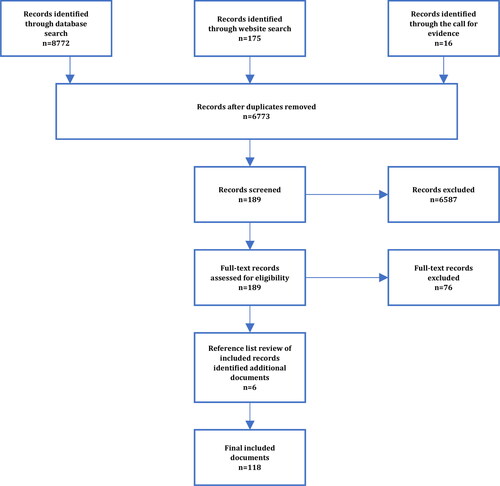

A comprehensive and iterative approach to the literature searches for evidence was taken in February 2021. As the topic area spans a wide number of disciplines and areas, a comprehensive approach to the search was required, which included databases and grey literature. The following databases were searched: Proquest, Medline, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, OAIster, Ingenta Contect, Science Direct, Google Scholar, Scopus, JSTOR, Sage, Policy Commons, CINAHL, British Library, and Wiley. The initial search took a long-term perspective with no exclusion criteria relating to date of publication that yielded 8772 papers. The earliest papers published in the subject area domain of this research were examined. In addition, the websites for a number of key organisations were searched, including: the Centre on Migration, Policy and Society, UNHCR, UNDP, AHURI, Migration Observatory, Refugee Council, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, British Red Cross, Runnymede Trust, Refugee Action, Barrow-Cadbury Trust, OECD, World Bank; together, these yielded 175 reports/outputs. Finally, we issued a call for information amongst networks of which the authors were members, which produced a further 16 outputs for the review.

illustrates the process for the search. The initial search returned 6773 records, after duplicates were removed, that were considered for inclusion, with an additional six publications identified through the reference lists of included papers. All titles and abstracts were screened – alongside the exclusion criteria – which led to a significant number being excluded (n = 6587). All remaining records were read in full by the authors. The records were interrogated with the aid of a pre-designed data extraction table with each author allocated a number of records to review. This information included elements such as: country the document relates to, study aims, research design, key findings, conclusions and recommendations. The authors discussed the information that was extracted, alongside the inclusion/exclusion criteria for each record, in order to work towards an overall perspective on the factors emerging from the literature. Disagreements were discussed until a consensus was reached. Following this process 118 documents were deemed appropriate for inclusion in the review.

Having discussed the method applied for this research, the paper now moves on to present the findings from the scoping review.

Results

Details of each of the 118 studies included in the scoping review can be found in . Due to the sheer volume of sources reviewed we are unable to provide a detailed breakdown of the sources. However, we have provided information on each study according to: first author, date, countries of focus, main aim of the study – where possible this has been extracted from the paper verbatim, methodology and keywords. It is hoped this provide a sufficient overview of the main focus for each of the sources in respect of the aims for this scoping study.

Table 2. Key characteristics of include studies.

As can be seen in studies represented a diverse spread of locations however, nearly half of the studies were based in the UK (49), or from a constituent part. This was followed by studies based in Canada (17) and Australia (14) with smaller numbers from elsewhere. Studies represented a range of localities within these locations, such as urban, city-level, regional, national yet this was not uniformly reported in the papers so we are unable to offer this delineation.

Table 3. Country of focus of the papers.

As shown by , the vast majority of studies where undertaken via qualitative methods (73), which may include a mixture of qualitative methods (e.g. focus groups and interviews) or the use of one single method. This was followed by studies which used and integrated a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods (23). There were 13 studies which solely utilised quantitative methods and nine studies based on reviews of literature.

Table 4. Methodology of selected papers.

Below, we provide a description of the key findings in relation to housing, and housing-related services, and the impact on refugees from all included studies. These are reviewed thematically below and this structure is informed by the findings from the review both in terms of the weight of the evidence and the refugee journey through the housing system.

Policies of ‘housing-led’ dispersal

A large cohort of papers focused on the role of dispersal as a policy and a method of accommodating asylum seekers and, in some cases, refugees. The policy of dispersing asylum seekers across the UK has been a feature of the immigration and asylum system for over two decades but dispersal is also a feature of the policy of other states within the literature including Canada, Australia and Denmark. However, it is the UK experience which dominates the literature. The broad consensus is that dispersal, and the way the system was implemented in the UK, made individual asylum seekers vulnerable, and that this remains the case. Early work by Zetter and Pearl (Citation1999, Citation2000) foreshadowed the impacts of this policy on the refugee community sector in particular, although their predictions are arguably more optimistic than what later studies recorded (see Hill et al., Citation2021). Studies which have examined a decade or more of dispersal have described negative impacts arising due to the movement of people to areas that had little experience of accommodating diversity and difference and were already deprived, where the refugee support infrastructure was missing or embryonic and where the available housing was of poor-quality (Allsopp et al., Citation2014; Darling, Citation2011, Citation2016; Hill et al., Citation2021; Meer et al., Citation2019; Netto, Citation2011a, Citation2011b; Netto & Fraser, Citation2009; Phillimore, Citation2011; Phillimore & Goodson, Citation2006; Phillips, Citation2006; Robinson et al., Citation2007; Warfa et al., Citation2006; Wren, Citation2007). These papers underlined the links between the policy of dispersal and the mental health of asylum seekers caused by poor housing conditions, housing insecurity, constraints on mobility, discrimination and harassment in the local area, a lack of a sense of safety, a lack of specific support (formal and informal) and the absence of meaningful social connections. An early account of dispersal in Robinson and Coleman (Citation2000) related to the experience of the resettlement of Bosnian refugees in the 1990s and was one of the only studies to cite positive aspects of the policy however, it is noted that the delivery of this particular programme was within a more deliberative, consultative and resource intensive framework – when compared to post-1999 dispersal.

Moving beyond the UK there were a handful of papers which highlighted similar issues to the UK example with regards to the implementation of dispersal. Research in Denmark by Wren (Citation2003) found almost identical issues to the UK with dispersal being led by the concept of ‘burden sharing’ and the scarcity of available affordable housing in traditional arrival zones. Like the UK studies, the Danish experience also saw an increase in anti-migrant sentiment within dispersal areas which were seen to be associated with the implementation of the policy. In the US, a paper by Agbényiga et al. (Citation2012) focussed on factors which mitigated negative impacts of dispersal and pointed to the role played by proximal support from family members, or others from the same ethic group, to help with the stress of resettlement.

The administration of asylum seeker and refugee housing systems

Throughout the literature, there is significant emphasis on critiquing the administration of asylum seeker and refugee housing and welfare systems. The complexity of the housing and welfare system as experienced by new refugees – compared to their countries of origin – is particularly underlined (Oliver et al., Citation2020). Work by Hill et al. (Citation2021), Meer et al. (Citation2019; Citation2021) and Darling (Citation2016) discusses the insecurity embedded in the system highlighting the influence of neoliberalism and role of the private sector in the management of the asylum system. This was seen to lead to cheaper, lower-quality, housing used in the delivery of the asylum support package. Similarly, Kreichauf (Citation2018, p. 18) argued that neoliberalism has become the norm in many policy approaches towards many vulnerable groups including asylum seekers, resulting in the privatisation of the refugee sector.

In a number of papers, the work of frontline workers, those ‘street level bureaucrats’ (Lipsky, Citation1980), were seen as critical in helping refugees navigate these systems and political structures (Agbényiga et al., Citation2012; Marsden, Citation2018; Meer et al., Citation2019; Strang et al., Citation2018). Across the literature there was a particular emphasis on the active role played by those working for public sector and voluntary and community sector agencies in overcoming the restrictive structures for new refugees as well as the need for them to do more (see for example, Dudhia, Citation2020; Dwyer & Brown, Citation2008; Fassetta et al., Citation2016; Flatau et al., Citation2015). Although Wimark (Citation2021) noted that the willingness of these workers to change the structures of power were limited with a focus on the implementation of temporary solutions not structural change.

Initial accommodation

Accommodation that is used upon initial arrival in a new country following an asylum claim, or in some cases as part of the resettlement of refugees on sponsored programmes, is referred to by a variety of terms including temporary accommodation, initial accommodation, corridor accommodation, asylum-seeker centres or reception centres. Those who are waiting a decision on their asylum claim are either accommodated in these communal forms of accommodation for a short-period, before being moved to community-based accommodation, or for the duration of their claim – depending upon the asylum process concerned. Where such centres are used to accommodate resettled refugees, these tend to be for orientation purposes before being moved to other forms of independent accommodation in the surrounding locale. Most centres which appear in the literature appear to be centralised and often repurposed buildings such as former health or social care institutions, hostels, former hotels or decommissioned military institutions. They typically comprise dormitory space for residents, staff offices and, often, additional space to host other agencies within the unit. Where these centres are described in the literature they are often portrayed as poor-quality or ‘dilapidated’ buildings which frames the residents in a poor light (Lietaert et al., Citation2020). With Blank (Citation2019) and inhibits the chances for social integration with the wider community in which they are situated. On the theme of stigmatisation of reception centres a study by Hubbard (Citation2005) in the UK looked at the public response to the proposed development of centralised units which were seen to amplify local anti-asylum sentiment.

The literature holds a generally consistent view with broader research in the field that such centres are in poor condition and basic and, as a result, have a negative impact on the mental health of asylum seekers and refugees (Bakker et al., Citation2016; Walther et al., Citation2020) with a number of papers asserting their role in the dehumanisation and exclusion of their residents (Blank, Citation2019; Kreichauf, Citation2018). From the literature, poor living conditions were endemic and there were findings pointing to the lack of privacy (Bakker et al., Citation2016; Gewalt et al., Citation2018), lack of autonomy (Bakker et al., Citation2016), disturbed sleep caused by noise (Gewalt et al., Citation2018; Righard & Oberg, Citation2019), the fear of harassment and discrimination, particularly reported by women (Gewalt et al., Citation2018) all seen as key issues which caused stress and anxiety for residents of these centres. The restrictions placed on residents in centres were also a source of stress (Gewalt et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, such centres were seen by Lietaert et al. (Citation2020) to impact on families by rendering parents powerless when raising their children.

There were few research studies based in the UK which focused on reception centres as part of the study. However, there were studies in Norway, Cyprus, Denmark, Belgium and Greece. There is a single reception centre in Cyprus which is seen as of poor quality and which struggles to accommodate all the housing need (Christodoulou & Michael, Citation2019; Spaneas et al., Citation2018) and does not have staff with the necessary skills to support those who are living there. This was seen, despite the communal nature of the accommodation, to lead to isolation and misunderstandings amongst residents. In their study of centres in Norway, Seeberg et al. (Citation2009) claim that despite having facilities to support the children of families residing there, these were often tokenistic, with centres not managed with the welfare of children in mind. Reception accommodation in Denmark was also seen as negative for children by Vitus (Citation2010) where children exhibited boredom, restlessness, fatigue and despair. In contrast, Norway also provides reception accommodation for asylum seekers in the form of ‘decentralised’ units which comprise of dispersed community-based homes which are linked to a separate building which contain staff offices. These decentralised units appear to have benefits over their centralised counterparts including greater independence, increased levels of activity and an improved experience of social integration (Hauge et al., Citation2017) which subsequent positive impacts on their mental health. However, similar to the centralised units it is common for these homes to be of visibly poorer-quality.

Just one paper looked at the impact of reception centres on resettled refugees. Robinson and Coleman (Citation2000) analysed the experience of the Bosnian refugee programme in the UK where reception centres were used, as a tool in what was seen as a more empathetic approach to refugee policy, whilst local housing and support was identified and implemented before moving households in to their own homes. The main issues identified by Robinson and Coleman (Citation2000) were with respect to their role in the planning and management of the programme, centrally and locally, but also the role they played in creating neighbourhood clusters of refugees in areas in which the reception centres were based.

Few other studies referred to positive impacts of reception accommodation with the exception of Ghorashi et al. (Citation2018) who focussed on the agency exercised by asylum seekers in such centres who contest their marginality.

The housing impacts of receiving refugee status

One of the key areas of housing stress for refugees reported in the literature is the transition from asylum seeker to refugee status. This was largely an issue identified in the UK papers and commonly referred to as the ‘28 day move on period’. This was seen as a period which exacerbated existing vulnerabilities and created ‘multiple disadvantages’ (Dwyer & Brown, Citation2008; Mitton, Citation2021). The literature was consistent in the impact this had on new refugees which was exacerbated by a lack of affordable social housing. Studies noted that refugees were often accommodated in temporary housing, poor-quality housing or in areas that were inappropriate or unsafe for them (Robinson et al., Citation2007; Rowley et al., Citation2020). Research also saw this as being particularly inequitable for new refugees due to a lack of understanding of the welfare system which prevented them making informed decisions (Robinson et al., Citation2007).

The inappropriate provision of housing at this time had wider impacts associated with accessing the labour market and other regularising activities (Rowley et al., Citation2020) which further exacerbated inequalities and hindered social integration. With a number of studies attributing this period to an increased risk of short-term, and long-term, homelessness and destitution (Allsopp et al., Citation2014; Dudhia, Citation2020; Mitton, Citation2021) (see more on homelessness and destitution below).

As a result, the literature routinely emphasised the impacts that this transition had on refugees’ mental health (Rowley et al., Citation2020; Vitale & Ryde, Citation2016). Many papers are consistent with the view that either an end or extension to the ‘move-on’ period or enhanced support (or ideally both) would prevent the challenges that refugees contend with for some time after receiving a decision on their case (see Ruiz & Vargas-Silva, Citation2021).

Access to housing and housing pathways

How refugees gain access to housing is, at least in the initial stages, largely dependent upon their routes into their host country. Whilst former asylum seekers tend to be signposted to mainstream services where they are often unaware of their rights (Strang et al., Citation2018), sponsored refugees on the other hand tend to benefit from the care provided by support workers in the first few months of arrival. As such the literature was reasonably in agreement that former asylum seekers tend to have a more difficult pathway to securing stable housing than their resettled counterparts, at least initially (Murdie, Citation2008), and are more likely to be spend time homeless or in precarious and insecure housing. From this point however, the settlement patterns and subsequent housing experiences resemble the experiences of other disadvantaged groups within the housing system (Robinson et al., Citation2007). The literature emphasised the challenge posed to refugees by a constrained housing market where there was a lack of adequate affordable stock (Netto, Citation2011b; Teixeira, Citation2014; Ziersch et al., Citation2017). Refugees often settled for housing of a lower-standard and there are examples of refugees sharing homes with others in order to meet living costs (see Teixeira, Citation2014).

Netto and Fraser (Citation2009) drawing on research in Scotland, describe how state provided accommodation units was converted to local authority accommodation to avoid the new refugee having to physically move out and locate new accommodation (Netto & Fraser, Citation2009). This was also a strategy in a case study from Germany reported by Weidinger and Kordel (Citation2020). Although seen positively as they addressed the challenge of finding new housing they were still low-quality dwellings and the process placed a strain on the availability of social housing stock which was in scarce supply. According to Meer et al. (Citation2019) whilst these attempts were positive steps the complexity and dysfunction which characterise this transition, against the residualisation of social housing was seen as too overwhelming to address without a change of national policy.

Discrimination in accessing housing from landlords and letting agents was a notable feature in a number of studies (Beer & Foley, Citation2003; Fozdar & Hartley, Citation2014; Murdie, Citation2008; Netto, Citation2011a; Weidinger & Kordel, Citation2020; Ziersch et al., Citation2017) while the absence of reported discrimination has been attributed to the potential that new refugees may not be aware of the structures of discrimination they are living within (Rose, Citation2001). In the absence of any, or long-term formal support, the social networks of refugees were seen as hugely important facilitators allowing refugees to access housing (Aigner, Citation2019; Banki, Citation2006; Murdie, Citation2008; Rose, Citation2001; Weidinger & Kordel, Citation2020). With work from Aigner (Citation2019) in the context of Vienna illustrating how networks ‘in various forms and at various levels’ (p.800) enable access to housing more effectively than the market or state led bureaucratic processes. In the absence of, or complimentary to, friends and families the support provided by refugee community organisations (RCOs) were of particular value to new refugees who were negotiating the housing system (Zetter & Pearl, Citation2000).

The housing pathways or housing careers approach as a method of identifying and engaging with the housing experiences of refugees was deployed in a number of studies (Beer & Foley, Citation2003; Flatau et al., Citation2015; Netto, Citation2011a; Robinson et al., Citation2007; Weidinger & Kordel, Citation2020) with Netto (Citation2011a) arguing for the adaptation of the theory to incorporate notions of place. A number of studies pointed to a lack of understanding of the long-term housing trajectories of refugees both in terms of their movement to and between tenure and longer-term engagement with the housing market (Allsopp et al., Citation2014; Hiebert, Citation2009)

Housing-related support

Social workers and housing workers from across the public, voluntary and community sectors, have been involved in the care and support of asylum seekers and refugees for many years. A large number of papers included substantial findings on the role and impact of this support. The vast majority of papers highlighted the critical role played by support workers, particularly those who are employed to support people in transition as sponsored refugees or those who had received refugee status after a period of time awaiting a decision on their asylum claim (Agbényiga et al., Citation2012; St. Arnault & Merali, Citation2019a; Vitale & Ryde, Citation2016). The valuable role such workers played at linking between existing services, filling gaps and exercising creativity was particularly highlighted (see Rose & Charette, Citation2017; Weidinger & Kordel, Citation2020). The literature is consistent when noting the upheaval caused to individuals by removing the support (for example Agbényiga et al., Citation2012). On the other hand, Hauge et al. (Citation2017) indicates that this withdrawal can be seen as an opportunity for asylum seekers to be more independent. The effectiveness of support was seen as improved when workers adopted the role of active connector instead of more passive signposting and referring roles (St. Arnault & Merali, Citation2019a).

Work by Netto and Fraser et al. (Citation2009) and Netto (Citation2011a, Citation2011b) highlighted the nuances in asylum and refugee support work and saw that such support workers can both support and hinder the lives of refugees. Particular issues such as racial discrimination towards refugees often going unnoticed (also shared by Phillips, Citation2006), a lack of sympathy towards refugees and the lack of visibility of refugees in services contributed to instances where their vulnerable positions were compounded. Few papers identified poor practice by support workers (exceptions are Christodoulou & Michael, Citation2019 and Seeberg et al., Citation2009) with most failings being attributed to the systems support workers were operating within.

Whilst only a handful of papers foregrounded the experience of those providing support. Within this there was consistency in findings which detailed the complex, multi-faceted nature of support with asylum seekers and refugees and the dilemmas between care and control that had to be negotiated (Brown & Horrocks, Citation2009; Phillips, Citation2006; Wren, Citation2007). With Wren (Citation2007) emphasising the challenge of balancing their support role with guarding against accusations of favouritism towards refugees from the wider community.

Effective inter-agency working and the engagement of the voluntary and community sector, particularly that of Refugee Community Organisations (RCOs), was commonly seen as emblematic of good practice in this area (Phillips, Citation2006; Zetter & Pearl, Citation1999). Although access to such services was often seen as challenging with there being a mismatch between affordable housing supply and the location of services (Rose, Citation2019).

Housing quality, affordability and [in]security

One of the key themes that came across distinctively in the literature was the quality of housing that refugees had access to. As already stated, it was common to find descriptions of initial accommodation as being in poor condition and in need of refurbishment (Bakker et al., Citation2016). Such conditions and basic facilities are often due to the short-stay nature of such accommodation, although research has identified that stays can be of significant duration (Vitale & Ryde, Citation2016).

With striking consistency, the literature overwhelmingly identified that refugees who are living in independent accommodation are living with poor-quality housing and are dissatisfied with their living conditions. Their experiences reflect those of many non-refugees who are accommodated in poor-quality, private rented housing, such as overcrowding and a lack of space; inadequate access to kitchen, bathroom or toilet facilities; unreliable heating and/or a requirement for additional sources of heat during winter; exposure to damp, cold and mouldy conditions, and general levels of deterioration of the internal and external fabric of dwellings (Ahmad et al., Citation2021; Guerin et al., Citation2013; Hynie, Citation2018; Ziersch & Due, Citation2018). However, in contrast to non-refugee populations, it was unlikely to find literature which drew on experiences of refugees that reflect other, more decent forms of accommodation. Beyond the UK, an in-depth research study in Western Australia by Fozdar and Hartley (Citation2014) discovered that refugees, on the whole, have poor experiences of housing provision, with the quality of the accommodation a significant contributory factor. Often poor-housing contributes to worsening existing, and creating new, health conditions for many refugees (Ziersch & Due, Citation2018). It was also evident that refugees from similar ethnicities or social and economic backgrounds simply put up with poor accommodation conditions in order to remain close to one another in their neighbourhood (Robinson et al., Citation2007; Warfa et al., Citation2006).

Accessible green spaces (i.e. gardens and shared areas) were another key feature of suitable housing. Whilst many accommodation units did not provide adequate space for refugees, Due et al. (Citation2020) highlight the great importance of access to outside green spaces for refugees for mental health and wellbeing (see also Sampson & Gifford, Citation2010). At the same time, Due et al. (Citation2020) note that managing green spaces without the appropriate resources could be an additional source of housing stress.

The issue of affordability is inherent to issues of security, quality and access and its impact was a key feature in several research projects in the Australian context (Beer & Foley, Citation2003; Flatau et al., Citation2015; Fozdar & Hartley, Citation2014), particularly evident in longitudinal studies. There is evidence that the lack of affordable housing also leads to an increased frequency of moves (also supported by Beer and Foley’s, Citation2003 study) and isolation (Fozdar & Hartley, Citation2014). The overarching importance of housing and affordable housing is recognised as impacting on other aspects of family life, with Fozdar and Hartley (Citation2014) observing that housing is more important for some new refugees than other concerns such as children’s education.

In the UK, housing affordability has been seen to lead to tensions and hostility between local residents and new migrant groups due to the scarcity of resources (Robinson et al., Citation2007) an issue also noted by Dwyer and Brown (Citation2008). Dwyer and Brown (Citation2008) highlight the impact that government schemes such as the Right to Buy has had on the supply of social housing. Righard and Oberg (Citation2019) highlight similar issues around appropriate affordable housing in Sweden, and studies such as Hiebert (Citation2009), Murdie (Citation2008) and Rose (Citation2019) reflect some of many papers that highlight concerns around housing affordability in the Canadian context. Rose (Citation2019) suggests that social housing was only available to those people with the most extreme needs, meaning that refugee newcomers had to find housing in the private rented sector. In keeping with this point, authors pointed for refugees to be more favourably reflected in the priority system of housing allocations (Ziersch et al., Citation2017). Rose (Citation2019) found that welfare levels were not keeping pace with rental costs and ultimately insufficient to meet their essential living needs. There was also limited housing for large families. Affordable housing was available in smaller towns, but support services were limited in these areas. Support structures were in place in cities, but these had limited housing availability. Hiebert (Citation2009) asserts that in Canada refugees fare least well amongst migrant groups, at least initially, although after a few years they are more able to access affordable housing.

Whilst the nature of awaiting a decision on an asylum claim is inherently precarious, there is a degree of security of tenure during that process. However, upon receipt of refugee status, it is common for refugees to experience a great deal of housing deprivation and insecurity (see above in relation to the transition in status) (Allsopp et al., Citation2014). Security was also seen as a factor in the longevity of refugees’ stay in one particular geographical place and it was a common feature in the literature that refugees would experience high levels of temporary accommodation or become homeless (Mitton, Citation2021; Murdie, Citation2008; Netto, 2011; Zhang et al., Citation2020). In other academic work, there were similar patterns of homelessness as a recurring problem for refugees in their host country. For example, St. Arnault and Merali (Citation2019a) in the context of Canada and Couch (Citation2011) in terms of Australia.

The heterogeneity of the housing experience

A further trend in the literature regarding housing experiences was the level of discrimination. For example, Banki (Citation2006) recorded the discrimination Burmese refugees experienced from landlords in Tokyo. Other studies have also focussed on housing discrimination and segregation experiences (Netto & Fraser, Citation2009; Ozkazanc, Citation2021; Phillimore & Goodson, Citation2006; Seethaler-Wari, Citation2018; Sundquist, Citation1995). Flatau et al. (Citation2015) review of literature and policy in Canada, the UK and Australia note the presence of racial harassment which inhibited the ability of refugees to integrate and impair their chances of accessing adequate housing. At the same time, this review acknowledges that refugees and asylum seekers are not a homogenous group, and whilst we acknowledge the prevalence of discrimination and racism, there is diversity in terms of intervention and differences in terms of lived experience and identity (see Flatau et al., Citation2014). Ziersch et al. (Citation2017) study highlights how certain groups are more vulnerable to housing issues (for example, single people and disabled people) and find it much harder to find appropriate affordable housing. Drawing on the work of Colic-Peisker and Tilbury (Citation2007) Flatau et al. (Citation2014, p. 17) highlight some of these differences to suggest that there are age and educational background differences in refugee settlement experiences. Similarly, in the UK context, Robinson et al. (Citation2007) study outlines the ways in which refugees from different ethnic groups, including Liberian and Somalian refugees had different views on the neighbourhoods where they were housed. Liberian refugees were coping with victimisation rather than relocating, whilst Somali refugees were looking to move because of harassment.

In terms of gender differences, Eltokhy’s (Citation2020) qualitative research on Syrian refugee women in Milan, demonstrates the intersection of gender and class with migration. This was tied in with ideas of safety, security, economic stability and belonging. Home ownership and secure income was seen as important in creating a sense of belonging and security particularly during the initial years of resettlement. Logan and Murdie (Citation2016) study on Tibetan refugees in Toronto, Canada, also demonstrates how ‘home’ and ‘home-making’ varies by gender. Fassetta et al. (Citation2016) report considers the gendered experiences of women asylum seekers in Glasgow with regards to pregnancy. The research findings indicated that inadequate housing and a lack of support from housing agencies working for the Home Office, and poor inter-agency working at the points where women were especially vulnerable. Third sector agencies were found to play a particularly important role in overcoming some of the challenges. Cheung and Phillimore’s (Citation2014) longitudinal study on refugees, gender, and integration also found a number of gender differences and called for gender sensitive measures to be part of the integration process. Whilst there was a balance towards the specific impacts on women refugees, Vitale and Ryde (Citation2016) pointed to the need for specific support for refugee men who were dealing with stress due to a range of pre and post-migration issues including trauma and housing insecurity.

There were also findings relating to household type, with single males more at risk from homelessness in the UK than some other household types (Dwyer & Brown, Citation2008; Mitton, Citation2021; Robinson et al., Citation2007). Whilst studies typically consist of participants from across age groups, when findings are reported they tend to focus on younger and working age people rather than older adults. Few studies examined the issue of sexuality in the literature with the exception of Righard and Oberg (Citation2019) and Wimark (Citation2021). Such studies tended to highlight the heteronormative design of housing policies for refugees and asylum seekers and highlighted the impact these had on those identifying as LBGTQ+.

Discussion

This paper has drawn on the findings of a comprehensive scoping review to examine the evidence which outlines the impact of housing for refugees. Due to the inherent complexities of researching multiple countries in relation to specific policy frameworks, in this paper we have focussed primarily on the UK, although drawn upon a wider body of research to inform our discussion and analysis. Provoked by the absence of a comprehensive account of the impact of housing on the lives of refugees, this paper aimed to fill this gap and to provide some guidance for moving forward in what are undoubtably critical times. We recognise that many of the issues identified in this paper are also faced by members of other excluded groups such as those who are on low-incomes, experience homelessness, or living in insecure of precarious housing. Many face challenges relating to accessing high-quality, secure and affordable housing, and this is especially apparent with the persistence of neoliberalism within a post-austerity public sector. However, it remains the case that refugees are particularly disadvantaged in relation to housing due to their socio-legal status, pre-migratory experiences and their positioning in society which affords them additional vulnerabilities and exacerbates the housing stress they face. Out of all migrant groups it is suggested that refugees experience the poorest housing outcomes (Hiebert, Citation2009).

This review has pointed to a body of literature which indicates that refugees are often living in poor quality and insecure housing, and that there is a direct relationship with this and poor mental health, as well as restricted opportunities for building social networks. As the literature has shown, the asylum dispersal system has typically created and exacerbated the vulnerabilities of refugees, which when considered alongside narratives of community tensions, further enhances their marginalisation. Agencies which provide support have called for the government to do more, and consistently support workers do far more than provide housing support, in recognition of the wider ranging and holistic needs refugees exhibit. Although the implementation of the policy of dispersal has been criticised, evidence about the long-term consequences of it is mixed. Much of this appears to be due to the neoliberal trend within recent governance processes which prohibit wider attempts at meaningful structural change. Rather, there has been an increasing privatisation of asylum (see for example, Darling, Citation2016), which has side-lined the role of local authorities in preference of the private sector which oversees the dispersal process. At the same time and consistent with these broader trends, there has been a wider acceptance of increasingly restrictive policies by the public. As Jordan and Düvell (Citation2003) have argued, restrictive entry mechanisms and restrictive support procedures aimed at such ‘undeserving’ migrants have been legitimised and increased precisely because irregular migrants and asylum seekers are increasingly narrated as threats to the labour market, public spending and social and racial harmony. At the time of writing the Conservative government is preparing a raft of increasingly draconian policies aimed at further restricting, managing, and arguably punishing, migrants who come to the UK through irregular means (Home Office, Citation2021a, Citation2021b) further legitimising and maintaining a hostile environment in all but name. The precise role envisaged for the housing sector in these new proposals remains unclear however, it is apparent that there is an intention to continue to support organised programmes of resettled refugees and to move towards accommodating asylum seekers in reception centres, ‘…so that they have simple, safe and secure accommodation to stay in while their claims and returns are being processed’ (Home Office, Citation2021b). The findings from this review are therefore particularly timely and indeed critical.

The available evidence suggests that reception centres greatly inhibit social integration for new migrants, as well as resulting in low levels of wellbeing and mental health, with particular issues being raised for parents and children. Such accommodation is also often poor quality and can further lead to a sense of ‘dehumanisation’ for those living there (Lietaert et al., Citation2020). For those who transition to refugee status, the so called 28-day move-on process, has been uniformly seen to exacerbate existing vulnerabilities. Strang et al. (Citation2018) described this as a structural failure ‘…which have resulted in disruption and disempowerment in refugees’ lives at the very point when society has legitimised their participation’ (p. 211). This was especially, but not exclusively, the case for those not deemed to be in ‘priority’ for housing, and for those with particular needs. This is compounded by local conditions in which there is scarcity of affordable and quality housing, resulting often in the use of temporary and/or unsuitable accommodation. Such issues also lead to an increased risk, and prevalence, of homelessness (Mitton, Citation2021).

The literature suggests that existing housing policies, situated within wider neoliberal trends, lead to insecurity and increased vulnerability and negatively impact on the ability for asylum seekers and refugees to build and maintain their social networks locally, At the same time, it was clear that these very social networks, along with the support provided by Refugee Community Organisations (RCOs), were especially important in enabling access to secure and stable housing. For ex-asylum seekers, the pathway to secure and stable housing appeared more difficult than for sponsored refugees, at least initially. As well as pointing to the need for improved housing quality and access to affordable and secure housing, the literature also pointed to the importance of access to green space for wellbeing and recovery.

There was also evidence of discrimination when accessing housing, reflective of wider inequalities facing migrant groups, with some groups having added needs and requirements arising from their identities which were not adequately addressed. In terms of the literature, little attention is given to the heterogeneity of refugees and asylum seekers. As Rutter (Citation2015) noted in relation to migrants more broadly, ‘an over-arching shortcoming’ (p. 93) of research on aspects of integration fails to acknowledge the super-diversity refugee communities as far too often, ‘migrants are portrayed as a homogenous and classless group’ (ibid). There is a scarcity of research relating to the role of housing in the support of refugees that acknowledges how identities are intersectional and that these differences inform experiences. Just as feminist research has highlighted that migration is gendered, it is necessary to acknowledge how race, ethnicity, religion, as well sexuality and disability informs the experiences of refugees and asylum seekers and their housing journeys.

Our recommendations arising from this study appeals for the pursuit of a new research agenda for housing studies in the context of refugees. Whilst we are aware of the negative impact attributed to initial accommodation there is an urgent need to undertake rigorous multi-method research which examines the immediate and long-term impact of and practice within such centres. There remains a lack of understanding about the dynamics of social networks refugees draw upon to access housing as well as a lack of information about the housing pathways and careers of more established refugees. There is a lack of rigorous research which has sought to investigate the health threats associated with substandard housing and neighbourhoods for refugees. Equally, there is a lack of understanding about how to provide restorative environments for refugees. There is also a significant need for research which adopts rigorous methodologies from different epistemological positions. Studies which employ longitudinal tracking methodologies are particularly needed in order to explore the outcomes over long periods of time. We also recognise that the refugee population is diverse yet the literature which delineates this diversity in relation to housing is nascent, this is a clear research gap. Finally, we fully acknowledge that housing is more than a physical dwelling. We recognise the importance and interconnectedness of the subjectivities of housing and the literature that draws on this concerning the meaning of home, place and neighbourhood is significant and extensive and deserves a review in its own right. Based on this review, whilst the shifts towards neoliberal approaches to the governance of migration is increasingly apparent, we feel there is an opportunity for housing studies scholars to engage with the wider socio-political context which pervades the accommodation of refugee studies. In particular, as identified by Preece and Bimpson (Citation2019) more robust data, the lived experience of housing systems and a focus on the needs of particular groups (such as refugees) will provide an evidence base which can challenge the wider structural inequalities which constrain lives; alongside a critical analysis of racialization, othering and exclusion.

Acknowledgements

This publication has been produced with the financial support of the European Union Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Philip Brown, Santokh Gill, and Jamie Halsall and in no way reflect the views of the funder, the European Commission or the United Kingdom Responsible Authority (UKRA). Neither the European Commission nor UKRA is liable for any use that may be made of the information in this publication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ager, A. & Strang, A. (2008) Understanding integration: A conceptual framework, Journal of Refugee Studies, 21, pp. 166–191.

- Agbényiga, D. L., Barrie, S., Djelaj, V. & Nawyn, S. J. (2012) Expanding our community: Independent and interdependent factors impacting refugee successful community resettlement, Advances in Social Work, 13, pp. 306–324.

- Ahmad, F., Othman, N., Hynie, M., Bayoumi, A. M., Oda, A., & McKenzie, K. (2020). Depression-level symptoms among Syrian refugees: findings from a Canadian longitudinal study, Journal of Mental Health, 30(2), pp. 246–254.

- Ahmad, F., Othman, N., Hynie, M., Bayoumi, A. M., Oda, A. & McKenzie, K. (2021) Depression-level symptoms among Syrian refugees: Findings from a Canadian longitudinal study, Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 30, pp. 246–254.

- Aigner, A. (2019) Housing entry pathways of refugees in Vienna, a city of social Housing, Housing Studies, 34, pp. 779–803.

- Allsopp, J., Sigona, N. & Phillimore, J. (2014) Poverty among refugees and asylum seekers in the UK, IRIS Working Paper Series, pp. 1–46. Available at http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-social-sciences/social-policy/iris/2014/working-paper-series/IRiS-WP-1-2014.pdf (accessed 18 June 2021).

- Arksey, H. & O’Malley, L. (2005) Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8, pp. 19–32.

- Bakker, L., Cheung, S. Y. , & Phillimore, J. (2016). The asylum-integration paradox: comparing asylum support systems and refugee integration in The Netherlands and the UK, International Migration, 54, pp. 118–132.

- Banki, S. (2006) Burmese refugees in Tokyo: Livelihoods in the urban environment, Journal of Refugee Studies, 19, pp. 328–344.

- Beer, A. & Foley, P. (2003) Housing need and provision for recently arrived refugees in Australia. AHURI Final Report No. 48, Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute. Available at https://www.ahuri.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/2251/AHURI_Final_Report_No48_Housing_need_and_provision_for_recently_arrived_refugees_in_Australia.pdf (accessed 21 July 2021).

- Benhabib, S. (2020) The end of the 1951 refugee convention? Dilemmas of sovereignty, territoriality, and human rights, Jus Cogens, 2, pp. 75–100.

- Bevelander, P., Mata, F., & Pendakur, R. (2019). Housing policy and employment outcomes for refugees, International Migration, 57(3), pp. 134–154.

- Bhagat, A. (2021) Displacement in “actually existing” racial neoliberalism: Refugee governance in Paris, Urban Geography, 42, pp. 634–653.

- Blank, M. (2019). “Wir Schaffen Das!”? Spatial pitfalls of neighborhood-based refugee reception in Germany—a case study of Frankfurt-Rödelheim, Social Sciences, 8(5), pp. 161.

- British Red Cross. (2018). Still an ordeal. Available at https://www.redcross.org.uk/-/media/documents/about-us/research-publications/refugee-support/still-an-ordeal-move-on-period-report.pdf (accessed 7 March 2022).

- Brown, P., Walkey, C. & Martin, P. (2020) Integration works: The role of organisations in refugee integration in Yorkshire and the Humber. The University of Huddersfield. Available at https://huddersfield.box.com/s/qias4ks55sazc445jaili2zvf06krjst (accessed 1 March 2022).

- Brown, P. & Horrocks, C. (2009) Making sense? The support of dispersed asylum seekers, International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care, 5, pp. 22–34.

- Bynner, C. (2019). Intergroup relations in a super-diverse neighbourhood: the dynamics of population composition, context and community, Urban Studies, 56(2), pp. 335–351.

- Byrne, K. A., Kuttner, P., Mohamed, A., Magana, G. R., & Goldberg, E. E. (2021). This is our home: Initiating participatory action housing research with refugee and immigrant communities in a time of unwelcome, Action Research, 19(2), pp. 393–410.

- Campbell, E. J., & Turpin, M. J. (2010). Refugee settlement workers’ perspectives on home safety issues for people from refugee backgrounds, Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 57(6), pp. 425–430.

- Campbell, M. R., Mann, K. D., Moffatt, S., Dave, M., & Pearce, M. S. (2018). Social determinants of emotional well-being in new refugees in the UK, Public Health, 164, pp. 72–81.

- Carter, T. S., & Osborne, J. (2009). Housing and neighbourhood challenges of refugee resettlement in declining inner city neighbourhoods: a Winnipeg case study, Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 7(3), pp. 308–327.

- Carter, T., Polevychok, C., & Osborne, J. (2009). The role of housing and neighbourhood in the re-settlement process: a case study of refugee households in Winnipeg, Canadian Geographer, 53(3), pp. 305–322.

- Carnet, P., Blanchard, C. & Apollonio, F. (2014) The move-on period: An ordeal for new refugees. Available at https://www.redcross.org.uk/-/media/documents/about-us/research-publications/refugee-support/move-on-period-an-ordeal-for-refugees.pdf (accessed 18 June 2021).

- Cheung, S.Y. & Phillimore, J. (2014) Refugees, social capital, and labour market integration in the UK, Sociology, 48, pp. 518–536.

- Cheung, S. Y., & Phillimore, J. (2017). Gender and refugee integration: a quantitative analysis of integration and social policy outcomes, Journal of Social Policy, 46(2), pp. 211–230. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279416000775

- Chimienti, S., & van Liempt, I. (2015) Super-diversity and the art of living in ethnically concentrated urban areas, Identities, 22(1), pp. 19–35,

- Christodoulou, J. & Michael, A. (2019) Integration governance in Cyprus accommodation, regeneration and exclusion. Available at https://www.glimer.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Cyprus-Accommodation.pdf (accessed 1 March 2022).

- Colic-Peisker, V. and Tilbury, F. (2007) Refugees and employment: the effect of visible difference on discrimination (Perth, Western Australia: Centre for Social and Community Research, Murdoch University).

- Couch, J. (2011) A new way home: Refugee young people and homelessness in Australia, Journal of Social Inclusion, 2, pp. 39–52.

- Czischke, D. & Huisman, C.J. (2018) Integration through collaborative housing? Dutch starters and refugees forming self-managing communities in Amsterdam, Urban Planning, 3, pp. 156–165.

- Darling, J. (2011) Domopolitics, governmentality and the regulation of asylum accommodation, Political Geography, 30, pp. 263–271.

- Darling, J. (2016) Asylum in austere times: Instability, privatization and experimentation within the UK asylum dispersal system, Journal of Refugee Studies, 29, pp. 483–505.

- Dudhia, P. (2020) Will I ever be safe? Asylum-seeking women made destitute in the UK. Available at https://www.refugeewomen.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/WRW-Will-I-ever-be-safe-web.pdf (accessed 1 March 2022).

- Due, C., Ziersch, A., Walsh, M. & Duivesteyn, E. (2020) Housing and health for people with refugee-and asylum-seeking backgrounds: A photovoice study in Australia, Housing Studies, pp. 1–27. doi:10.1080/02673037.2020.1857347

- Dwyer, P. & Brown, D. (2008) Accommodating “others”?: Housing dispersed, forced migrants in the UK, Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 30, pp. 203–218.

- Dwyer, P., Hodkinson, S., Lewis, H. & Waite, L. (2016) Socio-legal status and experiences of forced labour among asylum seekers and refugees in the UK, Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy, 32, pp. 182–198.

- El-Kayed, N., & Hamann, U. (2018). Refugees’ access to housing and residency in German cities: internal border regimes and their local variations, Social Inclusion, 6(1), pp. 135–146.

- Eltokhy, S. (2020) Towards belonging: Stability and home for Syrian refugee women in Milan, Journal of Identity and Migration Studies, 14, pp. 134–149.

- Fassetta, G., Lomba, S.D. & Quinn, N. (2016) A healthy start? Experiences of pregnant refugee and asylum seeking women in Scotland. Available at https://www.redcross.org.uk/-/media/documents/about-us/research-publications/refugee-support/a-healthy-start-report.pdf (accessed 18 June 2021).

- Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, E. & Qasmiyeh, Y.M. (2010) Muslim asylum-seekers and refugees: Negotiating identity, politics and religion in the UK, Journal of Refugee Studies, 23, pp. 294–314.

- Flatau, P., Colic-Peisker, V., Bauskis, A., Maginn, P. & Buergelt, P. (2014) Refugees, housing, and neighbourhoods in Australia, AHURI Final Report No. 224. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute. Available at https://researchers.cdu.edu.au/en/publications/refugees-housing-and-neighbourhoods-in-australia (accessed 11 June 2021).

- Flatau, P., Smith, J., Carson, G., Miller, J., Burvill, A. & Brand, R. (2015) The housing and homelessness journeys of refugees in Australia. AHURI Final Report No. 256. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute. Available at https://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/256#:∼:text=The%20housing%20and%20homelessness%20journeys%20of%20refugees%20in%20Australia,-Final%20Report%20No&text=This%20project%20looks%20at%20the,are%20successful%20in%20facilitating%20settlement (accessed 13 June 2021).

- Flug., M. & Hussein, J. (2019). Integration in the shadow of austerity—refugees in Newcastle upon Tyne, Social Sciences, 8(7), p. 212. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8070212

- Forrest, J., Hermes, K., Johnston, R., & Poulsen, M. (2013). The housing resettlement experience of refugee immigrants to Australia, Journal of Refugee Studies, 26(2), pp. 187–206.

- Fozdar, F. & Hartley, L. (2014) Housing and the creation of home for refugees in Western Australia, Housing, Theory and Society, 31, pp. 148–173.

- Franklin, M. (2018). Refugees and asylum seekers in belfast: finding ‘home’ through space and time, in M. Komarova & M. Svašek (Eds) Ethnographies of Movement, Sociality and Space: Place-Making in the New Northern Ireland, 1st ed., Vol. 8, pp. 250–266 (Berghahn Books). https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvw04c94.16

- Gewalt, S. C., Sarah, B., Ziegler, S., Szecsenyi, J., & Bozorgmehr, K. (2018). Psychosocial health of asylum seeking women living in state-provided accommodation in Germany during pregnancy and early motherhood: A case study exploring the role of social determinants of health. PLoS One, 13(12).

- Gidley, B., & Jayaweera, H. (2010). An evidence base on migration and integration in London. Available at https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/an_evidence_base_on_migration_and_integration_in_london.pdf (accessed 7 March 2022).

- Glen, V., & Lindsay, K. (2014). The Extent and Impact of Asylum Accommodation Problems in Scotland (Scottish Refugee Council).

- Griffiths, D., Sigona, N., & Zetter, R. (2005). Dispersal policy and practice, in D. Griffiths., N. Sigona & R. Zetter (Eds) Refugee Community Organizations and Dispersal: Networks, Resources and Social Capital, pp. 37–64 (Bristol: Policy Press/Bristol University Press).

- Ghorashi, H., de Boer, M. & ten Holder, F. (2018) Unexpected agency on the threshold: Asylum seekers narrating from an asylum seeker centre, Current Sociology. La Sociologie Contemporaine, 66, pp. 373–391.

- Goodfellow, M. (2019) Hostile Environment (London: Verso).

- Greatbatch, J. (1989) The gender difference: Feminist critiques of refugee discourse, International Journal of Refugee Law, 1, pp. 518–527.

- Guerin, P.B., Guerin, B. & Hussein Elmi, F. (2013) How do you acculturate when neighbors are throwing rocks in your window? Preserving the contexts of Somali refugee housing issues in policy, International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 5, pp. 41–49.

- Guma, T., Woods, M., Yarker, S. & Anderson, J. (2019) “It’s that kind of place here”: Solidarity, place-making and civil society response to the 2015 refugee crisis in Wales, UK, Social Inclusion, 7, pp. 96–105.

- Hancock, P., Cooper, T., & Bahn, S. (2009). Evaluation of the integrated services pilot program from Western Australia, Evaluation and Program Planning, 32(3), pp. 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2008.12.001

- Hauge, Å.L., Støa, E. & Denizou, K. (2017) Framing outsidedness–Aspects of housing quality in decentralized reception centres for asylum seekers in Norway. Housing, Theory and Society, 34, pp. 1–20.

- Hebbani, A., Colic-Peisker, V., & Mackinnon, M. (2018). Know thy neighbour: residential integration and social bridging among refugee settlers in Greater Brisbane, Journal of Refugee Studies, 31(1), pp. 82–103. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fex016

- Hiebert, D. (2009) Newcomers in the Canadian housing market: A longitudinal study, 2001–2005, Canadian Geographer, 53, pp. 265–384.

- Hill, E., Meer, N. & Peace, T. (2021) The role of asylum in processes of urban gentrification, The Sociological Review, 69, pp. 259–276.

- Hollis, J. (2019) The psychosocial experience of UK immigration detention, International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care, 15, pp. 76–89.

- Home Office (2021a) New Plan for Immigration: Policy Statement. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/972517/CCS207_CCS0820091708-001_Sovereign_Borders_Web_Accessible.pdf (accessed 22 June 2021).

- Home Office (2021b) Nationality and Borders Bill: A Factsheet. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-nationality-and-borders-bill-factsheet/nationality-and-borders-bill-factsheet (accessed 7 July 2021).

- Hubbard, P. (2005) “Inappropriate and incongruous”: Opposition to asylum centres in the English countryside, Journal of Rural Studies, 21, pp. 3–17.

- Hynie, M., Korn, A., & Tao, D. (2016). Social context and social integration for Government Assisted Refugees in Ontario, Canada, in M. Poteet & S. Nourpanah (Eds), After the Flight: The Dynamics of Refugee Settlement and Integration, pp. 183–227. (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars).

- Hynie, M. (2018) The social determinants of refugee mental health in the post-migration context: A critical review, The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 63, pp. 297–303.

- Jones, H., Gunaratnam, Y. & Bhattacharyya, G. (2017) Go Home: The Politics of Immigration Controversies (Manchester: Manchester University Press).

- Jordan, B. & Düvell, F. (2003) Migration: The Boundaries of Equality and Justice (Cambridge: Polity press).

- Kreichauf, R. (2018). From forced migration to forced arrival: the campization of refugee accommodation in European cities. Comparative Migration Studies, 6(7).

- Lietaert, I., Verhaeghe, F. & Derluyn, I. (2020) Families on hold: How the context of an asylum centre affects parenting experiences, Child & Family Social Work, 25, pp. 1–8.